User login

Photodermatoses: Exploring Clinical Presentations, Causative Factors, Differential Diagnoses, and Treatment Strategies

Photodermatoses: Exploring Clinical Presentations, Causative Factors, Differential Diagnoses, and Treatment Strategies

Photosensitivity refers to clinical manifestations arising from exposure to sunlight. Photodermatoses encompass a group of skin diseases caused by varying degrees of radiation exposure, including UV radiation and visible light. Photodermatoses can be categorized into 5 main types: primary, exogenous, photoexacerbated, metabolic, and genetic.1 The clinical features of photodermatoses vary depending on the underlying cause but often include pruritic flares, wheals, or dermatitis on sun-exposed areas of the skin.2 While photodermatoses typically are not life threatening, they can greatly impact patients’ quality of life. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of photoprotection and sunlight avoidance to patients as preventive measures against the manifestations of these skin diseases. Furthermore, we present a case of photocontact dermatitis (PCD) and discuss common causative agents, diagnostic mimickers, and treatment options.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the neck and under the eyes of 6 days’ duration. The rash was intermittently pruritic but otherwise asymptomatic. The patient reported that she had spent extensive time on the golf course the day of the rash onset and noted that a similar rash had occurred one other time 2 to 3 months prior, also following a prolonged period on the golf course. She had been using over-the-counter fexofenadine 180 mg and over-the-counter lidocaine spray for symptom relief.

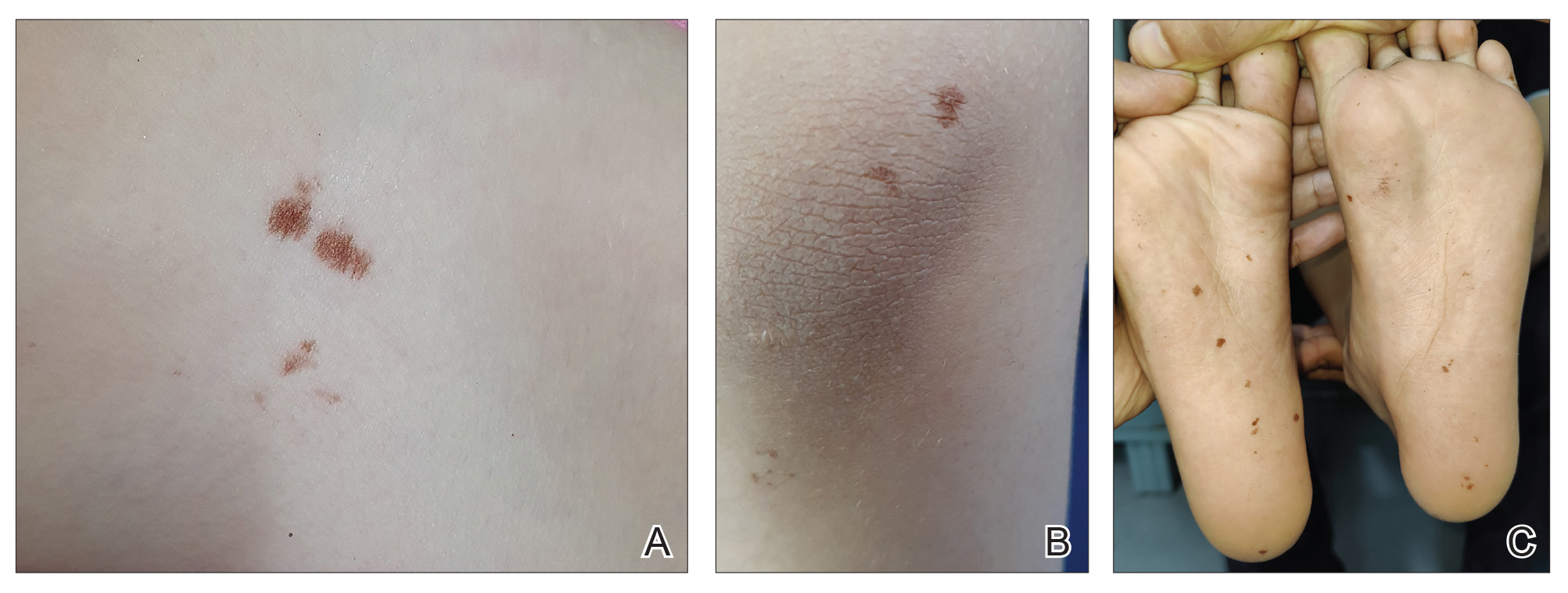

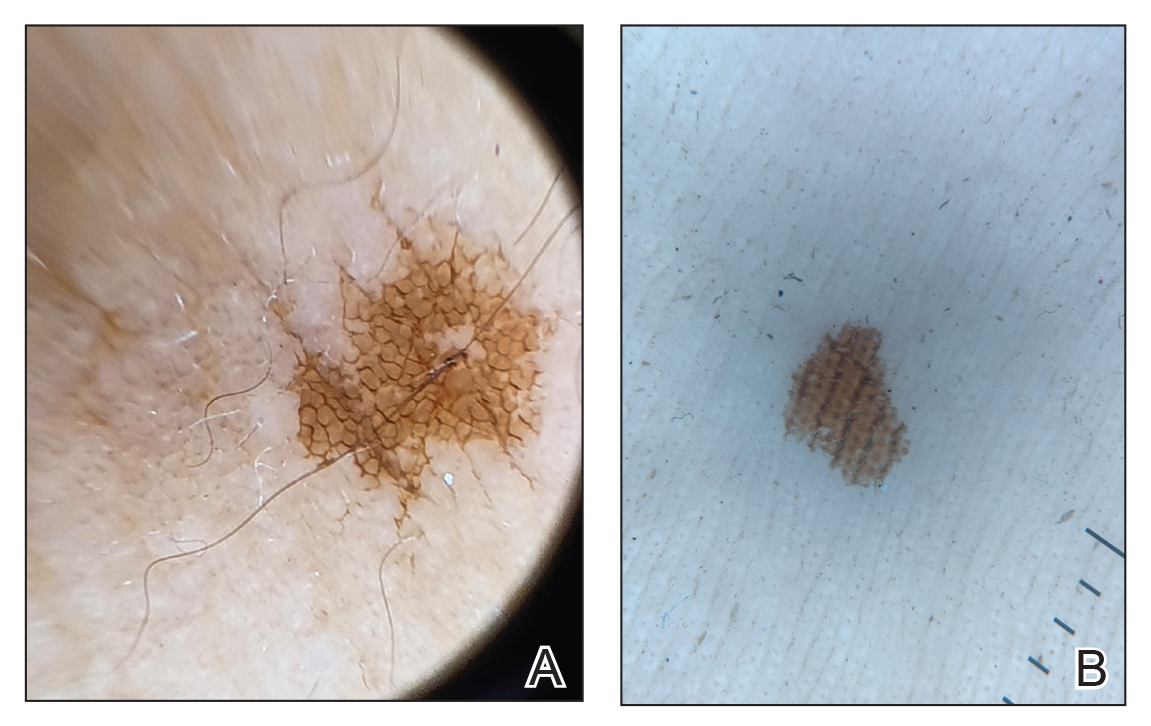

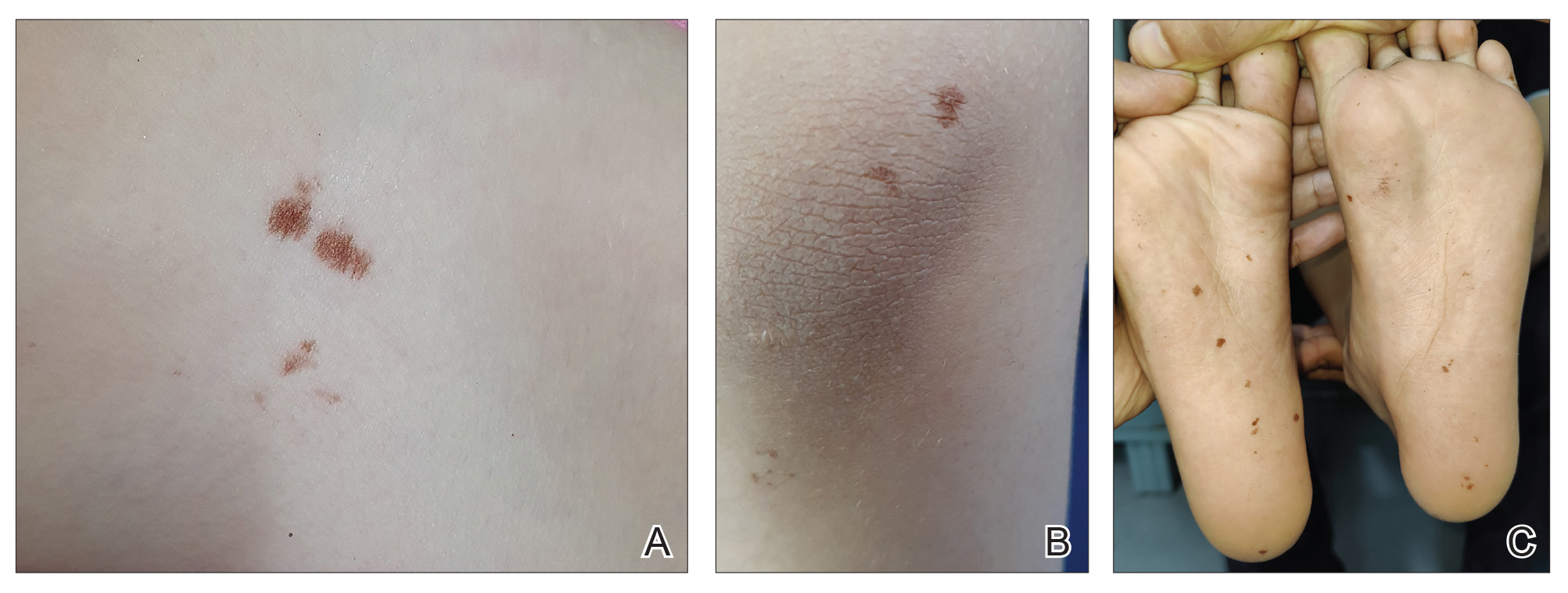

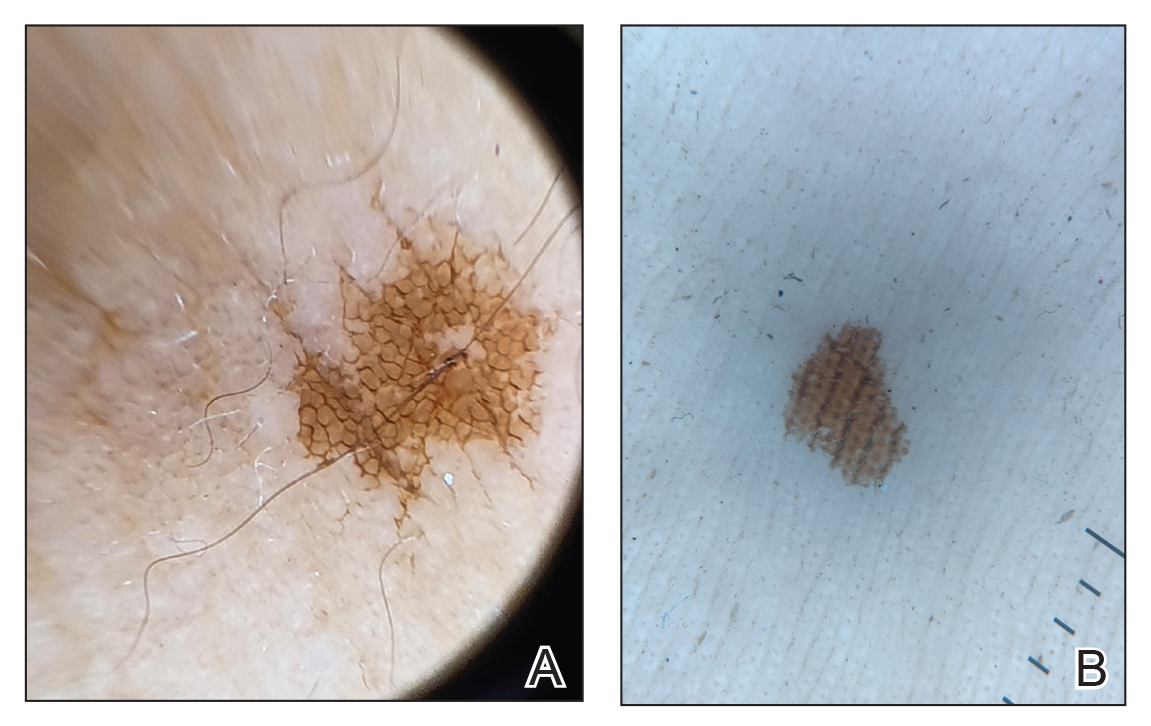

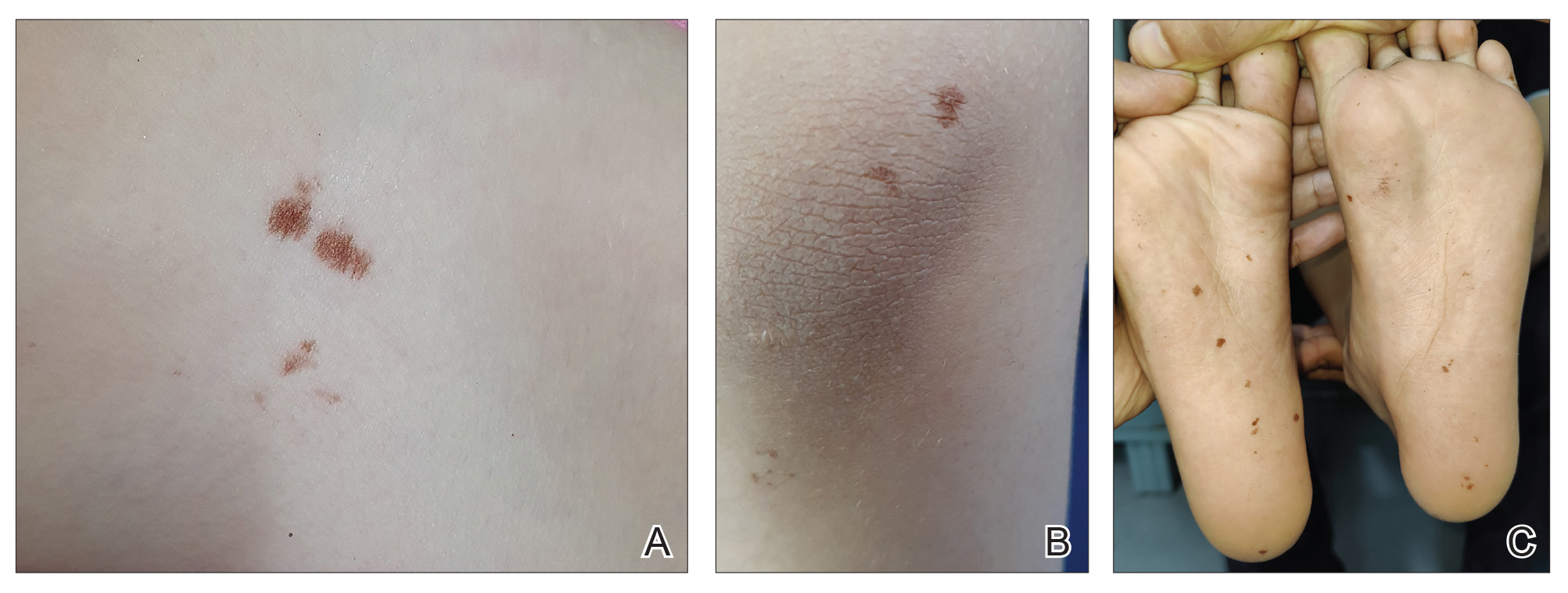

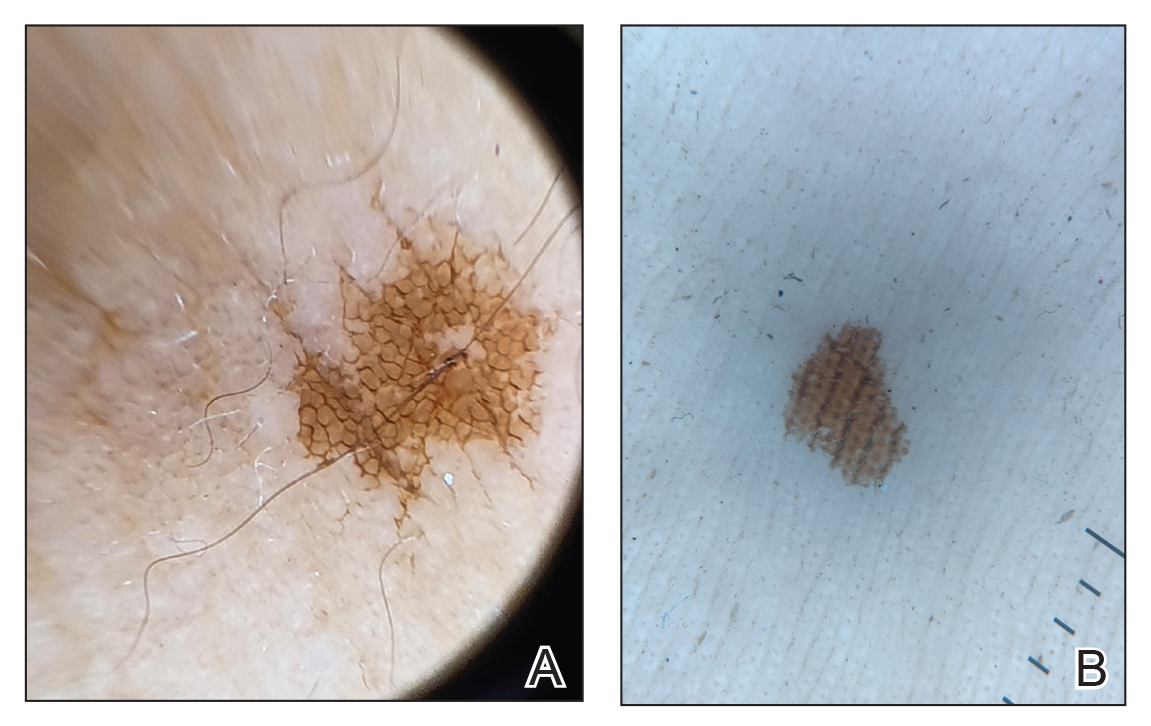

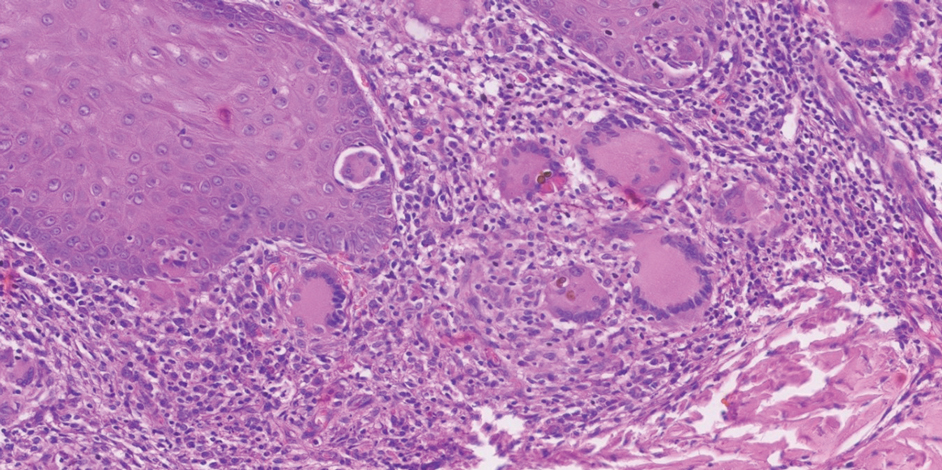

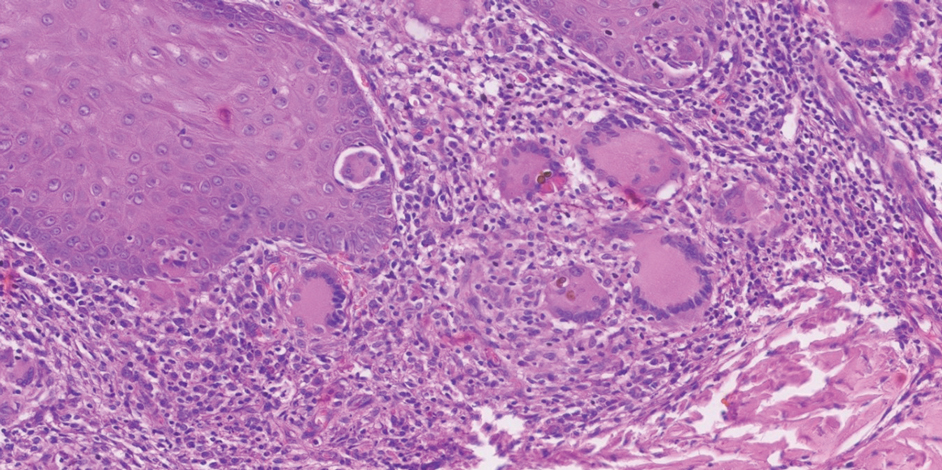

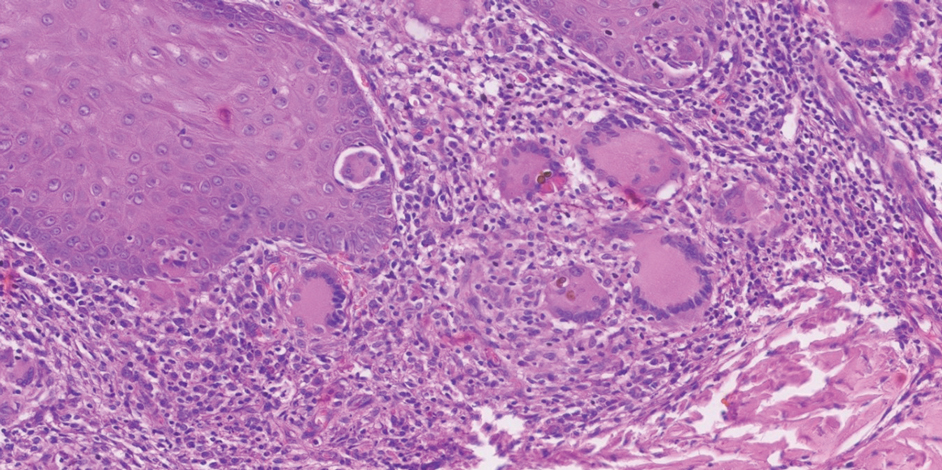

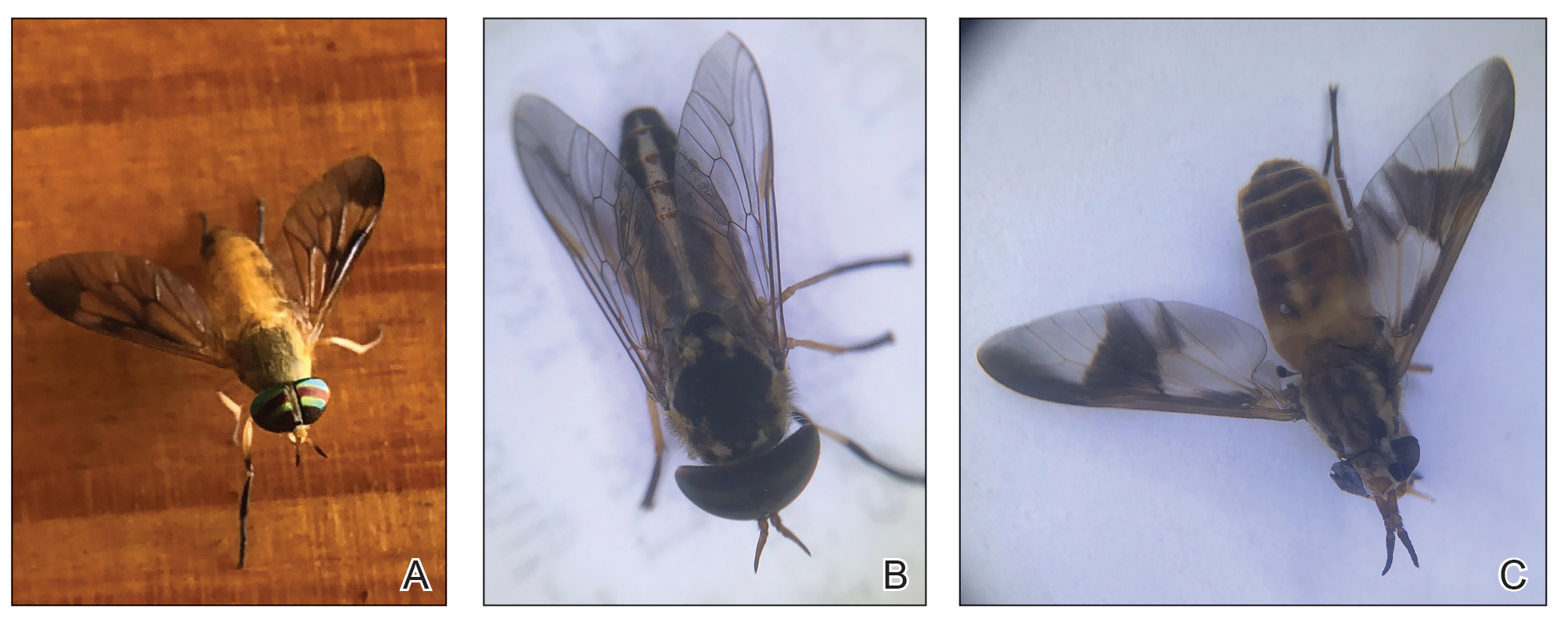

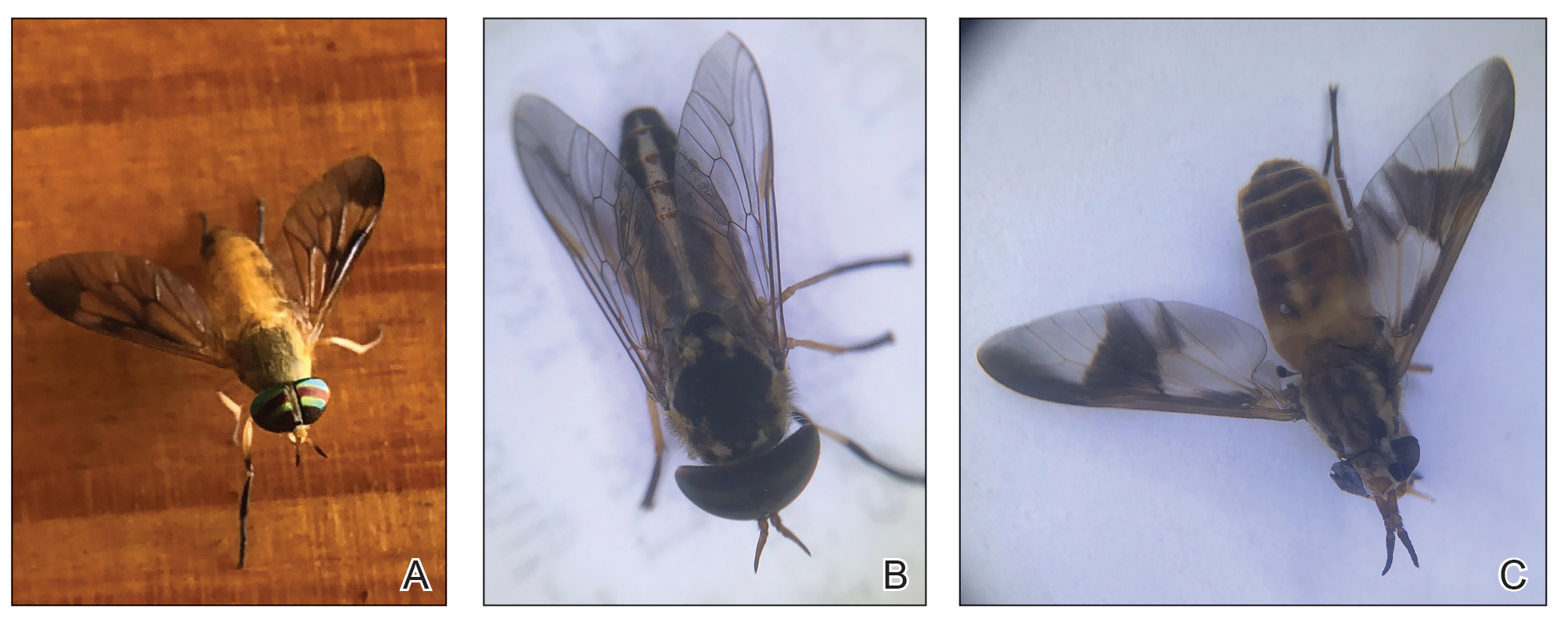

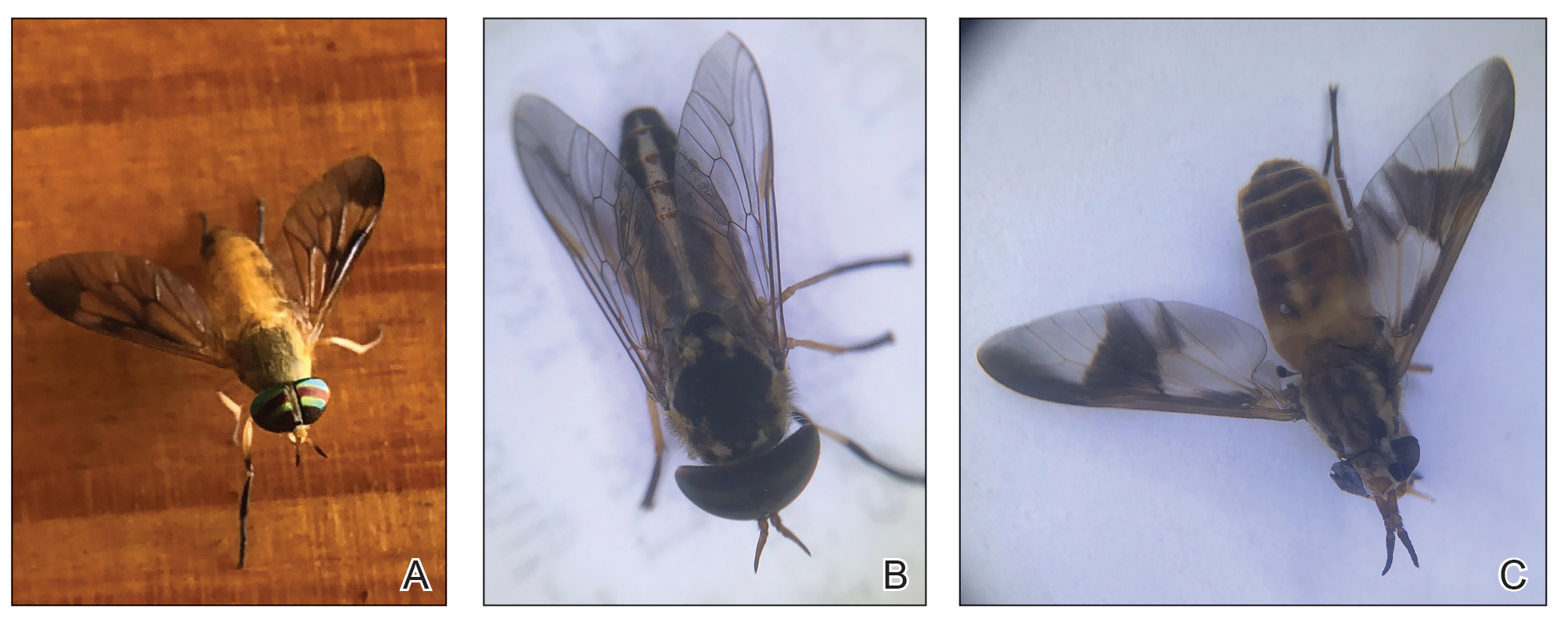

Upon physical examination, erythematous patches were appreciated in a photodistributed pattern on the arms, legs, neck, face, and chest—areas that were not covered by clothing (Figures 1-3). Due to the distribution and morphology of the erythematous patches along with clinical course of onset following exposure to various environmental agents including pesticides, herbicides, oak, and pollen, a diagnosis of PCD was made. The patient was prescribed hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, and methylprednisolone in addition to the antihistamine. Improvement was noted after 3 days with complete resolution of the skin manifestations. She was counseled on wearing clothing with a universal protection factor rating of 50+ when on the golf course and when sun exposure is expected for an extended period of time.

Causative Agents

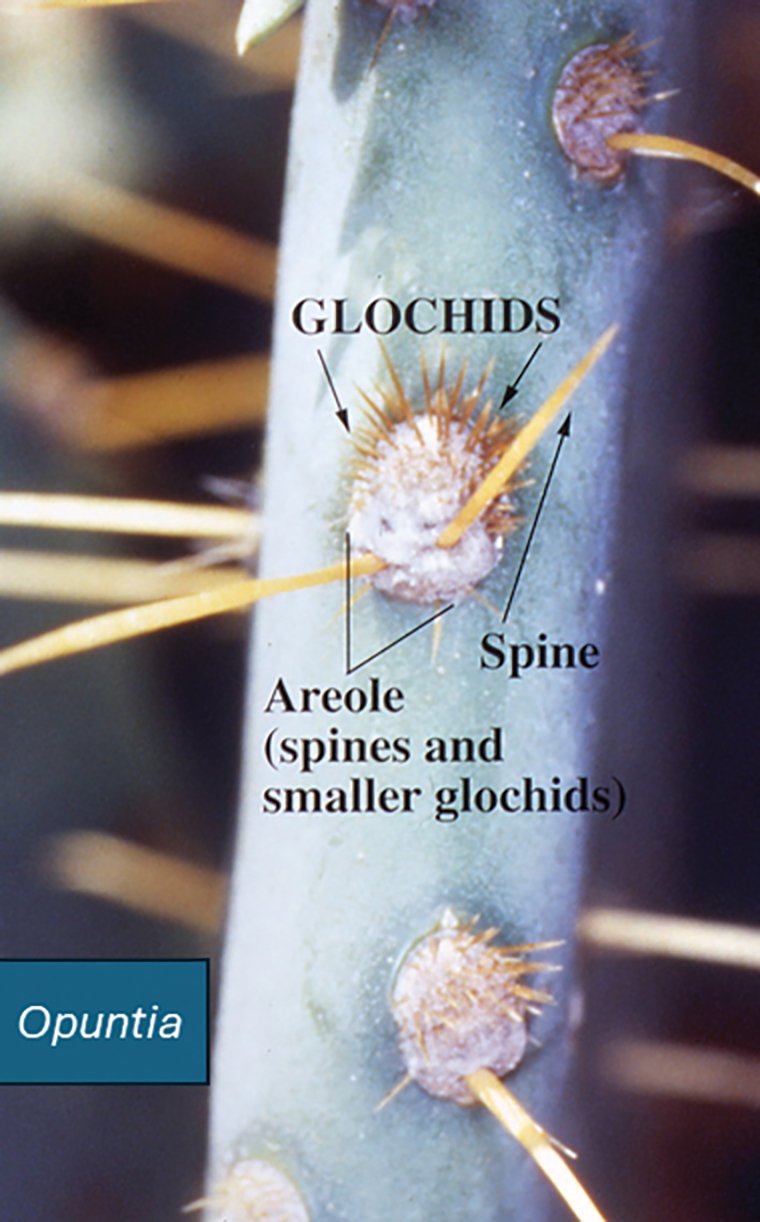

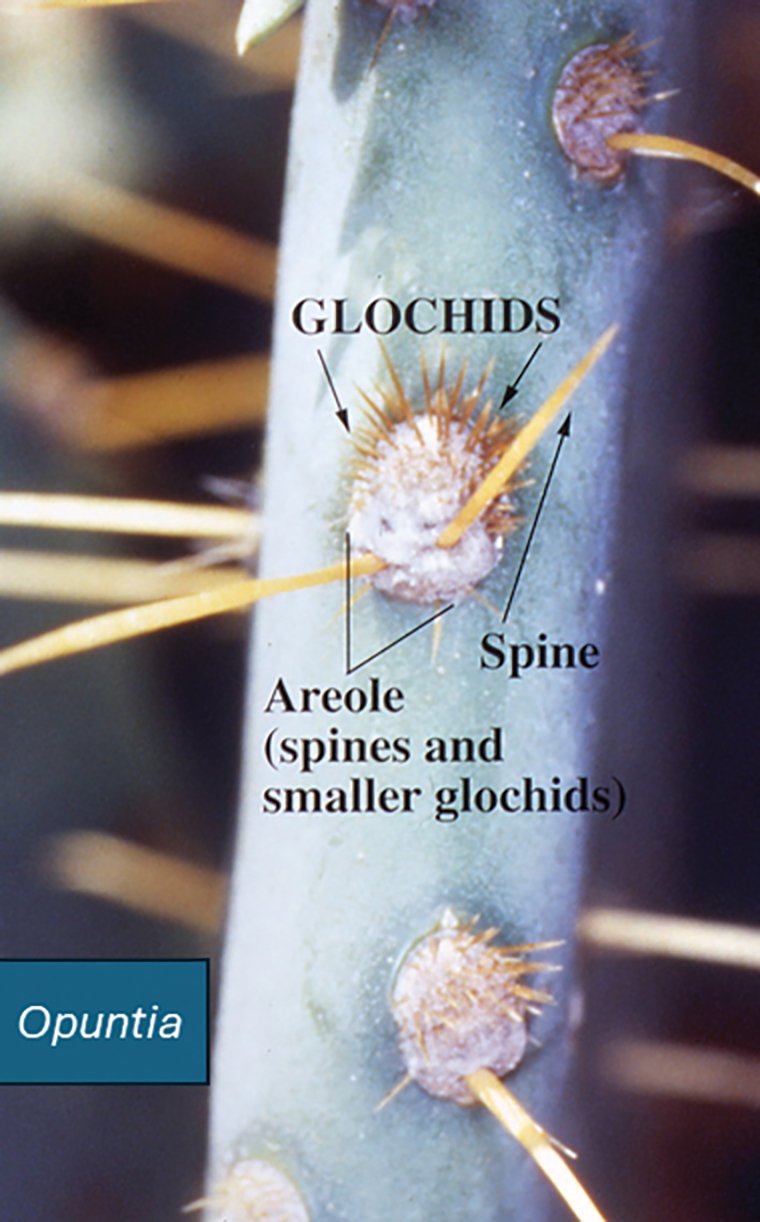

Photodermatoses are caused by antigenic substances that lead to photosensitization acquired by either contact or oral ingestion with subsequent sensitization to UV radiation. Halogenated salicylanilide, fenticlor, hexachlorophene, bithionol and, in rare cases, sunscreens, have been reported as triggers.3 In a study performed in 2010, sunscreens, antimicrobial agents, medications, fragrances, plants/plant derivatives, and pesticides were the most commonly reported offending agents listed from highest to lowest frequency. Of the antimicrobial agents, fenticlor, a topical antimicrobial and antifungal that is now mostly used in veterinary medicine, was the most common culprit, causing 60% of cases.4,5

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of photodermatoses vary depending upon the specific type of reaction. Examples of primary photodermatoses include polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) and solar urticaria. The cardinal symptoms of PMLE consist of severely pruritic skin lesions that can have macular, papular, papulovesicular, urticarial, multiformelike, and plaquelike variants that develop hours to days after sun exposure.3 Conversely, solar urticaria commonly develops more abruptly, with indurated plaques and wheals appearing on the arms and neck within 30 minutes of sun exposure. The lesions typically resolve within 24 hours.1

Examples of the exogenous subtype include drug-induced photosensitivity, PCD, and pseudoporphyria, with the common clinical presentation of eruption following contact with the causative agent. Drug-induced photosensitivity primarily manifests as a severe sunburnlike rash commonly caused by systemic drugs such as tetracyclines. Photocontact dermatitis is limited to sun-exposed areas of the skin and is caused by a reactive irritant such as chemicals or topical creams. Pseudoporphyria, usually caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can manifest with skin fragility and subepidermal blisters.6

Photoexacerbated photodermatoses encompass a variety of conditions ranging from hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma to autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM). Common clinical features of these diseases include photodistributed erythema, often involving the cheeks, upper back, and anterior neck. Photo-exposed areas of the dorsal hands also are commonplace for both SLE and DM. Clinical manifestations of PCD are limited to sun-exposed areas of the body, specifically those that come into contact with photoallergic triggers.3 Manifestations of PCD can include pruritic eczematous eruptions resembling those of contact dermatitis 1 to 2 days after sun exposure.1

Photocontact dermatitis represents a specific sensitization via contact or oral ingestion acquired prior to sunlight exposure. It can be broken down into 2 distinct subtypes: photoallergic and photoirritant dermatitis, dependent on whether an allergic or irritant reaction is invoked.2 Plants are known to be a common trigger of photoirritant reactions, while extrinsic triggers include psoralens and medications such as tetracycline antibiotics or sulfonamides. Photoallergic reactions commonly can be caused by topical application of sunscreen or medications, namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.2 Clinical manifestations that may point to photoirritant dermatitis include a photodistributed eruption and classic morphology showing erythema and edema with bullae present in severe cases. These can be contrasted with the clinical manifestations of photoallergic reactions, which usually do not correlate to sun-exposed areas and consist of a monomorphous distribution pattern similar to that of eczema. Although there are distinguishing features of both subtypes of PCD, the overlapping clinical features can mimic those of solar urticaria, PMLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and more systemic conditions such as SLE and DM.7

Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with a broad range of cutaneous manifestations.8 Exposure to UV radiation is a common trigger for lupus and has the propensity to cause a malar (butterfly) rash that covers the cheeks and nasal bridge but classically spares the nasolabial folds. The rash may display confluent reddish-purple discoloration with papules and/or edema and typically is present at diagnosis in 40% to 52% of patients with SLE.8 Discoid lupus erythematosus, one of the most common cutaneous forms of lupus, manifests with various-sized coin-shaped plaques with adherent follicular hyperkeratosis and plugging. These lesions usually develop on the face, scalp, and ears but also may appear in non–sun-exposed areas.8 Dermatomyositis can manifest with photodistributed erythema affecting classic areas such as the upper back (shawl sign), anterior neck and upper chest (V-sign), and a malar rash similar to that seen in lupus, though DM classically does not spare the nasolabial folds.8,9

Because SLE and DM manifest with photodistributed rashes, it can be difficult to distinguish them from the classic symptoms of photoirritant dermatitis.9 Thus, it is imperative that providers have a high clinical index of suspicion when dealing with patients of similar presentations, as the treatment regimens vastly differ. Approaching the patient with a thorough medical history review, review of systems, biopsy (including immunofluorescence), and appropriate laboratory workup may aid in excluding more complex differential diagnoses such as SLE and DM.

Metabolic and genetic photodermatoses are more rare but can include conditions such as porphyria cutanea tarda and xeroderma pigmentosum, both of which demonstrate fragile skin, slow wound healing, and bullae on photo-exposed skin.1 Although the manifestations can be similar in these systemic conditions, they are caused by very different mechanisms. Porphyria cutanea tarda is caused by deficiencies in enzymes involved in the heme synthesis pathway, whereas xeroderma pigmentosum is caused by an alteration in DNA repair mechanisms.7

Prevalence and the Need for Standardized Testing

Most practicing dermatologists see cases of PCD due to its multiple causative agents; however, little is known about its overall prevalence. The incidence of PCD is fairly low in the general population, but this may be due to its clinical diagnosis, which excludes diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing.10 While the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis also is fairly unknown, the inception of testing modalities has allowed statistics to be drawn. Research conducted in the United States has disclosed that the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis in individuals with a history of a prior photosensitivity eruption is approximately 10% to 20%.10 The development of guidelines and a registry for photopatch testing would aid in a greater understanding of the incidence of PCD and overall consistency of diagnosis.7 Regardless of this lack of consensus, these conditions can be properly managed and prevented if recognized clinically, while newer testing modalities would allow for confirmation of the diagnosis. It is important that any patient presenting with a history of photosensitivity be seen as a candidate for photopatch testing, especially today, as the general population is increasingly exposed to new chemicals entering the market and new social trends.7,10

Diagnosis and Treatment

It is important to consider a detailed history, including the timing, location, duration, family history, and seasonal variation of suspected photodermatoses. A thorough skin examination that takes note of the specific areas affected, morphology, and involvement of the rash or lesions can be helpful.1 Further diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing can be employed and is especially important when distinguishing photoallergy from phototoxicity.11 Phototesting involves exposing the patient’s skin to different doses of UVA, UVB, and visible light, followed by an immediate clinical reading of the results and then a delayed reading conducted after 24 hours.1 Photopatch testing involves the application of 2 sets of identical photoallergens to prepped skin (typically cleansed with isopropyl alcohol), with one being irradiated with UVA after 24 hours and one serving as the control. A clinical assessment is conducted at 24 hours and repeated 7 days later.1 In photodermatoses, a visible reaction can be appreciated on the treatment arm while the control arm remains clear. When both sides reveal a visible reaction, this is more indicative of a light-independent allergic contact dermatitis.1

Photodermatoses occur only if there has been a specific sensitization, and therefore it is important to work with the patient to discover any new products that have been introduced into their regimen. Though many photosensitizers in personal care products (eg, antiseptics in soap and topical creams) have been discontinued, certain allergenic ingredients may remain.12 It also is important to note that sensitization to a substance that previously was not a known allergen for a particular patient can occur later in life. Avoiding further sun exposure can rapidly improve the dermatitis, and it is possible for spontaneous remission without further intervention; however, as photoallergic reactions can cause severely pruritic skin lesions, the mainstay of symptomatic treatment consists of topical corticosteroids. Oral and topical antihistamines may help alleviate the pruritus but should not be heavily relied on as this can lead to medication resistance and diminishing efficacy.3 Use of short-term oral steroids also may be considered for rapid improvement of symptoms when the patient is in moderate distress and there are no contraindications. By identifying a temporal association between the introduction of new products and the emergence of dermatitis, it may be possible to identify the causative agent. The patient should promptly discontinue the suspected agent and remain under close observation by the clinician for any further eruptions, especially following additional sun exposure.

Prevention Strategies

In the case of PCD, prevention is key. As PCD indicates a photoallergy, it is important to inform patients that the allergy will persist for a lifetime, much like in contact dermatitis; therefore, the causative agent should be avoided indefinitely.3 Patients with PCD should make intentional efforts to read ingredient lists when purchasing new personal care products to ensure they do not contain the specific causative allergen if one has been identified. Further steps should be taken to ensure proper photoprotection, including use of dense clothing and sunscreen with UVA and UVB filters (broad spectrum).3 It has also been suggested that utilizing sunscreen with ectoin, an amino acid–derived molecule, may result in increased protection against UVA-induced photodermatoses.13

Final Thoughts

Photodermatoses are a group of skin diseases caused by exposure to UV radiation. Photocontact dermatitis/photoallergy is a form of allergic contact dermatitis that results from exposure to an allergen, whether topical, oral, or environmental. The allergen is activated by exposure to UV radiation to sensitize the allergic response, resulting in a rash characterized by confluent erythematous patches or plaques, papular vesicles, and rarely blisters.3 Photocontact dermatitis, although rare, is an important differential diagnosis to consider when the presenting rash is restricted to sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the arms, legs, neck, and face. Diagnosis remains a challenge; however, new testing modalities such as photopatch testing may open the door for further confirmation and aid in proper diagnosis leading to earlier treatment times for patients. It is recommended that the clinician and patient work together to identify the possible causative agent to prevent further eruptions.

- Santoro FA, Lim HW. Update on photodermatoses. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:229-238.

- Gimenez-Arnau A, Maurer M, De La Cuadra J, et al. Immediate contact skin reactions, an update of contact urticaria, contact urticaria syndrome and protein contact dermatitis—“a never ending story.” Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:555-562.

- Lehmann P, Schwarz T. Photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:135-141.

- Victor FC, Cohen DE, Soter NA. A 20-year analysis of previous and emerging allergens that elicit photoallergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:605-610.

- Fenticlor (Code 65671). National Cancer Institute EVS Explore. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://ncithesaurus.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/ConceptReport.jsp?dictionary=NCIThesaurus&ns=ncit&code=C65671

- Elmets CA. Photosensitivity disorders (photodermatoses): clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. UptoDate. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/photosensitivity-disorders-photodermatoses-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-treatment

- Snyder M, Turrentine JE, Cruz PD Jr. Photocontact dermatitis and its clinical mimics: an overview for the allergist. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:32-40.

- Cooper EE, Pisano CE, Shapiro SC. Cutaneous manifestations of “lupus”: systemic lupus erythematosus and beyond. Int J Rheumatol. 2021;2021:6610509.

- Christopher-Stine L, Amato AA, Vleugels RA. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in adults. UptoDate. Updated March 3, 2025. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-differential-diagnosis-of-dermatomyositis-and-polymyositis-in-adults?search=Diagnosis%20and%20differential%20diagnosis%20of%20dermatomyositis%20and%20polymyositis%20in%20adults&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- Gonçalo M. Photopatch testing. In: Johansen J, Frosch P, Lepoittevin JP, eds. Contact Dermatitis. Springer; 2011:519-531.

- Enta T. Dermacase. Contact photodermatitis. Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:577,586-587.

- Duteil L, Queille-Roussel C, Aladren S, et al. Prevention of polymophic light eruption afforded by a very high broad-spectrum protection sunscreen containing ectoin. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1603-1613.

Photosensitivity refers to clinical manifestations arising from exposure to sunlight. Photodermatoses encompass a group of skin diseases caused by varying degrees of radiation exposure, including UV radiation and visible light. Photodermatoses can be categorized into 5 main types: primary, exogenous, photoexacerbated, metabolic, and genetic.1 The clinical features of photodermatoses vary depending on the underlying cause but often include pruritic flares, wheals, or dermatitis on sun-exposed areas of the skin.2 While photodermatoses typically are not life threatening, they can greatly impact patients’ quality of life. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of photoprotection and sunlight avoidance to patients as preventive measures against the manifestations of these skin diseases. Furthermore, we present a case of photocontact dermatitis (PCD) and discuss common causative agents, diagnostic mimickers, and treatment options.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the neck and under the eyes of 6 days’ duration. The rash was intermittently pruritic but otherwise asymptomatic. The patient reported that she had spent extensive time on the golf course the day of the rash onset and noted that a similar rash had occurred one other time 2 to 3 months prior, also following a prolonged period on the golf course. She had been using over-the-counter fexofenadine 180 mg and over-the-counter lidocaine spray for symptom relief.

Upon physical examination, erythematous patches were appreciated in a photodistributed pattern on the arms, legs, neck, face, and chest—areas that were not covered by clothing (Figures 1-3). Due to the distribution and morphology of the erythematous patches along with clinical course of onset following exposure to various environmental agents including pesticides, herbicides, oak, and pollen, a diagnosis of PCD was made. The patient was prescribed hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, and methylprednisolone in addition to the antihistamine. Improvement was noted after 3 days with complete resolution of the skin manifestations. She was counseled on wearing clothing with a universal protection factor rating of 50+ when on the golf course and when sun exposure is expected for an extended period of time.

Causative Agents

Photodermatoses are caused by antigenic substances that lead to photosensitization acquired by either contact or oral ingestion with subsequent sensitization to UV radiation. Halogenated salicylanilide, fenticlor, hexachlorophene, bithionol and, in rare cases, sunscreens, have been reported as triggers.3 In a study performed in 2010, sunscreens, antimicrobial agents, medications, fragrances, plants/plant derivatives, and pesticides were the most commonly reported offending agents listed from highest to lowest frequency. Of the antimicrobial agents, fenticlor, a topical antimicrobial and antifungal that is now mostly used in veterinary medicine, was the most common culprit, causing 60% of cases.4,5

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of photodermatoses vary depending upon the specific type of reaction. Examples of primary photodermatoses include polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) and solar urticaria. The cardinal symptoms of PMLE consist of severely pruritic skin lesions that can have macular, papular, papulovesicular, urticarial, multiformelike, and plaquelike variants that develop hours to days after sun exposure.3 Conversely, solar urticaria commonly develops more abruptly, with indurated plaques and wheals appearing on the arms and neck within 30 minutes of sun exposure. The lesions typically resolve within 24 hours.1

Examples of the exogenous subtype include drug-induced photosensitivity, PCD, and pseudoporphyria, with the common clinical presentation of eruption following contact with the causative agent. Drug-induced photosensitivity primarily manifests as a severe sunburnlike rash commonly caused by systemic drugs such as tetracyclines. Photocontact dermatitis is limited to sun-exposed areas of the skin and is caused by a reactive irritant such as chemicals or topical creams. Pseudoporphyria, usually caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can manifest with skin fragility and subepidermal blisters.6

Photoexacerbated photodermatoses encompass a variety of conditions ranging from hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma to autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM). Common clinical features of these diseases include photodistributed erythema, often involving the cheeks, upper back, and anterior neck. Photo-exposed areas of the dorsal hands also are commonplace for both SLE and DM. Clinical manifestations of PCD are limited to sun-exposed areas of the body, specifically those that come into contact with photoallergic triggers.3 Manifestations of PCD can include pruritic eczematous eruptions resembling those of contact dermatitis 1 to 2 days after sun exposure.1

Photocontact dermatitis represents a specific sensitization via contact or oral ingestion acquired prior to sunlight exposure. It can be broken down into 2 distinct subtypes: photoallergic and photoirritant dermatitis, dependent on whether an allergic or irritant reaction is invoked.2 Plants are known to be a common trigger of photoirritant reactions, while extrinsic triggers include psoralens and medications such as tetracycline antibiotics or sulfonamides. Photoallergic reactions commonly can be caused by topical application of sunscreen or medications, namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.2 Clinical manifestations that may point to photoirritant dermatitis include a photodistributed eruption and classic morphology showing erythema and edema with bullae present in severe cases. These can be contrasted with the clinical manifestations of photoallergic reactions, which usually do not correlate to sun-exposed areas and consist of a monomorphous distribution pattern similar to that of eczema. Although there are distinguishing features of both subtypes of PCD, the overlapping clinical features can mimic those of solar urticaria, PMLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and more systemic conditions such as SLE and DM.7

Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with a broad range of cutaneous manifestations.8 Exposure to UV radiation is a common trigger for lupus and has the propensity to cause a malar (butterfly) rash that covers the cheeks and nasal bridge but classically spares the nasolabial folds. The rash may display confluent reddish-purple discoloration with papules and/or edema and typically is present at diagnosis in 40% to 52% of patients with SLE.8 Discoid lupus erythematosus, one of the most common cutaneous forms of lupus, manifests with various-sized coin-shaped plaques with adherent follicular hyperkeratosis and plugging. These lesions usually develop on the face, scalp, and ears but also may appear in non–sun-exposed areas.8 Dermatomyositis can manifest with photodistributed erythema affecting classic areas such as the upper back (shawl sign), anterior neck and upper chest (V-sign), and a malar rash similar to that seen in lupus, though DM classically does not spare the nasolabial folds.8,9

Because SLE and DM manifest with photodistributed rashes, it can be difficult to distinguish them from the classic symptoms of photoirritant dermatitis.9 Thus, it is imperative that providers have a high clinical index of suspicion when dealing with patients of similar presentations, as the treatment regimens vastly differ. Approaching the patient with a thorough medical history review, review of systems, biopsy (including immunofluorescence), and appropriate laboratory workup may aid in excluding more complex differential diagnoses such as SLE and DM.

Metabolic and genetic photodermatoses are more rare but can include conditions such as porphyria cutanea tarda and xeroderma pigmentosum, both of which demonstrate fragile skin, slow wound healing, and bullae on photo-exposed skin.1 Although the manifestations can be similar in these systemic conditions, they are caused by very different mechanisms. Porphyria cutanea tarda is caused by deficiencies in enzymes involved in the heme synthesis pathway, whereas xeroderma pigmentosum is caused by an alteration in DNA repair mechanisms.7

Prevalence and the Need for Standardized Testing

Most practicing dermatologists see cases of PCD due to its multiple causative agents; however, little is known about its overall prevalence. The incidence of PCD is fairly low in the general population, but this may be due to its clinical diagnosis, which excludes diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing.10 While the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis also is fairly unknown, the inception of testing modalities has allowed statistics to be drawn. Research conducted in the United States has disclosed that the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis in individuals with a history of a prior photosensitivity eruption is approximately 10% to 20%.10 The development of guidelines and a registry for photopatch testing would aid in a greater understanding of the incidence of PCD and overall consistency of diagnosis.7 Regardless of this lack of consensus, these conditions can be properly managed and prevented if recognized clinically, while newer testing modalities would allow for confirmation of the diagnosis. It is important that any patient presenting with a history of photosensitivity be seen as a candidate for photopatch testing, especially today, as the general population is increasingly exposed to new chemicals entering the market and new social trends.7,10

Diagnosis and Treatment

It is important to consider a detailed history, including the timing, location, duration, family history, and seasonal variation of suspected photodermatoses. A thorough skin examination that takes note of the specific areas affected, morphology, and involvement of the rash or lesions can be helpful.1 Further diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing can be employed and is especially important when distinguishing photoallergy from phototoxicity.11 Phototesting involves exposing the patient’s skin to different doses of UVA, UVB, and visible light, followed by an immediate clinical reading of the results and then a delayed reading conducted after 24 hours.1 Photopatch testing involves the application of 2 sets of identical photoallergens to prepped skin (typically cleansed with isopropyl alcohol), with one being irradiated with UVA after 24 hours and one serving as the control. A clinical assessment is conducted at 24 hours and repeated 7 days later.1 In photodermatoses, a visible reaction can be appreciated on the treatment arm while the control arm remains clear. When both sides reveal a visible reaction, this is more indicative of a light-independent allergic contact dermatitis.1

Photodermatoses occur only if there has been a specific sensitization, and therefore it is important to work with the patient to discover any new products that have been introduced into their regimen. Though many photosensitizers in personal care products (eg, antiseptics in soap and topical creams) have been discontinued, certain allergenic ingredients may remain.12 It also is important to note that sensitization to a substance that previously was not a known allergen for a particular patient can occur later in life. Avoiding further sun exposure can rapidly improve the dermatitis, and it is possible for spontaneous remission without further intervention; however, as photoallergic reactions can cause severely pruritic skin lesions, the mainstay of symptomatic treatment consists of topical corticosteroids. Oral and topical antihistamines may help alleviate the pruritus but should not be heavily relied on as this can lead to medication resistance and diminishing efficacy.3 Use of short-term oral steroids also may be considered for rapid improvement of symptoms when the patient is in moderate distress and there are no contraindications. By identifying a temporal association between the introduction of new products and the emergence of dermatitis, it may be possible to identify the causative agent. The patient should promptly discontinue the suspected agent and remain under close observation by the clinician for any further eruptions, especially following additional sun exposure.

Prevention Strategies

In the case of PCD, prevention is key. As PCD indicates a photoallergy, it is important to inform patients that the allergy will persist for a lifetime, much like in contact dermatitis; therefore, the causative agent should be avoided indefinitely.3 Patients with PCD should make intentional efforts to read ingredient lists when purchasing new personal care products to ensure they do not contain the specific causative allergen if one has been identified. Further steps should be taken to ensure proper photoprotection, including use of dense clothing and sunscreen with UVA and UVB filters (broad spectrum).3 It has also been suggested that utilizing sunscreen with ectoin, an amino acid–derived molecule, may result in increased protection against UVA-induced photodermatoses.13

Final Thoughts

Photodermatoses are a group of skin diseases caused by exposure to UV radiation. Photocontact dermatitis/photoallergy is a form of allergic contact dermatitis that results from exposure to an allergen, whether topical, oral, or environmental. The allergen is activated by exposure to UV radiation to sensitize the allergic response, resulting in a rash characterized by confluent erythematous patches or plaques, papular vesicles, and rarely blisters.3 Photocontact dermatitis, although rare, is an important differential diagnosis to consider when the presenting rash is restricted to sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the arms, legs, neck, and face. Diagnosis remains a challenge; however, new testing modalities such as photopatch testing may open the door for further confirmation and aid in proper diagnosis leading to earlier treatment times for patients. It is recommended that the clinician and patient work together to identify the possible causative agent to prevent further eruptions.

Photosensitivity refers to clinical manifestations arising from exposure to sunlight. Photodermatoses encompass a group of skin diseases caused by varying degrees of radiation exposure, including UV radiation and visible light. Photodermatoses can be categorized into 5 main types: primary, exogenous, photoexacerbated, metabolic, and genetic.1 The clinical features of photodermatoses vary depending on the underlying cause but often include pruritic flares, wheals, or dermatitis on sun-exposed areas of the skin.2 While photodermatoses typically are not life threatening, they can greatly impact patients’ quality of life. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of photoprotection and sunlight avoidance to patients as preventive measures against the manifestations of these skin diseases. Furthermore, we present a case of photocontact dermatitis (PCD) and discuss common causative agents, diagnostic mimickers, and treatment options.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the neck and under the eyes of 6 days’ duration. The rash was intermittently pruritic but otherwise asymptomatic. The patient reported that she had spent extensive time on the golf course the day of the rash onset and noted that a similar rash had occurred one other time 2 to 3 months prior, also following a prolonged period on the golf course. She had been using over-the-counter fexofenadine 180 mg and over-the-counter lidocaine spray for symptom relief.

Upon physical examination, erythematous patches were appreciated in a photodistributed pattern on the arms, legs, neck, face, and chest—areas that were not covered by clothing (Figures 1-3). Due to the distribution and morphology of the erythematous patches along with clinical course of onset following exposure to various environmental agents including pesticides, herbicides, oak, and pollen, a diagnosis of PCD was made. The patient was prescribed hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, and methylprednisolone in addition to the antihistamine. Improvement was noted after 3 days with complete resolution of the skin manifestations. She was counseled on wearing clothing with a universal protection factor rating of 50+ when on the golf course and when sun exposure is expected for an extended period of time.

Causative Agents

Photodermatoses are caused by antigenic substances that lead to photosensitization acquired by either contact or oral ingestion with subsequent sensitization to UV radiation. Halogenated salicylanilide, fenticlor, hexachlorophene, bithionol and, in rare cases, sunscreens, have been reported as triggers.3 In a study performed in 2010, sunscreens, antimicrobial agents, medications, fragrances, plants/plant derivatives, and pesticides were the most commonly reported offending agents listed from highest to lowest frequency. Of the antimicrobial agents, fenticlor, a topical antimicrobial and antifungal that is now mostly used in veterinary medicine, was the most common culprit, causing 60% of cases.4,5

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of photodermatoses vary depending upon the specific type of reaction. Examples of primary photodermatoses include polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) and solar urticaria. The cardinal symptoms of PMLE consist of severely pruritic skin lesions that can have macular, papular, papulovesicular, urticarial, multiformelike, and plaquelike variants that develop hours to days after sun exposure.3 Conversely, solar urticaria commonly develops more abruptly, with indurated plaques and wheals appearing on the arms and neck within 30 minutes of sun exposure. The lesions typically resolve within 24 hours.1

Examples of the exogenous subtype include drug-induced photosensitivity, PCD, and pseudoporphyria, with the common clinical presentation of eruption following contact with the causative agent. Drug-induced photosensitivity primarily manifests as a severe sunburnlike rash commonly caused by systemic drugs such as tetracyclines. Photocontact dermatitis is limited to sun-exposed areas of the skin and is caused by a reactive irritant such as chemicals or topical creams. Pseudoporphyria, usually caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can manifest with skin fragility and subepidermal blisters.6

Photoexacerbated photodermatoses encompass a variety of conditions ranging from hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma to autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM). Common clinical features of these diseases include photodistributed erythema, often involving the cheeks, upper back, and anterior neck. Photo-exposed areas of the dorsal hands also are commonplace for both SLE and DM. Clinical manifestations of PCD are limited to sun-exposed areas of the body, specifically those that come into contact with photoallergic triggers.3 Manifestations of PCD can include pruritic eczematous eruptions resembling those of contact dermatitis 1 to 2 days after sun exposure.1

Photocontact dermatitis represents a specific sensitization via contact or oral ingestion acquired prior to sunlight exposure. It can be broken down into 2 distinct subtypes: photoallergic and photoirritant dermatitis, dependent on whether an allergic or irritant reaction is invoked.2 Plants are known to be a common trigger of photoirritant reactions, while extrinsic triggers include psoralens and medications such as tetracycline antibiotics or sulfonamides. Photoallergic reactions commonly can be caused by topical application of sunscreen or medications, namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.2 Clinical manifestations that may point to photoirritant dermatitis include a photodistributed eruption and classic morphology showing erythema and edema with bullae present in severe cases. These can be contrasted with the clinical manifestations of photoallergic reactions, which usually do not correlate to sun-exposed areas and consist of a monomorphous distribution pattern similar to that of eczema. Although there are distinguishing features of both subtypes of PCD, the overlapping clinical features can mimic those of solar urticaria, PMLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and more systemic conditions such as SLE and DM.7

Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with a broad range of cutaneous manifestations.8 Exposure to UV radiation is a common trigger for lupus and has the propensity to cause a malar (butterfly) rash that covers the cheeks and nasal bridge but classically spares the nasolabial folds. The rash may display confluent reddish-purple discoloration with papules and/or edema and typically is present at diagnosis in 40% to 52% of patients with SLE.8 Discoid lupus erythematosus, one of the most common cutaneous forms of lupus, manifests with various-sized coin-shaped plaques with adherent follicular hyperkeratosis and plugging. These lesions usually develop on the face, scalp, and ears but also may appear in non–sun-exposed areas.8 Dermatomyositis can manifest with photodistributed erythema affecting classic areas such as the upper back (shawl sign), anterior neck and upper chest (V-sign), and a malar rash similar to that seen in lupus, though DM classically does not spare the nasolabial folds.8,9

Because SLE and DM manifest with photodistributed rashes, it can be difficult to distinguish them from the classic symptoms of photoirritant dermatitis.9 Thus, it is imperative that providers have a high clinical index of suspicion when dealing with patients of similar presentations, as the treatment regimens vastly differ. Approaching the patient with a thorough medical history review, review of systems, biopsy (including immunofluorescence), and appropriate laboratory workup may aid in excluding more complex differential diagnoses such as SLE and DM.

Metabolic and genetic photodermatoses are more rare but can include conditions such as porphyria cutanea tarda and xeroderma pigmentosum, both of which demonstrate fragile skin, slow wound healing, and bullae on photo-exposed skin.1 Although the manifestations can be similar in these systemic conditions, they are caused by very different mechanisms. Porphyria cutanea tarda is caused by deficiencies in enzymes involved in the heme synthesis pathway, whereas xeroderma pigmentosum is caused by an alteration in DNA repair mechanisms.7

Prevalence and the Need for Standardized Testing

Most practicing dermatologists see cases of PCD due to its multiple causative agents; however, little is known about its overall prevalence. The incidence of PCD is fairly low in the general population, but this may be due to its clinical diagnosis, which excludes diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing.10 While the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis also is fairly unknown, the inception of testing modalities has allowed statistics to be drawn. Research conducted in the United States has disclosed that the incidence of photoallergic contact dermatitis in individuals with a history of a prior photosensitivity eruption is approximately 10% to 20%.10 The development of guidelines and a registry for photopatch testing would aid in a greater understanding of the incidence of PCD and overall consistency of diagnosis.7 Regardless of this lack of consensus, these conditions can be properly managed and prevented if recognized clinically, while newer testing modalities would allow for confirmation of the diagnosis. It is important that any patient presenting with a history of photosensitivity be seen as a candidate for photopatch testing, especially today, as the general population is increasingly exposed to new chemicals entering the market and new social trends.7,10

Diagnosis and Treatment

It is important to consider a detailed history, including the timing, location, duration, family history, and seasonal variation of suspected photodermatoses. A thorough skin examination that takes note of the specific areas affected, morphology, and involvement of the rash or lesions can be helpful.1 Further diagnostic testing such as phototesting and photopatch testing can be employed and is especially important when distinguishing photoallergy from phototoxicity.11 Phototesting involves exposing the patient’s skin to different doses of UVA, UVB, and visible light, followed by an immediate clinical reading of the results and then a delayed reading conducted after 24 hours.1 Photopatch testing involves the application of 2 sets of identical photoallergens to prepped skin (typically cleansed with isopropyl alcohol), with one being irradiated with UVA after 24 hours and one serving as the control. A clinical assessment is conducted at 24 hours and repeated 7 days later.1 In photodermatoses, a visible reaction can be appreciated on the treatment arm while the control arm remains clear. When both sides reveal a visible reaction, this is more indicative of a light-independent allergic contact dermatitis.1

Photodermatoses occur only if there has been a specific sensitization, and therefore it is important to work with the patient to discover any new products that have been introduced into their regimen. Though many photosensitizers in personal care products (eg, antiseptics in soap and topical creams) have been discontinued, certain allergenic ingredients may remain.12 It also is important to note that sensitization to a substance that previously was not a known allergen for a particular patient can occur later in life. Avoiding further sun exposure can rapidly improve the dermatitis, and it is possible for spontaneous remission without further intervention; however, as photoallergic reactions can cause severely pruritic skin lesions, the mainstay of symptomatic treatment consists of topical corticosteroids. Oral and topical antihistamines may help alleviate the pruritus but should not be heavily relied on as this can lead to medication resistance and diminishing efficacy.3 Use of short-term oral steroids also may be considered for rapid improvement of symptoms when the patient is in moderate distress and there are no contraindications. By identifying a temporal association between the introduction of new products and the emergence of dermatitis, it may be possible to identify the causative agent. The patient should promptly discontinue the suspected agent and remain under close observation by the clinician for any further eruptions, especially following additional sun exposure.

Prevention Strategies

In the case of PCD, prevention is key. As PCD indicates a photoallergy, it is important to inform patients that the allergy will persist for a lifetime, much like in contact dermatitis; therefore, the causative agent should be avoided indefinitely.3 Patients with PCD should make intentional efforts to read ingredient lists when purchasing new personal care products to ensure they do not contain the specific causative allergen if one has been identified. Further steps should be taken to ensure proper photoprotection, including use of dense clothing and sunscreen with UVA and UVB filters (broad spectrum).3 It has also been suggested that utilizing sunscreen with ectoin, an amino acid–derived molecule, may result in increased protection against UVA-induced photodermatoses.13

Final Thoughts

Photodermatoses are a group of skin diseases caused by exposure to UV radiation. Photocontact dermatitis/photoallergy is a form of allergic contact dermatitis that results from exposure to an allergen, whether topical, oral, or environmental. The allergen is activated by exposure to UV radiation to sensitize the allergic response, resulting in a rash characterized by confluent erythematous patches or plaques, papular vesicles, and rarely blisters.3 Photocontact dermatitis, although rare, is an important differential diagnosis to consider when the presenting rash is restricted to sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the arms, legs, neck, and face. Diagnosis remains a challenge; however, new testing modalities such as photopatch testing may open the door for further confirmation and aid in proper diagnosis leading to earlier treatment times for patients. It is recommended that the clinician and patient work together to identify the possible causative agent to prevent further eruptions.

- Santoro FA, Lim HW. Update on photodermatoses. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:229-238.

- Gimenez-Arnau A, Maurer M, De La Cuadra J, et al. Immediate contact skin reactions, an update of contact urticaria, contact urticaria syndrome and protein contact dermatitis—“a never ending story.” Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:555-562.

- Lehmann P, Schwarz T. Photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:135-141.

- Victor FC, Cohen DE, Soter NA. A 20-year analysis of previous and emerging allergens that elicit photoallergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:605-610.

- Fenticlor (Code 65671). National Cancer Institute EVS Explore. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://ncithesaurus.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/ConceptReport.jsp?dictionary=NCIThesaurus&ns=ncit&code=C65671

- Elmets CA. Photosensitivity disorders (photodermatoses): clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. UptoDate. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/photosensitivity-disorders-photodermatoses-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-treatment

- Snyder M, Turrentine JE, Cruz PD Jr. Photocontact dermatitis and its clinical mimics: an overview for the allergist. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:32-40.

- Cooper EE, Pisano CE, Shapiro SC. Cutaneous manifestations of “lupus”: systemic lupus erythematosus and beyond. Int J Rheumatol. 2021;2021:6610509.

- Christopher-Stine L, Amato AA, Vleugels RA. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in adults. UptoDate. Updated March 3, 2025. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-differential-diagnosis-of-dermatomyositis-and-polymyositis-in-adults?search=Diagnosis%20and%20differential%20diagnosis%20of%20dermatomyositis%20and%20polymyositis%20in%20adults&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- Gonçalo M. Photopatch testing. In: Johansen J, Frosch P, Lepoittevin JP, eds. Contact Dermatitis. Springer; 2011:519-531.

- Enta T. Dermacase. Contact photodermatitis. Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:577,586-587.

- Duteil L, Queille-Roussel C, Aladren S, et al. Prevention of polymophic light eruption afforded by a very high broad-spectrum protection sunscreen containing ectoin. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1603-1613.

- Santoro FA, Lim HW. Update on photodermatoses. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:229-238.

- Gimenez-Arnau A, Maurer M, De La Cuadra J, et al. Immediate contact skin reactions, an update of contact urticaria, contact urticaria syndrome and protein contact dermatitis—“a never ending story.” Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:555-562.

- Lehmann P, Schwarz T. Photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:135-141.

- Victor FC, Cohen DE, Soter NA. A 20-year analysis of previous and emerging allergens that elicit photoallergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:605-610.

- Fenticlor (Code 65671). National Cancer Institute EVS Explore. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://ncithesaurus.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/ConceptReport.jsp?dictionary=NCIThesaurus&ns=ncit&code=C65671

- Elmets CA. Photosensitivity disorders (photodermatoses): clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. UptoDate. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/photosensitivity-disorders-photodermatoses-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-treatment

- Snyder M, Turrentine JE, Cruz PD Jr. Photocontact dermatitis and its clinical mimics: an overview for the allergist. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:32-40.

- Cooper EE, Pisano CE, Shapiro SC. Cutaneous manifestations of “lupus”: systemic lupus erythematosus and beyond. Int J Rheumatol. 2021;2021:6610509.

- Christopher-Stine L, Amato AA, Vleugels RA. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in adults. UptoDate. Updated March 3, 2025. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-differential-diagnosis-of-dermatomyositis-and-polymyositis-in-adults?search=Diagnosis%20and%20differential%20diagnosis%20of%20dermatomyositis%20and%20polymyositis%20in%20adults&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- Gonçalo M. Photopatch testing. In: Johansen J, Frosch P, Lepoittevin JP, eds. Contact Dermatitis. Springer; 2011:519-531.

- Enta T. Dermacase. Contact photodermatitis. Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:577,586-587.

- Duteil L, Queille-Roussel C, Aladren S, et al. Prevention of polymophic light eruption afforded by a very high broad-spectrum protection sunscreen containing ectoin. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1603-1613.

Photodermatoses: Exploring Clinical Presentations, Causative Factors, Differential Diagnoses, and Treatment Strategies

Photodermatoses: Exploring Clinical Presentations, Causative Factors, Differential Diagnoses, and Treatment Strategies

Practice Points

- It is important to consider photodermatoses in patients presenting with a rash that is restricted to light-exposed areas of the skin, such as the arms, legs, neck, and face.

- The mainstay of treatment consists of topical corticosteroids. Oral antihistamines should not be heavily relied on, but short-term oral steroids may be considered for rapid improvement if symptoms are severe.

- It is important to note that, much like in contact dermatitis, the underlying photoallergy causing photocontact dermatitis will persist for a lifetime.

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

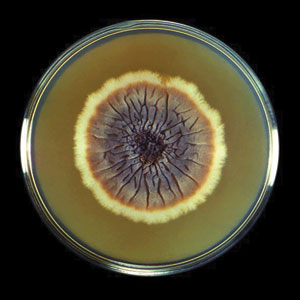

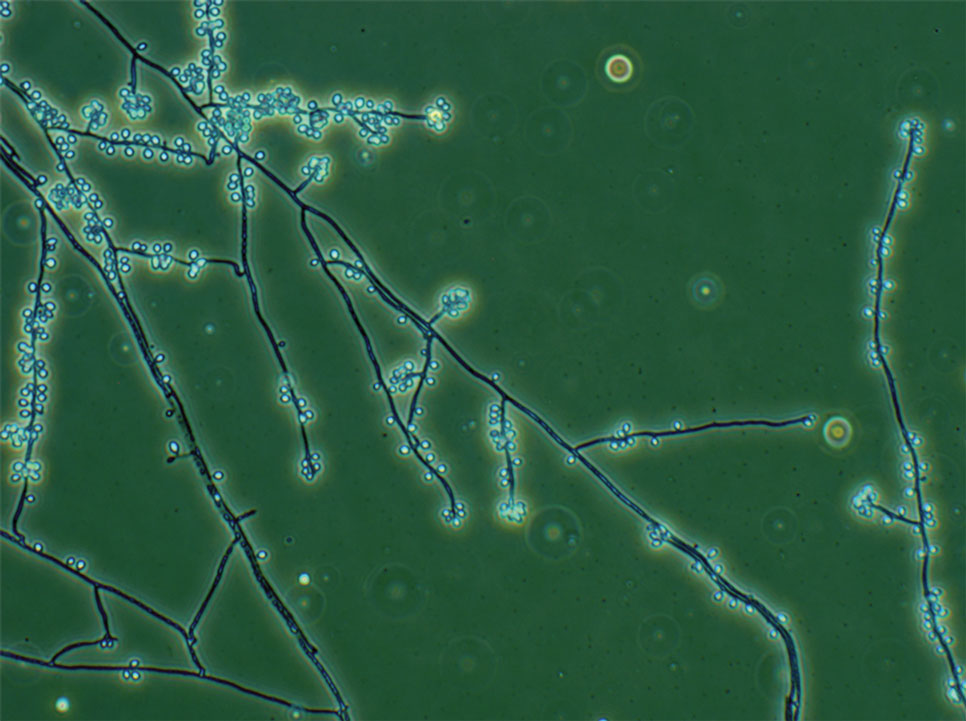

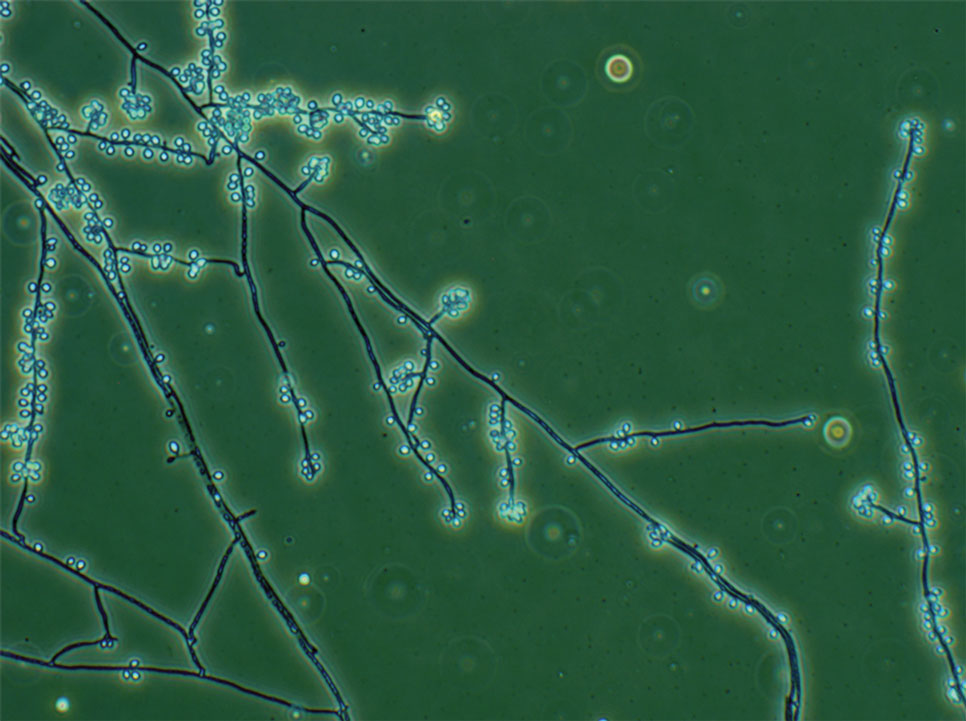

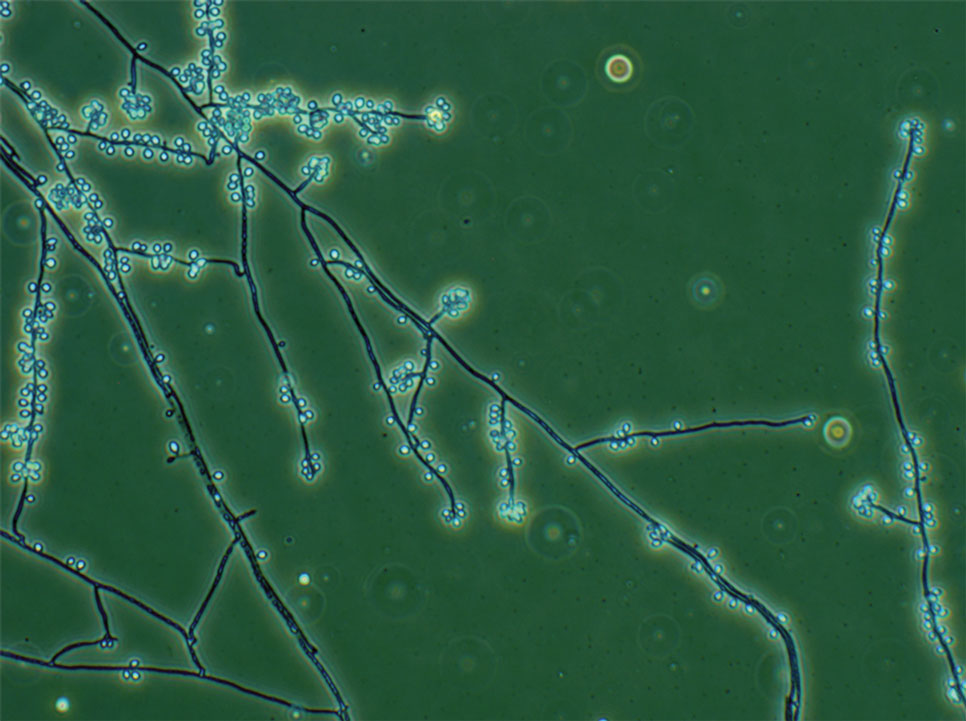

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

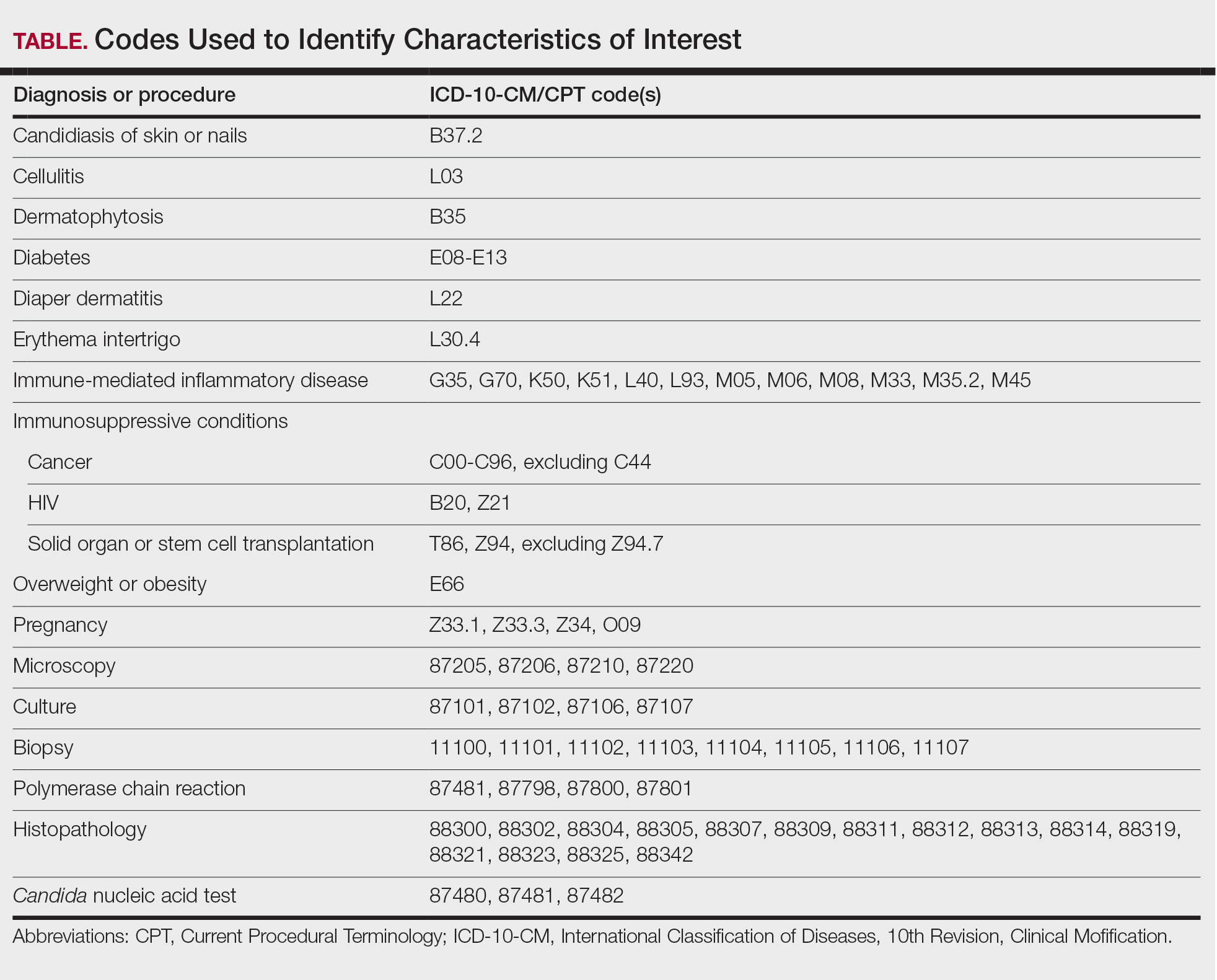

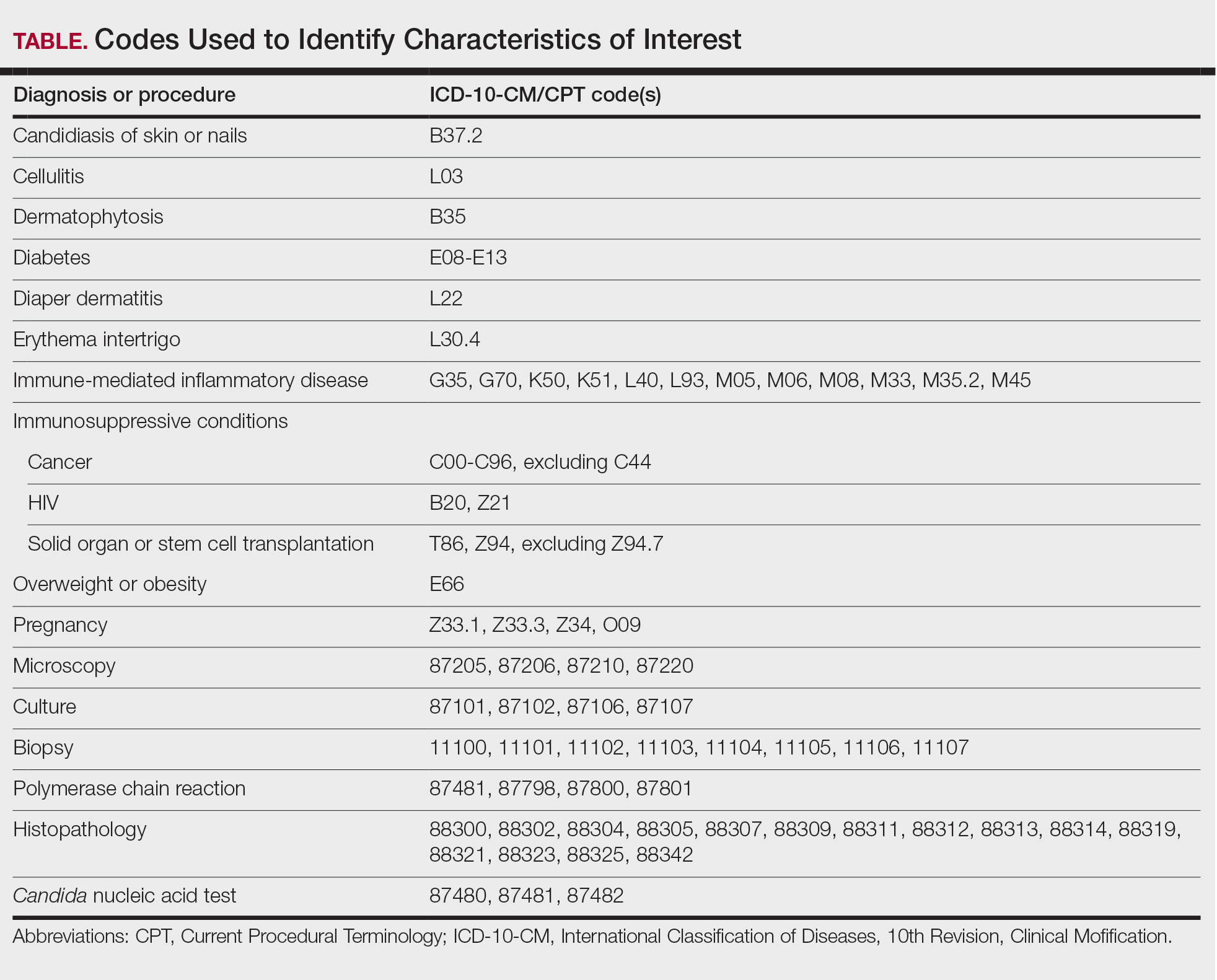

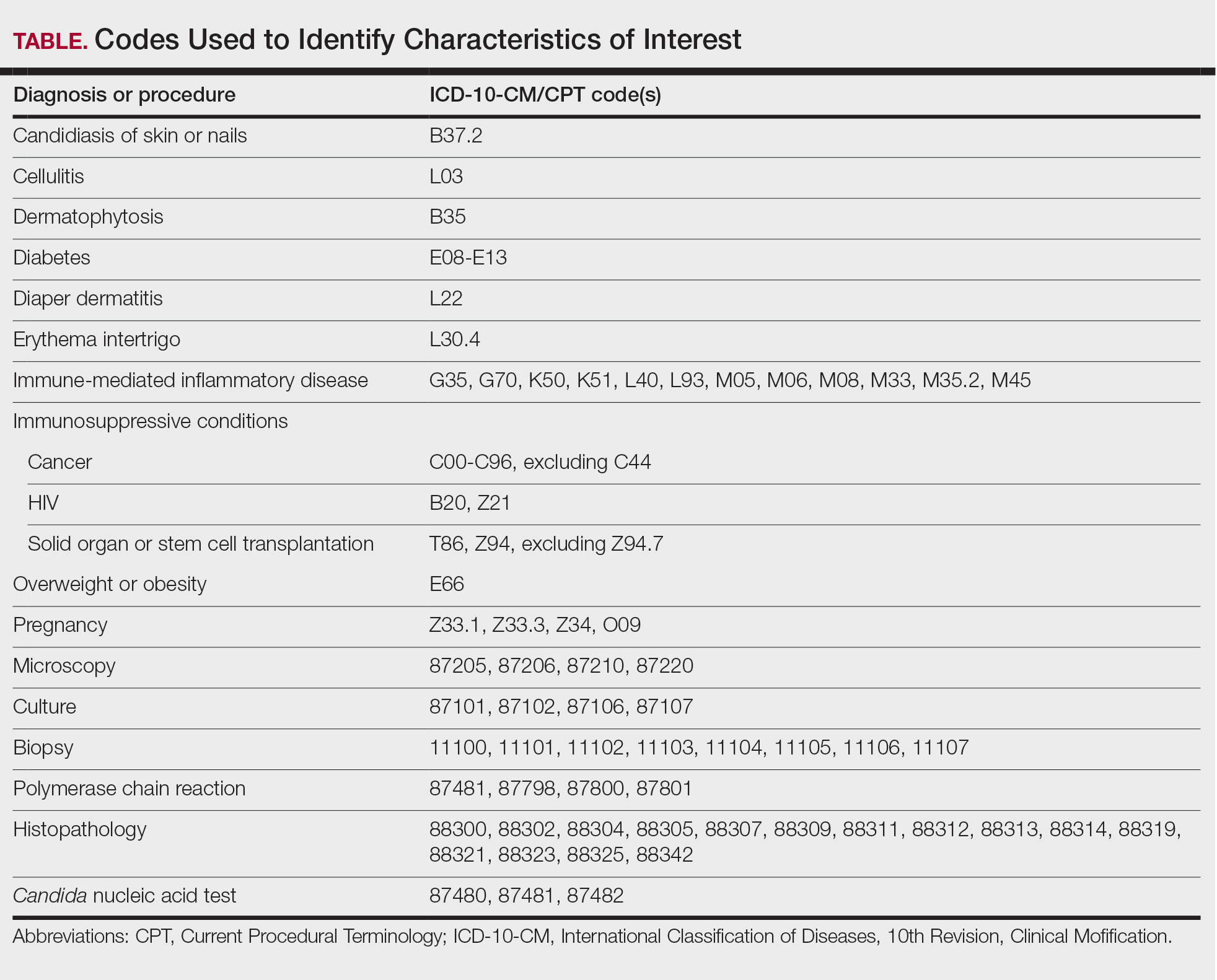

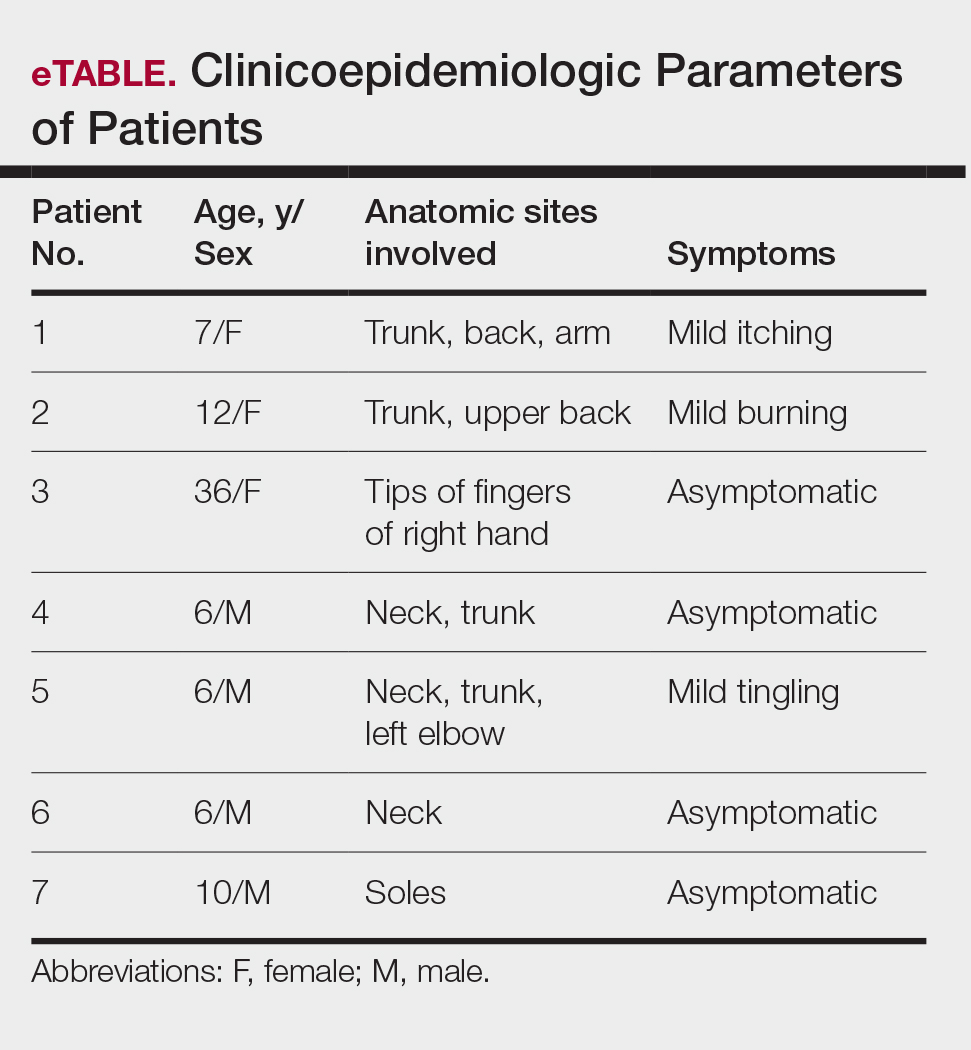

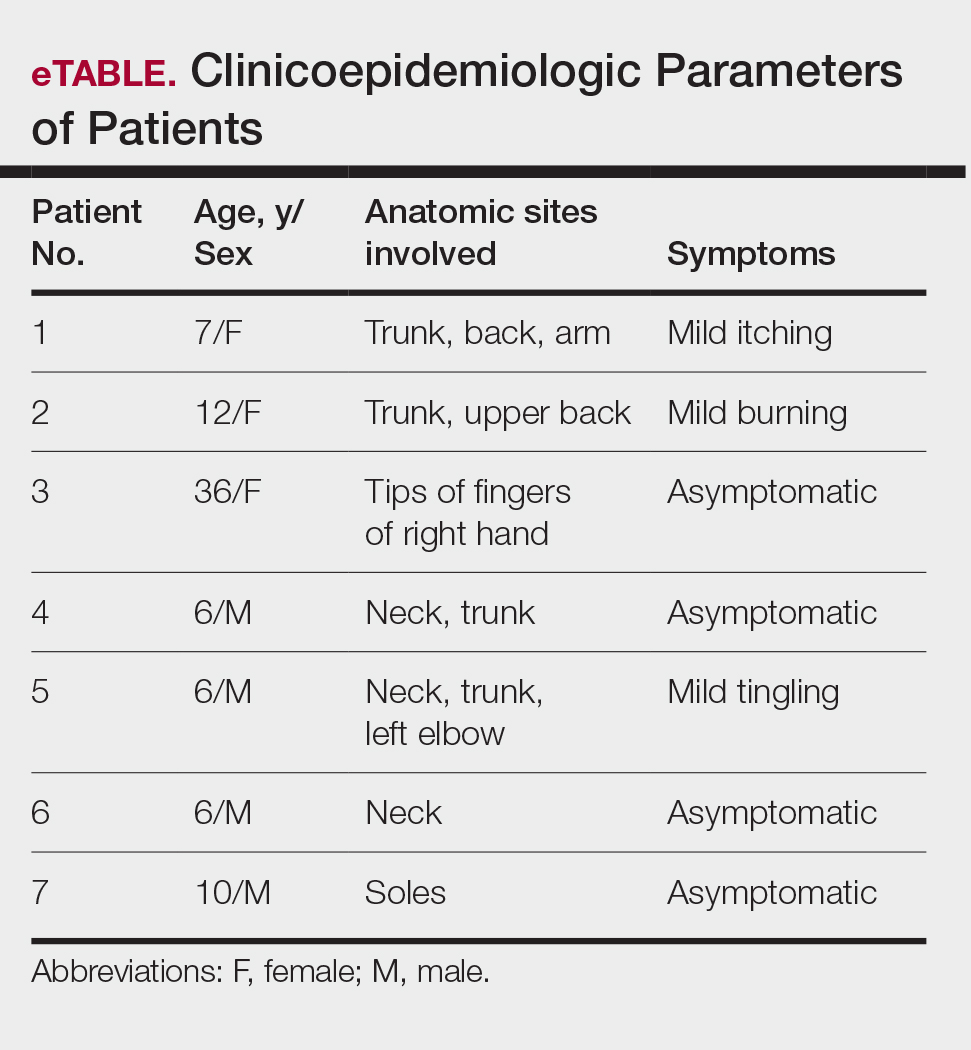

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

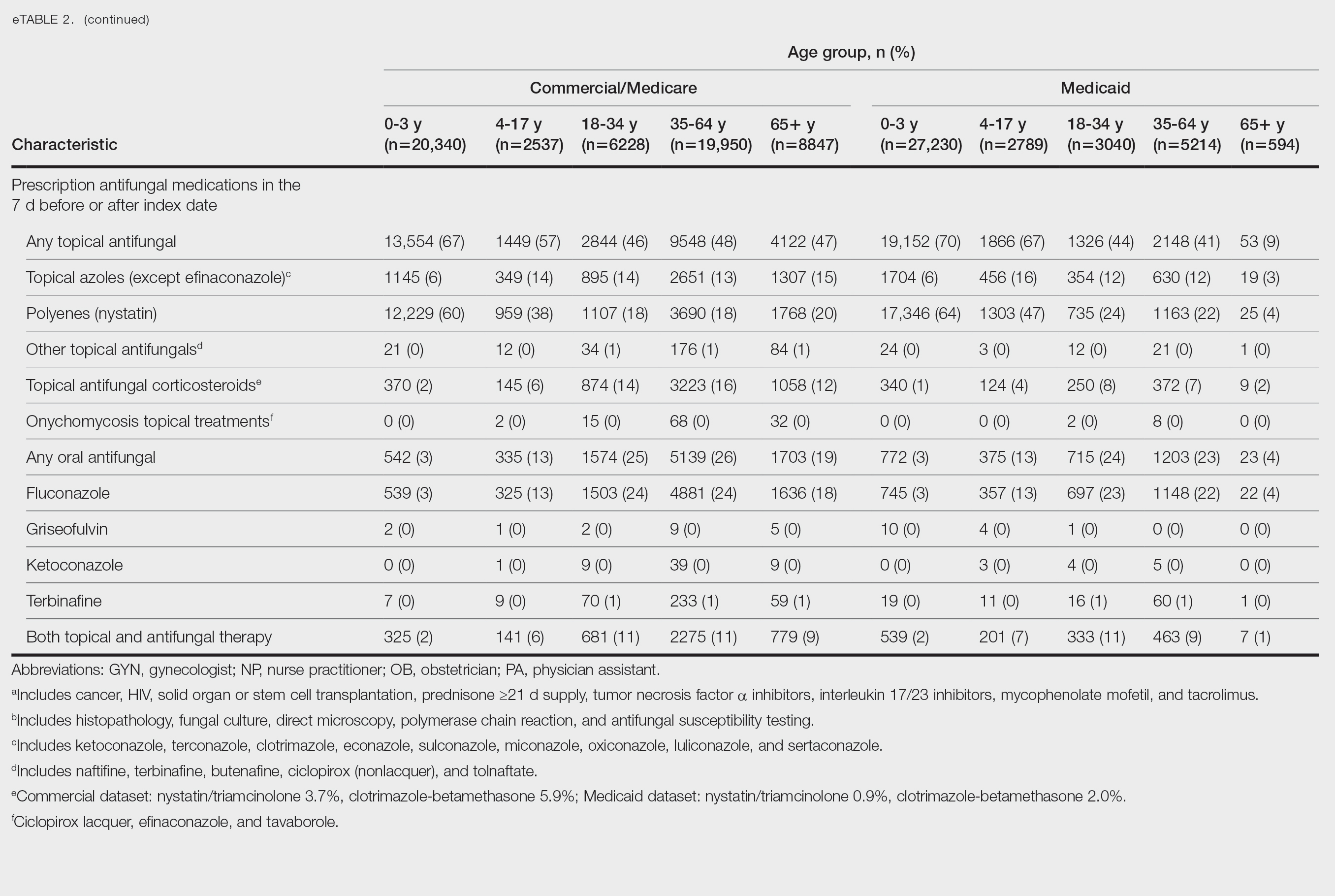

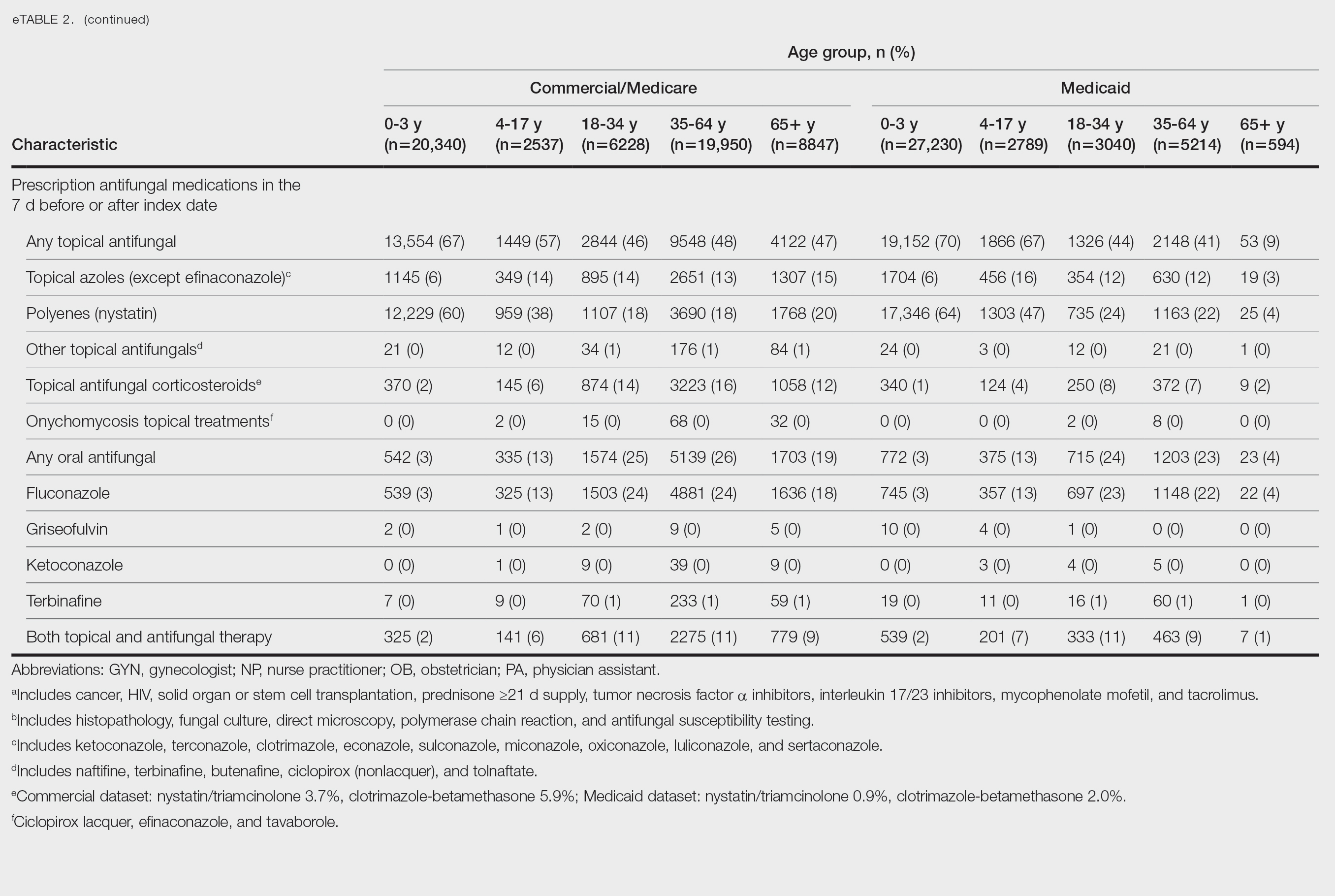

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

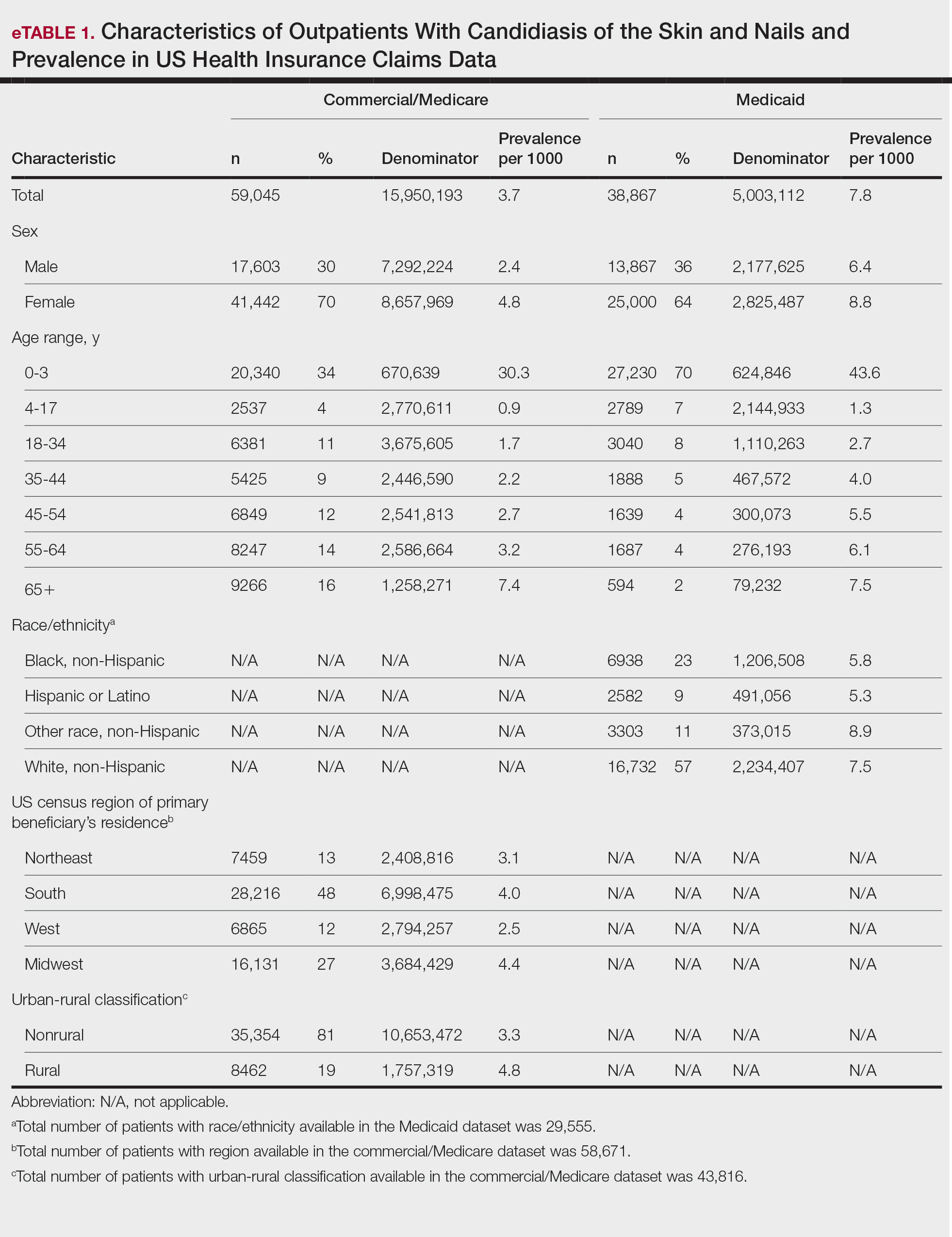

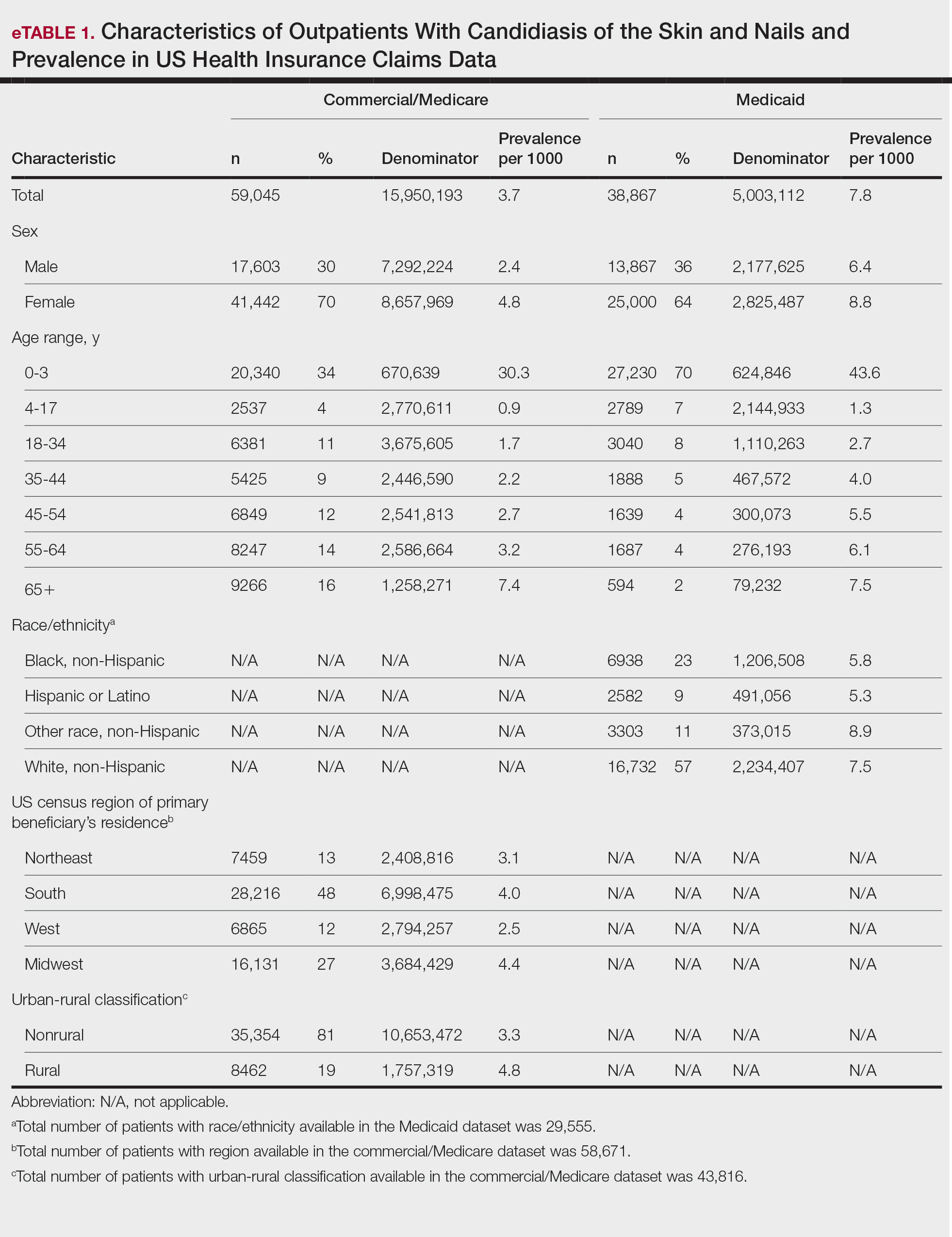

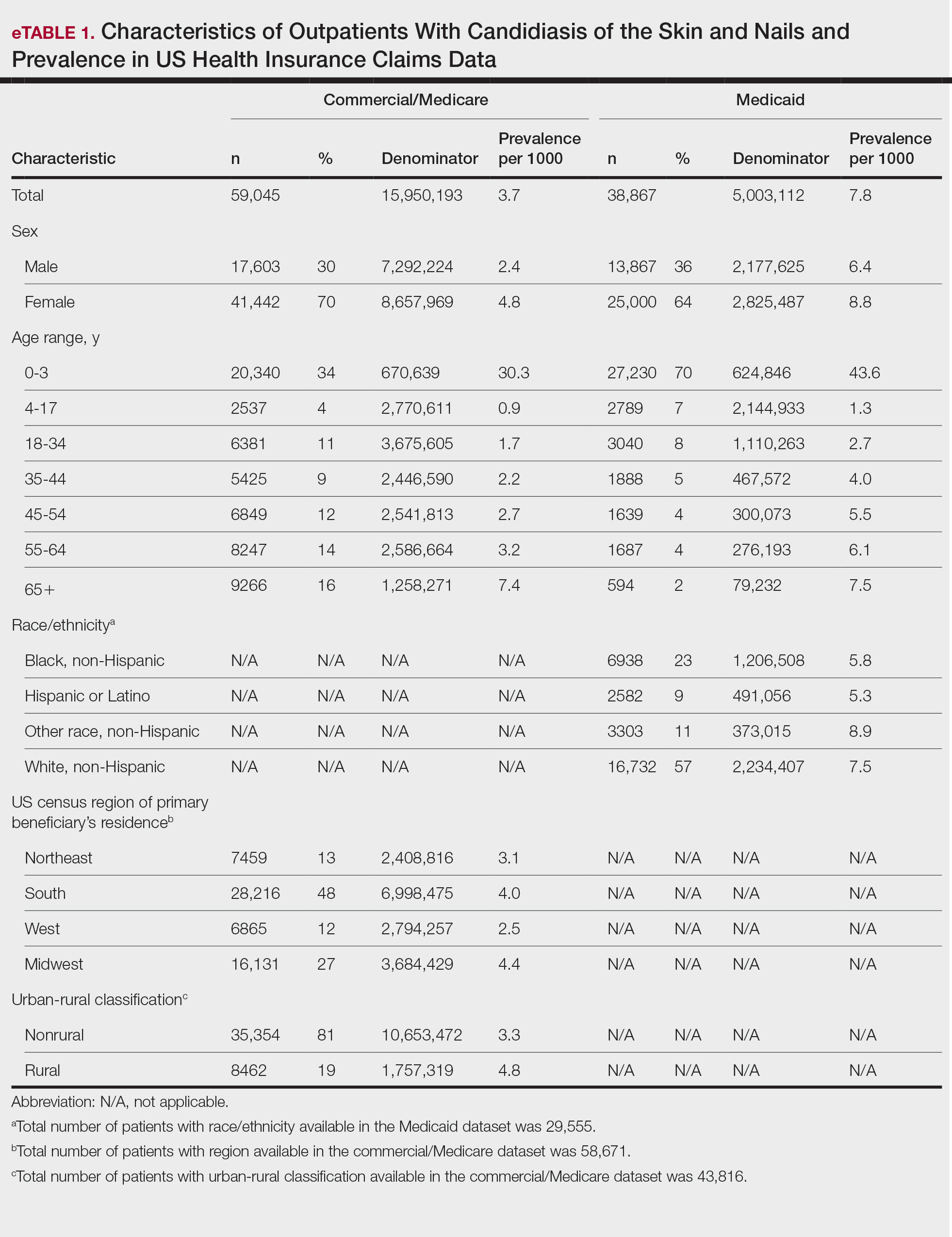

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

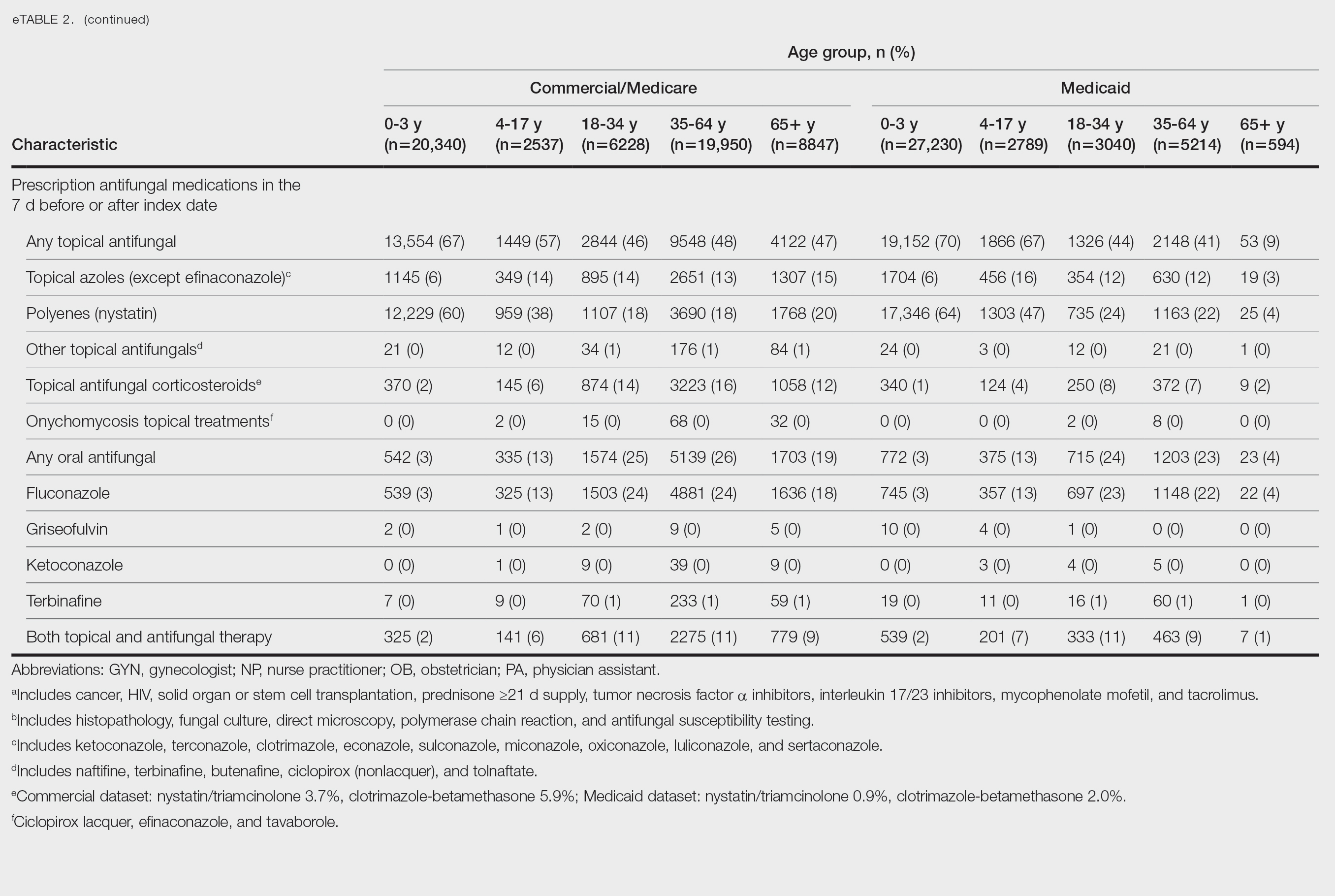

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

- Taudorf EH, Jemec GBE, Hay RJ, et al. Cutaneous candidiasis—an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1863-1873. doi:10.1111/jdv.15782

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102325

- Benitez Ojeda AB, Mendez MD. Diaper dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559067/

- Shahabudin S, Azmi NS, Lani MN, et al. Candida albicans skin infection in diabetic patients: an updated review of pathogenesis and management. Mycoses. 2024;67:E13753. doi:10.1111/myc.13753

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Ranđelovic M, Ignjatovic A, Đorđevic M, et al. Superficial candidiasis: cluster analysis of species distribution and their antifungal susceptibility in vitro. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11:338.

- Hay R. Therapy of skin, hair and nail fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:99. doi:10.3390/jof4030099

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

- Taudorf EH, Jemec GBE, Hay RJ, et al. Cutaneous candidiasis—an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1863-1873. doi:10.1111/jdv.15782

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102325

- Benitez Ojeda AB, Mendez MD. Diaper dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559067/

- Shahabudin S, Azmi NS, Lani MN, et al. Candida albicans skin infection in diabetic patients: an updated review of pathogenesis and management. Mycoses. 2024;67:E13753. doi:10.1111/myc.13753

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Ranđelovic M, Ignjatovic A, Đorđevic M, et al. Superficial candidiasis: cluster analysis of species distribution and their antifungal susceptibility in vitro. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11:338.

- Hay R. Therapy of skin, hair and nail fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:99. doi:10.3390/jof4030099

- Taudorf EH, Jemec GBE, Hay RJ, et al. Cutaneous candidiasis—an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1863-1873. doi:10.1111/jdv.15782

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102325

- Benitez Ojeda AB, Mendez MD. Diaper dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559067/

- Shahabudin S, Azmi NS, Lani MN, et al. Candida albicans skin infection in diabetic patients: an updated review of pathogenesis and management. Mycoses. 2024;67:E13753. doi:10.1111/myc.13753

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Ranđelovic M, Ignjatovic A, Đorđevic M, et al. Superficial candidiasis: cluster analysis of species distribution and their antifungal susceptibility in vitro. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11:338.

- Hay R. Therapy of skin, hair and nail fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:99. doi:10.3390/jof4030099

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Practice Points

- Candidiasis of the skin or nails is a common outpatient condition that is most frequently diagnosed in infants, toddlers, and adults aged 65 years or older.