User login

Perceptions of Hospital Discharge Software

During the transition from inpatient to outpatient care, patients are vulnerable to adverse events.1 Poor communication between hospital personnel and either the patient or the outpatient primary care physician has been associated with preventable or ameliorable adverse events after discharge.1 Systematic reviews confirm that discharge communication is often delayed, inaccurate, or ineffective.2, 3

Discharge communication failures may occur if hospital processes rely on dictated discharge summaries.2 For several reasons, discharge summaries are inadequate for communication. Most patients complete their initial posthospital clinic visit before their primary care physician receives the discharge summary.4 For many patients, the discharge summary is unavailable for all posthospital visits.4 Discharge summaries often fail as communication because they are not generated or transmitted.4

Recommendations to improve discharge communication include the use of health information technology.2, 5 The benefits of computer‐generated discharge summaries include decreases in delivery time for discharge communications.2 The benefits of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) include reduction of medical errors.6 These theoretical benefits create a rationale for clinical trials to measure improvements after discharge software applications with CPOE.5

In an effort to improve discharge communication and clinically relevant outcomes, we performed a cluster‐randomized trial to assess the value of a discharge software application of CPOE. The clustered design followed recommendations from a systematic review of discharge interventions.3 We applied our research intervention at the physician level and measured outcomes at the patient level. Our objective was to assess the benefit of discharge software with CPOE vs. usual care when used to discharge patients at high risk for repeat admission. In a previous work, we reported that discharge software did not reduce rates of hospital readmission, emergency department visits, or postdischarge adverse events due to medical management.7 In the present article, we compare secondary outcomes after the research intervention: perceptions of the discharge from the perspectives of patients, primary care physicians, and hospital physicians.

Methods

The trial design was a cluster randomized, controlled trial. The setting was the postdischarge environment following index hospitalization at a 730‐bed, tertiary care, teaching hospital in central Illinois. The Peoria Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for human research.

Participants

We enrolled consenting hospital physicians and their patients between November 2004 and January 2007. The hospital physician defined the cluster. Patients discharged by the physician comprised the cluster. The eligibility criteria for hospital physicians required internal medicine resident or attending physicians with assignments to inpatient duties for at least 2 months during the 27‐month enrollment period. After achieving informed consent from physicians, research personnel screened all consecutive, adult inpatients who were discharged to home. Patient inclusion required a probability of repeat admission (Pra) equal to or greater than 0.40.8, 9 The purpose of the inclusion criterion was to enrich the sample with patients likely to benefit from interventions to improve discharge processes. Furthermore, hospital readmission was the primary endpoint of the study, as reported separately.7 The Pra came from a predictive model with scores for age, gender, prior hospitalizations, prior doctor visits, self‐rated health status, presence of informal caregiver in the home, and comorbid coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus. Research coordinators calculated the Pra within 2 days before discharge from the index hospitalization.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded patients previously enrolled in the study, candidates for hospice, and patients unable to participate in outcome ascertainment. Cognitive impairment was a conditional exclusion criterion for patients. We defined cognitive impairment as a score less than 9 on the 10‐point clock test.10 Patients with cognitive impairment participated only with consent from their legally authorized representative. We enrolled patients with cognitive impairment only if a proxy spent at least 3 hours daily with the patient and the proxy agreed to answer postdischarge interviews. If a patient's outpatient primary care physician treated the patient during the index hospitalization, then there was no perceived barrier in physician‐to‐physician communication and we excluded the patient.

Intervention

The research intervention was discharge software with CPOE. Detailed description of the software appeared previously.5 In summary, the CPOE software application facilitated communication at the time of hospital discharge to patients, retail pharmacists, and community physicians. The application had basic levels of clinical decision support, required fields, pick lists, standard drug doses, alerts, reminders, and online reference information. The software addressed deficiencies in the usual care discharge process reported globally and reviewed previously.5 For example, 1 deficiency occurred when inpatient physicians failed to warn outpatient physicians about diagnostic tests with results pending at discharge.11 Another deficiency was discharge medication error.12 The software prompted the discharging physician to enter pending tests, order tests after discharge, and perform medication reconciliation. On the day of discharge, hospital physicians used the software to automatically generate discharge documents and reconcile prescriptions for the patient, primary care physician, retail pharmacist, and the ward nurse. The discharge letter went to the outpatient practitioner via facsimile transmission plus a duplicate via U.S. mail.

The control intervention was the usual care, handwritten discharge process commonly used by hospitalists.2 Hospital physicians and ward nurses completed handwritten discharge forms on the day of discharge. The forms contained blanks for discharge diagnoses, discharge medications, medication instructions, postdischarge activities and restrictions, postdischarge diet, postdischarge diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and appointments. Patients received handwritten copies of the forms, 1 page of which also included medication instructions and prescriptions. In a previous publication, we provided details about the usual care discharge process as well as the standard care available to all study patients regardless of intervention.5

Randomization

The hospital physician who completed the discharge process was the unit of randomization. Random allocation was to discharge software or usual care discharge process, with a randomization ratio of 1:1 and block size of 2. We concealed allocation with the following process. An investigator who was not involved with hospital physician recruitment generated the randomization sequence with a computerized random number generator. The randomization list was maintained in a secure location. Another investigator who was unaware of the next random assignment performed the hospital physician recruitment and informed consent. After confirming eligibility and obtaining informed consent from physicians, the blinded investigator requested the next random assignment from the custodian of the randomization list. Hospital physicians subsequently used their randomly assigned process when discharging their patients who enrolled in the study. After random allocation, it was not possible to conceal the test or control intervention from physicians or their patients.

Hospital physicians underwent training on the software or usual care discharge process; the details appeared previously.7 Physicians assigned to usual care did not receive training on the discharge software and were blocked from using the software. Patients were passive recipients of the research intervention performed by their discharging physician. Patients received the research intervention on the day of discharge of the index hospitalization.

Baseline Assessment

During the index hospitalization, trained data abstractors recorded baseline patient demographic data plus variables to calculate the Pra for probability for repeat admission. We recorded the availability of an informal caregiver in response to the question, Is there a friend, relative, or neighbor who would take care of you for a few days, if necessary? Data came from the patient or proxy for physical functioning, mental health,13 heart failure, and number of previous emergency department visits. Other data came from hospital records for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, number of discharge medications, and length of stay for the index hospitalization.

Outcome Assessment

We assessed the patient's perception of the discharge with 2 validated survey instruments. One week after discharge, research personnel performed telephone interviews with patients or proxies. While following a script, interviewers instructed patients to avoid mentioning the discharge process. Interviewers read items from the B‐PREPARED questionnaire.14, 15 and the Satisfaction with Information About Medicines Scale (SIMS).16 The B‐PREPARED scale assessed 3 principal components of patient preparedness for discharge: self‐care information for medications and activities, equipment and services, and confidence. The scale demonstrated internal consistency, construct validity, and predictive validity. High scale values reflected high perceptions of discharge preparedness from the patient perspective.15 SIMS measured patient satisfaction with information about discharge medications. Validation studies revealed SIMS had internal consistency, test‐retest reliability, and criterion‐related validity.16 Interviewers recorded responses to calculate a total SIMS score. Patients with high total SIMS scores had high satisfaction. While assessing B‐PREPARED and SIMS, interviewers were blind to intervention assignment. We evaluated the adequacy of blinding by asking interviewers to guess the patient's intervention assignment.

We measured the quality of hospital discharge from the outpatient physician perspective. During the index hospitalization, patients designated an outpatient primary care practitioner to receive discharge reports and results of diagnostic tests. Ten days after discharge, research personnel mailed the Physician‐PREPARED questionnaire to the designated community practitioner.17 The sum of item responses comprised the Modified Physician‐PREPARED scale and demonstrated internal consistency and construct validity. The principal components of the Modified Physician‐PREPARED were timeliness of communication and adequacy of discharge plan/transmission. High scale values reflected high perceptions of discharge quality.17 Outpatient practitioners gave implied consent when they completed and returned questionnaires. We requested 1 questionnaire for each enrolled patient, so the outcome assessment was at the patient level. The assessment was not blinded because primary care physicians received the output of discharge software or usual care discharge.

We assessed the satisfaction of hospital physicians who used the discharge software and the usual care. After hospital physicians participated in the trial for 6 months, they rated their assigned discharge process on Likert scales. The first question was, On a scale of 1 to 10, indicate your satisfaction with your portion of the discharge process. The scale anchors were 1 for very dissatisfied and 10 for very satisfied. The second question was, On a scale of 1 to 10, indicate the effort to complete your portion of the discharge process. For the second question, the scale anchors were 1 for very difficult and 10 for very easy. It was not possible to mask the hospital physicians after they received their intervention assignment. Consequently, their outcome assessment was not blinded.

Statistical Methods

The cluster number and size were selected to maintain test significance level, 1‐sided alpha less than 0.05, and power greater than 80%. We previously published the assumptions and rationale for 35 hospital physician clusters per intervention and 9 patients per cluster.7 We did not perform separate sample size estimates for the secondary outcomes reported herein.

The statistical analyses employed SPSS PC (Version 15.0.1; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical procedures for baseline variables were descriptive and included means and standard deviations (SDs) for interval variables and percentages for categorical variables. For all analyses, we employed the principle of intention‐to‐treat. We assumed patient or physician exposure to the intervention randomly assigned to the discharging physician. Analyses employed standard tests for normal distribution, homogeneity of variance, and linearity of relationships between independent and dependent variables. If assumptions failed, then we stratified variables or performed transformations. We accepted P < 0.05 as significant.

We tested hypotheses for patient‐level outcomes with generalized estimating equations (GEEs) that corrected for clustering by hospital physician. We employed GEEs because they provide unbiased estimates of standard errors for parameters even with incorrect specification of the intracluster dependence structure.18 Each patient‐level outcome was the dependent variable in a separate GEE. The intervention variable for each GEE was discharge software vs. usual care, handwritten discharge. The statistic of interest was the coefficient for the intervention variable. The null hypothesis was no difference between discharge software and usual care. The statistical definition of the null hypothesis was an intervention variable coefficient with a 95% confidence interval (CI) that included 0.

For analyses that were unaffected by the cluster assumption, we performed standard tests. The hypothesis for hospital physicians was significantly higher satisfaction for discharge software users and the inferential procedure was the t test. When we assessed the success of the study blinding, we assumed no association between true intervention allocation and guesses by outcome assessors. We used chi‐square for assessment of the blinding.

Results

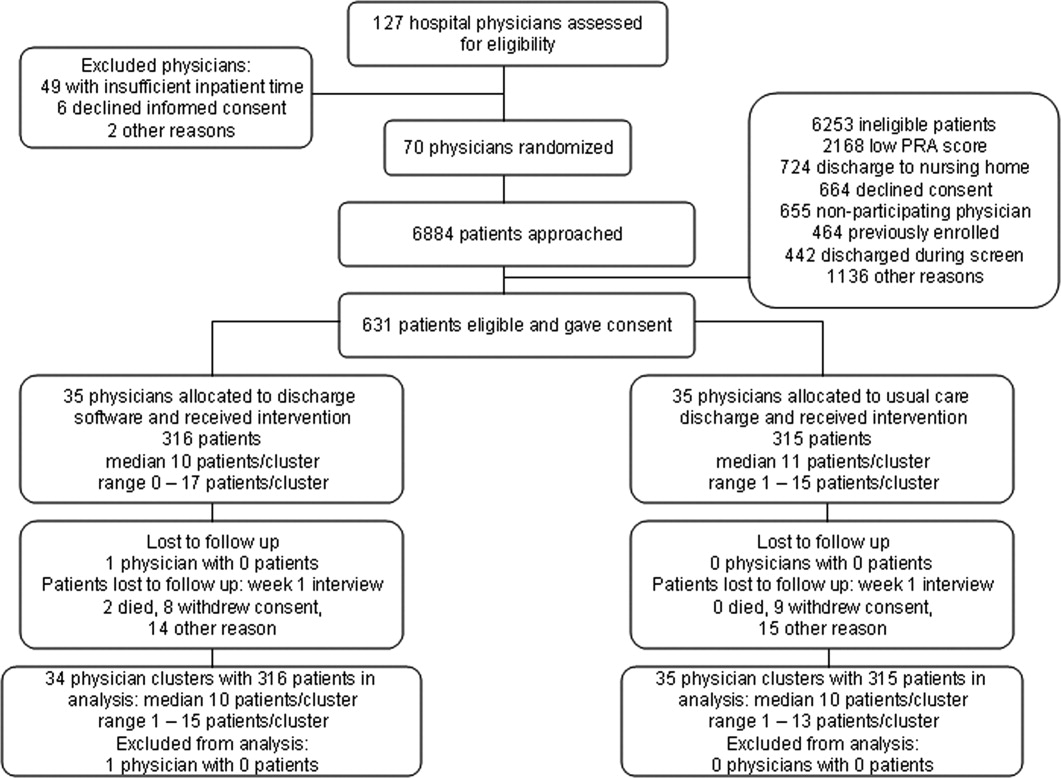

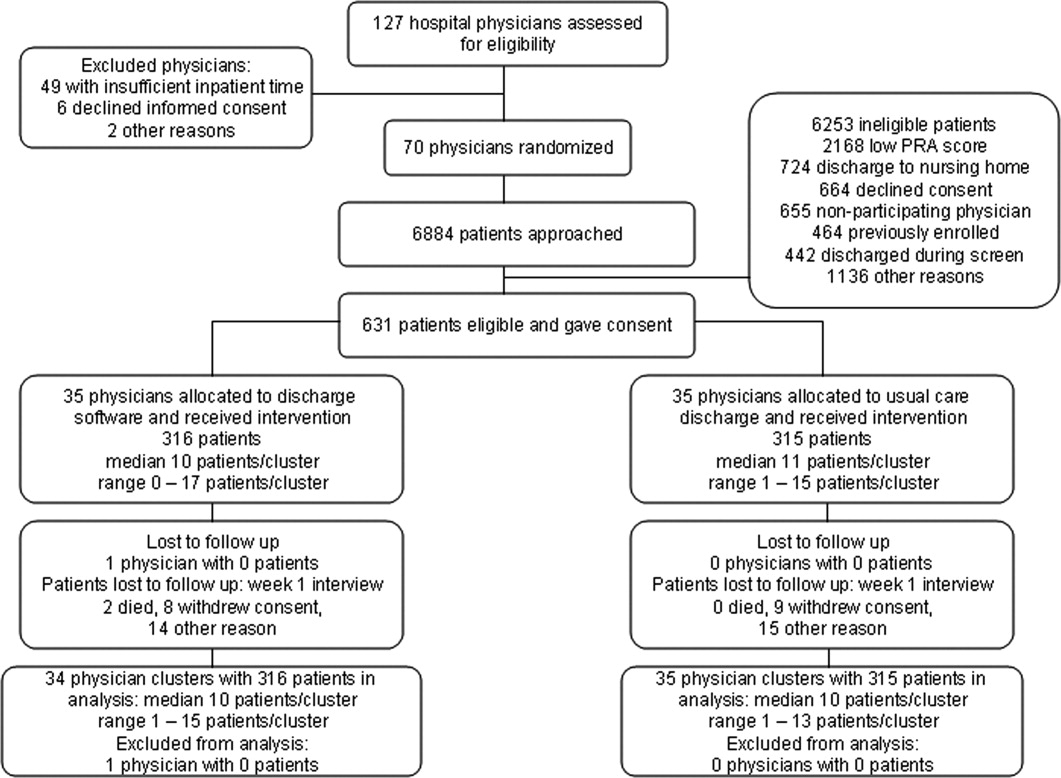

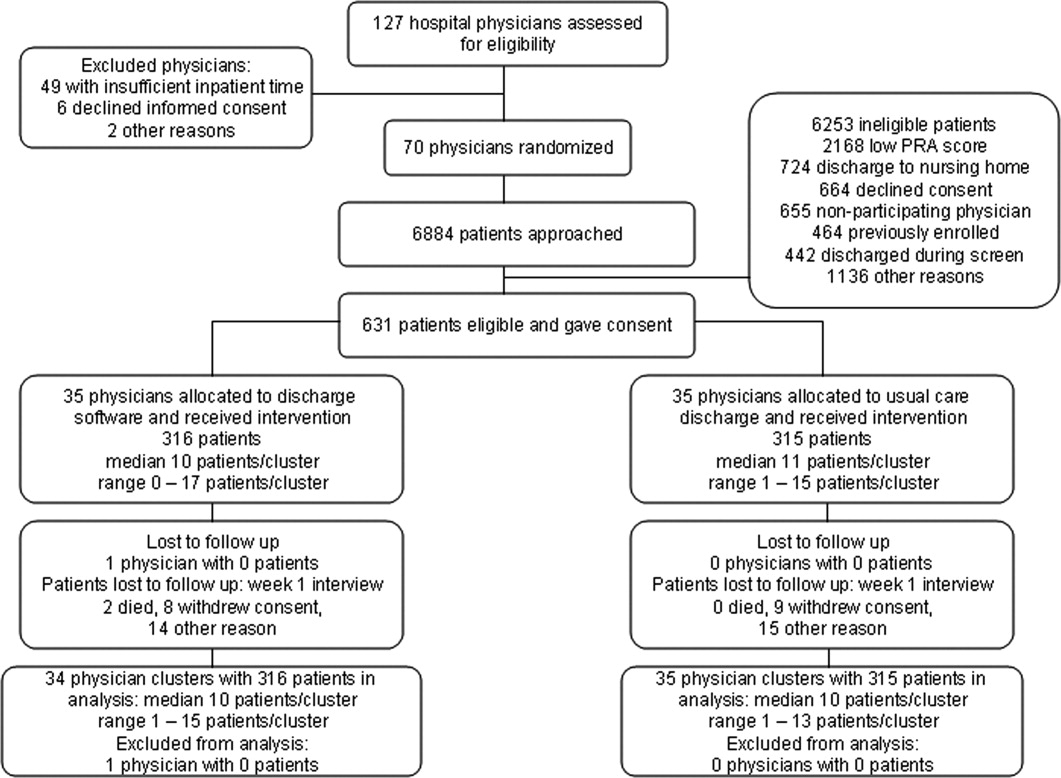

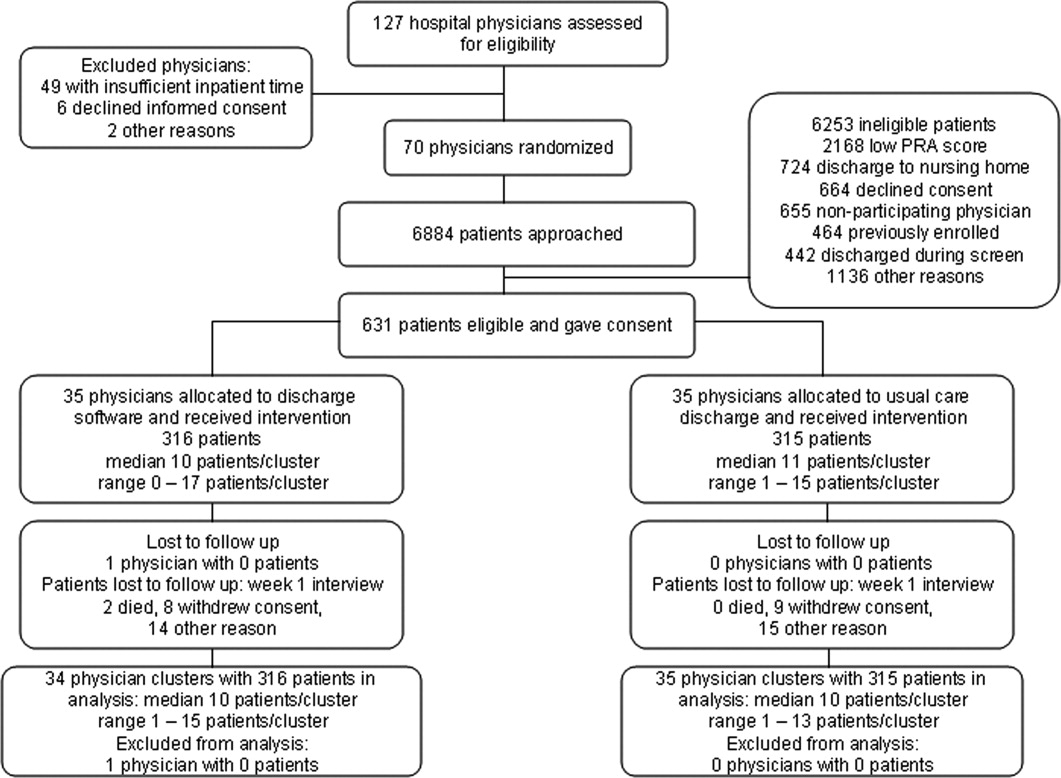

We screened 127 physicians who were general internal medicine hospital physicians. Seventy physicians consented and received random allocation to discharge software or usual care. We excluded 57 physicians for reasons shown in the trial flow diagram (Figure 1). We approached 6884 patients during their index hospitalization. After excluding 6253 ineligible patients, we enrolled 631 willing patients (Supplementary Appendix). As depicted in Figure 1, the most common reason for ineligibility occurred for patients with Pra score <0.40 (2168/6253 exclusions; 34.7%). We followed 631 patients who received the discharge intervention (Figure 1). There was no differential dropout between the interventions. Protocol deviations were rare, 0.5% (3/631). Three patients erroneously received usual care discharge from physicians assigned to discharge software. All 631 patients were included in the intention‐to‐treat analysis. The baseline characteristics of the randomly assigned hospital physicians and their patients are in Table 1. Most of the hospital physicians were residents in the first year of postgraduate training.

| Discharge Software | Usual Care | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Hospital physician characteristics, n (%) | n = 35 | n = 35 |

| Postgraduate year 1 | 18 (51.4) | 23 (65.7) |

| Postgraduate years 2‐4 | 10 (28.6) | 7 (20.0) |

| Attending physician | 7 (20.0) | 5 (14.3) |

| Patient characteristics, n (%) | n = 316 | n = 315 |

| Gender, male | 136 (43.0) | 147 (46.7) |

| Age, years | ||

| 18‐44 | 68 (21.5) | 95 (30.2) |

| 45‐54 | 79 (25.0) | 76 (24.1) |

| 55‐64 | 86 (27.2) | 74 (23.5) |

| 65‐98 | 83 (26.3) | 70 (22.2) |

| Self‐rated health status | ||

| Poor | 82 (25.9) | 108 (34.3) |

| Fair | 169 (53.5) | 147 (46.7) |

| Good | 54 (17.1) | 46 (14.6) |

| Very good | 10 (3.2) | 11 (3.5) |

| Excellent | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 172 (54.4) | 177 (56.2) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||

| None | 259 (82.0) | 257 (81.6) |

| Without oral steroid or home oxygen | 28 (8.9) | 26 (8.3) |

| With chronic oral steroid | 10 (3.2) | 8 (2.5) |

| With home oxygen oral steroid | 19 (6.0) | 24 (7.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 133 (42.1) | 120 (38.1) |

| Heart failure | 80 (25.3) | 67 (21.3) |

| Physical Functioning from SF‐36 | ||

| Lowest third | 128 (40.5) | 121 (38.4) |

| Upper two‐thirds | 188 (59.5) | 194 (61.6) |

| Mental Health from SF‐36 | ||

| Lowest one‐third | 113 (35.8) | 117 (37.1)* |

| Upper two‐thirds | 203 (64.2) | 197 (62.5)* |

| Emergency department visits during 6 months before index admission | ||

| 0 or 1 | 194 (61.4) | 168 (53.3) |

| 2 or more | 122 (38.6) | 147 (46.7) |

| Mean (SD) | ||

| Number of discharge medications | 10.5 (4.8) | 9.9 (5.1) |

| Index hospital length of stay, days | 3.9 (3.5) | 3.5 (3.5) |

| Pra | 0.486 (0.072) | 0.495 (0.076) |

We assessed the patient's perception of discharge preparedness. One week after discharge, research personnel interviewed 92.4% (292/316) of patients in the discharge software group and 92.4% (291/315) in the usual care group. The mean (SD) B‐PREPARED scores for discharge preparedness were 17.7 (4.1) in the discharge software group and 17.2 (4.0) in the usual care group. In the generalized estimating equation that accounted for potential clustering within hospital physicians, the parameter estimate for the intervention variable coefficient was small but significant (P = 0.042; Table 2). Patients in the discharge software group had slightly better perceptions of their discharge preparedness.

| Outcome Variable | Discharge Software [mean (SD)] | Usual Care [mean (SD)] | Parameter Estimate Without Cluster Correction (95% CI) | P Value | Parameter Estimate with Cluster Correction (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Patient perception of discharge preparedness (B‐PREPARED) | 17.7 (4.1) | 17.2 (4.0) | 0.147* (0.006‐0.288) | 0.040 | 0.147* (0.005‐0.289) | 0.042 |

| Patient satisfaction with medication information score (SIMS) | 12.3 (4.8) | 12.1 (4.6) | 0.212 (0.978‐0.554) | 0.587 | 0.212 (0.937‐0.513) | 0.567 |

| Outpatient physician perception (Modified Physician‐PREPARED) | 17.2 (3.8) | 16.5 (3.9) | 0.133 (0.012‐0.254) | 0.031 | 0.133 (0.015‐0.251) | 0.027 |

Another outcome was the patient's satisfaction with information about discharge medications (Table 2). One week after discharge, mean (SD) SIMS scores for satisfaction were 12.3 (4.8) in the discharge software group and 12.1 (4.6) in the usual care group. The generalized estimating equation revealed an insignificant coefficient for the intervention variable (P = 0.567; Table 2).

We assessed the outpatient physician perception of the discharge with a questionnaire sent 10 days after discharge. We received 496 out of 631 questionnaires (78.6%) from outpatient practitioners and the median response time was 19 days after the date of discharge. The practitioner specialty was internal medicine for 38.9% (193/496), family medicine for 27.2% (135/496), medicine‐pediatrics for 27.0% (134/496), advance practice nurse for 4.4% (22/496), other physician specialties for 2.0% (10/496), and physician assistant for 0.4% (2/496). We excluded 18 questionnaires from analysis because outpatient practitioners failed to answer 2 or more items in the Modified Physician‐PREPARED scale. When we compared baseline characteristics for patients who had complete questionnaires vs. patients with nonrespondent or excluded questionnaires, we found no significant differences (data available upon request). Among the discharge software group, 72.2% (228/316) of patients had complete questionnaires from their outpatient physicians. The response rate with complete questionnaires was 79.4% (250/315) of patients assigned to usual care. On the Modified Physician‐PREPARED scale, the mean (SD) scores were 17.2 (3.8) for the discharge software group and 16.5 (3.9) for the usual care group. The parameter estimate from the generalized estimating equation was significant (P = 0.027; Table 2). Outpatient physicians had slightly better perception of discharge quality for patients assigned to discharge software.

In the questionnaire sent to outpatient practitioners, we requested additional information about discharge communication. When asked about timeliness, outpatient physicians perceived no faster communication with the discharge software (Table 3). We asked about the media for discharge information exchange. It was uncommon for community physicians to receive discharge information via electronic mail (Table 3). Outpatient physicians acknowledged receipt of a minority of facsimile transmissions with no significant difference between discharge software vs. usual care (Table 3). Investigators documented facsimile transmission of the output from the discharge software to outpatient practitioners. Transmission occurred on the first business day after discharge. Despite the documentation of all facsimile transmissions, only 23.4% of patients assigned to discharge software had community practitioners who acknowledged receipt.

| Discharge Software (n = 316) [n (%)] | Usual Care (n = 315) [n (%)] | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Question: How soon after discharge did you receive any information (in any form) relating to this patient's hospital admission and discharge plans? | ||

| Within 1‐2 days | 72 (22.8) | 55 (17.5) |

| Within 1 week | 105 (33.2) | 125 (39.7) |

| Longer than 1 week | 36 (11.4) | 41 (13.0) |

| Not received | 20 (6.3) | 26 (8.3) |

| Other | 4 (1.3) | 7 (2.2) |

| Question: How did you receive discharge health status information? (Check all that apply)* | ||

| Written/typed letter | 106 (33.5) | 89 (28.3) |

| Telephone call | 82 (25.9) | 67 (21.3) |

| Fax (facsimile transmission) | 74 (23.4) | 90 (28.6) |

| Electronic mail | 8 (2.5) | 23 (7.3) |

| Other | 15 (4.7) | 15 (4.8) |

In exploratory analyses, we evaluated the effect of hospital physician level of training. We wondered if discharging physician experience or seniority affected perceptions of patients or primary care physicians. We entered level of training as a covariate in generalized estimating equations. When patient perception of discharge preparedness (B‐PREPARED) was the dependent variable, then physician level of training had a nonsignificant coefficient (P > 0.219). Likewise, physician level of training was nonsignificant in models of patient satisfaction with medication information, SIMS (P > 0.068), and outpatient physician perception, Modified Physician‐PREPARED (P > 0.177). We concluded that physician level of training had no influence on the patient‐level outcomes assessed in our study.

We compared the satisfaction of hospital physicians who used the discharge software and the usual care discharge. The proportions of hospital physicians who returned questionnaires were 85.7% (30/35) in the discharge software group and 97% (34/35) in the usual care group. After using their assigned discharge process for at least 6 months, discharge software users had mean (SD) satisfaction 7.4 (1.4) vs. 7.9 (1.4) for usual care physicians (difference = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.2‐1.3; P = 0.129). The effort for discharge software users was more difficult than the effort for usual care (mean [SD] effort = 6.5 [1.9] vs. 7.9 [2.1], respectively). The mean difference in effort was significant (difference = 1.4; 95% CI = 0.3‐2.4; P = 0.011). We reviewed free‐text comments on hospital physician questionnaires. The common theme was software users spent more time to complete discharges. We did not perform time‐motion assessments so we cannot confirm or refute these impressions. Even though hospital physicians found the discharge software significantly more difficult, they did not report a significant decrease in their satisfaction between the 2 discharge interventions.

The cluster design of our trial assumed variance in outcomes measured at the patient level. We predicted some variance attributable to clustering by hospital physician. After the trial, we calculated the intracluster correlation coefficients for B‐PREPARED, SIMS, and Modified Physician‐PREPARED. For all of these outcome variables, the intracluster correlation coefficients were negligible. We also evaluated generalized estimating equations with and without correction for hospital physician cluster. We confirmed the negligible cluster effect on CIs for intervention coefficients (Table 2).

We evaluated the adequacy of the blind for outcome assessors who interviewed patients for B‐PREPARED and SIMS. The guesses of outcomes assessors were unrelated to true intervention assignment (P = 0.253). We interpreted the blind as adequate.

Discussion

We performed a cluster‐randomized clinical trial to measure the effects of discharge software vs. usual care discharge. The discharge software incorporated the ASTM (American Society for Testing and Material) Continuity of Care Record (CCR) standards.19 The CCR is a patient health summary standard with widespread support from medical and specialty organizations. The rationale for the CCR was the need for continuity of care from 1 provider or practitioner to any other practitioner. Our discharge software had the same rationale as the CCR and included a subset of the clinical content specified by the CCR. Like the CCR, our discharge software produced concise reports, and emphasized a brief, postdischarge, care plan. Since we included clinical data elements recommended by the CCR, we hypothesized our discharge software would produce clinically relevant improvements.

Our discharge software also implemented elements of high‐quality discharge planning and communication endorsed by the Society of Hospital Medicine.20 For example, the discharge software produced a legible, typed, discharge plan for the patient or caregiver with medication instructions, follow‐up tests, studies, and appointments. The discharge software generated a discharge summary for the outpatient primary care physician and other clinicians who provided postdischarge care. The summary included discharge diagnoses, key findings and test results, follow‐up appointments, pending diagnostic tests, documentation of patient education, reconciled medication list, and contact information for the hospital physician. The discharge software compiled data for purposes of benchmarking, measurement, and continuous quality improvement. We thought our implementation of discharge software would lead to improved outcomes.

Despite our deployment of recommended strategies, we detected only small increases in patient perceptions of discharge preparedness. We do not know if small changes in B‐PREPARED values were clinically important. We found no improvement in patient satisfaction with medication information. Our results are consistent with systematic reviews that revealed limited benefit of interventions other than discharge planning with postdischarge support.21 Since our discharge software was added to robust discharge planning and support, we possibly had limited ability to detect benefit unless the intervention had a large effect size.

Our discharge software caused a small increase in positive perception reported by outpatient physicians. Small changes in the Modified Physician‐PREPARED had uncertain clinical relevance. Potential delays imposed by our distribution method may have contributed to our findings. Output from our discharge software went to community physicians via facsimile transmission with backup copies via standard U.S. mail. Our distribution system responded to several realities. Most community physicians in our area had no access to interoperable electronic medical records or secured e‐mail. In addition, electronic transmittal of prescriptions was not commonplace. Our discharge intervention did not control the flow of information inside the offices of outpatient physicians. We did not know if our facsimile transmissions joined piles of unread laboratory and imaging reports on the desks of busy primary care physicians. Despite the limited technology available to community physicians, they perceived communication generated by the software to be an improvement over the handwritten process. Our results support previous studies in which physicians preferred computer‐generated discharge summaries and summaries in standardized formats.2224

One of the limitations of our trial design was the unmasked intervention. Hospital physicians assigned to usual care might have improved their handwritten and verbal discharge communication after observation of their colleagues assigned to discharge software. This phenomenon is encountered in unmasked trials and is called contamination. We attempted to minimize contamination when we blocked usual care physicians from access to the discharge software. However, we could not eliminate cross‐talk among unmasked hospital physicians who worked together in close proximity during 27 months of patient enrollment. Some contamination was inevitable. When contamination occurred, there was bias toward the null (increased type II error).

Another limitation was the large proportion of hospital physicians in the first year of postgraduate training. There was a potential for variance from multilevel clusters with patient‐level outcomes clustered within first‐year hospital physicians who were clustered within teams supervised by senior resident or attending physicians. Our results argued against hierarchical clusters because intracluster correlation coefficients were negligible. Furthermore, our exploratory analysis suggested physician training level had no influence on patient outcomes measured in our study. We speculate the highly structured discharge process for both usual care and software minimized variance attributable to physician training level.

The research intervention in our trial was a stand‐alone software application. The discharge software did not integrate with the hospital electronic medical record. Consequently, hospital physician users had to reenter patient demographic data and prescription data that already existed in the electronic record. Data reentry probably caused hospital physicians to attribute greater effort to the discharge software.

In our study, hospital physicians incorporated discharge software with CPOE into their clinical workflow without deterioration in their satisfaction. Our experience may inform the decisions of hospital personnel who design health information systems. When designing discharge functions, developers should consider medication reconciliation and the standards of the CCR.19 Modules within the discharge software would likely be more efficient with prepopulated data from the electronic record. Then users could shift their work from data entry to data verification and possibly mitigate their perceived effort. Software developers may wish to explore options for data transmission to community physicians: secure e‐mail, automated fax servers, and direct digital file transfer. Future studies should test the acceptability of discharge functions incorporated within electronic health records with robust clinical decision support.

Our results apply to a population of adults of all ages with high risk for readmission. The results may not generalize to children, surgical patients, or people with low risk for readmission. All of the patients in our study were discharged to home. The exclusion of other discharge destinations helped us to enroll a homogenous cohort. However, the exclusion criteria did not allow us to generalize our results to patients discharged to nursing homes, inpatient rehabilitation units, or other acute care facilities. We designed the intervention to apply to the hospitalist model, in which responsibility for patient care transitions to a different physician after discharge. The results of our study do not apply when the inpatient and outpatient physician are the same. Since we enrolled general internal medicine hospital physicians, our results may not generalize to care provided by other specialists.

Conclusions

A discharge software application with CPOE improved perceptions of the hospital discharge process for patients and their outpatient physicians. When compared to the handwritten discharge process, the improvements were small in magnitude. Hospital physicians who used the discharge software reported more effort but otherwise no decrement in their satisfaction with the discharge process.

- ,,,,.The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- ,,,,,.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297:831–841.

- ,,,.Discharge planning from hospital to home.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2004;(1):CD000313.

- ,,.Dissemination of discharge summaries. Not reaching follow‐up physicians.Can Fam Physician.2002;48:737–742.

- ,,.Software design to facilitate information transfer at hospital discharge.Inform Prim Care.2006;14:109–119.

- ,.Computer physician order entry: benefits, costs, and issues.Ann Intern Med.2003;139:31–39.

- ,,, et al.Patient readmissions, emergency visits, and adverse events after software‐assisted discharge from hospital: cluster randomized trial.J Hosp Med.2009; DOI: 10.1002/jhm.459. PMID: 19479782.

- ,,.Predictive validity of a questionnaire that identifies older persons at risk for hospital admission.J Am Geriatr Soc.1995;43:374–377.

- ,.Prediction of early readmission in medical inpatients using the Probability of Repeated Admission instrument.Nurs Res.2008;57:406–415.

- ,.The ten point clock test: a quick screen and grading method for cognitive impairment in medical and surgical patients.Int J Psychiatry Med.1994;24:229–244.

- ,,, et al.Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge.Ann Intern Med.2005;143:121–128.

- ,,, et al.Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization.Arch Intern Med.2006;166:565–571.

- .SF‐36 health survey update.Spine.2000;25:3130–3139.

- ,.The development, validity and application of a new instrument to assess the quality of discharge planning activities from the community perspective.Int J Qual Health Care.2001;13:109–116.

- ,,.Brief scale measuring patient preparedness for hospital discharge to home: psychometric properties.J Hosp Med.2008;3:446–454.

- ,,.The Satisfaction with Information about Medicines Scale (SIMS): a new measurement tool for audit and research.Qual Health Care.2001;10:135–140.

- ,,.Discharge planning scale: community physicians' perspective.J Hosp Med.2008;3:455–464.

- ,.An introduction to generalized estimating equations and an application to assess selectivity effects in a longitudinal study on very old individuals.J Educ Behav Stat.2004;29:421–437. Available at: http://jeb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/29/4/421. Accessed June 2009.

- ASTM. E2369‐05 Standard Specification for Continuity of Care Record (CCR). Available at: http://www.astm.org/Standards/E2369.htm. Accessed June2009.

- ,,, et al.Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2006;1:354–360.

- ,,.Interventions aimed at reducing problems in adult patients discharged from hospital to home: a systematic meta‐review.BMC Health Serv Res.2007;7:47.

- ,,,,,.Evaluation of a computer‐generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes.Br J Gen Pract.1998;48:1163–1164.

- ,,,.Standardized or narrative discharge summaries. Which do family physicians prefer?Can Fam Physician.1998;44:62–69.

- ,,,.Dictated versus database‐generated discharge summaries: a randomized clinical trial.CMAJ.1999;160:319–326.

During the transition from inpatient to outpatient care, patients are vulnerable to adverse events.1 Poor communication between hospital personnel and either the patient or the outpatient primary care physician has been associated with preventable or ameliorable adverse events after discharge.1 Systematic reviews confirm that discharge communication is often delayed, inaccurate, or ineffective.2, 3

Discharge communication failures may occur if hospital processes rely on dictated discharge summaries.2 For several reasons, discharge summaries are inadequate for communication. Most patients complete their initial posthospital clinic visit before their primary care physician receives the discharge summary.4 For many patients, the discharge summary is unavailable for all posthospital visits.4 Discharge summaries often fail as communication because they are not generated or transmitted.4

Recommendations to improve discharge communication include the use of health information technology.2, 5 The benefits of computer‐generated discharge summaries include decreases in delivery time for discharge communications.2 The benefits of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) include reduction of medical errors.6 These theoretical benefits create a rationale for clinical trials to measure improvements after discharge software applications with CPOE.5

In an effort to improve discharge communication and clinically relevant outcomes, we performed a cluster‐randomized trial to assess the value of a discharge software application of CPOE. The clustered design followed recommendations from a systematic review of discharge interventions.3 We applied our research intervention at the physician level and measured outcomes at the patient level. Our objective was to assess the benefit of discharge software with CPOE vs. usual care when used to discharge patients at high risk for repeat admission. In a previous work, we reported that discharge software did not reduce rates of hospital readmission, emergency department visits, or postdischarge adverse events due to medical management.7 In the present article, we compare secondary outcomes after the research intervention: perceptions of the discharge from the perspectives of patients, primary care physicians, and hospital physicians.

Methods

The trial design was a cluster randomized, controlled trial. The setting was the postdischarge environment following index hospitalization at a 730‐bed, tertiary care, teaching hospital in central Illinois. The Peoria Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for human research.

Participants

We enrolled consenting hospital physicians and their patients between November 2004 and January 2007. The hospital physician defined the cluster. Patients discharged by the physician comprised the cluster. The eligibility criteria for hospital physicians required internal medicine resident or attending physicians with assignments to inpatient duties for at least 2 months during the 27‐month enrollment period. After achieving informed consent from physicians, research personnel screened all consecutive, adult inpatients who were discharged to home. Patient inclusion required a probability of repeat admission (Pra) equal to or greater than 0.40.8, 9 The purpose of the inclusion criterion was to enrich the sample with patients likely to benefit from interventions to improve discharge processes. Furthermore, hospital readmission was the primary endpoint of the study, as reported separately.7 The Pra came from a predictive model with scores for age, gender, prior hospitalizations, prior doctor visits, self‐rated health status, presence of informal caregiver in the home, and comorbid coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus. Research coordinators calculated the Pra within 2 days before discharge from the index hospitalization.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded patients previously enrolled in the study, candidates for hospice, and patients unable to participate in outcome ascertainment. Cognitive impairment was a conditional exclusion criterion for patients. We defined cognitive impairment as a score less than 9 on the 10‐point clock test.10 Patients with cognitive impairment participated only with consent from their legally authorized representative. We enrolled patients with cognitive impairment only if a proxy spent at least 3 hours daily with the patient and the proxy agreed to answer postdischarge interviews. If a patient's outpatient primary care physician treated the patient during the index hospitalization, then there was no perceived barrier in physician‐to‐physician communication and we excluded the patient.

Intervention

The research intervention was discharge software with CPOE. Detailed description of the software appeared previously.5 In summary, the CPOE software application facilitated communication at the time of hospital discharge to patients, retail pharmacists, and community physicians. The application had basic levels of clinical decision support, required fields, pick lists, standard drug doses, alerts, reminders, and online reference information. The software addressed deficiencies in the usual care discharge process reported globally and reviewed previously.5 For example, 1 deficiency occurred when inpatient physicians failed to warn outpatient physicians about diagnostic tests with results pending at discharge.11 Another deficiency was discharge medication error.12 The software prompted the discharging physician to enter pending tests, order tests after discharge, and perform medication reconciliation. On the day of discharge, hospital physicians used the software to automatically generate discharge documents and reconcile prescriptions for the patient, primary care physician, retail pharmacist, and the ward nurse. The discharge letter went to the outpatient practitioner via facsimile transmission plus a duplicate via U.S. mail.

The control intervention was the usual care, handwritten discharge process commonly used by hospitalists.2 Hospital physicians and ward nurses completed handwritten discharge forms on the day of discharge. The forms contained blanks for discharge diagnoses, discharge medications, medication instructions, postdischarge activities and restrictions, postdischarge diet, postdischarge diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and appointments. Patients received handwritten copies of the forms, 1 page of which also included medication instructions and prescriptions. In a previous publication, we provided details about the usual care discharge process as well as the standard care available to all study patients regardless of intervention.5

Randomization

The hospital physician who completed the discharge process was the unit of randomization. Random allocation was to discharge software or usual care discharge process, with a randomization ratio of 1:1 and block size of 2. We concealed allocation with the following process. An investigator who was not involved with hospital physician recruitment generated the randomization sequence with a computerized random number generator. The randomization list was maintained in a secure location. Another investigator who was unaware of the next random assignment performed the hospital physician recruitment and informed consent. After confirming eligibility and obtaining informed consent from physicians, the blinded investigator requested the next random assignment from the custodian of the randomization list. Hospital physicians subsequently used their randomly assigned process when discharging their patients who enrolled in the study. After random allocation, it was not possible to conceal the test or control intervention from physicians or their patients.

Hospital physicians underwent training on the software or usual care discharge process; the details appeared previously.7 Physicians assigned to usual care did not receive training on the discharge software and were blocked from using the software. Patients were passive recipients of the research intervention performed by their discharging physician. Patients received the research intervention on the day of discharge of the index hospitalization.

Baseline Assessment

During the index hospitalization, trained data abstractors recorded baseline patient demographic data plus variables to calculate the Pra for probability for repeat admission. We recorded the availability of an informal caregiver in response to the question, Is there a friend, relative, or neighbor who would take care of you for a few days, if necessary? Data came from the patient or proxy for physical functioning, mental health,13 heart failure, and number of previous emergency department visits. Other data came from hospital records for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, number of discharge medications, and length of stay for the index hospitalization.

Outcome Assessment

We assessed the patient's perception of the discharge with 2 validated survey instruments. One week after discharge, research personnel performed telephone interviews with patients or proxies. While following a script, interviewers instructed patients to avoid mentioning the discharge process. Interviewers read items from the B‐PREPARED questionnaire.14, 15 and the Satisfaction with Information About Medicines Scale (SIMS).16 The B‐PREPARED scale assessed 3 principal components of patient preparedness for discharge: self‐care information for medications and activities, equipment and services, and confidence. The scale demonstrated internal consistency, construct validity, and predictive validity. High scale values reflected high perceptions of discharge preparedness from the patient perspective.15 SIMS measured patient satisfaction with information about discharge medications. Validation studies revealed SIMS had internal consistency, test‐retest reliability, and criterion‐related validity.16 Interviewers recorded responses to calculate a total SIMS score. Patients with high total SIMS scores had high satisfaction. While assessing B‐PREPARED and SIMS, interviewers were blind to intervention assignment. We evaluated the adequacy of blinding by asking interviewers to guess the patient's intervention assignment.

We measured the quality of hospital discharge from the outpatient physician perspective. During the index hospitalization, patients designated an outpatient primary care practitioner to receive discharge reports and results of diagnostic tests. Ten days after discharge, research personnel mailed the Physician‐PREPARED questionnaire to the designated community practitioner.17 The sum of item responses comprised the Modified Physician‐PREPARED scale and demonstrated internal consistency and construct validity. The principal components of the Modified Physician‐PREPARED were timeliness of communication and adequacy of discharge plan/transmission. High scale values reflected high perceptions of discharge quality.17 Outpatient practitioners gave implied consent when they completed and returned questionnaires. We requested 1 questionnaire for each enrolled patient, so the outcome assessment was at the patient level. The assessment was not blinded because primary care physicians received the output of discharge software or usual care discharge.

We assessed the satisfaction of hospital physicians who used the discharge software and the usual care. After hospital physicians participated in the trial for 6 months, they rated their assigned discharge process on Likert scales. The first question was, On a scale of 1 to 10, indicate your satisfaction with your portion of the discharge process. The scale anchors were 1 for very dissatisfied and 10 for very satisfied. The second question was, On a scale of 1 to 10, indicate the effort to complete your portion of the discharge process. For the second question, the scale anchors were 1 for very difficult and 10 for very easy. It was not possible to mask the hospital physicians after they received their intervention assignment. Consequently, their outcome assessment was not blinded.

Statistical Methods

The cluster number and size were selected to maintain test significance level, 1‐sided alpha less than 0.05, and power greater than 80%. We previously published the assumptions and rationale for 35 hospital physician clusters per intervention and 9 patients per cluster.7 We did not perform separate sample size estimates for the secondary outcomes reported herein.

The statistical analyses employed SPSS PC (Version 15.0.1; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical procedures for baseline variables were descriptive and included means and standard deviations (SDs) for interval variables and percentages for categorical variables. For all analyses, we employed the principle of intention‐to‐treat. We assumed patient or physician exposure to the intervention randomly assigned to the discharging physician. Analyses employed standard tests for normal distribution, homogeneity of variance, and linearity of relationships between independent and dependent variables. If assumptions failed, then we stratified variables or performed transformations. We accepted P < 0.05 as significant.

We tested hypotheses for patient‐level outcomes with generalized estimating equations (GEEs) that corrected for clustering by hospital physician. We employed GEEs because they provide unbiased estimates of standard errors for parameters even with incorrect specification of the intracluster dependence structure.18 Each patient‐level outcome was the dependent variable in a separate GEE. The intervention variable for each GEE was discharge software vs. usual care, handwritten discharge. The statistic of interest was the coefficient for the intervention variable. The null hypothesis was no difference between discharge software and usual care. The statistical definition of the null hypothesis was an intervention variable coefficient with a 95% confidence interval (CI) that included 0.

For analyses that were unaffected by the cluster assumption, we performed standard tests. The hypothesis for hospital physicians was significantly higher satisfaction for discharge software users and the inferential procedure was the t test. When we assessed the success of the study blinding, we assumed no association between true intervention allocation and guesses by outcome assessors. We used chi‐square for assessment of the blinding.

Results

We screened 127 physicians who were general internal medicine hospital physicians. Seventy physicians consented and received random allocation to discharge software or usual care. We excluded 57 physicians for reasons shown in the trial flow diagram (Figure 1). We approached 6884 patients during their index hospitalization. After excluding 6253 ineligible patients, we enrolled 631 willing patients (Supplementary Appendix). As depicted in Figure 1, the most common reason for ineligibility occurred for patients with Pra score <0.40 (2168/6253 exclusions; 34.7%). We followed 631 patients who received the discharge intervention (Figure 1). There was no differential dropout between the interventions. Protocol deviations were rare, 0.5% (3/631). Three patients erroneously received usual care discharge from physicians assigned to discharge software. All 631 patients were included in the intention‐to‐treat analysis. The baseline characteristics of the randomly assigned hospital physicians and their patients are in Table 1. Most of the hospital physicians were residents in the first year of postgraduate training.

| Discharge Software | Usual Care | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Hospital physician characteristics, n (%) | n = 35 | n = 35 |

| Postgraduate year 1 | 18 (51.4) | 23 (65.7) |

| Postgraduate years 2‐4 | 10 (28.6) | 7 (20.0) |

| Attending physician | 7 (20.0) | 5 (14.3) |

| Patient characteristics, n (%) | n = 316 | n = 315 |

| Gender, male | 136 (43.0) | 147 (46.7) |

| Age, years | ||

| 18‐44 | 68 (21.5) | 95 (30.2) |

| 45‐54 | 79 (25.0) | 76 (24.1) |

| 55‐64 | 86 (27.2) | 74 (23.5) |

| 65‐98 | 83 (26.3) | 70 (22.2) |

| Self‐rated health status | ||

| Poor | 82 (25.9) | 108 (34.3) |

| Fair | 169 (53.5) | 147 (46.7) |

| Good | 54 (17.1) | 46 (14.6) |

| Very good | 10 (3.2) | 11 (3.5) |

| Excellent | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 172 (54.4) | 177 (56.2) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||

| None | 259 (82.0) | 257 (81.6) |

| Without oral steroid or home oxygen | 28 (8.9) | 26 (8.3) |

| With chronic oral steroid | 10 (3.2) | 8 (2.5) |

| With home oxygen oral steroid | 19 (6.0) | 24 (7.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 133 (42.1) | 120 (38.1) |

| Heart failure | 80 (25.3) | 67 (21.3) |

| Physical Functioning from SF‐36 | ||

| Lowest third | 128 (40.5) | 121 (38.4) |

| Upper two‐thirds | 188 (59.5) | 194 (61.6) |

| Mental Health from SF‐36 | ||

| Lowest one‐third | 113 (35.8) | 117 (37.1)* |

| Upper two‐thirds | 203 (64.2) | 197 (62.5)* |

| Emergency department visits during 6 months before index admission | ||

| 0 or 1 | 194 (61.4) | 168 (53.3) |

| 2 or more | 122 (38.6) | 147 (46.7) |

| Mean (SD) | ||

| Number of discharge medications | 10.5 (4.8) | 9.9 (5.1) |

| Index hospital length of stay, days | 3.9 (3.5) | 3.5 (3.5) |

| Pra | 0.486 (0.072) | 0.495 (0.076) |

We assessed the patient's perception of discharge preparedness. One week after discharge, research personnel interviewed 92.4% (292/316) of patients in the discharge software group and 92.4% (291/315) in the usual care group. The mean (SD) B‐PREPARED scores for discharge preparedness were 17.7 (4.1) in the discharge software group and 17.2 (4.0) in the usual care group. In the generalized estimating equation that accounted for potential clustering within hospital physicians, the parameter estimate for the intervention variable coefficient was small but significant (P = 0.042; Table 2). Patients in the discharge software group had slightly better perceptions of their discharge preparedness.

| Outcome Variable | Discharge Software [mean (SD)] | Usual Care [mean (SD)] | Parameter Estimate Without Cluster Correction (95% CI) | P Value | Parameter Estimate with Cluster Correction (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Patient perception of discharge preparedness (B‐PREPARED) | 17.7 (4.1) | 17.2 (4.0) | 0.147* (0.006‐0.288) | 0.040 | 0.147* (0.005‐0.289) | 0.042 |

| Patient satisfaction with medication information score (SIMS) | 12.3 (4.8) | 12.1 (4.6) | 0.212 (0.978‐0.554) | 0.587 | 0.212 (0.937‐0.513) | 0.567 |

| Outpatient physician perception (Modified Physician‐PREPARED) | 17.2 (3.8) | 16.5 (3.9) | 0.133 (0.012‐0.254) | 0.031 | 0.133 (0.015‐0.251) | 0.027 |

Another outcome was the patient's satisfaction with information about discharge medications (Table 2). One week after discharge, mean (SD) SIMS scores for satisfaction were 12.3 (4.8) in the discharge software group and 12.1 (4.6) in the usual care group. The generalized estimating equation revealed an insignificant coefficient for the intervention variable (P = 0.567; Table 2).

We assessed the outpatient physician perception of the discharge with a questionnaire sent 10 days after discharge. We received 496 out of 631 questionnaires (78.6%) from outpatient practitioners and the median response time was 19 days after the date of discharge. The practitioner specialty was internal medicine for 38.9% (193/496), family medicine for 27.2% (135/496), medicine‐pediatrics for 27.0% (134/496), advance practice nurse for 4.4% (22/496), other physician specialties for 2.0% (10/496), and physician assistant for 0.4% (2/496). We excluded 18 questionnaires from analysis because outpatient practitioners failed to answer 2 or more items in the Modified Physician‐PREPARED scale. When we compared baseline characteristics for patients who had complete questionnaires vs. patients with nonrespondent or excluded questionnaires, we found no significant differences (data available upon request). Among the discharge software group, 72.2% (228/316) of patients had complete questionnaires from their outpatient physicians. The response rate with complete questionnaires was 79.4% (250/315) of patients assigned to usual care. On the Modified Physician‐PREPARED scale, the mean (SD) scores were 17.2 (3.8) for the discharge software group and 16.5 (3.9) for the usual care group. The parameter estimate from the generalized estimating equation was significant (P = 0.027; Table 2). Outpatient physicians had slightly better perception of discharge quality for patients assigned to discharge software.

In the questionnaire sent to outpatient practitioners, we requested additional information about discharge communication. When asked about timeliness, outpatient physicians perceived no faster communication with the discharge software (Table 3). We asked about the media for discharge information exchange. It was uncommon for community physicians to receive discharge information via electronic mail (Table 3). Outpatient physicians acknowledged receipt of a minority of facsimile transmissions with no significant difference between discharge software vs. usual care (Table 3). Investigators documented facsimile transmission of the output from the discharge software to outpatient practitioners. Transmission occurred on the first business day after discharge. Despite the documentation of all facsimile transmissions, only 23.4% of patients assigned to discharge software had community practitioners who acknowledged receipt.

| Discharge Software (n = 316) [n (%)] | Usual Care (n = 315) [n (%)] | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Question: How soon after discharge did you receive any information (in any form) relating to this patient's hospital admission and discharge plans? | ||

| Within 1‐2 days | 72 (22.8) | 55 (17.5) |

| Within 1 week | 105 (33.2) | 125 (39.7) |

| Longer than 1 week | 36 (11.4) | 41 (13.0) |

| Not received | 20 (6.3) | 26 (8.3) |

| Other | 4 (1.3) | 7 (2.2) |

| Question: How did you receive discharge health status information? (Check all that apply)* | ||

| Written/typed letter | 106 (33.5) | 89 (28.3) |

| Telephone call | 82 (25.9) | 67 (21.3) |

| Fax (facsimile transmission) | 74 (23.4) | 90 (28.6) |

| Electronic mail | 8 (2.5) | 23 (7.3) |

| Other | 15 (4.7) | 15 (4.8) |

In exploratory analyses, we evaluated the effect of hospital physician level of training. We wondered if discharging physician experience or seniority affected perceptions of patients or primary care physicians. We entered level of training as a covariate in generalized estimating equations. When patient perception of discharge preparedness (B‐PREPARED) was the dependent variable, then physician level of training had a nonsignificant coefficient (P > 0.219). Likewise, physician level of training was nonsignificant in models of patient satisfaction with medication information, SIMS (P > 0.068), and outpatient physician perception, Modified Physician‐PREPARED (P > 0.177). We concluded that physician level of training had no influence on the patient‐level outcomes assessed in our study.

We compared the satisfaction of hospital physicians who used the discharge software and the usual care discharge. The proportions of hospital physicians who returned questionnaires were 85.7% (30/35) in the discharge software group and 97% (34/35) in the usual care group. After using their assigned discharge process for at least 6 months, discharge software users had mean (SD) satisfaction 7.4 (1.4) vs. 7.9 (1.4) for usual care physicians (difference = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.2‐1.3; P = 0.129). The effort for discharge software users was more difficult than the effort for usual care (mean [SD] effort = 6.5 [1.9] vs. 7.9 [2.1], respectively). The mean difference in effort was significant (difference = 1.4; 95% CI = 0.3‐2.4; P = 0.011). We reviewed free‐text comments on hospital physician questionnaires. The common theme was software users spent more time to complete discharges. We did not perform time‐motion assessments so we cannot confirm or refute these impressions. Even though hospital physicians found the discharge software significantly more difficult, they did not report a significant decrease in their satisfaction between the 2 discharge interventions.

The cluster design of our trial assumed variance in outcomes measured at the patient level. We predicted some variance attributable to clustering by hospital physician. After the trial, we calculated the intracluster correlation coefficients for B‐PREPARED, SIMS, and Modified Physician‐PREPARED. For all of these outcome variables, the intracluster correlation coefficients were negligible. We also evaluated generalized estimating equations with and without correction for hospital physician cluster. We confirmed the negligible cluster effect on CIs for intervention coefficients (Table 2).

We evaluated the adequacy of the blind for outcome assessors who interviewed patients for B‐PREPARED and SIMS. The guesses of outcomes assessors were unrelated to true intervention assignment (P = 0.253). We interpreted the blind as adequate.

Discussion

We performed a cluster‐randomized clinical trial to measure the effects of discharge software vs. usual care discharge. The discharge software incorporated the ASTM (American Society for Testing and Material) Continuity of Care Record (CCR) standards.19 The CCR is a patient health summary standard with widespread support from medical and specialty organizations. The rationale for the CCR was the need for continuity of care from 1 provider or practitioner to any other practitioner. Our discharge software had the same rationale as the CCR and included a subset of the clinical content specified by the CCR. Like the CCR, our discharge software produced concise reports, and emphasized a brief, postdischarge, care plan. Since we included clinical data elements recommended by the CCR, we hypothesized our discharge software would produce clinically relevant improvements.

Our discharge software also implemented elements of high‐quality discharge planning and communication endorsed by the Society of Hospital Medicine.20 For example, the discharge software produced a legible, typed, discharge plan for the patient or caregiver with medication instructions, follow‐up tests, studies, and appointments. The discharge software generated a discharge summary for the outpatient primary care physician and other clinicians who provided postdischarge care. The summary included discharge diagnoses, key findings and test results, follow‐up appointments, pending diagnostic tests, documentation of patient education, reconciled medication list, and contact information for the hospital physician. The discharge software compiled data for purposes of benchmarking, measurement, and continuous quality improvement. We thought our implementation of discharge software would lead to improved outcomes.

Despite our deployment of recommended strategies, we detected only small increases in patient perceptions of discharge preparedness. We do not know if small changes in B‐PREPARED values were clinically important. We found no improvement in patient satisfaction with medication information. Our results are consistent with systematic reviews that revealed limited benefit of interventions other than discharge planning with postdischarge support.21 Since our discharge software was added to robust discharge planning and support, we possibly had limited ability to detect benefit unless the intervention had a large effect size.

Our discharge software caused a small increase in positive perception reported by outpatient physicians. Small changes in the Modified Physician‐PREPARED had uncertain clinical relevance. Potential delays imposed by our distribution method may have contributed to our findings. Output from our discharge software went to community physicians via facsimile transmission with backup copies via standard U.S. mail. Our distribution system responded to several realities. Most community physicians in our area had no access to interoperable electronic medical records or secured e‐mail. In addition, electronic transmittal of prescriptions was not commonplace. Our discharge intervention did not control the flow of information inside the offices of outpatient physicians. We did not know if our facsimile transmissions joined piles of unread laboratory and imaging reports on the desks of busy primary care physicians. Despite the limited technology available to community physicians, they perceived communication generated by the software to be an improvement over the handwritten process. Our results support previous studies in which physicians preferred computer‐generated discharge summaries and summaries in standardized formats.2224

One of the limitations of our trial design was the unmasked intervention. Hospital physicians assigned to usual care might have improved their handwritten and verbal discharge communication after observation of their colleagues assigned to discharge software. This phenomenon is encountered in unmasked trials and is called contamination. We attempted to minimize contamination when we blocked usual care physicians from access to the discharge software. However, we could not eliminate cross‐talk among unmasked hospital physicians who worked together in close proximity during 27 months of patient enrollment. Some contamination was inevitable. When contamination occurred, there was bias toward the null (increased type II error).

Another limitation was the large proportion of hospital physicians in the first year of postgraduate training. There was a potential for variance from multilevel clusters with patient‐level outcomes clustered within first‐year hospital physicians who were clustered within teams supervised by senior resident or attending physicians. Our results argued against hierarchical clusters because intracluster correlation coefficients were negligible. Furthermore, our exploratory analysis suggested physician training level had no influence on patient outcomes measured in our study. We speculate the highly structured discharge process for both usual care and software minimized variance attributable to physician training level.

The research intervention in our trial was a stand‐alone software application. The discharge software did not integrate with the hospital electronic medical record. Consequently, hospital physician users had to reenter patient demographic data and prescription data that already existed in the electronic record. Data reentry probably caused hospital physicians to attribute greater effort to the discharge software.

In our study, hospital physicians incorporated discharge software with CPOE into their clinical workflow without deterioration in their satisfaction. Our experience may inform the decisions of hospital personnel who design health information systems. When designing discharge functions, developers should consider medication reconciliation and the standards of the CCR.19 Modules within the discharge software would likely be more efficient with prepopulated data from the electronic record. Then users could shift their work from data entry to data verification and possibly mitigate their perceived effort. Software developers may wish to explore options for data transmission to community physicians: secure e‐mail, automated fax servers, and direct digital file transfer. Future studies should test the acceptability of discharge functions incorporated within electronic health records with robust clinical decision support.

Our results apply to a population of adults of all ages with high risk for readmission. The results may not generalize to children, surgical patients, or people with low risk for readmission. All of the patients in our study were discharged to home. The exclusion of other discharge destinations helped us to enroll a homogenous cohort. However, the exclusion criteria did not allow us to generalize our results to patients discharged to nursing homes, inpatient rehabilitation units, or other acute care facilities. We designed the intervention to apply to the hospitalist model, in which responsibility for patient care transitions to a different physician after discharge. The results of our study do not apply when the inpatient and outpatient physician are the same. Since we enrolled general internal medicine hospital physicians, our results may not generalize to care provided by other specialists.

Conclusions

A discharge software application with CPOE improved perceptions of the hospital discharge process for patients and their outpatient physicians. When compared to the handwritten discharge process, the improvements were small in magnitude. Hospital physicians who used the discharge software reported more effort but otherwise no decrement in their satisfaction with the discharge process.

During the transition from inpatient to outpatient care, patients are vulnerable to adverse events.1 Poor communication between hospital personnel and either the patient or the outpatient primary care physician has been associated with preventable or ameliorable adverse events after discharge.1 Systematic reviews confirm that discharge communication is often delayed, inaccurate, or ineffective.2, 3

Discharge communication failures may occur if hospital processes rely on dictated discharge summaries.2 For several reasons, discharge summaries are inadequate for communication. Most patients complete their initial posthospital clinic visit before their primary care physician receives the discharge summary.4 For many patients, the discharge summary is unavailable for all posthospital visits.4 Discharge summaries often fail as communication because they are not generated or transmitted.4

Recommendations to improve discharge communication include the use of health information technology.2, 5 The benefits of computer‐generated discharge summaries include decreases in delivery time for discharge communications.2 The benefits of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) include reduction of medical errors.6 These theoretical benefits create a rationale for clinical trials to measure improvements after discharge software applications with CPOE.5

In an effort to improve discharge communication and clinically relevant outcomes, we performed a cluster‐randomized trial to assess the value of a discharge software application of CPOE. The clustered design followed recommendations from a systematic review of discharge interventions.3 We applied our research intervention at the physician level and measured outcomes at the patient level. Our objective was to assess the benefit of discharge software with CPOE vs. usual care when used to discharge patients at high risk for repeat admission. In a previous work, we reported that discharge software did not reduce rates of hospital readmission, emergency department visits, or postdischarge adverse events due to medical management.7 In the present article, we compare secondary outcomes after the research intervention: perceptions of the discharge from the perspectives of patients, primary care physicians, and hospital physicians.

Methods

The trial design was a cluster randomized, controlled trial. The setting was the postdischarge environment following index hospitalization at a 730‐bed, tertiary care, teaching hospital in central Illinois. The Peoria Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for human research.

Participants

We enrolled consenting hospital physicians and their patients between November 2004 and January 2007. The hospital physician defined the cluster. Patients discharged by the physician comprised the cluster. The eligibility criteria for hospital physicians required internal medicine resident or attending physicians with assignments to inpatient duties for at least 2 months during the 27‐month enrollment period. After achieving informed consent from physicians, research personnel screened all consecutive, adult inpatients who were discharged to home. Patient inclusion required a probability of repeat admission (Pra) equal to or greater than 0.40.8, 9 The purpose of the inclusion criterion was to enrich the sample with patients likely to benefit from interventions to improve discharge processes. Furthermore, hospital readmission was the primary endpoint of the study, as reported separately.7 The Pra came from a predictive model with scores for age, gender, prior hospitalizations, prior doctor visits, self‐rated health status, presence of informal caregiver in the home, and comorbid coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus. Research coordinators calculated the Pra within 2 days before discharge from the index hospitalization.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded patients previously enrolled in the study, candidates for hospice, and patients unable to participate in outcome ascertainment. Cognitive impairment was a conditional exclusion criterion for patients. We defined cognitive impairment as a score less than 9 on the 10‐point clock test.10 Patients with cognitive impairment participated only with consent from their legally authorized representative. We enrolled patients with cognitive impairment only if a proxy spent at least 3 hours daily with the patient and the proxy agreed to answer postdischarge interviews. If a patient's outpatient primary care physician treated the patient during the index hospitalization, then there was no perceived barrier in physician‐to‐physician communication and we excluded the patient.

Intervention

The research intervention was discharge software with CPOE. Detailed description of the software appeared previously.5 In summary, the CPOE software application facilitated communication at the time of hospital discharge to patients, retail pharmacists, and community physicians. The application had basic levels of clinical decision support, required fields, pick lists, standard drug doses, alerts, reminders, and online reference information. The software addressed deficiencies in the usual care discharge process reported globally and reviewed previously.5 For example, 1 deficiency occurred when inpatient physicians failed to warn outpatient physicians about diagnostic tests with results pending at discharge.11 Another deficiency was discharge medication error.12 The software prompted the discharging physician to enter pending tests, order tests after discharge, and perform medication reconciliation. On the day of discharge, hospital physicians used the software to automatically generate discharge documents and reconcile prescriptions for the patient, primary care physician, retail pharmacist, and the ward nurse. The discharge letter went to the outpatient practitioner via facsimile transmission plus a duplicate via U.S. mail.

The control intervention was the usual care, handwritten discharge process commonly used by hospitalists.2 Hospital physicians and ward nurses completed handwritten discharge forms on the day of discharge. The forms contained blanks for discharge diagnoses, discharge medications, medication instructions, postdischarge activities and restrictions, postdischarge diet, postdischarge diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and appointments. Patients received handwritten copies of the forms, 1 page of which also included medication instructions and prescriptions. In a previous publication, we provided details about the usual care discharge process as well as the standard care available to all study patients regardless of intervention.5

Randomization

The hospital physician who completed the discharge process was the unit of randomization. Random allocation was to discharge software or usual care discharge process, with a randomization ratio of 1:1 and block size of 2. We concealed allocation with the following process. An investigator who was not involved with hospital physician recruitment generated the randomization sequence with a computerized random number generator. The randomization list was maintained in a secure location. Another investigator who was unaware of the next random assignment performed the hospital physician recruitment and informed consent. After confirming eligibility and obtaining informed consent from physicians, the blinded investigator requested the next random assignment from the custodian of the randomization list. Hospital physicians subsequently used their randomly assigned process when discharging their patients who enrolled in the study. After random allocation, it was not possible to conceal the test or control intervention from physicians or their patients.

Hospital physicians underwent training on the software or usual care discharge process; the details appeared previously.7 Physicians assigned to usual care did not receive training on the discharge software and were blocked from using the software. Patients were passive recipients of the research intervention performed by their discharging physician. Patients received the research intervention on the day of discharge of the index hospitalization.

Baseline Assessment

During the index hospitalization, trained data abstractors recorded baseline patient demographic data plus variables to calculate the Pra for probability for repeat admission. We recorded the availability of an informal caregiver in response to the question, Is there a friend, relative, or neighbor who would take care of you for a few days, if necessary? Data came from the patient or proxy for physical functioning, mental health,13 heart failure, and number of previous emergency department visits. Other data came from hospital records for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, number of discharge medications, and length of stay for the index hospitalization.

Outcome Assessment