User login

Embedding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in hospital medicine

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

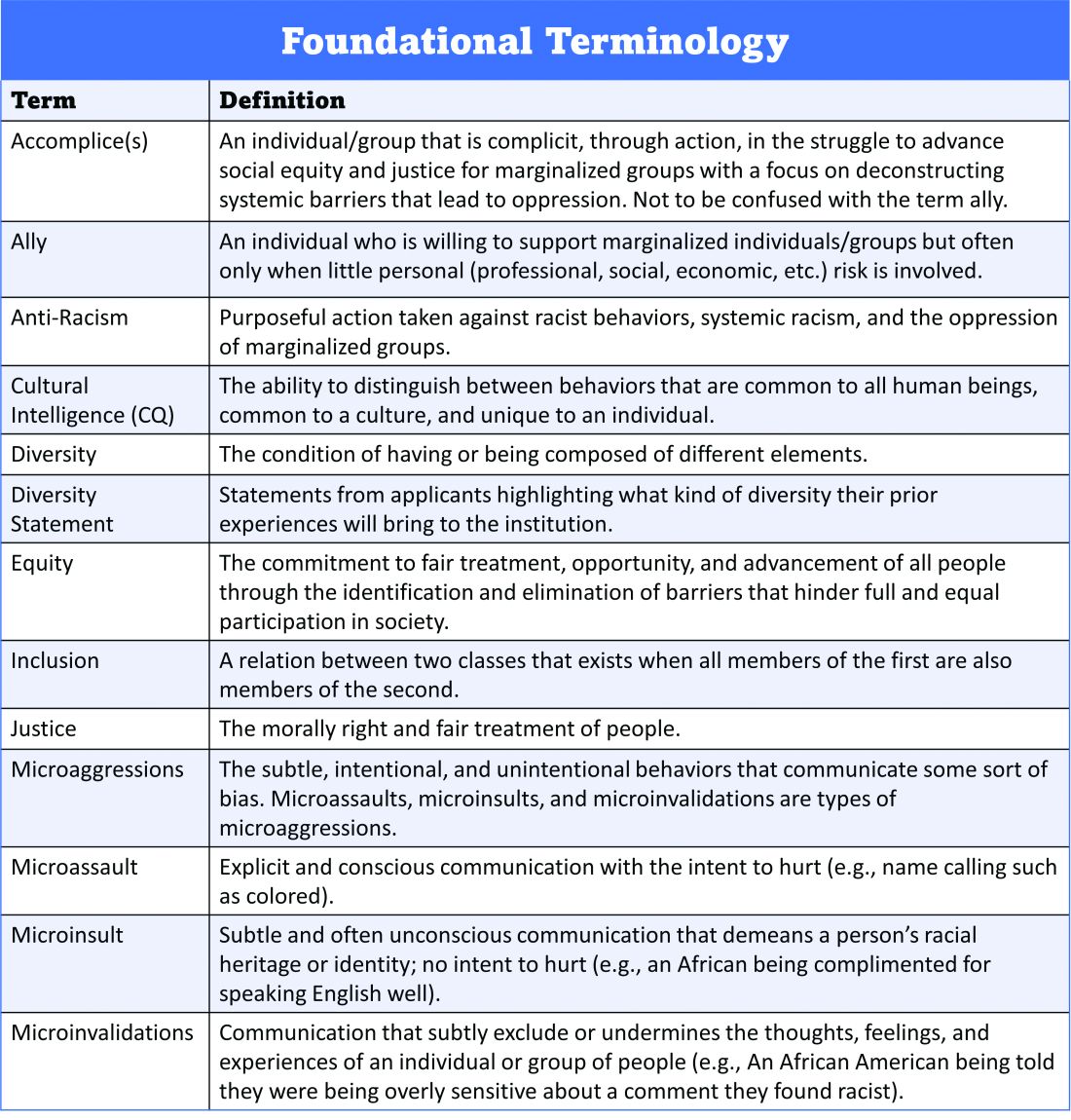

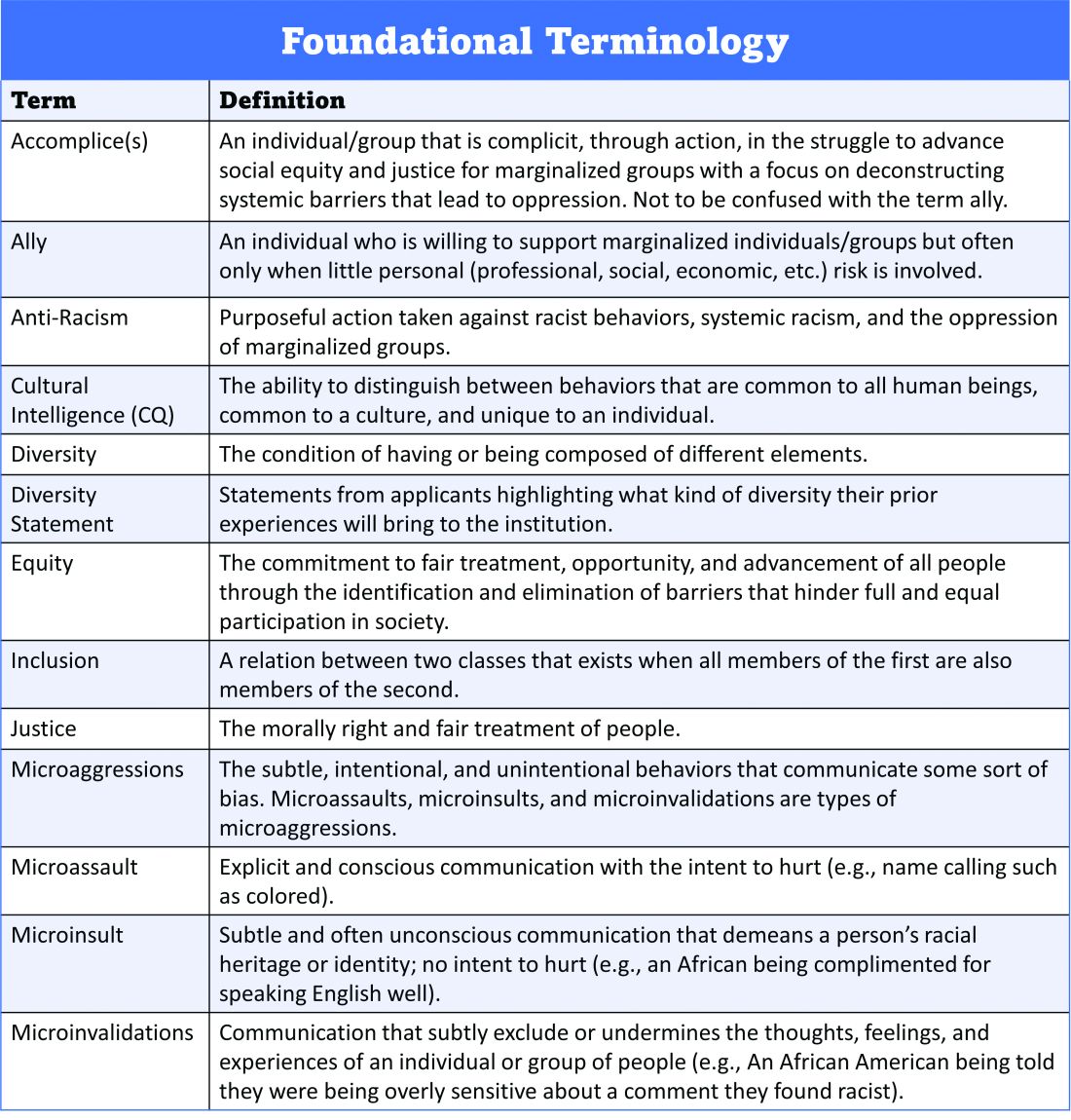

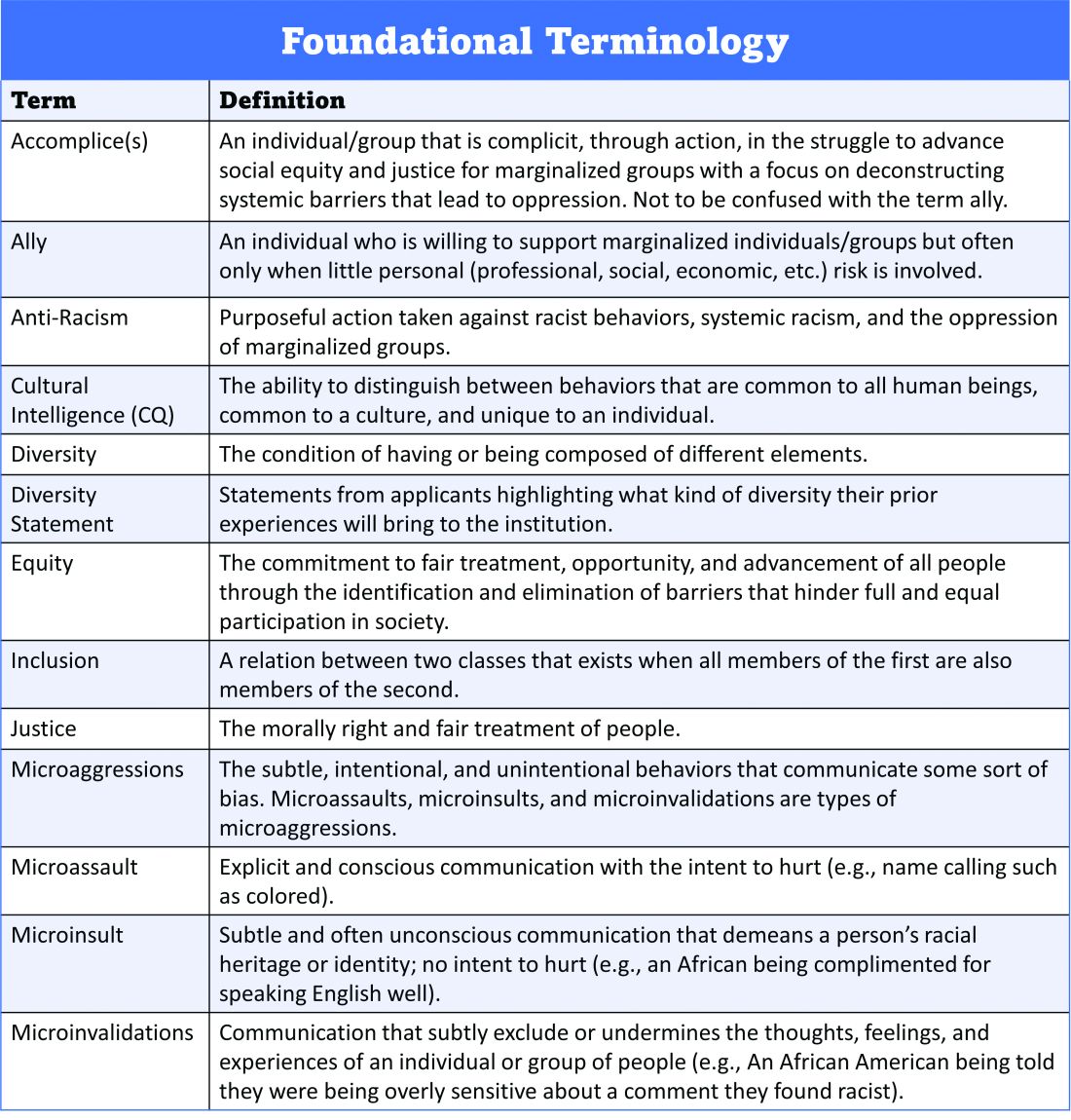

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

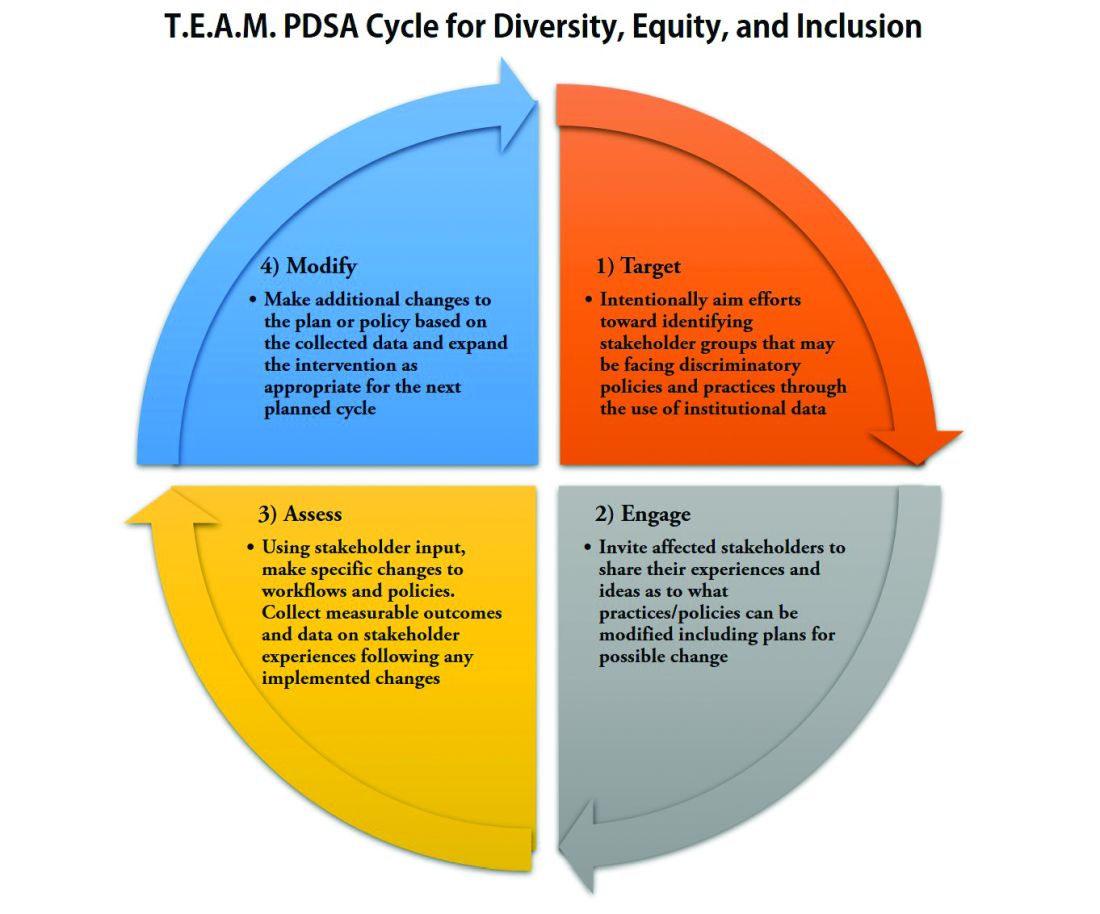

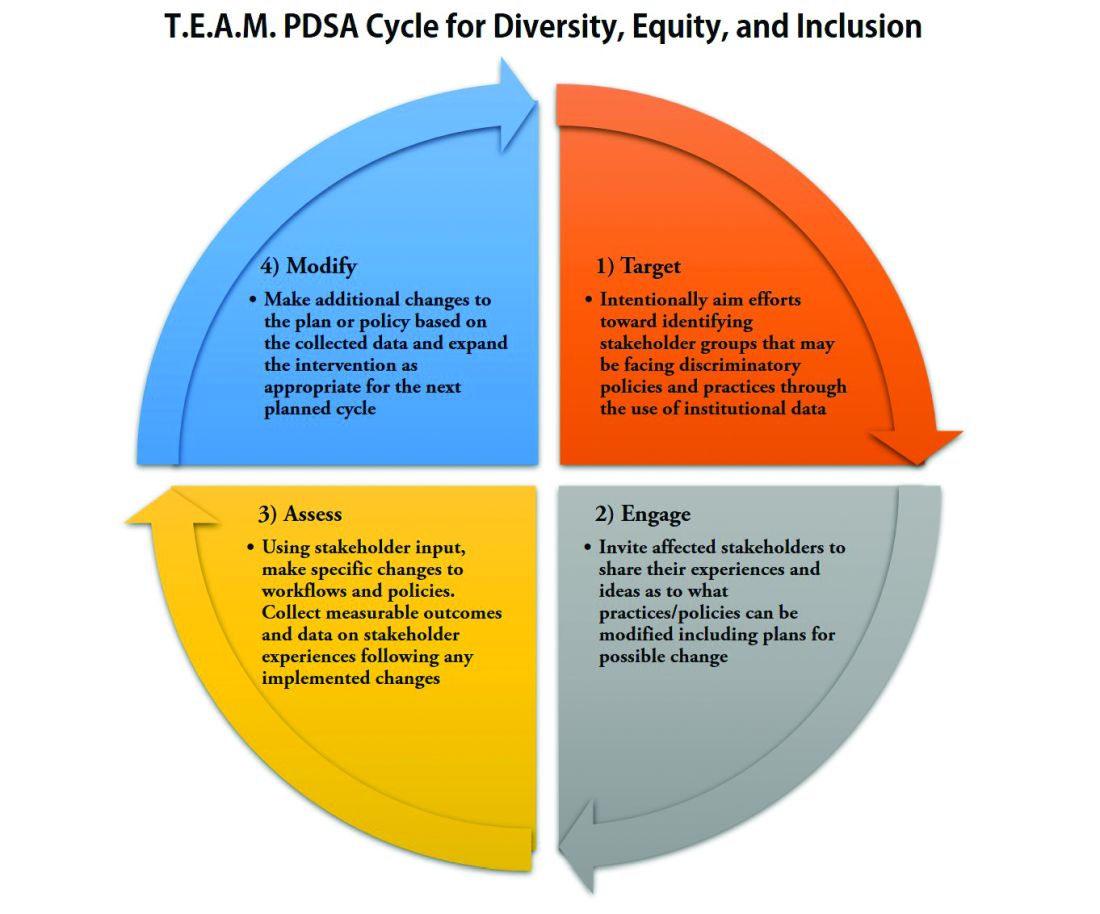

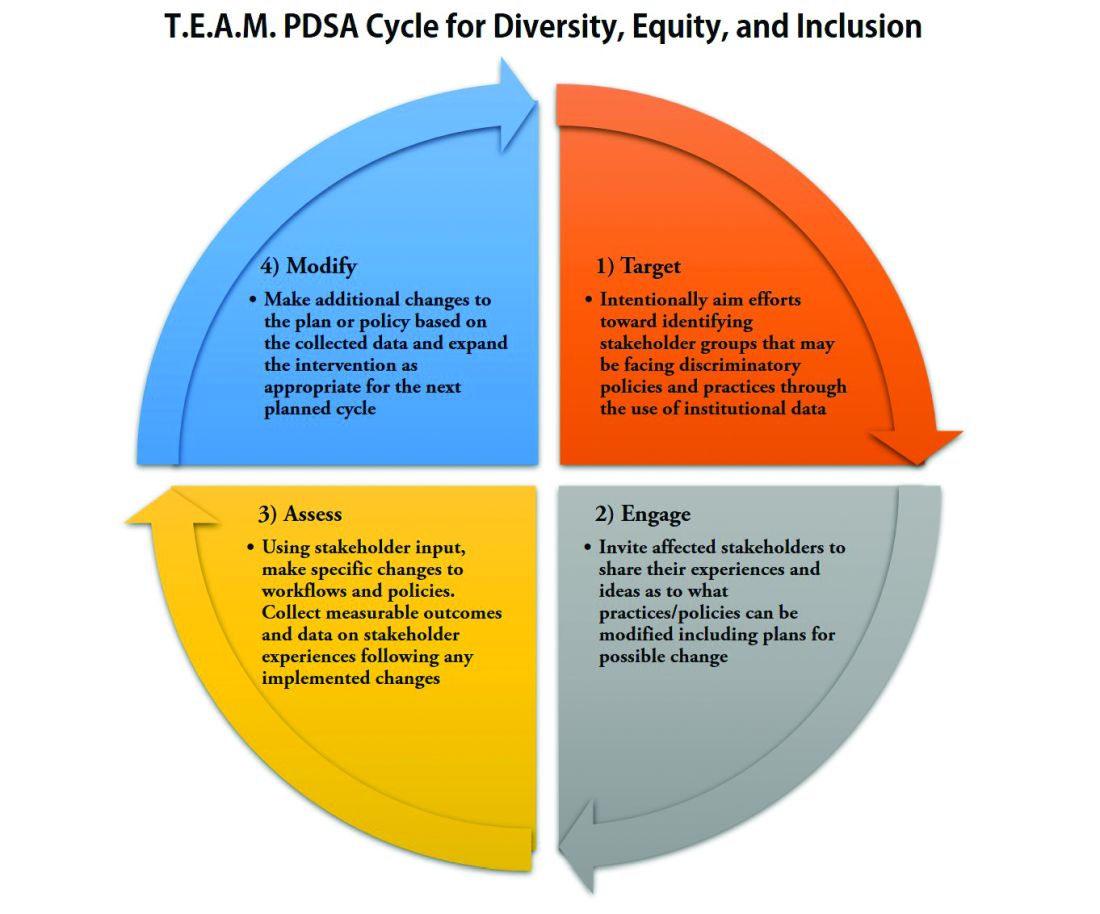

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

A road map for success

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

An Advanced Practice Provider Clinical Fellowship as a Pipeline to Staffing a Hospitalist Program

There is an increasing utilization of advanced practice providers (APPs) in the delivery of healthcare in the United States.1,2 As of 2016, there were 157, 025 nurse practitioners (NPs) and 102,084 physician assistants (PAs) with a projected growth rate of 6.8% and 4.3%, respectively, which exceeds the physician growth rate of 1.1%.2 This increased growth rate has been attributed to the expectation that APPs can enhance the quality of physician care, relieve physician shortages, and reduce service costs, as APPs are less expensive to hire than physicians.3,4 Hospital medicine is the fastest growing medical field in the United States, and approximately 83% of hospitalist groups around the country utilize APPs; however, the demand for hospitalists continues to exceed the supply, and this has led to increased utilization of APPs in hospital medicine.5-10

APPs receive very limited inpatient training and there is wide variation in their clinical abilities after graduation.11 This is an issue that has become exacerbated in recent years by a change in the training process for PAs. Before 2005, PA programs were typically two to three years long and required the same prerequisite courses as medical schools.11 PA students completed more than 2,000 hours of clinical rotations and then had to pass the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam before they could practice.12 Traditionally, PA programs typically attracted students with prior healthcare experience.11 In 2005, PA programs began transitioning from bachelor’s degrees to requiring a master’s level degree for completion of the programs. This has shifted the demographics of the students matriculating to younger students with little-to-no prior healthcare experience; moreover, these fresh graduates lack exposure to hospital medicine.11

NPs usually gain clinical experience working as registered nurses (RNs) for two or more years prior to entry into the NP program. NP programs for baccalaureate-prepared RNs vary in length from two to three years.2 There is an acute care focus for NPs in training; however, there is no standardized training or licensure to ensure that hospital medicine competencies are met.13-15 Some studies have shown that a lack of structured support has been found to affect NP role transition negatively during the first year of practice,16 and graduating NPs have indicated that they needed more out of their clinical education in terms of content, clinical experience, and competency testing.17

Hiring new APP graduates as hospitalists requires a longer and more rigorous onboarding process. On‐the‐job training in hospital medicine for new APP graduates can take as long as six to 12 months in order for them to acquire the basic skill set necessary to adequately manage hospitalized patients.15 This extended onboarding is costly because the APPs are receiving a full hospitalist salary, yet they are not functioning at full capacity. Ideally, there should be an intermediary training step between graduation and employment as hospitalist APPs. Studies have shown that APPs are interested in formal postgraduate hospital medicine training, even if it means having a lower stipend during the first year after graduating from their NP or PA program.9,15,18

The growing need for hospitalists, driven by residency work-hour reform, increased age and complexity of patients, and the need to improve the quality of inpatient care while simultaneously reducing waste, has contributed to the increasing utilization of and need for highly qualified APPs in hospital medicine.11,19,20 We established a fellowship to train APPs. The goal of this study was to determine if an APP fellowship is a cost-effective pipeline for filling vacancies within a hospitalist program.

METHODS

Design and Setting

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC) is a 440 bed hospital in Baltimore Maryland. The hospitalist group was started in 1996 with one physician seeing approximately 500 discharges a year. Over the last 20 years, the group has grown and is now its own division with 57 providers, including 42 physicians, 11 APPs, and four APP fellows. The hospitalist division manages ~7,000 discharges a year, which corresponds to approximately 60% of admissions to general medicine. Hospitalist APPs help staff general medicine by working alongside doctors and admitting patients during the day and night. The APPs also staff the pulmonary step down unit with a pulmonary attending and the chemical dependency unit with an internal medicine addiction specialist.

The growth of the division of hospital medicine at JHBMC is a result of increasing volumes and reduced residency duty hours. The increasing full time equivalents (FTEs) resulted in a need for APPs; however, vacancies went unfilled for an average of 35 weeks due to the time it took to post open positions, interview applicants, and hire applicants through the credentialing process. Further, it took as long as 22 to 34 weeks for a new hire to work independently. The APP vacancies and onboarding resulted in increased costs to the division incurred by physician moonlighting to cover open shifts. The hourly physician moonlighting rate at JHBMC is $150. All costs were calculated on the basis of a 40-hour work week. We performed a pre- and postanalysis of outcomes of interest between January 2009 and June 2018. This study was exempt from institutional review board review.

Intervention

In 2014, a one year APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine was started. The fellows evaluate and manage patients working one-on-one with an experienced hospitalist faculty member. The program consists of 80% clinical experience in the inpatient setting and 20% didactic instruction (Table 1). Up to four fellows are accepted each year and are eligible for hire after training if vacancies exist. The program is cost neutral and was financed by downsizing, through attrition, two physician FTEs. Four APP fellows’ salaries are the equivalent of two entry-level hospitalist physicians’ salaries at JHBMC. The annual salary for an APP fellow is $69,000.

Downsizing by two physician FTEs meant that one less doctor was scheduled every day. The patient load previously seen by that one doctor (10 patients) was absorbed by the MD–APP fellow dyads. Paired with a fellow, each physician sees a higher cap of 13 patients, and it takes six weeks for the fellows to ramp-up to this patient load. When the fellow first starts, the team sees 10 patients. Every two weeks, the pair’s census increases by one patient to the cap of 13. Collectively, the four APP fellow–MD dyads make it possible for four physicians to see an additional 12 patients. The two extra patients absorbed by the service per day results in a net increase in capacity of up to 730 patient encounters a year.

Outcomes and Analysis

Our main outcomes of interest were duration of onboarding and cost incurred by the division to (1) staff the service during a vacancy and (2) onboard new hires. Secondary outcomes included duration of vacancy and total time spent with the group. We collected basic demographic data on participants, including, age, gender, and race. Demographics and outcomes of interest were compared pre- (2009-2013) and post- (2014-2018) initiation of the APP clinical fellowship using the chi-square test, the t-test for normally distributed data, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum for nonnormally distributed data, as appropriate. The normality of the data distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Two-tailed P values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant. Results were analyzed using Stata/MP version 13.0 (StataCorp Inc, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

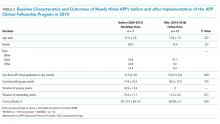

Twelve fellows have been recruited, and of these, 10 have graduated. Two chose to leave the program prior to completion. Of the 10 fellows that have graduated, six have been hired into our group, one was hired within our facility, and three were hired as hospitalists at other institutions. The median time from APP school graduation to hire was also not different between the two groups (10.5 vs 3.9 months, P = .069). In addition, the total time that the new APP hires spent with the group was nonstatistically significantly different between the two periods (17.9 vs 18.3 months, P = .735). Both the mean duration of onboarding and the cost to the division were significantly reduced after implementation of the program (25.4 vs 11.0 weeks, P = .017 and $361,714 vs $66,000, P = .004; Table 2).

The yearly cost of an APP vacancy and onboarding is incurred by doctor moonlighting costs (at the rate of $150 per hour) to cover open shifts. The mean duration of vacancies and onboarding each year was 34.9 and 25.4 weeks, respectively, before the fellowship. The yearly cost of onboarding, after the establishment of the fellowship, is a maximum of $66,000, derived from physician moonlighting to cover the six-week ramp-up at the very beginning of the fellowship and the five weeks of orientation to the pulmonary and chemical dependency units after the fellowship (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Our APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine at JHBMC has produced several benefits. First, the fellowship has become a pipeline for filling APP vacancies within our division. We have been able to hire for four consecutive years from the fellowship. Second, the ready availability of high-functioning and efficient APP hospitalists has cut down on the onboarding time for our new APP hires. Many new APP graduates lack confidence in caring for complex hospitalized patients. Following our 12-month clinical fellowship, our matriculated fellows are able to practice at the top of their license immediately and confidently. Third, the reduced vacancy and shortened onboarding periods have reduced costs to the division. Fourth, the fellowship has created additional teaching avenues for the faculty. The medicine units at JHBMC are comprised of hospitalist and internal medicine residency services. The hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time in direct patient care; however, they rotate on the residency service for two weeks out of the year. The majority of physicians welcome the chance to teach more, and partnering with an APP fellow provides that opportunity.

As we have developed and grown this program, the one great challenge has been what to do with graduating fellows when we cannot hire them. Fortunately, the market for highly qualified, well trained APPs is strong, and every one of the fellows that we could not hire within our group has been able to find a position either within our facility or outside our institution. To facilitate this process, program directors and recruiters are invited to meet with the fellows toward the end of their fellowship to share employment opportunities with them.

Our study has limitations. First, had the $276,000 from the attrition of two physicians been used to hire nonfellow APPs under the old model, then the costs of the two models would have been similar, but this was simply not possible because the positions could not be filled. Second, this is a single-site experience, and our findings may not be generalizable, particularly those pertaining to remuneration. Third, our study was underpowered to detect small but important differences in characteristics of APPs, especially time from graduation to hire, before and after the implementation of our fellowship. Further research comparing various programs both in structure and outcomes—such as fellows’ readiness for practice, costs, duration of vacancies, and provider satisfaction—are an important next step.

We have developed a pool of applicants within our division to fill vacancies left by turnover from senior NPs and PAs. This program has reduced costs and improved the joy of practice for both doctors and APPs. As the need for highly qualified NPs and PAs in hospital medicine continues to grow, we may see more APP fellowships in hospital medicine in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the advanced practice providers who have helped us grow and refine our fellowship.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose

1. Martsoff G, Nguyen P, Freund D, Poghosyan L. What we know about postgraduate nurse practitioner residency and fellowship programs. J Nurse Pract. 2017;13(7):482-487. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2017.05.013.

2. Auerbach D, Staiger D, Buerhaus P. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians-implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2358-2360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1801869. PubMed

3. Laurant M, Harmsen M, Wollersheim H, Grol R, Faber M, Sibbald B. The

impact of nonphysician clinicians: do they improve the quality and cost-effectiveness

of health care services? Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(6 Suppl):36S-89S. doi: 10.1177/1077558709346277. PubMed

4. Auerbach DI. Will the NP workforce grow in the future? New forecasts and

implications for healthcare delivery. Med Care. 2012;50(7):606-610. doi:

10.1097/MLR.0b013e318249d6e7. PubMed

5. Kisuule F, Howell E. Hospital medicine beyond the United States. Int J Gen

Med. 2018;11:65-71. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S151275. PubMed

6. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50, 000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist.

N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607958. PubMed

7. Conrad, K and Valovska T. The current state of hospital medicine: trends in

compensation, practice patterns, advanced practice providers, malpractice,

and career satisfaction. In: Conrad K, ed. Clinical Approaches to Hospital

Medicine. Cham, Springer; 2017:259-270.

8. Bryant SE. Filling the gaps: preparing nurse practitioners for hospitalist

practice. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2018;30(1):4-9. doi: 10.1097/

JXX.0000000000000008. PubMed

9. Sharma P, Brooks M, Roomiany P, Verma L, Criscione-Schreiber, L. Physician

assistant student training for the inpatient setting: a needs assessment. J Physician

Assist Educ. 2017;28(4):189-195. doi: 10.1097/JPA.0000000000000174. PubMed

10. Society of Hospital Medicine. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Available

at: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/about/press-releases/shm-releases-

2016-state-of-hospital-medicine-report/. Accessed July 17, 2018.

11. Will KK, Budavari AI, Wilkens JA, Mishari K, Hartsell ZC. A Hospitalist postgraduate

training program for physician assistants. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(2):94-

8. doi: 10.1002/jhm.619. PubMed

12. Naqvi, S. Is it time for Physician Assistant (PA)/Nurse Practitioner (NP) Hospital

Medicine Residency Training. Available at: http://medicine2.missouri.e.,-

du/jahm/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Is-it-time-for-PANP-Hospital-Medicine-

Residency-Training-Final.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2018.

13. Scheurer D, Cardin T. The Role of NPs and PAs in Hospital Medicine Programs.

From July, 2017 The Hospitalist. Available at: https://www.the-hospitalist.

org/hospitalist/article/142565/leadership-training/role-nps-and-pashospital-

medicine-programs. Accessed July 17, 2018.

14. Furfari K , Rosenthal L, Tad-y D, Wolfe B, Glasheen J. Nurse practitioners as

inpatinet providers: a hospital medicine fellowship program. J Nurse Pract.

2014;10(6):425-429. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.03.022.

15. Taylor D, Broyhill B, Burris A, Wilcox M. A strategic approach for developing

an advanced practice workforce: from postgraduate transition-to-practice

fellowship programs and beyond. Nurs Adm Q. 2017;41(1):11-19. doi:

10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000198. PubMed

16. Barnes H. Exploring the factors that influence nurse practitioners role transition.

J Nurse Pract. 2015;11(2):178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.11.004. PubMed

17. Hart MA, Macnee LC. How well are nurse practitioners prepared for practice:

results of a 2004 questionnaire study. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(1):35-

42. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00191.x PubMed

18. Torok H, Lackner C, Landis R, Wright S. Learning needs of physician assistants

working in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):190-194. doi:

10.1002/jhm.1001. PubMed

19. Kisuule F, Howell E. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety,

and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2015;42(3):433-446. doi:

10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003. PubMed

20. Ford, W, Britting L. Nonphysician Providers in the hospitalist model: a prescription

for change and a warning about unintended side effects. J Hosp

Med. 2010;5(2):99-102. doi: 10.1002/jhm.556. PubMed

There is an increasing utilization of advanced practice providers (APPs) in the delivery of healthcare in the United States.1,2 As of 2016, there were 157, 025 nurse practitioners (NPs) and 102,084 physician assistants (PAs) with a projected growth rate of 6.8% and 4.3%, respectively, which exceeds the physician growth rate of 1.1%.2 This increased growth rate has been attributed to the expectation that APPs can enhance the quality of physician care, relieve physician shortages, and reduce service costs, as APPs are less expensive to hire than physicians.3,4 Hospital medicine is the fastest growing medical field in the United States, and approximately 83% of hospitalist groups around the country utilize APPs; however, the demand for hospitalists continues to exceed the supply, and this has led to increased utilization of APPs in hospital medicine.5-10

APPs receive very limited inpatient training and there is wide variation in their clinical abilities after graduation.11 This is an issue that has become exacerbated in recent years by a change in the training process for PAs. Before 2005, PA programs were typically two to three years long and required the same prerequisite courses as medical schools.11 PA students completed more than 2,000 hours of clinical rotations and then had to pass the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam before they could practice.12 Traditionally, PA programs typically attracted students with prior healthcare experience.11 In 2005, PA programs began transitioning from bachelor’s degrees to requiring a master’s level degree for completion of the programs. This has shifted the demographics of the students matriculating to younger students with little-to-no prior healthcare experience; moreover, these fresh graduates lack exposure to hospital medicine.11

NPs usually gain clinical experience working as registered nurses (RNs) for two or more years prior to entry into the NP program. NP programs for baccalaureate-prepared RNs vary in length from two to three years.2 There is an acute care focus for NPs in training; however, there is no standardized training or licensure to ensure that hospital medicine competencies are met.13-15 Some studies have shown that a lack of structured support has been found to affect NP role transition negatively during the first year of practice,16 and graduating NPs have indicated that they needed more out of their clinical education in terms of content, clinical experience, and competency testing.17

Hiring new APP graduates as hospitalists requires a longer and more rigorous onboarding process. On‐the‐job training in hospital medicine for new APP graduates can take as long as six to 12 months in order for them to acquire the basic skill set necessary to adequately manage hospitalized patients.15 This extended onboarding is costly because the APPs are receiving a full hospitalist salary, yet they are not functioning at full capacity. Ideally, there should be an intermediary training step between graduation and employment as hospitalist APPs. Studies have shown that APPs are interested in formal postgraduate hospital medicine training, even if it means having a lower stipend during the first year after graduating from their NP or PA program.9,15,18

The growing need for hospitalists, driven by residency work-hour reform, increased age and complexity of patients, and the need to improve the quality of inpatient care while simultaneously reducing waste, has contributed to the increasing utilization of and need for highly qualified APPs in hospital medicine.11,19,20 We established a fellowship to train APPs. The goal of this study was to determine if an APP fellowship is a cost-effective pipeline for filling vacancies within a hospitalist program.

METHODS

Design and Setting

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC) is a 440 bed hospital in Baltimore Maryland. The hospitalist group was started in 1996 with one physician seeing approximately 500 discharges a year. Over the last 20 years, the group has grown and is now its own division with 57 providers, including 42 physicians, 11 APPs, and four APP fellows. The hospitalist division manages ~7,000 discharges a year, which corresponds to approximately 60% of admissions to general medicine. Hospitalist APPs help staff general medicine by working alongside doctors and admitting patients during the day and night. The APPs also staff the pulmonary step down unit with a pulmonary attending and the chemical dependency unit with an internal medicine addiction specialist.

The growth of the division of hospital medicine at JHBMC is a result of increasing volumes and reduced residency duty hours. The increasing full time equivalents (FTEs) resulted in a need for APPs; however, vacancies went unfilled for an average of 35 weeks due to the time it took to post open positions, interview applicants, and hire applicants through the credentialing process. Further, it took as long as 22 to 34 weeks for a new hire to work independently. The APP vacancies and onboarding resulted in increased costs to the division incurred by physician moonlighting to cover open shifts. The hourly physician moonlighting rate at JHBMC is $150. All costs were calculated on the basis of a 40-hour work week. We performed a pre- and postanalysis of outcomes of interest between January 2009 and June 2018. This study was exempt from institutional review board review.

Intervention

In 2014, a one year APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine was started. The fellows evaluate and manage patients working one-on-one with an experienced hospitalist faculty member. The program consists of 80% clinical experience in the inpatient setting and 20% didactic instruction (Table 1). Up to four fellows are accepted each year and are eligible for hire after training if vacancies exist. The program is cost neutral and was financed by downsizing, through attrition, two physician FTEs. Four APP fellows’ salaries are the equivalent of two entry-level hospitalist physicians’ salaries at JHBMC. The annual salary for an APP fellow is $69,000.

Downsizing by two physician FTEs meant that one less doctor was scheduled every day. The patient load previously seen by that one doctor (10 patients) was absorbed by the MD–APP fellow dyads. Paired with a fellow, each physician sees a higher cap of 13 patients, and it takes six weeks for the fellows to ramp-up to this patient load. When the fellow first starts, the team sees 10 patients. Every two weeks, the pair’s census increases by one patient to the cap of 13. Collectively, the four APP fellow–MD dyads make it possible for four physicians to see an additional 12 patients. The two extra patients absorbed by the service per day results in a net increase in capacity of up to 730 patient encounters a year.

Outcomes and Analysis

Our main outcomes of interest were duration of onboarding and cost incurred by the division to (1) staff the service during a vacancy and (2) onboard new hires. Secondary outcomes included duration of vacancy and total time spent with the group. We collected basic demographic data on participants, including, age, gender, and race. Demographics and outcomes of interest were compared pre- (2009-2013) and post- (2014-2018) initiation of the APP clinical fellowship using the chi-square test, the t-test for normally distributed data, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum for nonnormally distributed data, as appropriate. The normality of the data distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Two-tailed P values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant. Results were analyzed using Stata/MP version 13.0 (StataCorp Inc, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Twelve fellows have been recruited, and of these, 10 have graduated. Two chose to leave the program prior to completion. Of the 10 fellows that have graduated, six have been hired into our group, one was hired within our facility, and three were hired as hospitalists at other institutions. The median time from APP school graduation to hire was also not different between the two groups (10.5 vs 3.9 months, P = .069). In addition, the total time that the new APP hires spent with the group was nonstatistically significantly different between the two periods (17.9 vs 18.3 months, P = .735). Both the mean duration of onboarding and the cost to the division were significantly reduced after implementation of the program (25.4 vs 11.0 weeks, P = .017 and $361,714 vs $66,000, P = .004; Table 2).

The yearly cost of an APP vacancy and onboarding is incurred by doctor moonlighting costs (at the rate of $150 per hour) to cover open shifts. The mean duration of vacancies and onboarding each year was 34.9 and 25.4 weeks, respectively, before the fellowship. The yearly cost of onboarding, after the establishment of the fellowship, is a maximum of $66,000, derived from physician moonlighting to cover the six-week ramp-up at the very beginning of the fellowship and the five weeks of orientation to the pulmonary and chemical dependency units after the fellowship (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Our APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine at JHBMC has produced several benefits. First, the fellowship has become a pipeline for filling APP vacancies within our division. We have been able to hire for four consecutive years from the fellowship. Second, the ready availability of high-functioning and efficient APP hospitalists has cut down on the onboarding time for our new APP hires. Many new APP graduates lack confidence in caring for complex hospitalized patients. Following our 12-month clinical fellowship, our matriculated fellows are able to practice at the top of their license immediately and confidently. Third, the reduced vacancy and shortened onboarding periods have reduced costs to the division. Fourth, the fellowship has created additional teaching avenues for the faculty. The medicine units at JHBMC are comprised of hospitalist and internal medicine residency services. The hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time in direct patient care; however, they rotate on the residency service for two weeks out of the year. The majority of physicians welcome the chance to teach more, and partnering with an APP fellow provides that opportunity.

As we have developed and grown this program, the one great challenge has been what to do with graduating fellows when we cannot hire them. Fortunately, the market for highly qualified, well trained APPs is strong, and every one of the fellows that we could not hire within our group has been able to find a position either within our facility or outside our institution. To facilitate this process, program directors and recruiters are invited to meet with the fellows toward the end of their fellowship to share employment opportunities with them.

Our study has limitations. First, had the $276,000 from the attrition of two physicians been used to hire nonfellow APPs under the old model, then the costs of the two models would have been similar, but this was simply not possible because the positions could not be filled. Second, this is a single-site experience, and our findings may not be generalizable, particularly those pertaining to remuneration. Third, our study was underpowered to detect small but important differences in characteristics of APPs, especially time from graduation to hire, before and after the implementation of our fellowship. Further research comparing various programs both in structure and outcomes—such as fellows’ readiness for practice, costs, duration of vacancies, and provider satisfaction—are an important next step.

We have developed a pool of applicants within our division to fill vacancies left by turnover from senior NPs and PAs. This program has reduced costs and improved the joy of practice for both doctors and APPs. As the need for highly qualified NPs and PAs in hospital medicine continues to grow, we may see more APP fellowships in hospital medicine in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the advanced practice providers who have helped us grow and refine our fellowship.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose

There is an increasing utilization of advanced practice providers (APPs) in the delivery of healthcare in the United States.1,2 As of 2016, there were 157, 025 nurse practitioners (NPs) and 102,084 physician assistants (PAs) with a projected growth rate of 6.8% and 4.3%, respectively, which exceeds the physician growth rate of 1.1%.2 This increased growth rate has been attributed to the expectation that APPs can enhance the quality of physician care, relieve physician shortages, and reduce service costs, as APPs are less expensive to hire than physicians.3,4 Hospital medicine is the fastest growing medical field in the United States, and approximately 83% of hospitalist groups around the country utilize APPs; however, the demand for hospitalists continues to exceed the supply, and this has led to increased utilization of APPs in hospital medicine.5-10

APPs receive very limited inpatient training and there is wide variation in their clinical abilities after graduation.11 This is an issue that has become exacerbated in recent years by a change in the training process for PAs. Before 2005, PA programs were typically two to three years long and required the same prerequisite courses as medical schools.11 PA students completed more than 2,000 hours of clinical rotations and then had to pass the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam before they could practice.12 Traditionally, PA programs typically attracted students with prior healthcare experience.11 In 2005, PA programs began transitioning from bachelor’s degrees to requiring a master’s level degree for completion of the programs. This has shifted the demographics of the students matriculating to younger students with little-to-no prior healthcare experience; moreover, these fresh graduates lack exposure to hospital medicine.11

NPs usually gain clinical experience working as registered nurses (RNs) for two or more years prior to entry into the NP program. NP programs for baccalaureate-prepared RNs vary in length from two to three years.2 There is an acute care focus for NPs in training; however, there is no standardized training or licensure to ensure that hospital medicine competencies are met.13-15 Some studies have shown that a lack of structured support has been found to affect NP role transition negatively during the first year of practice,16 and graduating NPs have indicated that they needed more out of their clinical education in terms of content, clinical experience, and competency testing.17

Hiring new APP graduates as hospitalists requires a longer and more rigorous onboarding process. On‐the‐job training in hospital medicine for new APP graduates can take as long as six to 12 months in order for them to acquire the basic skill set necessary to adequately manage hospitalized patients.15 This extended onboarding is costly because the APPs are receiving a full hospitalist salary, yet they are not functioning at full capacity. Ideally, there should be an intermediary training step between graduation and employment as hospitalist APPs. Studies have shown that APPs are interested in formal postgraduate hospital medicine training, even if it means having a lower stipend during the first year after graduating from their NP or PA program.9,15,18

The growing need for hospitalists, driven by residency work-hour reform, increased age and complexity of patients, and the need to improve the quality of inpatient care while simultaneously reducing waste, has contributed to the increasing utilization of and need for highly qualified APPs in hospital medicine.11,19,20 We established a fellowship to train APPs. The goal of this study was to determine if an APP fellowship is a cost-effective pipeline for filling vacancies within a hospitalist program.

METHODS

Design and Setting

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC) is a 440 bed hospital in Baltimore Maryland. The hospitalist group was started in 1996 with one physician seeing approximately 500 discharges a year. Over the last 20 years, the group has grown and is now its own division with 57 providers, including 42 physicians, 11 APPs, and four APP fellows. The hospitalist division manages ~7,000 discharges a year, which corresponds to approximately 60% of admissions to general medicine. Hospitalist APPs help staff general medicine by working alongside doctors and admitting patients during the day and night. The APPs also staff the pulmonary step down unit with a pulmonary attending and the chemical dependency unit with an internal medicine addiction specialist.

The growth of the division of hospital medicine at JHBMC is a result of increasing volumes and reduced residency duty hours. The increasing full time equivalents (FTEs) resulted in a need for APPs; however, vacancies went unfilled for an average of 35 weeks due to the time it took to post open positions, interview applicants, and hire applicants through the credentialing process. Further, it took as long as 22 to 34 weeks for a new hire to work independently. The APP vacancies and onboarding resulted in increased costs to the division incurred by physician moonlighting to cover open shifts. The hourly physician moonlighting rate at JHBMC is $150. All costs were calculated on the basis of a 40-hour work week. We performed a pre- and postanalysis of outcomes of interest between January 2009 and June 2018. This study was exempt from institutional review board review.

Intervention

In 2014, a one year APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine was started. The fellows evaluate and manage patients working one-on-one with an experienced hospitalist faculty member. The program consists of 80% clinical experience in the inpatient setting and 20% didactic instruction (Table 1). Up to four fellows are accepted each year and are eligible for hire after training if vacancies exist. The program is cost neutral and was financed by downsizing, through attrition, two physician FTEs. Four APP fellows’ salaries are the equivalent of two entry-level hospitalist physicians’ salaries at JHBMC. The annual salary for an APP fellow is $69,000.

Downsizing by two physician FTEs meant that one less doctor was scheduled every day. The patient load previously seen by that one doctor (10 patients) was absorbed by the MD–APP fellow dyads. Paired with a fellow, each physician sees a higher cap of 13 patients, and it takes six weeks for the fellows to ramp-up to this patient load. When the fellow first starts, the team sees 10 patients. Every two weeks, the pair’s census increases by one patient to the cap of 13. Collectively, the four APP fellow–MD dyads make it possible for four physicians to see an additional 12 patients. The two extra patients absorbed by the service per day results in a net increase in capacity of up to 730 patient encounters a year.

Outcomes and Analysis

Our main outcomes of interest were duration of onboarding and cost incurred by the division to (1) staff the service during a vacancy and (2) onboard new hires. Secondary outcomes included duration of vacancy and total time spent with the group. We collected basic demographic data on participants, including, age, gender, and race. Demographics and outcomes of interest were compared pre- (2009-2013) and post- (2014-2018) initiation of the APP clinical fellowship using the chi-square test, the t-test for normally distributed data, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum for nonnormally distributed data, as appropriate. The normality of the data distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Two-tailed P values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant. Results were analyzed using Stata/MP version 13.0 (StataCorp Inc, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Twelve fellows have been recruited, and of these, 10 have graduated. Two chose to leave the program prior to completion. Of the 10 fellows that have graduated, six have been hired into our group, one was hired within our facility, and three were hired as hospitalists at other institutions. The median time from APP school graduation to hire was also not different between the two groups (10.5 vs 3.9 months, P = .069). In addition, the total time that the new APP hires spent with the group was nonstatistically significantly different between the two periods (17.9 vs 18.3 months, P = .735). Both the mean duration of onboarding and the cost to the division were significantly reduced after implementation of the program (25.4 vs 11.0 weeks, P = .017 and $361,714 vs $66,000, P = .004; Table 2).

The yearly cost of an APP vacancy and onboarding is incurred by doctor moonlighting costs (at the rate of $150 per hour) to cover open shifts. The mean duration of vacancies and onboarding each year was 34.9 and 25.4 weeks, respectively, before the fellowship. The yearly cost of onboarding, after the establishment of the fellowship, is a maximum of $66,000, derived from physician moonlighting to cover the six-week ramp-up at the very beginning of the fellowship and the five weeks of orientation to the pulmonary and chemical dependency units after the fellowship (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Our APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine at JHBMC has produced several benefits. First, the fellowship has become a pipeline for filling APP vacancies within our division. We have been able to hire for four consecutive years from the fellowship. Second, the ready availability of high-functioning and efficient APP hospitalists has cut down on the onboarding time for our new APP hires. Many new APP graduates lack confidence in caring for complex hospitalized patients. Following our 12-month clinical fellowship, our matriculated fellows are able to practice at the top of their license immediately and confidently. Third, the reduced vacancy and shortened onboarding periods have reduced costs to the division. Fourth, the fellowship has created additional teaching avenues for the faculty. The medicine units at JHBMC are comprised of hospitalist and internal medicine residency services. The hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time in direct patient care; however, they rotate on the residency service for two weeks out of the year. The majority of physicians welcome the chance to teach more, and partnering with an APP fellow provides that opportunity.

As we have developed and grown this program, the one great challenge has been what to do with graduating fellows when we cannot hire them. Fortunately, the market for highly qualified, well trained APPs is strong, and every one of the fellows that we could not hire within our group has been able to find a position either within our facility or outside our institution. To facilitate this process, program directors and recruiters are invited to meet with the fellows toward the end of their fellowship to share employment opportunities with them.

Our study has limitations. First, had the $276,000 from the attrition of two physicians been used to hire nonfellow APPs under the old model, then the costs of the two models would have been similar, but this was simply not possible because the positions could not be filled. Second, this is a single-site experience, and our findings may not be generalizable, particularly those pertaining to remuneration. Third, our study was underpowered to detect small but important differences in characteristics of APPs, especially time from graduation to hire, before and after the implementation of our fellowship. Further research comparing various programs both in structure and outcomes—such as fellows’ readiness for practice, costs, duration of vacancies, and provider satisfaction—are an important next step.

We have developed a pool of applicants within our division to fill vacancies left by turnover from senior NPs and PAs. This program has reduced costs and improved the joy of practice for both doctors and APPs. As the need for highly qualified NPs and PAs in hospital medicine continues to grow, we may see more APP fellowships in hospital medicine in the United States.

Acknowledgments