User login

Medical assistants identify strategies and barriers to clinic efficiency

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

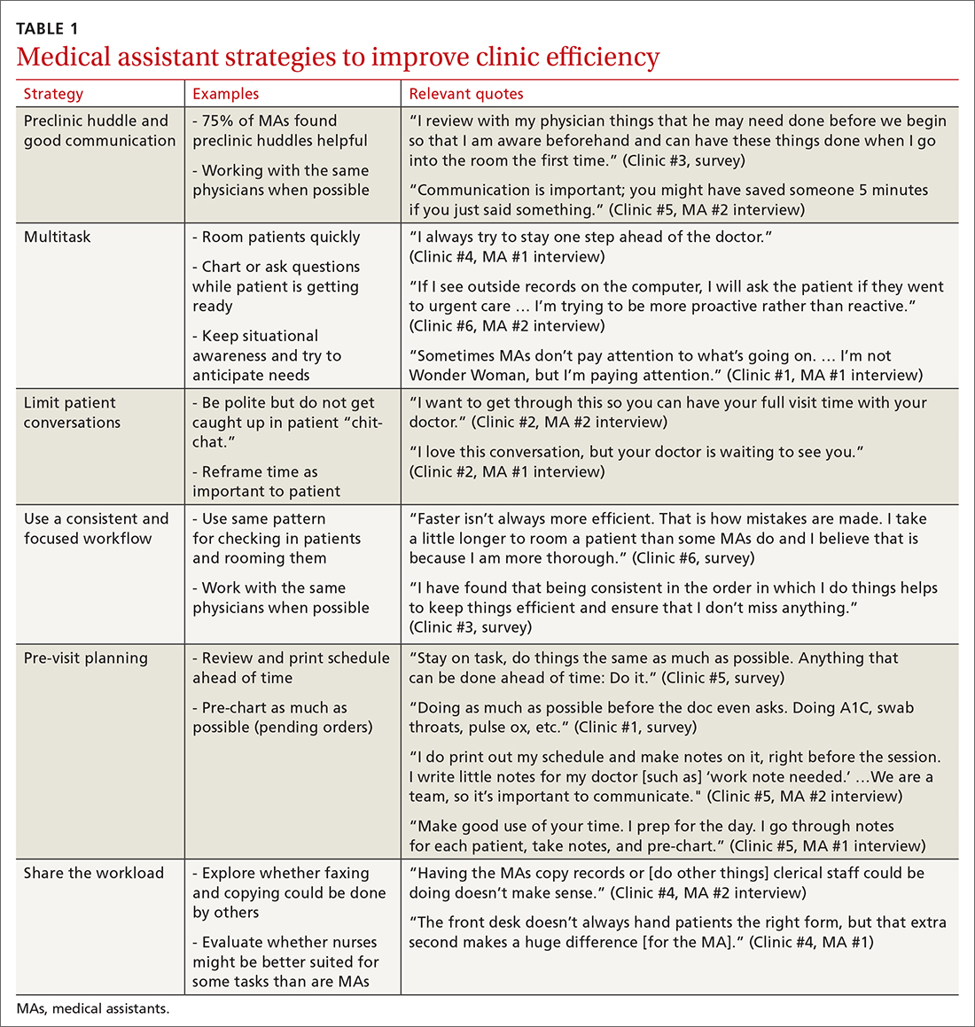

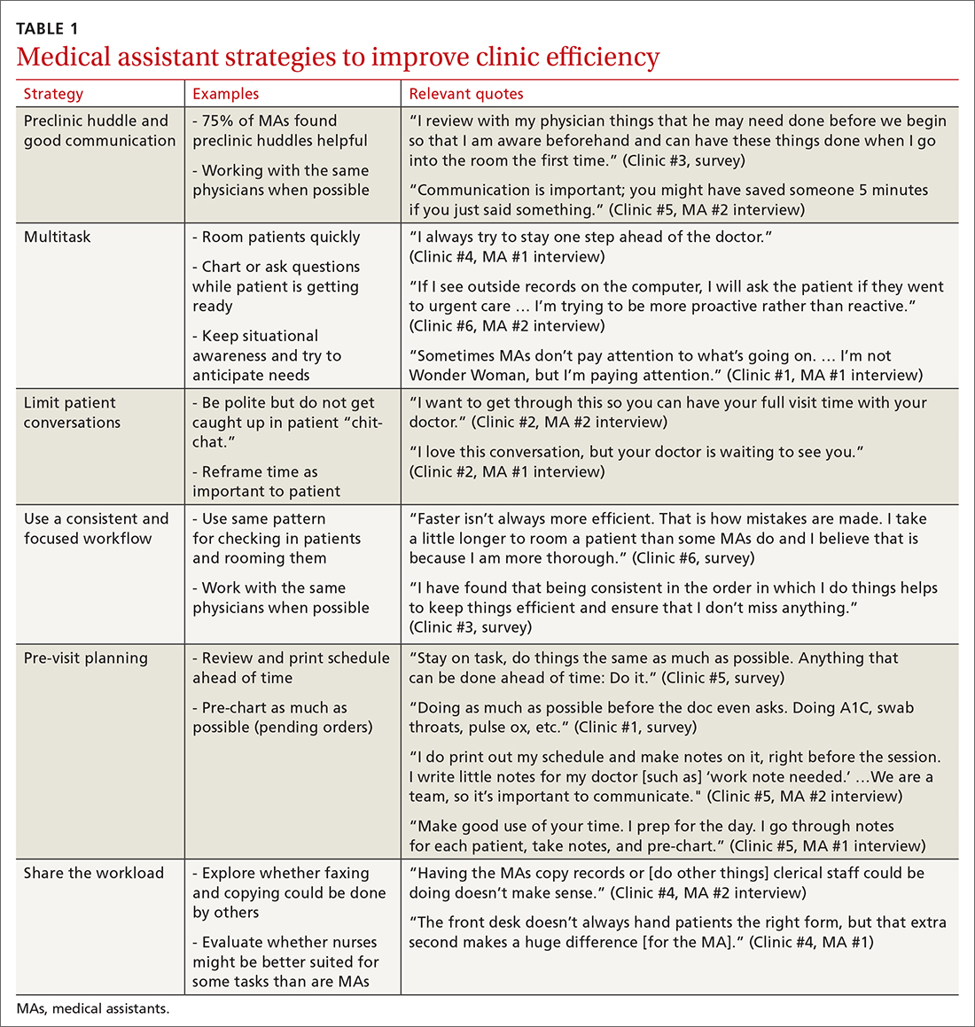

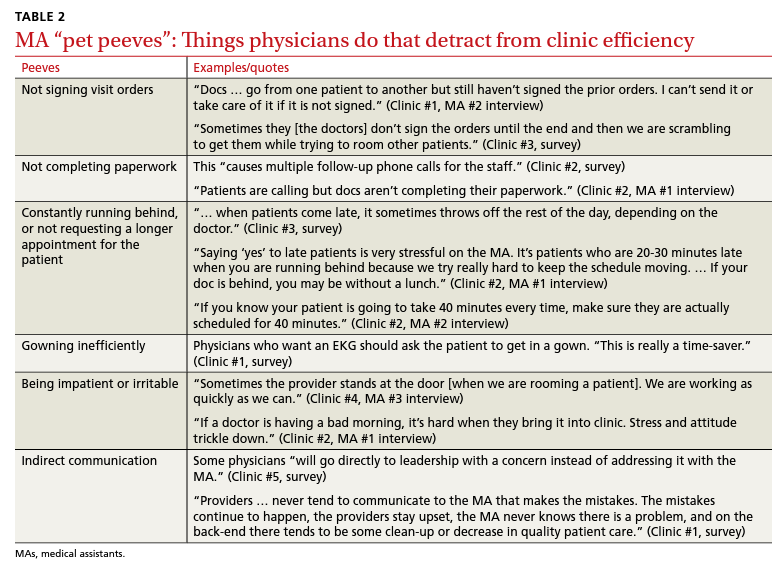

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

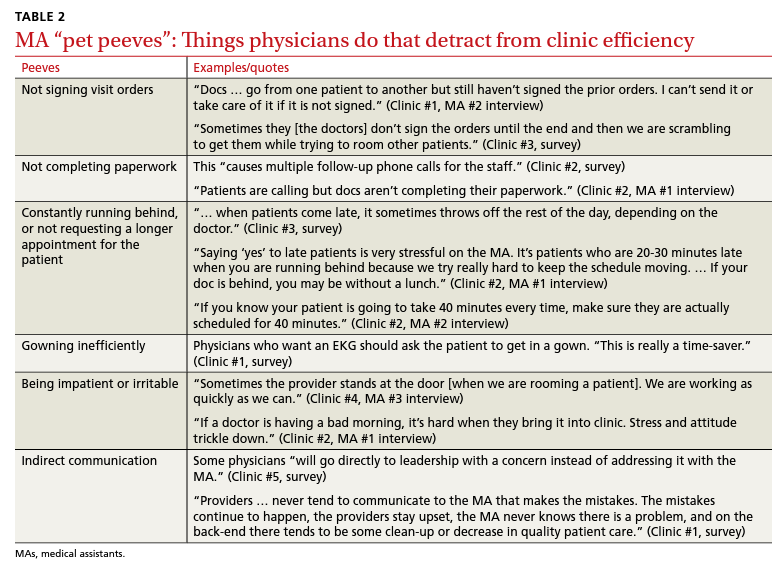

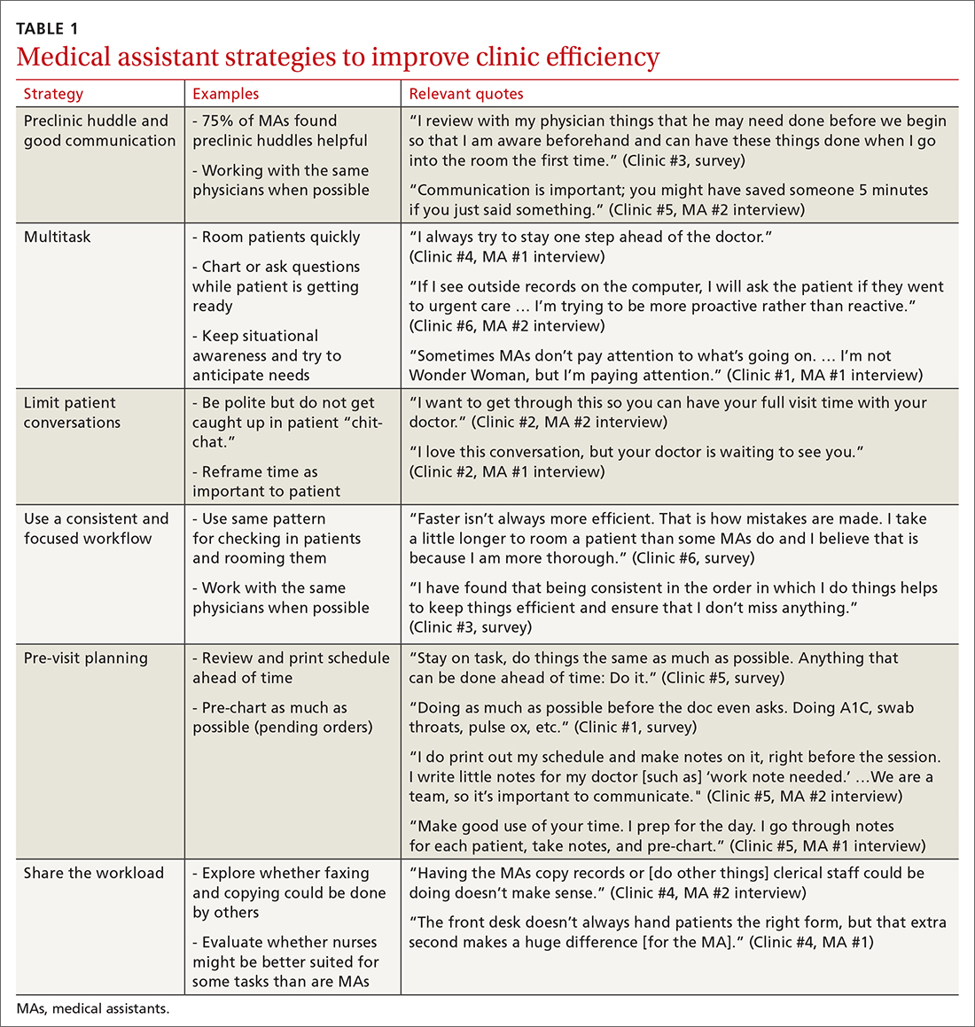

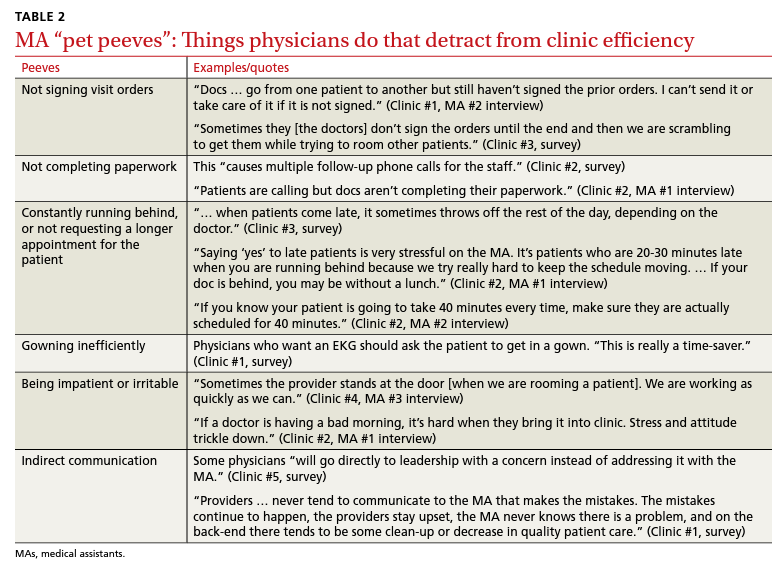

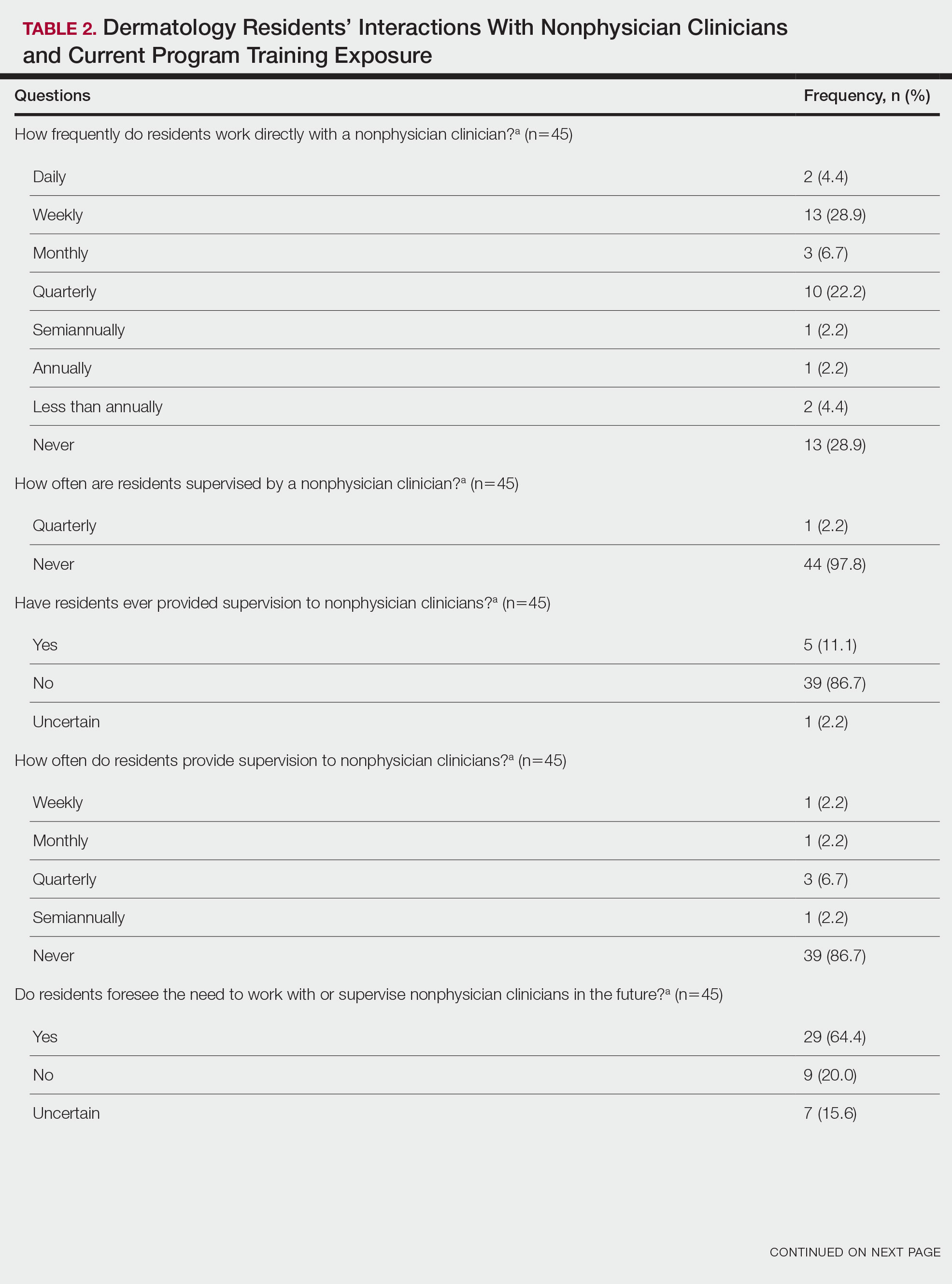

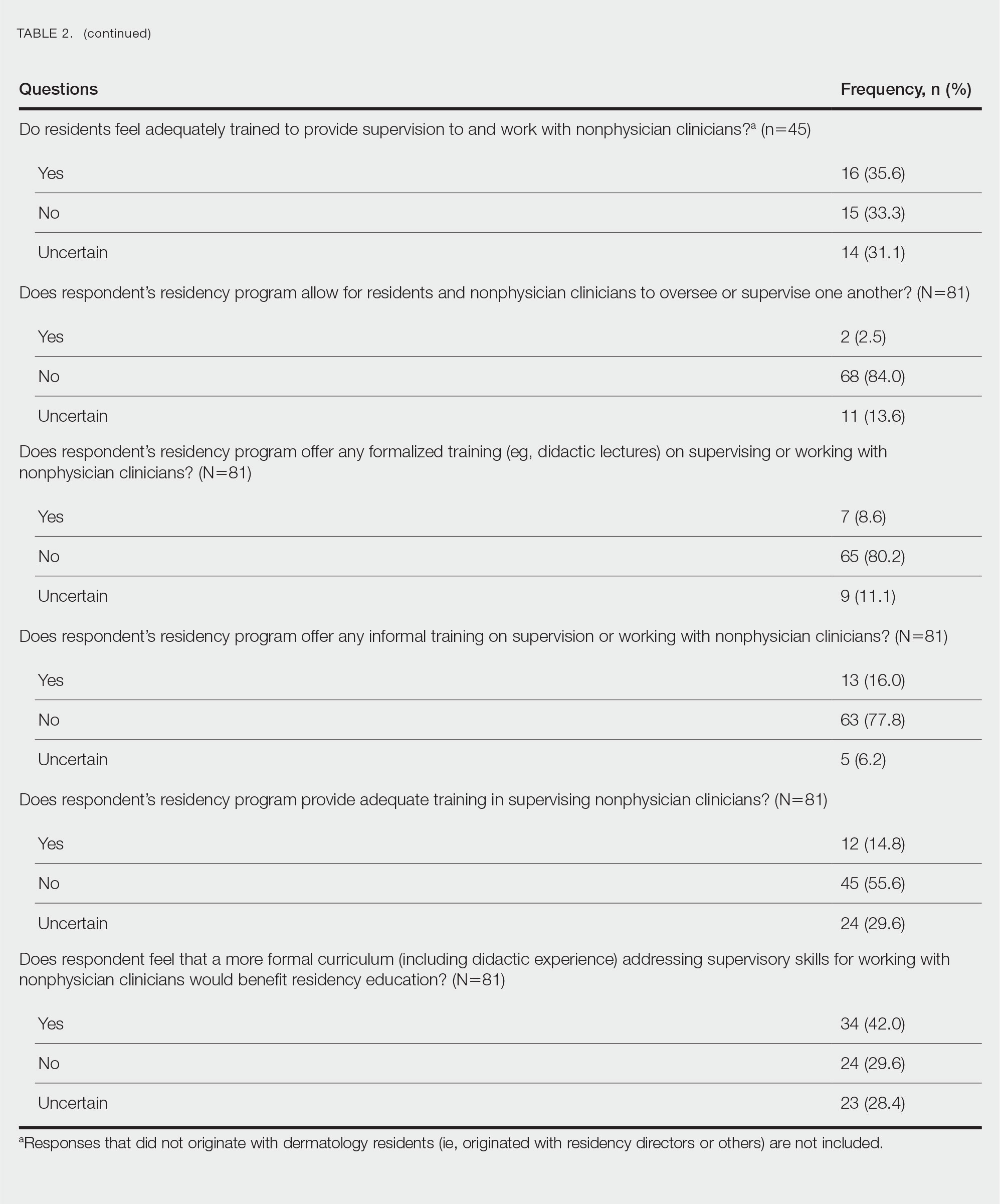

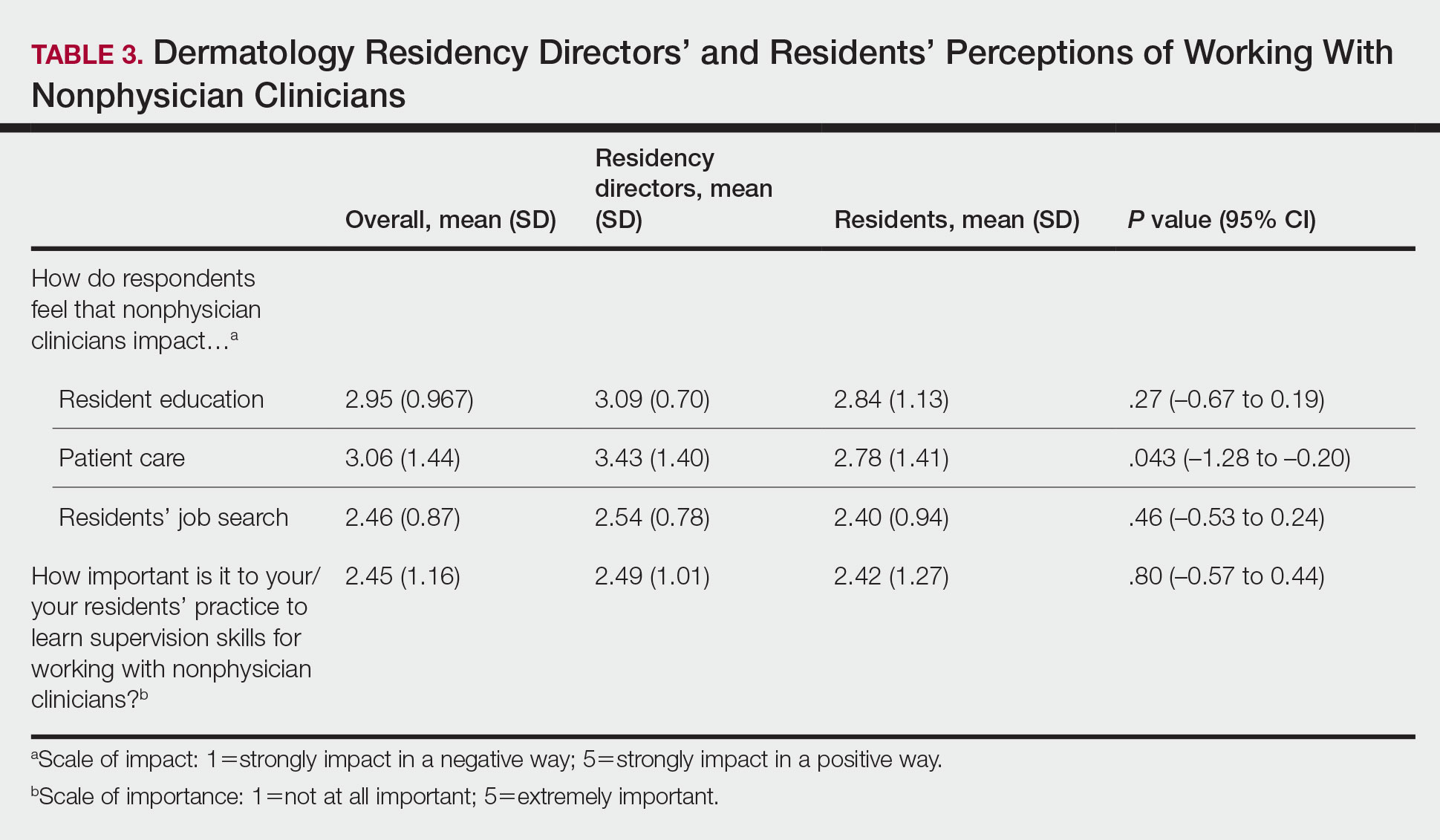

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

- Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

- Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

- Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/ articles/medical-assisting-trends/

- Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

- Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medicalassisting-history/

- Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

- Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

- Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

- Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

- STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/ fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_ combined.pdf

- Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

- Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

- Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

- Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ oes/current/oes319092.htm

- Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

- Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

- Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

- Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11: 187-201.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

- O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

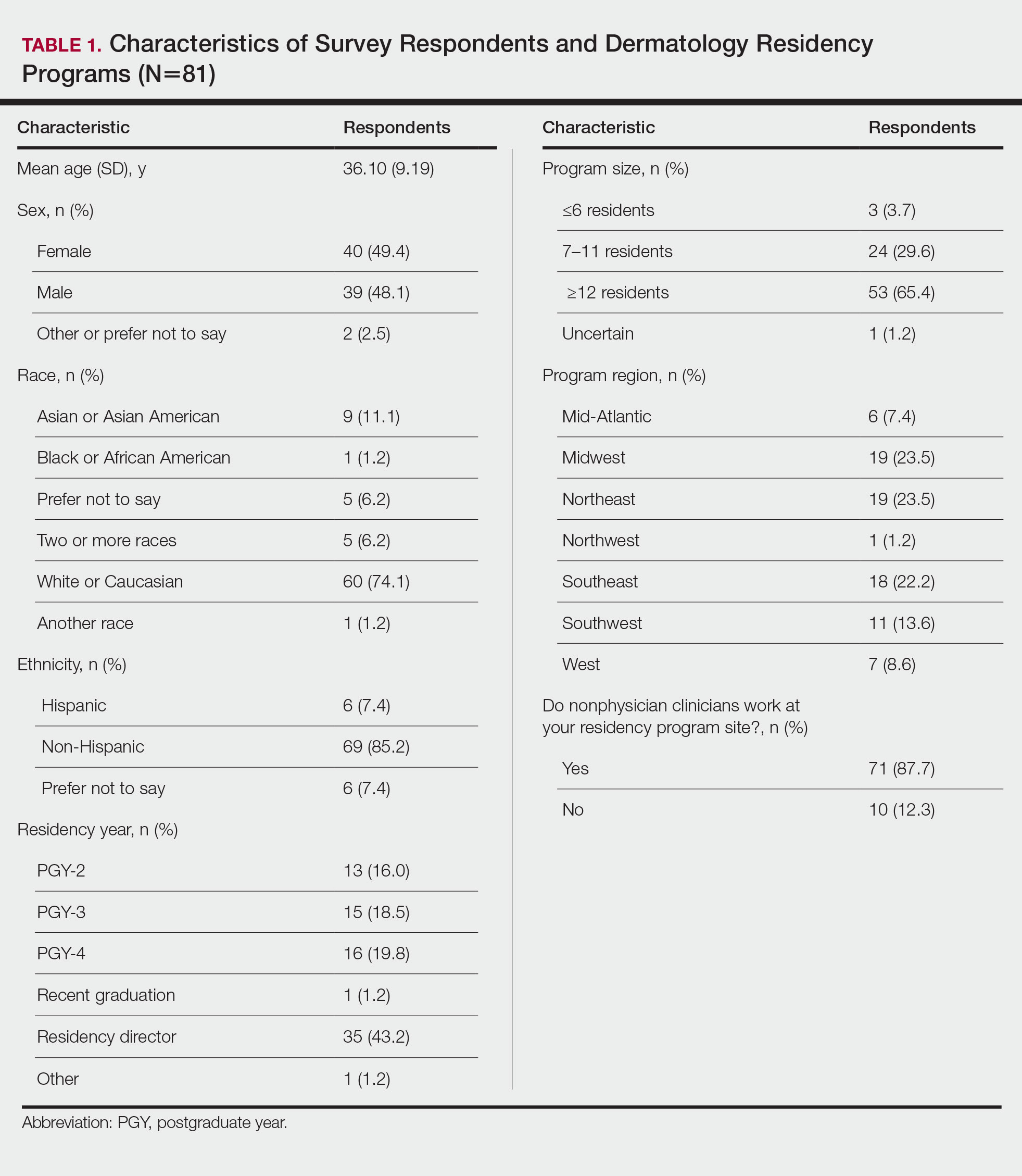

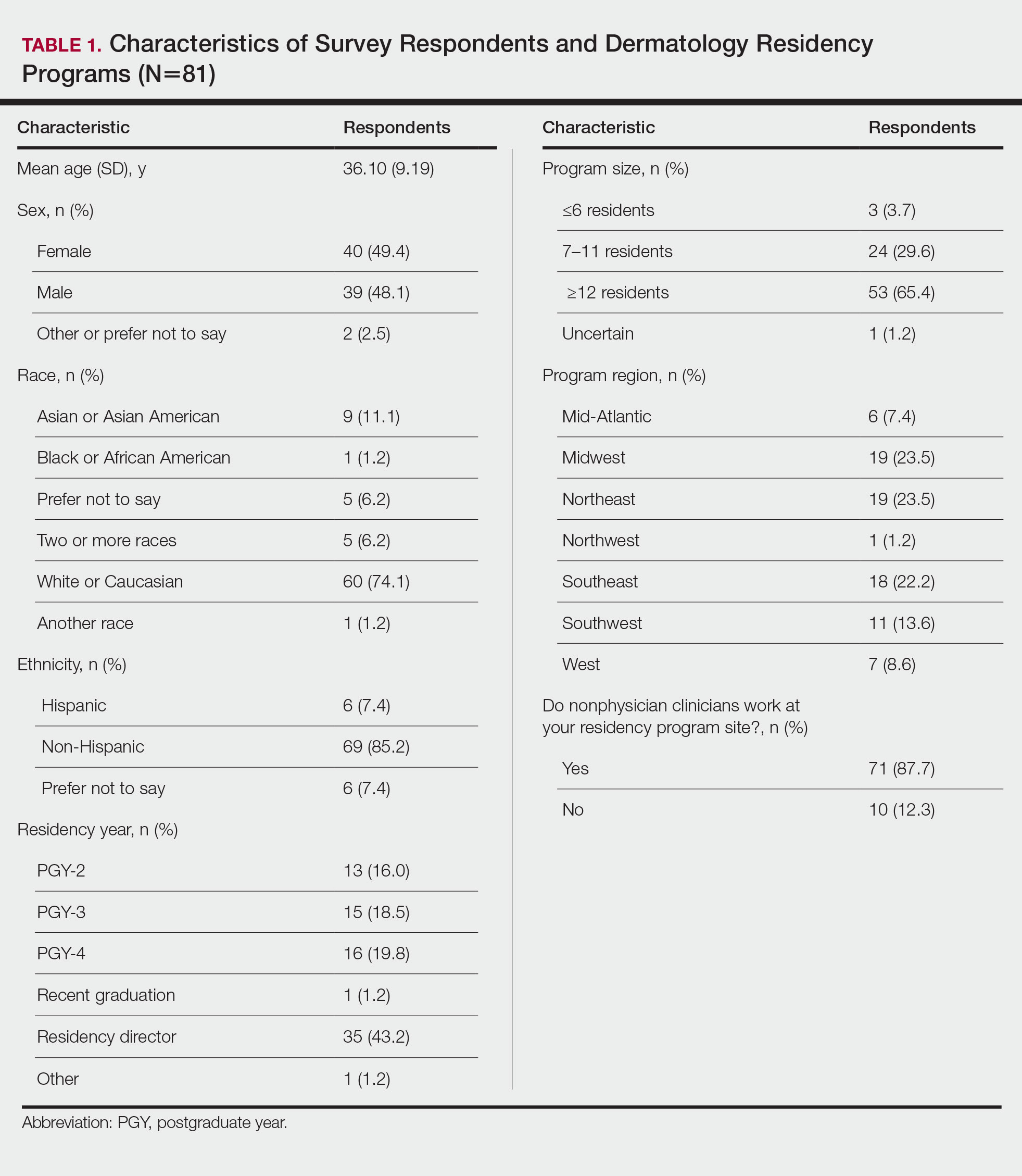

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

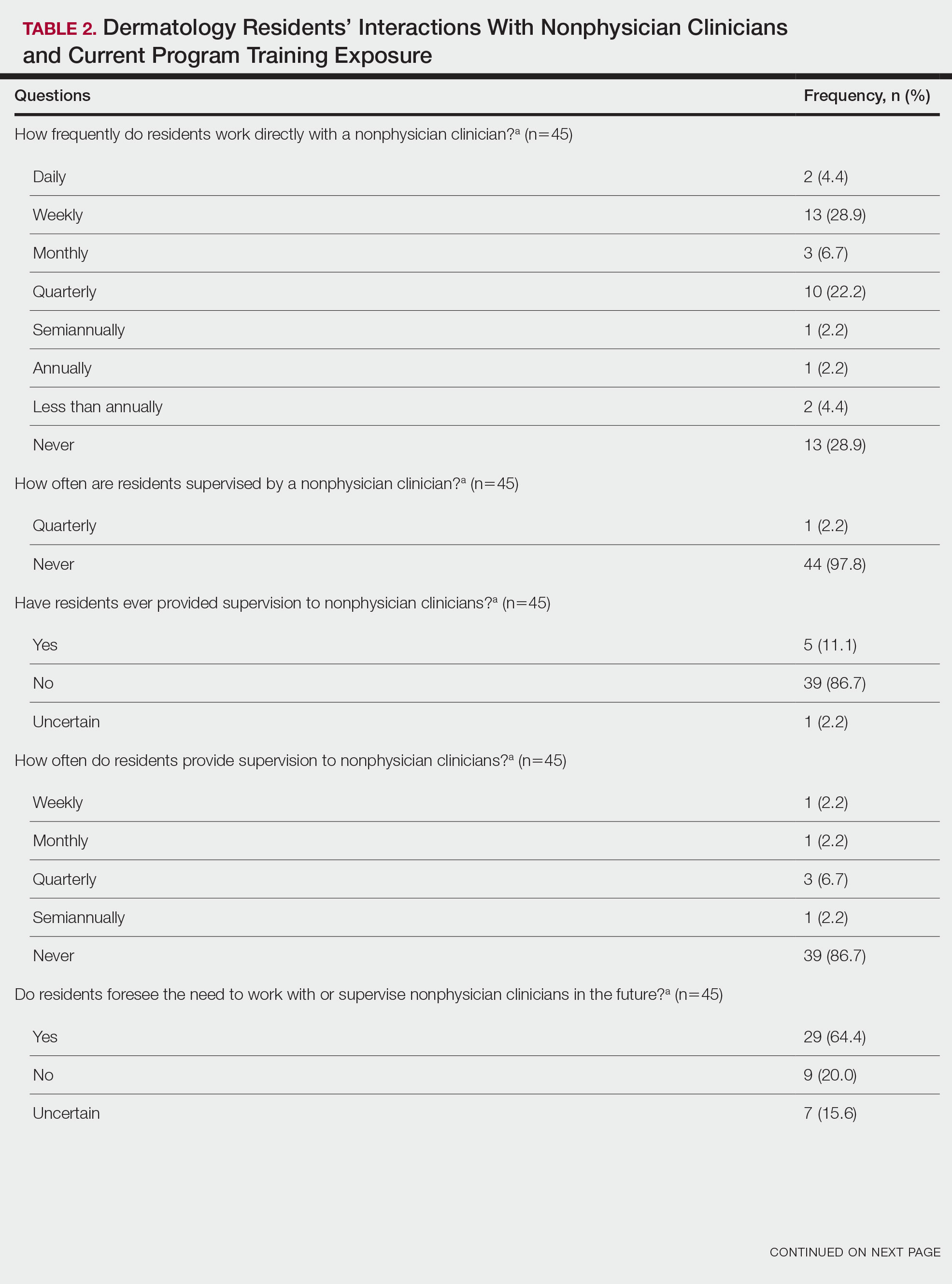

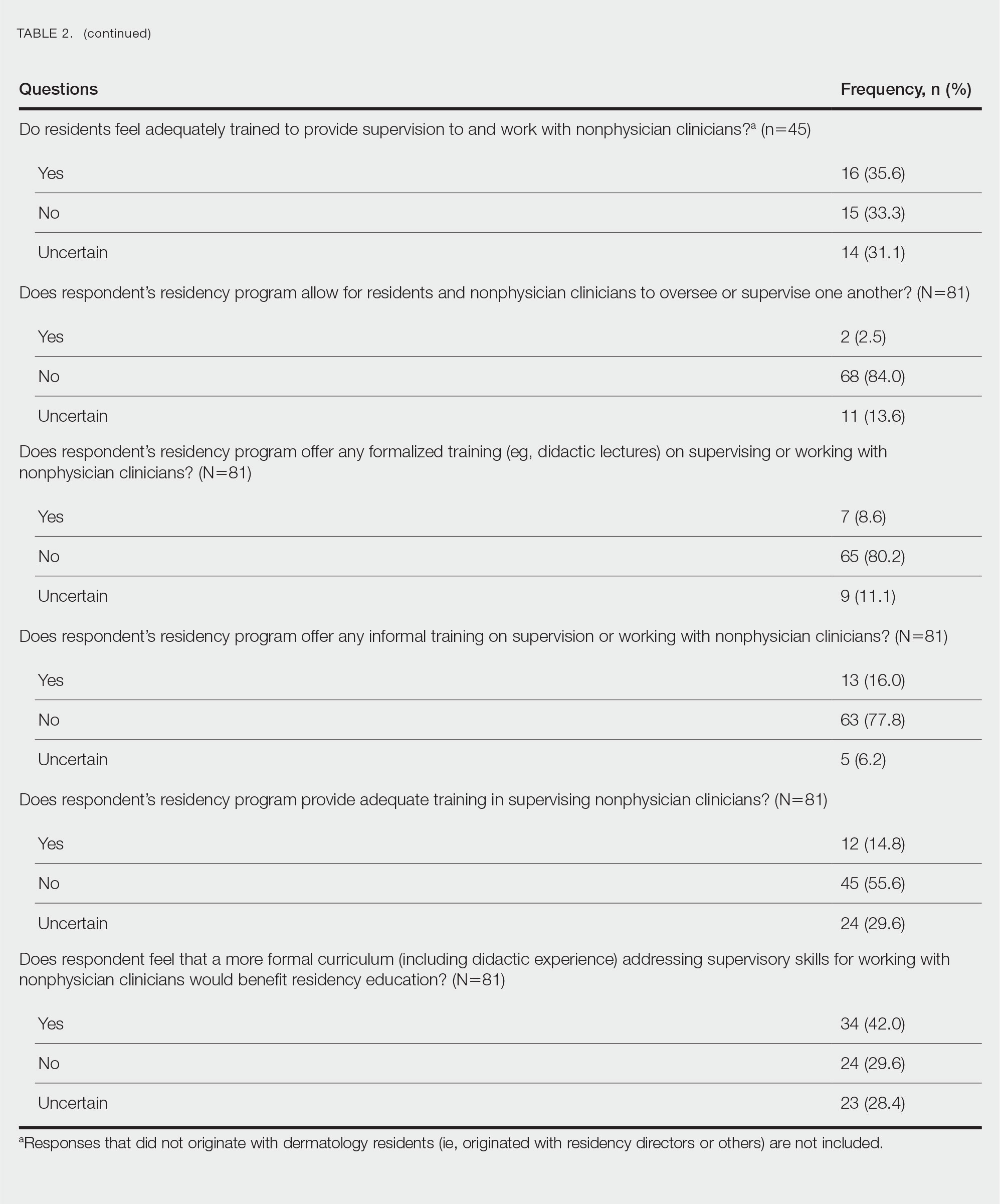

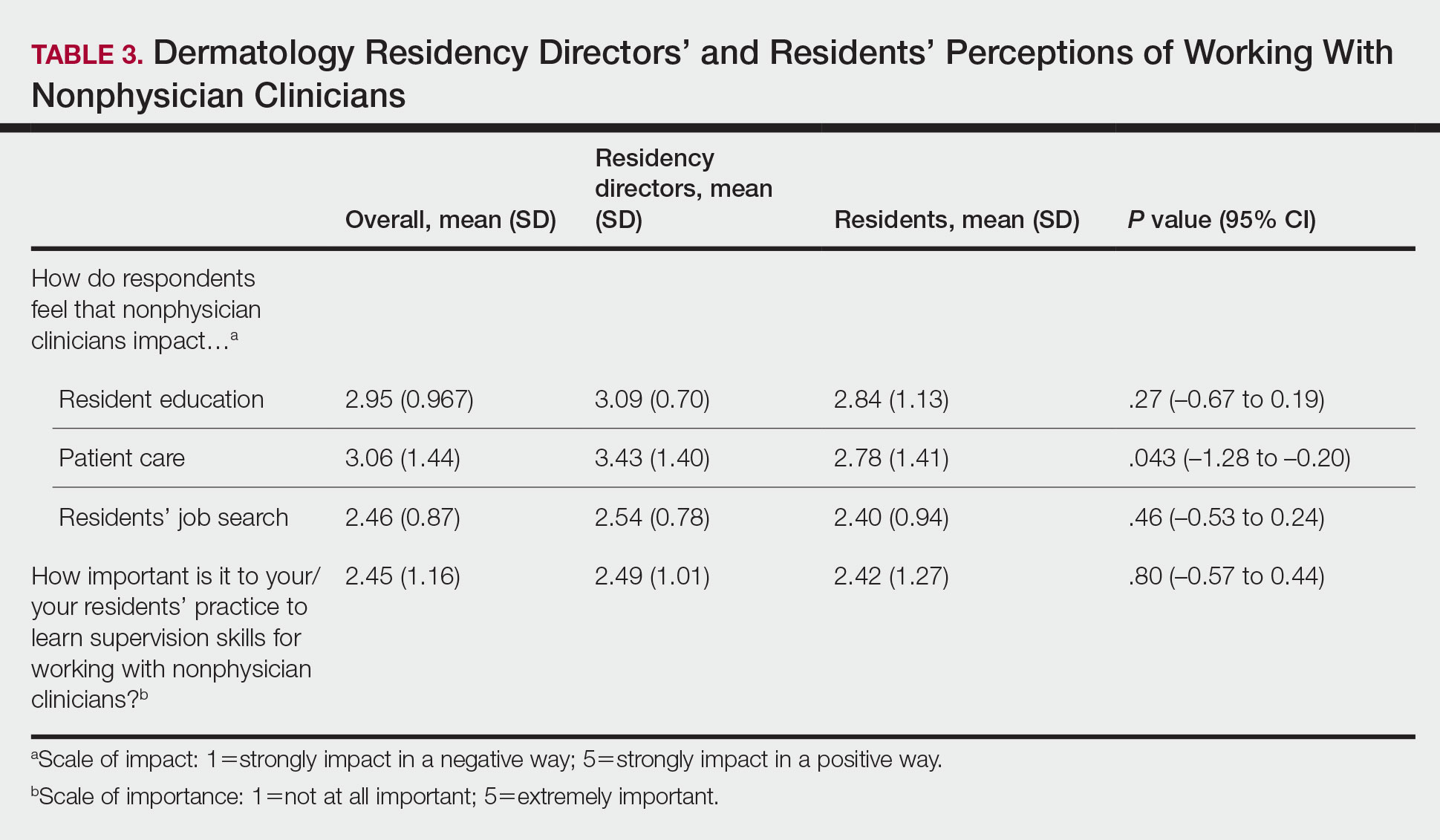

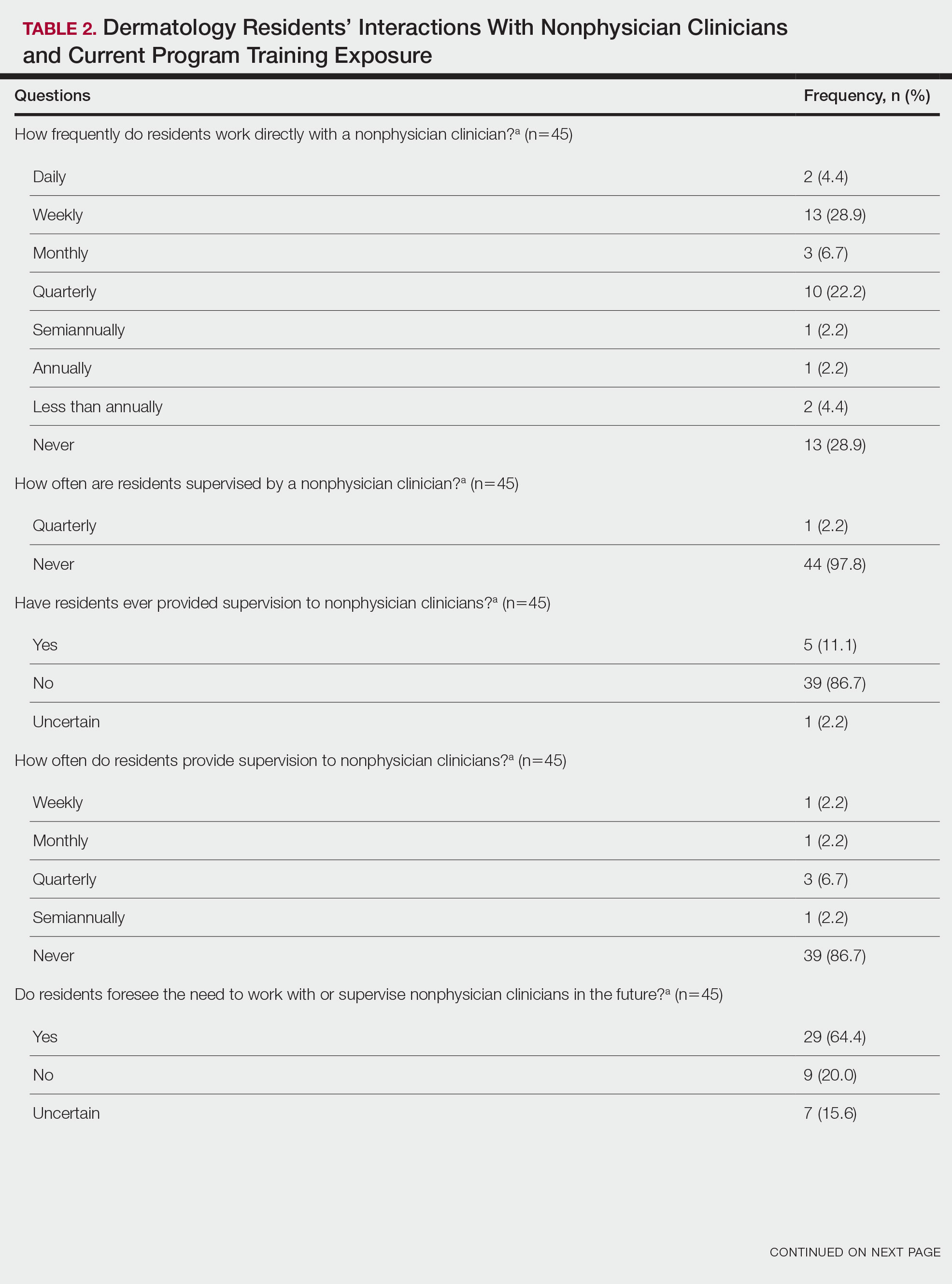

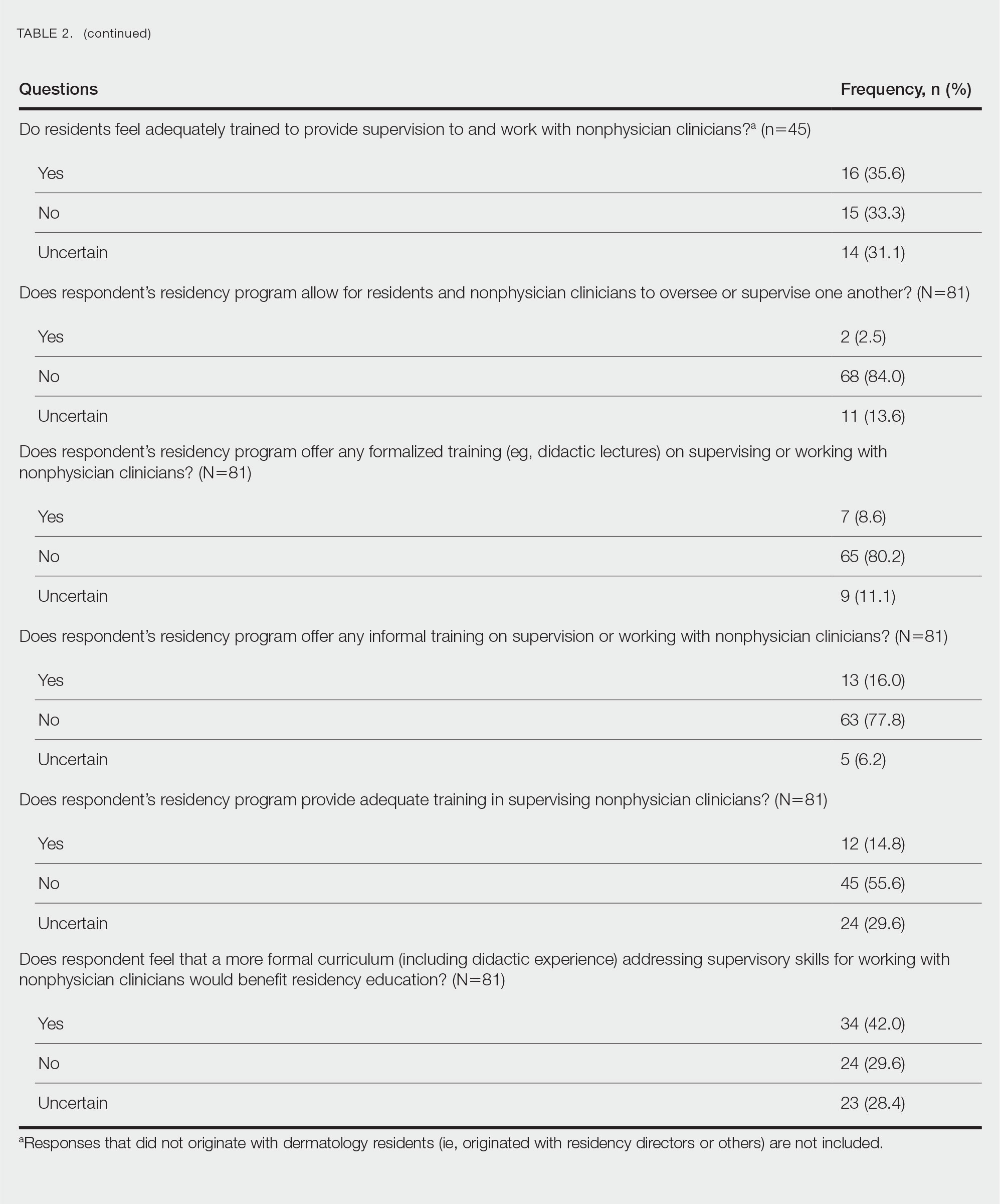

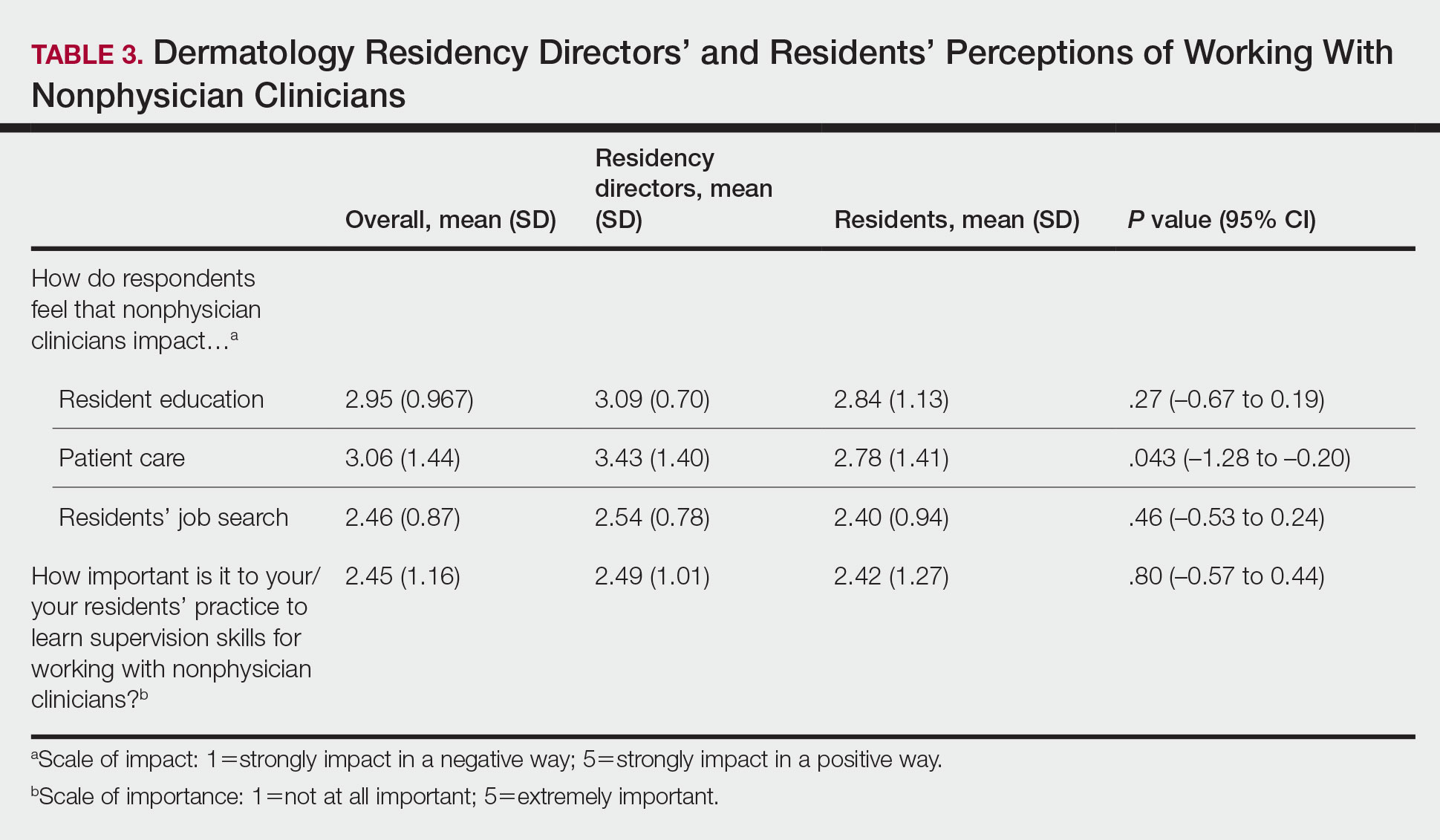

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

- Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

- Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

- Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/ articles/medical-assisting-trends/

- Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

- Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medicalassisting-history/

- Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

- Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

- Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

- Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

- STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/ fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_ combined.pdf

- Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

- Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

- Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

- Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ oes/current/oes319092.htm

- Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

- Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

- Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

- Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11: 187-201.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

- O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

- Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

- Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

- Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/ articles/medical-assisting-trends/

- Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

- Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medicalassisting-history/

- Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

- Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

- Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

- Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

- STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/ fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_ combined.pdf

- Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

- Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

- Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

- Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ oes/current/oes319092.htm

- Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

- Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

- Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

- Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11: 187-201.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

- O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

Author Q&A: Intravenous Immunoglobulin for Treatment of COVID-19 in Select Patients

Dr. George Sakoulas is an infectious diseases clinician at Sharp Memorial Hospital in San Diego and professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. He was the lead investigator in a study published in the May/June 2022 issue of JCOM that found that, when allocated to the appropriate patient type, intravenous immunoglobulin can reduce hospital costs for COVID-19 care. 1 He joined JCOM’s Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Ebrahim Barkoudah, to discuss the study’s background and highlight its main findings.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Dr. Barkoudah Dr. Sakoulas is an investigator and a clinician, bridging both worlds to bring the best evidence to our patients. We’re discussing his new article regarding intravenous immunoglobulin in treating nonventilated COVID-19 patients with moderate-to-severe hypoxia. Dr. Sakoulas, could you please share with our readers the clinical question your study addressed and what your work around COVID-19 management means for clinical practice?

Dr. Sakoulas Thank you. I’m an infectious disease physician. I’ve been treating patients with viral acute respiratory distress syndrome for almost 20 years as an ID doctor. Most of these cases are due to influenza or other viruses. And from time to time, anecdotally and supported by some literature, we’ve been using IVIG, or intravenous immunoglobulin, in some of these cases. And again, I can report anecdotal success with that over the years.

So when COVID emerged in March of 2020, we deployed IVIG in a couple of patients early who were heading downhill. Remember, in March of 2020, we didn’t have the knowledge of steroids helping, patients being ventilated very promptly, and we saw some patients who made a turnaround after treatment with IVIG. We were able to get some support from an industry sponsor and perform and publish a pilot study, enrolling patients early in the pandemic. That study actually showed benefits, which then led the sponsor to fund a phase 3 multicenter clinical trial. Unfortunately, a couple of things happened. First, the trial was designed with the knowledge we had in April of 2020, and again, this is before steroids, before we incorporated proning patients in the ICU, or started ventilating people early. So there were some management changes and evolutions and improvements that happened. And second, the trial was enrolling a very broad repertoire of patients. There were no age limitations, and the trial, ultimately a phase 3 multicenter trial, failed to meet its endpoint.

There were some trends for benefit in younger patients, and as the trial was ongoing, we continued to evolve our knowledge, and we really honed it down to seeing a benefit of using IVIG in patients with COVID with specific criteria in mind. They had to be relatively younger patients, under 65, and not have any major comorbidities. In other words, they weren’t dialysis patients or end-stage disease patients, heart failure patients, cancer or malignancy patients. So, you know, we’re looking at the patients under 65 with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, who are rapidly declining, going from room air to BiPAP or high-flow oxygen in a short amount of time. And we learned that when using IVIG early, we actually saw patients improve and turn around.

What this article in JCOM highlighted was, number one, incorporating that outcome or that patient type and then looking at the cost of hospitalization of patients who received IVIG versus those that did not. There were 2 groups that were studied. One was the group of patients in that original pilot trial that I discussed who were randomized to receive 1 or the other prospectively; it was an unblinded randomized study. And the second group was a matched case-control study where we had patients treated with IVIG matched by age and comorbidity status and level of hypoxia to patients that did not receive IVIG. We saw a financial benefit in shortening or reducing hospitalizations, really coming down to getting rid of that 20% tail of patients that wound up going to the ICU, getting intubated, and using a high amount of hospital resources that would ramp up the cost of hospitalization. We saw great mitigation of that with IVIG, and even with a small subset of patients, we were able to show a benefit.

Dr. Barkoudah Any thoughts on where we can implement the new findings from your article in our practice at the moment, knowing we now have practice guidelines and protocols to treat COVID-19? There was a tangible benefit in treating the patients the way you approached it in your important work. Could you share with us what would be implementable at the moment?

Dr. Sakoulas I think, fortunately, with the increasing host immunity in the population and decreased virulence of the virus, perhaps we won’t see as many patients of the type that were in these trials going forward, but I suspect we will perhaps in the unvaccinated patients that remain. I believe one-third of the United States is not vaccinated. So there is certainly a vulnerable group of people out there. Potentially, an unvaccinated patient who winds up getting very sick, the patient who is relatively young—what I’m looking at is the 30- to 65-year-old obese, hypertensive, or diabetic patient who comes in and, despite the steroids and the antivirals, rapidly deteriorates into requiring high-flow oxygen. I think implementing IVIG in that patient type would be helpful. I don’t think it’s going to be as helpful in patients who are very elderly, because I think the mechanism of the disease is different in an 80-year-old versus a 50-year-old patient. So again, hopefully, it will not amount to a lot of patients, but I still suspect hospitals are going to see, perhaps in the fall, when they’re expecting a greater number of cases, a trickling of patients that do meet the criteria that I described.

Dr. Barkoudah JCOM’s audience are the QI implementers and hospital leadership. And what caught my eye in your article is your perspective on the pharmacoeconomics of treating COVID-19, and I really appreciate your looking at the cost aspect. Would you talk about the economics of inpatient care, the total care that we provide now that we’re in the age of tocilizumab, and the current state of multiple layers of therapy?

Dr. Sakoulas The reason to look at the economics of it is because IVIG—which is actually not a drug, it’s a blood product—is very expensive. So, we received a considerable amount of administrative pushback implementing this treatment at the beginning outside of the clinical trial setting because it hadn’t been studied on a large scale and because the cost was so high, even though, as a clinician at the bedside, I was seeing a benefit in patients. This study came out of my trying to demonstrate to the folks that are keeping the economics of medicine in mind that, in fact, investing several thousand dollars of treatment in IVIG will save you cost of care, the cost of an ICU bed, the cost of a ventilator, and the cost even of ECMO, which is hugely expensive.

If you look at the numbers in the study, for two-thirds or three-quarters of the patients, your cost of care is actually greater than the controls because you’re giving them IVIG, and it’s increasing the cost of their care, even though three-quarters of the patients are going to do just as well without it. It’s that 20% to 25% of patients that really are going to benefit from it, where you’re reducing your cost of care so much, and you’re getting rid of that very, very expensive 20%, that there’s a cost savings across the board per patient. So, it’s hard to understand when you say you’re losing money on three-quarters of the patients, you’re only saving money on a quarter of the patients, but that cost of saving on that small subset is so substantial it’s really impacting all numbers.

Also, abandoning the outlier principle is sort of an underlying theme in how we think of things. We tend to ignore outliers, not consider them, but I think we really have to pay attention to the more extreme cases because those patients are the ones that drive not just the financial cost of care. Remember, if you’re down to 1 ventilator and you can cut down the use of scarce ICU resources, the cost is sort of even beyond the cost of money. It’s the cost of resources that may become scarce in some settings. So, I think it speaks to that as well.

A lot of the drugs that we use, for example, tocilizumab, were able to be studied in thousands of patients. If you look at the absolute numbers, the benefit of tocilizumab from a magnitude standpoint—low to mid twenties to high twenties—you know, reducing mortality from 29% to 24%. I mean, just take a step back and think about that. Even though it’s statistically significant, try telling a patient, “Well, I’m going to give you this treatment that’s going to reduce mortality from 29% to 24%.” You know, that doesn’t really change anything from a clinical significance standpoint. But they have a P value less than .05, which is our standard, and they were able to do a study with thousands of patients. We didn’t have that luxury with IVIG. No one studied thousands of patients, only retrospectively, and those retrospective studies don’t get the attention because they’re considered biased with all their limitations. But I think one of the difficulties we have here is the balance between statistical and clinical significance. For example, in our pilot study, our ventilation rate was 58% with the non-IVIG patients versus 14% for IVIG patients. So you might say, magnitude-wise, that’s a big number, but the statistical significance of it is borderline because of small numbers.

Anyway, that’s a challenge that we have as clinicians trying to incorporate what’s published—the balancing of statistics, absolute numbers, and practicalities of delivering care. And I think this study highlights some of the nuances that go into that incorporation and those clinical decisions.

Dr. Barkoudah Would you mind sharing with our audience how we can make the connection between the medical outcomes and pharmacoeconomics findings from your article and link it to the bedside and treatment of our patients?

Dr. Sakoulas One of the points this article brings out is the importance of bringing together not just level 1A data, but also small studies with data such as this, where the magnitude of the effect is pretty big but you lose the statistics because of the small numbers. And then also the patients’ aspects of things. I think, as a bedside clinician, you appreciate things, the nuances, much sooner than what percolates out from a level 1A study. Case in point, in the sponsored phase 3 study that we did, and in some other studies that were prospectively done as well, these studies of IVIG simply had an enrollment of patients that was very broad, and not every patient benefits from the same therapy. A great example of this is the sepsis trials with Xigris and those types of agents that failed. You know, there are clinicians to this day who believe that there is a subset of patients that benefit from agents like this. The IVIG story falls a little bit into that category. It comes down to trying to identify the subset of patients that might benefit. And I think we’ve outlined this subset pretty well in our study: the younger, obese diabetic or hypertensive patient who’s rapidly declining.

It really brings together the need to not necessarily toss out these smaller studies, but kind of summarize everything together, and clinicians who are bedside, who are more in tune with the nuances of individual decisions at the individual patient level, might better appreciate these kinds of data. But I think we all have to put it together. IVIG does not make treatment guidelines at national levels and so forth. It’s not even listed in many of them. But there are patients out there who, if you ask them specifically how they felt, including a friend of mine who received the medication, there’s no question from their end, how they felt about this treatment option. Now, some people will get it and will not benefit. We just have to be really tuned into the fact that the same drug does not have the same result for every patient. And just to consider this in the high-risk patients that we talked about in our study.

Dr. Barkoudah While we were prepping for this interview, you made an analogy regarding clinical evidence along the lines of, “Do we need randomized clinical trials to do a parachute-type of experiment,” and we chatted about clinical wisdom. Would you mind sharing with our readers your thoughts on that?

Dr. Sakoulas Sometimes, we try a treatment and it’s very obvious for that particular patient that it helped them. Then you study the treatment in a large trial setting and it doesn’t work. For us bedside clinicians, there are some interventions sometimes that do appear as beneficial as a parachute would be, but yet, there has never been a randomized clinical trial proving that parachutes work. Again, a part of the challenge we have is patients are so different, their immunology is different, the pathogen infecting them is different, the time they present is different. Some present early, some present late. There are just so many moving parts to treating an infection that only a subset of people are going to benefit. And sometimes as clinicians, we’re so nuanced, that we identify a specific subset of patients where we know we can help them. And it’s so obvious for us, like a parachute would be, but to people who are looking at the world from 30,000 feet, they don’t necessarily grasp that because, when you look at all comers, it doesn’t show a benefit.

So the problem is that now those treatments that might help a subset of patients are being denied, and the subset of patients that are going to benefit never get the treatment. Now we have to balance that with a lot of stuff that went on during the pandemic with, you know, ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, and people pushing those things. Someone asked me once what I thought about hydroxychloroquine, and I said, “Well, somebody in the lab probably showed that it was beneficial, analogous to lighting tissue paper on fire on a plate and taking a cup of water and putting the fire out. Well, now, if you take that cup of water to the Caldor fire that’s burning in California on thousands of acres, you’re not going to be able to put the fire out with that cup of water.” So while it might work in the lab, it’s truly not going to work in a clinical setting. We have to balance individualizing care for patients with some information people are pushing out there that may not be necessarily translatable to the clinical setting.

I think there’s nothing better than being at the bedside, though, and being able to implement something and seeing what works. And really, experience goes a long way in being able to individually treat a patient optimally.

Dr. Barkoudah Thank you for everything you do at the bedside and your work on improving the treatment we have and how we can leverage knowledge to treat our patients. Thank you very much for your time and your scholarly contribution. We appreciate it and I hope the work will continue. We will keep working on treating COVID-19 patients with the best knowledge we have.

Q&A participants: George Sakoulas, MD, Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group, La Jolla, CA, and University of California San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA; and Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Poremba M, Dehner M, Perreiter A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in treating nonventilated COVID-19 patients with moderate-to-severe hypoxia: a pharmacoeconomic analysis. J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2022;29(3):123-129. doi:10.12788/jcom.0094

Dr. George Sakoulas is an infectious diseases clinician at Sharp Memorial Hospital in San Diego and professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. He was the lead investigator in a study published in the May/June 2022 issue of JCOM that found that, when allocated to the appropriate patient type, intravenous immunoglobulin can reduce hospital costs for COVID-19 care. 1 He joined JCOM’s Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Ebrahim Barkoudah, to discuss the study’s background and highlight its main findings.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Dr. Barkoudah Dr. Sakoulas is an investigator and a clinician, bridging both worlds to bring the best evidence to our patients. We’re discussing his new article regarding intravenous immunoglobulin in treating nonventilated COVID-19 patients with moderate-to-severe hypoxia. Dr. Sakoulas, could you please share with our readers the clinical question your study addressed and what your work around COVID-19 management means for clinical practice?

Dr. Sakoulas Thank you. I’m an infectious disease physician. I’ve been treating patients with viral acute respiratory distress syndrome for almost 20 years as an ID doctor. Most of these cases are due to influenza or other viruses. And from time to time, anecdotally and supported by some literature, we’ve been using IVIG, or intravenous immunoglobulin, in some of these cases. And again, I can report anecdotal success with that over the years.

So when COVID emerged in March of 2020, we deployed IVIG in a couple of patients early who were heading downhill. Remember, in March of 2020, we didn’t have the knowledge of steroids helping, patients being ventilated very promptly, and we saw some patients who made a turnaround after treatment with IVIG. We were able to get some support from an industry sponsor and perform and publish a pilot study, enrolling patients early in the pandemic. That study actually showed benefits, which then led the sponsor to fund a phase 3 multicenter clinical trial. Unfortunately, a couple of things happened. First, the trial was designed with the knowledge we had in April of 2020, and again, this is before steroids, before we incorporated proning patients in the ICU, or started ventilating people early. So there were some management changes and evolutions and improvements that happened. And second, the trial was enrolling a very broad repertoire of patients. There were no age limitations, and the trial, ultimately a phase 3 multicenter trial, failed to meet its endpoint.

There were some trends for benefit in younger patients, and as the trial was ongoing, we continued to evolve our knowledge, and we really honed it down to seeing a benefit of using IVIG in patients with COVID with specific criteria in mind. They had to be relatively younger patients, under 65, and not have any major comorbidities. In other words, they weren’t dialysis patients or end-stage disease patients, heart failure patients, cancer or malignancy patients. So, you know, we’re looking at the patients under 65 with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, who are rapidly declining, going from room air to BiPAP or high-flow oxygen in a short amount of time. And we learned that when using IVIG early, we actually saw patients improve and turn around.