User login

VA Awards Grants to Support Adaptive Sports

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is awarding $15.9 million in grants to fund adaptive sports, recreational activities, and equine therapy for > 15,000 veterans and service members living with disabilities.

Marine Corps veteran Jataya Taylor — who competed in wheelchair fencing at the 2024 Paralympics — experienced mental health symptoms until she began participating in adaptive sports through an organization supported by the VA Adaptive Sports Grant Program.

“Getting involved in adaptive sports was a saving grace for me,” Taylor said. “Participating in these programs got me on the bike to start with, then got me climbing, and eventually it became an important part of my mental health to participate. I found my people. I found my new network of friends.”

Adaptive sports, which are customized to fit the needs of veterans with disabilities, include paralympic sports, archery, cycling, skiing, hunting, rock climbing, and sky diving. Mike Gooler, another Marine Corps veteran, praised the Adaptive Sports Center’s facilities in Crested Butte, Colorado, calling it “nothing short of amazing.”

“[S]ki therapy has been instrumental in helping me navigate through my experiences and injuries,” Gooler said. “Skiing provides me with sense of freedom and empowerment … and having my family by my side, witnessing my progress and sharing the joy of skiing, was truly special.”

The grant program is facilitated and managed by the National Veterans Sports Programs and Special Events Office and will provide grants to 91 national, regional, and community-based programs for fiscal year 2024 across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico.

“These grants give veterans life-changing opportunities,” Secretary of VA Denis McDonough said. “We know adaptive sports and recreational activities can be transformational for veterans living with disabilities, improving their overall physical and mental health, and also giving them important community with fellow heroes who served.”

Information about the awardees and details of the program are available at www.va.gov/adaptivesports and on Facebook at Sports4Vets.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is awarding $15.9 million in grants to fund adaptive sports, recreational activities, and equine therapy for > 15,000 veterans and service members living with disabilities.

Marine Corps veteran Jataya Taylor — who competed in wheelchair fencing at the 2024 Paralympics — experienced mental health symptoms until she began participating in adaptive sports through an organization supported by the VA Adaptive Sports Grant Program.

“Getting involved in adaptive sports was a saving grace for me,” Taylor said. “Participating in these programs got me on the bike to start with, then got me climbing, and eventually it became an important part of my mental health to participate. I found my people. I found my new network of friends.”

Adaptive sports, which are customized to fit the needs of veterans with disabilities, include paralympic sports, archery, cycling, skiing, hunting, rock climbing, and sky diving. Mike Gooler, another Marine Corps veteran, praised the Adaptive Sports Center’s facilities in Crested Butte, Colorado, calling it “nothing short of amazing.”

“[S]ki therapy has been instrumental in helping me navigate through my experiences and injuries,” Gooler said. “Skiing provides me with sense of freedom and empowerment … and having my family by my side, witnessing my progress and sharing the joy of skiing, was truly special.”

The grant program is facilitated and managed by the National Veterans Sports Programs and Special Events Office and will provide grants to 91 national, regional, and community-based programs for fiscal year 2024 across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico.

“These grants give veterans life-changing opportunities,” Secretary of VA Denis McDonough said. “We know adaptive sports and recreational activities can be transformational for veterans living with disabilities, improving their overall physical and mental health, and also giving them important community with fellow heroes who served.”

Information about the awardees and details of the program are available at www.va.gov/adaptivesports and on Facebook at Sports4Vets.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is awarding $15.9 million in grants to fund adaptive sports, recreational activities, and equine therapy for > 15,000 veterans and service members living with disabilities.

Marine Corps veteran Jataya Taylor — who competed in wheelchair fencing at the 2024 Paralympics — experienced mental health symptoms until she began participating in adaptive sports through an organization supported by the VA Adaptive Sports Grant Program.

“Getting involved in adaptive sports was a saving grace for me,” Taylor said. “Participating in these programs got me on the bike to start with, then got me climbing, and eventually it became an important part of my mental health to participate. I found my people. I found my new network of friends.”

Adaptive sports, which are customized to fit the needs of veterans with disabilities, include paralympic sports, archery, cycling, skiing, hunting, rock climbing, and sky diving. Mike Gooler, another Marine Corps veteran, praised the Adaptive Sports Center’s facilities in Crested Butte, Colorado, calling it “nothing short of amazing.”

“[S]ki therapy has been instrumental in helping me navigate through my experiences and injuries,” Gooler said. “Skiing provides me with sense of freedom and empowerment … and having my family by my side, witnessing my progress and sharing the joy of skiing, was truly special.”

The grant program is facilitated and managed by the National Veterans Sports Programs and Special Events Office and will provide grants to 91 national, regional, and community-based programs for fiscal year 2024 across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico.

“These grants give veterans life-changing opportunities,” Secretary of VA Denis McDonough said. “We know adaptive sports and recreational activities can be transformational for veterans living with disabilities, improving their overall physical and mental health, and also giving them important community with fellow heroes who served.”

Information about the awardees and details of the program are available at www.va.gov/adaptivesports and on Facebook at Sports4Vets.

VHA Support for Home Health Agency Staff and Patients During Natural Disasters

As large-scale natural disasters become more common, health care coalitions and the engagement of health systems with local, state, and federal public health departments have effectively bolstered communities’ resilience via collective sharing and distribution of resources.1 These resources may include supplies and the dissemination of emergency information, education, and training.2 The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that larger health care systems including hospital networks and nursing homes are better connected to health care coalition resources than smaller, independent systems, such as community home health agencies.3 This leaves some organizations on their own to meet requirements that maintain continuity of care and support their patients and staff throughout a natural disaster.

Home health care workers play important roles in the care of older adults.4 Older adults experience high levels of disability and comorbidities that put them at risk during emergencies; they often require support from paid, family, and neighborhood caregivers to live independently.5 More than 9.3 million US adults receive paid care from 2.6 million home health care workers (eg, home health aides and personal care assistants).6 Many of these individuals are hired through small independent home health agencies (HHAs), while others may work directly for an individual. When neighborhood resources and family caregiving are disrupted during emergencies, the critical services these workers administer become even more essential to ensuring continued access to medical care and social services.

The importance of these services was underscored by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2017 inclusion of HHAs in federal emergency preparedness guidelines.7,8 The fractured and decentralized nature of the home health care industry means many HHAs struggle to maintain continuous care during emergencies and protect their staff. HHAs, and health care workers in the home, are often isolated, under-resourced, and disconnected from broader emergency planning efforts. Additionally, home care jobs are largely part-time, unstable, and low paying, making the workers themselves vulnerable during emergencies.3,9-13

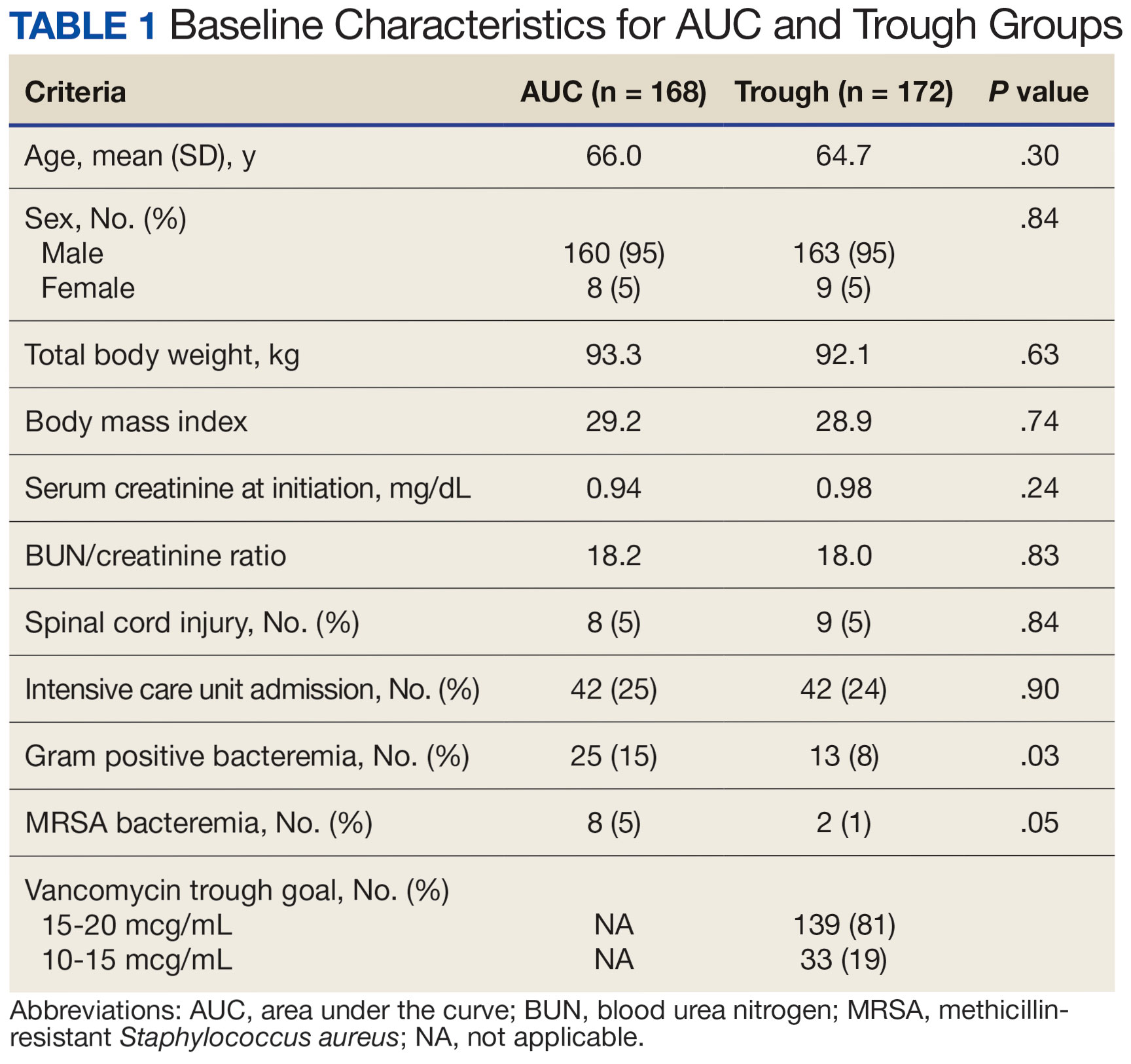

This is a significant issue for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which annually purchases 10.5 million home health care worker visits for 150,000 veterans from community-based HHAs to enable those individuals to live independently. Figure 1 illustrates the existing structure of directly provided and contracted VHA services for community-dwelling veterans, highlighting the circle of care around the veteran.8,9 Home health care workers anchored health care teams during the COVID-19 pandemic, observing and reporting on patients’ well-being to family caregivers, primary care practitioners, and HHAs. They also provided critical emotional support and companionship to patients isolated from family and friends.9 These workers also exposed themselves and their families to considerable risk and often lacked the protection afforded by personal protective equipment (PPE) in accordance with infection prevention guidance.3,12

Abbreviations: HBPC, home based primary care; HHA, home health agency; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

aAdapted with permission from Wyte-Lake and Franzosa.8,9

Through a combination of its national and local health care networks, the VHA has a robust and well-positioned emergency infrastructure to supportcommunity-dwelling older adults during disasters.14 This network is supported by the VHA Office of Emergency Management, which shares resources and guidance with local emergency managers at each facility as well as individual programs such as the VHA Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) program, which provides 38,000 seriously ill veterans with home medical visits.15 Working closely with their local and national hospital networks and emergency managers, individual VHA HBPC programs were able to maintain the safety of staff and continuity of care for patients enrolled in HBPC by rapidly administering COVID-19 vaccines to patients, caregivers, and staff, and providing emergency assistance during the 2017 hurricane season.16,17 These efforts were successful because HBPC practitioners and their patients, had access to a level of emergency-related information, resources, and technology that are often out of reach for individual community-based health care practitioners (HCPs). The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) also supports local communities through its Fourth Mission, which provides emergency resources to non-VHA health care facilities (ie, hospitals and nursing homes) during national emergencies and natural disasters.17 Although there has been an expansion in the definition of shared resources, such as extending behavioral health support to local communities, the VHA has not historically provided these resources to HHAs.14

This study examines opportunities to leverage VHA emergency management resources to support contracted HHAs and inform other large health system emergency planning efforts. The findings from the exploratory phase are described in this article. We interviewed VHA emergency managers, HBPC and VA staff who coordinate home health care worker services, as well as administrators at contracted HHAs within a Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN). These findings will inform the second (single-site pilot study) and third (feasibility study) phases. Our intent was to (1) better understand the relationships between VA medical centers (VAMCs) and their contracted HHAs; (2) identify existing VHA emergency protocols to support community-dwelling older adults; and (3) determine opportunities to build on existing infrastructure and relationships to better support contracted HHAs and their staff in emergencies.

Methods

The 18 VISNs act as regional systems of care that are loosely connected to better meet local health needs and maximize access to care. This study was conducted at 6 of 9 VAMCs within VISN 2, the New York/New Jersey VHA Health Care Network.18 VAMCs that serve urban, rural, and mixed urban/rural catchment areas were included.

Each VAMC has an emergency management program led by an emergency manager, an HBPC program led by a program director and medical director, and a community care or purchased care office that has a liaison who manages contracted home health care worker services. The studyfocused on HBPC programs because they are most likely to interact with veterans’ home health care workers in the home and care for community-dwelling veterans during emergencies. Each VHA also contracts with a series of local HHAs that generally have a dedicated staff member who interfaces with the VHA liaison. Our goal was to interview ≥ 1 emergency manager, ≥ 1 HBPC team member, ≥ 1 community care staff person, and ≥ 1 contracted home health agency administrator at each site to gain multiple perspectives from the range of HCPs serving veterans in the community.

Recruitment and Data Collection

The 6 sites were selected in consultation with VISN 2 leadership for their strong HBPC and emergency management programs. To recruit respondents, we contacted VISN and VAMC leads and used our professional networks to identify a sample of multidisciplinary individuals who represent both community care and HBPC programs who were contacted via email.

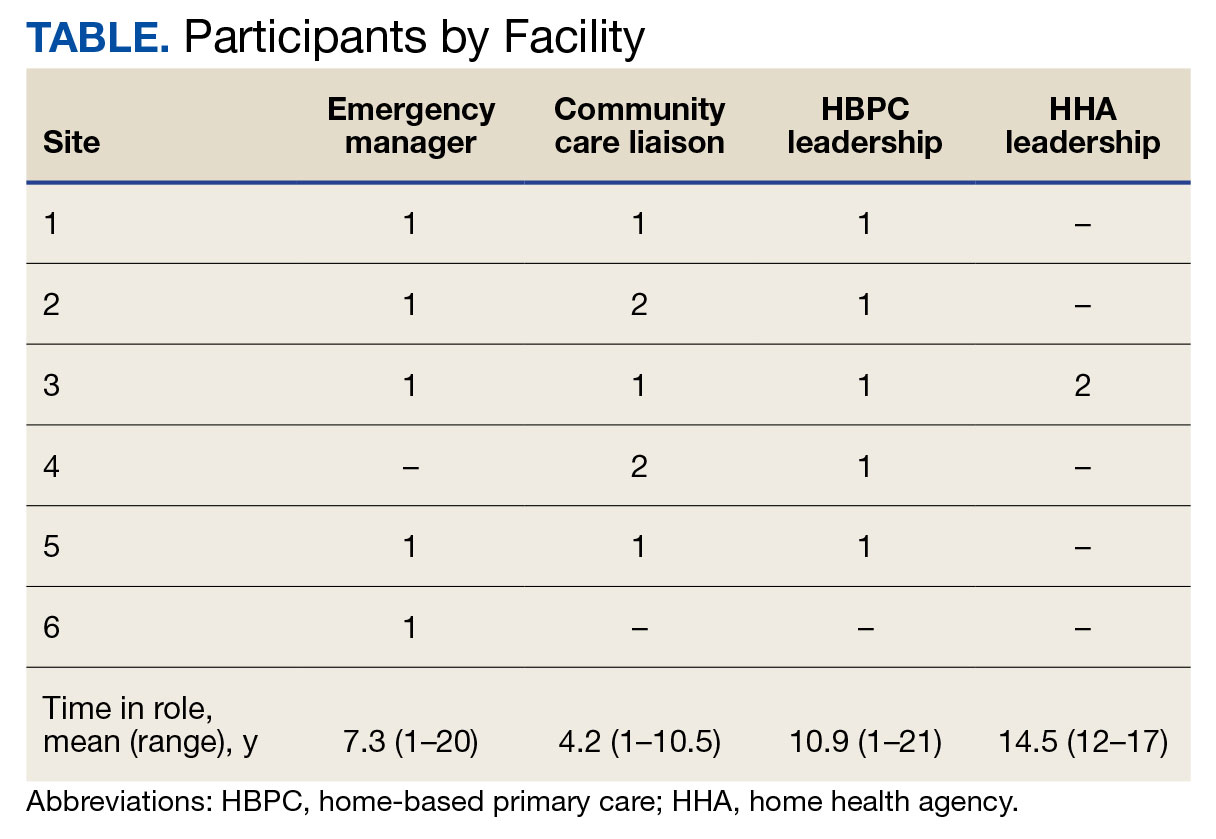

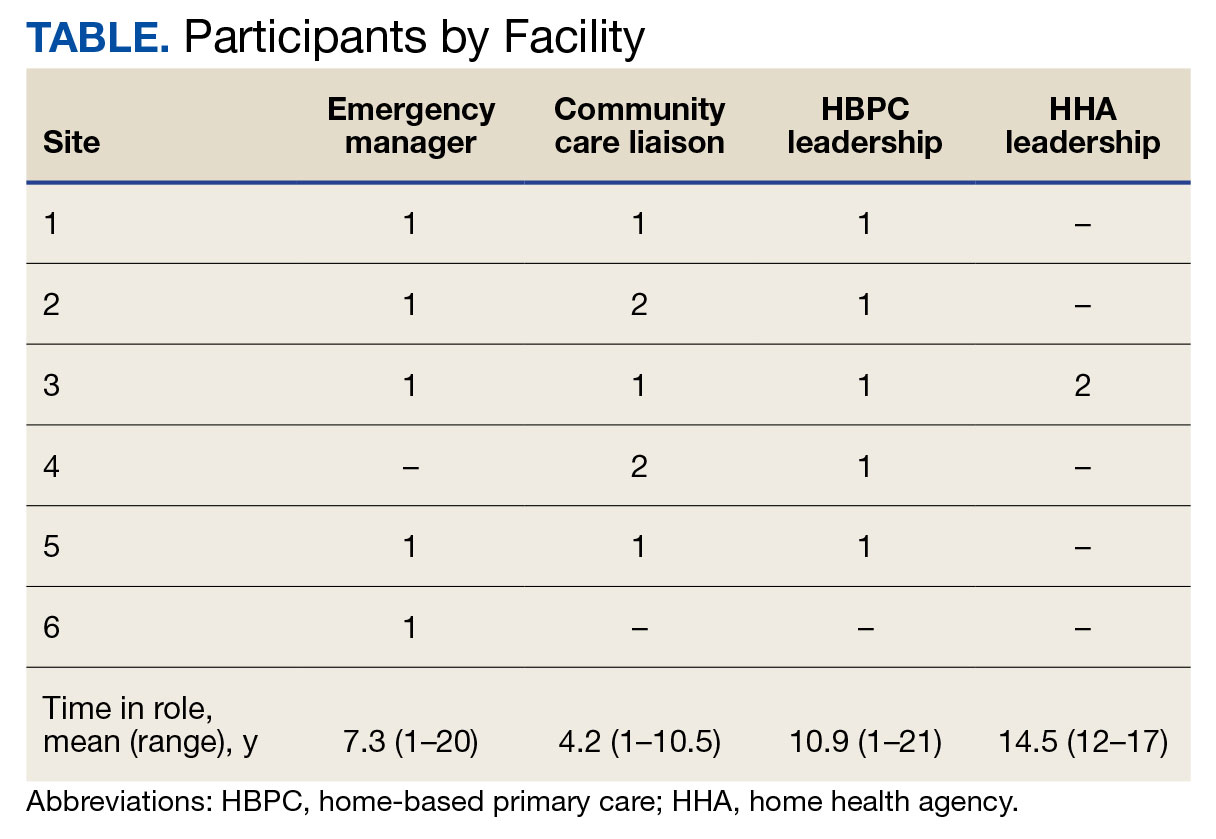

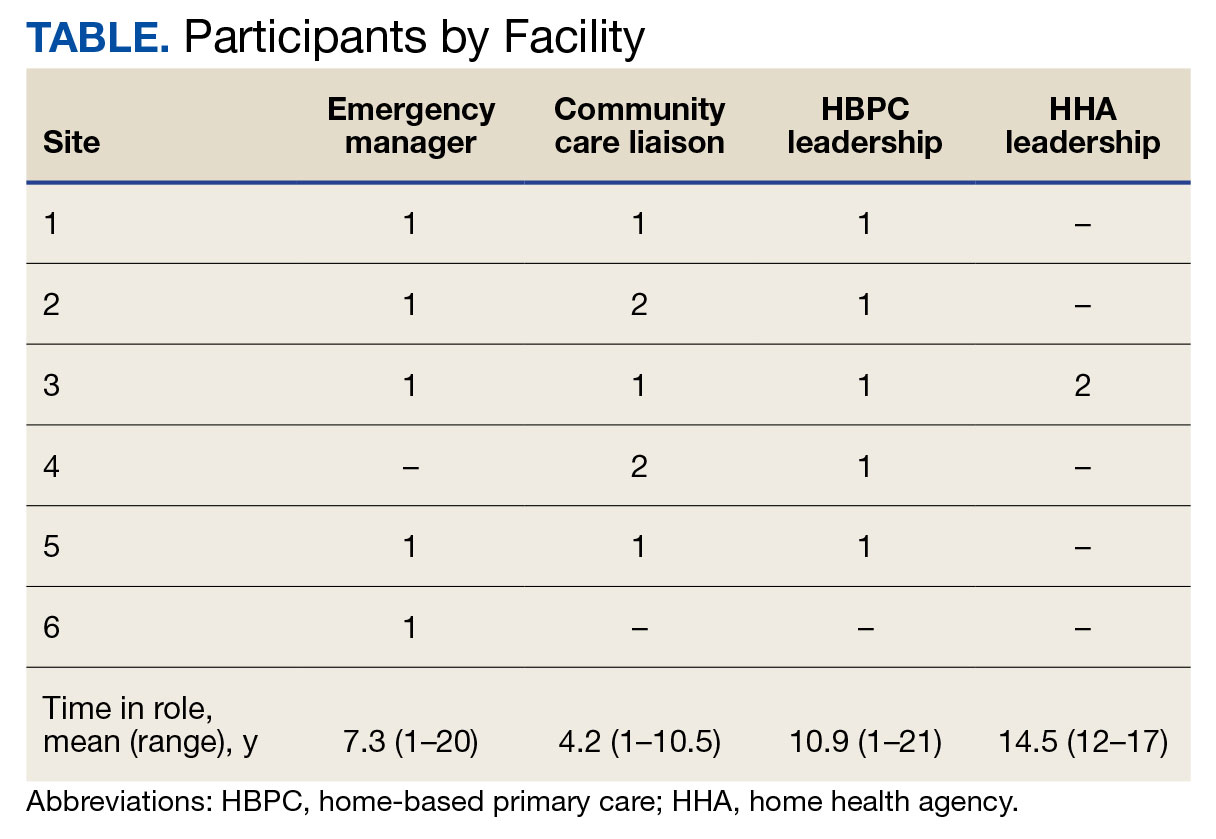

Since each VAMC is organized differently, we utilized a snowball sampling approach to identify the appropriate contacts.19 At the completion of each interview, we asked the participant to suggest additional contacts and introduce us to any remaining stakeholders (eg, the emergency manager) at that site or colleagues at other VISN facilities. Because roles vary among VAMCs, we contacted the person who most closely resembled the identified role and asked them to direct us to a more appropriate contact, if necessary. We asked community care managers to identify 1 to 2 agencies serving the highest volume of patients who are veterans at their site and requested interviews with those liaisons. This resulted in the recruitment of key stakeholders from 4 teams across the 6 sites (Table).

A semistructured interview guide was jointly developed based on constructs of interest, including relationships within VAMCs and between VAMCs and HHAs; existing emergency protocols and experience during disasters; and suggestions and opportunities for supporting agencies during emergencies and potential barriers. Two researchers (TWL and EF) who were trained in qualitative methods jointly conducted interviews using the interview guide, with 1 researcher leading and another taking notes and asking clarifying questions.

Interviews were conducted virtually via Microsoft Teams with respondents at their work locations between September 2022 and January 2023. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed and 2 authors (TWL and ESO) reviewed transcripts for accuracy. Interviews averaged 47 minutes in length (range, 20-59).

The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt by institutional review boards at the James J. Peters VAMC and Greater Los Angeles VAMC. We asked participants for verbal consent to participate and preserved their confidentiality.

Analysis

Data were analyzed via an inductive approach, which involves drawing salient themes rather than imposing preconceived theories.20 Three researchers (TWL, EF, and ES) listened to and discussed 2 staff interviews and tagged text with specific codes (eg, communication between the VHA and HHA, internal communication, and barriers to case fulfillment) so the team could selectively return to the interview text for deeper analysis, allowing for the development of a final codebook. The project team synthesized the findings to identify higher-level themes, drawing comparisons across and within the respondent groups, including within and between health care systems. Throughout the analysis, we maintained analytic memos, documented discussions, and engaged in analyst triangulation to ensure trustworthiness.21,22 To ensure the analysis accurately reflected the participants’ understanding, we held 2 virtual member-checking sessions with participants to share preliminary findings and conclusions and solicit feedback. Analysis was conducted using ATLAS.ti version 20.

Results

VHA-based participants described internal emergency management systems that are deployed during a disaster to support patients and staff. Agency participants described their own internal emergency management protocols. Respondents discussed how and when the 2 intersected, as well as opportunities for future mutual support. The analysis identified several themes: (1) relationships between VAMC teams; (2) relationships between VHA and HHAs; (3) VHA and agencies responses during emergencies; (4) receptivity and opportunities for extending VHA resources into the community; and (5) barriers and facilitators to deeper engagement.

Relationships Within VHA (n = 17)

Staff at all VHA sites described close relationships between the internal emergency management and HBPC teams. HBPC teams identified patients who were most at risk during emergencies to triage those with the highest medical needs (eg, patients dependent on home infusion, oxygen, or electronic medical devices) and worked alongside emergency managers to develop plans to continue care during an emergency. HBPC representatives were part of their facilities’ local emergency response committees. Due to this close collaboration, VHA emergency managers were familiar with the needs of homebound veterans and caregivers. “I invite our [HBPC] program manager to attend [committee] meetings and … they’re part of the EOC [emergency operations center]," an emergency manager said. “We work together and I’m constantly in contact with that individual, especially during natural disasters and so forth, to ensure that everybody’s prepared in the community.”

On the other hand, community caremanagers—who described frequent interactions with HBPC teams, largely around coordinating and managing non-VHA home care services—were less likely to have direct relationships with their facility emergency managers. For example, when asked if they had a relationship with their emergency manager, a community care manager admitted, “I [only] know who he is.” They also did not report having structured protocols for veteran outreach during emergencies, “because all those veterans who are receiving [home health care worker] services also belong to a primary care team,” and considered the outreach to be the responsibility of the primary care team and HHA.

Relationships Between the VHA and HHAs (n = 17)

Communication between VAMCs and contracted agencies primarily went through community care managers, who described established long-term relationships with agency administrators. Communication was commonly restricted to operational activities, such as processing referrals and occasional troubleshooting. According to a community care manager most communication is “why haven’t you signed my orders?” There was a general sense from participants that communication was promptly answered, problems were addressed, and professional collegiality existed between the agencies as patients were referred and placed for services. One community care manager reported meeting with agencies regularly, noting, “I talk to them pretty much daily.”

If problems arose, community care managers described themselves as “the liaison” between agencies and VHA HCPs who ordered the referrals. This is particularly the case if the agency needed help finding a VHA clinician or addressing differences in care delivery protocols.

Responding During Emergencies (n = 19)

During emergencies, VHA and agency staff described following their own organization’s protocols and communicating with each other only on a case-by-case basis rather than through formal or systematic channels and had little knowledge of their counterpart’s emergency protocols. Beyond patient care, there was no evidence of information sharing between VHA and agency staff. Regarding sharing information with their local community, an HBPC Program Director said, “it’s almost like the VHA had become siloed” and operated on its own without engaging with community health systems or emergency managers.

Beyond the guidance provided by state departments of public health, HHAs described collaborating with other agencies in their network and relying on their informal professional network to manage the volume of information and updates they followed during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic. One agency administrator did not frequently communicate with VHA partners during the pandemic but explained that the local public health department helped work through challenges. However, “we realized pretty quickly they were overloaded and there was only so much they could do.” The agency administrator turned to a “sister agency” and local hospitals, noting, “Wherever you have connections in the field or in the industry, you know you’re going to reach out to people for guidance on policies and… protocol.”

Opportunities for Extending VHA Resources to the Community (n = 16)

All VHA emergency managers were receptive to extending support to community-based HCPS and, in some cases, felt strongly that they were an essential part of veterans’ care networks. Emergency managers offered examples for how they supportedcommunity-based HCPs, such as helping those in the VAMC medical foster home program develop and evaluate emergency plans. Many said they had not explicitly considered HHAs before (Appendix).

Emergency managers also described how supporting community-based HCPs could be considered within the scope of the VHA role and mission, specifically the Fourth Mission. “I think that we should be making our best effort to make sure that we’re also providing that same level [of protection] to the people taking care of the veteran [as our VHA staff],” an emergency manager said. “It’s our responsibility to provide the best for the staff that are going into those homes to take care of that patient.”

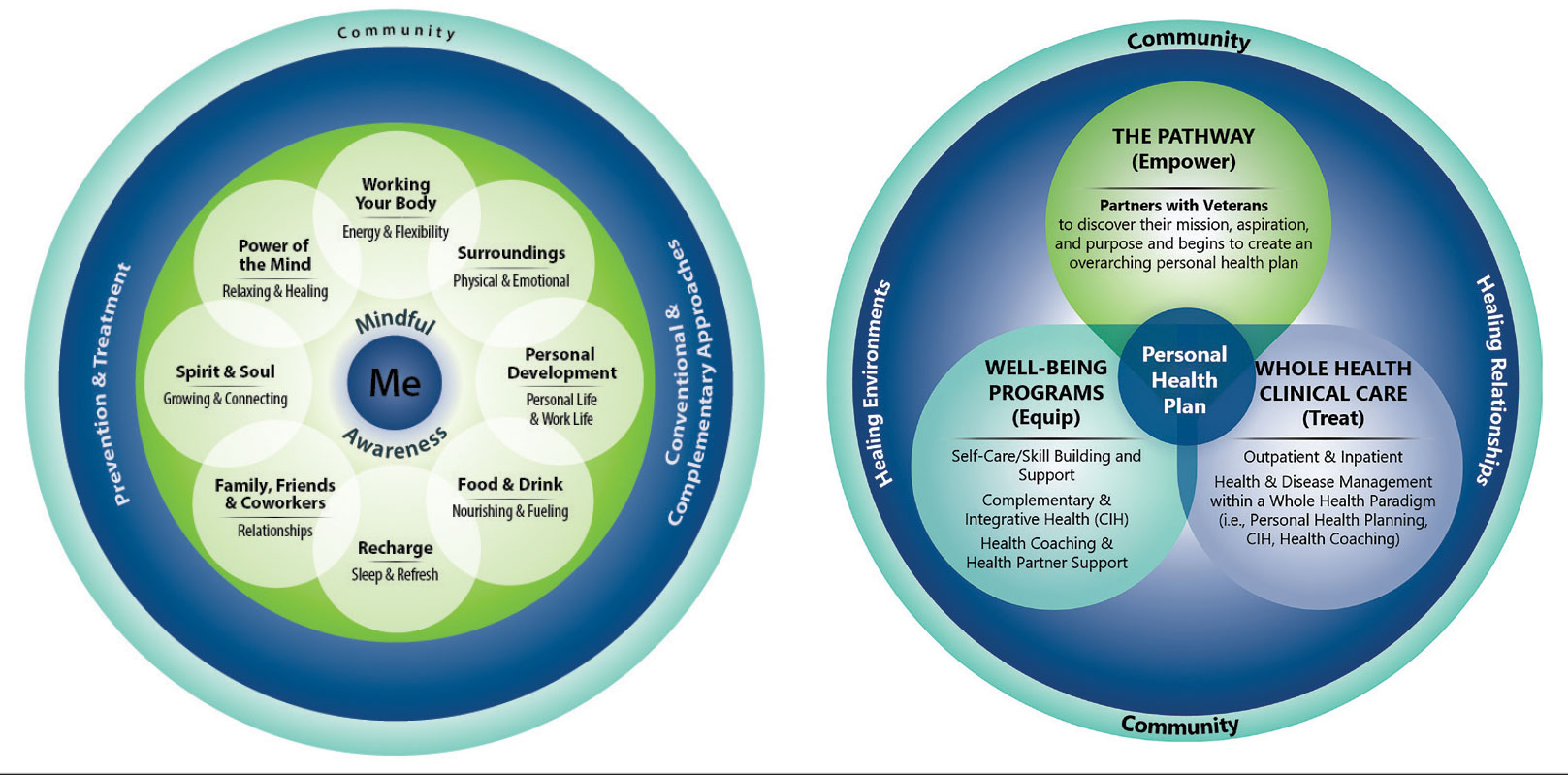

In many cases, emergency managers had already developed practical tools that could be easily shared outside the VHA, including weather alerts, trainings, emergency plan templates, and lists of community resources and shelters (Figure 2). A number of these examples built on existing communication channels. One emergency manager said that the extension of resources could be an opportunity to decrease the perceived isolation of home health care workers through regular

Abbreviations: PPE, personal protective equipment; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

On the agency side, participants noted that some HHAs could benefit more from support than others. While some agencies are well staffed and have good protocols and keep up to date, “There are smaller agencies, agencies that are starting up that may not have the resources to just disseminate all the information. Those are the agencies [that] could well benefit from the VHA,” an HBPC medical director explained. Agency administrators suggested several areas where they would welcome support, including a deeper understanding of available community resources and access to PPE for staff. Regarding informational resources, an administrator said, “Anytime we can get information, it’s good to have it come to you and not always have to go out searching for it.”

Barriers and Facilitators to Partnering With Community Agencies (n = 16)

A primary barrier regarding resource sharing was potential misalignment between each organization’s policies. HHAs followed state and federal public health guidelines, which sometimes differed from VHA policies. Given that agencies care for both VHA and non-VHA clients, questions also arose around how agencies would prioritize information from the VHA, if they were already receiving information from other sources. When asked about information sharing, both VHA staff and agencies agreed staff time to support any additional activities should be weighed against the value of the information gained.

Six participants also shared that education around emergency preparedness could be an opportunity to bridge gaps between VAMCs and their surrounding communities.

Two emergency managers noted the need to be sensitive in the way they engaged with partners, respecting and building on the work that agencies were already doing in this area to ensure VHA was seen as a trusted partner and resource rather than trying to impose new policies or rules on community-based HCPs. “I know that like all leadership in various organizations, there’s a little bit of bristling going on when other people try and tell them what to do,” an HBPC medical director said. “However, if it is established that as a sort of greater level like a state level or a federal level, that VHA can be a resource. I think that as long as that’s recognized by their own professional organizations within each state, then I think that that would be a tremendous advantage to many agencies.”

In terms of sharing physical resources, emergency managers raised concerns around potential liability, although they also acknowledged this issue was important enough to think about potential workarounds. As one emergency manager said, “I want to know that my PPE is not compromised in any way shape or form and that I am in charge of that PPE, so to rely upon going to a home and hoping that [the PPE] wasn’t compromised … would kind of make me a little uneasy.” This emergency manager suggested possible solutions, such as creating a sealed PPE package to give directly to an aide.

Discussion

As the prevalence of climate-related disasters increases, the need to ensure the safety and independence of older adults during emergencies grows more urgent. Health systems must think beyond the direct services they provide and consider the community resources upon which their patients rely. While relationships did not formally exist between VHA emergency managers and community home health HCPs in the sample analyzed in this article, there is precedent and interest in supporting contracted home health agencies caring for veterans in the community. Although not historically part of the VA Fourth Mission, creating a pipeline of support for contracted HHAs by leveraging existing relationships and resources can potentially strengthen its mission to protect older veterans in emergencies, help them age safely in place, and provide a model for health systems to collaborate with community-based HCPs around emergency planning and response (Figure 3).23

Existing research on the value of health care coalitions highlights the need for established and growing partnerships with a focus on ensuring they are value-added, which echoes concerns we heard in interviews.24 Investment in community partnerships not only includes sharing supplies but also relying on bidirectional support that can be a trusted form of timely information.1,25 The findings in this study exhibit strong communication practices within the VHA during periods of nonemergency and underscore the untapped value of the pre-existing relationship between VAMCs and their contracted HHAs as an area of potential growth for health care coalitions.

Sharing resources in a way that does not put new demands on partners contributes to the sustainability and value-added nature of coalitions. Examples include establishing new low-investment practices (ie, information sharing) that support capacity and compliance with existing requirements rather than create new responsibilities for either member of the coalition. The relationship between the VHA emergency managers and the VHA HBPC program can act as a guide. The emergency managers interviewed for this study are currently engaged with HBPC programs and therefore understand the needs of homebound older adults and their caregivers. Extending the information already available to the HBPC teams via existing channels strengthens workforce practices and increased security for the shared patient, even without direct relationships between emergency managers and agencies. It is important to understand the limitations of these practices, including concerns around conflicting federal and state mandates, legal concerns around the liability of sharing physical resources (such as PPE), and awareness that the objective is not for the VHA to increase burdens (eg, increasing compliance requirements) but rather to serve as a resource for a mutual population in a shared community.

Offering training and practical resources to HHA home health care workers can help them meet disaster preparedness requirements. This is particularly important considering the growing home care workforce shortages, a topic mentioned by all HBPC and community care participants interviewed for this study.26,27 Home health care workers report feeling underprepared and isolated while on the job in normal conditions, a sentiment exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.3,10 Supporting these individuals may help them feel more prepared and connected to their work, improving stability and quality of care.

While these issues are priorities within the VHA, there is growing recognition at the state and federal level of the importance of including older adults and their HCPs in disaster preparedness and response.5,28 The US Department of Health and Human Services, for example, includes older adults and organizations that serve them on its National Advisory Committee on Seniors and Disasters. The Senate version of the 2023 reauthorization of the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Response Act included specific provisions to support community-dwelling older adults and people with disabilities, incorporating funding for community organizations to support continuity of services and avoid institutionalization in an emergency.29 Other proposed legislation includes the Real Emergency Access for Aging and Disability Inclusion for Disasters Act, which would ensure the needs of older adults and people with disabilities are explicitly included in all phases of emergency planning and response.30

The VHA expansion of the its VEText program to include disaster response is an effort to more efficiently extend outreach to older and vulnerable patients who are veterans.31 Given these growing efforts, the VHA and other health systems have an opportunity to expand internal emergency preparedness efforts to ensure the health and safety of individuals living in the community.

Limitations

VISN 2 has been a target of terrorism and other disasters. In addition to the sites being initially recruited for their strong emergency management protocols, this context may have biased respondents who are favorable to extending their resources into the community. At the time of recruitment, contracted HHAs were still experiencing staff shortages due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited the ability of agency staff to participate in interviews. Additionally, while the comprehensive exploration of VISN 2 facilities allows for confidence of the organizational structures described, the qualitative research design and small study sample, the study findings cannot be immediately generalized to all VISNs.

Conclusions

Many older veterans increasingly rely on home health care workers to age safely. The VHA, as a large national health care system and leader in emergency preparedness, could play an important role in supporting home health care workers and ameliorating their sense of isolation during emergencies and natural disasters. Leveraging existing resources and relationships may be a low-cost, low-effort opportunity to build higher-level interventions that support the needs of patients. Future research and work in this field, including the authors’ ongoing work, will expand agency participation and engage agency staff in conceptualizing pilot projects to ensure they are viable and feasible for the field.

- Barnett DJ, Knieser L, Errett NA, Rosenblum AJ, Seshamani M, Kirsch TD. Reexamining health-care coalitions in light of COVID-19. Disaster Med public Health Prep. 2022;16(3):859-863. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.431

- Wulff K, Donato D, Lurie N. What is health resilience and how can we build it? Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:361-374. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122829

- Franzosa E, Wyte-Lake T, Tsui EK, Reckrey JM, Sterling MR. Essential but excluded: building disaster preparedness capacity for home health care workers and home care agencies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(12):1990-1996. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.09.012

- Miner S, Masci L, Chimenti C, Rin N, Mann A, Noonan B. An outreach phone call project: using home health to reach isolated community dwelling adults during the COVID 19 lockdown. J Community Health. 2022;47(2):266-272. doi:10.1007/s10900-021-01044-6

- National Institute on Aging. Protecting older adults from the effects of natural disasters and extreme weather. October 18, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/protecting-older-adults-effects-natural-disasters-and-extreme-weather

- PHI. Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts. September 7, 2021. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.phinational.org/resource/direct-care-workers-in-the-united-states-key-facts-2/

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency Preparedness Rule. September 8, 2016. Updated September 6, 2023. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/health-safety-standards/quality-safety-oversight-emergency-preparedness/emergency-preparedness-rule

- Wyte-Lake T, Claver M, Tubbesing S, Davis D, Dobalian A. Development of a home health patient assessment tool for disaster planning. Gerontology. 2019;65(4):353-361. doi:10.1159/000494971

- Franzosa E, Judon KM, Gottesman EM, et al. Home health aides’ increased role in supporting older veterans and primary healthcare teams during COVID-19: a qualitative analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(8):1830-1837. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07271-w

- Franzosa E, Tsui EK, Baron S. “Who’s caring for us?”: understanding and addressing the effects of emotional labor on home health aides’ well-being. Gerontologist. 2019;59(6):1055-1064. doi:10.1093/geront/gny099

- Osakwe ZT, Osborne JC, Samuel T, et al. All alone: a qualitative study of home health aides’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(11):1362-1368. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2021.08.004

- Feldman PH, Russell D, Onorato N, et al. Ensuring the safety of the home health aide workforce and the continuation of essential patient care through sustainable pandemic preparedness. July 2022. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.vnshealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Pandemic_Preparedness_IB_07_21_22.pdf

- Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Internal Med. 2020;180(11):1453-1459. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3930

- Wyte-Lake T, Schmitz S, Kornegay RJ, Acevedo F, Dobalian A. Three case studies of community behavioral health support from the US Department of Veterans Affairs after disasters. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):639. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10650-x

- Beales JL, Edes T. Veteran’s affairs home based primary care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25(1):149-ix. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.11.002

- Wyte-Lake T, Manheim C, Gillespie SM, Dobalian A, Haverhals LM. COVID-19 vaccination in VA home based primary care: experience of interdisciplinary team members. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(6):917-922. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.03.014

- Wyte-Lake T, Schmitz S, Cosme Torres-Sabater R, Dobalian A. Case study of VA Caribbean Healthcare System’s community response to Hurricane Maria. J Emerg Manag. 2022;19(8):189-199. doi:10.5055/jem.0536

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. New York/New Jersey VA Health Care Network, VISN 2 Locations. Updated January 3, 2024. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.visn2.va.gov/visn2/facilities.asp

- Noy C. Sampling knowledge: the hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2008;11(4):327-344. doi:10.1080/13645570701401305

- Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, Ormston R, eds. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. 2nd ed. Sage; 2013.

- Morrow SL. Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):250-260. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

- Rolfe G. Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: quality and the idea of qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(3):304-310. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03727.x

- Schmitz S, Wyte-Lake T, Dobalian A. Facilitators and barriers to preparedness partnerships: a veterans affairs medical center perspective. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2018;12(4):431-436. doi:10.1017/dmp.2017.92

- Koch AE, Bohn J, Corvin JA, Seaberg J. Maturing into high-functioning health-care coalitions: a qualitative Nationwide study of emergency preparedness and response leadership. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;17:e111. doi:10.1017/dmp.2022.13

- Lin JS, Webber EM, Bean SI, Martin AM, Davies MC. Rapid evidence review: policy actions for the integration of public health and health care in the United States. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1098431. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1098431

- Watts MOM, Burns A, Ammula M. Ongoing impacts of the pandemic on medicaid home & community-based services (HCBS) programs: findings from a 50-state survey. November 28, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/ongoing-impacts-of-the-pandemic-on-medicaid-home-community-based-services-hcbs-programs-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/

- Kreider AR, Werner RM. The home care workforce has not kept pace with growth in home and community-based services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(5):650-657. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01351

- FEMA introduces disaster preparedness guide for older adults. News release. FEMA. September 20, 2023. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20230920/fema-introduces-disaster-preparedness-guide-older-adults

- Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Response Act, S 2333, 118th Cong, 1st Sess (2023). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2333/text

- REAADI for Disasters Act, HR 2371, 118th Cong, 1st Sess (2023). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2371

- Wyte-Lake T, Brewster P, Hubert T, Gin J, Davis D, Dobalian A. VA’s experience building capability to conduct outreach to vulnerable patients during emergencies. Innov Aging. 2023;7(suppl 1):209. doi:10.1093/geroni/igad104.0690

As large-scale natural disasters become more common, health care coalitions and the engagement of health systems with local, state, and federal public health departments have effectively bolstered communities’ resilience via collective sharing and distribution of resources.1 These resources may include supplies and the dissemination of emergency information, education, and training.2 The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that larger health care systems including hospital networks and nursing homes are better connected to health care coalition resources than smaller, independent systems, such as community home health agencies.3 This leaves some organizations on their own to meet requirements that maintain continuity of care and support their patients and staff throughout a natural disaster.

Home health care workers play important roles in the care of older adults.4 Older adults experience high levels of disability and comorbidities that put them at risk during emergencies; they often require support from paid, family, and neighborhood caregivers to live independently.5 More than 9.3 million US adults receive paid care from 2.6 million home health care workers (eg, home health aides and personal care assistants).6 Many of these individuals are hired through small independent home health agencies (HHAs), while others may work directly for an individual. When neighborhood resources and family caregiving are disrupted during emergencies, the critical services these workers administer become even more essential to ensuring continued access to medical care and social services.

The importance of these services was underscored by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2017 inclusion of HHAs in federal emergency preparedness guidelines.7,8 The fractured and decentralized nature of the home health care industry means many HHAs struggle to maintain continuous care during emergencies and protect their staff. HHAs, and health care workers in the home, are often isolated, under-resourced, and disconnected from broader emergency planning efforts. Additionally, home care jobs are largely part-time, unstable, and low paying, making the workers themselves vulnerable during emergencies.3,9-13

This is a significant issue for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which annually purchases 10.5 million home health care worker visits for 150,000 veterans from community-based HHAs to enable those individuals to live independently. Figure 1 illustrates the existing structure of directly provided and contracted VHA services for community-dwelling veterans, highlighting the circle of care around the veteran.8,9 Home health care workers anchored health care teams during the COVID-19 pandemic, observing and reporting on patients’ well-being to family caregivers, primary care practitioners, and HHAs. They also provided critical emotional support and companionship to patients isolated from family and friends.9 These workers also exposed themselves and their families to considerable risk and often lacked the protection afforded by personal protective equipment (PPE) in accordance with infection prevention guidance.3,12

Abbreviations: HBPC, home based primary care; HHA, home health agency; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

aAdapted with permission from Wyte-Lake and Franzosa.8,9

Through a combination of its national and local health care networks, the VHA has a robust and well-positioned emergency infrastructure to supportcommunity-dwelling older adults during disasters.14 This network is supported by the VHA Office of Emergency Management, which shares resources and guidance with local emergency managers at each facility as well as individual programs such as the VHA Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) program, which provides 38,000 seriously ill veterans with home medical visits.15 Working closely with their local and national hospital networks and emergency managers, individual VHA HBPC programs were able to maintain the safety of staff and continuity of care for patients enrolled in HBPC by rapidly administering COVID-19 vaccines to patients, caregivers, and staff, and providing emergency assistance during the 2017 hurricane season.16,17 These efforts were successful because HBPC practitioners and their patients, had access to a level of emergency-related information, resources, and technology that are often out of reach for individual community-based health care practitioners (HCPs). The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) also supports local communities through its Fourth Mission, which provides emergency resources to non-VHA health care facilities (ie, hospitals and nursing homes) during national emergencies and natural disasters.17 Although there has been an expansion in the definition of shared resources, such as extending behavioral health support to local communities, the VHA has not historically provided these resources to HHAs.14

This study examines opportunities to leverage VHA emergency management resources to support contracted HHAs and inform other large health system emergency planning efforts. The findings from the exploratory phase are described in this article. We interviewed VHA emergency managers, HBPC and VA staff who coordinate home health care worker services, as well as administrators at contracted HHAs within a Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN). These findings will inform the second (single-site pilot study) and third (feasibility study) phases. Our intent was to (1) better understand the relationships between VA medical centers (VAMCs) and their contracted HHAs; (2) identify existing VHA emergency protocols to support community-dwelling older adults; and (3) determine opportunities to build on existing infrastructure and relationships to better support contracted HHAs and their staff in emergencies.

Methods

The 18 VISNs act as regional systems of care that are loosely connected to better meet local health needs and maximize access to care. This study was conducted at 6 of 9 VAMCs within VISN 2, the New York/New Jersey VHA Health Care Network.18 VAMCs that serve urban, rural, and mixed urban/rural catchment areas were included.

Each VAMC has an emergency management program led by an emergency manager, an HBPC program led by a program director and medical director, and a community care or purchased care office that has a liaison who manages contracted home health care worker services. The studyfocused on HBPC programs because they are most likely to interact with veterans’ home health care workers in the home and care for community-dwelling veterans during emergencies. Each VHA also contracts with a series of local HHAs that generally have a dedicated staff member who interfaces with the VHA liaison. Our goal was to interview ≥ 1 emergency manager, ≥ 1 HBPC team member, ≥ 1 community care staff person, and ≥ 1 contracted home health agency administrator at each site to gain multiple perspectives from the range of HCPs serving veterans in the community.

Recruitment and Data Collection

The 6 sites were selected in consultation with VISN 2 leadership for their strong HBPC and emergency management programs. To recruit respondents, we contacted VISN and VAMC leads and used our professional networks to identify a sample of multidisciplinary individuals who represent both community care and HBPC programs who were contacted via email.

Since each VAMC is organized differently, we utilized a snowball sampling approach to identify the appropriate contacts.19 At the completion of each interview, we asked the participant to suggest additional contacts and introduce us to any remaining stakeholders (eg, the emergency manager) at that site or colleagues at other VISN facilities. Because roles vary among VAMCs, we contacted the person who most closely resembled the identified role and asked them to direct us to a more appropriate contact, if necessary. We asked community care managers to identify 1 to 2 agencies serving the highest volume of patients who are veterans at their site and requested interviews with those liaisons. This resulted in the recruitment of key stakeholders from 4 teams across the 6 sites (Table).

A semistructured interview guide was jointly developed based on constructs of interest, including relationships within VAMCs and between VAMCs and HHAs; existing emergency protocols and experience during disasters; and suggestions and opportunities for supporting agencies during emergencies and potential barriers. Two researchers (TWL and EF) who were trained in qualitative methods jointly conducted interviews using the interview guide, with 1 researcher leading and another taking notes and asking clarifying questions.

Interviews were conducted virtually via Microsoft Teams with respondents at their work locations between September 2022 and January 2023. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed and 2 authors (TWL and ESO) reviewed transcripts for accuracy. Interviews averaged 47 minutes in length (range, 20-59).

The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt by institutional review boards at the James J. Peters VAMC and Greater Los Angeles VAMC. We asked participants for verbal consent to participate and preserved their confidentiality.

Analysis

Data were analyzed via an inductive approach, which involves drawing salient themes rather than imposing preconceived theories.20 Three researchers (TWL, EF, and ES) listened to and discussed 2 staff interviews and tagged text with specific codes (eg, communication between the VHA and HHA, internal communication, and barriers to case fulfillment) so the team could selectively return to the interview text for deeper analysis, allowing for the development of a final codebook. The project team synthesized the findings to identify higher-level themes, drawing comparisons across and within the respondent groups, including within and between health care systems. Throughout the analysis, we maintained analytic memos, documented discussions, and engaged in analyst triangulation to ensure trustworthiness.21,22 To ensure the analysis accurately reflected the participants’ understanding, we held 2 virtual member-checking sessions with participants to share preliminary findings and conclusions and solicit feedback. Analysis was conducted using ATLAS.ti version 20.

Results

VHA-based participants described internal emergency management systems that are deployed during a disaster to support patients and staff. Agency participants described their own internal emergency management protocols. Respondents discussed how and when the 2 intersected, as well as opportunities for future mutual support. The analysis identified several themes: (1) relationships between VAMC teams; (2) relationships between VHA and HHAs; (3) VHA and agencies responses during emergencies; (4) receptivity and opportunities for extending VHA resources into the community; and (5) barriers and facilitators to deeper engagement.

Relationships Within VHA (n = 17)

Staff at all VHA sites described close relationships between the internal emergency management and HBPC teams. HBPC teams identified patients who were most at risk during emergencies to triage those with the highest medical needs (eg, patients dependent on home infusion, oxygen, or electronic medical devices) and worked alongside emergency managers to develop plans to continue care during an emergency. HBPC representatives were part of their facilities’ local emergency response committees. Due to this close collaboration, VHA emergency managers were familiar with the needs of homebound veterans and caregivers. “I invite our [HBPC] program manager to attend [committee] meetings and … they’re part of the EOC [emergency operations center]," an emergency manager said. “We work together and I’m constantly in contact with that individual, especially during natural disasters and so forth, to ensure that everybody’s prepared in the community.”

On the other hand, community caremanagers—who described frequent interactions with HBPC teams, largely around coordinating and managing non-VHA home care services—were less likely to have direct relationships with their facility emergency managers. For example, when asked if they had a relationship with their emergency manager, a community care manager admitted, “I [only] know who he is.” They also did not report having structured protocols for veteran outreach during emergencies, “because all those veterans who are receiving [home health care worker] services also belong to a primary care team,” and considered the outreach to be the responsibility of the primary care team and HHA.

Relationships Between the VHA and HHAs (n = 17)

Communication between VAMCs and contracted agencies primarily went through community care managers, who described established long-term relationships with agency administrators. Communication was commonly restricted to operational activities, such as processing referrals and occasional troubleshooting. According to a community care manager most communication is “why haven’t you signed my orders?” There was a general sense from participants that communication was promptly answered, problems were addressed, and professional collegiality existed between the agencies as patients were referred and placed for services. One community care manager reported meeting with agencies regularly, noting, “I talk to them pretty much daily.”

If problems arose, community care managers described themselves as “the liaison” between agencies and VHA HCPs who ordered the referrals. This is particularly the case if the agency needed help finding a VHA clinician or addressing differences in care delivery protocols.

Responding During Emergencies (n = 19)

During emergencies, VHA and agency staff described following their own organization’s protocols and communicating with each other only on a case-by-case basis rather than through formal or systematic channels and had little knowledge of their counterpart’s emergency protocols. Beyond patient care, there was no evidence of information sharing between VHA and agency staff. Regarding sharing information with their local community, an HBPC Program Director said, “it’s almost like the VHA had become siloed” and operated on its own without engaging with community health systems or emergency managers.

Beyond the guidance provided by state departments of public health, HHAs described collaborating with other agencies in their network and relying on their informal professional network to manage the volume of information and updates they followed during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic. One agency administrator did not frequently communicate with VHA partners during the pandemic but explained that the local public health department helped work through challenges. However, “we realized pretty quickly they were overloaded and there was only so much they could do.” The agency administrator turned to a “sister agency” and local hospitals, noting, “Wherever you have connections in the field or in the industry, you know you’re going to reach out to people for guidance on policies and… protocol.”

Opportunities for Extending VHA Resources to the Community (n = 16)

All VHA emergency managers were receptive to extending support to community-based HCPS and, in some cases, felt strongly that they were an essential part of veterans’ care networks. Emergency managers offered examples for how they supportedcommunity-based HCPs, such as helping those in the VAMC medical foster home program develop and evaluate emergency plans. Many said they had not explicitly considered HHAs before (Appendix).

Emergency managers also described how supporting community-based HCPs could be considered within the scope of the VHA role and mission, specifically the Fourth Mission. “I think that we should be making our best effort to make sure that we’re also providing that same level [of protection] to the people taking care of the veteran [as our VHA staff],” an emergency manager said. “It’s our responsibility to provide the best for the staff that are going into those homes to take care of that patient.”

In many cases, emergency managers had already developed practical tools that could be easily shared outside the VHA, including weather alerts, trainings, emergency plan templates, and lists of community resources and shelters (Figure 2). A number of these examples built on existing communication channels. One emergency manager said that the extension of resources could be an opportunity to decrease the perceived isolation of home health care workers through regular

Abbreviations: PPE, personal protective equipment; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

On the agency side, participants noted that some HHAs could benefit more from support than others. While some agencies are well staffed and have good protocols and keep up to date, “There are smaller agencies, agencies that are starting up that may not have the resources to just disseminate all the information. Those are the agencies [that] could well benefit from the VHA,” an HBPC medical director explained. Agency administrators suggested several areas where they would welcome support, including a deeper understanding of available community resources and access to PPE for staff. Regarding informational resources, an administrator said, “Anytime we can get information, it’s good to have it come to you and not always have to go out searching for it.”

Barriers and Facilitators to Partnering With Community Agencies (n = 16)

A primary barrier regarding resource sharing was potential misalignment between each organization’s policies. HHAs followed state and federal public health guidelines, which sometimes differed from VHA policies. Given that agencies care for both VHA and non-VHA clients, questions also arose around how agencies would prioritize information from the VHA, if they were already receiving information from other sources. When asked about information sharing, both VHA staff and agencies agreed staff time to support any additional activities should be weighed against the value of the information gained.

Six participants also shared that education around emergency preparedness could be an opportunity to bridge gaps between VAMCs and their surrounding communities.

Two emergency managers noted the need to be sensitive in the way they engaged with partners, respecting and building on the work that agencies were already doing in this area to ensure VHA was seen as a trusted partner and resource rather than trying to impose new policies or rules on community-based HCPs. “I know that like all leadership in various organizations, there’s a little bit of bristling going on when other people try and tell them what to do,” an HBPC medical director said. “However, if it is established that as a sort of greater level like a state level or a federal level, that VHA can be a resource. I think that as long as that’s recognized by their own professional organizations within each state, then I think that that would be a tremendous advantage to many agencies.”

In terms of sharing physical resources, emergency managers raised concerns around potential liability, although they also acknowledged this issue was important enough to think about potential workarounds. As one emergency manager said, “I want to know that my PPE is not compromised in any way shape or form and that I am in charge of that PPE, so to rely upon going to a home and hoping that [the PPE] wasn’t compromised … would kind of make me a little uneasy.” This emergency manager suggested possible solutions, such as creating a sealed PPE package to give directly to an aide.

Discussion

As the prevalence of climate-related disasters increases, the need to ensure the safety and independence of older adults during emergencies grows more urgent. Health systems must think beyond the direct services they provide and consider the community resources upon which their patients rely. While relationships did not formally exist between VHA emergency managers and community home health HCPs in the sample analyzed in this article, there is precedent and interest in supporting contracted home health agencies caring for veterans in the community. Although not historically part of the VA Fourth Mission, creating a pipeline of support for contracted HHAs by leveraging existing relationships and resources can potentially strengthen its mission to protect older veterans in emergencies, help them age safely in place, and provide a model for health systems to collaborate with community-based HCPs around emergency planning and response (Figure 3).23

Existing research on the value of health care coalitions highlights the need for established and growing partnerships with a focus on ensuring they are value-added, which echoes concerns we heard in interviews.24 Investment in community partnerships not only includes sharing supplies but also relying on bidirectional support that can be a trusted form of timely information.1,25 The findings in this study exhibit strong communication practices within the VHA during periods of nonemergency and underscore the untapped value of the pre-existing relationship between VAMCs and their contracted HHAs as an area of potential growth for health care coalitions.

Sharing resources in a way that does not put new demands on partners contributes to the sustainability and value-added nature of coalitions. Examples include establishing new low-investment practices (ie, information sharing) that support capacity and compliance with existing requirements rather than create new responsibilities for either member of the coalition. The relationship between the VHA emergency managers and the VHA HBPC program can act as a guide. The emergency managers interviewed for this study are currently engaged with HBPC programs and therefore understand the needs of homebound older adults and their caregivers. Extending the information already available to the HBPC teams via existing channels strengthens workforce practices and increased security for the shared patient, even without direct relationships between emergency managers and agencies. It is important to understand the limitations of these practices, including concerns around conflicting federal and state mandates, legal concerns around the liability of sharing physical resources (such as PPE), and awareness that the objective is not for the VHA to increase burdens (eg, increasing compliance requirements) but rather to serve as a resource for a mutual population in a shared community.

Offering training and practical resources to HHA home health care workers can help them meet disaster preparedness requirements. This is particularly important considering the growing home care workforce shortages, a topic mentioned by all HBPC and community care participants interviewed for this study.26,27 Home health care workers report feeling underprepared and isolated while on the job in normal conditions, a sentiment exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.3,10 Supporting these individuals may help them feel more prepared and connected to their work, improving stability and quality of care.

While these issues are priorities within the VHA, there is growing recognition at the state and federal level of the importance of including older adults and their HCPs in disaster preparedness and response.5,28 The US Department of Health and Human Services, for example, includes older adults and organizations that serve them on its National Advisory Committee on Seniors and Disasters. The Senate version of the 2023 reauthorization of the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Response Act included specific provisions to support community-dwelling older adults and people with disabilities, incorporating funding for community organizations to support continuity of services and avoid institutionalization in an emergency.29 Other proposed legislation includes the Real Emergency Access for Aging and Disability Inclusion for Disasters Act, which would ensure the needs of older adults and people with disabilities are explicitly included in all phases of emergency planning and response.30

The VHA expansion of the its VEText program to include disaster response is an effort to more efficiently extend outreach to older and vulnerable patients who are veterans.31 Given these growing efforts, the VHA and other health systems have an opportunity to expand internal emergency preparedness efforts to ensure the health and safety of individuals living in the community.

Limitations

VISN 2 has been a target of terrorism and other disasters. In addition to the sites being initially recruited for their strong emergency management protocols, this context may have biased respondents who are favorable to extending their resources into the community. At the time of recruitment, contracted HHAs were still experiencing staff shortages due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited the ability of agency staff to participate in interviews. Additionally, while the comprehensive exploration of VISN 2 facilities allows for confidence of the organizational structures described, the qualitative research design and small study sample, the study findings cannot be immediately generalized to all VISNs.

Conclusions

Many older veterans increasingly rely on home health care workers to age safely. The VHA, as a large national health care system and leader in emergency preparedness, could play an important role in supporting home health care workers and ameliorating their sense of isolation during emergencies and natural disasters. Leveraging existing resources and relationships may be a low-cost, low-effort opportunity to build higher-level interventions that support the needs of patients. Future research and work in this field, including the authors’ ongoing work, will expand agency participation and engage agency staff in conceptualizing pilot projects to ensure they are viable and feasible for the field.

As large-scale natural disasters become more common, health care coalitions and the engagement of health systems with local, state, and federal public health departments have effectively bolstered communities’ resilience via collective sharing and distribution of resources.1 These resources may include supplies and the dissemination of emergency information, education, and training.2 The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that larger health care systems including hospital networks and nursing homes are better connected to health care coalition resources than smaller, independent systems, such as community home health agencies.3 This leaves some organizations on their own to meet requirements that maintain continuity of care and support their patients and staff throughout a natural disaster.

Home health care workers play important roles in the care of older adults.4 Older adults experience high levels of disability and comorbidities that put them at risk during emergencies; they often require support from paid, family, and neighborhood caregivers to live independently.5 More than 9.3 million US adults receive paid care from 2.6 million home health care workers (eg, home health aides and personal care assistants).6 Many of these individuals are hired through small independent home health agencies (HHAs), while others may work directly for an individual. When neighborhood resources and family caregiving are disrupted during emergencies, the critical services these workers administer become even more essential to ensuring continued access to medical care and social services.

The importance of these services was underscored by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2017 inclusion of HHAs in federal emergency preparedness guidelines.7,8 The fractured and decentralized nature of the home health care industry means many HHAs struggle to maintain continuous care during emergencies and protect their staff. HHAs, and health care workers in the home, are often isolated, under-resourced, and disconnected from broader emergency planning efforts. Additionally, home care jobs are largely part-time, unstable, and low paying, making the workers themselves vulnerable during emergencies.3,9-13

This is a significant issue for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which annually purchases 10.5 million home health care worker visits for 150,000 veterans from community-based HHAs to enable those individuals to live independently. Figure 1 illustrates the existing structure of directly provided and contracted VHA services for community-dwelling veterans, highlighting the circle of care around the veteran.8,9 Home health care workers anchored health care teams during the COVID-19 pandemic, observing and reporting on patients’ well-being to family caregivers, primary care practitioners, and HHAs. They also provided critical emotional support and companionship to patients isolated from family and friends.9 These workers also exposed themselves and their families to considerable risk and often lacked the protection afforded by personal protective equipment (PPE) in accordance with infection prevention guidance.3,12

Abbreviations: HBPC, home based primary care; HHA, home health agency; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

aAdapted with permission from Wyte-Lake and Franzosa.8,9

Through a combination of its national and local health care networks, the VHA has a robust and well-positioned emergency infrastructure to supportcommunity-dwelling older adults during disasters.14 This network is supported by the VHA Office of Emergency Management, which shares resources and guidance with local emergency managers at each facility as well as individual programs such as the VHA Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) program, which provides 38,000 seriously ill veterans with home medical visits.15 Working closely with their local and national hospital networks and emergency managers, individual VHA HBPC programs were able to maintain the safety of staff and continuity of care for patients enrolled in HBPC by rapidly administering COVID-19 vaccines to patients, caregivers, and staff, and providing emergency assistance during the 2017 hurricane season.16,17 These efforts were successful because HBPC practitioners and their patients, had access to a level of emergency-related information, resources, and technology that are often out of reach for individual community-based health care practitioners (HCPs). The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) also supports local communities through its Fourth Mission, which provides emergency resources to non-VHA health care facilities (ie, hospitals and nursing homes) during national emergencies and natural disasters.17 Although there has been an expansion in the definition of shared resources, such as extending behavioral health support to local communities, the VHA has not historically provided these resources to HHAs.14

This study examines opportunities to leverage VHA emergency management resources to support contracted HHAs and inform other large health system emergency planning efforts. The findings from the exploratory phase are described in this article. We interviewed VHA emergency managers, HBPC and VA staff who coordinate home health care worker services, as well as administrators at contracted HHAs within a Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN). These findings will inform the second (single-site pilot study) and third (feasibility study) phases. Our intent was to (1) better understand the relationships between VA medical centers (VAMCs) and their contracted HHAs; (2) identify existing VHA emergency protocols to support community-dwelling older adults; and (3) determine opportunities to build on existing infrastructure and relationships to better support contracted HHAs and their staff in emergencies.

Methods

The 18 VISNs act as regional systems of care that are loosely connected to better meet local health needs and maximize access to care. This study was conducted at 6 of 9 VAMCs within VISN 2, the New York/New Jersey VHA Health Care Network.18 VAMCs that serve urban, rural, and mixed urban/rural catchment areas were included.

Each VAMC has an emergency management program led by an emergency manager, an HBPC program led by a program director and medical director, and a community care or purchased care office that has a liaison who manages contracted home health care worker services. The studyfocused on HBPC programs because they are most likely to interact with veterans’ home health care workers in the home and care for community-dwelling veterans during emergencies. Each VHA also contracts with a series of local HHAs that generally have a dedicated staff member who interfaces with the VHA liaison. Our goal was to interview ≥ 1 emergency manager, ≥ 1 HBPC team member, ≥ 1 community care staff person, and ≥ 1 contracted home health agency administrator at each site to gain multiple perspectives from the range of HCPs serving veterans in the community.

Recruitment and Data Collection

The 6 sites were selected in consultation with VISN 2 leadership for their strong HBPC and emergency management programs. To recruit respondents, we contacted VISN and VAMC leads and used our professional networks to identify a sample of multidisciplinary individuals who represent both community care and HBPC programs who were contacted via email.

Since each VAMC is organized differently, we utilized a snowball sampling approach to identify the appropriate contacts.19 At the completion of each interview, we asked the participant to suggest additional contacts and introduce us to any remaining stakeholders (eg, the emergency manager) at that site or colleagues at other VISN facilities. Because roles vary among VAMCs, we contacted the person who most closely resembled the identified role and asked them to direct us to a more appropriate contact, if necessary. We asked community care managers to identify 1 to 2 agencies serving the highest volume of patients who are veterans at their site and requested interviews with those liaisons. This resulted in the recruitment of key stakeholders from 4 teams across the 6 sites (Table).

A semistructured interview guide was jointly developed based on constructs of interest, including relationships within VAMCs and between VAMCs and HHAs; existing emergency protocols and experience during disasters; and suggestions and opportunities for supporting agencies during emergencies and potential barriers. Two researchers (TWL and EF) who were trained in qualitative methods jointly conducted interviews using the interview guide, with 1 researcher leading and another taking notes and asking clarifying questions.

Interviews were conducted virtually via Microsoft Teams with respondents at their work locations between September 2022 and January 2023. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed and 2 authors (TWL and ESO) reviewed transcripts for accuracy. Interviews averaged 47 minutes in length (range, 20-59).

The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt by institutional review boards at the James J. Peters VAMC and Greater Los Angeles VAMC. We asked participants for verbal consent to participate and preserved their confidentiality.

Analysis

Data were analyzed via an inductive approach, which involves drawing salient themes rather than imposing preconceived theories.20 Three researchers (TWL, EF, and ES) listened to and discussed 2 staff interviews and tagged text with specific codes (eg, communication between the VHA and HHA, internal communication, and barriers to case fulfillment) so the team could selectively return to the interview text for deeper analysis, allowing for the development of a final codebook. The project team synthesized the findings to identify higher-level themes, drawing comparisons across and within the respondent groups, including within and between health care systems. Throughout the analysis, we maintained analytic memos, documented discussions, and engaged in analyst triangulation to ensure trustworthiness.21,22 To ensure the analysis accurately reflected the participants’ understanding, we held 2 virtual member-checking sessions with participants to share preliminary findings and conclusions and solicit feedback. Analysis was conducted using ATLAS.ti version 20.

Results

VHA-based participants described internal emergency management systems that are deployed during a disaster to support patients and staff. Agency participants described their own internal emergency management protocols. Respondents discussed how and when the 2 intersected, as well as opportunities for future mutual support. The analysis identified several themes: (1) relationships between VAMC teams; (2) relationships between VHA and HHAs; (3) VHA and agencies responses during emergencies; (4) receptivity and opportunities for extending VHA resources into the community; and (5) barriers and facilitators to deeper engagement.

Relationships Within VHA (n = 17)

Staff at all VHA sites described close relationships between the internal emergency management and HBPC teams. HBPC teams identified patients who were most at risk during emergencies to triage those with the highest medical needs (eg, patients dependent on home infusion, oxygen, or electronic medical devices) and worked alongside emergency managers to develop plans to continue care during an emergency. HBPC representatives were part of their facilities’ local emergency response committees. Due to this close collaboration, VHA emergency managers were familiar with the needs of homebound veterans and caregivers. “I invite our [HBPC] program manager to attend [committee] meetings and … they’re part of the EOC [emergency operations center]," an emergency manager said. “We work together and I’m constantly in contact with that individual, especially during natural disasters and so forth, to ensure that everybody’s prepared in the community.”

On the other hand, community caremanagers—who described frequent interactions with HBPC teams, largely around coordinating and managing non-VHA home care services—were less likely to have direct relationships with their facility emergency managers. For example, when asked if they had a relationship with their emergency manager, a community care manager admitted, “I [only] know who he is.” They also did not report having structured protocols for veteran outreach during emergencies, “because all those veterans who are receiving [home health care worker] services also belong to a primary care team,” and considered the outreach to be the responsibility of the primary care team and HHA.

Relationships Between the VHA and HHAs (n = 17)

Communication between VAMCs and contracted agencies primarily went through community care managers, who described established long-term relationships with agency administrators. Communication was commonly restricted to operational activities, such as processing referrals and occasional troubleshooting. According to a community care manager most communication is “why haven’t you signed my orders?” There was a general sense from participants that communication was promptly answered, problems were addressed, and professional collegiality existed between the agencies as patients were referred and placed for services. One community care manager reported meeting with agencies regularly, noting, “I talk to them pretty much daily.”

If problems arose, community care managers described themselves as “the liaison” between agencies and VHA HCPs who ordered the referrals. This is particularly the case if the agency needed help finding a VHA clinician or addressing differences in care delivery protocols.