User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Painless Mobile Nodule on the Shoulder

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metaplastic Synovial Cyst

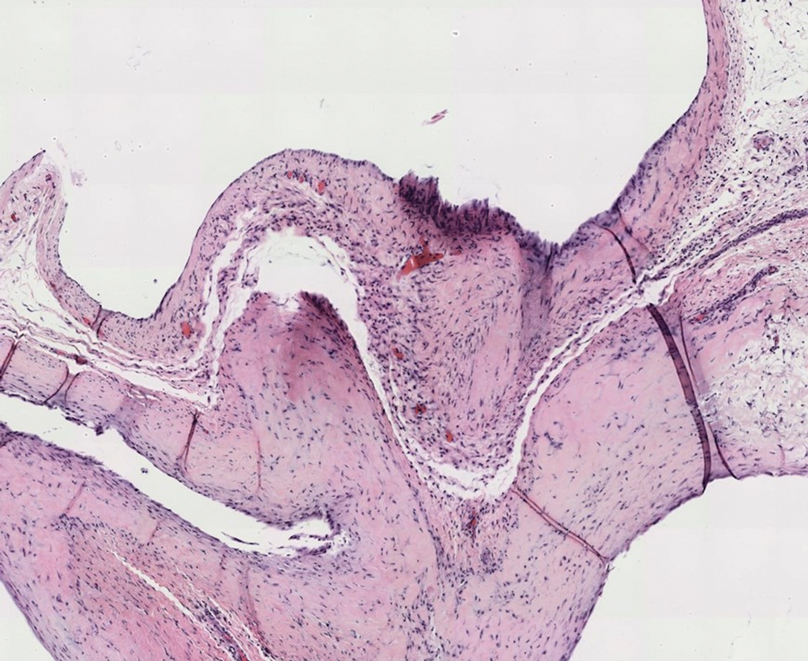

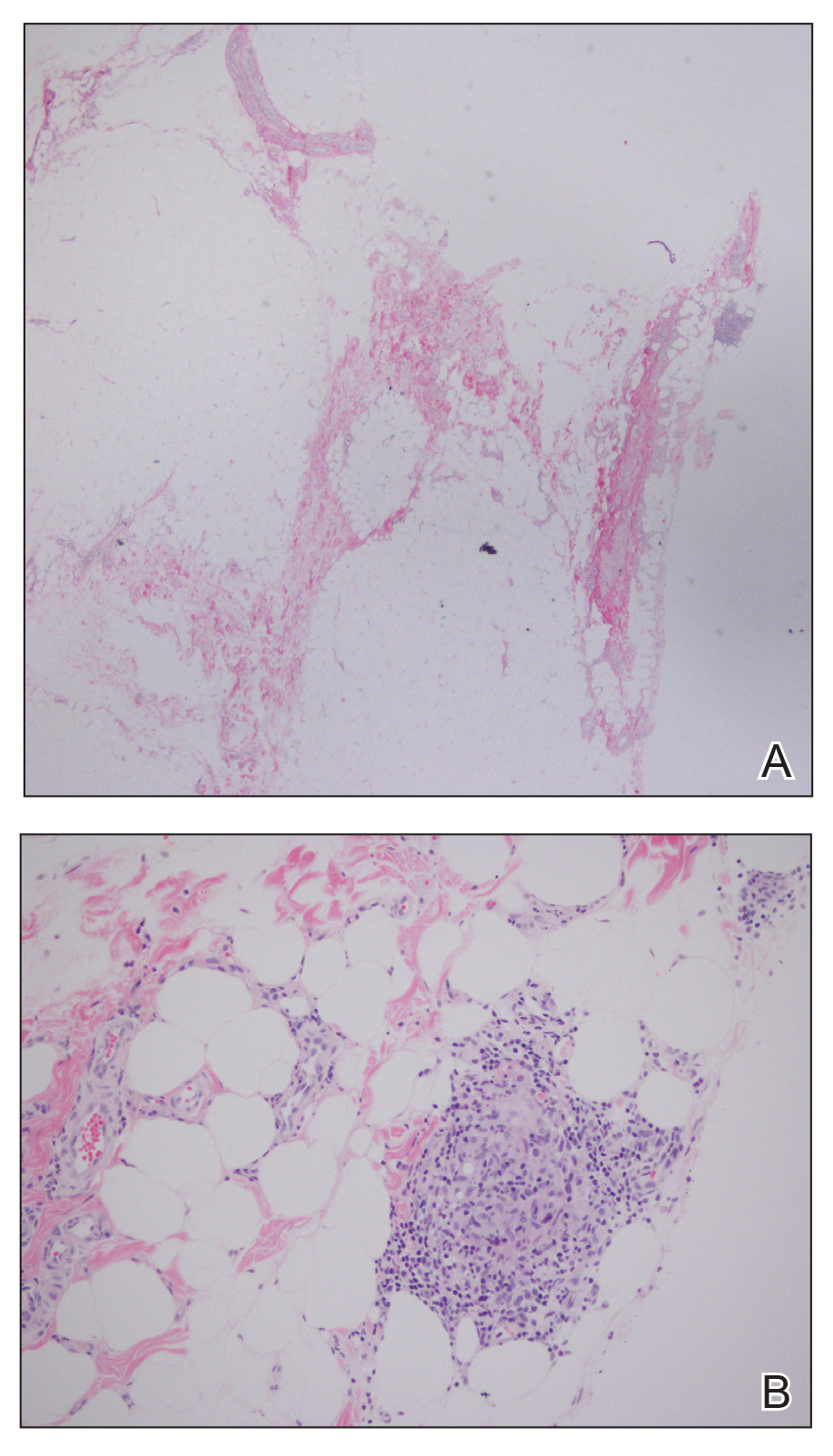

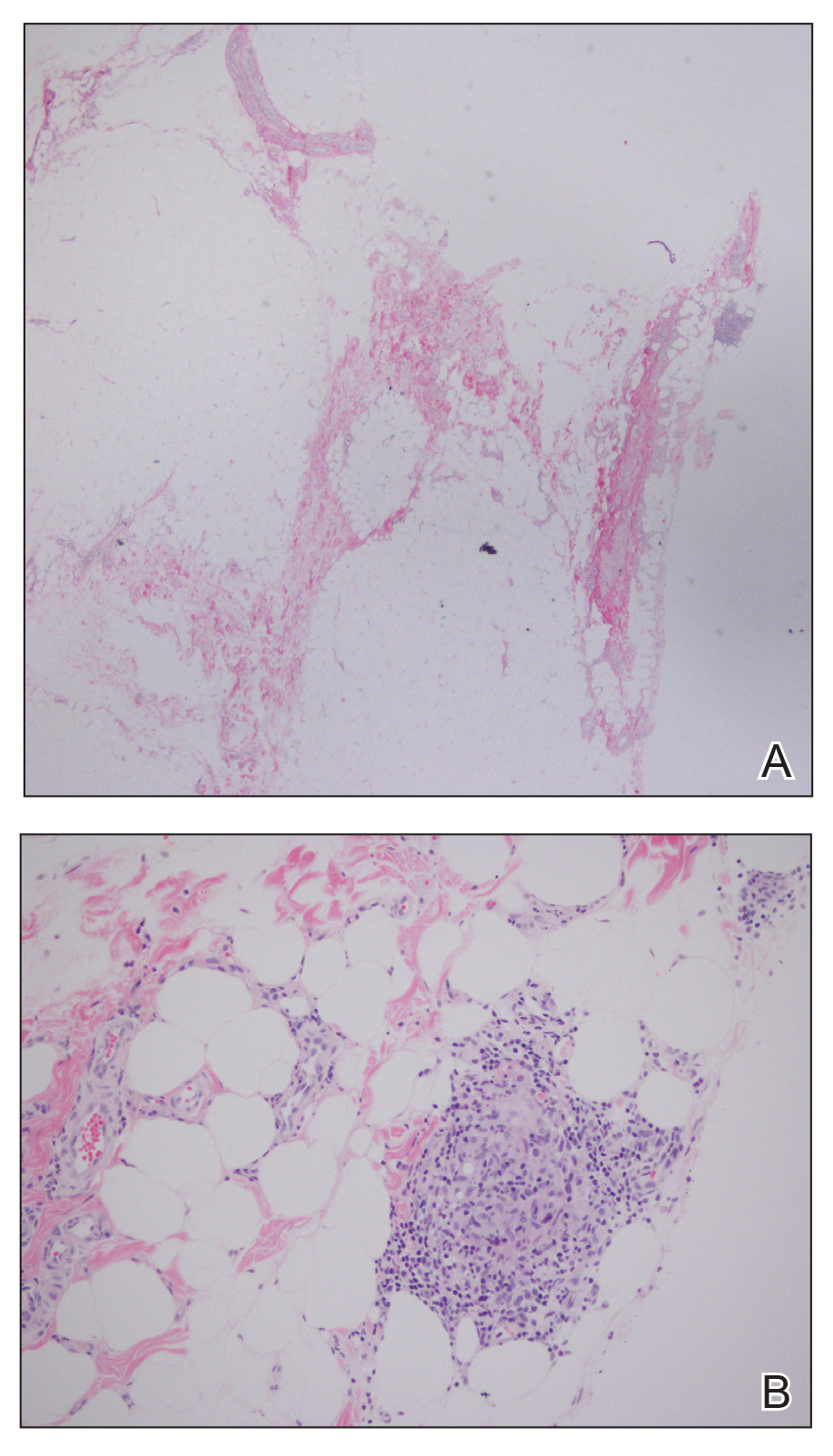

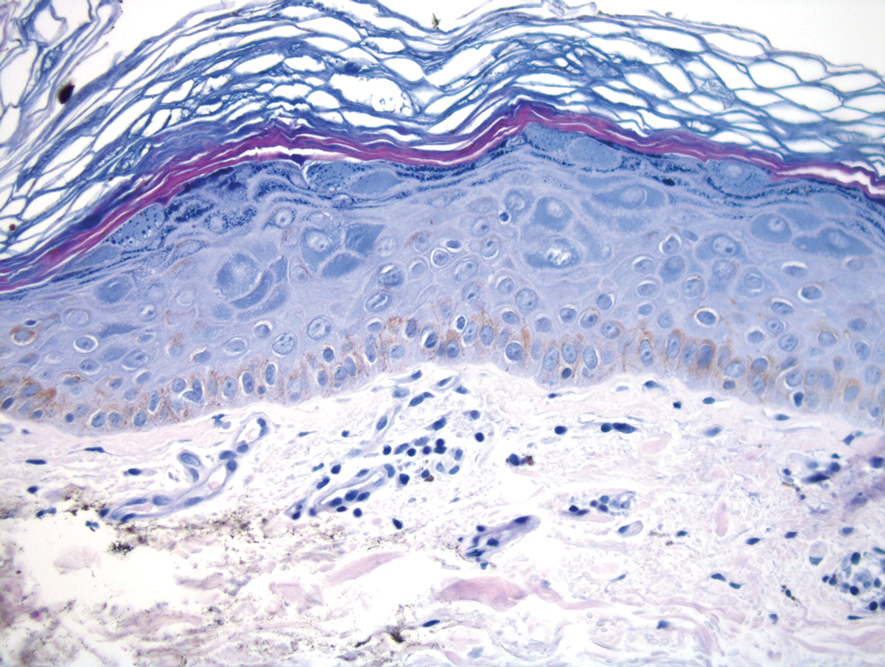

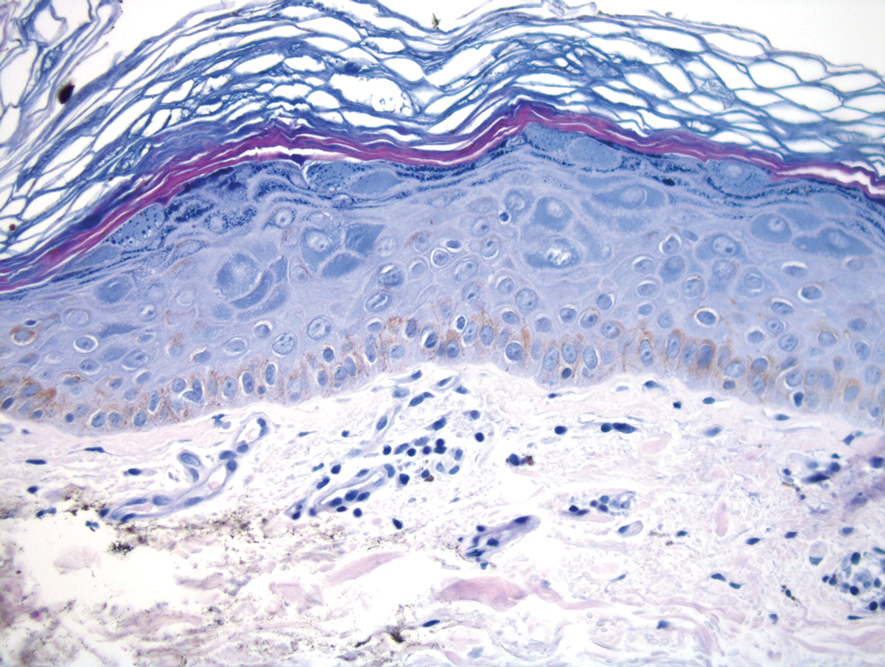

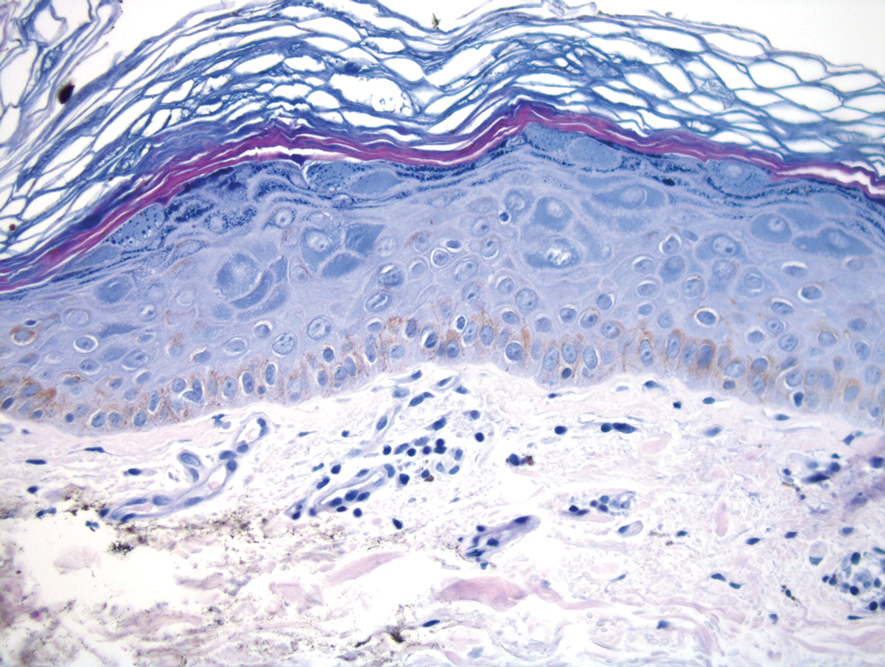

Gross examination of the excised nodule revealed a 2.5×1.2×1.0-cm, intact, gray-white, thin-walled, smooth-lined nodule filled with clear mucinouslike material. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated a dermal-based cystlike structure composed of a lining of connective tissue with hyalinized material and fibrin as well as spindle and epithelioid cells with a mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure). These histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst (CMSC).

Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst, also known as synovial metaplasia of the skin, is an uncommon benign cystic lesion that was first reported by Gonzalez et al1 in 1987. Histologically, CMSC lacks an epithelial lining and therefore is not a true cyst but rather a pseudocyst.2 Clinically, the lesion typically presents as a solitary subcutaneous nodule that may be tender or painless. In a literature review of CMSC cases performed by Fukuyama et al,3 distribution of reported cases according to body site varied; however, limbs were found to be the most commonly involved area. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the term cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst revealed at least 37 cases reported in the English-language literature,3-9 including our present case. The pathogenesis remains uncertain; however, a majority of previously reported cases of CMSC characteristically have been associated with a pre-existing lesion, with most presentations developing at surgical scar sites secondary to operation or trauma.5 Relative tissue fragility secondary to rheumatoid arthritis10 and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome9,11,12 has been linked to CMSC in some documented reports, while a minority of cases report no antecedent events triggering formation of the lesion.13-15

As evidenced by our patient, CMSC clinically mimics several other benign entities; histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Although nodular hidradenoma also may clinically present as a solitary firm intradermal nodule, microscopy reveals a dermal-based lobulated tumor containing cystic spaces and solid areas composed of basophilic polyhedral cells and round glycogen-filled clear cells.16 Epidermoid cysts are differentiated from CMSC by the presence of a cyst wall lining composed of stratified squamous epithelium and associated laminated keratin within the lumen,17 which corresponds to its pearly white appearance on gross examination. Cutaneous ciliated cysts predominantly occur on the lower extremities of young women and are lined by simple cuboidal or columnar ciliated cells that resemble müllerian epithelium.18 Similar to CMSC, ganglion cysts are pseudocysts that lack a true epithelial lining but differ in appearance due to their mucin-filled synovial-lined sac.19 Additionally, ganglion cysts most often occur on the dorsal and volar aspects of the wrist.

Excisional biopsy is indicated as the preferred treatment of CMSC, given the lesion's benign behavior and low recurrence rate.6 Our case highlights this rare entity and reinforces its inclusion in the differential diagnosis of subcutaneous mobile nodules, especially in the setting of prior tissue injury secondary to trauma, surgical procedures, or conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Unlike most previously reported cases, our patient reported no preceding tissue injury associated with formation of the lesion, and she was largely asymptomatic on presentation. Considering the limited number of CMSC cases demonstrated in the literature, it is important to continue reporting new cases to better understand characteristics and presentations of this uncommon lesion.

- Gonzalez JG, Ghiselli RW, Santa Cruz DJ. Synovial metaplasia of the skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:343-350.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. Cutaneous cysts. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2020:1680-1697.

- Fukuyama M, Sato Y, Hayakawa J, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst: case report and literature review from the dermatological point of view. Keio J Med. 2016;66:9-13.

- Karaytug K, Kapicioglu M, Can N, et al. Unprecedented recurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome by metaplastic synovial cyst in the carpal tunnel. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2019;53:230-232.

- Martelli SJ, Silveira FM, Carvalho PH, et al. Asymptomatic subcutaneous swelling of lower face. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2019;128:101-105.

- Majdi M, Saffar H, Ghanadan A. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst: a case report. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:423-426.

- Ramachandra S, Rao L, Al-Kindi M. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016;16:E117-E118.

- Heidarian A, Xie Q, Banihashemi A. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst presenting as an axillary mass after modified mastectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146:S2.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Barja-Lopez JM. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:729-733.

- Choonhakarn C, Tang S. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. J Dermatol. 2003;30:480-484.

- Guala A, Viglio S, Ottinetti A, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: report of a second case. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:59-61.

- Nieto S, Buezo GF, Jones-Caballero M, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in an Ehlers-Danlos patient. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:407-410.

- Goiriz R, Rios-Buceta L, Alonso-Perez A, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:180-181.

- Kim BC, Choi WJ, Park EJ, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst of the first metatarsal head area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S165-S168.

- Yang HC, Tsai YJ, Hu SL, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst--a case report and review of literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2003;21:275-279.

- Kataria SP, Singh G, Batra A, et al. Nodular hidradenoma: a series of five cases in male subjects and review of literature. Adv Cytol Pathol. 2018;3:46-47.

- Mohamed Haflah N, Mohd Kassim A, Hassan Shukur M. Giant epidermoid cyst of the thigh. Malays Orthop J. 2011;5:17-19.

- Torisu-Itakura H, Itakura E, Horiuchi R, et al. Cutaneous ciliated cyst on the leg of a woman of menopausal age. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:323-324.

- Fullen DR. Cysts and sinuses. In: Busam K, ed. Dermatopathology. Saunders; 2010:300-330.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metaplastic Synovial Cyst

Gross examination of the excised nodule revealed a 2.5×1.2×1.0-cm, intact, gray-white, thin-walled, smooth-lined nodule filled with clear mucinouslike material. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated a dermal-based cystlike structure composed of a lining of connective tissue with hyalinized material and fibrin as well as spindle and epithelioid cells with a mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure). These histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst (CMSC).

Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst, also known as synovial metaplasia of the skin, is an uncommon benign cystic lesion that was first reported by Gonzalez et al1 in 1987. Histologically, CMSC lacks an epithelial lining and therefore is not a true cyst but rather a pseudocyst.2 Clinically, the lesion typically presents as a solitary subcutaneous nodule that may be tender or painless. In a literature review of CMSC cases performed by Fukuyama et al,3 distribution of reported cases according to body site varied; however, limbs were found to be the most commonly involved area. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the term cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst revealed at least 37 cases reported in the English-language literature,3-9 including our present case. The pathogenesis remains uncertain; however, a majority of previously reported cases of CMSC characteristically have been associated with a pre-existing lesion, with most presentations developing at surgical scar sites secondary to operation or trauma.5 Relative tissue fragility secondary to rheumatoid arthritis10 and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome9,11,12 has been linked to CMSC in some documented reports, while a minority of cases report no antecedent events triggering formation of the lesion.13-15

As evidenced by our patient, CMSC clinically mimics several other benign entities; histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Although nodular hidradenoma also may clinically present as a solitary firm intradermal nodule, microscopy reveals a dermal-based lobulated tumor containing cystic spaces and solid areas composed of basophilic polyhedral cells and round glycogen-filled clear cells.16 Epidermoid cysts are differentiated from CMSC by the presence of a cyst wall lining composed of stratified squamous epithelium and associated laminated keratin within the lumen,17 which corresponds to its pearly white appearance on gross examination. Cutaneous ciliated cysts predominantly occur on the lower extremities of young women and are lined by simple cuboidal or columnar ciliated cells that resemble müllerian epithelium.18 Similar to CMSC, ganglion cysts are pseudocysts that lack a true epithelial lining but differ in appearance due to their mucin-filled synovial-lined sac.19 Additionally, ganglion cysts most often occur on the dorsal and volar aspects of the wrist.

Excisional biopsy is indicated as the preferred treatment of CMSC, given the lesion's benign behavior and low recurrence rate.6 Our case highlights this rare entity and reinforces its inclusion in the differential diagnosis of subcutaneous mobile nodules, especially in the setting of prior tissue injury secondary to trauma, surgical procedures, or conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Unlike most previously reported cases, our patient reported no preceding tissue injury associated with formation of the lesion, and she was largely asymptomatic on presentation. Considering the limited number of CMSC cases demonstrated in the literature, it is important to continue reporting new cases to better understand characteristics and presentations of this uncommon lesion.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metaplastic Synovial Cyst

Gross examination of the excised nodule revealed a 2.5×1.2×1.0-cm, intact, gray-white, thin-walled, smooth-lined nodule filled with clear mucinouslike material. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated a dermal-based cystlike structure composed of a lining of connective tissue with hyalinized material and fibrin as well as spindle and epithelioid cells with a mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure). These histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst (CMSC).

Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst, also known as synovial metaplasia of the skin, is an uncommon benign cystic lesion that was first reported by Gonzalez et al1 in 1987. Histologically, CMSC lacks an epithelial lining and therefore is not a true cyst but rather a pseudocyst.2 Clinically, the lesion typically presents as a solitary subcutaneous nodule that may be tender or painless. In a literature review of CMSC cases performed by Fukuyama et al,3 distribution of reported cases according to body site varied; however, limbs were found to be the most commonly involved area. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the term cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst revealed at least 37 cases reported in the English-language literature,3-9 including our present case. The pathogenesis remains uncertain; however, a majority of previously reported cases of CMSC characteristically have been associated with a pre-existing lesion, with most presentations developing at surgical scar sites secondary to operation or trauma.5 Relative tissue fragility secondary to rheumatoid arthritis10 and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome9,11,12 has been linked to CMSC in some documented reports, while a minority of cases report no antecedent events triggering formation of the lesion.13-15

As evidenced by our patient, CMSC clinically mimics several other benign entities; histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Although nodular hidradenoma also may clinically present as a solitary firm intradermal nodule, microscopy reveals a dermal-based lobulated tumor containing cystic spaces and solid areas composed of basophilic polyhedral cells and round glycogen-filled clear cells.16 Epidermoid cysts are differentiated from CMSC by the presence of a cyst wall lining composed of stratified squamous epithelium and associated laminated keratin within the lumen,17 which corresponds to its pearly white appearance on gross examination. Cutaneous ciliated cysts predominantly occur on the lower extremities of young women and are lined by simple cuboidal or columnar ciliated cells that resemble müllerian epithelium.18 Similar to CMSC, ganglion cysts are pseudocysts that lack a true epithelial lining but differ in appearance due to their mucin-filled synovial-lined sac.19 Additionally, ganglion cysts most often occur on the dorsal and volar aspects of the wrist.

Excisional biopsy is indicated as the preferred treatment of CMSC, given the lesion's benign behavior and low recurrence rate.6 Our case highlights this rare entity and reinforces its inclusion in the differential diagnosis of subcutaneous mobile nodules, especially in the setting of prior tissue injury secondary to trauma, surgical procedures, or conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Unlike most previously reported cases, our patient reported no preceding tissue injury associated with formation of the lesion, and she was largely asymptomatic on presentation. Considering the limited number of CMSC cases demonstrated in the literature, it is important to continue reporting new cases to better understand characteristics and presentations of this uncommon lesion.

- Gonzalez JG, Ghiselli RW, Santa Cruz DJ. Synovial metaplasia of the skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:343-350.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. Cutaneous cysts. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2020:1680-1697.

- Fukuyama M, Sato Y, Hayakawa J, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst: case report and literature review from the dermatological point of view. Keio J Med. 2016;66:9-13.

- Karaytug K, Kapicioglu M, Can N, et al. Unprecedented recurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome by metaplastic synovial cyst in the carpal tunnel. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2019;53:230-232.

- Martelli SJ, Silveira FM, Carvalho PH, et al. Asymptomatic subcutaneous swelling of lower face. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2019;128:101-105.

- Majdi M, Saffar H, Ghanadan A. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst: a case report. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:423-426.

- Ramachandra S, Rao L, Al-Kindi M. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016;16:E117-E118.

- Heidarian A, Xie Q, Banihashemi A. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst presenting as an axillary mass after modified mastectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146:S2.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Barja-Lopez JM. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:729-733.

- Choonhakarn C, Tang S. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. J Dermatol. 2003;30:480-484.

- Guala A, Viglio S, Ottinetti A, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: report of a second case. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:59-61.

- Nieto S, Buezo GF, Jones-Caballero M, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in an Ehlers-Danlos patient. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:407-410.

- Goiriz R, Rios-Buceta L, Alonso-Perez A, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:180-181.

- Kim BC, Choi WJ, Park EJ, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst of the first metatarsal head area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S165-S168.

- Yang HC, Tsai YJ, Hu SL, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst--a case report and review of literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2003;21:275-279.

- Kataria SP, Singh G, Batra A, et al. Nodular hidradenoma: a series of five cases in male subjects and review of literature. Adv Cytol Pathol. 2018;3:46-47.

- Mohamed Haflah N, Mohd Kassim A, Hassan Shukur M. Giant epidermoid cyst of the thigh. Malays Orthop J. 2011;5:17-19.

- Torisu-Itakura H, Itakura E, Horiuchi R, et al. Cutaneous ciliated cyst on the leg of a woman of menopausal age. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:323-324.

- Fullen DR. Cysts and sinuses. In: Busam K, ed. Dermatopathology. Saunders; 2010:300-330.

- Gonzalez JG, Ghiselli RW, Santa Cruz DJ. Synovial metaplasia of the skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:343-350.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. Cutaneous cysts. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2020:1680-1697.

- Fukuyama M, Sato Y, Hayakawa J, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst: case report and literature review from the dermatological point of view. Keio J Med. 2016;66:9-13.

- Karaytug K, Kapicioglu M, Can N, et al. Unprecedented recurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome by metaplastic synovial cyst in the carpal tunnel. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2019;53:230-232.

- Martelli SJ, Silveira FM, Carvalho PH, et al. Asymptomatic subcutaneous swelling of lower face. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2019;128:101-105.

- Majdi M, Saffar H, Ghanadan A. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst: a case report. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:423-426.

- Ramachandra S, Rao L, Al-Kindi M. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016;16:E117-E118.

- Heidarian A, Xie Q, Banihashemi A. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst presenting as an axillary mass after modified mastectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146:S2.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Barja-Lopez JM. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:729-733.

- Choonhakarn C, Tang S. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. J Dermatol. 2003;30:480-484.

- Guala A, Viglio S, Ottinetti A, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: report of a second case. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:59-61.

- Nieto S, Buezo GF, Jones-Caballero M, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst in an Ehlers-Danlos patient. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:407-410.

- Goiriz R, Rios-Buceta L, Alonso-Perez A, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:180-181.

- Kim BC, Choi WJ, Park EJ, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst of the first metatarsal head area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S165-S168.

- Yang HC, Tsai YJ, Hu SL, et al. Cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst--a case report and review of literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2003;21:275-279.

- Kataria SP, Singh G, Batra A, et al. Nodular hidradenoma: a series of five cases in male subjects and review of literature. Adv Cytol Pathol. 2018;3:46-47.

- Mohamed Haflah N, Mohd Kassim A, Hassan Shukur M. Giant epidermoid cyst of the thigh. Malays Orthop J. 2011;5:17-19.

- Torisu-Itakura H, Itakura E, Horiuchi R, et al. Cutaneous ciliated cyst on the leg of a woman of menopausal age. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:323-324.

- Fullen DR. Cysts and sinuses. In: Busam K, ed. Dermatopathology. Saunders; 2010:300-330.

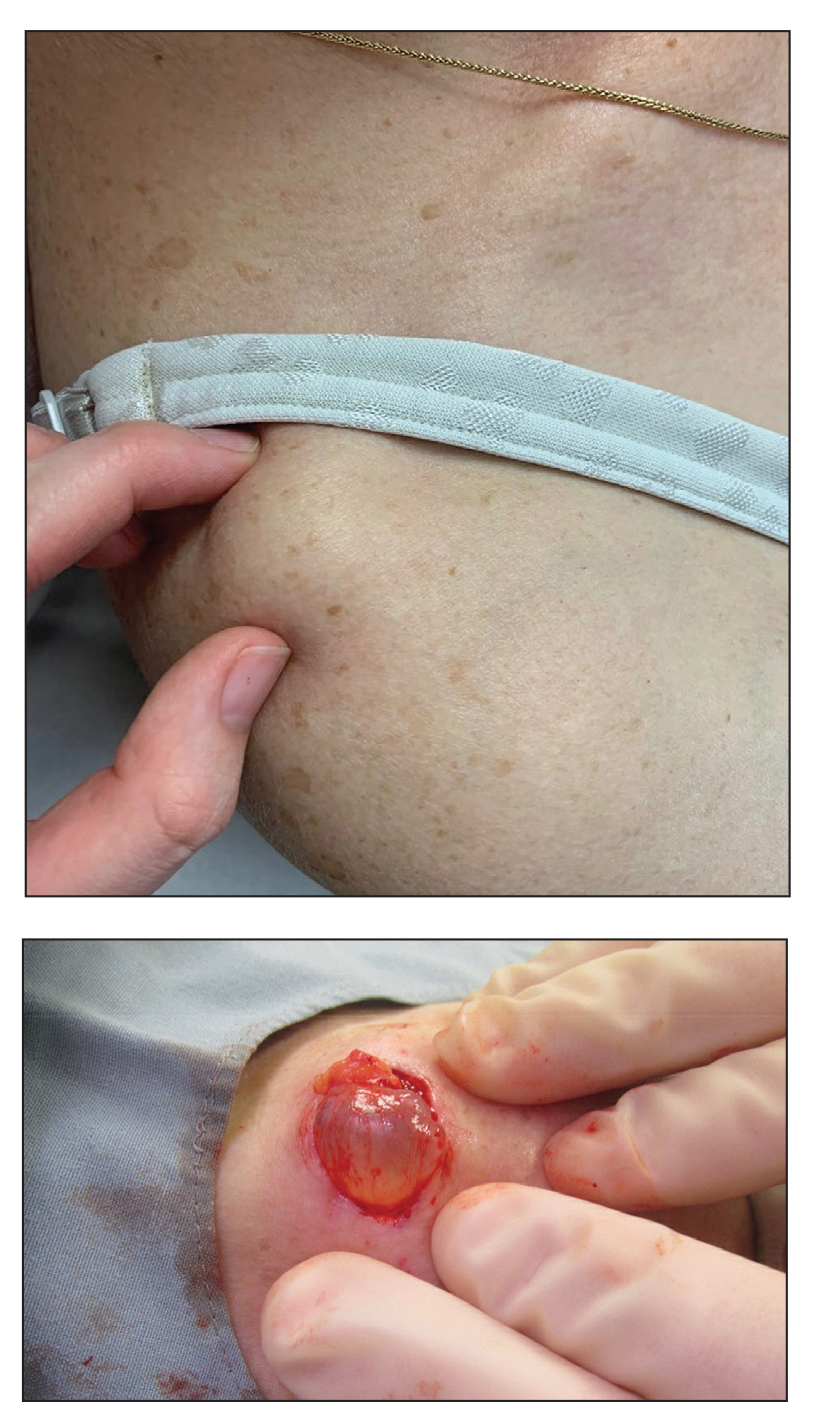

A 70-year-old woman presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with an acute-onset lesion on the right shoulder. She first noticed a “cyst” developing in the area approximately 3 weeks prior but noted that it may have been present longer. The lesion was bothersome when her undergarments rubbed against it, but she otherwise denied pain, increase in size, or drainage from the site. Her medical history was remarkable for a proliferating trichilemmal tumor on the right parietal scalp treated with Mohs surgery approximately 13 years prior to presentation. She had no personal or family history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed a 2.5-cm, mobile, nontender, flesh-colored subcutaneous nodule on the right shoulder (top); no ulceration, bleeding, or drainage was present. The surrounding skin demonstrated no clinical changes. The patient was scheduled for outpatient surgical excision of the nodule, which initially was suspected to be a lipoma. During the excision, a translucent cystlike nodule (bottom) was gently dissected and sent for histopathologic examination.

Sudden Cardiac Death in a Young Patient With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

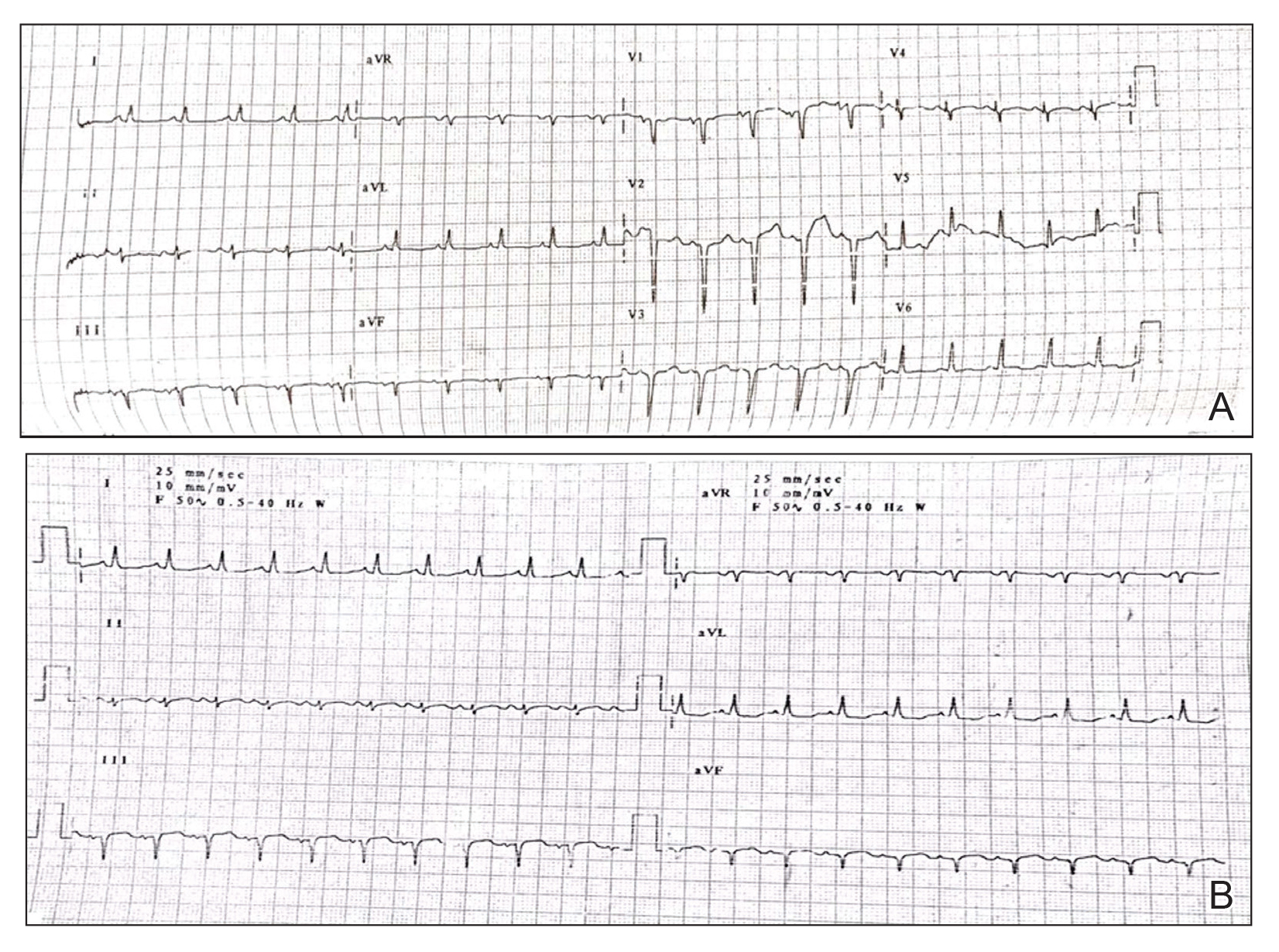

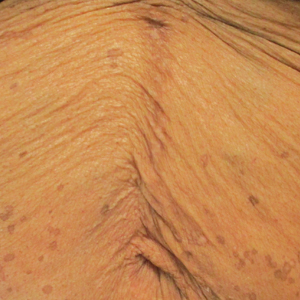

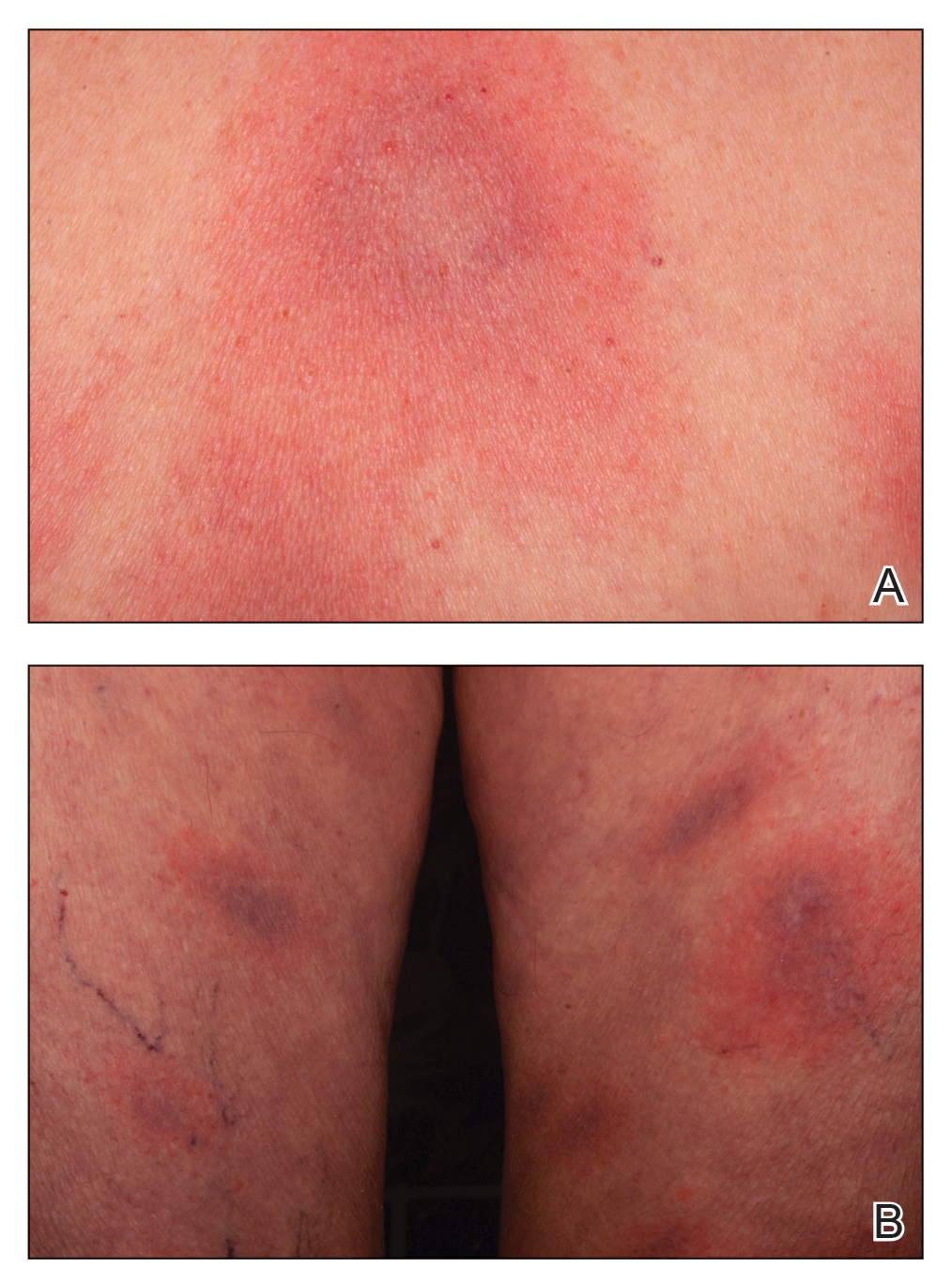

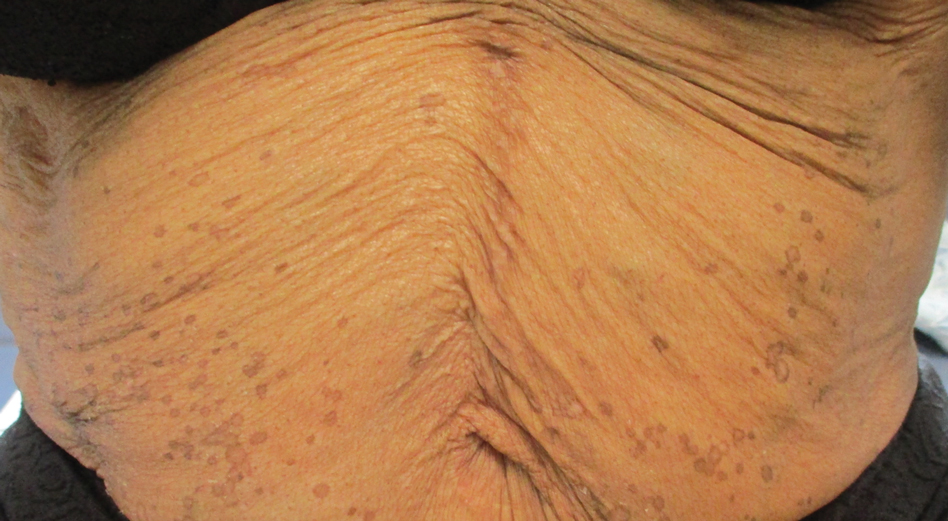

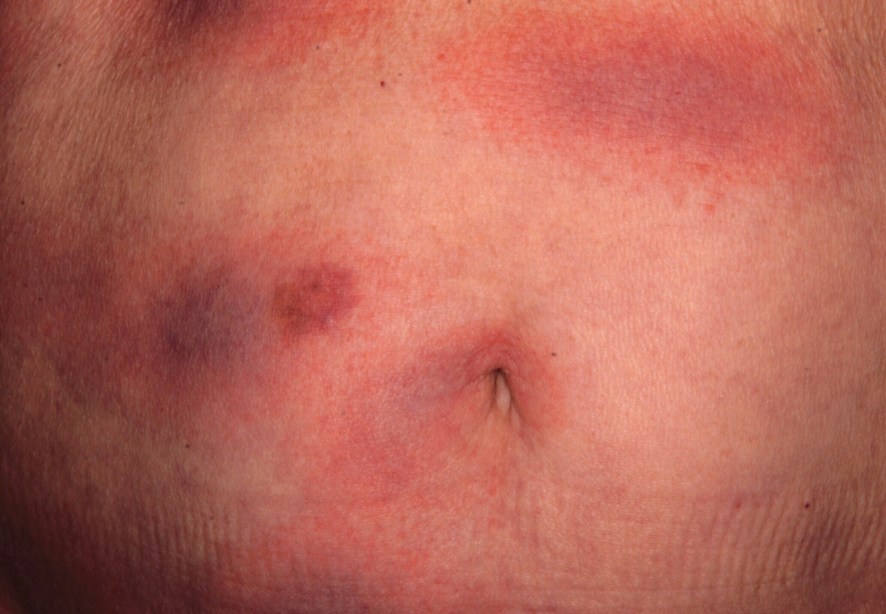

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

Practice Points

- Low-grade chronic inflammation in patients with psoriasis can lead to vascular inflammation, which can further lead to the development of major adverse cardiovascular events (CVEs) and arrhythmia.

- The need for a multidisciplinary approach and close monitoring of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis to prevent a CVE is vital.

- Baseline electrocardiogram and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease also should be performed in young patients with severe or unstable psoriasis.

Crusted Scabies Presenting as White Superficial Onychomycosislike Lesions

To the Editor:

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

To the Editor:

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

To the Editor:

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

Practice Points

- Crusted scabies is asymptomatic; therefore, any white lesion at the surface of the nail should be scraped and examined with potassium hydroxide.

- Immunosuppressed patients are at risk for infection.

Recurrent Painful Nodules Following Synthol Injection to Enhance Bicep Volume

To the Editor:

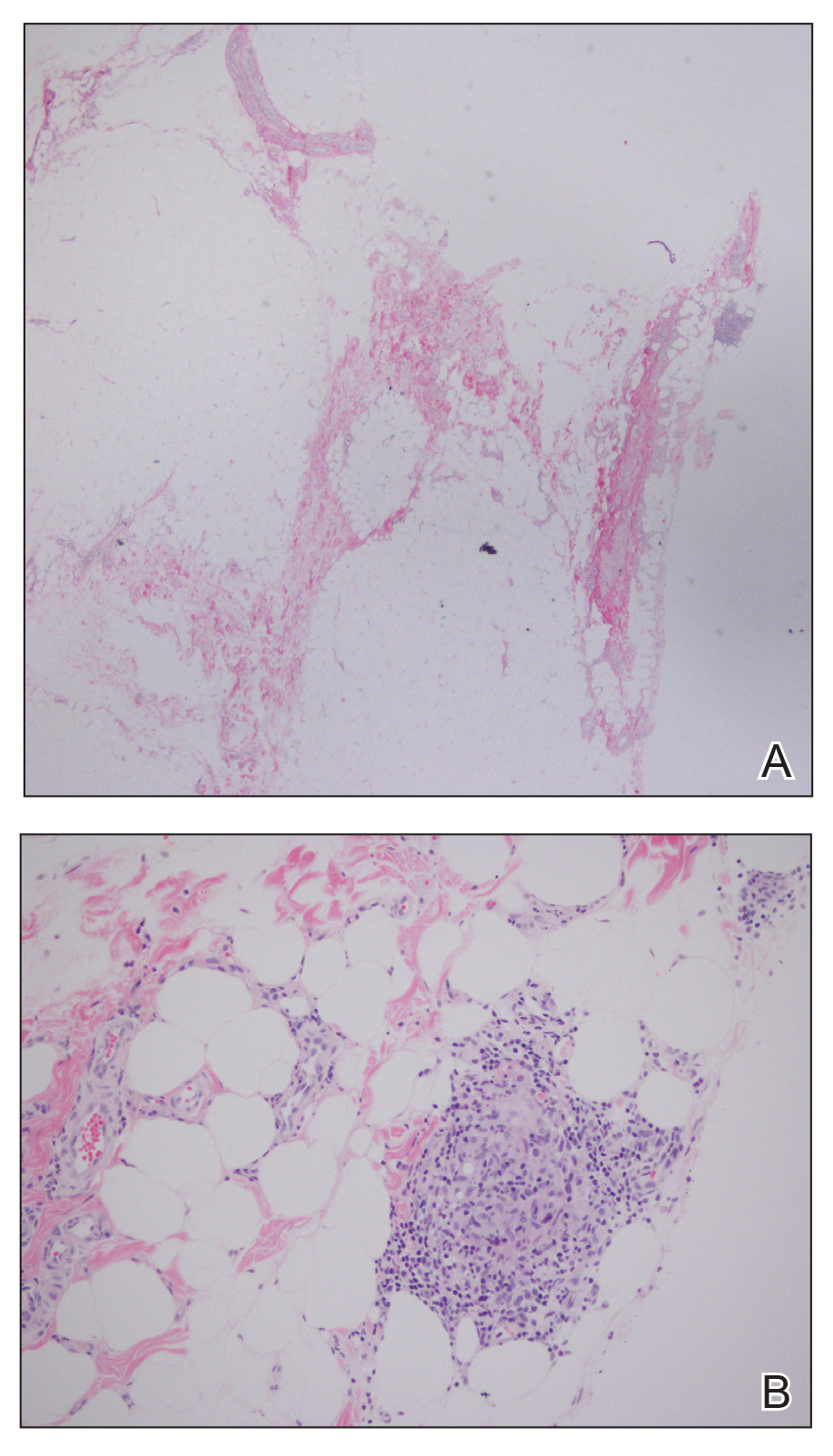

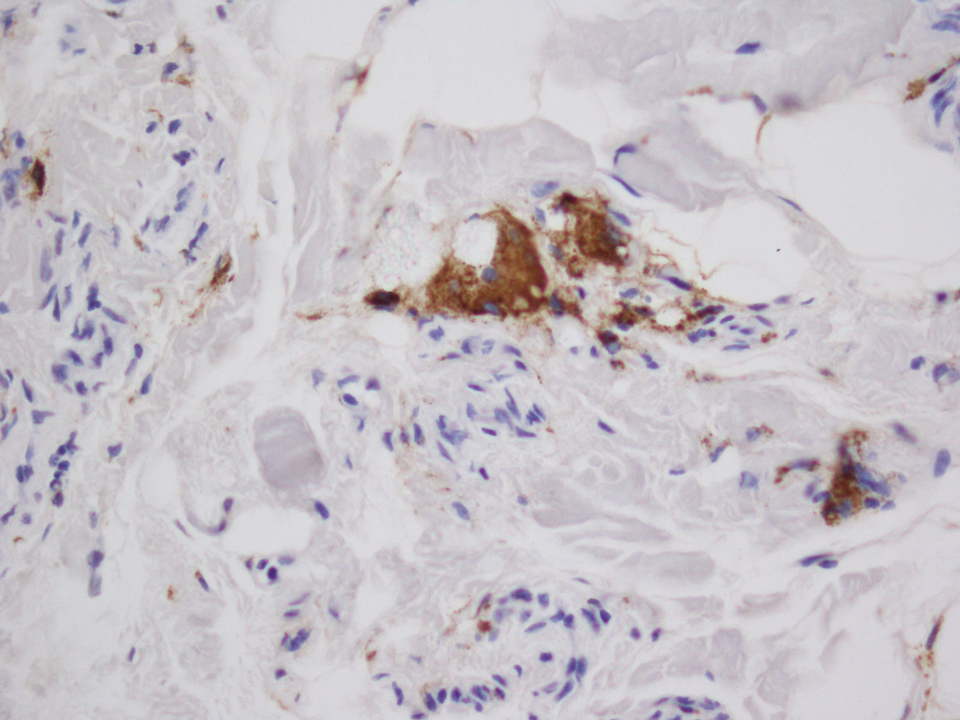

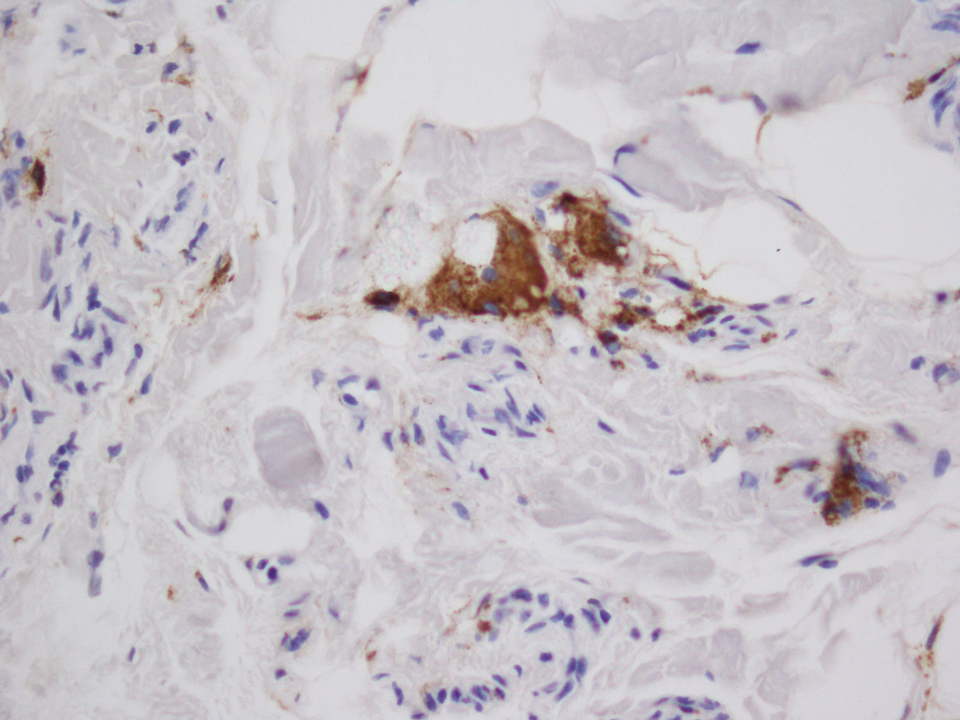

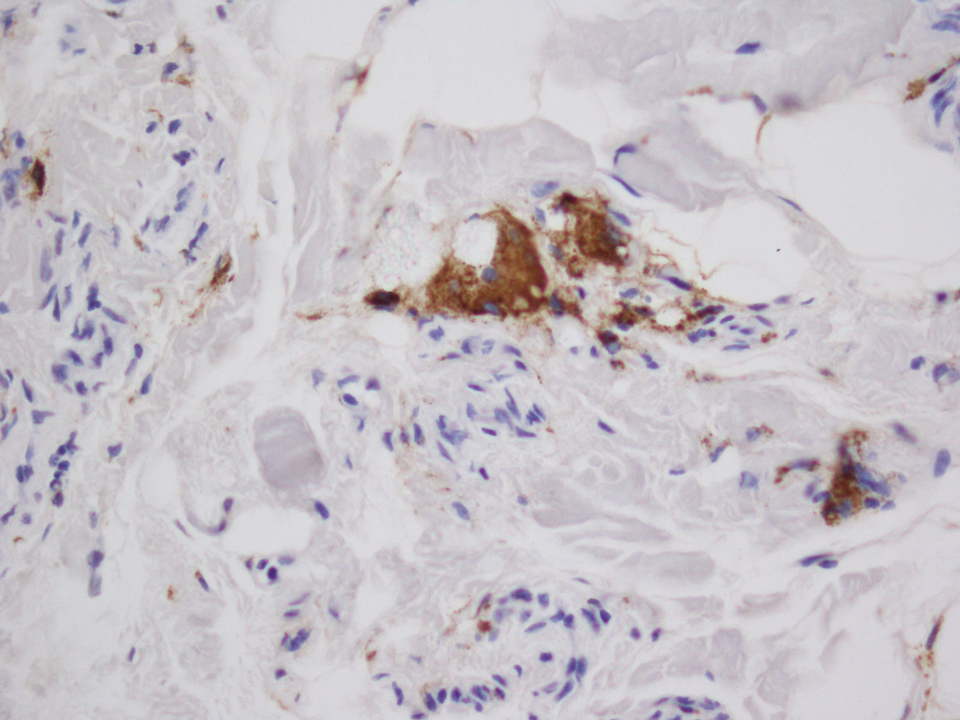

A 28-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with red, tender, swollen nodules on the left arm of 5 days’ duration, which had been a recurrent issue involving both arms. He also experienced intermittent fatigue and mild myalgia but denied associated fevers or chills. Oral clindamycin prescribed by a local emergency department provided some improvement. Upon further questioning, the patient admitted to injecting an unknown substance into the muscles 10 years prior for the purpose of enhancing their volume and appearance. Physical examination revealed large bilateral biceps with firm, mobile, nontender, subcutaneous nodules and mild erythema on the inner aspects of the arms. An incisional biopsy of a left arm nodule was performed with tissue culture (Figure 1). Microscopic evaluation revealed mild dermal sclerosis with edema and sclerosis of fat septae (Figure 2A). The fat lobules contained granulomas with surrounding lymphocytes and clear holes noted within the histiocytic giant cells, indicating a likely foreign substance (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining of the histiocytes with CD68 highlighted the clear vacuoles (Figure 3). Polarization examination, Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacilli staining were negative. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures and staining also were negative. The histologic findings of septal and lobular panniculitis with sclerosis and granulomatous inflammation in the clinical setting were consistent with a foreign body reaction secondary to synthol injection.

The willingness of athletes in competitive sports to undergo procedures or utilize substances for a competitive advantage despite both immediate and long-term consequences is well documented.1,2 In bodybuilding, use of anabolic steroids and intramuscular oil injections has been documented.3 The use of site enhancements in the form of “fillers” such as petroleum jelly and paraffin have been used for more than 100 years.4 The use of oil for volumetric site enhancement began in the 1960s in Italy with formebolone and evolved to the use of synthol in the 1990s.5 Synthol is a substance composed of 85% oil in the form of medium-chain triglycerides, 7.5% alcohol, and 7.5% lidocaine.6 The presumed mechanism of action of injected oils consists of an initial inflammatory response followed by fibrosis and chronic macrophagocytosis, ultimately leading to expanded volume in the subcutaneous tissue.7 These procedures are purely aesthetic with no increase in muscle strength or performance.

There are few cases in the literature of side effects from intramuscular synthol injections. In one report, a 29-year-old man presented with painful muscle fibrosis requiring open surgical excision of massively fibrotic bicep tissue.8 Another report documented a 45-year-old man who presented with spontaneous ulcerations on the biceps that initially were treated with antibiotics and compression therapy but eventually required surgical intervention and skin grafting.9 Complications have been more frequently reported from injections of other oils such as paraffin and sesame.10,11 Given the similar underlying mechanisms of action, injected oils share the local side effects of inflammation, infection, chronic wounds, and ulceration,9,10 as well as a systemic risk for embolization leading to pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarction, and stroke.6 Although no standard of care exists for the management of complications arising from intramuscular oil injections, treatments that have been employed include antibiotics, corticosteroids, wound care, and compression therapy; definitive treatment typically is surgical excision.6,8,9,11,12 Psychiatric evaluation also should be considered to evaluate for the possibility of body dysmorphic disorder and other associated psychiatric conditions.11

Pressure for a particular aesthetic appearance, both within and outside the world of competitive sports, has driven individuals to various methods of muscular enhancement. Volumetric site enhancements have become increasingly popular, in part due to the perceived lack of systemic side effects, such as those associated with anabolic steroids.8 However, most users are unaware of the notable short-term and long-term risks associated with intramuscular oil injections. Synthol is widely available on the Internet and easily can be purchased and injected by anyone.13 Medical providers should be aware of the possibility of aesthetic site enhancement use in their patients and be able to recognize and intervene in these cases to prevent chronic damage to muscle tissue and accompanying complications. Despite extensive commercialization of these products, few reports in the medical literature exist detailing the side effects of intramuscular oil injections, which may be contributing to the trivialization of these procedures by the general public.12

- Baron DA, Martin DM, Abol Magd S. Doping in sports and its spread to at-risk populations: an international review. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:118-123.

- Holt RIG, Erotokritou-Mulligan I, Sönksen PH. The history of doping and growth hormone abuse in sport. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2009;19:320-326.

- Figueiredo VC, Pedroso da Silva PR. Cosmetic doping—when anabolic-androgenic steroids are not enough. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49:1163-1167.

- Glicenstein J. The first “fillers,” vaseline and paraffin. from miracle to disaster [in French]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007;52:157-161.

- Evans NA. Gym and tonic: a profile of 100 male steroid users. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31:54-58.

- Pupka A, Sikora J, Mauricz J, et al. The usage of synthol in the body building [in Polish]. Polim Med. 2009;39:63-65.

- Di Benedetto G, Pierangeli M, Scalise A, et al. Paraffin oil injection in the body: an obsolete and destructive procedure. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49:391-396.

- Ghandourah S, Hofer MJ, Kiessling A, et al. Painful muscle fibrosis following synthol injections in a bodybuilder: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:248.

- Ikander P, Nielsen AM, Sørensen JA. Injection of synthol in a bodybuilder can cause chronic wounds and ulceration [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V12140642.

- Henriksen TF, Løvenwald JB, Matzen SH. Paraffin oil injection in bodybuilders calls for preventive action [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:219-220.

- Darsow U, Bruckbauer H, Worret WI, et al. Subcutaneous oleomas induced by self-injection of sesame seed oil for muscle augmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):292-294.

- Banke IJ, Prodinger PM, Waldt S, et al. Irreversible muscle damage in bodybuilding due to long-term intramuscular oil injection. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:829-834.

- Hall M, Grogan S, Gough B. Bodybuilders’ accounts of synthol use: the construction of lay expertise online. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1939-1948.

To the Editor:

A 28-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with red, tender, swollen nodules on the left arm of 5 days’ duration, which had been a recurrent issue involving both arms. He also experienced intermittent fatigue and mild myalgia but denied associated fevers or chills. Oral clindamycin prescribed by a local emergency department provided some improvement. Upon further questioning, the patient admitted to injecting an unknown substance into the muscles 10 years prior for the purpose of enhancing their volume and appearance. Physical examination revealed large bilateral biceps with firm, mobile, nontender, subcutaneous nodules and mild erythema on the inner aspects of the arms. An incisional biopsy of a left arm nodule was performed with tissue culture (Figure 1). Microscopic evaluation revealed mild dermal sclerosis with edema and sclerosis of fat septae (Figure 2A). The fat lobules contained granulomas with surrounding lymphocytes and clear holes noted within the histiocytic giant cells, indicating a likely foreign substance (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining of the histiocytes with CD68 highlighted the clear vacuoles (Figure 3). Polarization examination, Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacilli staining were negative. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures and staining also were negative. The histologic findings of septal and lobular panniculitis with sclerosis and granulomatous inflammation in the clinical setting were consistent with a foreign body reaction secondary to synthol injection.

The willingness of athletes in competitive sports to undergo procedures or utilize substances for a competitive advantage despite both immediate and long-term consequences is well documented.1,2 In bodybuilding, use of anabolic steroids and intramuscular oil injections has been documented.3 The use of site enhancements in the form of “fillers” such as petroleum jelly and paraffin have been used for more than 100 years.4 The use of oil for volumetric site enhancement began in the 1960s in Italy with formebolone and evolved to the use of synthol in the 1990s.5 Synthol is a substance composed of 85% oil in the form of medium-chain triglycerides, 7.5% alcohol, and 7.5% lidocaine.6 The presumed mechanism of action of injected oils consists of an initial inflammatory response followed by fibrosis and chronic macrophagocytosis, ultimately leading to expanded volume in the subcutaneous tissue.7 These procedures are purely aesthetic with no increase in muscle strength or performance.

There are few cases in the literature of side effects from intramuscular synthol injections. In one report, a 29-year-old man presented with painful muscle fibrosis requiring open surgical excision of massively fibrotic bicep tissue.8 Another report documented a 45-year-old man who presented with spontaneous ulcerations on the biceps that initially were treated with antibiotics and compression therapy but eventually required surgical intervention and skin grafting.9 Complications have been more frequently reported from injections of other oils such as paraffin and sesame.10,11 Given the similar underlying mechanisms of action, injected oils share the local side effects of inflammation, infection, chronic wounds, and ulceration,9,10 as well as a systemic risk for embolization leading to pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarction, and stroke.6 Although no standard of care exists for the management of complications arising from intramuscular oil injections, treatments that have been employed include antibiotics, corticosteroids, wound care, and compression therapy; definitive treatment typically is surgical excision.6,8,9,11,12 Psychiatric evaluation also should be considered to evaluate for the possibility of body dysmorphic disorder and other associated psychiatric conditions.11

Pressure for a particular aesthetic appearance, both within and outside the world of competitive sports, has driven individuals to various methods of muscular enhancement. Volumetric site enhancements have become increasingly popular, in part due to the perceived lack of systemic side effects, such as those associated with anabolic steroids.8 However, most users are unaware of the notable short-term and long-term risks associated with intramuscular oil injections. Synthol is widely available on the Internet and easily can be purchased and injected by anyone.13 Medical providers should be aware of the possibility of aesthetic site enhancement use in their patients and be able to recognize and intervene in these cases to prevent chronic damage to muscle tissue and accompanying complications. Despite extensive commercialization of these products, few reports in the medical literature exist detailing the side effects of intramuscular oil injections, which may be contributing to the trivialization of these procedures by the general public.12

To the Editor:

A 28-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with red, tender, swollen nodules on the left arm of 5 days’ duration, which had been a recurrent issue involving both arms. He also experienced intermittent fatigue and mild myalgia but denied associated fevers or chills. Oral clindamycin prescribed by a local emergency department provided some improvement. Upon further questioning, the patient admitted to injecting an unknown substance into the muscles 10 years prior for the purpose of enhancing their volume and appearance. Physical examination revealed large bilateral biceps with firm, mobile, nontender, subcutaneous nodules and mild erythema on the inner aspects of the arms. An incisional biopsy of a left arm nodule was performed with tissue culture (Figure 1). Microscopic evaluation revealed mild dermal sclerosis with edema and sclerosis of fat septae (Figure 2A). The fat lobules contained granulomas with surrounding lymphocytes and clear holes noted within the histiocytic giant cells, indicating a likely foreign substance (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining of the histiocytes with CD68 highlighted the clear vacuoles (Figure 3). Polarization examination, Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacilli staining were negative. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures and staining also were negative. The histologic findings of septal and lobular panniculitis with sclerosis and granulomatous inflammation in the clinical setting were consistent with a foreign body reaction secondary to synthol injection.

The willingness of athletes in competitive sports to undergo procedures or utilize substances for a competitive advantage despite both immediate and long-term consequences is well documented.1,2 In bodybuilding, use of anabolic steroids and intramuscular oil injections has been documented.3 The use of site enhancements in the form of “fillers” such as petroleum jelly and paraffin have been used for more than 100 years.4 The use of oil for volumetric site enhancement began in the 1960s in Italy with formebolone and evolved to the use of synthol in the 1990s.5 Synthol is a substance composed of 85% oil in the form of medium-chain triglycerides, 7.5% alcohol, and 7.5% lidocaine.6 The presumed mechanism of action of injected oils consists of an initial inflammatory response followed by fibrosis and chronic macrophagocytosis, ultimately leading to expanded volume in the subcutaneous tissue.7 These procedures are purely aesthetic with no increase in muscle strength or performance.

There are few cases in the literature of side effects from intramuscular synthol injections. In one report, a 29-year-old man presented with painful muscle fibrosis requiring open surgical excision of massively fibrotic bicep tissue.8 Another report documented a 45-year-old man who presented with spontaneous ulcerations on the biceps that initially were treated with antibiotics and compression therapy but eventually required surgical intervention and skin grafting.9 Complications have been more frequently reported from injections of other oils such as paraffin and sesame.10,11 Given the similar underlying mechanisms of action, injected oils share the local side effects of inflammation, infection, chronic wounds, and ulceration,9,10 as well as a systemic risk for embolization leading to pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarction, and stroke.6 Although no standard of care exists for the management of complications arising from intramuscular oil injections, treatments that have been employed include antibiotics, corticosteroids, wound care, and compression therapy; definitive treatment typically is surgical excision.6,8,9,11,12 Psychiatric evaluation also should be considered to evaluate for the possibility of body dysmorphic disorder and other associated psychiatric conditions.11

Pressure for a particular aesthetic appearance, both within and outside the world of competitive sports, has driven individuals to various methods of muscular enhancement. Volumetric site enhancements have become increasingly popular, in part due to the perceived lack of systemic side effects, such as those associated with anabolic steroids.8 However, most users are unaware of the notable short-term and long-term risks associated with intramuscular oil injections. Synthol is widely available on the Internet and easily can be purchased and injected by anyone.13 Medical providers should be aware of the possibility of aesthetic site enhancement use in their patients and be able to recognize and intervene in these cases to prevent chronic damage to muscle tissue and accompanying complications. Despite extensive commercialization of these products, few reports in the medical literature exist detailing the side effects of intramuscular oil injections, which may be contributing to the trivialization of these procedures by the general public.12

- Baron DA, Martin DM, Abol Magd S. Doping in sports and its spread to at-risk populations: an international review. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:118-123.

- Holt RIG, Erotokritou-Mulligan I, Sönksen PH. The history of doping and growth hormone abuse in sport. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2009;19:320-326.

- Figueiredo VC, Pedroso da Silva PR. Cosmetic doping—when anabolic-androgenic steroids are not enough. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49:1163-1167.

- Glicenstein J. The first “fillers,” vaseline and paraffin. from miracle to disaster [in French]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007;52:157-161.

- Evans NA. Gym and tonic: a profile of 100 male steroid users. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31:54-58.

- Pupka A, Sikora J, Mauricz J, et al. The usage of synthol in the body building [in Polish]. Polim Med. 2009;39:63-65.

- Di Benedetto G, Pierangeli M, Scalise A, et al. Paraffin oil injection in the body: an obsolete and destructive procedure. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49:391-396.

- Ghandourah S, Hofer MJ, Kiessling A, et al. Painful muscle fibrosis following synthol injections in a bodybuilder: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:248.

- Ikander P, Nielsen AM, Sørensen JA. Injection of synthol in a bodybuilder can cause chronic wounds and ulceration [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V12140642.

- Henriksen TF, Løvenwald JB, Matzen SH. Paraffin oil injection in bodybuilders calls for preventive action [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:219-220.

- Darsow U, Bruckbauer H, Worret WI, et al. Subcutaneous oleomas induced by self-injection of sesame seed oil for muscle augmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):292-294.

- Banke IJ, Prodinger PM, Waldt S, et al. Irreversible muscle damage in bodybuilding due to long-term intramuscular oil injection. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:829-834.

- Hall M, Grogan S, Gough B. Bodybuilders’ accounts of synthol use: the construction of lay expertise online. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1939-1948.

- Baron DA, Martin DM, Abol Magd S. Doping in sports and its spread to at-risk populations: an international review. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:118-123.

- Holt RIG, Erotokritou-Mulligan I, Sönksen PH. The history of doping and growth hormone abuse in sport. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2009;19:320-326.

- Figueiredo VC, Pedroso da Silva PR. Cosmetic doping—when anabolic-androgenic steroids are not enough. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49:1163-1167.

- Glicenstein J. The first “fillers,” vaseline and paraffin. from miracle to disaster [in French]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007;52:157-161.

- Evans NA. Gym and tonic: a profile of 100 male steroid users. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31:54-58.

- Pupka A, Sikora J, Mauricz J, et al. The usage of synthol in the body building [in Polish]. Polim Med. 2009;39:63-65.

- Di Benedetto G, Pierangeli M, Scalise A, et al. Paraffin oil injection in the body: an obsolete and destructive procedure. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49:391-396.

- Ghandourah S, Hofer MJ, Kiessling A, et al. Painful muscle fibrosis following synthol injections in a bodybuilder: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:248.

- Ikander P, Nielsen AM, Sørensen JA. Injection of synthol in a bodybuilder can cause chronic wounds and ulceration [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V12140642.

- Henriksen TF, Løvenwald JB, Matzen SH. Paraffin oil injection in bodybuilders calls for preventive action [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:219-220.

- Darsow U, Bruckbauer H, Worret WI, et al. Subcutaneous oleomas induced by self-injection of sesame seed oil for muscle augmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):292-294.

- Banke IJ, Prodinger PM, Waldt S, et al. Irreversible muscle damage in bodybuilding due to long-term intramuscular oil injection. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:829-834.

- Hall M, Grogan S, Gough B. Bodybuilders’ accounts of synthol use: the construction of lay expertise online. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1939-1948.

Practice Points

- The use of injectable volumetric site enhancers in the form of oils to improve the aesthetic appearance of muscles has been prevalent for decades despite potentially serious adverse reactions.

- Complications from these procedures are underrecognized in the medical setting, perhaps owing to the trivialization of these procedures by the general public.

The Why, What, When, and How of Topical Antioxidants in Cosmeceuticals

Eruptive Annular Papules on the Trunk of an Organ Transplant Recipient

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination of our patient's biopsy specimen revealed mild acanthosis with prominent hypergranulosis and enlarged keratinocytes with blue-gray cytoplasm (Figure). A diagnosis of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) was rendered. The patient was treated with photodynamic therapy utilizing 5-aminolevulinic acid.

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis is characterized by susceptibility to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections via a defect in cellular immunity. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first described as an autosomal-recessive genodermatosis, but it can be acquired in immunosuppressed states with an atypical clinical appearance.1 There are few case reports in skin of color. Acquired EV appears in patients with acquired immunodeficiencies that are susceptible to EV-causing HPVs via a similar mechanism found in inherited EV.2 The most common HPV serotypes involved in EV are HPV-5 and HPV-8. The duration of immunosuppression has been found to be positively correlated with the risk for EV development, with the majority of patients developing lesions after 5 years of immunosuppression.3 There is an approximately 60% risk of malignant transformation of EV lesions into nonmelanoma skin cancer.2 This risk is believed to be lower in patients with darker skin.4

Preventative measures including sun protection and annual surveillance are crucial in EV patients given the high rate of malignant transformation in sun-exposed lesions.5 Treatment options for EV are anecdotal and have variable results, ranging from topicals including 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod to systemic medications including acitretin and interferon.3 Photodynamic therapy can be used for extensive EV. Surgical modalities and other destructive methods also have been tried.6

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis often can be confused with similar dermatoses. Porokeratosis appears as annular pink papules with waferlike peripheral scales. Tinea versicolor is a dermatophyte infection caused by Malassezia furfur and presents as multiple dyspigmented, finely scaling, thin papules and plaques. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus presents as pink, scaly, annular or psoriasiform papules and plaques most commonly on the trunk. Discoid lupus erythematosus presents as pink, hypopigmented or depigmented, atrophic plaques with a peripheral rim of erythema that indicates activity. Secondary syphilis, commonly denoted as the "great mimicker," presents as psoriasiform papules and plaques among other variable morphologies.

- Sa NB, Guerini MB, Barbato MT, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis: clinical presentation with varied forms of lesions. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S57-S60.

- Rogers HD, Macgregor JL, Nord KM, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:315-320.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Jacyk WK, De Villiers EM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:806-810.

- Fox SH, Elston DM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis and the risk for malignancy. Cutis. 2016;98:E10-E12.

- Shruti S, Siraj F, Singh A, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis: three case reports and a brief review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2017;26:59-61.

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis