User login

Mindful mentoring

Scenario

A GI faculty member is approached by two medical students who are planning careers in gastroenterology. They are interested in research projects and are very willing to dedicate the necessary time and energy. The faculty member is impressed by their desire and finds themselves recalling their own unsuccessful medical school search for a research mentor. Inspired by their enthusiasm and a desire to “give back,” the faculty member agrees to mentor them and helps them find suitable projects. Primarily because of the students’ hard work and fueled by their desire to produce results that will help their residency applications, the work progresses rapidly. Both students have separate abstracts accepted at a national meeting.

When COVID-19 hits, the faculty member is asked by their department to take on additional administrative and clinical work. They feel they cannot say no. Soon the faculty member finds it difficult to manage these new responsibilities on top of their many research projects, numerous clinical obligations, and additional pressures outside of work. They find they have no time for mentoring or even adequate sleep. Facing burnout, the faculty member is uncertain what to do for these hard-working and very gifted students. How would you recommend they manage their mentoring obligations?

Discussion

Mentorship is a cornerstone of academic medicine. In fact, it has been shown that academic clinicians who serve as mentors publish more papers, get more grants, are promoted faster, and are more likely to stay at their academic institutions with greater career satisfaction.1 However, not every mentor-mentee relationship is mutually beneficial. Usually, it’s the mentees that disproportionately suffer the consequences of a suboptimal relationship.2

Mentorship malpractice occurs when mentors’ behavior crosses a threshold that places the mentees’ success at risk.1,2 While the case above highlights a specific scenario where multiple issues are unfolding, the ability to recognize, address, and most importantly prevent mentorship malpractice ultimately benefits both mentees and mentors.

Understanding the various types of mentorship malpractice is helpful for prevention and course correction. As described by Chopra and colleagues, there are multiple types of passive and active mentorship malpractice.2 The passive forms are characterized by a lack of face-to-face meeting time with mentees and/or a lack of advocacy on the mentees’ behalf. Meanwhile, the active forms occur when the mentor exhibits self-serving behaviors. These can include listing themselves as first author on a mentee’s project or discouraging a mentee from working with other mentors. Mentors must be able to self-check, seek feedback from mentees, and encourage mentees to further their professional networks beyond the boundaries of what the mentor alone can offer. Doing so helps create new opportunities and helps ensure a mutually beneficial relationship.

A great initial step to prevent passive and active mentorship malpractice is to leverage the benefits of team mentorship.2,3 At its core, team mentorship capitalizes on the collective contributions of multiple mentors. Doing so not only provides security during uncertain times, but also allows for a diversity of perspectives, distribution of workload among mentors, and additional support for mentees.3,4 Team mentorship it is particularly important during this current global health crisis, and such an approach from the outset could have significantly improved the scenario above.

For the above scenario, likely a transition in mentorship would be needed. Such transitions, whether short term or long term, require transparency, honesty, and willingness to engage in difficult conversations with mentees. Whether the mentor in the above case engages another faculty to take on the mentees or chooses to find a colleague who will agree to take on other competing demands, it will require time, effort, and energy – all of which are in short supply. When team mentorship is established from the outset, such transitions of mentorship can occur seamlessly and with more ease for all.

Additional considerations for successful mentoring of medical students or early-career physicians include understanding generational differences between the mentor and their mentees. As outlined by Waljee and colleagues, the next generation of trainees and physicians may act in ways that deviate from the norms of academic medicine’s tradition. As a mentor, it is imperative to understand these actions are not intended to disrupt the traditions and norms of health systems.5 For example, the use of technology during rounds can often be misconstrued as disrespectful. However, the underlying intent in many cases is to answer a question or access a helpful reference.

Seeing behavior and actions from the perspective of the mentee is one of the many ways to support and sustain successful mentoring relationships. A mindful approach benefits both mentees and mentors; this includes reflecting on the underlying motives for mentorship and cultivating gratitude for the relationships formed.6 While these steps may seem trivial, gratitude promotes happiness, trust, motivation, and respect. It can be felt by others, including mentees.

As mentors continue to shape the future, they have an ethical obligation to care for themselves, in addition to their mentees. In addition to avoiding mentorship malpractice, engaging in team mentorship, and incorporating mindful mentoring, an emphasis on self-care is critical.7 Taking time to recharge is essential. It allows one to be fully present, while also setting an example for the mentee. Explicitly addressing self-care for both mentor and mentee is a part of mindful mentorship, with benefits for all.6

Three key points:

1. Awareness of mentorship malpractice

2. Importance of team mentorship

3. Benefits of mindful mentorship

Mr. Rodoni is with the University of Michigan Medical School and Stephen M. Ross School of Business, Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Fessel is a professor of radiology in the department of radiology at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor. They reported having no disclosures relevant to this article.

References:

1. Chopra V et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Feb;178:175-6.

2. Chopra V et al. JAMA. 2016 Apr 12;315:1453-4.

3. Chopra V et al. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors & Mentees Succeed. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, 2019.

4. Rodoni BM et al. Annals of Surgery. 2020 Aug;272(2):e151-2.

5. Waljee JF et al. JAMA. 2018 Apr 17;319(15):1547-8.

6. Chopra V and Saint S. Healthc (Amst). 2020 Mar;8(1):100390.

7. Fessell D et al. “Mentoring During a Crisis.” Harvard Business Review. 2020 Oct 29.

Scenario

A GI faculty member is approached by two medical students who are planning careers in gastroenterology. They are interested in research projects and are very willing to dedicate the necessary time and energy. The faculty member is impressed by their desire and finds themselves recalling their own unsuccessful medical school search for a research mentor. Inspired by their enthusiasm and a desire to “give back,” the faculty member agrees to mentor them and helps them find suitable projects. Primarily because of the students’ hard work and fueled by their desire to produce results that will help their residency applications, the work progresses rapidly. Both students have separate abstracts accepted at a national meeting.

When COVID-19 hits, the faculty member is asked by their department to take on additional administrative and clinical work. They feel they cannot say no. Soon the faculty member finds it difficult to manage these new responsibilities on top of their many research projects, numerous clinical obligations, and additional pressures outside of work. They find they have no time for mentoring or even adequate sleep. Facing burnout, the faculty member is uncertain what to do for these hard-working and very gifted students. How would you recommend they manage their mentoring obligations?

Discussion

Mentorship is a cornerstone of academic medicine. In fact, it has been shown that academic clinicians who serve as mentors publish more papers, get more grants, are promoted faster, and are more likely to stay at their academic institutions with greater career satisfaction.1 However, not every mentor-mentee relationship is mutually beneficial. Usually, it’s the mentees that disproportionately suffer the consequences of a suboptimal relationship.2

Mentorship malpractice occurs when mentors’ behavior crosses a threshold that places the mentees’ success at risk.1,2 While the case above highlights a specific scenario where multiple issues are unfolding, the ability to recognize, address, and most importantly prevent mentorship malpractice ultimately benefits both mentees and mentors.

Understanding the various types of mentorship malpractice is helpful for prevention and course correction. As described by Chopra and colleagues, there are multiple types of passive and active mentorship malpractice.2 The passive forms are characterized by a lack of face-to-face meeting time with mentees and/or a lack of advocacy on the mentees’ behalf. Meanwhile, the active forms occur when the mentor exhibits self-serving behaviors. These can include listing themselves as first author on a mentee’s project or discouraging a mentee from working with other mentors. Mentors must be able to self-check, seek feedback from mentees, and encourage mentees to further their professional networks beyond the boundaries of what the mentor alone can offer. Doing so helps create new opportunities and helps ensure a mutually beneficial relationship.

A great initial step to prevent passive and active mentorship malpractice is to leverage the benefits of team mentorship.2,3 At its core, team mentorship capitalizes on the collective contributions of multiple mentors. Doing so not only provides security during uncertain times, but also allows for a diversity of perspectives, distribution of workload among mentors, and additional support for mentees.3,4 Team mentorship it is particularly important during this current global health crisis, and such an approach from the outset could have significantly improved the scenario above.

For the above scenario, likely a transition in mentorship would be needed. Such transitions, whether short term or long term, require transparency, honesty, and willingness to engage in difficult conversations with mentees. Whether the mentor in the above case engages another faculty to take on the mentees or chooses to find a colleague who will agree to take on other competing demands, it will require time, effort, and energy – all of which are in short supply. When team mentorship is established from the outset, such transitions of mentorship can occur seamlessly and with more ease for all.

Additional considerations for successful mentoring of medical students or early-career physicians include understanding generational differences between the mentor and their mentees. As outlined by Waljee and colleagues, the next generation of trainees and physicians may act in ways that deviate from the norms of academic medicine’s tradition. As a mentor, it is imperative to understand these actions are not intended to disrupt the traditions and norms of health systems.5 For example, the use of technology during rounds can often be misconstrued as disrespectful. However, the underlying intent in many cases is to answer a question or access a helpful reference.

Seeing behavior and actions from the perspective of the mentee is one of the many ways to support and sustain successful mentoring relationships. A mindful approach benefits both mentees and mentors; this includes reflecting on the underlying motives for mentorship and cultivating gratitude for the relationships formed.6 While these steps may seem trivial, gratitude promotes happiness, trust, motivation, and respect. It can be felt by others, including mentees.

As mentors continue to shape the future, they have an ethical obligation to care for themselves, in addition to their mentees. In addition to avoiding mentorship malpractice, engaging in team mentorship, and incorporating mindful mentoring, an emphasis on self-care is critical.7 Taking time to recharge is essential. It allows one to be fully present, while also setting an example for the mentee. Explicitly addressing self-care for both mentor and mentee is a part of mindful mentorship, with benefits for all.6

Three key points:

1. Awareness of mentorship malpractice

2. Importance of team mentorship

3. Benefits of mindful mentorship

Mr. Rodoni is with the University of Michigan Medical School and Stephen M. Ross School of Business, Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Fessel is a professor of radiology in the department of radiology at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor. They reported having no disclosures relevant to this article.

References:

1. Chopra V et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Feb;178:175-6.

2. Chopra V et al. JAMA. 2016 Apr 12;315:1453-4.

3. Chopra V et al. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors & Mentees Succeed. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, 2019.

4. Rodoni BM et al. Annals of Surgery. 2020 Aug;272(2):e151-2.

5. Waljee JF et al. JAMA. 2018 Apr 17;319(15):1547-8.

6. Chopra V and Saint S. Healthc (Amst). 2020 Mar;8(1):100390.

7. Fessell D et al. “Mentoring During a Crisis.” Harvard Business Review. 2020 Oct 29.

Scenario

A GI faculty member is approached by two medical students who are planning careers in gastroenterology. They are interested in research projects and are very willing to dedicate the necessary time and energy. The faculty member is impressed by their desire and finds themselves recalling their own unsuccessful medical school search for a research mentor. Inspired by their enthusiasm and a desire to “give back,” the faculty member agrees to mentor them and helps them find suitable projects. Primarily because of the students’ hard work and fueled by their desire to produce results that will help their residency applications, the work progresses rapidly. Both students have separate abstracts accepted at a national meeting.

When COVID-19 hits, the faculty member is asked by their department to take on additional administrative and clinical work. They feel they cannot say no. Soon the faculty member finds it difficult to manage these new responsibilities on top of their many research projects, numerous clinical obligations, and additional pressures outside of work. They find they have no time for mentoring or even adequate sleep. Facing burnout, the faculty member is uncertain what to do for these hard-working and very gifted students. How would you recommend they manage their mentoring obligations?

Discussion

Mentorship is a cornerstone of academic medicine. In fact, it has been shown that academic clinicians who serve as mentors publish more papers, get more grants, are promoted faster, and are more likely to stay at their academic institutions with greater career satisfaction.1 However, not every mentor-mentee relationship is mutually beneficial. Usually, it’s the mentees that disproportionately suffer the consequences of a suboptimal relationship.2

Mentorship malpractice occurs when mentors’ behavior crosses a threshold that places the mentees’ success at risk.1,2 While the case above highlights a specific scenario where multiple issues are unfolding, the ability to recognize, address, and most importantly prevent mentorship malpractice ultimately benefits both mentees and mentors.

Understanding the various types of mentorship malpractice is helpful for prevention and course correction. As described by Chopra and colleagues, there are multiple types of passive and active mentorship malpractice.2 The passive forms are characterized by a lack of face-to-face meeting time with mentees and/or a lack of advocacy on the mentees’ behalf. Meanwhile, the active forms occur when the mentor exhibits self-serving behaviors. These can include listing themselves as first author on a mentee’s project or discouraging a mentee from working with other mentors. Mentors must be able to self-check, seek feedback from mentees, and encourage mentees to further their professional networks beyond the boundaries of what the mentor alone can offer. Doing so helps create new opportunities and helps ensure a mutually beneficial relationship.

A great initial step to prevent passive and active mentorship malpractice is to leverage the benefits of team mentorship.2,3 At its core, team mentorship capitalizes on the collective contributions of multiple mentors. Doing so not only provides security during uncertain times, but also allows for a diversity of perspectives, distribution of workload among mentors, and additional support for mentees.3,4 Team mentorship it is particularly important during this current global health crisis, and such an approach from the outset could have significantly improved the scenario above.

For the above scenario, likely a transition in mentorship would be needed. Such transitions, whether short term or long term, require transparency, honesty, and willingness to engage in difficult conversations with mentees. Whether the mentor in the above case engages another faculty to take on the mentees or chooses to find a colleague who will agree to take on other competing demands, it will require time, effort, and energy – all of which are in short supply. When team mentorship is established from the outset, such transitions of mentorship can occur seamlessly and with more ease for all.

Additional considerations for successful mentoring of medical students or early-career physicians include understanding generational differences between the mentor and their mentees. As outlined by Waljee and colleagues, the next generation of trainees and physicians may act in ways that deviate from the norms of academic medicine’s tradition. As a mentor, it is imperative to understand these actions are not intended to disrupt the traditions and norms of health systems.5 For example, the use of technology during rounds can often be misconstrued as disrespectful. However, the underlying intent in many cases is to answer a question or access a helpful reference.

Seeing behavior and actions from the perspective of the mentee is one of the many ways to support and sustain successful mentoring relationships. A mindful approach benefits both mentees and mentors; this includes reflecting on the underlying motives for mentorship and cultivating gratitude for the relationships formed.6 While these steps may seem trivial, gratitude promotes happiness, trust, motivation, and respect. It can be felt by others, including mentees.

As mentors continue to shape the future, they have an ethical obligation to care for themselves, in addition to their mentees. In addition to avoiding mentorship malpractice, engaging in team mentorship, and incorporating mindful mentoring, an emphasis on self-care is critical.7 Taking time to recharge is essential. It allows one to be fully present, while also setting an example for the mentee. Explicitly addressing self-care for both mentor and mentee is a part of mindful mentorship, with benefits for all.6

Three key points:

1. Awareness of mentorship malpractice

2. Importance of team mentorship

3. Benefits of mindful mentorship

Mr. Rodoni is with the University of Michigan Medical School and Stephen M. Ross School of Business, Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Fessel is a professor of radiology in the department of radiology at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor. They reported having no disclosures relevant to this article.

References:

1. Chopra V et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Feb;178:175-6.

2. Chopra V et al. JAMA. 2016 Apr 12;315:1453-4.

3. Chopra V et al. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors & Mentees Succeed. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, 2019.

4. Rodoni BM et al. Annals of Surgery. 2020 Aug;272(2):e151-2.

5. Waljee JF et al. JAMA. 2018 Apr 17;319(15):1547-8.

6. Chopra V and Saint S. Healthc (Amst). 2020 Mar;8(1):100390.

7. Fessell D et al. “Mentoring During a Crisis.” Harvard Business Review. 2020 Oct 29.

Medical professional liability risk and mitigation: An overview for early-career gastroenterologists

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. All examples are hypothetical and aim to illustrate common clinical scenarios and challenges gastroenterologists may encounter within their scope of practice. The content herein should not be interpreted as legal advice for individual cases nor a substitute for seeking the advice of an attorney.

There are unique potential stressors faced by the gastroenterologist at each career stage, some more so early on. One such stressor, and one particularly important in a procedure-intensive specialty like GI, is medical professional liability (MPL), historically termed “medical malpractice.” Between 2009 and 2018, GI was the second-highest internal medicine subspecialty in both MPL claims made and claims paid,1 yet instruction on MPL risk and mitigation is scarce in fellowship, as is the available GI-related literature on the topic. This scarcity may generate untoward stress and unnecessarily expose gastroenterologists to avoidable MPL pitfalls. Therefore, it is vital for GI trainees, early-career gastroenterologists, and even seasoned gastroenterologists to have a working and updated knowledge of the general principles of MPL and GI-specific considerations. Such understanding can help preserve physician well-being, increase professional satisfaction, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and improve health care outcomes.2

To this end, we herein provide a focused review of the following: key MPL concepts, trends in MPL claims, GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations, adverse provider defensive mechanisms, documentation tenets, challenges posed by telemedicine, and the concept of “vicarious liability.”

Key MPL concepts

MPL falls under the umbrella of tort law, which itself falls under the umbrella of civil law; that is, civil (as opposed to criminal) justice governs torts – including but not limited to MPL claims – as well as other areas of law concerning noncriminal injury.3 A “tort” is a “civil wrong that unfairly causes another to experience loss or harm resulting in legal liability.”3 MPL claims assert the tort of negligence (similar to the concept of “incompetence”) and endeavor to compensate the harmed patient/individual while simultaneously dissuading suboptimal medical care by the provider in the future.4,5 A successful MPL claim must prove four overlapping elements: that the tortfeasor (here, the gastroenterologist) owed a duty of care to the injured party and breached that duty, which caused damages.6 Given that MPL cases exist within tort law rather than criminal law, the burden of proof for these cases is not “beyond a reasonable doubt”; instead, it’s “to a reasonable medical probability.”7

Trends in MPL claims

According to data compiled by the MPL Association, 278,220 MPL claims were made in the United States from 1985 to 2012.3,8-10 Among these, 1.8% involved gastroenterologists, which puts it at 17th place out of the 20 specialties surveyed.9 While the number of paid claims over this time frame decreased in GI by 34.6% (from 18.5 to 12.1 cases per 1,000 physician-years), there was a concurrent 23.3% increase in average claim compensation; essentially, there were fewer paid GI-related claims but there were higher payouts per paid claim.11,12 From 2009 to 2018, average legal defense costs for paid GI-related claims were $97,392, and average paid amount was $330,876.1

GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations

Many MPL claims relate to situations involving medical errors or adverse events (AEs), be they procedural or nonprocedural. However other aspects of GI also carry MPL risk.

Informed consent

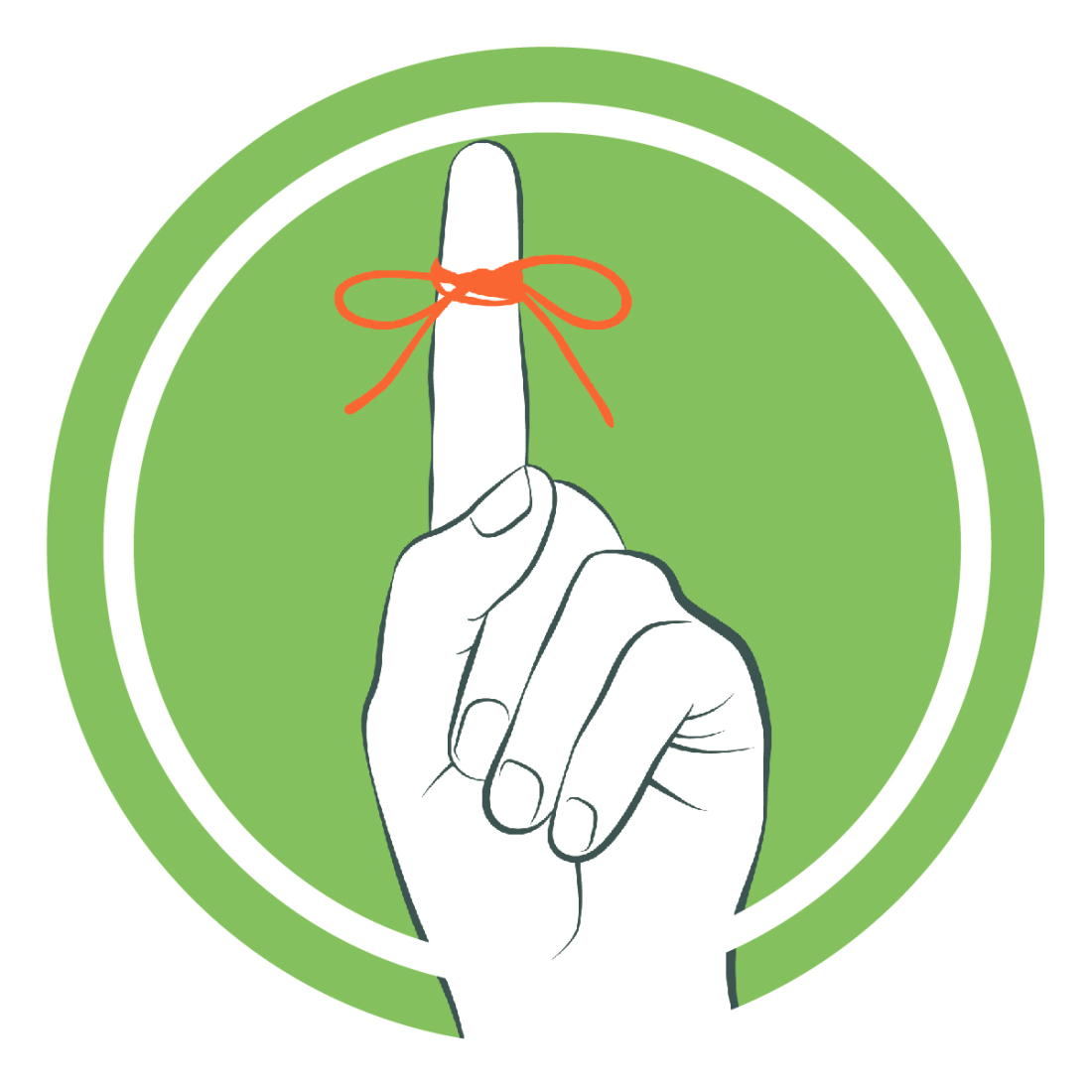

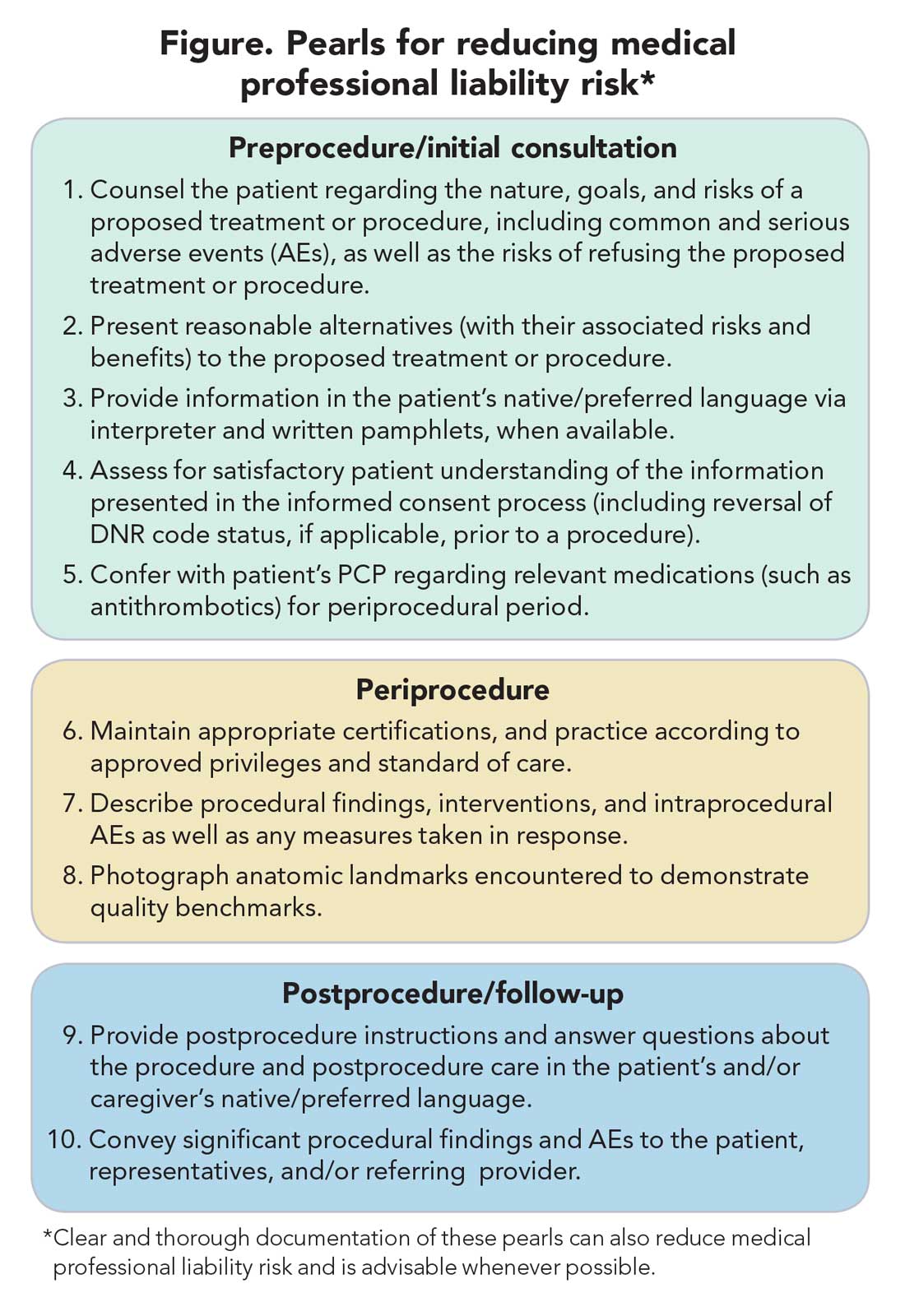

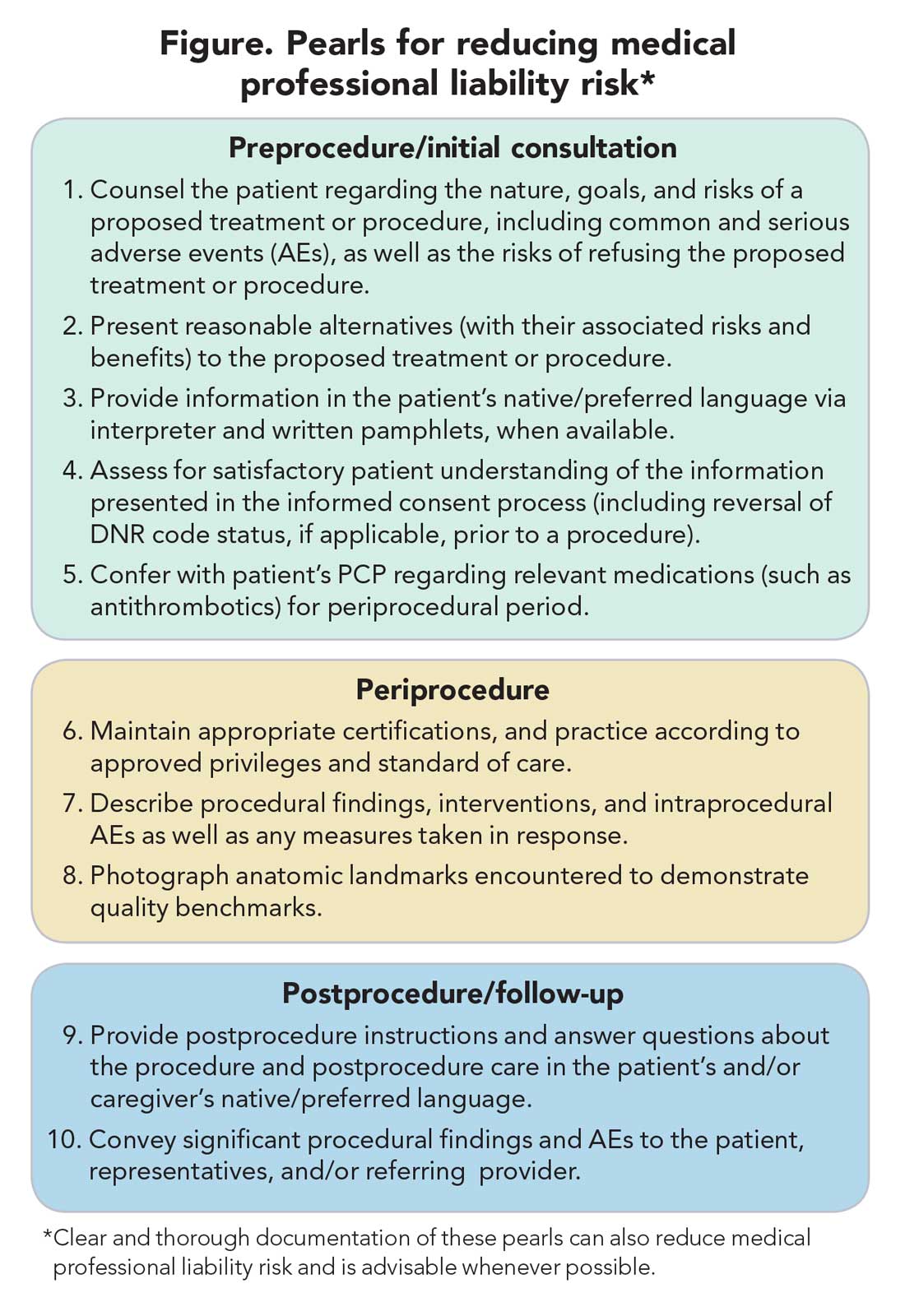

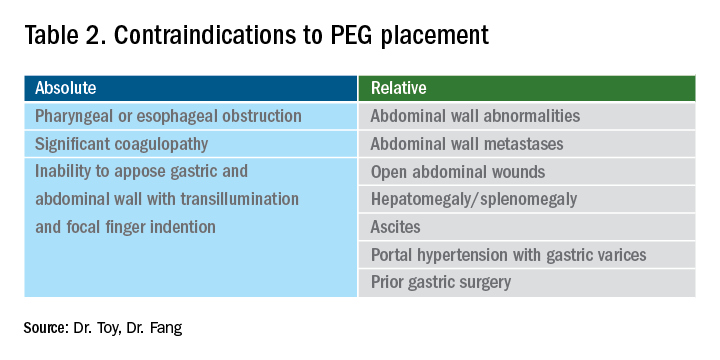

MPL claims may be made not only on the grounds of inadequately informed consent but also inadequately informed refusal.5,13,14 While standards for adequate informed consent vary by state, most states apply the “reasonable patient standard,” i.e., assuming an average patient with enough information to be an active participant in the medical decision-making process. Generally, informed consent should ensure that the patient understands the nature of the procedure/treatment being proposed, there is a discussion of the risks and benefits of undergoing and not undergoing the procedure/treatment, reasonable alternatives are presented, the risks and benefits associated with these alternatives are discussed, and the patient’s comprehension of these things is assessed (Figure).15 Additionally, informed consent should be tailored to each patient and GI procedure/treatment on a case-by-case basis rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, documentation of the patient’s understanding of the (tailored) information provided can concurrently improve quality of the consent and potentially decrease MPL risk (Figure).16

Endoscopic procedures

Procedure-related MPL claims represent approximately 25% of all GI-related claims (8,17). Among these, 52% involve colonoscopy, 16% involve endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and 11% involve esophagogastroduodenoscopy.8 Albeit generally safe, colonoscopy, as with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, is subject to rare but serious AEs.18,19 Risk of these AEs may be accentuated in certain scenarios (such as severe colonic inflammation or coagulopathy) and, as discussed earlier, may merit tailored informed consent. Regardless of the procedure, in the event of postprocedural development of signs/symptoms (such as tachycardia, fever, chest or abdominal discomfort, or hypotension) indicating a potential AE, stabilizing measures and evaluation (such as blood work and imaging) should be undertaken, and hospital admission (if not already hospitalized) should be considered until discharge is deemed safe.19

ERCP-related MPL claims, for many years, have had the highest average compensation of any GI procedure.11 Though discussion of advanced procedures is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning the observation that most of such claims involve an allegation that the procedure was not indicated (for example, that it was performed based on inadequate evidence of pancreatobiliary pathology), or was for diagnostic purposes (for example, being done instead of noninvasive imaging) rather than therapeutic.20-23 This emphasizes the importance of appropriate procedure indications.

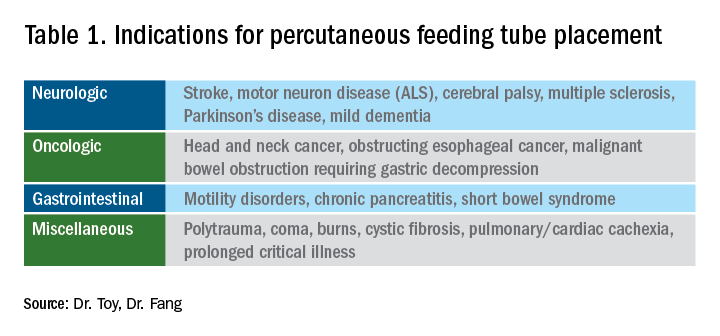

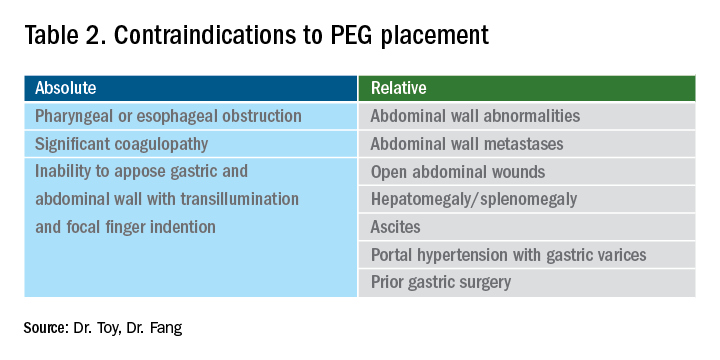

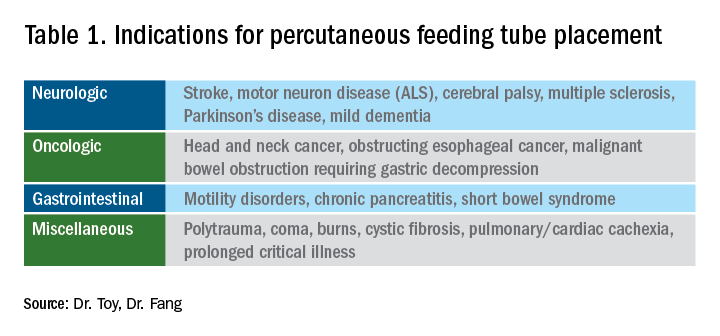

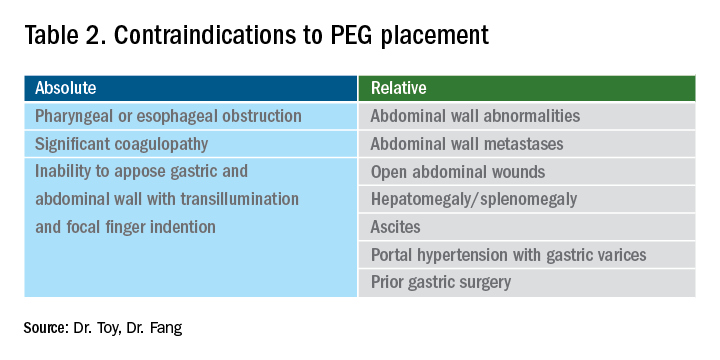

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement merits special mention given it can be complicated by ethical challenges (for example, needing a surrogate decision-maker’s consent or representing medical futility) and has a relatively high potential for MPL claims. PEG placement carries a low AE rate (0.1%-1%), but these AEs may result in high morbidity/mortality, in part because of the underlying comorbidities of patients needing PEG placement.24,25 Also, timing of a patient’s demise may coincide with PEG placement, thereby prompting (possibly unfounded) perceptions of causality.24-27 Therefore, such scenarios merit unique additional preprocedure safeguards. For instance, for patients lacking capacity to provide informed consent, especially when family members may differ on whether PEG should be placed, it is advisable to ask the family to select one surrogate decision-maker (if there’s no advance directive) to whom the gastroenterologist should discuss both the risks, benefits, and goals of PEG placement in the context of the patient’s overall clinical trajectory/life expectancy and the need for consent (or refusal) based on what the patient would have wished. In addition, having a medical professional witness this discussion may be useful.27

Antithrombotic agents

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics, including anticoagulants and antiplatelets, can pose challenges for the gastroenterologist. While clinical practice guidelines exist to guide decision-making in this regard, the variables involved may extend beyond the expertise of the gastroenterologist.28 For instance, in addition to the procedural risk for bleeding, the indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk of a thrombotic event, duration of action of the antithrombotic, and available bridging options should all be considered according to recommendations.28,29 While requiring more time on the part of the gastroenterologist, the optimal periprocedural management of antithrombotic agents would usually involve discussion with the provider managing antithrombotic therapy to best conduct a risk-benefit assessment regarding if (and how long) the antithrombotic therapy should be held (Figure). This shared decision-making, which should also include the patient, may help decrease MPL risk and improve outcomes.

Provider defense mechanisms

Physicians may engage in various defensive behaviors in an attempt to mitigate MPL risk; however, these behaviors may, paradoxically, increase risk.30,31

Assurance behaviors

Assurance behaviors refer to the practice of recommending or performing additional services (such as medications, imaging, procedures, and referrals) that are not clearly indicated.2,30,31 Assurance behaviors are driven by fear of MPL risk and/or missing a potential diagnosis. Recent studies have estimated that more than 50% of gastroenterologists worldwide have performed additional invasive procedures without clear indications, and that nearly one-third of endoscopic procedures annually have questionable indications.30,32 While assurance behaviors may seem likely to decrease MPL risk, overall, they may inadvertently increase AE and MPL risk, as well as health care expenditures.3,30,32

Avoidance behaviors

Avoidance behaviors refer to providers avoiding participation in potentially high-risk clinical interventions (for example, the actual procedures), including those for which they are credentialed/certified proficient.30,31 Two clinical scenarios that illustrate this behavior include the following: An advanced endoscopist credentialed to perform ERCP might refer a “high-risk” elderly patient with cholangitis to another provider to perform said ERCP or for percutaneous transhepatic drainage (in the absence of a clear benefit to such), or a gastroenterologist might refer a patient to interventional gastroenterology for resection of a large polyp even though gastroenterologists are usually proficient in this skill and may feel comfortable performing the resection themselves. Avoidance behaviors are driven by a fear of MPL risk and can have several negative consequences.33 For example, patients may not receive indicated interventions. Additionally, patients may have to wait longer for an intervention because they are referred to another provider, which also increases potential for loss to follow-up.2,30,31 This may be viewed as noncompliance with the standard of care, among other hazards, thereby increasing MPL risk.

Documentation tenets

Thorough documentation can decrease MPL risk, especially since it is often used as legal evidence.16 Documenting, for instance, preprocedure discussion of potential risk of AEs (such as bleeding or perforation) or procedural failure (for example, missed lesions)can protect gastroenterologists (Figure).16 While, as discussed previously, these should be covered in the informed consent process (which itself reduces MPL risk), proof of compliance in providing adequate informed consent must come in the form of documentation that indicates that the process took place and specifically what topics were discussed therein. MPL risk may be further decreased by documenting steps taken during a procedure and anatomic landmarks encountered to offer proof of technical competency and compliance with standards of care (Figure).16,34 In this context, it is worth recalling the adage: “If it’s not documented, it did not occur.”

Curbside consults versus consultation

Also germane here is the topic of whether documentation is needed for “curbside consults.” The uncertainty is, in part, semantic; that is, at what point does a “curbside” become a consultation? A curbside is a general question or query (such as anything that could also be answered by searching the Internet or reference materials) in response to which information is provided; once it involves provision of medical advice for a specific patient (for example, when patient identifiers have been shared or their EHR has been accessed), it constitutes a consultation. Based on these definitions, a curbside need not be documented, whereas a consultation – even if seemingly trivial – should be.

Consideration of language and cultural factors

Language barriers should be considered when the gastroenterologist is communicating with the patient, and such efforts, whenever made, should be documented to best protect against MPL.16,35 These considerations arise not only during the consent process but when obtaining a history, providing postprocedure instructions, and during follow-ups. To this end, 24/7 telephone interpreter services may assist the gastroenterologist (when one is communicating with non–English speakers and is not medically certified in the patient’s native/preferred language) and strengthen trust in the provider-patient relationship.36 Additionally, written materials (such as consent forms, procedural information) in patients’ native/preferred languages should be provided, when available, to enhance patient understanding and participation in care (Figure).35

Challenges posed by telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly led to more virtual encounters. While increased utilization of telemedicine platforms may make health care more accessible, it does not lessen the clinicians’ duty to patients and may actually expose them to greater MPL risk.18,37,38 Therefore, the provider must be cognizant of two key principles to mitigate MPL risk in the context of telemedicine encounters. First, the same standard of care applies to virtual and in-person encounters.18,37,38 Second, patient privacy and HIPAA regulations are not waived during telemedicine encounters, and breaches of such may result in an MPL claim.18,37,38

With regard to the first principle, for patients who have not been physically examined (such as when a telemedicine visit was substituted for an in-person clinic encounter), gastroenterologists should not overlook requesting timely preprocedure anesthesia consultation or obtaining additional laboratory studies as needed to ensure safety and the same standard of care. Moreover, particularly in the context of pandemic-related decreased procedural capacity, triaging procedures can be especially challenging. Standardized institutional criteria which prioritize certain diagnoses/conditions over others, leaving room for justifiable exceptions, are advisable.

Vicarious liability

“Vicarious liability” is defined as that extending to persons who have not committed a wrong but on whose behalf wrongdoers acted.39 Therefore, gastroenterologists may be liable not only for their own actions but also for those of personnel they supervise (such as fellow trainees and non–physician practitioners).39 Vicarious liability aims to ensure that systemic checks and balances are in place so that, if failure occurs, harm can still be mitigated and/or avoided, as illustrated by Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model.”40

Conclusion

Any gastroenterologist can experience an MPL claim. Such an experience can be especially stressful and confusing to early-career clinicians, especially if they’re unfamiliar with legal proceedings. Although MPL principles are not often taught in medical school or residency, it is important for gastroenterologists to be informed regarding tenets of MPL and cognizant of clinical situations which have relatively higher MPL risk. This can assuage untoward angst regarding MPL and highlight proactive risk-mitigation strategies. In general, gastroenterologist practices that can mitigate MPL risk include effective communication; adequate informed consent/refusal; documentation of preprocedure counseling, periprocedure events, and postprocedure recommendations; and maintenance of proper certification and privileging.

Dr. Azizian and Dr. Dalai are with the University of California, Los Angeles and the department of medicine at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center, Sylmar, Calif. They are co–first authors of this paper. Dr. Dalai is also with the division of gastroenterology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Adams is with the Center for Clinical Management Research in Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System, the division of gastroenterology at the University of Michigan Health System, and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, all in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Tabibian is with UCLA and the division of gastroenterology at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. 2020 Data Sharing Project Gastroenterology 2009-2018. Inside Medical Liability: Second Quarter. Accessed 2020 Dec 6.

2. Mello MM et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004 Jul-Aug;23(4):42-53.

3. Adams MA et al. JAMA. 2014 Oct;312(13):1348-9.

4. Pegalis SE. American Law of Medical Malpractice 3d, Vol. 2. St. Paul, Minn.: Thomson Reuters, 2005.

5. Feld LD et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;113(11):1577-9.

6. Sawyer v. Wight, 196 F. Supp. 2d 220, 226 (E.D.N.Y. 2002).

7. Michael A. Sita v. Long Island Jewish-Hillside Medical Center, 22 A.D.3d 743 (N.Y. App. Div. 2005).

8. Conklin LS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jun;6(6):677-81.

9. Jena AB et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 18;365(7):629-36.

10. Kane CK. “Policy Research Perspectives Medical Liability Claim Frequency: A 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians.” Chicago: American Medical Association, 2010.

11. Hernandez LV et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Apr 16;5(4):169-73.

12. Schaffer AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 May 1;177(5):710-8.

13. Natanson v. Kline, 186 Kan. 393, 409, 350 P.2d 1093, 1106, decision clarified on denial of reh’g, 187 Kan. 186, 354 P.2d 670 (1960).

14. Truman v. Thomas, 27 Cal. 3d 285, 292, 611 P.2d 902, 906 (1980).

15. Shah P et al. Informed Consent, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Aug 22.

16. Rex DK. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Jul;11(7):768-73.

17. Gerstenberger PD, Plumeri PA. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar-Apr 1993;39(2):132-8.

18. Adams MA and Allen JI. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Nov;17(12):2392-6.e1.

19. Ahlawat R et al. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Dec 9.

20. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Mar;63(3):378-82.

21. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):904.

22. Adamson TE et al. West J Med. 1989 Mar;150(3):356-60.

23. Trap R et al. Endoscopy. 1999 Feb;31(2):125-30.

24. Funaki B. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015 Mar;32(1):61-4.

25. Feeding Tube Nursing Home and Hospital Malpractice. Miller & Zois, Attorneys at Law. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

26. Medical Malpractice Lawsuit Brings $750,000 Settlement: Death of 82-year-old woman from sepsis due to improper placement of feeding tube. Lubin & Meyers PC. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

27. Brendel RW et al. Med Clin North Am. 2010 Nov;94(6):1229-40, xi-ii.

28. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Acosta RD et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jan;83(1):3-16.

29. Saleem S and Thomas AL. Cureus. 2018 Jun 25;10(6):e2878.

30. Hiyama T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec 21;12(47):7671-5.

31. Studdert DM et al. JAMA. 2005 Jun 1;293(21):2609-17.

32. Shaheen NJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May;154(7):1993-2003.

33. Oza VM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Feb;14(2):172-4.

34. Feld AD. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002 Jan;12(1):171-9, viii-ix.

35. Lee JS et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Aug;32(8):863-70.

36. Forrow L and Kontrimas JC. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Aug;32(8):855-7.

37. Moses RE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug;109(8):1128-32.

38. Tabibian JH. “The Evolution of Telehealth.” Guidepoint: Legal Solutions Blog. Accessed 2020 Aug 12.

39. Feld AD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;99(9):1641-4.

40. Reason J. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):768‐70.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. All examples are hypothetical and aim to illustrate common clinical scenarios and challenges gastroenterologists may encounter within their scope of practice. The content herein should not be interpreted as legal advice for individual cases nor a substitute for seeking the advice of an attorney.

There are unique potential stressors faced by the gastroenterologist at each career stage, some more so early on. One such stressor, and one particularly important in a procedure-intensive specialty like GI, is medical professional liability (MPL), historically termed “medical malpractice.” Between 2009 and 2018, GI was the second-highest internal medicine subspecialty in both MPL claims made and claims paid,1 yet instruction on MPL risk and mitigation is scarce in fellowship, as is the available GI-related literature on the topic. This scarcity may generate untoward stress and unnecessarily expose gastroenterologists to avoidable MPL pitfalls. Therefore, it is vital for GI trainees, early-career gastroenterologists, and even seasoned gastroenterologists to have a working and updated knowledge of the general principles of MPL and GI-specific considerations. Such understanding can help preserve physician well-being, increase professional satisfaction, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and improve health care outcomes.2

To this end, we herein provide a focused review of the following: key MPL concepts, trends in MPL claims, GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations, adverse provider defensive mechanisms, documentation tenets, challenges posed by telemedicine, and the concept of “vicarious liability.”

Key MPL concepts

MPL falls under the umbrella of tort law, which itself falls under the umbrella of civil law; that is, civil (as opposed to criminal) justice governs torts – including but not limited to MPL claims – as well as other areas of law concerning noncriminal injury.3 A “tort” is a “civil wrong that unfairly causes another to experience loss or harm resulting in legal liability.”3 MPL claims assert the tort of negligence (similar to the concept of “incompetence”) and endeavor to compensate the harmed patient/individual while simultaneously dissuading suboptimal medical care by the provider in the future.4,5 A successful MPL claim must prove four overlapping elements: that the tortfeasor (here, the gastroenterologist) owed a duty of care to the injured party and breached that duty, which caused damages.6 Given that MPL cases exist within tort law rather than criminal law, the burden of proof for these cases is not “beyond a reasonable doubt”; instead, it’s “to a reasonable medical probability.”7

Trends in MPL claims

According to data compiled by the MPL Association, 278,220 MPL claims were made in the United States from 1985 to 2012.3,8-10 Among these, 1.8% involved gastroenterologists, which puts it at 17th place out of the 20 specialties surveyed.9 While the number of paid claims over this time frame decreased in GI by 34.6% (from 18.5 to 12.1 cases per 1,000 physician-years), there was a concurrent 23.3% increase in average claim compensation; essentially, there were fewer paid GI-related claims but there were higher payouts per paid claim.11,12 From 2009 to 2018, average legal defense costs for paid GI-related claims were $97,392, and average paid amount was $330,876.1

GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations

Many MPL claims relate to situations involving medical errors or adverse events (AEs), be they procedural or nonprocedural. However other aspects of GI also carry MPL risk.

Informed consent

MPL claims may be made not only on the grounds of inadequately informed consent but also inadequately informed refusal.5,13,14 While standards for adequate informed consent vary by state, most states apply the “reasonable patient standard,” i.e., assuming an average patient with enough information to be an active participant in the medical decision-making process. Generally, informed consent should ensure that the patient understands the nature of the procedure/treatment being proposed, there is a discussion of the risks and benefits of undergoing and not undergoing the procedure/treatment, reasonable alternatives are presented, the risks and benefits associated with these alternatives are discussed, and the patient’s comprehension of these things is assessed (Figure).15 Additionally, informed consent should be tailored to each patient and GI procedure/treatment on a case-by-case basis rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, documentation of the patient’s understanding of the (tailored) information provided can concurrently improve quality of the consent and potentially decrease MPL risk (Figure).16

Endoscopic procedures

Procedure-related MPL claims represent approximately 25% of all GI-related claims (8,17). Among these, 52% involve colonoscopy, 16% involve endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and 11% involve esophagogastroduodenoscopy.8 Albeit generally safe, colonoscopy, as with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, is subject to rare but serious AEs.18,19 Risk of these AEs may be accentuated in certain scenarios (such as severe colonic inflammation or coagulopathy) and, as discussed earlier, may merit tailored informed consent. Regardless of the procedure, in the event of postprocedural development of signs/symptoms (such as tachycardia, fever, chest or abdominal discomfort, or hypotension) indicating a potential AE, stabilizing measures and evaluation (such as blood work and imaging) should be undertaken, and hospital admission (if not already hospitalized) should be considered until discharge is deemed safe.19

ERCP-related MPL claims, for many years, have had the highest average compensation of any GI procedure.11 Though discussion of advanced procedures is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning the observation that most of such claims involve an allegation that the procedure was not indicated (for example, that it was performed based on inadequate evidence of pancreatobiliary pathology), or was for diagnostic purposes (for example, being done instead of noninvasive imaging) rather than therapeutic.20-23 This emphasizes the importance of appropriate procedure indications.

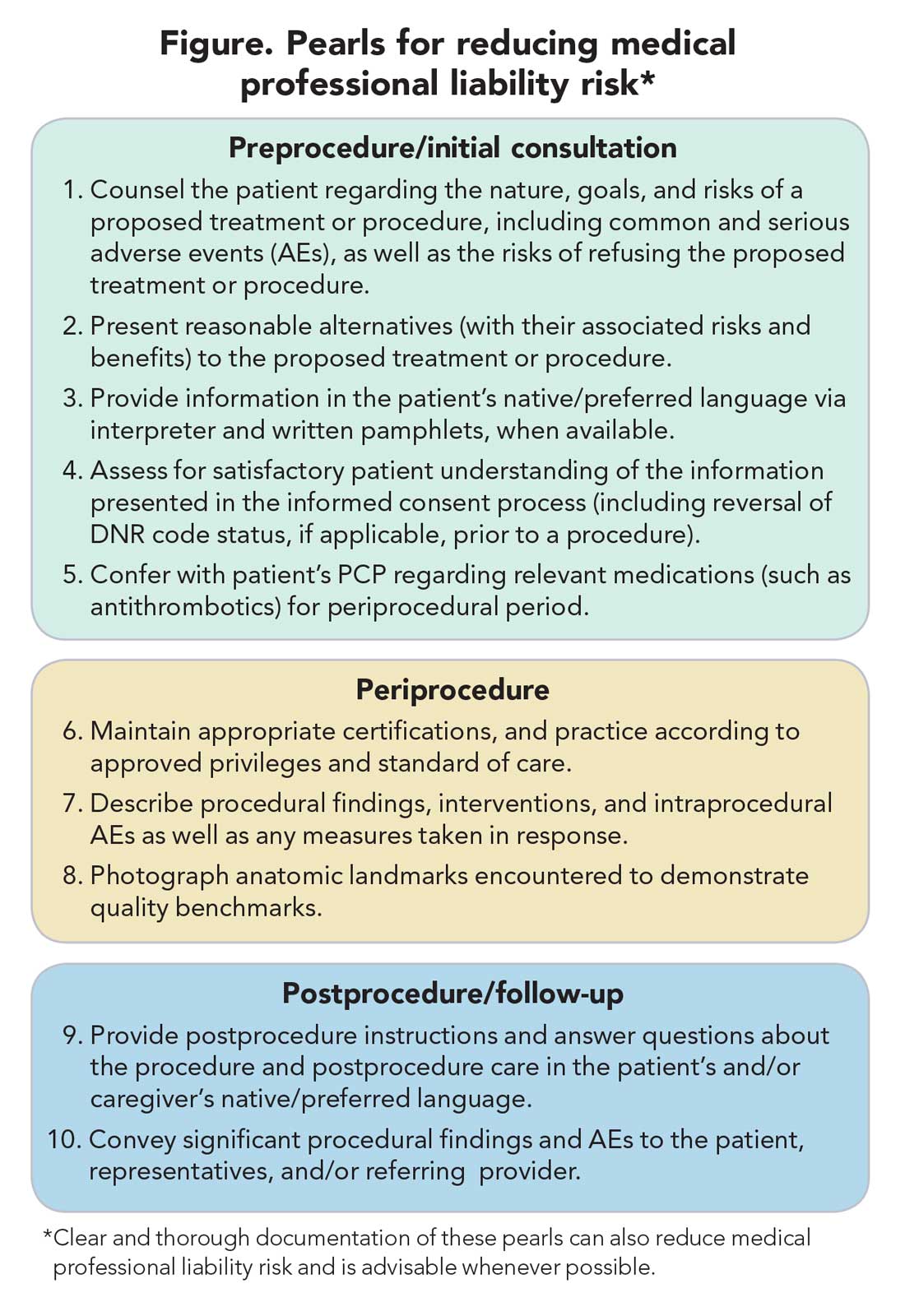

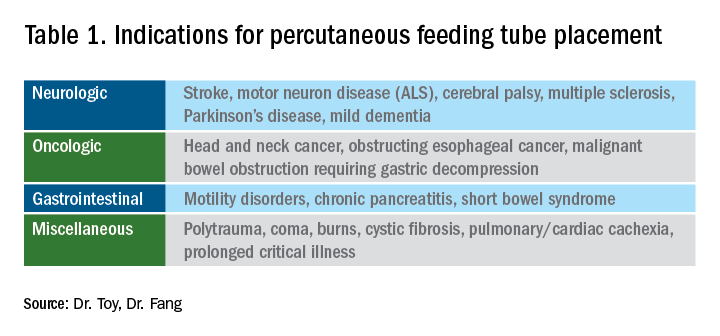

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement merits special mention given it can be complicated by ethical challenges (for example, needing a surrogate decision-maker’s consent or representing medical futility) and has a relatively high potential for MPL claims. PEG placement carries a low AE rate (0.1%-1%), but these AEs may result in high morbidity/mortality, in part because of the underlying comorbidities of patients needing PEG placement.24,25 Also, timing of a patient’s demise may coincide with PEG placement, thereby prompting (possibly unfounded) perceptions of causality.24-27 Therefore, such scenarios merit unique additional preprocedure safeguards. For instance, for patients lacking capacity to provide informed consent, especially when family members may differ on whether PEG should be placed, it is advisable to ask the family to select one surrogate decision-maker (if there’s no advance directive) to whom the gastroenterologist should discuss both the risks, benefits, and goals of PEG placement in the context of the patient’s overall clinical trajectory/life expectancy and the need for consent (or refusal) based on what the patient would have wished. In addition, having a medical professional witness this discussion may be useful.27

Antithrombotic agents

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics, including anticoagulants and antiplatelets, can pose challenges for the gastroenterologist. While clinical practice guidelines exist to guide decision-making in this regard, the variables involved may extend beyond the expertise of the gastroenterologist.28 For instance, in addition to the procedural risk for bleeding, the indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk of a thrombotic event, duration of action of the antithrombotic, and available bridging options should all be considered according to recommendations.28,29 While requiring more time on the part of the gastroenterologist, the optimal periprocedural management of antithrombotic agents would usually involve discussion with the provider managing antithrombotic therapy to best conduct a risk-benefit assessment regarding if (and how long) the antithrombotic therapy should be held (Figure). This shared decision-making, which should also include the patient, may help decrease MPL risk and improve outcomes.

Provider defense mechanisms

Physicians may engage in various defensive behaviors in an attempt to mitigate MPL risk; however, these behaviors may, paradoxically, increase risk.30,31

Assurance behaviors

Assurance behaviors refer to the practice of recommending or performing additional services (such as medications, imaging, procedures, and referrals) that are not clearly indicated.2,30,31 Assurance behaviors are driven by fear of MPL risk and/or missing a potential diagnosis. Recent studies have estimated that more than 50% of gastroenterologists worldwide have performed additional invasive procedures without clear indications, and that nearly one-third of endoscopic procedures annually have questionable indications.30,32 While assurance behaviors may seem likely to decrease MPL risk, overall, they may inadvertently increase AE and MPL risk, as well as health care expenditures.3,30,32

Avoidance behaviors

Avoidance behaviors refer to providers avoiding participation in potentially high-risk clinical interventions (for example, the actual procedures), including those for which they are credentialed/certified proficient.30,31 Two clinical scenarios that illustrate this behavior include the following: An advanced endoscopist credentialed to perform ERCP might refer a “high-risk” elderly patient with cholangitis to another provider to perform said ERCP or for percutaneous transhepatic drainage (in the absence of a clear benefit to such), or a gastroenterologist might refer a patient to interventional gastroenterology for resection of a large polyp even though gastroenterologists are usually proficient in this skill and may feel comfortable performing the resection themselves. Avoidance behaviors are driven by a fear of MPL risk and can have several negative consequences.33 For example, patients may not receive indicated interventions. Additionally, patients may have to wait longer for an intervention because they are referred to another provider, which also increases potential for loss to follow-up.2,30,31 This may be viewed as noncompliance with the standard of care, among other hazards, thereby increasing MPL risk.

Documentation tenets

Thorough documentation can decrease MPL risk, especially since it is often used as legal evidence.16 Documenting, for instance, preprocedure discussion of potential risk of AEs (such as bleeding or perforation) or procedural failure (for example, missed lesions)can protect gastroenterologists (Figure).16 While, as discussed previously, these should be covered in the informed consent process (which itself reduces MPL risk), proof of compliance in providing adequate informed consent must come in the form of documentation that indicates that the process took place and specifically what topics were discussed therein. MPL risk may be further decreased by documenting steps taken during a procedure and anatomic landmarks encountered to offer proof of technical competency and compliance with standards of care (Figure).16,34 In this context, it is worth recalling the adage: “If it’s not documented, it did not occur.”

Curbside consults versus consultation

Also germane here is the topic of whether documentation is needed for “curbside consults.” The uncertainty is, in part, semantic; that is, at what point does a “curbside” become a consultation? A curbside is a general question or query (such as anything that could also be answered by searching the Internet or reference materials) in response to which information is provided; once it involves provision of medical advice for a specific patient (for example, when patient identifiers have been shared or their EHR has been accessed), it constitutes a consultation. Based on these definitions, a curbside need not be documented, whereas a consultation – even if seemingly trivial – should be.

Consideration of language and cultural factors

Language barriers should be considered when the gastroenterologist is communicating with the patient, and such efforts, whenever made, should be documented to best protect against MPL.16,35 These considerations arise not only during the consent process but when obtaining a history, providing postprocedure instructions, and during follow-ups. To this end, 24/7 telephone interpreter services may assist the gastroenterologist (when one is communicating with non–English speakers and is not medically certified in the patient’s native/preferred language) and strengthen trust in the provider-patient relationship.36 Additionally, written materials (such as consent forms, procedural information) in patients’ native/preferred languages should be provided, when available, to enhance patient understanding and participation in care (Figure).35

Challenges posed by telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly led to more virtual encounters. While increased utilization of telemedicine platforms may make health care more accessible, it does not lessen the clinicians’ duty to patients and may actually expose them to greater MPL risk.18,37,38 Therefore, the provider must be cognizant of two key principles to mitigate MPL risk in the context of telemedicine encounters. First, the same standard of care applies to virtual and in-person encounters.18,37,38 Second, patient privacy and HIPAA regulations are not waived during telemedicine encounters, and breaches of such may result in an MPL claim.18,37,38

With regard to the first principle, for patients who have not been physically examined (such as when a telemedicine visit was substituted for an in-person clinic encounter), gastroenterologists should not overlook requesting timely preprocedure anesthesia consultation or obtaining additional laboratory studies as needed to ensure safety and the same standard of care. Moreover, particularly in the context of pandemic-related decreased procedural capacity, triaging procedures can be especially challenging. Standardized institutional criteria which prioritize certain diagnoses/conditions over others, leaving room for justifiable exceptions, are advisable.

Vicarious liability

“Vicarious liability” is defined as that extending to persons who have not committed a wrong but on whose behalf wrongdoers acted.39 Therefore, gastroenterologists may be liable not only for their own actions but also for those of personnel they supervise (such as fellow trainees and non–physician practitioners).39 Vicarious liability aims to ensure that systemic checks and balances are in place so that, if failure occurs, harm can still be mitigated and/or avoided, as illustrated by Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model.”40

Conclusion

Any gastroenterologist can experience an MPL claim. Such an experience can be especially stressful and confusing to early-career clinicians, especially if they’re unfamiliar with legal proceedings. Although MPL principles are not often taught in medical school or residency, it is important for gastroenterologists to be informed regarding tenets of MPL and cognizant of clinical situations which have relatively higher MPL risk. This can assuage untoward angst regarding MPL and highlight proactive risk-mitigation strategies. In general, gastroenterologist practices that can mitigate MPL risk include effective communication; adequate informed consent/refusal; documentation of preprocedure counseling, periprocedure events, and postprocedure recommendations; and maintenance of proper certification and privileging.

Dr. Azizian and Dr. Dalai are with the University of California, Los Angeles and the department of medicine at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center, Sylmar, Calif. They are co–first authors of this paper. Dr. Dalai is also with the division of gastroenterology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Adams is with the Center for Clinical Management Research in Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System, the division of gastroenterology at the University of Michigan Health System, and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, all in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Tabibian is with UCLA and the division of gastroenterology at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. 2020 Data Sharing Project Gastroenterology 2009-2018. Inside Medical Liability: Second Quarter. Accessed 2020 Dec 6.

2. Mello MM et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004 Jul-Aug;23(4):42-53.

3. Adams MA et al. JAMA. 2014 Oct;312(13):1348-9.

4. Pegalis SE. American Law of Medical Malpractice 3d, Vol. 2. St. Paul, Minn.: Thomson Reuters, 2005.

5. Feld LD et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;113(11):1577-9.

6. Sawyer v. Wight, 196 F. Supp. 2d 220, 226 (E.D.N.Y. 2002).

7. Michael A. Sita v. Long Island Jewish-Hillside Medical Center, 22 A.D.3d 743 (N.Y. App. Div. 2005).

8. Conklin LS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jun;6(6):677-81.

9. Jena AB et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 18;365(7):629-36.

10. Kane CK. “Policy Research Perspectives Medical Liability Claim Frequency: A 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians.” Chicago: American Medical Association, 2010.

11. Hernandez LV et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Apr 16;5(4):169-73.

12. Schaffer AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 May 1;177(5):710-8.

13. Natanson v. Kline, 186 Kan. 393, 409, 350 P.2d 1093, 1106, decision clarified on denial of reh’g, 187 Kan. 186, 354 P.2d 670 (1960).

14. Truman v. Thomas, 27 Cal. 3d 285, 292, 611 P.2d 902, 906 (1980).

15. Shah P et al. Informed Consent, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Aug 22.

16. Rex DK. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Jul;11(7):768-73.

17. Gerstenberger PD, Plumeri PA. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar-Apr 1993;39(2):132-8.

18. Adams MA and Allen JI. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Nov;17(12):2392-6.e1.

19. Ahlawat R et al. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Dec 9.

20. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Mar;63(3):378-82.

21. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):904.

22. Adamson TE et al. West J Med. 1989 Mar;150(3):356-60.

23. Trap R et al. Endoscopy. 1999 Feb;31(2):125-30.

24. Funaki B. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015 Mar;32(1):61-4.

25. Feeding Tube Nursing Home and Hospital Malpractice. Miller & Zois, Attorneys at Law. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

26. Medical Malpractice Lawsuit Brings $750,000 Settlement: Death of 82-year-old woman from sepsis due to improper placement of feeding tube. Lubin & Meyers PC. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

27. Brendel RW et al. Med Clin North Am. 2010 Nov;94(6):1229-40, xi-ii.

28. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Acosta RD et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jan;83(1):3-16.

29. Saleem S and Thomas AL. Cureus. 2018 Jun 25;10(6):e2878.

30. Hiyama T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec 21;12(47):7671-5.

31. Studdert DM et al. JAMA. 2005 Jun 1;293(21):2609-17.

32. Shaheen NJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May;154(7):1993-2003.

33. Oza VM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Feb;14(2):172-4.

34. Feld AD. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002 Jan;12(1):171-9, viii-ix.

35. Lee JS et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Aug;32(8):863-70.

36. Forrow L and Kontrimas JC. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Aug;32(8):855-7.

37. Moses RE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug;109(8):1128-32.

38. Tabibian JH. “The Evolution of Telehealth.” Guidepoint: Legal Solutions Blog. Accessed 2020 Aug 12.

39. Feld AD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;99(9):1641-4.

40. Reason J. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):768‐70.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. All examples are hypothetical and aim to illustrate common clinical scenarios and challenges gastroenterologists may encounter within their scope of practice. The content herein should not be interpreted as legal advice for individual cases nor a substitute for seeking the advice of an attorney.

There are unique potential stressors faced by the gastroenterologist at each career stage, some more so early on. One such stressor, and one particularly important in a procedure-intensive specialty like GI, is medical professional liability (MPL), historically termed “medical malpractice.” Between 2009 and 2018, GI was the second-highest internal medicine subspecialty in both MPL claims made and claims paid,1 yet instruction on MPL risk and mitigation is scarce in fellowship, as is the available GI-related literature on the topic. This scarcity may generate untoward stress and unnecessarily expose gastroenterologists to avoidable MPL pitfalls. Therefore, it is vital for GI trainees, early-career gastroenterologists, and even seasoned gastroenterologists to have a working and updated knowledge of the general principles of MPL and GI-specific considerations. Such understanding can help preserve physician well-being, increase professional satisfaction, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and improve health care outcomes.2

To this end, we herein provide a focused review of the following: key MPL concepts, trends in MPL claims, GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations, adverse provider defensive mechanisms, documentation tenets, challenges posed by telemedicine, and the concept of “vicarious liability.”

Key MPL concepts

MPL falls under the umbrella of tort law, which itself falls under the umbrella of civil law; that is, civil (as opposed to criminal) justice governs torts – including but not limited to MPL claims – as well as other areas of law concerning noncriminal injury.3 A “tort” is a “civil wrong that unfairly causes another to experience loss or harm resulting in legal liability.”3 MPL claims assert the tort of negligence (similar to the concept of “incompetence”) and endeavor to compensate the harmed patient/individual while simultaneously dissuading suboptimal medical care by the provider in the future.4,5 A successful MPL claim must prove four overlapping elements: that the tortfeasor (here, the gastroenterologist) owed a duty of care to the injured party and breached that duty, which caused damages.6 Given that MPL cases exist within tort law rather than criminal law, the burden of proof for these cases is not “beyond a reasonable doubt”; instead, it’s “to a reasonable medical probability.”7

Trends in MPL claims

According to data compiled by the MPL Association, 278,220 MPL claims were made in the United States from 1985 to 2012.3,8-10 Among these, 1.8% involved gastroenterologists, which puts it at 17th place out of the 20 specialties surveyed.9 While the number of paid claims over this time frame decreased in GI by 34.6% (from 18.5 to 12.1 cases per 1,000 physician-years), there was a concurrent 23.3% increase in average claim compensation; essentially, there were fewer paid GI-related claims but there were higher payouts per paid claim.11,12 From 2009 to 2018, average legal defense costs for paid GI-related claims were $97,392, and average paid amount was $330,876.1

GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations

Many MPL claims relate to situations involving medical errors or adverse events (AEs), be they procedural or nonprocedural. However other aspects of GI also carry MPL risk.

Informed consent

MPL claims may be made not only on the grounds of inadequately informed consent but also inadequately informed refusal.5,13,14 While standards for adequate informed consent vary by state, most states apply the “reasonable patient standard,” i.e., assuming an average patient with enough information to be an active participant in the medical decision-making process. Generally, informed consent should ensure that the patient understands the nature of the procedure/treatment being proposed, there is a discussion of the risks and benefits of undergoing and not undergoing the procedure/treatment, reasonable alternatives are presented, the risks and benefits associated with these alternatives are discussed, and the patient’s comprehension of these things is assessed (Figure).15 Additionally, informed consent should be tailored to each patient and GI procedure/treatment on a case-by-case basis rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, documentation of the patient’s understanding of the (tailored) information provided can concurrently improve quality of the consent and potentially decrease MPL risk (Figure).16

Endoscopic procedures

Procedure-related MPL claims represent approximately 25% of all GI-related claims (8,17). Among these, 52% involve colonoscopy, 16% involve endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and 11% involve esophagogastroduodenoscopy.8 Albeit generally safe, colonoscopy, as with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, is subject to rare but serious AEs.18,19 Risk of these AEs may be accentuated in certain scenarios (such as severe colonic inflammation or coagulopathy) and, as discussed earlier, may merit tailored informed consent. Regardless of the procedure, in the event of postprocedural development of signs/symptoms (such as tachycardia, fever, chest or abdominal discomfort, or hypotension) indicating a potential AE, stabilizing measures and evaluation (such as blood work and imaging) should be undertaken, and hospital admission (if not already hospitalized) should be considered until discharge is deemed safe.19

ERCP-related MPL claims, for many years, have had the highest average compensation of any GI procedure.11 Though discussion of advanced procedures is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning the observation that most of such claims involve an allegation that the procedure was not indicated (for example, that it was performed based on inadequate evidence of pancreatobiliary pathology), or was for diagnostic purposes (for example, being done instead of noninvasive imaging) rather than therapeutic.20-23 This emphasizes the importance of appropriate procedure indications.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement merits special mention given it can be complicated by ethical challenges (for example, needing a surrogate decision-maker’s consent or representing medical futility) and has a relatively high potential for MPL claims. PEG placement carries a low AE rate (0.1%-1%), but these AEs may result in high morbidity/mortality, in part because of the underlying comorbidities of patients needing PEG placement.24,25 Also, timing of a patient’s demise may coincide with PEG placement, thereby prompting (possibly unfounded) perceptions of causality.24-27 Therefore, such scenarios merit unique additional preprocedure safeguards. For instance, for patients lacking capacity to provide informed consent, especially when family members may differ on whether PEG should be placed, it is advisable to ask the family to select one surrogate decision-maker (if there’s no advance directive) to whom the gastroenterologist should discuss both the risks, benefits, and goals of PEG placement in the context of the patient’s overall clinical trajectory/life expectancy and the need for consent (or refusal) based on what the patient would have wished. In addition, having a medical professional witness this discussion may be useful.27

Antithrombotic agents

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics, including anticoagulants and antiplatelets, can pose challenges for the gastroenterologist. While clinical practice guidelines exist to guide decision-making in this regard, the variables involved may extend beyond the expertise of the gastroenterologist.28 For instance, in addition to the procedural risk for bleeding, the indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk of a thrombotic event, duration of action of the antithrombotic, and available bridging options should all be considered according to recommendations.28,29 While requiring more time on the part of the gastroenterologist, the optimal periprocedural management of antithrombotic agents would usually involve discussion with the provider managing antithrombotic therapy to best conduct a risk-benefit assessment regarding if (and how long) the antithrombotic therapy should be held (Figure). This shared decision-making, which should also include the patient, may help decrease MPL risk and improve outcomes.

Provider defense mechanisms

Physicians may engage in various defensive behaviors in an attempt to mitigate MPL risk; however, these behaviors may, paradoxically, increase risk.30,31

Assurance behaviors

Assurance behaviors refer to the practice of recommending or performing additional services (such as medications, imaging, procedures, and referrals) that are not clearly indicated.2,30,31 Assurance behaviors are driven by fear of MPL risk and/or missing a potential diagnosis. Recent studies have estimated that more than 50% of gastroenterologists worldwide have performed additional invasive procedures without clear indications, and that nearly one-third of endoscopic procedures annually have questionable indications.30,32 While assurance behaviors may seem likely to decrease MPL risk, overall, they may inadvertently increase AE and MPL risk, as well as health care expenditures.3,30,32

Avoidance behaviors

Avoidance behaviors refer to providers avoiding participation in potentially high-risk clinical interventions (for example, the actual procedures), including those for which they are credentialed/certified proficient.30,31 Two clinical scenarios that illustrate this behavior include the following: An advanced endoscopist credentialed to perform ERCP might refer a “high-risk” elderly patient with cholangitis to another provider to perform said ERCP or for percutaneous transhepatic drainage (in the absence of a clear benefit to such), or a gastroenterologist might refer a patient to interventional gastroenterology for resection of a large polyp even though gastroenterologists are usually proficient in this skill and may feel comfortable performing the resection themselves. Avoidance behaviors are driven by a fear of MPL risk and can have several negative consequences.33 For example, patients may not receive indicated interventions. Additionally, patients may have to wait longer for an intervention because they are referred to another provider, which also increases potential for loss to follow-up.2,30,31 This may be viewed as noncompliance with the standard of care, among other hazards, thereby increasing MPL risk.

Documentation tenets

Thorough documentation can decrease MPL risk, especially since it is often used as legal evidence.16 Documenting, for instance, preprocedure discussion of potential risk of AEs (such as bleeding or perforation) or procedural failure (for example, missed lesions)can protect gastroenterologists (Figure).16 While, as discussed previously, these should be covered in the informed consent process (which itself reduces MPL risk), proof of compliance in providing adequate informed consent must come in the form of documentation that indicates that the process took place and specifically what topics were discussed therein. MPL risk may be further decreased by documenting steps taken during a procedure and anatomic landmarks encountered to offer proof of technical competency and compliance with standards of care (Figure).16,34 In this context, it is worth recalling the adage: “If it’s not documented, it did not occur.”

Curbside consults versus consultation

Also germane here is the topic of whether documentation is needed for “curbside consults.” The uncertainty is, in part, semantic; that is, at what point does a “curbside” become a consultation? A curbside is a general question or query (such as anything that could also be answered by searching the Internet or reference materials) in response to which information is provided; once it involves provision of medical advice for a specific patient (for example, when patient identifiers have been shared or their EHR has been accessed), it constitutes a consultation. Based on these definitions, a curbside need not be documented, whereas a consultation – even if seemingly trivial – should be.

Consideration of language and cultural factors

Language barriers should be considered when the gastroenterologist is communicating with the patient, and such efforts, whenever made, should be documented to best protect against MPL.16,35 These considerations arise not only during the consent process but when obtaining a history, providing postprocedure instructions, and during follow-ups. To this end, 24/7 telephone interpreter services may assist the gastroenterologist (when one is communicating with non–English speakers and is not medically certified in the patient’s native/preferred language) and strengthen trust in the provider-patient relationship.36 Additionally, written materials (such as consent forms, procedural information) in patients’ native/preferred languages should be provided, when available, to enhance patient understanding and participation in care (Figure).35

Challenges posed by telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly led to more virtual encounters. While increased utilization of telemedicine platforms may make health care more accessible, it does not lessen the clinicians’ duty to patients and may actually expose them to greater MPL risk.18,37,38 Therefore, the provider must be cognizant of two key principles to mitigate MPL risk in the context of telemedicine encounters. First, the same standard of care applies to virtual and in-person encounters.18,37,38 Second, patient privacy and HIPAA regulations are not waived during telemedicine encounters, and breaches of such may result in an MPL claim.18,37,38

With regard to the first principle, for patients who have not been physically examined (such as when a telemedicine visit was substituted for an in-person clinic encounter), gastroenterologists should not overlook requesting timely preprocedure anesthesia consultation or obtaining additional laboratory studies as needed to ensure safety and the same standard of care. Moreover, particularly in the context of pandemic-related decreased procedural capacity, triaging procedures can be especially challenging. Standardized institutional criteria which prioritize certain diagnoses/conditions over others, leaving room for justifiable exceptions, are advisable.

Vicarious liability

“Vicarious liability” is defined as that extending to persons who have not committed a wrong but on whose behalf wrongdoers acted.39 Therefore, gastroenterologists may be liable not only for their own actions but also for those of personnel they supervise (such as fellow trainees and non–physician practitioners).39 Vicarious liability aims to ensure that systemic checks and balances are in place so that, if failure occurs, harm can still be mitigated and/or avoided, as illustrated by Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model.”40

Conclusion

Any gastroenterologist can experience an MPL claim. Such an experience can be especially stressful and confusing to early-career clinicians, especially if they’re unfamiliar with legal proceedings. Although MPL principles are not often taught in medical school or residency, it is important for gastroenterologists to be informed regarding tenets of MPL and cognizant of clinical situations which have relatively higher MPL risk. This can assuage untoward angst regarding MPL and highlight proactive risk-mitigation strategies. In general, gastroenterologist practices that can mitigate MPL risk include effective communication; adequate informed consent/refusal; documentation of preprocedure counseling, periprocedure events, and postprocedure recommendations; and maintenance of proper certification and privileging.

Dr. Azizian and Dr. Dalai are with the University of California, Los Angeles and the department of medicine at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center, Sylmar, Calif. They are co–first authors of this paper. Dr. Dalai is also with the division of gastroenterology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Adams is with the Center for Clinical Management Research in Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System, the division of gastroenterology at the University of Michigan Health System, and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, all in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Tabibian is with UCLA and the division of gastroenterology at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. 2020 Data Sharing Project Gastroenterology 2009-2018. Inside Medical Liability: Second Quarter. Accessed 2020 Dec 6.

2. Mello MM et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004 Jul-Aug;23(4):42-53.

3. Adams MA et al. JAMA. 2014 Oct;312(13):1348-9.

4. Pegalis SE. American Law of Medical Malpractice 3d, Vol. 2. St. Paul, Minn.: Thomson Reuters, 2005.

5. Feld LD et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;113(11):1577-9.

6. Sawyer v. Wight, 196 F. Supp. 2d 220, 226 (E.D.N.Y. 2002).

7. Michael A. Sita v. Long Island Jewish-Hillside Medical Center, 22 A.D.3d 743 (N.Y. App. Div. 2005).

8. Conklin LS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jun;6(6):677-81.

9. Jena AB et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 18;365(7):629-36.

10. Kane CK. “Policy Research Perspectives Medical Liability Claim Frequency: A 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians.” Chicago: American Medical Association, 2010.

11. Hernandez LV et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Apr 16;5(4):169-73.

12. Schaffer AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 May 1;177(5):710-8.

13. Natanson v. Kline, 186 Kan. 393, 409, 350 P.2d 1093, 1106, decision clarified on denial of reh’g, 187 Kan. 186, 354 P.2d 670 (1960).

14. Truman v. Thomas, 27 Cal. 3d 285, 292, 611 P.2d 902, 906 (1980).

15. Shah P et al. Informed Consent, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Aug 22.