User login

The path to becoming an esophagologist

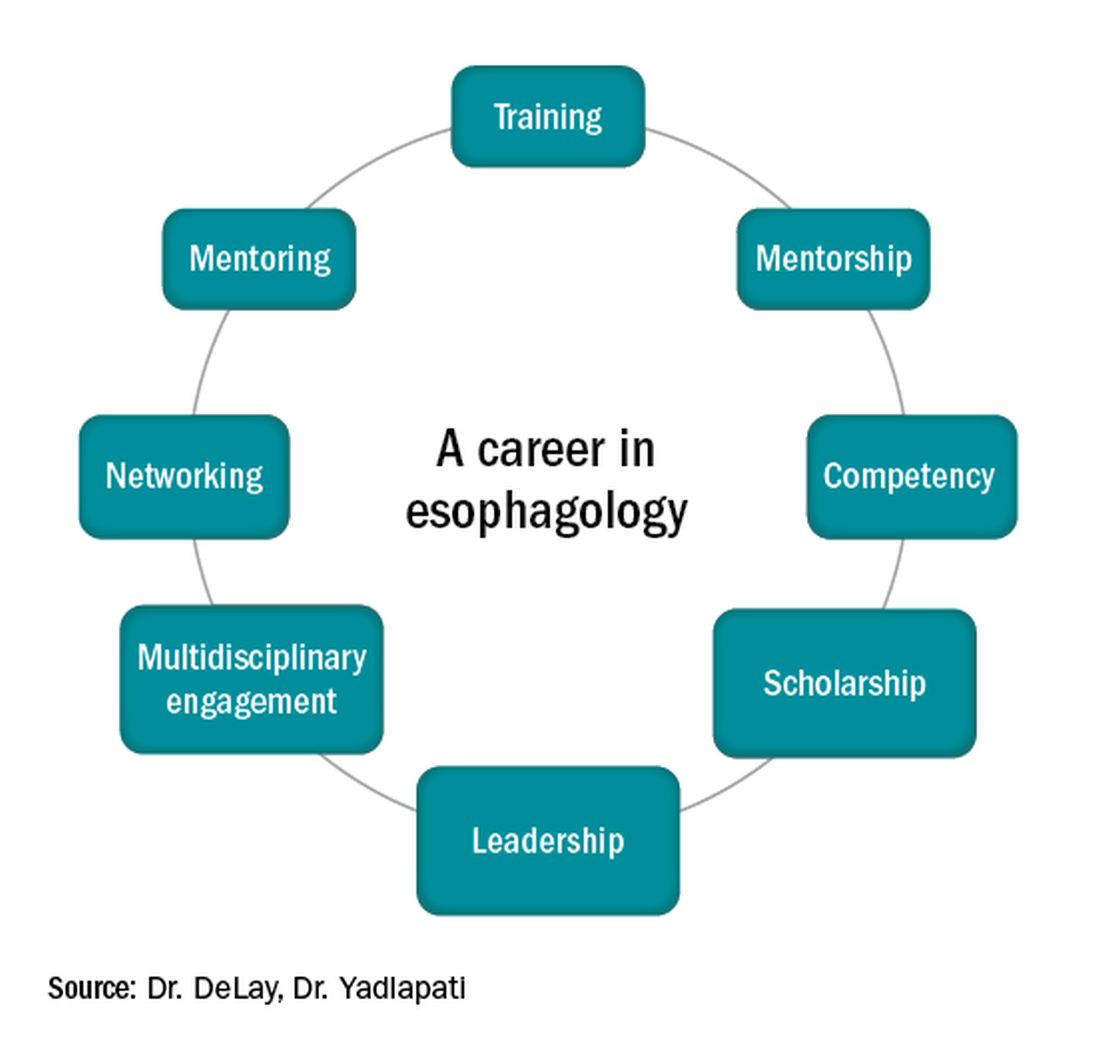

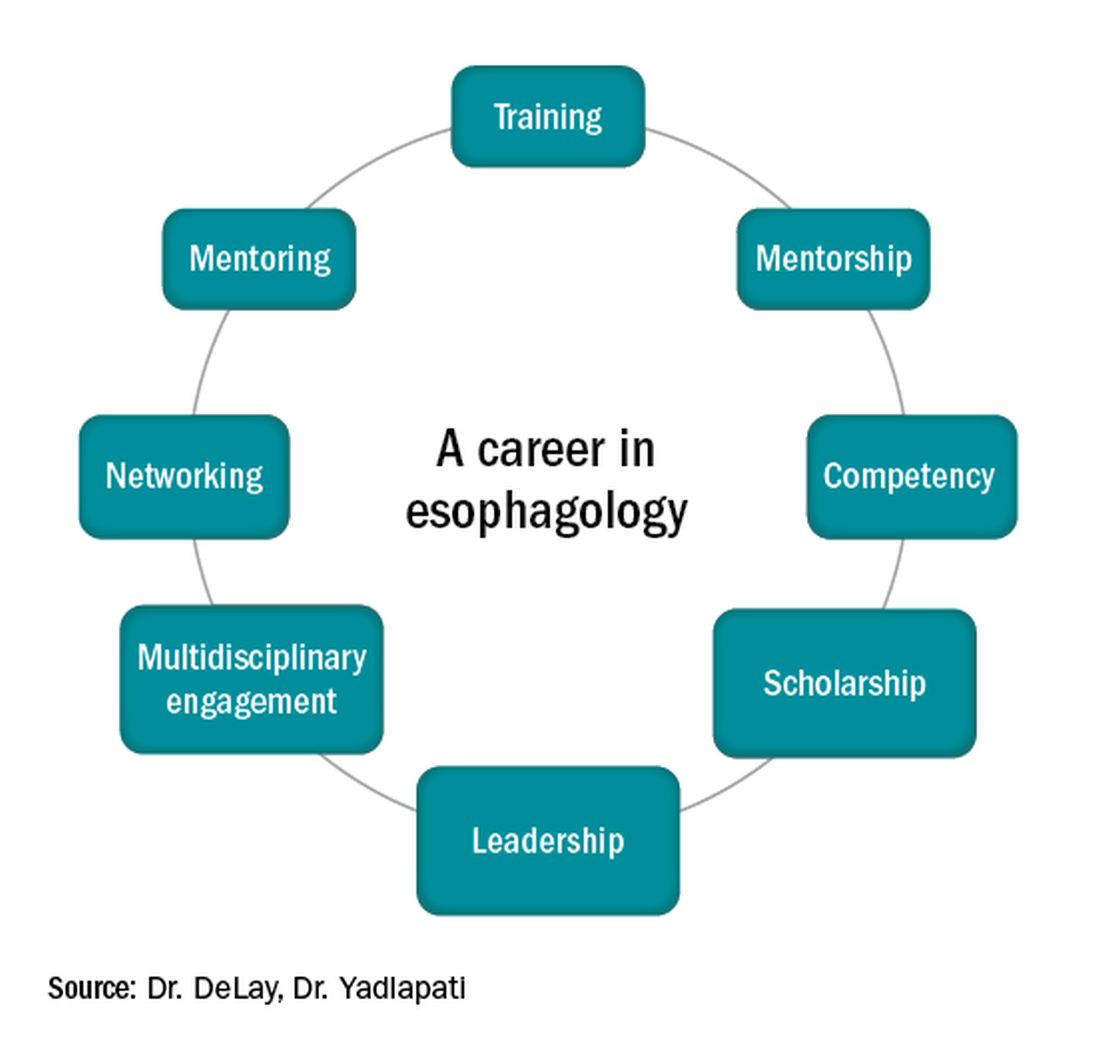

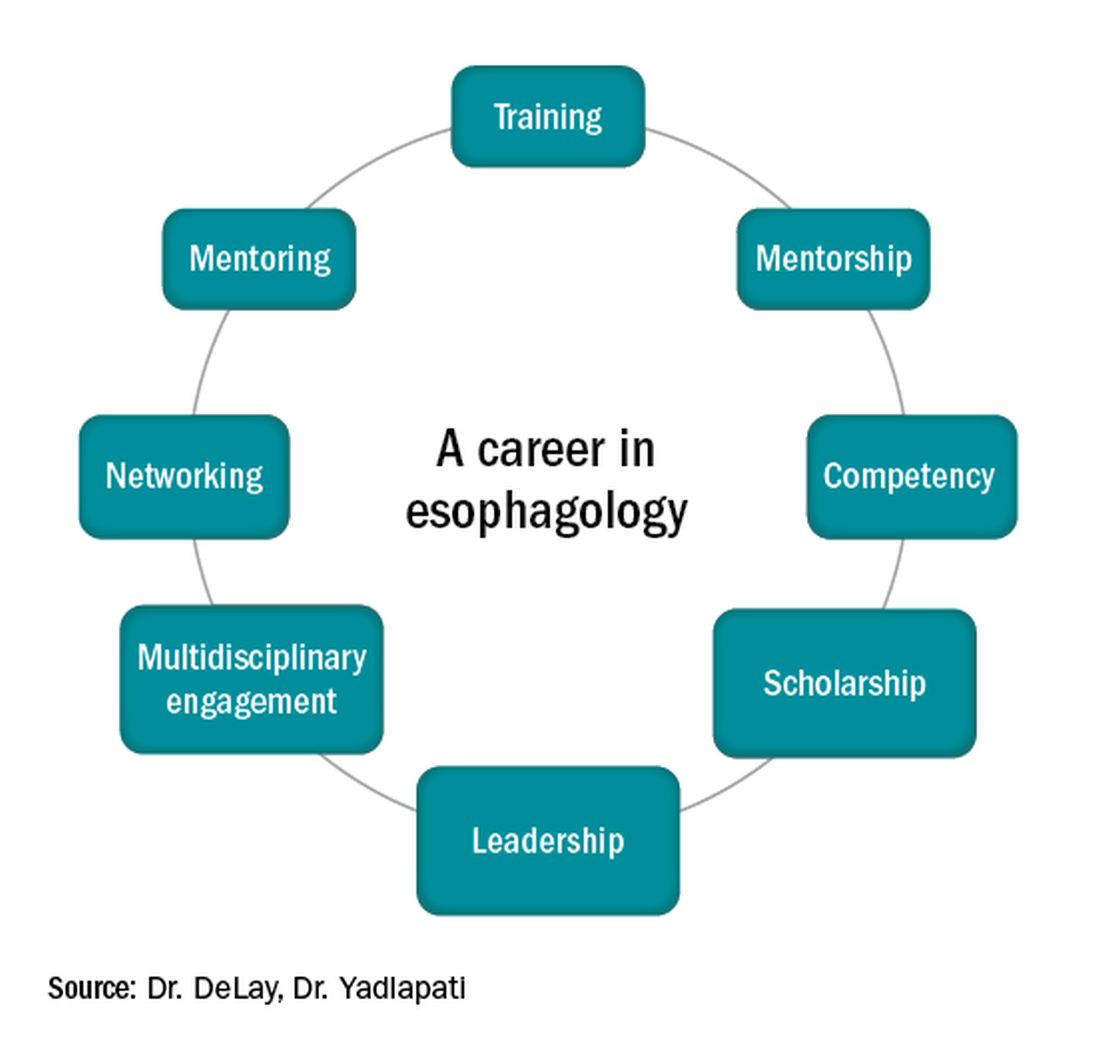

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

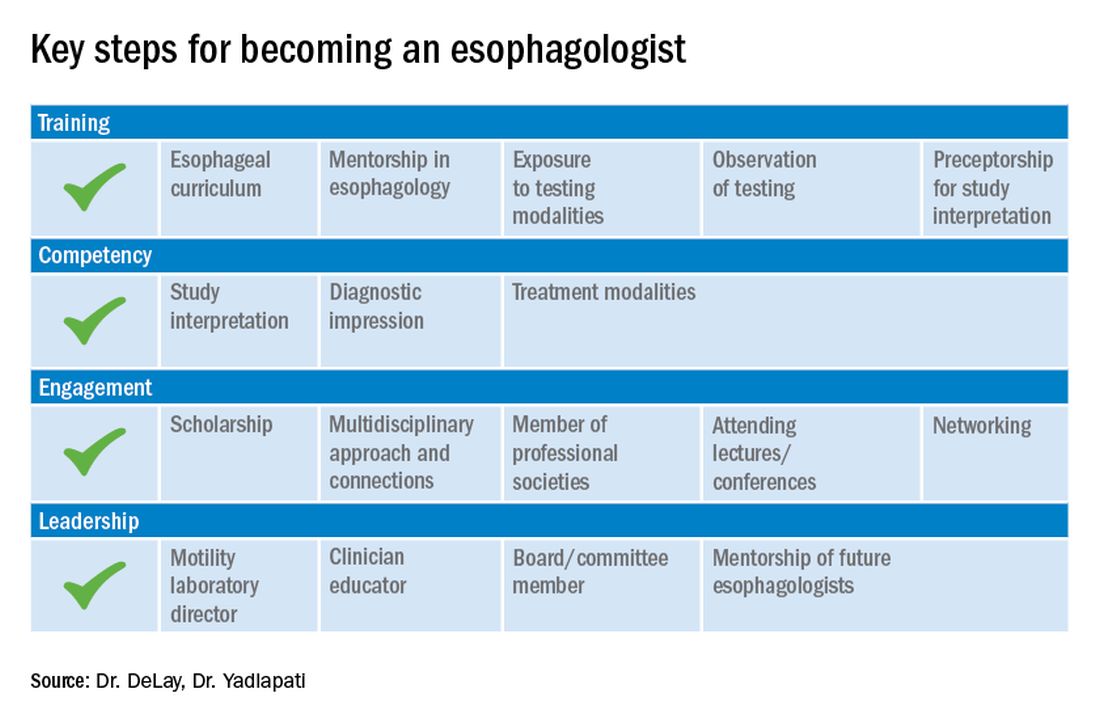

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

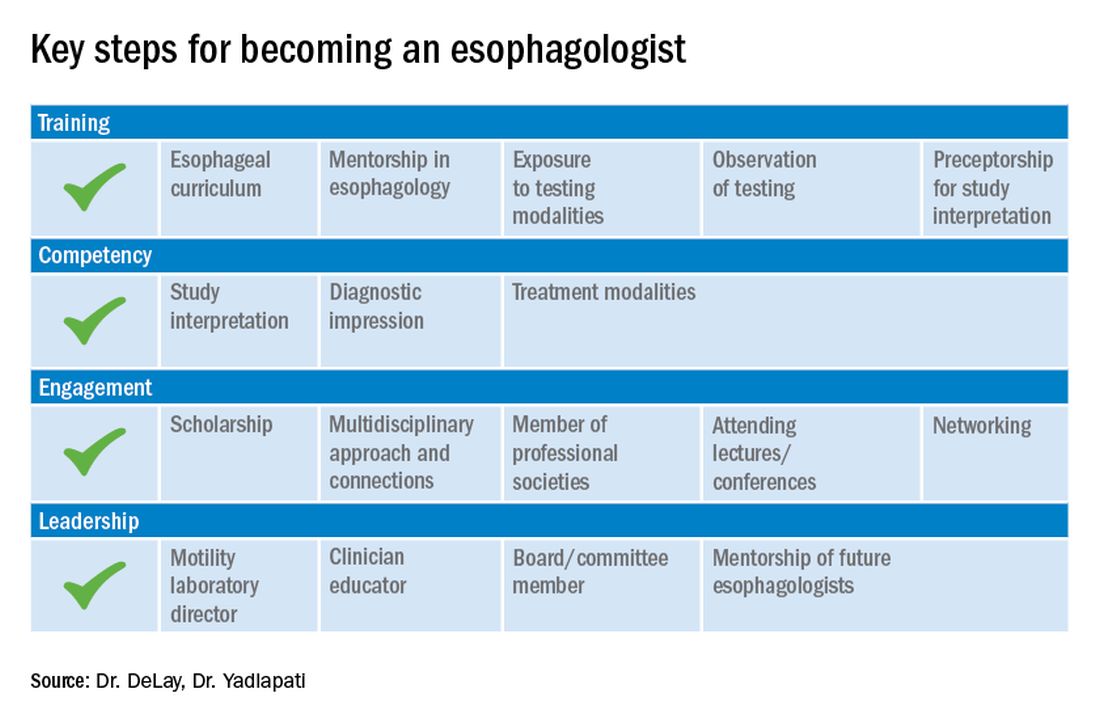

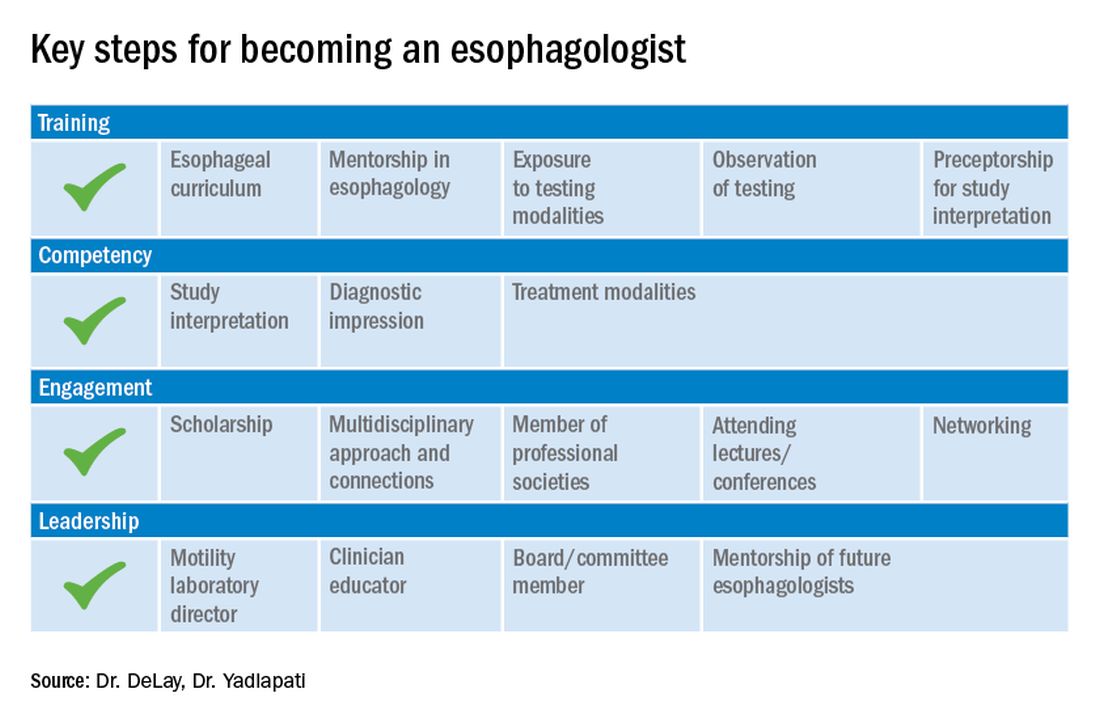

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

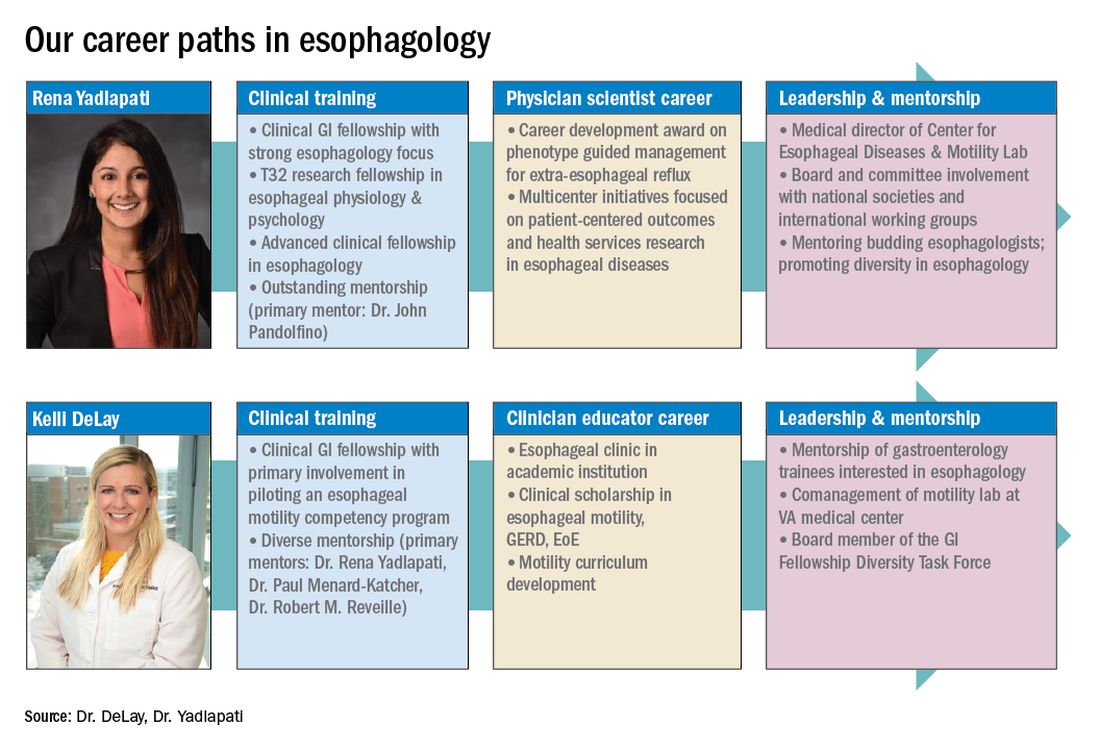

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

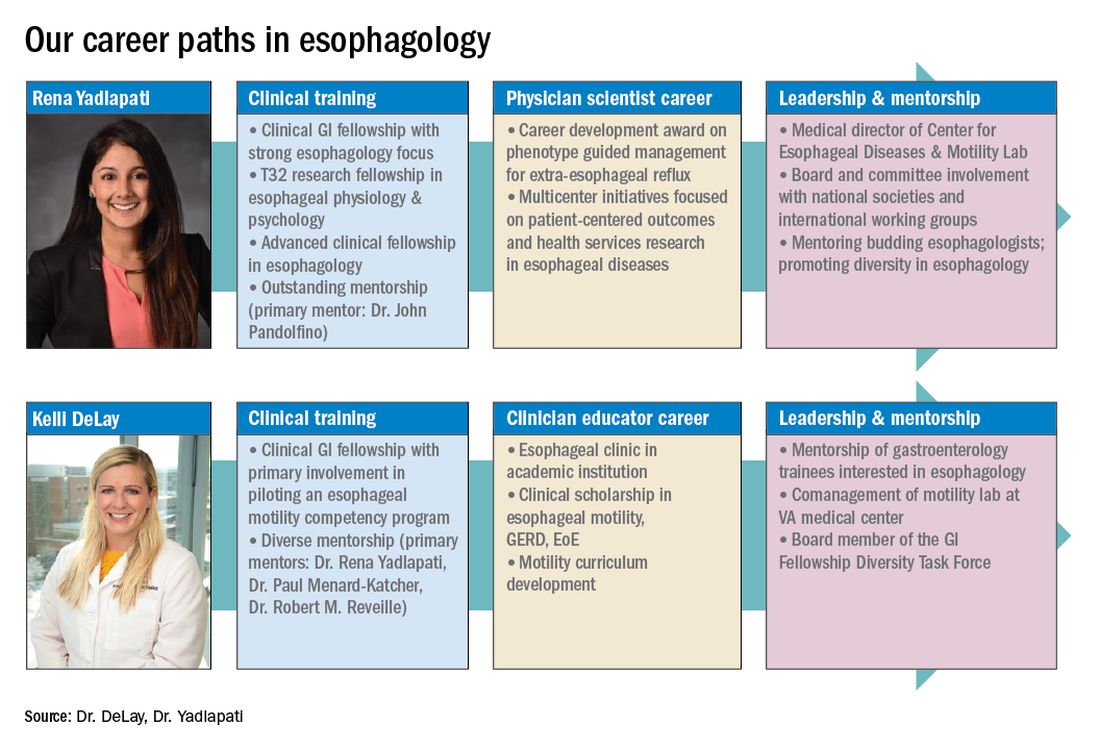

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

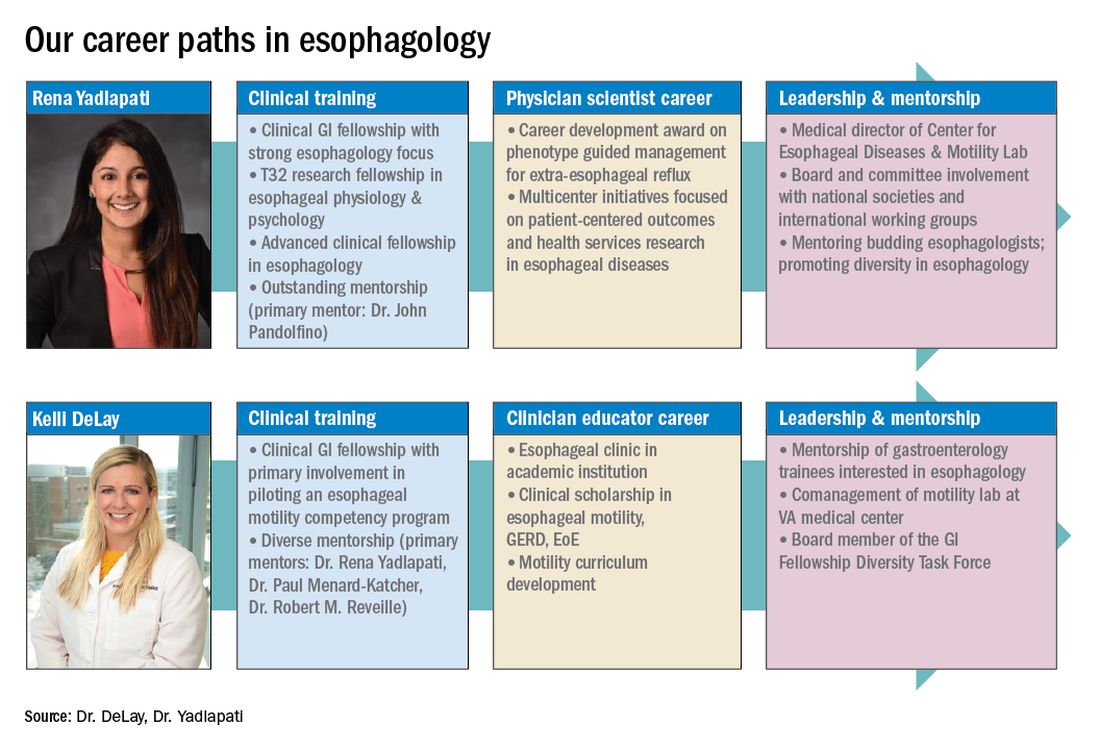

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

@GiJournal: An online platform to discuss the latest gastroenterology and hepatology publications

The last decade has seen an increased focus on the use of social media for medical education. Twitter, with over 330 million active users, is the most popular social media platform for medical education. We describe here our recent initiative to establish a weekly online gastroenterology-focused journal club on Twitter.

How was the idea conceived?

Sultan Mahmood, MD (@SultanMahmoodMD)

I joined #GITwitter at the end of 2019 and started following some of the leading experts in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. It was a pleasant surprise to see how easy it was to engage with them and get expert opinions from across the world in real time. #MondayNightIBD, led by Aline Charabaty, MD, had become a phenomenon in the GI community and changed the perception of medical education in the digital world. There were online journal clubs for different medical subspecialties, including #NephroJC, #HOJournalClub, and #DermJC, but none for gastroenterology. Realizing this opportunity, and with guidance from Dr. Charabaty, we started @GiJournal in December of 2019 with weekly discussions.

@GiJournal started off as an informal discussion in which we would post a summary of the article and invite an expert in the field to comment. However, the interest in the journal club quickly took off as we gained more followers and a worldwide audience joined our journal club discussions on a weekly basis. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and endoscopy suites around the word closed, interest in online medical education grew. @GIJournal provided a platform for trainees and practicing physicians alike to stay up to date with the latest publications from the comfort of their homes. Needless to say, the journal club has evolved since its inception in that we now work with a team of experts and trainees who run the journal club on a rotating basis.

How does @GiJournal work?

Ijlal Akbar Ali, MD (@IjlalAkbar)

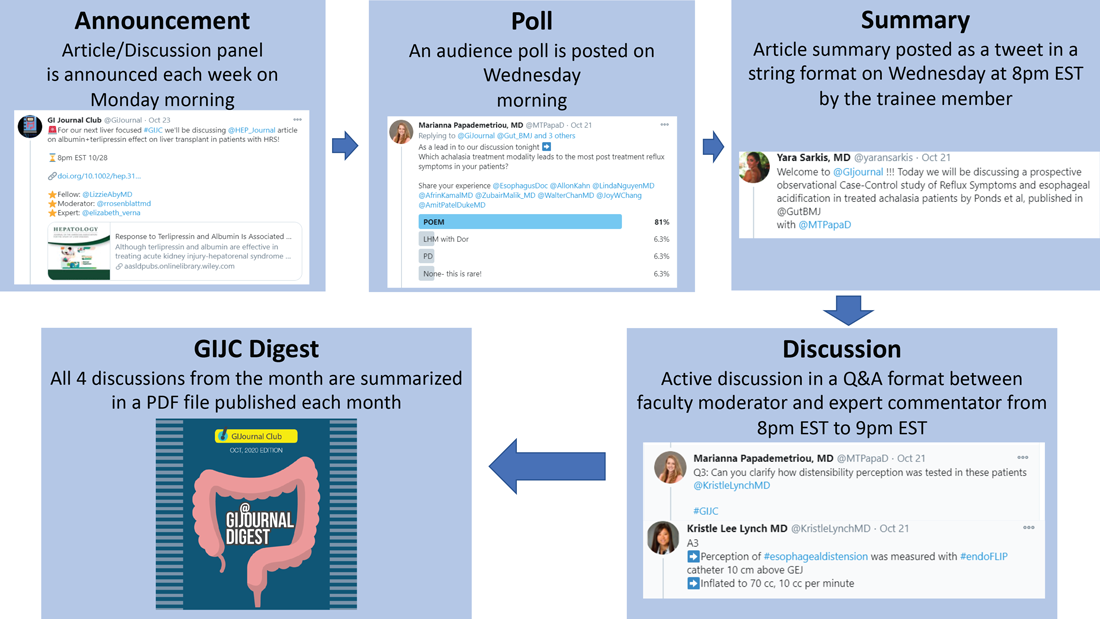

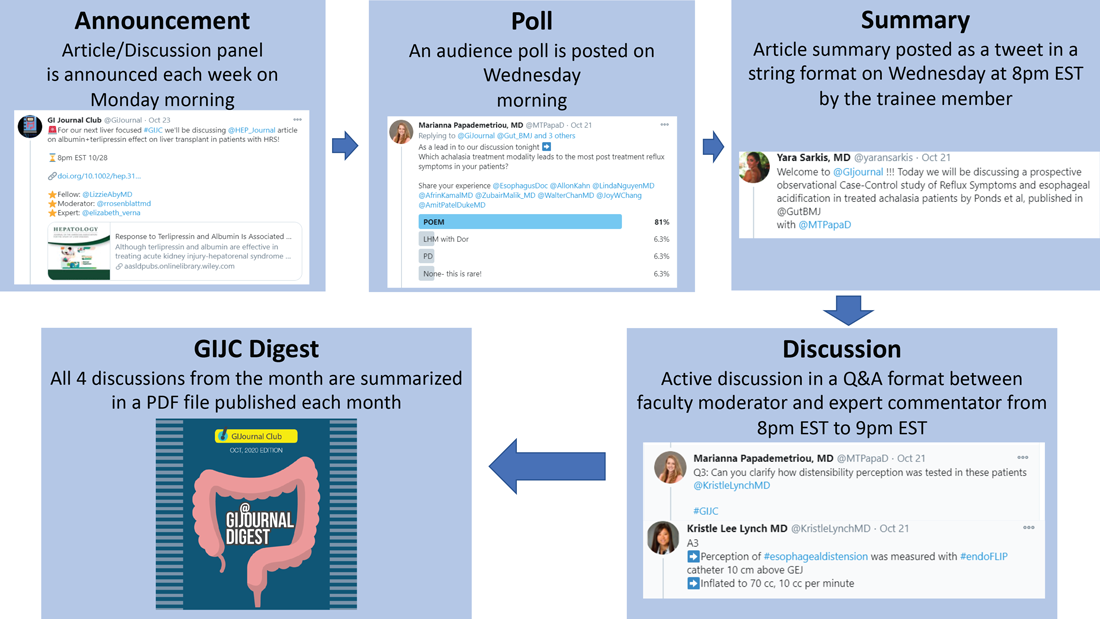

We have a large editorial board with volunteer faculty and trainees, all divided into four special interest groups (general GI/inflammatory bowel disease, interventional endoscopy/bariatric endoscopy, hepatology, and esophageal/motility disorders). Each week, a faculty member and a trainee pick a recently published article from a high-impact GI-focused journal. We also try to invite an expert of international repute (often the authors of the article themselves!) to engage as well. The faculty moderator and invited expert then work with the trainee to plan the session content. We post the topic and article on Monday. At 8 p.m. EST on Wednesday, the trainee posts a series of six to eight tweets summarizing the article. The faculty then asks the invited expert (and audience at large) a series of predetermined questions. Anyone can respond, share their opinion, and direct their own questions toward the moderator and expert who continually check their notifications and respond in real time. This brews into an hour-long discussion which covers not only the methodologic aspects of the article, but clinical practice in general. Discussions often trickle into the next day as people from different time zones participate. Everyone uses #GIJC at the end of their tweets which assists those following the article and facilitates indexing for future review. For those who miss or want to review sessions, we conveniently summarize all articles and corresponding discussions in a monthly publication, @GiJournal Digest, that is posted on Twitter for anyone to download, read and enjoy (Figure 1).

How is this different from any other journal club?

Atoosa Rabiee, MD (@AtoosaRabiee)

@GiJournal is unique in that it provides trainees and practicing gastroenterologists access to interactive discussions with both authors and world-renowned experts in the field. Online journal clubs operate with a flattened hierarchy; as such, they inherently break down access barriers to both the researchers who performed the study and key opinion leaders who commonly participate. There is no boundary as far as institutions or even countries. As a result, our platform has uncovered an unexpected degree of interest in live online discussion, and we have enjoyed collaborating and learning from experts from all over the world. @GiJournal also differs from conventional journal clubs by allowing trainees the opportunity to collaborate and engage with mentors from other institutions. As such, trainees develop relationships with experts in the field outside their home institutions, experts with whom they may not have had contact otherwise.

Although worldwide participation is a key strength of the online @GiJournal platform, it may be challenging for some members to attend the live discussion based on time difference. We account for this in two ways. First, participants are encouraged to continue with comments and questions afterward at their convenience, which allows experts and moderators to continue the conversation, often for several days. Second, to promote inclusivity, we have created a unique, customized publication to summarize and present the key points of conversation for each session. This asynchronous access is a quality not found in more traditional journal club formats. Finally, studies have shown that articles shared on social media tend to have increased citations and higher Altmetric scores.

What are the opportunities for trainees and recent graduates?

Sunil Amin, MD, MPH (@SunilAminMD)

Our surveys have shown that 30%-45% of the @GiJournal discussion participants are trainees. Both gastroenterology fellows and internal medicine residents from around the world are an integral part of each specialty panel for the weekly @GIjournal discussions. Trainees are paired up with a specific faculty mentor and together they choose an article for discussion, create a summary, informal twitter poll, and questions for the discussion. This direct access provides an opportunity for trainees to interact, ask questions, and learn from faculty in an informal atmosphere.

We have heard from multiple trainees who have developed long-term relationships with the experts and faculty mentors they worked with and are now also working on research projects. Additionally, trainees can bring the expertise they have now acquired back to their home institutions to pick articles, add specific teaching points, and enrich their local journal club discussions. Finally, trainees who present on the @GiJournal platform are given unique visibility to the many faculty members and opinion leaders participating in each discussion. This may facilitate future networking opportunities and enhance their CVs for future fellowship or employment applications.

Plans for the future?

Allon Kahn, MD (@AllonKahn)

Despite significant evolution and growth in @GiJournal over the past year, we are still actively working to expand our platform. Modes of online medical education, specifically Twitter-based GI journal club discussions, remain in their infancy. We see this @GiJournal as an opportunity for innovation as we plan for the year ahead. Our top priority for the upcoming year includes obtaining CME approval, which we are currently developing with Integrity CE (an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education–accredited provider of CME for health care professionals). This will give an opportunity for the participants to be awarded CME credit when they participate in our weekly discussions. Other options being explored include starting a podcast and translation of @GiJournal Digest in different languages to reach a wider international audience. Furthermore, with the continued expansion of GI leaders and experts joining and engaging in Twitter, our options for unique and multidisciplinary discussion topics will continue to grow.

How can you join the @GiJournal discussions?

@SultanMahmoodMD

Joining the journal club discussion is easy. Just follow the @GiJournal handle on Twitter and turn on the notifications icon. Although we encourage everyone to “actively” participate in the discussion by asking questions or sharing your personal experience, joining the discussion as an “observer” is also a great way to learn. The discussion starts at 8 p.m. EST every Wednesday. Follow the #GIJC and the @GiJournal handle as questions are posted by the faculty moderator and answered by the experts. Even if you miss the discussion, the @GiJournal Digest is a great way to recap the discussions in an easy-to-read PDF format. The @GiJournal Digest is a monthly publication that archives the four @GiJournal club discussions in the previous month. Follow the link below to access the recent publications: http://ow.ly/uu2550C3RXX

Conclusion

In summary, we believe Twitter-based journal clubs offer an engaging way of virtual learning from the comfort of one’s home and a convenient way to directly interact with the experts. The success of @GiJournal highlights the importance of social media for medical education in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology and we look forward to developing this endeavor further.

Dr. Mahmood is clinical assistant professor of medicine, co–program director of the GI fellowship program, UB division of gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition, State University of New York at Buffalo; Dr. Rabiee is assistant professor of medicine, director of hepatology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Washington; Dr. Amin is assistant professor of medicine, director of endoscopy, The Lennar Foundation Medical Center, division of digestive health and liver disease, department of medicine, University of Miami; Dr. Kahn is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Dr. Akbar Ali is a gastroenterology fellow in the division of digestive diseases and nutrition, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

The last decade has seen an increased focus on the use of social media for medical education. Twitter, with over 330 million active users, is the most popular social media platform for medical education. We describe here our recent initiative to establish a weekly online gastroenterology-focused journal club on Twitter.

How was the idea conceived?

Sultan Mahmood, MD (@SultanMahmoodMD)

I joined #GITwitter at the end of 2019 and started following some of the leading experts in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. It was a pleasant surprise to see how easy it was to engage with them and get expert opinions from across the world in real time. #MondayNightIBD, led by Aline Charabaty, MD, had become a phenomenon in the GI community and changed the perception of medical education in the digital world. There were online journal clubs for different medical subspecialties, including #NephroJC, #HOJournalClub, and #DermJC, but none for gastroenterology. Realizing this opportunity, and with guidance from Dr. Charabaty, we started @GiJournal in December of 2019 with weekly discussions.

@GiJournal started off as an informal discussion in which we would post a summary of the article and invite an expert in the field to comment. However, the interest in the journal club quickly took off as we gained more followers and a worldwide audience joined our journal club discussions on a weekly basis. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and endoscopy suites around the word closed, interest in online medical education grew. @GIJournal provided a platform for trainees and practicing physicians alike to stay up to date with the latest publications from the comfort of their homes. Needless to say, the journal club has evolved since its inception in that we now work with a team of experts and trainees who run the journal club on a rotating basis.

How does @GiJournal work?

Ijlal Akbar Ali, MD (@IjlalAkbar)

We have a large editorial board with volunteer faculty and trainees, all divided into four special interest groups (general GI/inflammatory bowel disease, interventional endoscopy/bariatric endoscopy, hepatology, and esophageal/motility disorders). Each week, a faculty member and a trainee pick a recently published article from a high-impact GI-focused journal. We also try to invite an expert of international repute (often the authors of the article themselves!) to engage as well. The faculty moderator and invited expert then work with the trainee to plan the session content. We post the topic and article on Monday. At 8 p.m. EST on Wednesday, the trainee posts a series of six to eight tweets summarizing the article. The faculty then asks the invited expert (and audience at large) a series of predetermined questions. Anyone can respond, share their opinion, and direct their own questions toward the moderator and expert who continually check their notifications and respond in real time. This brews into an hour-long discussion which covers not only the methodologic aspects of the article, but clinical practice in general. Discussions often trickle into the next day as people from different time zones participate. Everyone uses #GIJC at the end of their tweets which assists those following the article and facilitates indexing for future review. For those who miss or want to review sessions, we conveniently summarize all articles and corresponding discussions in a monthly publication, @GiJournal Digest, that is posted on Twitter for anyone to download, read and enjoy (Figure 1).

How is this different from any other journal club?

Atoosa Rabiee, MD (@AtoosaRabiee)

@GiJournal is unique in that it provides trainees and practicing gastroenterologists access to interactive discussions with both authors and world-renowned experts in the field. Online journal clubs operate with a flattened hierarchy; as such, they inherently break down access barriers to both the researchers who performed the study and key opinion leaders who commonly participate. There is no boundary as far as institutions or even countries. As a result, our platform has uncovered an unexpected degree of interest in live online discussion, and we have enjoyed collaborating and learning from experts from all over the world. @GiJournal also differs from conventional journal clubs by allowing trainees the opportunity to collaborate and engage with mentors from other institutions. As such, trainees develop relationships with experts in the field outside their home institutions, experts with whom they may not have had contact otherwise.

Although worldwide participation is a key strength of the online @GiJournal platform, it may be challenging for some members to attend the live discussion based on time difference. We account for this in two ways. First, participants are encouraged to continue with comments and questions afterward at their convenience, which allows experts and moderators to continue the conversation, often for several days. Second, to promote inclusivity, we have created a unique, customized publication to summarize and present the key points of conversation for each session. This asynchronous access is a quality not found in more traditional journal club formats. Finally, studies have shown that articles shared on social media tend to have increased citations and higher Altmetric scores.

What are the opportunities for trainees and recent graduates?

Sunil Amin, MD, MPH (@SunilAminMD)

Our surveys have shown that 30%-45% of the @GiJournal discussion participants are trainees. Both gastroenterology fellows and internal medicine residents from around the world are an integral part of each specialty panel for the weekly @GIjournal discussions. Trainees are paired up with a specific faculty mentor and together they choose an article for discussion, create a summary, informal twitter poll, and questions for the discussion. This direct access provides an opportunity for trainees to interact, ask questions, and learn from faculty in an informal atmosphere.

We have heard from multiple trainees who have developed long-term relationships with the experts and faculty mentors they worked with and are now also working on research projects. Additionally, trainees can bring the expertise they have now acquired back to their home institutions to pick articles, add specific teaching points, and enrich their local journal club discussions. Finally, trainees who present on the @GiJournal platform are given unique visibility to the many faculty members and opinion leaders participating in each discussion. This may facilitate future networking opportunities and enhance their CVs for future fellowship or employment applications.

Plans for the future?

Allon Kahn, MD (@AllonKahn)

Despite significant evolution and growth in @GiJournal over the past year, we are still actively working to expand our platform. Modes of online medical education, specifically Twitter-based GI journal club discussions, remain in their infancy. We see this @GiJournal as an opportunity for innovation as we plan for the year ahead. Our top priority for the upcoming year includes obtaining CME approval, which we are currently developing with Integrity CE (an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education–accredited provider of CME for health care professionals). This will give an opportunity for the participants to be awarded CME credit when they participate in our weekly discussions. Other options being explored include starting a podcast and translation of @GiJournal Digest in different languages to reach a wider international audience. Furthermore, with the continued expansion of GI leaders and experts joining and engaging in Twitter, our options for unique and multidisciplinary discussion topics will continue to grow.

How can you join the @GiJournal discussions?

@SultanMahmoodMD

Joining the journal club discussion is easy. Just follow the @GiJournal handle on Twitter and turn on the notifications icon. Although we encourage everyone to “actively” participate in the discussion by asking questions or sharing your personal experience, joining the discussion as an “observer” is also a great way to learn. The discussion starts at 8 p.m. EST every Wednesday. Follow the #GIJC and the @GiJournal handle as questions are posted by the faculty moderator and answered by the experts. Even if you miss the discussion, the @GiJournal Digest is a great way to recap the discussions in an easy-to-read PDF format. The @GiJournal Digest is a monthly publication that archives the four @GiJournal club discussions in the previous month. Follow the link below to access the recent publications: http://ow.ly/uu2550C3RXX

Conclusion

In summary, we believe Twitter-based journal clubs offer an engaging way of virtual learning from the comfort of one’s home and a convenient way to directly interact with the experts. The success of @GiJournal highlights the importance of social media for medical education in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology and we look forward to developing this endeavor further.

Dr. Mahmood is clinical assistant professor of medicine, co–program director of the GI fellowship program, UB division of gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition, State University of New York at Buffalo; Dr. Rabiee is assistant professor of medicine, director of hepatology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Washington; Dr. Amin is assistant professor of medicine, director of endoscopy, The Lennar Foundation Medical Center, division of digestive health and liver disease, department of medicine, University of Miami; Dr. Kahn is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Dr. Akbar Ali is a gastroenterology fellow in the division of digestive diseases and nutrition, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

The last decade has seen an increased focus on the use of social media for medical education. Twitter, with over 330 million active users, is the most popular social media platform for medical education. We describe here our recent initiative to establish a weekly online gastroenterology-focused journal club on Twitter.

How was the idea conceived?

Sultan Mahmood, MD (@SultanMahmoodMD)

I joined #GITwitter at the end of 2019 and started following some of the leading experts in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. It was a pleasant surprise to see how easy it was to engage with them and get expert opinions from across the world in real time. #MondayNightIBD, led by Aline Charabaty, MD, had become a phenomenon in the GI community and changed the perception of medical education in the digital world. There were online journal clubs for different medical subspecialties, including #NephroJC, #HOJournalClub, and #DermJC, but none for gastroenterology. Realizing this opportunity, and with guidance from Dr. Charabaty, we started @GiJournal in December of 2019 with weekly discussions.

@GiJournal started off as an informal discussion in which we would post a summary of the article and invite an expert in the field to comment. However, the interest in the journal club quickly took off as we gained more followers and a worldwide audience joined our journal club discussions on a weekly basis. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and endoscopy suites around the word closed, interest in online medical education grew. @GIJournal provided a platform for trainees and practicing physicians alike to stay up to date with the latest publications from the comfort of their homes. Needless to say, the journal club has evolved since its inception in that we now work with a team of experts and trainees who run the journal club on a rotating basis.

How does @GiJournal work?

Ijlal Akbar Ali, MD (@IjlalAkbar)

We have a large editorial board with volunteer faculty and trainees, all divided into four special interest groups (general GI/inflammatory bowel disease, interventional endoscopy/bariatric endoscopy, hepatology, and esophageal/motility disorders). Each week, a faculty member and a trainee pick a recently published article from a high-impact GI-focused journal. We also try to invite an expert of international repute (often the authors of the article themselves!) to engage as well. The faculty moderator and invited expert then work with the trainee to plan the session content. We post the topic and article on Monday. At 8 p.m. EST on Wednesday, the trainee posts a series of six to eight tweets summarizing the article. The faculty then asks the invited expert (and audience at large) a series of predetermined questions. Anyone can respond, share their opinion, and direct their own questions toward the moderator and expert who continually check their notifications and respond in real time. This brews into an hour-long discussion which covers not only the methodologic aspects of the article, but clinical practice in general. Discussions often trickle into the next day as people from different time zones participate. Everyone uses #GIJC at the end of their tweets which assists those following the article and facilitates indexing for future review. For those who miss or want to review sessions, we conveniently summarize all articles and corresponding discussions in a monthly publication, @GiJournal Digest, that is posted on Twitter for anyone to download, read and enjoy (Figure 1).

How is this different from any other journal club?

Atoosa Rabiee, MD (@AtoosaRabiee)

@GiJournal is unique in that it provides trainees and practicing gastroenterologists access to interactive discussions with both authors and world-renowned experts in the field. Online journal clubs operate with a flattened hierarchy; as such, they inherently break down access barriers to both the researchers who performed the study and key opinion leaders who commonly participate. There is no boundary as far as institutions or even countries. As a result, our platform has uncovered an unexpected degree of interest in live online discussion, and we have enjoyed collaborating and learning from experts from all over the world. @GiJournal also differs from conventional journal clubs by allowing trainees the opportunity to collaborate and engage with mentors from other institutions. As such, trainees develop relationships with experts in the field outside their home institutions, experts with whom they may not have had contact otherwise.

Although worldwide participation is a key strength of the online @GiJournal platform, it may be challenging for some members to attend the live discussion based on time difference. We account for this in two ways. First, participants are encouraged to continue with comments and questions afterward at their convenience, which allows experts and moderators to continue the conversation, often for several days. Second, to promote inclusivity, we have created a unique, customized publication to summarize and present the key points of conversation for each session. This asynchronous access is a quality not found in more traditional journal club formats. Finally, studies have shown that articles shared on social media tend to have increased citations and higher Altmetric scores.

What are the opportunities for trainees and recent graduates?

Sunil Amin, MD, MPH (@SunilAminMD)

Our surveys have shown that 30%-45% of the @GiJournal discussion participants are trainees. Both gastroenterology fellows and internal medicine residents from around the world are an integral part of each specialty panel for the weekly @GIjournal discussions. Trainees are paired up with a specific faculty mentor and together they choose an article for discussion, create a summary, informal twitter poll, and questions for the discussion. This direct access provides an opportunity for trainees to interact, ask questions, and learn from faculty in an informal atmosphere.

We have heard from multiple trainees who have developed long-term relationships with the experts and faculty mentors they worked with and are now also working on research projects. Additionally, trainees can bring the expertise they have now acquired back to their home institutions to pick articles, add specific teaching points, and enrich their local journal club discussions. Finally, trainees who present on the @GiJournal platform are given unique visibility to the many faculty members and opinion leaders participating in each discussion. This may facilitate future networking opportunities and enhance their CVs for future fellowship or employment applications.

Plans for the future?

Allon Kahn, MD (@AllonKahn)

Despite significant evolution and growth in @GiJournal over the past year, we are still actively working to expand our platform. Modes of online medical education, specifically Twitter-based GI journal club discussions, remain in their infancy. We see this @GiJournal as an opportunity for innovation as we plan for the year ahead. Our top priority for the upcoming year includes obtaining CME approval, which we are currently developing with Integrity CE (an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education–accredited provider of CME for health care professionals). This will give an opportunity for the participants to be awarded CME credit when they participate in our weekly discussions. Other options being explored include starting a podcast and translation of @GiJournal Digest in different languages to reach a wider international audience. Furthermore, with the continued expansion of GI leaders and experts joining and engaging in Twitter, our options for unique and multidisciplinary discussion topics will continue to grow.

How can you join the @GiJournal discussions?

@SultanMahmoodMD

Joining the journal club discussion is easy. Just follow the @GiJournal handle on Twitter and turn on the notifications icon. Although we encourage everyone to “actively” participate in the discussion by asking questions or sharing your personal experience, joining the discussion as an “observer” is also a great way to learn. The discussion starts at 8 p.m. EST every Wednesday. Follow the #GIJC and the @GiJournal handle as questions are posted by the faculty moderator and answered by the experts. Even if you miss the discussion, the @GiJournal Digest is a great way to recap the discussions in an easy-to-read PDF format. The @GiJournal Digest is a monthly publication that archives the four @GiJournal club discussions in the previous month. Follow the link below to access the recent publications: http://ow.ly/uu2550C3RXX

Conclusion

In summary, we believe Twitter-based journal clubs offer an engaging way of virtual learning from the comfort of one’s home and a convenient way to directly interact with the experts. The success of @GiJournal highlights the importance of social media for medical education in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology and we look forward to developing this endeavor further.

Dr. Mahmood is clinical assistant professor of medicine, co–program director of the GI fellowship program, UB division of gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition, State University of New York at Buffalo; Dr. Rabiee is assistant professor of medicine, director of hepatology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Washington; Dr. Amin is assistant professor of medicine, director of endoscopy, The Lennar Foundation Medical Center, division of digestive health and liver disease, department of medicine, University of Miami; Dr. Kahn is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Dr. Akbar Ali is a gastroenterology fellow in the division of digestive diseases and nutrition, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

Case of the inappropriate endoscopy referral

A 53-year-old woman was referred for surveillance colonoscopy. She is a current smoker with a history of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, and two diminutive hyperplastic polyps found on average-risk screening colonoscopy 3 years previously. Her prep at the time was excellent and she was advised to return in 10 years for follow-up. She has taken the day off work, arranged for a driver, is prepped, and is on your schedule for a colonoscopy for a “history of polyps.” Is this an appropriate referral and how should you handle it?

Most of us have had questionable referrals on our endoscopy schedules. While judgments can vary among providers about when a patient should undergo a procedure or what intervention is most needed, some direct-access referrals for endoscopy are considered inappropriate by most standards. In examining referrals for colonoscopy, studies have shown that as many as 23% of screening colonoscopies among Medicare beneficiaries and 14.2% of Veterans Affairs patients in a large colorectal cancer screening study are inappropriate.1,2 A prospective multicenter study found 29% of colonoscopies to be inappropriate, and surveillance studies were confirmed as the most frequent source of inappropriate procedures.3,4 Endoscopies are performed so frequently, effectively, and safely that they can be readily scheduled by gastroenterologists and nongastroenterologists alike. Open access has facilitated and expedited needed procedures, providing benefit to patient and provider and freeing clinic visit time for more complex consults. But while endoscopy is very safe, it is not without risk or cost. What should be the response when a patient in the endoscopy unit appears to be inappropriately referred?

The first step is to determine what is inappropriate. There are several situations when a procedure might be considered inappropriate, particularly when we try to apply ethical principles.

1. The performance of the procedure is contrary to society guidelines. The American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American College of Gastroenterology publish clinical guidelines. These documents are drafted after rigorous research and literature review, and the strength of the recommendations is confirmed by incorporation of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology. Such guidelines allow gastroenterologists across the country to practice confidently in a manner consistent with the current available data and the standards of care for the GI community. A patient who is referred for a procedure for an indication that does not adhere to – or contradicts – guidelines, may be at risk for substandard care and possibly at risk for harm. It is the physician’s ethical responsibility to provide the most “good” and the least harm for patients, consistent with the ethical principle of beneficence.

Guidelines, however, are not mandates, and an argument may be made that in order to provide the best care, alternatives may be offered to a patient. Some circumstances require clinical judgments based on unique patient characteristics and the need for individualized care. As a rule, however, the goal of guidelines is to assist doctors in providing the best care.

2. The procedure is not the correct test for the clinical question. While endoscopy can address many clinical queries, endoscopy is not always the right procedure for a specific medical question. A patient referred for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out gastroparesis is being subjected to the wrong test to answer the clinical question. Some information may be obtained from an EGD (e.g., retained food may suggest dysmotility or the patient could have gastric outlet obstruction) but this is not the recommended initial management step. Is it reasonable to proceed with a test that cannot answer the question asked? Continuing with the endoscopy would not enhance beneficence and might be a futile service for the patient. Is this doing the best for the patient?

3. The risks of the procedure outweigh the benefits. Some procedures may be consistent with guidelines and able to answer the questions asked, but may present more risk than benefit. Should an elderly patient with multiple significant comorbidities and a likely limited life span undergo a follow-up colonoscopy even at an appropriate interval? The principle of nonmaleficence is the clear standard here.

4. The intent for doing the procedure has questionable merit. Some patients may request an EGD at the time of the screening colonoscopy just to “check,” regardless of symptoms or risk category. A patient has a right to make her/his own decisions but patient autonomy should not be an excuse for a nonindicated procedure.

In the case of the 53-year-old woman referred for surveillance colonoscopy, the physician needs to consider whether performing the test is inappropriate for any of the above reasons. First and foremost, is it doing the most good for the patient?

On the one hand, performing an inappropriately referred procedure contradicts guidelines and may present undue risk of complication from anesthesia or endoscopy. Would the physician be ethically compromised in this situation, or even legally liable should a complication arise during a procedure done for a questionable indication?

On the other hand, canceling such a procedure creates multiple dilemmas. The autonomy and the convenience of the patient need to be respected. The patient who has followed all the instructions, is prepped, has taken off work, arranged for transportation, and wants to have the procedure done may have difficulty accepting a cancellation. Colonoscopy is a safe test. Is it the right thing to cancel her procedure because of an imprudent referral? Would this undermine the patient’s confidence in her referring provider? Physicians may face other pressures to proceed, such as practice or institutional restraints that discourage same-day cancellations. Maintenance of robust financial practices, stable referral sources, and excellent patient satisfaction measures are critical to running an efficient endoscopy unit and maximizing patient service and care.

Is there a sensible way to address the dilemma? One approach is simply to move ahead with the procedure if the physician feels that the benefits outweigh the medical and ethical risks. Besides patient convenience, other “benefits” could be relevant: clinical value from an unexpected finding, affirmation of the patient’s invested time and effort, and avoidance of the apparent undermining of the authority of a referring colleague. Finally, maintaining productive and efficient practices or institutions ultimately allows for better patient care. The physician can explain the enhanced risks, present the alternatives, and – perhaps in less time than the ethical deliberations might take – complete the procedure and have the patient resting comfortably in the recovery unit.

An alternative approach is to cancel the procedure if the physician feels that the indication is not legitimate, or that the risks to the patient and the physician are significant. Explaining the cancellation can be difficult but may be the right decision if ethical principles of beneficence are upheld. It is understood that procedures consume health care resources and can present an undue expense to society if done for improper reasons. Unnecessary procedures clutter schedules for patients who truly need an endoscopy.

Neither approach is completely satisfying, although moving forward with a likely very safe procedure is often the easiest step and probably what many physicians do in this setting.

Is there a better way to approach this problem? Preventing the ethical dilemma is the ideal scenario, although not always feasible. Here are some suggestions to consider.

Reviewing referrals prior to the procedure day allows endoscopists to contact and cancel patients if needed, before the prep and travel begin. This addresses the convenience aspects but not the issue regarding the underlying indication.

The most important step toward avoiding inappropriate referrals is better education for referring providers. Even gastroenterologists, let alone primary care physicians, may struggle to stay current on changing clinical GI guidelines. Colorectal cancer screening, for example, is an area that gives gastroenterologists an opportunity to communicate with and educate colleagues about appropriate management. Keeping our referral base up to date about guidelines and prep and safety recommendations will likely reduce the number of inappropriate colonoscopy referrals and provide many of the benefits described above.

Providing the best care for patients by adhering to medical ethical principles is the goal of our work as physicians. Implementing this goal may demand tough decisions.

Dr. Fisher is professor of clinical medicine and director of small-bowel imaging, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Sheffield KM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Apr 8;173(7):542-50.

2. Powell AA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jun;30(6):732-41.

3. Petruzziello L et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(7):590-4.

4. Kapila N et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(10):2798-805.

A 53-year-old woman was referred for surveillance colonoscopy. She is a current smoker with a history of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, and two diminutive hyperplastic polyps found on average-risk screening colonoscopy 3 years previously. Her prep at the time was excellent and she was advised to return in 10 years for follow-up. She has taken the day off work, arranged for a driver, is prepped, and is on your schedule for a colonoscopy for a “history of polyps.” Is this an appropriate referral and how should you handle it?

Most of us have had questionable referrals on our endoscopy schedules. While judgments can vary among providers about when a patient should undergo a procedure or what intervention is most needed, some direct-access referrals for endoscopy are considered inappropriate by most standards. In examining referrals for colonoscopy, studies have shown that as many as 23% of screening colonoscopies among Medicare beneficiaries and 14.2% of Veterans Affairs patients in a large colorectal cancer screening study are inappropriate.1,2 A prospective multicenter study found 29% of colonoscopies to be inappropriate, and surveillance studies were confirmed as the most frequent source of inappropriate procedures.3,4 Endoscopies are performed so frequently, effectively, and safely that they can be readily scheduled by gastroenterologists and nongastroenterologists alike. Open access has facilitated and expedited needed procedures, providing benefit to patient and provider and freeing clinic visit time for more complex consults. But while endoscopy is very safe, it is not without risk or cost. What should be the response when a patient in the endoscopy unit appears to be inappropriately referred?

The first step is to determine what is inappropriate. There are several situations when a procedure might be considered inappropriate, particularly when we try to apply ethical principles.

1. The performance of the procedure is contrary to society guidelines. The American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American College of Gastroenterology publish clinical guidelines. These documents are drafted after rigorous research and literature review, and the strength of the recommendations is confirmed by incorporation of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology. Such guidelines allow gastroenterologists across the country to practice confidently in a manner consistent with the current available data and the standards of care for the GI community. A patient who is referred for a procedure for an indication that does not adhere to – or contradicts – guidelines, may be at risk for substandard care and possibly at risk for harm. It is the physician’s ethical responsibility to provide the most “good” and the least harm for patients, consistent with the ethical principle of beneficence.

Guidelines, however, are not mandates, and an argument may be made that in order to provide the best care, alternatives may be offered to a patient. Some circumstances require clinical judgments based on unique patient characteristics and the need for individualized care. As a rule, however, the goal of guidelines is to assist doctors in providing the best care.

2. The procedure is not the correct test for the clinical question. While endoscopy can address many clinical queries, endoscopy is not always the right procedure for a specific medical question. A patient referred for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out gastroparesis is being subjected to the wrong test to answer the clinical question. Some information may be obtained from an EGD (e.g., retained food may suggest dysmotility or the patient could have gastric outlet obstruction) but this is not the recommended initial management step. Is it reasonable to proceed with a test that cannot answer the question asked? Continuing with the endoscopy would not enhance beneficence and might be a futile service for the patient. Is this doing the best for the patient?

3. The risks of the procedure outweigh the benefits. Some procedures may be consistent with guidelines and able to answer the questions asked, but may present more risk than benefit. Should an elderly patient with multiple significant comorbidities and a likely limited life span undergo a follow-up colonoscopy even at an appropriate interval? The principle of nonmaleficence is the clear standard here.

4. The intent for doing the procedure has questionable merit. Some patients may request an EGD at the time of the screening colonoscopy just to “check,” regardless of symptoms or risk category. A patient has a right to make her/his own decisions but patient autonomy should not be an excuse for a nonindicated procedure.

In the case of the 53-year-old woman referred for surveillance colonoscopy, the physician needs to consider whether performing the test is inappropriate for any of the above reasons. First and foremost, is it doing the most good for the patient?

On the one hand, performing an inappropriately referred procedure contradicts guidelines and may present undue risk of complication from anesthesia or endoscopy. Would the physician be ethically compromised in this situation, or even legally liable should a complication arise during a procedure done for a questionable indication?

On the other hand, canceling such a procedure creates multiple dilemmas. The autonomy and the convenience of the patient need to be respected. The patient who has followed all the instructions, is prepped, has taken off work, arranged for transportation, and wants to have the procedure done may have difficulty accepting a cancellation. Colonoscopy is a safe test. Is it the right thing to cancel her procedure because of an imprudent referral? Would this undermine the patient’s confidence in her referring provider? Physicians may face other pressures to proceed, such as practice or institutional restraints that discourage same-day cancellations. Maintenance of robust financial practices, stable referral sources, and excellent patient satisfaction measures are critical to running an efficient endoscopy unit and maximizing patient service and care.

Is there a sensible way to address the dilemma? One approach is simply to move ahead with the procedure if the physician feels that the benefits outweigh the medical and ethical risks. Besides patient convenience, other “benefits” could be relevant: clinical value from an unexpected finding, affirmation of the patient’s invested time and effort, and avoidance of the apparent undermining of the authority of a referring colleague. Finally, maintaining productive and efficient practices or institutions ultimately allows for better patient care. The physician can explain the enhanced risks, present the alternatives, and – perhaps in less time than the ethical deliberations might take – complete the procedure and have the patient resting comfortably in the recovery unit.

An alternative approach is to cancel the procedure if the physician feels that the indication is not legitimate, or that the risks to the patient and the physician are significant. Explaining the cancellation can be difficult but may be the right decision if ethical principles of beneficence are upheld. It is understood that procedures consume health care resources and can present an undue expense to society if done for improper reasons. Unnecessary procedures clutter schedules for patients who truly need an endoscopy.

Neither approach is completely satisfying, although moving forward with a likely very safe procedure is often the easiest step and probably what many physicians do in this setting.

Is there a better way to approach this problem? Preventing the ethical dilemma is the ideal scenario, although not always feasible. Here are some suggestions to consider.

Reviewing referrals prior to the procedure day allows endoscopists to contact and cancel patients if needed, before the prep and travel begin. This addresses the convenience aspects but not the issue regarding the underlying indication.

The most important step toward avoiding inappropriate referrals is better education for referring providers. Even gastroenterologists, let alone primary care physicians, may struggle to stay current on changing clinical GI guidelines. Colorectal cancer screening, for example, is an area that gives gastroenterologists an opportunity to communicate with and educate colleagues about appropriate management. Keeping our referral base up to date about guidelines and prep and safety recommendations will likely reduce the number of inappropriate colonoscopy referrals and provide many of the benefits described above.

Providing the best care for patients by adhering to medical ethical principles is the goal of our work as physicians. Implementing this goal may demand tough decisions.

Dr. Fisher is professor of clinical medicine and director of small-bowel imaging, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Sheffield KM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Apr 8;173(7):542-50.

2. Powell AA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jun;30(6):732-41.

3. Petruzziello L et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(7):590-4.

4. Kapila N et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(10):2798-805.

A 53-year-old woman was referred for surveillance colonoscopy. She is a current smoker with a history of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, and two diminutive hyperplastic polyps found on average-risk screening colonoscopy 3 years previously. Her prep at the time was excellent and she was advised to return in 10 years for follow-up. She has taken the day off work, arranged for a driver, is prepped, and is on your schedule for a colonoscopy for a “history of polyps.” Is this an appropriate referral and how should you handle it?