User login

High-dose progesterone to reverse mifepristone held still 'experimental'

A study of high-dose progesterone as a mifepristone antagonist to reverse medical abortion has been stopped early because of safety concerns, but the authors say mifepristone antagonization should not be considered impossible.

In Obstetrics & Gynecology, Mitchell D. Creinin, MD, of the University of California, Davis, and coauthors reported the outcomes of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy and safety of high-dose oral progesterone as a mifepristone antagonist. The study intended to enroll more women at 44–63 days of gestation who were planning surgical abortion, but stopped enrolling after 12 patients because of hemorrhage concerns.

Women were given a 200-mg dose of oral mifepristone, then randomized to either 200 mg oral progesterone or placebo 24 hours later, taken twice daily for 3 days then once daily until their planned surgical abortion 14-16 days after enrollment.

The approved method of medical abortion in the United States involves a combination of mifepristone followed by the prostaglandin analogue misoprostol 24-48 hours later, a combination designed to improve efficacy of the treatment.

There have been reports of some patients changing their minds in between taking the mifepristone and the misoprostol. The fact that mifepristone binds strongly to the progesterone receptor has led to the idea that its action could be reversed with high-dose progesterone as an antagonist.

In this study, three women – two in the placebo group and one in the progesterone group – experienced severe bleeding requiring ambulance transport to the emergency department 2-3 days after taking the mifepristone.

The study found that four of the six patients in the progesterone group, and two of the six patients in the placebo group had continuing pregnancies at 2 weeks.

There were two patients – one in each group – who did not complete the study. One in the placebo group left after taking the mifepristone because of anxiety about bleeding, and had a suction aspiration. The second women completed two of the four doses of progesterone, then requested a suction aspiration.

Dr. Creinin and coauthors wrote that while the study ended early, they found that there were no significant differences in the side effects experienced by patients treated with progesterone, compared with those on placebo – apart from a worsening of some pregnancy symptoms such as vomiting and tiredness.

However, patients should be told of the risk of using mifepristone for medical abortion without using misoprostol, they said, as this was associated with severe hemorrhage even with progesterone treatment.

“Because of the potential dangers for patients who opt not to use misoprostol after mifepristone ingestion, any mifepristone antagonization treatment must be considered experimental,” Dr. Creinin and associates wrote.

The Society of Family Planning Research Fund supported the study. One author declared a consultancy with a laboratory providing medical consultation for clinicians regarding mifepristone, and a second author was an employee of Planned Parenthood. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Creinin M et al. Obstet Gynecol 2019 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003620.

I think that this study highlights the importance of scientific rigor approved by an institutional review board when we counsel and care for our patients. As ob.gyns., we have to remember the privilege that women entrust us with their health and well being. To a certain extent, we also care for their families within our scope of reproductive health. We practice based on the best evidence available and consider referral to another trusted provider when we feel that we cannot provide unbiased care. I also feel obligated to share my opinion that legislators should trust the scientific and clinical community to not only prioritize women and their health, but also avoid introducing legislation that infringes on medicine.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She was asked to comment on the Creinin et al. article. Dr. Cansino is on the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

I think that this study highlights the importance of scientific rigor approved by an institutional review board when we counsel and care for our patients. As ob.gyns., we have to remember the privilege that women entrust us with their health and well being. To a certain extent, we also care for their families within our scope of reproductive health. We practice based on the best evidence available and consider referral to another trusted provider when we feel that we cannot provide unbiased care. I also feel obligated to share my opinion that legislators should trust the scientific and clinical community to not only prioritize women and their health, but also avoid introducing legislation that infringes on medicine.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She was asked to comment on the Creinin et al. article. Dr. Cansino is on the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

I think that this study highlights the importance of scientific rigor approved by an institutional review board when we counsel and care for our patients. As ob.gyns., we have to remember the privilege that women entrust us with their health and well being. To a certain extent, we also care for their families within our scope of reproductive health. We practice based on the best evidence available and consider referral to another trusted provider when we feel that we cannot provide unbiased care. I also feel obligated to share my opinion that legislators should trust the scientific and clinical community to not only prioritize women and their health, but also avoid introducing legislation that infringes on medicine.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She was asked to comment on the Creinin et al. article. Dr. Cansino is on the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

A study of high-dose progesterone as a mifepristone antagonist to reverse medical abortion has been stopped early because of safety concerns, but the authors say mifepristone antagonization should not be considered impossible.

In Obstetrics & Gynecology, Mitchell D. Creinin, MD, of the University of California, Davis, and coauthors reported the outcomes of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy and safety of high-dose oral progesterone as a mifepristone antagonist. The study intended to enroll more women at 44–63 days of gestation who were planning surgical abortion, but stopped enrolling after 12 patients because of hemorrhage concerns.

Women were given a 200-mg dose of oral mifepristone, then randomized to either 200 mg oral progesterone or placebo 24 hours later, taken twice daily for 3 days then once daily until their planned surgical abortion 14-16 days after enrollment.

The approved method of medical abortion in the United States involves a combination of mifepristone followed by the prostaglandin analogue misoprostol 24-48 hours later, a combination designed to improve efficacy of the treatment.

There have been reports of some patients changing their minds in between taking the mifepristone and the misoprostol. The fact that mifepristone binds strongly to the progesterone receptor has led to the idea that its action could be reversed with high-dose progesterone as an antagonist.

In this study, three women – two in the placebo group and one in the progesterone group – experienced severe bleeding requiring ambulance transport to the emergency department 2-3 days after taking the mifepristone.

The study found that four of the six patients in the progesterone group, and two of the six patients in the placebo group had continuing pregnancies at 2 weeks.

There were two patients – one in each group – who did not complete the study. One in the placebo group left after taking the mifepristone because of anxiety about bleeding, and had a suction aspiration. The second women completed two of the four doses of progesterone, then requested a suction aspiration.

Dr. Creinin and coauthors wrote that while the study ended early, they found that there were no significant differences in the side effects experienced by patients treated with progesterone, compared with those on placebo – apart from a worsening of some pregnancy symptoms such as vomiting and tiredness.

However, patients should be told of the risk of using mifepristone for medical abortion without using misoprostol, they said, as this was associated with severe hemorrhage even with progesterone treatment.

“Because of the potential dangers for patients who opt not to use misoprostol after mifepristone ingestion, any mifepristone antagonization treatment must be considered experimental,” Dr. Creinin and associates wrote.

The Society of Family Planning Research Fund supported the study. One author declared a consultancy with a laboratory providing medical consultation for clinicians regarding mifepristone, and a second author was an employee of Planned Parenthood. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Creinin M et al. Obstet Gynecol 2019 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003620.

A study of high-dose progesterone as a mifepristone antagonist to reverse medical abortion has been stopped early because of safety concerns, but the authors say mifepristone antagonization should not be considered impossible.

In Obstetrics & Gynecology, Mitchell D. Creinin, MD, of the University of California, Davis, and coauthors reported the outcomes of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy and safety of high-dose oral progesterone as a mifepristone antagonist. The study intended to enroll more women at 44–63 days of gestation who were planning surgical abortion, but stopped enrolling after 12 patients because of hemorrhage concerns.

Women were given a 200-mg dose of oral mifepristone, then randomized to either 200 mg oral progesterone or placebo 24 hours later, taken twice daily for 3 days then once daily until their planned surgical abortion 14-16 days after enrollment.

The approved method of medical abortion in the United States involves a combination of mifepristone followed by the prostaglandin analogue misoprostol 24-48 hours later, a combination designed to improve efficacy of the treatment.

There have been reports of some patients changing their minds in between taking the mifepristone and the misoprostol. The fact that mifepristone binds strongly to the progesterone receptor has led to the idea that its action could be reversed with high-dose progesterone as an antagonist.

In this study, three women – two in the placebo group and one in the progesterone group – experienced severe bleeding requiring ambulance transport to the emergency department 2-3 days after taking the mifepristone.

The study found that four of the six patients in the progesterone group, and two of the six patients in the placebo group had continuing pregnancies at 2 weeks.

There were two patients – one in each group – who did not complete the study. One in the placebo group left after taking the mifepristone because of anxiety about bleeding, and had a suction aspiration. The second women completed two of the four doses of progesterone, then requested a suction aspiration.

Dr. Creinin and coauthors wrote that while the study ended early, they found that there were no significant differences in the side effects experienced by patients treated with progesterone, compared with those on placebo – apart from a worsening of some pregnancy symptoms such as vomiting and tiredness.

However, patients should be told of the risk of using mifepristone for medical abortion without using misoprostol, they said, as this was associated with severe hemorrhage even with progesterone treatment.

“Because of the potential dangers for patients who opt not to use misoprostol after mifepristone ingestion, any mifepristone antagonization treatment must be considered experimental,” Dr. Creinin and associates wrote.

The Society of Family Planning Research Fund supported the study. One author declared a consultancy with a laboratory providing medical consultation for clinicians regarding mifepristone, and a second author was an employee of Planned Parenthood. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Creinin M et al. Obstet Gynecol 2019 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003620.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

iPLEDGE vexes dermatologists treating transgender patients

Physicians treating transgender patients – in particular, transgender men who were born female – are faced with a confusing process when prescribing isotretinoin for severe acne.

A research letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology reports that established to prevent female patients from starting isotretinoin therapy while pregnant or from becoming pregnant while exposed to the teratogenic medication.

Nearly 90% of respondents favored changing the current gender-specific categories in iPLEDGE to gender-neutral ones, classifying patients only by whether or not they have the ability to become pregnant.

For their research, Courtney Ensslin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues, distributed an 18-point questionnaire to 385 members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology that included questions assessing clinicians’ knowledge about the reproductive potential of transgender men and women. The recipients were asked to distribute it to faculty members and residents. The survey also described three clinical scenarios in which the physician needed to decide how to register a patient in iPLEDGE. The clinicians largely opted to class transgender men as women with childbearing potential, even if the category conflicted with the patient’s self-identified and legally recognized male gender.

Of the 136 clinicians who responded, 60% were women, almost half were aged 25-34 years. About 12% of respondents said the complexities of prescribing isotretinoin to a transgender patient led them to choose alternative therapies. And the survey revealed some gaps on providers’ general literacy on transgender patients and their reproductive potential. For example, fewer than a third of respondents answered correctly as to whether testosterone treatment decreases the quality and development of an immature ovum.

The researchers wrote that the survey results, while limited by a small sample of respondents that skewed toward younger women providers, suggest that “continued education on fertility in transgender patients is needed because prescribers must fully understand each patient’s reproductive potential to safely prescribe teratogenic medications.” Additionally, they pointed out, the results support ongoing efforts to reform iPLEDGE, as the current categories “do not offer an inclusive approach to care for transgender patients.”

Earlier this year the American Academy of Dermatology issued a position statement that described a number of ongoing initiatives aimed at improving treatment for patients who are members of gender and sexual minorities. These included the “revision of the AAD position statement on isotretinoin to support a gender-neutral categorization model for [iPLEDGE] … based on child-bearing potential rather than on gender identity,” the statement said.

Dr. Ensslin and colleagues reported conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Ensslin C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1426-9.

Physicians treating transgender patients – in particular, transgender men who were born female – are faced with a confusing process when prescribing isotretinoin for severe acne.

A research letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology reports that established to prevent female patients from starting isotretinoin therapy while pregnant or from becoming pregnant while exposed to the teratogenic medication.

Nearly 90% of respondents favored changing the current gender-specific categories in iPLEDGE to gender-neutral ones, classifying patients only by whether or not they have the ability to become pregnant.

For their research, Courtney Ensslin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues, distributed an 18-point questionnaire to 385 members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology that included questions assessing clinicians’ knowledge about the reproductive potential of transgender men and women. The recipients were asked to distribute it to faculty members and residents. The survey also described three clinical scenarios in which the physician needed to decide how to register a patient in iPLEDGE. The clinicians largely opted to class transgender men as women with childbearing potential, even if the category conflicted with the patient’s self-identified and legally recognized male gender.

Of the 136 clinicians who responded, 60% were women, almost half were aged 25-34 years. About 12% of respondents said the complexities of prescribing isotretinoin to a transgender patient led them to choose alternative therapies. And the survey revealed some gaps on providers’ general literacy on transgender patients and their reproductive potential. For example, fewer than a third of respondents answered correctly as to whether testosterone treatment decreases the quality and development of an immature ovum.

The researchers wrote that the survey results, while limited by a small sample of respondents that skewed toward younger women providers, suggest that “continued education on fertility in transgender patients is needed because prescribers must fully understand each patient’s reproductive potential to safely prescribe teratogenic medications.” Additionally, they pointed out, the results support ongoing efforts to reform iPLEDGE, as the current categories “do not offer an inclusive approach to care for transgender patients.”

Earlier this year the American Academy of Dermatology issued a position statement that described a number of ongoing initiatives aimed at improving treatment for patients who are members of gender and sexual minorities. These included the “revision of the AAD position statement on isotretinoin to support a gender-neutral categorization model for [iPLEDGE] … based on child-bearing potential rather than on gender identity,” the statement said.

Dr. Ensslin and colleagues reported conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Ensslin C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1426-9.

Physicians treating transgender patients – in particular, transgender men who were born female – are faced with a confusing process when prescribing isotretinoin for severe acne.

A research letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology reports that established to prevent female patients from starting isotretinoin therapy while pregnant or from becoming pregnant while exposed to the teratogenic medication.

Nearly 90% of respondents favored changing the current gender-specific categories in iPLEDGE to gender-neutral ones, classifying patients only by whether or not they have the ability to become pregnant.

For their research, Courtney Ensslin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues, distributed an 18-point questionnaire to 385 members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology that included questions assessing clinicians’ knowledge about the reproductive potential of transgender men and women. The recipients were asked to distribute it to faculty members and residents. The survey also described three clinical scenarios in which the physician needed to decide how to register a patient in iPLEDGE. The clinicians largely opted to class transgender men as women with childbearing potential, even if the category conflicted with the patient’s self-identified and legally recognized male gender.

Of the 136 clinicians who responded, 60% were women, almost half were aged 25-34 years. About 12% of respondents said the complexities of prescribing isotretinoin to a transgender patient led them to choose alternative therapies. And the survey revealed some gaps on providers’ general literacy on transgender patients and their reproductive potential. For example, fewer than a third of respondents answered correctly as to whether testosterone treatment decreases the quality and development of an immature ovum.

The researchers wrote that the survey results, while limited by a small sample of respondents that skewed toward younger women providers, suggest that “continued education on fertility in transgender patients is needed because prescribers must fully understand each patient’s reproductive potential to safely prescribe teratogenic medications.” Additionally, they pointed out, the results support ongoing efforts to reform iPLEDGE, as the current categories “do not offer an inclusive approach to care for transgender patients.”

Earlier this year the American Academy of Dermatology issued a position statement that described a number of ongoing initiatives aimed at improving treatment for patients who are members of gender and sexual minorities. These included the “revision of the AAD position statement on isotretinoin to support a gender-neutral categorization model for [iPLEDGE] … based on child-bearing potential rather than on gender identity,” the statement said.

Dr. Ensslin and colleagues reported conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Ensslin C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1426-9.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Poll: Do you agree that hormonal contraception (OCPs, progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and DMPA) should be offered OTC?

[polldaddy:10476065]

[polldaddy:10476065]

[polldaddy:10476065]

Oral contraceptive use associated with smaller hypothalamic and pituitary volumes

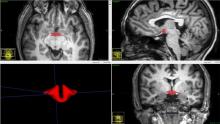

CHICAGO – Women taking oral contraceptives had, on average, a hypothalamus that was 6% smaller than those who didn’t, in a small study that used magnetic resonance imaging. Pituitary volume was also smaller.

Though the sample size was relatively small, 50 women in total, it’s the only study to date that looks at the relationship between hypothalamic volume and oral contraceptive (OC) use, and the largest examining pituitary volume, according to Ke Xun (Kevin) Chen, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Using MRI, Dr. Chen and his colleagues found that hypothalamic volume was significantly smaller in women taking oral contraceptives than those who were naturally cycling (b value = –64.1; P = .006). The pituitary gland also was significantly smaller in those taking OCs (b = –92.8; P = .007).

“I was quite surprised [at the finding], because the magnitude of the effect is not small,” especially in the context of changes in volume of other brain structures, senior author Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD, said in an interview. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, a volume loss of 4% annually can be expected.

However, “it’s not shocking to me in a negative way at all. I can’t tell you what it means in terms of how it’s going to affect people,” since this is a cross-sectional study that only detected a correlation and can’t say anything about a causative relationship, he added. “We don’t even know that [OCs] cause this effect. ... It’s plausible that this is just a plasticity-related change that’s simply showing us the effect of the drug.

“We’re going to be much more careful to consider oral contraceptive use as a covariate in future research studies; that’s for sure,” he said.

Although OCs have been available since their 1960 Food and Drug Administration approval, and their effects in some areas of physiology and health have been well studied, there’s still not much known about how oral contraceptives affect brain function, said Dr. Lipton, professor of neuroradiology and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in the Montefiore medical system, New York.

The spark for this study came from one of Dr. Lipton’s main areas of research – sex differences in susceptibility to and recovery from traumatic brain injury. “Women are more likely to exhibit changes in their brain [after injury] – and changes in their brain function – than men,” he said.

In the present study, “we went at this trying to understand the effect to which the hormone effect might be doing something in regular, healthy people that we need to consider as part of the bigger picture,” he said.

Dr. Lipton, Dr. Chen (then a radiology resident at Albert Einstein College of Medicine), and their coauthors constructed the study to look for differences in brain structure between women who were experiencing natural menstrual cycles and those who were taking exogenous hormones, to begin to learn how oral contraceptive use might modify risk and susceptibility for neurologic disease and injury.

It had already been established that global brain volume didn’t differ between naturally cycling women and those using OCs. However, some studies had shown differences in volume of some specific brain regions, and one study had shown smaller pituitary volume in OC users, according to the presentation by Dr. Chen, who is now a radiology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Accurately measuring hypothalamic volume represents a technical challenge, and the effect of OCs on the structure’s volume hadn’t previously been studied.

Sex hormones, said Dr. Lipton, have known trophic effects on brain tissue and ovarian sex hormones cross the blood brain barrier, so the idea that there would be some plasticity in the brains of those taking OCs wasn’t completely surprising, especially since there are hormone receptors that lie within the central nervous system. However, he said he was “very surprised” by the effect size seen in the study.

The study included 21 healthy women taking combined oral contraceptives, and 29 naturally cycling women. Participants’ mean age was 23 years for the OC users, and 21 for the naturally cycling women. Body mass index and smoking history didn’t differ between groups. Women on OCs were significantly more likely to use alcohol and to drink more frequently than those not taking OCs (P = .001). Participants were included only if they were taking a combined estrogen-progestin pill; those on noncyclical contraceptives such as implants and hormone-emitting intrauterine devices were excluded, as were naturally cycling women with very long or irregular menstrual cycles.

After multivariable statistical analysis, the only two significant predictors of hypothalamic volume were total intracranial volume and OC use. For pituitary volume, body mass index and OC use remained significant.

In addition to the MRI scans, participants also completed neurobehavioral testing to assess mood and cognition. An exploratory analysis showed no correlation between hypothalamic volume and the cognitive testing battery results, which included assessments for verbal learning and memory, executive function, and working memory.

However, a moderate positive association was seen between hypothalamic volume and anger scores (r = 0.34; P = .02). The investigators found a “strong positive correlation of hypothalamic volume with depression,” said Dr. Chen (r = 0.25; P = .09).

The investigators found no menstrual cycle-related changes in hypothalamic and pituitary volume among naturally cycling women.

Hypothalamic volume was obtained using manual segmentation of the MRIs; a combined automated-manual approach was used to obtain pituitary volume. Reliability was tested by having 5 raters each assess volumes for a randomly selected subset of the scans; inter-rater reliability fell between 0.78 and 0.86, values considered to indicate “good” reliability.

In addition to the small sample size, Dr. Chen acknowledged several limitations to the study. These included the lack of accounting for details of OC use including duration, exact type of OC, and whether women were taking the placebo phase of their pill packs at the time of scanning. Additionally, women who were naturally cycling were not asked about prior history of OC use.

Also, women’s menstrual phase was estimated from the self-reported date of the last menstrual period, rather than obtained by direct measurement via serum hormone levels.

Dr. Lipton’s perspective adds a strong note of caution to avoid overinterpretation from the study. Dr. Chen and Dr. Lipton agreed, however, that OC use should be accounted for when brain structure and function are studied in female participants.

Dr. Chen, Dr. Lipton, and their coauthors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The authors reported no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Chen K et al. RSNA 2019. Presentation SSM-1904.

CHICAGO – Women taking oral contraceptives had, on average, a hypothalamus that was 6% smaller than those who didn’t, in a small study that used magnetic resonance imaging. Pituitary volume was also smaller.

Though the sample size was relatively small, 50 women in total, it’s the only study to date that looks at the relationship between hypothalamic volume and oral contraceptive (OC) use, and the largest examining pituitary volume, according to Ke Xun (Kevin) Chen, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Using MRI, Dr. Chen and his colleagues found that hypothalamic volume was significantly smaller in women taking oral contraceptives than those who were naturally cycling (b value = –64.1; P = .006). The pituitary gland also was significantly smaller in those taking OCs (b = –92.8; P = .007).

“I was quite surprised [at the finding], because the magnitude of the effect is not small,” especially in the context of changes in volume of other brain structures, senior author Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD, said in an interview. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, a volume loss of 4% annually can be expected.

However, “it’s not shocking to me in a negative way at all. I can’t tell you what it means in terms of how it’s going to affect people,” since this is a cross-sectional study that only detected a correlation and can’t say anything about a causative relationship, he added. “We don’t even know that [OCs] cause this effect. ... It’s plausible that this is just a plasticity-related change that’s simply showing us the effect of the drug.

“We’re going to be much more careful to consider oral contraceptive use as a covariate in future research studies; that’s for sure,” he said.

Although OCs have been available since their 1960 Food and Drug Administration approval, and their effects in some areas of physiology and health have been well studied, there’s still not much known about how oral contraceptives affect brain function, said Dr. Lipton, professor of neuroradiology and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in the Montefiore medical system, New York.

The spark for this study came from one of Dr. Lipton’s main areas of research – sex differences in susceptibility to and recovery from traumatic brain injury. “Women are more likely to exhibit changes in their brain [after injury] – and changes in their brain function – than men,” he said.

In the present study, “we went at this trying to understand the effect to which the hormone effect might be doing something in regular, healthy people that we need to consider as part of the bigger picture,” he said.

Dr. Lipton, Dr. Chen (then a radiology resident at Albert Einstein College of Medicine), and their coauthors constructed the study to look for differences in brain structure between women who were experiencing natural menstrual cycles and those who were taking exogenous hormones, to begin to learn how oral contraceptive use might modify risk and susceptibility for neurologic disease and injury.

It had already been established that global brain volume didn’t differ between naturally cycling women and those using OCs. However, some studies had shown differences in volume of some specific brain regions, and one study had shown smaller pituitary volume in OC users, according to the presentation by Dr. Chen, who is now a radiology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Accurately measuring hypothalamic volume represents a technical challenge, and the effect of OCs on the structure’s volume hadn’t previously been studied.

Sex hormones, said Dr. Lipton, have known trophic effects on brain tissue and ovarian sex hormones cross the blood brain barrier, so the idea that there would be some plasticity in the brains of those taking OCs wasn’t completely surprising, especially since there are hormone receptors that lie within the central nervous system. However, he said he was “very surprised” by the effect size seen in the study.

The study included 21 healthy women taking combined oral contraceptives, and 29 naturally cycling women. Participants’ mean age was 23 years for the OC users, and 21 for the naturally cycling women. Body mass index and smoking history didn’t differ between groups. Women on OCs were significantly more likely to use alcohol and to drink more frequently than those not taking OCs (P = .001). Participants were included only if they were taking a combined estrogen-progestin pill; those on noncyclical contraceptives such as implants and hormone-emitting intrauterine devices were excluded, as were naturally cycling women with very long or irregular menstrual cycles.

After multivariable statistical analysis, the only two significant predictors of hypothalamic volume were total intracranial volume and OC use. For pituitary volume, body mass index and OC use remained significant.

In addition to the MRI scans, participants also completed neurobehavioral testing to assess mood and cognition. An exploratory analysis showed no correlation between hypothalamic volume and the cognitive testing battery results, which included assessments for verbal learning and memory, executive function, and working memory.

However, a moderate positive association was seen between hypothalamic volume and anger scores (r = 0.34; P = .02). The investigators found a “strong positive correlation of hypothalamic volume with depression,” said Dr. Chen (r = 0.25; P = .09).

The investigators found no menstrual cycle-related changes in hypothalamic and pituitary volume among naturally cycling women.

Hypothalamic volume was obtained using manual segmentation of the MRIs; a combined automated-manual approach was used to obtain pituitary volume. Reliability was tested by having 5 raters each assess volumes for a randomly selected subset of the scans; inter-rater reliability fell between 0.78 and 0.86, values considered to indicate “good” reliability.

In addition to the small sample size, Dr. Chen acknowledged several limitations to the study. These included the lack of accounting for details of OC use including duration, exact type of OC, and whether women were taking the placebo phase of their pill packs at the time of scanning. Additionally, women who were naturally cycling were not asked about prior history of OC use.

Also, women’s menstrual phase was estimated from the self-reported date of the last menstrual period, rather than obtained by direct measurement via serum hormone levels.

Dr. Lipton’s perspective adds a strong note of caution to avoid overinterpretation from the study. Dr. Chen and Dr. Lipton agreed, however, that OC use should be accounted for when brain structure and function are studied in female participants.

Dr. Chen, Dr. Lipton, and their coauthors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The authors reported no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Chen K et al. RSNA 2019. Presentation SSM-1904.

CHICAGO – Women taking oral contraceptives had, on average, a hypothalamus that was 6% smaller than those who didn’t, in a small study that used magnetic resonance imaging. Pituitary volume was also smaller.

Though the sample size was relatively small, 50 women in total, it’s the only study to date that looks at the relationship between hypothalamic volume and oral contraceptive (OC) use, and the largest examining pituitary volume, according to Ke Xun (Kevin) Chen, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Using MRI, Dr. Chen and his colleagues found that hypothalamic volume was significantly smaller in women taking oral contraceptives than those who were naturally cycling (b value = –64.1; P = .006). The pituitary gland also was significantly smaller in those taking OCs (b = –92.8; P = .007).

“I was quite surprised [at the finding], because the magnitude of the effect is not small,” especially in the context of changes in volume of other brain structures, senior author Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD, said in an interview. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, a volume loss of 4% annually can be expected.

However, “it’s not shocking to me in a negative way at all. I can’t tell you what it means in terms of how it’s going to affect people,” since this is a cross-sectional study that only detected a correlation and can’t say anything about a causative relationship, he added. “We don’t even know that [OCs] cause this effect. ... It’s plausible that this is just a plasticity-related change that’s simply showing us the effect of the drug.

“We’re going to be much more careful to consider oral contraceptive use as a covariate in future research studies; that’s for sure,” he said.

Although OCs have been available since their 1960 Food and Drug Administration approval, and their effects in some areas of physiology and health have been well studied, there’s still not much known about how oral contraceptives affect brain function, said Dr. Lipton, professor of neuroradiology and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in the Montefiore medical system, New York.

The spark for this study came from one of Dr. Lipton’s main areas of research – sex differences in susceptibility to and recovery from traumatic brain injury. “Women are more likely to exhibit changes in their brain [after injury] – and changes in their brain function – than men,” he said.

In the present study, “we went at this trying to understand the effect to which the hormone effect might be doing something in regular, healthy people that we need to consider as part of the bigger picture,” he said.

Dr. Lipton, Dr. Chen (then a radiology resident at Albert Einstein College of Medicine), and their coauthors constructed the study to look for differences in brain structure between women who were experiencing natural menstrual cycles and those who were taking exogenous hormones, to begin to learn how oral contraceptive use might modify risk and susceptibility for neurologic disease and injury.

It had already been established that global brain volume didn’t differ between naturally cycling women and those using OCs. However, some studies had shown differences in volume of some specific brain regions, and one study had shown smaller pituitary volume in OC users, according to the presentation by Dr. Chen, who is now a radiology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Accurately measuring hypothalamic volume represents a technical challenge, and the effect of OCs on the structure’s volume hadn’t previously been studied.

Sex hormones, said Dr. Lipton, have known trophic effects on brain tissue and ovarian sex hormones cross the blood brain barrier, so the idea that there would be some plasticity in the brains of those taking OCs wasn’t completely surprising, especially since there are hormone receptors that lie within the central nervous system. However, he said he was “very surprised” by the effect size seen in the study.

The study included 21 healthy women taking combined oral contraceptives, and 29 naturally cycling women. Participants’ mean age was 23 years for the OC users, and 21 for the naturally cycling women. Body mass index and smoking history didn’t differ between groups. Women on OCs were significantly more likely to use alcohol and to drink more frequently than those not taking OCs (P = .001). Participants were included only if they were taking a combined estrogen-progestin pill; those on noncyclical contraceptives such as implants and hormone-emitting intrauterine devices were excluded, as were naturally cycling women with very long or irregular menstrual cycles.

After multivariable statistical analysis, the only two significant predictors of hypothalamic volume were total intracranial volume and OC use. For pituitary volume, body mass index and OC use remained significant.

In addition to the MRI scans, participants also completed neurobehavioral testing to assess mood and cognition. An exploratory analysis showed no correlation between hypothalamic volume and the cognitive testing battery results, which included assessments for verbal learning and memory, executive function, and working memory.

However, a moderate positive association was seen between hypothalamic volume and anger scores (r = 0.34; P = .02). The investigators found a “strong positive correlation of hypothalamic volume with depression,” said Dr. Chen (r = 0.25; P = .09).

The investigators found no menstrual cycle-related changes in hypothalamic and pituitary volume among naturally cycling women.

Hypothalamic volume was obtained using manual segmentation of the MRIs; a combined automated-manual approach was used to obtain pituitary volume. Reliability was tested by having 5 raters each assess volumes for a randomly selected subset of the scans; inter-rater reliability fell between 0.78 and 0.86, values considered to indicate “good” reliability.

In addition to the small sample size, Dr. Chen acknowledged several limitations to the study. These included the lack of accounting for details of OC use including duration, exact type of OC, and whether women were taking the placebo phase of their pill packs at the time of scanning. Additionally, women who were naturally cycling were not asked about prior history of OC use.

Also, women’s menstrual phase was estimated from the self-reported date of the last menstrual period, rather than obtained by direct measurement via serum hormone levels.

Dr. Lipton’s perspective adds a strong note of caution to avoid overinterpretation from the study. Dr. Chen and Dr. Lipton agreed, however, that OC use should be accounted for when brain structure and function are studied in female participants.

Dr. Chen, Dr. Lipton, and their coauthors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The authors reported no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Chen K et al. RSNA 2019. Presentation SSM-1904.

REPORTING FROM RSNA 2019

Learning about and prescribing emergency contraception

As health care providers to children, we always are learning. And with new knowledge we sometimes can be taken out of our comfort zone. One of those areas are teenagers, contraception, safe-sex counseling, and now emergency contraception (EC). In residency you have your 1-month adolescent medicine rotation to try and absorb every bit of information like a sponge, but there also will be a level of discomfort and uncertainty. However, as medical providers we cannot let the above prevent us from giving well-rounded and informed care.

When our teens disclose the most private moment of their life, we have to be armed and ready to not only comfort them, but advise and guide them to making a decision so that they can ensure their safety. The answers regarding sexual activity are becoming more and more alarming, especially in our younger patients. Therefore, this is an important discussion to have at every visit (not just well-child checks), so that education opportunities are not missed and our patients feel a sense of normalcy about discussing reproductive health with their health care provider and or parents.

We all have our personal beliefs, but we cannot let that guide our decision on what care or education we give our patients. Unfortunately, I have heard many health care providers judge our patients for their promiscuity, when we need to educate them – not be their judge and jury. Our teens go through different stages of growth and development, and with these stages come experimentation and risk taking. So as their health care providers, we need to be up to date on the information out there.

With regards with EC, some of our patients think that they can get it only after having unprotected sex. However, they should know that the oral ECs can be given to them at any time, so should they be in the situation above, they have an immediate remedy. With the different options come different counseling and different instructions on administration and follow-up. In residency, we might not have learned the skill of inserting an IUD, which is another form of EC; that is why there are many resources available. These resources include hands-on workshops, videos on counseling, and your friendly neighborhood adolescent medicine physician or ob.gyn.

EC can give our patients that sense of relief, especially when they have unprotected sex. However, they also need to have a sense of responsibility for their actions because you do not want them to engage in high-risk behaviors. Just as we are responsible to provide up-to-date care, our patients must take ownership of their health and well-being. Also If they are engaging in unprotected sex, they are just as responsible; therefore, they should know everything about contraception as well as EC. They should feel comfortable talking to their partners about contraception. Health care providers should make them feel comfortable receiving EC that they can give to their female partner.

We need to become knowledgeable and comfortable prescribing EC, as well as incorporating it in our routine care. This is a policy that I strongly believe should be part of every pediatrician’s and family physician’s office, especially when there is a lack of resources. Of the different options that are available, the oral forms of EC – especially Ella or Plan B step 1 (levonorgestrel) – would be the easiest to prescribe and counsel on. I would not recommend the options where multiple pills need to be taken more than once a day, because compliance becomes a factor. Also knowing that these options are available over the counter also is helpful because our community pharmacist also can help with medication administration and counseling.

In summary, I strongly recommend the discussion of EC in the office, especially the general pediatrician’s office. I recommend that, for those physicians’ who may be uncomfortable, that they should start with the “easier” options of oral progestins (Ella or Plan B step 1). As you become more comfortable with the information and counseling, you can learn skills such as IUD insertions, so you then can offer more options.

As health care providers to children, we always are learning. And with new knowledge we sometimes can be taken out of our comfort zone. One of those areas are teenagers, contraception, safe-sex counseling, and now emergency contraception (EC). In residency you have your 1-month adolescent medicine rotation to try and absorb every bit of information like a sponge, but there also will be a level of discomfort and uncertainty. However, as medical providers we cannot let the above prevent us from giving well-rounded and informed care.

When our teens disclose the most private moment of their life, we have to be armed and ready to not only comfort them, but advise and guide them to making a decision so that they can ensure their safety. The answers regarding sexual activity are becoming more and more alarming, especially in our younger patients. Therefore, this is an important discussion to have at every visit (not just well-child checks), so that education opportunities are not missed and our patients feel a sense of normalcy about discussing reproductive health with their health care provider and or parents.

We all have our personal beliefs, but we cannot let that guide our decision on what care or education we give our patients. Unfortunately, I have heard many health care providers judge our patients for their promiscuity, when we need to educate them – not be their judge and jury. Our teens go through different stages of growth and development, and with these stages come experimentation and risk taking. So as their health care providers, we need to be up to date on the information out there.

With regards with EC, some of our patients think that they can get it only after having unprotected sex. However, they should know that the oral ECs can be given to them at any time, so should they be in the situation above, they have an immediate remedy. With the different options come different counseling and different instructions on administration and follow-up. In residency, we might not have learned the skill of inserting an IUD, which is another form of EC; that is why there are many resources available. These resources include hands-on workshops, videos on counseling, and your friendly neighborhood adolescent medicine physician or ob.gyn.

EC can give our patients that sense of relief, especially when they have unprotected sex. However, they also need to have a sense of responsibility for their actions because you do not want them to engage in high-risk behaviors. Just as we are responsible to provide up-to-date care, our patients must take ownership of their health and well-being. Also If they are engaging in unprotected sex, they are just as responsible; therefore, they should know everything about contraception as well as EC. They should feel comfortable talking to their partners about contraception. Health care providers should make them feel comfortable receiving EC that they can give to their female partner.

We need to become knowledgeable and comfortable prescribing EC, as well as incorporating it in our routine care. This is a policy that I strongly believe should be part of every pediatrician’s and family physician’s office, especially when there is a lack of resources. Of the different options that are available, the oral forms of EC – especially Ella or Plan B step 1 (levonorgestrel) – would be the easiest to prescribe and counsel on. I would not recommend the options where multiple pills need to be taken more than once a day, because compliance becomes a factor. Also knowing that these options are available over the counter also is helpful because our community pharmacist also can help with medication administration and counseling.

In summary, I strongly recommend the discussion of EC in the office, especially the general pediatrician’s office. I recommend that, for those physicians’ who may be uncomfortable, that they should start with the “easier” options of oral progestins (Ella or Plan B step 1). As you become more comfortable with the information and counseling, you can learn skills such as IUD insertions, so you then can offer more options.

As health care providers to children, we always are learning. And with new knowledge we sometimes can be taken out of our comfort zone. One of those areas are teenagers, contraception, safe-sex counseling, and now emergency contraception (EC). In residency you have your 1-month adolescent medicine rotation to try and absorb every bit of information like a sponge, but there also will be a level of discomfort and uncertainty. However, as medical providers we cannot let the above prevent us from giving well-rounded and informed care.

When our teens disclose the most private moment of their life, we have to be armed and ready to not only comfort them, but advise and guide them to making a decision so that they can ensure their safety. The answers regarding sexual activity are becoming more and more alarming, especially in our younger patients. Therefore, this is an important discussion to have at every visit (not just well-child checks), so that education opportunities are not missed and our patients feel a sense of normalcy about discussing reproductive health with their health care provider and or parents.

We all have our personal beliefs, but we cannot let that guide our decision on what care or education we give our patients. Unfortunately, I have heard many health care providers judge our patients for their promiscuity, when we need to educate them – not be their judge and jury. Our teens go through different stages of growth and development, and with these stages come experimentation and risk taking. So as their health care providers, we need to be up to date on the information out there.

With regards with EC, some of our patients think that they can get it only after having unprotected sex. However, they should know that the oral ECs can be given to them at any time, so should they be in the situation above, they have an immediate remedy. With the different options come different counseling and different instructions on administration and follow-up. In residency, we might not have learned the skill of inserting an IUD, which is another form of EC; that is why there are many resources available. These resources include hands-on workshops, videos on counseling, and your friendly neighborhood adolescent medicine physician or ob.gyn.

EC can give our patients that sense of relief, especially when they have unprotected sex. However, they also need to have a sense of responsibility for their actions because you do not want them to engage in high-risk behaviors. Just as we are responsible to provide up-to-date care, our patients must take ownership of their health and well-being. Also If they are engaging in unprotected sex, they are just as responsible; therefore, they should know everything about contraception as well as EC. They should feel comfortable talking to their partners about contraception. Health care providers should make them feel comfortable receiving EC that they can give to their female partner.

We need to become knowledgeable and comfortable prescribing EC, as well as incorporating it in our routine care. This is a policy that I strongly believe should be part of every pediatrician’s and family physician’s office, especially when there is a lack of resources. Of the different options that are available, the oral forms of EC – especially Ella or Plan B step 1 (levonorgestrel) – would be the easiest to prescribe and counsel on. I would not recommend the options where multiple pills need to be taken more than once a day, because compliance becomes a factor. Also knowing that these options are available over the counter also is helpful because our community pharmacist also can help with medication administration and counseling.

In summary, I strongly recommend the discussion of EC in the office, especially the general pediatrician’s office. I recommend that, for those physicians’ who may be uncomfortable, that they should start with the “easier” options of oral progestins (Ella or Plan B step 1). As you become more comfortable with the information and counseling, you can learn skills such as IUD insertions, so you then can offer more options.

OTC hormonal contraception: An important goal in the fight for reproductive justice

A new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion addresses how contraception access can be improved through over-the-counter (OTC) hormonal contraception for people of all ages—including oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although ACOG endorses OTC contraception, some health care providers may be hesitant to support the increase in accessibility for a variety of reasons. We are hopeful that we address these concerns and that all clinicians can move to support ACOG’s position.

Easing access to hormonal contraception is a first step

OCPs are the most widely used contraception among teens and women of reproductive age in the United States.1 Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated health insurance coverage for contraception, many barriers continue to exist, including obtaining a prescription. Only 13 states have made it legal to obtain hormonal contraception through a pharmacist.2 There also has been an increase in the number of telemedicine and online services that deliver contraceptives to individuals’ homes. While these efforts have helped to decrease barriers to hormonal contraception access for some patients, they only reach a small segment of the population. As clinicians, we should strive to make contraception universally accessible and affordable to everyone who desires to use it. OTC provision can bring us closer to this goal.

Addressing the misconceptions about contraception

Adverse events with hormonal contraception are rarer than one may think. There are few risks associated with hormonal contraception. Venous thromboembolus (VTE) is a serious, although rare, adverse effect (AE) of hormonal contraception. The rate of VTE with combined oral contraception is estimated at 3 to 8 events per 10,000 patient-years, and VTE is even less common with progestin-only contraception (1 to 5 per 10,000 patient-years). For both types of hormonal contraception, the risk of VTE is smaller than with pregnancy, which is 5 to 20 per 10,000 patient-years.3 There are comorbidities that increase the risk of VTE and other AEs of hormonal contraception. In the setting of OTC hormonal contraception, individuals would self-screen for contraindications in order to reduce these complications.

Patients have the aptitude to self-screen for contraindications. Studies looking at the ability of patients over the age of 18 to self-screen for contraindications to hormonal contraception have found that patients do appropriately screen themselves. In fact, they are often more conservative than a physician in avoiding hormonal contraceptive methods.4 Patients younger than age 18 rarely have contraindications to hormonal contraception, but limited studies have shown that they too are able to successfully self-screen.5 ACOG recommends self-screening tools be provided with all OTC combined hormonal contraceptive methods to aid an individual’s contraceptive choice.

Most patients continue their well person care. Some opponents to ACOG’s position also have expressed concern that people who access their contraception OTC will forego their annual exam with their provider. However, studies have shown that the majority of people will continue to make their preventative health care visits.6,7

We need to invest in preventing unplanned pregnancy

Currently, hormonal contraception is covered by health insurance under the ACA, with some caveats. Without a prescription, patients may have to pay full price for their contraception. However, one can find generic OCPs for less than $10 per pack out of pocket. Any cost can be prohibitive to many patients; thus, transition to OTC access to contraception also should ensure limiting the cost to the patient. One possible solution to mitigate costs is to require insurance companies to cover the cost of OTC hormonal contraceptives. (See action item below.)

Reduction in unplanned pregnancies improves public health and public expense, and broadening access to effective forms of contraception is imperative in reducing unplanned pregnancies. Every $1 invested in contraception access realizes $7.09 in savings.8 By making hormonal contraception widely available OTC, access could be improved dramatically—although pharmacist provision of hormonal contraception may be a necessary intermediate step. ACOG’s most recent committee opinion encourages all reproductive health care providers to be strong advocates for this improvement in access. As women’s health providers, we should work to decrease access barriers for our patients; working toward OTC contraception is a critical step in equal access to birth control methods for all of our patients.

Action items

Remember, before a pill can move to OTC access, the manufacturing (pharmaceutical) company must submit an application to the US Food and Drug Administration to obtain this status. Once submitted, the process may take 3 to 4 years to be completed. Currently, no company has submitted an OTC application and no hormonal birth control is available OTC. Find resources for OTC birth control access here: http://ocsotc.org/ and www.freethepill.org.

- Talk to your state representatives about why both OTC birth control access and direct pharmacy availability are important to increasing access and decreasing disparities in reproductive health care. Find your local and federal representatives here and check the status of OCP access in your state here.

- Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) both have introduced legislation—the Affordability is Access Act (HR 3296/S1847)—to ensure insurance coverage for OTC contraception. Call your representative and ask them to cosponsor this legislation.

- Be mindful of legislation that promotes OTC OCPs but limits access to some populations (minors) and increases cost sharing to the patient. This type of legislation can create harmful barriers to access for some of our patients

- Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2012;(60):1-25.

- Free the pill. What’s the law in your state? Ibis Reproductive Health website. http://freethepill.org/statepolicies. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, et al. Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:572e8.

- Williams R, Hensel D, Lehmann A, et al. Adolescent self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive pills [abstract]. Contraception. 2015;92:380.

- Hopkins K, Grossman D, White K, et al. Reproductive health preventive screening among clinic vs. over-the-counter oral contraceptive users. Contraception. 2012;86:376-382.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:144-151.

- Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, et al. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014;92:696-749.

A new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion addresses how contraception access can be improved through over-the-counter (OTC) hormonal contraception for people of all ages—including oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although ACOG endorses OTC contraception, some health care providers may be hesitant to support the increase in accessibility for a variety of reasons. We are hopeful that we address these concerns and that all clinicians can move to support ACOG’s position.

Easing access to hormonal contraception is a first step

OCPs are the most widely used contraception among teens and women of reproductive age in the United States.1 Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated health insurance coverage for contraception, many barriers continue to exist, including obtaining a prescription. Only 13 states have made it legal to obtain hormonal contraception through a pharmacist.2 There also has been an increase in the number of telemedicine and online services that deliver contraceptives to individuals’ homes. While these efforts have helped to decrease barriers to hormonal contraception access for some patients, they only reach a small segment of the population. As clinicians, we should strive to make contraception universally accessible and affordable to everyone who desires to use it. OTC provision can bring us closer to this goal.

Addressing the misconceptions about contraception

Adverse events with hormonal contraception are rarer than one may think. There are few risks associated with hormonal contraception. Venous thromboembolus (VTE) is a serious, although rare, adverse effect (AE) of hormonal contraception. The rate of VTE with combined oral contraception is estimated at 3 to 8 events per 10,000 patient-years, and VTE is even less common with progestin-only contraception (1 to 5 per 10,000 patient-years). For both types of hormonal contraception, the risk of VTE is smaller than with pregnancy, which is 5 to 20 per 10,000 patient-years.3 There are comorbidities that increase the risk of VTE and other AEs of hormonal contraception. In the setting of OTC hormonal contraception, individuals would self-screen for contraindications in order to reduce these complications.

Patients have the aptitude to self-screen for contraindications. Studies looking at the ability of patients over the age of 18 to self-screen for contraindications to hormonal contraception have found that patients do appropriately screen themselves. In fact, they are often more conservative than a physician in avoiding hormonal contraceptive methods.4 Patients younger than age 18 rarely have contraindications to hormonal contraception, but limited studies have shown that they too are able to successfully self-screen.5 ACOG recommends self-screening tools be provided with all OTC combined hormonal contraceptive methods to aid an individual’s contraceptive choice.

Most patients continue their well person care. Some opponents to ACOG’s position also have expressed concern that people who access their contraception OTC will forego their annual exam with their provider. However, studies have shown that the majority of people will continue to make their preventative health care visits.6,7

We need to invest in preventing unplanned pregnancy

Currently, hormonal contraception is covered by health insurance under the ACA, with some caveats. Without a prescription, patients may have to pay full price for their contraception. However, one can find generic OCPs for less than $10 per pack out of pocket. Any cost can be prohibitive to many patients; thus, transition to OTC access to contraception also should ensure limiting the cost to the patient. One possible solution to mitigate costs is to require insurance companies to cover the cost of OTC hormonal contraceptives. (See action item below.)

Reduction in unplanned pregnancies improves public health and public expense, and broadening access to effective forms of contraception is imperative in reducing unplanned pregnancies. Every $1 invested in contraception access realizes $7.09 in savings.8 By making hormonal contraception widely available OTC, access could be improved dramatically—although pharmacist provision of hormonal contraception may be a necessary intermediate step. ACOG’s most recent committee opinion encourages all reproductive health care providers to be strong advocates for this improvement in access. As women’s health providers, we should work to decrease access barriers for our patients; working toward OTC contraception is a critical step in equal access to birth control methods for all of our patients.

Action items

Remember, before a pill can move to OTC access, the manufacturing (pharmaceutical) company must submit an application to the US Food and Drug Administration to obtain this status. Once submitted, the process may take 3 to 4 years to be completed. Currently, no company has submitted an OTC application and no hormonal birth control is available OTC. Find resources for OTC birth control access here: http://ocsotc.org/ and www.freethepill.org.

- Talk to your state representatives about why both OTC birth control access and direct pharmacy availability are important to increasing access and decreasing disparities in reproductive health care. Find your local and federal representatives here and check the status of OCP access in your state here.

- Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) both have introduced legislation—the Affordability is Access Act (HR 3296/S1847)—to ensure insurance coverage for OTC contraception. Call your representative and ask them to cosponsor this legislation.

- Be mindful of legislation that promotes OTC OCPs but limits access to some populations (minors) and increases cost sharing to the patient. This type of legislation can create harmful barriers to access for some of our patients

A new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion addresses how contraception access can be improved through over-the-counter (OTC) hormonal contraception for people of all ages—including oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although ACOG endorses OTC contraception, some health care providers may be hesitant to support the increase in accessibility for a variety of reasons. We are hopeful that we address these concerns and that all clinicians can move to support ACOG’s position.

Easing access to hormonal contraception is a first step

OCPs are the most widely used contraception among teens and women of reproductive age in the United States.1 Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated health insurance coverage for contraception, many barriers continue to exist, including obtaining a prescription. Only 13 states have made it legal to obtain hormonal contraception through a pharmacist.2 There also has been an increase in the number of telemedicine and online services that deliver contraceptives to individuals’ homes. While these efforts have helped to decrease barriers to hormonal contraception access for some patients, they only reach a small segment of the population. As clinicians, we should strive to make contraception universally accessible and affordable to everyone who desires to use it. OTC provision can bring us closer to this goal.

Addressing the misconceptions about contraception

Adverse events with hormonal contraception are rarer than one may think. There are few risks associated with hormonal contraception. Venous thromboembolus (VTE) is a serious, although rare, adverse effect (AE) of hormonal contraception. The rate of VTE with combined oral contraception is estimated at 3 to 8 events per 10,000 patient-years, and VTE is even less common with progestin-only contraception (1 to 5 per 10,000 patient-years). For both types of hormonal contraception, the risk of VTE is smaller than with pregnancy, which is 5 to 20 per 10,000 patient-years.3 There are comorbidities that increase the risk of VTE and other AEs of hormonal contraception. In the setting of OTC hormonal contraception, individuals would self-screen for contraindications in order to reduce these complications.

Patients have the aptitude to self-screen for contraindications. Studies looking at the ability of patients over the age of 18 to self-screen for contraindications to hormonal contraception have found that patients do appropriately screen themselves. In fact, they are often more conservative than a physician in avoiding hormonal contraceptive methods.4 Patients younger than age 18 rarely have contraindications to hormonal contraception, but limited studies have shown that they too are able to successfully self-screen.5 ACOG recommends self-screening tools be provided with all OTC combined hormonal contraceptive methods to aid an individual’s contraceptive choice.

Most patients continue their well person care. Some opponents to ACOG’s position also have expressed concern that people who access their contraception OTC will forego their annual exam with their provider. However, studies have shown that the majority of people will continue to make their preventative health care visits.6,7

We need to invest in preventing unplanned pregnancy

Currently, hormonal contraception is covered by health insurance under the ACA, with some caveats. Without a prescription, patients may have to pay full price for their contraception. However, one can find generic OCPs for less than $10 per pack out of pocket. Any cost can be prohibitive to many patients; thus, transition to OTC access to contraception also should ensure limiting the cost to the patient. One possible solution to mitigate costs is to require insurance companies to cover the cost of OTC hormonal contraceptives. (See action item below.)

Reduction in unplanned pregnancies improves public health and public expense, and broadening access to effective forms of contraception is imperative in reducing unplanned pregnancies. Every $1 invested in contraception access realizes $7.09 in savings.8 By making hormonal contraception widely available OTC, access could be improved dramatically—although pharmacist provision of hormonal contraception may be a necessary intermediate step. ACOG’s most recent committee opinion encourages all reproductive health care providers to be strong advocates for this improvement in access. As women’s health providers, we should work to decrease access barriers for our patients; working toward OTC contraception is a critical step in equal access to birth control methods for all of our patients.

Action items

Remember, before a pill can move to OTC access, the manufacturing (pharmaceutical) company must submit an application to the US Food and Drug Administration to obtain this status. Once submitted, the process may take 3 to 4 years to be completed. Currently, no company has submitted an OTC application and no hormonal birth control is available OTC. Find resources for OTC birth control access here: http://ocsotc.org/ and www.freethepill.org.

- Talk to your state representatives about why both OTC birth control access and direct pharmacy availability are important to increasing access and decreasing disparities in reproductive health care. Find your local and federal representatives here and check the status of OCP access in your state here.

- Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) both have introduced legislation—the Affordability is Access Act (HR 3296/S1847)—to ensure insurance coverage for OTC contraception. Call your representative and ask them to cosponsor this legislation.

- Be mindful of legislation that promotes OTC OCPs but limits access to some populations (minors) and increases cost sharing to the patient. This type of legislation can create harmful barriers to access for some of our patients

- Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2012;(60):1-25.

- Free the pill. What’s the law in your state? Ibis Reproductive Health website. http://freethepill.org/statepolicies. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, et al. Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:572e8.

- Williams R, Hensel D, Lehmann A, et al. Adolescent self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive pills [abstract]. Contraception. 2015;92:380.

- Hopkins K, Grossman D, White K, et al. Reproductive health preventive screening among clinic vs. over-the-counter oral contraceptive users. Contraception. 2012;86:376-382.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:144-151.

- Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, et al. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014;92:696-749.

- Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2012;(60):1-25.

- Free the pill. What’s the law in your state? Ibis Reproductive Health website. http://freethepill.org/statepolicies. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, et al. Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:572e8.

- Williams R, Hensel D, Lehmann A, et al. Adolescent self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive pills [abstract]. Contraception. 2015;92:380.

- Hopkins K, Grossman D, White K, et al. Reproductive health preventive screening among clinic vs. over-the-counter oral contraceptive users. Contraception. 2012;86:376-382.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:144-151.

- Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, et al. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014;92:696-749.

FDA advisory committee supports birth control patch approval