User login

Imatinib Mesylate–Induced Lichenoid Drug Eruption

Imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The indications for imatinib have expanded since its initial approval. It is increasingly important that dermatologists recognize adverse cutaneous manifestations associated with imatinib and are aware of their management and outcomes to avoid unnecessarily discontinuing a potentially lifesaving medication.

Adverse cutaneous manifestations in response to imatinib are not infrequent, accounting for 7% to 21% of all side effects.1 The most frequent cutaneous manifestations of imatinib are dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, and photosensitivity rash, respectively.1 Other less common manifestations include exfoliative dermatitis, nail disorders, psoriasis, folliculitis, hypotrichosis, urticaria, petechiae, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

We report a case of imatinib-induced lichenoid drug eruption (LDE), a rare cutaneous side effect of imatinib use, along with a review of the literature.

Case Report

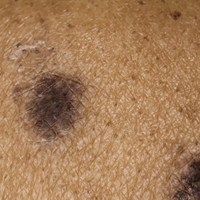

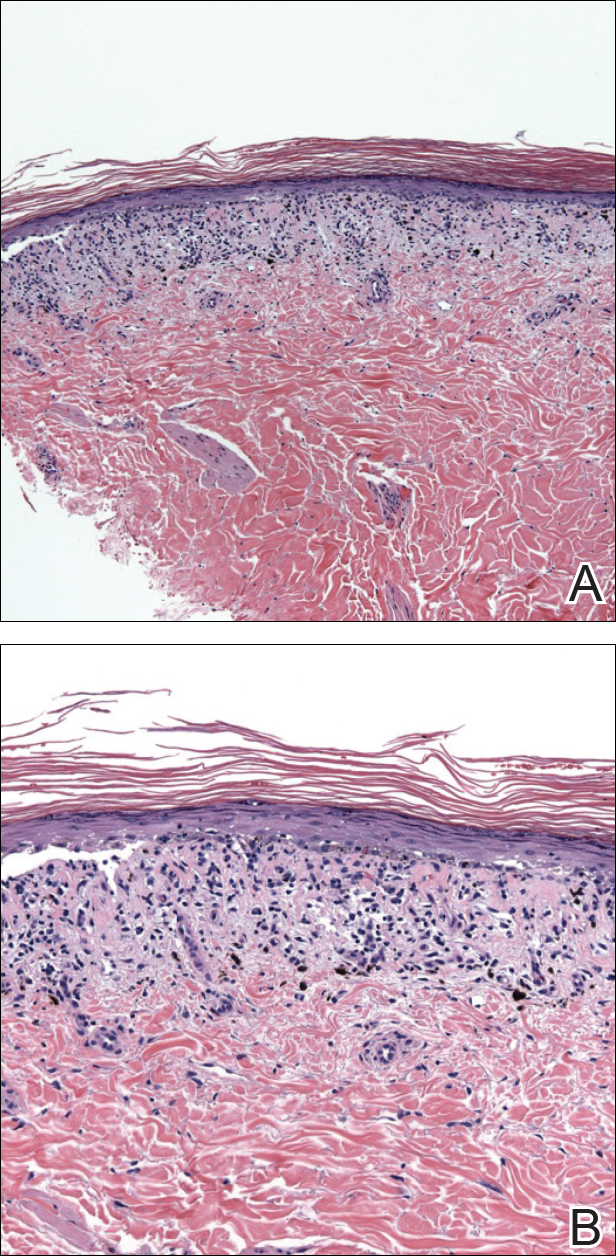

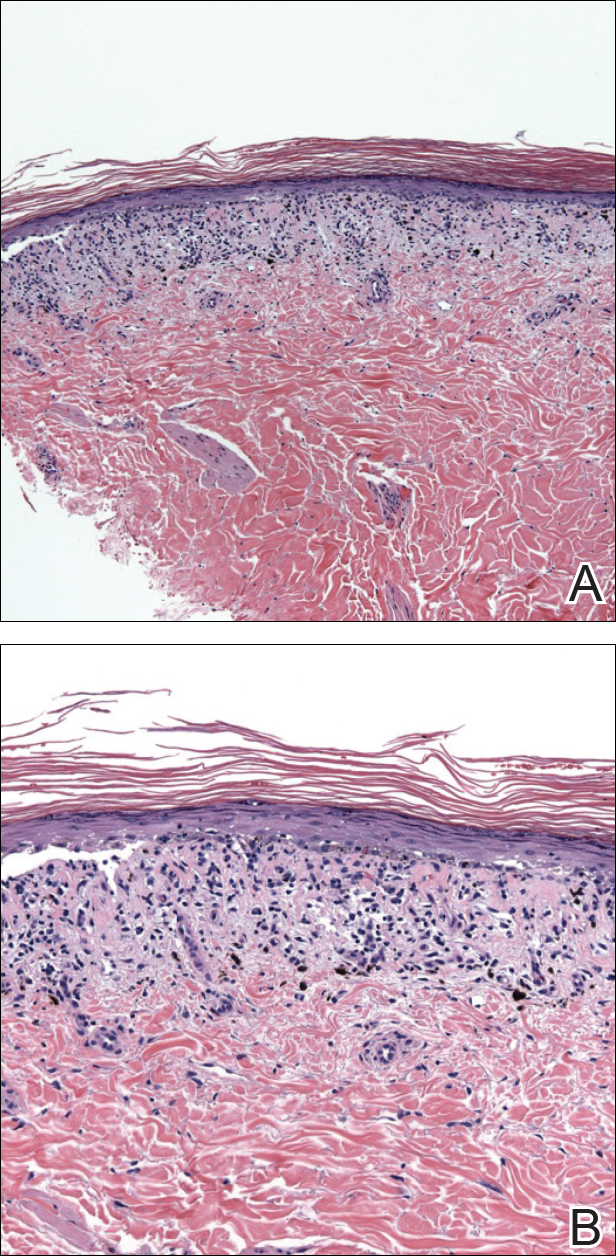

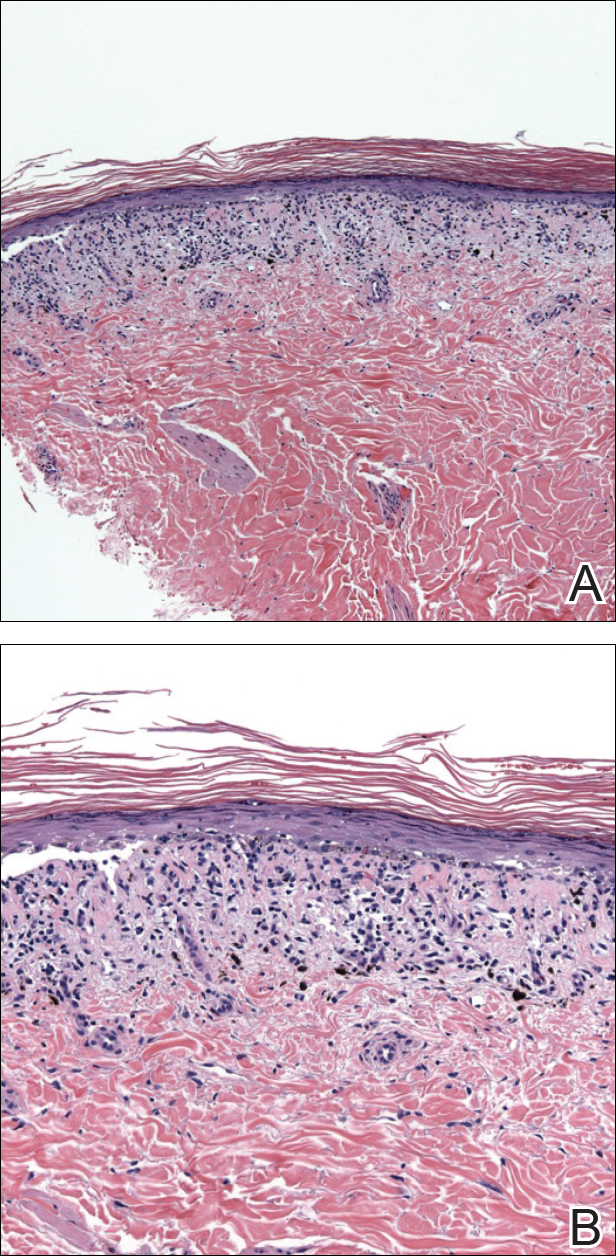

An 86-year-old man with a history of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and myelodysplastic syndrome presented with diffuse hyperpigmented skin lesions on the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip of 2 weeks’ duration. He had been taking imatinib 400 mg once daily for 5 months for GIST. Although the oncologist stopped the medication 2 weeks prior, the lesions were persistent and gradually expanded to involve the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip. He denied any pain or pruritus. Physical examination revealed multiple ill-defined, brown to violaceous, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk (Figures 1A and 1B), arms, and legs (Figure 1C), as well as violaceous to erythematous patches on the mucosal aspect of the lower lip (Figure 2). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the chest and back, which revealed an atrophic epidermis, lichenoid infiltration, and multiple melanophages in the upper dermis consistent with LDE (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Therefore, based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of imatinib-induced LDE was made. He was treated with clobetasol ointment twice daily for 3 weeks with some improvement. His GIST was stable on follow-up computed tomography 3 months after presentation, and imatinib was resumed 1 month later with continued rash that was stable with topical corticosteroid treatment.

Comment

In addition to CML, imatinib has been approved for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and GIST. Moreover, off-label use of imatinib for various other tyrosine kinase–positive cancers and rheumatologic conditions have been documented.2,3 With the expanding use of imatinib, there will be more occasions for dermatologists to encounter cutaneous manifestations associated with its use.

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms imatinib mesylate lichenoid drug, there have been few case reports of LDE associated with imatinib in the literature (eTable).4-24 Compared to classic LDE, imatinib-induced LDE has a few characteristic findings. Classic LDE frequently spares the oral mucosa and genitalia, but imatinib-induced LDE with manifestations on the oral mucosa and genitalia as well as cutaneous eruptions have been reported.4-9 In fact, the first known case of imatinib-induced LDE was an oral eruption in a patient with CML.4 In patients with oral involvement, lesions have been described as lacy reticular macules and violaceous papules, erosions, and ulcers.4,5,12 Interestingly, of those cases manifesting as concomitant oral and cutaneous LDE, the oral eruptions recurred more frequently, with 3 of 12 patients having recurrence of oral lesions after the cutaneous manifestations resolved.8,16 Genital manifestations of imatinib-induced LDE were much less common.9,11

To date, subsequent reports of imatinib-induced LDE have documented skin manifestations consistent with classic LDE occurring in a diffuse, bilateral, photodistributed pattern.10,15,16 One case presented with diffuse hyperpigmentation associated with LDE in a Japanese patient.20 The authors suggested this finding may be more prominent in patients with skin of color,20 which is consistent with the current case. Nail findings such as subungual hyperkeratosis and longitudinal ridging also have been reported.9,11

The latency period between initiation of imat-inib and onset of LDE generally ranges from 1 to 12 months, with onset most commonly occurring between 2 to 5 months or with dosage increase (eTable). Imatinib-induced LDE primarily has been documented with a 400-mg dose, with 1 case of a 600-mg dose and 1 case of an 800-mg dose, which suggests dose dependency. Furthermore, reports exist of several patients responding well to dose reduction with subsequent recurrence on dose reescalation.13,15

Historically, LDE resolves with discontinuation of the drug after a few weeks to months. When discontinuation of imatinib is unfavorable or patients report symptoms including severe pruritus or pain, treatment should be considered. Topical or oral corticosteroids can be used to treat imatinib-induced LDE, similar to lichen planus. When oral corticosteroids are contraindicated (eg, due to poor patient tolerance), oral acitretin at 25 to 35 mg once daily for 6 to 12 weeks has been reported as an alternative treatment.25

In the majority of cases of imatinib-induced LDE, it was undesirable to stop imatinib (eTable). Notably, in half the reported cases, imatinib was able to be continued and patients were treated symptomatically with either oral and/or topical steroids and/or acitretin with complete remission or tolerable recurrences. Dalmau et al9 reported 3 patients who responded poorly to topical and oral steroids and were subsequently treated with acitretin 25 mg once daily; 2 of 3 patients responded favorably to treatment and imatinib was able to be continued. In the current case imatinib initially helped, but because his rash was relatively asymptomatic, imatinib was restarted with control of rash with topical steroids. He developed some pancytopenia, which required intermittent stoppage of the imatinib.

Conclusion

We present a case of imatinib-induced cutaneous and oral LDE in a patient with GIST. Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids all may be reasonable treatment options if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient. If these therapies fail and the eruption is extensive or intolerable, dosage adjustment is another option to consider before discontinuation of imatinib.

- Scheinfeld N. Imatinib mesylate and dermatology part 2: a review of the cutaneous side effects of imatinib mesylate. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:228-231.

- Kim H, Kim NH, Kang HJ, et al. Successful long-term use of imatinib mesylate in pediatric patients with sclerodermatous chronic GVHD. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:910-912.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Doussau A, et al. Imatinib mesylate in scleroderma-associated diffuse skin fibrosis: a phase II multicentre randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1138-1144.

- Lim DS, Muir J. Oral lichenoid reaction to imatinib (STI 571, gleevec). Dermatology. 2002;205:169-171.

- Ena P, Chiarolini F, Siddi GM, et al. Oral lichenoid eruption secondary to imatinib (glivec). J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:253-255.

- Roux C, Boisseau-Garsaud AM, Saint-Cyr I, et al. Lichenoid cutaneous reaction to imatinib. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:571-573.

- Prabhash K, Doval DC. Lichenoid eruption due to imat-inib. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:287-288.

- Pascual JC, Matarredona J, Miralles J, et al. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction secondary to imatinib: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1471-1473.

- Dalmau J, Peramiquel L, Puig L, et al. Imatinib-associated lichenoid eruption: acitretin treatment allows maintained antineoplastic effect. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1213-1216.

- Chan CY, Browning J, Smith-Zagone MJ, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid dermatitis associated with imatinib mesylate. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:29.

- Wahiduzzaman M, Pubalan M. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction with nail changes secondary to imatinib: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Basso FG, Boer CC, Correa ME, et al. Skin and oral lesions associated to imatinib mesylate therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:465-468.

- Kawakami T, Kawanabe T, Soma Y. Cutaneous lichenoid eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Japanese patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:325-326.

- Sendagorta E, Herranz P, Feito M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption related to imatinib: report of a new case and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E315-E316.

- Kuraishi N, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with palmoplantar hyperkeratosis due to imatinib mesylate: a case report and a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:73-76.

- Brazzelli V, Muzio F, Manna G, et al. Photo-induced dermatitis and oral lichenoid reaction in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient treated with imatinib mesylate. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:2-5.

- Ghosh SK. Generalized lichenoid drug eruption associated with imatinib mesylate therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:388-392.

- Lee J, Chung J, Jung M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption after low-dose imatinib mesylate therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:500-502.

- Machaczka M, Gossart M. Multiple skin lesions caused by imatinib mesylate treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:251-252.

- Kagimoto Y, Mizuashi M, Kikuchi K, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with hyperpigmentation caused by imatinib mesylate [published online June 20, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E161-E162.

- Arshdeep, De D, Malhotra P, et al. Imatinib mesylate-induced severe lichenoid rash. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:93-95.

- Lau YM, Lam YK, Leung KH, et al. Trachyonychia in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib mesylate. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:464.e2.

- Bhatia A, Kanish B, Chaudhary P. Lichenoid drug eruption due to imatinib mesylate. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5:68-69.

- Luo JR, Xiang XJ, Xiong JP. Lichenoid drug eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Chinese patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:719-722.

- Laurberg G, Geiger JM, Hjorth N, et al. Treatment of lichen planus with acitretin. a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 65 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:434-437.

Imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The indications for imatinib have expanded since its initial approval. It is increasingly important that dermatologists recognize adverse cutaneous manifestations associated with imatinib and are aware of their management and outcomes to avoid unnecessarily discontinuing a potentially lifesaving medication.

Adverse cutaneous manifestations in response to imatinib are not infrequent, accounting for 7% to 21% of all side effects.1 The most frequent cutaneous manifestations of imatinib are dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, and photosensitivity rash, respectively.1 Other less common manifestations include exfoliative dermatitis, nail disorders, psoriasis, folliculitis, hypotrichosis, urticaria, petechiae, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

We report a case of imatinib-induced lichenoid drug eruption (LDE), a rare cutaneous side effect of imatinib use, along with a review of the literature.

Case Report

An 86-year-old man with a history of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and myelodysplastic syndrome presented with diffuse hyperpigmented skin lesions on the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip of 2 weeks’ duration. He had been taking imatinib 400 mg once daily for 5 months for GIST. Although the oncologist stopped the medication 2 weeks prior, the lesions were persistent and gradually expanded to involve the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip. He denied any pain or pruritus. Physical examination revealed multiple ill-defined, brown to violaceous, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk (Figures 1A and 1B), arms, and legs (Figure 1C), as well as violaceous to erythematous patches on the mucosal aspect of the lower lip (Figure 2). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the chest and back, which revealed an atrophic epidermis, lichenoid infiltration, and multiple melanophages in the upper dermis consistent with LDE (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Therefore, based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of imatinib-induced LDE was made. He was treated with clobetasol ointment twice daily for 3 weeks with some improvement. His GIST was stable on follow-up computed tomography 3 months after presentation, and imatinib was resumed 1 month later with continued rash that was stable with topical corticosteroid treatment.

Comment

In addition to CML, imatinib has been approved for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and GIST. Moreover, off-label use of imatinib for various other tyrosine kinase–positive cancers and rheumatologic conditions have been documented.2,3 With the expanding use of imatinib, there will be more occasions for dermatologists to encounter cutaneous manifestations associated with its use.

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms imatinib mesylate lichenoid drug, there have been few case reports of LDE associated with imatinib in the literature (eTable).4-24 Compared to classic LDE, imatinib-induced LDE has a few characteristic findings. Classic LDE frequently spares the oral mucosa and genitalia, but imatinib-induced LDE with manifestations on the oral mucosa and genitalia as well as cutaneous eruptions have been reported.4-9 In fact, the first known case of imatinib-induced LDE was an oral eruption in a patient with CML.4 In patients with oral involvement, lesions have been described as lacy reticular macules and violaceous papules, erosions, and ulcers.4,5,12 Interestingly, of those cases manifesting as concomitant oral and cutaneous LDE, the oral eruptions recurred more frequently, with 3 of 12 patients having recurrence of oral lesions after the cutaneous manifestations resolved.8,16 Genital manifestations of imatinib-induced LDE were much less common.9,11

To date, subsequent reports of imatinib-induced LDE have documented skin manifestations consistent with classic LDE occurring in a diffuse, bilateral, photodistributed pattern.10,15,16 One case presented with diffuse hyperpigmentation associated with LDE in a Japanese patient.20 The authors suggested this finding may be more prominent in patients with skin of color,20 which is consistent with the current case. Nail findings such as subungual hyperkeratosis and longitudinal ridging also have been reported.9,11

The latency period between initiation of imat-inib and onset of LDE generally ranges from 1 to 12 months, with onset most commonly occurring between 2 to 5 months or with dosage increase (eTable). Imatinib-induced LDE primarily has been documented with a 400-mg dose, with 1 case of a 600-mg dose and 1 case of an 800-mg dose, which suggests dose dependency. Furthermore, reports exist of several patients responding well to dose reduction with subsequent recurrence on dose reescalation.13,15

Historically, LDE resolves with discontinuation of the drug after a few weeks to months. When discontinuation of imatinib is unfavorable or patients report symptoms including severe pruritus or pain, treatment should be considered. Topical or oral corticosteroids can be used to treat imatinib-induced LDE, similar to lichen planus. When oral corticosteroids are contraindicated (eg, due to poor patient tolerance), oral acitretin at 25 to 35 mg once daily for 6 to 12 weeks has been reported as an alternative treatment.25

In the majority of cases of imatinib-induced LDE, it was undesirable to stop imatinib (eTable). Notably, in half the reported cases, imatinib was able to be continued and patients were treated symptomatically with either oral and/or topical steroids and/or acitretin with complete remission or tolerable recurrences. Dalmau et al9 reported 3 patients who responded poorly to topical and oral steroids and were subsequently treated with acitretin 25 mg once daily; 2 of 3 patients responded favorably to treatment and imatinib was able to be continued. In the current case imatinib initially helped, but because his rash was relatively asymptomatic, imatinib was restarted with control of rash with topical steroids. He developed some pancytopenia, which required intermittent stoppage of the imatinib.

Conclusion

We present a case of imatinib-induced cutaneous and oral LDE in a patient with GIST. Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids all may be reasonable treatment options if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient. If these therapies fail and the eruption is extensive or intolerable, dosage adjustment is another option to consider before discontinuation of imatinib.

Imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The indications for imatinib have expanded since its initial approval. It is increasingly important that dermatologists recognize adverse cutaneous manifestations associated with imatinib and are aware of their management and outcomes to avoid unnecessarily discontinuing a potentially lifesaving medication.

Adverse cutaneous manifestations in response to imatinib are not infrequent, accounting for 7% to 21% of all side effects.1 The most frequent cutaneous manifestations of imatinib are dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, and photosensitivity rash, respectively.1 Other less common manifestations include exfoliative dermatitis, nail disorders, psoriasis, folliculitis, hypotrichosis, urticaria, petechiae, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

We report a case of imatinib-induced lichenoid drug eruption (LDE), a rare cutaneous side effect of imatinib use, along with a review of the literature.

Case Report

An 86-year-old man with a history of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and myelodysplastic syndrome presented with diffuse hyperpigmented skin lesions on the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip of 2 weeks’ duration. He had been taking imatinib 400 mg once daily for 5 months for GIST. Although the oncologist stopped the medication 2 weeks prior, the lesions were persistent and gradually expanded to involve the trunk, arms, legs, and lower lip. He denied any pain or pruritus. Physical examination revealed multiple ill-defined, brown to violaceous, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk (Figures 1A and 1B), arms, and legs (Figure 1C), as well as violaceous to erythematous patches on the mucosal aspect of the lower lip (Figure 2). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed from the chest and back, which revealed an atrophic epidermis, lichenoid infiltration, and multiple melanophages in the upper dermis consistent with LDE (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Therefore, based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of imatinib-induced LDE was made. He was treated with clobetasol ointment twice daily for 3 weeks with some improvement. His GIST was stable on follow-up computed tomography 3 months after presentation, and imatinib was resumed 1 month later with continued rash that was stable with topical corticosteroid treatment.

Comment

In addition to CML, imatinib has been approved for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and GIST. Moreover, off-label use of imatinib for various other tyrosine kinase–positive cancers and rheumatologic conditions have been documented.2,3 With the expanding use of imatinib, there will be more occasions for dermatologists to encounter cutaneous manifestations associated with its use.

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms imatinib mesylate lichenoid drug, there have been few case reports of LDE associated with imatinib in the literature (eTable).4-24 Compared to classic LDE, imatinib-induced LDE has a few characteristic findings. Classic LDE frequently spares the oral mucosa and genitalia, but imatinib-induced LDE with manifestations on the oral mucosa and genitalia as well as cutaneous eruptions have been reported.4-9 In fact, the first known case of imatinib-induced LDE was an oral eruption in a patient with CML.4 In patients with oral involvement, lesions have been described as lacy reticular macules and violaceous papules, erosions, and ulcers.4,5,12 Interestingly, of those cases manifesting as concomitant oral and cutaneous LDE, the oral eruptions recurred more frequently, with 3 of 12 patients having recurrence of oral lesions after the cutaneous manifestations resolved.8,16 Genital manifestations of imatinib-induced LDE were much less common.9,11

To date, subsequent reports of imatinib-induced LDE have documented skin manifestations consistent with classic LDE occurring in a diffuse, bilateral, photodistributed pattern.10,15,16 One case presented with diffuse hyperpigmentation associated with LDE in a Japanese patient.20 The authors suggested this finding may be more prominent in patients with skin of color,20 which is consistent with the current case. Nail findings such as subungual hyperkeratosis and longitudinal ridging also have been reported.9,11

The latency period between initiation of imat-inib and onset of LDE generally ranges from 1 to 12 months, with onset most commonly occurring between 2 to 5 months or with dosage increase (eTable). Imatinib-induced LDE primarily has been documented with a 400-mg dose, with 1 case of a 600-mg dose and 1 case of an 800-mg dose, which suggests dose dependency. Furthermore, reports exist of several patients responding well to dose reduction with subsequent recurrence on dose reescalation.13,15

Historically, LDE resolves with discontinuation of the drug after a few weeks to months. When discontinuation of imatinib is unfavorable or patients report symptoms including severe pruritus or pain, treatment should be considered. Topical or oral corticosteroids can be used to treat imatinib-induced LDE, similar to lichen planus. When oral corticosteroids are contraindicated (eg, due to poor patient tolerance), oral acitretin at 25 to 35 mg once daily for 6 to 12 weeks has been reported as an alternative treatment.25

In the majority of cases of imatinib-induced LDE, it was undesirable to stop imatinib (eTable). Notably, in half the reported cases, imatinib was able to be continued and patients were treated symptomatically with either oral and/or topical steroids and/or acitretin with complete remission or tolerable recurrences. Dalmau et al9 reported 3 patients who responded poorly to topical and oral steroids and were subsequently treated with acitretin 25 mg once daily; 2 of 3 patients responded favorably to treatment and imatinib was able to be continued. In the current case imatinib initially helped, but because his rash was relatively asymptomatic, imatinib was restarted with control of rash with topical steroids. He developed some pancytopenia, which required intermittent stoppage of the imatinib.

Conclusion

We present a case of imatinib-induced cutaneous and oral LDE in a patient with GIST. Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids all may be reasonable treatment options if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient. If these therapies fail and the eruption is extensive or intolerable, dosage adjustment is another option to consider before discontinuation of imatinib.

- Scheinfeld N. Imatinib mesylate and dermatology part 2: a review of the cutaneous side effects of imatinib mesylate. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:228-231.

- Kim H, Kim NH, Kang HJ, et al. Successful long-term use of imatinib mesylate in pediatric patients with sclerodermatous chronic GVHD. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:910-912.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Doussau A, et al. Imatinib mesylate in scleroderma-associated diffuse skin fibrosis: a phase II multicentre randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1138-1144.

- Lim DS, Muir J. Oral lichenoid reaction to imatinib (STI 571, gleevec). Dermatology. 2002;205:169-171.

- Ena P, Chiarolini F, Siddi GM, et al. Oral lichenoid eruption secondary to imatinib (glivec). J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:253-255.

- Roux C, Boisseau-Garsaud AM, Saint-Cyr I, et al. Lichenoid cutaneous reaction to imatinib. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:571-573.

- Prabhash K, Doval DC. Lichenoid eruption due to imat-inib. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:287-288.

- Pascual JC, Matarredona J, Miralles J, et al. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction secondary to imatinib: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1471-1473.

- Dalmau J, Peramiquel L, Puig L, et al. Imatinib-associated lichenoid eruption: acitretin treatment allows maintained antineoplastic effect. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1213-1216.

- Chan CY, Browning J, Smith-Zagone MJ, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid dermatitis associated with imatinib mesylate. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:29.

- Wahiduzzaman M, Pubalan M. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction with nail changes secondary to imatinib: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Basso FG, Boer CC, Correa ME, et al. Skin and oral lesions associated to imatinib mesylate therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:465-468.

- Kawakami T, Kawanabe T, Soma Y. Cutaneous lichenoid eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Japanese patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:325-326.

- Sendagorta E, Herranz P, Feito M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption related to imatinib: report of a new case and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E315-E316.

- Kuraishi N, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with palmoplantar hyperkeratosis due to imatinib mesylate: a case report and a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:73-76.

- Brazzelli V, Muzio F, Manna G, et al. Photo-induced dermatitis and oral lichenoid reaction in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient treated with imatinib mesylate. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:2-5.

- Ghosh SK. Generalized lichenoid drug eruption associated with imatinib mesylate therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:388-392.

- Lee J, Chung J, Jung M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption after low-dose imatinib mesylate therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:500-502.

- Machaczka M, Gossart M. Multiple skin lesions caused by imatinib mesylate treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:251-252.

- Kagimoto Y, Mizuashi M, Kikuchi K, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with hyperpigmentation caused by imatinib mesylate [published online June 20, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E161-E162.

- Arshdeep, De D, Malhotra P, et al. Imatinib mesylate-induced severe lichenoid rash. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:93-95.

- Lau YM, Lam YK, Leung KH, et al. Trachyonychia in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib mesylate. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:464.e2.

- Bhatia A, Kanish B, Chaudhary P. Lichenoid drug eruption due to imatinib mesylate. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5:68-69.

- Luo JR, Xiang XJ, Xiong JP. Lichenoid drug eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Chinese patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:719-722.

- Laurberg G, Geiger JM, Hjorth N, et al. Treatment of lichen planus with acitretin. a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 65 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:434-437.

- Scheinfeld N. Imatinib mesylate and dermatology part 2: a review of the cutaneous side effects of imatinib mesylate. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:228-231.

- Kim H, Kim NH, Kang HJ, et al. Successful long-term use of imatinib mesylate in pediatric patients with sclerodermatous chronic GVHD. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:910-912.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Doussau A, et al. Imatinib mesylate in scleroderma-associated diffuse skin fibrosis: a phase II multicentre randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1138-1144.

- Lim DS, Muir J. Oral lichenoid reaction to imatinib (STI 571, gleevec). Dermatology. 2002;205:169-171.

- Ena P, Chiarolini F, Siddi GM, et al. Oral lichenoid eruption secondary to imatinib (glivec). J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:253-255.

- Roux C, Boisseau-Garsaud AM, Saint-Cyr I, et al. Lichenoid cutaneous reaction to imatinib. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:571-573.

- Prabhash K, Doval DC. Lichenoid eruption due to imat-inib. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:287-288.

- Pascual JC, Matarredona J, Miralles J, et al. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction secondary to imatinib: report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1471-1473.

- Dalmau J, Peramiquel L, Puig L, et al. Imatinib-associated lichenoid eruption: acitretin treatment allows maintained antineoplastic effect. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1213-1216.

- Chan CY, Browning J, Smith-Zagone MJ, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid dermatitis associated with imatinib mesylate. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:29.

- Wahiduzzaman M, Pubalan M. Oral and cutaneous lichenoid reaction with nail changes secondary to imatinib: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Basso FG, Boer CC, Correa ME, et al. Skin and oral lesions associated to imatinib mesylate therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:465-468.

- Kawakami T, Kawanabe T, Soma Y. Cutaneous lichenoid eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Japanese patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:325-326.

- Sendagorta E, Herranz P, Feito M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption related to imatinib: report of a new case and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E315-E316.

- Kuraishi N, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with palmoplantar hyperkeratosis due to imatinib mesylate: a case report and a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:73-76.

- Brazzelli V, Muzio F, Manna G, et al. Photo-induced dermatitis and oral lichenoid reaction in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient treated with imatinib mesylate. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:2-5.

- Ghosh SK. Generalized lichenoid drug eruption associated with imatinib mesylate therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:388-392.

- Lee J, Chung J, Jung M, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption after low-dose imatinib mesylate therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:500-502.

- Machaczka M, Gossart M. Multiple skin lesions caused by imatinib mesylate treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:251-252.

- Kagimoto Y, Mizuashi M, Kikuchi K, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption with hyperpigmentation caused by imatinib mesylate [published online June 20, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E161-E162.

- Arshdeep, De D, Malhotra P, et al. Imatinib mesylate-induced severe lichenoid rash. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:93-95.

- Lau YM, Lam YK, Leung KH, et al. Trachyonychia in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia after imatinib mesylate. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:464.e2.

- Bhatia A, Kanish B, Chaudhary P. Lichenoid drug eruption due to imatinib mesylate. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5:68-69.

- Luo JR, Xiang XJ, Xiong JP. Lichenoid drug eruption caused by imatinib mesylate in a Chinese patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:719-722.

- Laurberg G, Geiger JM, Hjorth N, et al. Treatment of lichen planus with acitretin. a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 65 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:434-437.

Practice Points

- Imatinib mesylate can cause cutaneous adverse reactions including dry skin, alopecia, facial edema, photosensitivity rash, and lichenoid drug eruption (LDE).

- Topical corticosteroids, oral acitretin, and oral steroids may be reasonable treatment options for imatinib-induced LDE if discontinuing imatinib is not possible in a symptomatic patient.

Diffuse Crusting of the Skin

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

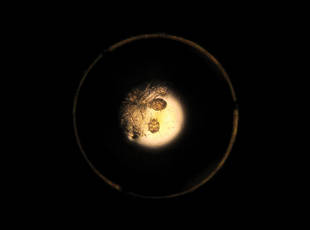

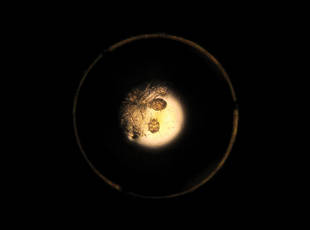

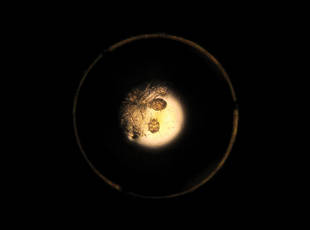

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|

|

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|

|

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|

|

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

An 82-year-old white man who resided in the northeastern United States was admitted to the hospital for weakness. He was evaluated for diffuse crusting of the skin including the face. The patient reported a history of minimally itchy, generalized crusts of 10 years’ duration. He lived alone with one cat. His medications included fluticasone furoate, terazosin, and levothyroxine sodium. Human immunodeficiency virus screening was negative. A scraping was taken from one of the thick crusts within an interdigital web space.