User login

Justices appear split over birth control mandate case

U.S. Supreme Court justices appear divided over whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate.

During oral arguments on May 6, the court expressed differing perspectives about the administration’s authority to allow for more exemptions under the health law’s birth control mandate and whether the expansions were reasonable. Justices heard the consolidated cases – Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania and Trump v. Pennsylvania – by teleconference because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are expected to make a decision by the summer.

Associate justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who participated in the telephone conference call from a hospital where she was recovering from a gallbladder condition, said the exemptions ignored the intent of Congress to provide women with comprehensive coverage through the ACA.

“The glaring feature of what the government has done in expanding this exemption is to toss to the winds entirely Congress’s instruction that women need and shall have seamless, no-cost, comprehensive coverage,” she said during oral arguments. “This leaves the women to hunt for other government programs that might cover them, and for those who are not covered by Medicaid or one of the other government programs, they can get contraceptive coverage only from paying out of their own pocket, which is exactly what Congress didn’t want to happen.”

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr., meanwhile, indicated that a lower court opinion that had blocked the exemptions from going forward conflicts with the Supreme Court’s ruling in a related case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.

“Explain to me why the Third Circuit’s analysis of the question of substantial burden is not squarely inconsistent with our reasoning in Hobby Lobby,” Associate Justice Alito said during oral arguments. “Hobby Lobby held that, if a person sincerely believes that it is immoral to perform an act that has the effect of enabling another person to commit an immoral act, a federal court does not have the right to say that this person is wrong on the question of moral complicity. That’s precisely the situation here. Reading the Third Circuit’s discussion of the substantial burden question, I wondered whether they had read that part of the Hobby Lobby decision.”

The dispute surrounding the ACA’s birth control mandate and the extent of exemptions afforded has gone on for a decade and has led to numerous legal challenges. The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, but exempted group health plans of religious employers. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and lawsuits, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers not included in that exemption to opt out of the mandate. However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom.

The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved however, and in May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

In 2018, the Trump administration announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of “sincerely held religious beliefs.” A second rule allowed nonprofit organizations and small businesses that had nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate to opt out.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules, as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case. Little Sisters of the Poor, a religious nonprofit operating a home in Pittsburgh, intervened in the case as an aggrieved party. An appeal court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward.

During oral arguments, Solicitor General for the Department of Justice Noel J. Francisco said the exemptions are lawful because they are authorized under a provision of the ACA as well as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

“RFRA at the very least authorizes the religious exemption,” Mr. Francisco said during oral arguments.

Chief Deputy Attorney General for Pennsylvania Michael J. Fischer argued that the Trump administration’s moral and religious exemption rules rest on overly broad assertions of agency authority.

“First, the agencies twist a narrow delegation that allows the Health Resources and Services Administration to decide which preventive services insurers must cover under the Women’s Health Amendment into a grant of authority so broad it allows them to permit virtually any employer or college to opt out of providing contraceptive coverage entirely, including for reasons as amorphous as vaguely defined moral beliefs,” he said during oral arguments. “Second, the agencies claim that RFRA, a statute that limits government action, affirmatively authorizes them to permit employers to deny women their rights to contraceptive coverage even in the absence of a RFRA violation in the first place.”

U.S. Supreme Court justices appear divided over whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate.

During oral arguments on May 6, the court expressed differing perspectives about the administration’s authority to allow for more exemptions under the health law’s birth control mandate and whether the expansions were reasonable. Justices heard the consolidated cases – Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania and Trump v. Pennsylvania – by teleconference because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are expected to make a decision by the summer.

Associate justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who participated in the telephone conference call from a hospital where she was recovering from a gallbladder condition, said the exemptions ignored the intent of Congress to provide women with comprehensive coverage through the ACA.

“The glaring feature of what the government has done in expanding this exemption is to toss to the winds entirely Congress’s instruction that women need and shall have seamless, no-cost, comprehensive coverage,” she said during oral arguments. “This leaves the women to hunt for other government programs that might cover them, and for those who are not covered by Medicaid or one of the other government programs, they can get contraceptive coverage only from paying out of their own pocket, which is exactly what Congress didn’t want to happen.”

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr., meanwhile, indicated that a lower court opinion that had blocked the exemptions from going forward conflicts with the Supreme Court’s ruling in a related case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.

“Explain to me why the Third Circuit’s analysis of the question of substantial burden is not squarely inconsistent with our reasoning in Hobby Lobby,” Associate Justice Alito said during oral arguments. “Hobby Lobby held that, if a person sincerely believes that it is immoral to perform an act that has the effect of enabling another person to commit an immoral act, a federal court does not have the right to say that this person is wrong on the question of moral complicity. That’s precisely the situation here. Reading the Third Circuit’s discussion of the substantial burden question, I wondered whether they had read that part of the Hobby Lobby decision.”

The dispute surrounding the ACA’s birth control mandate and the extent of exemptions afforded has gone on for a decade and has led to numerous legal challenges. The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, but exempted group health plans of religious employers. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and lawsuits, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers not included in that exemption to opt out of the mandate. However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom.

The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved however, and in May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

In 2018, the Trump administration announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of “sincerely held religious beliefs.” A second rule allowed nonprofit organizations and small businesses that had nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate to opt out.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules, as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case. Little Sisters of the Poor, a religious nonprofit operating a home in Pittsburgh, intervened in the case as an aggrieved party. An appeal court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward.

During oral arguments, Solicitor General for the Department of Justice Noel J. Francisco said the exemptions are lawful because they are authorized under a provision of the ACA as well as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

“RFRA at the very least authorizes the religious exemption,” Mr. Francisco said during oral arguments.

Chief Deputy Attorney General for Pennsylvania Michael J. Fischer argued that the Trump administration’s moral and religious exemption rules rest on overly broad assertions of agency authority.

“First, the agencies twist a narrow delegation that allows the Health Resources and Services Administration to decide which preventive services insurers must cover under the Women’s Health Amendment into a grant of authority so broad it allows them to permit virtually any employer or college to opt out of providing contraceptive coverage entirely, including for reasons as amorphous as vaguely defined moral beliefs,” he said during oral arguments. “Second, the agencies claim that RFRA, a statute that limits government action, affirmatively authorizes them to permit employers to deny women their rights to contraceptive coverage even in the absence of a RFRA violation in the first place.”

U.S. Supreme Court justices appear divided over whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate.

During oral arguments on May 6, the court expressed differing perspectives about the administration’s authority to allow for more exemptions under the health law’s birth control mandate and whether the expansions were reasonable. Justices heard the consolidated cases – Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania and Trump v. Pennsylvania – by teleconference because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are expected to make a decision by the summer.

Associate justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who participated in the telephone conference call from a hospital where she was recovering from a gallbladder condition, said the exemptions ignored the intent of Congress to provide women with comprehensive coverage through the ACA.

“The glaring feature of what the government has done in expanding this exemption is to toss to the winds entirely Congress’s instruction that women need and shall have seamless, no-cost, comprehensive coverage,” she said during oral arguments. “This leaves the women to hunt for other government programs that might cover them, and for those who are not covered by Medicaid or one of the other government programs, they can get contraceptive coverage only from paying out of their own pocket, which is exactly what Congress didn’t want to happen.”

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr., meanwhile, indicated that a lower court opinion that had blocked the exemptions from going forward conflicts with the Supreme Court’s ruling in a related case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.

“Explain to me why the Third Circuit’s analysis of the question of substantial burden is not squarely inconsistent with our reasoning in Hobby Lobby,” Associate Justice Alito said during oral arguments. “Hobby Lobby held that, if a person sincerely believes that it is immoral to perform an act that has the effect of enabling another person to commit an immoral act, a federal court does not have the right to say that this person is wrong on the question of moral complicity. That’s precisely the situation here. Reading the Third Circuit’s discussion of the substantial burden question, I wondered whether they had read that part of the Hobby Lobby decision.”

The dispute surrounding the ACA’s birth control mandate and the extent of exemptions afforded has gone on for a decade and has led to numerous legal challenges. The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, but exempted group health plans of religious employers. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and lawsuits, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers not included in that exemption to opt out of the mandate. However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom.

The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved however, and in May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

In 2018, the Trump administration announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of “sincerely held religious beliefs.” A second rule allowed nonprofit organizations and small businesses that had nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate to opt out.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules, as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case. Little Sisters of the Poor, a religious nonprofit operating a home in Pittsburgh, intervened in the case as an aggrieved party. An appeal court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward.

During oral arguments, Solicitor General for the Department of Justice Noel J. Francisco said the exemptions are lawful because they are authorized under a provision of the ACA as well as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

“RFRA at the very least authorizes the religious exemption,” Mr. Francisco said during oral arguments.

Chief Deputy Attorney General for Pennsylvania Michael J. Fischer argued that the Trump administration’s moral and religious exemption rules rest on overly broad assertions of agency authority.

“First, the agencies twist a narrow delegation that allows the Health Resources and Services Administration to decide which preventive services insurers must cover under the Women’s Health Amendment into a grant of authority so broad it allows them to permit virtually any employer or college to opt out of providing contraceptive coverage entirely, including for reasons as amorphous as vaguely defined moral beliefs,” he said during oral arguments. “Second, the agencies claim that RFRA, a statute that limits government action, affirmatively authorizes them to permit employers to deny women their rights to contraceptive coverage even in the absence of a RFRA violation in the first place.”

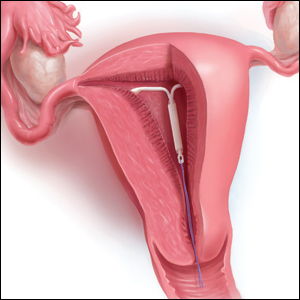

Menstrual cup use with copper IUDs linked to higher expulsion rates

Citing menstrual cup use for menstrual hygiene as “increasingly popular,” researchers led by Jill Long, MD, MPH, studied women participating in a prospective contraceptive efficacy trial of two copper IUDs to evaluate the relationship between menstrual cup use and IUD expulsion over a period of 24 months. The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

In the ongoing 3-year trial, which also was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1,092 women were randomized to one of two copper IUDs. Dr. Long, project officer for the Contraceptive Clinical Trials Network, a project of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Md. and colleagues conducted follow-up visits at 6 weeks after insertion in the first year, and then 3, 6, and 12 months after insertion. At the 9-month mark, the study counseling was amended to advise patients against concurrent use of the menstrual cup because of a higher risk of IUD expulsions noted in women using the cup.

Among the 1,092 women studied, 266 (24%) reported menstrual cup use. At 24 months after initiating enrollment, 43 cup users (17%) and 43 nonusers (5%) experienced expulsion (odds ratio, 3.81). Fourteen menstrual cup users with expulsion (30%) reported that the event occurred during menstrual cup removal. Dr. Long and colleagues found that, at year 1 of the study, expulsion rates among menstrual cup users and nonusers were 14% and 5%, respectively (P < .001). At the end of year 2, these rates rose to 23% and 7% (P < .001). The study won second place among abstracts in the category of current clinical and basic investigation.

“This outstanding abstract reflects an important study with results that should lead to changes in the way providers counsel patients about IUDs, namely that the risk of IUD expulsion is significantly higher in women who use menstrual cups than in those who use other menstrual hygiene products,” Eve Espey, MD, MPH, who was not affiliated with the study, said in an interview.

According to Dr. Espey, who chairs the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, key strengths of the study include its prospective methodology and the relatively large number of patients with concurrent IUD and menstrual cup use.

“A limitation is the nonrandomized design for the current study’s aim, which would require randomizing women using the IUD to menstrual cup use versus nonuse,” said Dr. Espey, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn News editorial advisory board.* “Another limitation is that only copper IUDs were used, but it is plausible that this result would apply to other IUDs as well. The study is innovative and important in being the first prospective study to evaluate the association between menstrual cup use and IUD expulsion.”

Dr. Long and two coauthors reported having no financial disclosures, but the remaining three authors reported having numerous potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Espey reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Long J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May;135.1S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000662872.89062.83.

*The article was updated on 4/28/2020.

Citing menstrual cup use for menstrual hygiene as “increasingly popular,” researchers led by Jill Long, MD, MPH, studied women participating in a prospective contraceptive efficacy trial of two copper IUDs to evaluate the relationship between menstrual cup use and IUD expulsion over a period of 24 months. The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

In the ongoing 3-year trial, which also was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1,092 women were randomized to one of two copper IUDs. Dr. Long, project officer for the Contraceptive Clinical Trials Network, a project of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Md. and colleagues conducted follow-up visits at 6 weeks after insertion in the first year, and then 3, 6, and 12 months after insertion. At the 9-month mark, the study counseling was amended to advise patients against concurrent use of the menstrual cup because of a higher risk of IUD expulsions noted in women using the cup.

Among the 1,092 women studied, 266 (24%) reported menstrual cup use. At 24 months after initiating enrollment, 43 cup users (17%) and 43 nonusers (5%) experienced expulsion (odds ratio, 3.81). Fourteen menstrual cup users with expulsion (30%) reported that the event occurred during menstrual cup removal. Dr. Long and colleagues found that, at year 1 of the study, expulsion rates among menstrual cup users and nonusers were 14% and 5%, respectively (P < .001). At the end of year 2, these rates rose to 23% and 7% (P < .001). The study won second place among abstracts in the category of current clinical and basic investigation.

“This outstanding abstract reflects an important study with results that should lead to changes in the way providers counsel patients about IUDs, namely that the risk of IUD expulsion is significantly higher in women who use menstrual cups than in those who use other menstrual hygiene products,” Eve Espey, MD, MPH, who was not affiliated with the study, said in an interview.

According to Dr. Espey, who chairs the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, key strengths of the study include its prospective methodology and the relatively large number of patients with concurrent IUD and menstrual cup use.

“A limitation is the nonrandomized design for the current study’s aim, which would require randomizing women using the IUD to menstrual cup use versus nonuse,” said Dr. Espey, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn News editorial advisory board.* “Another limitation is that only copper IUDs were used, but it is plausible that this result would apply to other IUDs as well. The study is innovative and important in being the first prospective study to evaluate the association between menstrual cup use and IUD expulsion.”

Dr. Long and two coauthors reported having no financial disclosures, but the remaining three authors reported having numerous potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Espey reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Long J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May;135.1S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000662872.89062.83.

*The article was updated on 4/28/2020.

Citing menstrual cup use for menstrual hygiene as “increasingly popular,” researchers led by Jill Long, MD, MPH, studied women participating in a prospective contraceptive efficacy trial of two copper IUDs to evaluate the relationship between menstrual cup use and IUD expulsion over a period of 24 months. The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

In the ongoing 3-year trial, which also was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1,092 women were randomized to one of two copper IUDs. Dr. Long, project officer for the Contraceptive Clinical Trials Network, a project of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Md. and colleagues conducted follow-up visits at 6 weeks after insertion in the first year, and then 3, 6, and 12 months after insertion. At the 9-month mark, the study counseling was amended to advise patients against concurrent use of the menstrual cup because of a higher risk of IUD expulsions noted in women using the cup.

Among the 1,092 women studied, 266 (24%) reported menstrual cup use. At 24 months after initiating enrollment, 43 cup users (17%) and 43 nonusers (5%) experienced expulsion (odds ratio, 3.81). Fourteen menstrual cup users with expulsion (30%) reported that the event occurred during menstrual cup removal. Dr. Long and colleagues found that, at year 1 of the study, expulsion rates among menstrual cup users and nonusers were 14% and 5%, respectively (P < .001). At the end of year 2, these rates rose to 23% and 7% (P < .001). The study won second place among abstracts in the category of current clinical and basic investigation.

“This outstanding abstract reflects an important study with results that should lead to changes in the way providers counsel patients about IUDs, namely that the risk of IUD expulsion is significantly higher in women who use menstrual cups than in those who use other menstrual hygiene products,” Eve Espey, MD, MPH, who was not affiliated with the study, said in an interview.

According to Dr. Espey, who chairs the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, key strengths of the study include its prospective methodology and the relatively large number of patients with concurrent IUD and menstrual cup use.

“A limitation is the nonrandomized design for the current study’s aim, which would require randomizing women using the IUD to menstrual cup use versus nonuse,” said Dr. Espey, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn News editorial advisory board.* “Another limitation is that only copper IUDs were used, but it is plausible that this result would apply to other IUDs as well. The study is innovative and important in being the first prospective study to evaluate the association between menstrual cup use and IUD expulsion.”

Dr. Long and two coauthors reported having no financial disclosures, but the remaining three authors reported having numerous potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Espey reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Long J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May;135.1S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000662872.89062.83.

*The article was updated on 4/28/2020.

FROM ACOG 2020

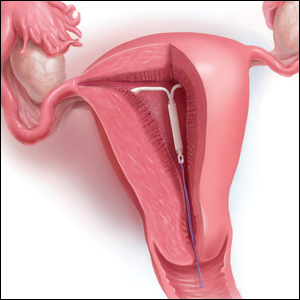

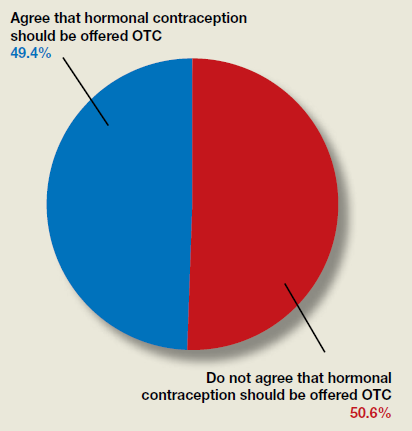

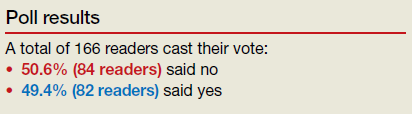

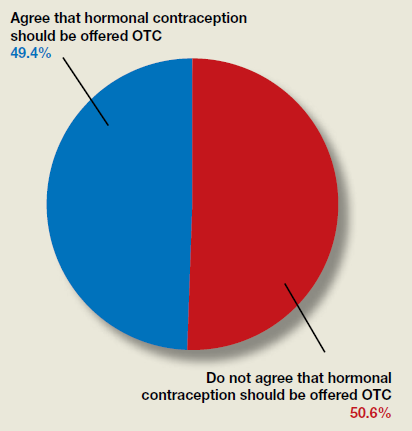

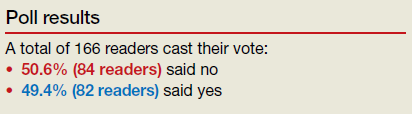

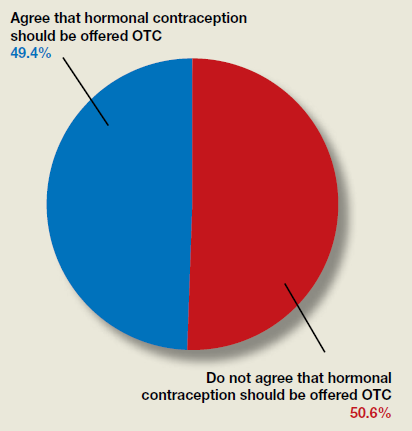

Do ObGyns think hormonal contraception should be offered over the counter?

In their advocacy column, “OTC hormonal contraception: An important goal in the fight for reproductive justice” (January 2020), Abby L. Schultz, MD, and Megan L. Evans, MD, MPH, discussed a recent committee opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) focused on improving contraception access by offering oral contraceptive pills, progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate over the counter (OTC). The authors agreed with ACOG’s stance and offered several reasons why.

OBG Management polled readers to see their thoughts on the question of whether or not hormonal contraception should be offered OTC.

In their advocacy column, “OTC hormonal contraception: An important goal in the fight for reproductive justice” (January 2020), Abby L. Schultz, MD, and Megan L. Evans, MD, MPH, discussed a recent committee opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) focused on improving contraception access by offering oral contraceptive pills, progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate over the counter (OTC). The authors agreed with ACOG’s stance and offered several reasons why.

OBG Management polled readers to see their thoughts on the question of whether or not hormonal contraception should be offered OTC.

In their advocacy column, “OTC hormonal contraception: An important goal in the fight for reproductive justice” (January 2020), Abby L. Schultz, MD, and Megan L. Evans, MD, MPH, discussed a recent committee opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) focused on improving contraception access by offering oral contraceptive pills, progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate over the counter (OTC). The authors agreed with ACOG’s stance and offered several reasons why.

OBG Management polled readers to see their thoughts on the question of whether or not hormonal contraception should be offered OTC.

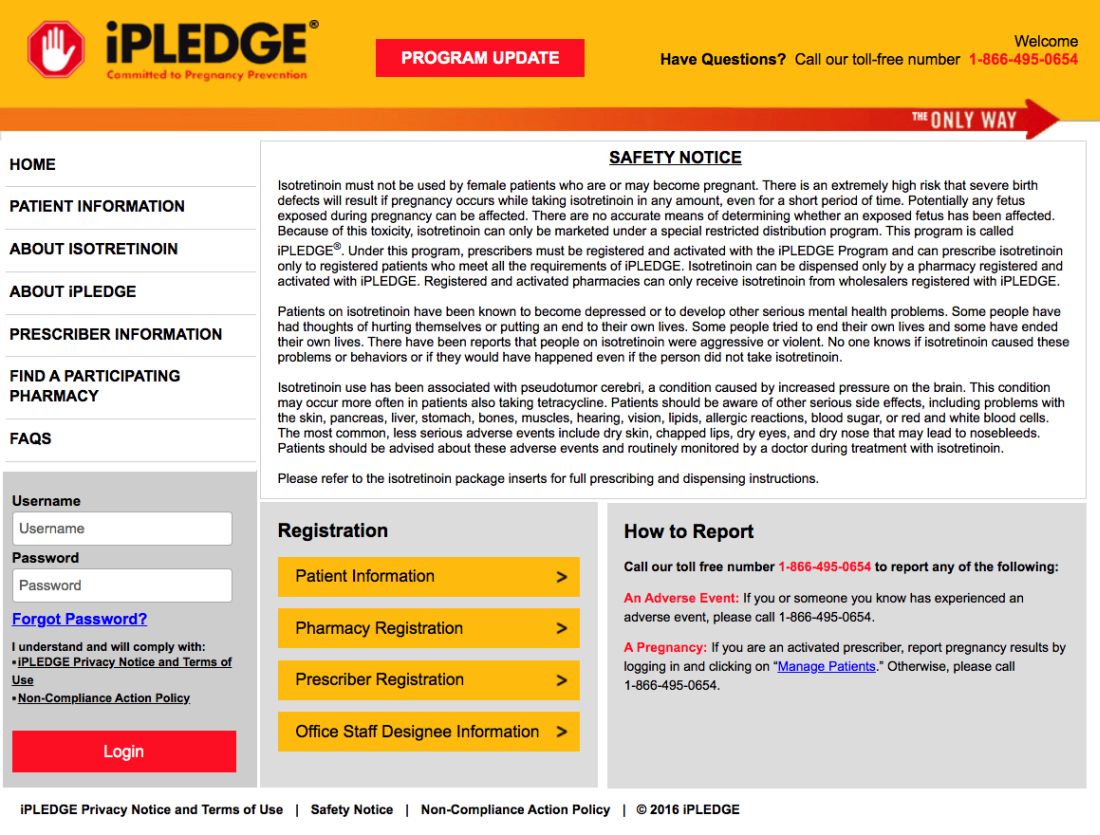

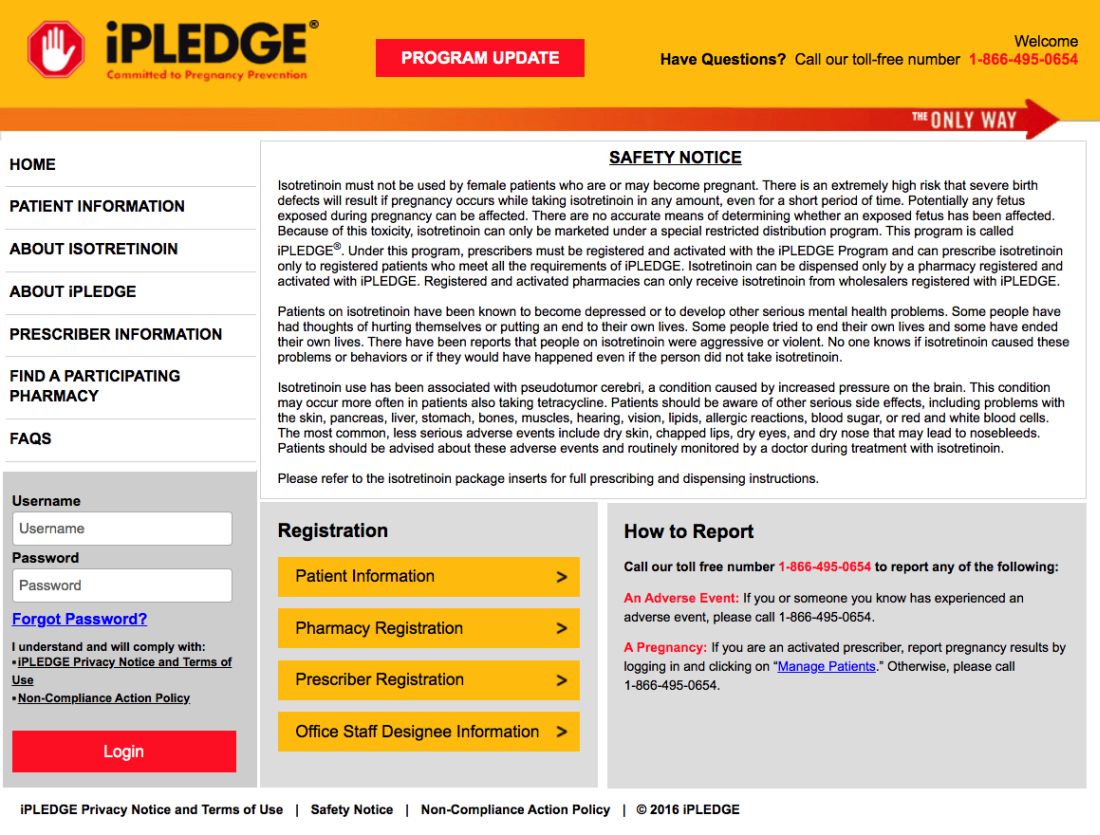

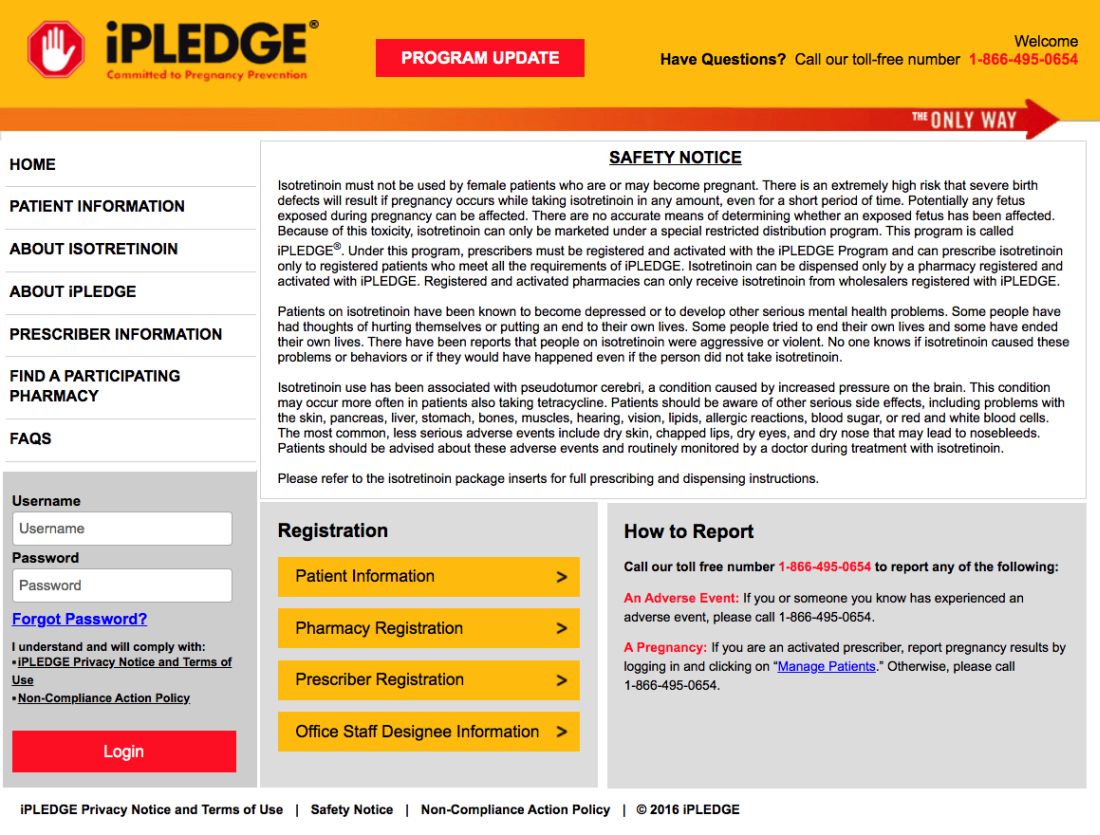

iPLEDGE allows at-home pregnancy tests during pandemic

tests to comply with the requirements of the iPLEDGE program during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an update program posted on the iPLEDGE website.

The program’s other requirements – the prescription window and two forms of birth control – remain unchanged.

The change follows recent guidance from the Department of Health & Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration regarding accommodations for medical care and drugs subject to Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) in the midst of a public health emergency that requires most people to remain in their homes except for essential services.

Allowing females to take at-home pregnancy tests and communicate the results to physician according to their preference is “a game changer for the middle of a pandemic, obviously,” Neil Goldberg, MD, a dermatologist in Westchester County, New York, said in an interview. “These are patients who don’t need to spend time outside just to get pregnancy tests done. It makes it a lot easier.”

Dr. Goldberg is frustrated, however, that the accommodations have not been more widely publicized; he discovered the change incidentally when speaking to an iPLEDGE program representative to request a waiver for a patient who had taken her pregnancy test too early. The program had denied a similar request for a 15-year-old patient of his the previous week, despite the patient being abstinent and having been in shelter-in-place for several weeks.

“The size of your notice [on the website] should be proportionate to how important it is,” Dr. Goldberg said, and the small red box on the site is easy to miss. By contrast, asking anyone to leave their homes to go to a lab for a pregnancy test in the midst of a global pandemic so they can continue their medication would be putting patients at risk, he added.

The iPLEDGE program is designed in part to ensure unplanned pregnancies do not occur in females while taking the teratogenic acne drug. But the rules are onerous and difficult even during normal times, pointed out Hilary Baldwin, MD, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York City and past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society.

Male patients taking isotretinoin must visit their physician every month to get a new no-refills prescription, but females must get a pregnancy test at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified lab, which must then provide physical results to the prescribing physician. The doctor enters the negative pregnancy test and the two forms of birth control the patient is taking in the iPLEDGE program site.

Then the patient must take an online test at home to acknowledge they understand what it means to not get pregnant and enter the two forms of birth control they are using – which must match what the doctor enters – before the pharmacy can dispense the drug. The entire process must occur within 7 days or else the patient has to wait 19 days before starting the process over.

“We run a very tight schedule for girls. And every month, we would worry that something would interfere, a snow storm or something else, and that they wouldn’t be able to complete their objectives within the 7-day period,” Dr Baldwin said in an interview. “It was always difficult, and now with us not being able to see the patient and the patient not wanting to go to the lab, this became completely impossible.”

Until this change, some patients may not have been able to get their prescription for severe nodulocystic acne, which can cause physical and psychological scarring, and “postponing treatment increases the likelihood of scarring,” Dr. Baldwin pointed out.

Dr. Goldberg’s patients now take a pregnancy test at home and send him a photo of the negative test that he then inserts into their EMR.

According to a March 17 statement from HHS, potential penalties for HIPAA violations are waived for good-faith use of “everyday communication technologies,” such as Skype or FaceTime, for telehealth treatment or diagnostics. The change was intended to allow telehealth services to continue healthcare for practices that had not previously had secure telehealth technology established.

Despite the changes for at-home pregnancy tests for females and in-person visits for all patients, the program has not altered the 7-day prescription window or the requirement to have two forms of birth control.

With reports of a global condom shortage, Dr Baldwin said she has more concerns about her adult patients being able to find a required barrier method of birth control than about her adolescent patients.

“This is a unique opportunity for us to trust our teenage patients because they can’t leave the house,” Dr. Baldwin said. “I’m actually more worried about my adult women on the drug who are bored and cooped up in a house with their significant other.”

Dr. Baldwin and Dr. Goldberg had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Goldberg is a Dermatology News board member.

tests to comply with the requirements of the iPLEDGE program during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an update program posted on the iPLEDGE website.

The program’s other requirements – the prescription window and two forms of birth control – remain unchanged.

The change follows recent guidance from the Department of Health & Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration regarding accommodations for medical care and drugs subject to Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) in the midst of a public health emergency that requires most people to remain in their homes except for essential services.

Allowing females to take at-home pregnancy tests and communicate the results to physician according to their preference is “a game changer for the middle of a pandemic, obviously,” Neil Goldberg, MD, a dermatologist in Westchester County, New York, said in an interview. “These are patients who don’t need to spend time outside just to get pregnancy tests done. It makes it a lot easier.”

Dr. Goldberg is frustrated, however, that the accommodations have not been more widely publicized; he discovered the change incidentally when speaking to an iPLEDGE program representative to request a waiver for a patient who had taken her pregnancy test too early. The program had denied a similar request for a 15-year-old patient of his the previous week, despite the patient being abstinent and having been in shelter-in-place for several weeks.

“The size of your notice [on the website] should be proportionate to how important it is,” Dr. Goldberg said, and the small red box on the site is easy to miss. By contrast, asking anyone to leave their homes to go to a lab for a pregnancy test in the midst of a global pandemic so they can continue their medication would be putting patients at risk, he added.

The iPLEDGE program is designed in part to ensure unplanned pregnancies do not occur in females while taking the teratogenic acne drug. But the rules are onerous and difficult even during normal times, pointed out Hilary Baldwin, MD, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York City and past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society.

Male patients taking isotretinoin must visit their physician every month to get a new no-refills prescription, but females must get a pregnancy test at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified lab, which must then provide physical results to the prescribing physician. The doctor enters the negative pregnancy test and the two forms of birth control the patient is taking in the iPLEDGE program site.

Then the patient must take an online test at home to acknowledge they understand what it means to not get pregnant and enter the two forms of birth control they are using – which must match what the doctor enters – before the pharmacy can dispense the drug. The entire process must occur within 7 days or else the patient has to wait 19 days before starting the process over.

“We run a very tight schedule for girls. And every month, we would worry that something would interfere, a snow storm or something else, and that they wouldn’t be able to complete their objectives within the 7-day period,” Dr Baldwin said in an interview. “It was always difficult, and now with us not being able to see the patient and the patient not wanting to go to the lab, this became completely impossible.”

Until this change, some patients may not have been able to get their prescription for severe nodulocystic acne, which can cause physical and psychological scarring, and “postponing treatment increases the likelihood of scarring,” Dr. Baldwin pointed out.

Dr. Goldberg’s patients now take a pregnancy test at home and send him a photo of the negative test that he then inserts into their EMR.

According to a March 17 statement from HHS, potential penalties for HIPAA violations are waived for good-faith use of “everyday communication technologies,” such as Skype or FaceTime, for telehealth treatment or diagnostics. The change was intended to allow telehealth services to continue healthcare for practices that had not previously had secure telehealth technology established.

Despite the changes for at-home pregnancy tests for females and in-person visits for all patients, the program has not altered the 7-day prescription window or the requirement to have two forms of birth control.

With reports of a global condom shortage, Dr Baldwin said she has more concerns about her adult patients being able to find a required barrier method of birth control than about her adolescent patients.

“This is a unique opportunity for us to trust our teenage patients because they can’t leave the house,” Dr. Baldwin said. “I’m actually more worried about my adult women on the drug who are bored and cooped up in a house with their significant other.”

Dr. Baldwin and Dr. Goldberg had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Goldberg is a Dermatology News board member.

tests to comply with the requirements of the iPLEDGE program during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an update program posted on the iPLEDGE website.

The program’s other requirements – the prescription window and two forms of birth control – remain unchanged.

The change follows recent guidance from the Department of Health & Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration regarding accommodations for medical care and drugs subject to Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) in the midst of a public health emergency that requires most people to remain in their homes except for essential services.

Allowing females to take at-home pregnancy tests and communicate the results to physician according to their preference is “a game changer for the middle of a pandemic, obviously,” Neil Goldberg, MD, a dermatologist in Westchester County, New York, said in an interview. “These are patients who don’t need to spend time outside just to get pregnancy tests done. It makes it a lot easier.”

Dr. Goldberg is frustrated, however, that the accommodations have not been more widely publicized; he discovered the change incidentally when speaking to an iPLEDGE program representative to request a waiver for a patient who had taken her pregnancy test too early. The program had denied a similar request for a 15-year-old patient of his the previous week, despite the patient being abstinent and having been in shelter-in-place for several weeks.

“The size of your notice [on the website] should be proportionate to how important it is,” Dr. Goldberg said, and the small red box on the site is easy to miss. By contrast, asking anyone to leave their homes to go to a lab for a pregnancy test in the midst of a global pandemic so they can continue their medication would be putting patients at risk, he added.

The iPLEDGE program is designed in part to ensure unplanned pregnancies do not occur in females while taking the teratogenic acne drug. But the rules are onerous and difficult even during normal times, pointed out Hilary Baldwin, MD, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York City and past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society.

Male patients taking isotretinoin must visit their physician every month to get a new no-refills prescription, but females must get a pregnancy test at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified lab, which must then provide physical results to the prescribing physician. The doctor enters the negative pregnancy test and the two forms of birth control the patient is taking in the iPLEDGE program site.

Then the patient must take an online test at home to acknowledge they understand what it means to not get pregnant and enter the two forms of birth control they are using – which must match what the doctor enters – before the pharmacy can dispense the drug. The entire process must occur within 7 days or else the patient has to wait 19 days before starting the process over.

“We run a very tight schedule for girls. And every month, we would worry that something would interfere, a snow storm or something else, and that they wouldn’t be able to complete their objectives within the 7-day period,” Dr Baldwin said in an interview. “It was always difficult, and now with us not being able to see the patient and the patient not wanting to go to the lab, this became completely impossible.”

Until this change, some patients may not have been able to get their prescription for severe nodulocystic acne, which can cause physical and psychological scarring, and “postponing treatment increases the likelihood of scarring,” Dr. Baldwin pointed out.

Dr. Goldberg’s patients now take a pregnancy test at home and send him a photo of the negative test that he then inserts into their EMR.

According to a March 17 statement from HHS, potential penalties for HIPAA violations are waived for good-faith use of “everyday communication technologies,” such as Skype or FaceTime, for telehealth treatment or diagnostics. The change was intended to allow telehealth services to continue healthcare for practices that had not previously had secure telehealth technology established.

Despite the changes for at-home pregnancy tests for females and in-person visits for all patients, the program has not altered the 7-day prescription window or the requirement to have two forms of birth control.

With reports of a global condom shortage, Dr Baldwin said she has more concerns about her adult patients being able to find a required barrier method of birth control than about her adolescent patients.

“This is a unique opportunity for us to trust our teenage patients because they can’t leave the house,” Dr. Baldwin said. “I’m actually more worried about my adult women on the drug who are bored and cooped up in a house with their significant other.”

Dr. Baldwin and Dr. Goldberg had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Goldberg is a Dermatology News board member.

High BMI does not complicate postpartum tubal ligation

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS – Higher body mass index is not associated with increased morbidity in women undergoing postpartum tubal ligation, according to a study of more than 1,000 patients.

John J. Byrne, MD, said at the Pregnancy Meeting. Dr. Byrne is affiliated with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Physicians may recommend contraception within 6 weeks of delivery, but many patients do not attend postpartum visits. “One option for women who have completed childbearing is bilateral midsegment salpingectomy via minilaparotomy,” Dr. Byrne said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “Offering this procedure immediately after delivery makes it available to women who face obstacles to follow-up care.”

The procedure entails the risk of anesthetic complications, bowel injury, and vascular injury. Subsequent pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy also may occur. Some centers will not perform the procedure if a patient’s size affects the surgeon’s ability to feel the relevant anatomy, Dr. Byrne said. “Although operative complications are presumed to be higher among obese women,” prior studies have not examined whether BMI affects rates of procedure completion, complication, or subsequent pregnancy, the researchers said.

To study this question, Dr. Byrne and colleagues examined data from women who requested postpartum sterilization following vaginal delivery at their center in 2018. The center uses the Parkland tubal ligation technique. The researchers assessed complication rates using a composite measure that included surgical complications (that is, blood transfusion, aborted procedure, or extension of incision), anesthetic complications, readmission, superficial or deep wound infection, venous thromboembolism, ileus or small bowel obstruction, incomplete transection, and subsequent pregnancy. The investigators used statistical tests to assess the relationship between BMI and morbidity.

In all, 1,014 patients underwent a postpartum tubal ligation; 17% had undergone prior abdominal surgery. The researchers classified patients’ BMI as normal (7% of the population), overweight (28%), class I obesity (38%), class II obesity (18%), or class III obesity (9%). A composite morbidity event occurred in 2%, and the proportion of patients with a complication did not significantly differ across BMI categories. No morbid events occurred in patients with normal BMI, which indicates “minimal risk” in this population, Dr. Byrne said. One incomplete transection occurred in a patient with class I obesity, and one subsequent pregnancy occurred in a patient with class II obesity. Estimated blood loss ranged from 9 mL in patients with normal BMI to 13 mL in patients with class III obesity, and length of surgery ranged from 32 minutes to 40 minutes. Neither difference is clinically significant, Dr. Byrne said.

“For the woman who desires permanent contraception, BMI should not impede her access to the procedure,” he noted.

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Byrne JJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S290, Abstract 442.

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS – Higher body mass index is not associated with increased morbidity in women undergoing postpartum tubal ligation, according to a study of more than 1,000 patients.

John J. Byrne, MD, said at the Pregnancy Meeting. Dr. Byrne is affiliated with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Physicians may recommend contraception within 6 weeks of delivery, but many patients do not attend postpartum visits. “One option for women who have completed childbearing is bilateral midsegment salpingectomy via minilaparotomy,” Dr. Byrne said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “Offering this procedure immediately after delivery makes it available to women who face obstacles to follow-up care.”

The procedure entails the risk of anesthetic complications, bowel injury, and vascular injury. Subsequent pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy also may occur. Some centers will not perform the procedure if a patient’s size affects the surgeon’s ability to feel the relevant anatomy, Dr. Byrne said. “Although operative complications are presumed to be higher among obese women,” prior studies have not examined whether BMI affects rates of procedure completion, complication, or subsequent pregnancy, the researchers said.

To study this question, Dr. Byrne and colleagues examined data from women who requested postpartum sterilization following vaginal delivery at their center in 2018. The center uses the Parkland tubal ligation technique. The researchers assessed complication rates using a composite measure that included surgical complications (that is, blood transfusion, aborted procedure, or extension of incision), anesthetic complications, readmission, superficial or deep wound infection, venous thromboembolism, ileus or small bowel obstruction, incomplete transection, and subsequent pregnancy. The investigators used statistical tests to assess the relationship between BMI and morbidity.

In all, 1,014 patients underwent a postpartum tubal ligation; 17% had undergone prior abdominal surgery. The researchers classified patients’ BMI as normal (7% of the population), overweight (28%), class I obesity (38%), class II obesity (18%), or class III obesity (9%). A composite morbidity event occurred in 2%, and the proportion of patients with a complication did not significantly differ across BMI categories. No morbid events occurred in patients with normal BMI, which indicates “minimal risk” in this population, Dr. Byrne said. One incomplete transection occurred in a patient with class I obesity, and one subsequent pregnancy occurred in a patient with class II obesity. Estimated blood loss ranged from 9 mL in patients with normal BMI to 13 mL in patients with class III obesity, and length of surgery ranged from 32 minutes to 40 minutes. Neither difference is clinically significant, Dr. Byrne said.

“For the woman who desires permanent contraception, BMI should not impede her access to the procedure,” he noted.

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Byrne JJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S290, Abstract 442.

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS – Higher body mass index is not associated with increased morbidity in women undergoing postpartum tubal ligation, according to a study of more than 1,000 patients.

John J. Byrne, MD, said at the Pregnancy Meeting. Dr. Byrne is affiliated with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Physicians may recommend contraception within 6 weeks of delivery, but many patients do not attend postpartum visits. “One option for women who have completed childbearing is bilateral midsegment salpingectomy via minilaparotomy,” Dr. Byrne said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “Offering this procedure immediately after delivery makes it available to women who face obstacles to follow-up care.”

The procedure entails the risk of anesthetic complications, bowel injury, and vascular injury. Subsequent pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy also may occur. Some centers will not perform the procedure if a patient’s size affects the surgeon’s ability to feel the relevant anatomy, Dr. Byrne said. “Although operative complications are presumed to be higher among obese women,” prior studies have not examined whether BMI affects rates of procedure completion, complication, or subsequent pregnancy, the researchers said.

To study this question, Dr. Byrne and colleagues examined data from women who requested postpartum sterilization following vaginal delivery at their center in 2018. The center uses the Parkland tubal ligation technique. The researchers assessed complication rates using a composite measure that included surgical complications (that is, blood transfusion, aborted procedure, or extension of incision), anesthetic complications, readmission, superficial or deep wound infection, venous thromboembolism, ileus or small bowel obstruction, incomplete transection, and subsequent pregnancy. The investigators used statistical tests to assess the relationship between BMI and morbidity.

In all, 1,014 patients underwent a postpartum tubal ligation; 17% had undergone prior abdominal surgery. The researchers classified patients’ BMI as normal (7% of the population), overweight (28%), class I obesity (38%), class II obesity (18%), or class III obesity (9%). A composite morbidity event occurred in 2%, and the proportion of patients with a complication did not significantly differ across BMI categories. No morbid events occurred in patients with normal BMI, which indicates “minimal risk” in this population, Dr. Byrne said. One incomplete transection occurred in a patient with class I obesity, and one subsequent pregnancy occurred in a patient with class II obesity. Estimated blood loss ranged from 9 mL in patients with normal BMI to 13 mL in patients with class III obesity, and length of surgery ranged from 32 minutes to 40 minutes. Neither difference is clinically significant, Dr. Byrne said.

“For the woman who desires permanent contraception, BMI should not impede her access to the procedure,” he noted.

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Byrne JJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S290, Abstract 442.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

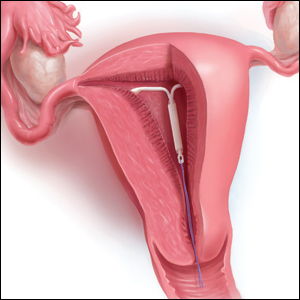

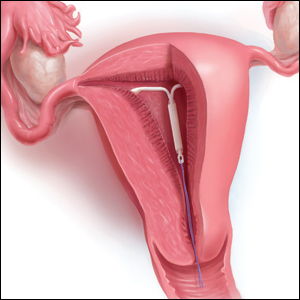

The IUD string check: Benefit or burden?

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?

Indeed, all IUD manufacturers recommend monthly self-examination to evaluate string presence.4-8 Manufacturers’ websites prominently display this information in material directed toward current or potential users, so many patients may be familiar already with this recommendation before their clinician visit. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that no routine follow-up or monitoring is needed.9

In our case scenario, follow-up is clearly burdensome and ultimately costly. Instead, clinicians can advise patients to return with rare but important to recognize complications (such as perforation, expulsion, infection), adverse effects, or desire for change. While no data are available to support in-office or at-home string checks, data do show that women reliably present when intervention is needed.

Here, we explore 5 questions relevant to IUD string checks and discuss why it is time to rethink this practice habit.

What is the purpose of a string check?

String checks serve as a surrogate for assessing an IUD’s position and function. A string check can be performed by a clinician, who observes the IUD strings on speculum exam or palpates the strings on bimanual exam, or by the patient doing a self-exam. A positive string check purportedly assures both the IUD user and the health care provider that an IUD remains in a fundal, intrauterine position, thus providing an ongoing reliable contraceptive effect.

However, string check reliability in detecting contraceptive effectiveness is uncertain. Strings that subjectively feel or appear longer than anticipated can lead to unnecessary additional evaluation and emotional distress: These are harms. By contrast, when an expulsion occurs, it often is a partial expulsion or displacement, with unclear effect on patient or physician perception of the strings on examination. One retrospective review identified women with a history of IUD placement and a positive pregnancy test; those with an intrauterine pregnancy (74%) frequently also had a malpositioned IUD (55%) and rarely identifiable string issues (16%).10 Before asking patients and clinicians to use resources for performing string evaluations, the association between this action and outcomes of interest must be elucidated.

If not for assessing risk of expulsion, IUD follow-up allows the clinician to evaluate for other complications or adverse effects and to address patient concerns. This practice often is performed when the patient is starting a new medication or medical intervention. However, a systematic review involving 4 studies of IUD follow-up visits or phone calls after contraceptive initiation generated limited data, with no notable impact on contraceptive continuation or indicated use.11

Most important, data show that patients present to their clinician when issues arise with IUD use. One prospective study of 280 women compared multiple follow-up visits with a single 6-week follow-up visit after IUD placement; 10 expulsions were identified, and 8 of these were noted at unscheduled visits when patients presented with symptoms.12 This study suggests that there is little benefit in scheduled follow-up or set self-checks.

Furthermore, in a study in Finland of more than 17,000 IUD users, the rare participants who became pregnant during IUD use promptly presented for care because of a change in menses, pain, or symptoms of pregnancy.13 While IUDs are touted as user independent, this overlooks the reality: Data show that device failure, although rare, is rapidly and appropriately addressed by the user.

Continue to: Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?...

Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?

The risk of IUD expulsion is estimated to be 1% at 1 month and 4% at 1 year, with a contraceptive failure rate of 0.4% at 1 year. The risk of expulsion does not differ by age group, including adolescents, or parity, but it is higher with use of the copper IUD (2% at 1 month, 6% at 1 year) and with prior expulsion (14%, limited by small numbers).1 Furthermore, risk of expulsion is higher with postplacental placement and second trimester abortion.14,15 Despite this risk, the contraceptive failure rate of all types of IUDs remains consistently lower than all other reversible methods besides the contraceptive implant.16

Furthermore, while IUD expulsion is rare, unnoticed expulsion is even more rare. In one study with more than 58,000 person-years of use, 132 pregnancies were noted, and 7 of these occurred in the setting of an unnoticed expulsion.13 Notably, a higher risk threshold is held for other medications. For example, statins are associated with a 3% risk of irreversible hepatic injury, yet serial liver function tests are not performed in patients without baseline liver dysfunction.17 A less than 0.1% risk of a non–life-threatening complication—unnoticed expulsion—does not warrant routine follow-up. Instead, the patient gauges the tolerability of that risk in making a follow-up plan, particularly given the varied individual preferences in patients’ management of the associated outcome of unintended pregnancy.

Are women interested in and able to perform their own string checks?

Recommendations to perform IUD string self-checks should consider whether women are willing and able to do so. In a study of 126 IUD users, 59% of women had attempted to check their IUD strings at home, and one-third were unable to do so successfully; all participants had visible strings on subsequent speculum exam.18 The women also were given the opportunity to perform a string self-check at the study visit. Overall, only 46% of participants found the exercise acceptable and were able to palpate the IUD strings.18 The authors aptly stated, “A universal recommendation for practice that is meant to identify a rare complication has no clinical utility if at least half of the women are unable to follow it.”

In which scenarios might a string check have clear utility?

The most important reason for follow-up after IUD placement or for patients to perform string self-checks is patient preference. At least anecdotally, some patients take comfort, particularly in the absence of menses, in palpating IUD strings regularly; these individuals should know that there is no necessity for but also no harm in this practice. In addition, patients may desire a string check or follow-up visit to discuss their new contraceptive’s goodness-of-fit.

While limited data show that routinely scheduling such visits does not improve contraceptive continuation, it is difficult to extrapolate these data to the select individuals who independently desire follow-up. (In addition, contraceptive continuance is hardly a metric of success, as clinicians and patients can agree that discontinuation in the setting of patient dissatisfaction is always appropriate.)

Clinicians should share with patients differing risks of IUD expulsion, and this may prompt more nuanced decisions about string checks and/or follow-up. Patients with postplacental or postabortion (second trimester) IUD placement or placement following prior expulsion may opt to perform string checks given the relatively higher risk of expulsion despite the maintained, absolutely low risk that such an event is unnoticed.

If a patient does present for a string check and strings are not visualized on exam, reasonable attempts should be made to identify the strings at that time. A cytobrush can be used to liberate and identify strings within the cervical canal. If the clinician cannot identify the strings or the patient is unable to tolerate such attempts, ultrasonography should be performed to localize the IUD. The ultrasound scan can be done in the office, if available, which is more cost-effective for women than a referral to radiology. If ultrasonography does not identify an intrauterine IUD, an x-ray is the next step to determine if the IUD has expulsed or perforated.

Continue to: Is a string check worth the cost?...

Is a string check worth the cost?

Health care providers may not be aware of the cost of care from the patient perspective. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates contraceptive coverage for women with insurance, a string check often is coded as a problem-based visit and thus may require a significant copay or out-of-pocket cost for high-deductible plans—without a proven benefit.19 Women who lack insurance coverage may forgo even necessary care due to the cost.20

The bottom line

The medical community and ObGyns specifically are familiar with a practice of patient self-examination falling by the wayside, as has been the case with breast self-examination.21 While counseling on string checks can complement conversations about risks and patients’ personal preferences regarding follow-up, no data support routine string checks in the clinic or at home. One of the great benefits of IUD use is its lack of barriers and resources for ongoing use. Physicians need not reintroduce burdens without benefits to those who desire this contraceptive method.

- Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecology Practice. Committee opinion No. 672. Clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

- Mirena website. Placement of Mirena. 2019. https://www.mirena-us.com/placement-of-mirena/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Kyleena website. Let’s get started. 2019. https://www.kyleena-us.com/lets-get-started/what-to-expect/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Skyla website. What to expect. 2019. https://www.skyla-us.com/getting-skyla/index.php. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Liletta website. What should I expect after Liletta insertion? 2020. https://www.liletta.com/about/what-to-expect-afterinsertion. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Paragard website. What to expect with Paragard. 2019. https://www.paragard.com/what-can-i-expect-with-paragard/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(4):1-66. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ volumes/65/rr/pdfs/rr6504.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Moschos E, Twickler DM. Intrauterine devices in early pregnancy: findings on ultrasound and clinical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:427.e1-6.

- Steenland MW, Zapata LB, Brahmi D, et al. Appropriate follow up to detect potential adverse events after initiation of select contraceptive methods: a systematic review. Contraception 2013;87:611-624.

- Neuteboom K, de Kroon CD, Dersjant-Roorda M, et al. Follow-up visits after IUD-insertion: sense or nonsense? Contraception. 2003;68:101-104.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Huhtala S, et al. Pregnancy during the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:50-54.

- Whitaker AK, Chen BA. Society of Family Planning guidelines: postplacental insertion of intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2018;97:2-13.

- Roe AH, Bartz D. Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion. Contraception. 2019;99:2-9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin No. 186. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. 2016. https://www .fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drugsafety-communication-important-safety-label-changescholesterol-lowering-statin-drugs. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Melo J, Tschann M, Soon R, et al. Women’s willingness and ability to feel the strings of their intrauterine device. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:309-313.

- Healthcare.gov website. Health benefits & coverage: birth control benefits. 2020. https://www.healthcare.gov/ coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- NORC at the University of Chicago. Americans’ views of healthcare costs, coverage, and policy. 2018;1-15. https:// www.norc.org/PDFs/WHI%20Healthcare%20Costs%20 Coverage%20and%20Policy/WHI%20Healthcare%20 Costs%20Coverage%20and%20Policy%20Issue%20Brief.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Kosters JP, Gotzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. CD003373.

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?

Indeed, all IUD manufacturers recommend monthly self-examination to evaluate string presence.4-8 Manufacturers’ websites prominently display this information in material directed toward current or potential users, so many patients may be familiar already with this recommendation before their clinician visit. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that no routine follow-up or monitoring is needed.9

In our case scenario, follow-up is clearly burdensome and ultimately costly. Instead, clinicians can advise patients to return with rare but important to recognize complications (such as perforation, expulsion, infection), adverse effects, or desire for change. While no data are available to support in-office or at-home string checks, data do show that women reliably present when intervention is needed.

Here, we explore 5 questions relevant to IUD string checks and discuss why it is time to rethink this practice habit.

What is the purpose of a string check?

String checks serve as a surrogate for assessing an IUD’s position and function. A string check can be performed by a clinician, who observes the IUD strings on speculum exam or palpates the strings on bimanual exam, or by the patient doing a self-exam. A positive string check purportedly assures both the IUD user and the health care provider that an IUD remains in a fundal, intrauterine position, thus providing an ongoing reliable contraceptive effect.

However, string check reliability in detecting contraceptive effectiveness is uncertain. Strings that subjectively feel or appear longer than anticipated can lead to unnecessary additional evaluation and emotional distress: These are harms. By contrast, when an expulsion occurs, it often is a partial expulsion or displacement, with unclear effect on patient or physician perception of the strings on examination. One retrospective review identified women with a history of IUD placement and a positive pregnancy test; those with an intrauterine pregnancy (74%) frequently also had a malpositioned IUD (55%) and rarely identifiable string issues (16%).10 Before asking patients and clinicians to use resources for performing string evaluations, the association between this action and outcomes of interest must be elucidated.

If not for assessing risk of expulsion, IUD follow-up allows the clinician to evaluate for other complications or adverse effects and to address patient concerns. This practice often is performed when the patient is starting a new medication or medical intervention. However, a systematic review involving 4 studies of IUD follow-up visits or phone calls after contraceptive initiation generated limited data, with no notable impact on contraceptive continuation or indicated use.11

Most important, data show that patients present to their clinician when issues arise with IUD use. One prospective study of 280 women compared multiple follow-up visits with a single 6-week follow-up visit after IUD placement; 10 expulsions were identified, and 8 of these were noted at unscheduled visits when patients presented with symptoms.12 This study suggests that there is little benefit in scheduled follow-up or set self-checks.

Furthermore, in a study in Finland of more than 17,000 IUD users, the rare participants who became pregnant during IUD use promptly presented for care because of a change in menses, pain, or symptoms of pregnancy.13 While IUDs are touted as user independent, this overlooks the reality: Data show that device failure, although rare, is rapidly and appropriately addressed by the user.

Continue to: Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?...

Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?

The risk of IUD expulsion is estimated to be 1% at 1 month and 4% at 1 year, with a contraceptive failure rate of 0.4% at 1 year. The risk of expulsion does not differ by age group, including adolescents, or parity, but it is higher with use of the copper IUD (2% at 1 month, 6% at 1 year) and with prior expulsion (14%, limited by small numbers).1 Furthermore, risk of expulsion is higher with postplacental placement and second trimester abortion.14,15 Despite this risk, the contraceptive failure rate of all types of IUDs remains consistently lower than all other reversible methods besides the contraceptive implant.16

Furthermore, while IUD expulsion is rare, unnoticed expulsion is even more rare. In one study with more than 58,000 person-years of use, 132 pregnancies were noted, and 7 of these occurred in the setting of an unnoticed expulsion.13 Notably, a higher risk threshold is held for other medications. For example, statins are associated with a 3% risk of irreversible hepatic injury, yet serial liver function tests are not performed in patients without baseline liver dysfunction.17 A less than 0.1% risk of a non–life-threatening complication—unnoticed expulsion—does not warrant routine follow-up. Instead, the patient gauges the tolerability of that risk in making a follow-up plan, particularly given the varied individual preferences in patients’ management of the associated outcome of unintended pregnancy.

Are women interested in and able to perform their own string checks?

Recommendations to perform IUD string self-checks should consider whether women are willing and able to do so. In a study of 126 IUD users, 59% of women had attempted to check their IUD strings at home, and one-third were unable to do so successfully; all participants had visible strings on subsequent speculum exam.18 The women also were given the opportunity to perform a string self-check at the study visit. Overall, only 46% of participants found the exercise acceptable and were able to palpate the IUD strings.18 The authors aptly stated, “A universal recommendation for practice that is meant to identify a rare complication has no clinical utility if at least half of the women are unable to follow it.”

In which scenarios might a string check have clear utility?

The most important reason for follow-up after IUD placement or for patients to perform string self-checks is patient preference. At least anecdotally, some patients take comfort, particularly in the absence of menses, in palpating IUD strings regularly; these individuals should know that there is no necessity for but also no harm in this practice. In addition, patients may desire a string check or follow-up visit to discuss their new contraceptive’s goodness-of-fit.

While limited data show that routinely scheduling such visits does not improve contraceptive continuation, it is difficult to extrapolate these data to the select individuals who independently desire follow-up. (In addition, contraceptive continuance is hardly a metric of success, as clinicians and patients can agree that discontinuation in the setting of patient dissatisfaction is always appropriate.)

Clinicians should share with patients differing risks of IUD expulsion, and this may prompt more nuanced decisions about string checks and/or follow-up. Patients with postplacental or postabortion (second trimester) IUD placement or placement following prior expulsion may opt to perform string checks given the relatively higher risk of expulsion despite the maintained, absolutely low risk that such an event is unnoticed.

If a patient does present for a string check and strings are not visualized on exam, reasonable attempts should be made to identify the strings at that time. A cytobrush can be used to liberate and identify strings within the cervical canal. If the clinician cannot identify the strings or the patient is unable to tolerate such attempts, ultrasonography should be performed to localize the IUD. The ultrasound scan can be done in the office, if available, which is more cost-effective for women than a referral to radiology. If ultrasonography does not identify an intrauterine IUD, an x-ray is the next step to determine if the IUD has expulsed or perforated.

Continue to: Is a string check worth the cost?...

Is a string check worth the cost?

Health care providers may not be aware of the cost of care from the patient perspective. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates contraceptive coverage for women with insurance, a string check often is coded as a problem-based visit and thus may require a significant copay or out-of-pocket cost for high-deductible plans—without a proven benefit.19 Women who lack insurance coverage may forgo even necessary care due to the cost.20

The bottom line

The medical community and ObGyns specifically are familiar with a practice of patient self-examination falling by the wayside, as has been the case with breast self-examination.21 While counseling on string checks can complement conversations about risks and patients’ personal preferences regarding follow-up, no data support routine string checks in the clinic or at home. One of the great benefits of IUD use is its lack of barriers and resources for ongoing use. Physicians need not reintroduce burdens without benefits to those who desire this contraceptive method.

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?