User login

Inaugural ACS Quality and Safety Conference: Achieving quality across the continuum of care

Approximately 1,900 individuals who contribute to hospital quality improvement (QI) programs attended the inaugural American College of Surgeons (ACS) Quality and Safety Conference, July 21−24 at the New York Hilton Midtown, NY. The rapid growth of ACS Quality Programs in recent years prompted the expansion of the College’s Annual National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Conference to include a more comprehensive look at not only ACS NSQIP Adult and Pediatric, but also the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP®), the Children’s Surgery Verification (CSV) Quality Improvement Program, and the Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR).

In addition to providing details about the work of the aforementioned ACS Quality Programs, the conference also covered included discussion of the new ACS quality manual, the reconstructed SSR, and programs for improving surgical recovery and outcomes for geriatric surgery patients. The quality manual, Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety, was provided to all conference attendees and is intended to serve as a resource for surgical leaders seeking to improve patient care in their institutions, departments, and practices.

David B. Hoyt, ACS Executive Director, spoke about the SSR, explaining how it will be part of of the “registry of the future,” allowing users to eventually incorporate relevant data across individual ACS Quality Programs. Also discussed were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Safety Program for Improving Surgical Care and Recovery and the Coalition for Quality in Geriatric Surgery, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation—programs that seek to set standards and improve outcomes in surgical patients.

The Keynote Address was provided by Blake Haxton, JD, who lost both of his legs to necrotizing fasciitis. Mr. Haxton described his journey from going to the local hospital’s emergency department with debilitating swelling and redness in his right leg to reclaiming his identity, and how he learned that “essential worth is intrinsic and unearned.”

Speakers at the conference addressed a number of hot issues in health care, including health policy, opioid abuse, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and disparities in care.

A topic of considerable interest was how important culture change is for any sustained QI effort. For any QI effort to succeed it has to evolve in a culture that accepts change, acknowledges shortcomings, uses data to find strengths and weaknesses, and demonstrates resilience. Two cultural changes that surgical teams have experienced in recent years include a greater emphasis on process improvement and checklists.

To read a more detailed account of the topics covered at the conference, read the October Bulletin at URL TO COME. The 2018 ACS Quality and Safety Conference will be held July 21–24 in Orlando, FL.

Approximately 1,900 individuals who contribute to hospital quality improvement (QI) programs attended the inaugural American College of Surgeons (ACS) Quality and Safety Conference, July 21−24 at the New York Hilton Midtown, NY. The rapid growth of ACS Quality Programs in recent years prompted the expansion of the College’s Annual National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Conference to include a more comprehensive look at not only ACS NSQIP Adult and Pediatric, but also the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP®), the Children’s Surgery Verification (CSV) Quality Improvement Program, and the Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR).

In addition to providing details about the work of the aforementioned ACS Quality Programs, the conference also covered included discussion of the new ACS quality manual, the reconstructed SSR, and programs for improving surgical recovery and outcomes for geriatric surgery patients. The quality manual, Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety, was provided to all conference attendees and is intended to serve as a resource for surgical leaders seeking to improve patient care in their institutions, departments, and practices.

David B. Hoyt, ACS Executive Director, spoke about the SSR, explaining how it will be part of of the “registry of the future,” allowing users to eventually incorporate relevant data across individual ACS Quality Programs. Also discussed were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Safety Program for Improving Surgical Care and Recovery and the Coalition for Quality in Geriatric Surgery, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation—programs that seek to set standards and improve outcomes in surgical patients.

The Keynote Address was provided by Blake Haxton, JD, who lost both of his legs to necrotizing fasciitis. Mr. Haxton described his journey from going to the local hospital’s emergency department with debilitating swelling and redness in his right leg to reclaiming his identity, and how he learned that “essential worth is intrinsic and unearned.”

Speakers at the conference addressed a number of hot issues in health care, including health policy, opioid abuse, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and disparities in care.

A topic of considerable interest was how important culture change is for any sustained QI effort. For any QI effort to succeed it has to evolve in a culture that accepts change, acknowledges shortcomings, uses data to find strengths and weaknesses, and demonstrates resilience. Two cultural changes that surgical teams have experienced in recent years include a greater emphasis on process improvement and checklists.

To read a more detailed account of the topics covered at the conference, read the October Bulletin at URL TO COME. The 2018 ACS Quality and Safety Conference will be held July 21–24 in Orlando, FL.

Approximately 1,900 individuals who contribute to hospital quality improvement (QI) programs attended the inaugural American College of Surgeons (ACS) Quality and Safety Conference, July 21−24 at the New York Hilton Midtown, NY. The rapid growth of ACS Quality Programs in recent years prompted the expansion of the College’s Annual National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Conference to include a more comprehensive look at not only ACS NSQIP Adult and Pediatric, but also the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP®), the Children’s Surgery Verification (CSV) Quality Improvement Program, and the Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR).

In addition to providing details about the work of the aforementioned ACS Quality Programs, the conference also covered included discussion of the new ACS quality manual, the reconstructed SSR, and programs for improving surgical recovery and outcomes for geriatric surgery patients. The quality manual, Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety, was provided to all conference attendees and is intended to serve as a resource for surgical leaders seeking to improve patient care in their institutions, departments, and practices.

David B. Hoyt, ACS Executive Director, spoke about the SSR, explaining how it will be part of of the “registry of the future,” allowing users to eventually incorporate relevant data across individual ACS Quality Programs. Also discussed were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Safety Program for Improving Surgical Care and Recovery and the Coalition for Quality in Geriatric Surgery, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation—programs that seek to set standards and improve outcomes in surgical patients.

The Keynote Address was provided by Blake Haxton, JD, who lost both of his legs to necrotizing fasciitis. Mr. Haxton described his journey from going to the local hospital’s emergency department with debilitating swelling and redness in his right leg to reclaiming his identity, and how he learned that “essential worth is intrinsic and unearned.”

Speakers at the conference addressed a number of hot issues in health care, including health policy, opioid abuse, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and disparities in care.

A topic of considerable interest was how important culture change is for any sustained QI effort. For any QI effort to succeed it has to evolve in a culture that accepts change, acknowledges shortcomings, uses data to find strengths and weaknesses, and demonstrates resilience. Two cultural changes that surgical teams have experienced in recent years include a greater emphasis on process improvement and checklists.

To read a more detailed account of the topics covered at the conference, read the October Bulletin at URL TO COME. The 2018 ACS Quality and Safety Conference will be held July 21–24 in Orlando, FL.

Apply for three ACS scholarships by November

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is offering the following three scholarships for 2018 and 2019., each with a November due date.

2018 Faculty Research Fellowships

The American College of Surgeons is offering two-year faculty research fellowships, through the generosity of Fellows, Chapters, and friends of the College, to surgeons entering academic careers in surgery or a surgical specialty. The fellowship is to assist a surgeon in establishing their research program under mentorship, with the goal of transitioning to becoming an independent investigator. Applicants should have demonstrated their potential to work as independent investigators. The fellowship award is $40,000 per year for each of two years, to support the research.

Applications are due by November 1, 2017, and decisions will be made in February 2018.Read the applications requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/research/acsfaculty. Contact the Scholarships Administrator at scholarships@facs.org with questions.

ACS/ASBrS International Scholarship 2018

The ACS and the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) is offering this scholarship, which will be awarded to surgeons specifically working in countries other than the U.S. and Canada to improve the quality of breast cancer surgical services. Preference will be given to applicants from developing nations. The scholarship, in the amount of $5,000, provides the scholar with an opportunity to attend the annual meeting of the ASBrS and to visit the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers headquarters in Chicago, IL, to learn about the standards for a breast cancer program/database and the importance of multidisciplinary breast cancer care. The awardee will receive gratis registration to the annual meeting of the ASBrS and to one available postgraduate course at the meeting. Assistance will be provided to obtain preferential housing in an economical hotel in the ASBrS meeting city. Hotel and travel expenses will be the responsibility of the awardee, to be funded from the scholarship award.

Applications are due by November 15, 2017. All applicants will be notified of the selection committee’s decision in January 2018. Read the application requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/international/acsasbrs-intl. Contact the International Liaison at kearly@facs.org with questions.

2019 Traveling Fellowships

The International Relations Committee of the ACS announces the availability of a traveling fellowship in the amount of $10,000 each to Australia and New Zealand (ANZ), one to Germany, and one to Japan. They are intended to encourage international exchange of information concerning surgical science, practice, and education and to establish professional and academic collaborations and friendships. The Traveling Fellows are required to spend a minimum of two to three weeks in the country that they visit. The dates and locations are as follows:

Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, Bangkok, Thailand (May 6–10, 2019)

Germany Society of Surgery, Munich (March 26–29, 2019)

Japan Surgical Society, Osaka (April 18–20, 2019)

The closing date for receipt of completed applications for all three destinations is November 15, 2017. Applicants will be notified by March 2018. Read the application requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/traveling. Contact the International Liaison at kearly@facs.org with any questions.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is offering the following three scholarships for 2018 and 2019., each with a November due date.

2018 Faculty Research Fellowships

The American College of Surgeons is offering two-year faculty research fellowships, through the generosity of Fellows, Chapters, and friends of the College, to surgeons entering academic careers in surgery or a surgical specialty. The fellowship is to assist a surgeon in establishing their research program under mentorship, with the goal of transitioning to becoming an independent investigator. Applicants should have demonstrated their potential to work as independent investigators. The fellowship award is $40,000 per year for each of two years, to support the research.

Applications are due by November 1, 2017, and decisions will be made in February 2018.Read the applications requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/research/acsfaculty. Contact the Scholarships Administrator at scholarships@facs.org with questions.

ACS/ASBrS International Scholarship 2018

The ACS and the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) is offering this scholarship, which will be awarded to surgeons specifically working in countries other than the U.S. and Canada to improve the quality of breast cancer surgical services. Preference will be given to applicants from developing nations. The scholarship, in the amount of $5,000, provides the scholar with an opportunity to attend the annual meeting of the ASBrS and to visit the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers headquarters in Chicago, IL, to learn about the standards for a breast cancer program/database and the importance of multidisciplinary breast cancer care. The awardee will receive gratis registration to the annual meeting of the ASBrS and to one available postgraduate course at the meeting. Assistance will be provided to obtain preferential housing in an economical hotel in the ASBrS meeting city. Hotel and travel expenses will be the responsibility of the awardee, to be funded from the scholarship award.

Applications are due by November 15, 2017. All applicants will be notified of the selection committee’s decision in January 2018. Read the application requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/international/acsasbrs-intl. Contact the International Liaison at kearly@facs.org with questions.

2019 Traveling Fellowships

The International Relations Committee of the ACS announces the availability of a traveling fellowship in the amount of $10,000 each to Australia and New Zealand (ANZ), one to Germany, and one to Japan. They are intended to encourage international exchange of information concerning surgical science, practice, and education and to establish professional and academic collaborations and friendships. The Traveling Fellows are required to spend a minimum of two to three weeks in the country that they visit. The dates and locations are as follows:

Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, Bangkok, Thailand (May 6–10, 2019)

Germany Society of Surgery, Munich (March 26–29, 2019)

Japan Surgical Society, Osaka (April 18–20, 2019)

The closing date for receipt of completed applications for all three destinations is November 15, 2017. Applicants will be notified by March 2018. Read the application requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/traveling. Contact the International Liaison at kearly@facs.org with any questions.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is offering the following three scholarships for 2018 and 2019., each with a November due date.

2018 Faculty Research Fellowships

The American College of Surgeons is offering two-year faculty research fellowships, through the generosity of Fellows, Chapters, and friends of the College, to surgeons entering academic careers in surgery or a surgical specialty. The fellowship is to assist a surgeon in establishing their research program under mentorship, with the goal of transitioning to becoming an independent investigator. Applicants should have demonstrated their potential to work as independent investigators. The fellowship award is $40,000 per year for each of two years, to support the research.

Applications are due by November 1, 2017, and decisions will be made in February 2018.Read the applications requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/research/acsfaculty. Contact the Scholarships Administrator at scholarships@facs.org with questions.

ACS/ASBrS International Scholarship 2018

The ACS and the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) is offering this scholarship, which will be awarded to surgeons specifically working in countries other than the U.S. and Canada to improve the quality of breast cancer surgical services. Preference will be given to applicants from developing nations. The scholarship, in the amount of $5,000, provides the scholar with an opportunity to attend the annual meeting of the ASBrS and to visit the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers headquarters in Chicago, IL, to learn about the standards for a breast cancer program/database and the importance of multidisciplinary breast cancer care. The awardee will receive gratis registration to the annual meeting of the ASBrS and to one available postgraduate course at the meeting. Assistance will be provided to obtain preferential housing in an economical hotel in the ASBrS meeting city. Hotel and travel expenses will be the responsibility of the awardee, to be funded from the scholarship award.

Applications are due by November 15, 2017. All applicants will be notified of the selection committee’s decision in January 2018. Read the application requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/international/acsasbrs-intl. Contact the International Liaison at kearly@facs.org with questions.

2019 Traveling Fellowships

The International Relations Committee of the ACS announces the availability of a traveling fellowship in the amount of $10,000 each to Australia and New Zealand (ANZ), one to Germany, and one to Japan. They are intended to encourage international exchange of information concerning surgical science, practice, and education and to establish professional and academic collaborations and friendships. The Traveling Fellows are required to spend a minimum of two to three weeks in the country that they visit. The dates and locations are as follows:

Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, Bangkok, Thailand (May 6–10, 2019)

Germany Society of Surgery, Munich (March 26–29, 2019)

Japan Surgical Society, Osaka (April 18–20, 2019)

The closing date for receipt of completed applications for all three destinations is November 15, 2017. Applicants will be notified by March 2018. Read the application requirements and apply at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/traveling. Contact the International Liaison at kearly@facs.org with any questions.

Visit ACS Central during Clinical Congress

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2017 experience by visiting the new ACS Central area designed specifically for our members. ACS Central visitors will have opportunities to meet College staff; learn about the latest ACS programs, products, and services; purchase ACS materials; and make ACS Central a convenient gathering space during the meeting. While there, you can also update your member profile and receive a flash drive with your own professional photo to keep.

ACS Central also will house the ACS Theatre, which will feature presentations on the following new ACS programs and products during lunch hours Monday through Wednesday:

• Monday: The Surgeon Specific Registry

• Tuesday: Improving Surgical Care and Recovery (ISCR)

• Wednesday: Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety (the “red book”)

The ACS Theatre also will be used for meet-and-greets with ACS leaders. Posters outlining the schedule for the day will be located throughout ACS Central, and alerts will be sent out through the app and social media.

ACS Central will be open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday through Wednesday in the San Diego Convention Center, Exhibit Hall.

The following select ACS Programs also will have a presence Sunday through Thursday in the main lobby of the San Diego Convention Center and in the Registration Area:

• ACS Foundation and Fellows Leadership Society

• American College of Surgeons Professional Association-SurgeonsPAC

• Mobile Connect

• Become a Member/Member Services booth, where you can join the ACS, pay your membership dues, or get answers to questions about your membership

In addition, MyCME and Webcast Sales Booths will be located throughout the Convention Center and open the same hours as registration Monday through Thursday. To view other conference resources, go to the Clinical Congress 2017 Resources web page at facs.org/clincon2017/resources .

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2017 experience by visiting the new ACS Central area designed specifically for our members. ACS Central visitors will have opportunities to meet College staff; learn about the latest ACS programs, products, and services; purchase ACS materials; and make ACS Central a convenient gathering space during the meeting. While there, you can also update your member profile and receive a flash drive with your own professional photo to keep.

ACS Central also will house the ACS Theatre, which will feature presentations on the following new ACS programs and products during lunch hours Monday through Wednesday:

• Monday: The Surgeon Specific Registry

• Tuesday: Improving Surgical Care and Recovery (ISCR)

• Wednesday: Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety (the “red book”)

The ACS Theatre also will be used for meet-and-greets with ACS leaders. Posters outlining the schedule for the day will be located throughout ACS Central, and alerts will be sent out through the app and social media.

ACS Central will be open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday through Wednesday in the San Diego Convention Center, Exhibit Hall.

The following select ACS Programs also will have a presence Sunday through Thursday in the main lobby of the San Diego Convention Center and in the Registration Area:

• ACS Foundation and Fellows Leadership Society

• American College of Surgeons Professional Association-SurgeonsPAC

• Mobile Connect

• Become a Member/Member Services booth, where you can join the ACS, pay your membership dues, or get answers to questions about your membership

In addition, MyCME and Webcast Sales Booths will be located throughout the Convention Center and open the same hours as registration Monday through Thursday. To view other conference resources, go to the Clinical Congress 2017 Resources web page at facs.org/clincon2017/resources .

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2017 experience by visiting the new ACS Central area designed specifically for our members. ACS Central visitors will have opportunities to meet College staff; learn about the latest ACS programs, products, and services; purchase ACS materials; and make ACS Central a convenient gathering space during the meeting. While there, you can also update your member profile and receive a flash drive with your own professional photo to keep.

ACS Central also will house the ACS Theatre, which will feature presentations on the following new ACS programs and products during lunch hours Monday through Wednesday:

• Monday: The Surgeon Specific Registry

• Tuesday: Improving Surgical Care and Recovery (ISCR)

• Wednesday: Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety (the “red book”)

The ACS Theatre also will be used for meet-and-greets with ACS leaders. Posters outlining the schedule for the day will be located throughout ACS Central, and alerts will be sent out through the app and social media.

ACS Central will be open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday through Wednesday in the San Diego Convention Center, Exhibit Hall.

The following select ACS Programs also will have a presence Sunday through Thursday in the main lobby of the San Diego Convention Center and in the Registration Area:

• ACS Foundation and Fellows Leadership Society

• American College of Surgeons Professional Association-SurgeonsPAC

• Mobile Connect

• Become a Member/Member Services booth, where you can join the ACS, pay your membership dues, or get answers to questions about your membership

In addition, MyCME and Webcast Sales Booths will be located throughout the Convention Center and open the same hours as registration Monday through Thursday. To view other conference resources, go to the Clinical Congress 2017 Resources web page at facs.org/clincon2017/resources .

ACS scores victory for trauma research

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has been working with members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations to advocate for inclusion of trauma research language in the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (Labor-HHS) Appropriations Bill for fiscal year 2018. More specifically, the ACS is requesting that the committee report language stress the importance of trauma research and encourage the National Institutes of Health to establish a trauma research agenda to minimize death, disability, and injury by ensuring that patient-specific trauma care is based on scientifically validated findings. Committee report language is included in appropriations legislation to guide the administration and departments in their support of the committee’s priorities. The report and bill await further action in the Senate. The bill contains base discretionary funding for the agencies.

For more information about the College’s policy positions on trauma, contact Justin Rosen, ACS Congressional Lobbyist, at jrosen@facs.org or 202-672-1528.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has been working with members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations to advocate for inclusion of trauma research language in the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (Labor-HHS) Appropriations Bill for fiscal year 2018. More specifically, the ACS is requesting that the committee report language stress the importance of trauma research and encourage the National Institutes of Health to establish a trauma research agenda to minimize death, disability, and injury by ensuring that patient-specific trauma care is based on scientifically validated findings. Committee report language is included in appropriations legislation to guide the administration and departments in their support of the committee’s priorities. The report and bill await further action in the Senate. The bill contains base discretionary funding for the agencies.

For more information about the College’s policy positions on trauma, contact Justin Rosen, ACS Congressional Lobbyist, at jrosen@facs.org or 202-672-1528.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has been working with members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations to advocate for inclusion of trauma research language in the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (Labor-HHS) Appropriations Bill for fiscal year 2018. More specifically, the ACS is requesting that the committee report language stress the importance of trauma research and encourage the National Institutes of Health to establish a trauma research agenda to minimize death, disability, and injury by ensuring that patient-specific trauma care is based on scientifically validated findings. Committee report language is included in appropriations legislation to guide the administration and departments in their support of the committee’s priorities. The report and bill await further action in the Senate. The bill contains base discretionary funding for the agencies.

For more information about the College’s policy positions on trauma, contact Justin Rosen, ACS Congressional Lobbyist, at jrosen@facs.org or 202-672-1528.

The right choice? Surgery “offered” or “recommended”?

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

From the Editors: Halsted, Holmes, and penguins

Is it not ironic that in a profession that is always seeking answers – What does this patient have? Is that mass malignant? What’s the best way to make a diagnosis? – too much information has become a major problem?

Unlike William Stewart Halsted or Theodor Billroth, who blazed surgical trails in an age when much was unknown, today’s surgeons face a jungle of information obscuring the trail ahead. Every morning we wake up to another 30 or 40 unread emails. Journals multiply on our desks. The books we need to read pile up and spill over onto our desks, bookshelves, and side tables. Sometimes, it makes one long for the old days when definitive answers might not be found in the literature. These days, we know it is likely that someone has published exactly what we need at any particular moment, and yet finding it in the jungle of information can be a great challenge.

Another outcome of too much information is the accumulation in our brains of unsorted bits of medical/surgical knowledge. Some of those bits are pearls, and others are just gum wrappers that take up space. It becomes an overwhelming task of ranking, sorting, prioritizing, and discarding.

A friend of mine years of ago called his brain an iceberg on which thousands of penguins stand. The penguins just kept coming and, finally, in order to learn anything new, he had to push some penguins off the iceberg. We have a lot of penguins on our icebergs these days.

This brings to mind many doctors’ favorite fictional character, Sherlock Holmes. That denizen of 221B Baker Street was a master at data management. He always had the right information available in his head relevant for the mystery at hand. How did he do it? Recall that Dr. Watson (a surgeon, I might add) was intermittently shocked by what Holmes didn’t know, to which the tobacco- and opiate-addicted hero would reply that he purposely forgot things that did not help him solve his cases.

And so, what is the modern surgeon – who must keep in the forefront of his or her mind every best practice, algorithm, and guideline – to do in this age of too much information? Like Holmes, we need to sort what is critical from what is not and let go of those items that no longer are germane. We then need to triage the vast amount of information delivered to us yearly, weekly, monthly, daily, hourly. The stream of little notes flashing at you from your black mirror (the screen of your mobile device) needs to be controlled lest it control you.

So, might I suggest a few strategies I have used to triage the flow of information? For hourly and daily information, I tend to ignore everything except ACS NewsScope and the ACS Communities items I find most interesting. For monthly information, I tend to use ACS Surgery News (plug intended) because it is “news” – the stuff that just happened in the meeting sphere or has not yet hit print (sorry, e-publication). The Journal of the American College of Surgeons is another monthly source that is reliable.

You may see a theme here. I’ve used the American College of Surgeons as my main filter. What gets through the editors of these outlets generally is viable and useful information. That’s what I need to know for right now. Such knowledge allows me to push those penguins no longer needed off my iceberg and greet the new ones with joy. We often wonder what the benefit of membership in the College may be. For me, these filters are worth the price of admission.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Is it not ironic that in a profession that is always seeking answers – What does this patient have? Is that mass malignant? What’s the best way to make a diagnosis? – too much information has become a major problem?

Unlike William Stewart Halsted or Theodor Billroth, who blazed surgical trails in an age when much was unknown, today’s surgeons face a jungle of information obscuring the trail ahead. Every morning we wake up to another 30 or 40 unread emails. Journals multiply on our desks. The books we need to read pile up and spill over onto our desks, bookshelves, and side tables. Sometimes, it makes one long for the old days when definitive answers might not be found in the literature. These days, we know it is likely that someone has published exactly what we need at any particular moment, and yet finding it in the jungle of information can be a great challenge.

Another outcome of too much information is the accumulation in our brains of unsorted bits of medical/surgical knowledge. Some of those bits are pearls, and others are just gum wrappers that take up space. It becomes an overwhelming task of ranking, sorting, prioritizing, and discarding.

A friend of mine years of ago called his brain an iceberg on which thousands of penguins stand. The penguins just kept coming and, finally, in order to learn anything new, he had to push some penguins off the iceberg. We have a lot of penguins on our icebergs these days.

This brings to mind many doctors’ favorite fictional character, Sherlock Holmes. That denizen of 221B Baker Street was a master at data management. He always had the right information available in his head relevant for the mystery at hand. How did he do it? Recall that Dr. Watson (a surgeon, I might add) was intermittently shocked by what Holmes didn’t know, to which the tobacco- and opiate-addicted hero would reply that he purposely forgot things that did not help him solve his cases.

And so, what is the modern surgeon – who must keep in the forefront of his or her mind every best practice, algorithm, and guideline – to do in this age of too much information? Like Holmes, we need to sort what is critical from what is not and let go of those items that no longer are germane. We then need to triage the vast amount of information delivered to us yearly, weekly, monthly, daily, hourly. The stream of little notes flashing at you from your black mirror (the screen of your mobile device) needs to be controlled lest it control you.

So, might I suggest a few strategies I have used to triage the flow of information? For hourly and daily information, I tend to ignore everything except ACS NewsScope and the ACS Communities items I find most interesting. For monthly information, I tend to use ACS Surgery News (plug intended) because it is “news” – the stuff that just happened in the meeting sphere or has not yet hit print (sorry, e-publication). The Journal of the American College of Surgeons is another monthly source that is reliable.

You may see a theme here. I’ve used the American College of Surgeons as my main filter. What gets through the editors of these outlets generally is viable and useful information. That’s what I need to know for right now. Such knowledge allows me to push those penguins no longer needed off my iceberg and greet the new ones with joy. We often wonder what the benefit of membership in the College may be. For me, these filters are worth the price of admission.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Is it not ironic that in a profession that is always seeking answers – What does this patient have? Is that mass malignant? What’s the best way to make a diagnosis? – too much information has become a major problem?

Unlike William Stewart Halsted or Theodor Billroth, who blazed surgical trails in an age when much was unknown, today’s surgeons face a jungle of information obscuring the trail ahead. Every morning we wake up to another 30 or 40 unread emails. Journals multiply on our desks. The books we need to read pile up and spill over onto our desks, bookshelves, and side tables. Sometimes, it makes one long for the old days when definitive answers might not be found in the literature. These days, we know it is likely that someone has published exactly what we need at any particular moment, and yet finding it in the jungle of information can be a great challenge.

Another outcome of too much information is the accumulation in our brains of unsorted bits of medical/surgical knowledge. Some of those bits are pearls, and others are just gum wrappers that take up space. It becomes an overwhelming task of ranking, sorting, prioritizing, and discarding.

A friend of mine years of ago called his brain an iceberg on which thousands of penguins stand. The penguins just kept coming and, finally, in order to learn anything new, he had to push some penguins off the iceberg. We have a lot of penguins on our icebergs these days.

This brings to mind many doctors’ favorite fictional character, Sherlock Holmes. That denizen of 221B Baker Street was a master at data management. He always had the right information available in his head relevant for the mystery at hand. How did he do it? Recall that Dr. Watson (a surgeon, I might add) was intermittently shocked by what Holmes didn’t know, to which the tobacco- and opiate-addicted hero would reply that he purposely forgot things that did not help him solve his cases.

And so, what is the modern surgeon – who must keep in the forefront of his or her mind every best practice, algorithm, and guideline – to do in this age of too much information? Like Holmes, we need to sort what is critical from what is not and let go of those items that no longer are germane. We then need to triage the vast amount of information delivered to us yearly, weekly, monthly, daily, hourly. The stream of little notes flashing at you from your black mirror (the screen of your mobile device) needs to be controlled lest it control you.

So, might I suggest a few strategies I have used to triage the flow of information? For hourly and daily information, I tend to ignore everything except ACS NewsScope and the ACS Communities items I find most interesting. For monthly information, I tend to use ACS Surgery News (plug intended) because it is “news” – the stuff that just happened in the meeting sphere or has not yet hit print (sorry, e-publication). The Journal of the American College of Surgeons is another monthly source that is reliable.

You may see a theme here. I’ve used the American College of Surgeons as my main filter. What gets through the editors of these outlets generally is viable and useful information. That’s what I need to know for right now. Such knowledge allows me to push those penguins no longer needed off my iceberg and greet the new ones with joy. We often wonder what the benefit of membership in the College may be. For me, these filters are worth the price of admission.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

VIDEO: Sildenafil improves cerebrovascular reactivity in chronic TBI

SAN DIEGO – The healthy brain is a master of autoregulation, continuously adjusting blood flow to meet metabolic demand.

But in traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) breaks down; blood vessels don’t dilate as they should to deliver nutrients and oxygen, leading to progressive neurologic decline.

Sildenafil (Viagra) – a vasodilator in injured blood vessels – might help, according to ongoing research at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers there gave sildenafil to inpatients with persistent symptoms at least 6 months after traumatic brain injury and measured CVR by a novel MRI technique an hour later. “Sildenafil was able to correct the deficit in CVR in many cases. We are hopeful this could be a useful therapy,” said principal investigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, a professor of neurology at the university.

He explained the work in an interview at annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. The next step is to see if sildenafil helps CVR in acute traumatic brain injury, and in people who have had multiple, mild brain traumas, including professional athletes.

SAN DIEGO – The healthy brain is a master of autoregulation, continuously adjusting blood flow to meet metabolic demand.

But in traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) breaks down; blood vessels don’t dilate as they should to deliver nutrients and oxygen, leading to progressive neurologic decline.

Sildenafil (Viagra) – a vasodilator in injured blood vessels – might help, according to ongoing research at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers there gave sildenafil to inpatients with persistent symptoms at least 6 months after traumatic brain injury and measured CVR by a novel MRI technique an hour later. “Sildenafil was able to correct the deficit in CVR in many cases. We are hopeful this could be a useful therapy,” said principal investigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, a professor of neurology at the university.

He explained the work in an interview at annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. The next step is to see if sildenafil helps CVR in acute traumatic brain injury, and in people who have had multiple, mild brain traumas, including professional athletes.

SAN DIEGO – The healthy brain is a master of autoregulation, continuously adjusting blood flow to meet metabolic demand.

But in traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) breaks down; blood vessels don’t dilate as they should to deliver nutrients and oxygen, leading to progressive neurologic decline.

Sildenafil (Viagra) – a vasodilator in injured blood vessels – might help, according to ongoing research at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers there gave sildenafil to inpatients with persistent symptoms at least 6 months after traumatic brain injury and measured CVR by a novel MRI technique an hour later. “Sildenafil was able to correct the deficit in CVR in many cases. We are hopeful this could be a useful therapy,” said principal investigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, a professor of neurology at the university.

He explained the work in an interview at annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. The next step is to see if sildenafil helps CVR in acute traumatic brain injury, and in people who have had multiple, mild brain traumas, including professional athletes.

AT ANA 2017

SGLT inhibition back on track in phase 3 type T1DM trial

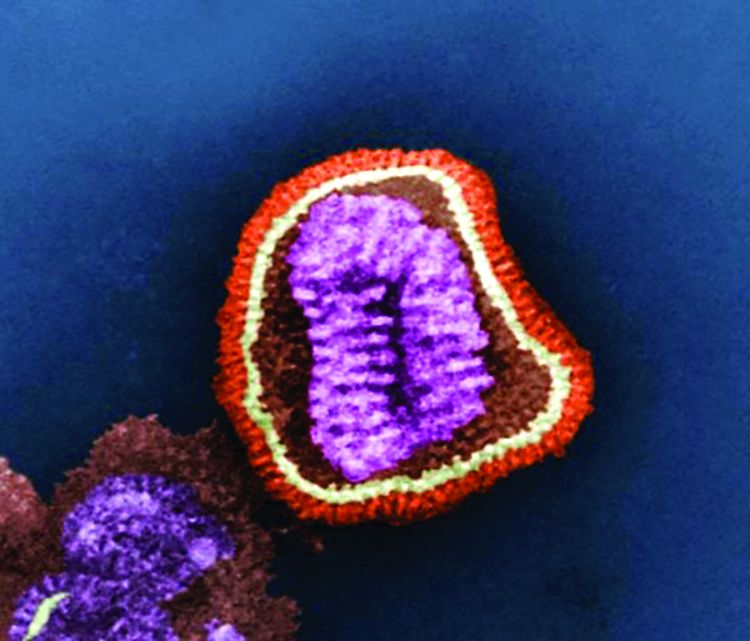

LISBON – Despite some earlier concerns over safety, sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT) inhibitors appear to be back on track for adjunctive use in people with type 1 diabetes (T1DM), according to phase 3 study findings presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Results of the DEPICT-1 study, showed improved glycemic control, greater weight loss, and no increased risk for either hypoglycemia or ketoacidosis in people treated with the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) versus those treated with placebo.

When researchers compared the two dapagliflozin doses with placebo, the mean difference in body weight from baseline to week 24 was –2.96% and –3.72% (both P less than .0001).

Rates of any hypoglycemia in the placebo, 5-mg dapagliflozin, and 10-mg dapagliflozin groups were a respective 79.6%, 79.4%, and 79.4%, and rates of severe hypoglycemia were 7.3%, 7.6%, and 6.4%.

Diabetic ketoacidosis occurred in a respective 1.2%, 1.4%, and 1.7% of patients treated with placebo, dapagliflozin 5 mg, and dapagliflozin 10 mg, respectively.

“Based on this 24-week study, dapagliflozin may be considered as a good candidate as an adjunct to insulin to improve glycemic control in type 1 diabetes,” said the lead investigator for the DEPICT-1 trial, Paresh Dandona, MD, PhD, at the EASD 2017 meeting.

“There may also be other potential long-term cardiovascular and renal benefits, which have recently been demonstrated in type 2 diabetes,” suggested Dr. Dandona, who is a distinguished professor of medicine and chief of the division of endocrinology at the State University of New York at Buffalo. “Of course, that’s an open question, which needs to be investigated and determined in future.”

DEPICT-1 is the first phase 3, randomized, blinded, clinical trial of a selective SGLT2 inhibitor in T1DM, the study’s investigators said in an early online publication (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[17]30308-X). The study was conducted at 143 sites in 17 centers and involved 833 people with T1DM who were not achieving optimal blood glucose control.

Adults with an HbA1c of 7.7% or higher who had been taking insulin for at least 12 months were recruited and underwent an 8-week lead-in period to optimize their diabetes management before being randomized to take placebo or dapagliflozin 5 mg or 10 mg for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was the change in HbA1c at Week 24.

DEPICT-1 “provides encouraging short-term data for the efficacy of adjunct SGLT2 inhibition in type 1 diabetes but might also provide insights into how the risk of ketoacidosis can be minimized,” John Petrie, MD, commented in an editorial that accompanied the published findings.

Dr. Petrie, professor of diabetic medicine at the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences at the University of Glasgow, observed, however, that the results needed to be considered in the context of similar, and also recently presented, findings from the inTandem3 trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708337) with the investigational dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor sotagliflozin. Other trials are expected to report soon with another SGLT2 inhibitor, empagliflozin.

In inTandem3, sotagliflozin helped more people who had T1DM and were on stable insulin to achieve an HbA1c level of 7% or lower at week 24 with no episodes of severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis, compared with those who took insulin alone (28.6% vs. 15.2%; P less than .001). However, the overall rates of ketoacidosis were higher in the patients treated with sotagliflozin than in those treated with placebo, at 3% versus 0.6%, respectively.

In both inTandem3 and DEPICT-1, strategies were in place to help carefully monitor and manage ketoacidosis. Dr. Petrie observed that patients in the latter trial were given a meter that measured both their blood glucose and ketones and were seen in a clinic regularly to assess the risk of ketoacidosis. These frequent visits, which occurred every 2 weeks, were shown to have an independent effect on HbA1c, he pointed out.

“Nevertheless, the investigators kept real-world clinical practice in mind by providing a very simple rule that insulin doses should be reduced by no more than 20% when study medication was started and that they should subsequently be titrated back towards the initial dose,” Dr. Petrie said. “This rule seemed to be quite effective in mitigating ketoacidosis and is feasible to implement in modern clinical practice since meters that measure ketones are increasingly available.

So does this mean a license for SGLT-targeting agents in T1DM could be coming soon? Not yet, Dr. Petrie suggests. “Regulators are likely to await at least the results of the 12-month follow-up, and data from other ongoing trials, before considering an indication for SGLT2 inhibitors in type 1 diabetes,” he said.

Adjunct treatment with these drugs also may require that individuals have “a good understanding of the early-warning symptoms of ketoacidosis” and be prepared to undertake regular home monitoring of both their blood glucose and ketones, as well as having a high level of communication with their diabetes health care providers.

AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb funded the study.

Dr. Dandona received research support from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AbbVie and was a consultant to AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, and others.

Dr. Petrie disclosed receiving personal fees and travel expenses from Novo Nordisk; grants and personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, Quintiles, and Janssen; nonfinancial support from Merck and Itamar Medical; and personal fees from Lilly, ACI Clinical, and Pfizer.

LISBON – Despite some earlier concerns over safety, sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT) inhibitors appear to be back on track for adjunctive use in people with type 1 diabetes (T1DM), according to phase 3 study findings presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Results of the DEPICT-1 study, showed improved glycemic control, greater weight loss, and no increased risk for either hypoglycemia or ketoacidosis in people treated with the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) versus those treated with placebo.

When researchers compared the two dapagliflozin doses with placebo, the mean difference in body weight from baseline to week 24 was –2.96% and –3.72% (both P less than .0001).

Rates of any hypoglycemia in the placebo, 5-mg dapagliflozin, and 10-mg dapagliflozin groups were a respective 79.6%, 79.4%, and 79.4%, and rates of severe hypoglycemia were 7.3%, 7.6%, and 6.4%.

Diabetic ketoacidosis occurred in a respective 1.2%, 1.4%, and 1.7% of patients treated with placebo, dapagliflozin 5 mg, and dapagliflozin 10 mg, respectively.

“Based on this 24-week study, dapagliflozin may be considered as a good candidate as an adjunct to insulin to improve glycemic control in type 1 diabetes,” said the lead investigator for the DEPICT-1 trial, Paresh Dandona, MD, PhD, at the EASD 2017 meeting.

“There may also be other potential long-term cardiovascular and renal benefits, which have recently been demonstrated in type 2 diabetes,” suggested Dr. Dandona, who is a distinguished professor of medicine and chief of the division of endocrinology at the State University of New York at Buffalo. “Of course, that’s an open question, which needs to be investigated and determined in future.”

DEPICT-1 is the first phase 3, randomized, blinded, clinical trial of a selective SGLT2 inhibitor in T1DM, the study’s investigators said in an early online publication (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[17]30308-X). The study was conducted at 143 sites in 17 centers and involved 833 people with T1DM who were not achieving optimal blood glucose control.

Adults with an HbA1c of 7.7% or higher who had been taking insulin for at least 12 months were recruited and underwent an 8-week lead-in period to optimize their diabetes management before being randomized to take placebo or dapagliflozin 5 mg or 10 mg for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was the change in HbA1c at Week 24.

DEPICT-1 “provides encouraging short-term data for the efficacy of adjunct SGLT2 inhibition in type 1 diabetes but might also provide insights into how the risk of ketoacidosis can be minimized,” John Petrie, MD, commented in an editorial that accompanied the published findings.

Dr. Petrie, professor of diabetic medicine at the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences at the University of Glasgow, observed, however, that the results needed to be considered in the context of similar, and also recently presented, findings from the inTandem3 trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708337) with the investigational dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor sotagliflozin. Other trials are expected to report soon with another SGLT2 inhibitor, empagliflozin.

In inTandem3, sotagliflozin helped more people who had T1DM and were on stable insulin to achieve an HbA1c level of 7% or lower at week 24 with no episodes of severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis, compared with those who took insulin alone (28.6% vs. 15.2%; P less than .001). However, the overall rates of ketoacidosis were higher in the patients treated with sotagliflozin than in those treated with placebo, at 3% versus 0.6%, respectively.

In both inTandem3 and DEPICT-1, strategies were in place to help carefully monitor and manage ketoacidosis. Dr. Petrie observed that patients in the latter trial were given a meter that measured both their blood glucose and ketones and were seen in a clinic regularly to assess the risk of ketoacidosis. These frequent visits, which occurred every 2 weeks, were shown to have an independent effect on HbA1c, he pointed out.

“Nevertheless, the investigators kept real-world clinical practice in mind by providing a very simple rule that insulin doses should be reduced by no more than 20% when study medication was started and that they should subsequently be titrated back towards the initial dose,” Dr. Petrie said. “This rule seemed to be quite effective in mitigating ketoacidosis and is feasible to implement in modern clinical practice since meters that measure ketones are increasingly available.

So does this mean a license for SGLT-targeting agents in T1DM could be coming soon? Not yet, Dr. Petrie suggests. “Regulators are likely to await at least the results of the 12-month follow-up, and data from other ongoing trials, before considering an indication for SGLT2 inhibitors in type 1 diabetes,” he said.

Adjunct treatment with these drugs also may require that individuals have “a good understanding of the early-warning symptoms of ketoacidosis” and be prepared to undertake regular home monitoring of both their blood glucose and ketones, as well as having a high level of communication with their diabetes health care providers.

AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb funded the study.

Dr. Dandona received research support from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AbbVie and was a consultant to AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, and others.

Dr. Petrie disclosed receiving personal fees and travel expenses from Novo Nordisk; grants and personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, Quintiles, and Janssen; nonfinancial support from Merck and Itamar Medical; and personal fees from Lilly, ACI Clinical, and Pfizer.

LISBON – Despite some earlier concerns over safety, sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT) inhibitors appear to be back on track for adjunctive use in people with type 1 diabetes (T1DM), according to phase 3 study findings presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Results of the DEPICT-1 study, showed improved glycemic control, greater weight loss, and no increased risk for either hypoglycemia or ketoacidosis in people treated with the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) versus those treated with placebo.

When researchers compared the two dapagliflozin doses with placebo, the mean difference in body weight from baseline to week 24 was –2.96% and –3.72% (both P less than .0001).

Rates of any hypoglycemia in the placebo, 5-mg dapagliflozin, and 10-mg dapagliflozin groups were a respective 79.6%, 79.4%, and 79.4%, and rates of severe hypoglycemia were 7.3%, 7.6%, and 6.4%.

Diabetic ketoacidosis occurred in a respective 1.2%, 1.4%, and 1.7% of patients treated with placebo, dapagliflozin 5 mg, and dapagliflozin 10 mg, respectively.

“Based on this 24-week study, dapagliflozin may be considered as a good candidate as an adjunct to insulin to improve glycemic control in type 1 diabetes,” said the lead investigator for the DEPICT-1 trial, Paresh Dandona, MD, PhD, at the EASD 2017 meeting.

“There may also be other potential long-term cardiovascular and renal benefits, which have recently been demonstrated in type 2 diabetes,” suggested Dr. Dandona, who is a distinguished professor of medicine and chief of the division of endocrinology at the State University of New York at Buffalo. “Of course, that’s an open question, which needs to be investigated and determined in future.”

DEPICT-1 is the first phase 3, randomized, blinded, clinical trial of a selective SGLT2 inhibitor in T1DM, the study’s investigators said in an early online publication (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[17]30308-X). The study was conducted at 143 sites in 17 centers and involved 833 people with T1DM who were not achieving optimal blood glucose control.

Adults with an HbA1c of 7.7% or higher who had been taking insulin for at least 12 months were recruited and underwent an 8-week lead-in period to optimize their diabetes management before being randomized to take placebo or dapagliflozin 5 mg or 10 mg for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was the change in HbA1c at Week 24.

DEPICT-1 “provides encouraging short-term data for the efficacy of adjunct SGLT2 inhibition in type 1 diabetes but might also provide insights into how the risk of ketoacidosis can be minimized,” John Petrie, MD, commented in an editorial that accompanied the published findings.

Dr. Petrie, professor of diabetic medicine at the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences at the University of Glasgow, observed, however, that the results needed to be considered in the context of similar, and also recently presented, findings from the inTandem3 trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708337) with the investigational dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor sotagliflozin. Other trials are expected to report soon with another SGLT2 inhibitor, empagliflozin.

In inTandem3, sotagliflozin helped more people who had T1DM and were on stable insulin to achieve an HbA1c level of 7% or lower at week 24 with no episodes of severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis, compared with those who took insulin alone (28.6% vs. 15.2%; P less than .001). However, the overall rates of ketoacidosis were higher in the patients treated with sotagliflozin than in those treated with placebo, at 3% versus 0.6%, respectively.

In both inTandem3 and DEPICT-1, strategies were in place to help carefully monitor and manage ketoacidosis. Dr. Petrie observed that patients in the latter trial were given a meter that measured both their blood glucose and ketones and were seen in a clinic regularly to assess the risk of ketoacidosis. These frequent visits, which occurred every 2 weeks, were shown to have an independent effect on HbA1c, he pointed out.

“Nevertheless, the investigators kept real-world clinical practice in mind by providing a very simple rule that insulin doses should be reduced by no more than 20% when study medication was started and that they should subsequently be titrated back towards the initial dose,” Dr. Petrie said. “This rule seemed to be quite effective in mitigating ketoacidosis and is feasible to implement in modern clinical practice since meters that measure ketones are increasingly available.

So does this mean a license for SGLT-targeting agents in T1DM could be coming soon? Not yet, Dr. Petrie suggests. “Regulators are likely to await at least the results of the 12-month follow-up, and data from other ongoing trials, before considering an indication for SGLT2 inhibitors in type 1 diabetes,” he said.

Adjunct treatment with these drugs also may require that individuals have “a good understanding of the early-warning symptoms of ketoacidosis” and be prepared to undertake regular home monitoring of both their blood glucose and ketones, as well as having a high level of communication with their diabetes health care providers.

AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb funded the study.

Dr. Dandona received research support from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AbbVie and was a consultant to AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, and others.

Dr. Petrie disclosed receiving personal fees and travel expenses from Novo Nordisk; grants and personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, Quintiles, and Janssen; nonfinancial support from Merck and Itamar Medical; and personal fees from Lilly, ACI Clinical, and Pfizer.

AT EASD 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Dapagliflozin 5 mg and 10 mg reduced HbA1c from Week 0 to Week 24 more (0.42% and 0.45%, respectively) than did placebo (both P less than .0001).

Data source: A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, parallel-controlled, multicenter trial conducted in 833 people with type 1 diabetes.

Disclosures: AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb funded the study. Dr. Dandona disclosed acting as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck, Intarcia, and AbbVie, as well as receiving research support from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AbbVie. Dr. Petrie disclosed receiving personal fees and travel expenses from Novo Nordisk; grants and personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, Quintiles, and Janssen; nonfinancial support from Merck and Itamar Medical; and personal fees from Lilly, ACI Clinical, and Pfizer.

Fentanyl in the cath lab questioned

BARCELONA – The current routine use of intravenous fentanyl in the cardiac catheterization lab for patient comfort during coronary angiography has been called into question by the results of a double-blind randomized trial presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The trial, known as PACIFY, showed that IV fentanyl delayed absorption of the oral P2Y12 inhibitor ticagrelor (Brilinta) by up to 4 hours. That’s a disturbing finding that could account for the relatively high risk of stent thrombosis in the first hours after percutaneous coronary intervention, according to lead investigator John W. McEvoy, MD, a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“These data challenge the routine and nonselective use of fentanyl for cardiac catheterization and PCI, particularly when rapid platelet inhibition is desirable,” he said, adding, “This would represent a significant change in U.S. cath lab practice.”

PACIFY (Platelet Aggregation After Ticagrelor Inhibition and Fentanyl) was a single-center trial in which 212 patients undergoing PCI were randomized in double-blind fashion to fentanyl or no fentanyl on top of a local anesthetic and IV midazolam (Versed). In addition, the 70 subjects undergoing PCI with stent placement received a 180-mg loading dose of ticagrelor intraprocedurally.

The primary endpoint was ticagrelor plasma concentration during the first 24 hours after the drug’s administration. Secondary endpoints were patients’ self-reported maximum pain during the procedure and platelet inhibition at 2 hours.

The plasma concentration time area under the curve over the course of 24 hours was superior in the no-fentanyl group by a margin of 3,441 ng/mL–1 per hour to 2,016 ng/mL–1 per hour. Moreover, 37% of fentanyl recipients displayed high platelet reactivity at 2 hours as measured by light transmission platelet aggregometry, compared with none of the no-fentanyl controls.

Pain was similarly well controlled in both treatment arms, casting doubt on the widespread belief among U.S. interventionalists that routine administration of fentanyl in the cath lab is necessary for patient comfort. Patients in the control arm could receive bailout fentanyl upon request; only two did so.

Dr. McEvoy reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

BARCELONA – The current routine use of intravenous fentanyl in the cardiac catheterization lab for patient comfort during coronary angiography has been called into question by the results of a double-blind randomized trial presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The trial, known as PACIFY, showed that IV fentanyl delayed absorption of the oral P2Y12 inhibitor ticagrelor (Brilinta) by up to 4 hours. That’s a disturbing finding that could account for the relatively high risk of stent thrombosis in the first hours after percutaneous coronary intervention, according to lead investigator John W. McEvoy, MD, a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“These data challenge the routine and nonselective use of fentanyl for cardiac catheterization and PCI, particularly when rapid platelet inhibition is desirable,” he said, adding, “This would represent a significant change in U.S. cath lab practice.”

PACIFY (Platelet Aggregation After Ticagrelor Inhibition and Fentanyl) was a single-center trial in which 212 patients undergoing PCI were randomized in double-blind fashion to fentanyl or no fentanyl on top of a local anesthetic and IV midazolam (Versed). In addition, the 70 subjects undergoing PCI with stent placement received a 180-mg loading dose of ticagrelor intraprocedurally.

The primary endpoint was ticagrelor plasma concentration during the first 24 hours after the drug’s administration. Secondary endpoints were patients’ self-reported maximum pain during the procedure and platelet inhibition at 2 hours.

The plasma concentration time area under the curve over the course of 24 hours was superior in the no-fentanyl group by a margin of 3,441 ng/mL–1 per hour to 2,016 ng/mL–1 per hour. Moreover, 37% of fentanyl recipients displayed high platelet reactivity at 2 hours as measured by light transmission platelet aggregometry, compared with none of the no-fentanyl controls.