User login

Erythema multiforme secondary to HSV labialis precipitating sickle cell pain crisis

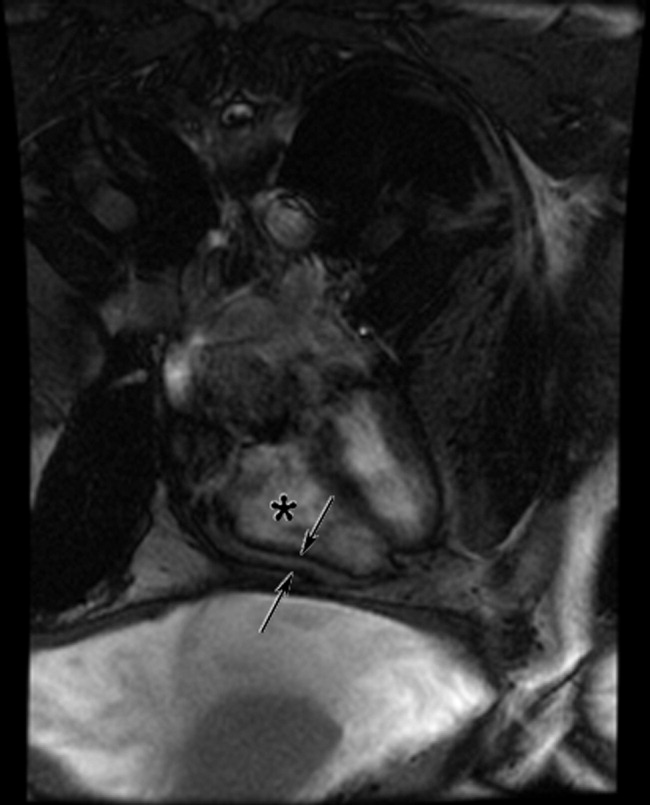

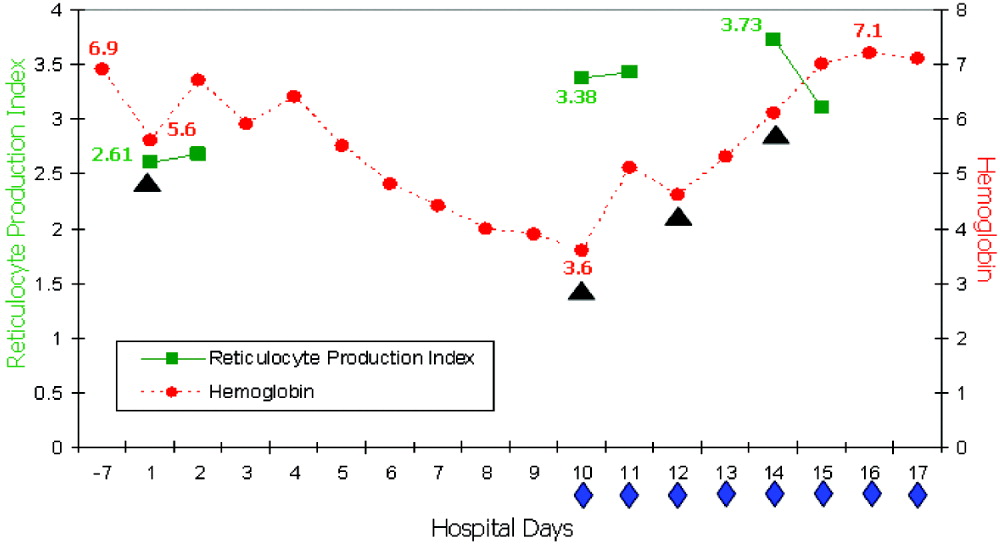

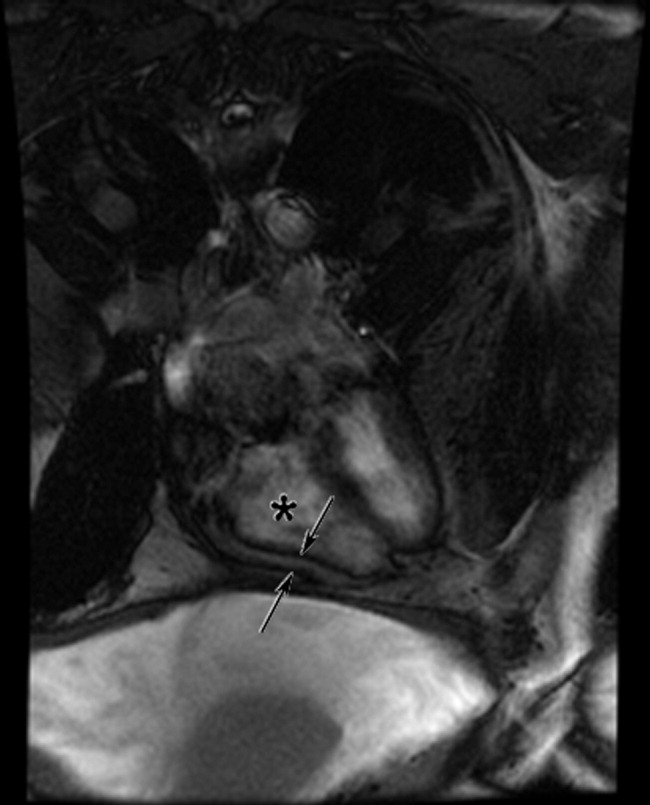

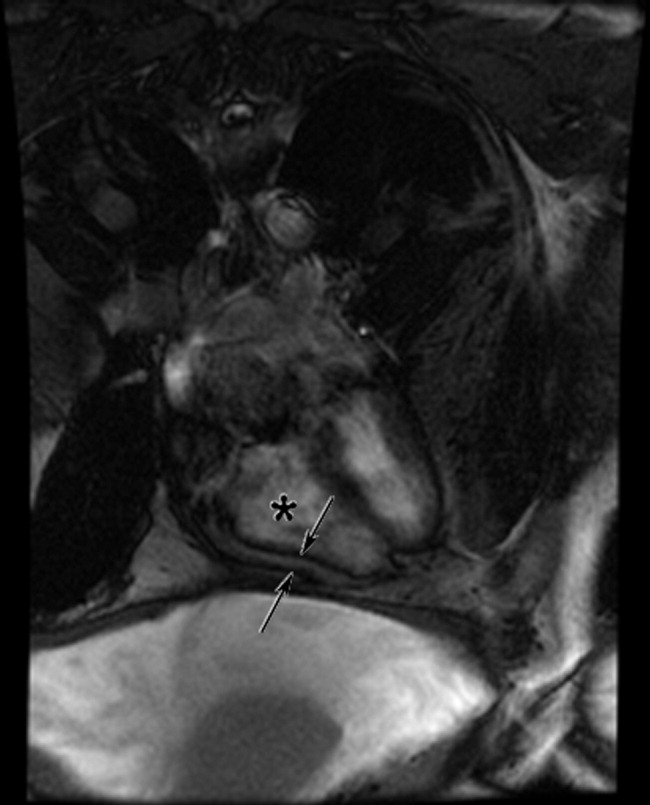

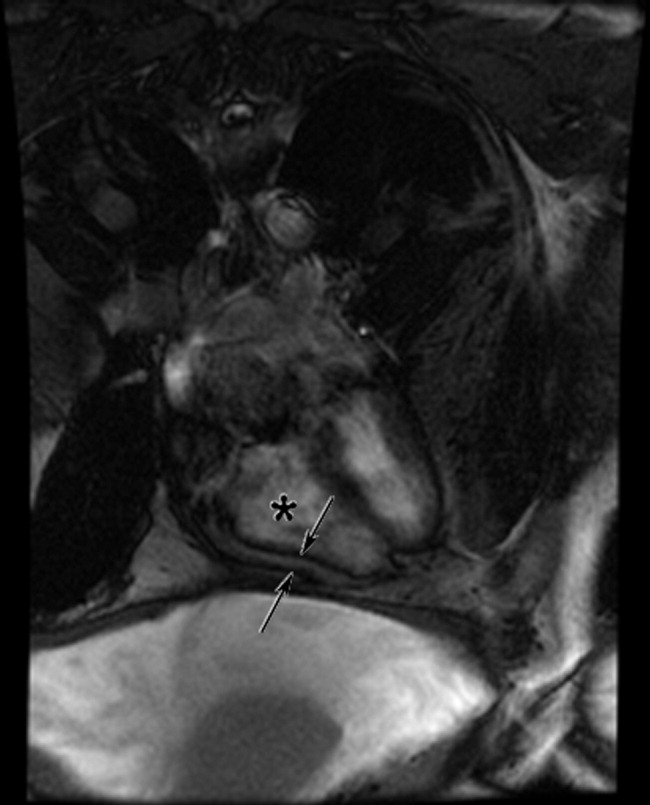

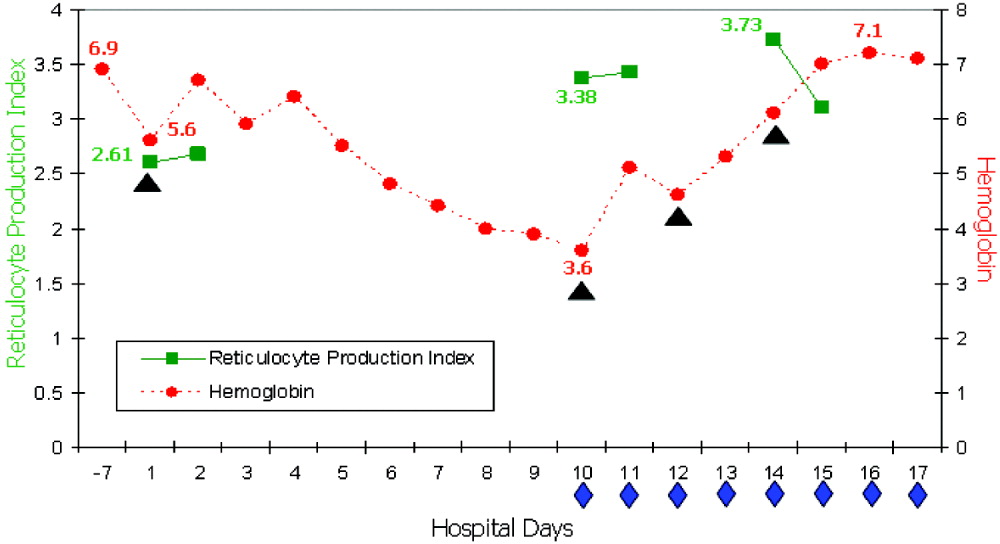

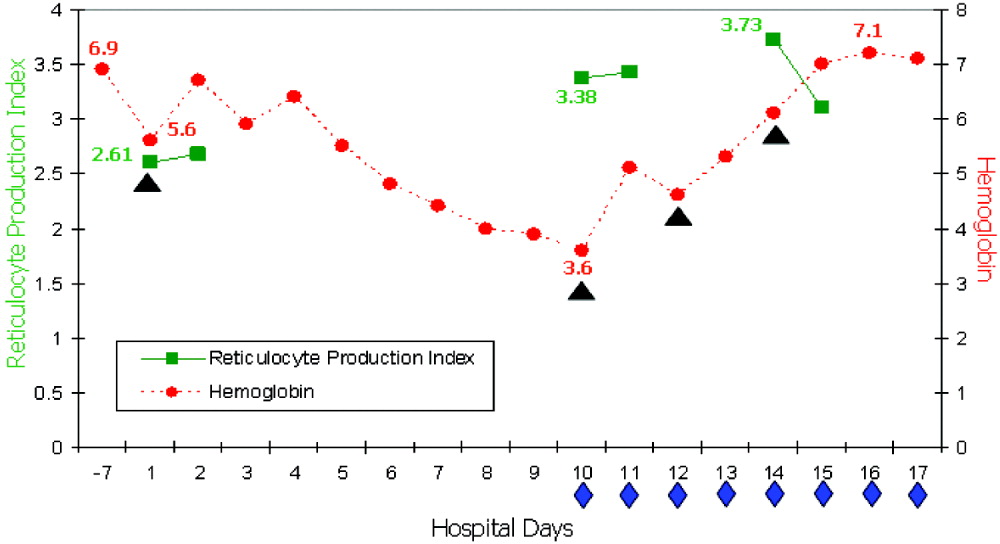

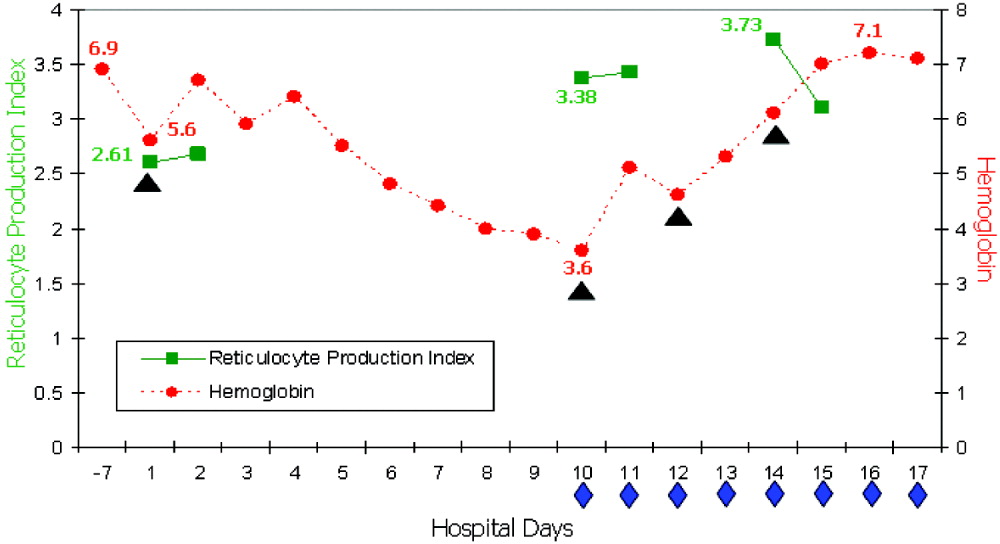

A 28‐year‐old man with sickle cell anemia was admitted with generalized pain. He noted an upper lip lesion 2 weeks prior to admission. He subsequently developed generalized pain in his legs, chest, and back typical of his pain crises. At admission he noted subjective fevers without chills for a week. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 135/80, a pulse of 81, a respiratory rate of 16, and an initial temperature of 37.7C. On examination he had scleral icterus and a large upper lip ulcer (Fig. 1). His hospital course was complicated by persistent fevers, a hepatic sequestration crisis, persistent hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion, and ultimately the identification of iris‐shaped targetoid lesions on the palms (Fig. 2).These lesions were believed to be consistent with erythema multiforme (EM) secondary to his recent HSV labialis, confirmed by a herpes culture. The patient recovered uneventfully after a 10‐day hospitalization. Erythema multiforme is an acute, self‐limited, but sometimes recurrent dermatologic condition considered to be a distinct hypersensitivity reaction.1 It is associated with certain infections such as herpes simplex 1 and 2, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal infections, and a number of medications in the classes barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, penicillins, hydantoins, phenothiazines, and sulfonamides.2 EM is diagnosed clinically by the characteristic rash on the hands and feet, with some cases involving the oral cavity. Treatment is typically focused on resolving the underlying infection or removing the offending drug. Dermatologic manifestations usually improve over 3‐5 weeks without residual sequelae.

- ,,.Understanding the pathogenesis of HSV‐associated erythema multiforme.Dermatology.1998;197:219–222.

- ,,.Erythema multiforme.Am Fam Physician.2006;74:1883–1888.

A 28‐year‐old man with sickle cell anemia was admitted with generalized pain. He noted an upper lip lesion 2 weeks prior to admission. He subsequently developed generalized pain in his legs, chest, and back typical of his pain crises. At admission he noted subjective fevers without chills for a week. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 135/80, a pulse of 81, a respiratory rate of 16, and an initial temperature of 37.7C. On examination he had scleral icterus and a large upper lip ulcer (Fig. 1). His hospital course was complicated by persistent fevers, a hepatic sequestration crisis, persistent hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion, and ultimately the identification of iris‐shaped targetoid lesions on the palms (Fig. 2).These lesions were believed to be consistent with erythema multiforme (EM) secondary to his recent HSV labialis, confirmed by a herpes culture. The patient recovered uneventfully after a 10‐day hospitalization. Erythema multiforme is an acute, self‐limited, but sometimes recurrent dermatologic condition considered to be a distinct hypersensitivity reaction.1 It is associated with certain infections such as herpes simplex 1 and 2, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal infections, and a number of medications in the classes barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, penicillins, hydantoins, phenothiazines, and sulfonamides.2 EM is diagnosed clinically by the characteristic rash on the hands and feet, with some cases involving the oral cavity. Treatment is typically focused on resolving the underlying infection or removing the offending drug. Dermatologic manifestations usually improve over 3‐5 weeks without residual sequelae.

A 28‐year‐old man with sickle cell anemia was admitted with generalized pain. He noted an upper lip lesion 2 weeks prior to admission. He subsequently developed generalized pain in his legs, chest, and back typical of his pain crises. At admission he noted subjective fevers without chills for a week. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 135/80, a pulse of 81, a respiratory rate of 16, and an initial temperature of 37.7C. On examination he had scleral icterus and a large upper lip ulcer (Fig. 1). His hospital course was complicated by persistent fevers, a hepatic sequestration crisis, persistent hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion, and ultimately the identification of iris‐shaped targetoid lesions on the palms (Fig. 2).These lesions were believed to be consistent with erythema multiforme (EM) secondary to his recent HSV labialis, confirmed by a herpes culture. The patient recovered uneventfully after a 10‐day hospitalization. Erythema multiforme is an acute, self‐limited, but sometimes recurrent dermatologic condition considered to be a distinct hypersensitivity reaction.1 It is associated with certain infections such as herpes simplex 1 and 2, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal infections, and a number of medications in the classes barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, penicillins, hydantoins, phenothiazines, and sulfonamides.2 EM is diagnosed clinically by the characteristic rash on the hands and feet, with some cases involving the oral cavity. Treatment is typically focused on resolving the underlying infection or removing the offending drug. Dermatologic manifestations usually improve over 3‐5 weeks without residual sequelae.

- ,,.Understanding the pathogenesis of HSV‐associated erythema multiforme.Dermatology.1998;197:219–222.

- ,,.Erythema multiforme.Am Fam Physician.2006;74:1883–1888.

- ,,.Understanding the pathogenesis of HSV‐associated erythema multiforme.Dermatology.1998;197:219–222.

- ,,.Erythema multiforme.Am Fam Physician.2006;74:1883–1888.

Patients' Predilections Regarding Informed Consent

The cornerstones of American medical ethics include respect for patient autonomy and beneficence. Although informed consent is required for surgical procedures and transfusion of blood products, the overwhelming majority of medical treatments administered by physicians to hospitalized patients are given without discussing risks, benefits, and alternatives. Although patients may sign a general permission‐to‐treat form on admission to the hospital, informed consent for medical treatments is generally ad hoc, and there are no national standards or mandates. We hypothesized that given the choice, hospitalized patients would want to participate in informed decision making, especially for therapies associated with substantial risks and benefits.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of Bridgeport Hospital approved this study. Each day between June and August 2006, the hospital's admitting department provided investigators with a list that included names and locations of all patients admitted to the Department of Medicine inpatient service. All the patients were eligible for participation in the study. Patients were excluded if they were in a comatose state, were encephalopathic, or were judged to be severely demented. In addition, patients were assessed during the scripted intervention to ascertain whether they had the capacity to make informed decisions based on their ability: (a) to understand the presented information, (b) to consider the information in relation to their personal values, and (c) to communicate their wishes. If personnel doubted an individual's capacity in any of these 3 areas, they were not included in the study.

Study personnel read directly from the script (see Appendix) and recorded answers. Study personnel were permitted to reread questions but did not provide additional guidance beyond the questionnaire. Patients whose primary language was not English were interviewed through in‐house or 3‐way telephone (remote) translators.

Statistical analyses included the chi‐square test to examine responses across the 3 categories of answers (ie, always consent, qualified consent, waive consent) and simple comparisons of percentages. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 634 patients were admitted to the medicine service during the study period June‐August 2006. Of these, 158 were judged to lack sufficient capacity by study personnel and were excluded from the study. Ninety‐five refused to participate, and 171 were discharged before the questionnaire could be administered. Two hundred and ten patients answered the questionnaire. They ranged in age from 18 to 96 years (mean age standard error, 63.3 1.1 years). One hundred and three (49%) were men, and 107 (51%) were women. A majority (67.5%) were white, 20% (42) were African American, and 11.9% (25) were Hispanic. Most (87.6%) had at least a high school education, and 35% had a college‐/graduate‐level education. Sixty‐seven percent had at least 2 comorbid conditions in addition to their principal reason for hospitalization. Their average acute physiology and chronic health care evaluation (APACHE II) score was 7.5 0.3 (median 7; range 0‐22).

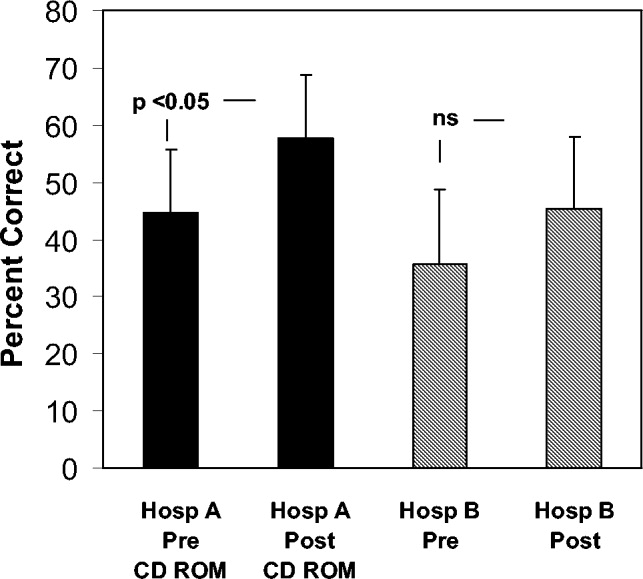

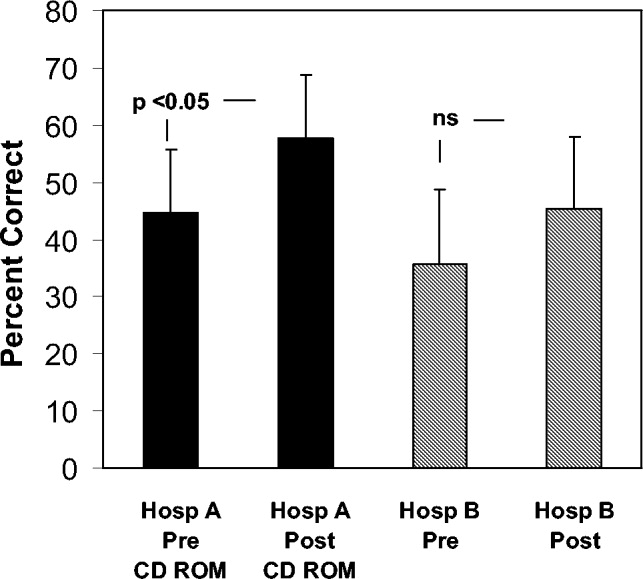

Figure 1 shows the distribution of answers to each of the 4 questions.

Question 1: Permission for Administration of Diuretics

One hundred and ninety‐three patients (92%) wished to participate in choosing whether to receive diuretics for congestive heart failure (CHF). Of these, 58 (28%) wanted their treating physicians to obtain their permission no matter what, even if there was an acute matter of life and death. One hundred and thirty‐five (64%) wanted to be able to give permission if time allowed. Only 8% thought doctors should just give diuretics for CHF without seeking permission.

The pattern of response did not differ by sex, race, number of comorbid conditions, or primary admission diagnosis. Age (>65 vs. <65 years) was significantly associated with predilections to waive permission for administration of diuretics (Pearson chi‐square test P = .01). For example, 36.9% of the younger patients (<65 years) wanted to be consulted under all circumstances compared with only 18.7% of the more elderly patients (P = .004).

Question 2: Permission for Potassium Replacement

Overall, 178 patients (85%) wished to participate in decision making regarding potassium supplementation, and 51 (24%) wanted the managing physicians to obtain their permission no matter what, even if there was an acute matter of life and death. One hundred and twenty‐seven patients (61%) responded that they would like to be able to give permission if time allowed. Only 15% thought doctors should just give potassium replacement without seeking their permission. Similar to the responses to diuretic replacement, the pattern of responses differed by age but not by sex, race, level of education, or number of comorbid conditions. Thirty‐one percent of the younger patients wanted to give permission at all times compared with 17.8% of the older patients (P = .03).

Question 3: Permission for Thrombolysis of Pulmonary Embolus if Risk of Cerebral Bleed Was Less Than 5%

If the risk of cerebral hemorrhage was less than 5%, only 15 patients (7%) thought it should be given without seeking their permission. A third of the younger patients compared with 24.5% of the elderly patients would want to be consulted for their permission at all times (P = .18). The pattern of responses also did not differ by sex, race or level of education.

Question 4: Permission for Thrombolysis of Pulmonary Embolus if Risk of Cerebral Bleed Was Greater Than 20%

Overall, 85 patients (40.8%) would want a discussion and their permission no matter what prior to initiating high‐risk thrombolysis. One hundred and thirteen patients (54%) would want to be able to give permission if time allowed. This pattern of response differed by level of education and by age. Forty‐four percent of those with at least a high school education would want to give permission compared with 19% of those without a high school education (P = .016). Four percent of those with at least a high school education would yield the need for permission at all times compared with 11.5% of those without a high school education (P = .09). Only 1 elderly patient (0.9%) would waive the need for permission at all times compared with 9 younger patients (8.7%; P = .01).

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study is that most medical patients prefer to participate in making decisions about their medical care during acute hospitalization, even for relatively low‐risk treatments like potassium supplementation and administration of diuretics. Very few patients were prepared to waive consent and grant their physicians the absolute right to administer therapies such as thrombolysis, even if the risk of bleeding was estimated to be less than 5%. Whereas the elderly patients were less likely to prefer being asked to consent to treatments than were younger patients, most would want to be informed of even trivial therapies if time allowed.

In some situations older patients (65 years old) were more likely than younger patients (<65 years old) to allow their physicians to make unilateral decisions regarding their health care. This could be explained by those age 65 and older having grown up when physician paternalism was more prevalent in American medicine. In the 1970s physician paternalism waned, and respect for patient autonomy emerged as the dominant physicianpatient model. Patients who became adults after 1970 know only this relationship with their physician, and so it makes sense that they would be more inclined to prefer a participatory model.

These data complement and extend a series of studies we conducted with patients admitted to Bridgeport Hospital. Our data suggest that our patients wish to consent for end‐of‐life decisions,1, 2 invasive procedures,3 and, now, to be apprised of medical therapies administered during hospitalization. At the same time, we have found that consent practices at many centers are not consistent with these patient predilections.1, 2, 4 Our study suffered from having a small sample size obtained in one geographic location; so results should be generalized cautiously. Nonetheless, insofar as the expectations of patients for participation are not being met by the health care system in Connecticut (and we suspect elsewhere), clinicians, hospital administrators, and health care policy makers might consider whether more rigorous and explicit consent practices and policies are required. Another important limitation of the study was that patients included may not have entirely understood the implications of their answers (ie, how cumbersome to the system and bothersome to the patient seeking consent for every therapy could become). In fact, we cannot be certain that all patients truly understood the questions, some of which were complex. Nonetheless, these results support that considered in the abstract, most patients prefer to consent for medical therapies. Had the implications for safety and expediency been explained in detail, it is possible that patients would have waived the need to give consent for treatments with minimal risk. The questionnaire also presents an abbreviated list of risks and benefits for each intervention, and although it refers to the formal process of informed consent in its preamble, it uses terminology (ie, permission) that may not reflect the complexity of informed consent. Nonetheless, our goal was to examine the degree to which patients wished to participate in their medical decision making. Notwithstanding these weaknesses of the survey instrument, the data suggest patients want to be in the loop whenever possible.

There are no national standards of consent for medical treatments. The Veterans' Administration, which has led the way in many areas of patients' rights, has a policy:

Treatments and Procedures That Do Not Require Signature Consent. Treatments and procedures that are low risk and are within broadly accepted standards of medical practice (e.g., administration of most drugs or for the performance of minor procedures such as routine X‐rays) do not require signature consent. However, the informed consent process must be documented in the medical record.

Compliance with this standard (ie, consent for every new medication) is not routine in most acute care hospitals. Although some clinicians obtain formal consent for high‐risk therapies (perhaps out of respect for autonomy, perhaps to reduce medical‐legal liability), there are no explicit decision rules to guide clinicians regarding for which treatments they should obtain formal consent. Accordingly, some might obtain formal consent for thrombolysis for massive pulmonary embolus, and others might not. It is not clear that the consent‐to‐treat form signed during hospital admission would legally cover all medical therapies during hospitalization. The legal standard for informed consent is what any reasonable patient would want to consent for. Our data suggest that most reasonable patients wish to at least assent and perhaps consent for much of what they receive during hospitalization. Although we have been unable to find case law predicated entirely on failure to obtain consent prior to administration of a therapy that caused a complication, it is plausible that the reasonable patient standard could be used in this manner. Regardless, it is impractical to require consent for the thousands of medical therapies administered each day in hospitals. Requiring consent for all therapies, if respected rigidly, would threaten the safety and efficiency of American hospitals. Naturally, a balance betweem respect for autonomy, that is, informed consent for the riskiest therapies, and efficiency is necessary. Explicit guidelines issued by accrediting agencies or the federal government would be helpful. The rules for consent (and/or assent) should be more explicit and less arbitrary, that is, determined independently by each clinician.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that when considered in the abstract, that is, without explaining the logistical hurdles that it would create, inpatients wish to participate in decision making for both low‐ and high‐risk treatments. Clinicians are faced with demands and obligations that preclude full consent for the myriad low‐risk treatments administered daily to hospitalized patients. Some treatments are likely to be covered implicitly under the general consent‐to‐treat process and paperwork. Nonetheless, clinicians should consider explaining the principal risks and benefits of moderate‐risk treatments in order to secure informed assent. Full informed consent may be most appropriate for very high‐risk therapies. Patients expect and deserve frequent communication with caregivers that balances their safety with their right to self‐determination.

APPENDIX

QUESTIONNAIRE

Good morning/afternoon/evening. My name is Dr. _____________, and I am working with Dr. Constantine Manthous in a study to determine what patients want to know about their treatments during hospitalization. The research will not effect your care in any way, and if it is published, your confidential medical information will be protected and will not be mentioned in any publications. In fact, the questions I will ask do not apply to your care plans but are what ifs to find out for what kinds of treatments patients' want to provide permission called informed consent. Informed consent is when a doctor explains a treatment or procedure to the patient, including its risks, benefits, and alternatives, and asks permission before doing it. Are you feeling up to answering 4 questions that should take about 5‐10 minutes? Thank you.

Again, these questions do not apply to your illness or treatments.

If you had fluid on your lungs, a medicine called a diuretic could be given to make you pass more urine to help get the fluid out of the lungs. The benefits are that it can help you breathe easier. The risks are that it will make you have to urinate more often (>50%), and sometimes minerals in the blood get low and can cause the heart to beat abnormally (<1%) if enough replacement minerals aren't given to keep up with losses in the urine. The alternative to receiving this medicine would be not to receive it, which risks continued shortness of breath, and rarely (<5%) untreated patients may need a breathing machine to help breathing. Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed this treatment, the doctor should give it to me without asking my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give it. But if there were time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed this treatment, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

When a diuretic is given, minerals in the blood can be lost in the urine. If the minerals in the blood get too low, the heart can have abnormal beats that are rarely (<1%) life‐threatening. Doctors can give replacement minerals. The risks of replacement are minimal, and the alternative is not to give the minerals, risking abnormal heartbeats. Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed replacement minerals, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give me the minerals. But if there was time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed replacement minerals, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

During hospitalization, sometimes blood clots can form in the legs and travel to the lungs. Very rarely (<1%), the blood clots can cause shortness of breath and the blood pressure to drop to a dangerous level. In this case there is a medicine called tpa that can dissolve the blood clot. It almost always dissolves the clot, improves breathlessness, and improves heart function. But there is a small risk (<5%) that it can cause serious bleeding into the brain (called a stroke). Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed tpa for life‐threatening blood clots, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give the tpa. But if there was time and I was able, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed tpa for life‐threatening blood clots, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

In the previous example, what if the serious brain bleeding from the clot‐busting drug happened in more than 20% of cases, which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed this treatment, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give it. But if there was time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed this treatment, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

- ,,,,.Patient, physician and family member understanding of living wills.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2002;166:1430–1435.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalized patients want to choose whether to receive life‐sustaining therapies.J Hosp Med.2006;1:161–167.

- ,,,,,.Informed consent for invasive medical procedures. From the patient's perspective.Conn Med.2003;67:529–533.

- ,,,.Informed consent for medical procedures: Local and national practices.Chest.2003;124:1978–1984.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA informed consent for clinical treatments and procedures. 2003. Available at: http://www.va.gov/ETHICS/docs/policy/VHA_Handbook_1004‐1_Informed_Consent_Policy_20030129.pdf. Accessed September 5,2006.

The cornerstones of American medical ethics include respect for patient autonomy and beneficence. Although informed consent is required for surgical procedures and transfusion of blood products, the overwhelming majority of medical treatments administered by physicians to hospitalized patients are given without discussing risks, benefits, and alternatives. Although patients may sign a general permission‐to‐treat form on admission to the hospital, informed consent for medical treatments is generally ad hoc, and there are no national standards or mandates. We hypothesized that given the choice, hospitalized patients would want to participate in informed decision making, especially for therapies associated with substantial risks and benefits.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of Bridgeport Hospital approved this study. Each day between June and August 2006, the hospital's admitting department provided investigators with a list that included names and locations of all patients admitted to the Department of Medicine inpatient service. All the patients were eligible for participation in the study. Patients were excluded if they were in a comatose state, were encephalopathic, or were judged to be severely demented. In addition, patients were assessed during the scripted intervention to ascertain whether they had the capacity to make informed decisions based on their ability: (a) to understand the presented information, (b) to consider the information in relation to their personal values, and (c) to communicate their wishes. If personnel doubted an individual's capacity in any of these 3 areas, they were not included in the study.

Study personnel read directly from the script (see Appendix) and recorded answers. Study personnel were permitted to reread questions but did not provide additional guidance beyond the questionnaire. Patients whose primary language was not English were interviewed through in‐house or 3‐way telephone (remote) translators.

Statistical analyses included the chi‐square test to examine responses across the 3 categories of answers (ie, always consent, qualified consent, waive consent) and simple comparisons of percentages. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 634 patients were admitted to the medicine service during the study period June‐August 2006. Of these, 158 were judged to lack sufficient capacity by study personnel and were excluded from the study. Ninety‐five refused to participate, and 171 were discharged before the questionnaire could be administered. Two hundred and ten patients answered the questionnaire. They ranged in age from 18 to 96 years (mean age standard error, 63.3 1.1 years). One hundred and three (49%) were men, and 107 (51%) were women. A majority (67.5%) were white, 20% (42) were African American, and 11.9% (25) were Hispanic. Most (87.6%) had at least a high school education, and 35% had a college‐/graduate‐level education. Sixty‐seven percent had at least 2 comorbid conditions in addition to their principal reason for hospitalization. Their average acute physiology and chronic health care evaluation (APACHE II) score was 7.5 0.3 (median 7; range 0‐22).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of answers to each of the 4 questions.

Question 1: Permission for Administration of Diuretics

One hundred and ninety‐three patients (92%) wished to participate in choosing whether to receive diuretics for congestive heart failure (CHF). Of these, 58 (28%) wanted their treating physicians to obtain their permission no matter what, even if there was an acute matter of life and death. One hundred and thirty‐five (64%) wanted to be able to give permission if time allowed. Only 8% thought doctors should just give diuretics for CHF without seeking permission.

The pattern of response did not differ by sex, race, number of comorbid conditions, or primary admission diagnosis. Age (>65 vs. <65 years) was significantly associated with predilections to waive permission for administration of diuretics (Pearson chi‐square test P = .01). For example, 36.9% of the younger patients (<65 years) wanted to be consulted under all circumstances compared with only 18.7% of the more elderly patients (P = .004).

Question 2: Permission for Potassium Replacement

Overall, 178 patients (85%) wished to participate in decision making regarding potassium supplementation, and 51 (24%) wanted the managing physicians to obtain their permission no matter what, even if there was an acute matter of life and death. One hundred and twenty‐seven patients (61%) responded that they would like to be able to give permission if time allowed. Only 15% thought doctors should just give potassium replacement without seeking their permission. Similar to the responses to diuretic replacement, the pattern of responses differed by age but not by sex, race, level of education, or number of comorbid conditions. Thirty‐one percent of the younger patients wanted to give permission at all times compared with 17.8% of the older patients (P = .03).

Question 3: Permission for Thrombolysis of Pulmonary Embolus if Risk of Cerebral Bleed Was Less Than 5%

If the risk of cerebral hemorrhage was less than 5%, only 15 patients (7%) thought it should be given without seeking their permission. A third of the younger patients compared with 24.5% of the elderly patients would want to be consulted for their permission at all times (P = .18). The pattern of responses also did not differ by sex, race or level of education.

Question 4: Permission for Thrombolysis of Pulmonary Embolus if Risk of Cerebral Bleed Was Greater Than 20%

Overall, 85 patients (40.8%) would want a discussion and their permission no matter what prior to initiating high‐risk thrombolysis. One hundred and thirteen patients (54%) would want to be able to give permission if time allowed. This pattern of response differed by level of education and by age. Forty‐four percent of those with at least a high school education would want to give permission compared with 19% of those without a high school education (P = .016). Four percent of those with at least a high school education would yield the need for permission at all times compared with 11.5% of those without a high school education (P = .09). Only 1 elderly patient (0.9%) would waive the need for permission at all times compared with 9 younger patients (8.7%; P = .01).

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study is that most medical patients prefer to participate in making decisions about their medical care during acute hospitalization, even for relatively low‐risk treatments like potassium supplementation and administration of diuretics. Very few patients were prepared to waive consent and grant their physicians the absolute right to administer therapies such as thrombolysis, even if the risk of bleeding was estimated to be less than 5%. Whereas the elderly patients were less likely to prefer being asked to consent to treatments than were younger patients, most would want to be informed of even trivial therapies if time allowed.

In some situations older patients (65 years old) were more likely than younger patients (<65 years old) to allow their physicians to make unilateral decisions regarding their health care. This could be explained by those age 65 and older having grown up when physician paternalism was more prevalent in American medicine. In the 1970s physician paternalism waned, and respect for patient autonomy emerged as the dominant physicianpatient model. Patients who became adults after 1970 know only this relationship with their physician, and so it makes sense that they would be more inclined to prefer a participatory model.

These data complement and extend a series of studies we conducted with patients admitted to Bridgeport Hospital. Our data suggest that our patients wish to consent for end‐of‐life decisions,1, 2 invasive procedures,3 and, now, to be apprised of medical therapies administered during hospitalization. At the same time, we have found that consent practices at many centers are not consistent with these patient predilections.1, 2, 4 Our study suffered from having a small sample size obtained in one geographic location; so results should be generalized cautiously. Nonetheless, insofar as the expectations of patients for participation are not being met by the health care system in Connecticut (and we suspect elsewhere), clinicians, hospital administrators, and health care policy makers might consider whether more rigorous and explicit consent practices and policies are required. Another important limitation of the study was that patients included may not have entirely understood the implications of their answers (ie, how cumbersome to the system and bothersome to the patient seeking consent for every therapy could become). In fact, we cannot be certain that all patients truly understood the questions, some of which were complex. Nonetheless, these results support that considered in the abstract, most patients prefer to consent for medical therapies. Had the implications for safety and expediency been explained in detail, it is possible that patients would have waived the need to give consent for treatments with minimal risk. The questionnaire also presents an abbreviated list of risks and benefits for each intervention, and although it refers to the formal process of informed consent in its preamble, it uses terminology (ie, permission) that may not reflect the complexity of informed consent. Nonetheless, our goal was to examine the degree to which patients wished to participate in their medical decision making. Notwithstanding these weaknesses of the survey instrument, the data suggest patients want to be in the loop whenever possible.

There are no national standards of consent for medical treatments. The Veterans' Administration, which has led the way in many areas of patients' rights, has a policy:

Treatments and Procedures That Do Not Require Signature Consent. Treatments and procedures that are low risk and are within broadly accepted standards of medical practice (e.g., administration of most drugs or for the performance of minor procedures such as routine X‐rays) do not require signature consent. However, the informed consent process must be documented in the medical record.

Compliance with this standard (ie, consent for every new medication) is not routine in most acute care hospitals. Although some clinicians obtain formal consent for high‐risk therapies (perhaps out of respect for autonomy, perhaps to reduce medical‐legal liability), there are no explicit decision rules to guide clinicians regarding for which treatments they should obtain formal consent. Accordingly, some might obtain formal consent for thrombolysis for massive pulmonary embolus, and others might not. It is not clear that the consent‐to‐treat form signed during hospital admission would legally cover all medical therapies during hospitalization. The legal standard for informed consent is what any reasonable patient would want to consent for. Our data suggest that most reasonable patients wish to at least assent and perhaps consent for much of what they receive during hospitalization. Although we have been unable to find case law predicated entirely on failure to obtain consent prior to administration of a therapy that caused a complication, it is plausible that the reasonable patient standard could be used in this manner. Regardless, it is impractical to require consent for the thousands of medical therapies administered each day in hospitals. Requiring consent for all therapies, if respected rigidly, would threaten the safety and efficiency of American hospitals. Naturally, a balance betweem respect for autonomy, that is, informed consent for the riskiest therapies, and efficiency is necessary. Explicit guidelines issued by accrediting agencies or the federal government would be helpful. The rules for consent (and/or assent) should be more explicit and less arbitrary, that is, determined independently by each clinician.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that when considered in the abstract, that is, without explaining the logistical hurdles that it would create, inpatients wish to participate in decision making for both low‐ and high‐risk treatments. Clinicians are faced with demands and obligations that preclude full consent for the myriad low‐risk treatments administered daily to hospitalized patients. Some treatments are likely to be covered implicitly under the general consent‐to‐treat process and paperwork. Nonetheless, clinicians should consider explaining the principal risks and benefits of moderate‐risk treatments in order to secure informed assent. Full informed consent may be most appropriate for very high‐risk therapies. Patients expect and deserve frequent communication with caregivers that balances their safety with their right to self‐determination.

APPENDIX

QUESTIONNAIRE

Good morning/afternoon/evening. My name is Dr. _____________, and I am working with Dr. Constantine Manthous in a study to determine what patients want to know about their treatments during hospitalization. The research will not effect your care in any way, and if it is published, your confidential medical information will be protected and will not be mentioned in any publications. In fact, the questions I will ask do not apply to your care plans but are what ifs to find out for what kinds of treatments patients' want to provide permission called informed consent. Informed consent is when a doctor explains a treatment or procedure to the patient, including its risks, benefits, and alternatives, and asks permission before doing it. Are you feeling up to answering 4 questions that should take about 5‐10 minutes? Thank you.

Again, these questions do not apply to your illness or treatments.

If you had fluid on your lungs, a medicine called a diuretic could be given to make you pass more urine to help get the fluid out of the lungs. The benefits are that it can help you breathe easier. The risks are that it will make you have to urinate more often (>50%), and sometimes minerals in the blood get low and can cause the heart to beat abnormally (<1%) if enough replacement minerals aren't given to keep up with losses in the urine. The alternative to receiving this medicine would be not to receive it, which risks continued shortness of breath, and rarely (<5%) untreated patients may need a breathing machine to help breathing. Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed this treatment, the doctor should give it to me without asking my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give it. But if there were time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed this treatment, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

When a diuretic is given, minerals in the blood can be lost in the urine. If the minerals in the blood get too low, the heart can have abnormal beats that are rarely (<1%) life‐threatening. Doctors can give replacement minerals. The risks of replacement are minimal, and the alternative is not to give the minerals, risking abnormal heartbeats. Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed replacement minerals, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give me the minerals. But if there was time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed replacement minerals, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

During hospitalization, sometimes blood clots can form in the legs and travel to the lungs. Very rarely (<1%), the blood clots can cause shortness of breath and the blood pressure to drop to a dangerous level. In this case there is a medicine called tpa that can dissolve the blood clot. It almost always dissolves the clot, improves breathlessness, and improves heart function. But there is a small risk (<5%) that it can cause serious bleeding into the brain (called a stroke). Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed tpa for life‐threatening blood clots, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give the tpa. But if there was time and I was able, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed tpa for life‐threatening blood clots, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

In the previous example, what if the serious brain bleeding from the clot‐busting drug happened in more than 20% of cases, which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed this treatment, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give it. But if there was time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed this treatment, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

The cornerstones of American medical ethics include respect for patient autonomy and beneficence. Although informed consent is required for surgical procedures and transfusion of blood products, the overwhelming majority of medical treatments administered by physicians to hospitalized patients are given without discussing risks, benefits, and alternatives. Although patients may sign a general permission‐to‐treat form on admission to the hospital, informed consent for medical treatments is generally ad hoc, and there are no national standards or mandates. We hypothesized that given the choice, hospitalized patients would want to participate in informed decision making, especially for therapies associated with substantial risks and benefits.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of Bridgeport Hospital approved this study. Each day between June and August 2006, the hospital's admitting department provided investigators with a list that included names and locations of all patients admitted to the Department of Medicine inpatient service. All the patients were eligible for participation in the study. Patients were excluded if they were in a comatose state, were encephalopathic, or were judged to be severely demented. In addition, patients were assessed during the scripted intervention to ascertain whether they had the capacity to make informed decisions based on their ability: (a) to understand the presented information, (b) to consider the information in relation to their personal values, and (c) to communicate their wishes. If personnel doubted an individual's capacity in any of these 3 areas, they were not included in the study.

Study personnel read directly from the script (see Appendix) and recorded answers. Study personnel were permitted to reread questions but did not provide additional guidance beyond the questionnaire. Patients whose primary language was not English were interviewed through in‐house or 3‐way telephone (remote) translators.

Statistical analyses included the chi‐square test to examine responses across the 3 categories of answers (ie, always consent, qualified consent, waive consent) and simple comparisons of percentages. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 634 patients were admitted to the medicine service during the study period June‐August 2006. Of these, 158 were judged to lack sufficient capacity by study personnel and were excluded from the study. Ninety‐five refused to participate, and 171 were discharged before the questionnaire could be administered. Two hundred and ten patients answered the questionnaire. They ranged in age from 18 to 96 years (mean age standard error, 63.3 1.1 years). One hundred and three (49%) were men, and 107 (51%) were women. A majority (67.5%) were white, 20% (42) were African American, and 11.9% (25) were Hispanic. Most (87.6%) had at least a high school education, and 35% had a college‐/graduate‐level education. Sixty‐seven percent had at least 2 comorbid conditions in addition to their principal reason for hospitalization. Their average acute physiology and chronic health care evaluation (APACHE II) score was 7.5 0.3 (median 7; range 0‐22).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of answers to each of the 4 questions.

Question 1: Permission for Administration of Diuretics

One hundred and ninety‐three patients (92%) wished to participate in choosing whether to receive diuretics for congestive heart failure (CHF). Of these, 58 (28%) wanted their treating physicians to obtain their permission no matter what, even if there was an acute matter of life and death. One hundred and thirty‐five (64%) wanted to be able to give permission if time allowed. Only 8% thought doctors should just give diuretics for CHF without seeking permission.

The pattern of response did not differ by sex, race, number of comorbid conditions, or primary admission diagnosis. Age (>65 vs. <65 years) was significantly associated with predilections to waive permission for administration of diuretics (Pearson chi‐square test P = .01). For example, 36.9% of the younger patients (<65 years) wanted to be consulted under all circumstances compared with only 18.7% of the more elderly patients (P = .004).

Question 2: Permission for Potassium Replacement

Overall, 178 patients (85%) wished to participate in decision making regarding potassium supplementation, and 51 (24%) wanted the managing physicians to obtain their permission no matter what, even if there was an acute matter of life and death. One hundred and twenty‐seven patients (61%) responded that they would like to be able to give permission if time allowed. Only 15% thought doctors should just give potassium replacement without seeking their permission. Similar to the responses to diuretic replacement, the pattern of responses differed by age but not by sex, race, level of education, or number of comorbid conditions. Thirty‐one percent of the younger patients wanted to give permission at all times compared with 17.8% of the older patients (P = .03).

Question 3: Permission for Thrombolysis of Pulmonary Embolus if Risk of Cerebral Bleed Was Less Than 5%

If the risk of cerebral hemorrhage was less than 5%, only 15 patients (7%) thought it should be given without seeking their permission. A third of the younger patients compared with 24.5% of the elderly patients would want to be consulted for their permission at all times (P = .18). The pattern of responses also did not differ by sex, race or level of education.

Question 4: Permission for Thrombolysis of Pulmonary Embolus if Risk of Cerebral Bleed Was Greater Than 20%

Overall, 85 patients (40.8%) would want a discussion and their permission no matter what prior to initiating high‐risk thrombolysis. One hundred and thirteen patients (54%) would want to be able to give permission if time allowed. This pattern of response differed by level of education and by age. Forty‐four percent of those with at least a high school education would want to give permission compared with 19% of those without a high school education (P = .016). Four percent of those with at least a high school education would yield the need for permission at all times compared with 11.5% of those without a high school education (P = .09). Only 1 elderly patient (0.9%) would waive the need for permission at all times compared with 9 younger patients (8.7%; P = .01).

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study is that most medical patients prefer to participate in making decisions about their medical care during acute hospitalization, even for relatively low‐risk treatments like potassium supplementation and administration of diuretics. Very few patients were prepared to waive consent and grant their physicians the absolute right to administer therapies such as thrombolysis, even if the risk of bleeding was estimated to be less than 5%. Whereas the elderly patients were less likely to prefer being asked to consent to treatments than were younger patients, most would want to be informed of even trivial therapies if time allowed.

In some situations older patients (65 years old) were more likely than younger patients (<65 years old) to allow their physicians to make unilateral decisions regarding their health care. This could be explained by those age 65 and older having grown up when physician paternalism was more prevalent in American medicine. In the 1970s physician paternalism waned, and respect for patient autonomy emerged as the dominant physicianpatient model. Patients who became adults after 1970 know only this relationship with their physician, and so it makes sense that they would be more inclined to prefer a participatory model.

These data complement and extend a series of studies we conducted with patients admitted to Bridgeport Hospital. Our data suggest that our patients wish to consent for end‐of‐life decisions,1, 2 invasive procedures,3 and, now, to be apprised of medical therapies administered during hospitalization. At the same time, we have found that consent practices at many centers are not consistent with these patient predilections.1, 2, 4 Our study suffered from having a small sample size obtained in one geographic location; so results should be generalized cautiously. Nonetheless, insofar as the expectations of patients for participation are not being met by the health care system in Connecticut (and we suspect elsewhere), clinicians, hospital administrators, and health care policy makers might consider whether more rigorous and explicit consent practices and policies are required. Another important limitation of the study was that patients included may not have entirely understood the implications of their answers (ie, how cumbersome to the system and bothersome to the patient seeking consent for every therapy could become). In fact, we cannot be certain that all patients truly understood the questions, some of which were complex. Nonetheless, these results support that considered in the abstract, most patients prefer to consent for medical therapies. Had the implications for safety and expediency been explained in detail, it is possible that patients would have waived the need to give consent for treatments with minimal risk. The questionnaire also presents an abbreviated list of risks and benefits for each intervention, and although it refers to the formal process of informed consent in its preamble, it uses terminology (ie, permission) that may not reflect the complexity of informed consent. Nonetheless, our goal was to examine the degree to which patients wished to participate in their medical decision making. Notwithstanding these weaknesses of the survey instrument, the data suggest patients want to be in the loop whenever possible.

There are no national standards of consent for medical treatments. The Veterans' Administration, which has led the way in many areas of patients' rights, has a policy:

Treatments and Procedures That Do Not Require Signature Consent. Treatments and procedures that are low risk and are within broadly accepted standards of medical practice (e.g., administration of most drugs or for the performance of minor procedures such as routine X‐rays) do not require signature consent. However, the informed consent process must be documented in the medical record.

Compliance with this standard (ie, consent for every new medication) is not routine in most acute care hospitals. Although some clinicians obtain formal consent for high‐risk therapies (perhaps out of respect for autonomy, perhaps to reduce medical‐legal liability), there are no explicit decision rules to guide clinicians regarding for which treatments they should obtain formal consent. Accordingly, some might obtain formal consent for thrombolysis for massive pulmonary embolus, and others might not. It is not clear that the consent‐to‐treat form signed during hospital admission would legally cover all medical therapies during hospitalization. The legal standard for informed consent is what any reasonable patient would want to consent for. Our data suggest that most reasonable patients wish to at least assent and perhaps consent for much of what they receive during hospitalization. Although we have been unable to find case law predicated entirely on failure to obtain consent prior to administration of a therapy that caused a complication, it is plausible that the reasonable patient standard could be used in this manner. Regardless, it is impractical to require consent for the thousands of medical therapies administered each day in hospitals. Requiring consent for all therapies, if respected rigidly, would threaten the safety and efficiency of American hospitals. Naturally, a balance betweem respect for autonomy, that is, informed consent for the riskiest therapies, and efficiency is necessary. Explicit guidelines issued by accrediting agencies or the federal government would be helpful. The rules for consent (and/or assent) should be more explicit and less arbitrary, that is, determined independently by each clinician.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that when considered in the abstract, that is, without explaining the logistical hurdles that it would create, inpatients wish to participate in decision making for both low‐ and high‐risk treatments. Clinicians are faced with demands and obligations that preclude full consent for the myriad low‐risk treatments administered daily to hospitalized patients. Some treatments are likely to be covered implicitly under the general consent‐to‐treat process and paperwork. Nonetheless, clinicians should consider explaining the principal risks and benefits of moderate‐risk treatments in order to secure informed assent. Full informed consent may be most appropriate for very high‐risk therapies. Patients expect and deserve frequent communication with caregivers that balances their safety with their right to self‐determination.

APPENDIX

QUESTIONNAIRE

Good morning/afternoon/evening. My name is Dr. _____________, and I am working with Dr. Constantine Manthous in a study to determine what patients want to know about their treatments during hospitalization. The research will not effect your care in any way, and if it is published, your confidential medical information will be protected and will not be mentioned in any publications. In fact, the questions I will ask do not apply to your care plans but are what ifs to find out for what kinds of treatments patients' want to provide permission called informed consent. Informed consent is when a doctor explains a treatment or procedure to the patient, including its risks, benefits, and alternatives, and asks permission before doing it. Are you feeling up to answering 4 questions that should take about 5‐10 minutes? Thank you.

Again, these questions do not apply to your illness or treatments.

If you had fluid on your lungs, a medicine called a diuretic could be given to make you pass more urine to help get the fluid out of the lungs. The benefits are that it can help you breathe easier. The risks are that it will make you have to urinate more often (>50%), and sometimes minerals in the blood get low and can cause the heart to beat abnormally (<1%) if enough replacement minerals aren't given to keep up with losses in the urine. The alternative to receiving this medicine would be not to receive it, which risks continued shortness of breath, and rarely (<5%) untreated patients may need a breathing machine to help breathing. Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed this treatment, the doctor should give it to me without asking my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give it. But if there were time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed this treatment, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

When a diuretic is given, minerals in the blood can be lost in the urine. If the minerals in the blood get too low, the heart can have abnormal beats that are rarely (<1%) life‐threatening. Doctors can give replacement minerals. The risks of replacement are minimal, and the alternative is not to give the minerals, risking abnormal heartbeats. Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed replacement minerals, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give me the minerals. But if there was time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed replacement minerals, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

During hospitalization, sometimes blood clots can form in the legs and travel to the lungs. Very rarely (<1%), the blood clots can cause shortness of breath and the blood pressure to drop to a dangerous level. In this case there is a medicine called tpa that can dissolve the blood clot. It almost always dissolves the clot, improves breathlessness, and improves heart function. But there is a small risk (<5%) that it can cause serious bleeding into the brain (called a stroke). Which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed tpa for life‐threatening blood clots, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give the tpa. But if there was time and I was able, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed tpa for life‐threatening blood clots, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

In the previous example, what if the serious brain bleeding from the clot‐busting drug happened in more than 20% of cases, which best summarizes your preference?

If I needed this treatment, the doctor should give it to me without needing my permission.

If it was a question of life or death and there wasn't enough time to talk it over, I'd want the doctor to just give it. But if there was time, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission.

If I needed this treatment, I'd want the doctor to talk it over with me first to get my permission no matter what.

- ,,,,.Patient, physician and family member understanding of living wills.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2002;166:1430–1435.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalized patients want to choose whether to receive life‐sustaining therapies.J Hosp Med.2006;1:161–167.

- ,,,,,.Informed consent for invasive medical procedures. From the patient's perspective.Conn Med.2003;67:529–533.

- ,,,.Informed consent for medical procedures: Local and national practices.Chest.2003;124:1978–1984.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA informed consent for clinical treatments and procedures. 2003. Available at: http://www.va.gov/ETHICS/docs/policy/VHA_Handbook_1004‐1_Informed_Consent_Policy_20030129.pdf. Accessed September 5,2006.

- ,,,,.Patient, physician and family member understanding of living wills.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2002;166:1430–1435.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalized patients want to choose whether to receive life‐sustaining therapies.J Hosp Med.2006;1:161–167.

- ,,,,,.Informed consent for invasive medical procedures. From the patient's perspective.Conn Med.2003;67:529–533.

- ,,,.Informed consent for medical procedures: Local and national practices.Chest.2003;124:1978–1984.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA informed consent for clinical treatments and procedures. 2003. Available at: http://www.va.gov/ETHICS/docs/policy/VHA_Handbook_1004‐1_Informed_Consent_Policy_20030129.pdf. Accessed September 5,2006.

Copyright © 2008 Society of Hospital Medicine

Editorial

We live in a moment of history where change is so speeded up that we begin to see the present only when it is already disappearing.

Two years ago we published the first issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine and declared, Our goal is that JHM become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.1 That first issue was just one of many steps toward this ambition. At the completion of its first year, JHM was selected for indexing and inclusion in the National Library of Medicine's Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), the primary component of PubMed. Following this huge step, we welcomed a remarkable increase in submissions and will have exceeded 300 in our second year, an approximately 50% increase from our first year!

As important, JHM quickly became a valuable benefit of membership in the Society of Hospital Medicine, and the innumerable compliments received by the staff reflect the diligent efforts of a remarkable editorial staff and work by our reviewers. With profound gratitude we list on page 86 these 325 reviewers who donated their priceless time and expertise to enhancing the quality of the manuscripts. To handle the marked increase in submissions, we are expanding and modifying our editorial staff. Please welcome Sunil Kripalani (Vanderbilt) and Daniel Brotman (Johns Hopkins), who join our previous six associate editors and all eight will now serve as JHM's deputy editors. Seven new associate editors also join our team. Among them, Tom Baudendistel (California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco), Eric Alper (UMass Memorial Health Care, Worcester), Brian Harte (Cleveland Clinic), and Rehan Qayyum (Johns Hopkins) will all focus on optimizing content for practicing hospitalists. Paul Aronowitz will continue to develop our Images section as an associate editor. Recognizing the growing number of pediatric hospitalists, Lisa Zauotis (Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia) and Erin Stucky (Children's Hospital San Diego) join JHM as the other 2 new associate editors. Finally, we welcome new Editorial Board members Mary C. Ottolini (Children's National Medical Center), Douglas Carlson (St. Louis Children's Hospital), and Daniel Rauch (NYU Children's Hospital). The welcome addition of these nationally recognized academicians prepares us for continued growth in manuscript submissions to JHM.

Although we could not excel without the editors, reviewers and our terrific new managing editor, Phaedra McGuinness, we would not survive without the authors who submit their manuscripts to JHMthey are responsible for the caliber of the journal, and we are immensely indebted to them. Originally, we hoped to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care,1 and fortunately this is now happening. Complementing hospitalists are nurses and pharmacists2 who recognize the importance of teamwork in the care of hospitalized patients. I encourage all members of the hospital care team to send us the results of their research, teaching, and quality improvement efforts.

As the specialty of hospital medicine continues to evolve, now with more than 20,000 hospitalists, JHM will develop with it. I am honored and grateful to collaborate with such a remarkable group of colleagues as we build the premier journal for the fastest growing specialty in the history of medicine in the United States. On to year 3!

P.S. Our tenuous hold on life confronted me this past Thanksgiving holiday. A fellow hospitalist and dear friend died unexpectedly. Two years before, he posted on the wall of the office shared with his colleagues the following quote:

What we do for ourselves fades, but what we do for another may be etched into eternity.

The smile and humanity of John Allen Garner (19632007) is etched into the lives of his family, many friends and colleagues, and innumerable grateful patients.

- .Hospital medicine's evolution—the next steps.J Hosp Med.2006;1:1–2.

- ,,, et al.ASHP–SHM joint statement on hospitalist–pharmacist collaboration.Am J Health‐Syst Pharm.2008;65:260–263.

We live in a moment of history where change is so speeded up that we begin to see the present only when it is already disappearing.

Two years ago we published the first issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine and declared, Our goal is that JHM become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.1 That first issue was just one of many steps toward this ambition. At the completion of its first year, JHM was selected for indexing and inclusion in the National Library of Medicine's Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), the primary component of PubMed. Following this huge step, we welcomed a remarkable increase in submissions and will have exceeded 300 in our second year, an approximately 50% increase from our first year!

As important, JHM quickly became a valuable benefit of membership in the Society of Hospital Medicine, and the innumerable compliments received by the staff reflect the diligent efforts of a remarkable editorial staff and work by our reviewers. With profound gratitude we list on page 86 these 325 reviewers who donated their priceless time and expertise to enhancing the quality of the manuscripts. To handle the marked increase in submissions, we are expanding and modifying our editorial staff. Please welcome Sunil Kripalani (Vanderbilt) and Daniel Brotman (Johns Hopkins), who join our previous six associate editors and all eight will now serve as JHM's deputy editors. Seven new associate editors also join our team. Among them, Tom Baudendistel (California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco), Eric Alper (UMass Memorial Health Care, Worcester), Brian Harte (Cleveland Clinic), and Rehan Qayyum (Johns Hopkins) will all focus on optimizing content for practicing hospitalists. Paul Aronowitz will continue to develop our Images section as an associate editor. Recognizing the growing number of pediatric hospitalists, Lisa Zauotis (Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia) and Erin Stucky (Children's Hospital San Diego) join JHM as the other 2 new associate editors. Finally, we welcome new Editorial Board members Mary C. Ottolini (Children's National Medical Center), Douglas Carlson (St. Louis Children's Hospital), and Daniel Rauch (NYU Children's Hospital). The welcome addition of these nationally recognized academicians prepares us for continued growth in manuscript submissions to JHM.

Although we could not excel without the editors, reviewers and our terrific new managing editor, Phaedra McGuinness, we would not survive without the authors who submit their manuscripts to JHMthey are responsible for the caliber of the journal, and we are immensely indebted to them. Originally, we hoped to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care,1 and fortunately this is now happening. Complementing hospitalists are nurses and pharmacists2 who recognize the importance of teamwork in the care of hospitalized patients. I encourage all members of the hospital care team to send us the results of their research, teaching, and quality improvement efforts.

As the specialty of hospital medicine continues to evolve, now with more than 20,000 hospitalists, JHM will develop with it. I am honored and grateful to collaborate with such a remarkable group of colleagues as we build the premier journal for the fastest growing specialty in the history of medicine in the United States. On to year 3!

P.S. Our tenuous hold on life confronted me this past Thanksgiving holiday. A fellow hospitalist and dear friend died unexpectedly. Two years before, he posted on the wall of the office shared with his colleagues the following quote:

What we do for ourselves fades, but what we do for another may be etched into eternity.

The smile and humanity of John Allen Garner (19632007) is etched into the lives of his family, many friends and colleagues, and innumerable grateful patients.

We live in a moment of history where change is so speeded up that we begin to see the present only when it is already disappearing.

Two years ago we published the first issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine and declared, Our goal is that JHM become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.1 That first issue was just one of many steps toward this ambition. At the completion of its first year, JHM was selected for indexing and inclusion in the National Library of Medicine's Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), the primary component of PubMed. Following this huge step, we welcomed a remarkable increase in submissions and will have exceeded 300 in our second year, an approximately 50% increase from our first year!

As important, JHM quickly became a valuable benefit of membership in the Society of Hospital Medicine, and the innumerable compliments received by the staff reflect the diligent efforts of a remarkable editorial staff and work by our reviewers. With profound gratitude we list on page 86 these 325 reviewers who donated their priceless time and expertise to enhancing the quality of the manuscripts. To handle the marked increase in submissions, we are expanding and modifying our editorial staff. Please welcome Sunil Kripalani (Vanderbilt) and Daniel Brotman (Johns Hopkins), who join our previous six associate editors and all eight will now serve as JHM's deputy editors. Seven new associate editors also join our team. Among them, Tom Baudendistel (California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco), Eric Alper (UMass Memorial Health Care, Worcester), Brian Harte (Cleveland Clinic), and Rehan Qayyum (Johns Hopkins) will all focus on optimizing content for practicing hospitalists. Paul Aronowitz will continue to develop our Images section as an associate editor. Recognizing the growing number of pediatric hospitalists, Lisa Zauotis (Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia) and Erin Stucky (Children's Hospital San Diego) join JHM as the other 2 new associate editors. Finally, we welcome new Editorial Board members Mary C. Ottolini (Children's National Medical Center), Douglas Carlson (St. Louis Children's Hospital), and Daniel Rauch (NYU Children's Hospital). The welcome addition of these nationally recognized academicians prepares us for continued growth in manuscript submissions to JHM.

Although we could not excel without the editors, reviewers and our terrific new managing editor, Phaedra McGuinness, we would not survive without the authors who submit their manuscripts to JHMthey are responsible for the caliber of the journal, and we are immensely indebted to them. Originally, we hoped to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care,1 and fortunately this is now happening. Complementing hospitalists are nurses and pharmacists2 who recognize the importance of teamwork in the care of hospitalized patients. I encourage all members of the hospital care team to send us the results of their research, teaching, and quality improvement efforts.

As the specialty of hospital medicine continues to evolve, now with more than 20,000 hospitalists, JHM will develop with it. I am honored and grateful to collaborate with such a remarkable group of colleagues as we build the premier journal for the fastest growing specialty in the history of medicine in the United States. On to year 3!

P.S. Our tenuous hold on life confronted me this past Thanksgiving holiday. A fellow hospitalist and dear friend died unexpectedly. Two years before, he posted on the wall of the office shared with his colleagues the following quote:

What we do for ourselves fades, but what we do for another may be etched into eternity.

The smile and humanity of John Allen Garner (19632007) is etched into the lives of his family, many friends and colleagues, and innumerable grateful patients.

- .Hospital medicine's evolution—the next steps.J Hosp Med.2006;1:1–2.

- ,,, et al.ASHP–SHM joint statement on hospitalist–pharmacist collaboration.Am J Health‐Syst Pharm.2008;65:260–263.

- .Hospital medicine's evolution—the next steps.J Hosp Med.2006;1:1–2.

- ,,, et al.ASHP–SHM joint statement on hospitalist–pharmacist collaboration.Am J Health‐Syst Pharm.2008;65:260–263.

Thinking Inside the Box

A 65‐year‐old man was referred for evaluation of worsening ascites and end‐stage liver disease. The patient had been well until 1 year ago, when he developed lower extremity edema and abdominal distention. After evaluation by his primary care physician, he was given a diagnosis of cryptogenic cirrhosis. He underwent several paracenteses and was placed on furosemide and spironolactone. The patient had been stable on his diuretic regimen until 2 weeks previously, when he suddenly developed worsening edema and ascites, along with dizziness, nausea, and hypotension. His physician stopped the diuretics and referred him to the hospital.

Before diagnosing a patient with cryptogenic cirrhosis, it is necessary to exclude common etiologies of cirrhosis such as alcohol, viral hepatitis, and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and numerous uncommon causes, including Wilson's disease, hemochromatosis, Budd‐Chiari, and biliary cirrhosis. It is also important to remember that patients with liver disease are not immune to extrahepatic causes of ascites, such as peritoneal carcinomatosis and tuberculous ascites. Simultaneously, reasons for chronic liver disease decompensating acutely must be considered: medication nonadherence, excess salt intake, hepatotoxicity from acetaminophen or alcohol, and other acute insults, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, an intervening infection (especially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), ascending cholangitis, or a flare of chronic viral hepatitis.

Past medical and surgical history included diabetes mellitus (diagnosed 10 years previously), obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and mild chronic kidney disease. Medications included levothyroxine, lactulose, sulfamethoxazole, pioglitazone (started 4 months prior), and ibuprofen. Furosemide and spironolactone had been discontinued 2 weeks previously. He currently resided in the Central Valley of California. He had lived in Thailand from age 7 to 17 and traveled to India more than 1 year ago. He did not smoke and had never used intravenous drugs or received a blood transfusion. He rarely drank alcohol. He worked as a chemist. There was no family history of liver disease.

There is no obvious explanation for the underlying liver disease or the acute decompensation. Sulfamethoxazole is a rare cause of allergic or granulomatous hepatitis. Pioglitazone is a thiazolinedione which in earlier formulations was linked to hepatitis but can be excluded as a cause of this patient's cirrhosis because it was started after liver disease was detected. As a chemist, he might have been exposed to carbon tetrachloride, a known hepatotoxin. Obstructive sleep apnea causes pulmonary hypertension, but severe ascites and acute hepatic decompensation would be unusual. Ibuprofen might precipitate worsening renal function and fluid accumulation. Time in Thailand and India raises the possibility of tuberculous ascites.

The patient had no headache, vision changes, abdominal pain, emesis, melena, hematochezia, chest pain, palpitations, dysuria, polyuria, pruritus, dark urine, or rashes. He reported difficulty with concentration when lactulose was decreased. He noted worsening exercise tolerance with dyspnea after 10 steps and reported a weight gain of 12 pounds in the past 2 weeks.

On examination, temperature was 36.8C; blood pressure, 129/87 mm Hg; heart rate, 85 beats per minute; respirations, 20 per minute; and oxygen saturation, 94% on room air. He was uncomfortable but alert. There was no scleral icterus or conjunctival pallor. Jugular venous pressure was elevated. The lungs were clear, and the heart was regular, with no murmur, rub, or gallops. The abdomen was massively distended with a fluid wave; the liver and spleen could not be palpated. There was pitting edema of the sacrum and lower extremities. There was no asterixis, palmar erythema, spider angiomata, or skin discoloration.

The additional history and physical exam suggest that the primary problem may lie outside the liver, especially as signs of advanced liver disease (other than ascites) are absent. Dyspnea on exertion is consistent with the physical stress of a large volume of ascites or could be secondary to several pulmonary complications associated with liver disease, including portopulmonary hypertension, hepatopulmonary syndrome, or hepatic hydrothorax. Alternatively, the dyspnea raises the possibility that the ascites is not related to a primary liver disorder but rather to anemia or to a cardiac disorder, such as chronic left ventricular failure, isolated right‐sided heart failure, or constrictive pericarditis. These diagnoses are suggested by the elevated jugular venous pressure, which is atypical in cirrhosis.

Although portal hypertension accounts for most cases of ascites, peritoneal fluid should be examined to exclude peritoneal carcinomatosis and tuberculous ascites. I am interested in the results of an echocardiogram.

Initial laboratory studies demonstrated a sodium concentration of 136 mEq/dL; potassium, 4.7 mEq/dL; chloride, 99 mEq/dL; bicarbonate, 24 mEq/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 54 mg/dL; creatinine, 3.3 mg/dL (increased from baseline of 1.6 mg/dL 4 months previously); white cell count, 7000/mm3; hemoglobin, 10.5 g/dL; MCV, 89 fL; platelet count, 205,000/mm3; bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 15 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 8 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 102 U/L; albumin, 4.2 g/dL; total protein, 8.2 g/dL; international normalized ratio, 1.2; and partial thromboplastin time, 31.8 seconds. A urine dipstick demonstrated 1+ protein. The chest radiograph was normal. Electrocardiogram had borderline low voltage with nonspecific T‐wave abnormalities. Additional studies showed a serum iron concentration of 49 mg/dL, transferrin saturation of 16%, total iron binding capacity of 310 mg/dL, and ferritin of 247 mg/mL. Hemoglobin A1c was 7.0%. Acute and chronic antibodies to hepatitis A, B, and C viruses were negative. The following study results were normal or negative: antinuclear antibody, alpha‐1‐antitrypsin, ceruloplasmin, alpha‐fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and 24‐hour urinary copper. The thyroid function studies were normal. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was nonreactive.