User login

Highlights from the 2018 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Scientific Meeting

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Due to an increase in minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy, including vaginal and laparoscopic approaches, gynecologic surgeons may need to turn to simulation training to augment practice and hone skills. Simulation is useful for all surgeons, especially for low-volume surgeons, as a warm-up to sharpen technical skills prior to starting the day’s cases. Additionally, educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency.

In this article, we provide an overview of the 3 approaches to hysterectomy—vaginal, laparoscopic, abdominal—through medical modeling and simulation techniques. We focus on practical issues, including current resources available online, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations of some commonly available vaginal, laparoscopic, and open hysterectomy models.

Simulation directly influences patient safety. Thus, the value of simulation cannot be overstated, as it can increase the quality of health care by improving patient outcomes and lowering overall costs. In 2008, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) founded the Simulations Working Group to establish simulation as a pillar in education for women’s health through collaboration, advocacy, research, and the development and implementation of multidisciplinary simulations-based educational resources and opportunities.

Refer to the ACOG Simulations Working Group Toolkit online to see the objectives, simulation, and videos related to each module. Under the “Hysterectomy” section, you will find how to construct the “flower pot” model for abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, as well as the AAGL vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy webinars. All content is reaffirmed frequently to keep it up to date. You can access the toolkit, with your ACOG login and passcode, at https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Simulations-Consortium/Simulations-Consortium-Tool-Kit.

For a comprehensive gynecology curriculum to include vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal approaches to hysterectomy, refer to ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology page at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/. This page lists the standardized surgical skills curriculum for use in training residents in obstetrics and gynecology by procedure. It includes:

- the objective, description, and assessment of the module

- a description of the simulation

- a description of the surgical procedure

- a quiz that must be passed to proceed to evaluation by a faculty member

- an evaluation form to be downloaded and printed by the learner.

Takeaway. Value of Simulation = Quality (Improved Patient Outcomes) ÷ Direct and Indirect Costs.

Simulation models for training in vaginal hysterectomy

According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15; this number represents the minimum accepted exposure, however, and does not imply competency. Exposure to vaginal hysterectomy in residency training has significantly declined over the years, with a mean of only 19 vaginal hysterectomies performed by the time of graduation in 2014.1

A wide range of simulation models are available that you either can construct or purchase, based on your budget. We discuss 3 such models below.

The Miya model

The Miya Model Pelvic Surgery Training Model (Miyazaki Enterprises) consists of a bony pelvic frame and multiple replaceable and realistic anatomic structures, including the uterus, cervix, and adnexa (1 structure), vagina, bladder, and a few selected muscles and ligaments for pelvic floor disorders (FIGURE 1). The model incorporates features to simulate actual surgical experiences, such as realistic cutting and puncturing tensions, palpable surgical landmarks, a pressurized vascular system with bleeding for inadequate technique, and an inflatable bladder that can leak water if damaged.

Mounted on a rotating stand with the top of the pelvis open, the Miya model is designed to provide access and visibility, enabling supervising physicians the ability to give immediate guidance and feedback. The interchangeable parts allow the learner to be challenged at the appropriate skill level with the use of a large uterus versus a smaller uterus.

New in 2018 is an “intern” uterus and vagina that have no vascular supply and a single-layer vagina; this model is one-third of the cost of the larger, high-fidelity uterus (which has a vascular supply and additional tissue layers).

The Miya model reusable bony pelvic frame has a one-time cost of a few thousand dollars. Advantages include its high fidelity, low technology, light weight, portability, and quick setup. To view a video of the Miya model, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=49&v=A2RjOgVRclo. To see a simulated vaginal hysterectomy, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=dwiQz4DTyy8.

The gynecologic surgeon and inventor, Dr. Douglas Miyazaki, has improved the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (usually the most challenging for the surgeon) to have a more realistic, slippery feel when palpated.

This model’s weaknesses are its cost (relative to low-fidelity models) and the inability to use energy devices.

Takeaway. The Miya model is a high-fidelity, portable vaginal hysterectomy model with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts

The Gynesim model

The Gynesim Vaginal Hysterectomy Model, developed by Dr. Malcolm “Kip” Mackenzie (Gynesim), is a high-fidelity surgical simulation model constructed from animal tissue to provide realistic training in pelvic surgery (FIGURE 2).

These “real tissue models” are hand-constructed from animal tissue harvested from US Department of Agriculture inspected meat processing centers. The models mimic normal and abnormal abdominal and pelvic anatomy, providing realistic feel (haptics) and response to all surgical energy modalities. The “cassette” tissues are placed within a vaginal approach platform, which is portable.

Each model (including a 120- to 240-g uterus, bladder, ureter, uterine artery, cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, and rectum) supports critical gaps in surgical techniques such as peritoneal entry and cuff closure. Gynesim staff set up the entire laboratory, including the simulation models, instruments, and/or cameras; however, surgical energy systems are secured from the host institution.

The advantages of this model are its excellent tissue haptics and the minimal preparation time required from the busy gynecologic teaching faculty, as the company performs the setup and breakdown. Disadvantages include the model’s cost (relative to low-fidelity models), that it does not bleed, its one-time use, and the need for technical assistance from the company for setup.

This model can be used for laparoscopic and open hysterectomy approaches, as well as for vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit the Gynesim website at https://www.gynesim.com/vaginal-hysterectomy/.

Takeaway. The high-fidelity Gynesim model can be used to practice vaginal, laparoscopic, or open hysterectomy approaches. It offers excellent tissue haptics, one-time use “cassettes” made from animal tissue, and compatibility with energy devices.

The milk jug model

The milk jug and fabric uterus model, developed by Dr. Dee Fenner, is a low-cost simulation model and an alternative to the flower pot model (described later in this article). The bony pelvis is simulated by a 1-gallon milk carton that is taped to a foam ring. Other materials used to make the uterus are fabric, stuffing, and a needle and thread (or a sewing machine). Each model costs approximately $5 and takes approximately 15 minutes to create. For instructions on how to construct this model, see the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) award-winning video from 2012 at https://vimeo.com/123804677.

The advantages of this model are that it is inexpensive and is a good tool with which novice gynecologic surgeons can learn the basic steps of the procedure. The disadvantages are that it does not bleed, is not compatible with energy devices, and must be constructed by hand (adding considerable time) or with a sewing machine.

Takeaway. The milk jug model is a low-cost, low-fidelity model for the novice surgeon that can be quickly constructed with the use of a sewing machine.

Read about simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy

While overall hysterectomy numbers have remained relatively stable during the last 10 years, the proportion of laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures is increasing in residency training.1 Many toolkits and models are available for practicing skills, from low-fidelity models on which to rehearse laparoscopic techniques (suturing, instrument handling) to high-fidelity models that provide augmented reality views of the abdominal cavity as well as the operating room itself. We offer a sampling of 4 such models below.

The FLS trainer system

The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) Trainer Box (Limbs & Things Ltd) provides hands-on manual skills practice and training for laparoscopic surgery (FIGURE 3). The FLS trainer box uses 5 skills to challenge a surgeon’s dexterity and psychomotor skills. The set includes the trainer box with a camera and light source as well as the equipment needed to perform the 5 FLS tasks (peg transfer, pattern cutting, ligating loop, and intracorporeal and extracorporeal knot tying). The kit does not include laparoscopic instruments or a monitor.

The FLS trainer box with camera costs $1,164. The advantages are that it is portable and can be used to warm-up prior to surgery or for practice to improve technical skills. It is a great tool for junior residents who are learning the basics of laparoscopic surgery. This trainer’s disadvantages are that it is a low-fidelity unit that is procedure agnostic. For more information, visit the Limbs & Things website at https://www.fls-products.com.

Notably, ObGyn residents who graduate after May 31, 2020, will be required to successfully complete the FLS program as a prerequisite for specialty board certification.2 The FLS program is endorsed by the American College of Surgeons and is run through the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. The FLS test is proctored and must be taken at a testing center.

Takeaway. The FLS trainer box is readily available, portable, relatively inexpensive, low-tech, and has valid benchmarks for proficiency. The FLS test will be required for ObGyn residents by 2020.

The SimPraxis software trainer

The SimPraxis Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Trainer (Red Llama, Inc) is an interactive simulation software platform that is available in DVD or USB format (FIGURE 4). The software is designed to review anatomy, surgical instrumentation, and specific steps of the procedure. It provides formative assessments and offers summative feedback for users.

The SimPraxis training software would make a useful tool to familiarize medical students and interns with the basics of the procedure before advancing to other simulation trainers. The software costs $100. For more information, visit https://www.3-dmed.com/product/simpraxis%C3%82%C2%AE-laparoscopic-hysterectomy-trainer.

Takeaway. The SimPraxis software is ideal for novice learners and can be used on a home or office computer.

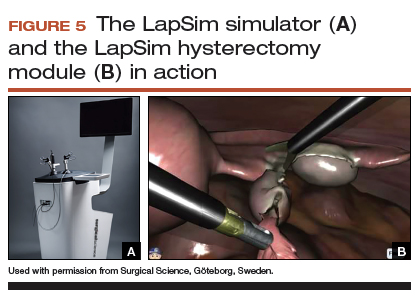

The LapSim virtual reality trainer

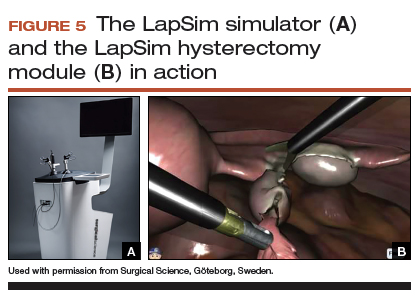

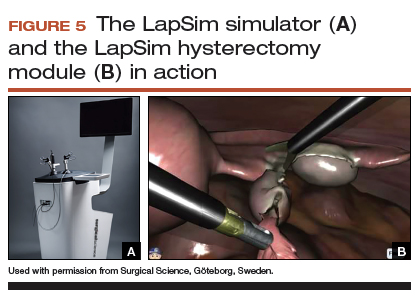

The LapSim Haptic System (Surgical Science) is a virtual reality skills trainer. The hysterectomy module includes right and left uterine artery dissection, vaginal cuff opening, and cuff closure (FIGURE 5). One advantage of this simulator is its haptic feedback system, which enhances the fidelity of the training.

The LapSim simulator includes a training module for students and early learners and modules to improve camera handling. The virtual reality base system costs $70,720, and the hysterectomy software module is an additional $15,600.

For more information, visit the company’s website at https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/. For an informational video, go to https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/video/.

Takeaway. The LapSim is an expensive, high-fidelity, virtual reality simulator with enhanced haptics and software for practicing laparoscopic hysterectomy.

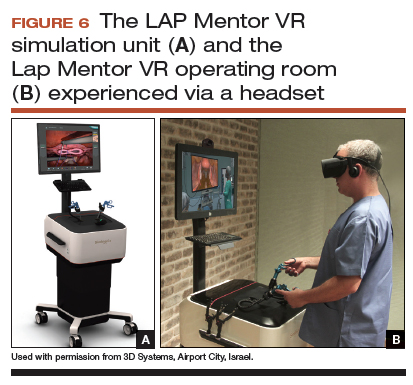

The LAP Mentor virtual reality simulator

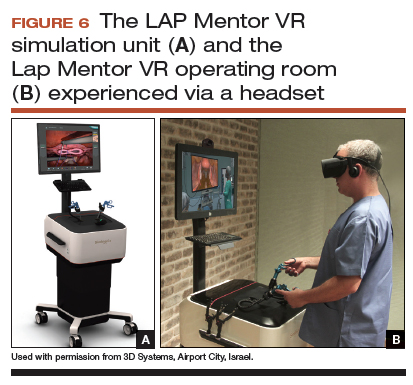

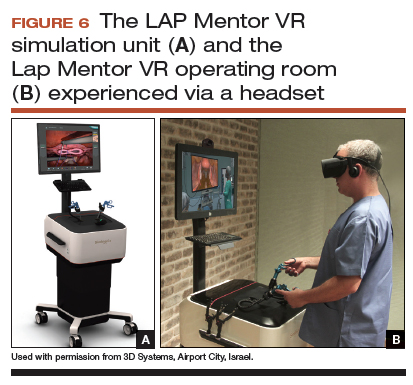

The LAP Mentor VR (3D Systems) is another virtual reality simulator that has modules for laparoscopic hysterectomy and cuff closure (FIGURE 6). The trainee uses a virtual reality headset and becomes fully immersed in the operating room environment with audio and visual cues that mimic a real surgical experience.

The hysterectomy module allows the user to manipulate the uterus, identify the ureters, divide the superior pedicles, mobilize the bladder, expose and divide the uterine artery, and perform the colpotomy. The cuff closure module allows the user to suture the vaginal cuff using barbed suture. The module also can expose the learner to complications, such as bladder, ureteral, colon, or vascular injury.

The LAP Mentor VR base system costs $84,000 and the modules cost about $15,000. For additional information, visit the company’s website at http://simbionix.com/simulators/lap-mentor/lap-mentor-vr-or/.

Takeaway. The LAP Mentor is an expensive, high-fidelity simulation platform with a virtual reality headset that simulates a laparoscopic hysterectomy (with complications) in the operating room.

Read about simulations models for robot-assisted lap hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy.

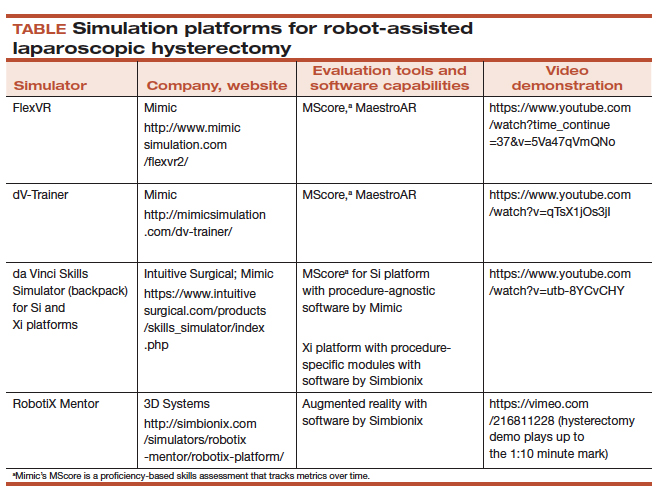

Simulation models for training in robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy

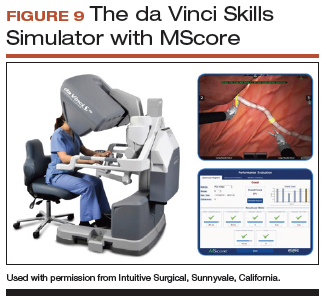

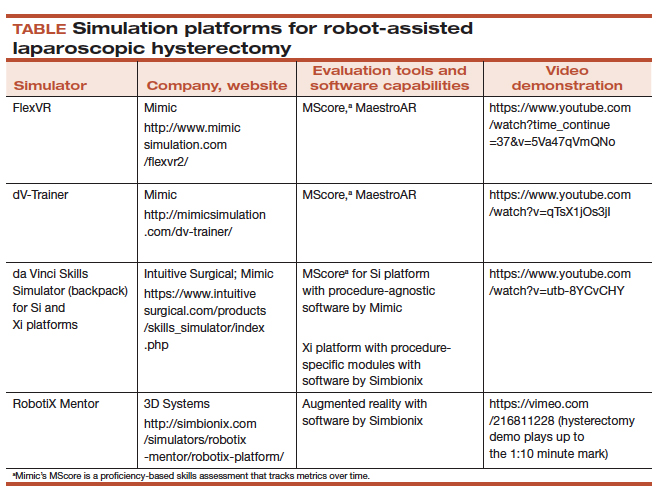

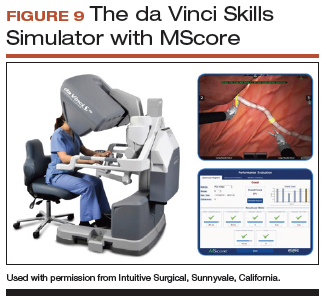

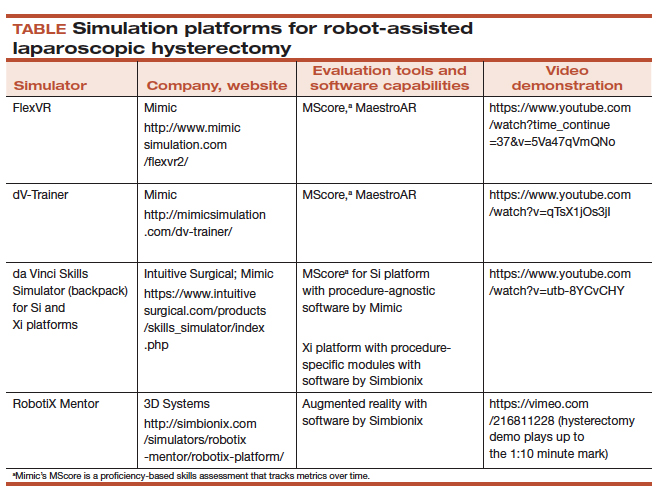

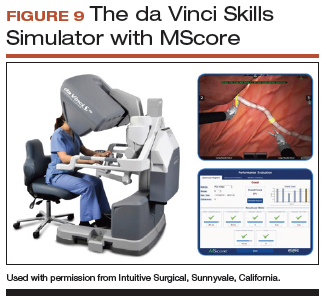

All robot-assisted simulation platforms have highly realistic graphics, and they are expensive (TABLE). However, the da Vinci Skills Simulator (backpack) platform is included with the da Vinci Si and Xi Systems. Note, though, that it can be challenging to access the surgeon console and backpack at institutions with high volumes of robot-assisted surgery.

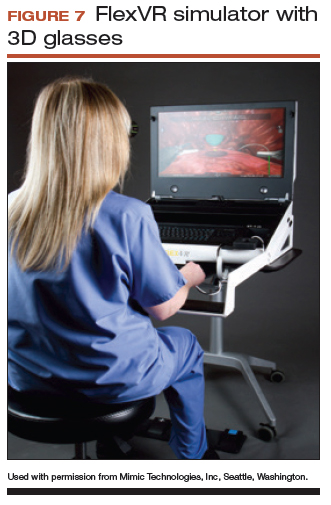

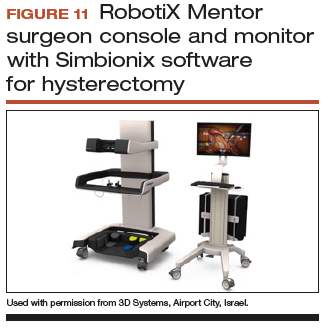

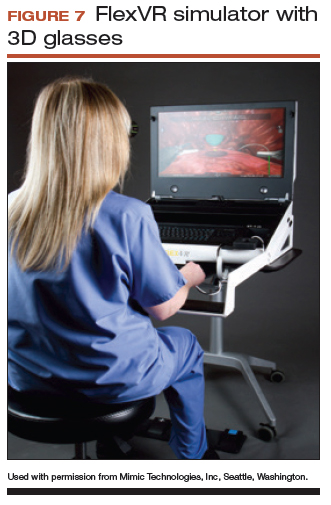

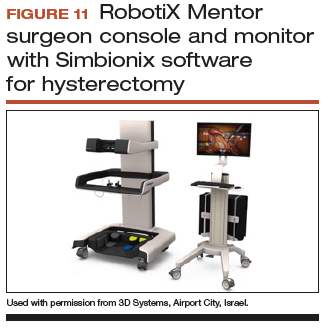

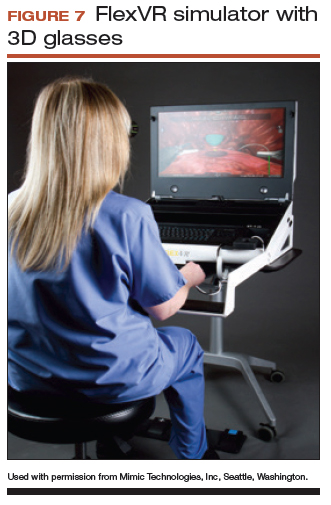

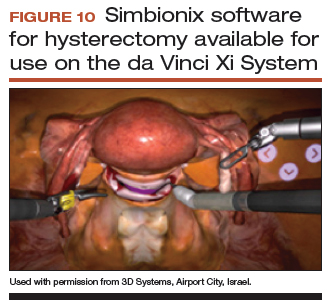

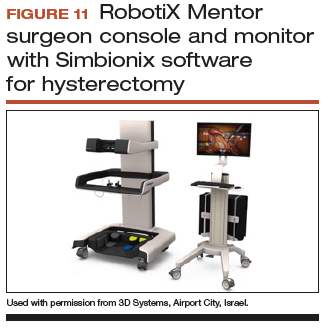

Other options that generally reside outside of the operating room include Mimic’s FlexVR and dV-Trainer and the Robotix Mentor by 3D Systems (FIGURES 7–11). Mimic’s new technology, called MaestroAR (augmented reality), allows trainees to manipulate virtual robotic instruments to interact with anatomic regions within augmented 3D surgical video footage, with narration and instruction by Dr. Arnold Advincula.

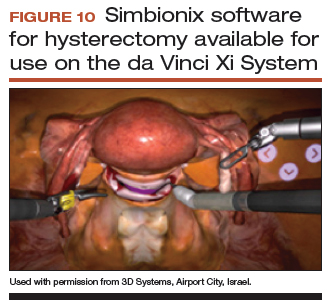

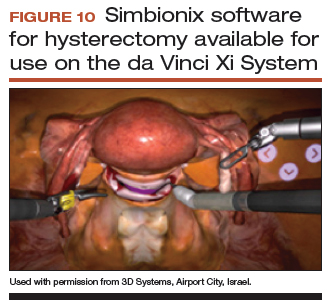

Newer software by Simbionix allows augmented reality to assist the simulation of robot-assisted hysterectomy with the da Vinci Xi backpack and RobotiX platforms.

Models for training in abdominal hysterectomy

In the last 10 years, there has been a 30% decrease in the number of abdominal hysterectomies performed by residents.1 Because of this decline in operating room experience, simulation training can be an important tool to bolster residency experience.

There are not many simulation models available for teaching abdominal hysterectomy, but here we discuss 2 that we utilize in our residency program.

Adaptable task trainer

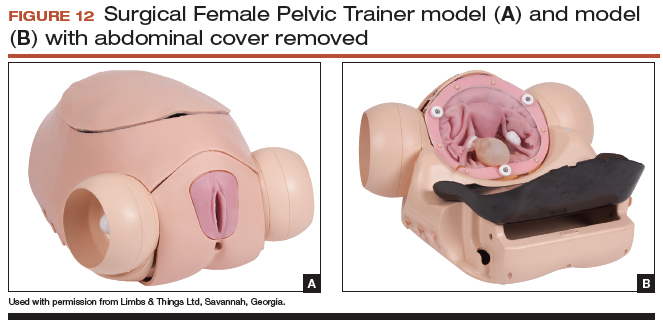

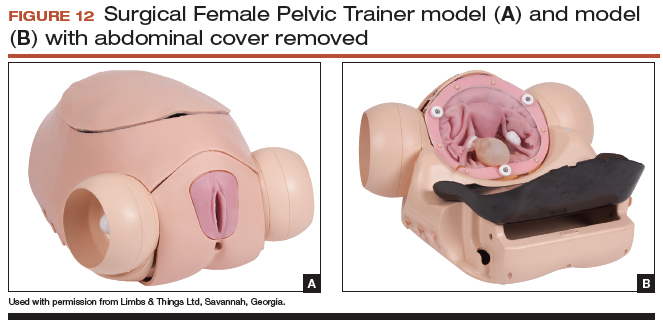

The Surgical Female Pelvic Trainer (SFPT) (Limbs & Things Ltd), a pelvic task trainer primarily used for simulation of laparoscopic hysterectomy, can be adapted for abdominal hysterectomy by removing the abdominal cover (FIGURE 12). This trainer can be used with simulated blood to increase the realism of training. The SFPT trainer costs $2,190. For more information, go to https://www.limbsandthings.com/us/our-products/details/surgical-female-pelvic-trainer-sfpt-mk-2.

Takeaway. The SFPT is a medium-fidelity task trainer with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts.

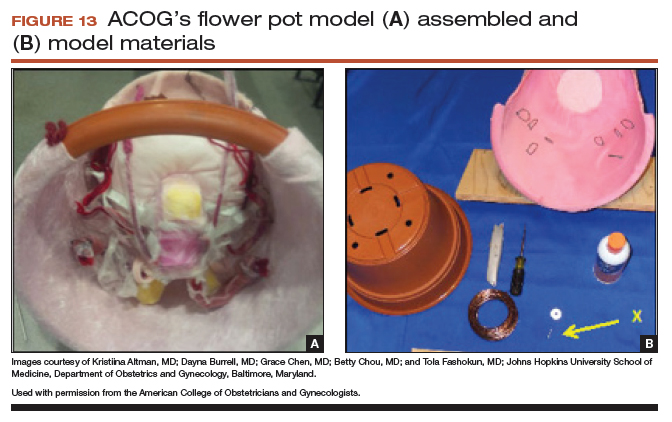

ACOG’s do-it-yourself flower pot model

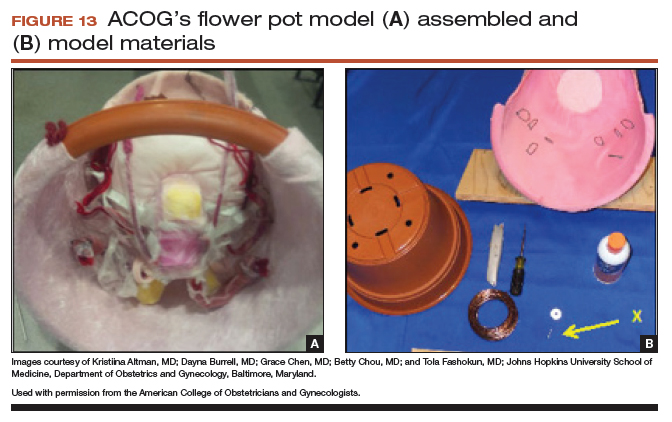

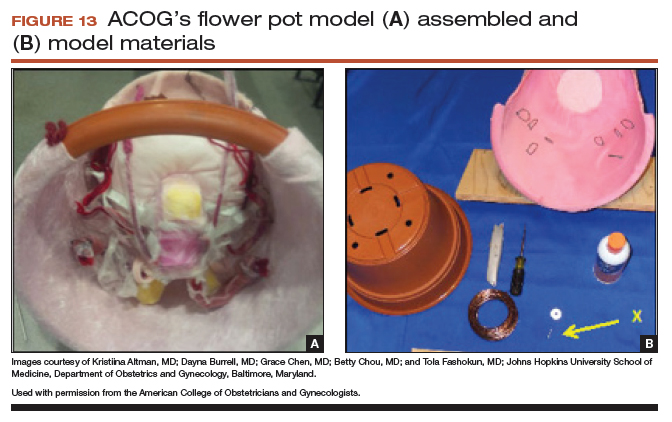

The flower pot model (developed by the ACOG Simulation Working Group, Washington, DC) is a comprehensive educational package that includes learning objectives, simulation construction instructions, content review of the abdominal hysterectomy, quiz, and evaluation form.3 ACOG has endorsed this low-cost model for residency education. Each model costs approximately $20, and the base (flower pot) is reusable (FIGURE 13).Construction time for each model is 30 to 60 minutes, and learners can participate in the construction. This can aid in anatomy review and familiarization with the model prior to training in the surgical procedure.

The learning objectives, content review, quiz, and evaluation form can be used for the flower pot model or for high-fidelity models.

The advantages of this model are the low cost and that it provides enough fidelity to teach each of the critical steps of the procedure. The disadvantages include that it is a lower-fidelity model, requires a considerable amount of time for construction, does not bleed, and is not compatible with energy devices. This model also can be used for training in laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum website at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/.

Takeaway. ACOG’s flower pot model for hysterectomy training is a comprehensive, low-cost, low-fidelity simulation model that requires significant setup time.

Simulation’s offerings

Simulation training is the present and future of medicine that bridges the gap between textbook learning and technical proficiency. Although in this article we describe only a handful of the simulation resources available, we hope that you will incorporate such tools into your practice for continuing education and skill development. Utilize peer-reviewed resources, such as the ACOG curriculum module and evaluation tools for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal hysterectomy, which can be used with any simulation model to provide a comprehensive and complimentary learning experience.

The future of health care depends on the commitment and ingenuity of educators who embrace medical simulation’s purpose: improved patient safety, effectiveness, and efficiency. Join the movement!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucheri E, Zurawin RK, Einarsson JI. Trends in reported resident surgical experience in hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):1067–1070.

- American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ABOG announces new eligibility requirement for board certification. https://www.abog.org/new/ABOG_FLS.aspx. Published January 22, 2018. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Altman K, Burrell D, Chen G, Chou B, Fashokun T. Surgical curriculum in obstetrics and gynecology: vaginal hysterectomy simulation. https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/scog008/Simulation.cfm. Published December 2014. Accessed April 10, 2018.

Due to an increase in minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy, including vaginal and laparoscopic approaches, gynecologic surgeons may need to turn to simulation training to augment practice and hone skills. Simulation is useful for all surgeons, especially for low-volume surgeons, as a warm-up to sharpen technical skills prior to starting the day’s cases. Additionally, educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency.

In this article, we provide an overview of the 3 approaches to hysterectomy—vaginal, laparoscopic, abdominal—through medical modeling and simulation techniques. We focus on practical issues, including current resources available online, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations of some commonly available vaginal, laparoscopic, and open hysterectomy models.

Simulation directly influences patient safety. Thus, the value of simulation cannot be overstated, as it can increase the quality of health care by improving patient outcomes and lowering overall costs. In 2008, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) founded the Simulations Working Group to establish simulation as a pillar in education for women’s health through collaboration, advocacy, research, and the development and implementation of multidisciplinary simulations-based educational resources and opportunities.

Refer to the ACOG Simulations Working Group Toolkit online to see the objectives, simulation, and videos related to each module. Under the “Hysterectomy” section, you will find how to construct the “flower pot” model for abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, as well as the AAGL vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy webinars. All content is reaffirmed frequently to keep it up to date. You can access the toolkit, with your ACOG login and passcode, at https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Simulations-Consortium/Simulations-Consortium-Tool-Kit.

For a comprehensive gynecology curriculum to include vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal approaches to hysterectomy, refer to ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology page at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/. This page lists the standardized surgical skills curriculum for use in training residents in obstetrics and gynecology by procedure. It includes:

- the objective, description, and assessment of the module

- a description of the simulation

- a description of the surgical procedure

- a quiz that must be passed to proceed to evaluation by a faculty member

- an evaluation form to be downloaded and printed by the learner.

Takeaway. Value of Simulation = Quality (Improved Patient Outcomes) ÷ Direct and Indirect Costs.

Simulation models for training in vaginal hysterectomy

According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15; this number represents the minimum accepted exposure, however, and does not imply competency. Exposure to vaginal hysterectomy in residency training has significantly declined over the years, with a mean of only 19 vaginal hysterectomies performed by the time of graduation in 2014.1

A wide range of simulation models are available that you either can construct or purchase, based on your budget. We discuss 3 such models below.

The Miya model

The Miya Model Pelvic Surgery Training Model (Miyazaki Enterprises) consists of a bony pelvic frame and multiple replaceable and realistic anatomic structures, including the uterus, cervix, and adnexa (1 structure), vagina, bladder, and a few selected muscles and ligaments for pelvic floor disorders (FIGURE 1). The model incorporates features to simulate actual surgical experiences, such as realistic cutting and puncturing tensions, palpable surgical landmarks, a pressurized vascular system with bleeding for inadequate technique, and an inflatable bladder that can leak water if damaged.

Mounted on a rotating stand with the top of the pelvis open, the Miya model is designed to provide access and visibility, enabling supervising physicians the ability to give immediate guidance and feedback. The interchangeable parts allow the learner to be challenged at the appropriate skill level with the use of a large uterus versus a smaller uterus.

New in 2018 is an “intern” uterus and vagina that have no vascular supply and a single-layer vagina; this model is one-third of the cost of the larger, high-fidelity uterus (which has a vascular supply and additional tissue layers).

The Miya model reusable bony pelvic frame has a one-time cost of a few thousand dollars. Advantages include its high fidelity, low technology, light weight, portability, and quick setup. To view a video of the Miya model, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=49&v=A2RjOgVRclo. To see a simulated vaginal hysterectomy, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=dwiQz4DTyy8.

The gynecologic surgeon and inventor, Dr. Douglas Miyazaki, has improved the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (usually the most challenging for the surgeon) to have a more realistic, slippery feel when palpated.

This model’s weaknesses are its cost (relative to low-fidelity models) and the inability to use energy devices.

Takeaway. The Miya model is a high-fidelity, portable vaginal hysterectomy model with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts

The Gynesim model

The Gynesim Vaginal Hysterectomy Model, developed by Dr. Malcolm “Kip” Mackenzie (Gynesim), is a high-fidelity surgical simulation model constructed from animal tissue to provide realistic training in pelvic surgery (FIGURE 2).

These “real tissue models” are hand-constructed from animal tissue harvested from US Department of Agriculture inspected meat processing centers. The models mimic normal and abnormal abdominal and pelvic anatomy, providing realistic feel (haptics) and response to all surgical energy modalities. The “cassette” tissues are placed within a vaginal approach platform, which is portable.

Each model (including a 120- to 240-g uterus, bladder, ureter, uterine artery, cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, and rectum) supports critical gaps in surgical techniques such as peritoneal entry and cuff closure. Gynesim staff set up the entire laboratory, including the simulation models, instruments, and/or cameras; however, surgical energy systems are secured from the host institution.

The advantages of this model are its excellent tissue haptics and the minimal preparation time required from the busy gynecologic teaching faculty, as the company performs the setup and breakdown. Disadvantages include the model’s cost (relative to low-fidelity models), that it does not bleed, its one-time use, and the need for technical assistance from the company for setup.

This model can be used for laparoscopic and open hysterectomy approaches, as well as for vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit the Gynesim website at https://www.gynesim.com/vaginal-hysterectomy/.

Takeaway. The high-fidelity Gynesim model can be used to practice vaginal, laparoscopic, or open hysterectomy approaches. It offers excellent tissue haptics, one-time use “cassettes” made from animal tissue, and compatibility with energy devices.

The milk jug model

The milk jug and fabric uterus model, developed by Dr. Dee Fenner, is a low-cost simulation model and an alternative to the flower pot model (described later in this article). The bony pelvis is simulated by a 1-gallon milk carton that is taped to a foam ring. Other materials used to make the uterus are fabric, stuffing, and a needle and thread (or a sewing machine). Each model costs approximately $5 and takes approximately 15 minutes to create. For instructions on how to construct this model, see the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) award-winning video from 2012 at https://vimeo.com/123804677.

The advantages of this model are that it is inexpensive and is a good tool with which novice gynecologic surgeons can learn the basic steps of the procedure. The disadvantages are that it does not bleed, is not compatible with energy devices, and must be constructed by hand (adding considerable time) or with a sewing machine.

Takeaway. The milk jug model is a low-cost, low-fidelity model for the novice surgeon that can be quickly constructed with the use of a sewing machine.

Read about simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy

While overall hysterectomy numbers have remained relatively stable during the last 10 years, the proportion of laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures is increasing in residency training.1 Many toolkits and models are available for practicing skills, from low-fidelity models on which to rehearse laparoscopic techniques (suturing, instrument handling) to high-fidelity models that provide augmented reality views of the abdominal cavity as well as the operating room itself. We offer a sampling of 4 such models below.

The FLS trainer system

The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) Trainer Box (Limbs & Things Ltd) provides hands-on manual skills practice and training for laparoscopic surgery (FIGURE 3). The FLS trainer box uses 5 skills to challenge a surgeon’s dexterity and psychomotor skills. The set includes the trainer box with a camera and light source as well as the equipment needed to perform the 5 FLS tasks (peg transfer, pattern cutting, ligating loop, and intracorporeal and extracorporeal knot tying). The kit does not include laparoscopic instruments or a monitor.

The FLS trainer box with camera costs $1,164. The advantages are that it is portable and can be used to warm-up prior to surgery or for practice to improve technical skills. It is a great tool for junior residents who are learning the basics of laparoscopic surgery. This trainer’s disadvantages are that it is a low-fidelity unit that is procedure agnostic. For more information, visit the Limbs & Things website at https://www.fls-products.com.

Notably, ObGyn residents who graduate after May 31, 2020, will be required to successfully complete the FLS program as a prerequisite for specialty board certification.2 The FLS program is endorsed by the American College of Surgeons and is run through the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. The FLS test is proctored and must be taken at a testing center.

Takeaway. The FLS trainer box is readily available, portable, relatively inexpensive, low-tech, and has valid benchmarks for proficiency. The FLS test will be required for ObGyn residents by 2020.

The SimPraxis software trainer

The SimPraxis Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Trainer (Red Llama, Inc) is an interactive simulation software platform that is available in DVD or USB format (FIGURE 4). The software is designed to review anatomy, surgical instrumentation, and specific steps of the procedure. It provides formative assessments and offers summative feedback for users.

The SimPraxis training software would make a useful tool to familiarize medical students and interns with the basics of the procedure before advancing to other simulation trainers. The software costs $100. For more information, visit https://www.3-dmed.com/product/simpraxis%C3%82%C2%AE-laparoscopic-hysterectomy-trainer.

Takeaway. The SimPraxis software is ideal for novice learners and can be used on a home or office computer.

The LapSim virtual reality trainer

The LapSim Haptic System (Surgical Science) is a virtual reality skills trainer. The hysterectomy module includes right and left uterine artery dissection, vaginal cuff opening, and cuff closure (FIGURE 5). One advantage of this simulator is its haptic feedback system, which enhances the fidelity of the training.

The LapSim simulator includes a training module for students and early learners and modules to improve camera handling. The virtual reality base system costs $70,720, and the hysterectomy software module is an additional $15,600.

For more information, visit the company’s website at https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/. For an informational video, go to https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/video/.

Takeaway. The LapSim is an expensive, high-fidelity, virtual reality simulator with enhanced haptics and software for practicing laparoscopic hysterectomy.

The LAP Mentor virtual reality simulator

The LAP Mentor VR (3D Systems) is another virtual reality simulator that has modules for laparoscopic hysterectomy and cuff closure (FIGURE 6). The trainee uses a virtual reality headset and becomes fully immersed in the operating room environment with audio and visual cues that mimic a real surgical experience.

The hysterectomy module allows the user to manipulate the uterus, identify the ureters, divide the superior pedicles, mobilize the bladder, expose and divide the uterine artery, and perform the colpotomy. The cuff closure module allows the user to suture the vaginal cuff using barbed suture. The module also can expose the learner to complications, such as bladder, ureteral, colon, or vascular injury.

The LAP Mentor VR base system costs $84,000 and the modules cost about $15,000. For additional information, visit the company’s website at http://simbionix.com/simulators/lap-mentor/lap-mentor-vr-or/.

Takeaway. The LAP Mentor is an expensive, high-fidelity simulation platform with a virtual reality headset that simulates a laparoscopic hysterectomy (with complications) in the operating room.

Read about simulations models for robot-assisted lap hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy

All robot-assisted simulation platforms have highly realistic graphics, and they are expensive (TABLE). However, the da Vinci Skills Simulator (backpack) platform is included with the da Vinci Si and Xi Systems. Note, though, that it can be challenging to access the surgeon console and backpack at institutions with high volumes of robot-assisted surgery.

Other options that generally reside outside of the operating room include Mimic’s FlexVR and dV-Trainer and the Robotix Mentor by 3D Systems (FIGURES 7–11). Mimic’s new technology, called MaestroAR (augmented reality), allows trainees to manipulate virtual robotic instruments to interact with anatomic regions within augmented 3D surgical video footage, with narration and instruction by Dr. Arnold Advincula.

Newer software by Simbionix allows augmented reality to assist the simulation of robot-assisted hysterectomy with the da Vinci Xi backpack and RobotiX platforms.

Models for training in abdominal hysterectomy

In the last 10 years, there has been a 30% decrease in the number of abdominal hysterectomies performed by residents.1 Because of this decline in operating room experience, simulation training can be an important tool to bolster residency experience.

There are not many simulation models available for teaching abdominal hysterectomy, but here we discuss 2 that we utilize in our residency program.

Adaptable task trainer

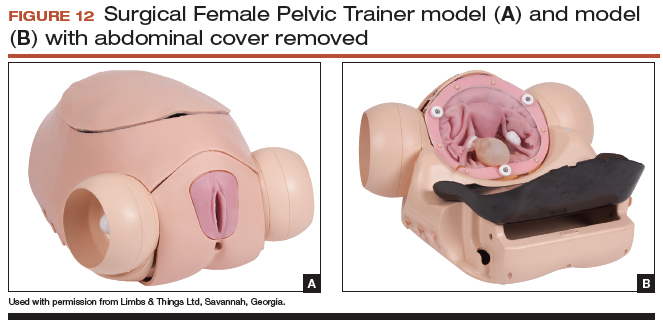

The Surgical Female Pelvic Trainer (SFPT) (Limbs & Things Ltd), a pelvic task trainer primarily used for simulation of laparoscopic hysterectomy, can be adapted for abdominal hysterectomy by removing the abdominal cover (FIGURE 12). This trainer can be used with simulated blood to increase the realism of training. The SFPT trainer costs $2,190. For more information, go to https://www.limbsandthings.com/us/our-products/details/surgical-female-pelvic-trainer-sfpt-mk-2.

Takeaway. The SFPT is a medium-fidelity task trainer with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts.

ACOG’s do-it-yourself flower pot model

The flower pot model (developed by the ACOG Simulation Working Group, Washington, DC) is a comprehensive educational package that includes learning objectives, simulation construction instructions, content review of the abdominal hysterectomy, quiz, and evaluation form.3 ACOG has endorsed this low-cost model for residency education. Each model costs approximately $20, and the base (flower pot) is reusable (FIGURE 13).Construction time for each model is 30 to 60 minutes, and learners can participate in the construction. This can aid in anatomy review and familiarization with the model prior to training in the surgical procedure.

The learning objectives, content review, quiz, and evaluation form can be used for the flower pot model or for high-fidelity models.

The advantages of this model are the low cost and that it provides enough fidelity to teach each of the critical steps of the procedure. The disadvantages include that it is a lower-fidelity model, requires a considerable amount of time for construction, does not bleed, and is not compatible with energy devices. This model also can be used for training in laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum website at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/.

Takeaway. ACOG’s flower pot model for hysterectomy training is a comprehensive, low-cost, low-fidelity simulation model that requires significant setup time.

Simulation’s offerings

Simulation training is the present and future of medicine that bridges the gap between textbook learning and technical proficiency. Although in this article we describe only a handful of the simulation resources available, we hope that you will incorporate such tools into your practice for continuing education and skill development. Utilize peer-reviewed resources, such as the ACOG curriculum module and evaluation tools for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal hysterectomy, which can be used with any simulation model to provide a comprehensive and complimentary learning experience.

The future of health care depends on the commitment and ingenuity of educators who embrace medical simulation’s purpose: improved patient safety, effectiveness, and efficiency. Join the movement!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Due to an increase in minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy, including vaginal and laparoscopic approaches, gynecologic surgeons may need to turn to simulation training to augment practice and hone skills. Simulation is useful for all surgeons, especially for low-volume surgeons, as a warm-up to sharpen technical skills prior to starting the day’s cases. Additionally, educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency.

In this article, we provide an overview of the 3 approaches to hysterectomy—vaginal, laparoscopic, abdominal—through medical modeling and simulation techniques. We focus on practical issues, including current resources available online, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations of some commonly available vaginal, laparoscopic, and open hysterectomy models.

Simulation directly influences patient safety. Thus, the value of simulation cannot be overstated, as it can increase the quality of health care by improving patient outcomes and lowering overall costs. In 2008, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) founded the Simulations Working Group to establish simulation as a pillar in education for women’s health through collaboration, advocacy, research, and the development and implementation of multidisciplinary simulations-based educational resources and opportunities.

Refer to the ACOG Simulations Working Group Toolkit online to see the objectives, simulation, and videos related to each module. Under the “Hysterectomy” section, you will find how to construct the “flower pot” model for abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, as well as the AAGL vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy webinars. All content is reaffirmed frequently to keep it up to date. You can access the toolkit, with your ACOG login and passcode, at https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Simulations-Consortium/Simulations-Consortium-Tool-Kit.

For a comprehensive gynecology curriculum to include vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal approaches to hysterectomy, refer to ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology page at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/. This page lists the standardized surgical skills curriculum for use in training residents in obstetrics and gynecology by procedure. It includes:

- the objective, description, and assessment of the module

- a description of the simulation

- a description of the surgical procedure

- a quiz that must be passed to proceed to evaluation by a faculty member

- an evaluation form to be downloaded and printed by the learner.

Takeaway. Value of Simulation = Quality (Improved Patient Outcomes) ÷ Direct and Indirect Costs.

Simulation models for training in vaginal hysterectomy

According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15; this number represents the minimum accepted exposure, however, and does not imply competency. Exposure to vaginal hysterectomy in residency training has significantly declined over the years, with a mean of only 19 vaginal hysterectomies performed by the time of graduation in 2014.1

A wide range of simulation models are available that you either can construct or purchase, based on your budget. We discuss 3 such models below.

The Miya model

The Miya Model Pelvic Surgery Training Model (Miyazaki Enterprises) consists of a bony pelvic frame and multiple replaceable and realistic anatomic structures, including the uterus, cervix, and adnexa (1 structure), vagina, bladder, and a few selected muscles and ligaments for pelvic floor disorders (FIGURE 1). The model incorporates features to simulate actual surgical experiences, such as realistic cutting and puncturing tensions, palpable surgical landmarks, a pressurized vascular system with bleeding for inadequate technique, and an inflatable bladder that can leak water if damaged.

Mounted on a rotating stand with the top of the pelvis open, the Miya model is designed to provide access and visibility, enabling supervising physicians the ability to give immediate guidance and feedback. The interchangeable parts allow the learner to be challenged at the appropriate skill level with the use of a large uterus versus a smaller uterus.

New in 2018 is an “intern” uterus and vagina that have no vascular supply and a single-layer vagina; this model is one-third of the cost of the larger, high-fidelity uterus (which has a vascular supply and additional tissue layers).

The Miya model reusable bony pelvic frame has a one-time cost of a few thousand dollars. Advantages include its high fidelity, low technology, light weight, portability, and quick setup. To view a video of the Miya model, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=49&v=A2RjOgVRclo. To see a simulated vaginal hysterectomy, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=dwiQz4DTyy8.

The gynecologic surgeon and inventor, Dr. Douglas Miyazaki, has improved the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (usually the most challenging for the surgeon) to have a more realistic, slippery feel when palpated.

This model’s weaknesses are its cost (relative to low-fidelity models) and the inability to use energy devices.

Takeaway. The Miya model is a high-fidelity, portable vaginal hysterectomy model with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts

The Gynesim model

The Gynesim Vaginal Hysterectomy Model, developed by Dr. Malcolm “Kip” Mackenzie (Gynesim), is a high-fidelity surgical simulation model constructed from animal tissue to provide realistic training in pelvic surgery (FIGURE 2).

These “real tissue models” are hand-constructed from animal tissue harvested from US Department of Agriculture inspected meat processing centers. The models mimic normal and abnormal abdominal and pelvic anatomy, providing realistic feel (haptics) and response to all surgical energy modalities. The “cassette” tissues are placed within a vaginal approach platform, which is portable.

Each model (including a 120- to 240-g uterus, bladder, ureter, uterine artery, cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, and rectum) supports critical gaps in surgical techniques such as peritoneal entry and cuff closure. Gynesim staff set up the entire laboratory, including the simulation models, instruments, and/or cameras; however, surgical energy systems are secured from the host institution.

The advantages of this model are its excellent tissue haptics and the minimal preparation time required from the busy gynecologic teaching faculty, as the company performs the setup and breakdown. Disadvantages include the model’s cost (relative to low-fidelity models), that it does not bleed, its one-time use, and the need for technical assistance from the company for setup.

This model can be used for laparoscopic and open hysterectomy approaches, as well as for vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit the Gynesim website at https://www.gynesim.com/vaginal-hysterectomy/.

Takeaway. The high-fidelity Gynesim model can be used to practice vaginal, laparoscopic, or open hysterectomy approaches. It offers excellent tissue haptics, one-time use “cassettes” made from animal tissue, and compatibility with energy devices.

The milk jug model

The milk jug and fabric uterus model, developed by Dr. Dee Fenner, is a low-cost simulation model and an alternative to the flower pot model (described later in this article). The bony pelvis is simulated by a 1-gallon milk carton that is taped to a foam ring. Other materials used to make the uterus are fabric, stuffing, and a needle and thread (or a sewing machine). Each model costs approximately $5 and takes approximately 15 minutes to create. For instructions on how to construct this model, see the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) award-winning video from 2012 at https://vimeo.com/123804677.

The advantages of this model are that it is inexpensive and is a good tool with which novice gynecologic surgeons can learn the basic steps of the procedure. The disadvantages are that it does not bleed, is not compatible with energy devices, and must be constructed by hand (adding considerable time) or with a sewing machine.

Takeaway. The milk jug model is a low-cost, low-fidelity model for the novice surgeon that can be quickly constructed with the use of a sewing machine.

Read about simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy

While overall hysterectomy numbers have remained relatively stable during the last 10 years, the proportion of laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures is increasing in residency training.1 Many toolkits and models are available for practicing skills, from low-fidelity models on which to rehearse laparoscopic techniques (suturing, instrument handling) to high-fidelity models that provide augmented reality views of the abdominal cavity as well as the operating room itself. We offer a sampling of 4 such models below.

The FLS trainer system

The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) Trainer Box (Limbs & Things Ltd) provides hands-on manual skills practice and training for laparoscopic surgery (FIGURE 3). The FLS trainer box uses 5 skills to challenge a surgeon’s dexterity and psychomotor skills. The set includes the trainer box with a camera and light source as well as the equipment needed to perform the 5 FLS tasks (peg transfer, pattern cutting, ligating loop, and intracorporeal and extracorporeal knot tying). The kit does not include laparoscopic instruments or a monitor.

The FLS trainer box with camera costs $1,164. The advantages are that it is portable and can be used to warm-up prior to surgery or for practice to improve technical skills. It is a great tool for junior residents who are learning the basics of laparoscopic surgery. This trainer’s disadvantages are that it is a low-fidelity unit that is procedure agnostic. For more information, visit the Limbs & Things website at https://www.fls-products.com.

Notably, ObGyn residents who graduate after May 31, 2020, will be required to successfully complete the FLS program as a prerequisite for specialty board certification.2 The FLS program is endorsed by the American College of Surgeons and is run through the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. The FLS test is proctored and must be taken at a testing center.

Takeaway. The FLS trainer box is readily available, portable, relatively inexpensive, low-tech, and has valid benchmarks for proficiency. The FLS test will be required for ObGyn residents by 2020.

The SimPraxis software trainer

The SimPraxis Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Trainer (Red Llama, Inc) is an interactive simulation software platform that is available in DVD or USB format (FIGURE 4). The software is designed to review anatomy, surgical instrumentation, and specific steps of the procedure. It provides formative assessments and offers summative feedback for users.

The SimPraxis training software would make a useful tool to familiarize medical students and interns with the basics of the procedure before advancing to other simulation trainers. The software costs $100. For more information, visit https://www.3-dmed.com/product/simpraxis%C3%82%C2%AE-laparoscopic-hysterectomy-trainer.

Takeaway. The SimPraxis software is ideal for novice learners and can be used on a home or office computer.

The LapSim virtual reality trainer

The LapSim Haptic System (Surgical Science) is a virtual reality skills trainer. The hysterectomy module includes right and left uterine artery dissection, vaginal cuff opening, and cuff closure (FIGURE 5). One advantage of this simulator is its haptic feedback system, which enhances the fidelity of the training.

The LapSim simulator includes a training module for students and early learners and modules to improve camera handling. The virtual reality base system costs $70,720, and the hysterectomy software module is an additional $15,600.

For more information, visit the company’s website at https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/. For an informational video, go to https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/video/.

Takeaway. The LapSim is an expensive, high-fidelity, virtual reality simulator with enhanced haptics and software for practicing laparoscopic hysterectomy.

The LAP Mentor virtual reality simulator

The LAP Mentor VR (3D Systems) is another virtual reality simulator that has modules for laparoscopic hysterectomy and cuff closure (FIGURE 6). The trainee uses a virtual reality headset and becomes fully immersed in the operating room environment with audio and visual cues that mimic a real surgical experience.

The hysterectomy module allows the user to manipulate the uterus, identify the ureters, divide the superior pedicles, mobilize the bladder, expose and divide the uterine artery, and perform the colpotomy. The cuff closure module allows the user to suture the vaginal cuff using barbed suture. The module also can expose the learner to complications, such as bladder, ureteral, colon, or vascular injury.

The LAP Mentor VR base system costs $84,000 and the modules cost about $15,000. For additional information, visit the company’s website at http://simbionix.com/simulators/lap-mentor/lap-mentor-vr-or/.

Takeaway. The LAP Mentor is an expensive, high-fidelity simulation platform with a virtual reality headset that simulates a laparoscopic hysterectomy (with complications) in the operating room.

Read about simulations models for robot-assisted lap hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy

All robot-assisted simulation platforms have highly realistic graphics, and they are expensive (TABLE). However, the da Vinci Skills Simulator (backpack) platform is included with the da Vinci Si and Xi Systems. Note, though, that it can be challenging to access the surgeon console and backpack at institutions with high volumes of robot-assisted surgery.

Other options that generally reside outside of the operating room include Mimic’s FlexVR and dV-Trainer and the Robotix Mentor by 3D Systems (FIGURES 7–11). Mimic’s new technology, called MaestroAR (augmented reality), allows trainees to manipulate virtual robotic instruments to interact with anatomic regions within augmented 3D surgical video footage, with narration and instruction by Dr. Arnold Advincula.

Newer software by Simbionix allows augmented reality to assist the simulation of robot-assisted hysterectomy with the da Vinci Xi backpack and RobotiX platforms.

Models for training in abdominal hysterectomy

In the last 10 years, there has been a 30% decrease in the number of abdominal hysterectomies performed by residents.1 Because of this decline in operating room experience, simulation training can be an important tool to bolster residency experience.

There are not many simulation models available for teaching abdominal hysterectomy, but here we discuss 2 that we utilize in our residency program.

Adaptable task trainer

The Surgical Female Pelvic Trainer (SFPT) (Limbs & Things Ltd), a pelvic task trainer primarily used for simulation of laparoscopic hysterectomy, can be adapted for abdominal hysterectomy by removing the abdominal cover (FIGURE 12). This trainer can be used with simulated blood to increase the realism of training. The SFPT trainer costs $2,190. For more information, go to https://www.limbsandthings.com/us/our-products/details/surgical-female-pelvic-trainer-sfpt-mk-2.

Takeaway. The SFPT is a medium-fidelity task trainer with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts.

ACOG’s do-it-yourself flower pot model

The flower pot model (developed by the ACOG Simulation Working Group, Washington, DC) is a comprehensive educational package that includes learning objectives, simulation construction instructions, content review of the abdominal hysterectomy, quiz, and evaluation form.3 ACOG has endorsed this low-cost model for residency education. Each model costs approximately $20, and the base (flower pot) is reusable (FIGURE 13).Construction time for each model is 30 to 60 minutes, and learners can participate in the construction. This can aid in anatomy review and familiarization with the model prior to training in the surgical procedure.

The learning objectives, content review, quiz, and evaluation form can be used for the flower pot model or for high-fidelity models.

The advantages of this model are the low cost and that it provides enough fidelity to teach each of the critical steps of the procedure. The disadvantages include that it is a lower-fidelity model, requires a considerable amount of time for construction, does not bleed, and is not compatible with energy devices. This model also can be used for training in laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum website at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/.

Takeaway. ACOG’s flower pot model for hysterectomy training is a comprehensive, low-cost, low-fidelity simulation model that requires significant setup time.

Simulation’s offerings

Simulation training is the present and future of medicine that bridges the gap between textbook learning and technical proficiency. Although in this article we describe only a handful of the simulation resources available, we hope that you will incorporate such tools into your practice for continuing education and skill development. Utilize peer-reviewed resources, such as the ACOG curriculum module and evaluation tools for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal hysterectomy, which can be used with any simulation model to provide a comprehensive and complimentary learning experience.

The future of health care depends on the commitment and ingenuity of educators who embrace medical simulation’s purpose: improved patient safety, effectiveness, and efficiency. Join the movement!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucheri E, Zurawin RK, Einarsson JI. Trends in reported resident surgical experience in hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):1067–1070.

- American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ABOG announces new eligibility requirement for board certification. https://www.abog.org/new/ABOG_FLS.aspx. Published January 22, 2018. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Altman K, Burrell D, Chen G, Chou B, Fashokun T. Surgical curriculum in obstetrics and gynecology: vaginal hysterectomy simulation. https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/scog008/Simulation.cfm. Published December 2014. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucheri E, Zurawin RK, Einarsson JI. Trends in reported resident surgical experience in hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):1067–1070.

- American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ABOG announces new eligibility requirement for board certification. https://www.abog.org/new/ABOG_FLS.aspx. Published January 22, 2018. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Altman K, Burrell D, Chen G, Chou B, Fashokun T. Surgical curriculum in obstetrics and gynecology: vaginal hysterectomy simulation. https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/scog008/Simulation.cfm. Published December 2014. Accessed April 10, 2018.

High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension to repair enterocele and apical prolapse

- Pelvic anatomy of high intraperitoneal vaginal vault suspension

- Anatomy of the uterosacral ligament

- High uterosacral suspension (complete uterine procidentia)

- High uterosacral suspension (post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse)

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and Christine Vaccaro, DO, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

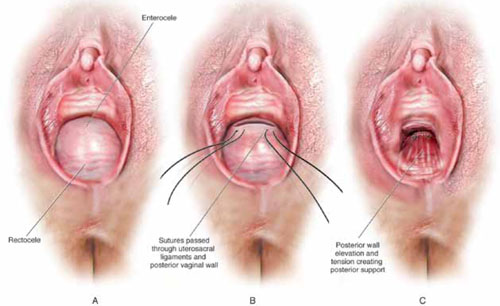

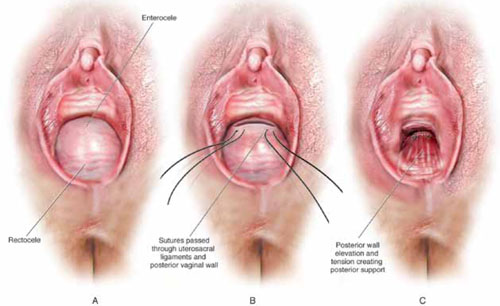

The concept of utilizing the uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff and correct an enterocele is nothing new: As early as 1957, Milton McCall described what became known as the McCall culdoplasty, in which sutures incorporated the uterosacral ligaments into the posterior vaginal vault to obliterate the cul-de-sac and suspend or support the vaginal apex at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.1

Later, in the 1990s, Richardson promoted the concept that, in patients who have pelvic organ prolapse, the uterosacral ligaments do not become attenuated, instead, they break at specific points.

Shull and colleagues took this idea and described how utilizing uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff can be performed vaginally—by passing sutures bilaterally through the uterosacral ligaments near the level of the ischial spine.2

Since Shull described this procedure, numerous published studies have demonstrated outcomes similar to other vaginal suspension procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension.3-5

Potential advantages of a high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are that:

- it provides good apical support without significantly distorting the vaginal axis, making it applicable to all types of vaginal prolapse

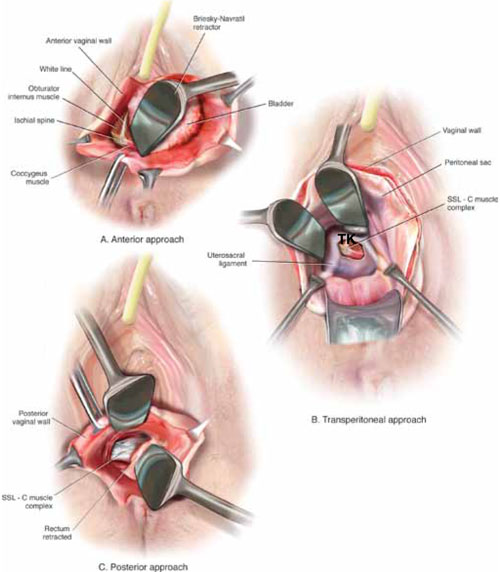

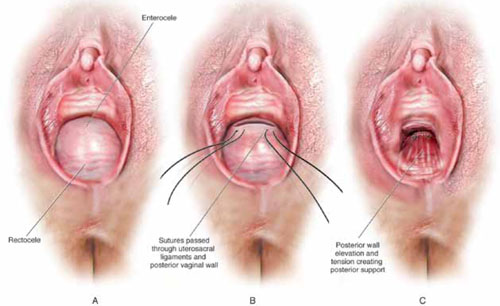

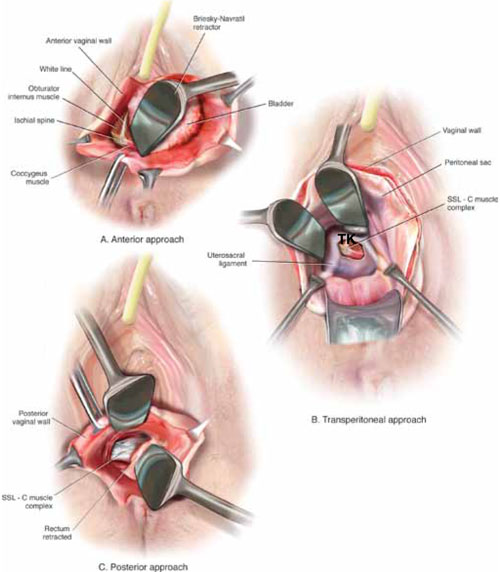

- intraperitoneal passage of sutures can be a lot cleaner and simpler than passing sutures, or anchors, through retroperitoneal structures, such as the sacrospinous ligament (FIGURE 1).

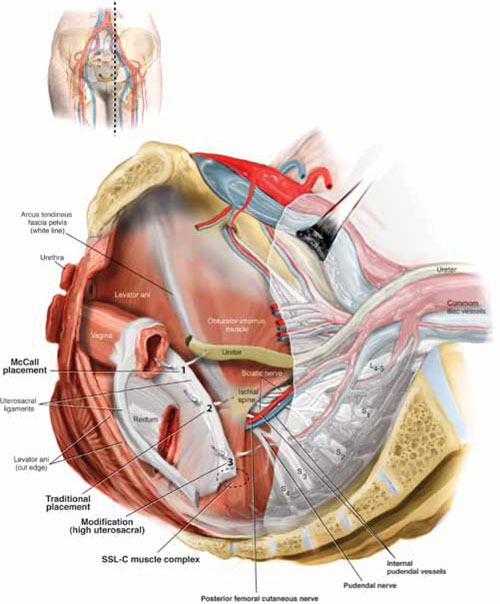

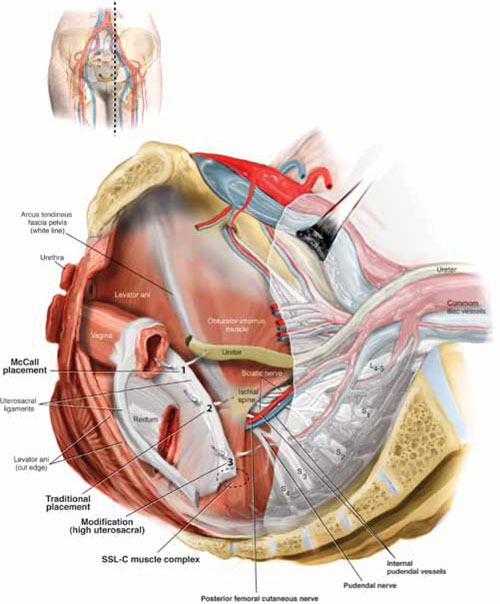

FIGURE 1 Locating intraperitoneal sutures during uterosacral suspension

Cross-section of the pelvic floor shows where sutures are placed as part of McCall culdoplasty (1), traditional uterosacral suspension (2), and modified high uterosacral suspension (3). Note: High uterosacral suspension may involve passing the suture through the sacrospinous ligament–coccygeus (SSL-C) muscle complex (dashed oval) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

A disadvantage of the procedure is that the uterosacral ligament may, at times, lie in close proximity to the ureter. Studies have shown that the ureter can become kinked when sutures in this procedure are passed too far laterally.2-5

High uterosacral suspension has been our operation of choice for 11 years for patients who have pelvic organ prolapse in which the peritoneum is accessible (see “How this procedure evolved in our hands”). In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of the procedure. Four accompanying videos that further illuminate those steps are noted in the text here at appropriate places.(For example, Video #1, immediately below, sets the stage for the step-by-step discussion by reviewing pertinent pelvic anatomy.)

- When we first performed high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension as described by Shull and colleagues,1 we mobilized vaginal muscularis off the epithelium and suspended the epithelium and muscularis separately, making sure that sutures were passed through the anterior and Posterior vaginal walls.

- Initially, we thought that a large cul-de-sac needed to be obliterated in the midline with internal McCall-type stitches that were separate and distinct from the uterosacral suspension sutures. We no longer do this routinely because we believe that the numerous sutures that are passed through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum, effectively obliterate the enterocele and keep down the incidence of recurrent enterocele and high rectocele.

- We have come to realize that sutures placed medial and cephalad to the ischial spine are often passed through a portion of the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex. At times, a small window can be made in the peritoneum that provides direct access to this complex (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 3).

References

1. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365-1374.

1. Enter the peritoneum

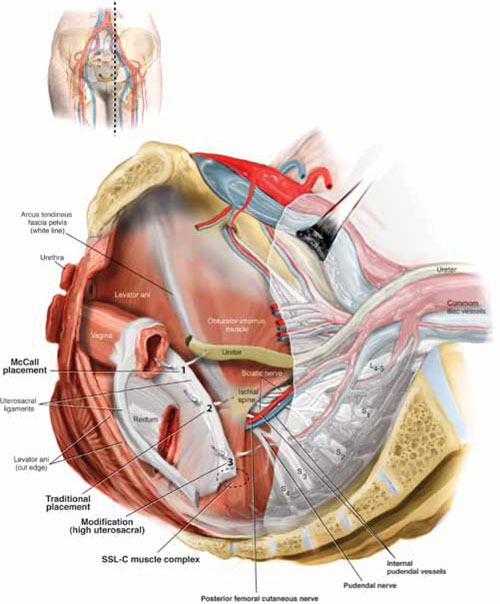

It’s our opinion that, even though extraperitoneal uterosacral suspension procedures have been described, the pertinent anatomic structures (again, see Video #1) are not easily identifiable unless suspension is undertaken intraperitoneally. Entering the peritoneum is, obviously, not a concern if the patient is undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. If the patient has post-hysterectomy prolapse, however, you must be able to isolate an enterocele and enter the peritoneum (follow FIGURE 2, beginning here and through subsequent steps of the procedure).

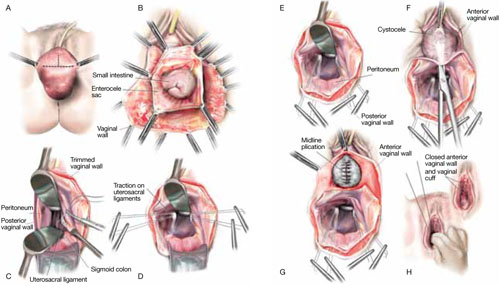

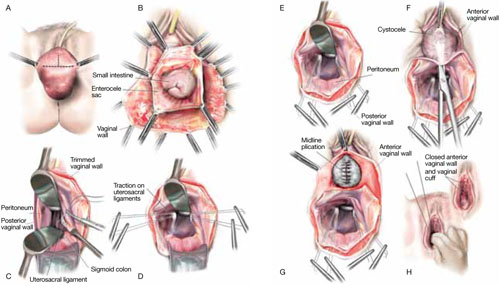

FIGURE 2 Step by step: High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension

A The most prominent portion of the prolapsed vaginal vault is grasped with two Allis clamps. B The vaginal wall is opened up and the enterocele sac is identified and entered. C The bowel is packed high into the pelvis using large laparotomy sponges. The retractor lifts the sponges out of the lower pelvis, thus completely exposing the cul-de-sac. When appropriate traction is placed downward on the uterosacral ligaments with an Allis clamp, the uterosacral ligaments are easily palpated bilaterally. D Delayed absorbable sutures have been passed through the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments on each side, and have been individually tagged.

E Each end of the previously passed sutures is brought out through the posterior peritoneum and the posterior vaginal wall. (A free needle is used to pass both ends of these delayed absorbable sutures through the full thickness of the vaginal wall.) F Anterior colporrhaphy is begun by initiating dissection between the prolapsed bladder and the anterior vaginal wall. G Anterior colporrhaphy is complete. H The vagina has been appropriately trimmed and closed with interrupted or continuous delayed absorbable sutures. Delayed absorbable sutures that were previously brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall are then tied; doing so elevates the prolapsed vaginal vault high up into the hollow of the sacrum.Once you have entered the peritoneum, the cul-de-sac must be relatively free of adhesive disease if you are to be able to continue with this procedure. (See “5 surgical pearls for high ureterosacral vaginal vault suspension”)

- Be prepared to convert to a sacrospinous fixation if you cannot enter the enterocele sac or if the posterior cul-de-sac is obliterated with adhesions

- Pass the sutures through durable tissue so that, when traction is placed on the sutures, there is minimal movement of peritoneum. Doing so might avoid kinking of the ureter.

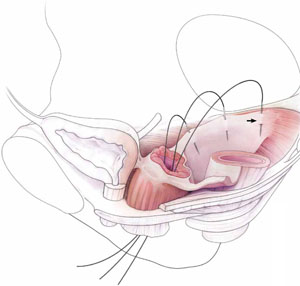

- Pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum. Doing so not only suspends the apex but tremendously facilitates support for the posterior vaginal wall (FIGURE 4).

- When prolapse is very large, excise redundant portions of the upper part of the posterior vaginal wall and peritoneum—making sure, however, that you keep all layers together for performing the suspension. (See VIDEO #4, showing high uterosacral suspension in a patient who has complete uterine procidentia.)

- Do not try to pass a ureteral stent if you do not see indigo carmine dye spill from the ureteral orifices; to do so can be difficult after repair of prolapse, even in the hands of a skilled urologist. It is best instead to:

- identify the offending suture

- cut it

- visualize the spill of dye-colored urine

- proceed with either replacing the cut suture or maintaining the suspension with other, remaining sutures.

In our experience, when we have also performed an anterior repair, the ureter is kinked in at least 50% of cases because of one of the sutures that was used to correct the cystocele.

2. Pack the bowel; expose the uterosacral ligaments

Next, pack the small bowel out of the cul-de-sac to allow easy access and visualization of the uppermost portions of the uterosacral ligament. This is best accomplished by passing large, moistened laparotomy sponges intraperitoneally and elevating them with a large retractor (e.g., Deaver, Breisky-Navrital, Sweetheart).

When the bowel is appropriately packed, the retractor lifts the intestinal contents out of the pelvis, usually allowing easy access to the proximal or uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments (see Video #3, which focuses on the anatomy of the uterosacral ligament).

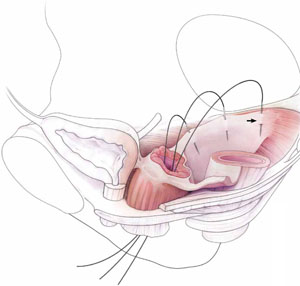

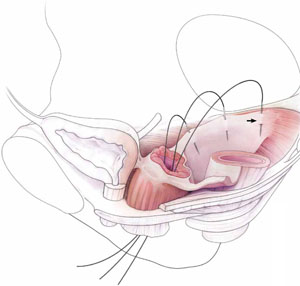

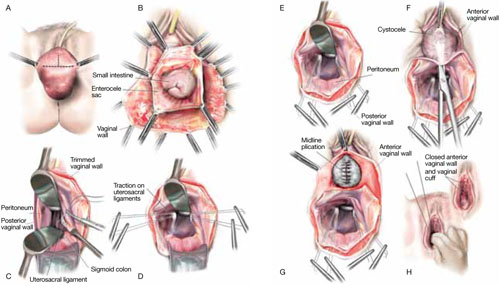

When performing high uterosacral suspension, it is possible to pass sutures through the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex (arrow) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

3. Palpate the ischial spines bilaterally

It’s important that you palpate the ischial spines. Often, the ureter can be palpated against the pelvic sidewall. If you palpate the ischial spines and continue to palpate medially and cephalad, you can usually palpate the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex transperitoneally because a portion of the uterosacral ligament inserts into the sacrospinous ligament.6

If sutures can be passed at this level, the result will (usually) be a vagina that is, at minimum, approximately 9 cm long.

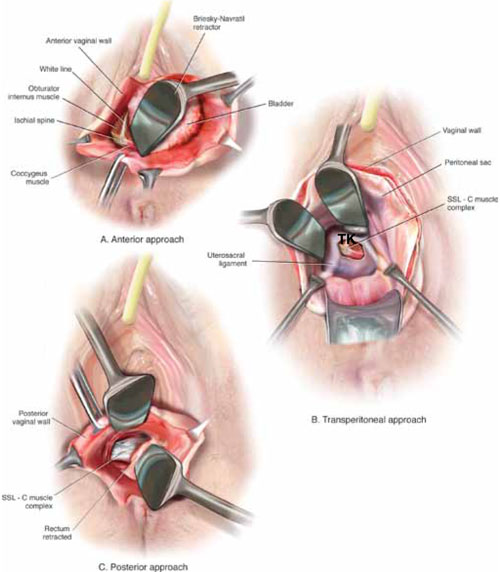

FIGURE 3 Access to the sacrospinous ligament

The sacrospinous ligament can be palpated and exposed along any one of three approaches: anterior paravaginally (A), transperitoneally (B), and posterior pararectally (C).

4. Pass the sutures

We prefer to pass two or three sutures on each side, utilizing a long, straight needle holder. Because we eventually pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, we’ve opted for a delayed absorbable suture—preferably, 0 Vicryl on a CT-2 needle.

A Breisky-Navrital retractor is utilized to retract the sigmoid colon in the opposite direction of the ligament in which the sutures are being passed. At times, attaching a light to a suction device or a retractor is also helpful to visualize this area.

Use an Allis clamp to elevate and apply traction on the distal uterosacral ligament; this facilitates palpation and visualization of the appropriate site for placement of the sutures. The exact area of suture passage is best identified by palpation.

(Note: In early descriptions of this procedure, permanent sutures were utilized; again, we use delayed absorbable sutures because all sutures are brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall. Permanent suture in our approach would be unacceptable because the sutures are tied in the lumen of the vagina. In some other modifications of this procedure, sutures are passed through the muscular layer of the vagina to exclude epithelium; under those circumstances, permanent sutures can be utilized.)

Once the sutures are brought through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall—including the peritoneum, if possible—tag them individually. If the anterior segment is well-supported, close the vaginal incision with a continuous delayed absorbable suture.

Tie the suspension sutures, elevating the apex into the hollow of the sacrum.

If anterior colporrhaphy is needed, perform that repair. Close the anterior vaginal wall as well as the vaginal cuff before tying off the suspension sutures.

5. Ensure that the ureters are patent

After the sutures are tied, instruct the anesthesiologist to administer 5 cc of indigo carmine dye intravenously. Assuming no renal compromise, you should see dye in the bladder 5 to 10 minutes later. If the patient is elderly or if you want to expedite this step, furosemide, 5 to 10 mg, can be given by IV push.