User login

Provide appropriate sexual, reproductive health care for transgender patients

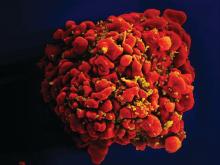

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

Walking the walk

In March 2018, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), an advocacy organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ people, released its 11th Annual Healthcare Equality Index. The HEI is an indicator of how inclusive and equitable health care facilities are in providing care for their LGBTQ patients. My own institution, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, scored very high on this index and received the “Leader in LGBTQ Healthcare Equality” designation. The process of receiving this designation is very rigorous, and I am proud of my institution for making great strides in expanding health care access for LGBTQ patients, especially transgender patients. However, this is no time to rest on one’s laurels, as many transgender people still experience challenges and barriers in navigating the health care system.

Insurance access continues to be a problem. I wrote a column in June 2017 about obtaining health care insurance for transgender patients. Preauthorization is common for obtaining cross-sex hormones or pubertal blockers even for insurance companies that are willing to pay for them – a process that can take weeks, even months, to complete. This creates delays in obtaining necessary care for transgender patients. This is just one of the many barriers transgender people face in navigating the health care system.

Increasing access to health care services for transgender patients is more about improving health outcomes than patient satisfaction. Even the smallest policy change may have a meaningful impact on the lives of transgender individuals. A study by Russell et al., in the April 2018 issue of Journal of Adolescent Health found that transgender youth allowed to use their chosen name (instead of the name assigned to them by their parents at birth) were more likely to have fewer depressive symptoms and lower rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.3 These findings highlight that even a small change can have a huge impact on the health and well-being of this patient population.

What can you do to expand access? First, you must educate yourself and teach others. Many providers report never having received education on LGBTQ health during their training,4 and most barriers for transgender patients stem from this lack of training. Second, work with the transgender community – it is very tempting to see your institution’s name on the HEI and think all the work is done, but the lived experiences of transgender patients sometimes are different than what is seen on paper (or online). Team up with local organizations such as PFLAG (formerly known as Parents and Families of Lesbians and Gays) that can create support groups for both transgender youth and their families. Help create a network of referral systems for your transgender patients – the community is often small enough that they know which providers or establishments are safe for transgender individuals. Many transgender patients find this extremely helpful.5 You still wield significant influence in the community, so work with the health care and insurance systems to improve access and coverage for gender-related services. The HRC HEI is becoming coveted by health care institutions. This is a prime opportunity to be involved in committees seeking to improve health care access for transgender individuals. Finally, as there are champions for transgender health in your clinic, there also are champions for transgender health in insurance companies. They often are well known in the community, so find that individual for counseling on how to navigate the insurance system for your transgender patients.

Although an increasing number of health care institutions and clinics are recognizing the health care needs of transgender patients and providing appropriate care, the health care system remains challenging for transgender individuals to navigate. Small policy changes may have a substantial impact on the health and well-being of transgender individuals. Although creating change within an institution may seem like a monumental task, you do have the agency to help create this type change within the system to expand health care access for transgender patients.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Resources

- HRC HEI: If you’re interested in learning what policies are inclusive and equitable for LGBT patients, check out the HRC HEI scoring criteria. It’s a good place to start if you want to expand health care access for transgender individuals.

- To find out more about the health care legal protections transgender individuals are entitled to, check out the National Center for Transgender Equality.

References

1. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

2. “Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” (Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.)

3. J. Adolesc Health. 2018 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003.

4. Int J Transgenderism. 2008. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_08.

5. Transgend Health. 2016 Nov 1;1(1):238-49.

In March 2018, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), an advocacy organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ people, released its 11th Annual Healthcare Equality Index. The HEI is an indicator of how inclusive and equitable health care facilities are in providing care for their LGBTQ patients. My own institution, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, scored very high on this index and received the “Leader in LGBTQ Healthcare Equality” designation. The process of receiving this designation is very rigorous, and I am proud of my institution for making great strides in expanding health care access for LGBTQ patients, especially transgender patients. However, this is no time to rest on one’s laurels, as many transgender people still experience challenges and barriers in navigating the health care system.

Insurance access continues to be a problem. I wrote a column in June 2017 about obtaining health care insurance for transgender patients. Preauthorization is common for obtaining cross-sex hormones or pubertal blockers even for insurance companies that are willing to pay for them – a process that can take weeks, even months, to complete. This creates delays in obtaining necessary care for transgender patients. This is just one of the many barriers transgender people face in navigating the health care system.

Increasing access to health care services for transgender patients is more about improving health outcomes than patient satisfaction. Even the smallest policy change may have a meaningful impact on the lives of transgender individuals. A study by Russell et al., in the April 2018 issue of Journal of Adolescent Health found that transgender youth allowed to use their chosen name (instead of the name assigned to them by their parents at birth) were more likely to have fewer depressive symptoms and lower rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.3 These findings highlight that even a small change can have a huge impact on the health and well-being of this patient population.

What can you do to expand access? First, you must educate yourself and teach others. Many providers report never having received education on LGBTQ health during their training,4 and most barriers for transgender patients stem from this lack of training. Second, work with the transgender community – it is very tempting to see your institution’s name on the HEI and think all the work is done, but the lived experiences of transgender patients sometimes are different than what is seen on paper (or online). Team up with local organizations such as PFLAG (formerly known as Parents and Families of Lesbians and Gays) that can create support groups for both transgender youth and their families. Help create a network of referral systems for your transgender patients – the community is often small enough that they know which providers or establishments are safe for transgender individuals. Many transgender patients find this extremely helpful.5 You still wield significant influence in the community, so work with the health care and insurance systems to improve access and coverage for gender-related services. The HRC HEI is becoming coveted by health care institutions. This is a prime opportunity to be involved in committees seeking to improve health care access for transgender individuals. Finally, as there are champions for transgender health in your clinic, there also are champions for transgender health in insurance companies. They often are well known in the community, so find that individual for counseling on how to navigate the insurance system for your transgender patients.

Although an increasing number of health care institutions and clinics are recognizing the health care needs of transgender patients and providing appropriate care, the health care system remains challenging for transgender individuals to navigate. Small policy changes may have a substantial impact on the health and well-being of transgender individuals. Although creating change within an institution may seem like a monumental task, you do have the agency to help create this type change within the system to expand health care access for transgender patients.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Resources

- HRC HEI: If you’re interested in learning what policies are inclusive and equitable for LGBT patients, check out the HRC HEI scoring criteria. It’s a good place to start if you want to expand health care access for transgender individuals.

- To find out more about the health care legal protections transgender individuals are entitled to, check out the National Center for Transgender Equality.

References

1. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

2. “Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” (Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.)

3. J. Adolesc Health. 2018 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003.

4. Int J Transgenderism. 2008. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_08.

5. Transgend Health. 2016 Nov 1;1(1):238-49.

In March 2018, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), an advocacy organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ people, released its 11th Annual Healthcare Equality Index. The HEI is an indicator of how inclusive and equitable health care facilities are in providing care for their LGBTQ patients. My own institution, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, scored very high on this index and received the “Leader in LGBTQ Healthcare Equality” designation. The process of receiving this designation is very rigorous, and I am proud of my institution for making great strides in expanding health care access for LGBTQ patients, especially transgender patients. However, this is no time to rest on one’s laurels, as many transgender people still experience challenges and barriers in navigating the health care system.

Insurance access continues to be a problem. I wrote a column in June 2017 about obtaining health care insurance for transgender patients. Preauthorization is common for obtaining cross-sex hormones or pubertal blockers even for insurance companies that are willing to pay for them – a process that can take weeks, even months, to complete. This creates delays in obtaining necessary care for transgender patients. This is just one of the many barriers transgender people face in navigating the health care system.

Increasing access to health care services for transgender patients is more about improving health outcomes than patient satisfaction. Even the smallest policy change may have a meaningful impact on the lives of transgender individuals. A study by Russell et al., in the April 2018 issue of Journal of Adolescent Health found that transgender youth allowed to use their chosen name (instead of the name assigned to them by their parents at birth) were more likely to have fewer depressive symptoms and lower rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.3 These findings highlight that even a small change can have a huge impact on the health and well-being of this patient population.

What can you do to expand access? First, you must educate yourself and teach others. Many providers report never having received education on LGBTQ health during their training,4 and most barriers for transgender patients stem from this lack of training. Second, work with the transgender community – it is very tempting to see your institution’s name on the HEI and think all the work is done, but the lived experiences of transgender patients sometimes are different than what is seen on paper (or online). Team up with local organizations such as PFLAG (formerly known as Parents and Families of Lesbians and Gays) that can create support groups for both transgender youth and their families. Help create a network of referral systems for your transgender patients – the community is often small enough that they know which providers or establishments are safe for transgender individuals. Many transgender patients find this extremely helpful.5 You still wield significant influence in the community, so work with the health care and insurance systems to improve access and coverage for gender-related services. The HRC HEI is becoming coveted by health care institutions. This is a prime opportunity to be involved in committees seeking to improve health care access for transgender individuals. Finally, as there are champions for transgender health in your clinic, there also are champions for transgender health in insurance companies. They often are well known in the community, so find that individual for counseling on how to navigate the insurance system for your transgender patients.

Although an increasing number of health care institutions and clinics are recognizing the health care needs of transgender patients and providing appropriate care, the health care system remains challenging for transgender individuals to navigate. Small policy changes may have a substantial impact on the health and well-being of transgender individuals. Although creating change within an institution may seem like a monumental task, you do have the agency to help create this type change within the system to expand health care access for transgender patients.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Resources

- HRC HEI: If you’re interested in learning what policies are inclusive and equitable for LGBT patients, check out the HRC HEI scoring criteria. It’s a good place to start if you want to expand health care access for transgender individuals.

- To find out more about the health care legal protections transgender individuals are entitled to, check out the National Center for Transgender Equality.

References

1. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

2. “Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” (Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.)

3. J. Adolesc Health. 2018 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003.

4. Int J Transgenderism. 2008. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_08.

5. Transgend Health. 2016 Nov 1;1(1):238-49.

Preexposure prophylaxis among LGBT youth

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Confronting hate and violence against the LGBT community

It may be unusual for an LGBT health columnist to mention the horrendous events that occurred in Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017. It clearly was a demonstration of hate and violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Unfortunately, the LGBT community – especially LGBT communities of color – are often a target of that kind of hate and violence. This has a detrimental effect on the health of the LGBT community, and I believe that health care providers have a responsibility to address this hate and violence to promote the well-being of this marginalized community.

It cannot be overstated that LGBT individuals frequently experience anti-gay and anti-trans violence. According to the 2015 Federal Bureau of Investigation Hate Crime Statistics, about a fifth of hate crimes reported were based on sexual orientation or gender identity.1 In addition, LGBT youth are eight times as likely to experience bullying at school because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.2 Furthermore, on many surveys on anti-LGBT violence, people of color comprise more than half of the victims.3 There is a strong association between exposure to this violence and the health outcomes of LGBT youth. A study by Russell et al. showed that LGBT youth who were victims of physical violence at school are more likely to be depressed and suicidal and more likely to be diagnosed with an STD,4 and another study showed that LGBT youth who experienced anti-LGBT violence are more likely to engage in substance use.5 The health outcomes from anti-LGBT violence are not limited to the adolescent period – adolescents who experienced this kind of violence are more likely to report higher levels of depression as adults.6 Although researchers still are trying to determine the exact mechanism for these relationships, the most cited (and sensible) explanation is that exposure to anti-LGBT stigma, discrimination, and violence leads to a toxic environment, which in turn increases the risk for mental health problems and maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as substance use) as a response to such an environment.7

What can we do to stand up to the hate and violence against marginalized groups, such as the LGBT community? First, make your office a safe space. With the recent brazen display of hate and violence going around, members the LGBT community are desperate to feel protected. A good place to start is a guide by Advocates for Youth. Second, educate yourself and others. The title physician means “teacher,” and I feel it is your responsibility to teach your peers, colleagues, and the public about how anti-LGBT violence affects the health of LGBT individuals. To be an effective teacher, you need to be up to date on the research on how hatred and intolerance affects the health of the LGBT community. A good place to start is the Human Rights Campaign, which has accurate statistics on anti-LGBT violence and resources to address this problem. Finally, be an advocate. You don’t need to be in the streets with picket signs, nor do you necessarily need to lead the charge against anti-LGBT hate and violence – others will be at the front lines. What you can do is to call for your local, state, and federal government to institute policies that address anti-LGBT violence. Many medical organizations have resources that help health care providers engage with policy makers (check out the American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page for these resources). Many of our elected officials take our professional opinions seriously.

Anti-gay and anti-trans violence is all too common in the LGBT community, especially violence against LGBT people of color, and this violence can adversely affect their health. Health care providers have a responsibility and the influence to confront these nexuses of hate and intolerance. You don’t need to do something heroic to accomplish this. You are members of a privileged and respected group of professionals, so small actions can coalesce into something that has a large impact on the health and well-being of the communities you serve.

Resources

• Advocates for Youth. Creating Safe Space for GLBTQ Youth: A Toolkit

• Human Rights Campaign. www.hrc.org/resources/

• American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page: www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/

References

1. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Report Hate Crime Statistics, 2015.

2. J Interpers Violence. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718830.

3. National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and HIV-Affected Hate Violence in 2016.

4. J Sch Health. 2011 May;81(5):223-30.

5. Prev Sci. 2015 Jul;16(5):734-43.

6. Dev Psychol. 2010 Nov;46(6):1580-9.

7. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

8. Gallup. Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics. 2016.

9. The Hippocratic Oath Today. 2001 or Do. No. Harm.

It may be unusual for an LGBT health columnist to mention the horrendous events that occurred in Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017. It clearly was a demonstration of hate and violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Unfortunately, the LGBT community – especially LGBT communities of color – are often a target of that kind of hate and violence. This has a detrimental effect on the health of the LGBT community, and I believe that health care providers have a responsibility to address this hate and violence to promote the well-being of this marginalized community.

It cannot be overstated that LGBT individuals frequently experience anti-gay and anti-trans violence. According to the 2015 Federal Bureau of Investigation Hate Crime Statistics, about a fifth of hate crimes reported were based on sexual orientation or gender identity.1 In addition, LGBT youth are eight times as likely to experience bullying at school because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.2 Furthermore, on many surveys on anti-LGBT violence, people of color comprise more than half of the victims.3 There is a strong association between exposure to this violence and the health outcomes of LGBT youth. A study by Russell et al. showed that LGBT youth who were victims of physical violence at school are more likely to be depressed and suicidal and more likely to be diagnosed with an STD,4 and another study showed that LGBT youth who experienced anti-LGBT violence are more likely to engage in substance use.5 The health outcomes from anti-LGBT violence are not limited to the adolescent period – adolescents who experienced this kind of violence are more likely to report higher levels of depression as adults.6 Although researchers still are trying to determine the exact mechanism for these relationships, the most cited (and sensible) explanation is that exposure to anti-LGBT stigma, discrimination, and violence leads to a toxic environment, which in turn increases the risk for mental health problems and maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as substance use) as a response to such an environment.7

What can we do to stand up to the hate and violence against marginalized groups, such as the LGBT community? First, make your office a safe space. With the recent brazen display of hate and violence going around, members the LGBT community are desperate to feel protected. A good place to start is a guide by Advocates for Youth. Second, educate yourself and others. The title physician means “teacher,” and I feel it is your responsibility to teach your peers, colleagues, and the public about how anti-LGBT violence affects the health of LGBT individuals. To be an effective teacher, you need to be up to date on the research on how hatred and intolerance affects the health of the LGBT community. A good place to start is the Human Rights Campaign, which has accurate statistics on anti-LGBT violence and resources to address this problem. Finally, be an advocate. You don’t need to be in the streets with picket signs, nor do you necessarily need to lead the charge against anti-LGBT hate and violence – others will be at the front lines. What you can do is to call for your local, state, and federal government to institute policies that address anti-LGBT violence. Many medical organizations have resources that help health care providers engage with policy makers (check out the American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page for these resources). Many of our elected officials take our professional opinions seriously.

Anti-gay and anti-trans violence is all too common in the LGBT community, especially violence against LGBT people of color, and this violence can adversely affect their health. Health care providers have a responsibility and the influence to confront these nexuses of hate and intolerance. You don’t need to do something heroic to accomplish this. You are members of a privileged and respected group of professionals, so small actions can coalesce into something that has a large impact on the health and well-being of the communities you serve.

Resources

• Advocates for Youth. Creating Safe Space for GLBTQ Youth: A Toolkit

• Human Rights Campaign. www.hrc.org/resources/

• American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page: www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/

References

1. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Report Hate Crime Statistics, 2015.

2. J Interpers Violence. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718830.

3. National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and HIV-Affected Hate Violence in 2016.

4. J Sch Health. 2011 May;81(5):223-30.

5. Prev Sci. 2015 Jul;16(5):734-43.

6. Dev Psychol. 2010 Nov;46(6):1580-9.

7. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

8. Gallup. Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics. 2016.

9. The Hippocratic Oath Today. 2001 or Do. No. Harm.

It may be unusual for an LGBT health columnist to mention the horrendous events that occurred in Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017. It clearly was a demonstration of hate and violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Unfortunately, the LGBT community – especially LGBT communities of color – are often a target of that kind of hate and violence. This has a detrimental effect on the health of the LGBT community, and I believe that health care providers have a responsibility to address this hate and violence to promote the well-being of this marginalized community.

It cannot be overstated that LGBT individuals frequently experience anti-gay and anti-trans violence. According to the 2015 Federal Bureau of Investigation Hate Crime Statistics, about a fifth of hate crimes reported were based on sexual orientation or gender identity.1 In addition, LGBT youth are eight times as likely to experience bullying at school because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.2 Furthermore, on many surveys on anti-LGBT violence, people of color comprise more than half of the victims.3 There is a strong association between exposure to this violence and the health outcomes of LGBT youth. A study by Russell et al. showed that LGBT youth who were victims of physical violence at school are more likely to be depressed and suicidal and more likely to be diagnosed with an STD,4 and another study showed that LGBT youth who experienced anti-LGBT violence are more likely to engage in substance use.5 The health outcomes from anti-LGBT violence are not limited to the adolescent period – adolescents who experienced this kind of violence are more likely to report higher levels of depression as adults.6 Although researchers still are trying to determine the exact mechanism for these relationships, the most cited (and sensible) explanation is that exposure to anti-LGBT stigma, discrimination, and violence leads to a toxic environment, which in turn increases the risk for mental health problems and maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as substance use) as a response to such an environment.7

What can we do to stand up to the hate and violence against marginalized groups, such as the LGBT community? First, make your office a safe space. With the recent brazen display of hate and violence going around, members the LGBT community are desperate to feel protected. A good place to start is a guide by Advocates for Youth. Second, educate yourself and others. The title physician means “teacher,” and I feel it is your responsibility to teach your peers, colleagues, and the public about how anti-LGBT violence affects the health of LGBT individuals. To be an effective teacher, you need to be up to date on the research on how hatred and intolerance affects the health of the LGBT community. A good place to start is the Human Rights Campaign, which has accurate statistics on anti-LGBT violence and resources to address this problem. Finally, be an advocate. You don’t need to be in the streets with picket signs, nor do you necessarily need to lead the charge against anti-LGBT hate and violence – others will be at the front lines. What you can do is to call for your local, state, and federal government to institute policies that address anti-LGBT violence. Many medical organizations have resources that help health care providers engage with policy makers (check out the American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page for these resources). Many of our elected officials take our professional opinions seriously.

Anti-gay and anti-trans violence is all too common in the LGBT community, especially violence against LGBT people of color, and this violence can adversely affect their health. Health care providers have a responsibility and the influence to confront these nexuses of hate and intolerance. You don’t need to do something heroic to accomplish this. You are members of a privileged and respected group of professionals, so small actions can coalesce into something that has a large impact on the health and well-being of the communities you serve.

Resources

• Advocates for Youth. Creating Safe Space for GLBTQ Youth: A Toolkit

• Human Rights Campaign. www.hrc.org/resources/

• American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page: www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/

References

1. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Report Hate Crime Statistics, 2015.

2. J Interpers Violence. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718830.

3. National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and HIV-Affected Hate Violence in 2016.

4. J Sch Health. 2011 May;81(5):223-30.

5. Prev Sci. 2015 Jul;16(5):734-43.

6. Dev Psychol. 2010 Nov;46(6):1580-9.

7. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

8. Gallup. Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics. 2016.

9. The Hippocratic Oath Today. 2001 or Do. No. Harm.

Obtaining coverage for transgender and gender-expansive youth

Transgender and gender-expansive youth face many barriers to health care. (Gender-expansive youth are defined as “youth who do not identify with traditional gender roles but are otherwise not confined to one gender narrative or experience.”) Although some of these youth may be fortunate to have a supportive family and access to health care providers proficient in transgender health care, they still face difficulties in having their insurance cover transgender-related services. This is not an impossible task, but it is a constant struggle for many clinicians.

In this column, I will provide some tips and strategies to help clinicians get insurance companies to cover these critical services. However, keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to obtaining insurance coverage. In addition, growing uncertainty over the repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – which was critical in lifting many of the barriers to insurance coverage for transgender individuals – will make this task challenging.

Health insurance is extraordinarily complex. There are multiple private and public plans that vary in the services they cover. This variation is state dependent. And even within states, there is additional variability. Most health insurance plans are purchased by employers, and employers have a choice of what can be covered in their health plans. So even though an insurance company may state that it covers transgender-related services, the patient’s employer may pay for a plan that doesn’t cover such services. The only way to be sure whether a patient’s insurance will cover transgender-related services or not is to contact the insurance provider directly, but with extremely busy schedules and heavy patient loads, this is easier said than done. It would be helpful to have a social worker perform this task, but even having a social worker can be a luxury for some clinics.

The ACA made it easier for transgender individuals to obtain insurance coverage. Three years ago, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services stated that Medicare’s longstanding exclusion of “transsexual surgical procedures” was no longer valid.1 Although it did not universally ban transgender exclusion policies, it did allow individual states to do so. Thirteen states have explicit policies that ban exclusions of transgender-related services in both private insurance and in Medicaid, and an additional five states have some policies that discourage such practices.2 This allowed some insurance providers and state Medicaid plans to offer coverage of transgender-related services.

Another challenge in obtaining insurance coverage for transgender and gender-expansive youth is claims denial for sex-specific procedures. For example, if a transwoman is designated as “male” in the electronic medical record and requires a breast ultrasound, the insurance company may automatically reject this claim because this procedure is covered for bodies designated as “female.” If the patient’s insurance plan covers transgender-related services, the clinic can notify the insurance company that the patient is transgender; if the patient’s plan does not, then the clinic will need to appeal to the insurance provider. Alternatively, for clinics associated with federally-funded institutions (e.g., most hospitals), the clinician can use Condition Code 45 in the billing to override the sex mismatch, although not all hospitals have implemented this code.3

1. Patient’s identifying information. Usually the patient’s name and date of birth is sufficient. Clinicians should use the patient’s preferred name in the letter, but provide the insurance or legal name of the patient so that the insurance provider can locate the patient’s records.

2. Result of a psychosocial evaluation and diagnosis (if any). Many insurance providers are looking specifically for the gender dysphoria diagnosis.

3. The duration of the referring health professional’s relationship with the patient, which includes the type of evaluation and therapy or counseling (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy or gender coaching).

4. An explanation that the criteria (usually from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health standard of care4 or the Endocrine Society Guidelines titled Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons5) for hormone therapy have been met, and a brief description of the clinical rationale for supporting the client’s request for hormone therapy.

5. A statement that informed consent has been obtained from the patient (or parental permission if the patient is younger than 18 years).

6. A statement that the referring health professional is available for coordination of care.

If the clinician fails to convince the insurance provider of the necessity of covering transgender-related services, the patient still can pay out of pocket. Some hormones can be affordable to certain patients. In the state of Pennsylvania, for example, a 10-mL vial of testosterone can cost anywhere from $60 to $80, and may generally last anywhere from 10 weeks to a year, depending on dosage. Nevertheless, these costs still may be prohibitive for many transgender youth. Many are chronically unemployed or underemployed, or struggle with homelessness.6 Some transgender youth have to the face the excruciatingly difficult choice between having something to eat for the day or living another day with gender dysphoria.

Clinicians should work very hard to make sure that their transgender and gender-expansive patients obtain the care they need. The above strategies may help navigate the complex insurance system. However, insurance policies vary by state, and anti-trans discrimination creates additional barriers to health care. Therefore, clinicians who take care of transgender youth also should advocate for policies that protect these patients from discrimination, and they should advocate for policies that expand medical coverage for this vulnerable population.

Resources

• The Human Rights Campaign keeps a list of insurance plans that cover transgender-related services, but this list is far from comprehensive.

• Healthcare.gov provides some guidance on how to obtain coverage and navigate the insurance system for transgender individuals.

• UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health provides some excellent resources and guidance on obtaining insurance coverage for transgender individuals.

References

1. LGBT Health 2014;1(4):256-8.

2. Map: State Health Insurance Rules: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016 [Available from: www.transequality.org/issues/resources/map-state-health-insurance-rules].

3. Health insurance coverage issues for transgender people in the United States: University of California, San Fransisco Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, 2017 [Available from: http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=guidelines-insurance].

4. International Journal of Transgenderism 2012;13(4):165-232.

5. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94(9):3132-54.

6. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.

Transgender and gender-expansive youth face many barriers to health care. (Gender-expansive youth are defined as “youth who do not identify with traditional gender roles but are otherwise not confined to one gender narrative or experience.”) Although some of these youth may be fortunate to have a supportive family and access to health care providers proficient in transgender health care, they still face difficulties in having their insurance cover transgender-related services. This is not an impossible task, but it is a constant struggle for many clinicians.

In this column, I will provide some tips and strategies to help clinicians get insurance companies to cover these critical services. However, keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to obtaining insurance coverage. In addition, growing uncertainty over the repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – which was critical in lifting many of the barriers to insurance coverage for transgender individuals – will make this task challenging.

Health insurance is extraordinarily complex. There are multiple private and public plans that vary in the services they cover. This variation is state dependent. And even within states, there is additional variability. Most health insurance plans are purchased by employers, and employers have a choice of what can be covered in their health plans. So even though an insurance company may state that it covers transgender-related services, the patient’s employer may pay for a plan that doesn’t cover such services. The only way to be sure whether a patient’s insurance will cover transgender-related services or not is to contact the insurance provider directly, but with extremely busy schedules and heavy patient loads, this is easier said than done. It would be helpful to have a social worker perform this task, but even having a social worker can be a luxury for some clinics.

The ACA made it easier for transgender individuals to obtain insurance coverage. Three years ago, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services stated that Medicare’s longstanding exclusion of “transsexual surgical procedures” was no longer valid.1 Although it did not universally ban transgender exclusion policies, it did allow individual states to do so. Thirteen states have explicit policies that ban exclusions of transgender-related services in both private insurance and in Medicaid, and an additional five states have some policies that discourage such practices.2 This allowed some insurance providers and state Medicaid plans to offer coverage of transgender-related services.

Another challenge in obtaining insurance coverage for transgender and gender-expansive youth is claims denial for sex-specific procedures. For example, if a transwoman is designated as “male” in the electronic medical record and requires a breast ultrasound, the insurance company may automatically reject this claim because this procedure is covered for bodies designated as “female.” If the patient’s insurance plan covers transgender-related services, the clinic can notify the insurance company that the patient is transgender; if the patient’s plan does not, then the clinic will need to appeal to the insurance provider. Alternatively, for clinics associated with federally-funded institutions (e.g., most hospitals), the clinician can use Condition Code 45 in the billing to override the sex mismatch, although not all hospitals have implemented this code.3

1. Patient’s identifying information. Usually the patient’s name and date of birth is sufficient. Clinicians should use the patient’s preferred name in the letter, but provide the insurance or legal name of the patient so that the insurance provider can locate the patient’s records.

2. Result of a psychosocial evaluation and diagnosis (if any). Many insurance providers are looking specifically for the gender dysphoria diagnosis.

3. The duration of the referring health professional’s relationship with the patient, which includes the type of evaluation and therapy or counseling (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy or gender coaching).

4. An explanation that the criteria (usually from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health standard of care4 or the Endocrine Society Guidelines titled Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons5) for hormone therapy have been met, and a brief description of the clinical rationale for supporting the client’s request for hormone therapy.

5. A statement that informed consent has been obtained from the patient (or parental permission if the patient is younger than 18 years).

6. A statement that the referring health professional is available for coordination of care.