User login

Fingernail Abnormalities in an Adolescent With a History of Toe Walking

Fingernail Abnormalities in an Adolescent With a History of Toe Walking

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail-Patella Syndrome

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is an autosomaldominant disorder that is present in approximately 1 in 50,000 live births worldwide.1,2 It manifests with a spectrum of clinical findings affecting the nails, skeletal system, kidneys, and eyes.3 Most cases of NPS are caused by loss-of-function mutations in LMX1B,1 a gene encoding the LIM homeobox transcription factor.4 The LMX1B gene plays a critical role in the dorsoventral patterning of developing limbs.5 Mutations of this gene impair the development and function of podocytes and glomerular filtration slits6 and have been found to affect the development of the dopaminergic and mesencephalic serotoninergic neurons.2 Approximately 5% of patients with NPS have an unexplained genetic cause, suggesting an alternate mechanism for disease.1 Loss-of-function mutations also were observed in the Wnt inhibitory factor 1 gene (WIF1) in a family with an NPS-like presentation and could represent a novel cause of the condition.1 Regardless, NPS may be diagnosed clinically based on characteristic medical history, imaging, and physical examination findings.

Nail changes are the most consistent feature of NPS. The nails may be absent, hypoplastic, dystrophic, ridged (horizontally or vertically), or pitted or may demonstrate characteristic triangular lacunae. Nail findings often are congenital, bilateral, and symmetrical. The first digits typically are most severely affected, with progressive improvement appreciated toward the fifth fingers, as seen in our patient. The nail changes can be subtle, sometimes manifesting only as a single triangular lacuna on both thumbnails. Toenail involvement is less common and, when present, tends to be even more discreet. In contrast to the fingernails, the fifth toenails are most commonly affected.7

There are many skeletal manifestations of NPS. Patellae may be absent, hypoplastic, or irregularly shaped on physical examination or imaging, and changes may involve one or both knees. The Figure shows plain radiographs of the knees with bilateral patellar subluxation. Elbow dysplasia or radial head subluxation may result in physical limitations in extension, pronation, or supination of the joint.7 In approximately 70% of patients seen with the disorder, imaging may reveal symmetric posterior and lateral bony projections from the iliac crests, known as iliac horns; when present, these are considered pathognomonic.8

Open-angle glaucoma is the most common ocular finding in NPS. Other less commonly associated eye abnormalities include hyperpigmentation of the pupillary margin (Lester iris).6 Renal involvement occurs in 30% to 50% of patients with NPS and is the main predictor of mortality, with percentages as high as 5% to 14%.7 Defects occur in the glomerular basement membrane and manifest clinically with hematuria and/or proteinuria. The course of proteinuria is unpredictable. Some cases remit spontaneously, while others remain asymptomatic, progress to nephrotic syndrome, or, although rare, advance to renal failure.7,9

Bowel symptoms, neurologic problems, vasomotor concerns, thin dental enamel, attention-deficit disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and major depressive disorder all have been reported in association with NPS.2,7

Nail psoriasis typically exhibits nail pitting and onycholysis. Other manifestations include subungual hyperkeratosis, oil drop discoloration, and splinter hemorrhages. Topical and intralesional treatments are used to manage symptoms of the disease, as it can become debilitating if left untreated, unlike the nail disease seen in NPS.10 Onychomycosis can have a similar manifestation to psoriasis with sublingual hyperkeratosis of the nail, but it usually is caused by dermatophytes or yeasts such as Candida albicans. Onycholysis and thickening of the subungual region also can be seen. Diagnosis relies on direct microscopy and fungal culture, and a thorough patient history will help distinguish fungal vs nonfungal etiology. New-generation antifungals are used to eradicate the infection.11 Leukonychia manifests with white-appearing nails due to nail-plate or nail-bed abnormalities. Leukonychia can have multisystem involvement, but nails demonstrate a white discoloration rather than the other abnormalities discussed here.12 Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is a rare hereditary congenital disease that affects ectodermal structures and manifests with a triad of symptoms: hypotrichosis, hypohidrosis, and hypodontia. The condition often manifests in childhood with characteristic features such as light-pigmented sparse and fine hair. Physical growth as well as psychomotor development are within normal limits. Neither bone nor renal involvement is typical for hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.13

Our case highlights the typical manifestation of NPS with multisystem involvement, demonstrating the complexity of the disease. For cases in which a clinical diagnosis of NPS is uncertain, gene-targeted or comprehensive genomic testing is recommended, as well as genetic counseling. Given the broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, it is imperative that patients undergo screening for musculoskeletal, renal, and ophthalmologic involvement. Treatment is targeted at symptom management and prevention of long-term complications, reliant on clinical presentation, and specific to each patient.

- Jones MC, Topol SE, Rueda M, et al. Mutation of WIF1: a potential novel cause of a nail-patella–like disorder. Genet Med. 2017;19:1179-1183.

- López-Arvizu C, Sparrow EP, Strube MJ, et al. Increased symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and major depressive disorder symptoms in Nail-patella syndrome: potential association with LMX1B loss-of-function. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:59-66.

- Figueroa-Silva O, Vicente A, Agudo A, et al. Nail-patella syndrome: report of 11 pediatric cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016; 30:1614-1617.

- Vollrath D, Jaramillo-Babb VL, Clough MV, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the LIM-homeodomain gene, LMX1B, in nail-patella syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1091-1098. Published correction appears in Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1333.

- Chen H, Lun Y, Ovchinnikov D, et al. Limb and kidney defects in LMX1B mutant mice suggest an involvement of LMX1B in human nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:51-55.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Sweeney E, Hoover-Fong JE, McIntosh I. Nail-patella syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington; 2003.

- Tigchelaar S, Lenting A, Bongers EM, et al. Nail patella syndrome: knee symptoms and surgical outcomes. a questionnaire-based survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:959-962.

- Harita Y, Urae S, Akashio R, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of nephropathy in patients with nail-patella syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:1414-1421.

- Tan ES, Chong WS, Tey HL. Nail psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012; 13:375-388.

- Elewski BE. Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:415-429.

- Iorizzo M, Starace M, Pasch MC. Leukonychia: what can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:177-193.

- Wright JT, Grange DK, Fete M. Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail-Patella Syndrome

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is an autosomaldominant disorder that is present in approximately 1 in 50,000 live births worldwide.1,2 It manifests with a spectrum of clinical findings affecting the nails, skeletal system, kidneys, and eyes.3 Most cases of NPS are caused by loss-of-function mutations in LMX1B,1 a gene encoding the LIM homeobox transcription factor.4 The LMX1B gene plays a critical role in the dorsoventral patterning of developing limbs.5 Mutations of this gene impair the development and function of podocytes and glomerular filtration slits6 and have been found to affect the development of the dopaminergic and mesencephalic serotoninergic neurons.2 Approximately 5% of patients with NPS have an unexplained genetic cause, suggesting an alternate mechanism for disease.1 Loss-of-function mutations also were observed in the Wnt inhibitory factor 1 gene (WIF1) in a family with an NPS-like presentation and could represent a novel cause of the condition.1 Regardless, NPS may be diagnosed clinically based on characteristic medical history, imaging, and physical examination findings.

Nail changes are the most consistent feature of NPS. The nails may be absent, hypoplastic, dystrophic, ridged (horizontally or vertically), or pitted or may demonstrate characteristic triangular lacunae. Nail findings often are congenital, bilateral, and symmetrical. The first digits typically are most severely affected, with progressive improvement appreciated toward the fifth fingers, as seen in our patient. The nail changes can be subtle, sometimes manifesting only as a single triangular lacuna on both thumbnails. Toenail involvement is less common and, when present, tends to be even more discreet. In contrast to the fingernails, the fifth toenails are most commonly affected.7

There are many skeletal manifestations of NPS. Patellae may be absent, hypoplastic, or irregularly shaped on physical examination or imaging, and changes may involve one or both knees. The Figure shows plain radiographs of the knees with bilateral patellar subluxation. Elbow dysplasia or radial head subluxation may result in physical limitations in extension, pronation, or supination of the joint.7 In approximately 70% of patients seen with the disorder, imaging may reveal symmetric posterior and lateral bony projections from the iliac crests, known as iliac horns; when present, these are considered pathognomonic.8

Open-angle glaucoma is the most common ocular finding in NPS. Other less commonly associated eye abnormalities include hyperpigmentation of the pupillary margin (Lester iris).6 Renal involvement occurs in 30% to 50% of patients with NPS and is the main predictor of mortality, with percentages as high as 5% to 14%.7 Defects occur in the glomerular basement membrane and manifest clinically with hematuria and/or proteinuria. The course of proteinuria is unpredictable. Some cases remit spontaneously, while others remain asymptomatic, progress to nephrotic syndrome, or, although rare, advance to renal failure.7,9

Bowel symptoms, neurologic problems, vasomotor concerns, thin dental enamel, attention-deficit disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and major depressive disorder all have been reported in association with NPS.2,7

Nail psoriasis typically exhibits nail pitting and onycholysis. Other manifestations include subungual hyperkeratosis, oil drop discoloration, and splinter hemorrhages. Topical and intralesional treatments are used to manage symptoms of the disease, as it can become debilitating if left untreated, unlike the nail disease seen in NPS.10 Onychomycosis can have a similar manifestation to psoriasis with sublingual hyperkeratosis of the nail, but it usually is caused by dermatophytes or yeasts such as Candida albicans. Onycholysis and thickening of the subungual region also can be seen. Diagnosis relies on direct microscopy and fungal culture, and a thorough patient history will help distinguish fungal vs nonfungal etiology. New-generation antifungals are used to eradicate the infection.11 Leukonychia manifests with white-appearing nails due to nail-plate or nail-bed abnormalities. Leukonychia can have multisystem involvement, but nails demonstrate a white discoloration rather than the other abnormalities discussed here.12 Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is a rare hereditary congenital disease that affects ectodermal structures and manifests with a triad of symptoms: hypotrichosis, hypohidrosis, and hypodontia. The condition often manifests in childhood with characteristic features such as light-pigmented sparse and fine hair. Physical growth as well as psychomotor development are within normal limits. Neither bone nor renal involvement is typical for hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.13

Our case highlights the typical manifestation of NPS with multisystem involvement, demonstrating the complexity of the disease. For cases in which a clinical diagnosis of NPS is uncertain, gene-targeted or comprehensive genomic testing is recommended, as well as genetic counseling. Given the broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, it is imperative that patients undergo screening for musculoskeletal, renal, and ophthalmologic involvement. Treatment is targeted at symptom management and prevention of long-term complications, reliant on clinical presentation, and specific to each patient.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail-Patella Syndrome

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is an autosomaldominant disorder that is present in approximately 1 in 50,000 live births worldwide.1,2 It manifests with a spectrum of clinical findings affecting the nails, skeletal system, kidneys, and eyes.3 Most cases of NPS are caused by loss-of-function mutations in LMX1B,1 a gene encoding the LIM homeobox transcription factor.4 The LMX1B gene plays a critical role in the dorsoventral patterning of developing limbs.5 Mutations of this gene impair the development and function of podocytes and glomerular filtration slits6 and have been found to affect the development of the dopaminergic and mesencephalic serotoninergic neurons.2 Approximately 5% of patients with NPS have an unexplained genetic cause, suggesting an alternate mechanism for disease.1 Loss-of-function mutations also were observed in the Wnt inhibitory factor 1 gene (WIF1) in a family with an NPS-like presentation and could represent a novel cause of the condition.1 Regardless, NPS may be diagnosed clinically based on characteristic medical history, imaging, and physical examination findings.

Nail changes are the most consistent feature of NPS. The nails may be absent, hypoplastic, dystrophic, ridged (horizontally or vertically), or pitted or may demonstrate characteristic triangular lacunae. Nail findings often are congenital, bilateral, and symmetrical. The first digits typically are most severely affected, with progressive improvement appreciated toward the fifth fingers, as seen in our patient. The nail changes can be subtle, sometimes manifesting only as a single triangular lacuna on both thumbnails. Toenail involvement is less common and, when present, tends to be even more discreet. In contrast to the fingernails, the fifth toenails are most commonly affected.7

There are many skeletal manifestations of NPS. Patellae may be absent, hypoplastic, or irregularly shaped on physical examination or imaging, and changes may involve one or both knees. The Figure shows plain radiographs of the knees with bilateral patellar subluxation. Elbow dysplasia or radial head subluxation may result in physical limitations in extension, pronation, or supination of the joint.7 In approximately 70% of patients seen with the disorder, imaging may reveal symmetric posterior and lateral bony projections from the iliac crests, known as iliac horns; when present, these are considered pathognomonic.8

Open-angle glaucoma is the most common ocular finding in NPS. Other less commonly associated eye abnormalities include hyperpigmentation of the pupillary margin (Lester iris).6 Renal involvement occurs in 30% to 50% of patients with NPS and is the main predictor of mortality, with percentages as high as 5% to 14%.7 Defects occur in the glomerular basement membrane and manifest clinically with hematuria and/or proteinuria. The course of proteinuria is unpredictable. Some cases remit spontaneously, while others remain asymptomatic, progress to nephrotic syndrome, or, although rare, advance to renal failure.7,9

Bowel symptoms, neurologic problems, vasomotor concerns, thin dental enamel, attention-deficit disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and major depressive disorder all have been reported in association with NPS.2,7

Nail psoriasis typically exhibits nail pitting and onycholysis. Other manifestations include subungual hyperkeratosis, oil drop discoloration, and splinter hemorrhages. Topical and intralesional treatments are used to manage symptoms of the disease, as it can become debilitating if left untreated, unlike the nail disease seen in NPS.10 Onychomycosis can have a similar manifestation to psoriasis with sublingual hyperkeratosis of the nail, but it usually is caused by dermatophytes or yeasts such as Candida albicans. Onycholysis and thickening of the subungual region also can be seen. Diagnosis relies on direct microscopy and fungal culture, and a thorough patient history will help distinguish fungal vs nonfungal etiology. New-generation antifungals are used to eradicate the infection.11 Leukonychia manifests with white-appearing nails due to nail-plate or nail-bed abnormalities. Leukonychia can have multisystem involvement, but nails demonstrate a white discoloration rather than the other abnormalities discussed here.12 Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is a rare hereditary congenital disease that affects ectodermal structures and manifests with a triad of symptoms: hypotrichosis, hypohidrosis, and hypodontia. The condition often manifests in childhood with characteristic features such as light-pigmented sparse and fine hair. Physical growth as well as psychomotor development are within normal limits. Neither bone nor renal involvement is typical for hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.13

Our case highlights the typical manifestation of NPS with multisystem involvement, demonstrating the complexity of the disease. For cases in which a clinical diagnosis of NPS is uncertain, gene-targeted or comprehensive genomic testing is recommended, as well as genetic counseling. Given the broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, it is imperative that patients undergo screening for musculoskeletal, renal, and ophthalmologic involvement. Treatment is targeted at symptom management and prevention of long-term complications, reliant on clinical presentation, and specific to each patient.

- Jones MC, Topol SE, Rueda M, et al. Mutation of WIF1: a potential novel cause of a nail-patella–like disorder. Genet Med. 2017;19:1179-1183.

- López-Arvizu C, Sparrow EP, Strube MJ, et al. Increased symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and major depressive disorder symptoms in Nail-patella syndrome: potential association with LMX1B loss-of-function. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:59-66.

- Figueroa-Silva O, Vicente A, Agudo A, et al. Nail-patella syndrome: report of 11 pediatric cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016; 30:1614-1617.

- Vollrath D, Jaramillo-Babb VL, Clough MV, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the LIM-homeodomain gene, LMX1B, in nail-patella syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1091-1098. Published correction appears in Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1333.

- Chen H, Lun Y, Ovchinnikov D, et al. Limb and kidney defects in LMX1B mutant mice suggest an involvement of LMX1B in human nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:51-55.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Sweeney E, Hoover-Fong JE, McIntosh I. Nail-patella syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington; 2003.

- Tigchelaar S, Lenting A, Bongers EM, et al. Nail patella syndrome: knee symptoms and surgical outcomes. a questionnaire-based survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:959-962.

- Harita Y, Urae S, Akashio R, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of nephropathy in patients with nail-patella syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:1414-1421.

- Tan ES, Chong WS, Tey HL. Nail psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012; 13:375-388.

- Elewski BE. Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:415-429.

- Iorizzo M, Starace M, Pasch MC. Leukonychia: what can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:177-193.

- Wright JT, Grange DK, Fete M. Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024.

- Jones MC, Topol SE, Rueda M, et al. Mutation of WIF1: a potential novel cause of a nail-patella–like disorder. Genet Med. 2017;19:1179-1183.

- López-Arvizu C, Sparrow EP, Strube MJ, et al. Increased symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and major depressive disorder symptoms in Nail-patella syndrome: potential association with LMX1B loss-of-function. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:59-66.

- Figueroa-Silva O, Vicente A, Agudo A, et al. Nail-patella syndrome: report of 11 pediatric cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016; 30:1614-1617.

- Vollrath D, Jaramillo-Babb VL, Clough MV, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the LIM-homeodomain gene, LMX1B, in nail-patella syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1091-1098. Published correction appears in Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1333.

- Chen H, Lun Y, Ovchinnikov D, et al. Limb and kidney defects in LMX1B mutant mice suggest an involvement of LMX1B in human nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:51-55.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Sweeney E, Hoover-Fong JE, McIntosh I. Nail-patella syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington; 2003.

- Tigchelaar S, Lenting A, Bongers EM, et al. Nail patella syndrome: knee symptoms and surgical outcomes. a questionnaire-based survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:959-962.

- Harita Y, Urae S, Akashio R, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of nephropathy in patients with nail-patella syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:1414-1421.

- Tan ES, Chong WS, Tey HL. Nail psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012; 13:375-388.

- Elewski BE. Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:415-429.

- Iorizzo M, Starace M, Pasch MC. Leukonychia: what can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:177-193.

- Wright JT, Grange DK, Fete M. Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024.

Fingernail Abnormalities in an Adolescent With a History of Toe Walking

Fingernail Abnormalities in an Adolescent With a History of Toe Walking

A 14-year-old boy with a history of toe walking, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and mixed receptive expressive language disorder presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic with fingernail abnormalities that had been present since birth. Physical examination revealed narrowing and longitudinal splitting of the nail plates with triangular lacunae and progressive improvement appreciated toward the fifth digits. The nail changes were most prominent on the first digits. A review of the patient’s medical record revealed incidental bilateral iliac horns of the pelvis on radiographs taken at age 18 months. The patient reported waxing and waning knee pain that worsened with prolonged activity and when climbing stairs. Urinalysis demonstrated mild hematuria without proteinuria. The patient was normotensive. There was no evidence of glaucoma, cataracts, or hyperpigmentation of the pupillary margin (Lester iris) on ophthalmologic examination. Genetic testing was performed.

Symmetric Drug-Related Intertriginous and Flexural Exanthema

To the Editor:

Symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE) is a curious disorder that has undergone many clinical transformations since first being described by Andersen et al1 in 1984 using the term baboon syndrome. Initially described as a mercury hypersensitivity reaction resulting in an eruption resembling the red-bottomed baboon, this exanthema has expanded in definition with inciting agents, clinical features, and diagnostic criteria. Its prognosis, however, has remained stable and favorable throughout the decades. The condition is almost universally benign and self-limited.1-3 As new cases are reported in the literature and the paradigm of SDRIFE continues to shift, its prognosis also may warrant reconsideration and respect as a potentially destructive reaction.

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department after developing a rapidly evolving and blistering rash on the left flank. Hours later, the rash had progressed to a sharply demarcated, confluent, erythematous plaque with central ulceration and large flaccid bullae peripherally, encompassing 18% of total body surface area and extending from the gluteal cleft to the tip of the scapula along the left flank (Figure 1) with no vaginal or mucosal involvement. The patient recently had completed a 10-day course of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 2 days prior for a cat bite on the right dorsal wrist. Additional history confirmed the absence of prodromal fever, fatigue, or chills. Inciting trauma, including chemical and thermal burns, was denied. Potential underlying psychosocial cofounders were explored and were unrevealing.

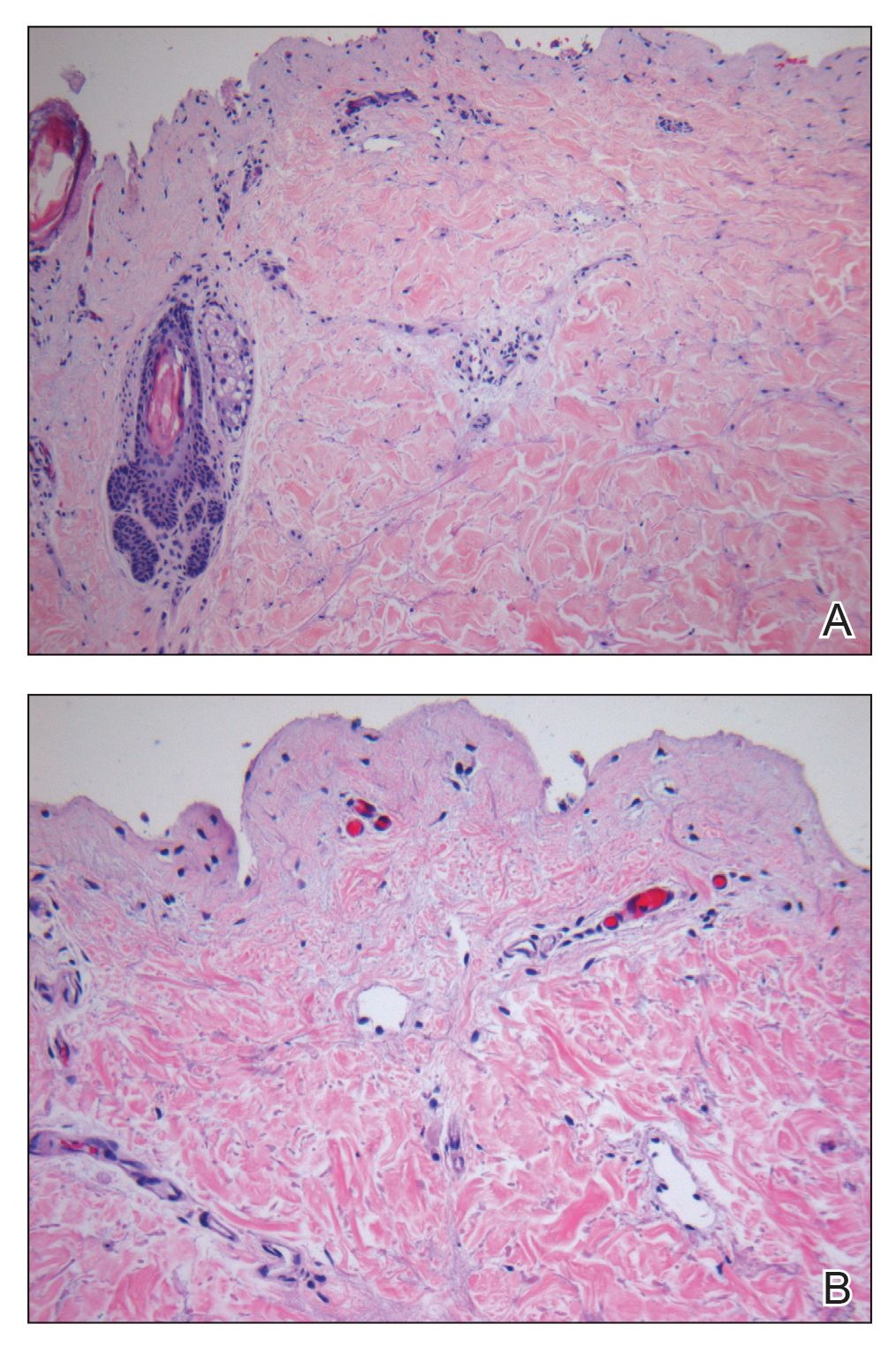

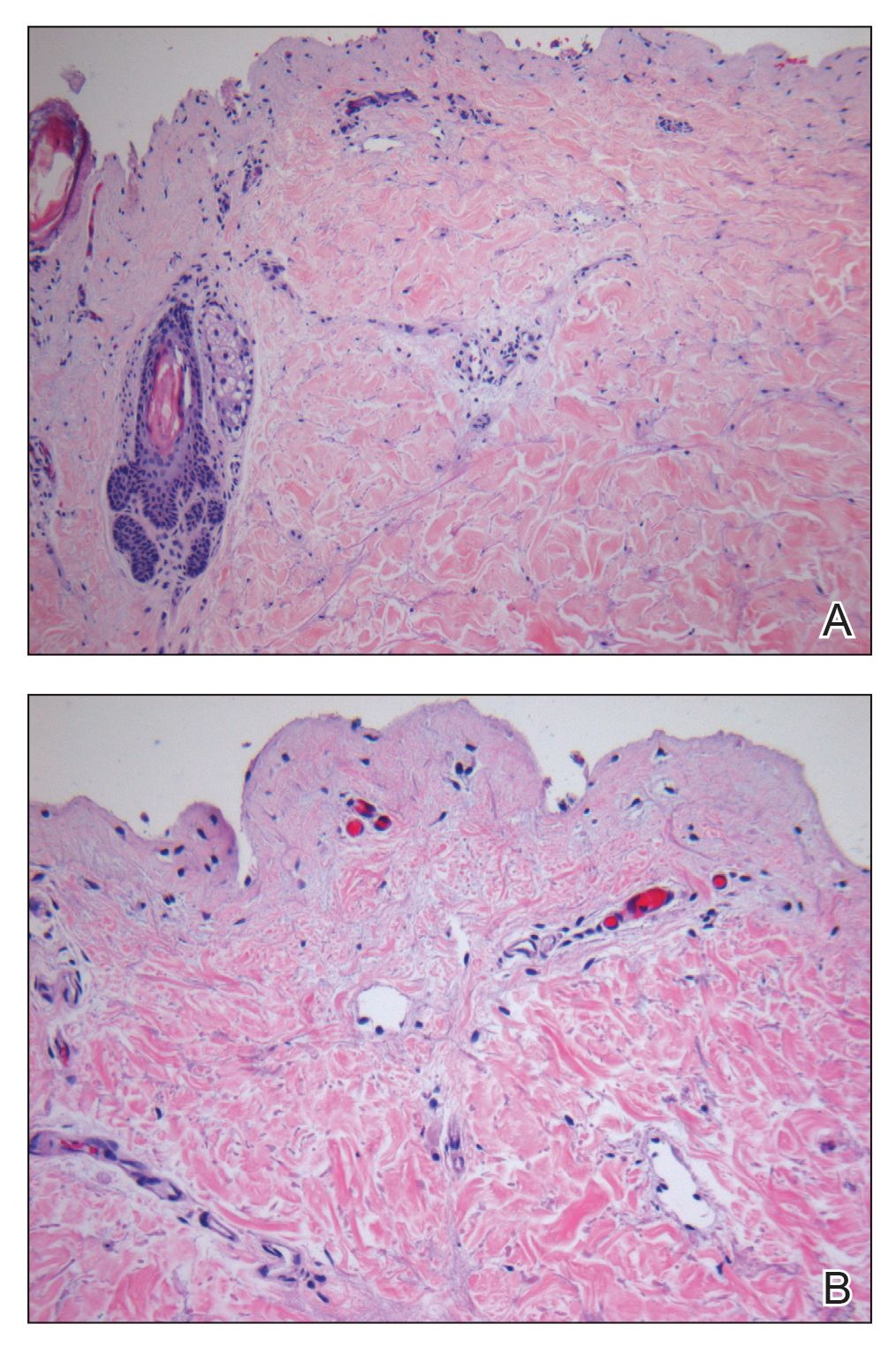

Laboratory test results, including complete blood cell count and metabolic panel as well as vital signs were unremarkable, except for slight leukocytosis at 14,000/µL (reference range 4500–11,000/µL). A punch biopsy was taken from the patient’s left upper back at the time of admission, which revealed a sparse, superficial, perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and rare neutrophils with largely absent epidermis and an occasional focal necrosis of adnexal epithelium (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence was negative for specific deposition of IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, or fibrinogen. Wound culture also returned negative, and the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale score was calculated to be 4 out of 12, indicating possible adverse drug reaction.4

Given the extent and distribution of the rash as well as the full-thickness dermal involvement, the patient was transferred to the burn unit for subsequent care. At 8-month follow-up, she experienced severe, symptomatic, hypertrophic scarring and was awaiting intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections. The patient subsequently was lost to follow up.

The clinical picture of SDRIFE has remained obscure over the last 30 years, likely owing to its rarity and unclear pathogenesis. Diagnostic criteria for SDRIFE were first proposed by Häusermann et al2 in 2004 and contained 5 elements: (1) occurrence after (re)exposure to systemic drugs, (2) sharply demarcated erythema of the gluteal region or V-shaped erythema of the inguinal area, (3) involvement of at least 1 other intertriginous location, (4) symmetry of affected areas, and (5) absence of systemic symptoms and signs. Based on these clinical criteria, our patients fulfilled 3 of 5 elements, with deductions for symmetry of affected areas and involvement of other intertriginous locations. Histopathologic findings in SDRIFE predominantly are nonspecific with superficial perivascular mononuclear infiltrates; however, prior reports have confirmed the potential for vacuolar changes and hydropic degeneration in the basal cell layer with subepidermal bullae formation.5,6 Similarly, although the presence of bullae are somewhat atypical in SDRIFE, it has been described.3 Taken together, we speculate that these findings may support a diagnosis of SDRIFE with atypical presentation, though an alternative diagnosis of bullous fixed drug eruption (FDE) cannot be ruled out.

Historically, SDRIFE has been associated with a benign course. The condition typically arises within a few hours to days following administration of the offending agent, most commonly amoxicillin or another β-lactam antibiotic.1 Most cases spontaneously resolve via desquamation within 1 to 2 weeks. We present an unusual case of amoxicillin-induced full-thickness epidermal necrosis resulting in symptomatic sequelae, which exhibits findings of SDRIFE, bullous FDE, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, suggesting the possibility for a common pathway underlying the pathogenesis of these conditions.

The diagnostic uncertainty that commonly accompanies these various toxic drug reactions may in part relate to their underlying immunopathogenesis. Although the exact mechanism by which SDRIFE results in its characteristic skin lesions has not been fully elucidated, prior work through patch testing, lymphocyte transformation assays, and immunohistochemical staining of biopsies suggests a type IV delayed hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction.7-10 Specifically, SDRIFE appears to share features of both DTH type IVa—involving CD4+ helper T cells (TH1), monocytes, and IFN-γ signaling—and DTH type IVc—involving cytotoxic CD4 and CD8 cells, granzyme B action, and FasL signaling.11,12 A similar inflammatory milieu has been implicated in numerous toxic drug eruptions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and FDE.11,13 This mechanistic overlap may explain the overlap seen clinically among such conditions.

In the undifferentiated patient, categorization of the clinical syndrome proves helpful in prognostication and therapeutic approach. The complexities and commonalities intrinsic to these syndromes, however, may simultaneously preclude certain cases from neatly following the predefined rules. These atypical presentations, while diagnostically challenging, can in turn offer a unique opportunity to reexamine the current state of disease understanding to better allow for appropriate classification.

Despite its rarity, SDRIFE should be considered in the differential of undiagnosed drug eruptions, particularly as new clinical presentations emerge. Careful documentation and timely declaration of future cases will prove invaluable for diagnostic and therapeutic advancements should this once-benign condition develop a more destructive potential.

- Andersen KE, Hjorth N, Menné T. The baboon syndrome: systemically-induced allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;10:97-100.

- Häusermann P, Harr TH, Bircher AJ. Baboon syndrome resulting from systemic drugs: is there strife between SDRIFE and allergic contact dermatitis syndrome? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:297-310.

- Tan SC, Tan JW. Symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:313-318.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Wolf R, Orion E, Matz H. The baboon syndrome or intertriginous drug eruption: a report of eleven cases and a second look at its pathomechanism. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:2.

- Elmariah SB, Cheung W, Wang N, et al. Systemic drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:3.

- Hembold P, Hegemann B, Dickert C, et al. Symptomatic psychotropic and nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption due to cimetidine (so-called baboon syndrome). Dermatology. 1998;197:402-403.

- Barbaud A, Trechot P, Granel F, et al. A baboon syndrome induced by intravenous human immunoglobulins: a report of a case and immunological analysis. Dermatology. 1999;199:258-260.

- Miyahara A, Kawashima H, Okubo Y, et al. A new proposal for a clinical-oriented subclassification of baboon syndrome and review of baboon syndrome. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29:150-160.

- Goossens C, Sass U, Song M. Baboon syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;194:421-422.

- Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:123-129.

- Ozkaya E. Current understanding of baboon syndrome. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2009;4:163-175.

- Ozakaya E. Fixed drug eruption: state of the art. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:181-188.

To the Editor:

Symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE) is a curious disorder that has undergone many clinical transformations since first being described by Andersen et al1 in 1984 using the term baboon syndrome. Initially described as a mercury hypersensitivity reaction resulting in an eruption resembling the red-bottomed baboon, this exanthema has expanded in definition with inciting agents, clinical features, and diagnostic criteria. Its prognosis, however, has remained stable and favorable throughout the decades. The condition is almost universally benign and self-limited.1-3 As new cases are reported in the literature and the paradigm of SDRIFE continues to shift, its prognosis also may warrant reconsideration and respect as a potentially destructive reaction.

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department after developing a rapidly evolving and blistering rash on the left flank. Hours later, the rash had progressed to a sharply demarcated, confluent, erythematous plaque with central ulceration and large flaccid bullae peripherally, encompassing 18% of total body surface area and extending from the gluteal cleft to the tip of the scapula along the left flank (Figure 1) with no vaginal or mucosal involvement. The patient recently had completed a 10-day course of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 2 days prior for a cat bite on the right dorsal wrist. Additional history confirmed the absence of prodromal fever, fatigue, or chills. Inciting trauma, including chemical and thermal burns, was denied. Potential underlying psychosocial cofounders were explored and were unrevealing.

Laboratory test results, including complete blood cell count and metabolic panel as well as vital signs were unremarkable, except for slight leukocytosis at 14,000/µL (reference range 4500–11,000/µL). A punch biopsy was taken from the patient’s left upper back at the time of admission, which revealed a sparse, superficial, perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and rare neutrophils with largely absent epidermis and an occasional focal necrosis of adnexal epithelium (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence was negative for specific deposition of IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, or fibrinogen. Wound culture also returned negative, and the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale score was calculated to be 4 out of 12, indicating possible adverse drug reaction.4

Given the extent and distribution of the rash as well as the full-thickness dermal involvement, the patient was transferred to the burn unit for subsequent care. At 8-month follow-up, she experienced severe, symptomatic, hypertrophic scarring and was awaiting intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections. The patient subsequently was lost to follow up.

The clinical picture of SDRIFE has remained obscure over the last 30 years, likely owing to its rarity and unclear pathogenesis. Diagnostic criteria for SDRIFE were first proposed by Häusermann et al2 in 2004 and contained 5 elements: (1) occurrence after (re)exposure to systemic drugs, (2) sharply demarcated erythema of the gluteal region or V-shaped erythema of the inguinal area, (3) involvement of at least 1 other intertriginous location, (4) symmetry of affected areas, and (5) absence of systemic symptoms and signs. Based on these clinical criteria, our patients fulfilled 3 of 5 elements, with deductions for symmetry of affected areas and involvement of other intertriginous locations. Histopathologic findings in SDRIFE predominantly are nonspecific with superficial perivascular mononuclear infiltrates; however, prior reports have confirmed the potential for vacuolar changes and hydropic degeneration in the basal cell layer with subepidermal bullae formation.5,6 Similarly, although the presence of bullae are somewhat atypical in SDRIFE, it has been described.3 Taken together, we speculate that these findings may support a diagnosis of SDRIFE with atypical presentation, though an alternative diagnosis of bullous fixed drug eruption (FDE) cannot be ruled out.

Historically, SDRIFE has been associated with a benign course. The condition typically arises within a few hours to days following administration of the offending agent, most commonly amoxicillin or another β-lactam antibiotic.1 Most cases spontaneously resolve via desquamation within 1 to 2 weeks. We present an unusual case of amoxicillin-induced full-thickness epidermal necrosis resulting in symptomatic sequelae, which exhibits findings of SDRIFE, bullous FDE, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, suggesting the possibility for a common pathway underlying the pathogenesis of these conditions.

The diagnostic uncertainty that commonly accompanies these various toxic drug reactions may in part relate to their underlying immunopathogenesis. Although the exact mechanism by which SDRIFE results in its characteristic skin lesions has not been fully elucidated, prior work through patch testing, lymphocyte transformation assays, and immunohistochemical staining of biopsies suggests a type IV delayed hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction.7-10 Specifically, SDRIFE appears to share features of both DTH type IVa—involving CD4+ helper T cells (TH1), monocytes, and IFN-γ signaling—and DTH type IVc—involving cytotoxic CD4 and CD8 cells, granzyme B action, and FasL signaling.11,12 A similar inflammatory milieu has been implicated in numerous toxic drug eruptions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and FDE.11,13 This mechanistic overlap may explain the overlap seen clinically among such conditions.

In the undifferentiated patient, categorization of the clinical syndrome proves helpful in prognostication and therapeutic approach. The complexities and commonalities intrinsic to these syndromes, however, may simultaneously preclude certain cases from neatly following the predefined rules. These atypical presentations, while diagnostically challenging, can in turn offer a unique opportunity to reexamine the current state of disease understanding to better allow for appropriate classification.

Despite its rarity, SDRIFE should be considered in the differential of undiagnosed drug eruptions, particularly as new clinical presentations emerge. Careful documentation and timely declaration of future cases will prove invaluable for diagnostic and therapeutic advancements should this once-benign condition develop a more destructive potential.

To the Editor:

Symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE) is a curious disorder that has undergone many clinical transformations since first being described by Andersen et al1 in 1984 using the term baboon syndrome. Initially described as a mercury hypersensitivity reaction resulting in an eruption resembling the red-bottomed baboon, this exanthema has expanded in definition with inciting agents, clinical features, and diagnostic criteria. Its prognosis, however, has remained stable and favorable throughout the decades. The condition is almost universally benign and self-limited.1-3 As new cases are reported in the literature and the paradigm of SDRIFE continues to shift, its prognosis also may warrant reconsideration and respect as a potentially destructive reaction.

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department after developing a rapidly evolving and blistering rash on the left flank. Hours later, the rash had progressed to a sharply demarcated, confluent, erythematous plaque with central ulceration and large flaccid bullae peripherally, encompassing 18% of total body surface area and extending from the gluteal cleft to the tip of the scapula along the left flank (Figure 1) with no vaginal or mucosal involvement. The patient recently had completed a 10-day course of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 2 days prior for a cat bite on the right dorsal wrist. Additional history confirmed the absence of prodromal fever, fatigue, or chills. Inciting trauma, including chemical and thermal burns, was denied. Potential underlying psychosocial cofounders were explored and were unrevealing.

Laboratory test results, including complete blood cell count and metabolic panel as well as vital signs were unremarkable, except for slight leukocytosis at 14,000/µL (reference range 4500–11,000/µL). A punch biopsy was taken from the patient’s left upper back at the time of admission, which revealed a sparse, superficial, perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and rare neutrophils with largely absent epidermis and an occasional focal necrosis of adnexal epithelium (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence was negative for specific deposition of IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, or fibrinogen. Wound culture also returned negative, and the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale score was calculated to be 4 out of 12, indicating possible adverse drug reaction.4

Given the extent and distribution of the rash as well as the full-thickness dermal involvement, the patient was transferred to the burn unit for subsequent care. At 8-month follow-up, she experienced severe, symptomatic, hypertrophic scarring and was awaiting intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections. The patient subsequently was lost to follow up.

The clinical picture of SDRIFE has remained obscure over the last 30 years, likely owing to its rarity and unclear pathogenesis. Diagnostic criteria for SDRIFE were first proposed by Häusermann et al2 in 2004 and contained 5 elements: (1) occurrence after (re)exposure to systemic drugs, (2) sharply demarcated erythema of the gluteal region or V-shaped erythema of the inguinal area, (3) involvement of at least 1 other intertriginous location, (4) symmetry of affected areas, and (5) absence of systemic symptoms and signs. Based on these clinical criteria, our patients fulfilled 3 of 5 elements, with deductions for symmetry of affected areas and involvement of other intertriginous locations. Histopathologic findings in SDRIFE predominantly are nonspecific with superficial perivascular mononuclear infiltrates; however, prior reports have confirmed the potential for vacuolar changes and hydropic degeneration in the basal cell layer with subepidermal bullae formation.5,6 Similarly, although the presence of bullae are somewhat atypical in SDRIFE, it has been described.3 Taken together, we speculate that these findings may support a diagnosis of SDRIFE with atypical presentation, though an alternative diagnosis of bullous fixed drug eruption (FDE) cannot be ruled out.

Historically, SDRIFE has been associated with a benign course. The condition typically arises within a few hours to days following administration of the offending agent, most commonly amoxicillin or another β-lactam antibiotic.1 Most cases spontaneously resolve via desquamation within 1 to 2 weeks. We present an unusual case of amoxicillin-induced full-thickness epidermal necrosis resulting in symptomatic sequelae, which exhibits findings of SDRIFE, bullous FDE, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, suggesting the possibility for a common pathway underlying the pathogenesis of these conditions.

The diagnostic uncertainty that commonly accompanies these various toxic drug reactions may in part relate to their underlying immunopathogenesis. Although the exact mechanism by which SDRIFE results in its characteristic skin lesions has not been fully elucidated, prior work through patch testing, lymphocyte transformation assays, and immunohistochemical staining of biopsies suggests a type IV delayed hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction.7-10 Specifically, SDRIFE appears to share features of both DTH type IVa—involving CD4+ helper T cells (TH1), monocytes, and IFN-γ signaling—and DTH type IVc—involving cytotoxic CD4 and CD8 cells, granzyme B action, and FasL signaling.11,12 A similar inflammatory milieu has been implicated in numerous toxic drug eruptions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and FDE.11,13 This mechanistic overlap may explain the overlap seen clinically among such conditions.

In the undifferentiated patient, categorization of the clinical syndrome proves helpful in prognostication and therapeutic approach. The complexities and commonalities intrinsic to these syndromes, however, may simultaneously preclude certain cases from neatly following the predefined rules. These atypical presentations, while diagnostically challenging, can in turn offer a unique opportunity to reexamine the current state of disease understanding to better allow for appropriate classification.

Despite its rarity, SDRIFE should be considered in the differential of undiagnosed drug eruptions, particularly as new clinical presentations emerge. Careful documentation and timely declaration of future cases will prove invaluable for diagnostic and therapeutic advancements should this once-benign condition develop a more destructive potential.

- Andersen KE, Hjorth N, Menné T. The baboon syndrome: systemically-induced allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;10:97-100.

- Häusermann P, Harr TH, Bircher AJ. Baboon syndrome resulting from systemic drugs: is there strife between SDRIFE and allergic contact dermatitis syndrome? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:297-310.

- Tan SC, Tan JW. Symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:313-318.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Wolf R, Orion E, Matz H. The baboon syndrome or intertriginous drug eruption: a report of eleven cases and a second look at its pathomechanism. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:2.

- Elmariah SB, Cheung W, Wang N, et al. Systemic drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:3.

- Hembold P, Hegemann B, Dickert C, et al. Symptomatic psychotropic and nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption due to cimetidine (so-called baboon syndrome). Dermatology. 1998;197:402-403.

- Barbaud A, Trechot P, Granel F, et al. A baboon syndrome induced by intravenous human immunoglobulins: a report of a case and immunological analysis. Dermatology. 1999;199:258-260.

- Miyahara A, Kawashima H, Okubo Y, et al. A new proposal for a clinical-oriented subclassification of baboon syndrome and review of baboon syndrome. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29:150-160.

- Goossens C, Sass U, Song M. Baboon syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;194:421-422.

- Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:123-129.

- Ozkaya E. Current understanding of baboon syndrome. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2009;4:163-175.

- Ozakaya E. Fixed drug eruption: state of the art. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:181-188.

- Andersen KE, Hjorth N, Menné T. The baboon syndrome: systemically-induced allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;10:97-100.

- Häusermann P, Harr TH, Bircher AJ. Baboon syndrome resulting from systemic drugs: is there strife between SDRIFE and allergic contact dermatitis syndrome? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:297-310.

- Tan SC, Tan JW. Symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:313-318.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Wolf R, Orion E, Matz H. The baboon syndrome or intertriginous drug eruption: a report of eleven cases and a second look at its pathomechanism. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:2.

- Elmariah SB, Cheung W, Wang N, et al. Systemic drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:3.

- Hembold P, Hegemann B, Dickert C, et al. Symptomatic psychotropic and nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption due to cimetidine (so-called baboon syndrome). Dermatology. 1998;197:402-403.

- Barbaud A, Trechot P, Granel F, et al. A baboon syndrome induced by intravenous human immunoglobulins: a report of a case and immunological analysis. Dermatology. 1999;199:258-260.

- Miyahara A, Kawashima H, Okubo Y, et al. A new proposal for a clinical-oriented subclassification of baboon syndrome and review of baboon syndrome. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29:150-160.

- Goossens C, Sass U, Song M. Baboon syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;194:421-422.

- Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:123-129.

- Ozkaya E. Current understanding of baboon syndrome. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2009;4:163-175.

- Ozakaya E. Fixed drug eruption: state of the art. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:181-188.

Practice Points

- Symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE) appears in the absence of systemic signs and symptoms such as fever, which may help differentiate it from infectious causes.

- β-Lactam antibiotics, particularly amoxicillin, are common offenders in the pathogenesis of SDRIFE, but new drug relationships frequently are being described.

- Symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema commonly follows a benign course but warrants respect, as it may have devastating potential.

Red-Brown Plaque on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

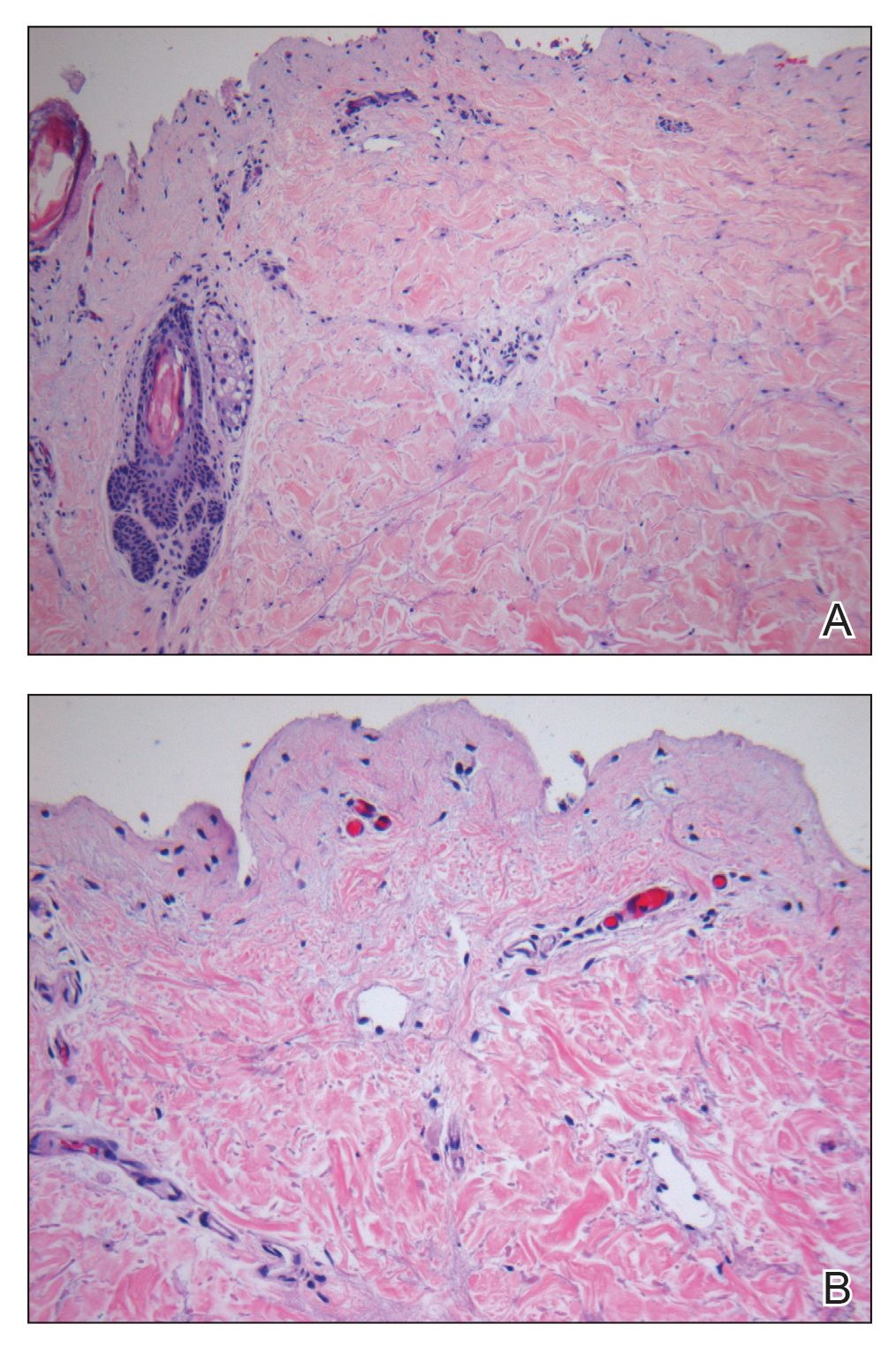

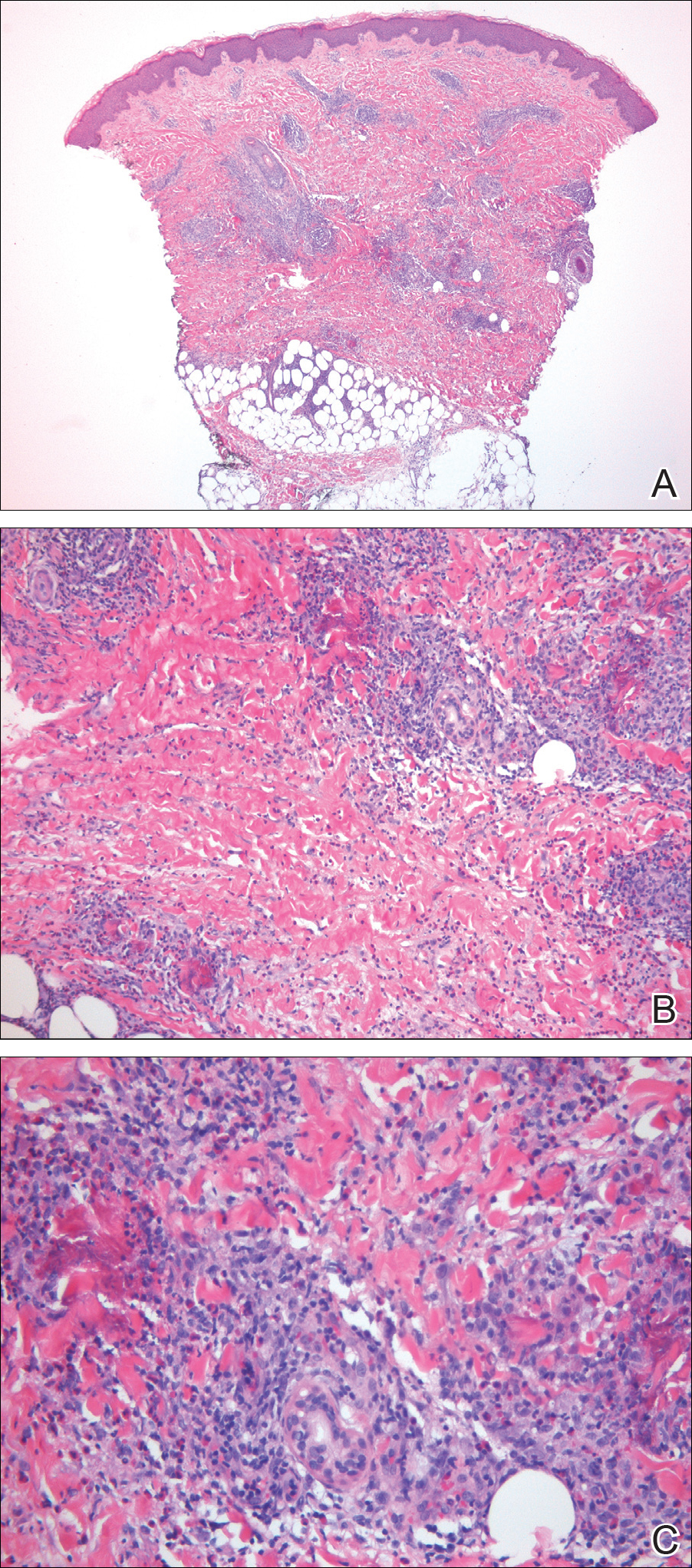

A punch biopsy taken from the perimeter of the lesion demonstrated mild spongiosis overlying a dense nodular to diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils, some involving underlying fat lobules (Figure, A and B). In some areas, eosinophilic degeneration of collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of histiocytes, "flame features," were observed (Figure C). The clinical and histological features were consistent with Wells syndrome (WS), also known as eosinophilic cellulitis. Given the localized mild nature of the disease, the patient was started on a midpotency topical corticosteroid.

Wells syndrome is a rare inflammatory condition characterized by clinical polymorphism, suggestive histologic findings, and a recurrent course.1,2 This condition is especially rare in children.3,4 Caputo et al1 described 7 variants in their case series of 19 patients: classic plaque-type variant (the most common clinical presentation in children); annular granuloma-like (the most common clinical presentation in adults); urticarialike; bullous; papulonodular; papulovesicular; and fixed drug eruption-like. Wells syndrome is thought to result from excess production of IL-5 in response to a hypersensitivity reaction to an exogenous or endogenous circulating antigen.3,4 Increased levels of IL-5 enhance eosinophil accumulation in the skin, degranulation, and subsequent tissue destruction.3,4 Reported triggers include insect bites, viral and bacterial infections, drug eruptions, recent vaccination, and paraphenylenediamine in henna tattoos.3-7 Additionally, WS has been reported in the setting of gastrointestinal pathologies, such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, and with asthma exacerbations.8,9 However, in half of pediatric cases, no trigger can be identified.7

Clinically, WS presents with pruritic, mildly tender plaques.7 Lesions may be localized or diffuse and range from mild annular or circinate plaques with infiltrated borders to cellulitic-appearing lesions that are occasionally associated with bullae.5,6 Patients often report prodromal symptoms of burning and pruritus.5,6 Lesions rapidly progress over 2 to 3 days, pass through a blue grayish discoloration phase, and gradually resolve over 2 to 8 weeks.5,6,10 Although patients generally heal without scarring, WS lesions have been described to resolve with atrophy and hyperpigmentation resembling morphea.5-7 Additionally, patients typically experience a relapsing remitting course over months to years with eventual spontaneous resolution.1,5 Patients also may experience systemic symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, though they do not develop more widespread systemic manifestations.2,3,7

Diagnosis of WS is based on clinicopathologic correlation. Histopathology of WS lesions demonstrates 3 phases. The acute phase demonstrates edema of the superficial and mid dermis with a dense dermal eosinophilic infiltrate.1,6,10 The subacute granulomatous phase demonstrates flame figures in the dermis.1,2,6,7,10 Flame figures consist of palisading groups of eosinophils and histiocytes around a core of degenerating basophilic collagen bundles associated with major basic protein.1,2,6,7,10 Finally, in the resolution phase, eosinophils gradually disappear while histiocytes and giant cells persist, forming microgranulomas.1,2,10 Notably, no vasculitis is observed and direct immunofluorescence is negative.3,7 Although flame figures are suggestive of WS, they are not pathognomonic and are observed in other conditions including Churg-Strauss syndrome, parasitic and fungal infections, herpes gestationis, bullous pemphigoid, and follicular mucinosis.2,5

Wells syndrome is a self-resolving and benign condition.1,10 Physicians are recommended to gather a complete history including review of medications and vaccinations; a history of insect bites, infections, and asthma; laboratory workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential and stool samples for ova and parasites; and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is unclear.7 Identification and treatment of underlying causes often results in resolution.6 Systemic corticosteroids frequently are used in both adult and pediatric patients, though practitioners should consider alternative treatments when recurrences occur to avoid steroid side effects.3,6 Midpotency topical corticosteroids present a safe alternative to systemic corticosteroids in the pediatric population, especially in cases of localized WS without systemic symptoms.3 Other medications reported in the literature include cyclosporine, dapsone, antimalarial medications, and azathioprine.6 Despite appropriate therapy, patients and physicians should anticipate recurrence over months to years.1,6

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Smith SM, Kiracofe EA, Clark LN, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with cutaneous manifestations and flame figures: a spectrum of eosinophilic dermatoses whose features overlap with Wells' syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:910-914.

- Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, et al. Bullous "cellulitis" with eosinophilia: case report and review of Wells' syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E149-E155.

- Nacaroglu HT, Celegen M, Karkıner CS, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome) caused by a temporary henna tattoo. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:322-324.

- Heelan K, Ryan JF, Shear NH, et al. Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): proposed diagnostic criteria and a literature review of the drug-induced variant. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:113-120.

- Sinno H, Lacroix JP, Lee J, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:91-97.

- Cherng E, McClung AA, Rosenthal HM, et al. Wells' syndrome associated with parvovirus in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:762-764.

- Eren M, Açikalin M. A case report of Wells' syndrome in a celiac patient. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:172-174.

- Cruz MJ, Mota A, Baudrier T, et al. Recurrent Wells' syndrome associated with allergic asthma exacerbation. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:154-156.

- Van der Straaten S, Wojciechowski M, Salgado R, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells' syndrome in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:197-198.

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

A punch biopsy taken from the perimeter of the lesion demonstrated mild spongiosis overlying a dense nodular to diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils, some involving underlying fat lobules (Figure, A and B). In some areas, eosinophilic degeneration of collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of histiocytes, "flame features," were observed (Figure C). The clinical and histological features were consistent with Wells syndrome (WS), also known as eosinophilic cellulitis. Given the localized mild nature of the disease, the patient was started on a midpotency topical corticosteroid.

Wells syndrome is a rare inflammatory condition characterized by clinical polymorphism, suggestive histologic findings, and a recurrent course.1,2 This condition is especially rare in children.3,4 Caputo et al1 described 7 variants in their case series of 19 patients: classic plaque-type variant (the most common clinical presentation in children); annular granuloma-like (the most common clinical presentation in adults); urticarialike; bullous; papulonodular; papulovesicular; and fixed drug eruption-like. Wells syndrome is thought to result from excess production of IL-5 in response to a hypersensitivity reaction to an exogenous or endogenous circulating antigen.3,4 Increased levels of IL-5 enhance eosinophil accumulation in the skin, degranulation, and subsequent tissue destruction.3,4 Reported triggers include insect bites, viral and bacterial infections, drug eruptions, recent vaccination, and paraphenylenediamine in henna tattoos.3-7 Additionally, WS has been reported in the setting of gastrointestinal pathologies, such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, and with asthma exacerbations.8,9 However, in half of pediatric cases, no trigger can be identified.7

Clinically, WS presents with pruritic, mildly tender plaques.7 Lesions may be localized or diffuse and range from mild annular or circinate plaques with infiltrated borders to cellulitic-appearing lesions that are occasionally associated with bullae.5,6 Patients often report prodromal symptoms of burning and pruritus.5,6 Lesions rapidly progress over 2 to 3 days, pass through a blue grayish discoloration phase, and gradually resolve over 2 to 8 weeks.5,6,10 Although patients generally heal without scarring, WS lesions have been described to resolve with atrophy and hyperpigmentation resembling morphea.5-7 Additionally, patients typically experience a relapsing remitting course over months to years with eventual spontaneous resolution.1,5 Patients also may experience systemic symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, though they do not develop more widespread systemic manifestations.2,3,7

Diagnosis of WS is based on clinicopathologic correlation. Histopathology of WS lesions demonstrates 3 phases. The acute phase demonstrates edema of the superficial and mid dermis with a dense dermal eosinophilic infiltrate.1,6,10 The subacute granulomatous phase demonstrates flame figures in the dermis.1,2,6,7,10 Flame figures consist of palisading groups of eosinophils and histiocytes around a core of degenerating basophilic collagen bundles associated with major basic protein.1,2,6,7,10 Finally, in the resolution phase, eosinophils gradually disappear while histiocytes and giant cells persist, forming microgranulomas.1,2,10 Notably, no vasculitis is observed and direct immunofluorescence is negative.3,7 Although flame figures are suggestive of WS, they are not pathognomonic and are observed in other conditions including Churg-Strauss syndrome, parasitic and fungal infections, herpes gestationis, bullous pemphigoid, and follicular mucinosis.2,5

Wells syndrome is a self-resolving and benign condition.1,10 Physicians are recommended to gather a complete history including review of medications and vaccinations; a history of insect bites, infections, and asthma; laboratory workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential and stool samples for ova and parasites; and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is unclear.7 Identification and treatment of underlying causes often results in resolution.6 Systemic corticosteroids frequently are used in both adult and pediatric patients, though practitioners should consider alternative treatments when recurrences occur to avoid steroid side effects.3,6 Midpotency topical corticosteroids present a safe alternative to systemic corticosteroids in the pediatric population, especially in cases of localized WS without systemic symptoms.3 Other medications reported in the literature include cyclosporine, dapsone, antimalarial medications, and azathioprine.6 Despite appropriate therapy, patients and physicians should anticipate recurrence over months to years.1,6

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

A punch biopsy taken from the perimeter of the lesion demonstrated mild spongiosis overlying a dense nodular to diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils, some involving underlying fat lobules (Figure, A and B). In some areas, eosinophilic degeneration of collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of histiocytes, "flame features," were observed (Figure C). The clinical and histological features were consistent with Wells syndrome (WS), also known as eosinophilic cellulitis. Given the localized mild nature of the disease, the patient was started on a midpotency topical corticosteroid.

Wells syndrome is a rare inflammatory condition characterized by clinical polymorphism, suggestive histologic findings, and a recurrent course.1,2 This condition is especially rare in children.3,4 Caputo et al1 described 7 variants in their case series of 19 patients: classic plaque-type variant (the most common clinical presentation in children); annular granuloma-like (the most common clinical presentation in adults); urticarialike; bullous; papulonodular; papulovesicular; and fixed drug eruption-like. Wells syndrome is thought to result from excess production of IL-5 in response to a hypersensitivity reaction to an exogenous or endogenous circulating antigen.3,4 Increased levels of IL-5 enhance eosinophil accumulation in the skin, degranulation, and subsequent tissue destruction.3,4 Reported triggers include insect bites, viral and bacterial infections, drug eruptions, recent vaccination, and paraphenylenediamine in henna tattoos.3-7 Additionally, WS has been reported in the setting of gastrointestinal pathologies, such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, and with asthma exacerbations.8,9 However, in half of pediatric cases, no trigger can be identified.7

Clinically, WS presents with pruritic, mildly tender plaques.7 Lesions may be localized or diffuse and range from mild annular or circinate plaques with infiltrated borders to cellulitic-appearing lesions that are occasionally associated with bullae.5,6 Patients often report prodromal symptoms of burning and pruritus.5,6 Lesions rapidly progress over 2 to 3 days, pass through a blue grayish discoloration phase, and gradually resolve over 2 to 8 weeks.5,6,10 Although patients generally heal without scarring, WS lesions have been described to resolve with atrophy and hyperpigmentation resembling morphea.5-7 Additionally, patients typically experience a relapsing remitting course over months to years with eventual spontaneous resolution.1,5 Patients also may experience systemic symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, though they do not develop more widespread systemic manifestations.2,3,7

Diagnosis of WS is based on clinicopathologic correlation. Histopathology of WS lesions demonstrates 3 phases. The acute phase demonstrates edema of the superficial and mid dermis with a dense dermal eosinophilic infiltrate.1,6,10 The subacute granulomatous phase demonstrates flame figures in the dermis.1,2,6,7,10 Flame figures consist of palisading groups of eosinophils and histiocytes around a core of degenerating basophilic collagen bundles associated with major basic protein.1,2,6,7,10 Finally, in the resolution phase, eosinophils gradually disappear while histiocytes and giant cells persist, forming microgranulomas.1,2,10 Notably, no vasculitis is observed and direct immunofluorescence is negative.3,7 Although flame figures are suggestive of WS, they are not pathognomonic and are observed in other conditions including Churg-Strauss syndrome, parasitic and fungal infections, herpes gestationis, bullous pemphigoid, and follicular mucinosis.2,5

Wells syndrome is a self-resolving and benign condition.1,10 Physicians are recommended to gather a complete history including review of medications and vaccinations; a history of insect bites, infections, and asthma; laboratory workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential and stool samples for ova and parasites; and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is unclear.7 Identification and treatment of underlying causes often results in resolution.6 Systemic corticosteroids frequently are used in both adult and pediatric patients, though practitioners should consider alternative treatments when recurrences occur to avoid steroid side effects.3,6 Midpotency topical corticosteroids present a safe alternative to systemic corticosteroids in the pediatric population, especially in cases of localized WS without systemic symptoms.3 Other medications reported in the literature include cyclosporine, dapsone, antimalarial medications, and azathioprine.6 Despite appropriate therapy, patients and physicians should anticipate recurrence over months to years.1,6

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Smith SM, Kiracofe EA, Clark LN, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with cutaneous manifestations and flame figures: a spectrum of eosinophilic dermatoses whose features overlap with Wells' syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:910-914.

- Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, et al. Bullous "cellulitis" with eosinophilia: case report and review of Wells' syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E149-E155.

- Nacaroglu HT, Celegen M, Karkıner CS, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome) caused by a temporary henna tattoo. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:322-324.

- Heelan K, Ryan JF, Shear NH, et al. Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): proposed diagnostic criteria and a literature review of the drug-induced variant. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:113-120.

- Sinno H, Lacroix JP, Lee J, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:91-97.

- Cherng E, McClung AA, Rosenthal HM, et al. Wells' syndrome associated with parvovirus in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:762-764.

- Eren M, Açikalin M. A case report of Wells' syndrome in a celiac patient. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:172-174.

- Cruz MJ, Mota A, Baudrier T, et al. Recurrent Wells' syndrome associated with allergic asthma exacerbation. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:154-156.

- Van der Straaten S, Wojciechowski M, Salgado R, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells' syndrome in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:197-198.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Smith SM, Kiracofe EA, Clark LN, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with cutaneous manifestations and flame figures: a spectrum of eosinophilic dermatoses whose features overlap with Wells' syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:910-914.

- Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, et al. Bullous "cellulitis" with eosinophilia: case report and review of Wells' syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E149-E155.

- Nacaroglu HT, Celegen M, Karkıner CS, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome) caused by a temporary henna tattoo. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:322-324.

- Heelan K, Ryan JF, Shear NH, et al. Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): proposed diagnostic criteria and a literature review of the drug-induced variant. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:113-120.

- Sinno H, Lacroix JP, Lee J, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:91-97.

- Cherng E, McClung AA, Rosenthal HM, et al. Wells' syndrome associated with parvovirus in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:762-764.

- Eren M, Açikalin M. A case report of Wells' syndrome in a celiac patient. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:172-174.

- Cruz MJ, Mota A, Baudrier T, et al. Recurrent Wells' syndrome associated with allergic asthma exacerbation. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:154-156.

- Van der Straaten S, Wojciechowski M, Salgado R, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells' syndrome in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:197-198.

A healthy 7-year-old boy presented with an enlarging hyperpigmented plaque on the anterior aspect of the lower left leg of 2 months' duration. His mother reported onset following a mosquito bite. Clotrimazole was used without improvement. His mother denied recent travel, similar lesions in close contacts, fever, asthma, and arthralgia. Physical examination revealed a 5.2 ×3-cm nonscaly, red-brown, ovoid, thin plaque with a slightly raised border.