User login

VA Report Says Endoscope Problems Continue

Grand Rounds: Man, 60, With Abdominal Pain

A 60-year-old white man with a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and anxiety presented with complaints of abdominal pain, localized to an area left of the umbilicus. He described the pain as constant and rated it 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. He said the pain had been present for longer than three weeks.

The man said he had been seen by another health care provider shortly after the pain began, but he did not think the provider took his complaint seriously. At that visit, antacids were prescribed, blood work was ordered, and the man was told to return if there was no improvement. He felt that because he was being treated for anxiety, the provider believed he was just imagining the pain.

At the current visit, the review of systems revealed additional complaints of shakiness and nausea without vomiting, with other findings unremarkable. The persistent pain did not seem related to eating, and the patient had no history of any surgeries that might help explain his current complaints. He had smoked a pack of cigarettes daily for 40 years and had a history of heavy alcohol use, although he denied having consumed any alcohol during the previous five years.

His prescribed medications included gemfibrozil 600 mg per day, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg each morning, and diazepam 5 mg twice daily, with an OTC antacid.

The patient’s recent laboratory results were normal; they included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver enzyme levels, and a serum amylase level. The patient weighed 280 lb and his height was 5’10”; his BMI was 40. His temperature was 97.7°F, with a regular heart rate of 88 beats/min; blood pressure, 140/90 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min.

The patient did not appear to be in acute distress. A bruit was heard in the indicated area of pain. No mass was palpated, and the width of his aorta could not be determined because of his obesity. His physical exam was otherwise normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a 5.5-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and the man was referred for immediate surgery. The aneurysm was repaired in an open abdominal procedure with a polyester prosthetic graft. The surgery was successful.

Discussion

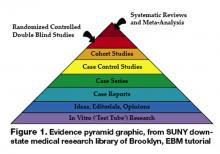

AAA is a permanent bulging area of the aorta that exceeds 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1). It is a potentially life-threatening condition due to the possibility of rupture. Often an aneurysm is asymptomatic until it ruptures, making this a difficult illness to diagnose.1

Each year, an estimated 10,000 deaths result from a ruptured AAA, making this condition the 14th leading cause of death in the United States.2,3 Incidence of AAA appears to have increased over the past two decades. Causes for this may include the aging of the US population, an increase in the number of smokers, and a trend toward diets that are higher in fat.

Prognosis among patients with AAA can be improved with increased awareness of the disease among health care providers, earlier detection of AAAs at risk for rupture, and timely, effective interventions.

Symptomatology

In about one-third of patients with a ruptured AAA, a clinical triad of symptoms is present: abdominal and/or back pain, a pulsatile abdominal mass, and hypotension.4,5 In these cases, according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA),4 immediate surgical evaluation is indicated.

Prior to the rupture of an AAA, the patient may feel a pulsing sensation in the abdomen or may experience no symptoms at all. Some patients report vague complaints, such as back, flank, groin, or abdominal pain. Syncope may be the chief complaint as the aneurysm expands, so it is important for primary care providers to be alert to progressive symptoms, including this signal that an aneurysm may exist and may be expanding.6

Pain may also be abrupt and severe in the lower abdomen and back, including tenderness in the area over the aneurysm. Shock can develop rapidly and symptoms such as cyanosis, mottling, altered mental status, tachycardia, and hypotension may be present.1,4

Since symptoms may be vague, the differential diagnosis can be broad (see Table 14,7,8), necessitating a detailed patient history and a careful physical examination. In an elderly patient, low back pain should be evaluated for AAA.9 In addition, acute abdominal pain in a patient older than 50 should be presumed to be a ruptured AAA.8

Risk Factors

A clinician should be familiar with the risk factors for AAA so that diagnosis can be made before a rupture occurs. Male gender and age greater than 65 are important risk factors for AAA, but one of the most important environmental risks is cigarette smoking.9,10 Current smokers are more than seven times more likely than nonsmokers to have an aneurysm.10 Atherosclerosis, which weakens the wall of the aorta, is also believed to contribute to the risk for AAA.11

Other contributing factors include hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, and family history. Chronic infection, inflammatory illnesses, and connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome) can also increase the risk for aneurysm. Less frequent causes of AAA are trauma and infectious diseases, such as syphilis.1,12

In 85% of patients with femoral aneurysms, AAA has been found to coexist, as it has in 62% of patients with popliteal aneurysms. Patients previously diagnosed with these conditions should be screened for AAA.4,13,14

Diagnosis

An abdominal bruit or a pulsating mass may be found on palpation, but the sensitivity for detection of AAA is related to its size. An aneurysm greater than 5.0 cm has an 82% chance of detection by palpation.15 To assess for the presence of an abdominal aneurysm, the examiner should press the midline between the xiphoid and umbilicus bimanually, firmly but gently.12 There is no evidence to suggest that palpating the abdomen can cause an aneurysm to rupture.

The most useful tests for diagnosis of AAA are US, CT, and MRI.6 US is the simplest and least costly of these diagnostic procedures; it is noninvasive and has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of nearly 100%. Bedside US can provide a rapid diagnosis in an unstable patient.16

CT is nearly 100% effective in diagnosing AAA and is usually used to help decide on appropriate treatment, as it can determine the size and shape of the aneurysm.17 However, CT should not be used for unstable patients.

MRI is useful in diagnosing AAA, but it is expensive, and inappropriate for unstable patients. Currently, conventional aortography is rarely used for preoperative assessment but may still be used for placement of endovascular devices or in patients with renal complications.1,12

Screening Recommendations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all men ages 65 to 74 who have a lifelong history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes should be screened for AAA with abdominal US.3,18 Screening is not recommended for those younger than 65 who have never smoked, but this decision must be individualized to the patient, with other risk factors considered.

The ACC/AHA4 advises that men whose parents or siblings have a history of AAA and who are older than 60 should undergo physical examination and screening US for AAA. In addition, patients with a small AAA should receive US surveillance until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter; survival has not been shown to improve if an AAA is repaired before it reaches this size.1,2,19 In consideration of increased comorbidities and decreased life expectancy, screening is not recommended for men older than 75, but this too should be determined individually.3

Screening for women is not recommended by the USPSTF.3,18 The document states that the prevalence of large AAAs in women is low and that screening may lead to an increased number of unnecessary surgeries with associated morbidity and mortality. Clinical judgment must be used in making this decision, however, as several studies have shown that women have an AAA rupture rate that is three times higher than that in men; they also have an increased in-hospital mortality rate when rupture does occur. Thus, women are less likely to experience AAA but have a worse prognosis when AAA does develop.20-22

Management

The size of an AAA is the most important predictor of rupture. According to the ACC/AHA,4 the associated risk for rupture is about 20% for aneurysms that measure 5.0 cm in diameter, 40% for those measuring at least 6.0 cm, and at least 50% for aneurysms exceeding 7.0 cm.4,23,24 Regarding surveillance of known aneurysms, it is recommended that a patient with an aneurysm smaller than 3.0 cm in diameter requires no further testing. If an AAA measures 3.0 to 4.0 cm, US should be performed yearly; if it is 4.0 to 4.9 cm, US should be performed every six months.4,25

If an identified AAA is larger than 4.5 cm, or if any segment of the aorta is more than 1.5 times the diameter of an adjacent section, referral to a vascular surgeon for further evaluation is indicated. The vascular surgeon should be consulted immediately regarding a symptomatic patient with an AAA, or one with an aneurysm that measures 5.5 cm or larger, as the risk for rupture is high.4,26

Preventing rupture of an AAA is the primary aim in management. Beta-blockers may be used to reduce systolic hypertension in cardiac patients, thus slowing the rate of expansion in those with aortic aneurysms. Patients with a known AAA should undergo frequent monitoring for blood pressure and lipid levels and be advised to stop smoking. Smoking cessation interventions such as behavior modification, nicotine replacement, or bupropion should be offered.27,28

There is evidence that statin use may reduce the size of aneurysms, even in patients without hypercholesterolemia, possibly due to statins’ anti-inflammatory properties.22,29 ACE inhibitors may also be beneficial in reducing AAA growth and in lowering blood pressure. Antiplatelet medications are important in general cardiovascular risk reduction in the patient with AAA. Aspirin is the drug of choice.27,29

Surgical Repair

AAAs are usually repaired by one of two types of surgery: endovascular repair (EVR) or open surgery. Open surgical repair, the more traditional method, involves an incision into the abdomen from the breastbone to below the navel. The weakened area is replaced with a graft made of synthetic material. Open repair of an intact AAA, performed under general anesthesia, takes from three to six hours, and the patient must be hospitalized for five to eight days.30

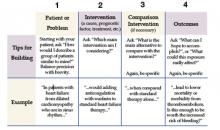

In EVR, the patient is given epidural anesthesia and an incision is made in the right groin, allowing a synthetic stent graft to be threaded by way of a catheter through the femoral artery to repair the lesion (see Figure 2). EVR generally takes two to five hours, followed by a two- to five-day hospital stay. EVR is usually recommended for patients who are at high risk for complications from open operations because of severe cardiopulmonary disease or other risk factors, such as advanced age, morbid obesity, or a history of multiple abdominal operations.1,2,4,19

Prognosis

Patients with a ruptured AAA have a survival rate of less than 50%, with most deaths occurring before surgical repair has been attempted.3,31 In patients with kidney failure resulting from AAA (whether ruptured or unruptured, an AAA can disrupt renal blood flow), the chance for survival is poor. By contrast, the risk for death during surgical graft repair of an AAA is only about 2% to 8%.1,12

In a systematic review, EVR was associated with a lower 30-day mortality rate compared with open surgical repair (1.6% vs 4.7%, respectively), but this reduction did not persist over two years’ follow-up; neither did EVR improve overall survival or quality of life, compared with open surgery.1 Additionally, EVR requires periodic imaging throughout the patient’s life, which is associated with more reinterventions.1,19

Patient Education

Clinicians should encourage all patients to stop smoking, follow a low-cholesterol diet, control hypertension, and exercise regularly to lower the risk for AAAs. Screening recommendations should be explained to patients at risk, as should the signs and symptoms of an aneurysm. These patients should be instructed to call their health care provider immediately if they suspect a problem.

Conclusion

The incidence of AAA is increasing, and primary care providers must be prepared to act promptly in any case of suspected AAA to ensure a safe outcome. For aneurysms measuring greater than 5.5 cm in diameter, open or endovascular surgical repair should be considered. Patients with smaller aneurysms or contraindications for surgery should receive careful medical management and education to reduce the risks of AAA expansion leading to possible rupture.

1. Wilt TJ, Lederle FA, MacDonald R, et al; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparison of Endovascular and Open Surgical Repairs for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. AHRQ publication 06-E107. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 144. www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/tp/aaareptp.htm. Accessed June 23, 2009.

2. Birkmeyer JD, Upchurch GR Jr. Evidence-based screening and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):749-750.

3. Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203-211.

4. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1239-1312.

5. Kiell CS, Ernst CB. Advances in management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Adv Surg. 1993;26:73–98.

6. O’Connor RE. Aneurysm, abdominal. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/756735-overview. Accessed June 23, 2009.

7. Lederle FA, Parenti CM, Chute EP. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: the internist as diagnostician. Am J Med. 1994;96:163-167.

8. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(7): 971-978.

9. Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1537-1544.

10. Wilmink TB, Quick CR, Day NE. The association between cigarette smoking and abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(6):1099-1105.

11. Palazzuoli P, Gallotta M, Guerrieri G, et al. Prevalence of risk factors, coronary and systemic atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm: comparison with high cardiovascular risk population. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(4):877-883.

12. Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577-1589.

13. Graham LM, Zelenock GB, Whitehouse WM Jr, et al. Clinical significance of arteriosclerotic femoral artery aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1980;115(4):502–507.

14. Whitehouse WM Jr, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, et al. Limb-threatening potential of arteriosclerotic popliteal artery aneurysms. Surgery. 1983;93(5):694–699.

15. Fink HA, Lederle FA, Roth CS, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833-836.

16. Bentz S, Jones J. Accuracy of emergency department ultrasound scanning in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):803-804.

17. Kvilekval KH, Best IM, Mason RA, et al. The value of computed tomography in the management of symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12(1):28-33.

18. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):198-202.

19. Lederle FA, Kane RL, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):735-741.

20. McPhee JT, Hill JS, Elami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001-2004. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(5):891-899.

21. Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J, et al. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2007;94(3):310-314.

22. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2865-2869.

23. Englund R, Hudson P, Hanel K, Stanton A. Expansion rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(1):21–24.

24. Conway KP, Byrne J, Townsend M, Lane IF. Prognosis of patients turned down for conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the endovascular and sonographic era: Szilagyi revisited? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(4):752–757.

25. Cook TA, Galland RB. A prospective study to define the optimum rescreening interval for small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4(4):441–444.

26. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Association of Vascular Surgery; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(1):267-269.

27. Golledge J, Powell JT. Medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;4(3):267-273.

28. Sule S, Aronow WS. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Compr Ther. 2009;35(1):3-8.

29. Powell JT. Non-operative or medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg. 2008;97(2): 121-124.

30. Huber TS, Wang JG, Derrow AE, et al. Experience in the United States with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2):304-310.

31. Adam DJ, Mohan IV, Stuart WP, et al. Community and hospital outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm within the catchment area of a regional vascular surgical service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(5):922-928.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and anxiety presented with complaints of abdominal pain, localized to an area left of the umbilicus. He described the pain as constant and rated it 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. He said the pain had been present for longer than three weeks.

The man said he had been seen by another health care provider shortly after the pain began, but he did not think the provider took his complaint seriously. At that visit, antacids were prescribed, blood work was ordered, and the man was told to return if there was no improvement. He felt that because he was being treated for anxiety, the provider believed he was just imagining the pain.

At the current visit, the review of systems revealed additional complaints of shakiness and nausea without vomiting, with other findings unremarkable. The persistent pain did not seem related to eating, and the patient had no history of any surgeries that might help explain his current complaints. He had smoked a pack of cigarettes daily for 40 years and had a history of heavy alcohol use, although he denied having consumed any alcohol during the previous five years.

His prescribed medications included gemfibrozil 600 mg per day, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg each morning, and diazepam 5 mg twice daily, with an OTC antacid.

The patient’s recent laboratory results were normal; they included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver enzyme levels, and a serum amylase level. The patient weighed 280 lb and his height was 5’10”; his BMI was 40. His temperature was 97.7°F, with a regular heart rate of 88 beats/min; blood pressure, 140/90 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min.

The patient did not appear to be in acute distress. A bruit was heard in the indicated area of pain. No mass was palpated, and the width of his aorta could not be determined because of his obesity. His physical exam was otherwise normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a 5.5-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and the man was referred for immediate surgery. The aneurysm was repaired in an open abdominal procedure with a polyester prosthetic graft. The surgery was successful.

Discussion

AAA is a permanent bulging area of the aorta that exceeds 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1). It is a potentially life-threatening condition due to the possibility of rupture. Often an aneurysm is asymptomatic until it ruptures, making this a difficult illness to diagnose.1

Each year, an estimated 10,000 deaths result from a ruptured AAA, making this condition the 14th leading cause of death in the United States.2,3 Incidence of AAA appears to have increased over the past two decades. Causes for this may include the aging of the US population, an increase in the number of smokers, and a trend toward diets that are higher in fat.

Prognosis among patients with AAA can be improved with increased awareness of the disease among health care providers, earlier detection of AAAs at risk for rupture, and timely, effective interventions.

Symptomatology

In about one-third of patients with a ruptured AAA, a clinical triad of symptoms is present: abdominal and/or back pain, a pulsatile abdominal mass, and hypotension.4,5 In these cases, according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA),4 immediate surgical evaluation is indicated.

Prior to the rupture of an AAA, the patient may feel a pulsing sensation in the abdomen or may experience no symptoms at all. Some patients report vague complaints, such as back, flank, groin, or abdominal pain. Syncope may be the chief complaint as the aneurysm expands, so it is important for primary care providers to be alert to progressive symptoms, including this signal that an aneurysm may exist and may be expanding.6

Pain may also be abrupt and severe in the lower abdomen and back, including tenderness in the area over the aneurysm. Shock can develop rapidly and symptoms such as cyanosis, mottling, altered mental status, tachycardia, and hypotension may be present.1,4

Since symptoms may be vague, the differential diagnosis can be broad (see Table 14,7,8), necessitating a detailed patient history and a careful physical examination. In an elderly patient, low back pain should be evaluated for AAA.9 In addition, acute abdominal pain in a patient older than 50 should be presumed to be a ruptured AAA.8

Risk Factors

A clinician should be familiar with the risk factors for AAA so that diagnosis can be made before a rupture occurs. Male gender and age greater than 65 are important risk factors for AAA, but one of the most important environmental risks is cigarette smoking.9,10 Current smokers are more than seven times more likely than nonsmokers to have an aneurysm.10 Atherosclerosis, which weakens the wall of the aorta, is also believed to contribute to the risk for AAA.11

Other contributing factors include hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, and family history. Chronic infection, inflammatory illnesses, and connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome) can also increase the risk for aneurysm. Less frequent causes of AAA are trauma and infectious diseases, such as syphilis.1,12

In 85% of patients with femoral aneurysms, AAA has been found to coexist, as it has in 62% of patients with popliteal aneurysms. Patients previously diagnosed with these conditions should be screened for AAA.4,13,14

Diagnosis

An abdominal bruit or a pulsating mass may be found on palpation, but the sensitivity for detection of AAA is related to its size. An aneurysm greater than 5.0 cm has an 82% chance of detection by palpation.15 To assess for the presence of an abdominal aneurysm, the examiner should press the midline between the xiphoid and umbilicus bimanually, firmly but gently.12 There is no evidence to suggest that palpating the abdomen can cause an aneurysm to rupture.

The most useful tests for diagnosis of AAA are US, CT, and MRI.6 US is the simplest and least costly of these diagnostic procedures; it is noninvasive and has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of nearly 100%. Bedside US can provide a rapid diagnosis in an unstable patient.16

CT is nearly 100% effective in diagnosing AAA and is usually used to help decide on appropriate treatment, as it can determine the size and shape of the aneurysm.17 However, CT should not be used for unstable patients.

MRI is useful in diagnosing AAA, but it is expensive, and inappropriate for unstable patients. Currently, conventional aortography is rarely used for preoperative assessment but may still be used for placement of endovascular devices or in patients with renal complications.1,12

Screening Recommendations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all men ages 65 to 74 who have a lifelong history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes should be screened for AAA with abdominal US.3,18 Screening is not recommended for those younger than 65 who have never smoked, but this decision must be individualized to the patient, with other risk factors considered.

The ACC/AHA4 advises that men whose parents or siblings have a history of AAA and who are older than 60 should undergo physical examination and screening US for AAA. In addition, patients with a small AAA should receive US surveillance until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter; survival has not been shown to improve if an AAA is repaired before it reaches this size.1,2,19 In consideration of increased comorbidities and decreased life expectancy, screening is not recommended for men older than 75, but this too should be determined individually.3

Screening for women is not recommended by the USPSTF.3,18 The document states that the prevalence of large AAAs in women is low and that screening may lead to an increased number of unnecessary surgeries with associated morbidity and mortality. Clinical judgment must be used in making this decision, however, as several studies have shown that women have an AAA rupture rate that is three times higher than that in men; they also have an increased in-hospital mortality rate when rupture does occur. Thus, women are less likely to experience AAA but have a worse prognosis when AAA does develop.20-22

Management

The size of an AAA is the most important predictor of rupture. According to the ACC/AHA,4 the associated risk for rupture is about 20% for aneurysms that measure 5.0 cm in diameter, 40% for those measuring at least 6.0 cm, and at least 50% for aneurysms exceeding 7.0 cm.4,23,24 Regarding surveillance of known aneurysms, it is recommended that a patient with an aneurysm smaller than 3.0 cm in diameter requires no further testing. If an AAA measures 3.0 to 4.0 cm, US should be performed yearly; if it is 4.0 to 4.9 cm, US should be performed every six months.4,25

If an identified AAA is larger than 4.5 cm, or if any segment of the aorta is more than 1.5 times the diameter of an adjacent section, referral to a vascular surgeon for further evaluation is indicated. The vascular surgeon should be consulted immediately regarding a symptomatic patient with an AAA, or one with an aneurysm that measures 5.5 cm or larger, as the risk for rupture is high.4,26

Preventing rupture of an AAA is the primary aim in management. Beta-blockers may be used to reduce systolic hypertension in cardiac patients, thus slowing the rate of expansion in those with aortic aneurysms. Patients with a known AAA should undergo frequent monitoring for blood pressure and lipid levels and be advised to stop smoking. Smoking cessation interventions such as behavior modification, nicotine replacement, or bupropion should be offered.27,28

There is evidence that statin use may reduce the size of aneurysms, even in patients without hypercholesterolemia, possibly due to statins’ anti-inflammatory properties.22,29 ACE inhibitors may also be beneficial in reducing AAA growth and in lowering blood pressure. Antiplatelet medications are important in general cardiovascular risk reduction in the patient with AAA. Aspirin is the drug of choice.27,29

Surgical Repair

AAAs are usually repaired by one of two types of surgery: endovascular repair (EVR) or open surgery. Open surgical repair, the more traditional method, involves an incision into the abdomen from the breastbone to below the navel. The weakened area is replaced with a graft made of synthetic material. Open repair of an intact AAA, performed under general anesthesia, takes from three to six hours, and the patient must be hospitalized for five to eight days.30

In EVR, the patient is given epidural anesthesia and an incision is made in the right groin, allowing a synthetic stent graft to be threaded by way of a catheter through the femoral artery to repair the lesion (see Figure 2). EVR generally takes two to five hours, followed by a two- to five-day hospital stay. EVR is usually recommended for patients who are at high risk for complications from open operations because of severe cardiopulmonary disease or other risk factors, such as advanced age, morbid obesity, or a history of multiple abdominal operations.1,2,4,19

Prognosis

Patients with a ruptured AAA have a survival rate of less than 50%, with most deaths occurring before surgical repair has been attempted.3,31 In patients with kidney failure resulting from AAA (whether ruptured or unruptured, an AAA can disrupt renal blood flow), the chance for survival is poor. By contrast, the risk for death during surgical graft repair of an AAA is only about 2% to 8%.1,12

In a systematic review, EVR was associated with a lower 30-day mortality rate compared with open surgical repair (1.6% vs 4.7%, respectively), but this reduction did not persist over two years’ follow-up; neither did EVR improve overall survival or quality of life, compared with open surgery.1 Additionally, EVR requires periodic imaging throughout the patient’s life, which is associated with more reinterventions.1,19

Patient Education

Clinicians should encourage all patients to stop smoking, follow a low-cholesterol diet, control hypertension, and exercise regularly to lower the risk for AAAs. Screening recommendations should be explained to patients at risk, as should the signs and symptoms of an aneurysm. These patients should be instructed to call their health care provider immediately if they suspect a problem.

Conclusion

The incidence of AAA is increasing, and primary care providers must be prepared to act promptly in any case of suspected AAA to ensure a safe outcome. For aneurysms measuring greater than 5.5 cm in diameter, open or endovascular surgical repair should be considered. Patients with smaller aneurysms or contraindications for surgery should receive careful medical management and education to reduce the risks of AAA expansion leading to possible rupture.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and anxiety presented with complaints of abdominal pain, localized to an area left of the umbilicus. He described the pain as constant and rated it 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. He said the pain had been present for longer than three weeks.

The man said he had been seen by another health care provider shortly after the pain began, but he did not think the provider took his complaint seriously. At that visit, antacids were prescribed, blood work was ordered, and the man was told to return if there was no improvement. He felt that because he was being treated for anxiety, the provider believed he was just imagining the pain.

At the current visit, the review of systems revealed additional complaints of shakiness and nausea without vomiting, with other findings unremarkable. The persistent pain did not seem related to eating, and the patient had no history of any surgeries that might help explain his current complaints. He had smoked a pack of cigarettes daily for 40 years and had a history of heavy alcohol use, although he denied having consumed any alcohol during the previous five years.

His prescribed medications included gemfibrozil 600 mg per day, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg each morning, and diazepam 5 mg twice daily, with an OTC antacid.

The patient’s recent laboratory results were normal; they included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver enzyme levels, and a serum amylase level. The patient weighed 280 lb and his height was 5’10”; his BMI was 40. His temperature was 97.7°F, with a regular heart rate of 88 beats/min; blood pressure, 140/90 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min.

The patient did not appear to be in acute distress. A bruit was heard in the indicated area of pain. No mass was palpated, and the width of his aorta could not be determined because of his obesity. His physical exam was otherwise normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a 5.5-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and the man was referred for immediate surgery. The aneurysm was repaired in an open abdominal procedure with a polyester prosthetic graft. The surgery was successful.

Discussion

AAA is a permanent bulging area of the aorta that exceeds 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1). It is a potentially life-threatening condition due to the possibility of rupture. Often an aneurysm is asymptomatic until it ruptures, making this a difficult illness to diagnose.1

Each year, an estimated 10,000 deaths result from a ruptured AAA, making this condition the 14th leading cause of death in the United States.2,3 Incidence of AAA appears to have increased over the past two decades. Causes for this may include the aging of the US population, an increase in the number of smokers, and a trend toward diets that are higher in fat.

Prognosis among patients with AAA can be improved with increased awareness of the disease among health care providers, earlier detection of AAAs at risk for rupture, and timely, effective interventions.

Symptomatology

In about one-third of patients with a ruptured AAA, a clinical triad of symptoms is present: abdominal and/or back pain, a pulsatile abdominal mass, and hypotension.4,5 In these cases, according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA),4 immediate surgical evaluation is indicated.

Prior to the rupture of an AAA, the patient may feel a pulsing sensation in the abdomen or may experience no symptoms at all. Some patients report vague complaints, such as back, flank, groin, or abdominal pain. Syncope may be the chief complaint as the aneurysm expands, so it is important for primary care providers to be alert to progressive symptoms, including this signal that an aneurysm may exist and may be expanding.6

Pain may also be abrupt and severe in the lower abdomen and back, including tenderness in the area over the aneurysm. Shock can develop rapidly and symptoms such as cyanosis, mottling, altered mental status, tachycardia, and hypotension may be present.1,4

Since symptoms may be vague, the differential diagnosis can be broad (see Table 14,7,8), necessitating a detailed patient history and a careful physical examination. In an elderly patient, low back pain should be evaluated for AAA.9 In addition, acute abdominal pain in a patient older than 50 should be presumed to be a ruptured AAA.8

Risk Factors

A clinician should be familiar with the risk factors for AAA so that diagnosis can be made before a rupture occurs. Male gender and age greater than 65 are important risk factors for AAA, but one of the most important environmental risks is cigarette smoking.9,10 Current smokers are more than seven times more likely than nonsmokers to have an aneurysm.10 Atherosclerosis, which weakens the wall of the aorta, is also believed to contribute to the risk for AAA.11

Other contributing factors include hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, and family history. Chronic infection, inflammatory illnesses, and connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome) can also increase the risk for aneurysm. Less frequent causes of AAA are trauma and infectious diseases, such as syphilis.1,12

In 85% of patients with femoral aneurysms, AAA has been found to coexist, as it has in 62% of patients with popliteal aneurysms. Patients previously diagnosed with these conditions should be screened for AAA.4,13,14

Diagnosis

An abdominal bruit or a pulsating mass may be found on palpation, but the sensitivity for detection of AAA is related to its size. An aneurysm greater than 5.0 cm has an 82% chance of detection by palpation.15 To assess for the presence of an abdominal aneurysm, the examiner should press the midline between the xiphoid and umbilicus bimanually, firmly but gently.12 There is no evidence to suggest that palpating the abdomen can cause an aneurysm to rupture.

The most useful tests for diagnosis of AAA are US, CT, and MRI.6 US is the simplest and least costly of these diagnostic procedures; it is noninvasive and has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of nearly 100%. Bedside US can provide a rapid diagnosis in an unstable patient.16

CT is nearly 100% effective in diagnosing AAA and is usually used to help decide on appropriate treatment, as it can determine the size and shape of the aneurysm.17 However, CT should not be used for unstable patients.

MRI is useful in diagnosing AAA, but it is expensive, and inappropriate for unstable patients. Currently, conventional aortography is rarely used for preoperative assessment but may still be used for placement of endovascular devices or in patients with renal complications.1,12

Screening Recommendations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all men ages 65 to 74 who have a lifelong history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes should be screened for AAA with abdominal US.3,18 Screening is not recommended for those younger than 65 who have never smoked, but this decision must be individualized to the patient, with other risk factors considered.

The ACC/AHA4 advises that men whose parents or siblings have a history of AAA and who are older than 60 should undergo physical examination and screening US for AAA. In addition, patients with a small AAA should receive US surveillance until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter; survival has not been shown to improve if an AAA is repaired before it reaches this size.1,2,19 In consideration of increased comorbidities and decreased life expectancy, screening is not recommended for men older than 75, but this too should be determined individually.3

Screening for women is not recommended by the USPSTF.3,18 The document states that the prevalence of large AAAs in women is low and that screening may lead to an increased number of unnecessary surgeries with associated morbidity and mortality. Clinical judgment must be used in making this decision, however, as several studies have shown that women have an AAA rupture rate that is three times higher than that in men; they also have an increased in-hospital mortality rate when rupture does occur. Thus, women are less likely to experience AAA but have a worse prognosis when AAA does develop.20-22

Management

The size of an AAA is the most important predictor of rupture. According to the ACC/AHA,4 the associated risk for rupture is about 20% for aneurysms that measure 5.0 cm in diameter, 40% for those measuring at least 6.0 cm, and at least 50% for aneurysms exceeding 7.0 cm.4,23,24 Regarding surveillance of known aneurysms, it is recommended that a patient with an aneurysm smaller than 3.0 cm in diameter requires no further testing. If an AAA measures 3.0 to 4.0 cm, US should be performed yearly; if it is 4.0 to 4.9 cm, US should be performed every six months.4,25

If an identified AAA is larger than 4.5 cm, or if any segment of the aorta is more than 1.5 times the diameter of an adjacent section, referral to a vascular surgeon for further evaluation is indicated. The vascular surgeon should be consulted immediately regarding a symptomatic patient with an AAA, or one with an aneurysm that measures 5.5 cm or larger, as the risk for rupture is high.4,26

Preventing rupture of an AAA is the primary aim in management. Beta-blockers may be used to reduce systolic hypertension in cardiac patients, thus slowing the rate of expansion in those with aortic aneurysms. Patients with a known AAA should undergo frequent monitoring for blood pressure and lipid levels and be advised to stop smoking. Smoking cessation interventions such as behavior modification, nicotine replacement, or bupropion should be offered.27,28

There is evidence that statin use may reduce the size of aneurysms, even in patients without hypercholesterolemia, possibly due to statins’ anti-inflammatory properties.22,29 ACE inhibitors may also be beneficial in reducing AAA growth and in lowering blood pressure. Antiplatelet medications are important in general cardiovascular risk reduction in the patient with AAA. Aspirin is the drug of choice.27,29

Surgical Repair

AAAs are usually repaired by one of two types of surgery: endovascular repair (EVR) or open surgery. Open surgical repair, the more traditional method, involves an incision into the abdomen from the breastbone to below the navel. The weakened area is replaced with a graft made of synthetic material. Open repair of an intact AAA, performed under general anesthesia, takes from three to six hours, and the patient must be hospitalized for five to eight days.30

In EVR, the patient is given epidural anesthesia and an incision is made in the right groin, allowing a synthetic stent graft to be threaded by way of a catheter through the femoral artery to repair the lesion (see Figure 2). EVR generally takes two to five hours, followed by a two- to five-day hospital stay. EVR is usually recommended for patients who are at high risk for complications from open operations because of severe cardiopulmonary disease or other risk factors, such as advanced age, morbid obesity, or a history of multiple abdominal operations.1,2,4,19

Prognosis

Patients with a ruptured AAA have a survival rate of less than 50%, with most deaths occurring before surgical repair has been attempted.3,31 In patients with kidney failure resulting from AAA (whether ruptured or unruptured, an AAA can disrupt renal blood flow), the chance for survival is poor. By contrast, the risk for death during surgical graft repair of an AAA is only about 2% to 8%.1,12

In a systematic review, EVR was associated with a lower 30-day mortality rate compared with open surgical repair (1.6% vs 4.7%, respectively), but this reduction did not persist over two years’ follow-up; neither did EVR improve overall survival or quality of life, compared with open surgery.1 Additionally, EVR requires periodic imaging throughout the patient’s life, which is associated with more reinterventions.1,19

Patient Education

Clinicians should encourage all patients to stop smoking, follow a low-cholesterol diet, control hypertension, and exercise regularly to lower the risk for AAAs. Screening recommendations should be explained to patients at risk, as should the signs and symptoms of an aneurysm. These patients should be instructed to call their health care provider immediately if they suspect a problem.

Conclusion

The incidence of AAA is increasing, and primary care providers must be prepared to act promptly in any case of suspected AAA to ensure a safe outcome. For aneurysms measuring greater than 5.5 cm in diameter, open or endovascular surgical repair should be considered. Patients with smaller aneurysms or contraindications for surgery should receive careful medical management and education to reduce the risks of AAA expansion leading to possible rupture.

1. Wilt TJ, Lederle FA, MacDonald R, et al; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparison of Endovascular and Open Surgical Repairs for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. AHRQ publication 06-E107. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 144. www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/tp/aaareptp.htm. Accessed June 23, 2009.

2. Birkmeyer JD, Upchurch GR Jr. Evidence-based screening and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):749-750.

3. Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203-211.

4. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1239-1312.

5. Kiell CS, Ernst CB. Advances in management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Adv Surg. 1993;26:73–98.

6. O’Connor RE. Aneurysm, abdominal. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/756735-overview. Accessed June 23, 2009.

7. Lederle FA, Parenti CM, Chute EP. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: the internist as diagnostician. Am J Med. 1994;96:163-167.

8. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(7): 971-978.

9. Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1537-1544.

10. Wilmink TB, Quick CR, Day NE. The association between cigarette smoking and abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(6):1099-1105.

11. Palazzuoli P, Gallotta M, Guerrieri G, et al. Prevalence of risk factors, coronary and systemic atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm: comparison with high cardiovascular risk population. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(4):877-883.

12. Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577-1589.

13. Graham LM, Zelenock GB, Whitehouse WM Jr, et al. Clinical significance of arteriosclerotic femoral artery aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1980;115(4):502–507.

14. Whitehouse WM Jr, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, et al. Limb-threatening potential of arteriosclerotic popliteal artery aneurysms. Surgery. 1983;93(5):694–699.

15. Fink HA, Lederle FA, Roth CS, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833-836.

16. Bentz S, Jones J. Accuracy of emergency department ultrasound scanning in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):803-804.

17. Kvilekval KH, Best IM, Mason RA, et al. The value of computed tomography in the management of symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12(1):28-33.

18. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):198-202.

19. Lederle FA, Kane RL, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):735-741.

20. McPhee JT, Hill JS, Elami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001-2004. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(5):891-899.

21. Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J, et al. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2007;94(3):310-314.

22. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2865-2869.

23. Englund R, Hudson P, Hanel K, Stanton A. Expansion rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(1):21–24.

24. Conway KP, Byrne J, Townsend M, Lane IF. Prognosis of patients turned down for conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the endovascular and sonographic era: Szilagyi revisited? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(4):752–757.

25. Cook TA, Galland RB. A prospective study to define the optimum rescreening interval for small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4(4):441–444.

26. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Association of Vascular Surgery; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(1):267-269.

27. Golledge J, Powell JT. Medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;4(3):267-273.

28. Sule S, Aronow WS. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Compr Ther. 2009;35(1):3-8.

29. Powell JT. Non-operative or medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg. 2008;97(2): 121-124.

30. Huber TS, Wang JG, Derrow AE, et al. Experience in the United States with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2):304-310.

31. Adam DJ, Mohan IV, Stuart WP, et al. Community and hospital outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm within the catchment area of a regional vascular surgical service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(5):922-928.

1. Wilt TJ, Lederle FA, MacDonald R, et al; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparison of Endovascular and Open Surgical Repairs for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. AHRQ publication 06-E107. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 144. www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/tp/aaareptp.htm. Accessed June 23, 2009.

2. Birkmeyer JD, Upchurch GR Jr. Evidence-based screening and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):749-750.

3. Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203-211.

4. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1239-1312.

5. Kiell CS, Ernst CB. Advances in management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Adv Surg. 1993;26:73–98.

6. O’Connor RE. Aneurysm, abdominal. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/756735-overview. Accessed June 23, 2009.

7. Lederle FA, Parenti CM, Chute EP. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: the internist as diagnostician. Am J Med. 1994;96:163-167.

8. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(7): 971-978.

9. Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1537-1544.

10. Wilmink TB, Quick CR, Day NE. The association between cigarette smoking and abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(6):1099-1105.

11. Palazzuoli P, Gallotta M, Guerrieri G, et al. Prevalence of risk factors, coronary and systemic atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm: comparison with high cardiovascular risk population. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(4):877-883.

12. Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577-1589.

13. Graham LM, Zelenock GB, Whitehouse WM Jr, et al. Clinical significance of arteriosclerotic femoral artery aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1980;115(4):502–507.

14. Whitehouse WM Jr, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, et al. Limb-threatening potential of arteriosclerotic popliteal artery aneurysms. Surgery. 1983;93(5):694–699.

15. Fink HA, Lederle FA, Roth CS, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833-836.

16. Bentz S, Jones J. Accuracy of emergency department ultrasound scanning in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):803-804.

17. Kvilekval KH, Best IM, Mason RA, et al. The value of computed tomography in the management of symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12(1):28-33.

18. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):198-202.

19. Lederle FA, Kane RL, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):735-741.

20. McPhee JT, Hill JS, Elami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001-2004. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(5):891-899.

21. Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J, et al. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2007;94(3):310-314.

22. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2865-2869.

23. Englund R, Hudson P, Hanel K, Stanton A. Expansion rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(1):21–24.

24. Conway KP, Byrne J, Townsend M, Lane IF. Prognosis of patients turned down for conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the endovascular and sonographic era: Szilagyi revisited? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(4):752–757.

25. Cook TA, Galland RB. A prospective study to define the optimum rescreening interval for small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4(4):441–444.

26. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Association of Vascular Surgery; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(1):267-269.

27. Golledge J, Powell JT. Medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;4(3):267-273.

28. Sule S, Aronow WS. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Compr Ther. 2009;35(1):3-8.

29. Powell JT. Non-operative or medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg. 2008;97(2): 121-124.

30. Huber TS, Wang JG, Derrow AE, et al. Experience in the United States with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2):304-310.

31. Adam DJ, Mohan IV, Stuart WP, et al. Community and hospital outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm within the catchment area of a regional vascular surgical service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(5):922-928.

Botanical Briefs: Common Ivy (Hedera helix)

Multiple Congenital Plaquelike Glomuvenous Malformations With Type 2 Segmental Involvement

Potential caregivers for homebound elderly: More numerous than supposed?

Background This qualitative study examined the experiences and perspectives of caregivers of homebound elderly patients.

Methods We performed in-depth, semistructured interviews with 22 caregivers (average age 59 years) of homebound elderly patients and analyzed them to determine major themes. The homebound patients were part of a house call program of a US academic medical center in Baltimore, Maryland.

Results Caregiver relationships in our study were diverse: 41% were spouses or children, and 41% were unrelated to the homebound patient; 36% were male. We identified 3 themes: (1) caregiving has both positive and negative aspects, (2) caregiver motivation is heterogeneous, and (3) caregivers sometimes undergo transformation as a result of their caregiving experience.

Conclusion Caregiver experience is varied. Interviewees reported a variety of motivations for becoming caregivers and both positive and negative aspects of the experience. Caregivers in this study were diverse with respect to sex and relationship to the patient, suggesting the pool of potential caregivers may be larger than previously thought.

When thinking about long-term home care for the chronically ill elderly, many people automatically imagine a spouse or child as the primary caregiver. In our study, however, 41% of the caregivers interviewed were unrelated to the person receiving the care. In addition to this diversity, we found that motivations for providing care varied among participants; that their different experiences ranged from positive to negative, or a little of both; and that a few caregivers felt their attitudes changed for the better over the course of giving assistance.

We must plan for an aging population

In 2000, 35 million people, or 8% of the US population, were 65 years of age or older. In 2040, there will be 80 million seniors, or 20.4% of the US population.1 The National Long Term Care Survey found that in 1999, 3.9 million Medicare enrollees with a chronic disability were receiving care in their homes. A significant portion of caregiving burden is borne by patients’ relatives and friends; more than 90% of homebound patients were receiving some degree of informal, unpaid assistance.2 As the population ages, more caregivers will be needed to tend chronically ill elders, and most will be informal caregivers.

The reason for our study

Research over the past few decades has found that the burden is significant for those caring for older adults.3-6 Daily challenges and stressors increase the burden caregivers feel in their role.7,8 More recent work has also examined interventions to alleviate caregiver burden.9 Studies of caregivers—published predominately in the social science and nursing literature—have seldom reported on the positive aspects of the role.10-12 Only 1 study in the US medical literature, a national survey, noted positive aspects of the caregiving role.13

Through in-depth interviews, we sought to learn more fully about the experiences of caregivers of chronically ill homebound elderly people.

Methods

Design, setting, study population

This qualitative study of caregivers, a focused ethnography,14 was part of a larger project that interviewed the patients and their doctors. We conducted the study through the Johns Hopkins Geriatrics Center Elder Housecall Program (EHP) from 1997 to 2001. Since 1979, EHP has provided medical and nursing care to generally frail, homebound elderly (mean age 77), predominantly white (82%) and female (69%) patients in a largely blue-collar community in east Baltimore. Annual mortality for patients is 25%.15 We selected a qualitative approach because we wanted to learn more about the experiences and perspectives of the caregivers.

Sampling

The parent study used a purposive and probabilistic sampling strategy to select patients, as described elsewhere.16,17 We found subjects for our caregiver study through the patients, who identified the individuals who assist them. The range of caregiver responsibilities included, but was not limited to, coordinating services, managing medical and financial affairs, and directing such activities as bathing, dressing, and meal preparation. All caregivers we invited to participate did so.

Measurements

We conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews lasting approximately 1 hour. We also collected demographic information. As a starting point for each interview, we used the following brief guide:

- What has your experience as a caregiver for the patient been like?

- Do you recall any particular examples of rewarding aspects of the role?

- Do you recall any particular examples of difficult aspects of the role?

- Are there any particular challenges or important issues in your relationship with the patient that you wish to share?

An investigator trained in qualitative research (JC) asked additional questions, as needed, to further explore caregiver responses. We gave interviewees considerable latitude in commenting on points or topics they considered relevant.

Analysis

Two of this study’s authors (JC, JM) audiotaped, transcribed, and independently coded the interviews, and compared them for agreement. We used an editing style analysis.18 Thematic categories and subcategories became apparent during coding, and we modified them as the interviewing proceeded. We examined and conceptually organized the categories, using the qualitative research software program NUD*IST 4 (Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty Ltd, Victoria, Australia) to facilitate data management and analysis.

A consensus approach

At least 2 investigators participated in each step of the analysis (eg, reading and coding of transcripts; identification, modification, conceptual organization of categories; and selection of themes for presentation). The team made all decisions by consensus.

Human subjects research approval

A Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study, and we obtained written informed consent from all study participants.

Results

We interviewed 22 caregivers (TABLE 1). The number of caregivers per patient ranged from 0 to 3 (20 patients altogether). Most patients had 1 caregiver, but several had 2 or 3. Sixteen interviews involved 1 caregiver, and 3 involved caregiver teams. The average age of the caregivers was 59.3 years, and they had known the patients for an average of 37.4 years. Fourteen of the 22 caregivers (63.6%) were female (a finding similar to results from a Kaiser Family Foundation study in 1998 of 1002 caregivers, in which 64% of the 511 primary caregivers were female).19 Nine of the 22 (40.9%) participants were unrelated to the patient. Caregivers were primarily unpaid relatives or friends (77.3%), but compensated individuals were also included.

Three major themes emerged from analysis of the interview transcripts: (1) positive and negative experiences of caregiving, (2) caregiver motivation, and (3) caregiver transformation. Representative quotes are used to illustrate the themes presented. Specific examples of these themes are shown in TABLE 2.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of the caregivers we interviewed

| Sex | |

| Female | 14/22 (63.6%) |

| Average age | |

| 59.3 years | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 19/22 (86.4%) |

| African American | 3/22 (13.6%) |

| Average length of relationship with patient | |

| 37.4 years | |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Related | 13/22 (59.1%) |

| 1 wife 4 sons 4 daughters 2 grandchildren 1 daughter-in-law 1 grandson-in-law | |

| Unrelated | 9/22 (40.9%) |

| 4 friends (1 paid) 3 paid professional caregivers 1 paid nonprofessional caregiver 1 distant nonblood relative | |

TABLE 2

Common caregiver themes that emerged during interviews

Positive aspects of caregiving

| Negative aspects of caregiving

|

Caregiver motivations

| Caregiver transformation

|

Positive and negative aspects of caregiving

Caregivers described very different experiences of their roles—some only negative, some only positive, and others both positive and negative. Accounts of 6 of the 22 interviewees were essentially value-neutral.

Negative aspects of caregiving. Seven of 22 caregivers reported only negative feelings toward their role, including feeling burdened.

A 62-year-old retired son described how caring for his mother adversely affected his life:

Yeah, I sleep here. I don’t even go to my bed. I haven’t been to bed in over 3 years, because…if I don’t go down as soon as she rings the bell, she can’t hold her water.… I used to go out to Pennsylvania and go up in the battlefield there. I used to go down Skyline Drive, places like that. I can’t do that anymore.

Positive aspects of caregiving. Four caregivers addressed only positive aspects of caregiving.

A 71-year-old retired secretary who was asked if she had encountered any difficulties in caring for her friend said:

I haven’t had any. We’ve become very close friends and her friendship means a lot…I don’t think there’s any problems with going up there…Because I call her before I go to the grocery store to make sure she’s got everything on the list and then I go and just take it up to her and do from there.

Mixed experiences with caregiving. Five of our participants discussed both positive and negative aspects of caregiving; 4 of these 5 lived with the patient.

A 47-year-old machine technician who cared for his grandmother described the benefits his 16-year-old son was receiving from the caregiving arrangement:

It’s been a plus for him to have his great-grandmother living here. I think he enjoys her company, the little stories that go along and plus they always had a good relationship when he was a small child…I would hope he would realize the importance of family and I feel we’re losing that in our society, we’re losing our family. Seems like everybody is moving away and not being associated as close as probably we once were, and you know you realize that sometimes people need a little bit of help and not to be as selfish as you would want to be and maybe learn from that that we all kind of need one another at one time and not to be so independent, like it seems like our society has gone.

He also identified negative aspects of caregiving, including the burdens associated with selling his grandmother’s home and helping her settle into his family’s home:

For the last year it has been kind of hectic with trying to make things easier, doing what needs to be done, taking care of her house. Now that that’s out of the way, that’s a big burden out of the way.

Caregiver motivations

Eight caregivers shared their motivations for deciding to care for a homebound relative or friend. These comments were unsolicited and unexpected. Four caregivers believed they were repaying the patient for help received earlier in life.

A 69-year-old daughter-in-law said the following:

I say to her the same thing I said to my mother: “You took care of me when I was little and I am taking care of you. Now it is my turn.”…I mean we are put on this earth for a purpose and I figure this is our purpose. God put us down here to take care of someone or to help someone.

Potential for caregiver transformation

Another unexpected finding from our study was that 3 interviewees reported that they or their family members were changed by the caregiving experience. Transformations included changing one’s outlook on life, changing one’s views of the caregiving role, and being able to better cope with the death of others.

A 59-year-old homemaker related how her feelings about caregiving changed over time, and she felt she was repaying her mother for help she herself had received:

My major thing in the beginning was I really felt dumped on, like you have to do this whether you want to or not to prevent her from going in a place she didn’t want to go to. But then, after a while, I didn’t feel that way no more because she helped me when I needed help, when my kids were little. She was always there for me.

Discussion

While the medical literature to date has focused on the burdens and difficulties of caregiving, our study shows that caregivers have positive as well as negative experiences in their roles, and that, for some, the experience is a complex mixture of burdens and benefits. Interestingly, 4 of the 5 caregivers who experienced that mixture lived with the patient, suggesting that proximity and increased exposure may result in a more complex experience. In addition to these findings, some caregivers have different motivations for providing care. A small number even describe the experience as transformative.

These findings are consistent with a few studies from the nursing and social science literature that address the positive aspects of caregiving.11,20 For example, 2 studies found that caregivers of patients with dementia experienced both positive and negative aspects of their role.10,12 A recent analysis of a national survey of caregivers noted that two-thirds had feelings of personal reward.13

How can you support caregivers? A deeper understanding of caregivers’ diverse motivations and experiences can help physicians prepare others for this important role, and support and encourage those who are already caring for someone.

You can offer support by discussing with current and prospective caregivers the possibility that the role may bring both positive and negative experiences.

It may also be helpful to describe the potentially transformative nature of caregiving—to point out that some people report that their negative feelings have become more positive in time. In the end, care of dependent elderly patients may improve with such awareness.

Pool of potential caregivers larger than expected. Another finding of our study is the diversity of caregivers. Only 9 of the 22 caregivers interviewed were spouses or children, and only 5 of these 9 were wives or daughters. Among the children, there were just as many sons as daughters. Grandchildren were also represented, and 41% of the caregivers were unrelated to the patient.

Traditionally, many health professionals and the public have looked to female adult children or spouses to care for patients, and the literature on the caregiver experience often represents their views. However, some studies have noted that friends and others are also involved.21 Our finding adds to an evolving understanding that potential caregivers for the homebound elderly can be drawn from a broader pool than first-degree, female relatives.

Limitations of this study. The study sample was small—22 caregivers who live in a particular section of the greater Baltimore metropolitan area. In addition, most of the caregivers were Caucasian and thus do not reflect the ethnic diversity of the United States. As such, we must be cautious in extrapolating these findings to other caregivers in other settings. Nevertheless, we believe that aspects of the caregiver experience reported here will ring true to caregivers who live elsewhere.

Americans are living longer, and many of them have chronic medical problems. An increasing percentage of these elderly will require some level of caregiving to stay in their homes. Future studies might explore in more depth caregiver motivations and caregiver transformation to gain better insight into these important issues.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Carrese received support for this project from the Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars Program.

Correspondence

Laura A. Hanyok, MD, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, 5501 Hopkins Bayview Circle, Room 1B.45, Baltimore, MD 21224; lhanyok2@jhmi.edu.

1. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics: 2006 older Americans update: key indicator of wellness. Available at: http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/Data_2006.aspx. Accessed June 13, 2008.

2. Wolff JL, Kasper JD. Caregivers of frail elders: updating a national profile. Gerontologist. 2006;46:344-356.

3. Brody EM. The Donald P. Kent Memorial Lecture. Parent care as a normative family stress. Gerontologist. 1986;25:19-29.

4. George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver well-being: A multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. Gerontologist. 1986;26:253-259.

5. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649-655.

6. Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: A longitudinal study. Gerontologist. 1986;26:260-266.

7. Öhman M, Seidenberg S. The experiences of close relatives living with a person with serious chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:396-410.

8. Sawatzky JE, Fowler-Kerry S. Impact of caregiving: listening to the voice of informal caregivers. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2003;10:277-286.

9. Yin T, Zhou Q, Bashford C. Burden on family members: Caring for frail elderly: a meta-analysis of interventions. Nurs Res. 2002;51:199-208.

10. Andrén S, Elmståhl S. Family caregivers’ subjective experiences of satisfaction in dementia care: aspects of burden, subjective health and sense of coherence. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19:157-168.

11. Riedel SE, Fredman L, Langenberg P. Associations among caregiving difficulties, burden, and rewards in caregivers to older post-rehabilitation patients. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:165-174.

12. Sanders S. Is the glass half empty or half full? Reflections on strain and gain in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;40:57-73.

13. Wolff JL, Dy SM, Frick KD, et al. End-of-life care: findings from a national survey of informal caregivers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:40-46.

14. Muecke MA. On the evaluation of ethnographies. In: Morse J, ed. Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1994:198-199.

15. Tsuji I, Fox-Whalen S, Finucane TE. Predictors of nursing home placement in community-based long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:761-766.

16. Carrese JA, Mullaney JL, Faden RR, et al. Planning for death but not serious future illness: Qualitative study of housebound elderly patients. BMJ. 2002;325:125-127.

17. Russell BH. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1994:95-96.

18. Crabtree BF, Mille WL. Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992:18.

19. Donelan K, Hill CA, Hoffman C, et al. Challenged to care: informal caregivers in a changing health system. Health Affairs. 2002. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/21/4/222. Accessed June 9, 2009.

20. Jarvis A, Worth A, Porter M. The experience of caring for someone over 75 years of age: results from a Scottish General Practice. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1450-1459.

21. Grunfield E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family caregiver burden; Results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patient and their principal caregivers. CMAJ. 2004;170:1795-1801.

Background This qualitative study examined the experiences and perspectives of caregivers of homebound elderly patients.

Methods We performed in-depth, semistructured interviews with 22 caregivers (average age 59 years) of homebound elderly patients and analyzed them to determine major themes. The homebound patients were part of a house call program of a US academic medical center in Baltimore, Maryland.

Results Caregiver relationships in our study were diverse: 41% were spouses or children, and 41% were unrelated to the homebound patient; 36% were male. We identified 3 themes: (1) caregiving has both positive and negative aspects, (2) caregiver motivation is heterogeneous, and (3) caregivers sometimes undergo transformation as a result of their caregiving experience.

Conclusion Caregiver experience is varied. Interviewees reported a variety of motivations for becoming caregivers and both positive and negative aspects of the experience. Caregivers in this study were diverse with respect to sex and relationship to the patient, suggesting the pool of potential caregivers may be larger than previously thought.

When thinking about long-term home care for the chronically ill elderly, many people automatically imagine a spouse or child as the primary caregiver. In our study, however, 41% of the caregivers interviewed were unrelated to the person receiving the care. In addition to this diversity, we found that motivations for providing care varied among participants; that their different experiences ranged from positive to negative, or a little of both; and that a few caregivers felt their attitudes changed for the better over the course of giving assistance.

We must plan for an aging population

In 2000, 35 million people, or 8% of the US population, were 65 years of age or older. In 2040, there will be 80 million seniors, or 20.4% of the US population.1 The National Long Term Care Survey found that in 1999, 3.9 million Medicare enrollees with a chronic disability were receiving care in their homes. A significant portion of caregiving burden is borne by patients’ relatives and friends; more than 90% of homebound patients were receiving some degree of informal, unpaid assistance.2 As the population ages, more caregivers will be needed to tend chronically ill elders, and most will be informal caregivers.

The reason for our study

Research over the past few decades has found that the burden is significant for those caring for older adults.3-6 Daily challenges and stressors increase the burden caregivers feel in their role.7,8 More recent work has also examined interventions to alleviate caregiver burden.9 Studies of caregivers—published predominately in the social science and nursing literature—have seldom reported on the positive aspects of the role.10-12 Only 1 study in the US medical literature, a national survey, noted positive aspects of the caregiving role.13

Through in-depth interviews, we sought to learn more fully about the experiences of caregivers of chronically ill homebound elderly people.

Methods

Design, setting, study population