User login

Assessing and treating sexual function after vaginal surgery

Sexual dysfunction is challenging for patients and clinicians. Just as sexual function is multidimensional—with physical and psychosocial elements—sexual dysfunction can likewise have multiple contributing factors, and is often divided into dysfunction of desire, arousal, orgasm, and sex-related pain. Addressing each of these dimensions of sexual dysfunction in relationship to pelvic reconstructive surgery is beyond the scope of this article. Here, we focus on aspects of sexual dysfunction most likely to be reported by patients after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) or urinary incontinence, or for both. We discuss what is known about why sexual dysfunction develops after these procedures; how to assess symptoms when sexual dysfunction occurs; and how best to treat these difficult problems.

CASE Postoperative sexual concerns

Your 62-year-old patient presents 2 weeks after vaginal hysterectomy, uterosacral vault suspension, anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, and retropubic midurethral polypropylene sling placement. She reports feeling tired but otherwise doing well.

The patient returns 8 weeks postoperatively, having just resumed her customary exercise routine, and reports that she is feeling well. Upon questioning, she says that she has not yet attempted to have sexual intercourse with her 70-year-old husband.

The patient returns 6 months later and reports that, although she is doing well overall, she is unable to have sexual intercourse.

How can you help this patient? What next steps in evaluation are indicated? Then, with an understanding of her problem in hand, what treatment options can you offer to her?

Surgery for pelvic-floor disorders and sexual function

The impact of surgery on sexual function is important to discuss with patients preoperatively and postoperatively. Because patients with POP and urinary incontinence have a higher rate of sexual dysfunction at baseline, it is important to know how surgery to correct these conditions can affect sexual function.1 Regrettably, many studies of surgical procedures for POP and urinary incontinence either do not include sexual function outcomes or are not powered to detect differences in these outcomes.

Native-tissue repair. A 2015 systematic review looked at studies of women undergoing native-tissue repair for POP without mesh placement of any kind, including a midurethral sling.2 Based on 9 studies that reported validated sexual function questionnaire scores, investigators determined that sexual function scores generally improved following surgery. Collectively, for studies included in this review that specifically reported the rate of dyspareunia before and after surgery, 47% of women reported improvement in dyspareunia; 39% reported no change; 18% reported deterioration in dyspareunia; and only 4% had de novo dyspareunia.

Colporrhaphy. Posterior colporrhaphy, commonly performed to correct posterior vaginal prolapse, can narrow vaginal caliber and the introitus, potentially causing dyspareunia. Early description of posterior colporrhaphy technique included plication of the levator ani muscles, which was associated with significant risk of dyspareunia postoperatively.3 However, posterior colporrhaphy that involves standard plication of the rectovaginal muscularis or site-specific repair has been reported to have a dyspareunia rate from 7% to 20%.4,5 It is generally recommended, therefore, that levator muscle plication during colporrhaphy be avoided in sexually active women.

Continue to: Vaginal mesh...

Vaginal mesh. Mesh has been used in various surgical procedures to correct pelvic floor disorders. Numerous randomized trials have comparatively evaluated the use of transvaginal polypropylene mesh and native tissue for POP repair, and many of these studies have assessed postoperative sexual function. In a 2013 systematic review on sexual function after POP repair, the authors found no significant difference in postoperative sexual function scores or the dyspareunia rate after vaginal mesh repair (14%) and after native-tissue repair (12%).6

Ask; then ask again

· Talk about sexual function before and after surgery

Remember the basics

· A thorough history and physical exam are paramount

Ask in a different way

· Any of several validated questionnaires can be a valuable adjunct to the history and physical exam

Individualize treatment

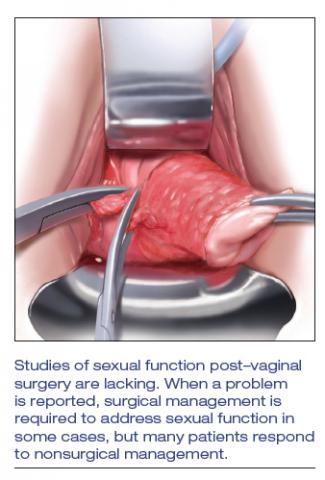

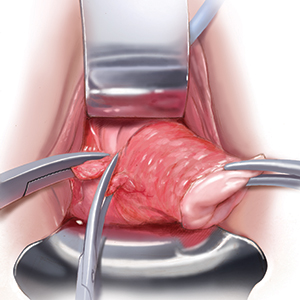

· Many patients respond to nonsurgical treatment, but surgical management is necessary in some cases

Studies of postsurgical sexual function are lacking

Important aspects of sexual function—orgasm, arousal, desire, lubrication, sexual satisfaction, effects on the partner—lack studies. A study of 71 sexually active couples assessed sexual function with questionnaires before and after vaginal native-tissue repair and found that, except for orgasm, all domains improved in female questionnaires. In male partners, interest, sexual drive, and overall satisfaction improved, whereas erection, ejaculation, and orgasm remained unchanged.7

Urinary incontinence during sexual intercourse affects approximately 30% of women with overactive bladder or stress incontinence.8 Several reviews have analyzed data on overall sexual function following urinary incontinence surgery:

- After stress incontinence surgery, the rate of coital incontinence was found to be significantly lower (odds ratio, 0.11).9 In this review, 18 studies, comprising more than 1,500 women, were analyzed, with most participants having undergone insertion of a midurethral mesh sling. Most women (55%) reported no change in overall sexual function, based on validated sexual questionnaire scores; 32% reported improvement; and 13% had deterioration in sexual function.

- As for type of midurethral sling, 2 reviews concluded that there is no difference in sexual function outcomes between retropubic and trans‑obturator sling routes.9,10

Although most studies that have looked at POP and incontinence surgeries show either improvement or no change in sexual function, we stress that sexual function is a secondary outcome in most of those studies, which might not be appropriately powered to detect differences in outcomes. Furthermore, although studies describe dyspareunia and overall sexual function in validated questionnaire scores, most do not evaluate other specific domains of sexual function. It remains unclear, therefore, how POP and incontinence surgeries affect orgasm, desire, arousal, satisfaction, and partner sexual domains; more studies are needed to focus on these areas of female sexual function.

How do we assess these patients?

We do know that sexual function is important to women undergoing gynecologic surgery: In a recent qualitative study of women undergoing pelvic reconstruction, patients rated lack of improvement in sexual function following surgery a “very severe” adverse event.11 Unfortunately, however, sexual activity and function is not always measured before gynecologic surgery. Although specific reporting guidelines do not exist for routine gynecologic surgery, a terminology report from the International Urogynecologic Association/International Continence Society (IUGA/ICS) recommends that sexual activity and partner status be evaluated prior to and following surgical treatment as essential outcomes.12 In addition, the report recommends that sexual pain be assessed prior to and following surgical procedures.12

Ascertain sexual health. First, asking your patients simple questions about sexual function, pain, and bother before and after surgery opens the door to dialogue that allows them, and their partner, to express concerns to you in a safe environment. It also allows you to better understand the significant impact of your surgical interventions on their sexual health.

Questionnaires. Objective measures of vaginal blood flow and engorgement exist, but assessment of sexual activity in the clinical setting is largely limited to self-assessment with questionnaires. Incorporating simple questions, such as “Are you sexually active?,” “Do you have any problems with sexual activity?,” and “Do you have pain with activity?” are likely to be as effective as a more detailed interview and can identify women with sexual concerns.13 Many clinicians are put at a disadvantage, however, because they are faced with the difficult situation of addressing postoperative sexual problems without knowing whether the patient had such reports prior to surgery.

Continue to: Aside from simple screening tools...

Aside from simple screening tools, a number of sexual function questionnaires have been developed. Some are generic, and others are condition-specific:

- Generic questionnaires are typically designed to address the function of a range of women. For example, the Female Sexual Function Index comprises 19 questions. Domains include orgasm, desire, arousal, lubrication, pain and satisfaction.14

- Condition-specific questionnaires of sexual function each have been validated in their target population so that they measure nuances in sexual health relevant to that population. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire—IUGA-Revised includes questions about the domains listed for the generic Index (above) plus questions about the impact of coital incontinence or bulge symptoms on sexual function.12

History-taking. If a woman identifies a problem with sexual function, a thorough history helps elicit whether the condition is lifelong or acquired, situational or general, and, most important, whether or not it is bothersome to her.14,15 It is important not to make assumptions when pursuing this part of the history, and to encourage patients to be candid about how they have sex and with whom.

Physical examination. The patient should undergo a complete physical exam, including 1) a detailed pelvic exam assessing the vulva, vagina, and pelvic-floor musculature, and 2) estrogenization of the tissue.

Partner concerns. For women who have a partner, addressing the concerns of that partner following gynecologic surgery can be useful to the couple: The partner might be concerned about inflicting pain or doing damage during sex after gynecologic surgery.

CASE Informative discussion

While ascertaining her sexual symptoms, your patient reveals to you that she has attempted sexual intercourse on 3 occasions; each time, penetration was too painful to continue. She tells you she did not have this problem before surgery.

The patient says that she has tried water-based lubricants and is using vaginal estrogen 3 times per week, but “nothing helps.” She reports that she is arousable and has been able to achieve orgasm with clitoral stimulation, but would like to have vaginal intercourse. Her husband does have erectile dysfunction, which, she tells you, can make penetration difficult.

On physical examination, you detect mild atrophy. Vaginal length is 9 cm; no narrowing or scarring of the vaginal introitus or canal is seen. No mesh is visible or palpable. The paths of the midurethral sling arms are nontender. However, levator muscles are tender and tense bilaterally.

Given these findings on examination, what steps can you take to relieve your patient’s pain?

What can we offer these patients?

Treating sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery must, as emphasized earlier, be guided by a careful history and physical exam. Doing so is critical to determining the underlying cause. Whenever feasible, offer the least invasive treatment.

The IUGA/ICS terminology report describes several symptoms of postoperative sexual dysfunction12:

- de novo sexual dysfunction

- de novo dyspareunia

- shortened vagina

- tight vagina (introital or vaginal narrowing, or both)

- scarred vagina (including mesh-related problems)

- hispareunia (pain experienced by a male partner after intercourse).

Of course, any one or combination of these symptoms can be present in a given patient. Furthermore, de novo sexual dysfunction, de novo dyspareunia, and hispareunia can have various underlying causes—again, underscoring the importance of the history and exam in determining treatment.

Continue to: Nonsurgical treatment...

Nonsurgical treatment

Nonhormonal vaginal lubricants and moisturizers; vaginal estrogen therapy. Although, in older women, vaginal atrophy is often not a new diagnosis postsurgically, the condition might have been untreated preoperatively and might therefore come into play in sexual dysfunction postoperatively. If a patient reports vaginal dryness or pain upon penetration, assess for vaginal atrophy and, if present, treat accordingly.

Vaginal dilation and physical therapy. A shortened, tight, or scarred vagina might be amenable to therapy with vaginal dilators and physical therapy, but might ultimately require surgery.

Pelvic-floor myalgia or spasm can develop after surgery or, as with atrophy, might have existed preoperatively but was left untreated. Pelvic-floor myalgia should be suspected if the patient describes difficult penetration or a feeling of tightness, even though scarring or constriction of the vagina is not seen on examination. Physical therapy with a specialist in pelvic floor treatment is a first-line treatment for pelvic-floor myalgia,16 and is likely to be a helpful adjunct in many situations, including mesh-related sexual problems.17

Oral or vaginal medications to relax pelvic-floor muscle spasm are an option, although efficacy data are limited. If pain is of longstanding duration and is thought to have a neuropathic component, successful use of tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics, and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors has been reported.18

Surgery

Data are sparse regarding surgical treatment of female sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery. Again, it is clear, however, that the key is carefully assessing each patient and then individualizing treatment. Patients can have any type of dysfunction that a patient who hasn’t had surgery can—but is also at risk of conditions directly related to surgery.

In any patient who has had mesh placed as part of surgery, thorough examination is necessary to determine whether or not the implant is involved in sexual dysfunction. If the dysfunction is an apparent result of surgery performed by another surgeon, make every effort to review the operative report to determine which material was implanted and how it was placed.

Trigger-point injection can be attempted in a patient who has site-specific tenderness that is not clearly associated with tissue obstruction of the vagina or mesh erosion.12,19 Even in areas of apparent banding or scarring related to mesh, trigger-point injection can be attempted to alleviate pain. How often trigger-point injections should be performed is understudied.

If, on examination, tenderness that replicates the dyspareunia is elicited when palpating the levator or obturator internus muscle, pelvic-floor muscle trigger-point injection can be offered (although physical therapy is first-line treatment). Trigger-point injection also can be a useful adjunct in women who have another identified cause of pain but also have developed pelvic-floor muscle spasm.

Not addressing concomitant pelvic-floor myalgia could prevent successful treatment of pain. Inclusion of a pudendal block also might help to alleviate pain.

Continue to: Surgical resection...

Surgical resection. If a skin bridge is clearly observed at the introitus, or if the introitus has been overly narrowed by perineorrhaphy but the remainder of the vagina has adequate length and caliber, surgical resection of the skin bridge might relieve symptoms of difficult penetration. In the case of obstructive perineorrhaphy, an attempt at reversal can be made by incising the perineum vertically but then reapproximating the edges transversely—sometimes referred to as reverse perineorrhaphy.

If scar tissue found elsewhere in the vagina might obstruct penetration, this condition might also be amenable to resection. When scarring is annular, relaxing incisions can be made bilaterally to relieve tension on that tissue; alternatively, it might be necessary to perform a Z-plasty. Nearly always, severe scarring is accompanied by levator myalgia, and a combined approach of surgery and physical therapy is necessary.

Neovagina. It is possible to find vaginal stenosis or shortening, to a varying degree, after surgical prolapse repair, with or without mesh or graft. As discussed, vaginal dilation should be offered but, if this is ineffective, the patient might be a candidate for surgical creation of a neovagina. Numerous techniques have been described for patients with congenital vaginal agenesis, with a few reports of similar techniques used to treat iatrogenic vaginal stenosis or obliteration.

The general principle of all neovagina procedures is to create a space between bladder and rectum of adequate caliber and length for desired sexual function. Reported techniques include a thigh or buttock skin graft, use of bowel or peritoneum, and, recently, a buccal mucosa graft.20,21

Resection or excision of mesh. In patients who develop sexual dysfunction after mesh placement, the problem can be caused by exposure of the mesh in the vagina or erosion into another organ, but can also arise in the absence of exposure or erosion. Patients might have tenderness to palpation at points where the mesh is palpable through the mucosa but not exposed.

Again, complete investigation is necessary to look for mesh involvement in the vagina and, depending on the type of implant, other adjacent organs. Assessing partner symptoms, such as pain and scratches, also can be telling.

If there is palpable tenderness on vaginal examination of the mesh, resection of the vaginal portion might be an option.17 Complete excision of mesh implants can be morbid, however, and might not provide a better outcome than partial excision. The risk of morbidity from complete mesh excision must be weighed against the likelihood that partial excision will not resolve pain and that the patient will require further excision subsequently.17,22 Excising fragmented mesh can be difficult; making every attempt to understand the contribution of mesh to sexual dysfunction is therefore critical to determining how, and how much of, the mesh comes out at the first attempt.

Last, for any woman who opts for surgical intervention to treat pain, you should engage in a discussion to emphasize the multidimensional nature of sexual function and the fact that any surgical intervention might not completely resolve her dysfunction.

Continue to: CASE Discussing options...

CASE Discussing options, choosing an intervention

You discuss the examination findings (no shortening or narrowing of the vagina) with the patient. She is relieved but puzzled as to why she cannot have intercourse. You discuss the tension and t

At 3-month follow-up, she reports great improvement. She is able to have intercourse, although she says she still has discomfort sometimes. She continues to work with the pelvic floor physical therapist and feels optimistic. You plan to see her in 6 months but counsel her to call if symptoms are not improving or are worsening.

It is difficult to counsel patients about sexual function after pelvic reconstructive surgery because data that could guide identification of problems (and how to treat them) are incomplete. Assessingsexual function preoperatively and having an open conversation about risks and benefits of surgery, with specific mention of its impact on sexual health, are critical (see “Key touchpoints in managing sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery”).

It is also crucial to assess sexual function postoperatively as a matter of routine. Validated questionnaires can be a useful adjunct to a thorough history and physical exam, and can help guide your discussions.

Treatment of postop sexual dysfunction must, first, account for the complex nature of sexual function and, second, be individualized, starting with the least invasive options, when feasible.

- Rogers RG. Sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:S199-S201.

- Jha S, Gray T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:321-327.

- Thompson JC, Rogers RG. Surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse and its impact on sexual function. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4:213-220.

- Sung VW, Rardin CR, Raker CA, et al. Porcine subintestinal submucosal graft augmentation for rectocele repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:125-133.

- Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Muir TW, et al. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1762-1771.

- Dietz V, Maher C. Pelvic organ prolapse and sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1853-1857.

- Kuhn A, Brunnmayr G, Stadlmayr W, et al. Male and female sexual function after surgical repair of female organ prolapse. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1324-1334.

- Gray T, Li W, Campbell P, et al. Evaluation of coital incontinence by electronic questionnaire: prevalence, associations and outcomes in women attending a urogynaecology clinic. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:969-978.

- Jha S, Ammenbal M, Metwally M. Impact of incontinence surgery on sexual function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9:34-43.

- Schimpf MO, Rahn DD, Wheeler TL, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:71.e1-e71.e27.

- Dunivan GC, Sussman AL, Jelovsek JE, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Gaining the patient perspective on pelvic floor disorders’ surgical adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:185.e1-e185.e10.

- Rogers RG, Pauls RN, Thakar R, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the assessment of sexual health of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:647-666.

- Plouffe L Jr. Screening for sexual problems through a simple questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:166-169.

- Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Derogatis LR, et al. Recommendations for the clinical evaluation of men and women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7:337-348.

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Atalla E, et al. Definition of sexual dysfunctions in women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation of Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2015;13:135-143.

- Berghmans B. Physiotherapy for pelvic pain and female sexual dysfunction: an untapped resource. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:631-638.

- Cundiff GW, Quinlan DJ, van Rensburg JA, et al. Foundation for an evidence-informed algorithm for treating pelvic floor mesh complications: a review. BJOG. 2018;125:1026-1037.

- Steege JF, Siedhoff MT. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:616-629.

- Wehbe SA, Whitmore K, Kellogg-Spadt S. Urogenital complaints and female sexual dysfunction (part 1). J Sex Med. 2010;7:1704-1713.

- Grimsby GM, Bradshaw K, Baker LA. Autologous buccal mucosa graft augmentation for foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:947-950.

- Morley GW, DeLancey JO. Full-thickness skin graft vaginoplasty for treatment of the stenotic or foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:485-489.

- Pickett SD, Barenberg B, Quiroz LH, et al. The significant morbidity of removing pelvic mesh from multiple vaginal compartments. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1418-1422.

Sexual dysfunction is challenging for patients and clinicians. Just as sexual function is multidimensional—with physical and psychosocial elements—sexual dysfunction can likewise have multiple contributing factors, and is often divided into dysfunction of desire, arousal, orgasm, and sex-related pain. Addressing each of these dimensions of sexual dysfunction in relationship to pelvic reconstructive surgery is beyond the scope of this article. Here, we focus on aspects of sexual dysfunction most likely to be reported by patients after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) or urinary incontinence, or for both. We discuss what is known about why sexual dysfunction develops after these procedures; how to assess symptoms when sexual dysfunction occurs; and how best to treat these difficult problems.

CASE Postoperative sexual concerns

Your 62-year-old patient presents 2 weeks after vaginal hysterectomy, uterosacral vault suspension, anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, and retropubic midurethral polypropylene sling placement. She reports feeling tired but otherwise doing well.

The patient returns 8 weeks postoperatively, having just resumed her customary exercise routine, and reports that she is feeling well. Upon questioning, she says that she has not yet attempted to have sexual intercourse with her 70-year-old husband.

The patient returns 6 months later and reports that, although she is doing well overall, she is unable to have sexual intercourse.

How can you help this patient? What next steps in evaluation are indicated? Then, with an understanding of her problem in hand, what treatment options can you offer to her?

Surgery for pelvic-floor disorders and sexual function

The impact of surgery on sexual function is important to discuss with patients preoperatively and postoperatively. Because patients with POP and urinary incontinence have a higher rate of sexual dysfunction at baseline, it is important to know how surgery to correct these conditions can affect sexual function.1 Regrettably, many studies of surgical procedures for POP and urinary incontinence either do not include sexual function outcomes or are not powered to detect differences in these outcomes.

Native-tissue repair. A 2015 systematic review looked at studies of women undergoing native-tissue repair for POP without mesh placement of any kind, including a midurethral sling.2 Based on 9 studies that reported validated sexual function questionnaire scores, investigators determined that sexual function scores generally improved following surgery. Collectively, for studies included in this review that specifically reported the rate of dyspareunia before and after surgery, 47% of women reported improvement in dyspareunia; 39% reported no change; 18% reported deterioration in dyspareunia; and only 4% had de novo dyspareunia.

Colporrhaphy. Posterior colporrhaphy, commonly performed to correct posterior vaginal prolapse, can narrow vaginal caliber and the introitus, potentially causing dyspareunia. Early description of posterior colporrhaphy technique included plication of the levator ani muscles, which was associated with significant risk of dyspareunia postoperatively.3 However, posterior colporrhaphy that involves standard plication of the rectovaginal muscularis or site-specific repair has been reported to have a dyspareunia rate from 7% to 20%.4,5 It is generally recommended, therefore, that levator muscle plication during colporrhaphy be avoided in sexually active women.

Continue to: Vaginal mesh...

Vaginal mesh. Mesh has been used in various surgical procedures to correct pelvic floor disorders. Numerous randomized trials have comparatively evaluated the use of transvaginal polypropylene mesh and native tissue for POP repair, and many of these studies have assessed postoperative sexual function. In a 2013 systematic review on sexual function after POP repair, the authors found no significant difference in postoperative sexual function scores or the dyspareunia rate after vaginal mesh repair (14%) and after native-tissue repair (12%).6

Ask; then ask again

· Talk about sexual function before and after surgery

Remember the basics

· A thorough history and physical exam are paramount

Ask in a different way

· Any of several validated questionnaires can be a valuable adjunct to the history and physical exam

Individualize treatment

· Many patients respond to nonsurgical treatment, but surgical management is necessary in some cases

Studies of postsurgical sexual function are lacking

Important aspects of sexual function—orgasm, arousal, desire, lubrication, sexual satisfaction, effects on the partner—lack studies. A study of 71 sexually active couples assessed sexual function with questionnaires before and after vaginal native-tissue repair and found that, except for orgasm, all domains improved in female questionnaires. In male partners, interest, sexual drive, and overall satisfaction improved, whereas erection, ejaculation, and orgasm remained unchanged.7

Urinary incontinence during sexual intercourse affects approximately 30% of women with overactive bladder or stress incontinence.8 Several reviews have analyzed data on overall sexual function following urinary incontinence surgery:

- After stress incontinence surgery, the rate of coital incontinence was found to be significantly lower (odds ratio, 0.11).9 In this review, 18 studies, comprising more than 1,500 women, were analyzed, with most participants having undergone insertion of a midurethral mesh sling. Most women (55%) reported no change in overall sexual function, based on validated sexual questionnaire scores; 32% reported improvement; and 13% had deterioration in sexual function.

- As for type of midurethral sling, 2 reviews concluded that there is no difference in sexual function outcomes between retropubic and trans‑obturator sling routes.9,10

Although most studies that have looked at POP and incontinence surgeries show either improvement or no change in sexual function, we stress that sexual function is a secondary outcome in most of those studies, which might not be appropriately powered to detect differences in outcomes. Furthermore, although studies describe dyspareunia and overall sexual function in validated questionnaire scores, most do not evaluate other specific domains of sexual function. It remains unclear, therefore, how POP and incontinence surgeries affect orgasm, desire, arousal, satisfaction, and partner sexual domains; more studies are needed to focus on these areas of female sexual function.

How do we assess these patients?

We do know that sexual function is important to women undergoing gynecologic surgery: In a recent qualitative study of women undergoing pelvic reconstruction, patients rated lack of improvement in sexual function following surgery a “very severe” adverse event.11 Unfortunately, however, sexual activity and function is not always measured before gynecologic surgery. Although specific reporting guidelines do not exist for routine gynecologic surgery, a terminology report from the International Urogynecologic Association/International Continence Society (IUGA/ICS) recommends that sexual activity and partner status be evaluated prior to and following surgical treatment as essential outcomes.12 In addition, the report recommends that sexual pain be assessed prior to and following surgical procedures.12

Ascertain sexual health. First, asking your patients simple questions about sexual function, pain, and bother before and after surgery opens the door to dialogue that allows them, and their partner, to express concerns to you in a safe environment. It also allows you to better understand the significant impact of your surgical interventions on their sexual health.

Questionnaires. Objective measures of vaginal blood flow and engorgement exist, but assessment of sexual activity in the clinical setting is largely limited to self-assessment with questionnaires. Incorporating simple questions, such as “Are you sexually active?,” “Do you have any problems with sexual activity?,” and “Do you have pain with activity?” are likely to be as effective as a more detailed interview and can identify women with sexual concerns.13 Many clinicians are put at a disadvantage, however, because they are faced with the difficult situation of addressing postoperative sexual problems without knowing whether the patient had such reports prior to surgery.

Continue to: Aside from simple screening tools...

Aside from simple screening tools, a number of sexual function questionnaires have been developed. Some are generic, and others are condition-specific:

- Generic questionnaires are typically designed to address the function of a range of women. For example, the Female Sexual Function Index comprises 19 questions. Domains include orgasm, desire, arousal, lubrication, pain and satisfaction.14

- Condition-specific questionnaires of sexual function each have been validated in their target population so that they measure nuances in sexual health relevant to that population. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire—IUGA-Revised includes questions about the domains listed for the generic Index (above) plus questions about the impact of coital incontinence or bulge symptoms on sexual function.12

History-taking. If a woman identifies a problem with sexual function, a thorough history helps elicit whether the condition is lifelong or acquired, situational or general, and, most important, whether or not it is bothersome to her.14,15 It is important not to make assumptions when pursuing this part of the history, and to encourage patients to be candid about how they have sex and with whom.

Physical examination. The patient should undergo a complete physical exam, including 1) a detailed pelvic exam assessing the vulva, vagina, and pelvic-floor musculature, and 2) estrogenization of the tissue.

Partner concerns. For women who have a partner, addressing the concerns of that partner following gynecologic surgery can be useful to the couple: The partner might be concerned about inflicting pain or doing damage during sex after gynecologic surgery.

CASE Informative discussion

While ascertaining her sexual symptoms, your patient reveals to you that she has attempted sexual intercourse on 3 occasions; each time, penetration was too painful to continue. She tells you she did not have this problem before surgery.

The patient says that she has tried water-based lubricants and is using vaginal estrogen 3 times per week, but “nothing helps.” She reports that she is arousable and has been able to achieve orgasm with clitoral stimulation, but would like to have vaginal intercourse. Her husband does have erectile dysfunction, which, she tells you, can make penetration difficult.

On physical examination, you detect mild atrophy. Vaginal length is 9 cm; no narrowing or scarring of the vaginal introitus or canal is seen. No mesh is visible or palpable. The paths of the midurethral sling arms are nontender. However, levator muscles are tender and tense bilaterally.

Given these findings on examination, what steps can you take to relieve your patient’s pain?

What can we offer these patients?

Treating sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery must, as emphasized earlier, be guided by a careful history and physical exam. Doing so is critical to determining the underlying cause. Whenever feasible, offer the least invasive treatment.

The IUGA/ICS terminology report describes several symptoms of postoperative sexual dysfunction12:

- de novo sexual dysfunction

- de novo dyspareunia

- shortened vagina

- tight vagina (introital or vaginal narrowing, or both)

- scarred vagina (including mesh-related problems)

- hispareunia (pain experienced by a male partner after intercourse).

Of course, any one or combination of these symptoms can be present in a given patient. Furthermore, de novo sexual dysfunction, de novo dyspareunia, and hispareunia can have various underlying causes—again, underscoring the importance of the history and exam in determining treatment.

Continue to: Nonsurgical treatment...

Nonsurgical treatment

Nonhormonal vaginal lubricants and moisturizers; vaginal estrogen therapy. Although, in older women, vaginal atrophy is often not a new diagnosis postsurgically, the condition might have been untreated preoperatively and might therefore come into play in sexual dysfunction postoperatively. If a patient reports vaginal dryness or pain upon penetration, assess for vaginal atrophy and, if present, treat accordingly.

Vaginal dilation and physical therapy. A shortened, tight, or scarred vagina might be amenable to therapy with vaginal dilators and physical therapy, but might ultimately require surgery.

Pelvic-floor myalgia or spasm can develop after surgery or, as with atrophy, might have existed preoperatively but was left untreated. Pelvic-floor myalgia should be suspected if the patient describes difficult penetration or a feeling of tightness, even though scarring or constriction of the vagina is not seen on examination. Physical therapy with a specialist in pelvic floor treatment is a first-line treatment for pelvic-floor myalgia,16 and is likely to be a helpful adjunct in many situations, including mesh-related sexual problems.17

Oral or vaginal medications to relax pelvic-floor muscle spasm are an option, although efficacy data are limited. If pain is of longstanding duration and is thought to have a neuropathic component, successful use of tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics, and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors has been reported.18

Surgery

Data are sparse regarding surgical treatment of female sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery. Again, it is clear, however, that the key is carefully assessing each patient and then individualizing treatment. Patients can have any type of dysfunction that a patient who hasn’t had surgery can—but is also at risk of conditions directly related to surgery.

In any patient who has had mesh placed as part of surgery, thorough examination is necessary to determine whether or not the implant is involved in sexual dysfunction. If the dysfunction is an apparent result of surgery performed by another surgeon, make every effort to review the operative report to determine which material was implanted and how it was placed.

Trigger-point injection can be attempted in a patient who has site-specific tenderness that is not clearly associated with tissue obstruction of the vagina or mesh erosion.12,19 Even in areas of apparent banding or scarring related to mesh, trigger-point injection can be attempted to alleviate pain. How often trigger-point injections should be performed is understudied.

If, on examination, tenderness that replicates the dyspareunia is elicited when palpating the levator or obturator internus muscle, pelvic-floor muscle trigger-point injection can be offered (although physical therapy is first-line treatment). Trigger-point injection also can be a useful adjunct in women who have another identified cause of pain but also have developed pelvic-floor muscle spasm.

Not addressing concomitant pelvic-floor myalgia could prevent successful treatment of pain. Inclusion of a pudendal block also might help to alleviate pain.

Continue to: Surgical resection...

Surgical resection. If a skin bridge is clearly observed at the introitus, or if the introitus has been overly narrowed by perineorrhaphy but the remainder of the vagina has adequate length and caliber, surgical resection of the skin bridge might relieve symptoms of difficult penetration. In the case of obstructive perineorrhaphy, an attempt at reversal can be made by incising the perineum vertically but then reapproximating the edges transversely—sometimes referred to as reverse perineorrhaphy.

If scar tissue found elsewhere in the vagina might obstruct penetration, this condition might also be amenable to resection. When scarring is annular, relaxing incisions can be made bilaterally to relieve tension on that tissue; alternatively, it might be necessary to perform a Z-plasty. Nearly always, severe scarring is accompanied by levator myalgia, and a combined approach of surgery and physical therapy is necessary.

Neovagina. It is possible to find vaginal stenosis or shortening, to a varying degree, after surgical prolapse repair, with or without mesh or graft. As discussed, vaginal dilation should be offered but, if this is ineffective, the patient might be a candidate for surgical creation of a neovagina. Numerous techniques have been described for patients with congenital vaginal agenesis, with a few reports of similar techniques used to treat iatrogenic vaginal stenosis or obliteration.

The general principle of all neovagina procedures is to create a space between bladder and rectum of adequate caliber and length for desired sexual function. Reported techniques include a thigh or buttock skin graft, use of bowel or peritoneum, and, recently, a buccal mucosa graft.20,21

Resection or excision of mesh. In patients who develop sexual dysfunction after mesh placement, the problem can be caused by exposure of the mesh in the vagina or erosion into another organ, but can also arise in the absence of exposure or erosion. Patients might have tenderness to palpation at points where the mesh is palpable through the mucosa but not exposed.

Again, complete investigation is necessary to look for mesh involvement in the vagina and, depending on the type of implant, other adjacent organs. Assessing partner symptoms, such as pain and scratches, also can be telling.

If there is palpable tenderness on vaginal examination of the mesh, resection of the vaginal portion might be an option.17 Complete excision of mesh implants can be morbid, however, and might not provide a better outcome than partial excision. The risk of morbidity from complete mesh excision must be weighed against the likelihood that partial excision will not resolve pain and that the patient will require further excision subsequently.17,22 Excising fragmented mesh can be difficult; making every attempt to understand the contribution of mesh to sexual dysfunction is therefore critical to determining how, and how much of, the mesh comes out at the first attempt.

Last, for any woman who opts for surgical intervention to treat pain, you should engage in a discussion to emphasize the multidimensional nature of sexual function and the fact that any surgical intervention might not completely resolve her dysfunction.

Continue to: CASE Discussing options...

CASE Discussing options, choosing an intervention

You discuss the examination findings (no shortening or narrowing of the vagina) with the patient. She is relieved but puzzled as to why she cannot have intercourse. You discuss the tension and t

At 3-month follow-up, she reports great improvement. She is able to have intercourse, although she says she still has discomfort sometimes. She continues to work with the pelvic floor physical therapist and feels optimistic. You plan to see her in 6 months but counsel her to call if symptoms are not improving or are worsening.

It is difficult to counsel patients about sexual function after pelvic reconstructive surgery because data that could guide identification of problems (and how to treat them) are incomplete. Assessingsexual function preoperatively and having an open conversation about risks and benefits of surgery, with specific mention of its impact on sexual health, are critical (see “Key touchpoints in managing sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery”).

It is also crucial to assess sexual function postoperatively as a matter of routine. Validated questionnaires can be a useful adjunct to a thorough history and physical exam, and can help guide your discussions.

Treatment of postop sexual dysfunction must, first, account for the complex nature of sexual function and, second, be individualized, starting with the least invasive options, when feasible.

Sexual dysfunction is challenging for patients and clinicians. Just as sexual function is multidimensional—with physical and psychosocial elements—sexual dysfunction can likewise have multiple contributing factors, and is often divided into dysfunction of desire, arousal, orgasm, and sex-related pain. Addressing each of these dimensions of sexual dysfunction in relationship to pelvic reconstructive surgery is beyond the scope of this article. Here, we focus on aspects of sexual dysfunction most likely to be reported by patients after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) or urinary incontinence, or for both. We discuss what is known about why sexual dysfunction develops after these procedures; how to assess symptoms when sexual dysfunction occurs; and how best to treat these difficult problems.

CASE Postoperative sexual concerns

Your 62-year-old patient presents 2 weeks after vaginal hysterectomy, uterosacral vault suspension, anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, and retropubic midurethral polypropylene sling placement. She reports feeling tired but otherwise doing well.

The patient returns 8 weeks postoperatively, having just resumed her customary exercise routine, and reports that she is feeling well. Upon questioning, she says that she has not yet attempted to have sexual intercourse with her 70-year-old husband.

The patient returns 6 months later and reports that, although she is doing well overall, she is unable to have sexual intercourse.

How can you help this patient? What next steps in evaluation are indicated? Then, with an understanding of her problem in hand, what treatment options can you offer to her?

Surgery for pelvic-floor disorders and sexual function

The impact of surgery on sexual function is important to discuss with patients preoperatively and postoperatively. Because patients with POP and urinary incontinence have a higher rate of sexual dysfunction at baseline, it is important to know how surgery to correct these conditions can affect sexual function.1 Regrettably, many studies of surgical procedures for POP and urinary incontinence either do not include sexual function outcomes or are not powered to detect differences in these outcomes.

Native-tissue repair. A 2015 systematic review looked at studies of women undergoing native-tissue repair for POP without mesh placement of any kind, including a midurethral sling.2 Based on 9 studies that reported validated sexual function questionnaire scores, investigators determined that sexual function scores generally improved following surgery. Collectively, for studies included in this review that specifically reported the rate of dyspareunia before and after surgery, 47% of women reported improvement in dyspareunia; 39% reported no change; 18% reported deterioration in dyspareunia; and only 4% had de novo dyspareunia.

Colporrhaphy. Posterior colporrhaphy, commonly performed to correct posterior vaginal prolapse, can narrow vaginal caliber and the introitus, potentially causing dyspareunia. Early description of posterior colporrhaphy technique included plication of the levator ani muscles, which was associated with significant risk of dyspareunia postoperatively.3 However, posterior colporrhaphy that involves standard plication of the rectovaginal muscularis or site-specific repair has been reported to have a dyspareunia rate from 7% to 20%.4,5 It is generally recommended, therefore, that levator muscle plication during colporrhaphy be avoided in sexually active women.

Continue to: Vaginal mesh...

Vaginal mesh. Mesh has been used in various surgical procedures to correct pelvic floor disorders. Numerous randomized trials have comparatively evaluated the use of transvaginal polypropylene mesh and native tissue for POP repair, and many of these studies have assessed postoperative sexual function. In a 2013 systematic review on sexual function after POP repair, the authors found no significant difference in postoperative sexual function scores or the dyspareunia rate after vaginal mesh repair (14%) and after native-tissue repair (12%).6

Ask; then ask again

· Talk about sexual function before and after surgery

Remember the basics

· A thorough history and physical exam are paramount

Ask in a different way

· Any of several validated questionnaires can be a valuable adjunct to the history and physical exam

Individualize treatment

· Many patients respond to nonsurgical treatment, but surgical management is necessary in some cases

Studies of postsurgical sexual function are lacking

Important aspects of sexual function—orgasm, arousal, desire, lubrication, sexual satisfaction, effects on the partner—lack studies. A study of 71 sexually active couples assessed sexual function with questionnaires before and after vaginal native-tissue repair and found that, except for orgasm, all domains improved in female questionnaires. In male partners, interest, sexual drive, and overall satisfaction improved, whereas erection, ejaculation, and orgasm remained unchanged.7

Urinary incontinence during sexual intercourse affects approximately 30% of women with overactive bladder or stress incontinence.8 Several reviews have analyzed data on overall sexual function following urinary incontinence surgery:

- After stress incontinence surgery, the rate of coital incontinence was found to be significantly lower (odds ratio, 0.11).9 In this review, 18 studies, comprising more than 1,500 women, were analyzed, with most participants having undergone insertion of a midurethral mesh sling. Most women (55%) reported no change in overall sexual function, based on validated sexual questionnaire scores; 32% reported improvement; and 13% had deterioration in sexual function.

- As for type of midurethral sling, 2 reviews concluded that there is no difference in sexual function outcomes between retropubic and trans‑obturator sling routes.9,10

Although most studies that have looked at POP and incontinence surgeries show either improvement or no change in sexual function, we stress that sexual function is a secondary outcome in most of those studies, which might not be appropriately powered to detect differences in outcomes. Furthermore, although studies describe dyspareunia and overall sexual function in validated questionnaire scores, most do not evaluate other specific domains of sexual function. It remains unclear, therefore, how POP and incontinence surgeries affect orgasm, desire, arousal, satisfaction, and partner sexual domains; more studies are needed to focus on these areas of female sexual function.

How do we assess these patients?

We do know that sexual function is important to women undergoing gynecologic surgery: In a recent qualitative study of women undergoing pelvic reconstruction, patients rated lack of improvement in sexual function following surgery a “very severe” adverse event.11 Unfortunately, however, sexual activity and function is not always measured before gynecologic surgery. Although specific reporting guidelines do not exist for routine gynecologic surgery, a terminology report from the International Urogynecologic Association/International Continence Society (IUGA/ICS) recommends that sexual activity and partner status be evaluated prior to and following surgical treatment as essential outcomes.12 In addition, the report recommends that sexual pain be assessed prior to and following surgical procedures.12

Ascertain sexual health. First, asking your patients simple questions about sexual function, pain, and bother before and after surgery opens the door to dialogue that allows them, and their partner, to express concerns to you in a safe environment. It also allows you to better understand the significant impact of your surgical interventions on their sexual health.

Questionnaires. Objective measures of vaginal blood flow and engorgement exist, but assessment of sexual activity in the clinical setting is largely limited to self-assessment with questionnaires. Incorporating simple questions, such as “Are you sexually active?,” “Do you have any problems with sexual activity?,” and “Do you have pain with activity?” are likely to be as effective as a more detailed interview and can identify women with sexual concerns.13 Many clinicians are put at a disadvantage, however, because they are faced with the difficult situation of addressing postoperative sexual problems without knowing whether the patient had such reports prior to surgery.

Continue to: Aside from simple screening tools...

Aside from simple screening tools, a number of sexual function questionnaires have been developed. Some are generic, and others are condition-specific:

- Generic questionnaires are typically designed to address the function of a range of women. For example, the Female Sexual Function Index comprises 19 questions. Domains include orgasm, desire, arousal, lubrication, pain and satisfaction.14

- Condition-specific questionnaires of sexual function each have been validated in their target population so that they measure nuances in sexual health relevant to that population. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire—IUGA-Revised includes questions about the domains listed for the generic Index (above) plus questions about the impact of coital incontinence or bulge symptoms on sexual function.12

History-taking. If a woman identifies a problem with sexual function, a thorough history helps elicit whether the condition is lifelong or acquired, situational or general, and, most important, whether or not it is bothersome to her.14,15 It is important not to make assumptions when pursuing this part of the history, and to encourage patients to be candid about how they have sex and with whom.

Physical examination. The patient should undergo a complete physical exam, including 1) a detailed pelvic exam assessing the vulva, vagina, and pelvic-floor musculature, and 2) estrogenization of the tissue.

Partner concerns. For women who have a partner, addressing the concerns of that partner following gynecologic surgery can be useful to the couple: The partner might be concerned about inflicting pain or doing damage during sex after gynecologic surgery.

CASE Informative discussion

While ascertaining her sexual symptoms, your patient reveals to you that she has attempted sexual intercourse on 3 occasions; each time, penetration was too painful to continue. She tells you she did not have this problem before surgery.

The patient says that she has tried water-based lubricants and is using vaginal estrogen 3 times per week, but “nothing helps.” She reports that she is arousable and has been able to achieve orgasm with clitoral stimulation, but would like to have vaginal intercourse. Her husband does have erectile dysfunction, which, she tells you, can make penetration difficult.

On physical examination, you detect mild atrophy. Vaginal length is 9 cm; no narrowing or scarring of the vaginal introitus or canal is seen. No mesh is visible or palpable. The paths of the midurethral sling arms are nontender. However, levator muscles are tender and tense bilaterally.

Given these findings on examination, what steps can you take to relieve your patient’s pain?

What can we offer these patients?

Treating sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery must, as emphasized earlier, be guided by a careful history and physical exam. Doing so is critical to determining the underlying cause. Whenever feasible, offer the least invasive treatment.

The IUGA/ICS terminology report describes several symptoms of postoperative sexual dysfunction12:

- de novo sexual dysfunction

- de novo dyspareunia

- shortened vagina

- tight vagina (introital or vaginal narrowing, or both)

- scarred vagina (including mesh-related problems)

- hispareunia (pain experienced by a male partner after intercourse).

Of course, any one or combination of these symptoms can be present in a given patient. Furthermore, de novo sexual dysfunction, de novo dyspareunia, and hispareunia can have various underlying causes—again, underscoring the importance of the history and exam in determining treatment.

Continue to: Nonsurgical treatment...

Nonsurgical treatment

Nonhormonal vaginal lubricants and moisturizers; vaginal estrogen therapy. Although, in older women, vaginal atrophy is often not a new diagnosis postsurgically, the condition might have been untreated preoperatively and might therefore come into play in sexual dysfunction postoperatively. If a patient reports vaginal dryness or pain upon penetration, assess for vaginal atrophy and, if present, treat accordingly.

Vaginal dilation and physical therapy. A shortened, tight, or scarred vagina might be amenable to therapy with vaginal dilators and physical therapy, but might ultimately require surgery.

Pelvic-floor myalgia or spasm can develop after surgery or, as with atrophy, might have existed preoperatively but was left untreated. Pelvic-floor myalgia should be suspected if the patient describes difficult penetration or a feeling of tightness, even though scarring or constriction of the vagina is not seen on examination. Physical therapy with a specialist in pelvic floor treatment is a first-line treatment for pelvic-floor myalgia,16 and is likely to be a helpful adjunct in many situations, including mesh-related sexual problems.17

Oral or vaginal medications to relax pelvic-floor muscle spasm are an option, although efficacy data are limited. If pain is of longstanding duration and is thought to have a neuropathic component, successful use of tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics, and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors has been reported.18

Surgery

Data are sparse regarding surgical treatment of female sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery. Again, it is clear, however, that the key is carefully assessing each patient and then individualizing treatment. Patients can have any type of dysfunction that a patient who hasn’t had surgery can—but is also at risk of conditions directly related to surgery.

In any patient who has had mesh placed as part of surgery, thorough examination is necessary to determine whether or not the implant is involved in sexual dysfunction. If the dysfunction is an apparent result of surgery performed by another surgeon, make every effort to review the operative report to determine which material was implanted and how it was placed.

Trigger-point injection can be attempted in a patient who has site-specific tenderness that is not clearly associated with tissue obstruction of the vagina or mesh erosion.12,19 Even in areas of apparent banding or scarring related to mesh, trigger-point injection can be attempted to alleviate pain. How often trigger-point injections should be performed is understudied.

If, on examination, tenderness that replicates the dyspareunia is elicited when palpating the levator or obturator internus muscle, pelvic-floor muscle trigger-point injection can be offered (although physical therapy is first-line treatment). Trigger-point injection also can be a useful adjunct in women who have another identified cause of pain but also have developed pelvic-floor muscle spasm.

Not addressing concomitant pelvic-floor myalgia could prevent successful treatment of pain. Inclusion of a pudendal block also might help to alleviate pain.

Continue to: Surgical resection...

Surgical resection. If a skin bridge is clearly observed at the introitus, or if the introitus has been overly narrowed by perineorrhaphy but the remainder of the vagina has adequate length and caliber, surgical resection of the skin bridge might relieve symptoms of difficult penetration. In the case of obstructive perineorrhaphy, an attempt at reversal can be made by incising the perineum vertically but then reapproximating the edges transversely—sometimes referred to as reverse perineorrhaphy.

If scar tissue found elsewhere in the vagina might obstruct penetration, this condition might also be amenable to resection. When scarring is annular, relaxing incisions can be made bilaterally to relieve tension on that tissue; alternatively, it might be necessary to perform a Z-plasty. Nearly always, severe scarring is accompanied by levator myalgia, and a combined approach of surgery and physical therapy is necessary.

Neovagina. It is possible to find vaginal stenosis or shortening, to a varying degree, after surgical prolapse repair, with or without mesh or graft. As discussed, vaginal dilation should be offered but, if this is ineffective, the patient might be a candidate for surgical creation of a neovagina. Numerous techniques have been described for patients with congenital vaginal agenesis, with a few reports of similar techniques used to treat iatrogenic vaginal stenosis or obliteration.

The general principle of all neovagina procedures is to create a space between bladder and rectum of adequate caliber and length for desired sexual function. Reported techniques include a thigh or buttock skin graft, use of bowel or peritoneum, and, recently, a buccal mucosa graft.20,21

Resection or excision of mesh. In patients who develop sexual dysfunction after mesh placement, the problem can be caused by exposure of the mesh in the vagina or erosion into another organ, but can also arise in the absence of exposure or erosion. Patients might have tenderness to palpation at points where the mesh is palpable through the mucosa but not exposed.

Again, complete investigation is necessary to look for mesh involvement in the vagina and, depending on the type of implant, other adjacent organs. Assessing partner symptoms, such as pain and scratches, also can be telling.

If there is palpable tenderness on vaginal examination of the mesh, resection of the vaginal portion might be an option.17 Complete excision of mesh implants can be morbid, however, and might not provide a better outcome than partial excision. The risk of morbidity from complete mesh excision must be weighed against the likelihood that partial excision will not resolve pain and that the patient will require further excision subsequently.17,22 Excising fragmented mesh can be difficult; making every attempt to understand the contribution of mesh to sexual dysfunction is therefore critical to determining how, and how much of, the mesh comes out at the first attempt.

Last, for any woman who opts for surgical intervention to treat pain, you should engage in a discussion to emphasize the multidimensional nature of sexual function and the fact that any surgical intervention might not completely resolve her dysfunction.

Continue to: CASE Discussing options...

CASE Discussing options, choosing an intervention

You discuss the examination findings (no shortening or narrowing of the vagina) with the patient. She is relieved but puzzled as to why she cannot have intercourse. You discuss the tension and t

At 3-month follow-up, she reports great improvement. She is able to have intercourse, although she says she still has discomfort sometimes. She continues to work with the pelvic floor physical therapist and feels optimistic. You plan to see her in 6 months but counsel her to call if symptoms are not improving or are worsening.

It is difficult to counsel patients about sexual function after pelvic reconstructive surgery because data that could guide identification of problems (and how to treat them) are incomplete. Assessingsexual function preoperatively and having an open conversation about risks and benefits of surgery, with specific mention of its impact on sexual health, are critical (see “Key touchpoints in managing sexual dysfunction after pelvic reconstructive surgery”).

It is also crucial to assess sexual function postoperatively as a matter of routine. Validated questionnaires can be a useful adjunct to a thorough history and physical exam, and can help guide your discussions.

Treatment of postop sexual dysfunction must, first, account for the complex nature of sexual function and, second, be individualized, starting with the least invasive options, when feasible.

- Rogers RG. Sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:S199-S201.

- Jha S, Gray T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:321-327.

- Thompson JC, Rogers RG. Surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse and its impact on sexual function. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4:213-220.

- Sung VW, Rardin CR, Raker CA, et al. Porcine subintestinal submucosal graft augmentation for rectocele repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:125-133.

- Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Muir TW, et al. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1762-1771.

- Dietz V, Maher C. Pelvic organ prolapse and sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1853-1857.

- Kuhn A, Brunnmayr G, Stadlmayr W, et al. Male and female sexual function after surgical repair of female organ prolapse. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1324-1334.

- Gray T, Li W, Campbell P, et al. Evaluation of coital incontinence by electronic questionnaire: prevalence, associations and outcomes in women attending a urogynaecology clinic. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:969-978.

- Jha S, Ammenbal M, Metwally M. Impact of incontinence surgery on sexual function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9:34-43.

- Schimpf MO, Rahn DD, Wheeler TL, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:71.e1-e71.e27.

- Dunivan GC, Sussman AL, Jelovsek JE, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Gaining the patient perspective on pelvic floor disorders’ surgical adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:185.e1-e185.e10.

- Rogers RG, Pauls RN, Thakar R, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the assessment of sexual health of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:647-666.

- Plouffe L Jr. Screening for sexual problems through a simple questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:166-169.

- Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Derogatis LR, et al. Recommendations for the clinical evaluation of men and women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7:337-348.

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Atalla E, et al. Definition of sexual dysfunctions in women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation of Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2015;13:135-143.

- Berghmans B. Physiotherapy for pelvic pain and female sexual dysfunction: an untapped resource. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:631-638.

- Cundiff GW, Quinlan DJ, van Rensburg JA, et al. Foundation for an evidence-informed algorithm for treating pelvic floor mesh complications: a review. BJOG. 2018;125:1026-1037.

- Steege JF, Siedhoff MT. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:616-629.

- Wehbe SA, Whitmore K, Kellogg-Spadt S. Urogenital complaints and female sexual dysfunction (part 1). J Sex Med. 2010;7:1704-1713.

- Grimsby GM, Bradshaw K, Baker LA. Autologous buccal mucosa graft augmentation for foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:947-950.

- Morley GW, DeLancey JO. Full-thickness skin graft vaginoplasty for treatment of the stenotic or foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:485-489.

- Pickett SD, Barenberg B, Quiroz LH, et al. The significant morbidity of removing pelvic mesh from multiple vaginal compartments. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1418-1422.

- Rogers RG. Sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:S199-S201.

- Jha S, Gray T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:321-327.

- Thompson JC, Rogers RG. Surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse and its impact on sexual function. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4:213-220.

- Sung VW, Rardin CR, Raker CA, et al. Porcine subintestinal submucosal graft augmentation for rectocele repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:125-133.

- Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Muir TW, et al. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1762-1771.

- Dietz V, Maher C. Pelvic organ prolapse and sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1853-1857.

- Kuhn A, Brunnmayr G, Stadlmayr W, et al. Male and female sexual function after surgical repair of female organ prolapse. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1324-1334.

- Gray T, Li W, Campbell P, et al. Evaluation of coital incontinence by electronic questionnaire: prevalence, associations and outcomes in women attending a urogynaecology clinic. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:969-978.

- Jha S, Ammenbal M, Metwally M. Impact of incontinence surgery on sexual function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9:34-43.

- Schimpf MO, Rahn DD, Wheeler TL, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:71.e1-e71.e27.

- Dunivan GC, Sussman AL, Jelovsek JE, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Gaining the patient perspective on pelvic floor disorders’ surgical adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:185.e1-e185.e10.

- Rogers RG, Pauls RN, Thakar R, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the assessment of sexual health of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:647-666.

- Plouffe L Jr. Screening for sexual problems through a simple questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:166-169.

- Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Derogatis LR, et al. Recommendations for the clinical evaluation of men and women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7:337-348.

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Atalla E, et al. Definition of sexual dysfunctions in women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation of Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2015;13:135-143.

- Berghmans B. Physiotherapy for pelvic pain and female sexual dysfunction: an untapped resource. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:631-638.

- Cundiff GW, Quinlan DJ, van Rensburg JA, et al. Foundation for an evidence-informed algorithm for treating pelvic floor mesh complications: a review. BJOG. 2018;125:1026-1037.

- Steege JF, Siedhoff MT. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:616-629.

- Wehbe SA, Whitmore K, Kellogg-Spadt S. Urogenital complaints and female sexual dysfunction (part 1). J Sex Med. 2010;7:1704-1713.

- Grimsby GM, Bradshaw K, Baker LA. Autologous buccal mucosa graft augmentation for foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:947-950.

- Morley GW, DeLancey JO. Full-thickness skin graft vaginoplasty for treatment of the stenotic or foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:485-489.

- Pickett SD, Barenberg B, Quiroz LH, et al. The significant morbidity of removing pelvic mesh from multiple vaginal compartments. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1418-1422.

Highlights from the 2018 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Scientific Meeting

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,