User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Combined Treatment of Disfiguring Facial Angiofibromas in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex With Surgical Debulking and Topical Sirolimus

Practice Gap

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder resulting in loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. These mutations lead to constitutive activation of the mitogenic mTOR pathway and release of lymphangiogenic growth factors, causing the formation of hamartomatous tumors throughout multiple organ systems.1 Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are a common cutaneous manifestation of TSC, affecting up to 80% of patients worldwide.2 Aesthetic disfigurement, vision obstruction, and breathing impairment often are associated with FAs. They frequently arise in children with TSC and impose a psychosocial burden that can affect the patient’s overall quality of life.

Cutaneous stigmata of TSC pose a significant therapeutic challenge. Topical sirolimus has become a first-line treatment of FAs by inhibiting the mitogenic mTOR pathway1; however, thicker, more extensive lesions are less responsive to topical therapy. The entire dermis is involved in TSC, and topical sirolimus alone often is ineffective for large fibrous FAs.3 Likewise, oral mTOR inhibition has shown only 25% to 50% improvement in FAs and has potential side effects that can limit patients’ tolerance and compliance.4

The Technique

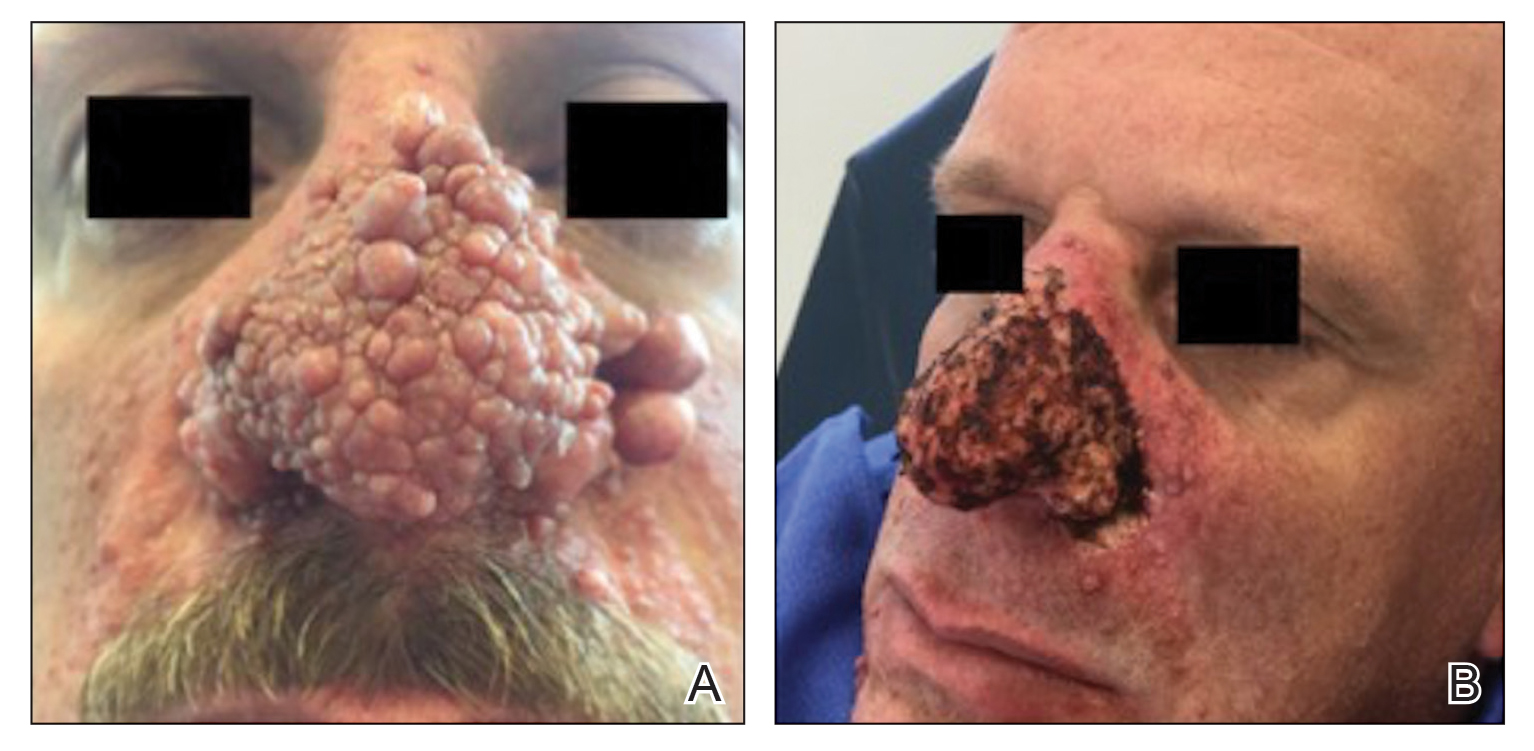

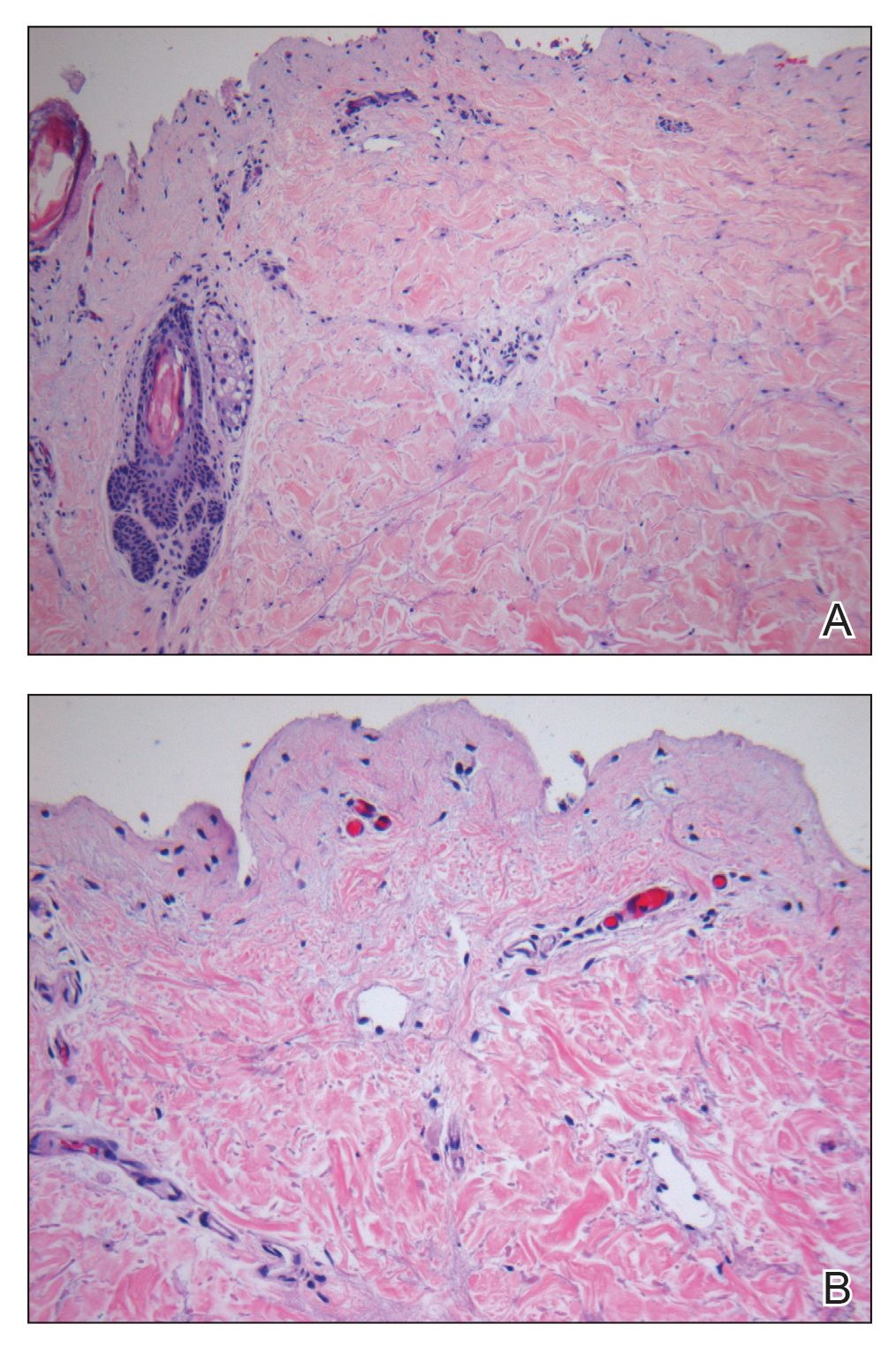

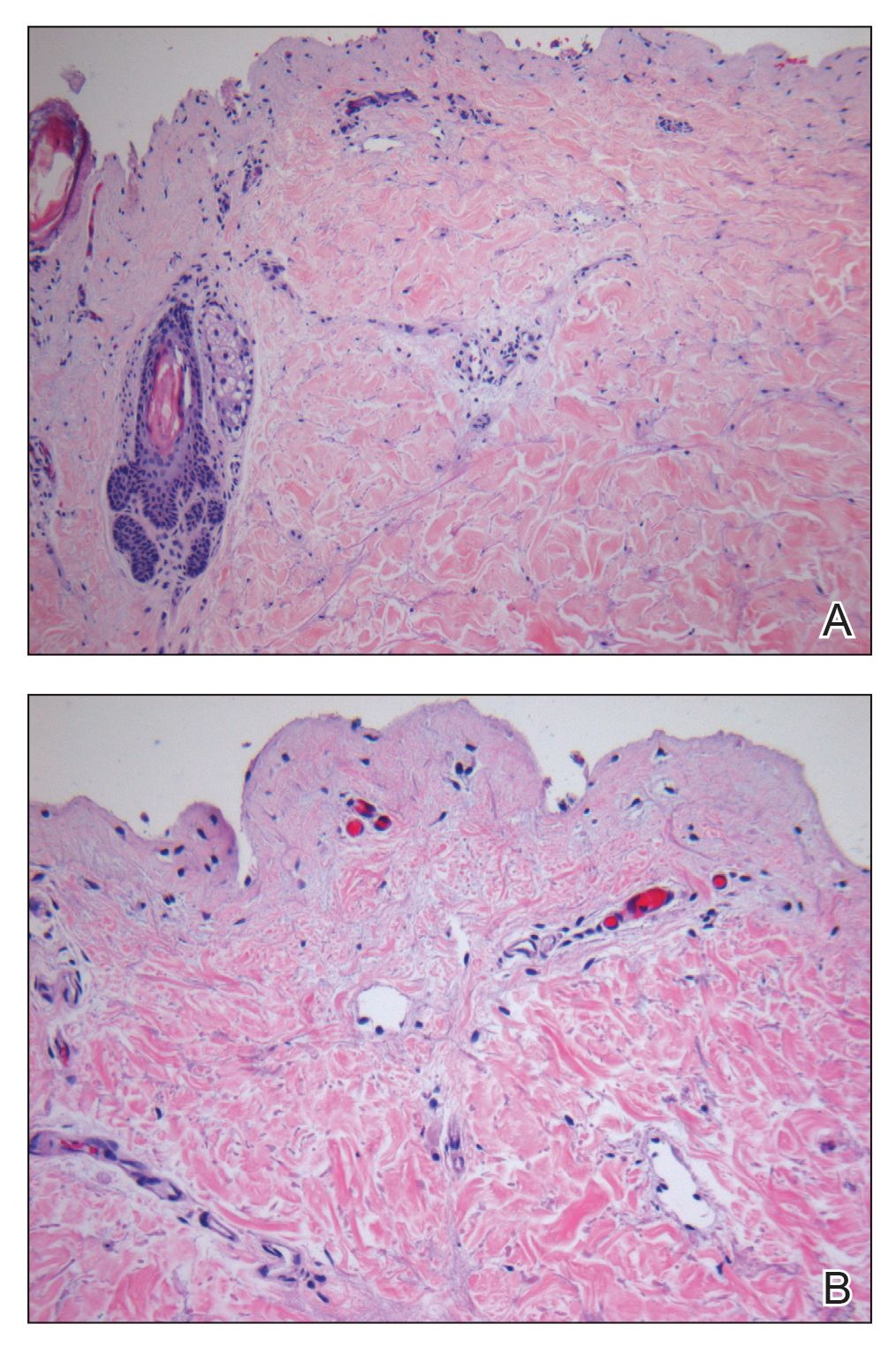

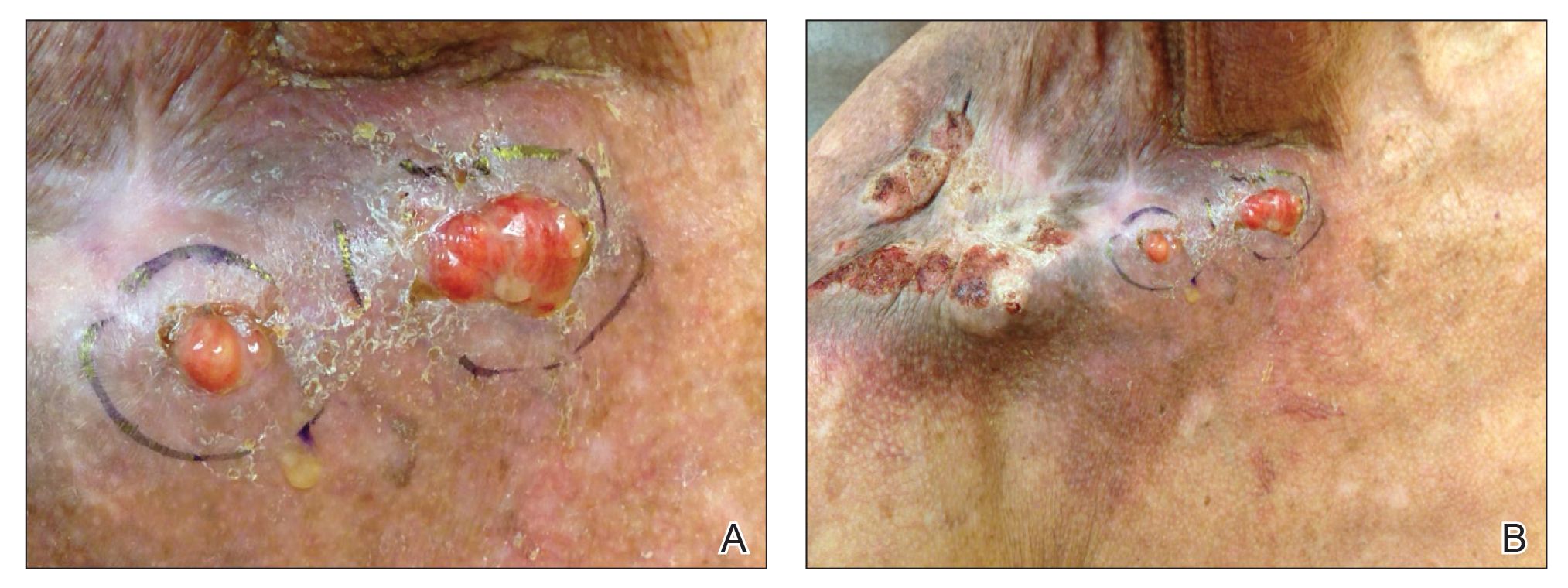

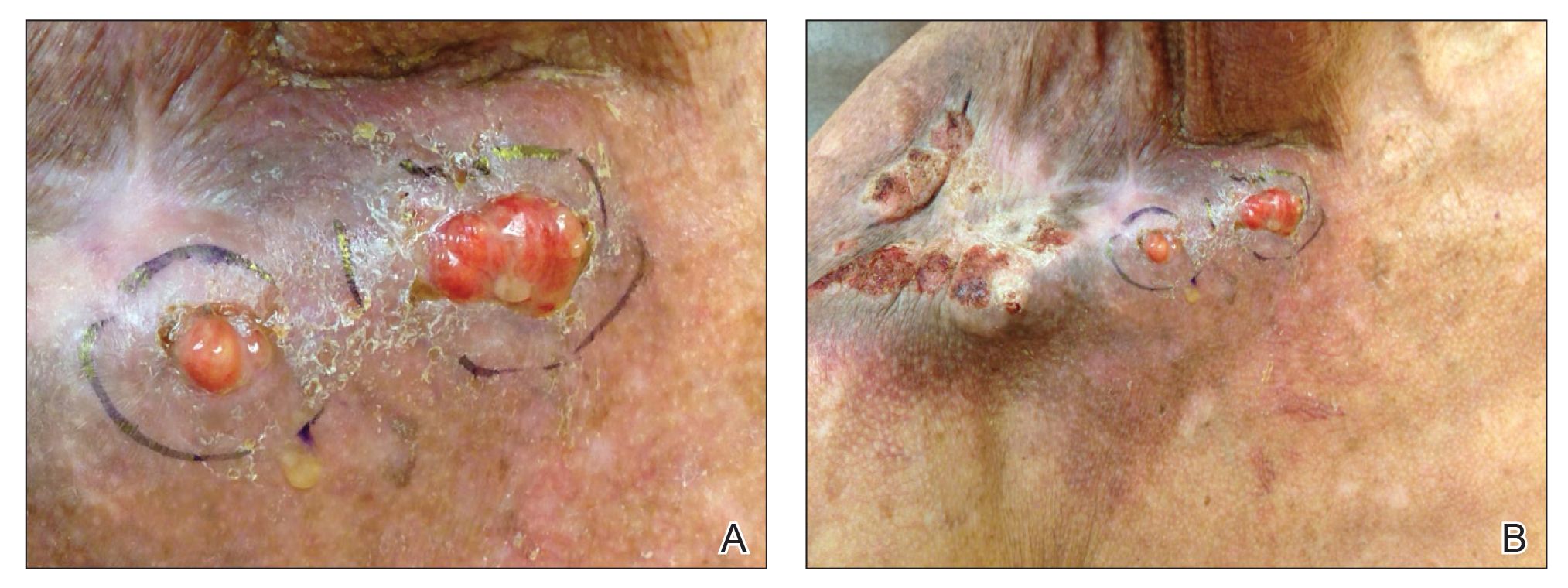

A 46-year-old man with TSC was referred to dermatology for treatment of numerous facial papules and plaques that had been present since childhood and were consistent with FAs (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender, impaired the patient’s breathing, and caused emotional distress. Dermabrasion was attempted 20 years prior with minimal improvement and subsequent progression of the FAs. Other stigmata of TSC were present, including cutaneous hypopigmented macules and shagreen patches as well as seizures and renal angiomyolipomas. Due to multiorgan involvement, the patient was started on once-daily oral everolimus 2.5 mg; however, the FAs were progressive despite the systemic mTOR inhibition. Furthermore, it was presumed that topical sirolimus monotherapy would be ineffective due to thickness and extent of FAs; therefore, we proposed a novel treatment approach combining initial surgical debulking with subsequent longitudinal use of topical sirolimus to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Local anesthesia with lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 was administered. Larger FAs were removed at the base with a sterile surgical blade. Nasal recontouring subsequently was performed using a combination of shave biopsy and curettage. Extensive electrocautery was performed for hemostasis and destruction of residual FAs. Figure 1B shows the immediate postoperative result.

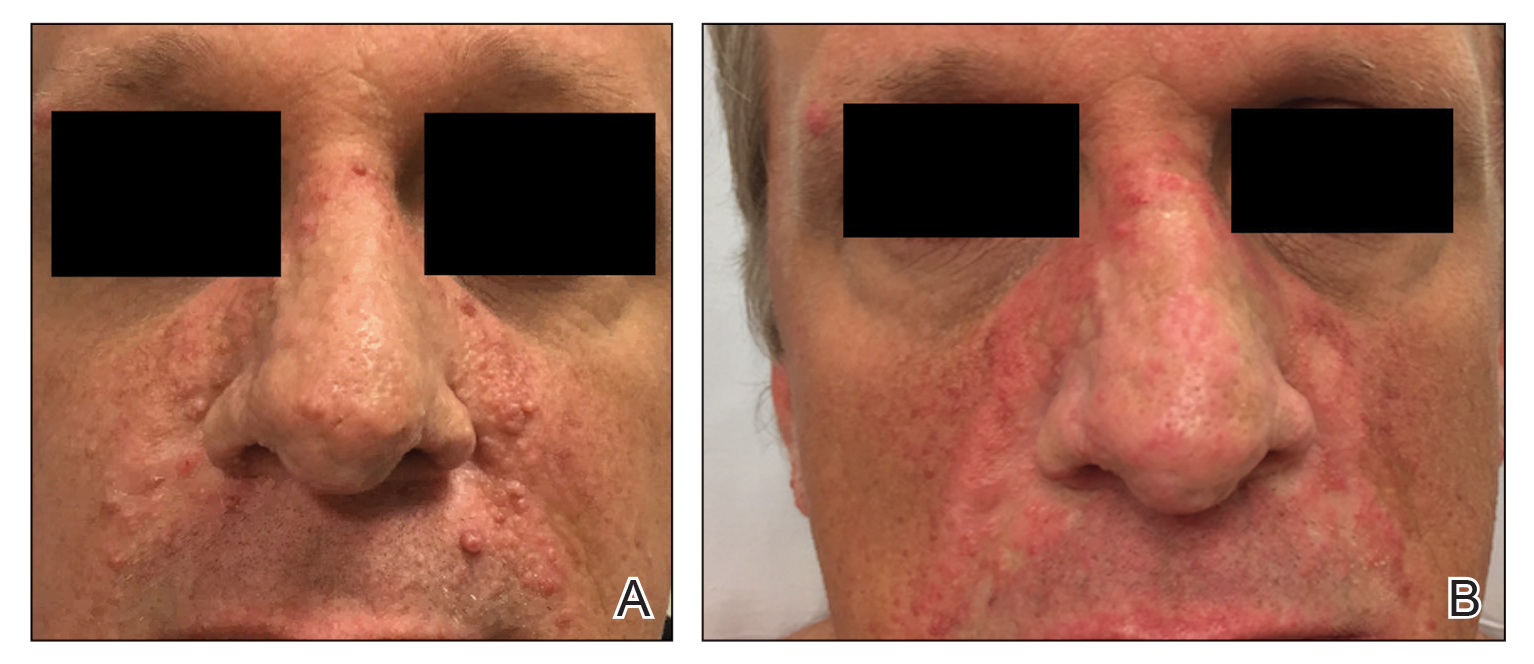

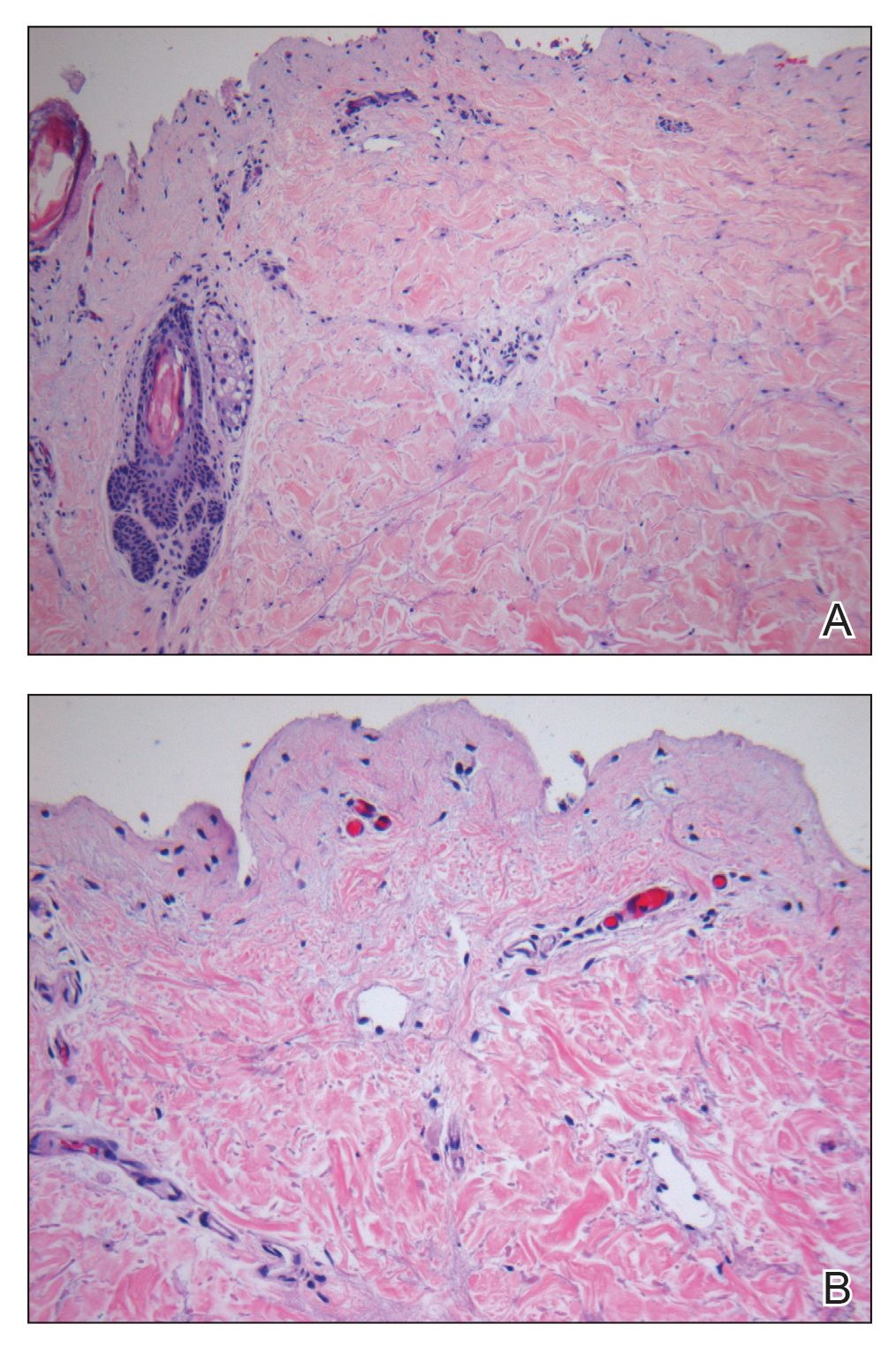

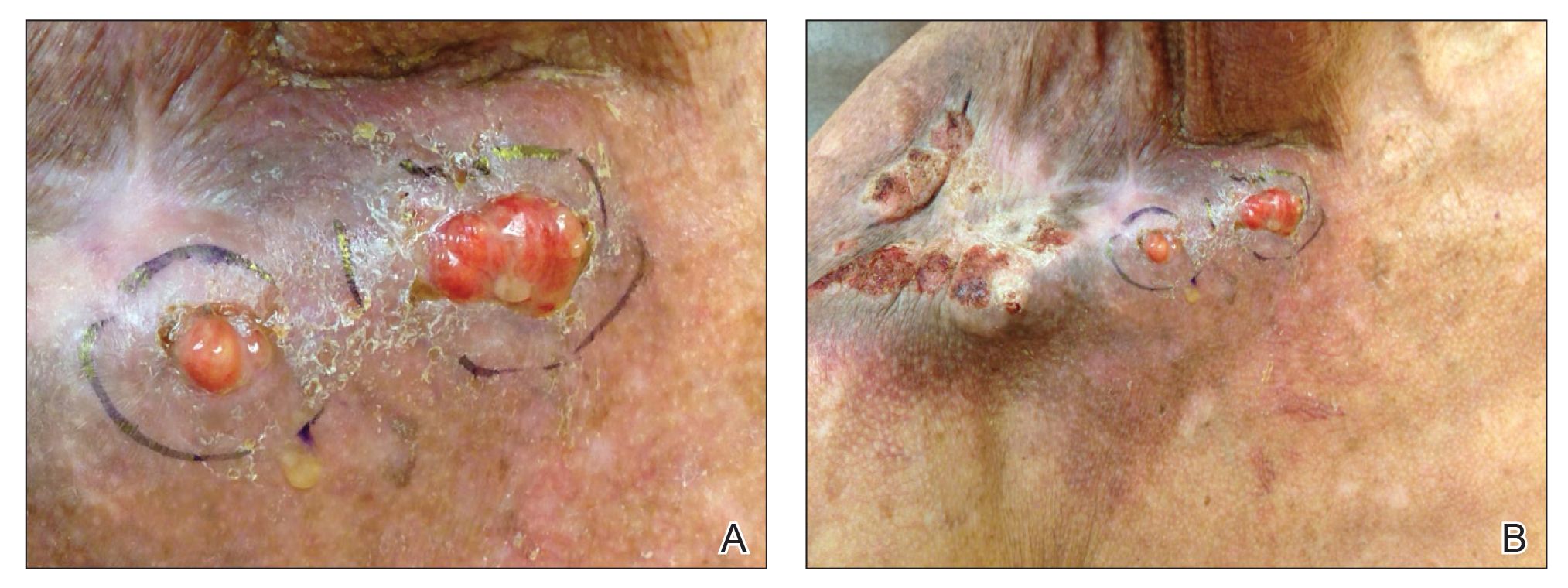

One month postoperatively, the patient stopped the oral everolimus at his oncologist’s recommendation due to abdominal pain and peripheral edema. Once the abraded skin showed evidence of wound healing, the patient was instructed to initiate sirolimus ointment 1% twice daily to reduce the risk of recurrence.1,5,6 At 8-week follow-up, the patient was noted to have cosmetic improvement and resolution of breathing impairment (Figure 2A). He continued to show excellent cosmetic results at 1-year follow-up using topical sirolimus monotherapy (Figure 2B).

Practical Implications

Surgical debulking combined with longitudinal use of sirolimus ointment 1% can achieve an optimal therapeutic response for disfiguring phymatous presentation of FAs in the setting of TSC. We believe it is an effective approach for thick disfiguring FAs that are unlikely to respond to mTOR inhibition alone.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Nakamura A, Tanaka M, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical sirolimus therapy for facial angiofibromas in the tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:39‐48.

- Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, et al. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Drugs R D. 2012;12:121-126.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Ohno Y, Fujita Y, et al. Sirolimus gel treatment vs placebo for facial angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:781-788.

- Nathan N, Wang JA, Li S, et al. Improvement of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) skin tumors during long-term treatment with oral sirolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:802-808.

- Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:126-133.

- Haemel AK, O’Brian AL, Teng JM. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1538-3652.

Practice Gap

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder resulting in loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. These mutations lead to constitutive activation of the mitogenic mTOR pathway and release of lymphangiogenic growth factors, causing the formation of hamartomatous tumors throughout multiple organ systems.1 Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are a common cutaneous manifestation of TSC, affecting up to 80% of patients worldwide.2 Aesthetic disfigurement, vision obstruction, and breathing impairment often are associated with FAs. They frequently arise in children with TSC and impose a psychosocial burden that can affect the patient’s overall quality of life.

Cutaneous stigmata of TSC pose a significant therapeutic challenge. Topical sirolimus has become a first-line treatment of FAs by inhibiting the mitogenic mTOR pathway1; however, thicker, more extensive lesions are less responsive to topical therapy. The entire dermis is involved in TSC, and topical sirolimus alone often is ineffective for large fibrous FAs.3 Likewise, oral mTOR inhibition has shown only 25% to 50% improvement in FAs and has potential side effects that can limit patients’ tolerance and compliance.4

The Technique

A 46-year-old man with TSC was referred to dermatology for treatment of numerous facial papules and plaques that had been present since childhood and were consistent with FAs (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender, impaired the patient’s breathing, and caused emotional distress. Dermabrasion was attempted 20 years prior with minimal improvement and subsequent progression of the FAs. Other stigmata of TSC were present, including cutaneous hypopigmented macules and shagreen patches as well as seizures and renal angiomyolipomas. Due to multiorgan involvement, the patient was started on once-daily oral everolimus 2.5 mg; however, the FAs were progressive despite the systemic mTOR inhibition. Furthermore, it was presumed that topical sirolimus monotherapy would be ineffective due to thickness and extent of FAs; therefore, we proposed a novel treatment approach combining initial surgical debulking with subsequent longitudinal use of topical sirolimus to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Local anesthesia with lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 was administered. Larger FAs were removed at the base with a sterile surgical blade. Nasal recontouring subsequently was performed using a combination of shave biopsy and curettage. Extensive electrocautery was performed for hemostasis and destruction of residual FAs. Figure 1B shows the immediate postoperative result.

One month postoperatively, the patient stopped the oral everolimus at his oncologist’s recommendation due to abdominal pain and peripheral edema. Once the abraded skin showed evidence of wound healing, the patient was instructed to initiate sirolimus ointment 1% twice daily to reduce the risk of recurrence.1,5,6 At 8-week follow-up, the patient was noted to have cosmetic improvement and resolution of breathing impairment (Figure 2A). He continued to show excellent cosmetic results at 1-year follow-up using topical sirolimus monotherapy (Figure 2B).

Practical Implications

Surgical debulking combined with longitudinal use of sirolimus ointment 1% can achieve an optimal therapeutic response for disfiguring phymatous presentation of FAs in the setting of TSC. We believe it is an effective approach for thick disfiguring FAs that are unlikely to respond to mTOR inhibition alone.

Practice Gap

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder resulting in loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes. These mutations lead to constitutive activation of the mitogenic mTOR pathway and release of lymphangiogenic growth factors, causing the formation of hamartomatous tumors throughout multiple organ systems.1 Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are a common cutaneous manifestation of TSC, affecting up to 80% of patients worldwide.2 Aesthetic disfigurement, vision obstruction, and breathing impairment often are associated with FAs. They frequently arise in children with TSC and impose a psychosocial burden that can affect the patient’s overall quality of life.

Cutaneous stigmata of TSC pose a significant therapeutic challenge. Topical sirolimus has become a first-line treatment of FAs by inhibiting the mitogenic mTOR pathway1; however, thicker, more extensive lesions are less responsive to topical therapy. The entire dermis is involved in TSC, and topical sirolimus alone often is ineffective for large fibrous FAs.3 Likewise, oral mTOR inhibition has shown only 25% to 50% improvement in FAs and has potential side effects that can limit patients’ tolerance and compliance.4

The Technique

A 46-year-old man with TSC was referred to dermatology for treatment of numerous facial papules and plaques that had been present since childhood and were consistent with FAs (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender, impaired the patient’s breathing, and caused emotional distress. Dermabrasion was attempted 20 years prior with minimal improvement and subsequent progression of the FAs. Other stigmata of TSC were present, including cutaneous hypopigmented macules and shagreen patches as well as seizures and renal angiomyolipomas. Due to multiorgan involvement, the patient was started on once-daily oral everolimus 2.5 mg; however, the FAs were progressive despite the systemic mTOR inhibition. Furthermore, it was presumed that topical sirolimus monotherapy would be ineffective due to thickness and extent of FAs; therefore, we proposed a novel treatment approach combining initial surgical debulking with subsequent longitudinal use of topical sirolimus to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Local anesthesia with lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 was administered. Larger FAs were removed at the base with a sterile surgical blade. Nasal recontouring subsequently was performed using a combination of shave biopsy and curettage. Extensive electrocautery was performed for hemostasis and destruction of residual FAs. Figure 1B shows the immediate postoperative result.

One month postoperatively, the patient stopped the oral everolimus at his oncologist’s recommendation due to abdominal pain and peripheral edema. Once the abraded skin showed evidence of wound healing, the patient was instructed to initiate sirolimus ointment 1% twice daily to reduce the risk of recurrence.1,5,6 At 8-week follow-up, the patient was noted to have cosmetic improvement and resolution of breathing impairment (Figure 2A). He continued to show excellent cosmetic results at 1-year follow-up using topical sirolimus monotherapy (Figure 2B).

Practical Implications

Surgical debulking combined with longitudinal use of sirolimus ointment 1% can achieve an optimal therapeutic response for disfiguring phymatous presentation of FAs in the setting of TSC. We believe it is an effective approach for thick disfiguring FAs that are unlikely to respond to mTOR inhibition alone.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Nakamura A, Tanaka M, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical sirolimus therapy for facial angiofibromas in the tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:39‐48.

- Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, et al. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Drugs R D. 2012;12:121-126.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Ohno Y, Fujita Y, et al. Sirolimus gel treatment vs placebo for facial angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:781-788.

- Nathan N, Wang JA, Li S, et al. Improvement of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) skin tumors during long-term treatment with oral sirolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:802-808.

- Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:126-133.

- Haemel AK, O’Brian AL, Teng JM. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1538-3652.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Nakamura A, Tanaka M, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical sirolimus therapy for facial angiofibromas in the tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:39‐48.

- Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, et al. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Drugs R D. 2012;12:121-126.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Ohno Y, Fujita Y, et al. Sirolimus gel treatment vs placebo for facial angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:781-788.

- Nathan N, Wang JA, Li S, et al. Improvement of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) skin tumors during long-term treatment with oral sirolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:802-808.

- Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:126-133.

- Haemel AK, O’Brian AL, Teng JM. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1538-3652.

Doctor in a Bottle: Examining the Increase in Essential Oil Use

What Are Essential Oils?

Essential oils are aromatic volatile oils produced by medicinal plants that give them their distinct flavors and aromas. They are extracted using a variety of different techniques, such as microwave-assisted extraction, headspace extraction, and the most commonly employed hydrodistillation.1 Different parts of the plant are used for the specific oils; the shoots and leaves of Origanum vulgare are used for oregano oil, whereas the skins of Citrus limonum are used for lemon oil.2 Historically, essential oils have been used for cooking, food preservation, perfume, and medicine.3,4

Historical Uses for Essential Oils

Essential oils and their intact medicinal plants were among the first medicines widely available to the ancient world. The Ancient Greeks used topical and oral oregano as a cure-all for ailments including wounds, sore muscles, and diarrhea. Because of its use as a cure-all medicine, it remains a popular folk remedy in parts of Europe today.3 Lavender also has a long history of being a cure-all plant and oil. Some of the many claims behind this flower include treatment of burns, insect bites, parasites, muscle spasms, nausea, and anxiety/depression.5 With an extensive list of historical uses, many essential oils are being researched to determine if their acclaimed qualities have quantifiable properties.

Science Behind the Belief

In vitro experiments with oregano (O vulgare) have demonstrated notable antifungal and antimicrobial effects.6 Gas chromatographic analysis of the oil shows much of it is composed of phenolic monoterpenes, such as thymol and carvacrol. They exhibit strong antifungal effects with a slightly stronger effect on the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum over other yeast species such as Candida.7,8 The full effect of the monoterpenes on fungi is not completely understood, but early data show it has a strong affinity for the ergosterol used in the cell-wall synthesis. Other effects demonstrated in in vitro studies include the ability to block drug efflux pumps, biofilm formation, cellular communication among bacteria, and mycotoxin production.9

A double-blind, randomized trial by Akhondzadeh et al10 demonstrated lavender (Lavandula officinalis) to have a mild antidepressant quality but a noticeably more potent effect when combined with imipramine. The effects of the lavender with imipramine were stronger and provided earlier improvement than imipramine alone for treatment of mild to moderate depression. The team concluded that lavender may be an effective adjunct therapy in treating depression.10

In a study by Mori et al,11 full-thickness circular wounds were made in rats and treated with either lavender oil (L officinalis), nothing, or a control oil. With the lavender oil being at only 1% solution, the wounds treated with lavender oil demonstrated earlier closure than the other 2 groups of wounds, where no major difference was noted. On cellular analysis, it was seen that the lavender had increased the rate of granulation as well as expression of types I and III collagen. The most striking result was the large expression of transforming growth factor β seen in the lavender group compared to the others. The final thoughts on this experiment were that lavender may provide new approaches to wound care in the future.11

Potential Problems With Purity

One major concern raised about essential oils is their purity and the fidelity of their chemical composition. The specific aromatic chemicals in each essential oil are maintained for each species, but the proportions of each change even with the time of year.12 Gas chromatograph analysis of the same oil distilled with different techniques showed that the proportions of aromatic chemicals varied with technique. However, the major constituents of the oil remained present in large quantities, just at different percentages.1 Even using the same distillation technique for different time periods can greatly affect the yield and composition of the oil. Although the percentage of each aromatic compound can be affected by distillation times, the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of the oil remain constant regardless of these variables.2 There is clearly a lack in standardization in essential oil production, which may not be an issue for its use in complementary medicine if its properties are maintained regardless.

Safety Concerns and Regulations

With essential oils being a natural cure for everyday ailments, some people are turning first to oils for every cut and bruise. The danger in these natural cures is that essential oils can cause several types of dermatitis and allergic reactions. The development of allergies to essential oils is at an even higher risk, considering people frequently put them on wounds and rashes where the skin barrier is already weakened. Many essential oils fall into the fragrance category in patch tests, negating the widely circulating blogger and online reports that essential oils cannot cause allergies.

Some of the oils, although regarded safe by the US Food and Drug Administration for consumption, can cause dermatitis from simple contact or with sun exposure.13 Members of the citrus family are notorious for the phytophotodermatitis reaction, which can leave hyperpigmented scarring after exposure of the oils to sunlight.14 Most companies that sell essential oils are aware of this reaction and include it in the warning labels.

The legal problem with selling and classifying essential oils is that the US Food and Drug Administration requires products intended for treatment to be labeled as drugs, which hinders their sales on the open market.13 It all boils down to intended use, so some companies sell the oils under a food or fragrance classification with vague instructions on how to use said oil for medicinal purposes, which leads to lack of supervision, anecdotal cures, and false health claims. One company claims in their safety guide for topical applications of their oils that “[i]f a rash occurs, this may be a sign of detoxification.”15 If essential oils had only minimal absorption topically, their safety would be less concerning, but this does not appear to be the case.

Absorption and Systemics

The effects of essential oils on the skin is one aspect of their use to be studied; another is the more systemic effects from absorption through the skin. Most essential oils used in small quantities for fragrance in over-the-counter lotions prove only to be an issue for allergens in sensitive patient groups. However, topical applications of essential oils in their pure concentrated form get absorbed into the skin faster than if used with a carrier oil, emulsion, or solvent.16 For most minor uses of essential oils, the body can detoxify absorbed chemicals the same way it does when a person eats the plants the oils came from (eg, basil essential oils leaching from the leaves into a tomato sauce). A possible danger of the oils’ systemic properties lies in the pregnant patient population who use essential oils thinking that natural is safe.

Many essential oils, such as lavender (L officinalis), exhibit hormonal mimicry with phytoestrogens and can produce emmenagogue (increasing menstrual flow) effects in women. Other oils, such as those of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), can have abortifacient effects. These natural essential oils can lead to unintended health risks for mother and baby.17 With implications this serious, many essential oil companies put pregnancy warnings on most if not all of their products, but pregnant patients may not always note the risk.

Conclusion

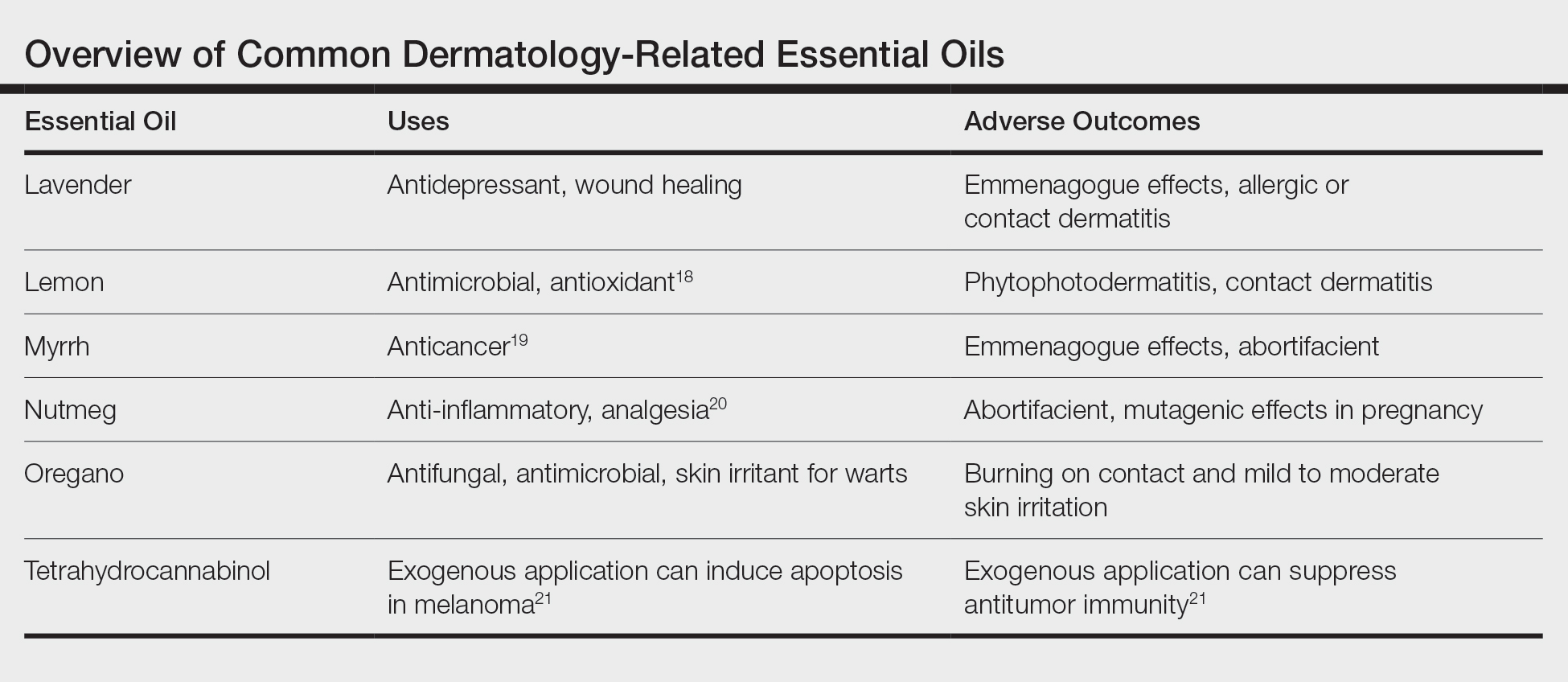

Essential oils are not the newest medical fad. They outdate every drug on the market and were used by some of the first physicians in history. It is important to continue research into the antimicrobial effects of essential oils, as they may hold the secret to treatment options with the continued rise of multidrug-resistant organisms. The danger of these oils lies not in their hidden potential but in the belief that natural things are safe. A few animal studies have been performed, but little is known about the full effects of essential oils in humans. Patients need to be educated that these are not panaceas with freedom from side effects and that treatment options backed by the scientific method should be their first choice under the supervision of trained physicians. The Table outlines the uses and side effects of the essential oils discussed here.

- Fan S, Chang J, Zong Y, et al. GC-MS analysis of the composition of the essential oil from Dendranthema indicum var. aromaticum using three extraction methods and two columns. Molecules. 2018;23:576.

- Zheljazkov VD, Astatkie T, Schlegel V. Distillation time changes oregano essential oil yields and composition but not the antioxidant or antimicrobial activities. HortScience. 2012;47:777-784.

- Singletary K. Oregano: overview of the literature on health benefits. Nutr Today. 2010;45:129-138.

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:90-96.

- Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:681304.

- Cleff MB, Meinerz AR, Xavier M, et al. In vitro activity of Origanum vulgare essential oil against Candida species. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2010;41:116-123.

- Adam K, Sivropoulou A, Kokkini S, et al. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1739-1745.

- Miron D, Battisti F, Silva FK, et al. Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of monoterpenes against dermatophytes and yeasts. Brazil J Pharmacognosy. 2014;24:660-667.

- Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Coppola R, et al. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017;10:86.

- Akhondzadeh S, Kashani L, Fotouhi A, et al. Comparison of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. tincture and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:123-127.

- Mori H-M, Kawanami H, Kawahata H, et al. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF-β in a rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:144.

- Vekiari SA, Protopapadakis EE, Papadopoulou P, et al. Composition and seasonal variation of the essential oil from leaves and peel of a cretan lemon variety. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:147-153.

- Aromatherapy. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm127054.htm. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Hankinson A, Lloyd B, Alweis R. Lime-induced phytophotodermatitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25090.

- Essential Oil Safety Guide. Young Living Essential Oils website. https://www.youngliving.com/en_US/discover/essential-oil-safety. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Cal K. Skin penetration of terpenes from essential oils and topical vehicles. Planta Medica. 2006;72:311-316.

- Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109:227-235.

- Hsouna AB, Halima NB, Smaoui S, et al. Citrus lemon essential oil: chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:146.

- Chen Y, Zhou C, Ge Z, et al. Composition and potential anticancer activities of essential oils obtained from myrrh and frankincense. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1140-1146.

- Zhang WK, Tao S-S, Li T-T, et al. Nutmeg oil alleviates chronic inflammatory pain through inhibition of COX-2 expression and substance P release in vivo. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30849.

- Glodde N, Jakobs M, Bald T, et al. Differential role of cannabinoids in the pathogenesis of skin cancer. Life Sci. 2015;138:35-40.

What Are Essential Oils?

Essential oils are aromatic volatile oils produced by medicinal plants that give them their distinct flavors and aromas. They are extracted using a variety of different techniques, such as microwave-assisted extraction, headspace extraction, and the most commonly employed hydrodistillation.1 Different parts of the plant are used for the specific oils; the shoots and leaves of Origanum vulgare are used for oregano oil, whereas the skins of Citrus limonum are used for lemon oil.2 Historically, essential oils have been used for cooking, food preservation, perfume, and medicine.3,4

Historical Uses for Essential Oils

Essential oils and their intact medicinal plants were among the first medicines widely available to the ancient world. The Ancient Greeks used topical and oral oregano as a cure-all for ailments including wounds, sore muscles, and diarrhea. Because of its use as a cure-all medicine, it remains a popular folk remedy in parts of Europe today.3 Lavender also has a long history of being a cure-all plant and oil. Some of the many claims behind this flower include treatment of burns, insect bites, parasites, muscle spasms, nausea, and anxiety/depression.5 With an extensive list of historical uses, many essential oils are being researched to determine if their acclaimed qualities have quantifiable properties.

Science Behind the Belief

In vitro experiments with oregano (O vulgare) have demonstrated notable antifungal and antimicrobial effects.6 Gas chromatographic analysis of the oil shows much of it is composed of phenolic monoterpenes, such as thymol and carvacrol. They exhibit strong antifungal effects with a slightly stronger effect on the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum over other yeast species such as Candida.7,8 The full effect of the monoterpenes on fungi is not completely understood, but early data show it has a strong affinity for the ergosterol used in the cell-wall synthesis. Other effects demonstrated in in vitro studies include the ability to block drug efflux pumps, biofilm formation, cellular communication among bacteria, and mycotoxin production.9

A double-blind, randomized trial by Akhondzadeh et al10 demonstrated lavender (Lavandula officinalis) to have a mild antidepressant quality but a noticeably more potent effect when combined with imipramine. The effects of the lavender with imipramine were stronger and provided earlier improvement than imipramine alone for treatment of mild to moderate depression. The team concluded that lavender may be an effective adjunct therapy in treating depression.10

In a study by Mori et al,11 full-thickness circular wounds were made in rats and treated with either lavender oil (L officinalis), nothing, or a control oil. With the lavender oil being at only 1% solution, the wounds treated with lavender oil demonstrated earlier closure than the other 2 groups of wounds, where no major difference was noted. On cellular analysis, it was seen that the lavender had increased the rate of granulation as well as expression of types I and III collagen. The most striking result was the large expression of transforming growth factor β seen in the lavender group compared to the others. The final thoughts on this experiment were that lavender may provide new approaches to wound care in the future.11

Potential Problems With Purity

One major concern raised about essential oils is their purity and the fidelity of their chemical composition. The specific aromatic chemicals in each essential oil are maintained for each species, but the proportions of each change even with the time of year.12 Gas chromatograph analysis of the same oil distilled with different techniques showed that the proportions of aromatic chemicals varied with technique. However, the major constituents of the oil remained present in large quantities, just at different percentages.1 Even using the same distillation technique for different time periods can greatly affect the yield and composition of the oil. Although the percentage of each aromatic compound can be affected by distillation times, the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of the oil remain constant regardless of these variables.2 There is clearly a lack in standardization in essential oil production, which may not be an issue for its use in complementary medicine if its properties are maintained regardless.

Safety Concerns and Regulations

With essential oils being a natural cure for everyday ailments, some people are turning first to oils for every cut and bruise. The danger in these natural cures is that essential oils can cause several types of dermatitis and allergic reactions. The development of allergies to essential oils is at an even higher risk, considering people frequently put them on wounds and rashes where the skin barrier is already weakened. Many essential oils fall into the fragrance category in patch tests, negating the widely circulating blogger and online reports that essential oils cannot cause allergies.

Some of the oils, although regarded safe by the US Food and Drug Administration for consumption, can cause dermatitis from simple contact or with sun exposure.13 Members of the citrus family are notorious for the phytophotodermatitis reaction, which can leave hyperpigmented scarring after exposure of the oils to sunlight.14 Most companies that sell essential oils are aware of this reaction and include it in the warning labels.

The legal problem with selling and classifying essential oils is that the US Food and Drug Administration requires products intended for treatment to be labeled as drugs, which hinders their sales on the open market.13 It all boils down to intended use, so some companies sell the oils under a food or fragrance classification with vague instructions on how to use said oil for medicinal purposes, which leads to lack of supervision, anecdotal cures, and false health claims. One company claims in their safety guide for topical applications of their oils that “[i]f a rash occurs, this may be a sign of detoxification.”15 If essential oils had only minimal absorption topically, their safety would be less concerning, but this does not appear to be the case.

Absorption and Systemics

The effects of essential oils on the skin is one aspect of their use to be studied; another is the more systemic effects from absorption through the skin. Most essential oils used in small quantities for fragrance in over-the-counter lotions prove only to be an issue for allergens in sensitive patient groups. However, topical applications of essential oils in their pure concentrated form get absorbed into the skin faster than if used with a carrier oil, emulsion, or solvent.16 For most minor uses of essential oils, the body can detoxify absorbed chemicals the same way it does when a person eats the plants the oils came from (eg, basil essential oils leaching from the leaves into a tomato sauce). A possible danger of the oils’ systemic properties lies in the pregnant patient population who use essential oils thinking that natural is safe.

Many essential oils, such as lavender (L officinalis), exhibit hormonal mimicry with phytoestrogens and can produce emmenagogue (increasing menstrual flow) effects in women. Other oils, such as those of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), can have abortifacient effects. These natural essential oils can lead to unintended health risks for mother and baby.17 With implications this serious, many essential oil companies put pregnancy warnings on most if not all of their products, but pregnant patients may not always note the risk.

Conclusion

Essential oils are not the newest medical fad. They outdate every drug on the market and were used by some of the first physicians in history. It is important to continue research into the antimicrobial effects of essential oils, as they may hold the secret to treatment options with the continued rise of multidrug-resistant organisms. The danger of these oils lies not in their hidden potential but in the belief that natural things are safe. A few animal studies have been performed, but little is known about the full effects of essential oils in humans. Patients need to be educated that these are not panaceas with freedom from side effects and that treatment options backed by the scientific method should be their first choice under the supervision of trained physicians. The Table outlines the uses and side effects of the essential oils discussed here.

What Are Essential Oils?

Essential oils are aromatic volatile oils produced by medicinal plants that give them their distinct flavors and aromas. They are extracted using a variety of different techniques, such as microwave-assisted extraction, headspace extraction, and the most commonly employed hydrodistillation.1 Different parts of the plant are used for the specific oils; the shoots and leaves of Origanum vulgare are used for oregano oil, whereas the skins of Citrus limonum are used for lemon oil.2 Historically, essential oils have been used for cooking, food preservation, perfume, and medicine.3,4

Historical Uses for Essential Oils

Essential oils and their intact medicinal plants were among the first medicines widely available to the ancient world. The Ancient Greeks used topical and oral oregano as a cure-all for ailments including wounds, sore muscles, and diarrhea. Because of its use as a cure-all medicine, it remains a popular folk remedy in parts of Europe today.3 Lavender also has a long history of being a cure-all plant and oil. Some of the many claims behind this flower include treatment of burns, insect bites, parasites, muscle spasms, nausea, and anxiety/depression.5 With an extensive list of historical uses, many essential oils are being researched to determine if their acclaimed qualities have quantifiable properties.

Science Behind the Belief

In vitro experiments with oregano (O vulgare) have demonstrated notable antifungal and antimicrobial effects.6 Gas chromatographic analysis of the oil shows much of it is composed of phenolic monoterpenes, such as thymol and carvacrol. They exhibit strong antifungal effects with a slightly stronger effect on the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum over other yeast species such as Candida.7,8 The full effect of the monoterpenes on fungi is not completely understood, but early data show it has a strong affinity for the ergosterol used in the cell-wall synthesis. Other effects demonstrated in in vitro studies include the ability to block drug efflux pumps, biofilm formation, cellular communication among bacteria, and mycotoxin production.9

A double-blind, randomized trial by Akhondzadeh et al10 demonstrated lavender (Lavandula officinalis) to have a mild antidepressant quality but a noticeably more potent effect when combined with imipramine. The effects of the lavender with imipramine were stronger and provided earlier improvement than imipramine alone for treatment of mild to moderate depression. The team concluded that lavender may be an effective adjunct therapy in treating depression.10

In a study by Mori et al,11 full-thickness circular wounds were made in rats and treated with either lavender oil (L officinalis), nothing, or a control oil. With the lavender oil being at only 1% solution, the wounds treated with lavender oil demonstrated earlier closure than the other 2 groups of wounds, where no major difference was noted. On cellular analysis, it was seen that the lavender had increased the rate of granulation as well as expression of types I and III collagen. The most striking result was the large expression of transforming growth factor β seen in the lavender group compared to the others. The final thoughts on this experiment were that lavender may provide new approaches to wound care in the future.11

Potential Problems With Purity

One major concern raised about essential oils is their purity and the fidelity of their chemical composition. The specific aromatic chemicals in each essential oil are maintained for each species, but the proportions of each change even with the time of year.12 Gas chromatograph analysis of the same oil distilled with different techniques showed that the proportions of aromatic chemicals varied with technique. However, the major constituents of the oil remained present in large quantities, just at different percentages.1 Even using the same distillation technique for different time periods can greatly affect the yield and composition of the oil. Although the percentage of each aromatic compound can be affected by distillation times, the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of the oil remain constant regardless of these variables.2 There is clearly a lack in standardization in essential oil production, which may not be an issue for its use in complementary medicine if its properties are maintained regardless.

Safety Concerns and Regulations

With essential oils being a natural cure for everyday ailments, some people are turning first to oils for every cut and bruise. The danger in these natural cures is that essential oils can cause several types of dermatitis and allergic reactions. The development of allergies to essential oils is at an even higher risk, considering people frequently put them on wounds and rashes where the skin barrier is already weakened. Many essential oils fall into the fragrance category in patch tests, negating the widely circulating blogger and online reports that essential oils cannot cause allergies.

Some of the oils, although regarded safe by the US Food and Drug Administration for consumption, can cause dermatitis from simple contact or with sun exposure.13 Members of the citrus family are notorious for the phytophotodermatitis reaction, which can leave hyperpigmented scarring after exposure of the oils to sunlight.14 Most companies that sell essential oils are aware of this reaction and include it in the warning labels.

The legal problem with selling and classifying essential oils is that the US Food and Drug Administration requires products intended for treatment to be labeled as drugs, which hinders their sales on the open market.13 It all boils down to intended use, so some companies sell the oils under a food or fragrance classification with vague instructions on how to use said oil for medicinal purposes, which leads to lack of supervision, anecdotal cures, and false health claims. One company claims in their safety guide for topical applications of their oils that “[i]f a rash occurs, this may be a sign of detoxification.”15 If essential oils had only minimal absorption topically, their safety would be less concerning, but this does not appear to be the case.

Absorption and Systemics

The effects of essential oils on the skin is one aspect of their use to be studied; another is the more systemic effects from absorption through the skin. Most essential oils used in small quantities for fragrance in over-the-counter lotions prove only to be an issue for allergens in sensitive patient groups. However, topical applications of essential oils in their pure concentrated form get absorbed into the skin faster than if used with a carrier oil, emulsion, or solvent.16 For most minor uses of essential oils, the body can detoxify absorbed chemicals the same way it does when a person eats the plants the oils came from (eg, basil essential oils leaching from the leaves into a tomato sauce). A possible danger of the oils’ systemic properties lies in the pregnant patient population who use essential oils thinking that natural is safe.

Many essential oils, such as lavender (L officinalis), exhibit hormonal mimicry with phytoestrogens and can produce emmenagogue (increasing menstrual flow) effects in women. Other oils, such as those of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), can have abortifacient effects. These natural essential oils can lead to unintended health risks for mother and baby.17 With implications this serious, many essential oil companies put pregnancy warnings on most if not all of their products, but pregnant patients may not always note the risk.

Conclusion

Essential oils are not the newest medical fad. They outdate every drug on the market and were used by some of the first physicians in history. It is important to continue research into the antimicrobial effects of essential oils, as they may hold the secret to treatment options with the continued rise of multidrug-resistant organisms. The danger of these oils lies not in their hidden potential but in the belief that natural things are safe. A few animal studies have been performed, but little is known about the full effects of essential oils in humans. Patients need to be educated that these are not panaceas with freedom from side effects and that treatment options backed by the scientific method should be their first choice under the supervision of trained physicians. The Table outlines the uses and side effects of the essential oils discussed here.

- Fan S, Chang J, Zong Y, et al. GC-MS analysis of the composition of the essential oil from Dendranthema indicum var. aromaticum using three extraction methods and two columns. Molecules. 2018;23:576.

- Zheljazkov VD, Astatkie T, Schlegel V. Distillation time changes oregano essential oil yields and composition but not the antioxidant or antimicrobial activities. HortScience. 2012;47:777-784.

- Singletary K. Oregano: overview of the literature on health benefits. Nutr Today. 2010;45:129-138.

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:90-96.

- Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:681304.

- Cleff MB, Meinerz AR, Xavier M, et al. In vitro activity of Origanum vulgare essential oil against Candida species. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2010;41:116-123.

- Adam K, Sivropoulou A, Kokkini S, et al. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1739-1745.

- Miron D, Battisti F, Silva FK, et al. Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of monoterpenes against dermatophytes and yeasts. Brazil J Pharmacognosy. 2014;24:660-667.

- Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Coppola R, et al. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017;10:86.

- Akhondzadeh S, Kashani L, Fotouhi A, et al. Comparison of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. tincture and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:123-127.

- Mori H-M, Kawanami H, Kawahata H, et al. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF-β in a rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:144.

- Vekiari SA, Protopapadakis EE, Papadopoulou P, et al. Composition and seasonal variation of the essential oil from leaves and peel of a cretan lemon variety. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:147-153.

- Aromatherapy. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm127054.htm. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Hankinson A, Lloyd B, Alweis R. Lime-induced phytophotodermatitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25090.

- Essential Oil Safety Guide. Young Living Essential Oils website. https://www.youngliving.com/en_US/discover/essential-oil-safety. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Cal K. Skin penetration of terpenes from essential oils and topical vehicles. Planta Medica. 2006;72:311-316.

- Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109:227-235.

- Hsouna AB, Halima NB, Smaoui S, et al. Citrus lemon essential oil: chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:146.

- Chen Y, Zhou C, Ge Z, et al. Composition and potential anticancer activities of essential oils obtained from myrrh and frankincense. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1140-1146.

- Zhang WK, Tao S-S, Li T-T, et al. Nutmeg oil alleviates chronic inflammatory pain through inhibition of COX-2 expression and substance P release in vivo. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30849.

- Glodde N, Jakobs M, Bald T, et al. Differential role of cannabinoids in the pathogenesis of skin cancer. Life Sci. 2015;138:35-40.

- Fan S, Chang J, Zong Y, et al. GC-MS analysis of the composition of the essential oil from Dendranthema indicum var. aromaticum using three extraction methods and two columns. Molecules. 2018;23:576.

- Zheljazkov VD, Astatkie T, Schlegel V. Distillation time changes oregano essential oil yields and composition but not the antioxidant or antimicrobial activities. HortScience. 2012;47:777-784.

- Singletary K. Oregano: overview of the literature on health benefits. Nutr Today. 2010;45:129-138.

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:90-96.

- Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:681304.

- Cleff MB, Meinerz AR, Xavier M, et al. In vitro activity of Origanum vulgare essential oil against Candida species. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2010;41:116-123.

- Adam K, Sivropoulou A, Kokkini S, et al. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1739-1745.

- Miron D, Battisti F, Silva FK, et al. Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of monoterpenes against dermatophytes and yeasts. Brazil J Pharmacognosy. 2014;24:660-667.

- Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Coppola R, et al. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017;10:86.

- Akhondzadeh S, Kashani L, Fotouhi A, et al. Comparison of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. tincture and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:123-127.

- Mori H-M, Kawanami H, Kawahata H, et al. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF-β in a rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:144.

- Vekiari SA, Protopapadakis EE, Papadopoulou P, et al. Composition and seasonal variation of the essential oil from leaves and peel of a cretan lemon variety. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:147-153.

- Aromatherapy. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm127054.htm. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Hankinson A, Lloyd B, Alweis R. Lime-induced phytophotodermatitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25090.

- Essential Oil Safety Guide. Young Living Essential Oils website. https://www.youngliving.com/en_US/discover/essential-oil-safety. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Cal K. Skin penetration of terpenes from essential oils and topical vehicles. Planta Medica. 2006;72:311-316.

- Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109:227-235.

- Hsouna AB, Halima NB, Smaoui S, et al. Citrus lemon essential oil: chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:146.

- Chen Y, Zhou C, Ge Z, et al. Composition and potential anticancer activities of essential oils obtained from myrrh and frankincense. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1140-1146.

- Zhang WK, Tao S-S, Li T-T, et al. Nutmeg oil alleviates chronic inflammatory pain through inhibition of COX-2 expression and substance P release in vivo. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30849.

- Glodde N, Jakobs M, Bald T, et al. Differential role of cannabinoids in the pathogenesis of skin cancer. Life Sci. 2015;138:35-40.

Practice Points

- Essential oils are a rising trend of nonprescribed topical supplements used by patients to self-treat.

- Research into historically medicinal essential oils may unlock treatment opportunities in the near future.

- Keeping an open-minded line of communication is critical for divulgence of potential home remedies that could be causing patients harm.

- Understanding the mindset of the essential oil–using community is key to building trust and treating these patients who are often distrusting of Western medicine.

Mobile Apps for Professional Dermatology Education: An Objective Review

With today’s technology, it is easier than ever to access web-based tools that enrich traditional dermatology education. The literature supports the use of these innovative platforms to enhance learning at the student and trainee levels. A controlled study of pediatric residents showed that online modules effectively supplemented clinical experience with atopic dermatitis.1 In a randomized diagnostic study of medical students, practice with an image-based web application (app) that teaches rapid recognition of melanoma proved more effective than learning a rule-based algorithm.2 Given the visual nature of dermatology, pattern recognition is an essential skill that is fostered through experience and is only made more accessible with technology.

With the added benefit of convenience and accessibility, mobile apps can supplement experiential learning. Mirroring the overall growth of mobile apps, the number of available dermatology apps has increased.3 Dermatology mobile apps serve purposes ranging from quick reference tools to comprehensive modules, journals, and question banks. At an academic hospital in Taiwan, both nondermatology and dermatology trainees’ examination performance improved after 3 weeks of using a smartphone-based wallpaper learning module displaying morphologic characteristics of fungi.4 With the expansion of virtual microscopy, mobile apps also have been created as a learning tool for dermatopathology, giving trainees the flexibility and autonomy to view slides on their own time.5 Nevertheless, the literature on dermatology mobile apps designed for the education of medical students and trainees is limited, demonstrating a need for further investigation.

Prior studies have reviewed dermatology apps for patients and practicing dermatologists.6-8 Herein, we focus on mobile apps targeting students and residents learning dermatology. General dermatology reference apps and educational aid apps have grown by 33% and 32%, respectively, from 2014 to 2017.3 As with any resource meant to educate future and current medical providers, there must be an objective review process in place to ensure accurate, unbiased, evidence-based teaching.

Well-organized, comprehensive information and a user-friendly interface are additional factors of importance when selecting an educational mobile app. When discussing supplemental resources, accessibility and affordability also are priorities given the high cost of a medical education at baseline. Overall, there is a need for a standardized method to evaluate the key factors of an educational mobile app that make it appropriate for this demographic. We conducted a search of mobile apps relating to dermatology education for students and residents.

Methods

We searched for publicly available mobile apps relating to dermatology education in the App Store (Apple Inc) from September to November 2019 using the search terms dermatology education, dermoscopy education, melanoma education, skin cancer education, psoriasis education, rosacea education, acne education, eczema education, dermal fillers education, and Mohs surgery education. We excluded apps that were not in English, were created for a conference, cost more than $5 to download, or did not include a specific dermatology education section. In this way, we hoped to evaluate apps that were relevant, accessible, and affordable.

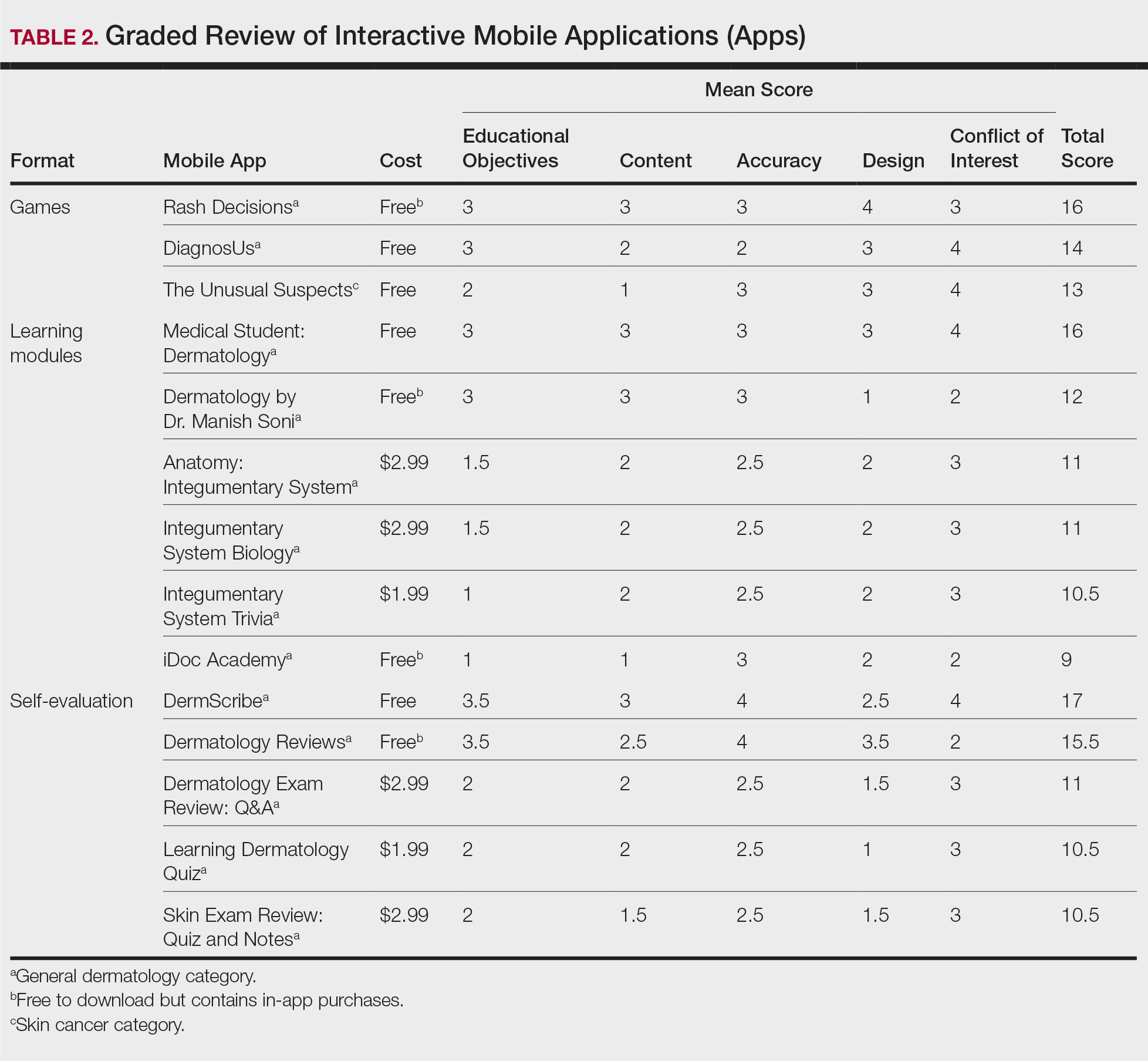

We modeled our study after a review of patient education apps performed by Masud et al6 and utilized their quantified grading rubric (scale of 1 to 4). We found their established criteria—educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest—to be equally applicable for evaluating apps designed for professional education.6 Each app earned a minimum of 1 point and a maximum of 4 points per criterion. One point was given if the app did not fulfill the criterion, 2 points for minimally fulfilling the criterion, 3 points for mostly fulfilling the criterion, and 4 points if the criterion was completely fulfilled. Two medical students (E.H. and N.C.)—one at the preclinical stage and the other at the clinical stage of medical education—reviewed the apps using the given rubric, then discussed and resolved any discrepancies in points assigned. A dermatology resident (M.A.) independently reviewed the apps using the given rubric.

The mean of the student score and the resident score was calculated for each category. The sum of the averages for each category was considered the final score for an app, determining its overall quality. Apps with a total score of 5 to 10 were considered poor and inadequate for education. A total score of 10.5 to 15 indicated that an app was somewhat adequate (ie, useful for education in some aspects but falling short in others). Apps that were considered adequate for education, across all or most criteria, received a total score ranging from 15.5 to 20.

Results

Our search generated 130 apps. After applying exclusion criteria, 42 apps were eligible for review. At the time of publication, 36 of these apps were still available. The possible range of scores based on the rubric was 5 to 20. The actual range of scores was 7 to 20. Of the 36 apps, 2 (5.6%) were poor, 16 (44.4%) were somewhat adequate, and 18 (50%) were adequate. Formats included primary resources, such as clinical decision support tools, journals, references, and a podcast (Table 1). Additionally, interactive learning tools included games, learning modules, and apps for self-evaluation (Table 2). Thirty apps covered general dermatology; others focused on skin cancer (n=5) and cosmetic dermatology (n=1). Regarding cost, 29 apps were free to download, whereas 7 charged a fee (mean price, $2.56).

Comment

In addition to the convenience of having an educational tool in their white-coat pocket, learners of dermatology have been shown to benefit from supplementing their curriculum with mobile apps, which sets the stage for formal integration of mobile apps into dermatology teaching in the future.8 Prior to widespread adoption, mobile apps must be evaluated for content and utility, starting with an objective rubric.

Without official scientific standards in place, it was unsurprising that only half of the dermatology education applications were classified as adequate in this study. Among the types of apps offered—clinical decision support tools, journals, references, podcast, games, learning modules, and self-evaluation—certain categories scored higher than others. App formats with the highest average score (16.5 out of 20) were journals and podcast.

One barrier to utilization of these apps was that a subscription to the journals and podcast was required to obtain access to all available content. Students and trainees can seek out library resources at their academic institutions to take advantage of journal subscriptions available to them at no additional cost. Dermatology residents can take advantage of their complimentary membership in the American Academy of Dermatology for a free subscription to AAD Dialogues in Dermatology (otherwise $179 annually for nonresident members and $320 annually for nonmembers).

On the other hand, learning module was the lowest-rated format (average score, 11.3 out of 20), with only Medical Student: Dermatology qualifying as adequate (total score, 16). This finding is worrisome given that students and residents might look to learning modules for quick targeted lessons on specific topics.

The lowest-scoring app, a clinical decision support tool called Naturelize, received a total score of 7. Although it listed the indications and contraindications for dermal filler types to be used in different locations on the face, there was a clear conflict of interest, oversimplified design, and little evidence-based education, mirroring the current state of cosmetic dermatology training in residency, in which trainees think they are inadequately prepared for aesthetic procedures and comparative effectiveness research is lacking.9-11

At the opposite end of the spectrum, MyDermPath+ was a reference app with a total score of 20. The app cited credible authors with a medical degree (MD) and had an easy-to-use, well-designed interface, including a reference guide, differential builder, and quiz for a range of topics within dermatology. As a free download without in-app purchases or advertisements, there was no evidence of conflict of interest. The position of a dermatopathology app as the top dermatology education mobile app might reflect an increased emphasis on dermatopathology education in residency as well as a transition to digitization of slides.5

The second-highest scoring apps (total score of 19 points) were Dermatology Database and VisualDx. Both were references covering a wide range of dermatology topics. Dermatology Database was a comprehensive search tool for diseases, drugs, procedures, and terms that was simple and entirely free to use but did not cite references. VisualDx, as its name suggests, offered quality clinical images, complete guides with references, and a unique differential builder. An annual subscription is $399.99, but the process to gain free access through a participating academic institution was simple.

Games were a unique mobile app format; however, 2 of 3 games scored in the somewhat adequate range. The game DiagnosUs, which tested users’ ability to differentiate skin cancer and psoriasis from dermatitis on clinical images, would benefit from more comprehensive content as well as professional verification of true diagnoses, which earned the app 2 points in both the content and accuracy categories. The Unusual Suspects tested the ABCDE algorithm in a short learning module, followed by a simple game that involved identification of melanoma in a timed setting. Although the design was novel and interactive, the game was limited to the same 5 melanoma tumors overlaid on pictures of normal skin. The narrow scope earned 1 point for content, the redundancy in the game earned 3 points for design, and the lack of real clinical images earned 2 points for educational objectives. Although game-format mobile apps have the capability to challenge the user’s knowledge with a built-in feedback or reward system, improvements should be made to ensure that apps are equally educational as they are engaging.

AAD Dialogues in Dermatology was the only app in the form of a podcast and provided expert interviews along with disclosures, transcripts, commentary, and references. More than half the content in the app could not be accessed without a subscription, earning 2.5 points in the conflict of interest category. Additionally, several flaws resulted in a design score of 2.5, including inconsistent availability of transcripts, poor quality of sound on some episodes, difficulty distinguishing new episodes from those already played, and a glitch that removed the episode duration. Still, the app was a valuable and comprehensive resource, with clear objectives and cited references. With improvements in content, affordability, and user experience, apps in unique formats such as games and podcasts might appeal to kinesthetic and auditory learners.

An important factor to consider when discussing mobile apps for students and residents is cost. With rising prices of board examinations and preparation materials, supplementary study tools should not come with an exorbitant price tag. Therefore, we limited our evaluation to apps that were free or cost less than $5 to download. Even so, subscriptions and other in-app purchases were an obstacle in one-third of apps, ranging from $4.99 to unlock additional content in Rash Decisions to $69.99 to access most topics in Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas. The highest-rated app in our study, MyDermPath+, historically cost $19.99 to download but became free with a grant from the Sulzberger Foundation.12 An initial investment to develop quality apps for the purpose of dermatology education might pay off in the end.

To evaluate the apps from the perspective of the target demographic of this study, 2 medical students—one in the preclinical stage and the other in the clinical stage of medical education—and a dermatology resident graded the apps. Certain limitations exist in this type of study, including differing learning styles, which might influence the types of apps that evaluators found most impactful to their education. Interestingly, some apps earned a higher resident score than student score. In particular, RightSite (a reference that helps with anatomically correct labeling) and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (a clinical decision support tool to determine whether to perform Mohs surgery) each had a 3-point discrepancy (data not shown). A resident might benefit from these practical apps in day-to-day practice, but a student would be less likely to find them useful as a learning tool.

Still, by defining adequate teaching value using specific categories of educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest, we attempted to minimize the effect of personal preference on the grading process. Although we acknowledge a degree of subjectivity, we found that utilizing a previously published rubric with defined criteria was crucial in remaining unbiased.

Conclusion

Further studies should evaluate additional apps available on Apple’s iPad (tablet), as well as those on other operating systems, including Google’s Android. To ensure the existence of mobile apps as adequate education tools, they should be peer reviewed prior to publication or before widespread use by future and current providers at the minimum. To maximize free access to highly valuable resources available in the palm of their hand, students and trainees should contact the library at their academic institution.

- Craddock MF, Blondin HM, Youssef MJ, et al. Online education improves pediatric residents' understanding of atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:64-69.

- Lacy FA, Coman GC, Holliday AC, et al. Assessment of smartphone application for teaching intuitive visual diagnosis of melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:730-731.

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology--2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13.

- Liu R-F, Wang F-Y, Yen H, et al. A new mobile learning module using smartphone wallpapers in identification of medical fungi for medical students and residents. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:458-462.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Masud A, Shafi S, Rao BK. Mobile medical apps for patient education: a graded review of available dermatology apps. Cutis. 2018;101:141-144.

- Mercer JM. An array of mobile apps for dermatologists. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:295-297.

- Tongdee E, Markowitz O. Mobile app rankings in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102:252-256.

- Kirby JS, Adgerson CN, Anderson BE. A survey of dermatology resident education in cosmetic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e23-e28.

- Waldman A, Sobanko JF, Alam M. Practice and educational gaps in cosmetic dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:341-346.

- Nielson CB, Harb JN, Motaparthi K. Education in cosmetic procedural dermatology: resident experiences and perceptions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:E70-E72.

- Hanna MG, Parwani AV, Pantanowitz L, et al. Smartphone applications: a contemporary resource for dermatopathology. J Pathol Inform. 2015;6:44.

With today’s technology, it is easier than ever to access web-based tools that enrich traditional dermatology education. The literature supports the use of these innovative platforms to enhance learning at the student and trainee levels. A controlled study of pediatric residents showed that online modules effectively supplemented clinical experience with atopic dermatitis.1 In a randomized diagnostic study of medical students, practice with an image-based web application (app) that teaches rapid recognition of melanoma proved more effective than learning a rule-based algorithm.2 Given the visual nature of dermatology, pattern recognition is an essential skill that is fostered through experience and is only made more accessible with technology.

With the added benefit of convenience and accessibility, mobile apps can supplement experiential learning. Mirroring the overall growth of mobile apps, the number of available dermatology apps has increased.3 Dermatology mobile apps serve purposes ranging from quick reference tools to comprehensive modules, journals, and question banks. At an academic hospital in Taiwan, both nondermatology and dermatology trainees’ examination performance improved after 3 weeks of using a smartphone-based wallpaper learning module displaying morphologic characteristics of fungi.4 With the expansion of virtual microscopy, mobile apps also have been created as a learning tool for dermatopathology, giving trainees the flexibility and autonomy to view slides on their own time.5 Nevertheless, the literature on dermatology mobile apps designed for the education of medical students and trainees is limited, demonstrating a need for further investigation.

Prior studies have reviewed dermatology apps for patients and practicing dermatologists.6-8 Herein, we focus on mobile apps targeting students and residents learning dermatology. General dermatology reference apps and educational aid apps have grown by 33% and 32%, respectively, from 2014 to 2017.3 As with any resource meant to educate future and current medical providers, there must be an objective review process in place to ensure accurate, unbiased, evidence-based teaching.

Well-organized, comprehensive information and a user-friendly interface are additional factors of importance when selecting an educational mobile app. When discussing supplemental resources, accessibility and affordability also are priorities given the high cost of a medical education at baseline. Overall, there is a need for a standardized method to evaluate the key factors of an educational mobile app that make it appropriate for this demographic. We conducted a search of mobile apps relating to dermatology education for students and residents.

Methods

We searched for publicly available mobile apps relating to dermatology education in the App Store (Apple Inc) from September to November 2019 using the search terms dermatology education, dermoscopy education, melanoma education, skin cancer education, psoriasis education, rosacea education, acne education, eczema education, dermal fillers education, and Mohs surgery education. We excluded apps that were not in English, were created for a conference, cost more than $5 to download, or did not include a specific dermatology education section. In this way, we hoped to evaluate apps that were relevant, accessible, and affordable.

We modeled our study after a review of patient education apps performed by Masud et al6 and utilized their quantified grading rubric (scale of 1 to 4). We found their established criteria—educational objectives, content, accuracy, design, and conflict of interest—to be equally applicable for evaluating apps designed for professional education.6 Each app earned a minimum of 1 point and a maximum of 4 points per criterion. One point was given if the app did not fulfill the criterion, 2 points for minimally fulfilling the criterion, 3 points for mostly fulfilling the criterion, and 4 points if the criterion was completely fulfilled. Two medical students (E.H. and N.C.)—one at the preclinical stage and the other at the clinical stage of medical education—reviewed the apps using the given rubric, then discussed and resolved any discrepancies in points assigned. A dermatology resident (M.A.) independently reviewed the apps using the given rubric.

The mean of the student score and the resident score was calculated for each category. The sum of the averages for each category was considered the final score for an app, determining its overall quality. Apps with a total score of 5 to 10 were considered poor and inadequate for education. A total score of 10.5 to 15 indicated that an app was somewhat adequate (ie, useful for education in some aspects but falling short in others). Apps that were considered adequate for education, across all or most criteria, received a total score ranging from 15.5 to 20.

Results

Our search generated 130 apps. After applying exclusion criteria, 42 apps were eligible for review. At the time of publication, 36 of these apps were still available. The possible range of scores based on the rubric was 5 to 20. The actual range of scores was 7 to 20. Of the 36 apps, 2 (5.6%) were poor, 16 (44.4%) were somewhat adequate, and 18 (50%) were adequate. Formats included primary resources, such as clinical decision support tools, journals, references, and a podcast (Table 1). Additionally, interactive learning tools included games, learning modules, and apps for self-evaluation (Table 2). Thirty apps covered general dermatology; others focused on skin cancer (n=5) and cosmetic dermatology (n=1). Regarding cost, 29 apps were free to download, whereas 7 charged a fee (mean price, $2.56).

Comment

In addition to the convenience of having an educational tool in their white-coat pocket, learners of dermatology have been shown to benefit from supplementing their curriculum with mobile apps, which sets the stage for formal integration of mobile apps into dermatology teaching in the future.8 Prior to widespread adoption, mobile apps must be evaluated for content and utility, starting with an objective rubric.

Without official scientific standards in place, it was unsurprising that only half of the dermatology education applications were classified as adequate in this study. Among the types of apps offered—clinical decision support tools, journals, references, podcast, games, learning modules, and self-evaluation—certain categories scored higher than others. App formats with the highest average score (16.5 out of 20) were journals and podcast.

One barrier to utilization of these apps was that a subscription to the journals and podcast was required to obtain access to all available content. Students and trainees can seek out library resources at their academic institutions to take advantage of journal subscriptions available to them at no additional cost. Dermatology residents can take advantage of their complimentary membership in the American Academy of Dermatology for a free subscription to AAD Dialogues in Dermatology (otherwise $179 annually for nonresident members and $320 annually for nonmembers).

On the other hand, learning module was the lowest-rated format (average score, 11.3 out of 20), with only Medical Student: Dermatology qualifying as adequate (total score, 16). This finding is worrisome given that students and residents might look to learning modules for quick targeted lessons on specific topics.

The lowest-scoring app, a clinical decision support tool called Naturelize, received a total score of 7. Although it listed the indications and contraindications for dermal filler types to be used in different locations on the face, there was a clear conflict of interest, oversimplified design, and little evidence-based education, mirroring the current state of cosmetic dermatology training in residency, in which trainees think they are inadequately prepared for aesthetic procedures and comparative effectiveness research is lacking.9-11

At the opposite end of the spectrum, MyDermPath+ was a reference app with a total score of 20. The app cited credible authors with a medical degree (MD) and had an easy-to-use, well-designed interface, including a reference guide, differential builder, and quiz for a range of topics within dermatology. As a free download without in-app purchases or advertisements, there was no evidence of conflict of interest. The position of a dermatopathology app as the top dermatology education mobile app might reflect an increased emphasis on dermatopathology education in residency as well as a transition to digitization of slides.5

The second-highest scoring apps (total score of 19 points) were Dermatology Database and VisualDx. Both were references covering a wide range of dermatology topics. Dermatology Database was a comprehensive search tool for diseases, drugs, procedures, and terms that was simple and entirely free to use but did not cite references. VisualDx, as its name suggests, offered quality clinical images, complete guides with references, and a unique differential builder. An annual subscription is $399.99, but the process to gain free access through a participating academic institution was simple.

Games were a unique mobile app format; however, 2 of 3 games scored in the somewhat adequate range. The game DiagnosUs, which tested users’ ability to differentiate skin cancer and psoriasis from dermatitis on clinical images, would benefit from more comprehensive content as well as professional verification of true diagnoses, which earned the app 2 points in both the content and accuracy categories. The Unusual Suspects tested the ABCDE algorithm in a short learning module, followed by a simple game that involved identification of melanoma in a timed setting. Although the design was novel and interactive, the game was limited to the same 5 melanoma tumors overlaid on pictures of normal skin. The narrow scope earned 1 point for content, the redundancy in the game earned 3 points for design, and the lack of real clinical images earned 2 points for educational objectives. Although game-format mobile apps have the capability to challenge the user’s knowledge with a built-in feedback or reward system, improvements should be made to ensure that apps are equally educational as they are engaging.