User login

Understanding GERD phenotypes

Approximately 30% of U.S. adults experience troublesome reflux symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and noncardiac chest pain. Because the mechanisms driving symptoms vary across patients, phenotyping patients via a step-wise diagnostic framework effectively guides personalized management in GERD.

For instance, PPI trials are appropriate when esophageal symptoms are present, whereas up-front reflux monitoring rather than empiric PPI trials are recommended for evaluation of isolated extra-esophageal symptoms. All patients undergoing evaluation for GERD should receive counseling on weight management and lifestyle modifications as well as the brain-gut axis relationship. In the common scenario of inadequate symptom response to PPIs, upper GI endoscopy is recommended to assess for erosive reflux disease (which confirms a diagnosis of GERD) as well as the anti-reflux barrier integrity. For instance, the presence of a large hiatal hernia and/or grade III/IV gastro-esophageal flap valve may point to mechanical gastro-esophageal reflux as a driver of symptoms and lower the threshold for surgical referral. In the absence of erosive reflux disease the next recommended step is ambulatory reflux monitoring off PPI therapy, either as prolonged wireless telemetry (which can be done concurrently with index endoscopy as long as PPI was discontinued > 7 days) or 24-hour transnasal pH-impedance catheter-based testing. Studies suggest that 96-hour monitoring is optimal for diagnostic accuracy and to guide therapeutic strategies.

Patients without evidence of GERD on endoscopy or ambulatory reflux monitoring likely have a functional esophageal disorder for which therapy hinges on pharmacologic neuromodulation or behavioral interventions as well as PPI cessation.

Alternatively, management for GERD (erosive or nonerosive) aims to optimize lifestyle, PPI therapy and the individualized use of adjunctive therapy, which include H2-receptor antagonists, alginate antacids, GABA agonists, neuromodulation and/or behavioral interventions. Surgical or endoscopic antireflux interventions are also an option for refractory GERD. Prior to intervention, achalasia must be excluded (typically with esophageal manometry), and confirmation of PPI refractory GERD on pH-impedance monitoring on PPI is of value, particularly when the phenotype is unclear. Again, the choice of antireflux intervention (e.g., laparoscopic fundoplication, magnetic sphincter augmentation, transoral incisionless fundoplication, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) should be individualized to the patient’s anatomy, physiology, and clinical profile.

A multitude of treatment options are available to manage GERD, including behavioral interventions, lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopic/surgical interventions. However, not every treatment strategy is appropriate for every patient. Data gathered from the step-down diagnostic approach, which starts with clinical presentation, then endoscopy, then reflux monitoring, then esophageal physiologic testing, helps determine the GERD phenotype and effectively guide therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati is associate professor of clinical medicine, and medical director, UCSD Center for Esophageal Diseases; director, GI Motility Lab, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif. She disclosed ties with Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, StatLinkMD, Medscape, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and RJS Mediagnostix. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Approximately 30% of U.S. adults experience troublesome reflux symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and noncardiac chest pain. Because the mechanisms driving symptoms vary across patients, phenotyping patients via a step-wise diagnostic framework effectively guides personalized management in GERD.

For instance, PPI trials are appropriate when esophageal symptoms are present, whereas up-front reflux monitoring rather than empiric PPI trials are recommended for evaluation of isolated extra-esophageal symptoms. All patients undergoing evaluation for GERD should receive counseling on weight management and lifestyle modifications as well as the brain-gut axis relationship. In the common scenario of inadequate symptom response to PPIs, upper GI endoscopy is recommended to assess for erosive reflux disease (which confirms a diagnosis of GERD) as well as the anti-reflux barrier integrity. For instance, the presence of a large hiatal hernia and/or grade III/IV gastro-esophageal flap valve may point to mechanical gastro-esophageal reflux as a driver of symptoms and lower the threshold for surgical referral. In the absence of erosive reflux disease the next recommended step is ambulatory reflux monitoring off PPI therapy, either as prolonged wireless telemetry (which can be done concurrently with index endoscopy as long as PPI was discontinued > 7 days) or 24-hour transnasal pH-impedance catheter-based testing. Studies suggest that 96-hour monitoring is optimal for diagnostic accuracy and to guide therapeutic strategies.

Patients without evidence of GERD on endoscopy or ambulatory reflux monitoring likely have a functional esophageal disorder for which therapy hinges on pharmacologic neuromodulation or behavioral interventions as well as PPI cessation.

Alternatively, management for GERD (erosive or nonerosive) aims to optimize lifestyle, PPI therapy and the individualized use of adjunctive therapy, which include H2-receptor antagonists, alginate antacids, GABA agonists, neuromodulation and/or behavioral interventions. Surgical or endoscopic antireflux interventions are also an option for refractory GERD. Prior to intervention, achalasia must be excluded (typically with esophageal manometry), and confirmation of PPI refractory GERD on pH-impedance monitoring on PPI is of value, particularly when the phenotype is unclear. Again, the choice of antireflux intervention (e.g., laparoscopic fundoplication, magnetic sphincter augmentation, transoral incisionless fundoplication, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) should be individualized to the patient’s anatomy, physiology, and clinical profile.

A multitude of treatment options are available to manage GERD, including behavioral interventions, lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopic/surgical interventions. However, not every treatment strategy is appropriate for every patient. Data gathered from the step-down diagnostic approach, which starts with clinical presentation, then endoscopy, then reflux monitoring, then esophageal physiologic testing, helps determine the GERD phenotype and effectively guide therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati is associate professor of clinical medicine, and medical director, UCSD Center for Esophageal Diseases; director, GI Motility Lab, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif. She disclosed ties with Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, StatLinkMD, Medscape, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and RJS Mediagnostix. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

Approximately 30% of U.S. adults experience troublesome reflux symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and noncardiac chest pain. Because the mechanisms driving symptoms vary across patients, phenotyping patients via a step-wise diagnostic framework effectively guides personalized management in GERD.

For instance, PPI trials are appropriate when esophageal symptoms are present, whereas up-front reflux monitoring rather than empiric PPI trials are recommended for evaluation of isolated extra-esophageal symptoms. All patients undergoing evaluation for GERD should receive counseling on weight management and lifestyle modifications as well as the brain-gut axis relationship. In the common scenario of inadequate symptom response to PPIs, upper GI endoscopy is recommended to assess for erosive reflux disease (which confirms a diagnosis of GERD) as well as the anti-reflux barrier integrity. For instance, the presence of a large hiatal hernia and/or grade III/IV gastro-esophageal flap valve may point to mechanical gastro-esophageal reflux as a driver of symptoms and lower the threshold for surgical referral. In the absence of erosive reflux disease the next recommended step is ambulatory reflux monitoring off PPI therapy, either as prolonged wireless telemetry (which can be done concurrently with index endoscopy as long as PPI was discontinued > 7 days) or 24-hour transnasal pH-impedance catheter-based testing. Studies suggest that 96-hour monitoring is optimal for diagnostic accuracy and to guide therapeutic strategies.

Patients without evidence of GERD on endoscopy or ambulatory reflux monitoring likely have a functional esophageal disorder for which therapy hinges on pharmacologic neuromodulation or behavioral interventions as well as PPI cessation.

Alternatively, management for GERD (erosive or nonerosive) aims to optimize lifestyle, PPI therapy and the individualized use of adjunctive therapy, which include H2-receptor antagonists, alginate antacids, GABA agonists, neuromodulation and/or behavioral interventions. Surgical or endoscopic antireflux interventions are also an option for refractory GERD. Prior to intervention, achalasia must be excluded (typically with esophageal manometry), and confirmation of PPI refractory GERD on pH-impedance monitoring on PPI is of value, particularly when the phenotype is unclear. Again, the choice of antireflux intervention (e.g., laparoscopic fundoplication, magnetic sphincter augmentation, transoral incisionless fundoplication, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) should be individualized to the patient’s anatomy, physiology, and clinical profile.

A multitude of treatment options are available to manage GERD, including behavioral interventions, lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopic/surgical interventions. However, not every treatment strategy is appropriate for every patient. Data gathered from the step-down diagnostic approach, which starts with clinical presentation, then endoscopy, then reflux monitoring, then esophageal physiologic testing, helps determine the GERD phenotype and effectively guide therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati is associate professor of clinical medicine, and medical director, UCSD Center for Esophageal Diseases; director, GI Motility Lab, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif. She disclosed ties with Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, StatLinkMD, Medscape, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and RJS Mediagnostix. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2022.

AT DDW 2022

The path to becoming an esophagologist

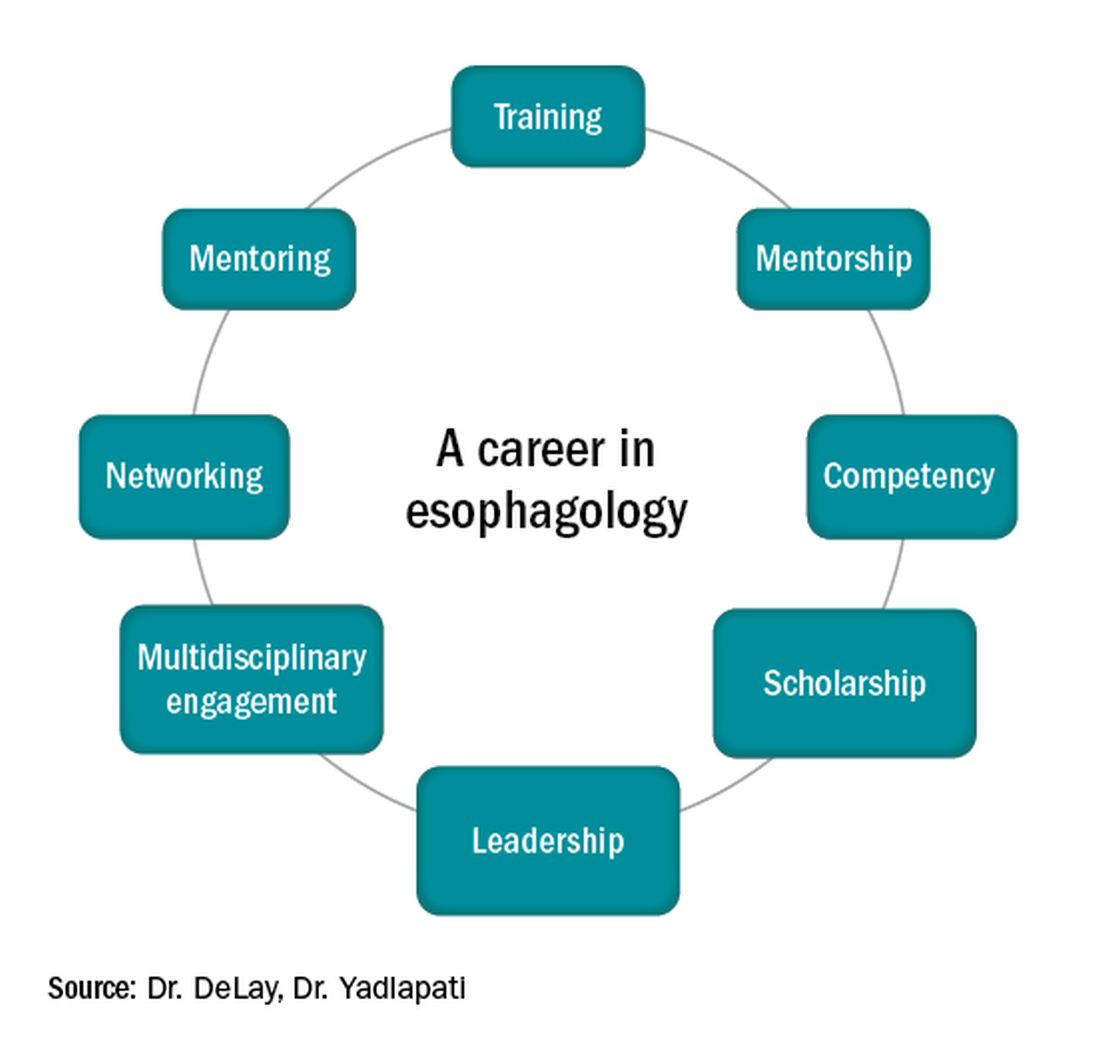

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

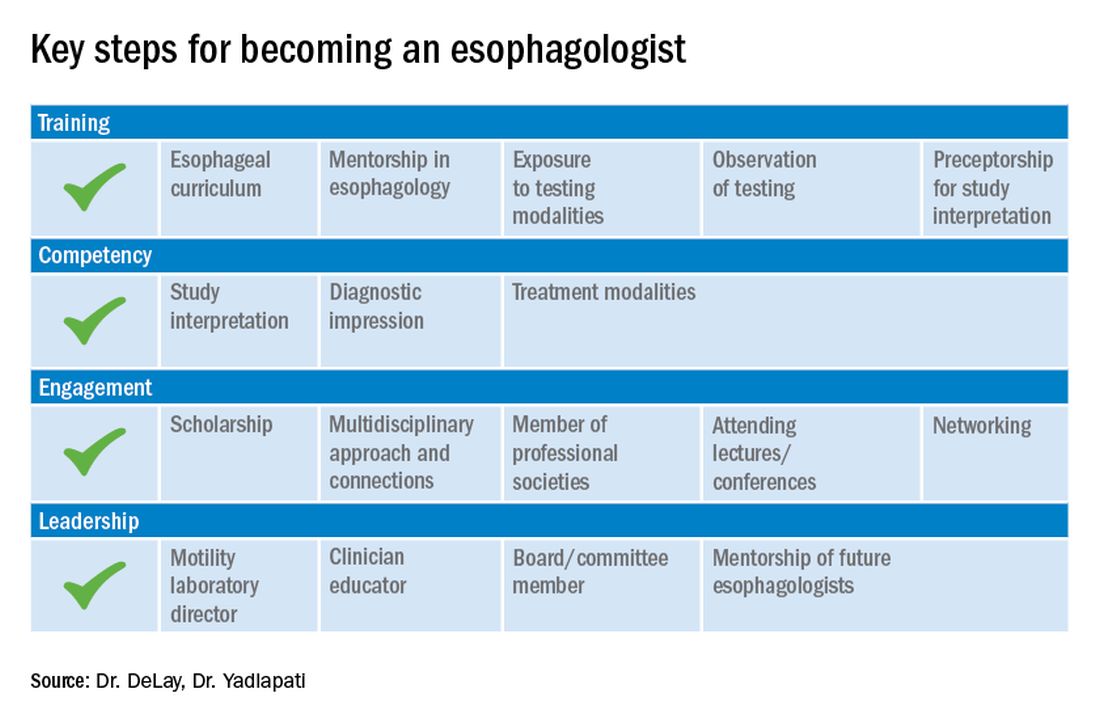

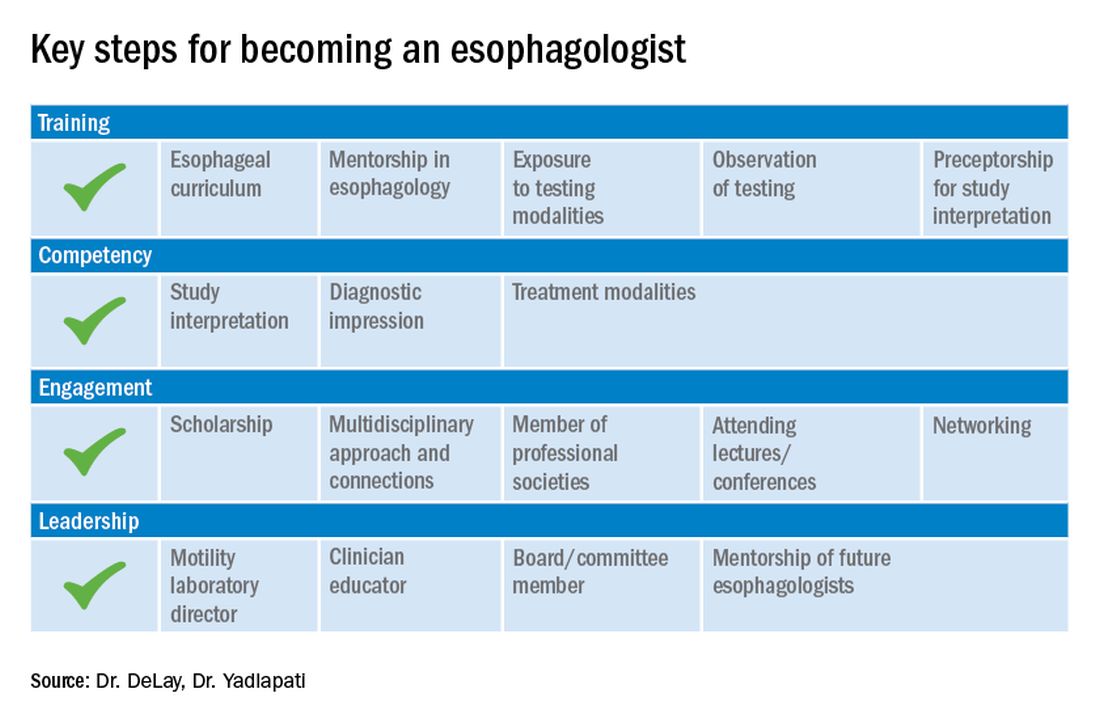

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

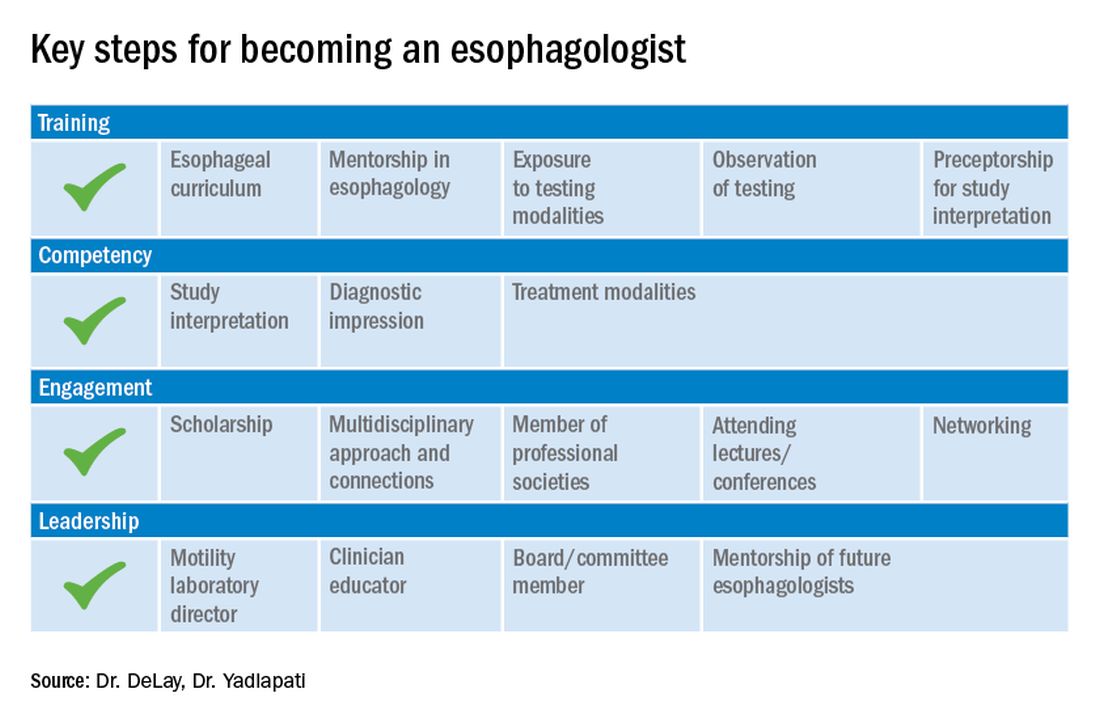

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

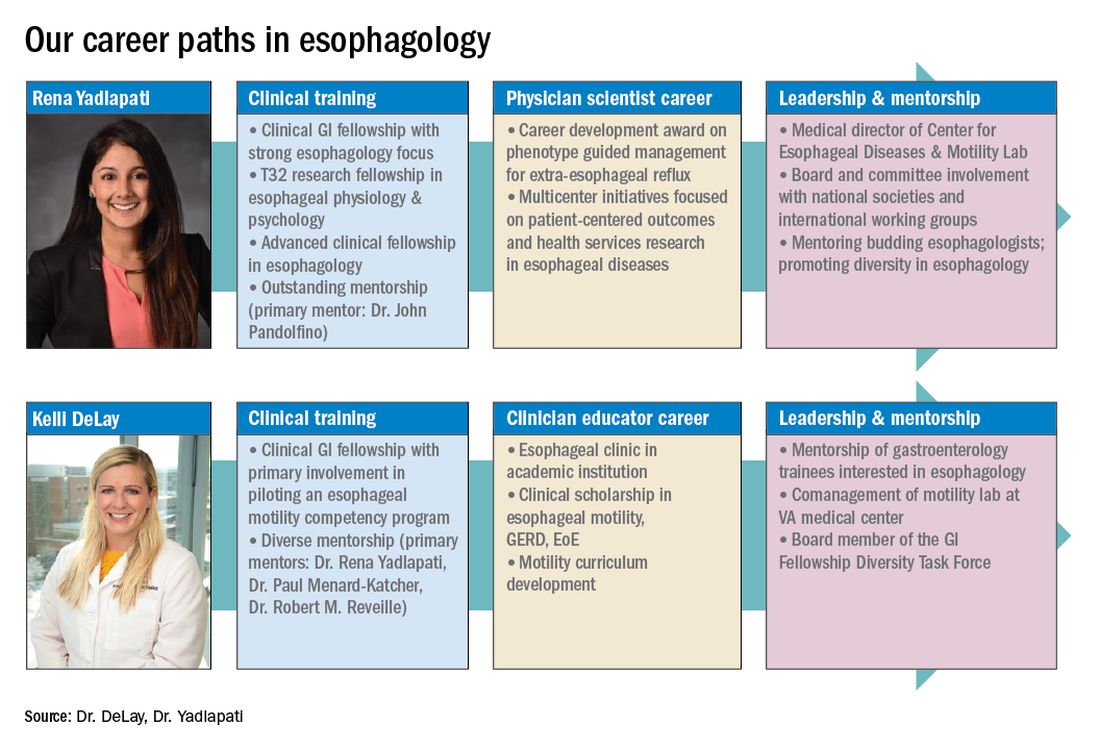

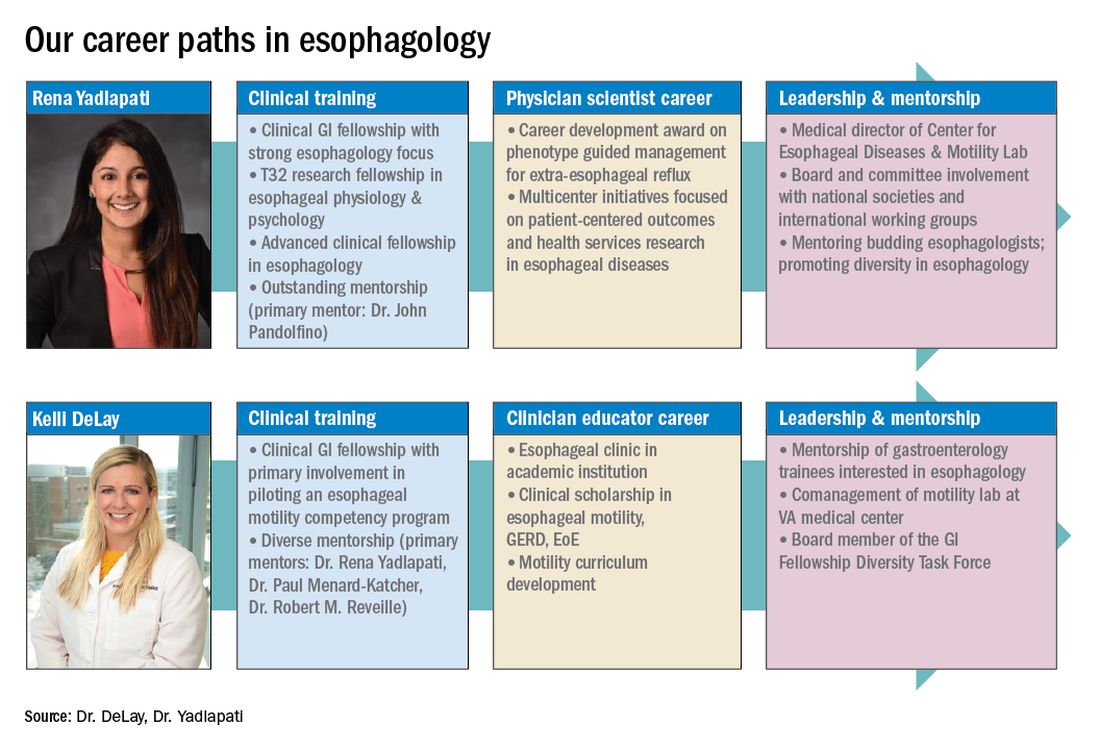

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

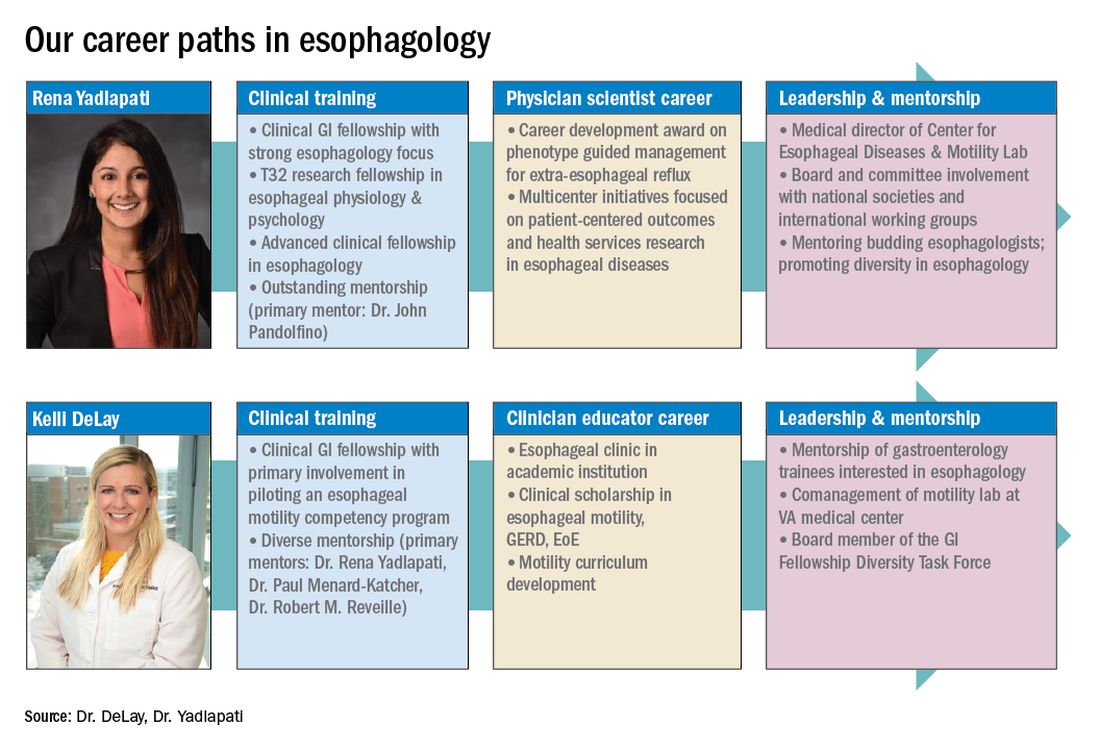

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

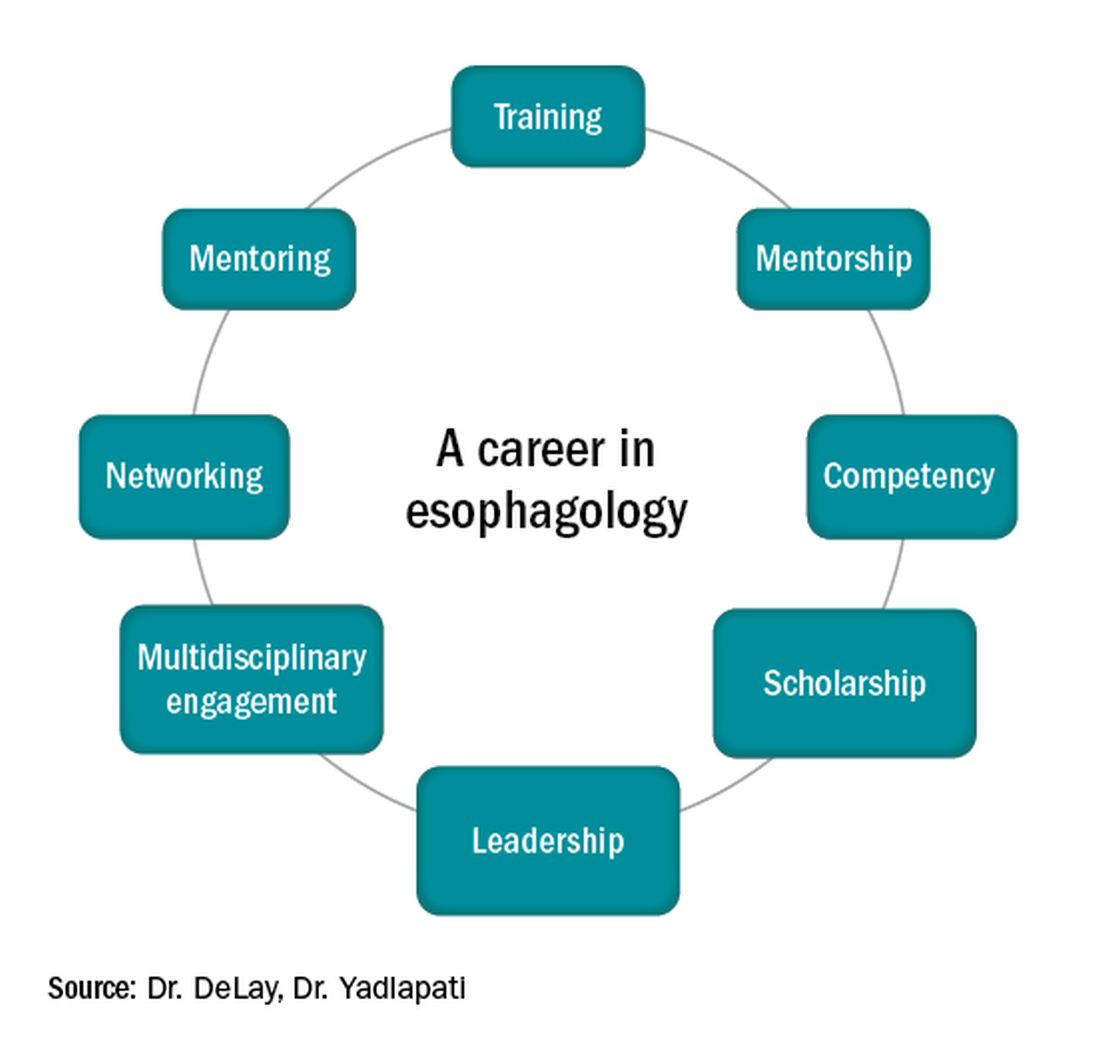

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

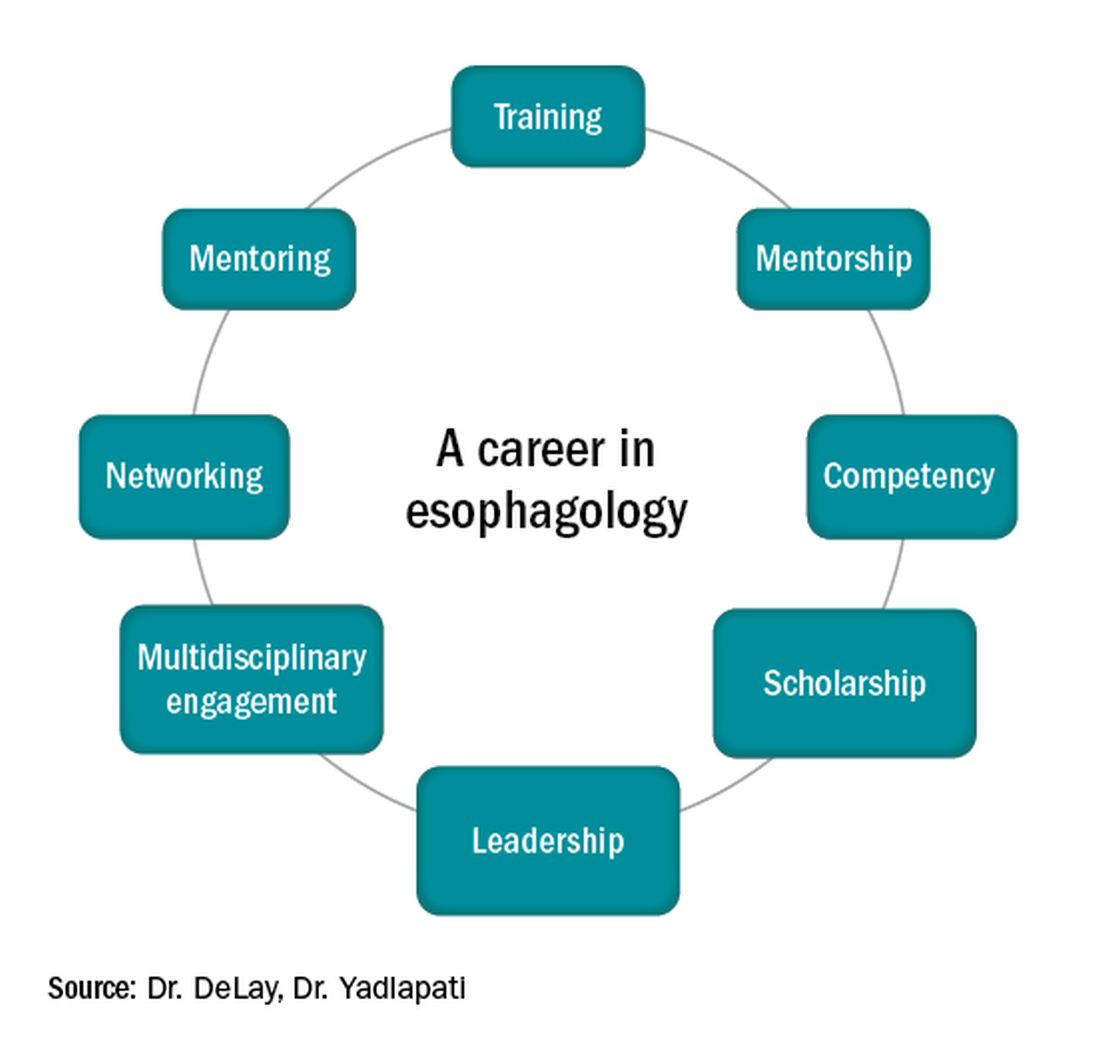

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.