User login

The most important question in medicine

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Today I am going to tell you the single best question you can ask any doctor, the one that has saved my butt countless times throughout my career, the one that every attending physician should be asking every intern and resident when they present a new case. That question: “What else could this be?”

I know, I know – “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” I get it. But sometimes we get so good at our jobs, so good at recognizing horses, that we stop asking ourselves about zebras at all. You see this in a phenomenon known as “anchoring bias” where physicians, when presented with a diagnosis, tend to latch on to that diagnosis based on the first piece of information given, paying attention to data that support it and ignoring data that point in other directions.

That special question: “What else could this be?”, breaks through that barrier. It forces you, the medical team, everyone, to go through the exercise of real, old-fashioned differential diagnosis. And I promise that if you do this enough, at some point it will save someone’s life.

Though the concept of anchoring bias in medicine is broadly understood, it hasn’t been broadly studied until now, with this study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Here’s the setup.

The authors hypothesized that there would be substantial anchoring bias when patients with heart failure presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath if the triage “visit reason” section mentioned HF. We’re talking about the subtle difference between the following:

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath/HF

People with HF can be short of breath for lots of reasons. HF exacerbation comes immediately to mind and it should. But there are obviously lots of answers to that “What else could this be?” question: pneumonia, pneumothorax, heart attack, COPD, and, of course, pulmonary embolism (PE).

The authors leveraged the nationwide VA database, allowing them to examine data from over 100,000 patients presenting to various VA EDs with shortness of breath. They then looked for particular tests – D-dimer, CT chest with contrast, V/Q scan, lower-extremity Doppler — that would suggest that the doctor was thinking about PE. The question, then, is whether mentioning HF in that little “visit reason” section would influence the likelihood of testing for PE.

I know what you’re thinking: Not everyone who is short of breath needs an evaluation for PE. And the authors did a nice job accounting for a variety of factors that might predict a PE workup: malignancy, recent surgery, elevated heart rate, low oxygen saturation, etc. Of course, some of those same factors might predict whether that triage nurse will write HF in the visit reason section. All of these things need to be accounted for statistically, and were, but – the unofficial Impact Factor motto reminds us that “there are always more confounders.”

But let’s dig into the results. I’m going to give you the raw numbers first. There were 4,392 people with HF whose visit reason section, in addition to noting shortness of breath, explicitly mentioned HF. Of those, 360 had PE testing and two had a PE diagnosed during that ED visit. So that’s around an 8% testing rate and a 0.5% hit rate for testing. But 43 people, presumably not tested in the ED, had a PE diagnosed within the next 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were present at the ED visit, that means the ED missed 95% of the PEs in the group with that HF label attached to them.

Let’s do the same thing for those whose visit reason just said “shortness of breath.”

Of the 103,627 people in that category, 13,886 were tested for PE and 231 of those tested positive. So that is an overall testing rate of around 13% and a hit rate of 1.7%. And 1,081 of these people had a PE diagnosed within 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were actually present at the ED visit, the docs missed 79% of them.

There’s one other thing to notice from the data: The overall PE rate (diagnosed by 30 days) was basically the same in both groups. That HF label does not really flag a group at lower risk for PE.

Yes, there are a lot of assumptions here, including that all PEs that were actually there in the ED got caught within 30 days, but the numbers do paint a picture. In this unadjusted analysis, it seems that the HF label leads to less testing and more missed PEs. Classic anchoring bias.

The adjusted analysis, accounting for all those PE risk factors, really didn’t change these results. You get nearly the same numbers and thus nearly the same conclusions.

Now, the main missing piece of this puzzle is in the mind of the clinician. We don’t know whether they didn’t consider PE or whether they considered PE but thought it unlikely. And in the end, it’s clear that the vast majority of people in this study did not have PE (though I suspect not all had a simple HF exacerbation). But this type of analysis is useful not only for the empiric evidence of the clinical impact of anchoring bias but because of the fact that it reminds us all to ask that all-important question: What else could this be?

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Today I am going to tell you the single best question you can ask any doctor, the one that has saved my butt countless times throughout my career, the one that every attending physician should be asking every intern and resident when they present a new case. That question: “What else could this be?”

I know, I know – “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” I get it. But sometimes we get so good at our jobs, so good at recognizing horses, that we stop asking ourselves about zebras at all. You see this in a phenomenon known as “anchoring bias” where physicians, when presented with a diagnosis, tend to latch on to that diagnosis based on the first piece of information given, paying attention to data that support it and ignoring data that point in other directions.

That special question: “What else could this be?”, breaks through that barrier. It forces you, the medical team, everyone, to go through the exercise of real, old-fashioned differential diagnosis. And I promise that if you do this enough, at some point it will save someone’s life.

Though the concept of anchoring bias in medicine is broadly understood, it hasn’t been broadly studied until now, with this study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Here’s the setup.

The authors hypothesized that there would be substantial anchoring bias when patients with heart failure presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath if the triage “visit reason” section mentioned HF. We’re talking about the subtle difference between the following:

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath/HF

People with HF can be short of breath for lots of reasons. HF exacerbation comes immediately to mind and it should. But there are obviously lots of answers to that “What else could this be?” question: pneumonia, pneumothorax, heart attack, COPD, and, of course, pulmonary embolism (PE).

The authors leveraged the nationwide VA database, allowing them to examine data from over 100,000 patients presenting to various VA EDs with shortness of breath. They then looked for particular tests – D-dimer, CT chest with contrast, V/Q scan, lower-extremity Doppler — that would suggest that the doctor was thinking about PE. The question, then, is whether mentioning HF in that little “visit reason” section would influence the likelihood of testing for PE.

I know what you’re thinking: Not everyone who is short of breath needs an evaluation for PE. And the authors did a nice job accounting for a variety of factors that might predict a PE workup: malignancy, recent surgery, elevated heart rate, low oxygen saturation, etc. Of course, some of those same factors might predict whether that triage nurse will write HF in the visit reason section. All of these things need to be accounted for statistically, and were, but – the unofficial Impact Factor motto reminds us that “there are always more confounders.”

But let’s dig into the results. I’m going to give you the raw numbers first. There were 4,392 people with HF whose visit reason section, in addition to noting shortness of breath, explicitly mentioned HF. Of those, 360 had PE testing and two had a PE diagnosed during that ED visit. So that’s around an 8% testing rate and a 0.5% hit rate for testing. But 43 people, presumably not tested in the ED, had a PE diagnosed within the next 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were present at the ED visit, that means the ED missed 95% of the PEs in the group with that HF label attached to them.

Let’s do the same thing for those whose visit reason just said “shortness of breath.”

Of the 103,627 people in that category, 13,886 were tested for PE and 231 of those tested positive. So that is an overall testing rate of around 13% and a hit rate of 1.7%. And 1,081 of these people had a PE diagnosed within 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were actually present at the ED visit, the docs missed 79% of them.

There’s one other thing to notice from the data: The overall PE rate (diagnosed by 30 days) was basically the same in both groups. That HF label does not really flag a group at lower risk for PE.

Yes, there are a lot of assumptions here, including that all PEs that were actually there in the ED got caught within 30 days, but the numbers do paint a picture. In this unadjusted analysis, it seems that the HF label leads to less testing and more missed PEs. Classic anchoring bias.

The adjusted analysis, accounting for all those PE risk factors, really didn’t change these results. You get nearly the same numbers and thus nearly the same conclusions.

Now, the main missing piece of this puzzle is in the mind of the clinician. We don’t know whether they didn’t consider PE or whether they considered PE but thought it unlikely. And in the end, it’s clear that the vast majority of people in this study did not have PE (though I suspect not all had a simple HF exacerbation). But this type of analysis is useful not only for the empiric evidence of the clinical impact of anchoring bias but because of the fact that it reminds us all to ask that all-important question: What else could this be?

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Today I am going to tell you the single best question you can ask any doctor, the one that has saved my butt countless times throughout my career, the one that every attending physician should be asking every intern and resident when they present a new case. That question: “What else could this be?”

I know, I know – “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” I get it. But sometimes we get so good at our jobs, so good at recognizing horses, that we stop asking ourselves about zebras at all. You see this in a phenomenon known as “anchoring bias” where physicians, when presented with a diagnosis, tend to latch on to that diagnosis based on the first piece of information given, paying attention to data that support it and ignoring data that point in other directions.

That special question: “What else could this be?”, breaks through that barrier. It forces you, the medical team, everyone, to go through the exercise of real, old-fashioned differential diagnosis. And I promise that if you do this enough, at some point it will save someone’s life.

Though the concept of anchoring bias in medicine is broadly understood, it hasn’t been broadly studied until now, with this study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Here’s the setup.

The authors hypothesized that there would be substantial anchoring bias when patients with heart failure presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath if the triage “visit reason” section mentioned HF. We’re talking about the subtle difference between the following:

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath/HF

People with HF can be short of breath for lots of reasons. HF exacerbation comes immediately to mind and it should. But there are obviously lots of answers to that “What else could this be?” question: pneumonia, pneumothorax, heart attack, COPD, and, of course, pulmonary embolism (PE).

The authors leveraged the nationwide VA database, allowing them to examine data from over 100,000 patients presenting to various VA EDs with shortness of breath. They then looked for particular tests – D-dimer, CT chest with contrast, V/Q scan, lower-extremity Doppler — that would suggest that the doctor was thinking about PE. The question, then, is whether mentioning HF in that little “visit reason” section would influence the likelihood of testing for PE.

I know what you’re thinking: Not everyone who is short of breath needs an evaluation for PE. And the authors did a nice job accounting for a variety of factors that might predict a PE workup: malignancy, recent surgery, elevated heart rate, low oxygen saturation, etc. Of course, some of those same factors might predict whether that triage nurse will write HF in the visit reason section. All of these things need to be accounted for statistically, and were, but – the unofficial Impact Factor motto reminds us that “there are always more confounders.”

But let’s dig into the results. I’m going to give you the raw numbers first. There were 4,392 people with HF whose visit reason section, in addition to noting shortness of breath, explicitly mentioned HF. Of those, 360 had PE testing and two had a PE diagnosed during that ED visit. So that’s around an 8% testing rate and a 0.5% hit rate for testing. But 43 people, presumably not tested in the ED, had a PE diagnosed within the next 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were present at the ED visit, that means the ED missed 95% of the PEs in the group with that HF label attached to them.

Let’s do the same thing for those whose visit reason just said “shortness of breath.”

Of the 103,627 people in that category, 13,886 were tested for PE and 231 of those tested positive. So that is an overall testing rate of around 13% and a hit rate of 1.7%. And 1,081 of these people had a PE diagnosed within 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were actually present at the ED visit, the docs missed 79% of them.

There’s one other thing to notice from the data: The overall PE rate (diagnosed by 30 days) was basically the same in both groups. That HF label does not really flag a group at lower risk for PE.

Yes, there are a lot of assumptions here, including that all PEs that were actually there in the ED got caught within 30 days, but the numbers do paint a picture. In this unadjusted analysis, it seems that the HF label leads to less testing and more missed PEs. Classic anchoring bias.

The adjusted analysis, accounting for all those PE risk factors, really didn’t change these results. You get nearly the same numbers and thus nearly the same conclusions.

Now, the main missing piece of this puzzle is in the mind of the clinician. We don’t know whether they didn’t consider PE or whether they considered PE but thought it unlikely. And in the end, it’s clear that the vast majority of people in this study did not have PE (though I suspect not all had a simple HF exacerbation). But this type of analysis is useful not only for the empiric evidence of the clinical impact of anchoring bias but because of the fact that it reminds us all to ask that all-important question: What else could this be?

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The cardiopulmonary effects of mask wearing

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

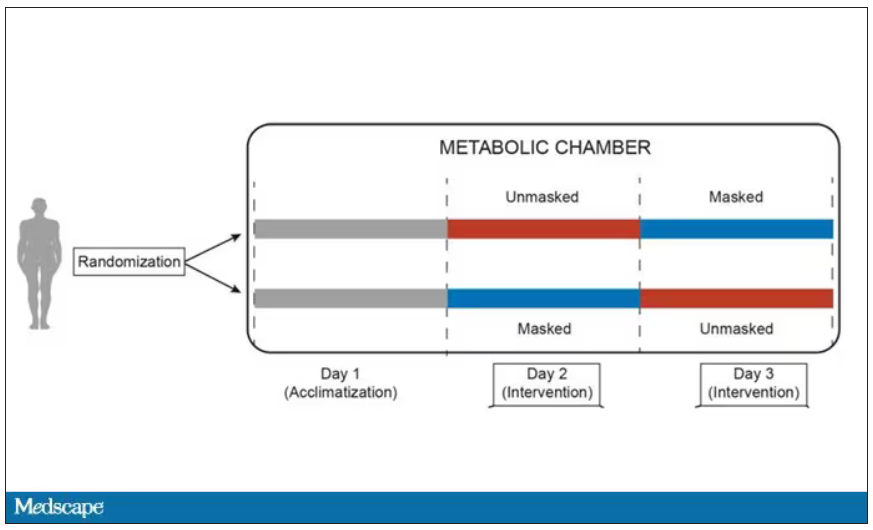

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

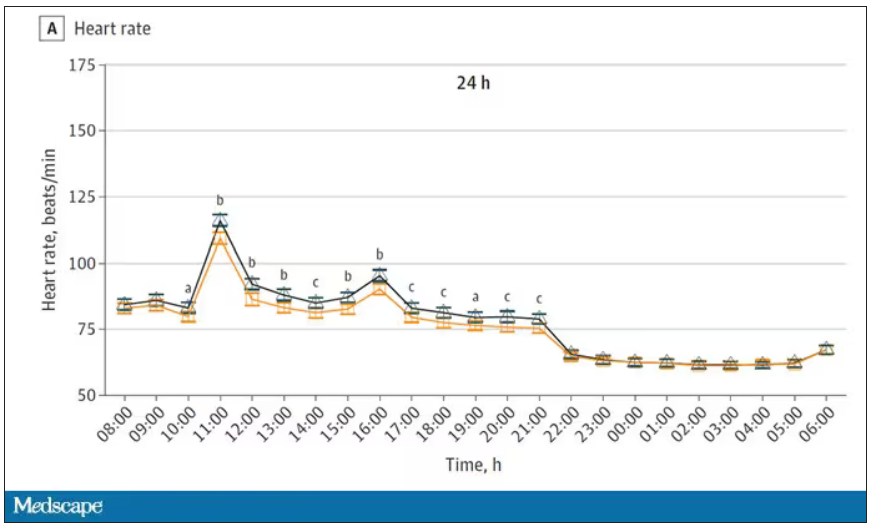

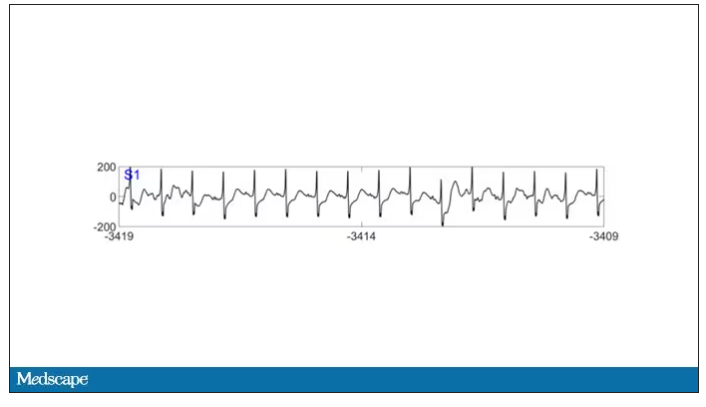

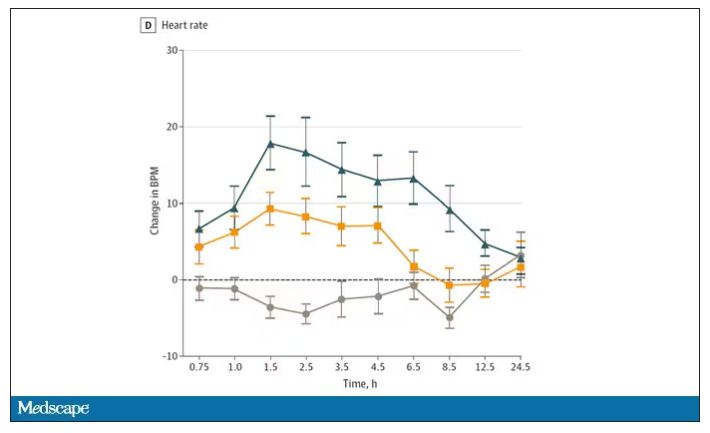

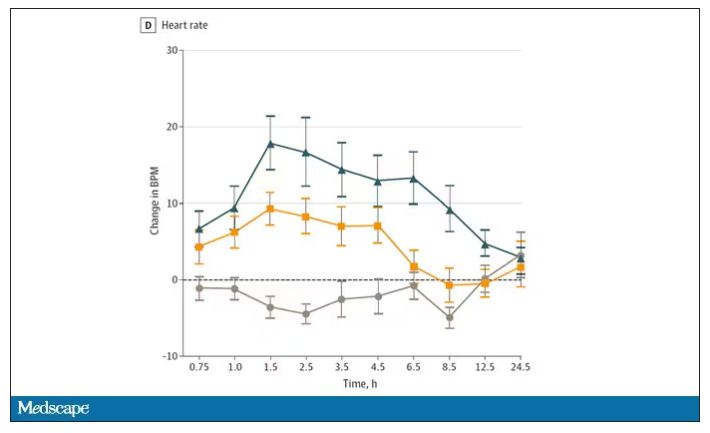

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

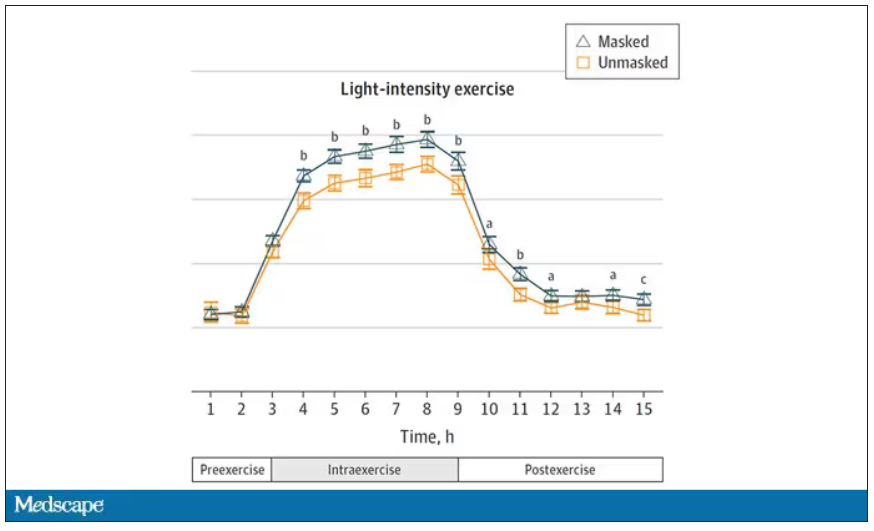

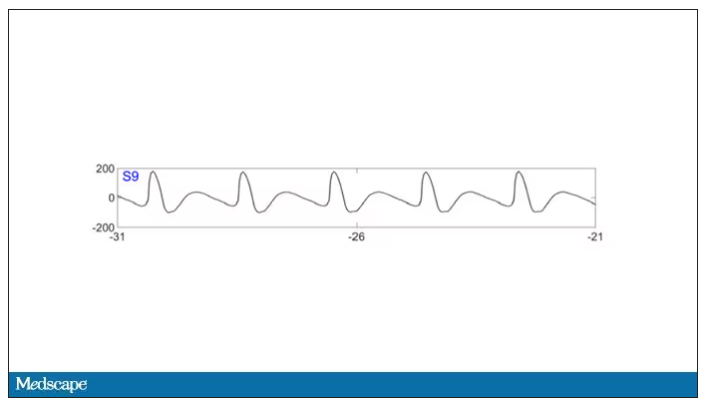

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID boosters effective, but not for long

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

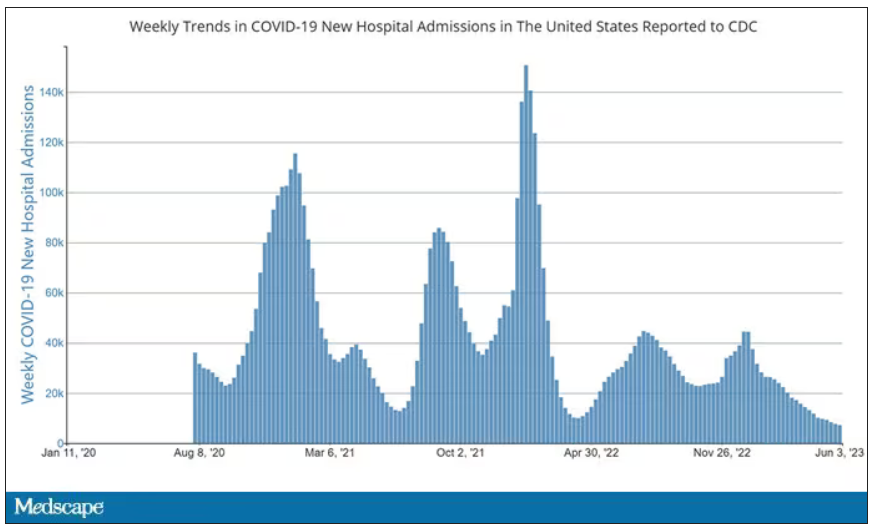

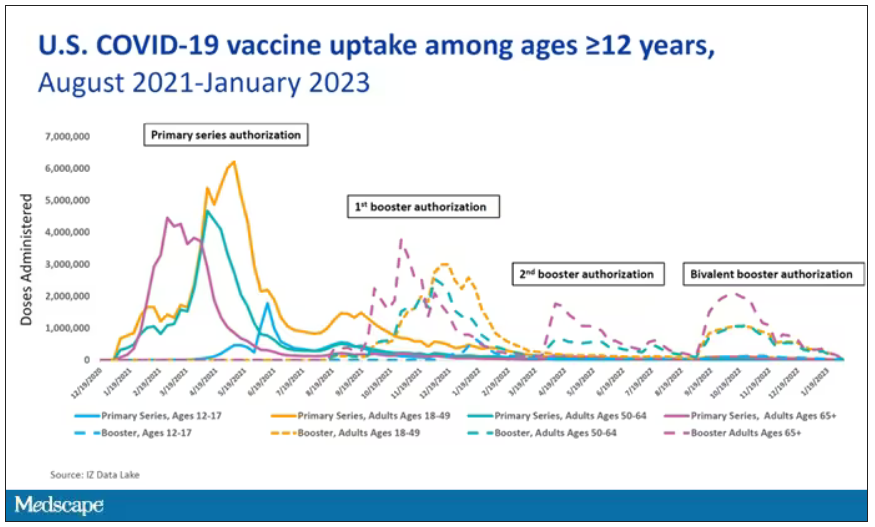

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

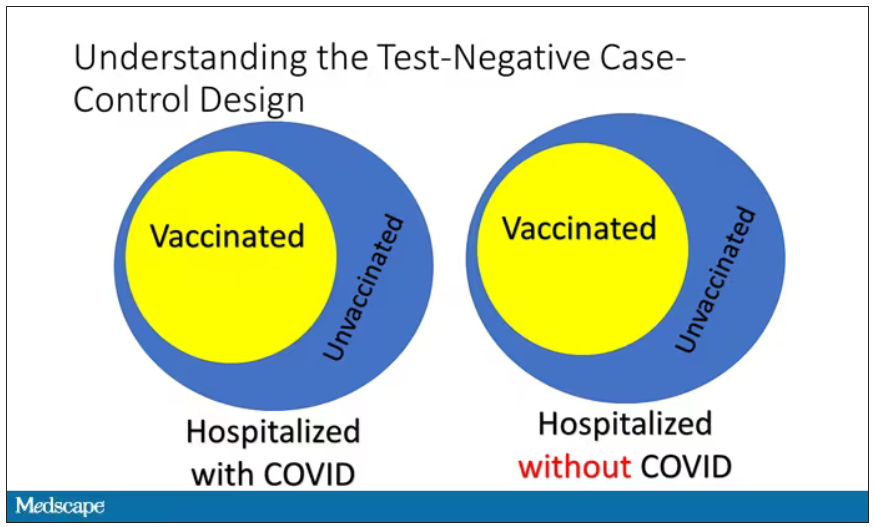

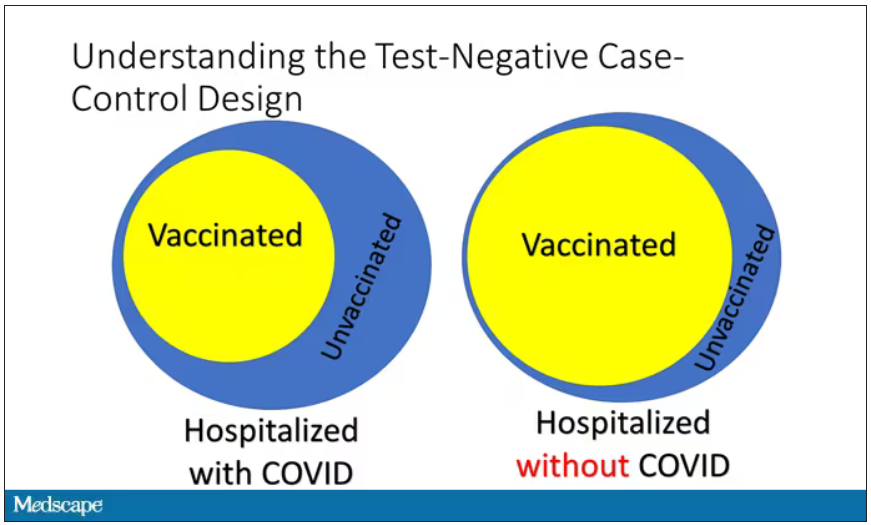

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

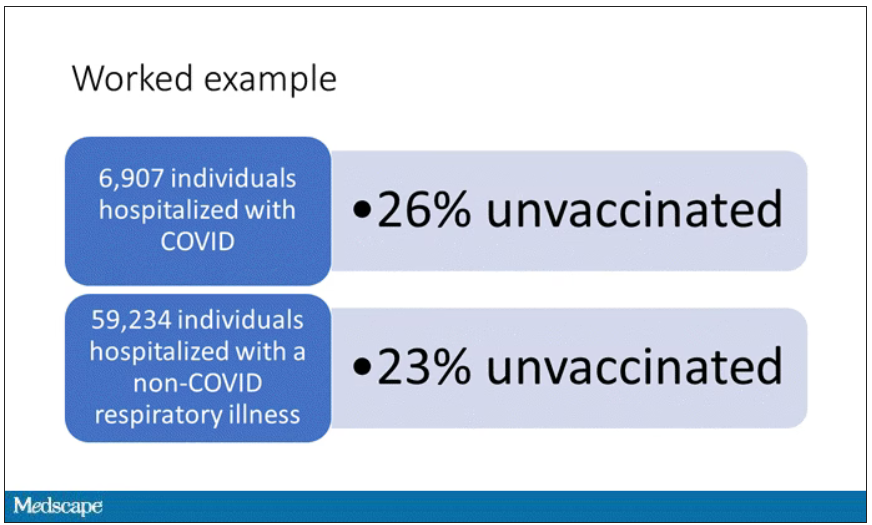

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

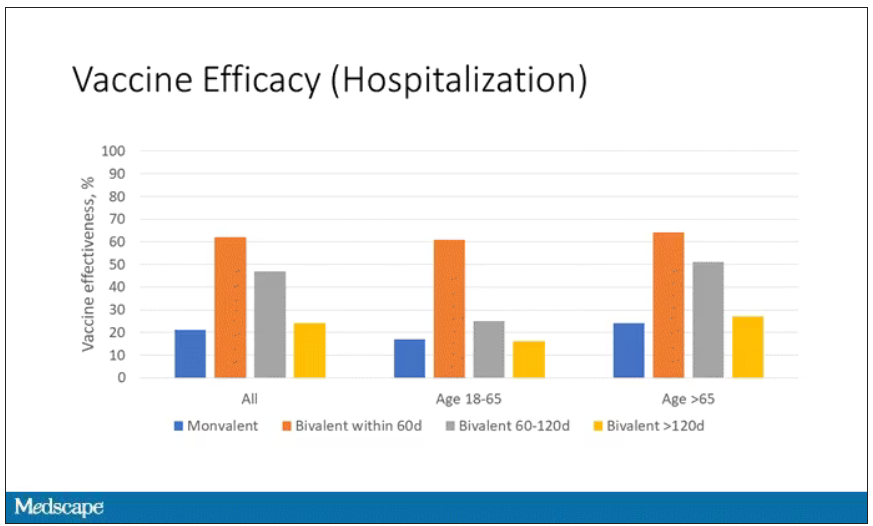

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

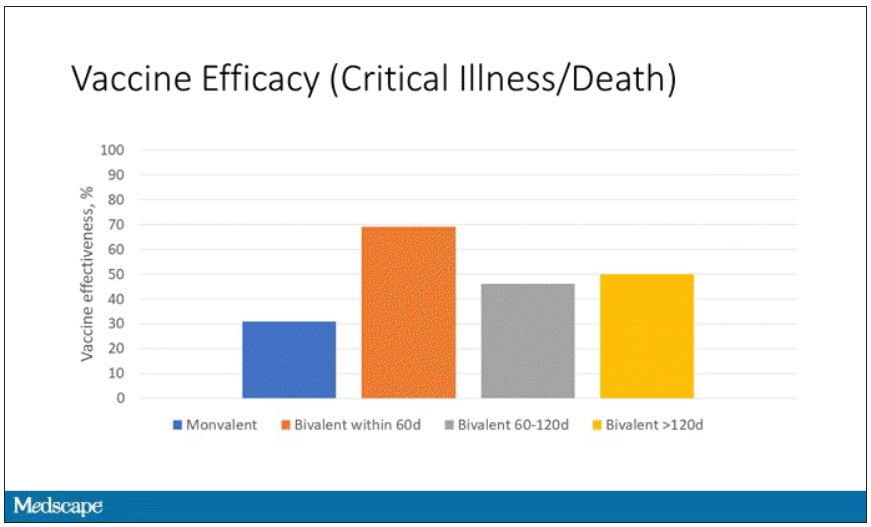

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

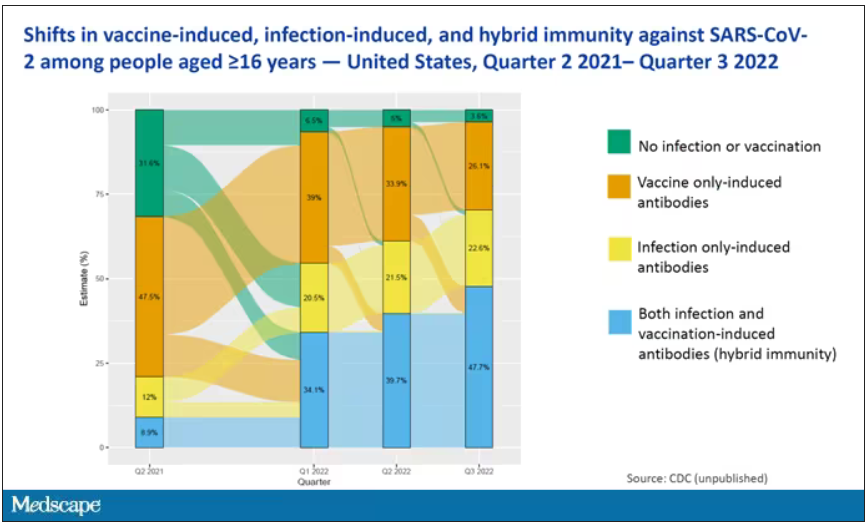

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 30th-birthday gift that could save a life

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Milestone birthdays are always memorable – those ages when your life seems to fundamentally change somehow. Age 16: A license to drive. Age 18: You can vote to determine your own future and serve in the military. At 21, 3 years after adulthood, you are finally allowed to drink alcohol, for some reason. And then ... nothing much happens. At least until you turn 65 and become eligible for Medicare.

But imagine a future when turning 30 might be the biggest milestone birthday of all. Imagine a future when, at 30, you get your genome sequenced and doctors tell you what needs to be done to save your life.

That future may not be far off, as a new study shows us that

Getting your genome sequenced is a double-edged sword. Of course, there is the potential for substantial benefit; finding certain mutations allows for definitive therapy before it’s too late. That said, there are genetic diseases without a cure and without a treatment. Knowing about that destiny may do more harm than good.

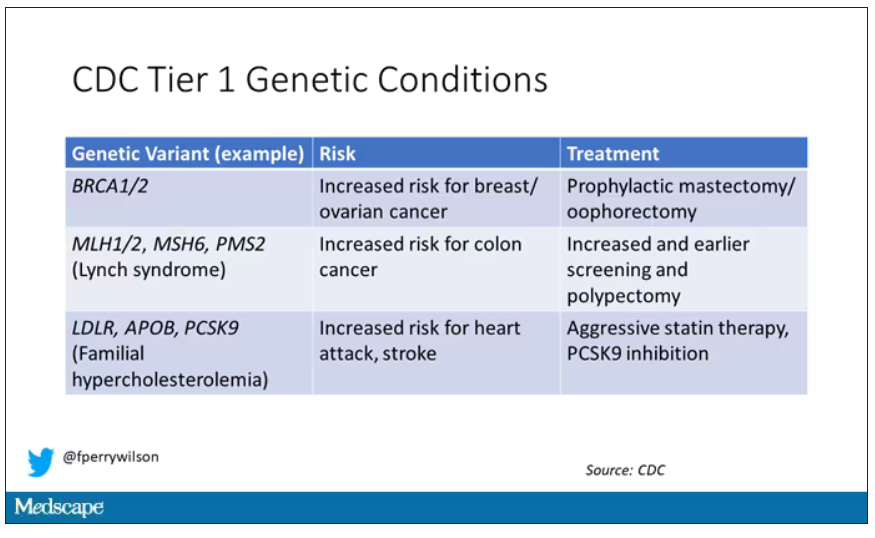

Three conditions are described by the CDC as “Tier 1” conditions, genetic syndromes with a significant impact on life expectancy that also have definitive, effective therapies.

These include mutations like BRCA1/2, associated with a high risk for breast and ovarian cancer; mutations associated with Lynch syndrome, which confer an elevated risk for colon cancer; and mutations associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, which confer elevated risk for cardiovascular events.

In each of these cases, there is clear evidence that early intervention can save lives. Individuals at high risk for breast and ovarian cancer can get prophylactic mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy. Those with Lynch syndrome can get more frequent screening for colon cancer and polypectomy, and those with familial hypercholesterolemia can get aggressive lipid-lowering therapy.

I think most of us would probably want to know if we had one of these conditions. Most of us would use that information to take concrete steps to decrease our risk. But just because a rational person would choose to do something doesn’t mean it’s feasible. After all, we’re talking about tests and treatments that have significant costs.

In a recent issue of Annals of Internal Medicine, Josh Peterson and David Veenstra present a detailed accounting of the cost and benefit of a hypothetical nationwide, universal screening program for Tier 1 conditions. And in the end, it may actually be worth it.

Cost-benefit analyses work by comparing two independent policy choices: the status quo – in this case, a world in which some people get tested for these conditions, but generally only if they are at high risk based on strong family history; and an alternative policy – in this case, universal screening for these conditions starting at some age.

After that, it’s time to play the assumption game. Using the best available data, the authors estimated the percentage of the population that will have each condition, the percentage of those individuals who will definitively act on the information, and how effective those actions would be if taken.

The authors provide an example. First, they assume that the prevalence of mutations leading to a high risk for breast and ovarian cancer is around 0.7%, and that up to 40% of people who learn that they have one of these mutations would undergo prophylactic mastectomy, which would reduce the risk for breast cancer by around 94%. (I ran these numbers past my wife, a breast surgical oncologist, who agreed that they seem reasonable.)

Assumptions in place, it’s time to consider costs. The cost of the screening test itself: The authors use $250 as their average per-person cost. But we also have the cost of treatment – around $22,000 per person for a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy; the cost of statin therapy for those with familial hypercholesterolemia; or the cost of all of those colonoscopies for those with Lynch syndrome.

Finally, we assess quality of life. Obviously, living longer is generally considered better than living shorter, but marginal increases in life expectancy at the cost of quality of life might not be a rational choice.

You then churn these assumptions through a computer and see what comes out. How many dollars does it take to save one quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)? I’ll tell you right now that $50,000 per QALY used to be the unofficial standard for a “cost-effective” intervention in the United States. Researchers have more recently used $100,000 as that threshold.

Let’s look at some hard numbers.

If you screened 100,000 people at age 30 years, 1,500 would get news that something in their genetics was, more or less, a ticking time bomb. Some would choose to get definitive treatment and the authors estimate that the strategy would prevent 85 cases of cancer. You’d prevent nine heart attacks and five strokes by lowering cholesterol levels among those with familial hypercholesterolemia. Obviously, these aren’t huge numbers, but of course most people don’t have these hereditary risk factors. For your average 30-year-old, the genetic screening test will be completely uneventful, but for those 1,500 it will be life-changing, and potentially life-saving.

But is it worth it? The authors estimate that, at the midpoint of all their assumptions, the cost of this program would be $68,000 per QALY saved.

Of course, that depends on all those assumptions we talked about. Interestingly, the single factor that changes the cost-effectiveness the most in this analysis is the cost of the genetic test itself, which I guess makes sense, considering we’d be talking about testing a huge segment of the population. If the test cost $100 instead of $250, the cost per QALY would be $39,700 – well within the range that most policymakers would support. And given the rate at which the cost of genetic testing is decreasing, and the obvious economies of scale here, I think $100 per test is totally feasible.

The future will bring other changes as well. Right now, there are only three hereditary conditions designated as Tier 1 by the CDC. If conditions are added, that might also swing the calculation more heavily toward benefit.

This will represent a stark change from how we think about genetic testing currently, focusing on those whose pretest probability of an abnormal result is high due to family history or other risk factors. But for the 20-year-olds out there, I wouldn’t be surprised if your 30th birthday is a bit more significant than you have been anticipating.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Milestone birthdays are always memorable – those ages when your life seems to fundamentally change somehow. Age 16: A license to drive. Age 18: You can vote to determine your own future and serve in the military. At 21, 3 years after adulthood, you are finally allowed to drink alcohol, for some reason. And then ... nothing much happens. At least until you turn 65 and become eligible for Medicare.

But imagine a future when turning 30 might be the biggest milestone birthday of all. Imagine a future when, at 30, you get your genome sequenced and doctors tell you what needs to be done to save your life.

That future may not be far off, as a new study shows us that

Getting your genome sequenced is a double-edged sword. Of course, there is the potential for substantial benefit; finding certain mutations allows for definitive therapy before it’s too late. That said, there are genetic diseases without a cure and without a treatment. Knowing about that destiny may do more harm than good.

Three conditions are described by the CDC as “Tier 1” conditions, genetic syndromes with a significant impact on life expectancy that also have definitive, effective therapies.

These include mutations like BRCA1/2, associated with a high risk for breast and ovarian cancer; mutations associated with Lynch syndrome, which confer an elevated risk for colon cancer; and mutations associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, which confer elevated risk for cardiovascular events.

In each of these cases, there is clear evidence that early intervention can save lives. Individuals at high risk for breast and ovarian cancer can get prophylactic mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy. Those with Lynch syndrome can get more frequent screening for colon cancer and polypectomy, and those with familial hypercholesterolemia can get aggressive lipid-lowering therapy.

I think most of us would probably want to know if we had one of these conditions. Most of us would use that information to take concrete steps to decrease our risk. But just because a rational person would choose to do something doesn’t mean it’s feasible. After all, we’re talking about tests and treatments that have significant costs.

In a recent issue of Annals of Internal Medicine, Josh Peterson and David Veenstra present a detailed accounting of the cost and benefit of a hypothetical nationwide, universal screening program for Tier 1 conditions. And in the end, it may actually be worth it.

Cost-benefit analyses work by comparing two independent policy choices: the status quo – in this case, a world in which some people get tested for these conditions, but generally only if they are at high risk based on strong family history; and an alternative policy – in this case, universal screening for these conditions starting at some age.

After that, it’s time to play the assumption game. Using the best available data, the authors estimated the percentage of the population that will have each condition, the percentage of those individuals who will definitively act on the information, and how effective those actions would be if taken.

The authors provide an example. First, they assume that the prevalence of mutations leading to a high risk for breast and ovarian cancer is around 0.7%, and that up to 40% of people who learn that they have one of these mutations would undergo prophylactic mastectomy, which would reduce the risk for breast cancer by around 94%. (I ran these numbers past my wife, a breast surgical oncologist, who agreed that they seem reasonable.)

Assumptions in place, it’s time to consider costs. The cost of the screening test itself: The authors use $250 as their average per-person cost. But we also have the cost of treatment – around $22,000 per person for a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy; the cost of statin therapy for those with familial hypercholesterolemia; or the cost of all of those colonoscopies for those with Lynch syndrome.

Finally, we assess quality of life. Obviously, living longer is generally considered better than living shorter, but marginal increases in life expectancy at the cost of quality of life might not be a rational choice.

You then churn these assumptions through a computer and see what comes out. How many dollars does it take to save one quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)? I’ll tell you right now that $50,000 per QALY used to be the unofficial standard for a “cost-effective” intervention in the United States. Researchers have more recently used $100,000 as that threshold.

Let’s look at some hard numbers.

If you screened 100,000 people at age 30 years, 1,500 would get news that something in their genetics was, more or less, a ticking time bomb. Some would choose to get definitive treatment and the authors estimate that the strategy would prevent 85 cases of cancer. You’d prevent nine heart attacks and five strokes by lowering cholesterol levels among those with familial hypercholesterolemia. Obviously, these aren’t huge numbers, but of course most people don’t have these hereditary risk factors. For your average 30-year-old, the genetic screening test will be completely uneventful, but for those 1,500 it will be life-changing, and potentially life-saving.

But is it worth it? The authors estimate that, at the midpoint of all their assumptions, the cost of this program would be $68,000 per QALY saved.

Of course, that depends on all those assumptions we talked about. Interestingly, the single factor that changes the cost-effectiveness the most in this analysis is the cost of the genetic test itself, which I guess makes sense, considering we’d be talking about testing a huge segment of the population. If the test cost $100 instead of $250, the cost per QALY would be $39,700 – well within the range that most policymakers would support. And given the rate at which the cost of genetic testing is decreasing, and the obvious economies of scale here, I think $100 per test is totally feasible.

The future will bring other changes as well. Right now, there are only three hereditary conditions designated as Tier 1 by the CDC. If conditions are added, that might also swing the calculation more heavily toward benefit.

This will represent a stark change from how we think about genetic testing currently, focusing on those whose pretest probability of an abnormal result is high due to family history or other risk factors. But for the 20-year-olds out there, I wouldn’t be surprised if your 30th birthday is a bit more significant than you have been anticipating.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Milestone birthdays are always memorable – those ages when your life seems to fundamentally change somehow. Age 16: A license to drive. Age 18: You can vote to determine your own future and serve in the military. At 21, 3 years after adulthood, you are finally allowed to drink alcohol, for some reason. And then ... nothing much happens. At least until you turn 65 and become eligible for Medicare.

But imagine a future when turning 30 might be the biggest milestone birthday of all. Imagine a future when, at 30, you get your genome sequenced and doctors tell you what needs to be done to save your life.

That future may not be far off, as a new study shows us that