User login

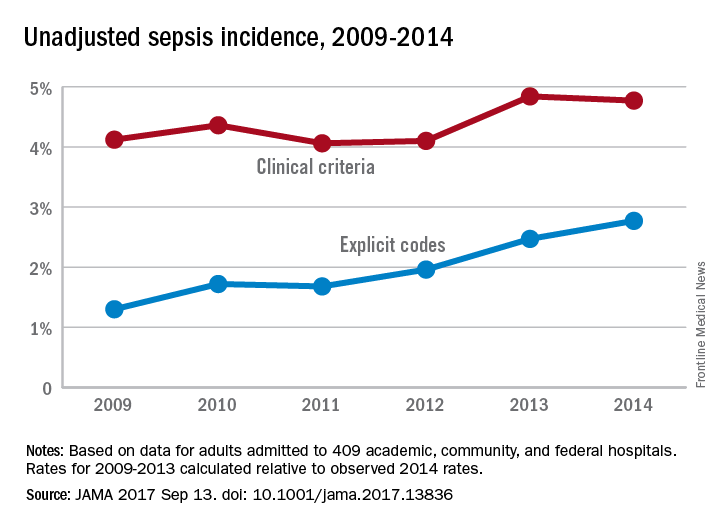

Increase in sepsis incidence stable from 2009 to 2014

The trend for sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, “calculated relative to the observed 2014 rates,” was a stable increase of 0.6% per year using the more accurate of two forms of analysis, investigators reported.

The incidence of sepsis was an adjusted 5.9% among hospitalized adults in 2014, with in-hospital mortality of 15%, according to a retrospective cohort study published online Sept. 13 in JAMA.

“Most studies [of sepsis incidence] have used claims data, but increasing clinical awareness, changes in diagnosis and coding practices, and variable definitions have led to uncertainty about the accuracy of reported trends,” wrote Chanu Rhee, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836).

They used two methods – one involving claims-based estimates using ICD-9-CM codes and the other based on clinical data from electronic health records (EHRs) – to analyze data for more than 2.9 million adults admitted to 409 U.S. academic, community, and federal acute-care hospitals in 2014. The claims-based “explicit-codes” approach used discharge diagnoses of severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), while the EHR-based, clinical-criteria method included blood cultures, antibiotics, and concurrent organ dysfunction with or without the criterion of a lactate level of 2.0 mmol/L or greater, the investigators said.

The explicit-codes approach produced an increase of 10.3% per year in sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, compared with 0.6% per year for the clinical-criteria approach, while in-hospital mortality declined by 7% a year using explicit codes and 3.3% using clinical criteria, Dr. Rhee and his associates reported.

“EHR-based criteria were more sensitive than explicit sepsis codes on medical record review, with comparable [positive predictive value]; EHR-based criteria had similar sensitivity to implicit or explicit codes combined but higher [positive predictive value],” they said.

The estimates provided by Dr. Rhee and his associates provide “a clearer understanding of trends in the incidence and mortality of sepsis in the United States but also a better understanding of the challenges in improving ICD coding to accurately document the global burden of sepsis,” Kristina E. Rudd, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates said in an editorial (JAMA 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13697).

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Three of Dr. Rhee’s associates reported receiving personal fees from private companies or serving on advisory boards or as consultants. No other authors reported disclosures. Dr. Rudd and her associates had no conflicts of interest to report.

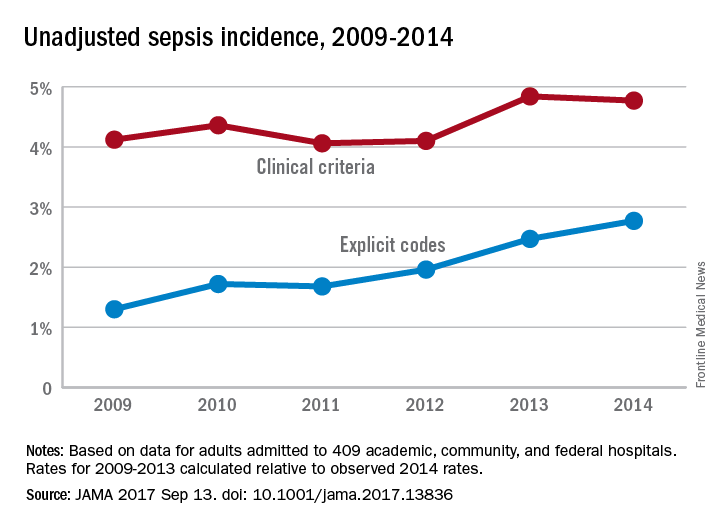

The trend for sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, “calculated relative to the observed 2014 rates,” was a stable increase of 0.6% per year using the more accurate of two forms of analysis, investigators reported.

The incidence of sepsis was an adjusted 5.9% among hospitalized adults in 2014, with in-hospital mortality of 15%, according to a retrospective cohort study published online Sept. 13 in JAMA.

“Most studies [of sepsis incidence] have used claims data, but increasing clinical awareness, changes in diagnosis and coding practices, and variable definitions have led to uncertainty about the accuracy of reported trends,” wrote Chanu Rhee, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836).

They used two methods – one involving claims-based estimates using ICD-9-CM codes and the other based on clinical data from electronic health records (EHRs) – to analyze data for more than 2.9 million adults admitted to 409 U.S. academic, community, and federal acute-care hospitals in 2014. The claims-based “explicit-codes” approach used discharge diagnoses of severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), while the EHR-based, clinical-criteria method included blood cultures, antibiotics, and concurrent organ dysfunction with or without the criterion of a lactate level of 2.0 mmol/L or greater, the investigators said.

The explicit-codes approach produced an increase of 10.3% per year in sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, compared with 0.6% per year for the clinical-criteria approach, while in-hospital mortality declined by 7% a year using explicit codes and 3.3% using clinical criteria, Dr. Rhee and his associates reported.

“EHR-based criteria were more sensitive than explicit sepsis codes on medical record review, with comparable [positive predictive value]; EHR-based criteria had similar sensitivity to implicit or explicit codes combined but higher [positive predictive value],” they said.

The estimates provided by Dr. Rhee and his associates provide “a clearer understanding of trends in the incidence and mortality of sepsis in the United States but also a better understanding of the challenges in improving ICD coding to accurately document the global burden of sepsis,” Kristina E. Rudd, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates said in an editorial (JAMA 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13697).

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Three of Dr. Rhee’s associates reported receiving personal fees from private companies or serving on advisory boards or as consultants. No other authors reported disclosures. Dr. Rudd and her associates had no conflicts of interest to report.

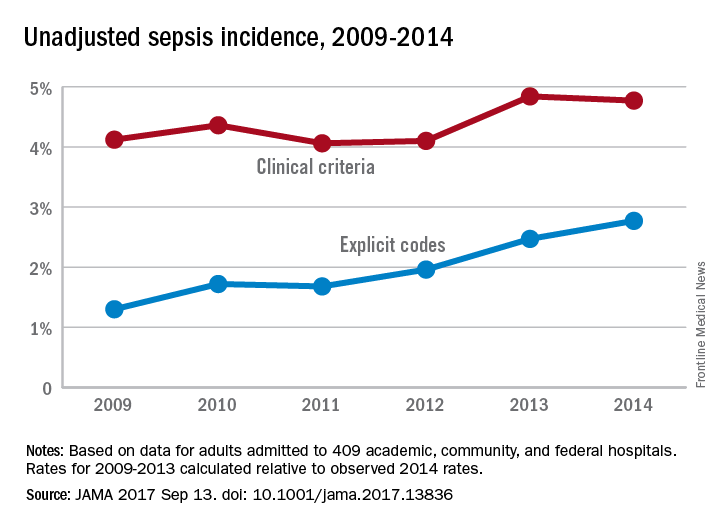

The trend for sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, “calculated relative to the observed 2014 rates,” was a stable increase of 0.6% per year using the more accurate of two forms of analysis, investigators reported.

The incidence of sepsis was an adjusted 5.9% among hospitalized adults in 2014, with in-hospital mortality of 15%, according to a retrospective cohort study published online Sept. 13 in JAMA.

“Most studies [of sepsis incidence] have used claims data, but increasing clinical awareness, changes in diagnosis and coding practices, and variable definitions have led to uncertainty about the accuracy of reported trends,” wrote Chanu Rhee, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836).

They used two methods – one involving claims-based estimates using ICD-9-CM codes and the other based on clinical data from electronic health records (EHRs) – to analyze data for more than 2.9 million adults admitted to 409 U.S. academic, community, and federal acute-care hospitals in 2014. The claims-based “explicit-codes” approach used discharge diagnoses of severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), while the EHR-based, clinical-criteria method included blood cultures, antibiotics, and concurrent organ dysfunction with or without the criterion of a lactate level of 2.0 mmol/L or greater, the investigators said.

The explicit-codes approach produced an increase of 10.3% per year in sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, compared with 0.6% per year for the clinical-criteria approach, while in-hospital mortality declined by 7% a year using explicit codes and 3.3% using clinical criteria, Dr. Rhee and his associates reported.

“EHR-based criteria were more sensitive than explicit sepsis codes on medical record review, with comparable [positive predictive value]; EHR-based criteria had similar sensitivity to implicit or explicit codes combined but higher [positive predictive value],” they said.

The estimates provided by Dr. Rhee and his associates provide “a clearer understanding of trends in the incidence and mortality of sepsis in the United States but also a better understanding of the challenges in improving ICD coding to accurately document the global burden of sepsis,” Kristina E. Rudd, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates said in an editorial (JAMA 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13697).

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Three of Dr. Rhee’s associates reported receiving personal fees from private companies or serving on advisory boards or as consultants. No other authors reported disclosures. Dr. Rudd and her associates had no conflicts of interest to report.

FROM JAMA

Sleep Strategies

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

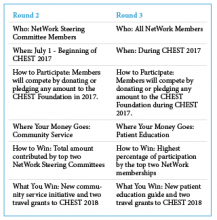

CHEST Foundation NetWorks Challenge

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

Aptiom approved for pediatric partial-onset seizures

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Aptiom (eslicarbazepine acetate) for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in children aged 4-17 years, according to an announcement from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

The approval was based on results of three clinical trials where eslicarbazepine was shown to be safe and well tolerated in pediatric populations. The efficacy of eslicarbazepine has been illustrated in clinical trials in adult populations, and data were extrapolated to support usage in pediatric patients. Eslicarbazepine has previously been approved to treat partial-onset seizures in adults.

Pediatric dosing of eslicarbazepine is based on weight, and the tablets, available in 200-mg, 400-mg, 600-mg, and 800-mg strengths, can be taken whole or crushed, with or without food, according to the prescribing information.

“The unpredictable nature of seizures can be disruptive in the lives of these young people and their families, friends, and community. It is important that physicians have additional treatment options that address patient needs,” Steven Wolf, MD, director of pediatric epilepsy at Mount Sinai Health System, said in the announcement.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Aptiom (eslicarbazepine acetate) for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in children aged 4-17 years, according to an announcement from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

The approval was based on results of three clinical trials where eslicarbazepine was shown to be safe and well tolerated in pediatric populations. The efficacy of eslicarbazepine has been illustrated in clinical trials in adult populations, and data were extrapolated to support usage in pediatric patients. Eslicarbazepine has previously been approved to treat partial-onset seizures in adults.

Pediatric dosing of eslicarbazepine is based on weight, and the tablets, available in 200-mg, 400-mg, 600-mg, and 800-mg strengths, can be taken whole or crushed, with or without food, according to the prescribing information.

“The unpredictable nature of seizures can be disruptive in the lives of these young people and their families, friends, and community. It is important that physicians have additional treatment options that address patient needs,” Steven Wolf, MD, director of pediatric epilepsy at Mount Sinai Health System, said in the announcement.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Aptiom (eslicarbazepine acetate) for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in children aged 4-17 years, according to an announcement from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

The approval was based on results of three clinical trials where eslicarbazepine was shown to be safe and well tolerated in pediatric populations. The efficacy of eslicarbazepine has been illustrated in clinical trials in adult populations, and data were extrapolated to support usage in pediatric patients. Eslicarbazepine has previously been approved to treat partial-onset seizures in adults.

Pediatric dosing of eslicarbazepine is based on weight, and the tablets, available in 200-mg, 400-mg, 600-mg, and 800-mg strengths, can be taken whole or crushed, with or without food, according to the prescribing information.

“The unpredictable nature of seizures can be disruptive in the lives of these young people and their families, friends, and community. It is important that physicians have additional treatment options that address patient needs,” Steven Wolf, MD, director of pediatric epilepsy at Mount Sinai Health System, said in the announcement.

NetWorks

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

This month in CHEST : Editor’s picks

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Identifying clinical pathways for injection drug–related infectious sequelae

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

It is not surprising that my medical school – home to a group of passionate thought leaders in health service and policy research, including the Dartmouth Atlas and Accountable Care Organization – required all first-year medical students to take a course called “health care delivery science.”

The course offered me the first glimpse into quality improvement. However, because of a lack of clinical context, much of the course remained theoretical until my clinical years. During the hospital medicine rotation, I took care of a 40-year old patient who was newly diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer. It was challenging to deliver devastatingly bad news. The patient and family, however, were most confused and frustrated by the roles of different specialists and care providers, the purpose and scheduling of procedures, and diet arrangement. I wondered how I could make their experience better.

After several meetings with my mentor, Professor Jonathan Huntington, a hospitalist, MD-PhD researcher, and director of Care Coordination Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC), we identified a research area that has rising interest, importance, and relevance to the rural New Hampshire population. It is about identifying a clinical pathway for injection drug–related infectious sequelae.

Because of the unique bio-socio-psycho needs of injection drug users, hospitalizations due to injection-related infection sequelae often contribute to increased length of stay, readmission rates, and expenses out of state and federal health care funding. Prolonged stays also result in the waste of tertiary care resources for nontertiary needs, underutilization of regional care resources such as community and critical access hospitals, and increased care burden, as most patients travel long distances to obtain care.

We will pilot and implement a clinical pathway in the medicine units and measure length of stay, readmission rate, patient satisfaction rating, infectious disease provider follow-up rate, and hospitalization cost. I appreciate the grant support from SHM, and am looking forward to working with Dr. Huntington and other providers at DHMC, as well as developing myself professionally.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the United States or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

It is not surprising that my medical school – home to a group of passionate thought leaders in health service and policy research, including the Dartmouth Atlas and Accountable Care Organization – required all first-year medical students to take a course called “health care delivery science.”

The course offered me the first glimpse into quality improvement. However, because of a lack of clinical context, much of the course remained theoretical until my clinical years. During the hospital medicine rotation, I took care of a 40-year old patient who was newly diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer. It was challenging to deliver devastatingly bad news. The patient and family, however, were most confused and frustrated by the roles of different specialists and care providers, the purpose and scheduling of procedures, and diet arrangement. I wondered how I could make their experience better.

After several meetings with my mentor, Professor Jonathan Huntington, a hospitalist, MD-PhD researcher, and director of Care Coordination Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC), we identified a research area that has rising interest, importance, and relevance to the rural New Hampshire population. It is about identifying a clinical pathway for injection drug–related infectious sequelae.

Because of the unique bio-socio-psycho needs of injection drug users, hospitalizations due to injection-related infection sequelae often contribute to increased length of stay, readmission rates, and expenses out of state and federal health care funding. Prolonged stays also result in the waste of tertiary care resources for nontertiary needs, underutilization of regional care resources such as community and critical access hospitals, and increased care burden, as most patients travel long distances to obtain care.

We will pilot and implement a clinical pathway in the medicine units and measure length of stay, readmission rate, patient satisfaction rating, infectious disease provider follow-up rate, and hospitalization cost. I appreciate the grant support from SHM, and am looking forward to working with Dr. Huntington and other providers at DHMC, as well as developing myself professionally.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the United States or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

It is not surprising that my medical school – home to a group of passionate thought leaders in health service and policy research, including the Dartmouth Atlas and Accountable Care Organization – required all first-year medical students to take a course called “health care delivery science.”

The course offered me the first glimpse into quality improvement. However, because of a lack of clinical context, much of the course remained theoretical until my clinical years. During the hospital medicine rotation, I took care of a 40-year old patient who was newly diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer. It was challenging to deliver devastatingly bad news. The patient and family, however, were most confused and frustrated by the roles of different specialists and care providers, the purpose and scheduling of procedures, and diet arrangement. I wondered how I could make their experience better.

After several meetings with my mentor, Professor Jonathan Huntington, a hospitalist, MD-PhD researcher, and director of Care Coordination Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC), we identified a research area that has rising interest, importance, and relevance to the rural New Hampshire population. It is about identifying a clinical pathway for injection drug–related infectious sequelae.

Because of the unique bio-socio-psycho needs of injection drug users, hospitalizations due to injection-related infection sequelae often contribute to increased length of stay, readmission rates, and expenses out of state and federal health care funding. Prolonged stays also result in the waste of tertiary care resources for nontertiary needs, underutilization of regional care resources such as community and critical access hospitals, and increased care burden, as most patients travel long distances to obtain care.

We will pilot and implement a clinical pathway in the medicine units and measure length of stay, readmission rate, patient satisfaction rating, infectious disease provider follow-up rate, and hospitalization cost. I appreciate the grant support from SHM, and am looking forward to working with Dr. Huntington and other providers at DHMC, as well as developing myself professionally.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the United States or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

CHEST 2017 Keynote Speaker

John O’Leary is a father of four, business owner, speaker, writer, and former hospital chaplain—a fortunate guy. But he attributes the best of everything he has to an unfortunate event that happened back in 1987.

At the age of 9, O’Leary was involved in a house fire that left burns on 100% of his body, 87% of which were third degree. Doctors gave O’Leary less than a 1% chance to live, odds that were overwhelming—but not entirely impossible to beat.

Despite what the health-care professionals told his mother, when O’Leary asked her if he was going to die, she responded by asking her son if he wanted to die or if he wanted to live: a question that O’Leary says must have taken lot more courage for a mother to ask than it did for a 9-year-old to answer.

Although he was taken aback, the answer seemed obvious to O’Leary. Of course he wanted to live. And live he did, but only after 5 months in the hospital and the amputation of all of his fingers.

After he returned to school 18 months later with his classmates welcoming him back with a parade, O’Leary didn’t see the necessity in sharing his story. “I always knew my story, I just never truly embraced it.”

O’Leary’s father told him that he wanted to thank the community members who truly helped their family through the tough times and that he planned to do so by writing a book. With the help of O’Leary’s mother, 100 copies of Overwhelming Odds were originally printed and given to members of the community. Today, over 70,000 copies of their book have been sold.

When some Girl Scouts approached O’Leary and asked him to share his story with their troop and their parents, his life changed. O’Leary says that he now tries to say yes to each person/organization that asks him to share. As a result, he has said yes over 1,500 times and has even made a life of it.

“We confuse being out of bed with being awake, being at work with being fully engaged, or being with a patient with being actively present for and with that patient,” O’Leary says of accidental living. “That’s not really awake; that’s not alive. It’s more of sleepwalking through life.”

O’Leary believes that too often we give away the freedom of life to things that are out of our control and that he feels it is his job to remind his listeners that there are a lot of things in our control on which we should be fully living. “We want people to realize they have the ability to be actively present in every engagement and every decision, every thought, and every word, and ultimately, every result in their lives.”

CHEST Annual Meeting 2017 is one of the events that O’Leary has recently said “yes” to, and he is very excited about it. “As things continue to change…we can forget why we got into what we got into,” O’Leary says. “I am excited to remind everyone at CHEST about the profoundly beautiful nature of their work and how it has the ability to affect both the staff and patients.”

Members of O’Leary’s medical team, as well as other hospital staff members, were crucial to his survival and improved health. One of his doctors was not only a respected physician and surgeon but also a powerful leader who was capable of reminding every member of the hospital of their purpose and necessity to a patient’s life, something that O’Leary hopes can be common in every health-care team.

“When you have the chance to influence men and women who serve patients and teams and impact lives and do it generationally—I think we forget that it is a generational ripple effect; my kids are where and who they are today because doctors, nurses, practitioners, and janitors showed up 30 years ago.”

John O’Leary is a father of four, business owner, speaker, writer, and former hospital chaplain—a fortunate guy. But he attributes the best of everything he has to an unfortunate event that happened back in 1987.

At the age of 9, O’Leary was involved in a house fire that left burns on 100% of his body, 87% of which were third degree. Doctors gave O’Leary less than a 1% chance to live, odds that were overwhelming—but not entirely impossible to beat.

Despite what the health-care professionals told his mother, when O’Leary asked her if he was going to die, she responded by asking her son if he wanted to die or if he wanted to live: a question that O’Leary says must have taken lot more courage for a mother to ask than it did for a 9-year-old to answer.

Although he was taken aback, the answer seemed obvious to O’Leary. Of course he wanted to live. And live he did, but only after 5 months in the hospital and the amputation of all of his fingers.

After he returned to school 18 months later with his classmates welcoming him back with a parade, O’Leary didn’t see the necessity in sharing his story. “I always knew my story, I just never truly embraced it.”

O’Leary’s father told him that he wanted to thank the community members who truly helped their family through the tough times and that he planned to do so by writing a book. With the help of O’Leary’s mother, 100 copies of Overwhelming Odds were originally printed and given to members of the community. Today, over 70,000 copies of their book have been sold.

When some Girl Scouts approached O’Leary and asked him to share his story with their troop and their parents, his life changed. O’Leary says that he now tries to say yes to each person/organization that asks him to share. As a result, he has said yes over 1,500 times and has even made a life of it.

“We confuse being out of bed with being awake, being at work with being fully engaged, or being with a patient with being actively present for and with that patient,” O’Leary says of accidental living. “That’s not really awake; that’s not alive. It’s more of sleepwalking through life.”

O’Leary believes that too often we give away the freedom of life to things that are out of our control and that he feels it is his job to remind his listeners that there are a lot of things in our control on which we should be fully living. “We want people to realize they have the ability to be actively present in every engagement and every decision, every thought, and every word, and ultimately, every result in their lives.”

CHEST Annual Meeting 2017 is one of the events that O’Leary has recently said “yes” to, and he is very excited about it. “As things continue to change…we can forget why we got into what we got into,” O’Leary says. “I am excited to remind everyone at CHEST about the profoundly beautiful nature of their work and how it has the ability to affect both the staff and patients.”

Members of O’Leary’s medical team, as well as other hospital staff members, were crucial to his survival and improved health. One of his doctors was not only a respected physician and surgeon but also a powerful leader who was capable of reminding every member of the hospital of their purpose and necessity to a patient’s life, something that O’Leary hopes can be common in every health-care team.

“When you have the chance to influence men and women who serve patients and teams and impact lives and do it generationally—I think we forget that it is a generational ripple effect; my kids are where and who they are today because doctors, nurses, practitioners, and janitors showed up 30 years ago.”

John O’Leary is a father of four, business owner, speaker, writer, and former hospital chaplain—a fortunate guy. But he attributes the best of everything he has to an unfortunate event that happened back in 1987.

At the age of 9, O’Leary was involved in a house fire that left burns on 100% of his body, 87% of which were third degree. Doctors gave O’Leary less than a 1% chance to live, odds that were overwhelming—but not entirely impossible to beat.

Despite what the health-care professionals told his mother, when O’Leary asked her if he was going to die, she responded by asking her son if he wanted to die or if he wanted to live: a question that O’Leary says must have taken lot more courage for a mother to ask than it did for a 9-year-old to answer.

Although he was taken aback, the answer seemed obvious to O’Leary. Of course he wanted to live. And live he did, but only after 5 months in the hospital and the amputation of all of his fingers.

After he returned to school 18 months later with his classmates welcoming him back with a parade, O’Leary didn’t see the necessity in sharing his story. “I always knew my story, I just never truly embraced it.”

O’Leary’s father told him that he wanted to thank the community members who truly helped their family through the tough times and that he planned to do so by writing a book. With the help of O’Leary’s mother, 100 copies of Overwhelming Odds were originally printed and given to members of the community. Today, over 70,000 copies of their book have been sold.

When some Girl Scouts approached O’Leary and asked him to share his story with their troop and their parents, his life changed. O’Leary says that he now tries to say yes to each person/organization that asks him to share. As a result, he has said yes over 1,500 times and has even made a life of it.

“We confuse being out of bed with being awake, being at work with being fully engaged, or being with a patient with being actively present for and with that patient,” O’Leary says of accidental living. “That’s not really awake; that’s not alive. It’s more of sleepwalking through life.”

O’Leary believes that too often we give away the freedom of life to things that are out of our control and that he feels it is his job to remind his listeners that there are a lot of things in our control on which we should be fully living. “We want people to realize they have the ability to be actively present in every engagement and every decision, every thought, and every word, and ultimately, every result in their lives.”

CHEST Annual Meeting 2017 is one of the events that O’Leary has recently said “yes” to, and he is very excited about it. “As things continue to change…we can forget why we got into what we got into,” O’Leary says. “I am excited to remind everyone at CHEST about the profoundly beautiful nature of their work and how it has the ability to affect both the staff and patients.”

Members of O’Leary’s medical team, as well as other hospital staff members, were crucial to his survival and improved health. One of his doctors was not only a respected physician and surgeon but also a powerful leader who was capable of reminding every member of the hospital of their purpose and necessity to a patient’s life, something that O’Leary hopes can be common in every health-care team.

“When you have the chance to influence men and women who serve patients and teams and impact lives and do it generationally—I think we forget that it is a generational ripple effect; my kids are where and who they are today because doctors, nurses, practitioners, and janitors showed up 30 years ago.”

NAMDRC Update

The old adage of not wanting to see how laws or sausage is made holds true today, perhaps more so than ever. But certain clinical realities within pulmonary medicine virtually ensure that legislation is actually part of any reasonable solution.

NAMDRC has initiated an outreach to all the key medical, allied health, and patient societies that focus on pulmonary medicine to determine if consensus can be reached on a focused laundry list of issues that, for varying reasons, lean toward Congress for legislative solutions.

Here is a list of some of the issues under discussion:

• Home mechanical ventilation. Under current law, “ventilators” are covered items under the durable medical equipment benefit. In the 1990s, in order to circumvent statutory requirements that ventilators be paid under a “frequent and substantial servicing” payment methodology, HCFA (now CMS) created a new category – respiratory assist devices and declared that these devices, despite classification by FDA as ventilators, are not ventilators in reality, and the payment methodology, therefore, does not apply.

Over the past several years, the pulmonary medicine community tried its best to convince CMS that its rules were problematic, archaic, and costing the Medicare program tens of millions of dollars in unnecessary expenditures. A formal submission to CMS, a request for a National Coverage Determination reconsideration, was denied with a phrase now echoed throughout health care, “it’s complicated.” The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• High flow oxygen therapy for ILD patients. Oxygen remains the largest single component of the durable medical equipment benefit and, largely due to competitive bidding, has seen payment drop dramatically since the implementation of competitive bidding.

One can easily argue that competitive pricing is self-inflicted by the DME industry as the rates are set through a complicated formula based on bids from suppliers. But the impact has been particularly hard on liquid systems, the delivery system choice of not only many Medicare beneficiaries but also is the modality of choice for patients with clear need for high flow oxygen. While delivery in the home for high flow needs can be met by some stationary concentrators, the virtual disappearance of liquid systems, attributable to pricing triggered by competitive bidding, results in many ILD patients unable to leave their homes. The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• Section 603. This provision of the Balanced Budget Act of 2015 was designed to inhibit hospital purchases of certain physician practices that were based on aberrations within the Medicare payment system that rewarded hospitals significantly more than the same service provided in a physician office. For example, a physician office-based sleep lab may be able to bill Medicare for a particular service, but if the hospital purchases that physician practice and bills for the same service, it might receive upwards of twice as much payment.

While all involved seem to agree that this provision was not intended to target pulmonary rehabilitation services, it is being hit particularly hard by CMS rules implementing the statute. Any new pulmonary rehab program that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus must bill at the physician fee schedule rate, a rate about half of the hospital outpatient rate. Furthermore, existing programs that choose to expand must do so within the confines of their specific current location, unable to move a floor away. Doing so would trigger the reduced payment methodology.

[[{"fid":"197721","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]

CMS agrees this is clearly an example of unintended consequences, but CMS also acknowledges it does not have the authority to remedy the situation. The agency itself signaled the only way to exempt pulmonary rehabilitation services is to seek Congressional action.

And now to the “sausage” part of the equation. Congressional action on virtually anything except renaming a post office becomes a political, as well as substantive, challenge. Here are just some of the considerations that must be addressed by any legislative strategy.

1. Any “fix” must be clinically sound and supported across a broad cross section of physician and patient groups. And the fix must give some level of flexibility to CMS to implement it in a reasonable way but tie their hands to force changes in policy.