User login

Healthy donor stool safe, effective for recurrent CDI

For patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), based on a small trial reported online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In all, 20 of 22 patients (91%) achieved cure with donor FMT, compared with 63% of patients who received their own markedly dysbiotic stool (P = .04), reported Colleen Kelly, MD, of The Miriam Hospital, Providence, R.I., together with her associates. “Differences in efficacy between sites suggest that some patients with lower risk for CDI recurrence may not benefit from FMT. Further research may help determine the best candidates,” the researchers wrote.

FMT corrects the dysbiosis associated with CDI and is recommended in the event of failed antibiotic therapy leading to a third episode of infection. But this advice is based mainly on case series and open-label trials, the researchers noted. Their dual-center, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study included 46 patients with at least three recurrences of CDI who had completed a course of vancomycin during their most recent episode of infection. Patients older than age 75 years or who were immunocompromised were excluded (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271).

The overall clinical cure rates reflected the literature, the researchers reported, and all nine patients who developed CDI after autologous FMT were subsequently cured by donor FMT. Indeed, donor FMT “restored normal microbial community structure, with reductions in Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia and increases in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. In contrast, microbial diversity did not improve after autologous FMT.”

Notably, however, 90% of autologous FMT patients at the center in New York achieved clinical cure, compared with 43% of patients at the center in Rhode Island. Further analyses revealed differences between patients and fecal microbiota at the two sites, the investigators said. Patients in New York typically had CDI for longer, with more recurrences and up to 148 weeks of vancomycin and other antibiotics. Thus, they might have been cured before enrollment. But “autologous FMT patients at the New York site [also] had greater abundances of Clostridia, raising the possibility of emergence of microbial community assemblages inhibitory to C. difficile via competitive niche exclusion, or possibly by emergence of nontoxigenic organisms,” the researchers wrote.

There were no serious adverse effects associated with either type of FMT, they noted.

Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

Kelly and her colleagues demonstrate that rigorous controlled trials are valuable even when we think we know the answer. Their results prompt us to ask again whether microbial manipulation has any as-yet unappreciated health benefits or risks and whether there are preferred microbiomes for specific human populations or locales.

Careful review of reported adverse events in the current trial is instructive. One participant reported a 9.1-kg weight gain (donor details were not provided), a problem previously described in a separate case report. There is great interest in understanding whether the microbiome can be manipulated to modify weight in humans, as has been clearly shown in mice. In addition, patients receiving donor stool more frequently reported chills. In my own practice, I have rarely observed transient fever after healthy donor FMT delivered orally in encapsulated form, and I hypothesize that this may be due to an immune reaction to a new microbial ecosystem. Patients considering FMT should be informed of both of these possible adverse events.

Elizabeth L. Hohmann, MD, is at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. She reported grant support and personal fees from Seres Therapeutics outside the submitted work. These comments are from an editorial accompanying the article (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-1784).

AGA Resource

The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education was created to serve as a virtual ‘home’ for AGA activities related to the gut microbiome with a mission to advance research and education on the gut microbiome with the goal of improving human health. Learn more at www.gastro.org/microbiome.

Kelly and her colleagues demonstrate that rigorous controlled trials are valuable even when we think we know the answer. Their results prompt us to ask again whether microbial manipulation has any as-yet unappreciated health benefits or risks and whether there are preferred microbiomes for specific human populations or locales.

Careful review of reported adverse events in the current trial is instructive. One participant reported a 9.1-kg weight gain (donor details were not provided), a problem previously described in a separate case report. There is great interest in understanding whether the microbiome can be manipulated to modify weight in humans, as has been clearly shown in mice. In addition, patients receiving donor stool more frequently reported chills. In my own practice, I have rarely observed transient fever after healthy donor FMT delivered orally in encapsulated form, and I hypothesize that this may be due to an immune reaction to a new microbial ecosystem. Patients considering FMT should be informed of both of these possible adverse events.

Elizabeth L. Hohmann, MD, is at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. She reported grant support and personal fees from Seres Therapeutics outside the submitted work. These comments are from an editorial accompanying the article (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-1784).

AGA Resource

The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education was created to serve as a virtual ‘home’ for AGA activities related to the gut microbiome with a mission to advance research and education on the gut microbiome with the goal of improving human health. Learn more at www.gastro.org/microbiome.

Kelly and her colleagues demonstrate that rigorous controlled trials are valuable even when we think we know the answer. Their results prompt us to ask again whether microbial manipulation has any as-yet unappreciated health benefits or risks and whether there are preferred microbiomes for specific human populations or locales.

Careful review of reported adverse events in the current trial is instructive. One participant reported a 9.1-kg weight gain (donor details were not provided), a problem previously described in a separate case report. There is great interest in understanding whether the microbiome can be manipulated to modify weight in humans, as has been clearly shown in mice. In addition, patients receiving donor stool more frequently reported chills. In my own practice, I have rarely observed transient fever after healthy donor FMT delivered orally in encapsulated form, and I hypothesize that this may be due to an immune reaction to a new microbial ecosystem. Patients considering FMT should be informed of both of these possible adverse events.

Elizabeth L. Hohmann, MD, is at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. She reported grant support and personal fees from Seres Therapeutics outside the submitted work. These comments are from an editorial accompanying the article (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-1784).

AGA Resource

The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education was created to serve as a virtual ‘home’ for AGA activities related to the gut microbiome with a mission to advance research and education on the gut microbiome with the goal of improving human health. Learn more at www.gastro.org/microbiome.

For patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), based on a small trial reported online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In all, 20 of 22 patients (91%) achieved cure with donor FMT, compared with 63% of patients who received their own markedly dysbiotic stool (P = .04), reported Colleen Kelly, MD, of The Miriam Hospital, Providence, R.I., together with her associates. “Differences in efficacy between sites suggest that some patients with lower risk for CDI recurrence may not benefit from FMT. Further research may help determine the best candidates,” the researchers wrote.

FMT corrects the dysbiosis associated with CDI and is recommended in the event of failed antibiotic therapy leading to a third episode of infection. But this advice is based mainly on case series and open-label trials, the researchers noted. Their dual-center, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study included 46 patients with at least three recurrences of CDI who had completed a course of vancomycin during their most recent episode of infection. Patients older than age 75 years or who were immunocompromised were excluded (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271).

The overall clinical cure rates reflected the literature, the researchers reported, and all nine patients who developed CDI after autologous FMT were subsequently cured by donor FMT. Indeed, donor FMT “restored normal microbial community structure, with reductions in Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia and increases in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. In contrast, microbial diversity did not improve after autologous FMT.”

Notably, however, 90% of autologous FMT patients at the center in New York achieved clinical cure, compared with 43% of patients at the center in Rhode Island. Further analyses revealed differences between patients and fecal microbiota at the two sites, the investigators said. Patients in New York typically had CDI for longer, with more recurrences and up to 148 weeks of vancomycin and other antibiotics. Thus, they might have been cured before enrollment. But “autologous FMT patients at the New York site [also] had greater abundances of Clostridia, raising the possibility of emergence of microbial community assemblages inhibitory to C. difficile via competitive niche exclusion, or possibly by emergence of nontoxigenic organisms,” the researchers wrote.

There were no serious adverse effects associated with either type of FMT, they noted.

Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

For patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), based on a small trial reported online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In all, 20 of 22 patients (91%) achieved cure with donor FMT, compared with 63% of patients who received their own markedly dysbiotic stool (P = .04), reported Colleen Kelly, MD, of The Miriam Hospital, Providence, R.I., together with her associates. “Differences in efficacy between sites suggest that some patients with lower risk for CDI recurrence may not benefit from FMT. Further research may help determine the best candidates,” the researchers wrote.

FMT corrects the dysbiosis associated with CDI and is recommended in the event of failed antibiotic therapy leading to a third episode of infection. But this advice is based mainly on case series and open-label trials, the researchers noted. Their dual-center, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study included 46 patients with at least three recurrences of CDI who had completed a course of vancomycin during their most recent episode of infection. Patients older than age 75 years or who were immunocompromised were excluded (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271).

The overall clinical cure rates reflected the literature, the researchers reported, and all nine patients who developed CDI after autologous FMT were subsequently cured by donor FMT. Indeed, donor FMT “restored normal microbial community structure, with reductions in Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia and increases in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. In contrast, microbial diversity did not improve after autologous FMT.”

Notably, however, 90% of autologous FMT patients at the center in New York achieved clinical cure, compared with 43% of patients at the center in Rhode Island. Further analyses revealed differences between patients and fecal microbiota at the two sites, the investigators said. Patients in New York typically had CDI for longer, with more recurrences and up to 148 weeks of vancomycin and other antibiotics. Thus, they might have been cured before enrollment. But “autologous FMT patients at the New York site [also] had greater abundances of Clostridia, raising the possibility of emergence of microbial community assemblages inhibitory to C. difficile via competitive niche exclusion, or possibly by emergence of nontoxigenic organisms,” the researchers wrote.

There were no serious adverse effects associated with either type of FMT, they noted.

Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).

Major finding: In all, 91% of donor FMT patients and 63% of autologous FMT patients achieved clinical cure stool (P = .04).

Data source: A prospective, double-blind, randomized trial of 46 patients with at least three episodes of CDI, who had completed a full course of vancomycin during the most recent episode.

Disclosures: Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

Oral Antibiotics for Infective Endocarditis May Be Safe in Low-Risk Patients

Background: Treating infective endocarditis with four to six weeks of intravenous antibiotics carries a high cost. There are data to support oral antibiotics for right-sided endocarditis due to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin), but experience in using oral antibiotics for infective endocarditis is limited.

Study design: Cohort study.

Setting: Large academic hospital in France.

Synopsis: The researchers included 426 patients with definitive or probable endocarditis by Duke criteria. After an initial period of treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics, 50% of the identified group was transitioned to oral antibiotics (amoxicillin alone in 50% and combinations of fluoroquinolones, rifampicin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin in the others).

The risk of death was not increased in the group treated with oral antibiotics when adjusted for the four biggest predictors of death (age >65, type 1 diabetes mellitus, disinsertion of prosthetic valve, and endocarditis due to S. aureus). Nine patients treated with IV antibiotics experienced relapsed endocarditis compared to two patients treated with oral antibiotics.

Patients selected for treatment with oral antibiotics were less likely to have severe disease, significant comorbidities, or infection with S. aureus. The length of treatment with IV antibiotics before switching to oral antibiotics varied widely.

Bottom line: It’s possible low-risk patients with infective endocarditis may be treated with oral antibiotics, but more data are needed.

Citation: Mzabi A, Kernéis S, Richaud C, Podglajen I, Fernandez-Gerlinger MP, Mainardi, JL. Switch to oral antibiotics in the treatment of infective endocarditis is not associated with increased risk of mortality in non-severely ill patients [published online ahead of print April 16, 2016]. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.003.

Background: Treating infective endocarditis with four to six weeks of intravenous antibiotics carries a high cost. There are data to support oral antibiotics for right-sided endocarditis due to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin), but experience in using oral antibiotics for infective endocarditis is limited.

Study design: Cohort study.

Setting: Large academic hospital in France.

Synopsis: The researchers included 426 patients with definitive or probable endocarditis by Duke criteria. After an initial period of treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics, 50% of the identified group was transitioned to oral antibiotics (amoxicillin alone in 50% and combinations of fluoroquinolones, rifampicin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin in the others).

The risk of death was not increased in the group treated with oral antibiotics when adjusted for the four biggest predictors of death (age >65, type 1 diabetes mellitus, disinsertion of prosthetic valve, and endocarditis due to S. aureus). Nine patients treated with IV antibiotics experienced relapsed endocarditis compared to two patients treated with oral antibiotics.

Patients selected for treatment with oral antibiotics were less likely to have severe disease, significant comorbidities, or infection with S. aureus. The length of treatment with IV antibiotics before switching to oral antibiotics varied widely.

Bottom line: It’s possible low-risk patients with infective endocarditis may be treated with oral antibiotics, but more data are needed.

Citation: Mzabi A, Kernéis S, Richaud C, Podglajen I, Fernandez-Gerlinger MP, Mainardi, JL. Switch to oral antibiotics in the treatment of infective endocarditis is not associated with increased risk of mortality in non-severely ill patients [published online ahead of print April 16, 2016]. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.003.

Background: Treating infective endocarditis with four to six weeks of intravenous antibiotics carries a high cost. There are data to support oral antibiotics for right-sided endocarditis due to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin), but experience in using oral antibiotics for infective endocarditis is limited.

Study design: Cohort study.

Setting: Large academic hospital in France.

Synopsis: The researchers included 426 patients with definitive or probable endocarditis by Duke criteria. After an initial period of treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics, 50% of the identified group was transitioned to oral antibiotics (amoxicillin alone in 50% and combinations of fluoroquinolones, rifampicin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin in the others).

The risk of death was not increased in the group treated with oral antibiotics when adjusted for the four biggest predictors of death (age >65, type 1 diabetes mellitus, disinsertion of prosthetic valve, and endocarditis due to S. aureus). Nine patients treated with IV antibiotics experienced relapsed endocarditis compared to two patients treated with oral antibiotics.

Patients selected for treatment with oral antibiotics were less likely to have severe disease, significant comorbidities, or infection with S. aureus. The length of treatment with IV antibiotics before switching to oral antibiotics varied widely.

Bottom line: It’s possible low-risk patients with infective endocarditis may be treated with oral antibiotics, but more data are needed.

Citation: Mzabi A, Kernéis S, Richaud C, Podglajen I, Fernandez-Gerlinger MP, Mainardi, JL. Switch to oral antibiotics in the treatment of infective endocarditis is not associated with increased risk of mortality in non-severely ill patients [published online ahead of print April 16, 2016]. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.003.

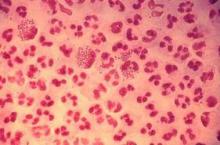

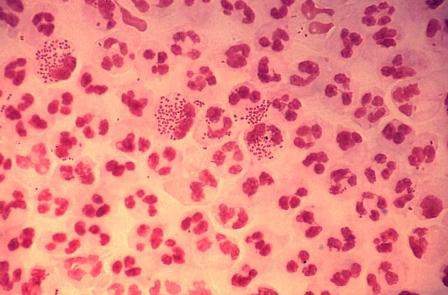

Candida auris in Venezuela outbreak is triazole-resistant, opportunistic

BOSTON – An investigation into 18 nosocomial Candida auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela showed that isolates of the emerging fungal pathogen obtained during the outbreak were resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. However, the isolates were intermediately susceptible to amphotericin B and susceptible to 5-fluorocitosine, and demonstrated high susceptibility to the candin antifungal anidulafungin.

Dr. Belinda Calvo, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Maracaibo, Venezuela, and her collaborators reported these findings, related to a 2012-2013 C. auris outbreak at the hospital. Dr. Calvo and her coinvestigators noted that other invasive C. auris outbreaks have been reported in India, Korea, and South Africa, but that “the real prevalence of this organism may be underestimated,” since common rapid microbial identification techniques may misidentify the species.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology, Dr. Calvo and her collaborators reported that the 18 patients involved in the Venezuelan outbreak were critically ill, of whom 11 were pediatric, and all had central venous catheter placement. All but two of the pediatric patients were neonates, and all had serious underlying morbidities; several had significant congenital anomalies. The median patient age was 26 days (range, 2 days to 72 years), reflecting the high number of neonates affected. One of the adult patients had esophageal carcinoma. Overall, 10/18 patients (56%) had undergone surgical procedures, and all had received antibiotics.

As has been reported in other C. auris outbreaks, isolates from blood cultures of affected individuals were initially reported as C. haemulonii by the Vitek 2 C automated microbial identification system. Molecular identification was completed by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the rDNA gene, with analysis aided by the National Institutes of Health’s GenBank and the Netherland’s CBS Fungal Diversity Centre , in order to confirm the identity of the fungal isolates as C. auris. Dr. Calvo and her associates were able to generate a dendrogram of the 18 isolates, showing high clonality, a trait shared with other nosocomial C. auris outbreaks.

Susceptibility testing of the C. auris cultured from blood samples of the affected patients showed that fluconazole had a minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit the growth of 50% of the organisms (MIC50) of greater than 64 mcg/mL. For fluconazole, the MIC90, range, and geometric mean were all also above 64 mcg/mL, indicating a high level of resistance. For voriconazole, the MICs, range, and mean were all 4 mcg/mL. For amphotericin B, the MIC50 was 1 mcg/mL, the MIC90 was 2 mcg/mL, the range was 1-2, and the geometric mean was 1.414 mcg/mL.

The high number of pediatric patients affected, as well as early pathogen identification with speedy and appropriate antifungal therapy and prompt removal of central venous catheters, likely contributed to the relatively low 30-day crude mortality rate of 28%, said Dr. Calvo and her coauthors.

“C. auris should be considered an emergent multiresistant species,” wrote Dr. Calbo and her collaborators, noting that the opportunistic pathogen has a “high potential for nosocomial horizontal transmission.”

In June 2016, the Centers for Disease Control issued a clinical alert to U.S. healthcare facilities regarding the global emergence of invasive infections caused by C. auris.

The study authors reported no external sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – An investigation into 18 nosocomial Candida auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela showed that isolates of the emerging fungal pathogen obtained during the outbreak were resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. However, the isolates were intermediately susceptible to amphotericin B and susceptible to 5-fluorocitosine, and demonstrated high susceptibility to the candin antifungal anidulafungin.

Dr. Belinda Calvo, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Maracaibo, Venezuela, and her collaborators reported these findings, related to a 2012-2013 C. auris outbreak at the hospital. Dr. Calvo and her coinvestigators noted that other invasive C. auris outbreaks have been reported in India, Korea, and South Africa, but that “the real prevalence of this organism may be underestimated,” since common rapid microbial identification techniques may misidentify the species.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology, Dr. Calvo and her collaborators reported that the 18 patients involved in the Venezuelan outbreak were critically ill, of whom 11 were pediatric, and all had central venous catheter placement. All but two of the pediatric patients were neonates, and all had serious underlying morbidities; several had significant congenital anomalies. The median patient age was 26 days (range, 2 days to 72 years), reflecting the high number of neonates affected. One of the adult patients had esophageal carcinoma. Overall, 10/18 patients (56%) had undergone surgical procedures, and all had received antibiotics.

As has been reported in other C. auris outbreaks, isolates from blood cultures of affected individuals were initially reported as C. haemulonii by the Vitek 2 C automated microbial identification system. Molecular identification was completed by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the rDNA gene, with analysis aided by the National Institutes of Health’s GenBank and the Netherland’s CBS Fungal Diversity Centre , in order to confirm the identity of the fungal isolates as C. auris. Dr. Calvo and her associates were able to generate a dendrogram of the 18 isolates, showing high clonality, a trait shared with other nosocomial C. auris outbreaks.

Susceptibility testing of the C. auris cultured from blood samples of the affected patients showed that fluconazole had a minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit the growth of 50% of the organisms (MIC50) of greater than 64 mcg/mL. For fluconazole, the MIC90, range, and geometric mean were all also above 64 mcg/mL, indicating a high level of resistance. For voriconazole, the MICs, range, and mean were all 4 mcg/mL. For amphotericin B, the MIC50 was 1 mcg/mL, the MIC90 was 2 mcg/mL, the range was 1-2, and the geometric mean was 1.414 mcg/mL.

The high number of pediatric patients affected, as well as early pathogen identification with speedy and appropriate antifungal therapy and prompt removal of central venous catheters, likely contributed to the relatively low 30-day crude mortality rate of 28%, said Dr. Calvo and her coauthors.

“C. auris should be considered an emergent multiresistant species,” wrote Dr. Calbo and her collaborators, noting that the opportunistic pathogen has a “high potential for nosocomial horizontal transmission.”

In June 2016, the Centers for Disease Control issued a clinical alert to U.S. healthcare facilities regarding the global emergence of invasive infections caused by C. auris.

The study authors reported no external sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – An investigation into 18 nosocomial Candida auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela showed that isolates of the emerging fungal pathogen obtained during the outbreak were resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. However, the isolates were intermediately susceptible to amphotericin B and susceptible to 5-fluorocitosine, and demonstrated high susceptibility to the candin antifungal anidulafungin.

Dr. Belinda Calvo, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Maracaibo, Venezuela, and her collaborators reported these findings, related to a 2012-2013 C. auris outbreak at the hospital. Dr. Calvo and her coinvestigators noted that other invasive C. auris outbreaks have been reported in India, Korea, and South Africa, but that “the real prevalence of this organism may be underestimated,” since common rapid microbial identification techniques may misidentify the species.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology, Dr. Calvo and her collaborators reported that the 18 patients involved in the Venezuelan outbreak were critically ill, of whom 11 were pediatric, and all had central venous catheter placement. All but two of the pediatric patients were neonates, and all had serious underlying morbidities; several had significant congenital anomalies. The median patient age was 26 days (range, 2 days to 72 years), reflecting the high number of neonates affected. One of the adult patients had esophageal carcinoma. Overall, 10/18 patients (56%) had undergone surgical procedures, and all had received antibiotics.

As has been reported in other C. auris outbreaks, isolates from blood cultures of affected individuals were initially reported as C. haemulonii by the Vitek 2 C automated microbial identification system. Molecular identification was completed by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the rDNA gene, with analysis aided by the National Institutes of Health’s GenBank and the Netherland’s CBS Fungal Diversity Centre , in order to confirm the identity of the fungal isolates as C. auris. Dr. Calvo and her associates were able to generate a dendrogram of the 18 isolates, showing high clonality, a trait shared with other nosocomial C. auris outbreaks.

Susceptibility testing of the C. auris cultured from blood samples of the affected patients showed that fluconazole had a minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit the growth of 50% of the organisms (MIC50) of greater than 64 mcg/mL. For fluconazole, the MIC90, range, and geometric mean were all also above 64 mcg/mL, indicating a high level of resistance. For voriconazole, the MICs, range, and mean were all 4 mcg/mL. For amphotericin B, the MIC50 was 1 mcg/mL, the MIC90 was 2 mcg/mL, the range was 1-2, and the geometric mean was 1.414 mcg/mL.

The high number of pediatric patients affected, as well as early pathogen identification with speedy and appropriate antifungal therapy and prompt removal of central venous catheters, likely contributed to the relatively low 30-day crude mortality rate of 28%, said Dr. Calvo and her coauthors.

“C. auris should be considered an emergent multiresistant species,” wrote Dr. Calbo and her collaborators, noting that the opportunistic pathogen has a “high potential for nosocomial horizontal transmission.”

In June 2016, the Centers for Disease Control issued a clinical alert to U.S. healthcare facilities regarding the global emergence of invasive infections caused by C. auris.

The study authors reported no external sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ASM 2016

Key clinical point: Isolates in an outbreak of nosocomially acquired Candida auris were fluconazole-resistant.

Major finding: All C. auris isolates were resistant to fluconazole, with geometric mean minimum inhibitory concentrations greater than 64 mcg/mL.

Data source: Retrospective, single-center study of 18 pediatric and adult patients with C. auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported no outside sources of funding and no disclosures.

Procalcitonin Guidance Safely Decreases Antibiotic Use in Critically Ill Patients

Clinical question: Can the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to discontinue antibiotic therapy safely reduce the duration of antibiotic use in critically ill patients?

Bottom line: For patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who receive antibiotics for presumed or proven bacterial infections, the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to stop antibiotic therapy results in decreased duration and consumption of antibiotics without increasing mortality.

Reference: De Jong E, Van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(7):819-827.

Design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); LOE: 1b

Setting: Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis: To test the efficacy and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy, these investigators recruited patients in the ICU who had received their first doses of antibiotics for a presumed or proven bacterial infection within 24 hours of enrollment. Patients who were severely immunosuppressed and patients requiring prolonged courses of antibiotics (such as those with endocarditis) were excluded.

Using concealed allocation, patients were assigned to procalcitonin-guided treatment (n = 761) or to usual care (n = 785). The usual care group did not have procalcitonin levels drawn. In the procalcitonin group, patients had a procalcitonin level drawn close to the start of antibiotic therapy and daily thereafter until discharge from the ICU or 3 days after stopping antibiotic use. These levels were provided to the attending physician who could then decide whether to stop giving antibiotics.

Although the study protocol recommended that antibiotics be discontinued if the procalcitonin level had decreased by more than 80% of its peak value or reached a level of 0.5 mcg/L, the ultimate decision to do so was at the discretion of the attending physician. Overall, fewer than half the physicians actually discontinued antibiotics within 24 hours of reaching either of these goals. Despite this, the procalcitonin group had decreased number of days of antibiotic treatment (5 days vs 7 days; between group absolute difference = 1.22; 95% CI 0.65-1.78; P < .0001) and decreased consumption of antibiotics (7.5 daily defined doses vs 9.3 daily defined doses; between group absolute difference = 2.69; 1.26-4.12; P < .0001). Additionally, when examining 28-day mortality rates, the procalcitonin group was noninferior to the standard group, and ultimately, had fewer deaths than the standard group (20% vs 25%; between group absolute difference = 5.4%;1.2-9.5; P = .012). This mortality benefit persisted at 1 year.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Can the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to discontinue antibiotic therapy safely reduce the duration of antibiotic use in critically ill patients?

Bottom line: For patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who receive antibiotics for presumed or proven bacterial infections, the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to stop antibiotic therapy results in decreased duration and consumption of antibiotics without increasing mortality.

Reference: De Jong E, Van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(7):819-827.

Design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); LOE: 1b

Setting: Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis: To test the efficacy and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy, these investigators recruited patients in the ICU who had received their first doses of antibiotics for a presumed or proven bacterial infection within 24 hours of enrollment. Patients who were severely immunosuppressed and patients requiring prolonged courses of antibiotics (such as those with endocarditis) were excluded.

Using concealed allocation, patients were assigned to procalcitonin-guided treatment (n = 761) or to usual care (n = 785). The usual care group did not have procalcitonin levels drawn. In the procalcitonin group, patients had a procalcitonin level drawn close to the start of antibiotic therapy and daily thereafter until discharge from the ICU or 3 days after stopping antibiotic use. These levels were provided to the attending physician who could then decide whether to stop giving antibiotics.

Although the study protocol recommended that antibiotics be discontinued if the procalcitonin level had decreased by more than 80% of its peak value or reached a level of 0.5 mcg/L, the ultimate decision to do so was at the discretion of the attending physician. Overall, fewer than half the physicians actually discontinued antibiotics within 24 hours of reaching either of these goals. Despite this, the procalcitonin group had decreased number of days of antibiotic treatment (5 days vs 7 days; between group absolute difference = 1.22; 95% CI 0.65-1.78; P < .0001) and decreased consumption of antibiotics (7.5 daily defined doses vs 9.3 daily defined doses; between group absolute difference = 2.69; 1.26-4.12; P < .0001). Additionally, when examining 28-day mortality rates, the procalcitonin group was noninferior to the standard group, and ultimately, had fewer deaths than the standard group (20% vs 25%; between group absolute difference = 5.4%;1.2-9.5; P = .012). This mortality benefit persisted at 1 year.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Can the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to discontinue antibiotic therapy safely reduce the duration of antibiotic use in critically ill patients?

Bottom line: For patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who receive antibiotics for presumed or proven bacterial infections, the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to stop antibiotic therapy results in decreased duration and consumption of antibiotics without increasing mortality.

Reference: De Jong E, Van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(7):819-827.

Design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); LOE: 1b

Setting: Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis: To test the efficacy and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy, these investigators recruited patients in the ICU who had received their first doses of antibiotics for a presumed or proven bacterial infection within 24 hours of enrollment. Patients who were severely immunosuppressed and patients requiring prolonged courses of antibiotics (such as those with endocarditis) were excluded.

Using concealed allocation, patients were assigned to procalcitonin-guided treatment (n = 761) or to usual care (n = 785). The usual care group did not have procalcitonin levels drawn. In the procalcitonin group, patients had a procalcitonin level drawn close to the start of antibiotic therapy and daily thereafter until discharge from the ICU or 3 days after stopping antibiotic use. These levels were provided to the attending physician who could then decide whether to stop giving antibiotics.

Although the study protocol recommended that antibiotics be discontinued if the procalcitonin level had decreased by more than 80% of its peak value or reached a level of 0.5 mcg/L, the ultimate decision to do so was at the discretion of the attending physician. Overall, fewer than half the physicians actually discontinued antibiotics within 24 hours of reaching either of these goals. Despite this, the procalcitonin group had decreased number of days of antibiotic treatment (5 days vs 7 days; between group absolute difference = 1.22; 95% CI 0.65-1.78; P < .0001) and decreased consumption of antibiotics (7.5 daily defined doses vs 9.3 daily defined doses; between group absolute difference = 2.69; 1.26-4.12; P < .0001). Additionally, when examining 28-day mortality rates, the procalcitonin group was noninferior to the standard group, and ultimately, had fewer deaths than the standard group (20% vs 25%; between group absolute difference = 5.4%;1.2-9.5; P = .012). This mortality benefit persisted at 1 year.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Colistin Resistance Reinforces Antibiotic Stewardship Efforts

In 2015, researchers in China announced they had found for the first time a bacterial gene conferring resistance to colistin. The gene was present in samples from agricultural animals and in 1% of tested patients.1 Colistin, an antibiotic from the 1950s, is rarely prescribed; it is often considered an antibiotic of last resort.

In May 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense announced this gene, called mcr-1, had been found in E. coli isolated from the urine of a patient in Pennsylvania presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.2 Subsequent surveillance also found mcr-1 E. coli in a pig.

The news has been met with grave concern by public health officials, scientists, infectious disease specialists, and countless physicians around the U.S. It has also served as a reminder that good antibiotic stewardship is a national, if not international, imperative.

“The recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria,” the authors of the recent U.S. study, from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, wrote in their opening sentence.

In November 2015, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) launched an antibiotic stewardship campaign, “Fight the Resistance,” in partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hospitalists around the country have taken the lead on confronting the issue head on.

When the CDC and the White House called for action last year, “SHM jumped in with both feet,” says Eric Howell, MD, MHM, SHM’s senior physician advisor, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. The “Fight the Resistance” campaign calls for the nation’s 44,000 hospitalists to commit to responsible antibiotic-prescribing practices.

“While it’s extremely alarming, leading up to this, we knew there was a crisis of antibiotic resistance,” says Megan Mack, MD, a hospitalist and clinical instructor in the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know more antibiotic use is not the answer, stronger is not the answer. We need to be peeling back antibiotic use, honing when we need them, narrowing how we use them as much as possible, and keeping the duration as short as possible.”

Dr. Mack is first author of a new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that examines hospitalist-driven antibiotic stewardship efforts in five hospitals around the country.3

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, with the CDC, recruited Dr. Mack and her study coauthors, hospitalists Jeff Rohde, MD, and Scott Flanders, MD, MHM, to participate.

“We were interested in the opportunity to put into place interventions in five different hospitals and to be able to share our successes and our barriers, which we did twice monthly,” Dr. Mack says.

Each hospital in the collaborative, which included teaching and non-teaching community hospitals and academic medical centers, focused on its own data and tailored its stewardship interventions to three strategies shown to be quality indicators of successful stewardship programs.

These strategies included:

- Enhanced documentation with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and use

- Improved quality and accessibility of guidelines for common infections

- Adoption of a 72-hour antibiotic timeout to reassess a patient’s antibiotic treatment plan once culture results were available

Each hospital used its own particular antibiotic stewardship practice data to educate and inform its physicians, which Dr. Mack says was important to the success of interventions because it was “concrete and realistic.”

The study found that in two hospitals, complete antibiotic documentation in patient records increased to 51% from 4% and to 65% from 8%. It also recorded 726 antibiotic timeouts, resulting in 218 antibiotic treatment adjustments or discontinuations. It also found several barriers to improved antibiotic stewardship.

“[Hospitalists] are stretched for time. We’re constantly being pulled in multiple directions,” Dr. Mack says. “We are bombarded daily with quality improvement initiatives and with constantly meeting metrics deemed to be priorities, so we tried interventions that were easily incorporated into daily workflow.”

The team learned that workflow integration was a requirement for success. For instance, Dr. Mack suggests building antibiotic prescribing into hospitalists’ electronic health records, with automatic stop dates that must be overridden by a physician. “It’s too easy to overlook it, and 10 days later, your patient is still on vancomycin.”

The experience, she says, made her fellow physicians in the collaborative realize that, despite some skepticism, good antimicrobial stewardship can be achieved without significant disruption.

“If we don’t change our practice patterns, there are not enough antibiotics in the pipeline to mitigate the effects,” of resistance, says Dr. Howell, who was not involved in the study. “We can’t stop resistance, but we can change our practice patterns so we slow the rate of resistance and give ourselves time to develop new therapies to treat infections.”

This includes behavioral changes hospitalists can easily incorporate, Dr. Howell says, which align with the strategies assessed in Dr. Mack’s study. These include rethinking the treatment time course, antibiotic timeouts, and adhering to prescribing guidelines.

Hospitalists, he says, are well-positioned to lead antibiotic stewardship efforts.

“We’re quality improvement experts … and there are not enough infectious disease physicians in the country to roll out antibiotic stewardship programs, so there is space for hospitalists,” Dr. Howell explains. “In every hospital, we are prescribing these medications, so we own the problem.” TH

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161-168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7.

- McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: First report of mcr-1 in the USA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

- Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative [published online ahead of print on April 30, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2599.

In 2015, researchers in China announced they had found for the first time a bacterial gene conferring resistance to colistin. The gene was present in samples from agricultural animals and in 1% of tested patients.1 Colistin, an antibiotic from the 1950s, is rarely prescribed; it is often considered an antibiotic of last resort.

In May 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense announced this gene, called mcr-1, had been found in E. coli isolated from the urine of a patient in Pennsylvania presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.2 Subsequent surveillance also found mcr-1 E. coli in a pig.

The news has been met with grave concern by public health officials, scientists, infectious disease specialists, and countless physicians around the U.S. It has also served as a reminder that good antibiotic stewardship is a national, if not international, imperative.

“The recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria,” the authors of the recent U.S. study, from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, wrote in their opening sentence.

In November 2015, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) launched an antibiotic stewardship campaign, “Fight the Resistance,” in partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hospitalists around the country have taken the lead on confronting the issue head on.

When the CDC and the White House called for action last year, “SHM jumped in with both feet,” says Eric Howell, MD, MHM, SHM’s senior physician advisor, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. The “Fight the Resistance” campaign calls for the nation’s 44,000 hospitalists to commit to responsible antibiotic-prescribing practices.

“While it’s extremely alarming, leading up to this, we knew there was a crisis of antibiotic resistance,” says Megan Mack, MD, a hospitalist and clinical instructor in the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know more antibiotic use is not the answer, stronger is not the answer. We need to be peeling back antibiotic use, honing when we need them, narrowing how we use them as much as possible, and keeping the duration as short as possible.”

Dr. Mack is first author of a new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that examines hospitalist-driven antibiotic stewardship efforts in five hospitals around the country.3

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, with the CDC, recruited Dr. Mack and her study coauthors, hospitalists Jeff Rohde, MD, and Scott Flanders, MD, MHM, to participate.

“We were interested in the opportunity to put into place interventions in five different hospitals and to be able to share our successes and our barriers, which we did twice monthly,” Dr. Mack says.

Each hospital in the collaborative, which included teaching and non-teaching community hospitals and academic medical centers, focused on its own data and tailored its stewardship interventions to three strategies shown to be quality indicators of successful stewardship programs.

These strategies included:

- Enhanced documentation with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and use

- Improved quality and accessibility of guidelines for common infections

- Adoption of a 72-hour antibiotic timeout to reassess a patient’s antibiotic treatment plan once culture results were available

Each hospital used its own particular antibiotic stewardship practice data to educate and inform its physicians, which Dr. Mack says was important to the success of interventions because it was “concrete and realistic.”

The study found that in two hospitals, complete antibiotic documentation in patient records increased to 51% from 4% and to 65% from 8%. It also recorded 726 antibiotic timeouts, resulting in 218 antibiotic treatment adjustments or discontinuations. It also found several barriers to improved antibiotic stewardship.

“[Hospitalists] are stretched for time. We’re constantly being pulled in multiple directions,” Dr. Mack says. “We are bombarded daily with quality improvement initiatives and with constantly meeting metrics deemed to be priorities, so we tried interventions that were easily incorporated into daily workflow.”

The team learned that workflow integration was a requirement for success. For instance, Dr. Mack suggests building antibiotic prescribing into hospitalists’ electronic health records, with automatic stop dates that must be overridden by a physician. “It’s too easy to overlook it, and 10 days later, your patient is still on vancomycin.”

The experience, she says, made her fellow physicians in the collaborative realize that, despite some skepticism, good antimicrobial stewardship can be achieved without significant disruption.

“If we don’t change our practice patterns, there are not enough antibiotics in the pipeline to mitigate the effects,” of resistance, says Dr. Howell, who was not involved in the study. “We can’t stop resistance, but we can change our practice patterns so we slow the rate of resistance and give ourselves time to develop new therapies to treat infections.”

This includes behavioral changes hospitalists can easily incorporate, Dr. Howell says, which align with the strategies assessed in Dr. Mack’s study. These include rethinking the treatment time course, antibiotic timeouts, and adhering to prescribing guidelines.

Hospitalists, he says, are well-positioned to lead antibiotic stewardship efforts.

“We’re quality improvement experts … and there are not enough infectious disease physicians in the country to roll out antibiotic stewardship programs, so there is space for hospitalists,” Dr. Howell explains. “In every hospital, we are prescribing these medications, so we own the problem.” TH

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161-168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7.

- McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: First report of mcr-1 in the USA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

- Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative [published online ahead of print on April 30, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2599.

In 2015, researchers in China announced they had found for the first time a bacterial gene conferring resistance to colistin. The gene was present in samples from agricultural animals and in 1% of tested patients.1 Colistin, an antibiotic from the 1950s, is rarely prescribed; it is often considered an antibiotic of last resort.

In May 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense announced this gene, called mcr-1, had been found in E. coli isolated from the urine of a patient in Pennsylvania presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.2 Subsequent surveillance also found mcr-1 E. coli in a pig.

The news has been met with grave concern by public health officials, scientists, infectious disease specialists, and countless physicians around the U.S. It has also served as a reminder that good antibiotic stewardship is a national, if not international, imperative.

“The recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria,” the authors of the recent U.S. study, from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, wrote in their opening sentence.

In November 2015, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) launched an antibiotic stewardship campaign, “Fight the Resistance,” in partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hospitalists around the country have taken the lead on confronting the issue head on.

When the CDC and the White House called for action last year, “SHM jumped in with both feet,” says Eric Howell, MD, MHM, SHM’s senior physician advisor, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. The “Fight the Resistance” campaign calls for the nation’s 44,000 hospitalists to commit to responsible antibiotic-prescribing practices.

“While it’s extremely alarming, leading up to this, we knew there was a crisis of antibiotic resistance,” says Megan Mack, MD, a hospitalist and clinical instructor in the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know more antibiotic use is not the answer, stronger is not the answer. We need to be peeling back antibiotic use, honing when we need them, narrowing how we use them as much as possible, and keeping the duration as short as possible.”

Dr. Mack is first author of a new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that examines hospitalist-driven antibiotic stewardship efforts in five hospitals around the country.3

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, with the CDC, recruited Dr. Mack and her study coauthors, hospitalists Jeff Rohde, MD, and Scott Flanders, MD, MHM, to participate.

“We were interested in the opportunity to put into place interventions in five different hospitals and to be able to share our successes and our barriers, which we did twice monthly,” Dr. Mack says.

Each hospital in the collaborative, which included teaching and non-teaching community hospitals and academic medical centers, focused on its own data and tailored its stewardship interventions to three strategies shown to be quality indicators of successful stewardship programs.

These strategies included:

- Enhanced documentation with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and use

- Improved quality and accessibility of guidelines for common infections

- Adoption of a 72-hour antibiotic timeout to reassess a patient’s antibiotic treatment plan once culture results were available

Each hospital used its own particular antibiotic stewardship practice data to educate and inform its physicians, which Dr. Mack says was important to the success of interventions because it was “concrete and realistic.”

The study found that in two hospitals, complete antibiotic documentation in patient records increased to 51% from 4% and to 65% from 8%. It also recorded 726 antibiotic timeouts, resulting in 218 antibiotic treatment adjustments or discontinuations. It also found several barriers to improved antibiotic stewardship.

“[Hospitalists] are stretched for time. We’re constantly being pulled in multiple directions,” Dr. Mack says. “We are bombarded daily with quality improvement initiatives and with constantly meeting metrics deemed to be priorities, so we tried interventions that were easily incorporated into daily workflow.”

The team learned that workflow integration was a requirement for success. For instance, Dr. Mack suggests building antibiotic prescribing into hospitalists’ electronic health records, with automatic stop dates that must be overridden by a physician. “It’s too easy to overlook it, and 10 days later, your patient is still on vancomycin.”

The experience, she says, made her fellow physicians in the collaborative realize that, despite some skepticism, good antimicrobial stewardship can be achieved without significant disruption.

“If we don’t change our practice patterns, there are not enough antibiotics in the pipeline to mitigate the effects,” of resistance, says Dr. Howell, who was not involved in the study. “We can’t stop resistance, but we can change our practice patterns so we slow the rate of resistance and give ourselves time to develop new therapies to treat infections.”

This includes behavioral changes hospitalists can easily incorporate, Dr. Howell says, which align with the strategies assessed in Dr. Mack’s study. These include rethinking the treatment time course, antibiotic timeouts, and adhering to prescribing guidelines.

Hospitalists, he says, are well-positioned to lead antibiotic stewardship efforts.

“We’re quality improvement experts … and there are not enough infectious disease physicians in the country to roll out antibiotic stewardship programs, so there is space for hospitalists,” Dr. Howell explains. “In every hospital, we are prescribing these medications, so we own the problem.” TH

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161-168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7.

- McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: First report of mcr-1 in the USA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

- Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative [published online ahead of print on April 30, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2599.

MCR-1 gene a growing concern for antibiotic resistance

The MCR-1 gene is quickly emerging as a powerful roadblock in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Alex J. Kallen, MD, of the CDC in Atlanta, said in an Aug. 2 webinar – cohosted by CDC and the Partnership for Quality Care – that the CDC is closely monitoring the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the United States. The prevailing message of Dr. Kallen and his CDC colleague Arjun Srinivasan, MD was that the importance of the MCR-1 gene should not be underestimated.

First discovered in a human patient last year, the presence of the MCR-1 gene makes bacteria resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used often as a last resort to “treat patients with multidrug-resistant infections,” according to the CDC. Because the MCR-1 gene exists on a plasmid, or a small piece of DNA, it is easily transferable among bacteria, making it a problem for health care providers treating a patient infected with bacteria that has the gene.

“As of this year, all state and some local health departments will be funded to respond to [antibiotic resistance] threats, including emerging threats like [MCR-1], within their jurisdiction,” Dr. Kallen said. This funding could be used to support technical assistance, contact investigations, and laboratory testing, among other things.

In order to help prevent the spread of MCR-1 and mitigate cases of novel antimicrobial resistance, health care providers and facilities should institute recommended intensive care precautions as soon as resistance is identified, along with alerting their local public health office. Isolates should be saved, and prospective and retrospective surveillance should be implemented to “identify isolates with similar phenotypes.” If an infected patient is being transferred to another facility, that facility should be notified ahead of time about the patient and what protocols to follow.

Because antibiotic-resistant organisms do not spread through the air like influenza, the risk that these organisms pose to health care workers is relatively low, Dr. Srinivasan explained. However, he stressed that a multifaceted, team-based approach to antibiotic stewardship and decontamination of health care facilities is absolutely necessary to achieve the best results for both patients and staff.

“We are now beginning to recognize that the contamination of surfaces and items in our health care environment is increasingly a problem in the transmission of these drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Srinivasan explained. He said that, given the complexity of a typical health care environment, such as a hospital room or operating theater, it’s perhaps not so surprising that keeping everything clean is not the top priority.

In addition to making sure hospital rooms and other areas are properly cleaned, simple things like washing hands and keeping surfaces clean are just as important. Dr. Srinivasan pointed to a 2006 study by Philip C. Carling, MD, and his associates which showed that educational interventions can lead to substantial increases in hygiene and cleanliness, and that training of new staff is also important. Furthermore, giving staff enough time to properly clean rooms could significantly contribute to curtailing MCR-1 bacteria from spreading, he said.

“The other thing to keep in mind is that if we lose effective therapy, if we lose antibiotic therapy, the infections that are currently very treatable and are seldom deadly could again become very, very serious threats to life,” Dr. Srinivasan warned, specifically citing Escherichia coli, which is the leading cause of urinary tract infections. If community strains of E.coli become resistant to typical antibiotic treatment, these cases could become “difficult, if not impossible to treat.”

According to data shared by Dr. Srinivasan, in 2013 there were 2,049,422 illnesses in the United States attributed to antibiotic resistance and 23,000 fatalities.

The MCR-1 gene is quickly emerging as a powerful roadblock in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Alex J. Kallen, MD, of the CDC in Atlanta, said in an Aug. 2 webinar – cohosted by CDC and the Partnership for Quality Care – that the CDC is closely monitoring the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the United States. The prevailing message of Dr. Kallen and his CDC colleague Arjun Srinivasan, MD was that the importance of the MCR-1 gene should not be underestimated.

First discovered in a human patient last year, the presence of the MCR-1 gene makes bacteria resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used often as a last resort to “treat patients with multidrug-resistant infections,” according to the CDC. Because the MCR-1 gene exists on a plasmid, or a small piece of DNA, it is easily transferable among bacteria, making it a problem for health care providers treating a patient infected with bacteria that has the gene.

“As of this year, all state and some local health departments will be funded to respond to [antibiotic resistance] threats, including emerging threats like [MCR-1], within their jurisdiction,” Dr. Kallen said. This funding could be used to support technical assistance, contact investigations, and laboratory testing, among other things.

In order to help prevent the spread of MCR-1 and mitigate cases of novel antimicrobial resistance, health care providers and facilities should institute recommended intensive care precautions as soon as resistance is identified, along with alerting their local public health office. Isolates should be saved, and prospective and retrospective surveillance should be implemented to “identify isolates with similar phenotypes.” If an infected patient is being transferred to another facility, that facility should be notified ahead of time about the patient and what protocols to follow.

Because antibiotic-resistant organisms do not spread through the air like influenza, the risk that these organisms pose to health care workers is relatively low, Dr. Srinivasan explained. However, he stressed that a multifaceted, team-based approach to antibiotic stewardship and decontamination of health care facilities is absolutely necessary to achieve the best results for both patients and staff.

“We are now beginning to recognize that the contamination of surfaces and items in our health care environment is increasingly a problem in the transmission of these drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Srinivasan explained. He said that, given the complexity of a typical health care environment, such as a hospital room or operating theater, it’s perhaps not so surprising that keeping everything clean is not the top priority.

In addition to making sure hospital rooms and other areas are properly cleaned, simple things like washing hands and keeping surfaces clean are just as important. Dr. Srinivasan pointed to a 2006 study by Philip C. Carling, MD, and his associates which showed that educational interventions can lead to substantial increases in hygiene and cleanliness, and that training of new staff is also important. Furthermore, giving staff enough time to properly clean rooms could significantly contribute to curtailing MCR-1 bacteria from spreading, he said.

“The other thing to keep in mind is that if we lose effective therapy, if we lose antibiotic therapy, the infections that are currently very treatable and are seldom deadly could again become very, very serious threats to life,” Dr. Srinivasan warned, specifically citing Escherichia coli, which is the leading cause of urinary tract infections. If community strains of E.coli become resistant to typical antibiotic treatment, these cases could become “difficult, if not impossible to treat.”

According to data shared by Dr. Srinivasan, in 2013 there were 2,049,422 illnesses in the United States attributed to antibiotic resistance and 23,000 fatalities.

The MCR-1 gene is quickly emerging as a powerful roadblock in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Alex J. Kallen, MD, of the CDC in Atlanta, said in an Aug. 2 webinar – cohosted by CDC and the Partnership for Quality Care – that the CDC is closely monitoring the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the United States. The prevailing message of Dr. Kallen and his CDC colleague Arjun Srinivasan, MD was that the importance of the MCR-1 gene should not be underestimated.

First discovered in a human patient last year, the presence of the MCR-1 gene makes bacteria resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used often as a last resort to “treat patients with multidrug-resistant infections,” according to the CDC. Because the MCR-1 gene exists on a plasmid, or a small piece of DNA, it is easily transferable among bacteria, making it a problem for health care providers treating a patient infected with bacteria that has the gene.

“As of this year, all state and some local health departments will be funded to respond to [antibiotic resistance] threats, including emerging threats like [MCR-1], within their jurisdiction,” Dr. Kallen said. This funding could be used to support technical assistance, contact investigations, and laboratory testing, among other things.

In order to help prevent the spread of MCR-1 and mitigate cases of novel antimicrobial resistance, health care providers and facilities should institute recommended intensive care precautions as soon as resistance is identified, along with alerting their local public health office. Isolates should be saved, and prospective and retrospective surveillance should be implemented to “identify isolates with similar phenotypes.” If an infected patient is being transferred to another facility, that facility should be notified ahead of time about the patient and what protocols to follow.

Because antibiotic-resistant organisms do not spread through the air like influenza, the risk that these organisms pose to health care workers is relatively low, Dr. Srinivasan explained. However, he stressed that a multifaceted, team-based approach to antibiotic stewardship and decontamination of health care facilities is absolutely necessary to achieve the best results for both patients and staff.

“We are now beginning to recognize that the contamination of surfaces and items in our health care environment is increasingly a problem in the transmission of these drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Srinivasan explained. He said that, given the complexity of a typical health care environment, such as a hospital room or operating theater, it’s perhaps not so surprising that keeping everything clean is not the top priority.

In addition to making sure hospital rooms and other areas are properly cleaned, simple things like washing hands and keeping surfaces clean are just as important. Dr. Srinivasan pointed to a 2006 study by Philip C. Carling, MD, and his associates which showed that educational interventions can lead to substantial increases in hygiene and cleanliness, and that training of new staff is also important. Furthermore, giving staff enough time to properly clean rooms could significantly contribute to curtailing MCR-1 bacteria from spreading, he said.

“The other thing to keep in mind is that if we lose effective therapy, if we lose antibiotic therapy, the infections that are currently very treatable and are seldom deadly could again become very, very serious threats to life,” Dr. Srinivasan warned, specifically citing Escherichia coli, which is the leading cause of urinary tract infections. If community strains of E.coli become resistant to typical antibiotic treatment, these cases could become “difficult, if not impossible to treat.”

According to data shared by Dr. Srinivasan, in 2013 there were 2,049,422 illnesses in the United States attributed to antibiotic resistance and 23,000 fatalities.

U.S. to jump-start antibiotic resistance research

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.