User login

Reversible Cutaneous Side Effects of Vismodegib Treatment

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

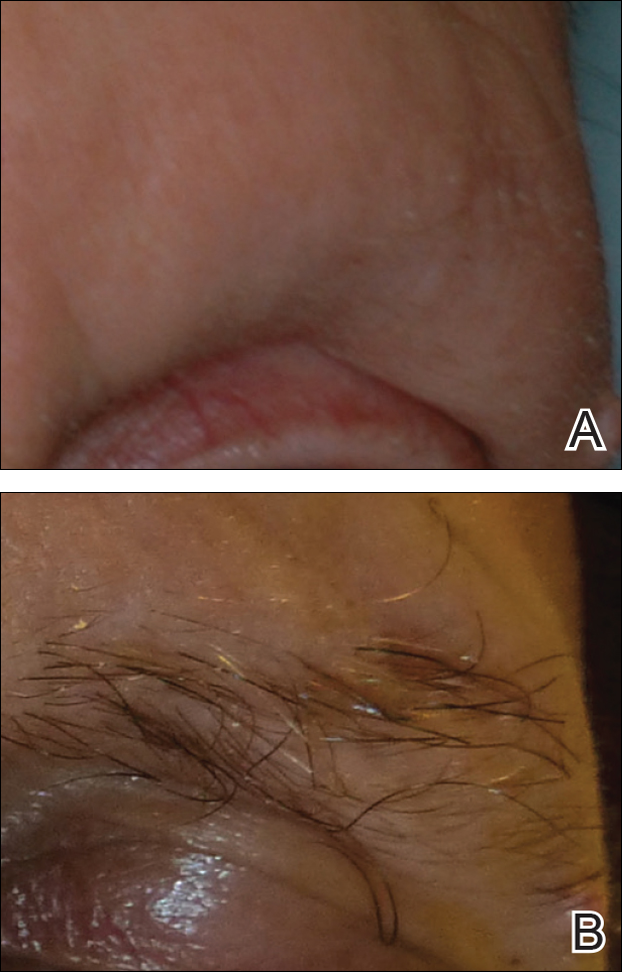

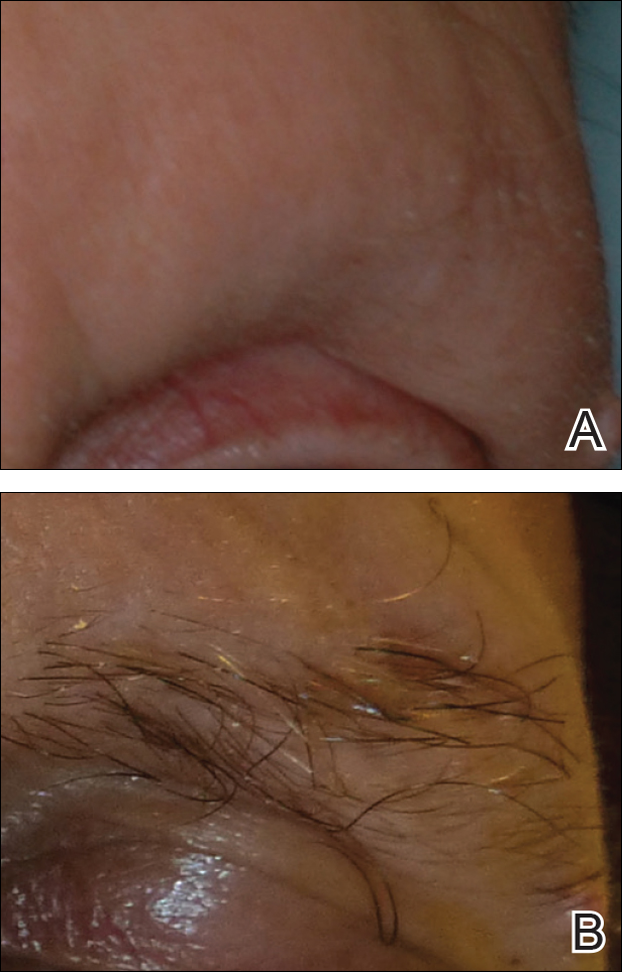

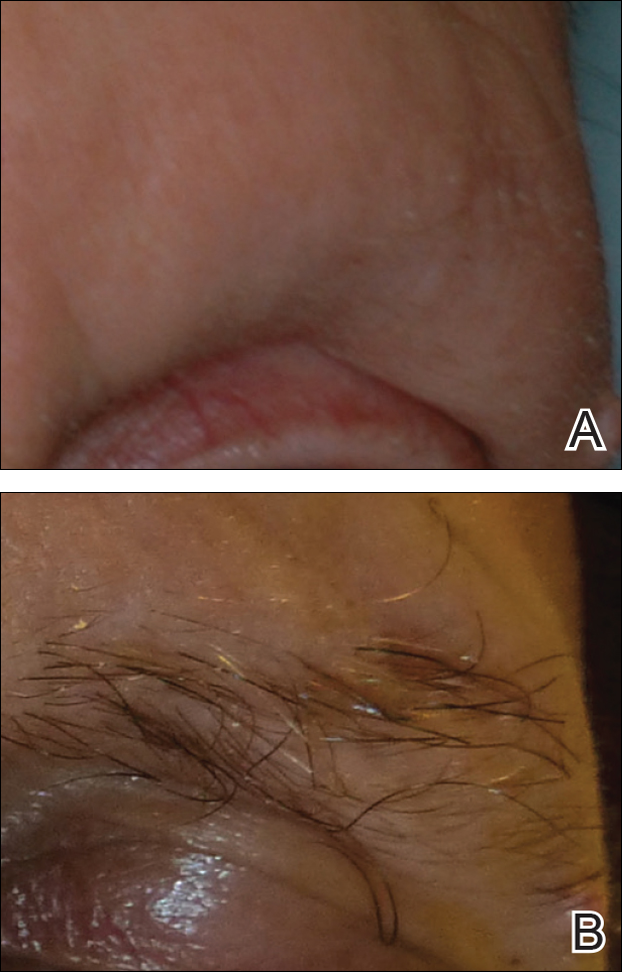

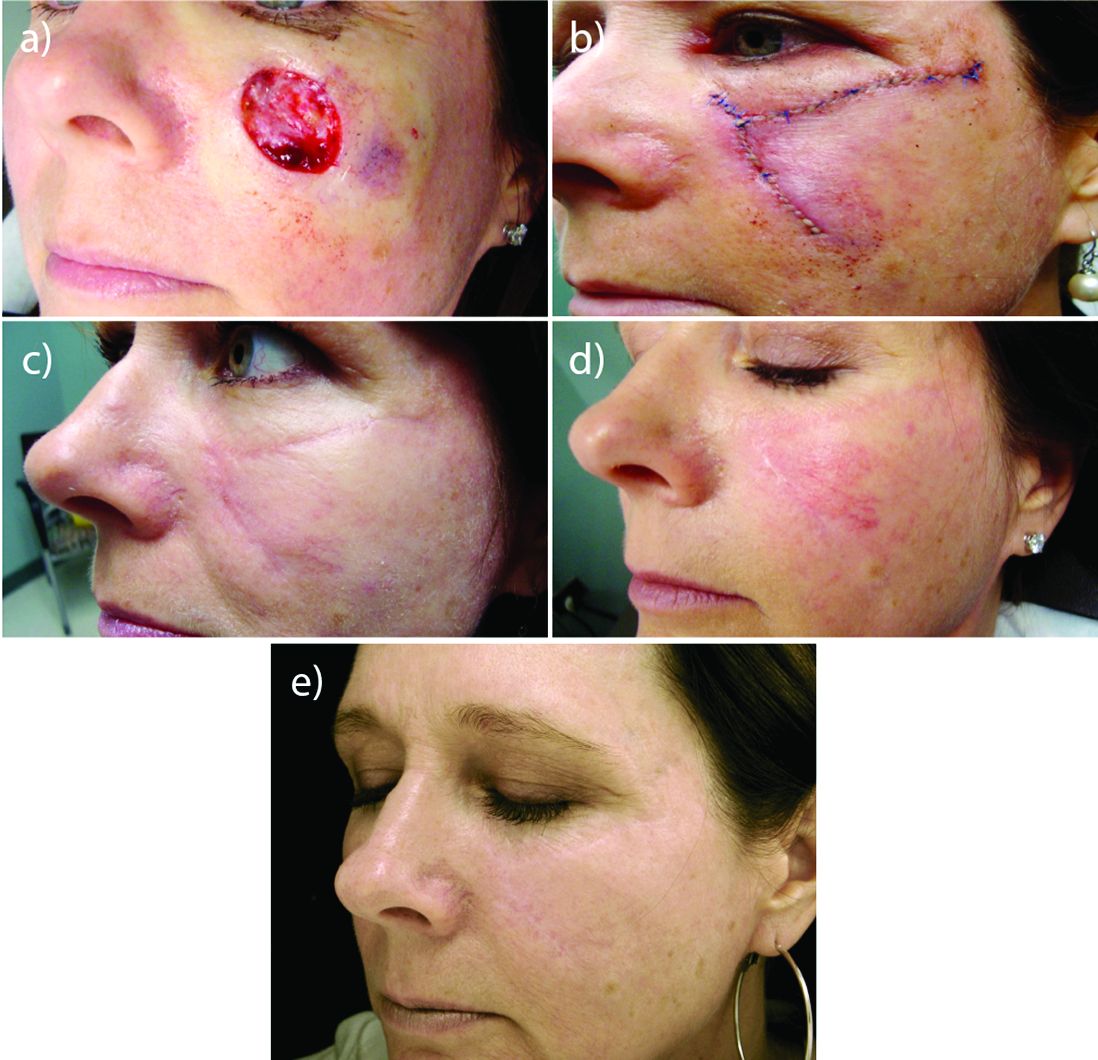

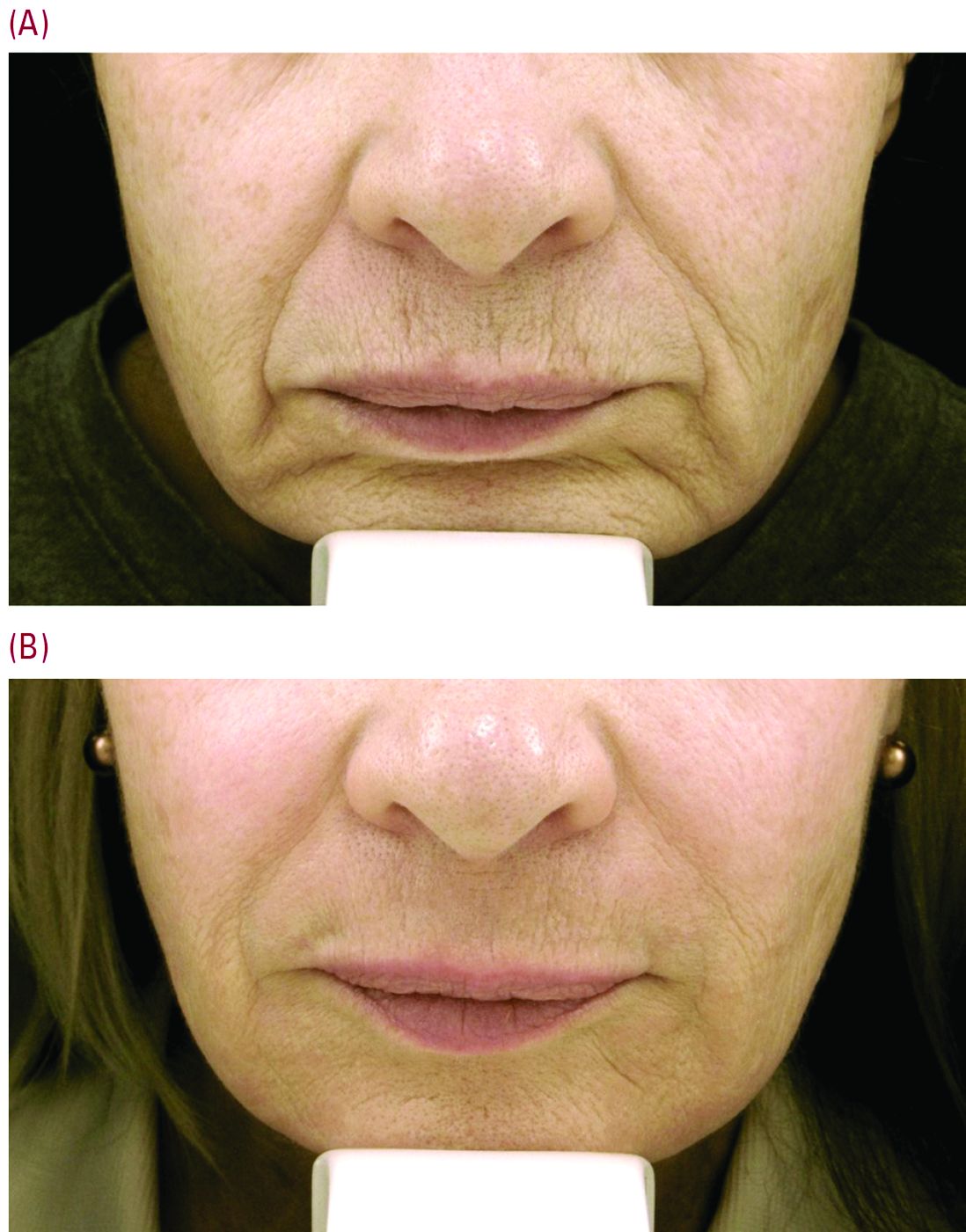

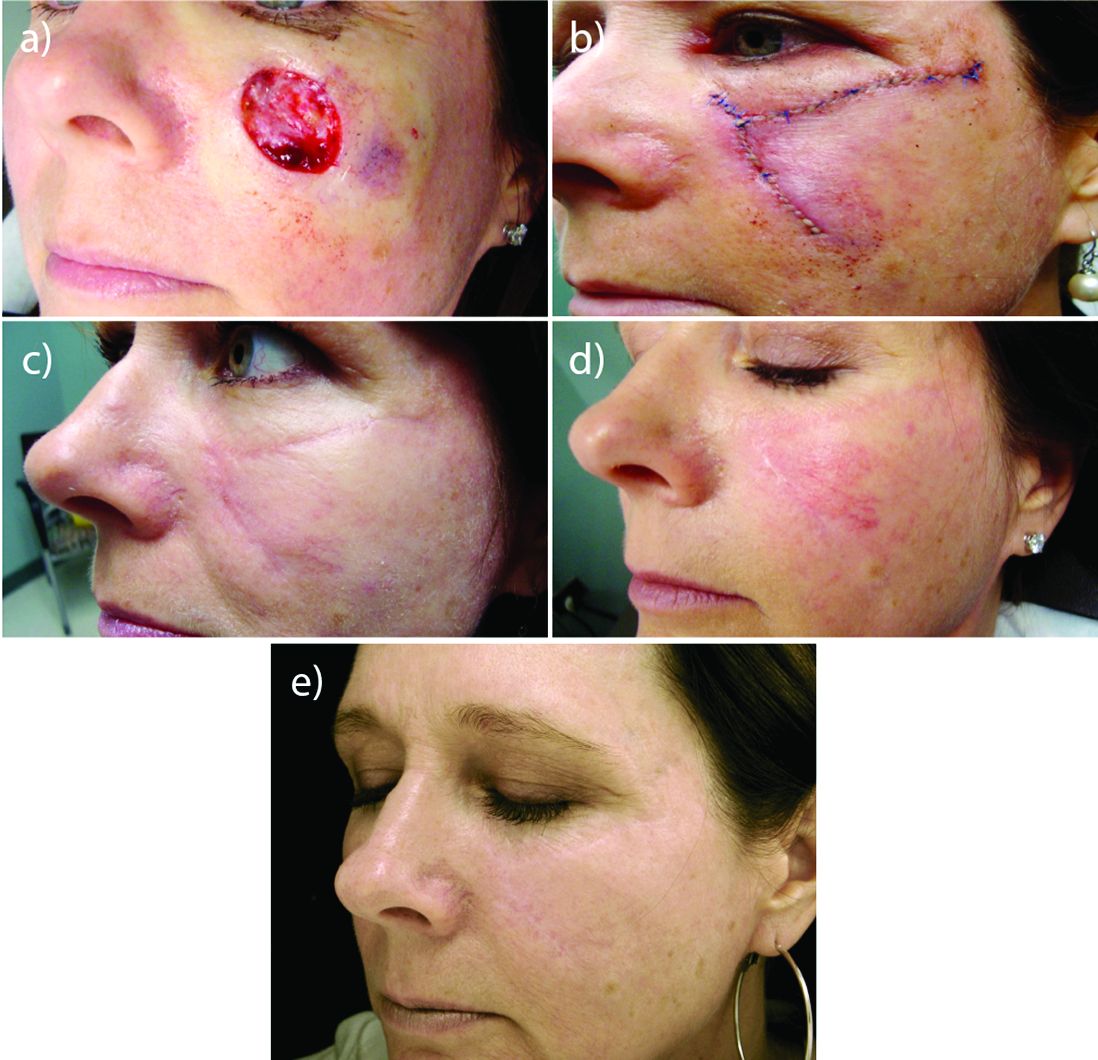

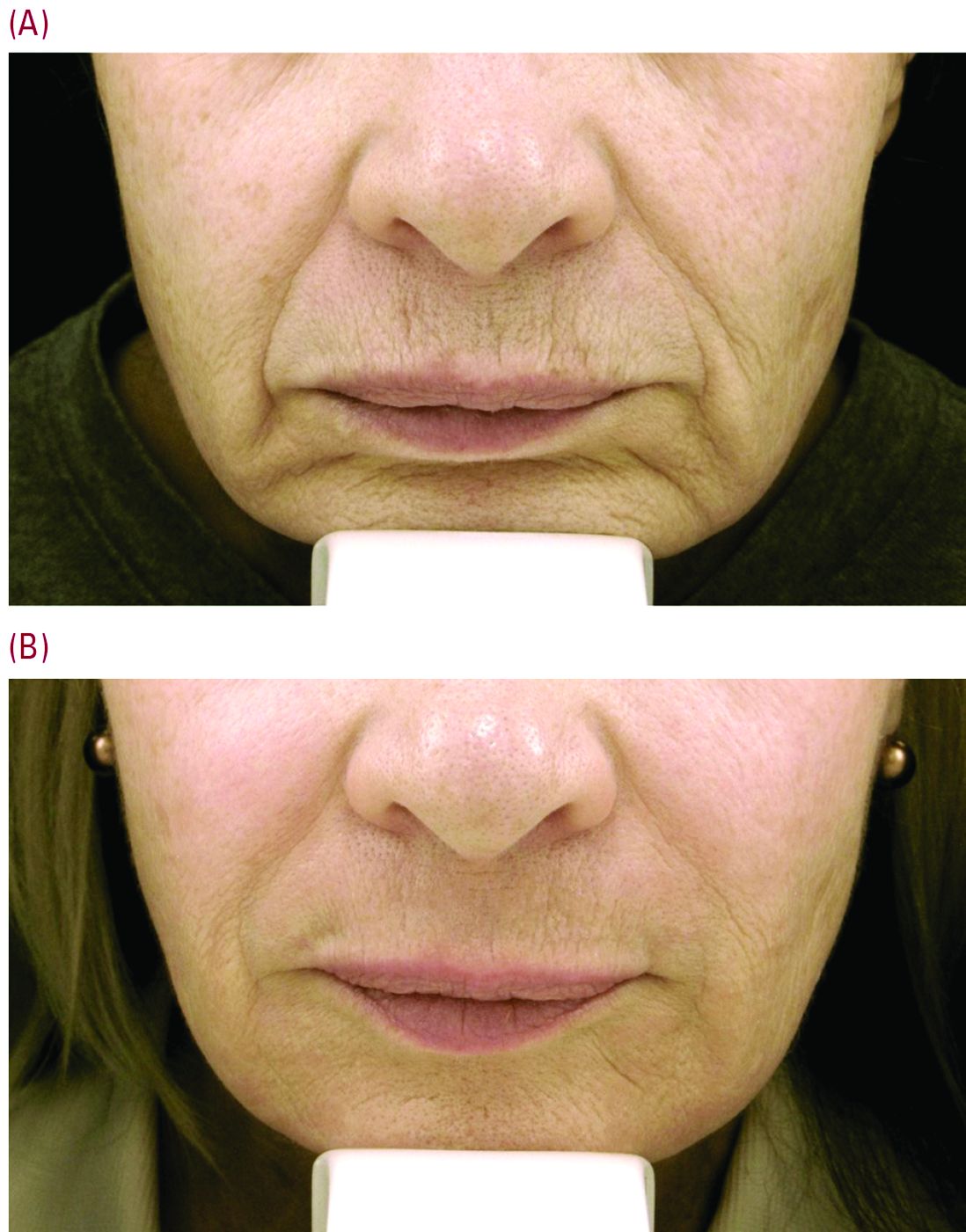

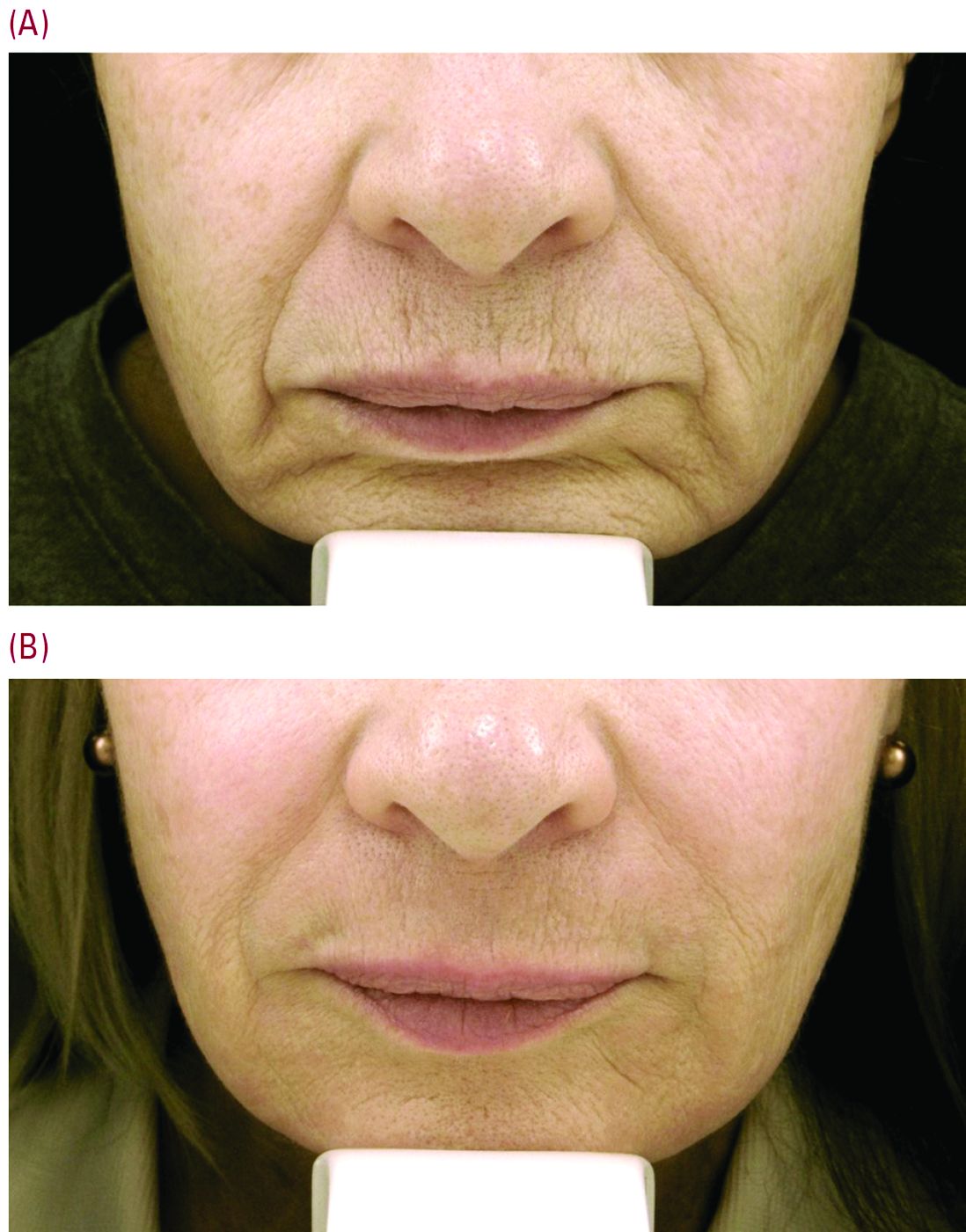

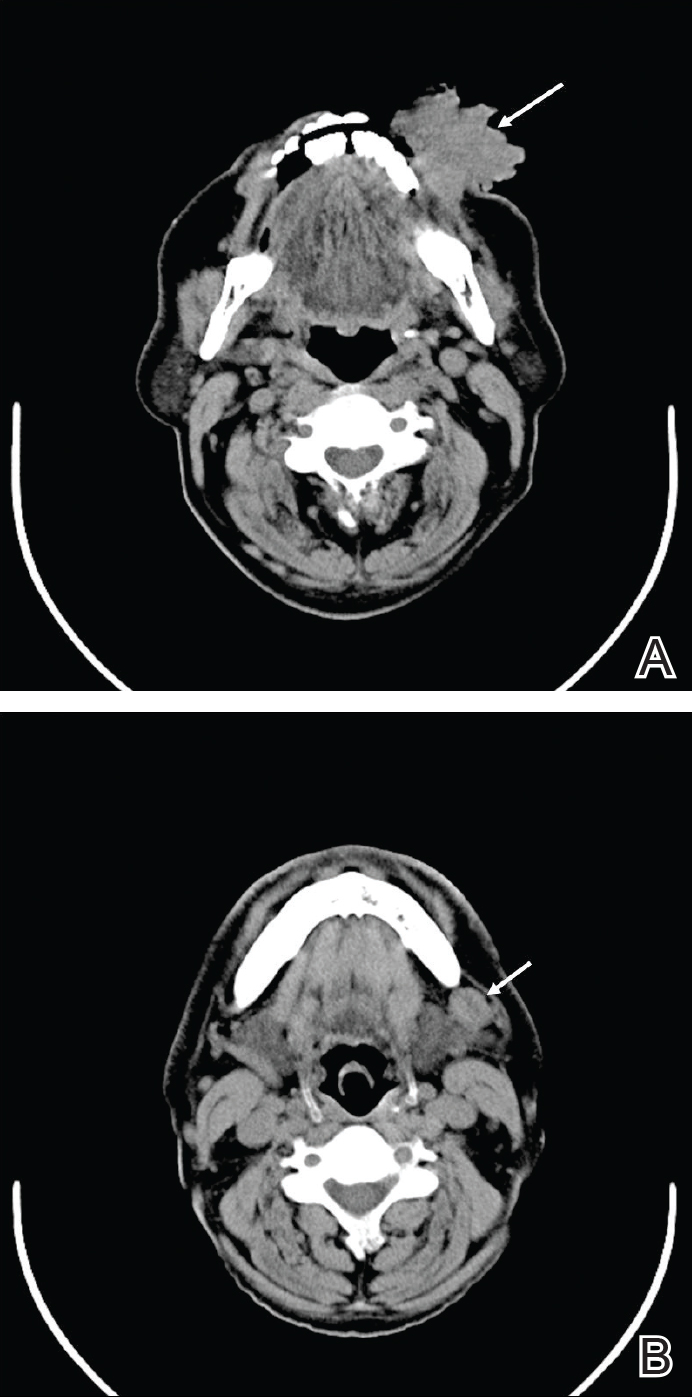

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

Practice Points

- Hair loss is a common late side effect of vismodegib usage and is reversible, but regrowth takes many months.

- Mild folliculitis that resolves spontaneously has been observed in patients using vismodegib.

- Dermal hypersensitivity has been observed in patients on vismodegib, though the exact frequency of this type of dermatitis is not known.

Racial differences in skin cancer risk after organ transplantation

Nonwhite organ transplant recipients (OTRs) are more likely to present with inflammatory or infectious conditions after transplantation, while white organ recipients more commonly present with malignant disease, new research suggests.

While the high incidence of skin cancers has been well described in patients who undergo solid organ transplants, little is known about the risk factors, incidence, locations, and types of skin disease that occur in nonwhite OTRs, wrote Christina Lee Chung, MD, from Drexel University, Philadelphia, and her coauthors in JAMA Dermatology.

In a retrospective review, the investigators examined the medical records of 412 organ transplant recipients treated at an academic referral center during 2011-2016, of whom 154 were white, 35 were Asian, 33 were Hispanic, and 190 were black (JAMA Dermatology. 2017 Mar 8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0045).

Among the white patients, malignant or premalignant disease was the most common diagnostic category (67.8%), followed by inflammatory (20.7%) and infectious processes (11.6%). However, among nonwhite organ transplant recipients, inflammatory processes were present in 48.8% of patients, infectious processes in 37.5% and the remaining 13.7% presented with malignant or premalignant lesions.

Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to present with inflammatory or infectious disease; only 8.6% presented with malignant conditions and 16% presented with premalignant disease.

Among the Asian patient population, one-third presented with malignant or premalignant, one-third presented with infectious, and one-third presented with inflammatory conditions.

“Although early detection and treatment of cancer is vital, nonwhite OTRs would also benefit from addressing nonmalignant processes that are exacerbated by immunosuppression,” the authors wrote.

Overall, 389 skin cancers were diagnosed, with squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC) the most common type of skin cancer diagnosed in each racial or ethnic group. The mean time between transplant and first skin cancer lesion was 12.67 years in black patients, 6.5 years in Hispanic patients, 6.13 years among white patients, and 3.75 years in Asian patients.

The vast majority of skin cancers (95.1%) were found in white patients. While the majority of lesions in white and Asian patients were found in sun-exposed areas, the few skin cancers seen in black patients were more likely to be found in sun-protected areas, particularly the genitals.

Four of the six genital SCCs tested positive for high-risk human papillomavirus strains – in one Asian patient and three black patients – while the two SCCs found on lower extremities in Hispanic patients tested negative for HPV.

Researchers also looked at skin cancer awareness among the organ transplant recipients using data from initial visit questionnaires. They found that more than 17 of the 22 (77.3%) white organ transplant recipients surveyed were aware their skin cancer risk was increased, compared with 30 of the 44 (68.2%) nonwhite patients.

Similarly, 72.7% of white patients surveyed were aware that sunscreen decreased the risk of cancer, compared with 59.1% of nonwhite patients; 27.3% of white patients reported using a daily sunscreen, compared with 13.6% of nonwhite patients.

“Based on our findings, we suggest that optimal posttransplant dermatologic care be determined based on the race or ethnicity of the patients; however, regardless of skin type or race or ethnicity, a baseline full-skin assessment should be performed in all patients,” the authors wrote.

They proposed that skin cancer follow-up screenings should be given to Asian and Hispanic patients immediately after transplant, but that black organ transplant recipients could delay yearly screenings.

However, they said routine skin checks should begin earlier after transplantation for all nonwhite transplant recipients with a history of, or clinically evident HPV infection.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nonwhite organ transplant recipients (OTRs) are more likely to present with inflammatory or infectious conditions after transplantation, while white organ recipients more commonly present with malignant disease, new research suggests.

While the high incidence of skin cancers has been well described in patients who undergo solid organ transplants, little is known about the risk factors, incidence, locations, and types of skin disease that occur in nonwhite OTRs, wrote Christina Lee Chung, MD, from Drexel University, Philadelphia, and her coauthors in JAMA Dermatology.

In a retrospective review, the investigators examined the medical records of 412 organ transplant recipients treated at an academic referral center during 2011-2016, of whom 154 were white, 35 were Asian, 33 were Hispanic, and 190 were black (JAMA Dermatology. 2017 Mar 8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0045).

Among the white patients, malignant or premalignant disease was the most common diagnostic category (67.8%), followed by inflammatory (20.7%) and infectious processes (11.6%). However, among nonwhite organ transplant recipients, inflammatory processes were present in 48.8% of patients, infectious processes in 37.5% and the remaining 13.7% presented with malignant or premalignant lesions.

Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to present with inflammatory or infectious disease; only 8.6% presented with malignant conditions and 16% presented with premalignant disease.

Among the Asian patient population, one-third presented with malignant or premalignant, one-third presented with infectious, and one-third presented with inflammatory conditions.

“Although early detection and treatment of cancer is vital, nonwhite OTRs would also benefit from addressing nonmalignant processes that are exacerbated by immunosuppression,” the authors wrote.

Overall, 389 skin cancers were diagnosed, with squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC) the most common type of skin cancer diagnosed in each racial or ethnic group. The mean time between transplant and first skin cancer lesion was 12.67 years in black patients, 6.5 years in Hispanic patients, 6.13 years among white patients, and 3.75 years in Asian patients.

The vast majority of skin cancers (95.1%) were found in white patients. While the majority of lesions in white and Asian patients were found in sun-exposed areas, the few skin cancers seen in black patients were more likely to be found in sun-protected areas, particularly the genitals.

Four of the six genital SCCs tested positive for high-risk human papillomavirus strains – in one Asian patient and three black patients – while the two SCCs found on lower extremities in Hispanic patients tested negative for HPV.

Researchers also looked at skin cancer awareness among the organ transplant recipients using data from initial visit questionnaires. They found that more than 17 of the 22 (77.3%) white organ transplant recipients surveyed were aware their skin cancer risk was increased, compared with 30 of the 44 (68.2%) nonwhite patients.

Similarly, 72.7% of white patients surveyed were aware that sunscreen decreased the risk of cancer, compared with 59.1% of nonwhite patients; 27.3% of white patients reported using a daily sunscreen, compared with 13.6% of nonwhite patients.

“Based on our findings, we suggest that optimal posttransplant dermatologic care be determined based on the race or ethnicity of the patients; however, regardless of skin type or race or ethnicity, a baseline full-skin assessment should be performed in all patients,” the authors wrote.

They proposed that skin cancer follow-up screenings should be given to Asian and Hispanic patients immediately after transplant, but that black organ transplant recipients could delay yearly screenings.

However, they said routine skin checks should begin earlier after transplantation for all nonwhite transplant recipients with a history of, or clinically evident HPV infection.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nonwhite organ transplant recipients (OTRs) are more likely to present with inflammatory or infectious conditions after transplantation, while white organ recipients more commonly present with malignant disease, new research suggests.

While the high incidence of skin cancers has been well described in patients who undergo solid organ transplants, little is known about the risk factors, incidence, locations, and types of skin disease that occur in nonwhite OTRs, wrote Christina Lee Chung, MD, from Drexel University, Philadelphia, and her coauthors in JAMA Dermatology.

In a retrospective review, the investigators examined the medical records of 412 organ transplant recipients treated at an academic referral center during 2011-2016, of whom 154 were white, 35 were Asian, 33 were Hispanic, and 190 were black (JAMA Dermatology. 2017 Mar 8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0045).

Among the white patients, malignant or premalignant disease was the most common diagnostic category (67.8%), followed by inflammatory (20.7%) and infectious processes (11.6%). However, among nonwhite organ transplant recipients, inflammatory processes were present in 48.8% of patients, infectious processes in 37.5% and the remaining 13.7% presented with malignant or premalignant lesions.

Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to present with inflammatory or infectious disease; only 8.6% presented with malignant conditions and 16% presented with premalignant disease.

Among the Asian patient population, one-third presented with malignant or premalignant, one-third presented with infectious, and one-third presented with inflammatory conditions.

“Although early detection and treatment of cancer is vital, nonwhite OTRs would also benefit from addressing nonmalignant processes that are exacerbated by immunosuppression,” the authors wrote.

Overall, 389 skin cancers were diagnosed, with squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC) the most common type of skin cancer diagnosed in each racial or ethnic group. The mean time between transplant and first skin cancer lesion was 12.67 years in black patients, 6.5 years in Hispanic patients, 6.13 years among white patients, and 3.75 years in Asian patients.

The vast majority of skin cancers (95.1%) were found in white patients. While the majority of lesions in white and Asian patients were found in sun-exposed areas, the few skin cancers seen in black patients were more likely to be found in sun-protected areas, particularly the genitals.

Four of the six genital SCCs tested positive for high-risk human papillomavirus strains – in one Asian patient and three black patients – while the two SCCs found on lower extremities in Hispanic patients tested negative for HPV.

Researchers also looked at skin cancer awareness among the organ transplant recipients using data from initial visit questionnaires. They found that more than 17 of the 22 (77.3%) white organ transplant recipients surveyed were aware their skin cancer risk was increased, compared with 30 of the 44 (68.2%) nonwhite patients.

Similarly, 72.7% of white patients surveyed were aware that sunscreen decreased the risk of cancer, compared with 59.1% of nonwhite patients; 27.3% of white patients reported using a daily sunscreen, compared with 13.6% of nonwhite patients.

“Based on our findings, we suggest that optimal posttransplant dermatologic care be determined based on the race or ethnicity of the patients; however, regardless of skin type or race or ethnicity, a baseline full-skin assessment should be performed in all patients,” the authors wrote.

They proposed that skin cancer follow-up screenings should be given to Asian and Hispanic patients immediately after transplant, but that black organ transplant recipients could delay yearly screenings.

However, they said routine skin checks should begin earlier after transplantation for all nonwhite transplant recipients with a history of, or clinically evident HPV infection.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Nonwhite organ transplant recipients are more likely than are white recipients to present with inflammatory or infectious conditions than with skin cancer after transplantation.

Major finding: Malignant or premalignant disease was seen in 67.8% of white organ transplant recipients but just 13.7% of nonwhite recipients.

Data source: A retrospective review of medical records from 412 organ transplant recipients.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Update on Confocal Microscopy and Skin Cancer Imaging: Report from the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Imatinib Mesylate–Induced Lichenoid Drug Eruption

Imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The indications for imatinib have expanded since its initial approval. It is increasingly important that dermatologists recognize adverse cutaneous manifestations associated with imatinib and are aware of their management and outcomes to avoid unnecessarily discontinuing a potentially lifesaving medication.

Adverse cutaneous manifestations in response to imatinib are not infrequent, accounting for 7% to 21% of all side effects.1 The most frequent cutaneous manifestations of imatinib are dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, and photosensitivity rash, respectively.1 Other less common manifestations include exfoliative dermatitis, nail disorders, psoriasis, folliculitis, hypotrichosis, urticaria, petechiae, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

We report a case of imatinib-induced lichenoid drug eruption (LDE), a rare cutaneous side effect of imatinib use, along with a review of the literature.

Case Report

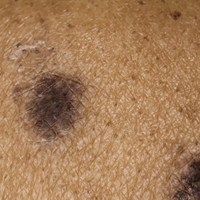

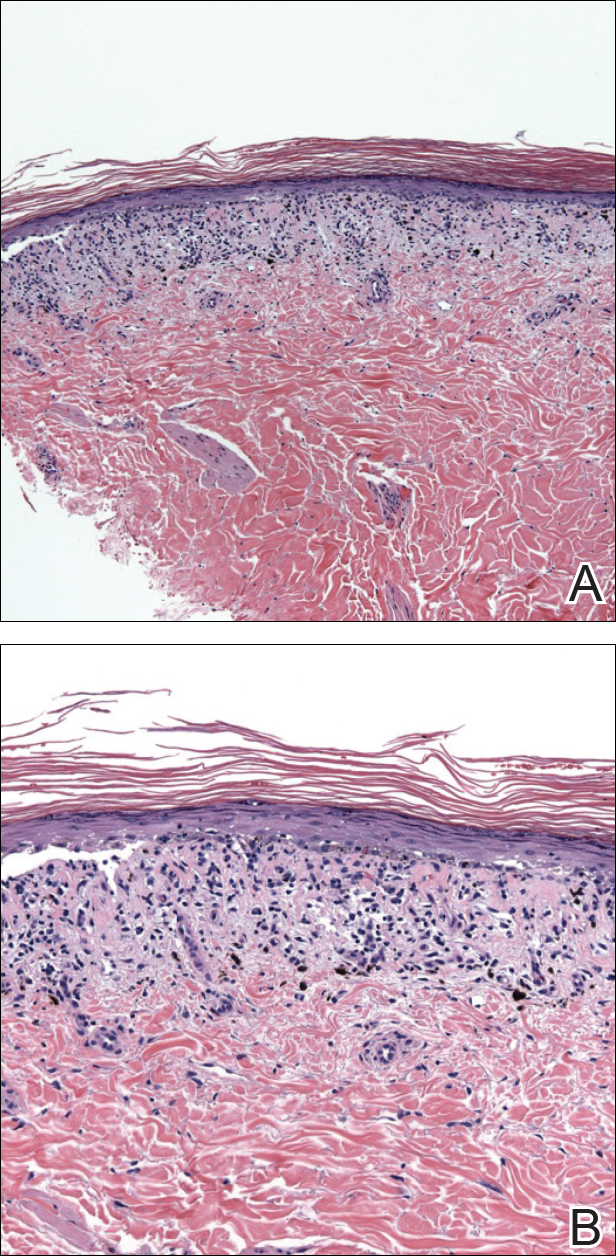

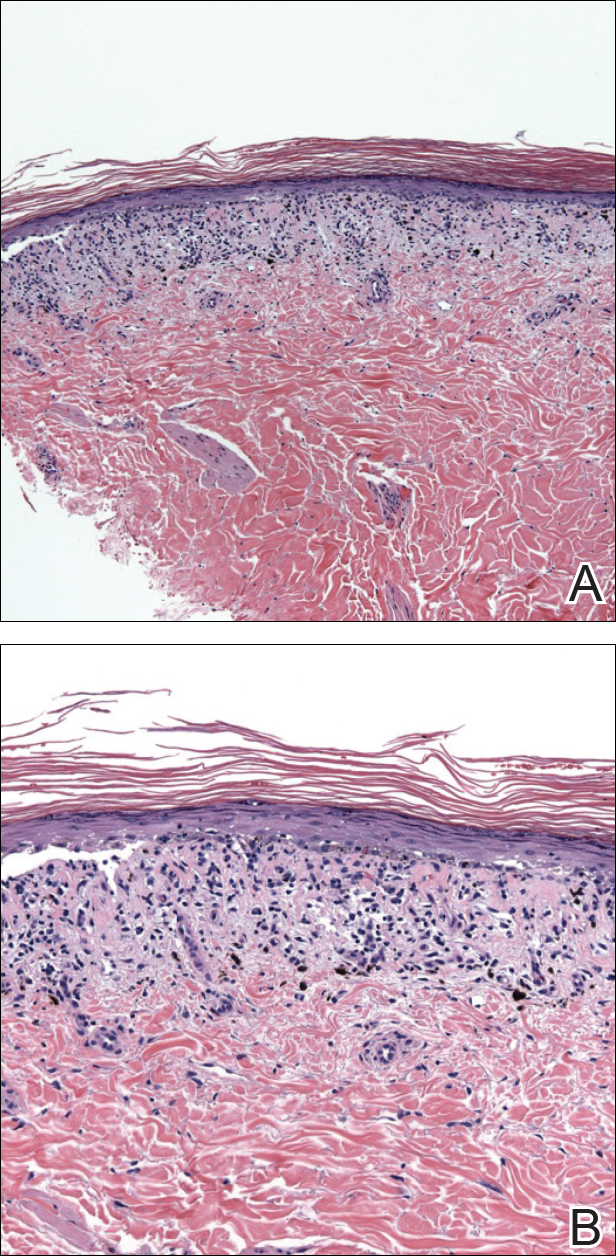

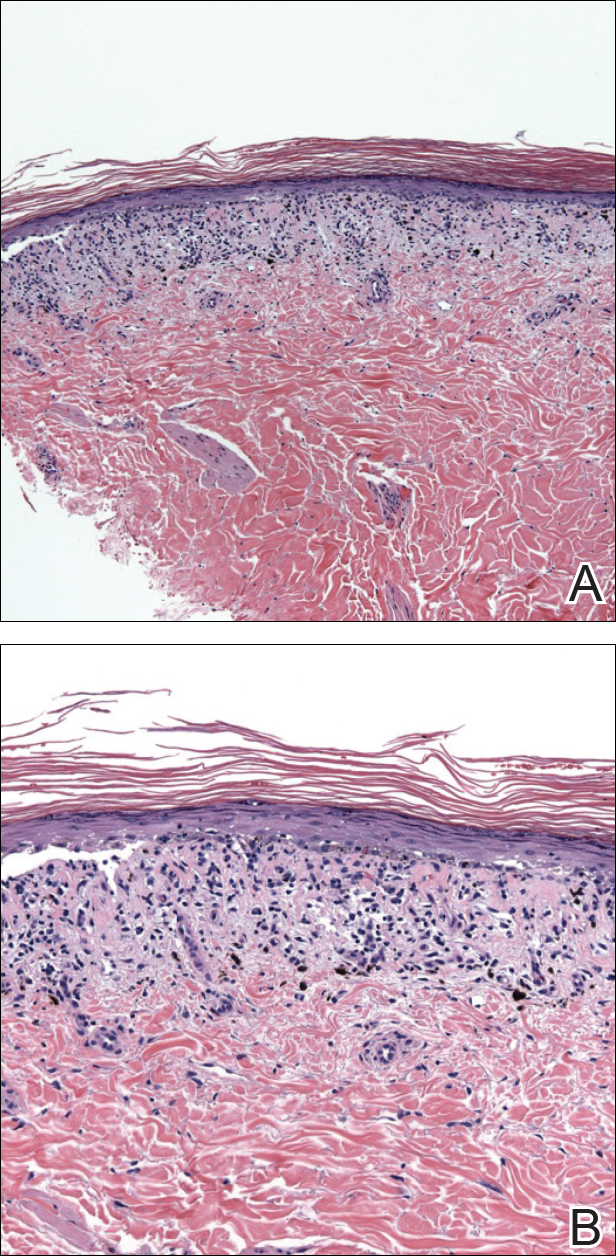

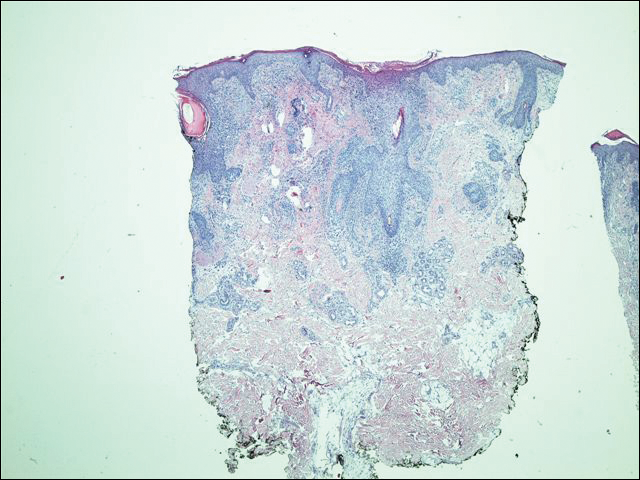

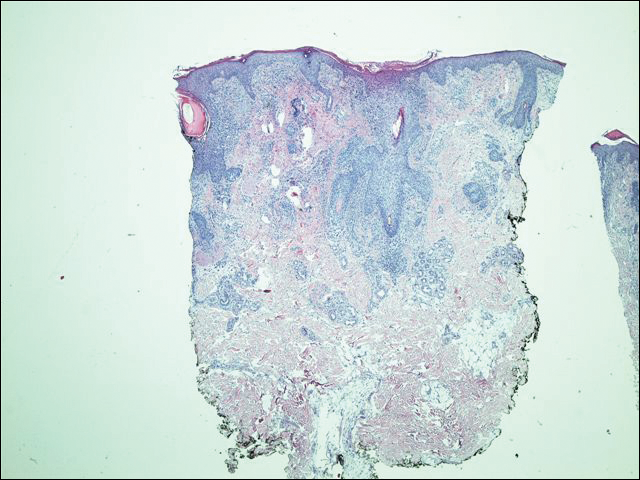

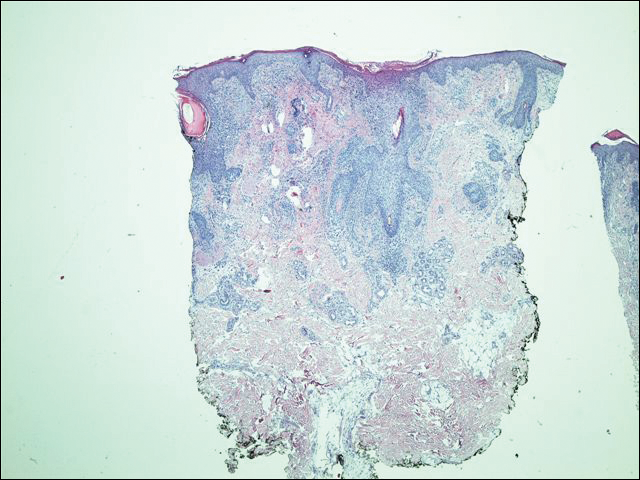

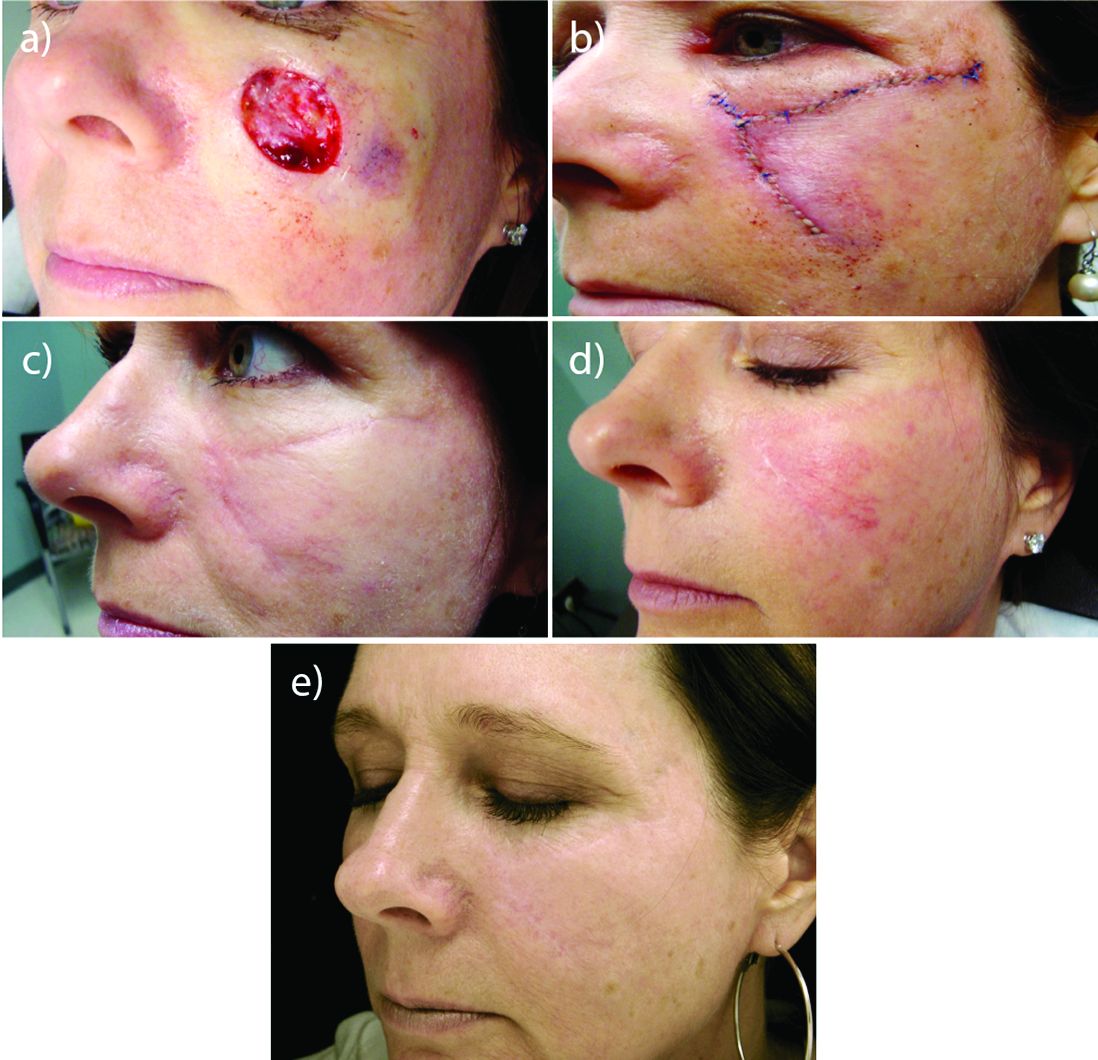

An 86-year-old man with a history of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and myelodysplastic syndrome presented with diffuse hyperpigmented skin lesions on the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip of 2 weeks’ duration. He had been taking imatinib 400 mg once daily for 5 months for GIST. Although the oncologist stopped the medication 2 weeks prior, the lesions were persistent and gradually expanded to involve the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip. He denied any pain or pruritus. Physical examination revealed multiple ill-defined, brown to violaceous, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk (Figures 1A and 1B), arms, and legs (Figure 1C), as well as violaceous to erythematous patches on the mucosal aspect of the lower lip (Figure 2). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the chest and back, which revealed an atrophic epidermis, lichenoid infiltration, and multiple melanophages in the upper dermis consistent with LDE (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Therefore, based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of imatinib-induced LDE was made. He was treated with clobetasol ointment twice daily for 3 weeks with some improvement. His GIST was stable on follow-up computed tomography 3 months after presentation, and imatinib was resumed 1 month later with continued rash that was stable with topical corticosteroid treatment.

Comment

In addition to CML, imatinib has been approved for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and GIST. Moreover, off-label use of imatinib for various other tyrosine kinase–positive cancers and rheumatologic conditions have been documented.2,3 With the expanding use of imatinib, there will be more occasions for dermatologists to encounter cutaneous manifestations associated with its use.

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms imatinib mesylate lichenoid drug, there have been few case reports of LDE associated with imatinib in the literature (eTable).4-24 Compared to classic LDE, imatinib-induced LDE has a few characteristic findings. Classic LDE frequently spares the oral mucosa and genitalia, but imatinib-induced LDE with manifestations on the oral mucosa and genitalia as well as cutaneous eruptions have been reported.4-9 In fact, the first known case of imatinib-induced LDE was an oral eruption in a patient with CML.4 In patients with oral involvement, lesions have been described as lacy reticular macules and violaceous papules, erosions, and ulcers.4,5,12 Interestingly, of those cases manifesting as concomitant oral and cutaneous LDE, the oral eruptions recurred more frequently, with 3 of 12 patients having recurrence of oral lesions after the cutaneous manifestations resolved.8,16 Genital manifestations of imatinib-induced LDE were much less common.9,11

To date, subsequent reports of imatinib-induced LDE have documented skin manifestations consistent with classic LDE occurring in a diffuse, bilateral, photodistributed pattern.10,15,16 One case presented with diffuse hyperpigmentation associated with LDE in a Japanese patient.20 The authors suggested this finding may be more prominent in patients with skin of color,20 which is consistent with the current case. Nail findings such as subungual hyperkeratosis and longitudinal ridging also have been reported.9,11

The latency period between initiation of imat-inib and onset of LDE generally ranges from 1 to 12 months, with onset most commonly occurring between 2 to 5 months or with dosage increase (eTable). Imatinib-induced LDE primarily has been documented with a 400-mg dose, with 1 case of a 600-mg dose and 1 case of an 800-mg dose, which suggests dose dependency. Furthermore, reports exist of several patients responding well to dose reduction with subsequent recurrence on dose reescalation.13,15

Historically, LDE resolves with discontinuation of the drug after a few weeks to months. When discontinuation of imatinib is unfavorable or patients report symptoms including severe pruritus or pain, treatment should be considered. Topical or oral corticosteroids can be used to treat imatinib-induced LDE, similar to lichen planus. When oral corticosteroids are contraindicated (eg, due to poor patient tolerance), oral acitretin at 25 to 35 mg once daily for 6 to 12 weeks has been reported as an alternative treatment.25

In the majority of cases of imatinib-induced LDE, it was undesirable to stop imatinib (eTable). Notably, in half the reported cases, imatinib was able to be continued and patients were treated symptomatically with either oral and/or topical steroids and/or acitretin with complete remission or tolerable recurrences. Dalmau et al9 reported 3 patients who responded poorly to topical and oral steroids and were subsequently treated with acitretin 25 mg once daily; 2 of 3 patients responded favorably to treatment and imatinib was able to be continued. In the current case imatinib initially helped, but because his rash was relatively asymptomatic, imatinib was restarted with control of rash with topical steroids. He developed some pancytopenia, which required intermittent stoppage of the imatinib.

Conclusion

We present a case of imatinib-induced cutaneous and oral LDE in a patient with GIST. Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids all may be reasonable treatment options if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient. If these therapies fail and the eruption is extensive or intolerable, dosage adjustment is another option to consider before discontinuation of imatinib.

- Scheinfeld N. Imatinib mesylate and dermatology part 2: a review of the cutaneous side effects of imatinib mesylate. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:228-231.

- Kim H, Kim NH, Kang HJ, et al. Successful long-term use of imatinib mesylate in pediatric patients with sclerodermatous chronic GVHD. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:910-912.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Doussau A, et al. Imatinib mesylate in scleroderma-associated diffuse skin fibrosis: a phase II multicentre randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1138-1144.

- Lim DS, Muir J. Oral lichenoid reaction to imatinib (STI 571, gleevec). Dermatology. 2002;205:169-171.

- Ena P, Chiarolini F, Siddi GM, et al. Oral lichenoid eruption secondary to imatinib (glivec). J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:253-255.

- Roux C, Boisseau-Garsaud AM, Saint-Cyr I, et al. Lichenoid cutaneous reaction to imatinib. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:571-573.

- Prabhash K, Doval DC. Lichenoid eruption due to imat-inib. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:287-288.

- Pascual JC, Matarredona J, Miralles J, et al. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction secondary to imatinib: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1471-1473.

- Dalmau J, Peramiquel L, Puig L, et al. Imatinib-associated lichenoid eruption: acitretin treatment allows maintained antineoplastic effect. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1213-1216.

- Chan CY, Browning J, Smith-Zagone MJ, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid dermatitis associated with imatinib mesylate. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:29.

- Wahiduzzaman M, Pubalan M. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction with nail changes secondary to imatinib: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Basso FG, Boer CC, Correa ME, et al. Skin and oral lesions associated to imatinib mesylate therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:465-468.

- Kawakami T, Kawanabe T, Soma Y. Cutaneous lichenoid eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Japanese patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:325-326.

- Sendagorta E, Herranz P, Feito M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption related to imatinib: report of a new case and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E315-E316.

- Kuraishi N, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with palmoplantar hyperkeratosis due to imatinib mesylate: a case report and a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:73-76.

- Brazzelli V, Muzio F, Manna G, et al. Photo-induced dermatitis and oral lichenoid reaction in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient treated with imatinib mesylate. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:2-5.

- Ghosh SK. Generalized lichenoid drug eruption associated with imatinib mesylate therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:388-392.

- Lee J, Chung J, Jung M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption after low-dose imatinib mesylate therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:500-502.

- Machaczka M, Gossart M. Multiple skin lesions caused by imatinib mesylate treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:251-252.

- Kagimoto Y, Mizuashi M, Kikuchi K, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with hyperpigmentation caused by imatinib mesylate [published online June 20, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E161-E162.

- Arshdeep, De D, Malhotra P, et al. Imatinib mesylate-induced severe lichenoid rash. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:93-95.

- Lau YM, Lam YK, Leung KH, et al. Trachyonychia in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib mesylate. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:464.e2.

- Bhatia A, Kanish B, Chaudhary P. Lichenoid drug eruption due to imatinib mesylate. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5:68-69.

- Luo JR, Xiang XJ, Xiong JP. Lichenoid drug eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Chinese patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:719-722.

- Laurberg G, Geiger JM, Hjorth N, et al. Treatment of lichen planus with acitretin. a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 65 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:434-437.

Imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The indications for imatinib have expanded since its initial approval. It is increasingly important that dermatologists recognize adverse cutaneous manifestations associated with imatinib and are aware of their management and outcomes to avoid unnecessarily discontinuing a potentially lifesaving medication.

Adverse cutaneous manifestations in response to imatinib are not infrequent, accounting for 7% to 21% of all side effects.1 The most frequent cutaneous manifestations of imatinib are dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, and photosensitivity rash, respectively.1 Other less common manifestations include exfoliative dermatitis, nail disorders, psoriasis, folliculitis, hypotrichosis, urticaria, petechiae, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

We report a case of imatinib-induced lichenoid drug eruption (LDE), a rare cutaneous side effect of imatinib use, along with a review of the literature.

Case Report

An 86-year-old man with a history of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and myelodysplastic syndrome presented with diffuse hyperpigmented skin lesions on the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip of 2 weeks’ duration. He had been taking imatinib 400 mg once daily for 5 months for GIST. Although the oncologist stopped the medication 2 weeks prior, the lesions were persistent and gradually expanded to involve the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip. He denied any pain or pruritus. Physical examination revealed multiple ill-defined, brown to violaceous, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk (Figures 1A and 1B), arms, and legs (Figure 1C), as well as violaceous to erythematous patches on the mucosal aspect of the lower lip (Figure 2). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the chest and back, which revealed an atrophic epidermis, lichenoid infiltration, and multiple melanophages in the upper dermis consistent with LDE (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Therefore, based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of imatinib-induced LDE was made. He was treated with clobetasol ointment twice daily for 3 weeks with some improvement. His GIST was stable on follow-up computed tomography 3 months after presentation, and imatinib was resumed 1 month later with continued rash that was stable with topical corticosteroid treatment.

Comment

In addition to CML, imatinib has been approved for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and GIST. Moreover, off-label use of imatinib for various other tyrosine kinase–positive cancers and rheumatologic conditions have been documented.2,3 With the expanding use of imatinib, there will be more occasions for dermatologists to encounter cutaneous manifestations associated with its use.

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms imatinib mesylate lichenoid drug, there have been few case reports of LDE associated with imatinib in the literature (eTable).4-24 Compared to classic LDE, imatinib-induced LDE has a few characteristic findings. Classic LDE frequently spares the oral mucosa and genitalia, but imatinib-induced LDE with manifestations on the oral mucosa and genitalia as well as cutaneous eruptions have been reported.4-9 In fact, the first known case of imatinib-induced LDE was an oral eruption in a patient with CML.4 In patients with oral involvement, lesions have been described as lacy reticular macules and violaceous papules, erosions, and ulcers.4,5,12 Interestingly, of those cases manifesting as concomitant oral and cutaneous LDE, the oral eruptions recurred more frequently, with 3 of 12 patients having recurrence of oral lesions after the cutaneous manifestations resolved.8,16 Genital manifestations of imatinib-induced LDE were much less common.9,11

To date, subsequent reports of imatinib-induced LDE have documented skin manifestations consistent with classic LDE occurring in a diffuse, bilateral, photodistributed pattern.10,15,16 One case presented with diffuse hyperpigmentation associated with LDE in a Japanese patient.20 The authors suggested this finding may be more prominent in patients with skin of color,20 which is consistent with the current case. Nail findings such as subungual hyperkeratosis and longitudinal ridging also have been reported.9,11

The latency period between initiation of imat-inib and onset of LDE generally ranges from 1 to 12 months, with onset most commonly occurring between 2 to 5 months or with dosage increase (eTable). Imatinib-induced LDE primarily has been documented with a 400-mg dose, with 1 case of a 600-mg dose and 1 case of an 800-mg dose, which suggests dose dependency. Furthermore, reports exist of several patients responding well to dose reduction with subsequent recurrence on dose reescalation.13,15

Historically, LDE resolves with discontinuation of the drug after a few weeks to months. When discontinuation of imatinib is unfavorable or patients report symptoms including severe pruritus or pain, treatment should be considered. Topical or oral corticosteroids can be used to treat imatinib-induced LDE, similar to lichen planus. When oral corticosteroids are contraindicated (eg, due to poor patient tolerance), oral acitretin at 25 to 35 mg once daily for 6 to 12 weeks has been reported as an alternative treatment.25

In the majority of cases of imatinib-induced LDE, it was undesirable to stop imatinib (eTable). Notably, in half the reported cases, imatinib was able to be continued and patients were treated symptomatically with either oral and/or topical steroids and/or acitretin with complete remission or tolerable recurrences. Dalmau et al9 reported 3 patients who responded poorly to topical and oral steroids and were subsequently treated with acitretin 25 mg once daily; 2 of 3 patients responded favorably to treatment and imatinib was able to be continued. In the current case imatinib initially helped, but because his rash was relatively asymptomatic, imatinib was restarted with control of rash with topical steroids. He developed some pancytopenia, which required intermittent stoppage of the imatinib.

Conclusion

We present a case of imatinib-induced cutaneous and oral LDE in a patient with GIST. Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids all may be reasonable treatment options if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient. If these therapies fail and the eruption is extensive or intolerable, dosage adjustment is another option to consider before discontinuation of imatinib.

Imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The indications for imatinib have expanded since its initial approval. It is increasingly important that dermatologists recognize adverse cutaneous manifestations associated with imatinib and are aware of their management and outcomes to avoid unnecessarily discontinuing a potentially lifesaving medication.

Adverse cutaneous manifestations in response to imatinib are not infrequent, accounting for 7% to 21% of all side effects.1 The most frequent cutaneous manifestations of imatinib are dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, and photosensitivity rash, respectively.1 Other less common manifestations include exfoliative dermatitis, nail disorders, psoriasis, folliculitis, hypotrichosis, urticaria, petechiae, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

We report a case of imatinib-induced lichenoid drug eruption (LDE), a rare cutaneous side effect of imatinib use, along with a review of the literature.

Case Report

An 86-year-old man with a history of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and myelodysplastic syndrome presented with diffuse hyperpigmented skin lesions on the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip of 2 weeks’ duration. He had been taking imatinib 400 mg once daily for 5 months for GIST. Although the oncologist stopped the medication 2 weeks prior, the lesions were persistent and gradually expanded to involve the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip. He denied any pain or pruritus. Physical examination revealed multiple ill-defined, brown to violaceous, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk (Figures 1A and 1B), arms, and legs (Figure 1C), as well as violaceous to erythematous patches on the mucosal aspect of the lower lip (Figure 2). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the chest and back, which revealed an atrophic epidermis, lichenoid infiltration, and multiple melanophages in the upper dermis consistent with LDE (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Therefore, based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of imatinib-induced LDE was made. He was treated with clobetasol ointment twice daily for 3 weeks with some improvement. His GIST was stable on follow-up computed tomography 3 months after presentation, and imatinib was resumed 1 month later with continued rash that was stable with topical corticosteroid treatment.

Comment

In addition to CML, imatinib has been approved for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and GIST. Moreover, off-label use of imatinib for various other tyrosine kinase–positive cancers and rheumatologic conditions have been documented.2,3 With the expanding use of imatinib, there will be more occasions for dermatologists to encounter cutaneous manifestations associated with its use.

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms imatinib mesylate lichenoid drug, there have been few case reports of LDE associated with imatinib in the literature (eTable).4-24 Compared to classic LDE, imatinib-induced LDE has a few characteristic findings. Classic LDE frequently spares the oral mucosa and genitalia, but imatinib-induced LDE with manifestations on the oral mucosa and genitalia as well as cutaneous eruptions have been reported.4-9 In fact, the first known case of imatinib-induced LDE was an oral eruption in a patient with CML.4 In patients with oral involvement, lesions have been described as lacy reticular macules and violaceous papules, erosions, and ulcers.4,5,12 Interestingly, of those cases manifesting as concomitant oral and cutaneous LDE, the oral eruptions recurred more frequently, with 3 of 12 patients having recurrence of oral lesions after the cutaneous manifestations resolved.8,16 Genital manifestations of imatinib-induced LDE were much less common.9,11

To date, subsequent reports of imatinib-induced LDE have documented skin manifestations consistent with classic LDE occurring in a diffuse, bilateral, photodistributed pattern.10,15,16 One case presented with diffuse hyperpigmentation associated with LDE in a Japanese patient.20 The authors suggested this finding may be more prominent in patients with skin of color,20 which is consistent with the current case. Nail findings such as subungual hyperkeratosis and longitudinal ridging also have been reported.9,11

The latency period between initiation of imat-inib and onset of LDE generally ranges from 1 to 12 months, with onset most commonly occurring between 2 to 5 months or with dosage increase (eTable). Imatinib-induced LDE primarily has been documented with a 400-mg dose, with 1 case of a 600-mg dose and 1 case of an 800-mg dose, which suggests dose dependency. Furthermore, reports exist of several patients responding well to dose reduction with subsequent recurrence on dose reescalation.13,15

Historically, LDE resolves with discontinuation of the drug after a few weeks to months. When discontinuation of imatinib is unfavorable or patients report symptoms including severe pruritus or pain, treatment should be considered. Topical or oral corticosteroids can be used to treat imatinib-induced LDE, similar to lichen planus. When oral corticosteroids are contraindicated (eg, due to poor patient tolerance), oral acitretin at 25 to 35 mg once daily for 6 to 12 weeks has been reported as an alternative treatment.25

In the majority of cases of imatinib-induced LDE, it was undesirable to stop imatinib (eTable). Notably, in half the reported cases, imatinib was able to be continued and patients were treated symptomatically with either oral and/or topical steroids and/or acitretin with complete remission or tolerable recurrences. Dalmau et al9 reported 3 patients who responded poorly to topical and oral steroids and were subsequently treated with acitretin 25 mg once daily; 2 of 3 patients responded favorably to treatment and imatinib was able to be continued. In the current case imatinib initially helped, but because his rash was relatively asymptomatic, imatinib was restarted with control of rash with topical steroids. He developed some pancytopenia, which required intermittent stoppage of the imatinib.

Conclusion

We present a case of imatinib-induced cutaneous and oral LDE in a patient with GIST. Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids all may be reasonable treatment options if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient. If these therapies fail and the eruption is extensive or intolerable, dosage adjustment is another option to consider before discontinuation of imatinib.

- Scheinfeld N. Imatinib mesylate and dermatology part 2: a review of the cutaneous side effects of imatinib mesylate. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:228-231.

- Kim H, Kim NH, Kang HJ, et al. Successful long-term use of imatinib mesylate in pediatric patients with sclerodermatous chronic GVHD. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:910-912.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Doussau A, et al. Imatinib mesylate in scleroderma-associated diffuse skin fibrosis: a phase II multicentre randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1138-1144.

- Lim DS, Muir J. Oral lichenoid reaction to imatinib (STI 571, gleevec). Dermatology. 2002;205:169-171.

- Ena P, Chiarolini F, Siddi GM, et al. Oral lichenoid eruption secondary to imatinib (glivec). J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:253-255.

- Roux C, Boisseau-Garsaud AM, Saint-Cyr I, et al. Lichenoid cutaneous reaction to imatinib. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:571-573.

- Prabhash K, Doval DC. Lichenoid eruption due to imat-inib. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:287-288.

- Pascual JC, Matarredona J, Miralles J, et al. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction secondary to imatinib: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1471-1473.

- Dalmau J, Peramiquel L, Puig L, et al. Imatinib-associated lichenoid eruption: acitretin treatment allows maintained antineoplastic effect. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1213-1216.

- Chan CY, Browning J, Smith-Zagone MJ, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid dermatitis associated with imatinib mesylate. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:29.

- Wahiduzzaman M, Pubalan M. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction with nail changes secondary to imatinib: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Basso FG, Boer CC, Correa ME, et al. Skin and oral lesions associated to imatinib mesylate therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:465-468.

- Kawakami T, Kawanabe T, Soma Y. Cutaneous lichenoid eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Japanese patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:325-326.

- Sendagorta E, Herranz P, Feito M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption related to imatinib: report of a new case and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E315-E316.

- Kuraishi N, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with palmoplantar hyperkeratosis due to imatinib mesylate: a case report and a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:73-76.

- Brazzelli V, Muzio F, Manna G, et al. Photo-induced dermatitis and oral lichenoid reaction in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient treated with imatinib mesylate. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:2-5.

- Ghosh SK. Generalized lichenoid drug eruption associated with imatinib mesylate therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:388-392.

- Lee J, Chung J, Jung M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption after low-dose imatinib mesylate therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:500-502.

- Machaczka M, Gossart M. Multiple skin lesions caused by imatinib mesylate treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:251-252.

- Kagimoto Y, Mizuashi M, Kikuchi K, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with hyperpigmentation caused by imatinib mesylate [published online June 20, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E161-E162.

- Arshdeep, De D, Malhotra P, et al. Imatinib mesylate-induced severe lichenoid rash. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:93-95.

- Lau YM, Lam YK, Leung KH, et al. Trachyonychia in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib mesylate. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:464.e2.

- Bhatia A, Kanish B, Chaudhary P. Lichenoid drug eruption due to imatinib mesylate. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5:68-69.

- Luo JR, Xiang XJ, Xiong JP. Lichenoid drug eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Chinese patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:719-722.

- Laurberg G, Geiger JM, Hjorth N, et al. Treatment of lichen planus with acitretin. a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 65 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:434-437.

- Scheinfeld N. Imatinib mesylate and dermatology part 2: a review of the cutaneous side effects of imatinib mesylate. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:228-231.

- Kim H, Kim NH, Kang HJ, et al. Successful long-term use of imatinib mesylate in pediatric patients with sclerodermatous chronic GVHD. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:910-912.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Doussau A, et al. Imatinib mesylate in scleroderma-associated diffuse skin fibrosis: a phase II multicentre randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1138-1144.

- Lim DS, Muir J. Oral lichenoid reaction to imatinib (STI 571, gleevec). Dermatology. 2002;205:169-171.

- Ena P, Chiarolini F, Siddi GM, et al. Oral lichenoid eruption secondary to imatinib (glivec). J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:253-255.

- Roux C, Boisseau-Garsaud AM, Saint-Cyr I, et al. Lichenoid cutaneous reaction to imatinib. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:571-573.

- Prabhash K, Doval DC. Lichenoid eruption due to imat-inib. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:287-288.

- Pascual JC, Matarredona J, Miralles J, et al. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction secondary to imatinib: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1471-1473.

- Dalmau J, Peramiquel L, Puig L, et al. Imatinib-associated lichenoid eruption: acitretin treatment allows maintained antineoplastic effect. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1213-1216.

- Chan CY, Browning J, Smith-Zagone MJ, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid dermatitis associated with imatinib mesylate. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:29.

- Wahiduzzaman M, Pubalan M. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction with nail changes secondary to imatinib: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Basso FG, Boer CC, Correa ME, et al. Skin and oral lesions associated to imatinib mesylate therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:465-468.

- Kawakami T, Kawanabe T, Soma Y. Cutaneous lichenoid eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Japanese patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:325-326.

- Sendagorta E, Herranz P, Feito M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption related to imatinib: report of a new case and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E315-E316.

- Kuraishi N, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with palmoplantar hyperkeratosis due to imatinib mesylate: a case report and a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:73-76.

- Brazzelli V, Muzio F, Manna G, et al. Photo-induced dermatitis and oral lichenoid reaction in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient treated with imatinib mesylate. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:2-5.

- Ghosh SK. Generalized lichenoid drug eruption associated with imatinib mesylate therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:388-392.

- Lee J, Chung J, Jung M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption after low-dose imatinib mesylate therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:500-502.

- Machaczka M, Gossart M. Multiple skin lesions caused by imatinib mesylate treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:251-252.

- Kagimoto Y, Mizuashi M, Kikuchi K, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with hyperpigmentation caused by imatinib mesylate [published online June 20, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E161-E162.

- Arshdeep, De D, Malhotra P, et al. Imatinib mesylate-induced severe lichenoid rash. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:93-95.

- Lau YM, Lam YK, Leung KH, et al. Trachyonychia in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib mesylate. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:464.e2.

- Bhatia A, Kanish B, Chaudhary P. Lichenoid drug eruption due to imatinib mesylate. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5:68-69.

- Luo JR, Xiang XJ, Xiong JP. Lichenoid drug eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Chinese patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:719-722.

- Laurberg G, Geiger JM, Hjorth N, et al. Treatment of lichen planus with acitretin. a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 65 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:434-437.

Practice Points

- Imatinib mesylate can cause cutaneous adverse reactions including dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, photosensitivity rash, and lichenoid drug eruption (LDE).

- Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids may be reasonable treatment options for imatinib-induced LDE if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient.

Late-Onset Bexarotene-Induced CD4 Lymphopenia in a Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma Patient

Infections, autoimmune disease, bone marrow failure, medications, and total-body irradiation may induce CD4 lymphopenia, defined as a CD4 T-cell count below 300 cells/mL or less than 20% of total lymphocytes.1 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the most common cause of CD4 lymphopenia, with sepsis (bacterial and fungal) and postoperative states the most common causes in hospital settings.2 No underlying factors are found in 0.02% of CD4 lymphopenia cases, which are considered to be idiopathic.3,4 We report a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) who developed profound CD4 lymphopenia in the setting of long-term bexarotene therapy.

Case Report

A 63-year-old man with hypertension presented to our dermatology clinic with pruritic scaly plaques on the scalp of 4 months’ duration that had progressed to full-body exfoliative erythroderma (Figure 1). He had diffuse palmoplantar keratoderma and lymphadenopathy. His only long-term medications were terazosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia and atenolol for hypertension; he reported no new medications. Laboratory evaluation revealed normal liver and kidney function. A complete blood cell count (CBC) revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count within reference range (8000/µL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]) but with increased eosinophils (12.9% [reference range, 2.7%]) and monocytes (11.8% [reference range, 4%]) and reduced lymphocytes (16.8% [reference range, 34%]). Flow cytometry showed a CD4:CD8 ratio of 1.18 to 1 (reference range, 0.8–4.2)(absolute CD4+ cells, 764/µL [reference range, 297–1551/µL]; absolute CD8+ cells, 654/µL [reference range, 100–1047/µL]). Skin biopsy revealed subacute spongiotic dermatitis with numerous eosinophils, exocytosis including folliculotropism, and rare atypical lymphocytes (Figure 2). Molecular studies showed T-cell receptor γ gene rearrangement. The patient did not have any other underlying conditions that would predispose him to lymphopenia. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of CTCL stage IIIA was made and agreed on by experts at the University of California, San Diego Dermatology Grand Rounds.

The patient was subsequently started on acitretin, topical corticosteroids, and hydroxyzine. However, the erythroderma progressed and he developed fever, chills, and malaise, and he was hospitalized 2 months later for intensive therapy and to rule out infection. He improved on daily wet wraps, topical steroids, oral antibiotics, and initiation of narrowband UVB therapy. He was discharged 1 week later. Acitretin was switched to bexarotene 3 months later due to peeling and cracking of the palmoplantar skin. The initial dose was 225 mg once daily, which was steadily increased over the next 4 months to a therapeutic dose of 600 mg once daily, which was much lower than the maximum dose of 400 mg/m2 daily (calculated at 750 mg/d in our patient). The patient achieved clinical remission 1 year after initiation of bexarotene in conjunction with narrowband UVB therapy. Serum eosinophils also normalized. Because there were no intolerable side effects, this dose was continued for 2 more years before it was slowly tapered to 375 mg once daily over a 1-year period. The new dose was maintained thereafter. Secondary hypertriglyceridemia and hypothyroidism, known side effects of bexarotene, developed 1 and 5 months after initiating therapy, respectively, and were treated with levothyroxine and fenofibrate. Blood counts were checked every 3 months and remained within reference range. Within the first few months of therapy, lymphocytes did trend down to 16.8%, but segmented neutrophils were normal at 59.4%. For the next 5 years the total WBC count and differential remained within reference range. T-cell subsets and flow cytometry data were not measured. No new medications were started during this period, and none of his existing medications had lymphopenia as a known side effect.

Five years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was still on bexarotene and was suspected to have pneumonia that was treated by his primary care provider with cefuroxime and azithromycin for 2 weeks with no improvement. He was then admitted to the hospital with shortness of breath, productive cough, night sweats, and dyspnea of 1 month’s duration. There was no associated weight loss or fever. Notably, the skin was clear. He was further treated for community-acquired pneumonia, first with vancomycin and ceftazidime, then with ciprofloxacin and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, with no improvement. A CBC with differential was obtained on the patient’s first admission and revealed a WBC count of 3600/µL with decreased lymphocytes (8.6%), no eosinophilia, and anemia (hemoglobin, 10.5 g/dL [reference range, 33–37 g/dL]). T-cell subset studies revealed a CD4:CD8 ratio of 0.06 to 1 (absolute CD4+ cells, 6/µL; absolute CD8+ cells, 107/µL). The patient also had an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 1015 U/L (reference range, 100–200 U/L) and a normal comprehensive metabolic panel. A comprehensive workup, including urine and blood cultures, serum Cryptococcus and coccidioidomycosis IgG/IgM, histoplasmosis urine antigen, legionella, HIV, purified protein derivative (tuberculin), and aspergillosis galactomannan antigen panel, was negative. Blood tests for HIV and human T-lymphotropic virus also were negative. Bronchoscopy with cytology and sputum cultures for fungi, acid-fast bacteria, and viruses identified Pneumocystis jiroveci in the bronchial wash. Pneumocystis pneumonia was treated with intravenous clindamycin, primaquine, and leucovorin. The patient’s WBC count continued to drop over the next 2 weeks to a nadir of 1.7% with few lymphocytes noted on the differential. At that point, the bexarotene was stopped and was considered causative in inducing CD4 lymphopenia, resulting in opportunistic infection. The patient steadily improved and was discharged on sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim prophyla

His CD4 count slowly improved over the next 18 months; however, his skin disease recurred and progressed to exfoliative erythroderma with marked scarring alopecia (Figure 3), facial swelling, extreme pruritus, and notable eosinophilia. Repeat computed tomography was negative for extracutaneous involvement. A repeat skin biopsy showed recurrent mycosis fungoides similar to the original biopsy (Figure 4). Topical steroids and narrowband UVB therapy were restarted. A bone marrow biopsy revealed no definitive lymphoma, but the peripheral blood showed occasional CD8+ “flower cells” and no CD4+ Sézary cells. Two repeat molecular studies failed to show the T-cell receptor gene rearrangement. Localized electron beam radiation therapy, lenalidomide, and clobetasol were tried without benefit. The patient was hospitalized 3 months later and was started on wet wraps as well as weekly infusions of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin (14 mg/m2 over a 4-hour period) on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle with rapid improvement. He experienced transient slight neutropenia with the first several treatments that quickly resolved. His skin was clear while on a regimen of triamcinolone, wet wraps, and intravenous romidepsin. He demonstrated visible improvement after 3 weekly infusions of romedepsin (Figure 5). His skin disease cleared after 9 infusions of romidepsin, and he currently remains in remission; however, he developed presumed bronchopneumonia after approximately 3 to 4 infusions. He then presented with severe headaches after his ninth infusion and was found to have cryptococcal meningitis. Romedepsin was stopped and he was treated with systemic antifungal therapy. His CTCL never recurred despite not restarting romidepsin.

Comment

The retinoids are chemically related to vitamin A. They regulate epithelial cell growth and are beneficial in inflammatory skin disorders and in patients with increased cell turnover as well as in skin cancer and precancer prevention/treatment.5 The first- and second-generation retinoids, isotretinoin and acitretin, respectively, cause anemia or leukopenia in less than 10% of patients; adverse effects are noted more commonly in doses greater than 1 mg/kg daily.6-8

Bexarotene is a third-generation retinoid drug that is more selective for retinoid X receptors. It was approved in 1991 for treatment of advanced CTCL (stages IIB–IVB) in adult patients who have failed at least 1 prior systemic therapy. Bexarotene is noted to promote cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in CTCL cell lines.9 However, one study suggested that for bexarotene, inhibition of proliferation is more important than causing apoptosis in CTCL cells, and this effect is achieved through triggering the p53/p73-dependent cell cycle inhibition pathway.10 Studies in patients with Sézary syndrome have shown that bexarotene changes the chemokine receptor expression in circulating malignant T cells, making them less likely to traffic to the skin (lower chemokine receptor type 4 expression),11 which may explain why some CTCL cases have shown improvement of skin disease on bexarotene despite progression of extradermal disease.12

Common side effects of bexarotene include hyperlipidemia and central hypothyroidism.13 In addition, dose-related myelosuppression with isolated leukopenia, particularly neutropenia, also has been reported (18% of patients at a dosage of 300 mg/m2/d and 43% of patients with a dosage greater than 300 mg/m2/d). Leukopenia generally occurs within the first 4 to 8 weeks of treatment, is relatively mild (WBC, 1000–2999/µL), and generally is reversible.13-15 One review of 66 mycosis fungoides patients treated with bexarotene described a patient who developed leukopenia 15 months after initiating bexarotene therapy.14 The manufacturer recommends that treatment with bexarotene be continued as long as the patient is receiving benefit from the treatment. One trial of 70 mycosis fungoides patient treated with bexarotene reported response rates of 48% on bexarotene monotherapy (n=54) and 69% on bexarotene plus an additional agent (n=16).15 The authors noted higher response rates in patients on 2 lipid-lowering agents. They concluded that bexarotene was a safe and effective agent for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and recommended continued treatment with a lowered dose of bexarotene in those achieving complete responses for a period of 2 years. Although the recommended initial dose is 300 mg/m2/d, bexarotene can be increased to 400 mg/m2/d after 8 weeks if no response to treatment is appreciated.16 Our patient was on a maximum bexarotene dose of 600 mg once daily (280 mg/m2/d) for the first 2 years, and a maintenance dose of 300 mg once daily for the next 3 years. He was not on any medicines known to induce leukopenia and he was not given any known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that could increase the toxicity of bexarotene.

The patient’s CBC was checked routinely every 2 to 3 months after he was started on bexarotene. For 5 years, the CBC and differential remained within reference range; however, his CD4 counts were not followed during those 5 years. We attribute his CD4 lymphopenia and subsequent pneumocystis pneumonia to bexarotene. After our patient’s CD4 lymphopenia was discovered, he developed a precipitous drop in his WBC and lymphocyte counts while hospitalized that worsened over a 2-week period. At this point, the bexarotene was discontinued and his WBC count slowly recovered. We believe that one of the initial antibiotics prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician at initial onset of pneumonia symptoms as an outpatient could have acted synergistically with bexarotene to worsen lymphopenia. Specifically, ceftazidime, vancomycin, and ciprofloxacin have all been reported to cause leukopenia; however, it was neutropenia in these cases, not lymphopenia.17,18 Notwithstanding, the opportunistic pneumonia and therefore CD4 lymphopenia was present prior to any antibiotic use.

The CD4 lymphopenia was unlikely due to underlying infection(s) because an extensive workup was negative, except for the pneumocystis, which likely resulted from the lymphopenia. The CD4 lymphopenia also could be idiopathic, as it has been reported in 3 patients with mycosis fungoides.19 All 3 patients were erythrodermic at presentation and were noted to have numerous CD4+ lymphocytes in the cutaneous lesions but few circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes in the blood. The authors attributed the CD4 lymphopenia to cutaneous sequestration of CD4+ T lymphocytes.19 These cases contrast with our patient who was in clinical remission at the time of CD4 lymphopenia, which improved and normalized following discontinuation of bexarotene.

Conclusion

This case emphasizes the importance of monitoring for leukopenia, specifically CD4 lymphopenia, in patients on long-term bexarotene therapy. Routine CBC as well as T-cell subset counts should be performed during treatment. Rotation off bexarotene after several years of therapy should be considered, even in patients with continuous benefit from this systemic therapy.

- Smith DK, Neal JJ, Holmberg SD. Unexplained opportunistic infections and CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia without HIV infection. an investigation of cases in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control Idiopathic CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia Task Force. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:373-379.

- Castelino DJ, McNair P, Kay TW. Lymphocytopenia in a hospital population: what does it signify? Aust N Z J Med. 1997;27:170-174.

- Zonios DI, Falloon J, Bennett JE, et al. Idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia: natural history and prognostic factors. Blood. 2008;112:287-294.

- Duncan RA, von Reyn CF, Alliegro GM, et al. Idiopathic CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia: four patients with opportunistic infections and no evidence of HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:393-398.

- Bruno NP, Beacham BE, Burnett JW. Adverse effects of isotretinoin therapy. Cutis. 1984;33:484-486, 489.

- Strauss JS, Rapini RP, Shalita AR, et al. Isotretinoin therapy for acne: results of a multicenter dose-response study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:490-496.

- Windhorst DB, Nigra T. General clinical toxicology of oral retinoids. J Am Acad Dermatol.1982;6:675-682.

- Glinnick SE. Leucopenia from accutane: in ten percent? Schoch Let. 1985;35:9.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2011 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:928-948.

- Nieto-Rementería N, Pérez-Yarza G, Boyano MD, et al. Bexarotene activates the p53/p73 pathway in human cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:519-526.

- Richardson SK, Newton SB, Bach TL, et al. Bexarotene blunts malignant T-cell chemotaxis in Sézary syndrome: reduction of chemokine receptor 4-positive lymphocytes and decreased chemotaxis to thymus and activation-regulated chemokine. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:792-797.

- Bouwhuis SA, Davis MD, el-Azhary RA, et al. Bexarotene treatment of late-stage mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: development of extracutaneous lymphoma in 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:991-996.

- Targretin [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc; 2015.

- , , , et al. Bexarotene therapy for mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1299-1307.

- , , et al. Optimizing bexarotene therapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:672-684.

- Scarisbrick JJ, Morris S, Azurdia R, et al. U.K. consensus statement on safe clinical prescribing of bexarotene for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:192-200.

- Black E, Lau TT, Ensom MH. Vancomycin-induced neutropenia: is it dose-or duration related? Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:629-638.

- Choo PW, Gantz NM. Reversible leukopenia related to ciprofloxacin therapy. South Med J. 1990;83:597-598.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths TW, Cooper KD. Idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia in a patient with mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1063-1064.

Infections, autoimmune disease, bone marrow failure, medications, and total-body irradiation may induce CD4 lymphopenia, defined as a CD4 T-cell count below 300 cells/mL or less than 20% of total lymphocytes.1 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the most common cause of CD4 lymphopenia, with sepsis (bacterial and fungal) and postoperative states the most common causes in hospital settings.2 No underlying factors are found in 0.02% of CD4 lymphopenia cases, which are considered to be idiopathic.3,4 We report a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) who developed profound CD4 lymphopenia in the setting of long-term bexarotene therapy.

Case Report

A 63-year-old man with hypertension presented to our dermatology clinic with pruritic scaly plaques on the scalp of 4 months’ duration that had progressed to full-body exfoliative erythroderma (Figure 1). He had diffuse palmoplantar keratoderma and lymphadenopathy. His only long-term medications were terazosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia and atenolol for hypertension; he reported no new medications. Laboratory evaluation revealed normal liver and kidney function. A complete blood cell count (CBC) revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count within reference range (8000/µL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]) but with increased eosinophils (12.9% [reference range, 2.7%]) and monocytes (11.8% [reference range, 4%]) and reduced lymphocytes (16.8% [reference range, 34%]). Flow cytometry showed a CD4:CD8 ratio of 1.18 to 1 (reference range, 0.8–4.2)(absolute CD4+ cells, 764/µL [reference range, 297–1551/µL]; absolute CD8+ cells, 654/µL [reference range, 100–1047/µL]). Skin biopsy revealed subacute spongiotic dermatitis with numerous eosinophils, exocytosis including folliculotropism, and rare atypical lymphocytes (Figure 2). Molecular studies showed T-cell receptor γ gene rearrangement. The patient did not have any other underlying conditions that would predispose him to lymphopenia. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of CTCL stage IIIA was made and agreed on by experts at the University of California, San Diego Dermatology Grand Rounds.

The patient was subsequently started on acitretin, topical corticosteroids, and hydroxyzine. However, the erythroderma progressed and he developed fever, chills, and malaise, and he was hospitalized 2 months later for intensive therapy and to rule out infection. He improved on daily wet wraps, topical steroids, oral antibiotics, and initiation of narrowband UVB therapy. He was discharged 1 week later. Acitretin was switched to bexarotene 3 months later due to peeling and cracking of the palmoplantar skin. The initial dose was 225 mg once daily, which was steadily increased over the next 4 months to a therapeutic dose of 600 mg once daily, which was much lower than the maximum dose of 400 mg/m2 daily (calculated at 750 mg/d in our patient). The patient achieved clinical remission 1 year after initiation of bexarotene in conjunction with narrowband UVB therapy. Serum eosinophils also normalized. Because there were no intolerable side effects, this dose was continued for 2 more years before it was slowly tapered to 375 mg once daily over a 1-year period. The new dose was maintained thereafter. Secondary hypertriglyceridemia and hypothyroidism, known side effects of bexarotene, developed 1 and 5 months after initiating therapy, respectively, and were treated with levothyroxine and fenofibrate. Blood counts were checked every 3 months and remained within reference range. Within the first few months of therapy, lymphocytes did trend down to 16.8%, but segmented neutrophils were normal at 59.4%. For the next 5 years the total WBC count and differential remained within reference range. T-cell subsets and flow cytometry data were not measured. No new medications were started during this period, and none of his existing medications had lymphopenia as a known side effect.