User login

The Emerging Role of Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis and Management of CRC

Key statistics for colorectal cancer. American Cancer Society. Revised January 13, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

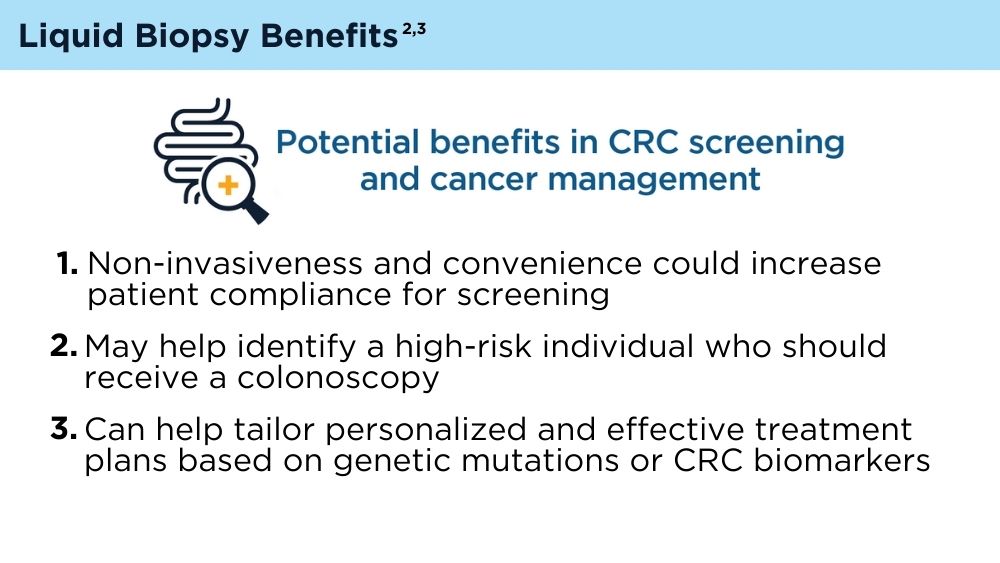

Mazouji O, Ouhajjou A, Incitti R, Mansour H. Updates on clinical use of liquid biopsy in colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment guidance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:660924. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.660924

Vacante M, Ciuni R, Basile F, Biondi A. The liquid biopsy in the management of colorectal cancer: an overview. Biomedicines. 2020;8(9):308. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8090308

American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2020-2022. Published 2022. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf

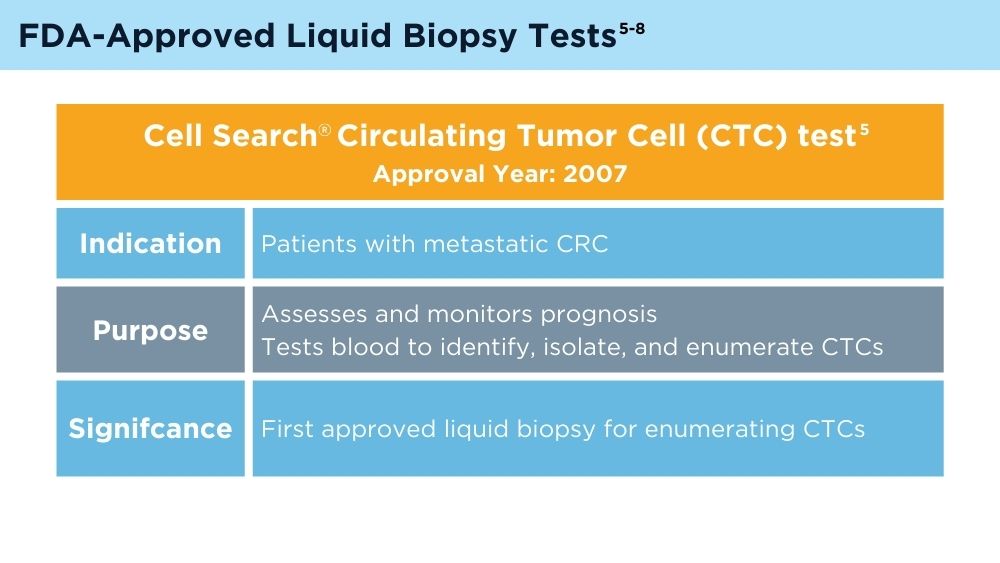

Johnson & Johnson. FDA clears Cellsearch™ circulating tumor cell test [news release]. Published February 27, 2008. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://johnsonandjohnson.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-clears-cellsearchtm-circulating-tumor-cell-test

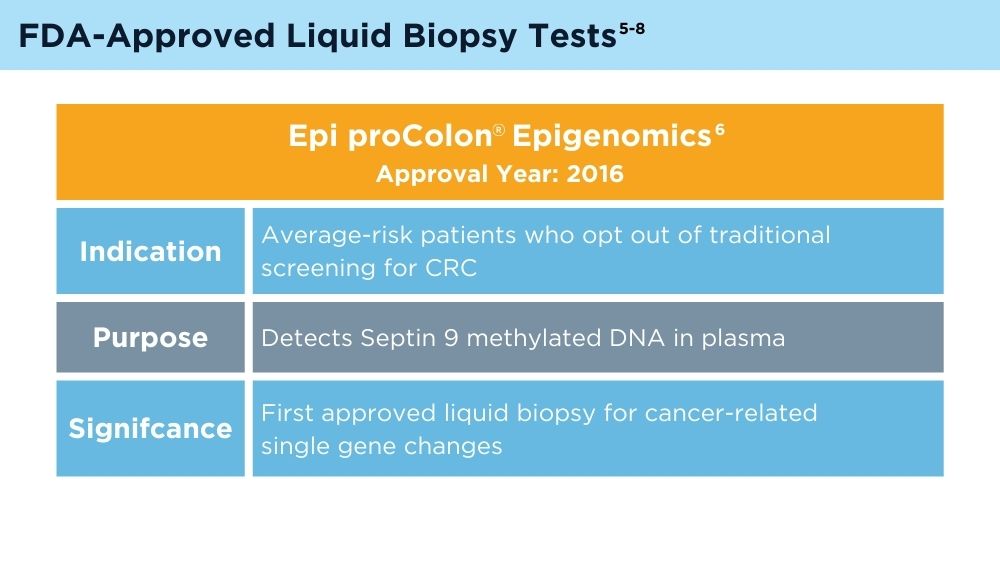

US Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data, Epi proColon®. PMA number P130001. Published April 12, 2016. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/p130001b.pdf

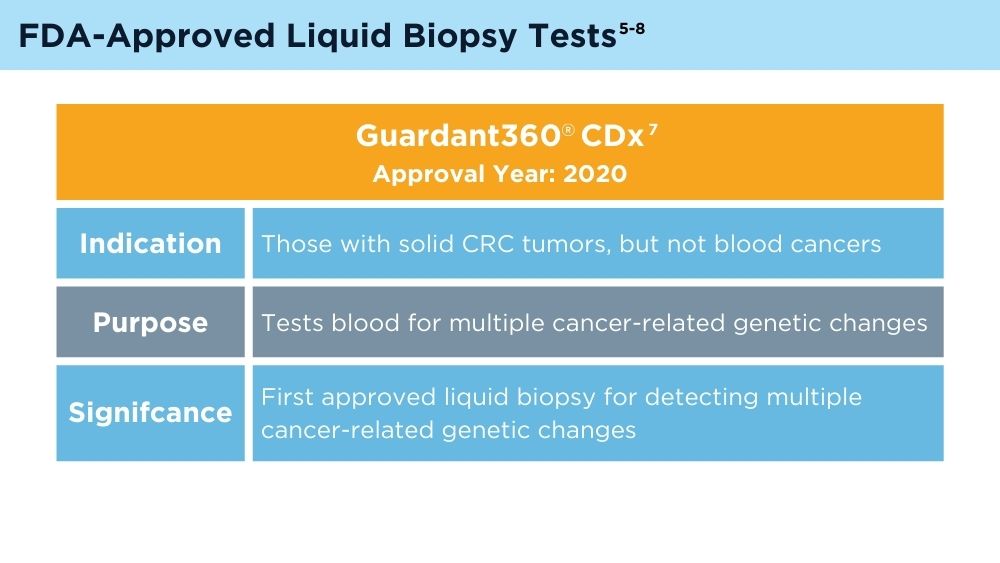

FDA approves blood tests that can help guide cancer treatment. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Published October 15, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/fda-guardant-360-foundation-one-cancer-liquid-biopsy

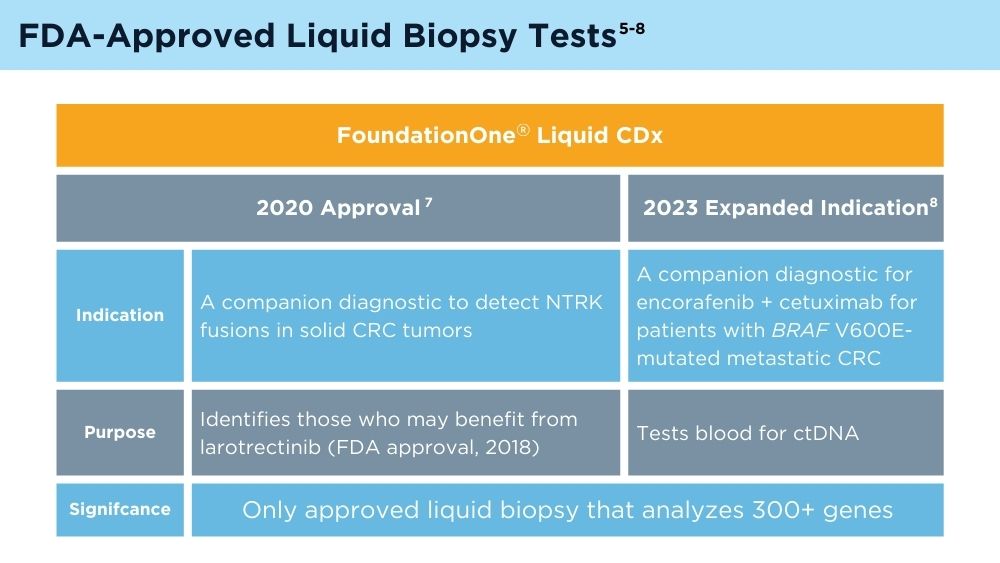

Foundation Medicine. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves FoundationOne®LiquidCDx as a companion diagnostic for Pfizer’s BRAFTOVI® (encorafenib) in combination with cetuximab to identify patients with BRAF V600E alterations in metastatic colorectal cancer [press release]. Published June 10, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.foundationmedicine.com/press-releases/f9b285eb-db6d-4f61-856c-3f1edb803937

Key statistics for colorectal cancer. American Cancer Society. Revised January 13, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

Mazouji O, Ouhajjou A, Incitti R, Mansour H. Updates on clinical use of liquid biopsy in colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment guidance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:660924. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.660924

Vacante M, Ciuni R, Basile F, Biondi A. The liquid biopsy in the management of colorectal cancer: an overview. Biomedicines. 2020;8(9):308. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8090308

American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2020-2022. Published 2022. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf

Johnson & Johnson. FDA clears Cellsearch™ circulating tumor cell test [news release]. Published February 27, 2008. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://johnsonandjohnson.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-clears-cellsearchtm-circulating-tumor-cell-test

US Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data, Epi proColon®. PMA number P130001. Published April 12, 2016. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/p130001b.pdf

FDA approves blood tests that can help guide cancer treatment. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Published October 15, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/fda-guardant-360-foundation-one-cancer-liquid-biopsy

Foundation Medicine. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves FoundationOne®LiquidCDx as a companion diagnostic for Pfizer’s BRAFTOVI® (encorafenib) in combination with cetuximab to identify patients with BRAF V600E alterations in metastatic colorectal cancer [press release]. Published June 10, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.foundationmedicine.com/press-releases/f9b285eb-db6d-4f61-856c-3f1edb803937

Key statistics for colorectal cancer. American Cancer Society. Revised January 13, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

Mazouji O, Ouhajjou A, Incitti R, Mansour H. Updates on clinical use of liquid biopsy in colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment guidance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:660924. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.660924

Vacante M, Ciuni R, Basile F, Biondi A. The liquid biopsy in the management of colorectal cancer: an overview. Biomedicines. 2020;8(9):308. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8090308

American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2020-2022. Published 2022. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf

Johnson & Johnson. FDA clears Cellsearch™ circulating tumor cell test [news release]. Published February 27, 2008. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://johnsonandjohnson.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-clears-cellsearchtm-circulating-tumor-cell-test

US Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data, Epi proColon®. PMA number P130001. Published April 12, 2016. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/p130001b.pdf

FDA approves blood tests that can help guide cancer treatment. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Published October 15, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/fda-guardant-360-foundation-one-cancer-liquid-biopsy

Foundation Medicine. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves FoundationOne®LiquidCDx as a companion diagnostic for Pfizer’s BRAFTOVI® (encorafenib) in combination with cetuximab to identify patients with BRAF V600E alterations in metastatic colorectal cancer [press release]. Published June 10, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.foundationmedicine.com/press-releases/f9b285eb-db6d-4f61-856c-3f1edb803937

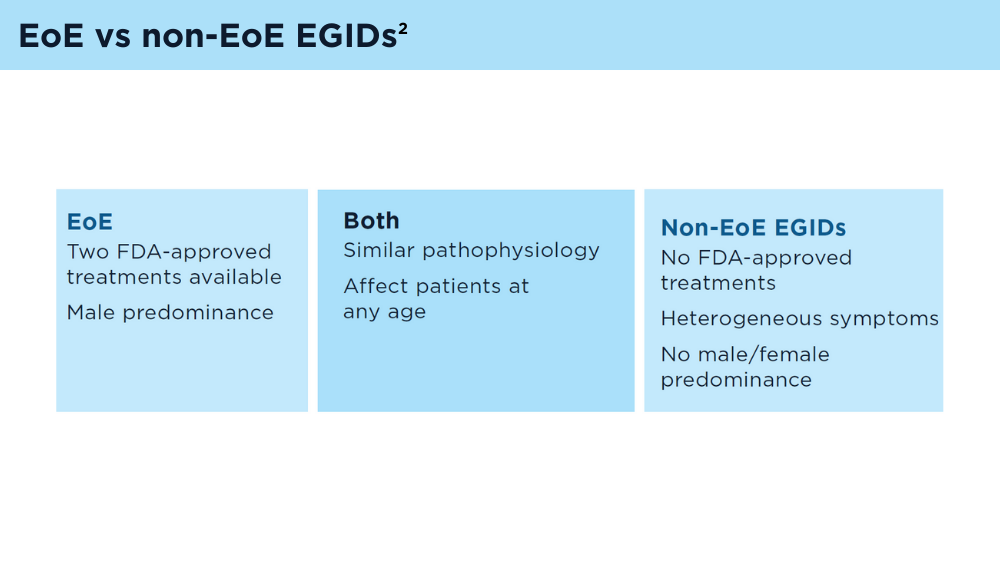

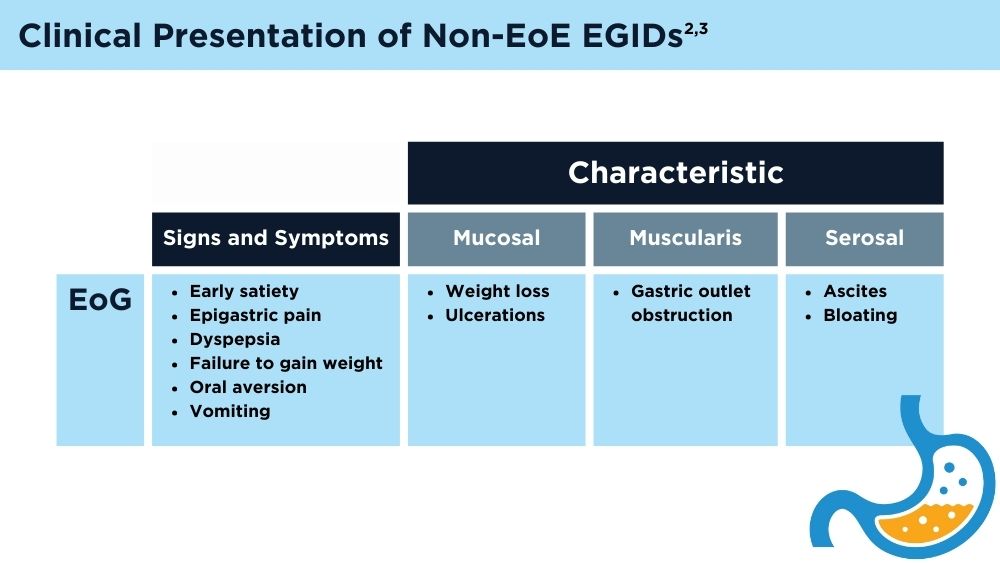

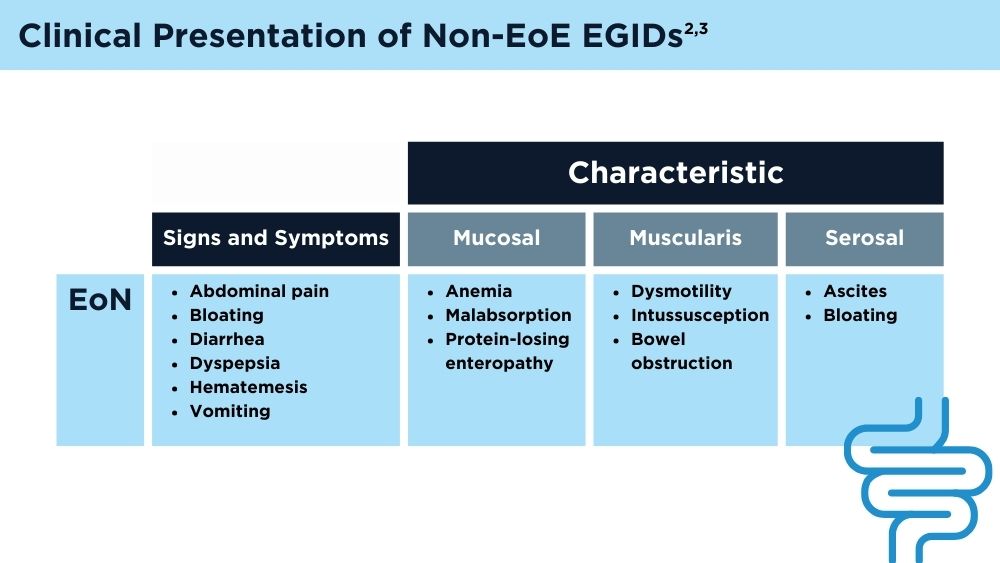

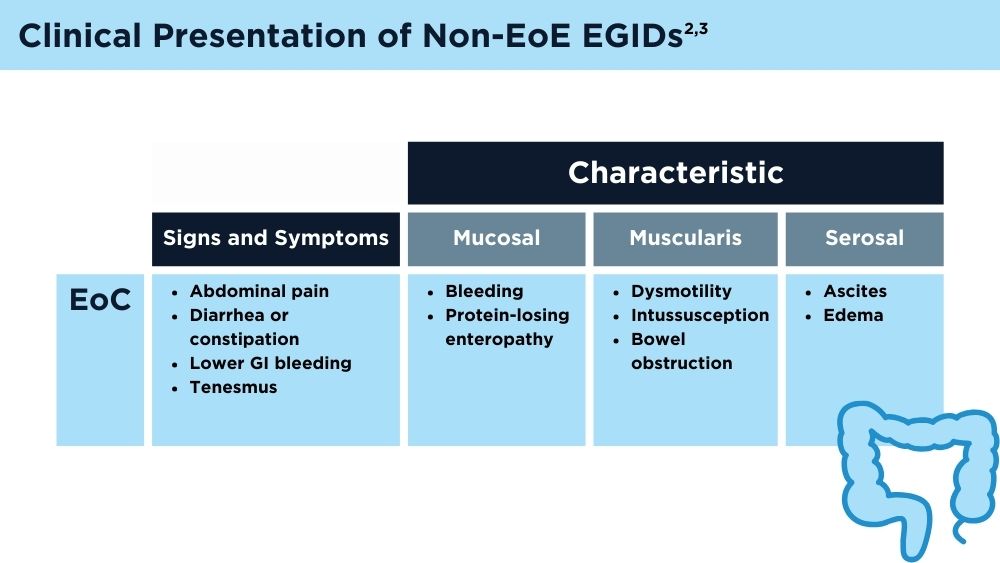

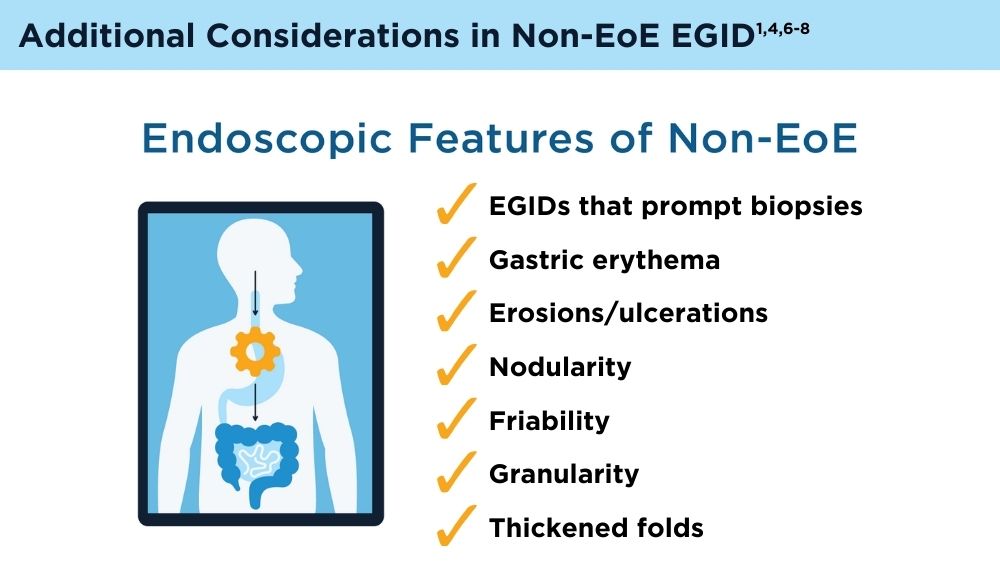

Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Beyond EoE

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Abonia JP, et al. International consensus recommendations for eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease nomenclature. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2474-2484.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.017

- Naramore S, Gupta SK. Nonesophageal eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders: clinical care and future directions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(3):318-321. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000002040

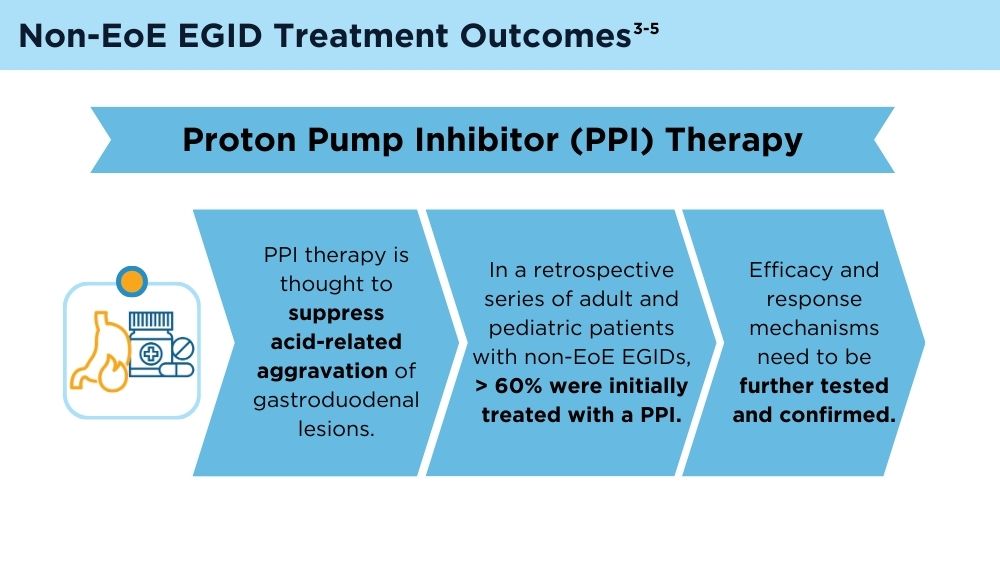

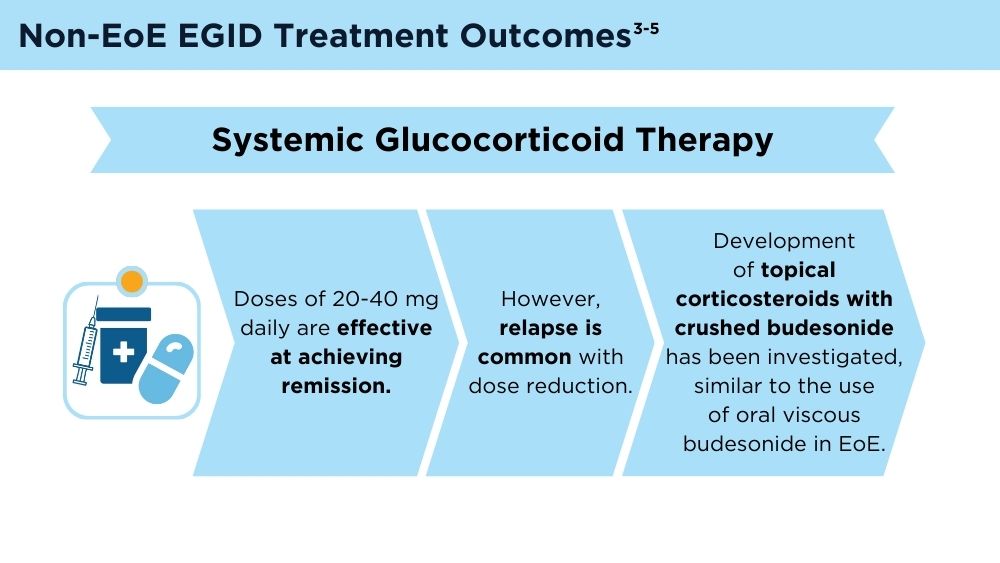

- Kinoshita Y, Sanuki T. Review of non-eosinophilic esophagitis-eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease (non-EoE-EGID) and a case series of twenty-eight affected patients. Biomolecules. 2023;13(9):1417. doi:10.3390/biom13091417

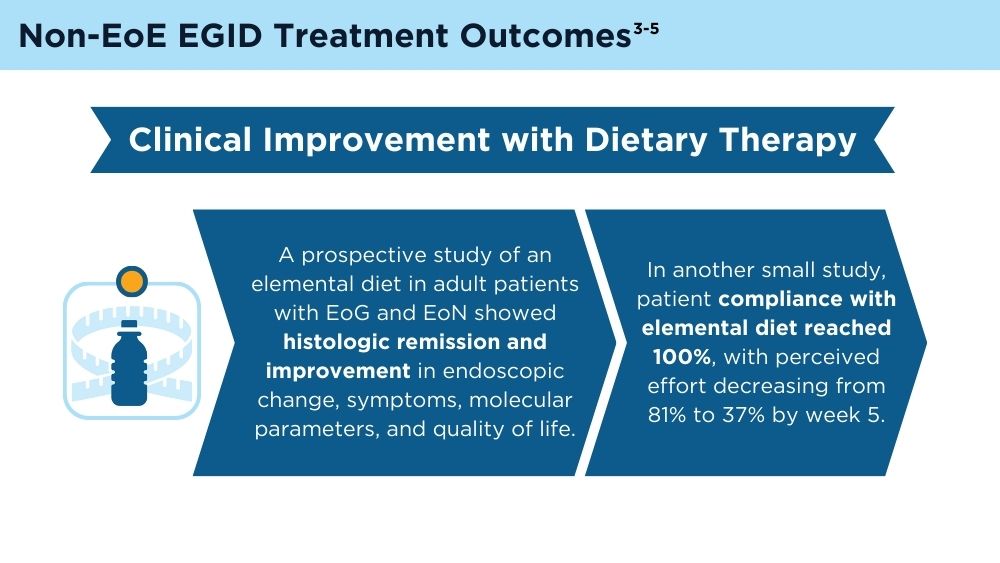

- Gonsalves N, Doerfler B, Zalewski A, et al. Prospective study of an amino acid-based elemental diet in an eosinophilic gastritis and gastroenteritis nutrition trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152(3):676-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2023.05.024

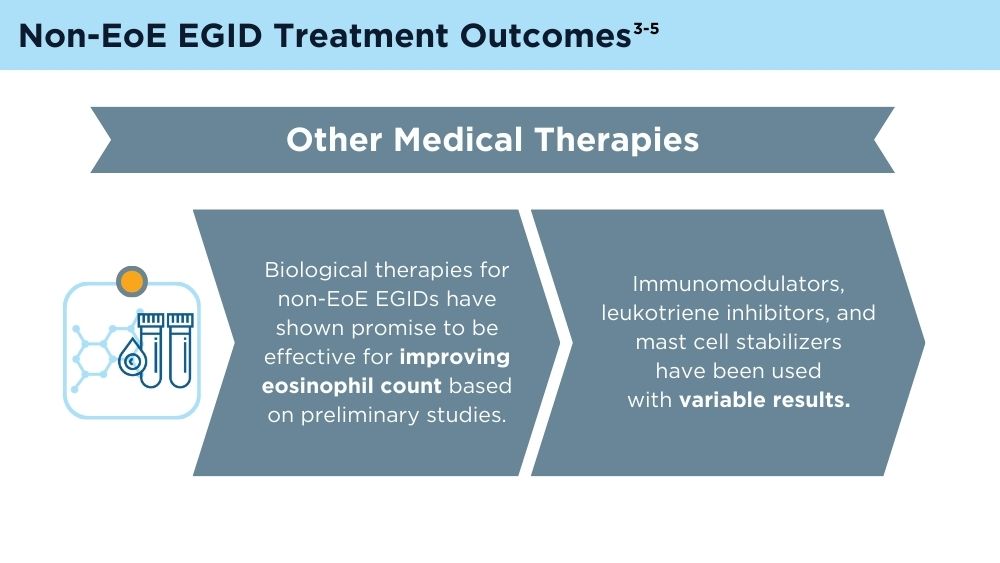

- Oshima T. Biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Intern Med. 2023;62(23):3429-3430. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.1911-23

- Pineton de Chambrun G, Gonzalez F, Canva JY, et al. Natural history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):950-956.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.017

- Hirano I, Collins MH, King E, et al; CEGIR Investigators. Prospective endoscopic activity assessment for eosinophilic gastritis in a multi-site cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(3):413-423. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001625

- Pesek RD, Reed CC, Muir AB, et al; Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR). Increasing rates of diagnosis, substantial co-occurrence, and variable treatment patterns of eosinophilic gastritis, gastroenteritis, and colitis based on 10-year data across a multicenter consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):984-994. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000228

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Abonia JP, et al. International consensus recommendations for eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease nomenclature. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2474-2484.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.017

- Naramore S, Gupta SK. Nonesophageal eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders: clinical care and future directions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(3):318-321. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000002040

- Kinoshita Y, Sanuki T. Review of non-eosinophilic esophagitis-eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease (non-EoE-EGID) and a case series of twenty-eight affected patients. Biomolecules. 2023;13(9):1417. doi:10.3390/biom13091417

- Gonsalves N, Doerfler B, Zalewski A, et al. Prospective study of an amino acid-based elemental diet in an eosinophilic gastritis and gastroenteritis nutrition trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152(3):676-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2023.05.024

- Oshima T. Biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Intern Med. 2023;62(23):3429-3430. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.1911-23

- Pineton de Chambrun G, Gonzalez F, Canva JY, et al. Natural history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):950-956.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.017

- Hirano I, Collins MH, King E, et al; CEGIR Investigators. Prospective endoscopic activity assessment for eosinophilic gastritis in a multi-site cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(3):413-423. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001625

- Pesek RD, Reed CC, Muir AB, et al; Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR). Increasing rates of diagnosis, substantial co-occurrence, and variable treatment patterns of eosinophilic gastritis, gastroenteritis, and colitis based on 10-year data across a multicenter consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):984-994. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000228

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Abonia JP, et al. International consensus recommendations for eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease nomenclature. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2474-2484.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.017

- Naramore S, Gupta SK. Nonesophageal eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders: clinical care and future directions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(3):318-321. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000002040

- Kinoshita Y, Sanuki T. Review of non-eosinophilic esophagitis-eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease (non-EoE-EGID) and a case series of twenty-eight affected patients. Biomolecules. 2023;13(9):1417. doi:10.3390/biom13091417

- Gonsalves N, Doerfler B, Zalewski A, et al. Prospective study of an amino acid-based elemental diet in an eosinophilic gastritis and gastroenteritis nutrition trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152(3):676-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2023.05.024

- Oshima T. Biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Intern Med. 2023;62(23):3429-3430. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.1911-23

- Pineton de Chambrun G, Gonzalez F, Canva JY, et al. Natural history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):950-956.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.017

- Hirano I, Collins MH, King E, et al; CEGIR Investigators. Prospective endoscopic activity assessment for eosinophilic gastritis in a multi-site cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(3):413-423. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001625

- Pesek RD, Reed CC, Muir AB, et al; Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR). Increasing rates of diagnosis, substantial co-occurrence, and variable treatment patterns of eosinophilic gastritis, gastroenteritis, and colitis based on 10-year data across a multicenter consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):984-994. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000228

Emerging Evidence Supports Dietary Management of MASLD Through Gut-Liver Axis

WASHINGTON — , according to a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

For instance, patients with MASLD had lower intake of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids but higher consumption of added sugars and ultraprocessed foods, which correlated with the associated bacterial species and functional pathways.

“MASLD is an escalating concern globally, which highlights the need for innovative targets for disease prevention and management,” said lead author Georgina Williams, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in diet and gastroenterology at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

“Therapeutic options often rely on lifestyle modifications, with a focus on weight loss,” she said. “Diet is considered a key component of disease management.”

Although calorie restriction with a 3%-5% fat loss is associated with hepatic benefits in MASLD, Dr. Williams noted, researchers have considered whole dietary patterns and the best fit for patients. Aspects of the Mediterranean diet may be effective, as reflected in recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), which highlight dietary components such as limited carbohydrates and saturated fat, along with high fiber and unsaturated fats. The gut microbiome may be essential to consider as well, she said, given MASLD-associated differences in bile acid metabolism, inflammation, and ethanol production.

Dr. Williams and colleagues conducted a retrospective case-control study in an outpatient liver clinic to understand diet and dysbiosis in MASLD, looking at differences in diet, gut microbiota composition, and functional pathways in those with and without MASLD. The researchers investigated daily average intake, serum, and stool samples among 50 people (25 per group) matched for age and gender, comparing fibrosis-4, MASLD severity scores, macronutrients, micronutrients, food groups, metagenomic sequencing, and inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-1ß, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, cytokeratin (CK)-18, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

Dietary Characteristics

At baseline, the groups differed by ethnicity, prescription medication use, and body mass index (BMI), where the MASLD group had greater ethnic diversity, medication use, and BMI. In addition, the MASLD group had a zero to mild score of fibrosis.

Overall, energy intake didn’t differ significantly between the two groups. The control group had higher alcohol intake, likely since the MASLD group was recommended to reduce alcohol intake, though the difference was about 5 grams per day. The MASLD group also had less caffeine intake than the control group, as well as slightly lower protein intake, though the differences weren’t statistically significant.

While consumption of total carbohydrates didn’t differ significantly between the groups, participants with MASLD consumed more calories from carbohydrates than did the controls. The MASLD group consumed more calories from added and free sugars and didn’t meet recommendations for dietary fiber.

With particular food groups, participants with MASLD ate significantly fewer whole grains, red and orange fruits, and leafy green vegetables. When consuming fruit, those with MASLD were more likely to drink juice than eat whole fruit. These findings could be relevant when considering high sugar intake and low dietary fiber, Dr. Williams said.

With dietary fat, there were no differences in total fat between the groups, but the fat profiles differed. The control group was significantly more likely to consume omega-3 fatty acids, including alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The MASLD group was less likely to consume seafood, nuts, seeds, avocado, and olive oil.

With inflammatory markers, hsCRP and CK-18 were increased in MASLD, while IL-1ß was increased in controls, which was consistently associated with higher alcohol intake among the control group. IL-6 and TNF-α didn’t differ between the groups.

Notably, dietary fats were most consistently associated with inflammatory markers, Dr. Williams said, with inflammation being positively associated with saturated fats and negatively associated with unsaturated fats.

Looking at microbiota, the alpha diversity was no different, but the beta diversity was across 162 taxa. Per bacterial species, there was an inverse relationship between MASLD and associations with unsaturated fat, as well as positive indicators of high sugar and fructose intake and low unsaturated fat and dietary fiber intake.

Beyond that, the functional pathways enriched in MASLD were associated with increased sugar and carbohydrates, reduced fiber, and reduced unsaturated fat. Lower butyrate production in MASLD was associated with low intake of nuts, seeds, and unsaturated fat.

In Clinical Practice

Dr. Williams suggested reinforcing AASLD guidelines and looking at diet quality, not just diet quantity. Although an energy deficit remains relevant in MASLD, macronutrient consumption matters across dietary fats, fibers, and sugars.

Future avenues for research include metabolomic pathways related to bile acids and fatty acids, she said, as well as disentangling metabolic syndrome from MASLD outcomes.

Session moderator Olivier Barbier, PhD, professor of pharmacy at Laval University in Quebec, Canada, asked about microbiome differences across countries. Dr. Williams noted the limitations in this study of looking at differences across geography and ethnicity, particularly in Australia, but said the species identified were consistent with those found in most literature globally.

In response to other questions after the presentation, Dr. Williams said supplements (such as omega-3 fatty acids) were included in total intake, and those taking prebiotics or probiotics were excluded from the study. In an upcoming clinical trial, she and colleagues plan to control for household microbiomes as well.

“The premise is that microbiomes are shared between households, so when you’re doing these sorts of large-scale clinical studies, if you’re going to look at the microbiome, then you should control for one of the major confounding variables,” said Mark Sundrud, PhD, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Center for Digestive Health in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Dr. Sundrud, who wasn’t involved with this study, presented on the role of bile acids in mucosal immune cell function at DDW.

“We’ve done a collaborative study looking at microbiomes and bile acids in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients versus controls,” which included consideration of households, he said. “We were able to see more intrinsic disease-specific changes.”

Dr. Williams declared no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sundrud has served as a scientific adviser to Sage Therapeutics.

WASHINGTON — , according to a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

For instance, patients with MASLD had lower intake of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids but higher consumption of added sugars and ultraprocessed foods, which correlated with the associated bacterial species and functional pathways.

“MASLD is an escalating concern globally, which highlights the need for innovative targets for disease prevention and management,” said lead author Georgina Williams, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in diet and gastroenterology at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

“Therapeutic options often rely on lifestyle modifications, with a focus on weight loss,” she said. “Diet is considered a key component of disease management.”

Although calorie restriction with a 3%-5% fat loss is associated with hepatic benefits in MASLD, Dr. Williams noted, researchers have considered whole dietary patterns and the best fit for patients. Aspects of the Mediterranean diet may be effective, as reflected in recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), which highlight dietary components such as limited carbohydrates and saturated fat, along with high fiber and unsaturated fats. The gut microbiome may be essential to consider as well, she said, given MASLD-associated differences in bile acid metabolism, inflammation, and ethanol production.

Dr. Williams and colleagues conducted a retrospective case-control study in an outpatient liver clinic to understand diet and dysbiosis in MASLD, looking at differences in diet, gut microbiota composition, and functional pathways in those with and without MASLD. The researchers investigated daily average intake, serum, and stool samples among 50 people (25 per group) matched for age and gender, comparing fibrosis-4, MASLD severity scores, macronutrients, micronutrients, food groups, metagenomic sequencing, and inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-1ß, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, cytokeratin (CK)-18, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

Dietary Characteristics

At baseline, the groups differed by ethnicity, prescription medication use, and body mass index (BMI), where the MASLD group had greater ethnic diversity, medication use, and BMI. In addition, the MASLD group had a zero to mild score of fibrosis.

Overall, energy intake didn’t differ significantly between the two groups. The control group had higher alcohol intake, likely since the MASLD group was recommended to reduce alcohol intake, though the difference was about 5 grams per day. The MASLD group also had less caffeine intake than the control group, as well as slightly lower protein intake, though the differences weren’t statistically significant.

While consumption of total carbohydrates didn’t differ significantly between the groups, participants with MASLD consumed more calories from carbohydrates than did the controls. The MASLD group consumed more calories from added and free sugars and didn’t meet recommendations for dietary fiber.

With particular food groups, participants with MASLD ate significantly fewer whole grains, red and orange fruits, and leafy green vegetables. When consuming fruit, those with MASLD were more likely to drink juice than eat whole fruit. These findings could be relevant when considering high sugar intake and low dietary fiber, Dr. Williams said.

With dietary fat, there were no differences in total fat between the groups, but the fat profiles differed. The control group was significantly more likely to consume omega-3 fatty acids, including alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The MASLD group was less likely to consume seafood, nuts, seeds, avocado, and olive oil.

With inflammatory markers, hsCRP and CK-18 were increased in MASLD, while IL-1ß was increased in controls, which was consistently associated with higher alcohol intake among the control group. IL-6 and TNF-α didn’t differ between the groups.

Notably, dietary fats were most consistently associated with inflammatory markers, Dr. Williams said, with inflammation being positively associated with saturated fats and negatively associated with unsaturated fats.

Looking at microbiota, the alpha diversity was no different, but the beta diversity was across 162 taxa. Per bacterial species, there was an inverse relationship between MASLD and associations with unsaturated fat, as well as positive indicators of high sugar and fructose intake and low unsaturated fat and dietary fiber intake.

Beyond that, the functional pathways enriched in MASLD were associated with increased sugar and carbohydrates, reduced fiber, and reduced unsaturated fat. Lower butyrate production in MASLD was associated with low intake of nuts, seeds, and unsaturated fat.

In Clinical Practice

Dr. Williams suggested reinforcing AASLD guidelines and looking at diet quality, not just diet quantity. Although an energy deficit remains relevant in MASLD, macronutrient consumption matters across dietary fats, fibers, and sugars.

Future avenues for research include metabolomic pathways related to bile acids and fatty acids, she said, as well as disentangling metabolic syndrome from MASLD outcomes.

Session moderator Olivier Barbier, PhD, professor of pharmacy at Laval University in Quebec, Canada, asked about microbiome differences across countries. Dr. Williams noted the limitations in this study of looking at differences across geography and ethnicity, particularly in Australia, but said the species identified were consistent with those found in most literature globally.

In response to other questions after the presentation, Dr. Williams said supplements (such as omega-3 fatty acids) were included in total intake, and those taking prebiotics or probiotics were excluded from the study. In an upcoming clinical trial, she and colleagues plan to control for household microbiomes as well.

“The premise is that microbiomes are shared between households, so when you’re doing these sorts of large-scale clinical studies, if you’re going to look at the microbiome, then you should control for one of the major confounding variables,” said Mark Sundrud, PhD, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Center for Digestive Health in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Dr. Sundrud, who wasn’t involved with this study, presented on the role of bile acids in mucosal immune cell function at DDW.

“We’ve done a collaborative study looking at microbiomes and bile acids in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients versus controls,” which included consideration of households, he said. “We were able to see more intrinsic disease-specific changes.”

Dr. Williams declared no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sundrud has served as a scientific adviser to Sage Therapeutics.

WASHINGTON — , according to a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

For instance, patients with MASLD had lower intake of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids but higher consumption of added sugars and ultraprocessed foods, which correlated with the associated bacterial species and functional pathways.

“MASLD is an escalating concern globally, which highlights the need for innovative targets for disease prevention and management,” said lead author Georgina Williams, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in diet and gastroenterology at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

“Therapeutic options often rely on lifestyle modifications, with a focus on weight loss,” she said. “Diet is considered a key component of disease management.”

Although calorie restriction with a 3%-5% fat loss is associated with hepatic benefits in MASLD, Dr. Williams noted, researchers have considered whole dietary patterns and the best fit for patients. Aspects of the Mediterranean diet may be effective, as reflected in recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), which highlight dietary components such as limited carbohydrates and saturated fat, along with high fiber and unsaturated fats. The gut microbiome may be essential to consider as well, she said, given MASLD-associated differences in bile acid metabolism, inflammation, and ethanol production.

Dr. Williams and colleagues conducted a retrospective case-control study in an outpatient liver clinic to understand diet and dysbiosis in MASLD, looking at differences in diet, gut microbiota composition, and functional pathways in those with and without MASLD. The researchers investigated daily average intake, serum, and stool samples among 50 people (25 per group) matched for age and gender, comparing fibrosis-4, MASLD severity scores, macronutrients, micronutrients, food groups, metagenomic sequencing, and inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-1ß, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, cytokeratin (CK)-18, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

Dietary Characteristics

At baseline, the groups differed by ethnicity, prescription medication use, and body mass index (BMI), where the MASLD group had greater ethnic diversity, medication use, and BMI. In addition, the MASLD group had a zero to mild score of fibrosis.

Overall, energy intake didn’t differ significantly between the two groups. The control group had higher alcohol intake, likely since the MASLD group was recommended to reduce alcohol intake, though the difference was about 5 grams per day. The MASLD group also had less caffeine intake than the control group, as well as slightly lower protein intake, though the differences weren’t statistically significant.

While consumption of total carbohydrates didn’t differ significantly between the groups, participants with MASLD consumed more calories from carbohydrates than did the controls. The MASLD group consumed more calories from added and free sugars and didn’t meet recommendations for dietary fiber.

With particular food groups, participants with MASLD ate significantly fewer whole grains, red and orange fruits, and leafy green vegetables. When consuming fruit, those with MASLD were more likely to drink juice than eat whole fruit. These findings could be relevant when considering high sugar intake and low dietary fiber, Dr. Williams said.

With dietary fat, there were no differences in total fat between the groups, but the fat profiles differed. The control group was significantly more likely to consume omega-3 fatty acids, including alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The MASLD group was less likely to consume seafood, nuts, seeds, avocado, and olive oil.

With inflammatory markers, hsCRP and CK-18 were increased in MASLD, while IL-1ß was increased in controls, which was consistently associated with higher alcohol intake among the control group. IL-6 and TNF-α didn’t differ between the groups.

Notably, dietary fats were most consistently associated with inflammatory markers, Dr. Williams said, with inflammation being positively associated with saturated fats and negatively associated with unsaturated fats.

Looking at microbiota, the alpha diversity was no different, but the beta diversity was across 162 taxa. Per bacterial species, there was an inverse relationship between MASLD and associations with unsaturated fat, as well as positive indicators of high sugar and fructose intake and low unsaturated fat and dietary fiber intake.

Beyond that, the functional pathways enriched in MASLD were associated with increased sugar and carbohydrates, reduced fiber, and reduced unsaturated fat. Lower butyrate production in MASLD was associated with low intake of nuts, seeds, and unsaturated fat.

In Clinical Practice

Dr. Williams suggested reinforcing AASLD guidelines and looking at diet quality, not just diet quantity. Although an energy deficit remains relevant in MASLD, macronutrient consumption matters across dietary fats, fibers, and sugars.

Future avenues for research include metabolomic pathways related to bile acids and fatty acids, she said, as well as disentangling metabolic syndrome from MASLD outcomes.

Session moderator Olivier Barbier, PhD, professor of pharmacy at Laval University in Quebec, Canada, asked about microbiome differences across countries. Dr. Williams noted the limitations in this study of looking at differences across geography and ethnicity, particularly in Australia, but said the species identified were consistent with those found in most literature globally.

In response to other questions after the presentation, Dr. Williams said supplements (such as omega-3 fatty acids) were included in total intake, and those taking prebiotics or probiotics were excluded from the study. In an upcoming clinical trial, she and colleagues plan to control for household microbiomes as well.

“The premise is that microbiomes are shared between households, so when you’re doing these sorts of large-scale clinical studies, if you’re going to look at the microbiome, then you should control for one of the major confounding variables,” said Mark Sundrud, PhD, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Center for Digestive Health in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Dr. Sundrud, who wasn’t involved with this study, presented on the role of bile acids in mucosal immune cell function at DDW.

“We’ve done a collaborative study looking at microbiomes and bile acids in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients versus controls,” which included consideration of households, he said. “We were able to see more intrinsic disease-specific changes.”

Dr. Williams declared no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sundrud has served as a scientific adviser to Sage Therapeutics.

FROM DDW 2024

Subungual Nodule in a Pediatric Patient

The Diagnosis: Subungual Exostosis

Subungual exostosis should be considered as a possible cause of an exophytic subungual nodule in a young active female. In our patient, the involvement of the great toe was a clue, as the hallux is the most common location of subungual exostosis. The patient’s age and sex also were supportive, as subungual exostosis is most common in female children and adolescents— particularly those who are active, as trauma is thought to play a possible role in development of this benign tumor.1-3 Radiography is the preferred modality for diagnosis; in our case, it showed a trabecular bony overgrowth (Figure 1), which confirmed the diagnosis. Subungual exostosis is a rare, benign, osteocartilaginous tumor of trabecular bone. The etiology is unknown but is hypothesized to be related to trauma, infection, or activation of a cartilaginous cyst.1,3 The subungual nodule may be asymptomatic or painful. Disruption and elevation of the nail plate is common.4 The differential diagnosis includes amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, fibrokeratoma, osteochondroma, pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, glomus tumor, and verruca vulgaris, among others.5

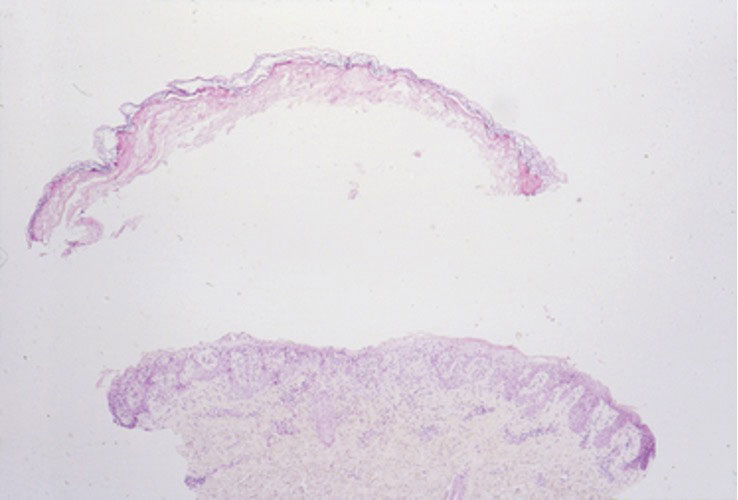

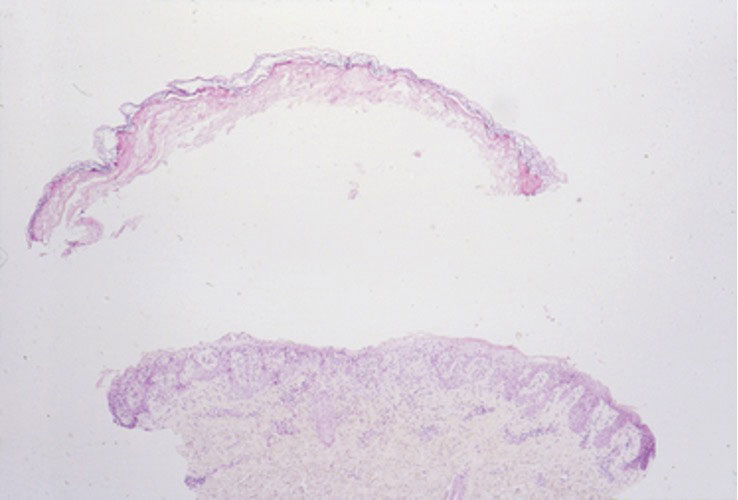

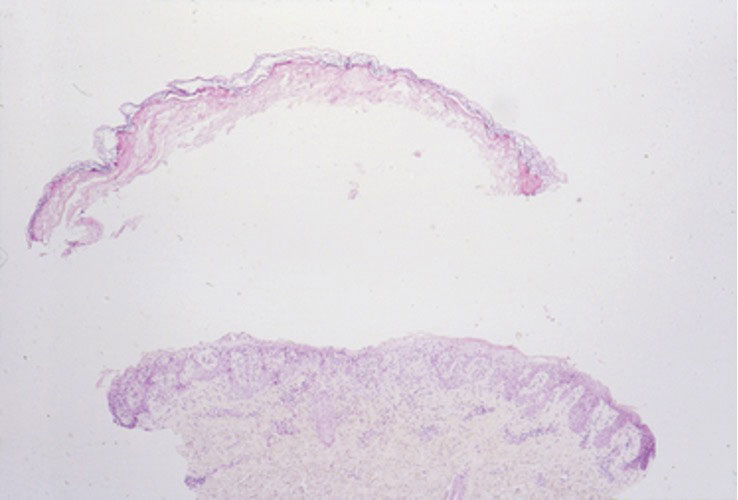

Physical examination demonstrates a firm, fixed, subungual nodule, often with an accompanying nail deformity. Further workup is required to confirm the benign nature of the lesion and exclude nail tumors such as melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Radiography is the gold standard for diagnosis, demonstrating a trabecular bony overgrowth.6 Performing a radiograph as the initial diagnostic test spares the patient from unnecessary procedures such as biopsy or expensive imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging. Early lesions may not demonstrate sufficient bone formation shown on radiography. In these situations, a combination of dermoscopy and histopathologic examination may aid in diagnosis (Figure 2).4 Vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration are the most common findings on dermoscopy (in ascending order).7 Histopathology typically demonstrates a base or stalk of normal-appearing trabecular bone with a fibrocartilage cap.8 However, initial clinical workup via radiography allows for the least-invasive and highest-yield intervention. Clinical suspicion for this condition is important, as it can be diagnosed with noninvasive inexpensive imaging rather than biopsy or more specialized imaging modalities. Appropriate recognition can save young patients from unnecessary and expensive procedures. Treatment typically involves surgical excision; to prevent regrowth, removal of the lesion at the base of the bone is recommended.2

Although amelanotic melanoma also can manifest as a subungual nail tumor, it would be unusual in a young child and would not be expected to show characteristic changes on radiography. A glomus tumor would be painful, is more common on the fingers than on the toes, and typically has a bluish hue.9 Verruca vulgaris can occur subungually but is more common around the nailfold and often has the characteristic dermoscopic finding of thrombosed capillaries. It also would not be expected to show characteristic radiographic findings. Osteochondroma can occur in young patients and can appear clinically similar to subungual exostosis; however, it typically is painful.10

- Pascoal D, Balaco I, Alves C, et al. Subungual exostosis—treatment results with preservation of the nail bed. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020;29:382-386.

- Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257.

- Chiheb S, Slimani Y, Karam R, et al. Subungual exostosis: a case series of 48 patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:475-479.

- Zhang W, Gu L, Fan H, et al. Subungual exostosis with an unusual dermoscopic feature. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:725-726.

- Demirdag HG, Tugrul Ayanoglu B, Akay BN. Dermoscopic features of subungual exostosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E138-E141.

- Tritto M, Mirkin G, Hao X. Subungual exostosis on the right hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2021;111.

- Piccolo V, Argenziano G, Alessandrini AM, et al. Dermoscopy of subungual exostosis: a retrospective study of 10 patients. Dermatology. 2017;233:80-85.

- Lee SK, Jung MS, Lee YH, et al. Two distinctive subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:595-601. doi:10.3113/FAI.2007.0595

- Samaniego E, Crespo A, Sanz A. Key diagnostic features and treatment of subungual glomus tumor. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:875-882.

- Glick S. Subungual osteochondroma of the third toe. Consult.360. 2013;12.

The Diagnosis: Subungual Exostosis

Subungual exostosis should be considered as a possible cause of an exophytic subungual nodule in a young active female. In our patient, the involvement of the great toe was a clue, as the hallux is the most common location of subungual exostosis. The patient’s age and sex also were supportive, as subungual exostosis is most common in female children and adolescents— particularly those who are active, as trauma is thought to play a possible role in development of this benign tumor.1-3 Radiography is the preferred modality for diagnosis; in our case, it showed a trabecular bony overgrowth (Figure 1), which confirmed the diagnosis. Subungual exostosis is a rare, benign, osteocartilaginous tumor of trabecular bone. The etiology is unknown but is hypothesized to be related to trauma, infection, or activation of a cartilaginous cyst.1,3 The subungual nodule may be asymptomatic or painful. Disruption and elevation of the nail plate is common.4 The differential diagnosis includes amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, fibrokeratoma, osteochondroma, pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, glomus tumor, and verruca vulgaris, among others.5

Physical examination demonstrates a firm, fixed, subungual nodule, often with an accompanying nail deformity. Further workup is required to confirm the benign nature of the lesion and exclude nail tumors such as melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Radiography is the gold standard for diagnosis, demonstrating a trabecular bony overgrowth.6 Performing a radiograph as the initial diagnostic test spares the patient from unnecessary procedures such as biopsy or expensive imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging. Early lesions may not demonstrate sufficient bone formation shown on radiography. In these situations, a combination of dermoscopy and histopathologic examination may aid in diagnosis (Figure 2).4 Vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration are the most common findings on dermoscopy (in ascending order).7 Histopathology typically demonstrates a base or stalk of normal-appearing trabecular bone with a fibrocartilage cap.8 However, initial clinical workup via radiography allows for the least-invasive and highest-yield intervention. Clinical suspicion for this condition is important, as it can be diagnosed with noninvasive inexpensive imaging rather than biopsy or more specialized imaging modalities. Appropriate recognition can save young patients from unnecessary and expensive procedures. Treatment typically involves surgical excision; to prevent regrowth, removal of the lesion at the base of the bone is recommended.2

Although amelanotic melanoma also can manifest as a subungual nail tumor, it would be unusual in a young child and would not be expected to show characteristic changes on radiography. A glomus tumor would be painful, is more common on the fingers than on the toes, and typically has a bluish hue.9 Verruca vulgaris can occur subungually but is more common around the nailfold and often has the characteristic dermoscopic finding of thrombosed capillaries. It also would not be expected to show characteristic radiographic findings. Osteochondroma can occur in young patients and can appear clinically similar to subungual exostosis; however, it typically is painful.10

The Diagnosis: Subungual Exostosis

Subungual exostosis should be considered as a possible cause of an exophytic subungual nodule in a young active female. In our patient, the involvement of the great toe was a clue, as the hallux is the most common location of subungual exostosis. The patient’s age and sex also were supportive, as subungual exostosis is most common in female children and adolescents— particularly those who are active, as trauma is thought to play a possible role in development of this benign tumor.1-3 Radiography is the preferred modality for diagnosis; in our case, it showed a trabecular bony overgrowth (Figure 1), which confirmed the diagnosis. Subungual exostosis is a rare, benign, osteocartilaginous tumor of trabecular bone. The etiology is unknown but is hypothesized to be related to trauma, infection, or activation of a cartilaginous cyst.1,3 The subungual nodule may be asymptomatic or painful. Disruption and elevation of the nail plate is common.4 The differential diagnosis includes amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, fibrokeratoma, osteochondroma, pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, glomus tumor, and verruca vulgaris, among others.5

Physical examination demonstrates a firm, fixed, subungual nodule, often with an accompanying nail deformity. Further workup is required to confirm the benign nature of the lesion and exclude nail tumors such as melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Radiography is the gold standard for diagnosis, demonstrating a trabecular bony overgrowth.6 Performing a radiograph as the initial diagnostic test spares the patient from unnecessary procedures such as biopsy or expensive imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging. Early lesions may not demonstrate sufficient bone formation shown on radiography. In these situations, a combination of dermoscopy and histopathologic examination may aid in diagnosis (Figure 2).4 Vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration are the most common findings on dermoscopy (in ascending order).7 Histopathology typically demonstrates a base or stalk of normal-appearing trabecular bone with a fibrocartilage cap.8 However, initial clinical workup via radiography allows for the least-invasive and highest-yield intervention. Clinical suspicion for this condition is important, as it can be diagnosed with noninvasive inexpensive imaging rather than biopsy or more specialized imaging modalities. Appropriate recognition can save young patients from unnecessary and expensive procedures. Treatment typically involves surgical excision; to prevent regrowth, removal of the lesion at the base of the bone is recommended.2

Although amelanotic melanoma also can manifest as a subungual nail tumor, it would be unusual in a young child and would not be expected to show characteristic changes on radiography. A glomus tumor would be painful, is more common on the fingers than on the toes, and typically has a bluish hue.9 Verruca vulgaris can occur subungually but is more common around the nailfold and often has the characteristic dermoscopic finding of thrombosed capillaries. It also would not be expected to show characteristic radiographic findings. Osteochondroma can occur in young patients and can appear clinically similar to subungual exostosis; however, it typically is painful.10

- Pascoal D, Balaco I, Alves C, et al. Subungual exostosis—treatment results with preservation of the nail bed. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020;29:382-386.

- Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257.

- Chiheb S, Slimani Y, Karam R, et al. Subungual exostosis: a case series of 48 patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:475-479.

- Zhang W, Gu L, Fan H, et al. Subungual exostosis with an unusual dermoscopic feature. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:725-726.

- Demirdag HG, Tugrul Ayanoglu B, Akay BN. Dermoscopic features of subungual exostosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E138-E141.

- Tritto M, Mirkin G, Hao X. Subungual exostosis on the right hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2021;111.

- Piccolo V, Argenziano G, Alessandrini AM, et al. Dermoscopy of subungual exostosis: a retrospective study of 10 patients. Dermatology. 2017;233:80-85.

- Lee SK, Jung MS, Lee YH, et al. Two distinctive subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:595-601. doi:10.3113/FAI.2007.0595

- Samaniego E, Crespo A, Sanz A. Key diagnostic features and treatment of subungual glomus tumor. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:875-882.

- Glick S. Subungual osteochondroma of the third toe. Consult.360. 2013;12.

- Pascoal D, Balaco I, Alves C, et al. Subungual exostosis—treatment results with preservation of the nail bed. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020;29:382-386.

- Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257.

- Chiheb S, Slimani Y, Karam R, et al. Subungual exostosis: a case series of 48 patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:475-479.

- Zhang W, Gu L, Fan H, et al. Subungual exostosis with an unusual dermoscopic feature. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:725-726.

- Demirdag HG, Tugrul Ayanoglu B, Akay BN. Dermoscopic features of subungual exostosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E138-E141.

- Tritto M, Mirkin G, Hao X. Subungual exostosis on the right hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2021;111.

- Piccolo V, Argenziano G, Alessandrini AM, et al. Dermoscopy of subungual exostosis: a retrospective study of 10 patients. Dermatology. 2017;233:80-85.

- Lee SK, Jung MS, Lee YH, et al. Two distinctive subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:595-601. doi:10.3113/FAI.2007.0595

- Samaniego E, Crespo A, Sanz A. Key diagnostic features and treatment of subungual glomus tumor. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:875-882.

- Glick S. Subungual osteochondroma of the third toe. Consult.360. 2013;12.

A 13-year-old girl presented to her pediatrician with a small pink bump under the left great toenail of 8 months’ duration that was slowly growing. Months later, she developed an ingrown nail on the same toe, which was treated with partial nail avulsion by the pediatrician. Given continued nail dystrophy and a visible bump under the nail, the patient was referred to dermatology. Physical examination revealed a subungual, flesh-colored, sessile nodule causing distortion of the nail plate on the left great toe with associated intermittent redness and swelling. She denied wearing new shoes or experiencing any pain, pruritus, or purulent drainage or bleeding from the lesion. She reported being physically active and playing tennis.

Study Finds Mace Risk Remains High in Patients with Psoriasis, Dyslipidemia

Over a period of 5 years, the, even after adjusting for covariates, results from a large retrospective study showed.

“It is well-established that psoriasis is an independent risk factor for the development of MACE, with cardiometabolic risk factors being more prevalent and incident among patients with psoriasis,” the study’s first author Ana Ormaza Vera, MD, a dermatology research fellow at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Society for Investigational Dermatology, where the study was presented during a late-breaking abstract session.

Current guidelines from the joint American Academy of Dermatology/National Psoriasis Foundation and the American Academy of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force recommend statins, a lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory therapy, “for patients with psoriasis who have additional risk-enhancing factors, similar to recommendations made for the general population without psoriasis,” she noted. But how the incidence of MACE differs between patients with and without psoriasis while on statin therapy “has not been explored in real-world settings,” she added.

To address this question, the researchers used real-world data from the TriNetX health research network to identify individuals aged 18-90 years with a diagnosis of both psoriasis and lipid disorders who were undergoing treatment with statins. Those with a prior history of MACE were excluded from the analysis. Patients with lipid disorders on statin therapy, but without psoriatic disease, were matched 1:1 by age, sex, race, ethnicity, common risk factors for MACE, and medications shown to reduce MACE risk. The researchers then assessed the cohorts 5 years following their first statin prescription and used the TriNetX analytics tool to calculate the odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI to evaluate the likelihood of MACE in the presence of statin therapy.

Dr. Ormaza Vera and colleagues identified 20,660 patients with psoriasis and 2,768,429 patients without psoriasis who met the criteria for analysis. After propensity score matching, each cohort included 20,660 patients with a mean age of 60 years. During the 5-year observation period, 2725 patients in the psoriasis cohort experienced MACE compared with 2203 patients in the non-psoriasis cohort (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.317-1.488).

“This was an unexpected outcome that challenges the current understanding and highlights the need for further research into tailored treatments for cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients,” Dr. Ormaza Vera told this news organization.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design, the inherent limitations of an observational study, and the use of electronic medical record data.

Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study results, said that the findings imply that there is more than statin use alone to protect someone with psoriasis from having an increased risk for MACE. “This is not really surprising because statin use alone is only part of a prevention strategy in someone with psoriasis who usually has multiple comorbidities,” Dr. Green said. “On the other hand, the study only went out for 5 years and cardiovascular disease is a long accumulating process, so it could also be too early to demonstrate MACE prevention.”

The study was funded by a grant from the American Skin Association. Dr. Ormaza Vera and her coauthors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Over a period of 5 years, the, even after adjusting for covariates, results from a large retrospective study showed.

“It is well-established that psoriasis is an independent risk factor for the development of MACE, with cardiometabolic risk factors being more prevalent and incident among patients with psoriasis,” the study’s first author Ana Ormaza Vera, MD, a dermatology research fellow at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Society for Investigational Dermatology, where the study was presented during a late-breaking abstract session.

Current guidelines from the joint American Academy of Dermatology/National Psoriasis Foundation and the American Academy of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force recommend statins, a lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory therapy, “for patients with psoriasis who have additional risk-enhancing factors, similar to recommendations made for the general population without psoriasis,” she noted. But how the incidence of MACE differs between patients with and without psoriasis while on statin therapy “has not been explored in real-world settings,” she added.

To address this question, the researchers used real-world data from the TriNetX health research network to identify individuals aged 18-90 years with a diagnosis of both psoriasis and lipid disorders who were undergoing treatment with statins. Those with a prior history of MACE were excluded from the analysis. Patients with lipid disorders on statin therapy, but without psoriatic disease, were matched 1:1 by age, sex, race, ethnicity, common risk factors for MACE, and medications shown to reduce MACE risk. The researchers then assessed the cohorts 5 years following their first statin prescription and used the TriNetX analytics tool to calculate the odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI to evaluate the likelihood of MACE in the presence of statin therapy.

Dr. Ormaza Vera and colleagues identified 20,660 patients with psoriasis and 2,768,429 patients without psoriasis who met the criteria for analysis. After propensity score matching, each cohort included 20,660 patients with a mean age of 60 years. During the 5-year observation period, 2725 patients in the psoriasis cohort experienced MACE compared with 2203 patients in the non-psoriasis cohort (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.317-1.488).

“This was an unexpected outcome that challenges the current understanding and highlights the need for further research into tailored treatments for cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients,” Dr. Ormaza Vera told this news organization.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design, the inherent limitations of an observational study, and the use of electronic medical record data.

Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study results, said that the findings imply that there is more than statin use alone to protect someone with psoriasis from having an increased risk for MACE. “This is not really surprising because statin use alone is only part of a prevention strategy in someone with psoriasis who usually has multiple comorbidities,” Dr. Green said. “On the other hand, the study only went out for 5 years and cardiovascular disease is a long accumulating process, so it could also be too early to demonstrate MACE prevention.”

The study was funded by a grant from the American Skin Association. Dr. Ormaza Vera and her coauthors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Over a period of 5 years, the, even after adjusting for covariates, results from a large retrospective study showed.

“It is well-established that psoriasis is an independent risk factor for the development of MACE, with cardiometabolic risk factors being more prevalent and incident among patients with psoriasis,” the study’s first author Ana Ormaza Vera, MD, a dermatology research fellow at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Society for Investigational Dermatology, where the study was presented during a late-breaking abstract session.

Current guidelines from the joint American Academy of Dermatology/National Psoriasis Foundation and the American Academy of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force recommend statins, a lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory therapy, “for patients with psoriasis who have additional risk-enhancing factors, similar to recommendations made for the general population without psoriasis,” she noted. But how the incidence of MACE differs between patients with and without psoriasis while on statin therapy “has not been explored in real-world settings,” she added.

To address this question, the researchers used real-world data from the TriNetX health research network to identify individuals aged 18-90 years with a diagnosis of both psoriasis and lipid disorders who were undergoing treatment with statins. Those with a prior history of MACE were excluded from the analysis. Patients with lipid disorders on statin therapy, but without psoriatic disease, were matched 1:1 by age, sex, race, ethnicity, common risk factors for MACE, and medications shown to reduce MACE risk. The researchers then assessed the cohorts 5 years following their first statin prescription and used the TriNetX analytics tool to calculate the odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI to evaluate the likelihood of MACE in the presence of statin therapy.

Dr. Ormaza Vera and colleagues identified 20,660 patients with psoriasis and 2,768,429 patients without psoriasis who met the criteria for analysis. After propensity score matching, each cohort included 20,660 patients with a mean age of 60 years. During the 5-year observation period, 2725 patients in the psoriasis cohort experienced MACE compared with 2203 patients in the non-psoriasis cohort (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.317-1.488).

“This was an unexpected outcome that challenges the current understanding and highlights the need for further research into tailored treatments for cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients,” Dr. Ormaza Vera told this news organization.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design, the inherent limitations of an observational study, and the use of electronic medical record data.

Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study results, said that the findings imply that there is more than statin use alone to protect someone with psoriasis from having an increased risk for MACE. “This is not really surprising because statin use alone is only part of a prevention strategy in someone with psoriasis who usually has multiple comorbidities,” Dr. Green said. “On the other hand, the study only went out for 5 years and cardiovascular disease is a long accumulating process, so it could also be too early to demonstrate MACE prevention.”

The study was funded by a grant from the American Skin Association. Dr. Ormaza Vera and her coauthors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

FROM SID 2024

Low-Field MRIs

Recently, “low field” MRIs have been in the news, with the promise that they’ll be safer and easier. People can go in them with their cell phones, car keys in pockets, no ear plugs needed for the noise, etc. They’re cheaper to build and can be plugged into a standard outlet.

That’s all well and good, but what about accuracy and image quality?

That’s a big question. Even proponents of the technology say it’s not as good as what we see with 3T MRI, so they’re trying to compensate by using AI and other software protocols to enhance the pictures. Allegedly it looks good, but so far only healthy volunteers have been scanned. How will it do with a small low-grade glioma or other subtle (but important) findings? We don’t know yet.

Personally, I think having to give up your iPhone and car keys for an hour, and put in foam ear plugs, are small trade-offs to get an accurate diagnosis.

Of course, I’m also approaching this as someone who deals with brain imaging. Maybe for other structures, like a knee, that kind of detail isn’t as necessary (or maybe it is. I’m definitely not in that field).

So, as with so many things that make it into the popular press, they likely have potential, but are still not ready for prime time.

This sort of stuff always gets my office phones ringing. Patients see a blurb about it on the news or Facebook and assume it’s available now, so they want one. They seem to think the new MRI is like Bones McCoy’s tricorder. I take the scanner off my belt, wave it over them, and the answer comes up on the screen. The fact that the unit still weighs over a ton is hidden at the bottom of the blurb, if it’s even mentioned at all.

There’s also the likelihood that this sort of thing is going to be taken to the public, in the same way carotid Dopplers have been. Marketed to the worried well with celebrity endorsements and taglines like “see what your doctor won’t look for.” Of course, MRIs are chock full of things like nonspecific white matter changes, disc bulges, tiny meningiomas, and a host of other incidental findings that cause panic in cyberchondriacs. Who then call us.

But that’s another story.

I understand that for some parts of the world a comparatively inexpensive, transportable, MRI that requires less shielding and power is a HUGE deal. Its availability can make the difference between life and death.

I’m not knocking the technology. I’m sure it will be useful. But, like so much in medicine, it’s not here yet.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Recently, “low field” MRIs have been in the news, with the promise that they’ll be safer and easier. People can go in them with their cell phones, car keys in pockets, no ear plugs needed for the noise, etc. They’re cheaper to build and can be plugged into a standard outlet.

That’s all well and good, but what about accuracy and image quality?

That’s a big question. Even proponents of the technology say it’s not as good as what we see with 3T MRI, so they’re trying to compensate by using AI and other software protocols to enhance the pictures. Allegedly it looks good, but so far only healthy volunteers have been scanned. How will it do with a small low-grade glioma or other subtle (but important) findings? We don’t know yet.

Personally, I think having to give up your iPhone and car keys for an hour, and put in foam ear plugs, are small trade-offs to get an accurate diagnosis.

Of course, I’m also approaching this as someone who deals with brain imaging. Maybe for other structures, like a knee, that kind of detail isn’t as necessary (or maybe it is. I’m definitely not in that field).

So, as with so many things that make it into the popular press, they likely have potential, but are still not ready for prime time.

This sort of stuff always gets my office phones ringing. Patients see a blurb about it on the news or Facebook and assume it’s available now, so they want one. They seem to think the new MRI is like Bones McCoy’s tricorder. I take the scanner off my belt, wave it over them, and the answer comes up on the screen. The fact that the unit still weighs over a ton is hidden at the bottom of the blurb, if it’s even mentioned at all.

There’s also the likelihood that this sort of thing is going to be taken to the public, in the same way carotid Dopplers have been. Marketed to the worried well with celebrity endorsements and taglines like “see what your doctor won’t look for.” Of course, MRIs are chock full of things like nonspecific white matter changes, disc bulges, tiny meningiomas, and a host of other incidental findings that cause panic in cyberchondriacs. Who then call us.

But that’s another story.

I understand that for some parts of the world a comparatively inexpensive, transportable, MRI that requires less shielding and power is a HUGE deal. Its availability can make the difference between life and death.

I’m not knocking the technology. I’m sure it will be useful. But, like so much in medicine, it’s not here yet.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Recently, “low field” MRIs have been in the news, with the promise that they’ll be safer and easier. People can go in them with their cell phones, car keys in pockets, no ear plugs needed for the noise, etc. They’re cheaper to build and can be plugged into a standard outlet.

That’s all well and good, but what about accuracy and image quality?

That’s a big question. Even proponents of the technology say it’s not as good as what we see with 3T MRI, so they’re trying to compensate by using AI and other software protocols to enhance the pictures. Allegedly it looks good, but so far only healthy volunteers have been scanned. How will it do with a small low-grade glioma or other subtle (but important) findings? We don’t know yet.

Personally, I think having to give up your iPhone and car keys for an hour, and put in foam ear plugs, are small trade-offs to get an accurate diagnosis.

Of course, I’m also approaching this as someone who deals with brain imaging. Maybe for other structures, like a knee, that kind of detail isn’t as necessary (or maybe it is. I’m definitely not in that field).

So, as with so many things that make it into the popular press, they likely have potential, but are still not ready for prime time.

This sort of stuff always gets my office phones ringing. Patients see a blurb about it on the news or Facebook and assume it’s available now, so they want one. They seem to think the new MRI is like Bones McCoy’s tricorder. I take the scanner off my belt, wave it over them, and the answer comes up on the screen. The fact that the unit still weighs over a ton is hidden at the bottom of the blurb, if it’s even mentioned at all.

There’s also the likelihood that this sort of thing is going to be taken to the public, in the same way carotid Dopplers have been. Marketed to the worried well with celebrity endorsements and taglines like “see what your doctor won’t look for.” Of course, MRIs are chock full of things like nonspecific white matter changes, disc bulges, tiny meningiomas, and a host of other incidental findings that cause panic in cyberchondriacs. Who then call us.

But that’s another story.

I understand that for some parts of the world a comparatively inexpensive, transportable, MRI that requires less shielding and power is a HUGE deal. Its availability can make the difference between life and death.

I’m not knocking the technology. I’m sure it will be useful. But, like so much in medicine, it’s not here yet.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Aquatic Antagonists: Seaweed Dermatitis (Lyngbya majuscula)

Aquatic Antagonists: Seaweed Dermatitis (Lyngbya majuscula)

The filamentous cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula causes irritant contact dermatitis in beachgoers, fishers, and divers in tropical and subtropical marine environments worldwide.1 If fragments of L majuscula lodge in swimmers’ bathing suits, the toxins can become trapped against the skin and cause seaweed dermatitis.2 With climate change resulting in warmer oceans and more extreme storms, L majuscula blooms likely will become more frequent and widespread, thereby increasing the risk for human exposure.3,4 Herein, we describe the irritants that lead to dermatitis, clinical presentation, and prevention and management of seaweed dermatitis.

Identifying Features and Distribution of Plant

Lyngbya majuscula belongs to the family Oscillatoriaceae; these cyanobacteria grow as filaments and exhibit slow oscillating movements. Commonly referred to as blanketweed or mermaid’s hair due to its appearance, L majuscula grows fine hairlike clumps resembling a mass of olive-colored matted hair.1 Its thin filaments are 10- to 30-cm long and vary in color from red to white to brown.5 Microscopically, a rouleauxlike arrangement of discs provides the structure of each filament.6

First identified in Hawaii in 1912, L majuscula was not associated with seaweed dermatitis or dermatotoxicity by the medical community until the first outbreak occurred in Oahu in 1958, though fishermen and beachgoers previously had recognized a relationship between this particular seaweed and skin irritation.5,7 The first reporting included 125 confirmed cases, with many more mild unreported cases suspected.6 Now reported in about 100 locations worldwide, seaweed dermatitis outbreaks have occurred in Australia; Okinawa, Japan; Florida; and the Hawaiian and Marshall islands.1,2

Exposure to Seaweed

Lyngbya majuscula produces more than 70 biologically active compounds that irritate the skin, eyes, and respiratory system.2,8 It grows in marine and estuarine environments attached to seagrass, sand, and bedrock at depths of up to 30 m. Warm waters and maximal sunlight provide optimal growth conditions for L majuscula; therefore, the greatest risk for exposure occurs in the Northern and Southern hemispheres in the 1- to 2-month period following their summer solstices.5 Runoff during heavy rainfall, which is rich in soil extracts such as phosphorous, iron, and organic carbon, stimulates L majuscula growth and contributes to increased algal blooms.4

Dermatitis and Irritants

The dermatoxins Lyngbyatoxin A (LA) and debromoaplysiatoxin (DAT) cause the inflammatory and necrotic appearance of seaweed dermatitis.1,2,5,8 Lyngbyatoxin A is an indole alkaloid that is closely related to telocidin B, a poisonous compound associated with Streptomyces bacteria.9 Sampling of L majuscula and extraction of the dermatoxin, along with human and animal studies, confirmed DAT irritates the skin and induces dermatitis.5,6Stylocheilus longicauda (sea hare) feeds on L majuscula and contains isolates of DAT in its digestive tract.

Samples of L majuscula taken from several Hawaiian Islands where seaweed dermatitis outbreaks have occurred were examined for differences in toxicities via 6-hour patch tests on human skin.6 The samples obtained from the windward side of Oahu contained DAT and aplysiatoxin, while those obtained from the leeward side and Kahala Beach primarily contained LA. Although DAT and LA are vastly different in their molecular structures, testing elicited the same biologic response and induced the same level of skin irritation.6 Interestingly, not all strands of L majuscula produced LA and DAT and caused seaweed dermatitis; those that did lead to irritation were more red in color than nontoxic blooms.5,9

Cutaneous Manifestations

Seaweed dermatitis resembles chemical and thermal burns, ranging from a mild skin rash to severe contact dermatitis with itchy, swollen, ulcerated lesions.1,7 Patients typically develop a burning or itching sensation beneath their bathing suit or wetsuit that progresses to an erythematous papulovesicular eruption 2 to 24 hours after exposure.2,6 Within a week, vesicles and bullae desquamate, leaving behind tender erosions.1,2,6,8 Inframammary lesions are common in females and scrotal swelling in males.1,6 There is no known association between length of time spent in the water and severity of symptoms.5

Most reactions to L majuscula occur from exposure in the water; however, particles that become aerosolized during strong winds or storms can cause seaweed dermatitis on the face. Inhalation of L majuscula may lead to mucous membrane ulceration and pulmonary edema.1,5,6 Noncutaneous manifestations of seaweed dermatitis include headache, fatigue, and swelling of the eyes, nose, and throat (Figures 1 and 2).1,5

Prevention and Management

To prevent seaweed dermatitis, avoid swimming in ocean water during L majuscula blooms,10 which frequently occur following the summer solstices in the Northern and Southern hemispheres.5 The National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science Harmful Algae Bloom Monitoring System provides real-time access to algae bloom locations.11 Although this monitoring system is not specific to L majuscula, it may be helpful in determining where potential blooms are. Wearing protective clothing such as coveralls may benefit individuals who enter the water during blooms, but it does not guarantee protection.10

magnification ×40). Photograph courtesy of Scott Norton, MD, MPH, MSc (Washington, DC).

Currently, there is no treatment for seaweed dermatitis, but symptom management may reduce discomfort and pain. Washing affected skin with soap and water within an hour of exposure may help reduce the severity of seaweed dermatitis, though studies have shown mixed results.6,7 Application of cool compresses and soothing ointments (eg, calamine) provide symptomatic relief and promote healing.7 The dermatitis typically self-resolves within 1 week.

- Werner K, Marquart L, Norton S. Lyngbya dermatitis (toxic seaweed dermatitis). Int J Dermatol. 2011;51:59-62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05042.x

- Osborne N, Shaw G. Dermatitis associated with exposure to a marine cyanobacterium during recreational water exposure. BMC Dermatol. 2008;8:5. doi:10.1186/1471-5945-8-5

- Hays G, Richardson A, Robinson C. Climate change and marine plankton. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:337-344. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.004

- Albert S, O’Neil J, Udy J, et al. Blooms of the cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula in costal Queensland, Australia: disparate sites, common factors. Mar Pollut Bull. 2004;51:428-437. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.10.016

- Osborne N, Webb P, Shaw G. The toxins of Lyngbya majuscula and their human and ecological health effects. Environ Int. 2001;27:381-392. doi:10.1016/s0160-4120(01)00098-8

- Izumi A, Moore R. Seaweed ( Lyngbya majuscula ) dermatitis . Clin Dermatol . 1987;5:92-100. doi:10.1016/s0738-081x(87)80014-7

- Grauer F, Arnold H. Seaweed dermatitis: first report of a dermatitis-producing marine alga. Arch Dermatol. 1961; 84:720-732. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580170014003

- Taylor M, Stahl-Timmins W, Redshaw C, et al. Toxic alkaloids in Lyngbya majuscula and related tropical marine cyanobacteria. Harmful Algae . 2014;31:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.hal.2013.09.003

- Cardellina J, Marner F, Moore R. Seaweed dermatitis: structure of lyngbyatoxin A. Science. 1979;204:193-195. doi:10.1126/science.107586

- Osborne N. Occupational dermatitis caused by Lyngbya majuscule in Australia. Int J Dermatol . 2012;5:122-123. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04455.x

- Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring System. National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://coastalscience.noaa.gov/research/stressor-impacts-mitigation/hab-monitoring-system/

The filamentous cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula causes irritant contact dermatitis in beachgoers, fishers, and divers in tropical and subtropical marine environments worldwide.1 If fragments of L majuscula lodge in swimmers’ bathing suits, the toxins can become trapped against the skin and cause seaweed dermatitis.2 With climate change resulting in warmer oceans and more extreme storms, L majuscula blooms likely will become more frequent and widespread, thereby increasing the risk for human exposure.3,4 Herein, we describe the irritants that lead to dermatitis, clinical presentation, and prevention and management of seaweed dermatitis.

Identifying Features and Distribution of Plant

Lyngbya majuscula belongs to the family Oscillatoriaceae; these cyanobacteria grow as filaments and exhibit slow oscillating movements. Commonly referred to as blanketweed or mermaid’s hair due to its appearance, L majuscula grows fine hairlike clumps resembling a mass of olive-colored matted hair.1 Its thin filaments are 10- to 30-cm long and vary in color from red to white to brown.5 Microscopically, a rouleauxlike arrangement of discs provides the structure of each filament.6

First identified in Hawaii in 1912, L majuscula was not associated with seaweed dermatitis or dermatotoxicity by the medical community until the first outbreak occurred in Oahu in 1958, though fishermen and beachgoers previously had recognized a relationship between this particular seaweed and skin irritation.5,7 The first reporting included 125 confirmed cases, with many more mild unreported cases suspected.6 Now reported in about 100 locations worldwide, seaweed dermatitis outbreaks have occurred in Australia; Okinawa, Japan; Florida; and the Hawaiian and Marshall islands.1,2

Exposure to Seaweed

Lyngbya majuscula produces more than 70 biologically active compounds that irritate the skin, eyes, and respiratory system.2,8 It grows in marine and estuarine environments attached to seagrass, sand, and bedrock at depths of up to 30 m. Warm waters and maximal sunlight provide optimal growth conditions for L majuscula; therefore, the greatest risk for exposure occurs in the Northern and Southern hemispheres in the 1- to 2-month period following their summer solstices.5 Runoff during heavy rainfall, which is rich in soil extracts such as phosphorous, iron, and organic carbon, stimulates L majuscula growth and contributes to increased algal blooms.4

Dermatitis and Irritants

The dermatoxins Lyngbyatoxin A (LA) and debromoaplysiatoxin (DAT) cause the inflammatory and necrotic appearance of seaweed dermatitis.1,2,5,8 Lyngbyatoxin A is an indole alkaloid that is closely related to telocidin B, a poisonous compound associated with Streptomyces bacteria.9 Sampling of L majuscula and extraction of the dermatoxin, along with human and animal studies, confirmed DAT irritates the skin and induces dermatitis.5,6Stylocheilus longicauda (sea hare) feeds on L majuscula and contains isolates of DAT in its digestive tract.

Samples of L majuscula taken from several Hawaiian Islands where seaweed dermatitis outbreaks have occurred were examined for differences in toxicities via 6-hour patch tests on human skin.6 The samples obtained from the windward side of Oahu contained DAT and aplysiatoxin, while those obtained from the leeward side and Kahala Beach primarily contained LA. Although DAT and LA are vastly different in their molecular structures, testing elicited the same biologic response and induced the same level of skin irritation.6 Interestingly, not all strands of L majuscula produced LA and DAT and caused seaweed dermatitis; those that did lead to irritation were more red in color than nontoxic blooms.5,9

Cutaneous Manifestations

Seaweed dermatitis resembles chemical and thermal burns, ranging from a mild skin rash to severe contact dermatitis with itchy, swollen, ulcerated lesions.1,7 Patients typically develop a burning or itching sensation beneath their bathing suit or wetsuit that progresses to an erythematous papulovesicular eruption 2 to 24 hours after exposure.2,6 Within a week, vesicles and bullae desquamate, leaving behind tender erosions.1,2,6,8 Inframammary lesions are common in females and scrotal swelling in males.1,6 There is no known association between length of time spent in the water and severity of symptoms.5