User login

Afraid in the Hospital

The Institute of Medicine report linking between 48,000 and 98,000 deaths annually to medical errors1 has raised awareness about medical errors across all areas of medicine. In pediatrics, medical errors in hospitalized children are associated with significant increases in length of stay, healthcare costs, and death.2, 3 While much attention has been paid to the use of hospital systems to prevent medical errors, there has been considerably less focus on the experiences of patients and their potential role in preventing errors.

Studies have suggested that a significant majority of adult patients are concerned about medical errors during hospitalization.4, 5 However, a similar assessment of parents' concerns about medical errors in pediatrics is lacking. Admittedly, for concern to be constructive it must be linked to action. The Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) currently recommend that parents help prevent errors by becoming active, involved and informed members of their healthcare team and taking part in every decision about (their) child's health care.6, 7 However, the extent to which parental concern about medical errors is related to a parent's self‐efficacy, or confidence, interacting with physicians is unknown.

Self‐efficacy is a construct used in social cognitive theory to explain behavior change.8 It refers to an individual's belief in (his/her) capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments or a desired outcome.9 Self‐efficacy is not a general concept; it must be discussed in reference to a specific activity. In healthcare it has been associated not only with willingness to adopt preventive strategies,10 but also with treatment adherence,11, 12 behavior change,13 and with greater patient participation in healthcare decision‐making.14, 15

In this study we had 2 objectives. First, we sought to assess the proportion of parents of hospitalized children who are concerned about medical errors. Second, we attempted to examine whether a parent's self‐efficacy interacting with physicians was associated with their concern about medical errors for their child. Given that parents with greater self‐efficacy interacting with physicians might feel more empowered to prevent errors and, as such, be more inclined to take an active role to do so, we hypothesized that such parents would be less concerned about medical errors during a pediatric hospitalization.

Subjects and Methods

Population

We surveyed parents of children <18 years of age (including 2 grandparents who will hereafter be referred to as parents) who were admitted to the general medical service of the Children's Hospital & Regional Medical Center (CHRMC) in Seattle, WA, from July through September 2005. This study was approved by the CHRMC Institutional Review Board. Due to stipulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), we were unable to collect extensive information on those parents who were missed or those who refused to participate in the study.

Exclusions

We excluded parents if: (1) they did not feel comfortable answering a written survey in English or Spanish; (2) their child was transferred to the general medical unit either from the intensive care unit (ICU) or from the inpatient unit of another hospital; or (3) they were not present during the hospitalization.

Study Design

We conducted a cross‐sectional self‐administered written survey of parents. The survey was translated into Spanish by a certified Spanish translator. A second independent translator confirmed the accuracy of the translation. Informed consent was obtained from parents before administration of the survey.

Data Collection

Parents were surveyed with a consecutive sampling methodology Tuesday through Friday from July 2005 through September 2005. We surveyed parents within 48 hours of admission of their child to the hospital, but after they had an opportunity to speak with the inpatient medical team that was caring for their child. A more detailed discussion of the data collection process has been published previously.16

Dependent Variables

Parental Concern About the Need to Watch for Medical Errors

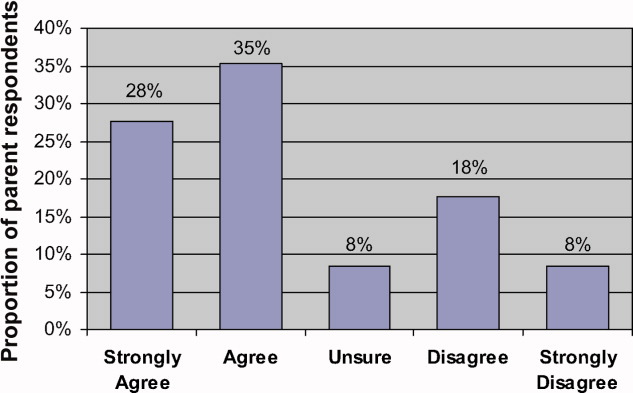

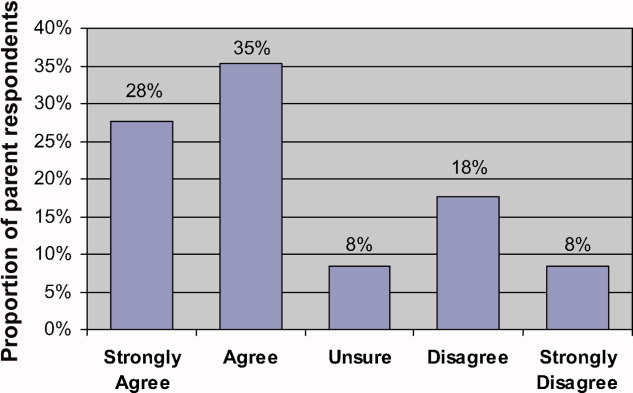

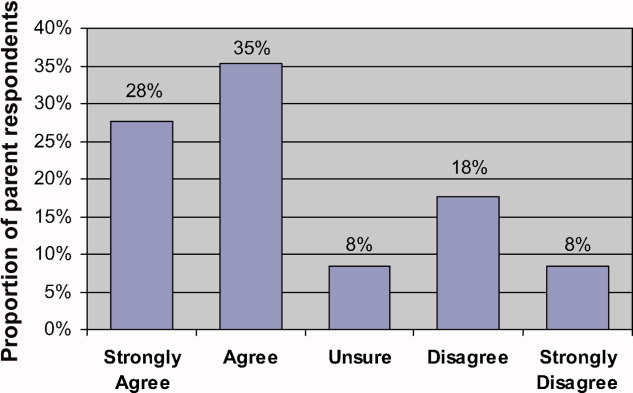

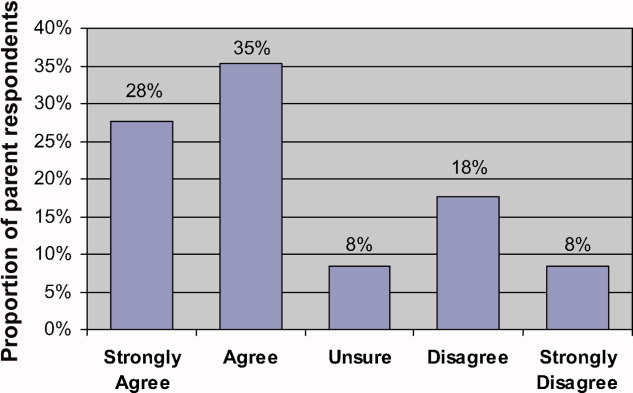

We assessed parental concerns about medical errors during hospitalization by measuring responses to the statement When my child is in the hospital I feel that I have to watch over the care that he/she is receiving to make sure that mistakes aren't made. Parents reported their agreement/disagreement with this statement using a 5‐point Likert scale. For our analysis we dichotomized the dependent variable into those parents who responded Strongly Agree or Agree vs. those who responded Strongly Disagree or Disagree. We chose to focus on parents who expressed a directional response (eg, agree or disagree) because we felt that such responses were more likely to be correlated with behavior. As a result, we excluded from our primary analysis those participants who responded Unsure. In order to determine the effect of exclusion on our results (given its size), we conducted separate post‐hoc analyses in which we included the Unsure respondents in Agree and Disagree categories, respectively.

Independent Variables

Self‐Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions

The Joint Commission's Speak Up initiative7 recommends that patients and parents interact with their healthcare providers in order to prevent errors. We gauged a parent's confidence of interacting with healthcare providers using an adapted scale of the Perceived Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions (PEPPI) self‐efficacy scale. The PEPPI is a 50‐point self‐efficacy scale that has been validated in older adults.17 The response to each question is recorded on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 where 1 represents not at all confident and 5 represents very confident. Higher scores on this scale have been associated with greater participation in treatment decisions by women with breast cancer.18 We adapted this scale for use in pediatrics (Appendix 1).

Covariates

Prior Hospitalizations and Chronic Illness History

We asked parents to report how many times their child had been hospitalized prior to this current admission (not including birth). We chose to query parents directly because a search of our institutions' medical record database would not capture hospitalizations at other facilities. We categorized the variable for previous hospitalizations as follows: none, 1, 2, 3.

We asked parents to report if prior to this hospitalization they had ever been told by a nurse or doctor that their child had any of a list of chronic medical conditions such as chronic respiratory disease, mental retardation, and seizure disorder, among others. We gave parents the opportunity to specify a medical condition not provided on this list. The list of conditions was the same as that used in the Child Health Questionnaire PF‐28,19 which has been used in national and international studies to measure quality of life in children with and without chronic conditions20, 21 (Appendix 2).

Limited English Proficiency

We assessed the potential for a language barrier to impede communication between parent and healthcare providers by asking parents the following question: How comfortable are you that you can express your concerns and ask questions of your child's doctors in English? We measured parental responses on a 5‐point Likert scale (very comfortable vs. somewhat comfortable, not sure, somewhat uncomfortable, very uncomfortable). For our analyses, we dichotomized responses into those who reported being very comfortable vs. those who chose any other response category.

Social Desirability

We measured the potential for social desirability to bias responses using the Marlowe‐Crowne 2(10) Scale of Social Desirability.22 The Marlowe‐Crowne 2(10) Scale of Social Desirability is a shorter, validated version of the Marlowe‐Crowne Scale.23 This scale has been recommended by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)'s Behavior Change Consortium for use in behavioral change research related to health.24 It has been used in previous studies to account for social desirability bias in studies which involve patient self‐report of attitudes and beliefs.25 We analyzed scores on a continuous scale with higher scores representing greater social desirability bias in responses.

Demographics

We collected the following demographic data on parents: age, gender, race/ethnicity (white non‐Hispanic vs. other), education (high school or less, some college, college or higher). We also recorded the child's age and gender.

Statistical Analysis

Parental Concern for Medical Errors

Univariate statistics were used to report proportions of parents who were concerned about medical errors and to summarize the data for covariates and demographics. We conducted bivariate logistic regression analyses to assess the association between our outcome variable and the independent variable and each covariate, respectively. We used a Fisher's exact test to examine the association between limited English proficiency and our outcome variable because the absence of participants (eg, a zero cell) who were not very comfortable with English and not concerned about errors precluded the use of bivariate logistic regression. Therefore, to explore the relationship between race and language we used a Fischer's exact test to compare concern about medical errors between white and non‐white participants who were very comfortable with English.

We used multivariate logistic regression to test our hypothesis that greater self‐efficacy would be associated with less concern about medical errors after adjusting for the aforementioned covariates and demographics, excluding child gender. We had no a priori reason to expect that child gender would affect parental self‐efficacy or parental concern about errors and did not include it in the regression model. In order to provide a more clinically relevant interpretation of our results, we calculated adjusted predicted probabilities for the 25%, 50%, and 75% PEPPI scores using the mean for all other variables in the model.

We conducted post‐hoc analysis using a likelihood‐ratio test to determine if the hospitalization variable was significant in the multivariate regression model. We conducted additional post‐hoc analysis using bivariate logistic regression to explore the relationship between concern about medical errors and the following independent variables: hospitalization for >3 days after birth (yes/no); previous hospitalization for >1 week (yes/no); parents' experience with the hospital system (a lot, some, not sure, a little, none); overall perception of child's health (excellent, very good, good, fair); previous hospitalizations for other children (yes, no, no other children); rating of care that child has received (excellent vs. other [very good, good, fair]). We incorporated any significant associations (P < 0.05) into our preexisting multivariate model.

Results

During the time period of our study, 278 parents were eligible to participate. Eighty‐five parents could not be surveyed either because they could not be reached despite multiple attempts (eg, out of the room, speaking with physicians) or because the child had already been discharged. Of the 193 parents approached, 130 agreed to take the survey. Two parents who agreed to complete the survey forgot to return it before their children were discharged. Demographics of respondents and nonparticipants are presented in Table 1. The distribution of self‐efficacy scores was skewed, with a mean score of 45 (median 46, range 5‐50) on a 50‐point scale, consistent with previous studies in adults.18

| Characteristics | Respondents (n = 130) | Number Missed (n = 85) | Number Refused (n = 61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Parent's mean age | 34 years (range: 18‐51) | NA | NA |

| Parent sex female, n (%) | 105 (80.8) | NA | NA |

| Parental education, n (%) | |||

| College or higher | 65 (50.4) | ||

| Some college | 34 (26.4) | ||

| High school or less | 30 (23.3) | NA | NA |

| Parental race, n (%) | |||

| White | 86 (67.2) | ||

| Non‐White | 42 (32.8) | NA | NA |

| Parent's social desirability score, mean (SD) | 7.0 (2.0) | NA | NA |

| Child's median age | 21.4 months (range: 1 day‐17.8 years) | 24 months | 24 months |

| Child's sex female, n (%) | 63 (48.5) | 36 (42) | 35 (57) |

| Number of previous hospitalizations (child), n (%) | |||

| None | 68 (53.1) | ||

| 1 | 26 (20.3) | ||

| 2 | 19 (14.8) | ||

| 3 | 15 (11.7) | NA | NA |

| Number of chronic medical conditions (child), n (%) | |||

| None | 56 (48.7) | ||

| 1 | 34 (29.6) | ||

| 2 | 25 (21.8) | NA | NA |

| Parent's comfort expressing concerns in English, n (%) | NA | NA | |

| Very comfortable | 109 (83.9) | ||

| Less than very comfortable | 21 (16.1) | ||

| Self‐efficacy score (parent), mean (SD) | 45 (6.3) | NA | NA |

Eighty‐two parents (63% of respondents) Agreed or Strongly Agreed with the statement When my child is in the hospital I feel that I need to watch over his/her care in order to make sure that mistakes aren't made (Figure 1). In bivariate analyses, non‐white race (Table 2) and English proficiency (P = 0.002) were significantly associated with parental concern about medical errors. Notably, all respondents who were not very comfortable with English agreed that they felt the need to watch over their child's care to ensure that mistakes do not happen. The association between self‐efficacy with physician interactions and concern was nearly significant (Table 2).

| Variable | Crude Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Parent age (years) | 1.01 | 0.95‐1.06 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 0.95‐1.15 | 0.36 |

| Parent gender | ||||||

| Female | Referent | |||||

| Male | 0.86 | 0.32‐2.35 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.20‐2.79 | 0.68 |

| Age of child (months) | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.83 |

| Parental education | ||||||

| College or higher | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Some college | 0.48 | 0.18‐1.26 | 0.14 | 0.3 | 0.07‐1.13 | 0.07 |

| High school or less | 1.39 | 0.48‐4.00 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.1‐2.2 | 0.38 |

| Parental race | ||||||

| White | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Non‐White | 5.00* | 1.61‐15.56 | 0.005 | 4.9 | 1.19‐20.4 | 0.03 |

| Previous hospitalization (child) | ||||||

| None | Referent | Referent | ||||

| 1 | 0.44 | 0.16‐1.20 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.04‐0.69 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 0.89 | 0.27‐2.87 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 0.13‐2.83 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 0.91 | 0.21‐3.84 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.12‐5.06 | 0.8 |

| Number of chronic medical conditions | 0.86 | 0.67‐1.11 | 0.26 | 1.05 | 0.74‐1.50 | 0.78 |

| Social desirability score (parent) | 0.99 | 0.81‐1.21 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.76‐1.29 | 0.9 |

| Self‐efficacy score (parent) | 0.90 | 0.81‐1.00 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.73‐0.95 | 0.006* |

In multivariate analysis, self‐efficacy was independently associated with parental report about the need to watch over a child's care (odds ratio [OR], 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72‐0.92). In prediction models, with self‐efficacy scores of 44 (25th percentile), 46 (50th percentile), and 49 (75th percentile), about 72.2% (59.1‐82.3), 64.2% (51.8‐75.0), and 50.8% (35.3‐66.2) of parents, respectively, would feel the need to watch over their child's care to prevent medical errors.

While respondents of non‐white race had the greatest independent odds of reporting a concern for medical errors occurring while their child was hospitalized (OR, 4.9; 95% CI, 1.19‐20.4), we could not reliably determine how much of this effect was due to language instead of to race because the vast majority of parents who reported being less than very comfortable with English were also non‐white (non‐white 90.5% vs. white 9.5%, P < 0.001). In additional analyses we were unable to find a difference in concern about medical errors between white and non‐white parents who were very comfortable with English (data not shown).

Of note, while having 1 hospitalization compared to none was significantly associated with having decreased concern about medical errors (Table 2), the variable hospitalizations was not significant in the model (P = 0.07).

In post‐hoc analysis, we found no association between hospitalization for >3 days after birth, previous hospitalization for >1 week, parents' experience with the hospital system, and overall perception of child's health, previous hospitalizations for other children. While rating of care that child received was significantly associated with parents' concern about medical errors in the bivariate analysis, it did not remain significant in multivariate analysis and did not substantially change the magnitude or significance of previous associations.

Discussion

In our study, we found that nearly two‐thirds of parents of children admitted to the general pediatric service of a tertiary care children's hospital felt the need to watch over their child's care to ensure that mistakes would not be made. We also found that a parent's self‐efficacy interacting with physicians was associated with less parental concern for medical errors.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically survey parents' concerns about medical errors during a child's hospitalization and to evaluate factors associated with this concern. The immediate question prompted by our findings is whether the fact that 63% of parents are concerned is alarming because it is too low or too high. Some might contend that concern about medical errors is an appropriate and desirable response because it may motivate parents to become more vigilant about the medical care that their child is receiving. However, others may challenge that such concern may indicate a feeling of powerlessness to act to prevent potential errors. In our study, the relationship between higher self‐efficacy and less parental concern raises the possibility that parents with higher levels of self‐efficacy with physician interactions may feel more comfortable communicating with physicians, which in turn may temper parents' concerns about medical errors during hospitalization.

It is equally plausible that concern about medical errors during hospitalization may motivate parents to become involved in their child's medical care and, in turn, lead them to feel empowered to prevent medical errors and so ease their concerns. It is conceivable that experience with past medical errors may fuel a parent's need to watch over their child's care to prevent additional medical errors. Future studies should address the independent effect of past medical errors on parental concern about medical errors.

In this study, all parents who reported being very uncomfortable with English and parents of non‐white race felt the need to watch over their child's care to help prevent errors. A previous survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults found greater proportion of non‐white adults were very concerned about errors or mistakes happening when receiving care at a hospital (blacks 62%, Hispanics 57%, whites 44%).26 However, in our study, the relationship between race and concern is likely mediated by language since many of the parents who described themselves as other than white also reported being not very comfortable with English and we could not find an effect of race on concern among parents who were very comfortable with English. Indeed, previous studies have linked decreased English proficiency to medical errors with potential clinical consequence.27

Given our previous investigation of the relationship between self‐efficacy and parent participation in medical decisions during a child's hospitalization, we conducted post‐hoc analyses exploring the association between parents' self‐report of participation in medical decisions and concern about medical errors during their child's hospitalization.16 Using a simple logistic regression we did not find any association. However, we advise caution in interpreting and generalizing these results because the study was not powered to adequately evaluate this association.

There are additional limitations in our study to be noted. First, this question has not been used previously to assess parental concern about medical errors, so future work will need to focus on assessing its reliability and validity. Second, it is also possible that parents' concern for medical errors is mitigated by the complexity of their child's healthcare.5 We attempted to address this issue by controlling for the child's number of chronic illnesses. However, it is possible that our metric did not capture the level of complexity associated with different types of chronic conditions. Moreover, additional variables such as health insurance type, parental physical and mental health, and quality of interactions with the nursing staff may confound the relationships that we observed. Future studies should examine the effect of these variables on parents' self‐efficacy and their concern about medical errors.

Third, we surveyed parents at a single institution and, as such, differences in demographics and hospital‐specific practices related to patient‐physician interactions may prevent generalization of our findings to other institutions. For example, the parents in our survey had a higher average education level than the general population and the racial makeup of our population was not nationally representative. Also, due to HIPAA constraints, we were unable to collect extensive demographic information on parents and children who were missed or those who refused to participate in the study, which also could conceivably influence the strength of our findings.

Fourth, we adapted a validated adult measure of self‐efficacy for use in pediatrics. The patient‐physician self‐efficacy scale, the PEPPI, did have a skewed distribution in our study, although this performance is consistent with adult studies18 and in post‐hoc analyses, outlier PEPPI scores did not have a significant effect on the magnitude of the relationship we observed between self‐efficacy and parental concern about medical errors. However, the reading level of this instrument is ninth grade, which may impact the generalization of our findings to populations with lower literacy levels.

Fifth, we excluded parents who were unsure about their concern from our analyses. In post‐hoc multivariate regression analyses, reassignment of unsure responses to either agree or disagree did not result in any change in odds ratio for any endpoint.

Finally, it is possible that parental concern was influenced by social desirability bias in that parents may have been less likely to report concern about medical errors during a hospitalization because of fear of the implications it might have for their child's care. We attempted to control for this effect by adjusting for social desirability bias using the Marlowe‐Crowne scale. This scale is commonly used in behavioral science research to account for such response bias and has been recommended by the NIH Consortium on Behavior Change for use in behavioral change research related to health.24

Within the context of these limitations, we feel that our study contributes an important first step toward characterizing the scope of parental concern about medical errors during pediatric hospitalizations and understanding the relationship of self‐efficacy with physician interactions to this concern. Devising a quality initiative program to improve parents' self‐efficacy interacting with physicians might help to temper parents' concerns about medical errors while also encouraging their involvement in their child's medical care. Such a program would likely prove most beneficial if it sought to improve self‐efficacy among parents with lower English proficiency given that this group had the highest concern for medical errors. Possible interventions might include more ready access to interpreters or use of visual aids.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.Washington, DC:National Academy Press;2001.

- ,,, et al.Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.JAMA.2001;285(16):2114–2120.

- ,.Pediatric patient safety in hospitals: a national picture in 2000.Pediatrics.2004;113(6):1741–1746.

- ,,,,,.Brief report: hospitalized patients' attitudes about and participation in error prevention.J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(4):367–370.

- ,,, et al.Patients' concerns about medical errors during hospitalization.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(1):5–14.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.20 Tips to Help Prevent Medical Errors in Children. Patient Fact Sheet. 2009, AHRQ Publication No. 02‐P034.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Speak Up Initiatives. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/SpeakUp. Accessed May 2009.

- .Self‐efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change.Psychol Rev.1977;84(2):191–215.

- .Self‐Efficacy: The Exercise of Control.New York, NY:W.H. Freeman and Company;1997.

- ,,,.Psychosocial correlates of physical activity in healthy children.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2001;155(8):897–902.

- ,,,,.Self‐efficacy as a mediator variable for adolescents' adherence to treatment for insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus.Children's Health Care.2000;29(1):47–63.

- ,,.Diabetes regimen behaviors. Predicting adherence.Med Care.1987;25(9):868–881.

- ,,,,,.Pediatrician self‐efficacy for counseling parents of asthmatic children to quit smoking.Pediatrics.2004;113(1 Pt 1):78–81.

- ,,.Examining the relationship of patients' attitudes and beliefs with their self‐reported level of participation in medical decision‐making.Med Care.2005;43(9):865–872.

- ,,,,,.Patient‐physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision.J Clin Oncol.2004;22(15):3091–3098.

- ,,.Toward family‐centered inpatient medical care: the role of parents as participants in medical decisions.J Pediatr.2007;151(6):690–695.

- ,,,,.Perceived efficacy in patient‐physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons.J Am Geriatr Soc.1998;46(7):889–894.

- ,,,.Determinants of participation in treatment decision‐making by older breast cancer patients.Breast Cancer Res Treat.2004;85(3):201–209.

- ,.The CHQ: A User's Manual (2nd printing).Boston, MA:HealthAct;1999.

- ,,,,.The health and well‐being of adolescents: a school‐based population study of the self‐report Child Health Questionnaire.J Adolesc Health.2001;29(2):140–149.

- ,,.The Child Health Questionnaire in children with diabetes: cross‐sectional survey of parent and adolescent‐reported functional health status.Diabet Med.2000;17(10):700–707.

- ,.Semantic style variance in personality questionnaires.J Psychol.1973;85:109–118.

- ,.A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology.J Consult Psychol.1960;24:349–354.

- National Institutes of Health. Behavior Change Consortium‐Recommended Nutrition Measures. Available at:http://www1.od.nih.gov/behaviorchange/measures/nutrition.htm. Accessed May 2009.

- ,,.Response bias influences mental health symptom reporting in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.Ann Behav Med.2001;23(4):313–317.

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.Americans as Health Care Consumers: Update on the Role of Quality Information.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2000.

- ,,, et al.Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters.Pediatrics.2003;111(1):6–14.

The Institute of Medicine report linking between 48,000 and 98,000 deaths annually to medical errors1 has raised awareness about medical errors across all areas of medicine. In pediatrics, medical errors in hospitalized children are associated with significant increases in length of stay, healthcare costs, and death.2, 3 While much attention has been paid to the use of hospital systems to prevent medical errors, there has been considerably less focus on the experiences of patients and their potential role in preventing errors.

Studies have suggested that a significant majority of adult patients are concerned about medical errors during hospitalization.4, 5 However, a similar assessment of parents' concerns about medical errors in pediatrics is lacking. Admittedly, for concern to be constructive it must be linked to action. The Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) currently recommend that parents help prevent errors by becoming active, involved and informed members of their healthcare team and taking part in every decision about (their) child's health care.6, 7 However, the extent to which parental concern about medical errors is related to a parent's self‐efficacy, or confidence, interacting with physicians is unknown.

Self‐efficacy is a construct used in social cognitive theory to explain behavior change.8 It refers to an individual's belief in (his/her) capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments or a desired outcome.9 Self‐efficacy is not a general concept; it must be discussed in reference to a specific activity. In healthcare it has been associated not only with willingness to adopt preventive strategies,10 but also with treatment adherence,11, 12 behavior change,13 and with greater patient participation in healthcare decision‐making.14, 15

In this study we had 2 objectives. First, we sought to assess the proportion of parents of hospitalized children who are concerned about medical errors. Second, we attempted to examine whether a parent's self‐efficacy interacting with physicians was associated with their concern about medical errors for their child. Given that parents with greater self‐efficacy interacting with physicians might feel more empowered to prevent errors and, as such, be more inclined to take an active role to do so, we hypothesized that such parents would be less concerned about medical errors during a pediatric hospitalization.

Subjects and Methods

Population

We surveyed parents of children <18 years of age (including 2 grandparents who will hereafter be referred to as parents) who were admitted to the general medical service of the Children's Hospital & Regional Medical Center (CHRMC) in Seattle, WA, from July through September 2005. This study was approved by the CHRMC Institutional Review Board. Due to stipulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), we were unable to collect extensive information on those parents who were missed or those who refused to participate in the study.

Exclusions

We excluded parents if: (1) they did not feel comfortable answering a written survey in English or Spanish; (2) their child was transferred to the general medical unit either from the intensive care unit (ICU) or from the inpatient unit of another hospital; or (3) they were not present during the hospitalization.

Study Design

We conducted a cross‐sectional self‐administered written survey of parents. The survey was translated into Spanish by a certified Spanish translator. A second independent translator confirmed the accuracy of the translation. Informed consent was obtained from parents before administration of the survey.

Data Collection

Parents were surveyed with a consecutive sampling methodology Tuesday through Friday from July 2005 through September 2005. We surveyed parents within 48 hours of admission of their child to the hospital, but after they had an opportunity to speak with the inpatient medical team that was caring for their child. A more detailed discussion of the data collection process has been published previously.16

Dependent Variables

Parental Concern About the Need to Watch for Medical Errors

We assessed parental concerns about medical errors during hospitalization by measuring responses to the statement When my child is in the hospital I feel that I have to watch over the care that he/she is receiving to make sure that mistakes aren't made. Parents reported their agreement/disagreement with this statement using a 5‐point Likert scale. For our analysis we dichotomized the dependent variable into those parents who responded Strongly Agree or Agree vs. those who responded Strongly Disagree or Disagree. We chose to focus on parents who expressed a directional response (eg, agree or disagree) because we felt that such responses were more likely to be correlated with behavior. As a result, we excluded from our primary analysis those participants who responded Unsure. In order to determine the effect of exclusion on our results (given its size), we conducted separate post‐hoc analyses in which we included the Unsure respondents in Agree and Disagree categories, respectively.

Independent Variables

Self‐Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions

The Joint Commission's Speak Up initiative7 recommends that patients and parents interact with their healthcare providers in order to prevent errors. We gauged a parent's confidence of interacting with healthcare providers using an adapted scale of the Perceived Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions (PEPPI) self‐efficacy scale. The PEPPI is a 50‐point self‐efficacy scale that has been validated in older adults.17 The response to each question is recorded on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 where 1 represents not at all confident and 5 represents very confident. Higher scores on this scale have been associated with greater participation in treatment decisions by women with breast cancer.18 We adapted this scale for use in pediatrics (Appendix 1).

Covariates

Prior Hospitalizations and Chronic Illness History

We asked parents to report how many times their child had been hospitalized prior to this current admission (not including birth). We chose to query parents directly because a search of our institutions' medical record database would not capture hospitalizations at other facilities. We categorized the variable for previous hospitalizations as follows: none, 1, 2, 3.

We asked parents to report if prior to this hospitalization they had ever been told by a nurse or doctor that their child had any of a list of chronic medical conditions such as chronic respiratory disease, mental retardation, and seizure disorder, among others. We gave parents the opportunity to specify a medical condition not provided on this list. The list of conditions was the same as that used in the Child Health Questionnaire PF‐28,19 which has been used in national and international studies to measure quality of life in children with and without chronic conditions20, 21 (Appendix 2).

Limited English Proficiency

We assessed the potential for a language barrier to impede communication between parent and healthcare providers by asking parents the following question: How comfortable are you that you can express your concerns and ask questions of your child's doctors in English? We measured parental responses on a 5‐point Likert scale (very comfortable vs. somewhat comfortable, not sure, somewhat uncomfortable, very uncomfortable). For our analyses, we dichotomized responses into those who reported being very comfortable vs. those who chose any other response category.

Social Desirability

We measured the potential for social desirability to bias responses using the Marlowe‐Crowne 2(10) Scale of Social Desirability.22 The Marlowe‐Crowne 2(10) Scale of Social Desirability is a shorter, validated version of the Marlowe‐Crowne Scale.23 This scale has been recommended by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)'s Behavior Change Consortium for use in behavioral change research related to health.24 It has been used in previous studies to account for social desirability bias in studies which involve patient self‐report of attitudes and beliefs.25 We analyzed scores on a continuous scale with higher scores representing greater social desirability bias in responses.

Demographics

We collected the following demographic data on parents: age, gender, race/ethnicity (white non‐Hispanic vs. other), education (high school or less, some college, college or higher). We also recorded the child's age and gender.

Statistical Analysis

Parental Concern for Medical Errors

Univariate statistics were used to report proportions of parents who were concerned about medical errors and to summarize the data for covariates and demographics. We conducted bivariate logistic regression analyses to assess the association between our outcome variable and the independent variable and each covariate, respectively. We used a Fisher's exact test to examine the association between limited English proficiency and our outcome variable because the absence of participants (eg, a zero cell) who were not very comfortable with English and not concerned about errors precluded the use of bivariate logistic regression. Therefore, to explore the relationship between race and language we used a Fischer's exact test to compare concern about medical errors between white and non‐white participants who were very comfortable with English.

We used multivariate logistic regression to test our hypothesis that greater self‐efficacy would be associated with less concern about medical errors after adjusting for the aforementioned covariates and demographics, excluding child gender. We had no a priori reason to expect that child gender would affect parental self‐efficacy or parental concern about errors and did not include it in the regression model. In order to provide a more clinically relevant interpretation of our results, we calculated adjusted predicted probabilities for the 25%, 50%, and 75% PEPPI scores using the mean for all other variables in the model.

We conducted post‐hoc analysis using a likelihood‐ratio test to determine if the hospitalization variable was significant in the multivariate regression model. We conducted additional post‐hoc analysis using bivariate logistic regression to explore the relationship between concern about medical errors and the following independent variables: hospitalization for >3 days after birth (yes/no); previous hospitalization for >1 week (yes/no); parents' experience with the hospital system (a lot, some, not sure, a little, none); overall perception of child's health (excellent, very good, good, fair); previous hospitalizations for other children (yes, no, no other children); rating of care that child has received (excellent vs. other [very good, good, fair]). We incorporated any significant associations (P < 0.05) into our preexisting multivariate model.

Results

During the time period of our study, 278 parents were eligible to participate. Eighty‐five parents could not be surveyed either because they could not be reached despite multiple attempts (eg, out of the room, speaking with physicians) or because the child had already been discharged. Of the 193 parents approached, 130 agreed to take the survey. Two parents who agreed to complete the survey forgot to return it before their children were discharged. Demographics of respondents and nonparticipants are presented in Table 1. The distribution of self‐efficacy scores was skewed, with a mean score of 45 (median 46, range 5‐50) on a 50‐point scale, consistent with previous studies in adults.18

| Characteristics | Respondents (n = 130) | Number Missed (n = 85) | Number Refused (n = 61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Parent's mean age | 34 years (range: 18‐51) | NA | NA |

| Parent sex female, n (%) | 105 (80.8) | NA | NA |

| Parental education, n (%) | |||

| College or higher | 65 (50.4) | ||

| Some college | 34 (26.4) | ||

| High school or less | 30 (23.3) | NA | NA |

| Parental race, n (%) | |||

| White | 86 (67.2) | ||

| Non‐White | 42 (32.8) | NA | NA |

| Parent's social desirability score, mean (SD) | 7.0 (2.0) | NA | NA |

| Child's median age | 21.4 months (range: 1 day‐17.8 years) | 24 months | 24 months |

| Child's sex female, n (%) | 63 (48.5) | 36 (42) | 35 (57) |

| Number of previous hospitalizations (child), n (%) | |||

| None | 68 (53.1) | ||

| 1 | 26 (20.3) | ||

| 2 | 19 (14.8) | ||

| 3 | 15 (11.7) | NA | NA |

| Number of chronic medical conditions (child), n (%) | |||

| None | 56 (48.7) | ||

| 1 | 34 (29.6) | ||

| 2 | 25 (21.8) | NA | NA |

| Parent's comfort expressing concerns in English, n (%) | NA | NA | |

| Very comfortable | 109 (83.9) | ||

| Less than very comfortable | 21 (16.1) | ||

| Self‐efficacy score (parent), mean (SD) | 45 (6.3) | NA | NA |

Eighty‐two parents (63% of respondents) Agreed or Strongly Agreed with the statement When my child is in the hospital I feel that I need to watch over his/her care in order to make sure that mistakes aren't made (Figure 1). In bivariate analyses, non‐white race (Table 2) and English proficiency (P = 0.002) were significantly associated with parental concern about medical errors. Notably, all respondents who were not very comfortable with English agreed that they felt the need to watch over their child's care to ensure that mistakes do not happen. The association between self‐efficacy with physician interactions and concern was nearly significant (Table 2).

| Variable | Crude Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Parent age (years) | 1.01 | 0.95‐1.06 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 0.95‐1.15 | 0.36 |

| Parent gender | ||||||

| Female | Referent | |||||

| Male | 0.86 | 0.32‐2.35 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.20‐2.79 | 0.68 |

| Age of child (months) | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.83 |

| Parental education | ||||||

| College or higher | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Some college | 0.48 | 0.18‐1.26 | 0.14 | 0.3 | 0.07‐1.13 | 0.07 |

| High school or less | 1.39 | 0.48‐4.00 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.1‐2.2 | 0.38 |

| Parental race | ||||||

| White | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Non‐White | 5.00* | 1.61‐15.56 | 0.005 | 4.9 | 1.19‐20.4 | 0.03 |

| Previous hospitalization (child) | ||||||

| None | Referent | Referent | ||||

| 1 | 0.44 | 0.16‐1.20 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.04‐0.69 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 0.89 | 0.27‐2.87 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 0.13‐2.83 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 0.91 | 0.21‐3.84 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.12‐5.06 | 0.8 |

| Number of chronic medical conditions | 0.86 | 0.67‐1.11 | 0.26 | 1.05 | 0.74‐1.50 | 0.78 |

| Social desirability score (parent) | 0.99 | 0.81‐1.21 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.76‐1.29 | 0.9 |

| Self‐efficacy score (parent) | 0.90 | 0.81‐1.00 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.73‐0.95 | 0.006* |

In multivariate analysis, self‐efficacy was independently associated with parental report about the need to watch over a child's care (odds ratio [OR], 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72‐0.92). In prediction models, with self‐efficacy scores of 44 (25th percentile), 46 (50th percentile), and 49 (75th percentile), about 72.2% (59.1‐82.3), 64.2% (51.8‐75.0), and 50.8% (35.3‐66.2) of parents, respectively, would feel the need to watch over their child's care to prevent medical errors.

While respondents of non‐white race had the greatest independent odds of reporting a concern for medical errors occurring while their child was hospitalized (OR, 4.9; 95% CI, 1.19‐20.4), we could not reliably determine how much of this effect was due to language instead of to race because the vast majority of parents who reported being less than very comfortable with English were also non‐white (non‐white 90.5% vs. white 9.5%, P < 0.001). In additional analyses we were unable to find a difference in concern about medical errors between white and non‐white parents who were very comfortable with English (data not shown).

Of note, while having 1 hospitalization compared to none was significantly associated with having decreased concern about medical errors (Table 2), the variable hospitalizations was not significant in the model (P = 0.07).

In post‐hoc analysis, we found no association between hospitalization for >3 days after birth, previous hospitalization for >1 week, parents' experience with the hospital system, and overall perception of child's health, previous hospitalizations for other children. While rating of care that child received was significantly associated with parents' concern about medical errors in the bivariate analysis, it did not remain significant in multivariate analysis and did not substantially change the magnitude or significance of previous associations.

Discussion

In our study, we found that nearly two‐thirds of parents of children admitted to the general pediatric service of a tertiary care children's hospital felt the need to watch over their child's care to ensure that mistakes would not be made. We also found that a parent's self‐efficacy interacting with physicians was associated with less parental concern for medical errors.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically survey parents' concerns about medical errors during a child's hospitalization and to evaluate factors associated with this concern. The immediate question prompted by our findings is whether the fact that 63% of parents are concerned is alarming because it is too low or too high. Some might contend that concern about medical errors is an appropriate and desirable response because it may motivate parents to become more vigilant about the medical care that their child is receiving. However, others may challenge that such concern may indicate a feeling of powerlessness to act to prevent potential errors. In our study, the relationship between higher self‐efficacy and less parental concern raises the possibility that parents with higher levels of self‐efficacy with physician interactions may feel more comfortable communicating with physicians, which in turn may temper parents' concerns about medical errors during hospitalization.

It is equally plausible that concern about medical errors during hospitalization may motivate parents to become involved in their child's medical care and, in turn, lead them to feel empowered to prevent medical errors and so ease their concerns. It is conceivable that experience with past medical errors may fuel a parent's need to watch over their child's care to prevent additional medical errors. Future studies should address the independent effect of past medical errors on parental concern about medical errors.

In this study, all parents who reported being very uncomfortable with English and parents of non‐white race felt the need to watch over their child's care to help prevent errors. A previous survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults found greater proportion of non‐white adults were very concerned about errors or mistakes happening when receiving care at a hospital (blacks 62%, Hispanics 57%, whites 44%).26 However, in our study, the relationship between race and concern is likely mediated by language since many of the parents who described themselves as other than white also reported being not very comfortable with English and we could not find an effect of race on concern among parents who were very comfortable with English. Indeed, previous studies have linked decreased English proficiency to medical errors with potential clinical consequence.27

Given our previous investigation of the relationship between self‐efficacy and parent participation in medical decisions during a child's hospitalization, we conducted post‐hoc analyses exploring the association between parents' self‐report of participation in medical decisions and concern about medical errors during their child's hospitalization.16 Using a simple logistic regression we did not find any association. However, we advise caution in interpreting and generalizing these results because the study was not powered to adequately evaluate this association.

There are additional limitations in our study to be noted. First, this question has not been used previously to assess parental concern about medical errors, so future work will need to focus on assessing its reliability and validity. Second, it is also possible that parents' concern for medical errors is mitigated by the complexity of their child's healthcare.5 We attempted to address this issue by controlling for the child's number of chronic illnesses. However, it is possible that our metric did not capture the level of complexity associated with different types of chronic conditions. Moreover, additional variables such as health insurance type, parental physical and mental health, and quality of interactions with the nursing staff may confound the relationships that we observed. Future studies should examine the effect of these variables on parents' self‐efficacy and their concern about medical errors.

Third, we surveyed parents at a single institution and, as such, differences in demographics and hospital‐specific practices related to patient‐physician interactions may prevent generalization of our findings to other institutions. For example, the parents in our survey had a higher average education level than the general population and the racial makeup of our population was not nationally representative. Also, due to HIPAA constraints, we were unable to collect extensive demographic information on parents and children who were missed or those who refused to participate in the study, which also could conceivably influence the strength of our findings.

Fourth, we adapted a validated adult measure of self‐efficacy for use in pediatrics. The patient‐physician self‐efficacy scale, the PEPPI, did have a skewed distribution in our study, although this performance is consistent with adult studies18 and in post‐hoc analyses, outlier PEPPI scores did not have a significant effect on the magnitude of the relationship we observed between self‐efficacy and parental concern about medical errors. However, the reading level of this instrument is ninth grade, which may impact the generalization of our findings to populations with lower literacy levels.

Fifth, we excluded parents who were unsure about their concern from our analyses. In post‐hoc multivariate regression analyses, reassignment of unsure responses to either agree or disagree did not result in any change in odds ratio for any endpoint.

Finally, it is possible that parental concern was influenced by social desirability bias in that parents may have been less likely to report concern about medical errors during a hospitalization because of fear of the implications it might have for their child's care. We attempted to control for this effect by adjusting for social desirability bias using the Marlowe‐Crowne scale. This scale is commonly used in behavioral science research to account for such response bias and has been recommended by the NIH Consortium on Behavior Change for use in behavioral change research related to health.24

Within the context of these limitations, we feel that our study contributes an important first step toward characterizing the scope of parental concern about medical errors during pediatric hospitalizations and understanding the relationship of self‐efficacy with physician interactions to this concern. Devising a quality initiative program to improve parents' self‐efficacy interacting with physicians might help to temper parents' concerns about medical errors while also encouraging their involvement in their child's medical care. Such a program would likely prove most beneficial if it sought to improve self‐efficacy among parents with lower English proficiency given that this group had the highest concern for medical errors. Possible interventions might include more ready access to interpreters or use of visual aids.

The Institute of Medicine report linking between 48,000 and 98,000 deaths annually to medical errors1 has raised awareness about medical errors across all areas of medicine. In pediatrics, medical errors in hospitalized children are associated with significant increases in length of stay, healthcare costs, and death.2, 3 While much attention has been paid to the use of hospital systems to prevent medical errors, there has been considerably less focus on the experiences of patients and their potential role in preventing errors.

Studies have suggested that a significant majority of adult patients are concerned about medical errors during hospitalization.4, 5 However, a similar assessment of parents' concerns about medical errors in pediatrics is lacking. Admittedly, for concern to be constructive it must be linked to action. The Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) currently recommend that parents help prevent errors by becoming active, involved and informed members of their healthcare team and taking part in every decision about (their) child's health care.6, 7 However, the extent to which parental concern about medical errors is related to a parent's self‐efficacy, or confidence, interacting with physicians is unknown.

Self‐efficacy is a construct used in social cognitive theory to explain behavior change.8 It refers to an individual's belief in (his/her) capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments or a desired outcome.9 Self‐efficacy is not a general concept; it must be discussed in reference to a specific activity. In healthcare it has been associated not only with willingness to adopt preventive strategies,10 but also with treatment adherence,11, 12 behavior change,13 and with greater patient participation in healthcare decision‐making.14, 15

In this study we had 2 objectives. First, we sought to assess the proportion of parents of hospitalized children who are concerned about medical errors. Second, we attempted to examine whether a parent's self‐efficacy interacting with physicians was associated with their concern about medical errors for their child. Given that parents with greater self‐efficacy interacting with physicians might feel more empowered to prevent errors and, as such, be more inclined to take an active role to do so, we hypothesized that such parents would be less concerned about medical errors during a pediatric hospitalization.

Subjects and Methods

Population

We surveyed parents of children <18 years of age (including 2 grandparents who will hereafter be referred to as parents) who were admitted to the general medical service of the Children's Hospital & Regional Medical Center (CHRMC) in Seattle, WA, from July through September 2005. This study was approved by the CHRMC Institutional Review Board. Due to stipulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), we were unable to collect extensive information on those parents who were missed or those who refused to participate in the study.

Exclusions

We excluded parents if: (1) they did not feel comfortable answering a written survey in English or Spanish; (2) their child was transferred to the general medical unit either from the intensive care unit (ICU) or from the inpatient unit of another hospital; or (3) they were not present during the hospitalization.

Study Design

We conducted a cross‐sectional self‐administered written survey of parents. The survey was translated into Spanish by a certified Spanish translator. A second independent translator confirmed the accuracy of the translation. Informed consent was obtained from parents before administration of the survey.

Data Collection

Parents were surveyed with a consecutive sampling methodology Tuesday through Friday from July 2005 through September 2005. We surveyed parents within 48 hours of admission of their child to the hospital, but after they had an opportunity to speak with the inpatient medical team that was caring for their child. A more detailed discussion of the data collection process has been published previously.16

Dependent Variables

Parental Concern About the Need to Watch for Medical Errors

We assessed parental concerns about medical errors during hospitalization by measuring responses to the statement When my child is in the hospital I feel that I have to watch over the care that he/she is receiving to make sure that mistakes aren't made. Parents reported their agreement/disagreement with this statement using a 5‐point Likert scale. For our analysis we dichotomized the dependent variable into those parents who responded Strongly Agree or Agree vs. those who responded Strongly Disagree or Disagree. We chose to focus on parents who expressed a directional response (eg, agree or disagree) because we felt that such responses were more likely to be correlated with behavior. As a result, we excluded from our primary analysis those participants who responded Unsure. In order to determine the effect of exclusion on our results (given its size), we conducted separate post‐hoc analyses in which we included the Unsure respondents in Agree and Disagree categories, respectively.

Independent Variables

Self‐Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions

The Joint Commission's Speak Up initiative7 recommends that patients and parents interact with their healthcare providers in order to prevent errors. We gauged a parent's confidence of interacting with healthcare providers using an adapted scale of the Perceived Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions (PEPPI) self‐efficacy scale. The PEPPI is a 50‐point self‐efficacy scale that has been validated in older adults.17 The response to each question is recorded on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 where 1 represents not at all confident and 5 represents very confident. Higher scores on this scale have been associated with greater participation in treatment decisions by women with breast cancer.18 We adapted this scale for use in pediatrics (Appendix 1).

Covariates

Prior Hospitalizations and Chronic Illness History

We asked parents to report how many times their child had been hospitalized prior to this current admission (not including birth). We chose to query parents directly because a search of our institutions' medical record database would not capture hospitalizations at other facilities. We categorized the variable for previous hospitalizations as follows: none, 1, 2, 3.

We asked parents to report if prior to this hospitalization they had ever been told by a nurse or doctor that their child had any of a list of chronic medical conditions such as chronic respiratory disease, mental retardation, and seizure disorder, among others. We gave parents the opportunity to specify a medical condition not provided on this list. The list of conditions was the same as that used in the Child Health Questionnaire PF‐28,19 which has been used in national and international studies to measure quality of life in children with and without chronic conditions20, 21 (Appendix 2).

Limited English Proficiency

We assessed the potential for a language barrier to impede communication between parent and healthcare providers by asking parents the following question: How comfortable are you that you can express your concerns and ask questions of your child's doctors in English? We measured parental responses on a 5‐point Likert scale (very comfortable vs. somewhat comfortable, not sure, somewhat uncomfortable, very uncomfortable). For our analyses, we dichotomized responses into those who reported being very comfortable vs. those who chose any other response category.

Social Desirability

We measured the potential for social desirability to bias responses using the Marlowe‐Crowne 2(10) Scale of Social Desirability.22 The Marlowe‐Crowne 2(10) Scale of Social Desirability is a shorter, validated version of the Marlowe‐Crowne Scale.23 This scale has been recommended by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)'s Behavior Change Consortium for use in behavioral change research related to health.24 It has been used in previous studies to account for social desirability bias in studies which involve patient self‐report of attitudes and beliefs.25 We analyzed scores on a continuous scale with higher scores representing greater social desirability bias in responses.

Demographics

We collected the following demographic data on parents: age, gender, race/ethnicity (white non‐Hispanic vs. other), education (high school or less, some college, college or higher). We also recorded the child's age and gender.

Statistical Analysis

Parental Concern for Medical Errors

Univariate statistics were used to report proportions of parents who were concerned about medical errors and to summarize the data for covariates and demographics. We conducted bivariate logistic regression analyses to assess the association between our outcome variable and the independent variable and each covariate, respectively. We used a Fisher's exact test to examine the association between limited English proficiency and our outcome variable because the absence of participants (eg, a zero cell) who were not very comfortable with English and not concerned about errors precluded the use of bivariate logistic regression. Therefore, to explore the relationship between race and language we used a Fischer's exact test to compare concern about medical errors between white and non‐white participants who were very comfortable with English.

We used multivariate logistic regression to test our hypothesis that greater self‐efficacy would be associated with less concern about medical errors after adjusting for the aforementioned covariates and demographics, excluding child gender. We had no a priori reason to expect that child gender would affect parental self‐efficacy or parental concern about errors and did not include it in the regression model. In order to provide a more clinically relevant interpretation of our results, we calculated adjusted predicted probabilities for the 25%, 50%, and 75% PEPPI scores using the mean for all other variables in the model.

We conducted post‐hoc analysis using a likelihood‐ratio test to determine if the hospitalization variable was significant in the multivariate regression model. We conducted additional post‐hoc analysis using bivariate logistic regression to explore the relationship between concern about medical errors and the following independent variables: hospitalization for >3 days after birth (yes/no); previous hospitalization for >1 week (yes/no); parents' experience with the hospital system (a lot, some, not sure, a little, none); overall perception of child's health (excellent, very good, good, fair); previous hospitalizations for other children (yes, no, no other children); rating of care that child has received (excellent vs. other [very good, good, fair]). We incorporated any significant associations (P < 0.05) into our preexisting multivariate model.

Results

During the time period of our study, 278 parents were eligible to participate. Eighty‐five parents could not be surveyed either because they could not be reached despite multiple attempts (eg, out of the room, speaking with physicians) or because the child had already been discharged. Of the 193 parents approached, 130 agreed to take the survey. Two parents who agreed to complete the survey forgot to return it before their children were discharged. Demographics of respondents and nonparticipants are presented in Table 1. The distribution of self‐efficacy scores was skewed, with a mean score of 45 (median 46, range 5‐50) on a 50‐point scale, consistent with previous studies in adults.18

| Characteristics | Respondents (n = 130) | Number Missed (n = 85) | Number Refused (n = 61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Parent's mean age | 34 years (range: 18‐51) | NA | NA |

| Parent sex female, n (%) | 105 (80.8) | NA | NA |

| Parental education, n (%) | |||

| College or higher | 65 (50.4) | ||

| Some college | 34 (26.4) | ||

| High school or less | 30 (23.3) | NA | NA |

| Parental race, n (%) | |||

| White | 86 (67.2) | ||

| Non‐White | 42 (32.8) | NA | NA |

| Parent's social desirability score, mean (SD) | 7.0 (2.0) | NA | NA |

| Child's median age | 21.4 months (range: 1 day‐17.8 years) | 24 months | 24 months |

| Child's sex female, n (%) | 63 (48.5) | 36 (42) | 35 (57) |

| Number of previous hospitalizations (child), n (%) | |||

| None | 68 (53.1) | ||

| 1 | 26 (20.3) | ||

| 2 | 19 (14.8) | ||

| 3 | 15 (11.7) | NA | NA |

| Number of chronic medical conditions (child), n (%) | |||

| None | 56 (48.7) | ||

| 1 | 34 (29.6) | ||

| 2 | 25 (21.8) | NA | NA |

| Parent's comfort expressing concerns in English, n (%) | NA | NA | |

| Very comfortable | 109 (83.9) | ||

| Less than very comfortable | 21 (16.1) | ||

| Self‐efficacy score (parent), mean (SD) | 45 (6.3) | NA | NA |

Eighty‐two parents (63% of respondents) Agreed or Strongly Agreed with the statement When my child is in the hospital I feel that I need to watch over his/her care in order to make sure that mistakes aren't made (Figure 1). In bivariate analyses, non‐white race (Table 2) and English proficiency (P = 0.002) were significantly associated with parental concern about medical errors. Notably, all respondents who were not very comfortable with English agreed that they felt the need to watch over their child's care to ensure that mistakes do not happen. The association between self‐efficacy with physician interactions and concern was nearly significant (Table 2).

| Variable | Crude Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Parent age (years) | 1.01 | 0.95‐1.06 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 0.95‐1.15 | 0.36 |

| Parent gender | ||||||

| Female | Referent | |||||

| Male | 0.86 | 0.32‐2.35 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.20‐2.79 | 0.68 |

| Age of child (months) | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.83 |

| Parental education | ||||||

| College or higher | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Some college | 0.48 | 0.18‐1.26 | 0.14 | 0.3 | 0.07‐1.13 | 0.07 |

| High school or less | 1.39 | 0.48‐4.00 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.1‐2.2 | 0.38 |

| Parental race | ||||||

| White | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Non‐White | 5.00* | 1.61‐15.56 | 0.005 | 4.9 | 1.19‐20.4 | 0.03 |

| Previous hospitalization (child) | ||||||

| None | Referent | Referent | ||||

| 1 | 0.44 | 0.16‐1.20 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.04‐0.69 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 0.89 | 0.27‐2.87 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 0.13‐2.83 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 0.91 | 0.21‐3.84 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.12‐5.06 | 0.8 |

| Number of chronic medical conditions | 0.86 | 0.67‐1.11 | 0.26 | 1.05 | 0.74‐1.50 | 0.78 |

| Social desirability score (parent) | 0.99 | 0.81‐1.21 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.76‐1.29 | 0.9 |

| Self‐efficacy score (parent) | 0.90 | 0.81‐1.00 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.73‐0.95 | 0.006* |

In multivariate analysis, self‐efficacy was independently associated with parental report about the need to watch over a child's care (odds ratio [OR], 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72‐0.92). In prediction models, with self‐efficacy scores of 44 (25th percentile), 46 (50th percentile), and 49 (75th percentile), about 72.2% (59.1‐82.3), 64.2% (51.8‐75.0), and 50.8% (35.3‐66.2) of parents, respectively, would feel the need to watch over their child's care to prevent medical errors.

While respondents of non‐white race had the greatest independent odds of reporting a concern for medical errors occurring while their child was hospitalized (OR, 4.9; 95% CI, 1.19‐20.4), we could not reliably determine how much of this effect was due to language instead of to race because the vast majority of parents who reported being less than very comfortable with English were also non‐white (non‐white 90.5% vs. white 9.5%, P < 0.001). In additional analyses we were unable to find a difference in concern about medical errors between white and non‐white parents who were very comfortable with English (data not shown).

Of note, while having 1 hospitalization compared to none was significantly associated with having decreased concern about medical errors (Table 2), the variable hospitalizations was not significant in the model (P = 0.07).

In post‐hoc analysis, we found no association between hospitalization for >3 days after birth, previous hospitalization for >1 week, parents' experience with the hospital system, and overall perception of child's health, previous hospitalizations for other children. While rating of care that child received was significantly associated with parents' concern about medical errors in the bivariate analysis, it did not remain significant in multivariate analysis and did not substantially change the magnitude or significance of previous associations.

Discussion

In our study, we found that nearly two‐thirds of parents of children admitted to the general pediatric service of a tertiary care children's hospital felt the need to watch over their child's care to ensure that mistakes would not be made. We also found that a parent's self‐efficacy interacting with physicians was associated with less parental concern for medical errors.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically survey parents' concerns about medical errors during a child's hospitalization and to evaluate factors associated with this concern. The immediate question prompted by our findings is whether the fact that 63% of parents are concerned is alarming because it is too low or too high. Some might contend that concern about medical errors is an appropriate and desirable response because it may motivate parents to become more vigilant about the medical care that their child is receiving. However, others may challenge that such concern may indicate a feeling of powerlessness to act to prevent potential errors. In our study, the relationship between higher self‐efficacy and less parental concern raises the possibility that parents with higher levels of self‐efficacy with physician interactions may feel more comfortable communicating with physicians, which in turn may temper parents' concerns about medical errors during hospitalization.

It is equally plausible that concern about medical errors during hospitalization may motivate parents to become involved in their child's medical care and, in turn, lead them to feel empowered to prevent medical errors and so ease their concerns. It is conceivable that experience with past medical errors may fuel a parent's need to watch over their child's care to prevent additional medical errors. Future studies should address the independent effect of past medical errors on parental concern about medical errors.

In this study, all parents who reported being very uncomfortable with English and parents of non‐white race felt the need to watch over their child's care to help prevent errors. A previous survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults found greater proportion of non‐white adults were very concerned about errors or mistakes happening when receiving care at a hospital (blacks 62%, Hispanics 57%, whites 44%).26 However, in our study, the relationship between race and concern is likely mediated by language since many of the parents who described themselves as other than white also reported being not very comfortable with English and we could not find an effect of race on concern among parents who were very comfortable with English. Indeed, previous studies have linked decreased English proficiency to medical errors with potential clinical consequence.27

Given our previous investigation of the relationship between self‐efficacy and parent participation in medical decisions during a child's hospitalization, we conducted post‐hoc analyses exploring the association between parents' self‐report of participation in medical decisions and concern about medical errors during their child's hospitalization.16 Using a simple logistic regression we did not find any association. However, we advise caution in interpreting and generalizing these results because the study was not powered to adequately evaluate this association.

There are additional limitations in our study to be noted. First, this question has not been used previously to assess parental concern about medical errors, so future work will need to focus on assessing its reliability and validity. Second, it is also possible that parents' concern for medical errors is mitigated by the complexity of their child's healthcare.5 We attempted to address this issue by controlling for the child's number of chronic illnesses. However, it is possible that our metric did not capture the level of complexity associated with different types of chronic conditions. Moreover, additional variables such as health insurance type, parental physical and mental health, and quality of interactions with the nursing staff may confound the relationships that we observed. Future studies should examine the effect of these variables on parents' self‐efficacy and their concern about medical errors.

Third, we surveyed parents at a single institution and, as such, differences in demographics and hospital‐specific practices related to patient‐physician interactions may prevent generalization of our findings to other institutions. For example, the parents in our survey had a higher average education level than the general population and the racial makeup of our population was not nationally representative. Also, due to HIPAA constraints, we were unable to collect extensive demographic information on parents and children who were missed or those who refused to participate in the study, which also could conceivably influence the strength of our findings.

Fourth, we adapted a validated adult measure of self‐efficacy for use in pediatrics. The patient‐physician self‐efficacy scale, the PEPPI, did have a skewed distribution in our study, although this performance is consistent with adult studies18 and in post‐hoc analyses, outlier PEPPI scores did not have a significant effect on the magnitude of the relationship we observed between self‐efficacy and parental concern about medical errors. However, the reading level of this instrument is ninth grade, which may impact the generalization of our findings to populations with lower literacy levels.

Fifth, we excluded parents who were unsure about their concern from our analyses. In post‐hoc multivariate regression analyses, reassignment of unsure responses to either agree or disagree did not result in any change in odds ratio for any endpoint.

Finally, it is possible that parental concern was influenced by social desirability bias in that parents may have been less likely to report concern about medical errors during a hospitalization because of fear of the implications it might have for their child's care. We attempted to control for this effect by adjusting for social desirability bias using the Marlowe‐Crowne scale. This scale is commonly used in behavioral science research to account for such response bias and has been recommended by the NIH Consortium on Behavior Change for use in behavioral change research related to health.24

Within the context of these limitations, we feel that our study contributes an important first step toward characterizing the scope of parental concern about medical errors during pediatric hospitalizations and understanding the relationship of self‐efficacy with physician interactions to this concern. Devising a quality initiative program to improve parents' self‐efficacy interacting with physicians might help to temper parents' concerns about medical errors while also encouraging their involvement in their child's medical care. Such a program would likely prove most beneficial if it sought to improve self‐efficacy among parents with lower English proficiency given that this group had the highest concern for medical errors. Possible interventions might include more ready access to interpreters or use of visual aids.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.Washington, DC:National Academy Press;2001.

- ,,, et al.Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.JAMA.2001;285(16):2114–2120.

- ,.Pediatric patient safety in hospitals: a national picture in 2000.Pediatrics.2004;113(6):1741–1746.

- ,,,,,.Brief report: hospitalized patients' attitudes about and participation in error prevention.J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(4):367–370.

- ,,, et al.Patients' concerns about medical errors during hospitalization.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(1):5–14.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.20 Tips to Help Prevent Medical Errors in Children. Patient Fact Sheet. 2009, AHRQ Publication No. 02‐P034.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Speak Up Initiatives. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/SpeakUp. Accessed May 2009.

- .Self‐efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change.Psychol Rev.1977;84(2):191–215.

- .Self‐Efficacy: The Exercise of Control.New York, NY:W.H. Freeman and Company;1997.

- ,,,.Psychosocial correlates of physical activity in healthy children.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2001;155(8):897–902.

- ,,,,.Self‐efficacy as a mediator variable for adolescents' adherence to treatment for insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus.Children's Health Care.2000;29(1):47–63.

- ,,.Diabetes regimen behaviors. Predicting adherence.Med Care.1987;25(9):868–881.

- ,,,,,.Pediatrician self‐efficacy for counseling parents of asthmatic children to quit smoking.Pediatrics.2004;113(1 Pt 1):78–81.

- ,,.Examining the relationship of patients' attitudes and beliefs with their self‐reported level of participation in medical decision‐making.Med Care.2005;43(9):865–872.

- ,,,,,.Patient‐physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision.J Clin Oncol.2004;22(15):3091–3098.

- ,,.Toward family‐centered inpatient medical care: the role of parents as participants in medical decisions.J Pediatr.2007;151(6):690–695.