User login

Can prophylactic salpingectomies be achieved with the vaginal approach?

In the last decade, there has been a major shift in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ovarian cancers. Current literature suggests that many high-grade serous carcinomas develop from the distal aspect of the fallopian tube and that serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is likely the precursor. The critical role that the fallopian tubes play as the likely origin of many serous ovarian and pelvic cancers has resulted in a shift from prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, which may increase risk for cardiovascular disease, to prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy (PBS) at the time of hysterectomy.

It is important that this shift occur with vaginal hysterectomy (VH) and not only with other surgical approaches. It is known that PBS is performed more commonly during laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy, and it’s possible that the need for adnexal surgery may further contribute to the decline in the rate of VH performed in the United States. This is despite evidence that the vaginal approach is preferred for benign hysterectomy even in patients with a nonprolapsed and large fibroid uterus, obesity, or previous pelvic surgery. Current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines also state that the need to perform adnexal surgery is not a contraindication to the vaginal approach.

So that more women may attain the benefits and advantages of VH, we need more effective teaching programs for vaginal surgery in residency training programs, hospitals, and community surgical centers. Moreover, we must appreciate that PBS with VH is safe and feasible. There are multiple techniques and tools available to facilitate the successful removal of the tubes, particularly in difficult cases.

The benefit and safety of PBS

Is PBS really effective in decreasing the incidence and mortality of ovarian cancer? A proposed randomized trial in Sweden with a target accrual of 4,400 patients – the Hysterectomy and Opportunistic Salpingectromy Study (HOPPSA, NCT03045965) – will evaluate the risk of ovarian cancer over a 10- to 30-year follow-up period in patients undergoing hysterectomy through all routes. While we wait for these prospective results, an elegant decision-model analysis suggests that routine PBS during VH would eliminate one diagnosis of ovarian cancer for every 225 women undergoing hysterectomy (reducing the risk from 0.956% to 0.511%) and would prevent one death for every 450 women (reducing the risk from 0.478% to 0.256%). The analysis, which drew upon published literature, Medicare reimbursement data, and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, also found that PBS with VH is a less expensive strategy than VH alone because of an increased risk of future adnexal surgery in women retaining their tubes.1

The question of whether PBS places a woman at risk for early menopause is a relevant one. A study following women for 3-5 years after surgery showed that the addition of PBS to total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women of reproductive age does not appear to modify ovarian function.2 However, a recently published retrospective study from the Swedish National Registry showed that women who underwent PBS with abdominal or laparoscopic benign hysterectomy had an increased risk of menopausal symptoms 1 year after surgery.3 Women between the ages of 45-49 years were at highest risk, suggesting increased vulnerability to possible vascular effects of PBS. A longer follow-up period may be necessary to assess younger age groups.

In a multicenter, prospective and observational trial involving 69 patients undergoing VH, PBS was feasible in 75% (a majority of whom [78%] had pelvic organ prolapse) and increased operating time by 11 minutes with no additional complications noted. The surgeons in this study, primarily urogynecologists, utilized a clamp or double-clamp technique to remove the fimbriae.4

The decision-model analysis mentioned above found that PBS would involve slightly more complications than VH alone (7.95% vs. 7.68%),1 and a systematic review that I coauthored of PBS in low-risk women found a small to no increase in operative time and no additional estimated blood loss, hospital stay, or complications for PBS.5

Tools and techniques

Vaginal PBS can be accomplished easily with traditional clamp-cut-tie technique in cases where the fallopian tubes are accessible, such as in patients with uterine prolapse. Generally, most surgeons perform a distal fimbriectomy only for risk-reduction purposes because this is where precursor lesions known as serous tubal intraepithelial cancer (STIC) reside.

To perform a fimbriectomy in cases where the distal portion of the tube is easily accessible, a Kelly clamp is placed across the mesosalpinx, and a fine tie is used for ligature. In more challenging hysterectomy cases, such as in lack of uterine prolapse, large fibroid uterus, morbid obesity, and in patients with previous tubal ligation, the fallopian tubes can be more difficult to access. In these cases, I prefer the use of the vessel-sealing device to seal and divide the mesosalpinx.

Here I describe three specific techniques that can facilitate the removal of the fallopian tubes in more challenging cases. In each technique, the entire fallopian tubes are removed – without leaving behind the proximal stump. The residual stump has the potential of developing into a hydrosalpinx that may necessitate another procedure in the future for the patient.

Separate the fallopian tube before clamping the ‘utero-ovarian ligament’ technique

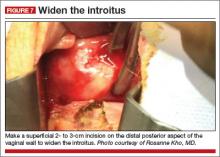

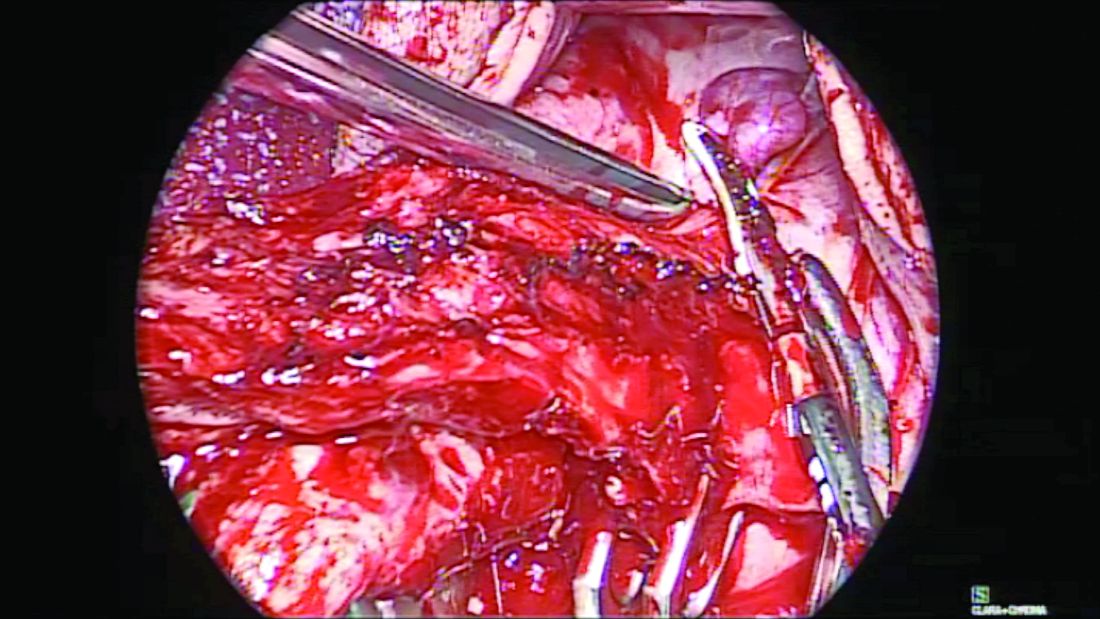

Before completion of the hysterectomy and clamping of the round ligament/fallopian tube/utero-ovarian ligament (RFUO) complex (commonly referred as the “utero-ovarian ligament”), I recommend first identifying the proximal portion of the fallopian tube. The isthmus is sealed and divided from its attachment to the uterine cornua, and a clamp is placed on the remaining round ligament/utero-ovarian ligament complex. The pedicle is then cut and tied. (Figure 1.) After removal of the uterus, the fallopian tube is ready to be grasped with an Allis clamp or Babcock forceps, and the remaining mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal portion/fimbriae.

Round ligament–mesosalpinx technique

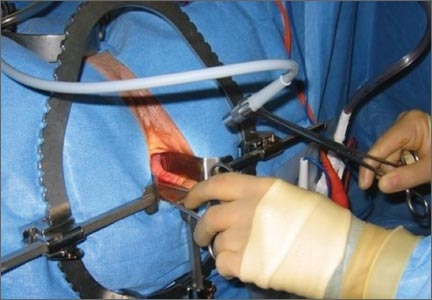

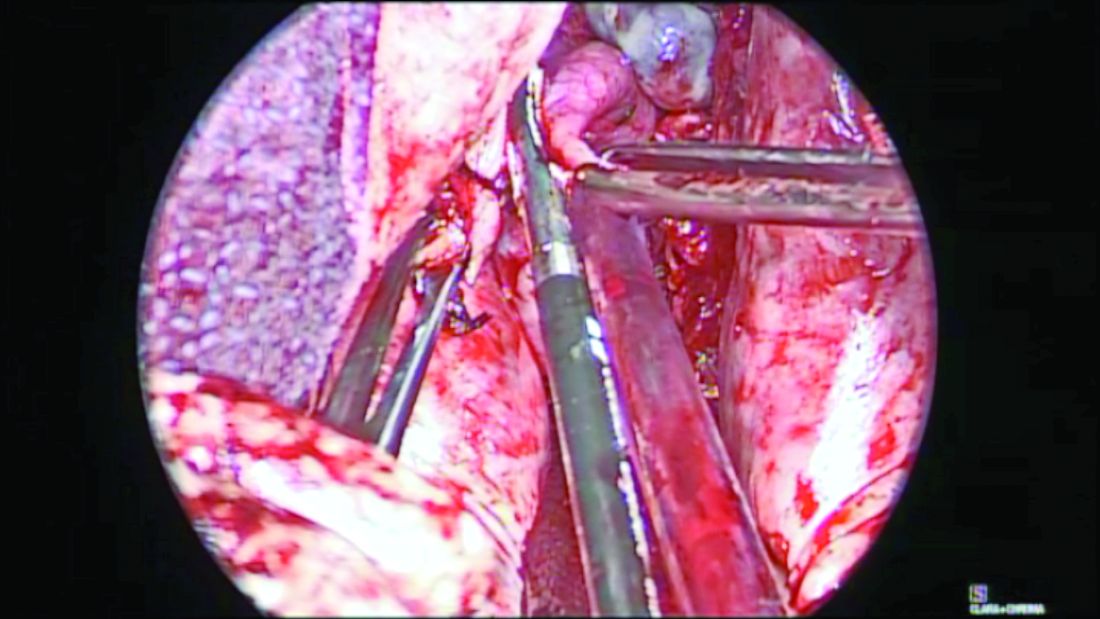

When the uterus is large or lacks prolapse, the fallopian tubes can be difficult to visualize. In such cases, I recommend the use of the round ligament–mesosalpinx technique. After completion of the hysterectomy and ligation of the RFUO complex, a long and moist vaginal pack (I prefer the 4” x 36” cotton vaginal pack by Dukal) is used to push the bowels back and expose the adnexae. The round ligament is identified within the RFUO complex and transected using a monopolar instrument. This step that separates the round ligament from the RFUO complex successfully releases the adnexae from the pelvic sidewall, making it easier to access the fallopian tubes (and the ovaries, when needed). A window is created in the mesosalpinx, and a curved clamp is placed on the ovarian vessels. Using sharp scissors, the proximal portion of the fallopian tube contained within the RFUO complex is separated, and the mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal end using the vessel-sealing device. (Figure 2.)

vNOTES (transvaginal Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery) salpingectomy technique

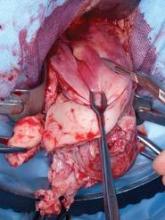

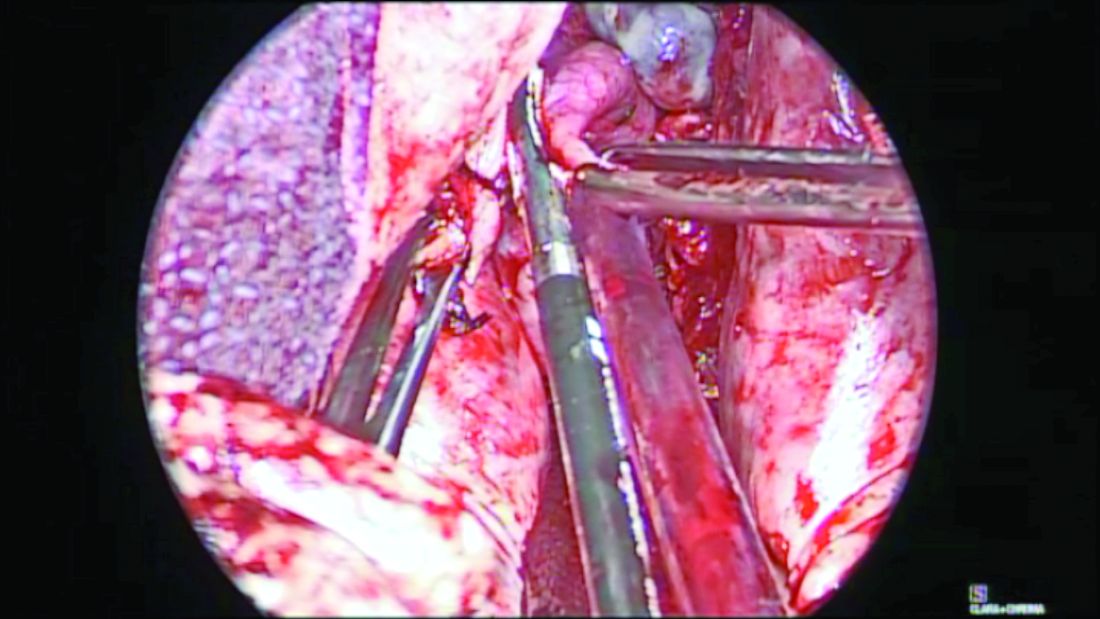

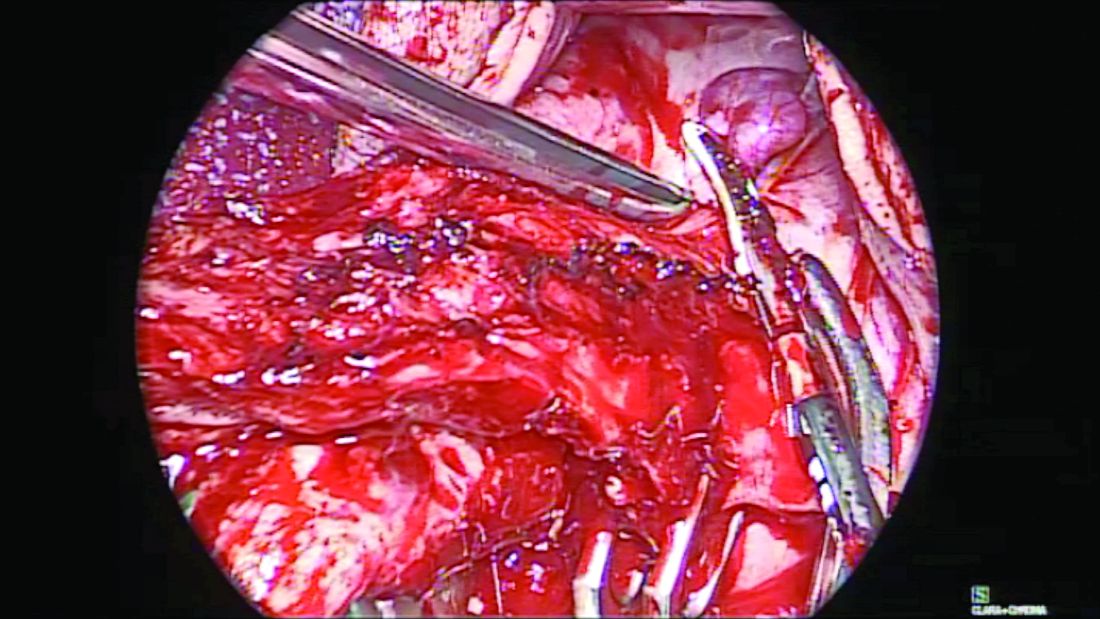

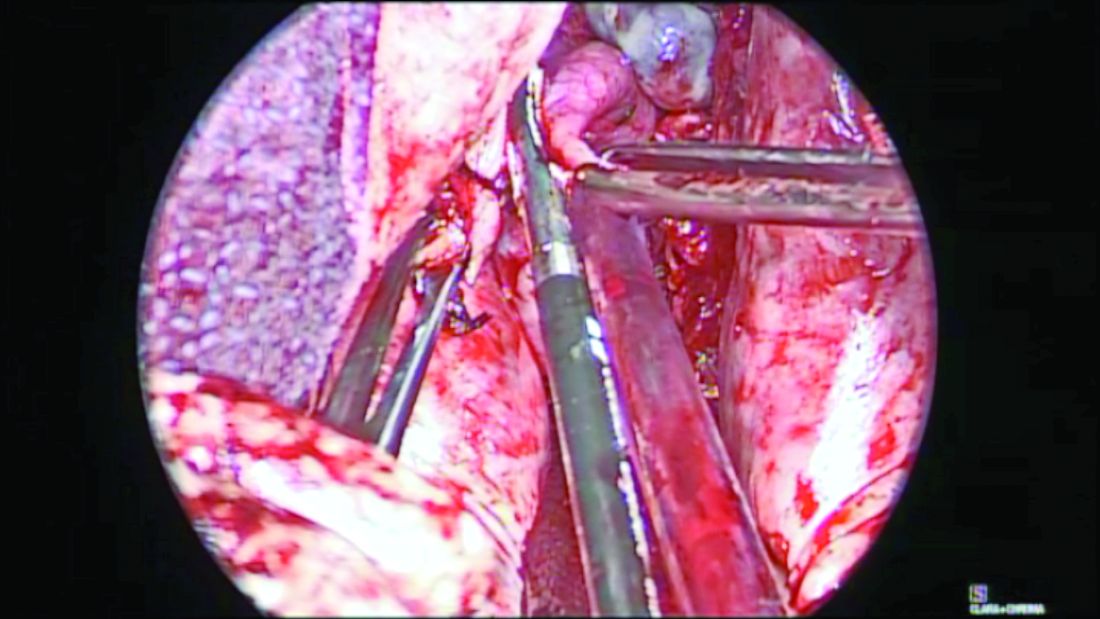

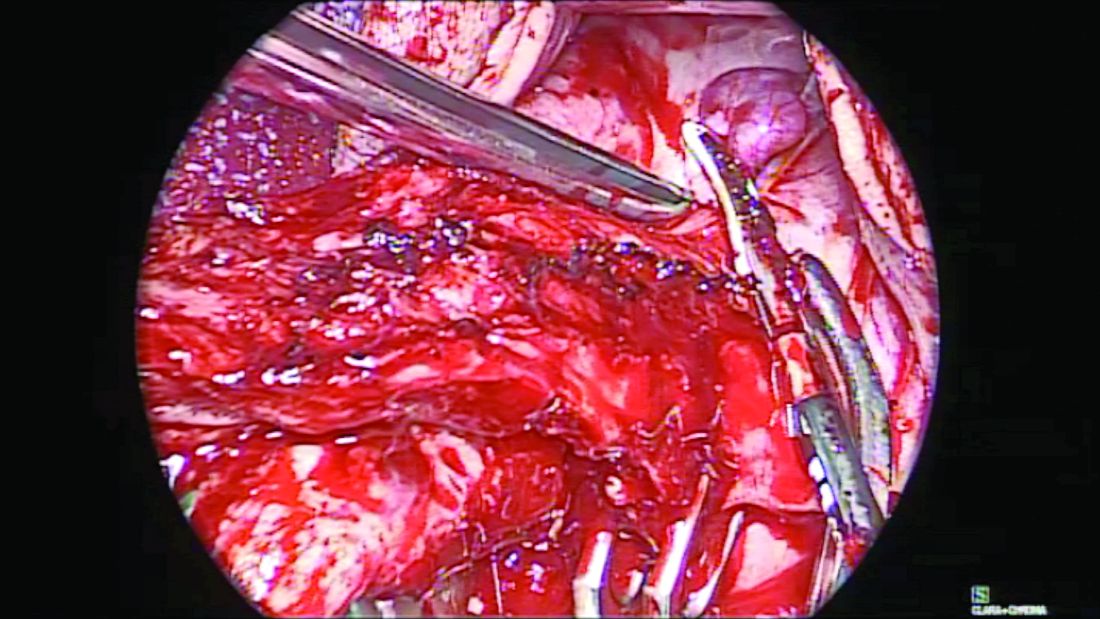

When the adnexae is noted to be high in the pelvis or when it is adherent to the pelvic sidewall, I recommend the vNOTES technique. It involves insertion of a mini-gel port into the vaginal opening. (Figure 3.) A 5-mm or 10-mm scope is inserted through this port for visualization. The fallopian tube can be grasped with a laparoscopic grasper and the mesosalpinx sealed and divided using a vessel-sealing device. (Figure 4.) Often, because the bowel is already retracted up with the vaginal pack, insufflation is not necessary with this procedure.

The change in our understanding of the etiology of ovarian cancer calls for salpingectomy during hysterectomy. With such tools, devices, and techniques that facilitate the vaginal removal of the fallopian tubes, the need for prophylactic salpingectomy should not be a deterrent to pursuing a hysterectomy vaginally.

Dr. Kho is head of the section of benign gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):503-4.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):145-50.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:85.e1-10.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:605.e1-5.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Feb;24(2):218-29.

In the last decade, there has been a major shift in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ovarian cancers. Current literature suggests that many high-grade serous carcinomas develop from the distal aspect of the fallopian tube and that serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is likely the precursor. The critical role that the fallopian tubes play as the likely origin of many serous ovarian and pelvic cancers has resulted in a shift from prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, which may increase risk for cardiovascular disease, to prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy (PBS) at the time of hysterectomy.

It is important that this shift occur with vaginal hysterectomy (VH) and not only with other surgical approaches. It is known that PBS is performed more commonly during laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy, and it’s possible that the need for adnexal surgery may further contribute to the decline in the rate of VH performed in the United States. This is despite evidence that the vaginal approach is preferred for benign hysterectomy even in patients with a nonprolapsed and large fibroid uterus, obesity, or previous pelvic surgery. Current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines also state that the need to perform adnexal surgery is not a contraindication to the vaginal approach.

So that more women may attain the benefits and advantages of VH, we need more effective teaching programs for vaginal surgery in residency training programs, hospitals, and community surgical centers. Moreover, we must appreciate that PBS with VH is safe and feasible. There are multiple techniques and tools available to facilitate the successful removal of the tubes, particularly in difficult cases.

The benefit and safety of PBS

Is PBS really effective in decreasing the incidence and mortality of ovarian cancer? A proposed randomized trial in Sweden with a target accrual of 4,400 patients – the Hysterectomy and Opportunistic Salpingectromy Study (HOPPSA, NCT03045965) – will evaluate the risk of ovarian cancer over a 10- to 30-year follow-up period in patients undergoing hysterectomy through all routes. While we wait for these prospective results, an elegant decision-model analysis suggests that routine PBS during VH would eliminate one diagnosis of ovarian cancer for every 225 women undergoing hysterectomy (reducing the risk from 0.956% to 0.511%) and would prevent one death for every 450 women (reducing the risk from 0.478% to 0.256%). The analysis, which drew upon published literature, Medicare reimbursement data, and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, also found that PBS with VH is a less expensive strategy than VH alone because of an increased risk of future adnexal surgery in women retaining their tubes.1

The question of whether PBS places a woman at risk for early menopause is a relevant one. A study following women for 3-5 years after surgery showed that the addition of PBS to total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women of reproductive age does not appear to modify ovarian function.2 However, a recently published retrospective study from the Swedish National Registry showed that women who underwent PBS with abdominal or laparoscopic benign hysterectomy had an increased risk of menopausal symptoms 1 year after surgery.3 Women between the ages of 45-49 years were at highest risk, suggesting increased vulnerability to possible vascular effects of PBS. A longer follow-up period may be necessary to assess younger age groups.

In a multicenter, prospective and observational trial involving 69 patients undergoing VH, PBS was feasible in 75% (a majority of whom [78%] had pelvic organ prolapse) and increased operating time by 11 minutes with no additional complications noted. The surgeons in this study, primarily urogynecologists, utilized a clamp or double-clamp technique to remove the fimbriae.4

The decision-model analysis mentioned above found that PBS would involve slightly more complications than VH alone (7.95% vs. 7.68%),1 and a systematic review that I coauthored of PBS in low-risk women found a small to no increase in operative time and no additional estimated blood loss, hospital stay, or complications for PBS.5

Tools and techniques

Vaginal PBS can be accomplished easily with traditional clamp-cut-tie technique in cases where the fallopian tubes are accessible, such as in patients with uterine prolapse. Generally, most surgeons perform a distal fimbriectomy only for risk-reduction purposes because this is where precursor lesions known as serous tubal intraepithelial cancer (STIC) reside.

To perform a fimbriectomy in cases where the distal portion of the tube is easily accessible, a Kelly clamp is placed across the mesosalpinx, and a fine tie is used for ligature. In more challenging hysterectomy cases, such as in lack of uterine prolapse, large fibroid uterus, morbid obesity, and in patients with previous tubal ligation, the fallopian tubes can be more difficult to access. In these cases, I prefer the use of the vessel-sealing device to seal and divide the mesosalpinx.

Here I describe three specific techniques that can facilitate the removal of the fallopian tubes in more challenging cases. In each technique, the entire fallopian tubes are removed – without leaving behind the proximal stump. The residual stump has the potential of developing into a hydrosalpinx that may necessitate another procedure in the future for the patient.

Separate the fallopian tube before clamping the ‘utero-ovarian ligament’ technique

Before completion of the hysterectomy and clamping of the round ligament/fallopian tube/utero-ovarian ligament (RFUO) complex (commonly referred as the “utero-ovarian ligament”), I recommend first identifying the proximal portion of the fallopian tube. The isthmus is sealed and divided from its attachment to the uterine cornua, and a clamp is placed on the remaining round ligament/utero-ovarian ligament complex. The pedicle is then cut and tied. (Figure 1.) After removal of the uterus, the fallopian tube is ready to be grasped with an Allis clamp or Babcock forceps, and the remaining mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal portion/fimbriae.

Round ligament–mesosalpinx technique

When the uterus is large or lacks prolapse, the fallopian tubes can be difficult to visualize. In such cases, I recommend the use of the round ligament–mesosalpinx technique. After completion of the hysterectomy and ligation of the RFUO complex, a long and moist vaginal pack (I prefer the 4” x 36” cotton vaginal pack by Dukal) is used to push the bowels back and expose the adnexae. The round ligament is identified within the RFUO complex and transected using a monopolar instrument. This step that separates the round ligament from the RFUO complex successfully releases the adnexae from the pelvic sidewall, making it easier to access the fallopian tubes (and the ovaries, when needed). A window is created in the mesosalpinx, and a curved clamp is placed on the ovarian vessels. Using sharp scissors, the proximal portion of the fallopian tube contained within the RFUO complex is separated, and the mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal end using the vessel-sealing device. (Figure 2.)

vNOTES (transvaginal Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery) salpingectomy technique

When the adnexae is noted to be high in the pelvis or when it is adherent to the pelvic sidewall, I recommend the vNOTES technique. It involves insertion of a mini-gel port into the vaginal opening. (Figure 3.) A 5-mm or 10-mm scope is inserted through this port for visualization. The fallopian tube can be grasped with a laparoscopic grasper and the mesosalpinx sealed and divided using a vessel-sealing device. (Figure 4.) Often, because the bowel is already retracted up with the vaginal pack, insufflation is not necessary with this procedure.

The change in our understanding of the etiology of ovarian cancer calls for salpingectomy during hysterectomy. With such tools, devices, and techniques that facilitate the vaginal removal of the fallopian tubes, the need for prophylactic salpingectomy should not be a deterrent to pursuing a hysterectomy vaginally.

Dr. Kho is head of the section of benign gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):503-4.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):145-50.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:85.e1-10.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:605.e1-5.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Feb;24(2):218-29.

In the last decade, there has been a major shift in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ovarian cancers. Current literature suggests that many high-grade serous carcinomas develop from the distal aspect of the fallopian tube and that serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is likely the precursor. The critical role that the fallopian tubes play as the likely origin of many serous ovarian and pelvic cancers has resulted in a shift from prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, which may increase risk for cardiovascular disease, to prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy (PBS) at the time of hysterectomy.

It is important that this shift occur with vaginal hysterectomy (VH) and not only with other surgical approaches. It is known that PBS is performed more commonly during laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy, and it’s possible that the need for adnexal surgery may further contribute to the decline in the rate of VH performed in the United States. This is despite evidence that the vaginal approach is preferred for benign hysterectomy even in patients with a nonprolapsed and large fibroid uterus, obesity, or previous pelvic surgery. Current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines also state that the need to perform adnexal surgery is not a contraindication to the vaginal approach.

So that more women may attain the benefits and advantages of VH, we need more effective teaching programs for vaginal surgery in residency training programs, hospitals, and community surgical centers. Moreover, we must appreciate that PBS with VH is safe and feasible. There are multiple techniques and tools available to facilitate the successful removal of the tubes, particularly in difficult cases.

The benefit and safety of PBS

Is PBS really effective in decreasing the incidence and mortality of ovarian cancer? A proposed randomized trial in Sweden with a target accrual of 4,400 patients – the Hysterectomy and Opportunistic Salpingectromy Study (HOPPSA, NCT03045965) – will evaluate the risk of ovarian cancer over a 10- to 30-year follow-up period in patients undergoing hysterectomy through all routes. While we wait for these prospective results, an elegant decision-model analysis suggests that routine PBS during VH would eliminate one diagnosis of ovarian cancer for every 225 women undergoing hysterectomy (reducing the risk from 0.956% to 0.511%) and would prevent one death for every 450 women (reducing the risk from 0.478% to 0.256%). The analysis, which drew upon published literature, Medicare reimbursement data, and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, also found that PBS with VH is a less expensive strategy than VH alone because of an increased risk of future adnexal surgery in women retaining their tubes.1

The question of whether PBS places a woman at risk for early menopause is a relevant one. A study following women for 3-5 years after surgery showed that the addition of PBS to total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women of reproductive age does not appear to modify ovarian function.2 However, a recently published retrospective study from the Swedish National Registry showed that women who underwent PBS with abdominal or laparoscopic benign hysterectomy had an increased risk of menopausal symptoms 1 year after surgery.3 Women between the ages of 45-49 years were at highest risk, suggesting increased vulnerability to possible vascular effects of PBS. A longer follow-up period may be necessary to assess younger age groups.

In a multicenter, prospective and observational trial involving 69 patients undergoing VH, PBS was feasible in 75% (a majority of whom [78%] had pelvic organ prolapse) and increased operating time by 11 minutes with no additional complications noted. The surgeons in this study, primarily urogynecologists, utilized a clamp or double-clamp technique to remove the fimbriae.4

The decision-model analysis mentioned above found that PBS would involve slightly more complications than VH alone (7.95% vs. 7.68%),1 and a systematic review that I coauthored of PBS in low-risk women found a small to no increase in operative time and no additional estimated blood loss, hospital stay, or complications for PBS.5

Tools and techniques

Vaginal PBS can be accomplished easily with traditional clamp-cut-tie technique in cases where the fallopian tubes are accessible, such as in patients with uterine prolapse. Generally, most surgeons perform a distal fimbriectomy only for risk-reduction purposes because this is where precursor lesions known as serous tubal intraepithelial cancer (STIC) reside.

To perform a fimbriectomy in cases where the distal portion of the tube is easily accessible, a Kelly clamp is placed across the mesosalpinx, and a fine tie is used for ligature. In more challenging hysterectomy cases, such as in lack of uterine prolapse, large fibroid uterus, morbid obesity, and in patients with previous tubal ligation, the fallopian tubes can be more difficult to access. In these cases, I prefer the use of the vessel-sealing device to seal and divide the mesosalpinx.

Here I describe three specific techniques that can facilitate the removal of the fallopian tubes in more challenging cases. In each technique, the entire fallopian tubes are removed – without leaving behind the proximal stump. The residual stump has the potential of developing into a hydrosalpinx that may necessitate another procedure in the future for the patient.

Separate the fallopian tube before clamping the ‘utero-ovarian ligament’ technique

Before completion of the hysterectomy and clamping of the round ligament/fallopian tube/utero-ovarian ligament (RFUO) complex (commonly referred as the “utero-ovarian ligament”), I recommend first identifying the proximal portion of the fallopian tube. The isthmus is sealed and divided from its attachment to the uterine cornua, and a clamp is placed on the remaining round ligament/utero-ovarian ligament complex. The pedicle is then cut and tied. (Figure 1.) After removal of the uterus, the fallopian tube is ready to be grasped with an Allis clamp or Babcock forceps, and the remaining mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal portion/fimbriae.

Round ligament–mesosalpinx technique

When the uterus is large or lacks prolapse, the fallopian tubes can be difficult to visualize. In such cases, I recommend the use of the round ligament–mesosalpinx technique. After completion of the hysterectomy and ligation of the RFUO complex, a long and moist vaginal pack (I prefer the 4” x 36” cotton vaginal pack by Dukal) is used to push the bowels back and expose the adnexae. The round ligament is identified within the RFUO complex and transected using a monopolar instrument. This step that separates the round ligament from the RFUO complex successfully releases the adnexae from the pelvic sidewall, making it easier to access the fallopian tubes (and the ovaries, when needed). A window is created in the mesosalpinx, and a curved clamp is placed on the ovarian vessels. Using sharp scissors, the proximal portion of the fallopian tube contained within the RFUO complex is separated, and the mesosalpinx is sealed and divided all the way to the distal end using the vessel-sealing device. (Figure 2.)

vNOTES (transvaginal Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery) salpingectomy technique

When the adnexae is noted to be high in the pelvis or when it is adherent to the pelvic sidewall, I recommend the vNOTES technique. It involves insertion of a mini-gel port into the vaginal opening. (Figure 3.) A 5-mm or 10-mm scope is inserted through this port for visualization. The fallopian tube can be grasped with a laparoscopic grasper and the mesosalpinx sealed and divided using a vessel-sealing device. (Figure 4.) Often, because the bowel is already retracted up with the vaginal pack, insufflation is not necessary with this procedure.

The change in our understanding of the etiology of ovarian cancer calls for salpingectomy during hysterectomy. With such tools, devices, and techniques that facilitate the vaginal removal of the fallopian tubes, the need for prophylactic salpingectomy should not be a deterrent to pursuing a hysterectomy vaginally.

Dr. Kho is head of the section of benign gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):503-4.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):145-50.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:85.e1-10.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:605.e1-5.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Feb;24(2):218-29.

Highlights from the 2018 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Scientific Meeting

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

Endometriosis affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age or, conservatively, about 6.5 million women in the United States.1,2 There are 3 types of endometriosis—superficial, ovarian, and deep—and in the past each of these was assumed to have a distinct pathogenesis.3 Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is the presence of one or more endometriotic nodules deeper than 5 mm. In a study at a large tertiary-care center, 40% of patients with endometriosis had deep disease.4 DIE is associated with more severe pain and infertility.5 In patients with endometriosis, diagnosis is commonly made 7 to 9 years after the initial pelvic pain presentation.6 For these reasons, well-directed history taking and proper evaluation and treatment should be pursued to relieve pain and optimize outcomes.

CASE Young woman with intensifying pelvic pain

Mary is a 26-year-old social worker who presents to her ObGyn with symptoms of worsening pain during as well as outside her periods. What additional information would you want to obtain from Mary, given her chief symptom of pain?

Investigate the type of pain

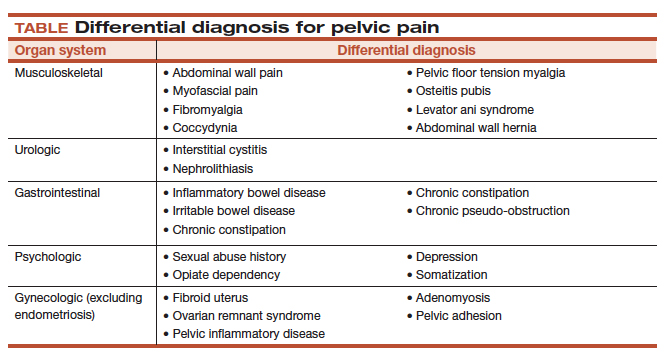

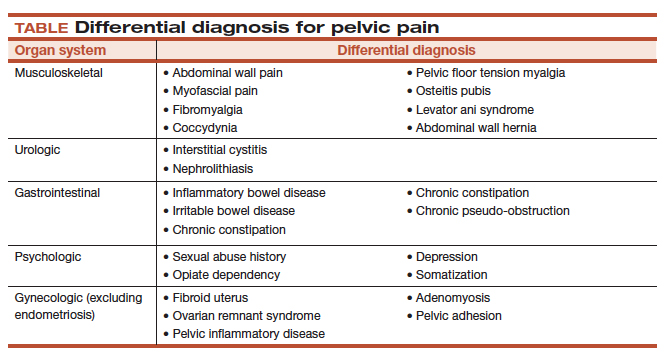

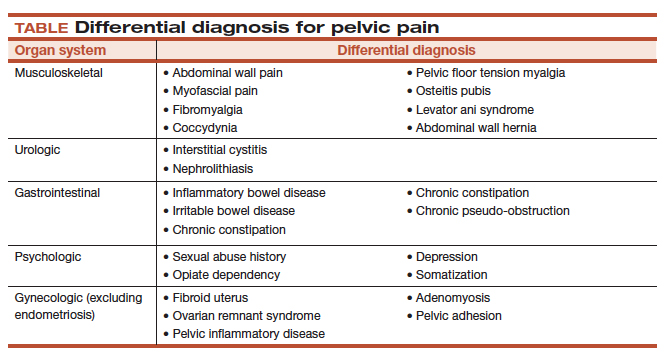

It is important to ask the patient about her menstrual and sexual history, her thoughts regarding near- and long-term fertility, and the type and severity of her pain symptoms. The 5 pain symptoms specific to pelvic pain are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and noncyclic pelvic pain. A visual analog scale (VAS) for pain as well as pelvic pain questionnaires can be used to guide evaluation options and monitor treatment outcomes. In addition, it is of paramount importance to understand the differential diagnoses that can present as pelvic pain (TABLE).

CASE Continued: Mary’s history

Mary reports that she always has had painful periods and that she was started on oral contraceptive pills for pain control and regulation of her periods soon after the onset of menses, when she was 12 years old. In college, she was prescribed oral contraceptive pills for contraception. Recently engaged, she is interested in becoming pregnant in 3 years.

A year ago, Mary discontinued the pills because of their adverse effects. Now she has severe pain during (VAS score, 8/10) and outside (VAS score, 7) her monthly periods. Because of this pain, she has taken time off from work twice within the past 6 months. She has pain during intercourse (VAS score, 7) and some pain with bowel movements during her menses (VAS score, 4). Pelvic examination reveals a normal-sized uterus and adnexa as well as a tender nodule in the rectovaginal septum.

What diagnostic tests and imaging would you obtain?

Imaging’s role in diagnosis

At many advanced centers for endometriosis, DIE is successfully diagnosed with specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) protocols. In a recent review, MRI’s pooled sensitivity and specificity for rectosigmoid endometriosis were 92% and 96%, respectively.7 Choice of imaging for DIE depends on the skills and experience of the clinicians at each center. At a large referral center in São Paulo, Brazil, TVUS with bowel preparation had better sensitivity and specificity for deep retrocervical and rectosigmoid disease compared with MRI and digital pelvic examination.8 In addition, at a center in the United States, we found that proficiency in performing TVUS for DIE was achieved after 70 to 75 cases, and the exam took an average of only 20 minutes.9

Despite recent advances in imaging, most gynecologic societies still hold that endometriosis is to be definitively diagnosed with histologic confirmation from tissue biopsies during surgery. Although surgery remains the diagnostic gold standard, it does not mean that all patients with pelvic pain should undergo diagnostic laparoscopy with tissue biopsies.

The combination of compelling clinical signs, symptoms, and imaging findings (such as absence of findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis) can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical (that is, clinical) diagnosis of endometriosis. Major societies recommend empiric medical therapy (for example, combination oral contraceptives) for the pain associated with superficial endometriosis.10,11 When there is no response to treatment, or when a patient declines or has contraindications to medical therapy, diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis should be considered.

CASE Continued: Diagnosis

Mary undergoes TVUS with bowel preparation, which reveals a normal uterus and adnexa and the presence of 2 lesions, a 2×1.5-cm retrocervical lesion and a 1.8×2-cm rectosigmoid lesion 9 cm above the anal verge. The rectosigmoid lesion involves the external muscularis and compromises 30% of the bowel circumference.

How would you manage the bowel DIE?

Read about management options and individualized care.

Management options: Factor in the variables

DIE can involve the ureters and bladder, the retrocervical and rectovaginal spaces, the appendix, and the bowel. Lesions can be single or multifocal. Although our institutions’ imaging with MRI and TVUS is highly accurate, we additionally recommend the use of colonoscopy (with directed biopsies if appropriate) to evaluate patients who present with rectal bleeding, large endometriotic rectal nodules, or have a family history of bowel cancer.

While many studies have found that surgical resection of DIE improves pain and quality of life, surgery can have significant complications.12 Observation is adequate for asymptomatic patients with DIE. Medical treatment may be offered to patients with mild pain (there is no evidence of a reduction in lesion size with medical therapy). In cases of surgical treatment, we encourage the involvement of a multidisciplinary surgical team to reduce complications and optimize outcomes.

Patients with DIE, significant pain (VAS score, >7), and multiple failed in vitro fertilization treatments are candidates for surgery. When bowel endometriosis is noted on imaging, factors such as size, depth, number of lesions, circumferential involvement, and distance from the anal verge are all used to determine the surgical approach. Rectosigmoid lesions smaller than 3 cm can be treated more conservatively—for example, with shaving or anterior resection with manual repair using disk staplers. Segmental resection generally is indicated for rectosigmoid lesions larger than 3 cm, involvement deeper than the submucosal layer, multiple lesions, circumferential involvement of more than 40%, and the presence of obstructed bowel symptoms.13,14

In patients with DIE who present with both infertility and pain, antimüllerian hormone level and TVUS follicular count are used to evaluate ovarian reserve. As surgical treatment may further reduce ovarian reserve in patients with DIE and infertility, we counsel them regarding assisted reproductive technology options before surgery.

CASE Resolved

After thorough discussion, Mary opts to try a different combination oral contraceptive pill formulation. The pills improve her pain symptoms significantly (VAS score, 4), and she decides to forgo surgery. She will be followed up closely on an outpatient basis with serial TVUS imaging.

Individualize management based on patient parameters

Imaging has been used for the nonsurgical diagnosis of DIE for many years, and this practice increasingly is being accepted and adopted. A presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis can be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms obtained from a thorough history and physical examination, in addition to the absence of imaging findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis.

According to guidelines from major ObGyn societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, empiric medical therapy (including combination oral contraceptives, progesterone-containing formulations, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) can be considered for patients with presumed endometriosis presenting with pain.15

When surgery is chosen, the surgeon must obtain crucial information on the characteristics of the lesion(s) and involve a multidisciplinary team to achieve the best outcomes for the patient.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789-1799.

- Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML, Peterson CM, et al; ENDO Study Working Group. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):360-365.

- Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(4):585-596.

- Bellelis P, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Gonzales M, Baracat EC, Abrao MS. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of pelvic endometriosis--a case series. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2010;56(4):467-471.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(6):595-606.

- Greene R, Stratton P, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Sinaii N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):32-39.

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886-894.

- Abrão MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Chamie LP, Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(12):3092-3097.

- Young SW, Dahiya N, Patel MD, et al. Initial accuracy of and learning curve for transvaginal ultrasound with bowel preparation for deep endometriosis in a US tertiary care center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(7):1170-1176.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223-236.

- de Paula Andres M, Borrelli GM, Kho RM, Abrão MS. The current management of deep endometriosis: a systematic review. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(6):587-596.

- Abrão MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA Jr, Averbach M, Silva LF, Marino de Carvalho F. Endometriosis lesions that compromise the rectum deeper than the inner muscularis layer have more than 40% of the circumference of the rectum affected by the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):280-285.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, Keckstein J, Osuga Y, Chapron C. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(3):329-339.

- Kho RM, Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Neto JS, Zanluchi A, Abrao MS. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms [published online ahead of print]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn2018.01.020.

Endometriosis affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age or, conservatively, about 6.5 million women in the United States.1,2 There are 3 types of endometriosis—superficial, ovarian, and deep—and in the past each of these was assumed to have a distinct pathogenesis.3 Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is the presence of one or more endometriotic nodules deeper than 5 mm. In a study at a large tertiary-care center, 40% of patients with endometriosis had deep disease.4 DIE is associated with more severe pain and infertility.5 In patients with endometriosis, diagnosis is commonly made 7 to 9 years after the initial pelvic pain presentation.6 For these reasons, well-directed history taking and proper evaluation and treatment should be pursued to relieve pain and optimize outcomes.

CASE Young woman with intensifying pelvic pain

Mary is a 26-year-old social worker who presents to her ObGyn with symptoms of worsening pain during as well as outside her periods. What additional information would you want to obtain from Mary, given her chief symptom of pain?

Investigate the type of pain

It is important to ask the patient about her menstrual and sexual history, her thoughts regarding near- and long-term fertility, and the type and severity of her pain symptoms. The 5 pain symptoms specific to pelvic pain are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and noncyclic pelvic pain. A visual analog scale (VAS) for pain as well as pelvic pain questionnaires can be used to guide evaluation options and monitor treatment outcomes. In addition, it is of paramount importance to understand the differential diagnoses that can present as pelvic pain (TABLE).

CASE Continued: Mary’s history

Mary reports that she always has had painful periods and that she was started on oral contraceptive pills for pain control and regulation of her periods soon after the onset of menses, when she was 12 years old. In college, she was prescribed oral contraceptive pills for contraception. Recently engaged, she is interested in becoming pregnant in 3 years.

A year ago, Mary discontinued the pills because of their adverse effects. Now she has severe pain during (VAS score, 8/10) and outside (VAS score, 7) her monthly periods. Because of this pain, she has taken time off from work twice within the past 6 months. She has pain during intercourse (VAS score, 7) and some pain with bowel movements during her menses (VAS score, 4). Pelvic examination reveals a normal-sized uterus and adnexa as well as a tender nodule in the rectovaginal septum.

What diagnostic tests and imaging would you obtain?

Imaging’s role in diagnosis

At many advanced centers for endometriosis, DIE is successfully diagnosed with specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) protocols. In a recent review, MRI’s pooled sensitivity and specificity for rectosigmoid endometriosis were 92% and 96%, respectively.7 Choice of imaging for DIE depends on the skills and experience of the clinicians at each center. At a large referral center in São Paulo, Brazil, TVUS with bowel preparation had better sensitivity and specificity for deep retrocervical and rectosigmoid disease compared with MRI and digital pelvic examination.8 In addition, at a center in the United States, we found that proficiency in performing TVUS for DIE was achieved after 70 to 75 cases, and the exam took an average of only 20 minutes.9

Despite recent advances in imaging, most gynecologic societies still hold that endometriosis is to be definitively diagnosed with histologic confirmation from tissue biopsies during surgery. Although surgery remains the diagnostic gold standard, it does not mean that all patients with pelvic pain should undergo diagnostic laparoscopy with tissue biopsies.

The combination of compelling clinical signs, symptoms, and imaging findings (such as absence of findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis) can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical (that is, clinical) diagnosis of endometriosis. Major societies recommend empiric medical therapy (for example, combination oral contraceptives) for the pain associated with superficial endometriosis.10,11 When there is no response to treatment, or when a patient declines or has contraindications to medical therapy, diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis should be considered.

CASE Continued: Diagnosis

Mary undergoes TVUS with bowel preparation, which reveals a normal uterus and adnexa and the presence of 2 lesions, a 2×1.5-cm retrocervical lesion and a 1.8×2-cm rectosigmoid lesion 9 cm above the anal verge. The rectosigmoid lesion involves the external muscularis and compromises 30% of the bowel circumference.

How would you manage the bowel DIE?

Read about management options and individualized care.

Management options: Factor in the variables

DIE can involve the ureters and bladder, the retrocervical and rectovaginal spaces, the appendix, and the bowel. Lesions can be single or multifocal. Although our institutions’ imaging with MRI and TVUS is highly accurate, we additionally recommend the use of colonoscopy (with directed biopsies if appropriate) to evaluate patients who present with rectal bleeding, large endometriotic rectal nodules, or have a family history of bowel cancer.

While many studies have found that surgical resection of DIE improves pain and quality of life, surgery can have significant complications.12 Observation is adequate for asymptomatic patients with DIE. Medical treatment may be offered to patients with mild pain (there is no evidence of a reduction in lesion size with medical therapy). In cases of surgical treatment, we encourage the involvement of a multidisciplinary surgical team to reduce complications and optimize outcomes.

Patients with DIE, significant pain (VAS score, >7), and multiple failed in vitro fertilization treatments are candidates for surgery. When bowel endometriosis is noted on imaging, factors such as size, depth, number of lesions, circumferential involvement, and distance from the anal verge are all used to determine the surgical approach. Rectosigmoid lesions smaller than 3 cm can be treated more conservatively—for example, with shaving or anterior resection with manual repair using disk staplers. Segmental resection generally is indicated for rectosigmoid lesions larger than 3 cm, involvement deeper than the submucosal layer, multiple lesions, circumferential involvement of more than 40%, and the presence of obstructed bowel symptoms.13,14

In patients with DIE who present with both infertility and pain, antimüllerian hormone level and TVUS follicular count are used to evaluate ovarian reserve. As surgical treatment may further reduce ovarian reserve in patients with DIE and infertility, we counsel them regarding assisted reproductive technology options before surgery.

CASE Resolved

After thorough discussion, Mary opts to try a different combination oral contraceptive pill formulation. The pills improve her pain symptoms significantly (VAS score, 4), and she decides to forgo surgery. She will be followed up closely on an outpatient basis with serial TVUS imaging.

Individualize management based on patient parameters

Imaging has been used for the nonsurgical diagnosis of DIE for many years, and this practice increasingly is being accepted and adopted. A presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis can be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms obtained from a thorough history and physical examination, in addition to the absence of imaging findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis.

According to guidelines from major ObGyn societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, empiric medical therapy (including combination oral contraceptives, progesterone-containing formulations, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) can be considered for patients with presumed endometriosis presenting with pain.15

When surgery is chosen, the surgeon must obtain crucial information on the characteristics of the lesion(s) and involve a multidisciplinary team to achieve the best outcomes for the patient.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endometriosis affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age or, conservatively, about 6.5 million women in the United States.1,2 There are 3 types of endometriosis—superficial, ovarian, and deep—and in the past each of these was assumed to have a distinct pathogenesis.3 Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is the presence of one or more endometriotic nodules deeper than 5 mm. In a study at a large tertiary-care center, 40% of patients with endometriosis had deep disease.4 DIE is associated with more severe pain and infertility.5 In patients with endometriosis, diagnosis is commonly made 7 to 9 years after the initial pelvic pain presentation.6 For these reasons, well-directed history taking and proper evaluation and treatment should be pursued to relieve pain and optimize outcomes.

CASE Young woman with intensifying pelvic pain

Mary is a 26-year-old social worker who presents to her ObGyn with symptoms of worsening pain during as well as outside her periods. What additional information would you want to obtain from Mary, given her chief symptom of pain?

Investigate the type of pain

It is important to ask the patient about her menstrual and sexual history, her thoughts regarding near- and long-term fertility, and the type and severity of her pain symptoms. The 5 pain symptoms specific to pelvic pain are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and noncyclic pelvic pain. A visual analog scale (VAS) for pain as well as pelvic pain questionnaires can be used to guide evaluation options and monitor treatment outcomes. In addition, it is of paramount importance to understand the differential diagnoses that can present as pelvic pain (TABLE).

CASE Continued: Mary’s history

Mary reports that she always has had painful periods and that she was started on oral contraceptive pills for pain control and regulation of her periods soon after the onset of menses, when she was 12 years old. In college, she was prescribed oral contraceptive pills for contraception. Recently engaged, she is interested in becoming pregnant in 3 years.

A year ago, Mary discontinued the pills because of their adverse effects. Now she has severe pain during (VAS score, 8/10) and outside (VAS score, 7) her monthly periods. Because of this pain, she has taken time off from work twice within the past 6 months. She has pain during intercourse (VAS score, 7) and some pain with bowel movements during her menses (VAS score, 4). Pelvic examination reveals a normal-sized uterus and adnexa as well as a tender nodule in the rectovaginal septum.

What diagnostic tests and imaging would you obtain?

Imaging’s role in diagnosis

At many advanced centers for endometriosis, DIE is successfully diagnosed with specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) protocols. In a recent review, MRI’s pooled sensitivity and specificity for rectosigmoid endometriosis were 92% and 96%, respectively.7 Choice of imaging for DIE depends on the skills and experience of the clinicians at each center. At a large referral center in São Paulo, Brazil, TVUS with bowel preparation had better sensitivity and specificity for deep retrocervical and rectosigmoid disease compared with MRI and digital pelvic examination.8 In addition, at a center in the United States, we found that proficiency in performing TVUS for DIE was achieved after 70 to 75 cases, and the exam took an average of only 20 minutes.9

Despite recent advances in imaging, most gynecologic societies still hold that endometriosis is to be definitively diagnosed with histologic confirmation from tissue biopsies during surgery. Although surgery remains the diagnostic gold standard, it does not mean that all patients with pelvic pain should undergo diagnostic laparoscopy with tissue biopsies.

The combination of compelling clinical signs, symptoms, and imaging findings (such as absence of findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis) can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical (that is, clinical) diagnosis of endometriosis. Major societies recommend empiric medical therapy (for example, combination oral contraceptives) for the pain associated with superficial endometriosis.10,11 When there is no response to treatment, or when a patient declines or has contraindications to medical therapy, diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis should be considered.

CASE Continued: Diagnosis

Mary undergoes TVUS with bowel preparation, which reveals a normal uterus and adnexa and the presence of 2 lesions, a 2×1.5-cm retrocervical lesion and a 1.8×2-cm rectosigmoid lesion 9 cm above the anal verge. The rectosigmoid lesion involves the external muscularis and compromises 30% of the bowel circumference.

How would you manage the bowel DIE?

Read about management options and individualized care.

Management options: Factor in the variables

DIE can involve the ureters and bladder, the retrocervical and rectovaginal spaces, the appendix, and the bowel. Lesions can be single or multifocal. Although our institutions’ imaging with MRI and TVUS is highly accurate, we additionally recommend the use of colonoscopy (with directed biopsies if appropriate) to evaluate patients who present with rectal bleeding, large endometriotic rectal nodules, or have a family history of bowel cancer.

While many studies have found that surgical resection of DIE improves pain and quality of life, surgery can have significant complications.12 Observation is adequate for asymptomatic patients with DIE. Medical treatment may be offered to patients with mild pain (there is no evidence of a reduction in lesion size with medical therapy). In cases of surgical treatment, we encourage the involvement of a multidisciplinary surgical team to reduce complications and optimize outcomes.

Patients with DIE, significant pain (VAS score, >7), and multiple failed in vitro fertilization treatments are candidates for surgery. When bowel endometriosis is noted on imaging, factors such as size, depth, number of lesions, circumferential involvement, and distance from the anal verge are all used to determine the surgical approach. Rectosigmoid lesions smaller than 3 cm can be treated more conservatively—for example, with shaving or anterior resection with manual repair using disk staplers. Segmental resection generally is indicated for rectosigmoid lesions larger than 3 cm, involvement deeper than the submucosal layer, multiple lesions, circumferential involvement of more than 40%, and the presence of obstructed bowel symptoms.13,14

In patients with DIE who present with both infertility and pain, antimüllerian hormone level and TVUS follicular count are used to evaluate ovarian reserve. As surgical treatment may further reduce ovarian reserve in patients with DIE and infertility, we counsel them regarding assisted reproductive technology options before surgery.

CASE Resolved

After thorough discussion, Mary opts to try a different combination oral contraceptive pill formulation. The pills improve her pain symptoms significantly (VAS score, 4), and she decides to forgo surgery. She will be followed up closely on an outpatient basis with serial TVUS imaging.

Individualize management based on patient parameters

Imaging has been used for the nonsurgical diagnosis of DIE for many years, and this practice increasingly is being accepted and adopted. A presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis can be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms obtained from a thorough history and physical examination, in addition to the absence of imaging findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis.

According to guidelines from major ObGyn societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, empiric medical therapy (including combination oral contraceptives, progesterone-containing formulations, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) can be considered for patients with presumed endometriosis presenting with pain.15

When surgery is chosen, the surgeon must obtain crucial information on the characteristics of the lesion(s) and involve a multidisciplinary team to achieve the best outcomes for the patient.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789-1799.

- Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML, Peterson CM, et al; ENDO Study Working Group. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):360-365.

- Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(4):585-596.

- Bellelis P, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Gonzales M, Baracat EC, Abrao MS. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of pelvic endometriosis--a case series. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2010;56(4):467-471.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(6):595-606.

- Greene R, Stratton P, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Sinaii N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):32-39.

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886-894.

- Abrão MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Chamie LP, Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(12):3092-3097.

- Young SW, Dahiya N, Patel MD, et al. Initial accuracy of and learning curve for transvaginal ultrasound with bowel preparation for deep endometriosis in a US tertiary care center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(7):1170-1176.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223-236.

- de Paula Andres M, Borrelli GM, Kho RM, Abrão MS. The current management of deep endometriosis: a systematic review. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(6):587-596.

- Abrão MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA Jr, Averbach M, Silva LF, Marino de Carvalho F. Endometriosis lesions that compromise the rectum deeper than the inner muscularis layer have more than 40% of the circumference of the rectum affected by the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):280-285.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, Keckstein J, Osuga Y, Chapron C. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(3):329-339.

- Kho RM, Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Neto JS, Zanluchi A, Abrao MS. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms [published online ahead of print]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn2018.01.020.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789-1799.

- Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML, Peterson CM, et al; ENDO Study Working Group. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):360-365.

- Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(4):585-596.

- Bellelis P, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Gonzales M, Baracat EC, Abrao MS. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of pelvic endometriosis--a case series. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2010;56(4):467-471.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(6):595-606.

- Greene R, Stratton P, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Sinaii N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):32-39.

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886-894.

- Abrão MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Chamie LP, Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(12):3092-3097.

- Young SW, Dahiya N, Patel MD, et al. Initial accuracy of and learning curve for transvaginal ultrasound with bowel preparation for deep endometriosis in a US tertiary care center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(7):1170-1176.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223-236.

- de Paula Andres M, Borrelli GM, Kho RM, Abrão MS. The current management of deep endometriosis: a systematic review. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(6):587-596.

- Abrão MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA Jr, Averbach M, Silva LF, Marino de Carvalho F. Endometriosis lesions that compromise the rectum deeper than the inner muscularis layer have more than 40% of the circumference of the rectum affected by the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):280-285.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, Keckstein J, Osuga Y, Chapron C. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(3):329-339.

- Kho RM, Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Neto JS, Zanluchi A, Abrao MS. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms [published online ahead of print]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn2018.01.020.

Take-home points

- Specific MRI or TVUS protocols are highly accurate in making a nonsurgical diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).

- The combination of compelling clinical signs and symptoms and absence of imaging findings for DIE can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Empiric medical therapy may provide pain relief.

- Conservative treatment, including observation alone, may be considered in asymptomatic patients with DIE and in those with minimal pain.

- Before surgery, it is imperative to know lesion size, depth, circumferential bowel involvement, and location (or distance from the anal verge in cases of rectosigmoid lesion) to optimize surgical outcomes.

Vaginal morcellation by hand using advanced instrumentation

Read Dr. Kho's Surgical Technique article, "Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most daunting challenges" (August 2014)

Read Dr. Kho's Surgical Technique article, "Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most daunting challenges" (August 2014)

Read Dr. Kho's Surgical Technique article, "Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most daunting challenges" (August 2014)

Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most daunting challenges

Vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred route to benign hysterectomy because it is associated with better outcomes and fewer complications than the laparoscopic and open abdominal approaches.1,2 Yet, despite superior patient outcomes and cost benefits, the rate of vaginal hysterectomy is declining.

According to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the use of vaginal hysterectomy declined from 24.8% in 1998 to 16.7% in 2010.3 In fact, more than 80% of surgeons in the United States now perform fewer than five vaginal procedures in a year.4

The increasing use of other minimally invasive routes, such as laparoscopy and robotics, indicates that most practicing surgeons and recent graduates are choosing these approaches over the vaginal route. In only 3 years, the rate of laparoscopy increased by 6% and robotics increased by almost 10%.3

Many surgeons assume that vaginal hysterectomy exists in a state of suspended animation, with nothing much changed in the way it has been performed over the past few decades. Further, vaginal surgery is difficult to teach and learn, given limitations in exposure and visualization, difficulty in securing hemostasis, and challenges in the removal of the large uterus and adnexae. As a result, vaginal hysterectomy often is thought, erroneously, to be indicated only in procedures involving a small and prolapsing uterus.

To increase the rate of vaginal hysterectomy, we can benefit from experience gained in laparoscopy and robotics—whether we are teachers or learners—while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

In this article, I describe common challenges in vaginal hysterectomy and offer tools and techniques to overcome them:

- achieving and enhancing ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

- the need to work in a long vaginal vault

- the task of securing vascular and thick tissue pedicles when the introitus and vaginal vault are narrow.

The vaginal approach is less costly

Vaginal hysterectomy costs significantly less to perform than other approaches. At a tertiary referral center, vaginal hysterectomy costs approximately $7,000 to $18,000 per case less than laparoscopic, abdominal, and robotic hysterectomy.5 With declining use of vaginal hysterectomy and increasing use of more costly approaches, we face a health-care crisis.

Residents are inadequately trained to perform vaginal hysterectomy

Data reveal that not only are our recent graduates inadequately prepared to perform vaginal hysterectomy, but national health-care dollars and resources are depleted when surgeons choose to perform more costly approaches. As a result, many eligible patients end up deprived of the benefits of a single, concealed, and minimally invasive procedure.

The increase in laparoscopic and robotic approaches to hysterectomy has affected residency training. National case log reports from the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education show that the number of vaginal hysterectomies performed by residents as “primary surgeons” decreased by 40%, from a mean of 35 cases in 2002 to 19 cases in 2012.6 A recent survey found that only 28% of graduating residents were “completely prepared” to perform a vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 58% for abdominal hysterectomy, 22% for laparoscopic hysterectomy, and 3% for the robotic approach.7

The rate of vaginal hysterectomy will continue to decline if we perform it in the same manner it was done 30 years ago. The current generation of practicing gynecologists and graduates is choosing to perform the procedure laparoscopically or robotically because of the advantages these technologies provide. It is time that we incorporate features from these minimally invasive approaches to streamline vaginal hysterectomy while maintaining patient safety and containing costs.

Challenges: Ergonomics, exposure, and visualization

In conventional vaginal surgery, the surgeon often is the person who has the best and, sometimes, the sole view. Two bedside assistants are required to hold retractors during the entire case, which can lead to fatigue and muscle strain. Poor lighting also can greatly limit visualization into the pelvic cavity.

Both laparoscopy and robotics provide a well-illuminated and magnified view, with three-dimensional images now available in both platforms. This view is projected to overhead monitors for the entire surgical team to see. Magnification of the pelvic anatomic structures and projection to an external monitor facilitate teaching and learning, better anticipation of the surgical and procedural needs, and overall patient safety.

From robotics, where ergonomics is exemplified, we also learn the importance of surgeon comfort during the procedure.

Solution #1: A self-retaining retractor

A self-retaining system such as the Magrina-Bookwalter vaginal retractor (Symmetry Surgical, Nashville, Tennessee) (FIGURE 1)

Solution #2: Seat the surgeon for an optimal view

With the patient in the lithotomy position and her legs in candy cane stirrups, the surgeon can be seated on a high chair so that the operative field is at the approximate level of the assistants’ view (FIGURE 2)

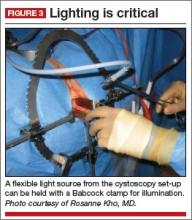

Solution #3: Illuminate the cavity

The deep pelvic cavity can be easily illuminated using a lighted suction tip, a flexible light source (as part of the cystoscopy set) held with a Babcock clamp (FIGURE 3), or a malleable illuminating mat taped to the retractor blades (such as Lightmat surgical illuminator, Lumitex, Inc., Strongsville, Ohio).

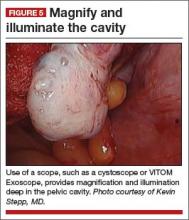

Solution #4: Project the image

Cameras attached to an overhead boom or operating room light handles (FIGURE 4) and an external telescope with integrated illumination, such as a standard cystoscope or VITOM Exoscope (Karl Storz, El Segundo, California) (FIGURE 5) provide both magnification and projection of the procedure to an overhead monitor.

Glass technology (Google, Mountain View, California) also has been utilized in surgery and can be a good application of simultaneous projection and recording of the procedure to an external monitor (FIGURE 6). Google Glass is a wearable computer with an optical head-mounted display. The device, similar to eyeglasses, is voice-activated, thereby allowing the surgeon to record the procedure hands-free. Simultaneous projection to an external monitor allows the entire team in the operating room to be aware of the flow of the procedure.

Challenge: Working in a narrow vaginal vault

Without correct instrumentation, this challenge can be especially daunting. Laparoscopy and robotics have changed the way we perform pelvic surgery by providing advanced instrumentation.

Solution #5: Adapt your instruments

Modified vaginal instruments can be used to facilitate a case. Watch the accompanying VIDEO on the use of improved vaginal instruments during morcellation.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel |

| Click to enlarge >>> |

Among the instruments adaptable for vaginal surgery:

- curving, articulating instruments

- long, curved, and rounded knife handles, which allow for better ergonomics during prolonged morcellation

- modified long retractors and use of a single long vaginal pack provide retraction of loops of bowel and easy access to secure pedicles deep in the pelvis.

All of these instruments are available through Marina Medical in Sunrise, Florida.