User login

Making an impact beyond medicine

across all career stages and practice settings, highlight the diversity of our membership, and build a sense of community by learning more about one another.

As physicians, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to meaningfully impact the lives of our patients through the practice of clinical medicine, or by spearheading groundbreaking research that improves patient outcomes. However, some physicians arguably make their greatest mark outside of medicine.

To close out the inaugural year of our Member Spotlight feature, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Eric Esrailian, MD, MPH, chair of the division of gastroenterology at UCLA. He is an Emmy-nominated film producer and distinguished human rights advocate. His story is inspirational, and poignantly highlights how one’s impact as a physician can extend far beyond the walls of the hospital. We hope to continue to feature exceptional individuals like Dr. Esrailian who leverage their unique talents for societal good. We appreciate your continued nominations as we plan our 2024 coverage.

Also in the December issue, we summarize the results of a pivotal, head-to-head trial of risankizumab (Skyrizi) and ustekinumab (Stelara) for Crohn’s disease, which was presented in October at United European Gastroenterology (UEG) Week in Copenhagen.

We also highlight the FDA’s recent approval of vonoprazan, a new pharmacologic treatment for erosive esophagitis expected to be available in the U.S. sometime this month. Finally, Dr. Lauren Feld explains how gastroenterologists can advocate for more robust parental leave and return to work policies at their institutions and why it matters.

We wish you all a wonderful holiday season and look forward to seeing you again in the New Year.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

across all career stages and practice settings, highlight the diversity of our membership, and build a sense of community by learning more about one another.

As physicians, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to meaningfully impact the lives of our patients through the practice of clinical medicine, or by spearheading groundbreaking research that improves patient outcomes. However, some physicians arguably make their greatest mark outside of medicine.

To close out the inaugural year of our Member Spotlight feature, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Eric Esrailian, MD, MPH, chair of the division of gastroenterology at UCLA. He is an Emmy-nominated film producer and distinguished human rights advocate. His story is inspirational, and poignantly highlights how one’s impact as a physician can extend far beyond the walls of the hospital. We hope to continue to feature exceptional individuals like Dr. Esrailian who leverage their unique talents for societal good. We appreciate your continued nominations as we plan our 2024 coverage.

Also in the December issue, we summarize the results of a pivotal, head-to-head trial of risankizumab (Skyrizi) and ustekinumab (Stelara) for Crohn’s disease, which was presented in October at United European Gastroenterology (UEG) Week in Copenhagen.

We also highlight the FDA’s recent approval of vonoprazan, a new pharmacologic treatment for erosive esophagitis expected to be available in the U.S. sometime this month. Finally, Dr. Lauren Feld explains how gastroenterologists can advocate for more robust parental leave and return to work policies at their institutions and why it matters.

We wish you all a wonderful holiday season and look forward to seeing you again in the New Year.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

across all career stages and practice settings, highlight the diversity of our membership, and build a sense of community by learning more about one another.

As physicians, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to meaningfully impact the lives of our patients through the practice of clinical medicine, or by spearheading groundbreaking research that improves patient outcomes. However, some physicians arguably make their greatest mark outside of medicine.

To close out the inaugural year of our Member Spotlight feature, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Eric Esrailian, MD, MPH, chair of the division of gastroenterology at UCLA. He is an Emmy-nominated film producer and distinguished human rights advocate. His story is inspirational, and poignantly highlights how one’s impact as a physician can extend far beyond the walls of the hospital. We hope to continue to feature exceptional individuals like Dr. Esrailian who leverage their unique talents for societal good. We appreciate your continued nominations as we plan our 2024 coverage.

Also in the December issue, we summarize the results of a pivotal, head-to-head trial of risankizumab (Skyrizi) and ustekinumab (Stelara) for Crohn’s disease, which was presented in October at United European Gastroenterology (UEG) Week in Copenhagen.

We also highlight the FDA’s recent approval of vonoprazan, a new pharmacologic treatment for erosive esophagitis expected to be available in the U.S. sometime this month. Finally, Dr. Lauren Feld explains how gastroenterologists can advocate for more robust parental leave and return to work policies at their institutions and why it matters.

We wish you all a wonderful holiday season and look forward to seeing you again in the New Year.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Addressing supply-demand mismatch in GI

Impacts of this supply-demand mismatch are felt daily in our GI practices as we strive to expand access in our clinics and endoscopy suites, particularly in rural and urban underserved communities. In gastroenterology, increased demand for care has been driven by a perfect storm of population growth, increased patient awareness of GI health, and rising incidence of digestive diseases.

Between 2019 and 2034, the U.S. population is expected to grow by 10.6%, while the population aged 65 and older expands by over 42%. Recent increases in the CRC screening–eligible population also have contributed to unprecedented demand for GI care. Furthermore, care delivery has become more complex and time-consuming with the evolution of personalized medicine and high prevalence of comorbid conditions. At the same time, we are faced with a dwindling supply of gastroenterology providers. In 2021, there were 15,678 practicing gastroenterologists in the U.S., over half of whom were 55 years or older. This translates to 1 gastroenterologist per 20,830 people captured in the U.S. Census.

Addressing this striking supply-demand mismatch in GI requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses its complex drivers. First and foremost, we must expand the number of GI fellowship training slots to boost our pipeline. There are approximately 1,840 GI fellows currently in training, a third of whom enter the workforce each year. While the number of GI fellowship slots in the GI fellowship match has slowly increased over time (from 525 available slots across 199 programs in 2019 to 657 slots across 230 programs in 2023), this incremental growth is dwarfed by overall need. Continued advocacy for increased funding to support expansion of training slots is necessary to further move the needle – such lobbying recently led to the addition of 1,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education positions across specialties over a 5-year period starting in 2020, illustrating that change is possible. At the same time, we must address the factors that are causing gastroenterologists to leave the workforce prematurely through early retirement or part-time work by investing in innovative solutions to address burnout, reduce administrative burdens, enhance the efficiency of care delivery, and maintain financial viability. By investing in our physician workforce and its sustainability, we can ensure that our profession is better prepared to meet the needs of our growing and increasingly complex patient population now and in the future.

We hope you enjoy the November issue of GI & Hepatology News and have a wonderful Thanksgiving.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Impacts of this supply-demand mismatch are felt daily in our GI practices as we strive to expand access in our clinics and endoscopy suites, particularly in rural and urban underserved communities. In gastroenterology, increased demand for care has been driven by a perfect storm of population growth, increased patient awareness of GI health, and rising incidence of digestive diseases.

Between 2019 and 2034, the U.S. population is expected to grow by 10.6%, while the population aged 65 and older expands by over 42%. Recent increases in the CRC screening–eligible population also have contributed to unprecedented demand for GI care. Furthermore, care delivery has become more complex and time-consuming with the evolution of personalized medicine and high prevalence of comorbid conditions. At the same time, we are faced with a dwindling supply of gastroenterology providers. In 2021, there were 15,678 practicing gastroenterologists in the U.S., over half of whom were 55 years or older. This translates to 1 gastroenterologist per 20,830 people captured in the U.S. Census.

Addressing this striking supply-demand mismatch in GI requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses its complex drivers. First and foremost, we must expand the number of GI fellowship training slots to boost our pipeline. There are approximately 1,840 GI fellows currently in training, a third of whom enter the workforce each year. While the number of GI fellowship slots in the GI fellowship match has slowly increased over time (from 525 available slots across 199 programs in 2019 to 657 slots across 230 programs in 2023), this incremental growth is dwarfed by overall need. Continued advocacy for increased funding to support expansion of training slots is necessary to further move the needle – such lobbying recently led to the addition of 1,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education positions across specialties over a 5-year period starting in 2020, illustrating that change is possible. At the same time, we must address the factors that are causing gastroenterologists to leave the workforce prematurely through early retirement or part-time work by investing in innovative solutions to address burnout, reduce administrative burdens, enhance the efficiency of care delivery, and maintain financial viability. By investing in our physician workforce and its sustainability, we can ensure that our profession is better prepared to meet the needs of our growing and increasingly complex patient population now and in the future.

We hope you enjoy the November issue of GI & Hepatology News and have a wonderful Thanksgiving.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Impacts of this supply-demand mismatch are felt daily in our GI practices as we strive to expand access in our clinics and endoscopy suites, particularly in rural and urban underserved communities. In gastroenterology, increased demand for care has been driven by a perfect storm of population growth, increased patient awareness of GI health, and rising incidence of digestive diseases.

Between 2019 and 2034, the U.S. population is expected to grow by 10.6%, while the population aged 65 and older expands by over 42%. Recent increases in the CRC screening–eligible population also have contributed to unprecedented demand for GI care. Furthermore, care delivery has become more complex and time-consuming with the evolution of personalized medicine and high prevalence of comorbid conditions. At the same time, we are faced with a dwindling supply of gastroenterology providers. In 2021, there were 15,678 practicing gastroenterologists in the U.S., over half of whom were 55 years or older. This translates to 1 gastroenterologist per 20,830 people captured in the U.S. Census.

Addressing this striking supply-demand mismatch in GI requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses its complex drivers. First and foremost, we must expand the number of GI fellowship training slots to boost our pipeline. There are approximately 1,840 GI fellows currently in training, a third of whom enter the workforce each year. While the number of GI fellowship slots in the GI fellowship match has slowly increased over time (from 525 available slots across 199 programs in 2019 to 657 slots across 230 programs in 2023), this incremental growth is dwarfed by overall need. Continued advocacy for increased funding to support expansion of training slots is necessary to further move the needle – such lobbying recently led to the addition of 1,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education positions across specialties over a 5-year period starting in 2020, illustrating that change is possible. At the same time, we must address the factors that are causing gastroenterologists to leave the workforce prematurely through early retirement or part-time work by investing in innovative solutions to address burnout, reduce administrative burdens, enhance the efficiency of care delivery, and maintain financial viability. By investing in our physician workforce and its sustainability, we can ensure that our profession is better prepared to meet the needs of our growing and increasingly complex patient population now and in the future.

We hope you enjoy the November issue of GI & Hepatology News and have a wonderful Thanksgiving.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Enhancing CRC awareness and screening uptake

Each March, we celebrate National Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month to raise awareness of this common, deadly, and preventable form of cancer and advocate for increased screening uptake and investment in related research. Enhancing awareness is particularly important for those estimated 20 million average-risk individuals between the ages of 45 and 49 who became newly eligible for screening under the revised 2021 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force CRC screening guidelines, given alarming increases in early-onset CRC incidence. But as we know, awareness of CRC and screening eligibility alone is not enough to improve outcomes without addressing the many other patient, provider, and system-level barriers to screening uptake. Indeed, even before health care delivery disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, CRC screening was underutilized, and inequities in screening uptake and downstream outcomes existed.

While there is not space here for a full discussion of these important topics, I refer you to our Gastroenterology Data Trends 2022 supplement (https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/aga_data_trends_2022_web.pdf), which includes two excellent articles by Dr. Rachel Issaka of the University of Washington (“The Impact of COVID-19 on Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs”) and Dr. Aasma Shaukat of NYU (“Early Onset Colorectal Cancer: Trends in Incidence and Screening”).

In our March issue, we highlight the AGA’s decade-long advocacy efforts to close the “colonoscopy loophole” and reduce financial barriers to colorectal cancer screening. From AGA’s flagship journals, we report on the first Delphi-based consensus recommendations on early-onset colorectal cancer and highlight a study out of Italy comparing two computer-aided optical diagnosis systems for detection of small, leave-in-situ colon polyps. In our March Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Christina Tennyson, MD, who shares the rewards and challenges of practicing gastroenterology in a rural area and explains how she incorporates “lifestyle medicine” into her clinical practice. Finally, GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Avi Ketwaroo introduces our quarterly Perspectives column on endoscopic innovation in management of GI perforation and acute cholecystitis.

We hope you enjoy these stories and all the exciting content featured in our March issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Each March, we celebrate National Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month to raise awareness of this common, deadly, and preventable form of cancer and advocate for increased screening uptake and investment in related research. Enhancing awareness is particularly important for those estimated 20 million average-risk individuals between the ages of 45 and 49 who became newly eligible for screening under the revised 2021 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force CRC screening guidelines, given alarming increases in early-onset CRC incidence. But as we know, awareness of CRC and screening eligibility alone is not enough to improve outcomes without addressing the many other patient, provider, and system-level barriers to screening uptake. Indeed, even before health care delivery disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, CRC screening was underutilized, and inequities in screening uptake and downstream outcomes existed.

While there is not space here for a full discussion of these important topics, I refer you to our Gastroenterology Data Trends 2022 supplement (https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/aga_data_trends_2022_web.pdf), which includes two excellent articles by Dr. Rachel Issaka of the University of Washington (“The Impact of COVID-19 on Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs”) and Dr. Aasma Shaukat of NYU (“Early Onset Colorectal Cancer: Trends in Incidence and Screening”).

In our March issue, we highlight the AGA’s decade-long advocacy efforts to close the “colonoscopy loophole” and reduce financial barriers to colorectal cancer screening. From AGA’s flagship journals, we report on the first Delphi-based consensus recommendations on early-onset colorectal cancer and highlight a study out of Italy comparing two computer-aided optical diagnosis systems for detection of small, leave-in-situ colon polyps. In our March Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Christina Tennyson, MD, who shares the rewards and challenges of practicing gastroenterology in a rural area and explains how she incorporates “lifestyle medicine” into her clinical practice. Finally, GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Avi Ketwaroo introduces our quarterly Perspectives column on endoscopic innovation in management of GI perforation and acute cholecystitis.

We hope you enjoy these stories and all the exciting content featured in our March issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Each March, we celebrate National Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month to raise awareness of this common, deadly, and preventable form of cancer and advocate for increased screening uptake and investment in related research. Enhancing awareness is particularly important for those estimated 20 million average-risk individuals between the ages of 45 and 49 who became newly eligible for screening under the revised 2021 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force CRC screening guidelines, given alarming increases in early-onset CRC incidence. But as we know, awareness of CRC and screening eligibility alone is not enough to improve outcomes without addressing the many other patient, provider, and system-level barriers to screening uptake. Indeed, even before health care delivery disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, CRC screening was underutilized, and inequities in screening uptake and downstream outcomes existed.

While there is not space here for a full discussion of these important topics, I refer you to our Gastroenterology Data Trends 2022 supplement (https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/aga_data_trends_2022_web.pdf), which includes two excellent articles by Dr. Rachel Issaka of the University of Washington (“The Impact of COVID-19 on Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs”) and Dr. Aasma Shaukat of NYU (“Early Onset Colorectal Cancer: Trends in Incidence and Screening”).

In our March issue, we highlight the AGA’s decade-long advocacy efforts to close the “colonoscopy loophole” and reduce financial barriers to colorectal cancer screening. From AGA’s flagship journals, we report on the first Delphi-based consensus recommendations on early-onset colorectal cancer and highlight a study out of Italy comparing two computer-aided optical diagnosis systems for detection of small, leave-in-situ colon polyps. In our March Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Christina Tennyson, MD, who shares the rewards and challenges of practicing gastroenterology in a rural area and explains how she incorporates “lifestyle medicine” into her clinical practice. Finally, GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Avi Ketwaroo introduces our quarterly Perspectives column on endoscopic innovation in management of GI perforation and acute cholecystitis.

We hope you enjoy these stories and all the exciting content featured in our March issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Investing in GI innovation

Innovations in biomedical technology – from modern endoscopic devices and techniques to harnessing the microbiome to prevent and treat disease – have fundamentally changed the way in which we practice medicine and significantly improved the lives of our patients. In our February issue, we are pleased to highlight the launch of AGA’s GI Opportunity Fund, a new investment vehicle that provides AGA members and others a direct pathway to support development of promising, early-stage innovations by funding carefully vetted, cutting-edge start-up companies. We hope you will enjoy learning more about this exciting new initiative, which recently made its first major investment.

I want to thank GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Janice Jou for agreeing to spearhead this new column as its section editor – again, we invite you to nominate your colleagues, mentees, and others to be featured in future Member Spotlight columns.

We also highlight several recent papers published in AGA’s flagship journals, including a study assessing clinical outcomes and adverse events in patients receiving oral vs. colonic fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) for recurrent C. difficile infection, and another evaluating the cost-effectiveness of earlier colorectal cancer screening in patients with obesity. On the policy front, we summarize GI-relevant portions of the $1.7 trillion FY 2023 Omnibus Appropriations bill, signed into law on Dec. 30, 2022, by President Biden, and assess its impact on Medicare payments, continuation of support for telehealth/virtual care, and NIH-funding. We hope you enjoy reading these and other articles presented in our February issue.

Don’t forget to register for DDW 2023, May 6-9, 2023, in Chicago – general registration is now open!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Innovations in biomedical technology – from modern endoscopic devices and techniques to harnessing the microbiome to prevent and treat disease – have fundamentally changed the way in which we practice medicine and significantly improved the lives of our patients. In our February issue, we are pleased to highlight the launch of AGA’s GI Opportunity Fund, a new investment vehicle that provides AGA members and others a direct pathway to support development of promising, early-stage innovations by funding carefully vetted, cutting-edge start-up companies. We hope you will enjoy learning more about this exciting new initiative, which recently made its first major investment.

I want to thank GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Janice Jou for agreeing to spearhead this new column as its section editor – again, we invite you to nominate your colleagues, mentees, and others to be featured in future Member Spotlight columns.

We also highlight several recent papers published in AGA’s flagship journals, including a study assessing clinical outcomes and adverse events in patients receiving oral vs. colonic fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) for recurrent C. difficile infection, and another evaluating the cost-effectiveness of earlier colorectal cancer screening in patients with obesity. On the policy front, we summarize GI-relevant portions of the $1.7 trillion FY 2023 Omnibus Appropriations bill, signed into law on Dec. 30, 2022, by President Biden, and assess its impact on Medicare payments, continuation of support for telehealth/virtual care, and NIH-funding. We hope you enjoy reading these and other articles presented in our February issue.

Don’t forget to register for DDW 2023, May 6-9, 2023, in Chicago – general registration is now open!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Innovations in biomedical technology – from modern endoscopic devices and techniques to harnessing the microbiome to prevent and treat disease – have fundamentally changed the way in which we practice medicine and significantly improved the lives of our patients. In our February issue, we are pleased to highlight the launch of AGA’s GI Opportunity Fund, a new investment vehicle that provides AGA members and others a direct pathway to support development of promising, early-stage innovations by funding carefully vetted, cutting-edge start-up companies. We hope you will enjoy learning more about this exciting new initiative, which recently made its first major investment.

I want to thank GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Janice Jou for agreeing to spearhead this new column as its section editor – again, we invite you to nominate your colleagues, mentees, and others to be featured in future Member Spotlight columns.

We also highlight several recent papers published in AGA’s flagship journals, including a study assessing clinical outcomes and adverse events in patients receiving oral vs. colonic fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) for recurrent C. difficile infection, and another evaluating the cost-effectiveness of earlier colorectal cancer screening in patients with obesity. On the policy front, we summarize GI-relevant portions of the $1.7 trillion FY 2023 Omnibus Appropriations bill, signed into law on Dec. 30, 2022, by President Biden, and assess its impact on Medicare payments, continuation of support for telehealth/virtual care, and NIH-funding. We hope you enjoy reading these and other articles presented in our February issue.

Don’t forget to register for DDW 2023, May 6-9, 2023, in Chicago – general registration is now open!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

From the editor: Building community - Introducing Member Spotlight

Happy New Year, everyone! In early December, I attended the 2022 AGA Women’s Leadership Collaboration Conference to discuss strategies to promote gender equity in our profession. It was an inspiring weekend and reminded me how many talented individuals we have in the field of gastroenterology, all with fascinating personal and professional stories and much to contribute. I think I speak for all attendees in saying that it was a privilege to have the opportunity to interact with this amazing group of women leaders, reflect on our shared experiences and visions for the future of GI, and expand our networks.

This month we are excited to launch a new recurring feature in the newspaper and online – the Member Spotlight column. AGA has more than16,000 members from varied backgrounds. Yet the reality is that each of our individual networks is much smaller, and we would all benefit from learning more about one other and building a greater sense of community. To that end, starting with this issue, we will feature a different AGA member each month in our Member Spotlight column. The goal of this new feature is to recognize AGA members’ accomplishments across all career stages and practice settings, to highlight the diversity of our membership, and to help AGA members feel more connected by learning more about each other. Our inaugural Member Spotlight column highlights Patricia Jones, MD, associate professor at the University of Miami and an accomplished hepatologist. We thank Dr. Jones for sharing her story with us.

This will be a recurring monthly feature, so please consider nominating your colleagues (including trainees, practicing GIs in academics and community practice, those with non-traditional careers or unique pursuits outside of medicine, and others) to be featured in future Member Spotlight columns! It’s a great way for the nominee’s accomplishments to be recognized and to build a sense of community among the broader AGA membership. To submit a nomination, please send the nominee’s name, email, and a brief description of why you are nominating them to: GINews@gastro.org. We look forward to reviewing your submissions and hope you will use these Member Spotlights as an opportunity to strike up a conversation with someone new and expand your networks.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Happy New Year, everyone! In early December, I attended the 2022 AGA Women’s Leadership Collaboration Conference to discuss strategies to promote gender equity in our profession. It was an inspiring weekend and reminded me how many talented individuals we have in the field of gastroenterology, all with fascinating personal and professional stories and much to contribute. I think I speak for all attendees in saying that it was a privilege to have the opportunity to interact with this amazing group of women leaders, reflect on our shared experiences and visions for the future of GI, and expand our networks.

This month we are excited to launch a new recurring feature in the newspaper and online – the Member Spotlight column. AGA has more than16,000 members from varied backgrounds. Yet the reality is that each of our individual networks is much smaller, and we would all benefit from learning more about one other and building a greater sense of community. To that end, starting with this issue, we will feature a different AGA member each month in our Member Spotlight column. The goal of this new feature is to recognize AGA members’ accomplishments across all career stages and practice settings, to highlight the diversity of our membership, and to help AGA members feel more connected by learning more about each other. Our inaugural Member Spotlight column highlights Patricia Jones, MD, associate professor at the University of Miami and an accomplished hepatologist. We thank Dr. Jones for sharing her story with us.

This will be a recurring monthly feature, so please consider nominating your colleagues (including trainees, practicing GIs in academics and community practice, those with non-traditional careers or unique pursuits outside of medicine, and others) to be featured in future Member Spotlight columns! It’s a great way for the nominee’s accomplishments to be recognized and to build a sense of community among the broader AGA membership. To submit a nomination, please send the nominee’s name, email, and a brief description of why you are nominating them to: GINews@gastro.org. We look forward to reviewing your submissions and hope you will use these Member Spotlights as an opportunity to strike up a conversation with someone new and expand your networks.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Happy New Year, everyone! In early December, I attended the 2022 AGA Women’s Leadership Collaboration Conference to discuss strategies to promote gender equity in our profession. It was an inspiring weekend and reminded me how many talented individuals we have in the field of gastroenterology, all with fascinating personal and professional stories and much to contribute. I think I speak for all attendees in saying that it was a privilege to have the opportunity to interact with this amazing group of women leaders, reflect on our shared experiences and visions for the future of GI, and expand our networks.

This month we are excited to launch a new recurring feature in the newspaper and online – the Member Spotlight column. AGA has more than16,000 members from varied backgrounds. Yet the reality is that each of our individual networks is much smaller, and we would all benefit from learning more about one other and building a greater sense of community. To that end, starting with this issue, we will feature a different AGA member each month in our Member Spotlight column. The goal of this new feature is to recognize AGA members’ accomplishments across all career stages and practice settings, to highlight the diversity of our membership, and to help AGA members feel more connected by learning more about each other. Our inaugural Member Spotlight column highlights Patricia Jones, MD, associate professor at the University of Miami and an accomplished hepatologist. We thank Dr. Jones for sharing her story with us.

This will be a recurring monthly feature, so please consider nominating your colleagues (including trainees, practicing GIs in academics and community practice, those with non-traditional careers or unique pursuits outside of medicine, and others) to be featured in future Member Spotlight columns! It’s a great way for the nominee’s accomplishments to be recognized and to build a sense of community among the broader AGA membership. To submit a nomination, please send the nominee’s name, email, and a brief description of why you are nominating them to: GINews@gastro.org. We look forward to reviewing your submissions and hope you will use these Member Spotlights as an opportunity to strike up a conversation with someone new and expand your networks.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

GIHN’s Crystal Anniversary: Reflecting on the future of GI

Our December 2022 issue marks the conclusion of GIHN’s 15th Anniversary Series. We hope you have enjoyed these special articles intended to celebrate the success of AGA’s official newspaper since its launch in 2007, mirroring equally rapid advances in our field. Over the past year, GIHN’s esteemed Associate Editors and former Editors-in-Chief have helped us “look back” on how the fields of gastroenterology and hepatology have changed since the newspaper’s inception, including advances in our understanding of the microbiome, innovations in endoscopic practice, changes in the demographics of the GI workforce, and breakthroughs in the treatment of hepatitis C. Now, as we conclude our 15th-anniversary year, it is only fitting that we “look forward” and consider the type of innovative coverage that will grace GIHN’s pages in the future. To that end, we asked a distinguished group of AGA thought leaders, representing various backgrounds and practice settings, to share their perspectives on what are likely to be the biggest change(s) in the field of GI over the next 15 years. We hope you find their answers inspiring as you consider your own reflections on this question.

As we close out 2022, we also wish to extend a big “thank you” to all the individuals who have provided thoughtful commentary to our coverage, helping us to understand the implications of innovative research findings on clinical practice and how changes in health policy impact our practices and our patients. I would also like to acknowledge our hardworking AGA and Frontline Medical Communications editorial teams, without whom this publication would not be possible. We wish you all a restful holiday season with your family and friends and look forward to reconnecting in 2023 – stay tuned for the launch of an exciting new GIHN initiative as part of our January issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Our December 2022 issue marks the conclusion of GIHN’s 15th Anniversary Series. We hope you have enjoyed these special articles intended to celebrate the success of AGA’s official newspaper since its launch in 2007, mirroring equally rapid advances in our field. Over the past year, GIHN’s esteemed Associate Editors and former Editors-in-Chief have helped us “look back” on how the fields of gastroenterology and hepatology have changed since the newspaper’s inception, including advances in our understanding of the microbiome, innovations in endoscopic practice, changes in the demographics of the GI workforce, and breakthroughs in the treatment of hepatitis C. Now, as we conclude our 15th-anniversary year, it is only fitting that we “look forward” and consider the type of innovative coverage that will grace GIHN’s pages in the future. To that end, we asked a distinguished group of AGA thought leaders, representing various backgrounds and practice settings, to share their perspectives on what are likely to be the biggest change(s) in the field of GI over the next 15 years. We hope you find their answers inspiring as you consider your own reflections on this question.

As we close out 2022, we also wish to extend a big “thank you” to all the individuals who have provided thoughtful commentary to our coverage, helping us to understand the implications of innovative research findings on clinical practice and how changes in health policy impact our practices and our patients. I would also like to acknowledge our hardworking AGA and Frontline Medical Communications editorial teams, without whom this publication would not be possible. We wish you all a restful holiday season with your family and friends and look forward to reconnecting in 2023 – stay tuned for the launch of an exciting new GIHN initiative as part of our January issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Our December 2022 issue marks the conclusion of GIHN’s 15th Anniversary Series. We hope you have enjoyed these special articles intended to celebrate the success of AGA’s official newspaper since its launch in 2007, mirroring equally rapid advances in our field. Over the past year, GIHN’s esteemed Associate Editors and former Editors-in-Chief have helped us “look back” on how the fields of gastroenterology and hepatology have changed since the newspaper’s inception, including advances in our understanding of the microbiome, innovations in endoscopic practice, changes in the demographics of the GI workforce, and breakthroughs in the treatment of hepatitis C. Now, as we conclude our 15th-anniversary year, it is only fitting that we “look forward” and consider the type of innovative coverage that will grace GIHN’s pages in the future. To that end, we asked a distinguished group of AGA thought leaders, representing various backgrounds and practice settings, to share their perspectives on what are likely to be the biggest change(s) in the field of GI over the next 15 years. We hope you find their answers inspiring as you consider your own reflections on this question.

As we close out 2022, we also wish to extend a big “thank you” to all the individuals who have provided thoughtful commentary to our coverage, helping us to understand the implications of innovative research findings on clinical practice and how changes in health policy impact our practices and our patients. I would also like to acknowledge our hardworking AGA and Frontline Medical Communications editorial teams, without whom this publication would not be possible. We wish you all a restful holiday season with your family and friends and look forward to reconnecting in 2023 – stay tuned for the launch of an exciting new GIHN initiative as part of our January issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Medical professional liability risk and mitigation: An overview for early-career gastroenterologists

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. All examples are hypothetical and aim to illustrate common clinical scenarios and challenges gastroenterologists may encounter within their scope of practice. The content herein should not be interpreted as legal advice for individual cases nor a substitute for seeking the advice of an attorney.

There are unique potential stressors faced by the gastroenterologist at each career stage, some more so early on. One such stressor, and one particularly important in a procedure-intensive specialty like GI, is medical professional liability (MPL), historically termed “medical malpractice.” Between 2009 and 2018, GI was the second-highest internal medicine subspecialty in both MPL claims made and claims paid,1 yet instruction on MPL risk and mitigation is scarce in fellowship, as is the available GI-related literature on the topic. This scarcity may generate untoward stress and unnecessarily expose gastroenterologists to avoidable MPL pitfalls. Therefore, it is vital for GI trainees, early-career gastroenterologists, and even seasoned gastroenterologists to have a working and updated knowledge of the general principles of MPL and GI-specific considerations. Such understanding can help preserve physician well-being, increase professional satisfaction, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and improve health care outcomes.2

To this end, we herein provide a focused review of the following: key MPL concepts, trends in MPL claims, GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations, adverse provider defensive mechanisms, documentation tenets, challenges posed by telemedicine, and the concept of “vicarious liability.”

Key MPL concepts

MPL falls under the umbrella of tort law, which itself falls under the umbrella of civil law; that is, civil (as opposed to criminal) justice governs torts – including but not limited to MPL claims – as well as other areas of law concerning noncriminal injury.3 A “tort” is a “civil wrong that unfairly causes another to experience loss or harm resulting in legal liability.”3 MPL claims assert the tort of negligence (similar to the concept of “incompetence”) and endeavor to compensate the harmed patient/individual while simultaneously dissuading suboptimal medical care by the provider in the future.4,5 A successful MPL claim must prove four overlapping elements: that the tortfeasor (here, the gastroenterologist) owed a duty of care to the injured party and breached that duty, which caused damages.6 Given that MPL cases exist within tort law rather than criminal law, the burden of proof for these cases is not “beyond a reasonable doubt”; instead, it’s “to a reasonable medical probability.”7

Trends in MPL claims

According to data compiled by the MPL Association, 278,220 MPL claims were made in the United States from 1985 to 2012.3,8-10 Among these, 1.8% involved gastroenterologists, which puts it at 17th place out of the 20 specialties surveyed.9 While the number of paid claims over this time frame decreased in GI by 34.6% (from 18.5 to 12.1 cases per 1,000 physician-years), there was a concurrent 23.3% increase in average claim compensation; essentially, there were fewer paid GI-related claims but there were higher payouts per paid claim.11,12 From 2009 to 2018, average legal defense costs for paid GI-related claims were $97,392, and average paid amount was $330,876.1

GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations

Many MPL claims relate to situations involving medical errors or adverse events (AEs), be they procedural or nonprocedural. However other aspects of GI also carry MPL risk.

Informed consent

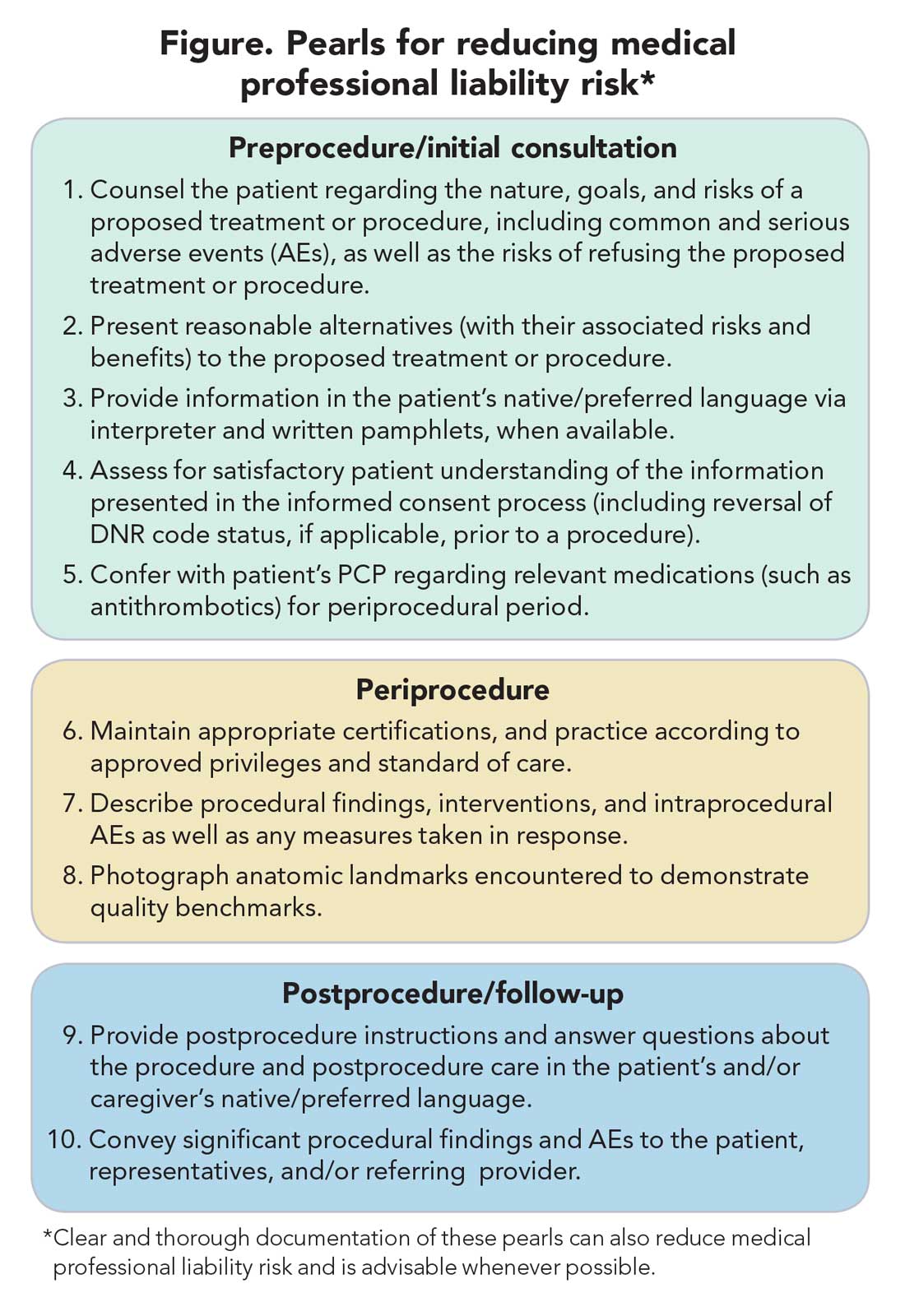

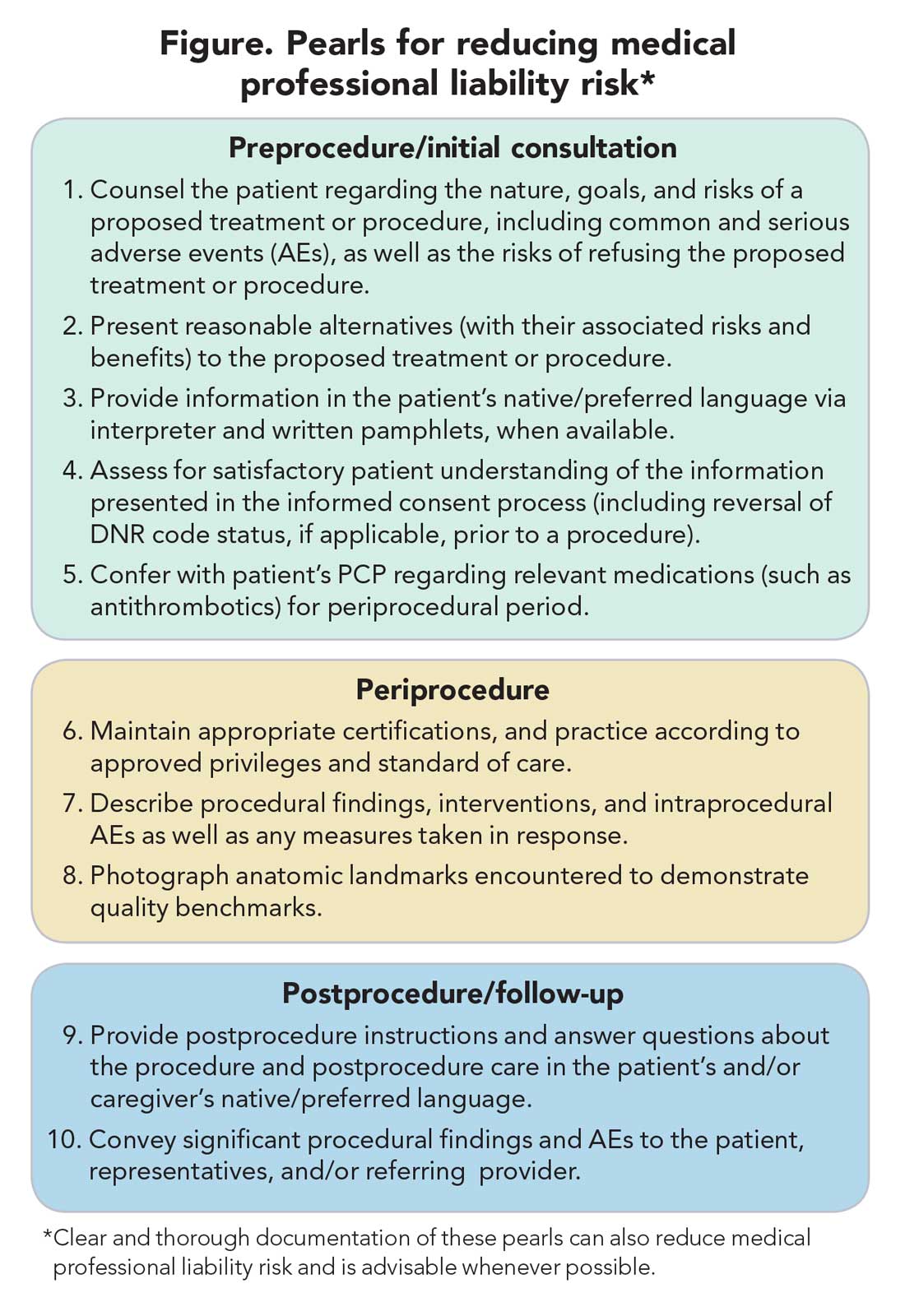

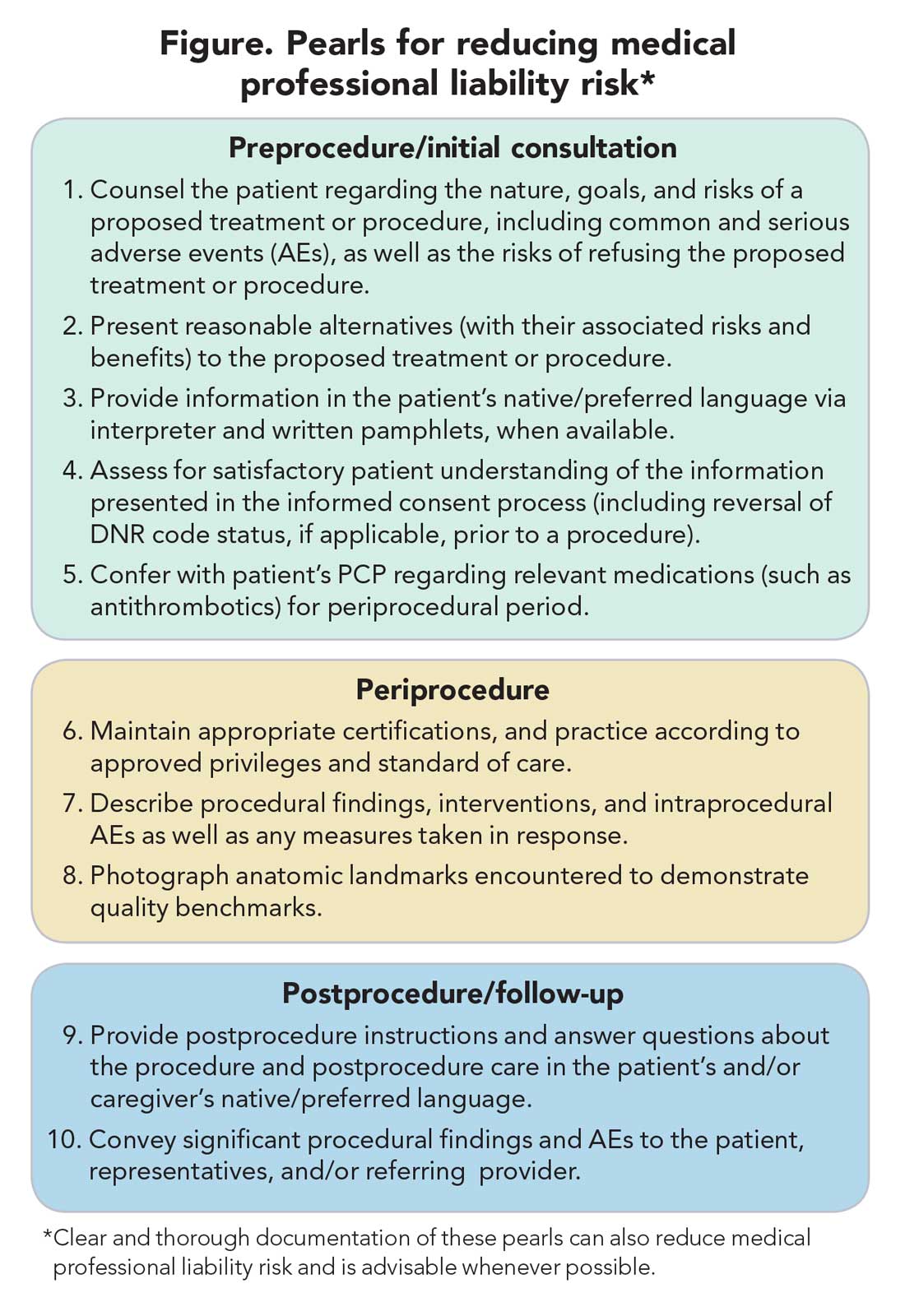

MPL claims may be made not only on the grounds of inadequately informed consent but also inadequately informed refusal.5,13,14 While standards for adequate informed consent vary by state, most states apply the “reasonable patient standard,” i.e., assuming an average patient with enough information to be an active participant in the medical decision-making process. Generally, informed consent should ensure that the patient understands the nature of the procedure/treatment being proposed, there is a discussion of the risks and benefits of undergoing and not undergoing the procedure/treatment, reasonable alternatives are presented, the risks and benefits associated with these alternatives are discussed, and the patient’s comprehension of these things is assessed (Figure).15 Additionally, informed consent should be tailored to each patient and GI procedure/treatment on a case-by-case basis rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, documentation of the patient’s understanding of the (tailored) information provided can concurrently improve quality of the consent and potentially decrease MPL risk (Figure).16

Endoscopic procedures

Procedure-related MPL claims represent approximately 25% of all GI-related claims (8,17). Among these, 52% involve colonoscopy, 16% involve endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and 11% involve esophagogastroduodenoscopy.8 Albeit generally safe, colonoscopy, as with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, is subject to rare but serious AEs.18,19 Risk of these AEs may be accentuated in certain scenarios (such as severe colonic inflammation or coagulopathy) and, as discussed earlier, may merit tailored informed consent. Regardless of the procedure, in the event of postprocedural development of signs/symptoms (such as tachycardia, fever, chest or abdominal discomfort, or hypotension) indicating a potential AE, stabilizing measures and evaluation (such as blood work and imaging) should be undertaken, and hospital admission (if not already hospitalized) should be considered until discharge is deemed safe.19

ERCP-related MPL claims, for many years, have had the highest average compensation of any GI procedure.11 Though discussion of advanced procedures is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning the observation that most of such claims involve an allegation that the procedure was not indicated (for example, that it was performed based on inadequate evidence of pancreatobiliary pathology), or was for diagnostic purposes (for example, being done instead of noninvasive imaging) rather than therapeutic.20-23 This emphasizes the importance of appropriate procedure indications.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement merits special mention given it can be complicated by ethical challenges (for example, needing a surrogate decision-maker’s consent or representing medical futility) and has a relatively high potential for MPL claims. PEG placement carries a low AE rate (0.1%-1%), but these AEs may result in high morbidity/mortality, in part because of the underlying comorbidities of patients needing PEG placement.24,25 Also, timing of a patient’s demise may coincide with PEG placement, thereby prompting (possibly unfounded) perceptions of causality.24-27 Therefore, such scenarios merit unique additional preprocedure safeguards. For instance, for patients lacking capacity to provide informed consent, especially when family members may differ on whether PEG should be placed, it is advisable to ask the family to select one surrogate decision-maker (if there’s no advance directive) to whom the gastroenterologist should discuss both the risks, benefits, and goals of PEG placement in the context of the patient’s overall clinical trajectory/life expectancy and the need for consent (or refusal) based on what the patient would have wished. In addition, having a medical professional witness this discussion may be useful.27

Antithrombotic agents

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics, including anticoagulants and antiplatelets, can pose challenges for the gastroenterologist. While clinical practice guidelines exist to guide decision-making in this regard, the variables involved may extend beyond the expertise of the gastroenterologist.28 For instance, in addition to the procedural risk for bleeding, the indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk of a thrombotic event, duration of action of the antithrombotic, and available bridging options should all be considered according to recommendations.28,29 While requiring more time on the part of the gastroenterologist, the optimal periprocedural management of antithrombotic agents would usually involve discussion with the provider managing antithrombotic therapy to best conduct a risk-benefit assessment regarding if (and how long) the antithrombotic therapy should be held (Figure). This shared decision-making, which should also include the patient, may help decrease MPL risk and improve outcomes.

Provider defense mechanisms

Physicians may engage in various defensive behaviors in an attempt to mitigate MPL risk; however, these behaviors may, paradoxically, increase risk.30,31

Assurance behaviors

Assurance behaviors refer to the practice of recommending or performing additional services (such as medications, imaging, procedures, and referrals) that are not clearly indicated.2,30,31 Assurance behaviors are driven by fear of MPL risk and/or missing a potential diagnosis. Recent studies have estimated that more than 50% of gastroenterologists worldwide have performed additional invasive procedures without clear indications, and that nearly one-third of endoscopic procedures annually have questionable indications.30,32 While assurance behaviors may seem likely to decrease MPL risk, overall, they may inadvertently increase AE and MPL risk, as well as health care expenditures.3,30,32

Avoidance behaviors

Avoidance behaviors refer to providers avoiding participation in potentially high-risk clinical interventions (for example, the actual procedures), including those for which they are credentialed/certified proficient.30,31 Two clinical scenarios that illustrate this behavior include the following: An advanced endoscopist credentialed to perform ERCP might refer a “high-risk” elderly patient with cholangitis to another provider to perform said ERCP or for percutaneous transhepatic drainage (in the absence of a clear benefit to such), or a gastroenterologist might refer a patient to interventional gastroenterology for resection of a large polyp even though gastroenterologists are usually proficient in this skill and may feel comfortable performing the resection themselves. Avoidance behaviors are driven by a fear of MPL risk and can have several negative consequences.33 For example, patients may not receive indicated interventions. Additionally, patients may have to wait longer for an intervention because they are referred to another provider, which also increases potential for loss to follow-up.2,30,31 This may be viewed as noncompliance with the standard of care, among other hazards, thereby increasing MPL risk.

Documentation tenets

Thorough documentation can decrease MPL risk, especially since it is often used as legal evidence.16 Documenting, for instance, preprocedure discussion of potential risk of AEs (such as bleeding or perforation) or procedural failure (for example, missed lesions)can protect gastroenterologists (Figure).16 While, as discussed previously, these should be covered in the informed consent process (which itself reduces MPL risk), proof of compliance in providing adequate informed consent must come in the form of documentation that indicates that the process took place and specifically what topics were discussed therein. MPL risk may be further decreased by documenting steps taken during a procedure and anatomic landmarks encountered to offer proof of technical competency and compliance with standards of care (Figure).16,34 In this context, it is worth recalling the adage: “If it’s not documented, it did not occur.”

Curbside consults versus consultation

Also germane here is the topic of whether documentation is needed for “curbside consults.” The uncertainty is, in part, semantic; that is, at what point does a “curbside” become a consultation? A curbside is a general question or query (such as anything that could also be answered by searching the Internet or reference materials) in response to which information is provided; once it involves provision of medical advice for a specific patient (for example, when patient identifiers have been shared or their EHR has been accessed), it constitutes a consultation. Based on these definitions, a curbside need not be documented, whereas a consultation – even if seemingly trivial – should be.

Consideration of language and cultural factors

Language barriers should be considered when the gastroenterologist is communicating with the patient, and such efforts, whenever made, should be documented to best protect against MPL.16,35 These considerations arise not only during the consent process but when obtaining a history, providing postprocedure instructions, and during follow-ups. To this end, 24/7 telephone interpreter services may assist the gastroenterologist (when one is communicating with non–English speakers and is not medically certified in the patient’s native/preferred language) and strengthen trust in the provider-patient relationship.36 Additionally, written materials (such as consent forms, procedural information) in patients’ native/preferred languages should be provided, when available, to enhance patient understanding and participation in care (Figure).35

Challenges posed by telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly led to more virtual encounters. While increased utilization of telemedicine platforms may make health care more accessible, it does not lessen the clinicians’ duty to patients and may actually expose them to greater MPL risk.18,37,38 Therefore, the provider must be cognizant of two key principles to mitigate MPL risk in the context of telemedicine encounters. First, the same standard of care applies to virtual and in-person encounters.18,37,38 Second, patient privacy and HIPAA regulations are not waived during telemedicine encounters, and breaches of such may result in an MPL claim.18,37,38

With regard to the first principle, for patients who have not been physically examined (such as when a telemedicine visit was substituted for an in-person clinic encounter), gastroenterologists should not overlook requesting timely preprocedure anesthesia consultation or obtaining additional laboratory studies as needed to ensure safety and the same standard of care. Moreover, particularly in the context of pandemic-related decreased procedural capacity, triaging procedures can be especially challenging. Standardized institutional criteria which prioritize certain diagnoses/conditions over others, leaving room for justifiable exceptions, are advisable.

Vicarious liability

“Vicarious liability” is defined as that extending to persons who have not committed a wrong but on whose behalf wrongdoers acted.39 Therefore, gastroenterologists may be liable not only for their own actions but also for those of personnel they supervise (such as fellow trainees and non–physician practitioners).39 Vicarious liability aims to ensure that systemic checks and balances are in place so that, if failure occurs, harm can still be mitigated and/or avoided, as illustrated by Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model.”40

Conclusion

Any gastroenterologist can experience an MPL claim. Such an experience can be especially stressful and confusing to early-career clinicians, especially if they’re unfamiliar with legal proceedings. Although MPL principles are not often taught in medical school or residency, it is important for gastroenterologists to be informed regarding tenets of MPL and cognizant of clinical situations which have relatively higher MPL risk. This can assuage untoward angst regarding MPL and highlight proactive risk-mitigation strategies. In general, gastroenterologist practices that can mitigate MPL risk include effective communication; adequate informed consent/refusal; documentation of preprocedure counseling, periprocedure events, and postprocedure recommendations; and maintenance of proper certification and privileging.

Dr. Azizian and Dr. Dalai are with the University of California, Los Angeles and the department of medicine at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center, Sylmar, Calif. They are co–first authors of this paper. Dr. Dalai is also with the division of gastroenterology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Adams is with the Center for Clinical Management Research in Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System, the division of gastroenterology at the University of Michigan Health System, and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, all in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Tabibian is with UCLA and the division of gastroenterology at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. 2020 Data Sharing Project Gastroenterology 2009-2018. Inside Medical Liability: Second Quarter. Accessed 2020 Dec 6.

2. Mello MM et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004 Jul-Aug;23(4):42-53.

3. Adams MA et al. JAMA. 2014 Oct;312(13):1348-9.

4. Pegalis SE. American Law of Medical Malpractice 3d, Vol. 2. St. Paul, Minn.: Thomson Reuters, 2005.

5. Feld LD et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;113(11):1577-9.

6. Sawyer v. Wight, 196 F. Supp. 2d 220, 226 (E.D.N.Y. 2002).

7. Michael A. Sita v. Long Island Jewish-Hillside Medical Center, 22 A.D.3d 743 (N.Y. App. Div. 2005).

8. Conklin LS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jun;6(6):677-81.

9. Jena AB et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 18;365(7):629-36.

10. Kane CK. “Policy Research Perspectives Medical Liability Claim Frequency: A 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians.” Chicago: American Medical Association, 2010.

11. Hernandez LV et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Apr 16;5(4):169-73.

12. Schaffer AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 May 1;177(5):710-8.

13. Natanson v. Kline, 186 Kan. 393, 409, 350 P.2d 1093, 1106, decision clarified on denial of reh’g, 187 Kan. 186, 354 P.2d 670 (1960).

14. Truman v. Thomas, 27 Cal. 3d 285, 292, 611 P.2d 902, 906 (1980).

15. Shah P et al. Informed Consent, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Aug 22.

16. Rex DK. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Jul;11(7):768-73.

17. Gerstenberger PD, Plumeri PA. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar-Apr 1993;39(2):132-8.

18. Adams MA and Allen JI. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Nov;17(12):2392-6.e1.

19. Ahlawat R et al. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Dec 9.

20. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Mar;63(3):378-82.

21. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):904.

22. Adamson TE et al. West J Med. 1989 Mar;150(3):356-60.

23. Trap R et al. Endoscopy. 1999 Feb;31(2):125-30.

24. Funaki B. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015 Mar;32(1):61-4.

25. Feeding Tube Nursing Home and Hospital Malpractice. Miller & Zois, Attorneys at Law. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

26. Medical Malpractice Lawsuit Brings $750,000 Settlement: Death of 82-year-old woman from sepsis due to improper placement of feeding tube. Lubin & Meyers PC. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

27. Brendel RW et al. Med Clin North Am. 2010 Nov;94(6):1229-40, xi-ii.

28. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Acosta RD et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jan;83(1):3-16.

29. Saleem S and Thomas AL. Cureus. 2018 Jun 25;10(6):e2878.

30. Hiyama T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec 21;12(47):7671-5.

31. Studdert DM et al. JAMA. 2005 Jun 1;293(21):2609-17.

32. Shaheen NJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May;154(7):1993-2003.

33. Oza VM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Feb;14(2):172-4.

34. Feld AD. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002 Jan;12(1):171-9, viii-ix.

35. Lee JS et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Aug;32(8):863-70.

36. Forrow L and Kontrimas JC. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Aug;32(8):855-7.

37. Moses RE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug;109(8):1128-32.

38. Tabibian JH. “The Evolution of Telehealth.” Guidepoint: Legal Solutions Blog. Accessed 2020 Aug 12.

39. Feld AD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;99(9):1641-4.

40. Reason J. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):768‐70.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. All examples are hypothetical and aim to illustrate common clinical scenarios and challenges gastroenterologists may encounter within their scope of practice. The content herein should not be interpreted as legal advice for individual cases nor a substitute for seeking the advice of an attorney.

There are unique potential stressors faced by the gastroenterologist at each career stage, some more so early on. One such stressor, and one particularly important in a procedure-intensive specialty like GI, is medical professional liability (MPL), historically termed “medical malpractice.” Between 2009 and 2018, GI was the second-highest internal medicine subspecialty in both MPL claims made and claims paid,1 yet instruction on MPL risk and mitigation is scarce in fellowship, as is the available GI-related literature on the topic. This scarcity may generate untoward stress and unnecessarily expose gastroenterologists to avoidable MPL pitfalls. Therefore, it is vital for GI trainees, early-career gastroenterologists, and even seasoned gastroenterologists to have a working and updated knowledge of the general principles of MPL and GI-specific considerations. Such understanding can help preserve physician well-being, increase professional satisfaction, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and improve health care outcomes.2

To this end, we herein provide a focused review of the following: key MPL concepts, trends in MPL claims, GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations, adverse provider defensive mechanisms, documentation tenets, challenges posed by telemedicine, and the concept of “vicarious liability.”

Key MPL concepts

MPL falls under the umbrella of tort law, which itself falls under the umbrella of civil law; that is, civil (as opposed to criminal) justice governs torts – including but not limited to MPL claims – as well as other areas of law concerning noncriminal injury.3 A “tort” is a “civil wrong that unfairly causes another to experience loss or harm resulting in legal liability.”3 MPL claims assert the tort of negligence (similar to the concept of “incompetence”) and endeavor to compensate the harmed patient/individual while simultaneously dissuading suboptimal medical care by the provider in the future.4,5 A successful MPL claim must prove four overlapping elements: that the tortfeasor (here, the gastroenterologist) owed a duty of care to the injured party and breached that duty, which caused damages.6 Given that MPL cases exist within tort law rather than criminal law, the burden of proof for these cases is not “beyond a reasonable doubt”; instead, it’s “to a reasonable medical probability.”7

Trends in MPL claims

According to data compiled by the MPL Association, 278,220 MPL claims were made in the United States from 1985 to 2012.3,8-10 Among these, 1.8% involved gastroenterologists, which puts it at 17th place out of the 20 specialties surveyed.9 While the number of paid claims over this time frame decreased in GI by 34.6% (from 18.5 to 12.1 cases per 1,000 physician-years), there was a concurrent 23.3% increase in average claim compensation; essentially, there were fewer paid GI-related claims but there were higher payouts per paid claim.11,12 From 2009 to 2018, average legal defense costs for paid GI-related claims were $97,392, and average paid amount was $330,876.1

GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations

Many MPL claims relate to situations involving medical errors or adverse events (AEs), be they procedural or nonprocedural. However other aspects of GI also carry MPL risk.

Informed consent

MPL claims may be made not only on the grounds of inadequately informed consent but also inadequately informed refusal.5,13,14 While standards for adequate informed consent vary by state, most states apply the “reasonable patient standard,” i.e., assuming an average patient with enough information to be an active participant in the medical decision-making process. Generally, informed consent should ensure that the patient understands the nature of the procedure/treatment being proposed, there is a discussion of the risks and benefits of undergoing and not undergoing the procedure/treatment, reasonable alternatives are presented, the risks and benefits associated with these alternatives are discussed, and the patient’s comprehension of these things is assessed (Figure).15 Additionally, informed consent should be tailored to each patient and GI procedure/treatment on a case-by-case basis rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, documentation of the patient’s understanding of the (tailored) information provided can concurrently improve quality of the consent and potentially decrease MPL risk (Figure).16

Endoscopic procedures

Procedure-related MPL claims represent approximately 25% of all GI-related claims (8,17). Among these, 52% involve colonoscopy, 16% involve endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and 11% involve esophagogastroduodenoscopy.8 Albeit generally safe, colonoscopy, as with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, is subject to rare but serious AEs.18,19 Risk of these AEs may be accentuated in certain scenarios (such as severe colonic inflammation or coagulopathy) and, as discussed earlier, may merit tailored informed consent. Regardless of the procedure, in the event of postprocedural development of signs/symptoms (such as tachycardia, fever, chest or abdominal discomfort, or hypotension) indicating a potential AE, stabilizing measures and evaluation (such as blood work and imaging) should be undertaken, and hospital admission (if not already hospitalized) should be considered until discharge is deemed safe.19

ERCP-related MPL claims, for many years, have had the highest average compensation of any GI procedure.11 Though discussion of advanced procedures is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning the observation that most of such claims involve an allegation that the procedure was not indicated (for example, that it was performed based on inadequate evidence of pancreatobiliary pathology), or was for diagnostic purposes (for example, being done instead of noninvasive imaging) rather than therapeutic.20-23 This emphasizes the importance of appropriate procedure indications.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement merits special mention given it can be complicated by ethical challenges (for example, needing a surrogate decision-maker’s consent or representing medical futility) and has a relatively high potential for MPL claims. PEG placement carries a low AE rate (0.1%-1%), but these AEs may result in high morbidity/mortality, in part because of the underlying comorbidities of patients needing PEG placement.24,25 Also, timing of a patient’s demise may coincide with PEG placement, thereby prompting (possibly unfounded) perceptions of causality.24-27 Therefore, such scenarios merit unique additional preprocedure safeguards. For instance, for patients lacking capacity to provide informed consent, especially when family members may differ on whether PEG should be placed, it is advisable to ask the family to select one surrogate decision-maker (if there’s no advance directive) to whom the gastroenterologist should discuss both the risks, benefits, and goals of PEG placement in the context of the patient’s overall clinical trajectory/life expectancy and the need for consent (or refusal) based on what the patient would have wished. In addition, having a medical professional witness this discussion may be useful.27

Antithrombotic agents

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics, including anticoagulants and antiplatelets, can pose challenges for the gastroenterologist. While clinical practice guidelines exist to guide decision-making in this regard, the variables involved may extend beyond the expertise of the gastroenterologist.28 For instance, in addition to the procedural risk for bleeding, the indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk of a thrombotic event, duration of action of the antithrombotic, and available bridging options should all be considered according to recommendations.28,29 While requiring more time on the part of the gastroenterologist, the optimal periprocedural management of antithrombotic agents would usually involve discussion with the provider managing antithrombotic therapy to best conduct a risk-benefit assessment regarding if (and how long) the antithrombotic therapy should be held (Figure). This shared decision-making, which should also include the patient, may help decrease MPL risk and improve outcomes.

Provider defense mechanisms

Physicians may engage in various defensive behaviors in an attempt to mitigate MPL risk; however, these behaviors may, paradoxically, increase risk.30,31

Assurance behaviors

Assurance behaviors refer to the practice of recommending or performing additional services (such as medications, imaging, procedures, and referrals) that are not clearly indicated.2,30,31 Assurance behaviors are driven by fear of MPL risk and/or missing a potential diagnosis. Recent studies have estimated that more than 50% of gastroenterologists worldwide have performed additional invasive procedures without clear indications, and that nearly one-third of endoscopic procedures annually have questionable indications.30,32 While assurance behaviors may seem likely to decrease MPL risk, overall, they may inadvertently increase AE and MPL risk, as well as health care expenditures.3,30,32

Avoidance behaviors

Avoidance behaviors refer to providers avoiding participation in potentially high-risk clinical interventions (for example, the actual procedures), including those for which they are credentialed/certified proficient.30,31 Two clinical scenarios that illustrate this behavior include the following: An advanced endoscopist credentialed to perform ERCP might refer a “high-risk” elderly patient with cholangitis to another provider to perform said ERCP or for percutaneous transhepatic drainage (in the absence of a clear benefit to such), or a gastroenterologist might refer a patient to interventional gastroenterology for resection of a large polyp even though gastroenterologists are usually proficient in this skill and may feel comfortable performing the resection themselves. Avoidance behaviors are driven by a fear of MPL risk and can have several negative consequences.33 For example, patients may not receive indicated interventions. Additionally, patients may have to wait longer for an intervention because they are referred to another provider, which also increases potential for loss to follow-up.2,30,31 This may be viewed as noncompliance with the standard of care, among other hazards, thereby increasing MPL risk.

Documentation tenets

Thorough documentation can decrease MPL risk, especially since it is often used as legal evidence.16 Documenting, for instance, preprocedure discussion of potential risk of AEs (such as bleeding or perforation) or procedural failure (for example, missed lesions)can protect gastroenterologists (Figure).16 While, as discussed previously, these should be covered in the informed consent process (which itself reduces MPL risk), proof of compliance in providing adequate informed consent must come in the form of documentation that indicates that the process took place and specifically what topics were discussed therein. MPL risk may be further decreased by documenting steps taken during a procedure and anatomic landmarks encountered to offer proof of technical competency and compliance with standards of care (Figure).16,34 In this context, it is worth recalling the adage: “If it’s not documented, it did not occur.”

Curbside consults versus consultation

Also germane here is the topic of whether documentation is needed for “curbside consults.” The uncertainty is, in part, semantic; that is, at what point does a “curbside” become a consultation? A curbside is a general question or query (such as anything that could also be answered by searching the Internet or reference materials) in response to which information is provided; once it involves provision of medical advice for a specific patient (for example, when patient identifiers have been shared or their EHR has been accessed), it constitutes a consultation. Based on these definitions, a curbside need not be documented, whereas a consultation – even if seemingly trivial – should be.

Consideration of language and cultural factors

Language barriers should be considered when the gastroenterologist is communicating with the patient, and such efforts, whenever made, should be documented to best protect against MPL.16,35 These considerations arise not only during the consent process but when obtaining a history, providing postprocedure instructions, and during follow-ups. To this end, 24/7 telephone interpreter services may assist the gastroenterologist (when one is communicating with non–English speakers and is not medically certified in the patient’s native/preferred language) and strengthen trust in the provider-patient relationship.36 Additionally, written materials (such as consent forms, procedural information) in patients’ native/preferred languages should be provided, when available, to enhance patient understanding and participation in care (Figure).35

Challenges posed by telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly led to more virtual encounters. While increased utilization of telemedicine platforms may make health care more accessible, it does not lessen the clinicians’ duty to patients and may actually expose them to greater MPL risk.18,37,38 Therefore, the provider must be cognizant of two key principles to mitigate MPL risk in the context of telemedicine encounters. First, the same standard of care applies to virtual and in-person encounters.18,37,38 Second, patient privacy and HIPAA regulations are not waived during telemedicine encounters, and breaches of such may result in an MPL claim.18,37,38

With regard to the first principle, for patients who have not been physically examined (such as when a telemedicine visit was substituted for an in-person clinic encounter), gastroenterologists should not overlook requesting timely preprocedure anesthesia consultation or obtaining additional laboratory studies as needed to ensure safety and the same standard of care. Moreover, particularly in the context of pandemic-related decreased procedural capacity, triaging procedures can be especially challenging. Standardized institutional criteria which prioritize certain diagnoses/conditions over others, leaving room for justifiable exceptions, are advisable.

Vicarious liability

“Vicarious liability” is defined as that extending to persons who have not committed a wrong but on whose behalf wrongdoers acted.39 Therefore, gastroenterologists may be liable not only for their own actions but also for those of personnel they supervise (such as fellow trainees and non–physician practitioners).39 Vicarious liability aims to ensure that systemic checks and balances are in place so that, if failure occurs, harm can still be mitigated and/or avoided, as illustrated by Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model.”40

Conclusion

Any gastroenterologist can experience an MPL claim. Such an experience can be especially stressful and confusing to early-career clinicians, especially if they’re unfamiliar with legal proceedings. Although MPL principles are not often taught in medical school or residency, it is important for gastroenterologists to be informed regarding tenets of MPL and cognizant of clinical situations which have relatively higher MPL risk. This can assuage untoward angst regarding MPL and highlight proactive risk-mitigation strategies. In general, gastroenterologist practices that can mitigate MPL risk include effective communication; adequate informed consent/refusal; documentation of preprocedure counseling, periprocedure events, and postprocedure recommendations; and maintenance of proper certification and privileging.

Dr. Azizian and Dr. Dalai are with the University of California, Los Angeles and the department of medicine at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center, Sylmar, Calif. They are co–first authors of this paper. Dr. Dalai is also with the division of gastroenterology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Adams is with the Center for Clinical Management Research in Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System, the division of gastroenterology at the University of Michigan Health System, and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, all in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Tabibian is with UCLA and the division of gastroenterology at Olive View–UCLA Medical Center. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. 2020 Data Sharing Project Gastroenterology 2009-2018. Inside Medical Liability: Second Quarter. Accessed 2020 Dec 6.

2. Mello MM et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004 Jul-Aug;23(4):42-53.

3. Adams MA et al. JAMA. 2014 Oct;312(13):1348-9.

4. Pegalis SE. American Law of Medical Malpractice 3d, Vol. 2. St. Paul, Minn.: Thomson Reuters, 2005.

5. Feld LD et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;113(11):1577-9.

6. Sawyer v. Wight, 196 F. Supp. 2d 220, 226 (E.D.N.Y. 2002).

7. Michael A. Sita v. Long Island Jewish-Hillside Medical Center, 22 A.D.3d 743 (N.Y. App. Div. 2005).

8. Conklin LS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jun;6(6):677-81.

9. Jena AB et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 18;365(7):629-36.

10. Kane CK. “Policy Research Perspectives Medical Liability Claim Frequency: A 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians.” Chicago: American Medical Association, 2010.

11. Hernandez LV et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Apr 16;5(4):169-73.

12. Schaffer AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 May 1;177(5):710-8.

13. Natanson v. Kline, 186 Kan. 393, 409, 350 P.2d 1093, 1106, decision clarified on denial of reh’g, 187 Kan. 186, 354 P.2d 670 (1960).

14. Truman v. Thomas, 27 Cal. 3d 285, 292, 611 P.2d 902, 906 (1980).

15. Shah P et al. Informed Consent, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Aug 22.

16. Rex DK. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Jul;11(7):768-73.

17. Gerstenberger PD, Plumeri PA. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar-Apr 1993;39(2):132-8.

18. Adams MA and Allen JI. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Nov;17(12):2392-6.e1.

19. Ahlawat R et al. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2020 Jan. Updated 2020 Dec 9.

20. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Mar;63(3):378-82.

21. Cotton PB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):904.

22. Adamson TE et al. West J Med. 1989 Mar;150(3):356-60.

23. Trap R et al. Endoscopy. 1999 Feb;31(2):125-30.

24. Funaki B. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015 Mar;32(1):61-4.

25. Feeding Tube Nursing Home and Hospital Malpractice. Miller & Zois, Attorneys at Law. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

26. Medical Malpractice Lawsuit Brings $750,000 Settlement: Death of 82-year-old woman from sepsis due to improper placement of feeding tube. Lubin & Meyers PC. Accessed 2020 Jun 20.

27. Brendel RW et al. Med Clin North Am. 2010 Nov;94(6):1229-40, xi-ii.

28. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Acosta RD et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jan;83(1):3-16.

29. Saleem S and Thomas AL. Cureus. 2018 Jun 25;10(6):e2878.

30. Hiyama T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec 21;12(47):7671-5.

31. Studdert DM et al. JAMA. 2005 Jun 1;293(21):2609-17.

32. Shaheen NJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May;154(7):1993-2003.

33. Oza VM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Feb;14(2):172-4.