User login

Defending access to reproductive health care

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

2021 Update on pelvic floor disorders

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

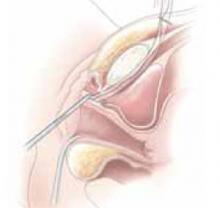

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

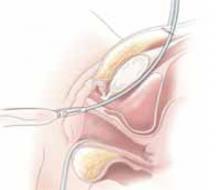

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.

Single-incision slings may reduce the risk of groin pain associated with transobturator slings and may be a good option for patients who desire less mesh burden than the traditional retropubic slings or who are not good candidates. This trial suggests that the Altis single-incision sling may be similar in outcomes and adverse events to currently available midurethral slings, but further, more rigorous trials are underway to fully evaluate this—including a US-based multicenter randomized trial of Altis single-incision slings versus retropubic slings (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03520114).

Office-based pessary care can be safely spaced out to 24 weeks without an increase in erosions

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100-105. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000003580.

For women already using a pessary without issues, extending office visits to every 6 months does not increase rates of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, according to results of this randomized controlled trial.

Study details

Women already using a Gelhorn, ring, or incontinence dish pessary for POP, SUI, or both were randomized to continue routine care with office evaluation every 12 weeks versus the extended-care cohort (with office evaluation every 24 weeks). Women were excluded if they removed and replaced the pessary themselves or if there was a presence of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, such as erosion or granulation tissue.

Results

The rate of vaginal epithelium erosion was 7.4% in the routine arm and 1.7% in the extended-care arm, meeting criteria for noninferiority of extended care. The majority of patients with office visits every 24 weeks preferred the less frequent examinations, and there was no difference in degree of bother due to vaginal discharge. There was also no difference in the percentage of patients with unscheduled visits. The only factors associated with vaginal epithelium abnormalities were prior abnormalities and lifetime duration of pessary use.

As there are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for pessary care, this study contributes data to support extended office-based care up to 24 weeks, a common practice in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced health care access, these findings should be reassuring to clinicians and patients.

Continue to: How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?...

How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?

Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:S0002-9378(21)00610-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042.

A secondary analysis of a recent systematic review found overall moderate- to high-quality evidence that were no differences in total dyspareunia, de novo dyspareunia, and scores on a validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ12) when comparing postoperative sexual function outcomes of native tissue repair to sacrocolpopexy, transvaginal mesh, or biologic graft. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia were higher for transvaginal mesh than for sacrocolpopexy.

Study details

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group identified 43 original prospective, comparative studies of reconstructive prolapse surgery that reported sexual function outcomes when comparing 2 different types of POP procedures. Thirty-seven of those studies were randomized controlled trials. Specifically, they looked at data comparing outcomes for native tissue versus sacrocolpopexy, native tissue versus transvaginal mesh, native tissue versus biologic graft, and transvaginal mesh versus sacrocolpopexy.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of postoperative dyspareunia was lower than preoperatively after all surgery types. The only statistical difference in this review demonstrated higher postoperative prevalence of dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh than sacrocolpopexy, based on 2 studies. When comparing native tissue prolapse repair to transvaginal mesh, sacrocolpopexy, or biologic grafts, there were no significant differences in sexual activity, baseline, or postoperative total dyspareunia, de-novo dyspareunia, or sexual function changes as measured by the PISQ12 validated questionnaire. ●

This systematic review further contributes to the growing evidence that, regardless of surgical approach to POP, sexual function generally improves and dyspareunia rates generally decrease postoperatively, with overall low rates of de novo dyspareunia. This will help patients and providers select the best-fit surgical approach without concern for worsened sexual function. It also underscores the need for inclusion of standardized sexual function terminology use and sexual health outcomes in future prolapse surgery research.

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.

Single-incision slings may reduce the risk of groin pain associated with transobturator slings and may be a good option for patients who desire less mesh burden than the traditional retropubic slings or who are not good candidates. This trial suggests that the Altis single-incision sling may be similar in outcomes and adverse events to currently available midurethral slings, but further, more rigorous trials are underway to fully evaluate this—including a US-based multicenter randomized trial of Altis single-incision slings versus retropubic slings (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03520114).

Office-based pessary care can be safely spaced out to 24 weeks without an increase in erosions

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100-105. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000003580.

For women already using a pessary without issues, extending office visits to every 6 months does not increase rates of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, according to results of this randomized controlled trial.

Study details

Women already using a Gelhorn, ring, or incontinence dish pessary for POP, SUI, or both were randomized to continue routine care with office evaluation every 12 weeks versus the extended-care cohort (with office evaluation every 24 weeks). Women were excluded if they removed and replaced the pessary themselves or if there was a presence of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, such as erosion or granulation tissue.

Results

The rate of vaginal epithelium erosion was 7.4% in the routine arm and 1.7% in the extended-care arm, meeting criteria for noninferiority of extended care. The majority of patients with office visits every 24 weeks preferred the less frequent examinations, and there was no difference in degree of bother due to vaginal discharge. There was also no difference in the percentage of patients with unscheduled visits. The only factors associated with vaginal epithelium abnormalities were prior abnormalities and lifetime duration of pessary use.

As there are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for pessary care, this study contributes data to support extended office-based care up to 24 weeks, a common practice in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced health care access, these findings should be reassuring to clinicians and patients.

Continue to: How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?...

How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?

Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:S0002-9378(21)00610-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042.

A secondary analysis of a recent systematic review found overall moderate- to high-quality evidence that were no differences in total dyspareunia, de novo dyspareunia, and scores on a validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ12) when comparing postoperative sexual function outcomes of native tissue repair to sacrocolpopexy, transvaginal mesh, or biologic graft. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia were higher for transvaginal mesh than for sacrocolpopexy.

Study details

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group identified 43 original prospective, comparative studies of reconstructive prolapse surgery that reported sexual function outcomes when comparing 2 different types of POP procedures. Thirty-seven of those studies were randomized controlled trials. Specifically, they looked at data comparing outcomes for native tissue versus sacrocolpopexy, native tissue versus transvaginal mesh, native tissue versus biologic graft, and transvaginal mesh versus sacrocolpopexy.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of postoperative dyspareunia was lower than preoperatively after all surgery types. The only statistical difference in this review demonstrated higher postoperative prevalence of dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh than sacrocolpopexy, based on 2 studies. When comparing native tissue prolapse repair to transvaginal mesh, sacrocolpopexy, or biologic grafts, there were no significant differences in sexual activity, baseline, or postoperative total dyspareunia, de-novo dyspareunia, or sexual function changes as measured by the PISQ12 validated questionnaire. ●

This systematic review further contributes to the growing evidence that, regardless of surgical approach to POP, sexual function generally improves and dyspareunia rates generally decrease postoperatively, with overall low rates of de novo dyspareunia. This will help patients and providers select the best-fit surgical approach without concern for worsened sexual function. It also underscores the need for inclusion of standardized sexual function terminology use and sexual health outcomes in future prolapse surgery research.

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.

Single-incision slings may reduce the risk of groin pain associated with transobturator slings and may be a good option for patients who desire less mesh burden than the traditional retropubic slings or who are not good candidates. This trial suggests that the Altis single-incision sling may be similar in outcomes and adverse events to currently available midurethral slings, but further, more rigorous trials are underway to fully evaluate this—including a US-based multicenter randomized trial of Altis single-incision slings versus retropubic slings (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03520114).

Office-based pessary care can be safely spaced out to 24 weeks without an increase in erosions

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100-105. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000003580.

For women already using a pessary without issues, extending office visits to every 6 months does not increase rates of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, according to results of this randomized controlled trial.

Study details

Women already using a Gelhorn, ring, or incontinence dish pessary for POP, SUI, or both were randomized to continue routine care with office evaluation every 12 weeks versus the extended-care cohort (with office evaluation every 24 weeks). Women were excluded if they removed and replaced the pessary themselves or if there was a presence of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, such as erosion or granulation tissue.

Results

The rate of vaginal epithelium erosion was 7.4% in the routine arm and 1.7% in the extended-care arm, meeting criteria for noninferiority of extended care. The majority of patients with office visits every 24 weeks preferred the less frequent examinations, and there was no difference in degree of bother due to vaginal discharge. There was also no difference in the percentage of patients with unscheduled visits. The only factors associated with vaginal epithelium abnormalities were prior abnormalities and lifetime duration of pessary use.

As there are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for pessary care, this study contributes data to support extended office-based care up to 24 weeks, a common practice in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced health care access, these findings should be reassuring to clinicians and patients.

Continue to: How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?...

How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?

Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:S0002-9378(21)00610-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042.

A secondary analysis of a recent systematic review found overall moderate- to high-quality evidence that were no differences in total dyspareunia, de novo dyspareunia, and scores on a validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ12) when comparing postoperative sexual function outcomes of native tissue repair to sacrocolpopexy, transvaginal mesh, or biologic graft. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia were higher for transvaginal mesh than for sacrocolpopexy.

Study details

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group identified 43 original prospective, comparative studies of reconstructive prolapse surgery that reported sexual function outcomes when comparing 2 different types of POP procedures. Thirty-seven of those studies were randomized controlled trials. Specifically, they looked at data comparing outcomes for native tissue versus sacrocolpopexy, native tissue versus transvaginal mesh, native tissue versus biologic graft, and transvaginal mesh versus sacrocolpopexy.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of postoperative dyspareunia was lower than preoperatively after all surgery types. The only statistical difference in this review demonstrated higher postoperative prevalence of dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh than sacrocolpopexy, based on 2 studies. When comparing native tissue prolapse repair to transvaginal mesh, sacrocolpopexy, or biologic grafts, there were no significant differences in sexual activity, baseline, or postoperative total dyspareunia, de-novo dyspareunia, or sexual function changes as measured by the PISQ12 validated questionnaire. ●

This systematic review further contributes to the growing evidence that, regardless of surgical approach to POP, sexual function generally improves and dyspareunia rates generally decrease postoperatively, with overall low rates of de novo dyspareunia. This will help patients and providers select the best-fit surgical approach without concern for worsened sexual function. It also underscores the need for inclusion of standardized sexual function terminology use and sexual health outcomes in future prolapse surgery research.

How to choose the right vaginal moisturizer or lubricant for your patient

Vaginal dryness, encompassed in the modern term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects up to 40% of menopausal women and up to 60% of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors.1,2 Premenopausal women also can have vulvovaginal dryness while breastfeeding (lactational amenorrhea) and while taking low-dose contraceptives.3 Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants are the first-line treatment options for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and GSM.4,5 In fact, approximately two-thirds of women have reported using a vaginal lubricant in their lifetime.6 Despite such ubiquitous use, many health care providers and patients have questions about the difference between vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and how to best choose a product.

Vaginal moisturizers

Vaginal moisturizers are designed to rehydrate the vaginal epithelium. Much like facial or skin moisturizers, they are intended to be applied regularly, every 2 to 3 days, but may be applied more often depending on the severity of symptoms. Vaginal moisturizers work by increasing the fluid content of the vaginal tissue and by lowering the vaginal pH to mimic that of natural vaginal secretions. Vaginal moisturizers are typically water based and use polymers to hydrate tissues.7 They change cell morphology but do not change vaginal maturation, indicating that they bring water to the tissue but do not shift the balance between superficial and basal cells and do not increase vaginal epithelial thickness as seen with vaginal estrogen.8 Vaginal moisturizers also have been found to be a safe alternative to vaginal estrogen therapy and may improve markers of vaginal health, including vaginal moisture, vaginal fluid volume, vaginal elasticity, and premenopausal pH.9 Commercially available vaginal moisturizers have been shown to be as effective as vaginal estrogens in reducing vaginal symptoms such as itching, irritation, and dyspareunia, but some caution should be taken when interpreting these results as neither vaginal moisturizer nor vaginal estrogen tablet were more effective than placebo in a recent randomized controlled trial.10,11 Small studies on hyaluronic acid have shown efficacy for the treatment of vaginal dryness.12,13 Hyaluronic acid is commercially available as a vaginal suppository ovule and as a liquid. It may also be obtained from a reliable compounding pharmacy. Vaginal suppository ovules may be a preferable formulation for women who find the liquids messy or cumbersome to apply.

Lubricants

Lubricants differ from vaginal moisturizers because they are specifically designed to be used during intercourse to provide short-term relief from vaginal dryness. They may be water-, silicone-, mineral oil-, or plant oil-based. The use of water- and silicone-based lubricants is associated with high satisfaction for intercourse as well as masturbation.14 These products may be particularly beneficial to women whose chief complaint is dyspareunia. In fact, women with dyspareunia report more lubricant use than women without dyspareunia, and the most common reason for lubricant use among these women was to reduce or alleviate pain.15 Overall, women both with and without dyspareunia have a positive perception regarding lubricant use and prefer sexual intercourse that feels more “wet,” and women in their forties have the most positive perception about lubricant use at the time of intercourse compared with other age groups.16 Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that condom-compatible lubricants be used with condoms for menopausal and postmenopausal women.17 Both water-based and silicone-based lubricants may be used with latex condoms, while oil-based lubricants should be avoided as they can degrade the latex condom. While vaginal moisturizers and lubricants technically differ based on use, patients may use one product for both purposes, and some products are marketed as both a moisturizer and lubricant.

Continue to: Providing counsel to patients...

Providing counsel to patients

Patients often seek advice on how to choose vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. Understanding the compositions of these products and their scientific evidence is useful when helping patients make informed decisions regarding their pelvic health. Most commercially available lubricants are either water- or silicone- based. In one study comparing these two types of lubricants, water-based lubricants were associated with fewer genital symptoms than silicone-based products.14 Women may want to use a natural or organic product and may prefer plant-based oils such as coconut oil or olive oil. Patients should be counseled that latex condoms are not compatible with petroleum-, mineral oil- or plant oil-based lubricants.

In our practice, we generally recommend silicone-based lubricants, as they are readily available and compatible with latex condoms and generally require a smaller amount than water-based lubricants. They tend to be more expensive than water-based lubricants. For vaginal moisturizers, we often recommend commercially available formulations that can be purchased at local pharmacies or drug stores. However, a patient may need to try different lubricants and moisturizers in order to find a preferred product. We have included in TABLES 1 and 27,17,18 a list of commercially available vaginal moisturizers and lubricants with ingredient list, pH, osmolality, common formulation, and cost when available, which has been compiled from WHO and published research data to help guide patient counseling.

The effects of additives

Water-based moisturizers and lubricants may contain many ingredients, such as glycerols, fragrance, flavors, sweeteners, warming or cooling agents, buffering solutions, parabens and other preservatives, and numbing agents. These substances are added to water-based products to prolong water content, alter viscosity, alter pH, achieve certain sensations, and prevent bacterial contamination.7 The addition of these substances, however, will alter osmolality and pH balance of the product, which may be of clinical consequence. Silicone- or oil-based products do not contain water and therefore do not have a pH or an osmolality value.

Hyperosmolar formulations can theoretically injure epithelial tissue. In vitro studies have shown that hyperosmotic vaginal products can induce mild to moderate irritation, while very hyperosmolar formulations can induce severe irritation and tissue damage to vaginal epithelial and cervical cells.19,20 The WHO recommends that the osmolality of a vaginal product not exceed 380 mOsm/kg, but very few commercially available products meet these criteria so, clinically, the threshold is 1,200 mOsm/kg.17 It should be noted that most commercially available products exceed the 1,200 mOsm/kg threshold. Vaginal products may be a cause for vaginal irritation and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

The normal vaginal pH is 3.8–4.5, and vaginal products should be pH balanced to this range. The exact role of pH in these products remains poorly understood. Nonetheless, products with a pH of 3 or lower are not recommended.18 Concerns about osmolality and pH remain theoretical, as a study of 12 commercially available lubricants of varying osmolality and pH found no cytotoxic effect in vivo.18

Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants contain many inactive ingredients, the most controversial of which are parabens. These substances are used in many cosmetic products as preservatives and are weakly estrogenic. These substances have been found in breast cancer tissue, but their possible role as a carcinogen remains uncertain.21,22 Nonetheless, the use of paraben-containing products is not recommended for women who have a history of hormonally-driven cancer or who are at high risk for developing cancer.7 Many lubricants contain glycerols (glycerol, glycerine, and propylene glycol) to alter viscosity or alter the water properties. The WHO recommends limits on the content of glycerols in these products.17 Glycerols have been associated with increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 11.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.96–70.27), and can serve as a food source for candida species, possibly increasing risk of yeast infections.7,23 Additionally, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants may contain preservatives such as chlorhexidine, which can disrupt normal vaginal flora and may cause tissue irritation.7

Continue to: Common concerns to be aware of...

Common concerns to be aware of

Women using vaginal products may be concerned about adverse effects, such as worsening vaginal irritation or infection. Vaginal moisturizers have not been shown to have increased risk of adverse effects compared with vaginal estrogens.9,10 In vitro studies have shown that vaginal moisturizers and lubricants inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli but may also inhibit Lactobacillus crispatus.24 Clinically, vaginal moisturizers have been shown to improve signs of bacterial vaginosis and have even been used to treat bacterial vaginosis.25,26 A study of commercially available vaginal lubricants inhibited the growth of L crispatus, which may predispose to irritation and infection.27 Nonetheless, the effect of the vaginal products on the vaginal microbiome and vaginal tissue remains poorly studied. Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, while often helpful for patients, also can potentially cause irritation or predispose to infections. Providers should consider this when evaluating patients for new onset vaginal symptoms after starting vaginal products.

Bottom line

Vaginal products such as moisturizers and lubricants are often effective treatment options for women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause and may be first-line treatment options, especially for women who may wish to avoid estrogen-containing products. Vaginal moisturizers can be recommended to any women experiencing vaginal irritation due to vaginal dryness while vaginal lubricants should be recommended to sexually active women who experience dyspareunia. Clinicians need to be aware of the formulations of these products and possible side effects in order to appropriately counsel patients. ●

- Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, et al. Management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas. 2005;52(suppl 1):S46-S52. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.06.014.

- Crandall C, Peterson L, Ganz PA, et al. Association of breast cancer and its therapy with menopause-related symptoms. Menopause. 2004;11:519-530. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000117061.40493.ab.

- Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistant Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13:607-612. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000441353.20693.78.

- Faubion S, Larkin L, Stuenkel C, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendation from The North American Menopause Society and the International Society for the Study for Women’s Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25:596-608. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001121.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Women’s use and perceptions of commercial lubricants: prevalence and characteristics in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Med. 2014;11:642-652. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12427.

- Edwards D, Panay N. Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric. 2016;19:151-116. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1124259.

- Van der Lakk JAWN, de Bie LMT, de Leeuw H, et al. The effect of Replens on vaginal cytology in the treatment of postmenopausal atrophy: cytomorphology versus computerized cytometry. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:446-451. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.6.446.

- Nachtigall LE. Comparitive study: Replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:178-180. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56474-7.

- Bygdeman M, Swahn ML. Replens versus dienoestrol cream in the symptomatic treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23:259-263. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00955-8.

- Mitchell CM, Reed SD, Diem S, et al. Efficacy of vaginal estradiol or vaginal moisturizer vs placebo for treating postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:681-690. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0116.

- Chen J, Geng L, Song X, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid vaginal gel to ease vaginal dryness: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trial. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1575-1584. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12125.

- Jokar A, Davari T, Asadi N, et al. Comparison of the hyaluronic acid vaginal cream and conjugated estrogen used in treatment of vaginal atrophy of menopause women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. IJCBNM. 2016;4:69-78.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Hensel D, et al. Association of lubricant use with women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and genital symptoms: a prospective daily diary study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:202-212. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02067.x.

- Sutton KS, Boyer SC, Goldfinger C, et al. To lube or not to lube: experiences and perceptions of lubricant use in women with and without dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2012;9:240-250. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02543.x.

- Jozkowski KN, Herbenick D, Schick V, et al. Women’s perceptions about lubricant use and vaginal wetness during sexual activity. J Sex Med. 2013;10:484-492. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12022.

- World Health Organization. Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO /UNFPA/FHI360 advisory note. 2012. https://www.who. int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/rhr12_33/en/. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- Cunha AR, Machado RM, Palmeira de Oliveira A, et al. Characterization of commercially available vaginal lubricants: a safety perspective. Pharmaceuticals. 2014;6:530-542. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics6030530.

- Adriaens E, Remon JP. Mucosal irritation potential of personal lubricants relates to product osmolality as detected by the slug mucosal irritation assay. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:512-516. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644669.

- Dezzuti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048328.

- Harvey PW, Everett DJ. Significance of the detection of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens) in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004:24:1-4. doi: 10.1002/jat.957.

- Darbre PD, Alijarrah A, Miller WR, et al. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumous. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5-13. doi: 10.1002/jat.958.

- Brotman RM, Ravel J, Cone RA, et al. Rapid fluctuation of the vaginal microbiota measured by Gram stain analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:297-302. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.040592.

- Hung KJ, Hudson P, Bergerat A, et al. Effect of commercial vaginal products on the growth of uropathogenic and commensal vaginal bacteria. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7625.

- Wu JP, Fielding SL, Fiscell K. The effect of the polycarbophil gel (Replens) on bacterial vaginosis: a pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;130:132-136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.01.007.

- Fiorelli A, Molteni B, Milani M. Successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis with a polycarbophil-carbopol acidic vaginal gel: results from a randomized double-bling, placebo controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:202-205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.10.011.

- Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, et al. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v24i0.19703.

Vaginal dryness, encompassed in the modern term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects up to 40% of menopausal women and up to 60% of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors.1,2 Premenopausal women also can have vulvovaginal dryness while breastfeeding (lactational amenorrhea) and while taking low-dose contraceptives.3 Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants are the first-line treatment options for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and GSM.4,5 In fact, approximately two-thirds of women have reported using a vaginal lubricant in their lifetime.6 Despite such ubiquitous use, many health care providers and patients have questions about the difference between vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and how to best choose a product.

Vaginal moisturizers

Vaginal moisturizers are designed to rehydrate the vaginal epithelium. Much like facial or skin moisturizers, they are intended to be applied regularly, every 2 to 3 days, but may be applied more often depending on the severity of symptoms. Vaginal moisturizers work by increasing the fluid content of the vaginal tissue and by lowering the vaginal pH to mimic that of natural vaginal secretions. Vaginal moisturizers are typically water based and use polymers to hydrate tissues.7 They change cell morphology but do not change vaginal maturation, indicating that they bring water to the tissue but do not shift the balance between superficial and basal cells and do not increase vaginal epithelial thickness as seen with vaginal estrogen.8 Vaginal moisturizers also have been found to be a safe alternative to vaginal estrogen therapy and may improve markers of vaginal health, including vaginal moisture, vaginal fluid volume, vaginal elasticity, and premenopausal pH.9 Commercially available vaginal moisturizers have been shown to be as effective as vaginal estrogens in reducing vaginal symptoms such as itching, irritation, and dyspareunia, but some caution should be taken when interpreting these results as neither vaginal moisturizer nor vaginal estrogen tablet were more effective than placebo in a recent randomized controlled trial.10,11 Small studies on hyaluronic acid have shown efficacy for the treatment of vaginal dryness.12,13 Hyaluronic acid is commercially available as a vaginal suppository ovule and as a liquid. It may also be obtained from a reliable compounding pharmacy. Vaginal suppository ovules may be a preferable formulation for women who find the liquids messy or cumbersome to apply.

Lubricants

Lubricants differ from vaginal moisturizers because they are specifically designed to be used during intercourse to provide short-term relief from vaginal dryness. They may be water-, silicone-, mineral oil-, or plant oil-based. The use of water- and silicone-based lubricants is associated with high satisfaction for intercourse as well as masturbation.14 These products may be particularly beneficial to women whose chief complaint is dyspareunia. In fact, women with dyspareunia report more lubricant use than women without dyspareunia, and the most common reason for lubricant use among these women was to reduce or alleviate pain.15 Overall, women both with and without dyspareunia have a positive perception regarding lubricant use and prefer sexual intercourse that feels more “wet,” and women in their forties have the most positive perception about lubricant use at the time of intercourse compared with other age groups.16 Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that condom-compatible lubricants be used with condoms for menopausal and postmenopausal women.17 Both water-based and silicone-based lubricants may be used with latex condoms, while oil-based lubricants should be avoided as they can degrade the latex condom. While vaginal moisturizers and lubricants technically differ based on use, patients may use one product for both purposes, and some products are marketed as both a moisturizer and lubricant.

Continue to: Providing counsel to patients...

Providing counsel to patients

Patients often seek advice on how to choose vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. Understanding the compositions of these products and their scientific evidence is useful when helping patients make informed decisions regarding their pelvic health. Most commercially available lubricants are either water- or silicone- based. In one study comparing these two types of lubricants, water-based lubricants were associated with fewer genital symptoms than silicone-based products.14 Women may want to use a natural or organic product and may prefer plant-based oils such as coconut oil or olive oil. Patients should be counseled that latex condoms are not compatible with petroleum-, mineral oil- or plant oil-based lubricants.

In our practice, we generally recommend silicone-based lubricants, as they are readily available and compatible with latex condoms and generally require a smaller amount than water-based lubricants. They tend to be more expensive than water-based lubricants. For vaginal moisturizers, we often recommend commercially available formulations that can be purchased at local pharmacies or drug stores. However, a patient may need to try different lubricants and moisturizers in order to find a preferred product. We have included in TABLES 1 and 27,17,18 a list of commercially available vaginal moisturizers and lubricants with ingredient list, pH, osmolality, common formulation, and cost when available, which has been compiled from WHO and published research data to help guide patient counseling.

The effects of additives

Water-based moisturizers and lubricants may contain many ingredients, such as glycerols, fragrance, flavors, sweeteners, warming or cooling agents, buffering solutions, parabens and other preservatives, and numbing agents. These substances are added to water-based products to prolong water content, alter viscosity, alter pH, achieve certain sensations, and prevent bacterial contamination.7 The addition of these substances, however, will alter osmolality and pH balance of the product, which may be of clinical consequence. Silicone- or oil-based products do not contain water and therefore do not have a pH or an osmolality value.

Hyperosmolar formulations can theoretically injure epithelial tissue. In vitro studies have shown that hyperosmotic vaginal products can induce mild to moderate irritation, while very hyperosmolar formulations can induce severe irritation and tissue damage to vaginal epithelial and cervical cells.19,20 The WHO recommends that the osmolality of a vaginal product not exceed 380 mOsm/kg, but very few commercially available products meet these criteria so, clinically, the threshold is 1,200 mOsm/kg.17 It should be noted that most commercially available products exceed the 1,200 mOsm/kg threshold. Vaginal products may be a cause for vaginal irritation and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

The normal vaginal pH is 3.8–4.5, and vaginal products should be pH balanced to this range. The exact role of pH in these products remains poorly understood. Nonetheless, products with a pH of 3 or lower are not recommended.18 Concerns about osmolality and pH remain theoretical, as a study of 12 commercially available lubricants of varying osmolality and pH found no cytotoxic effect in vivo.18

Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants contain many inactive ingredients, the most controversial of which are parabens. These substances are used in many cosmetic products as preservatives and are weakly estrogenic. These substances have been found in breast cancer tissue, but their possible role as a carcinogen remains uncertain.21,22 Nonetheless, the use of paraben-containing products is not recommended for women who have a history of hormonally-driven cancer or who are at high risk for developing cancer.7 Many lubricants contain glycerols (glycerol, glycerine, and propylene glycol) to alter viscosity or alter the water properties. The WHO recommends limits on the content of glycerols in these products.17 Glycerols have been associated with increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 11.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.96–70.27), and can serve as a food source for candida species, possibly increasing risk of yeast infections.7,23 Additionally, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants may contain preservatives such as chlorhexidine, which can disrupt normal vaginal flora and may cause tissue irritation.7

Continue to: Common concerns to be aware of...

Common concerns to be aware of

Women using vaginal products may be concerned about adverse effects, such as worsening vaginal irritation or infection. Vaginal moisturizers have not been shown to have increased risk of adverse effects compared with vaginal estrogens.9,10 In vitro studies have shown that vaginal moisturizers and lubricants inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli but may also inhibit Lactobacillus crispatus.24 Clinically, vaginal moisturizers have been shown to improve signs of bacterial vaginosis and have even been used to treat bacterial vaginosis.25,26 A study of commercially available vaginal lubricants inhibited the growth of L crispatus, which may predispose to irritation and infection.27 Nonetheless, the effect of the vaginal products on the vaginal microbiome and vaginal tissue remains poorly studied. Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, while often helpful for patients, also can potentially cause irritation or predispose to infections. Providers should consider this when evaluating patients for new onset vaginal symptoms after starting vaginal products.

Bottom line

Vaginal products such as moisturizers and lubricants are often effective treatment options for women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause and may be first-line treatment options, especially for women who may wish to avoid estrogen-containing products. Vaginal moisturizers can be recommended to any women experiencing vaginal irritation due to vaginal dryness while vaginal lubricants should be recommended to sexually active women who experience dyspareunia. Clinicians need to be aware of the formulations of these products and possible side effects in order to appropriately counsel patients. ●

Vaginal dryness, encompassed in the modern term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects up to 40% of menopausal women and up to 60% of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors.1,2 Premenopausal women also can have vulvovaginal dryness while breastfeeding (lactational amenorrhea) and while taking low-dose contraceptives.3 Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants are the first-line treatment options for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and GSM.4,5 In fact, approximately two-thirds of women have reported using a vaginal lubricant in their lifetime.6 Despite such ubiquitous use, many health care providers and patients have questions about the difference between vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and how to best choose a product.

Vaginal moisturizers

Vaginal moisturizers are designed to rehydrate the vaginal epithelium. Much like facial or skin moisturizers, they are intended to be applied regularly, every 2 to 3 days, but may be applied more often depending on the severity of symptoms. Vaginal moisturizers work by increasing the fluid content of the vaginal tissue and by lowering the vaginal pH to mimic that of natural vaginal secretions. Vaginal moisturizers are typically water based and use polymers to hydrate tissues.7 They change cell morphology but do not change vaginal maturation, indicating that they bring water to the tissue but do not shift the balance between superficial and basal cells and do not increase vaginal epithelial thickness as seen with vaginal estrogen.8 Vaginal moisturizers also have been found to be a safe alternative to vaginal estrogen therapy and may improve markers of vaginal health, including vaginal moisture, vaginal fluid volume, vaginal elasticity, and premenopausal pH.9 Commercially available vaginal moisturizers have been shown to be as effective as vaginal estrogens in reducing vaginal symptoms such as itching, irritation, and dyspareunia, but some caution should be taken when interpreting these results as neither vaginal moisturizer nor vaginal estrogen tablet were more effective than placebo in a recent randomized controlled trial.10,11 Small studies on hyaluronic acid have shown efficacy for the treatment of vaginal dryness.12,13 Hyaluronic acid is commercially available as a vaginal suppository ovule and as a liquid. It may also be obtained from a reliable compounding pharmacy. Vaginal suppository ovules may be a preferable formulation for women who find the liquids messy or cumbersome to apply.

Lubricants