User login

Many patients with diabetic foot infections get unnecessary MRSA treatment

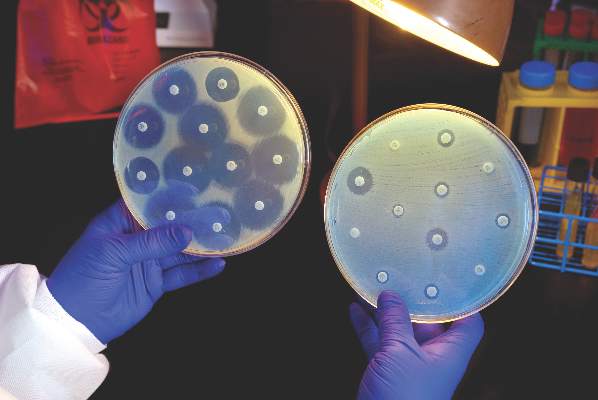

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

FROM PLOS ONE

WHO updates ranking of critically important antimicrobials

In light of increasing antibiotic resistance among pathogens, the World Health Organization has revised its global rankings of critically important antimicrobials used in human medicine, designating quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides as among the highest-priority drugs in the world.

Peter C. Collignon, MBBS, of Canberra (Australia) Hospital and his colleagues on the WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance, created the rankings for use in developing risk management strategies related to antimicrobial use in food production animals. According to Dr. Collignon and his coauthors, the rankings are intended to help regulators and other stakeholders know which types of antimicrobials used in animals present potentially higher risks to human populations and help inform how this use might be better managed (e.g. restriction to single-animal therapy or prohibition of mass treatment and extra-label use) to minimize the risk of transmission of resistance to the human population.

WHO studies previously suggested that antimicrobials which currently have no veterinary equivalent (for example, carbapenems) “as well as any new class of antimicrobial developed for human therapy should not be used in animals.” Dr. Collignon’s WHO Advisory Group followed two essential criteria to designate antimicrobials of utmost importance to human health in the new study: 1. antimicrobials that are the sole, or one of limited available therapies, to treat serious bacterial infections in people and 2. antimicrobials used to treat infections in people caused by either (a) bacteria that may be transmitted to humans from nonhuman sources or (b) bacteria that may acquire resistance genes from nonhuman sources.

The highest-priority and most critically important antimicrobials are those which meet the criteria listed above and that are used in greatest volume or highest frequency by humans. Another criteria for prioritization involves antimicrobial classes where evidence suggests that the “transmission of resistant bacteria or resistance genes from nonhuman sources is already occurring, or has occurred previously.” Quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides were the only antimicrobials that met all criteria for prioritization.

“Antimicrobial resistance remains a threat to human health and drivers of resistance act in all sectors; human, animal, and the environment,” the WHO Advisory Group concluded. “Prioritizing the antimicrobials that are critically important for humans is a valuable and strategic risk-management tool and will be improved with the evidence-based approach which is currently underway.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475).

In light of increasing antibiotic resistance among pathogens, the World Health Organization has revised its global rankings of critically important antimicrobials used in human medicine, designating quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides as among the highest-priority drugs in the world.

Peter C. Collignon, MBBS, of Canberra (Australia) Hospital and his colleagues on the WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance, created the rankings for use in developing risk management strategies related to antimicrobial use in food production animals. According to Dr. Collignon and his coauthors, the rankings are intended to help regulators and other stakeholders know which types of antimicrobials used in animals present potentially higher risks to human populations and help inform how this use might be better managed (e.g. restriction to single-animal therapy or prohibition of mass treatment and extra-label use) to minimize the risk of transmission of resistance to the human population.

WHO studies previously suggested that antimicrobials which currently have no veterinary equivalent (for example, carbapenems) “as well as any new class of antimicrobial developed for human therapy should not be used in animals.” Dr. Collignon’s WHO Advisory Group followed two essential criteria to designate antimicrobials of utmost importance to human health in the new study: 1. antimicrobials that are the sole, or one of limited available therapies, to treat serious bacterial infections in people and 2. antimicrobials used to treat infections in people caused by either (a) bacteria that may be transmitted to humans from nonhuman sources or (b) bacteria that may acquire resistance genes from nonhuman sources.

The highest-priority and most critically important antimicrobials are those which meet the criteria listed above and that are used in greatest volume or highest frequency by humans. Another criteria for prioritization involves antimicrobial classes where evidence suggests that the “transmission of resistant bacteria or resistance genes from nonhuman sources is already occurring, or has occurred previously.” Quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides were the only antimicrobials that met all criteria for prioritization.

“Antimicrobial resistance remains a threat to human health and drivers of resistance act in all sectors; human, animal, and the environment,” the WHO Advisory Group concluded. “Prioritizing the antimicrobials that are critically important for humans is a valuable and strategic risk-management tool and will be improved with the evidence-based approach which is currently underway.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475).

In light of increasing antibiotic resistance among pathogens, the World Health Organization has revised its global rankings of critically important antimicrobials used in human medicine, designating quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides as among the highest-priority drugs in the world.

Peter C. Collignon, MBBS, of Canberra (Australia) Hospital and his colleagues on the WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance, created the rankings for use in developing risk management strategies related to antimicrobial use in food production animals. According to Dr. Collignon and his coauthors, the rankings are intended to help regulators and other stakeholders know which types of antimicrobials used in animals present potentially higher risks to human populations and help inform how this use might be better managed (e.g. restriction to single-animal therapy or prohibition of mass treatment and extra-label use) to minimize the risk of transmission of resistance to the human population.

WHO studies previously suggested that antimicrobials which currently have no veterinary equivalent (for example, carbapenems) “as well as any new class of antimicrobial developed for human therapy should not be used in animals.” Dr. Collignon’s WHO Advisory Group followed two essential criteria to designate antimicrobials of utmost importance to human health in the new study: 1. antimicrobials that are the sole, or one of limited available therapies, to treat serious bacterial infections in people and 2. antimicrobials used to treat infections in people caused by either (a) bacteria that may be transmitted to humans from nonhuman sources or (b) bacteria that may acquire resistance genes from nonhuman sources.

The highest-priority and most critically important antimicrobials are those which meet the criteria listed above and that are used in greatest volume or highest frequency by humans. Another criteria for prioritization involves antimicrobial classes where evidence suggests that the “transmission of resistant bacteria or resistance genes from nonhuman sources is already occurring, or has occurred previously.” Quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides were the only antimicrobials that met all criteria for prioritization.

“Antimicrobial resistance remains a threat to human health and drivers of resistance act in all sectors; human, animal, and the environment,” the WHO Advisory Group concluded. “Prioritizing the antimicrobials that are critically important for humans is a valuable and strategic risk-management tool and will be improved with the evidence-based approach which is currently underway.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475).

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Fourth U.S. case of mcr-1–resistance gene reported

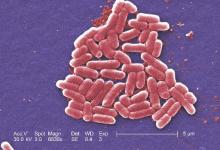

A fourth case of bacterial infection harboring the mcr-1 gene has been reported in a child recently returned from a visit to the Caribbean, according to a case report published Sept. 9 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The mcr-1 gene, which confers resistance to the last-resort antibiotic colistin, was first reported in China and is the first plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance mechanism to be identified. Since its discovery in 2015, cases have been reported in Africa, Asia, Europe, South America, and North America.

In this case report, a young patient developed fever and bloody diarrhea 2 days before returning to the United States from a 2-week visit to the Caribbean. The child were treated with the paromomycin and a stool specimen was collected on June 16, with follow-up cultures on June 18 and June 23.

All revealed Escherichia coli O157 harboring mcr-1. The isolates also carried a plasmid blaCMY-2 gene, which confers resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. Stool cultures taken on June 24 and July 1 were negative for E. coli O157 (MMWR. 2016 Sep 9. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6536e3).

Family members in close contact with the patient also were tested; all were found to be negative. Similarly, 16 environmental samples collected from the kitchen and diaper-changing area of the patient’s home were negative for mcr-1.

Researchers reported that the patient was “typically healthy,” and the child’s diet included fruit, dairy products, and meat. While on vacation in the Caribbean, the child ate meat purchased at a live animal market but did not visit the market personally. The child also had contact with a pet dog and cat.

“At this time, CDC recommends that Enterobacteriaceae isolates with a colistin or polymyxin B MIC plus or minus 4 mcg/mL be tested for the presence of mcr-1; testing is available through CDC,” wrote Dr. Amber M. Vasquez and her colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Prompt reporting of mcr-1–carrying isolates to public health officials allows for a rapid response to identify transmission and limit further spread.”

A fourth case of bacterial infection harboring the mcr-1 gene has been reported in a child recently returned from a visit to the Caribbean, according to a case report published Sept. 9 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The mcr-1 gene, which confers resistance to the last-resort antibiotic colistin, was first reported in China and is the first plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance mechanism to be identified. Since its discovery in 2015, cases have been reported in Africa, Asia, Europe, South America, and North America.

In this case report, a young patient developed fever and bloody diarrhea 2 days before returning to the United States from a 2-week visit to the Caribbean. The child were treated with the paromomycin and a stool specimen was collected on June 16, with follow-up cultures on June 18 and June 23.

All revealed Escherichia coli O157 harboring mcr-1. The isolates also carried a plasmid blaCMY-2 gene, which confers resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. Stool cultures taken on June 24 and July 1 were negative for E. coli O157 (MMWR. 2016 Sep 9. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6536e3).

Family members in close contact with the patient also were tested; all were found to be negative. Similarly, 16 environmental samples collected from the kitchen and diaper-changing area of the patient’s home were negative for mcr-1.

Researchers reported that the patient was “typically healthy,” and the child’s diet included fruit, dairy products, and meat. While on vacation in the Caribbean, the child ate meat purchased at a live animal market but did not visit the market personally. The child also had contact with a pet dog and cat.

“At this time, CDC recommends that Enterobacteriaceae isolates with a colistin or polymyxin B MIC plus or minus 4 mcg/mL be tested for the presence of mcr-1; testing is available through CDC,” wrote Dr. Amber M. Vasquez and her colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Prompt reporting of mcr-1–carrying isolates to public health officials allows for a rapid response to identify transmission and limit further spread.”

A fourth case of bacterial infection harboring the mcr-1 gene has been reported in a child recently returned from a visit to the Caribbean, according to a case report published Sept. 9 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The mcr-1 gene, which confers resistance to the last-resort antibiotic colistin, was first reported in China and is the first plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance mechanism to be identified. Since its discovery in 2015, cases have been reported in Africa, Asia, Europe, South America, and North America.

In this case report, a young patient developed fever and bloody diarrhea 2 days before returning to the United States from a 2-week visit to the Caribbean. The child were treated with the paromomycin and a stool specimen was collected on June 16, with follow-up cultures on June 18 and June 23.

All revealed Escherichia coli O157 harboring mcr-1. The isolates also carried a plasmid blaCMY-2 gene, which confers resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. Stool cultures taken on June 24 and July 1 were negative for E. coli O157 (MMWR. 2016 Sep 9. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6536e3).

Family members in close contact with the patient also were tested; all were found to be negative. Similarly, 16 environmental samples collected from the kitchen and diaper-changing area of the patient’s home were negative for mcr-1.

Researchers reported that the patient was “typically healthy,” and the child’s diet included fruit, dairy products, and meat. While on vacation in the Caribbean, the child ate meat purchased at a live animal market but did not visit the market personally. The child also had contact with a pet dog and cat.

“At this time, CDC recommends that Enterobacteriaceae isolates with a colistin or polymyxin B MIC plus or minus 4 mcg/mL be tested for the presence of mcr-1; testing is available through CDC,” wrote Dr. Amber M. Vasquez and her colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Prompt reporting of mcr-1–carrying isolates to public health officials allows for a rapid response to identify transmission and limit further spread.”

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Antibiotic susceptibility differs in transplant recipients

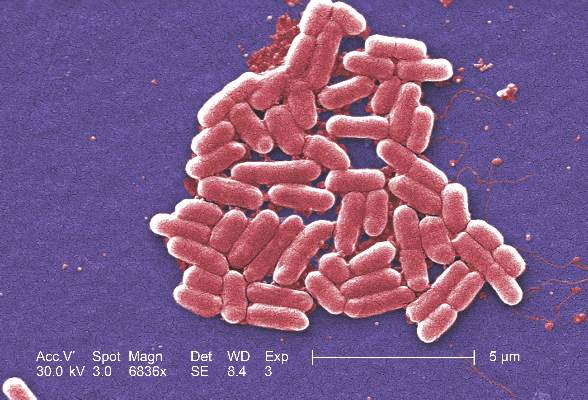

Antibiotic susceptibility in bacteria cultured from transplant recipients at a single hospital differed markedly from that in hospital-wide antibiograms, according to a report published in Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease.

Understanding the differences in antibiotic susceptibility among these highly immunocompromised patients can help guide treatment when they develop infection, and reduce the delay before they begin receiving appropriate antibiotics, said Rossana Rosa, MD, of Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, and her associates.

The investigators examined the antibiotic susceptibility of 1,889 isolates from blood and urine specimens taken from patients who had received solid-organ transplants at a single tertiary-care teaching hospital and then developed bacterial infections during a 2-year period. These patients included both children and adults who had received kidney, pancreas, liver, heart, lung, or intestinal transplants and were treated in numerous, “geographically distributed” units throughout the hospital. Their culture results were compared with those from 10,439 other patients with bacterial infections, which comprised the hospital-wide antibiograms developed every 6 months during the study period.

The Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the transplant recipients showed markedly less susceptibility to first-line antibiotics than would have been predicted by the hospital-antibiograms. In particular, in the transplant recipients E. coli infections were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, levofloxacin, and ceftriaxone; K. pneumoniae infections were resistant to every antibiotic except amikacin; and P. aeruginosa infections were resistant to levofloxacin, cefepime, and amikacin (Diag Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 25. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.08.018).

“We advocate for the development of antibiograms specific to solid-organ transplant recipients. This may allow intrahospital comparisons and intertransplant-center monitoring of trends in antimicrobial resistance over time,” Dr. Rosa and her associates said.

Antibiotic susceptibility in bacteria cultured from transplant recipients at a single hospital differed markedly from that in hospital-wide antibiograms, according to a report published in Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease.

Understanding the differences in antibiotic susceptibility among these highly immunocompromised patients can help guide treatment when they develop infection, and reduce the delay before they begin receiving appropriate antibiotics, said Rossana Rosa, MD, of Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, and her associates.

The investigators examined the antibiotic susceptibility of 1,889 isolates from blood and urine specimens taken from patients who had received solid-organ transplants at a single tertiary-care teaching hospital and then developed bacterial infections during a 2-year period. These patients included both children and adults who had received kidney, pancreas, liver, heart, lung, or intestinal transplants and were treated in numerous, “geographically distributed” units throughout the hospital. Their culture results were compared with those from 10,439 other patients with bacterial infections, which comprised the hospital-wide antibiograms developed every 6 months during the study period.

The Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the transplant recipients showed markedly less susceptibility to first-line antibiotics than would have been predicted by the hospital-antibiograms. In particular, in the transplant recipients E. coli infections were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, levofloxacin, and ceftriaxone; K. pneumoniae infections were resistant to every antibiotic except amikacin; and P. aeruginosa infections were resistant to levofloxacin, cefepime, and amikacin (Diag Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 25. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.08.018).

“We advocate for the development of antibiograms specific to solid-organ transplant recipients. This may allow intrahospital comparisons and intertransplant-center monitoring of trends in antimicrobial resistance over time,” Dr. Rosa and her associates said.

Antibiotic susceptibility in bacteria cultured from transplant recipients at a single hospital differed markedly from that in hospital-wide antibiograms, according to a report published in Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease.

Understanding the differences in antibiotic susceptibility among these highly immunocompromised patients can help guide treatment when they develop infection, and reduce the delay before they begin receiving appropriate antibiotics, said Rossana Rosa, MD, of Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, and her associates.

The investigators examined the antibiotic susceptibility of 1,889 isolates from blood and urine specimens taken from patients who had received solid-organ transplants at a single tertiary-care teaching hospital and then developed bacterial infections during a 2-year period. These patients included both children and adults who had received kidney, pancreas, liver, heart, lung, or intestinal transplants and were treated in numerous, “geographically distributed” units throughout the hospital. Their culture results were compared with those from 10,439 other patients with bacterial infections, which comprised the hospital-wide antibiograms developed every 6 months during the study period.

The Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the transplant recipients showed markedly less susceptibility to first-line antibiotics than would have been predicted by the hospital-antibiograms. In particular, in the transplant recipients E. coli infections were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, levofloxacin, and ceftriaxone; K. pneumoniae infections were resistant to every antibiotic except amikacin; and P. aeruginosa infections were resistant to levofloxacin, cefepime, and amikacin (Diag Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 25. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.08.018).

“We advocate for the development of antibiograms specific to solid-organ transplant recipients. This may allow intrahospital comparisons and intertransplant-center monitoring of trends in antimicrobial resistance over time,” Dr. Rosa and her associates said.

FROM DIAGNOSTIC MICROBIOLOGY AND INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Key clinical point: Antibiotic susceptibility in bacteria cultured from transplant recipients differs markedly from that in hospital-wide antibiograms.

Major finding: In the transplant recipients, E. coli infections were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, levofloxacin, and ceftriaxone; K. pneumoniae infections were resistant to every antibiotic except amikacin; and P. aeruginosa infections were resistant to levofloxacin, cefepime, and amikacin.

Data source: A single-center study comparing the antibiotic susceptibility of 1,889 bacterial isolates from transplant recipients with 10,439 isolates from other patients.

Disclosures: This study was not supported by funding from any public, commercial, or not-for-profit entities. Dr. Rosa and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FDA rule will pull many consumer antibacterial soaps from market

Over-the-counter consumer antiseptic wash products with active ingredients such as triclosan and triclocarban will be pulled from the market, following a final rule issued Sept. 2 by the Food and Drug Administration.

Companies will no longer be able to sell antibacterial washes with those ingredients, the FDA said, because manufacturers failed to show the ingredients are safe for long-term daily use and are better than plain soap and water at preventing illness and the spread of infections.

The final rule targets consumer antiseptic wash products containing 1 or more of 19 active ingredients, including the 2 most commonly used ingredients, triclosan and triclocarban. Companies have 1 year to comply with the new rule.

The FDA’s rule does not apply to hand sanitizers, wipes, or antibacterial products used in health care settings.

The agency has deferred for 1 year a decision on the continued use of three other ingredients in consumer wash products: benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride, and chloroxylenol.

The FDA’s decision was driven in part by concerns about the risks posed by long-term exposure to such products, including bacterial resistance or hormonal effects.

“Consumers may think antibacterial washes are more effective at preventing the spread of germs, but we have no scientific evidence that they are any better than plain soap and water,” said Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a statement. “In fact, some data suggest that antibacterial ingredients may do more harm than good over the long term.”

Washing with plain soap and water remains one of the most important steps consumers can take to prevent illness and the spread of infection, the FDA advised. The agency also recommended use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol.

Read the full press release on the FDA website.

Over-the-counter consumer antiseptic wash products with active ingredients such as triclosan and triclocarban will be pulled from the market, following a final rule issued Sept. 2 by the Food and Drug Administration.

Companies will no longer be able to sell antibacterial washes with those ingredients, the FDA said, because manufacturers failed to show the ingredients are safe for long-term daily use and are better than plain soap and water at preventing illness and the spread of infections.

The final rule targets consumer antiseptic wash products containing 1 or more of 19 active ingredients, including the 2 most commonly used ingredients, triclosan and triclocarban. Companies have 1 year to comply with the new rule.

The FDA’s rule does not apply to hand sanitizers, wipes, or antibacterial products used in health care settings.

The agency has deferred for 1 year a decision on the continued use of three other ingredients in consumer wash products: benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride, and chloroxylenol.

The FDA’s decision was driven in part by concerns about the risks posed by long-term exposure to such products, including bacterial resistance or hormonal effects.

“Consumers may think antibacterial washes are more effective at preventing the spread of germs, but we have no scientific evidence that they are any better than plain soap and water,” said Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a statement. “In fact, some data suggest that antibacterial ingredients may do more harm than good over the long term.”

Washing with plain soap and water remains one of the most important steps consumers can take to prevent illness and the spread of infection, the FDA advised. The agency also recommended use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol.

Read the full press release on the FDA website.

Over-the-counter consumer antiseptic wash products with active ingredients such as triclosan and triclocarban will be pulled from the market, following a final rule issued Sept. 2 by the Food and Drug Administration.

Companies will no longer be able to sell antibacterial washes with those ingredients, the FDA said, because manufacturers failed to show the ingredients are safe for long-term daily use and are better than plain soap and water at preventing illness and the spread of infections.

The final rule targets consumer antiseptic wash products containing 1 or more of 19 active ingredients, including the 2 most commonly used ingredients, triclosan and triclocarban. Companies have 1 year to comply with the new rule.

The FDA’s rule does not apply to hand sanitizers, wipes, or antibacterial products used in health care settings.

The agency has deferred for 1 year a decision on the continued use of three other ingredients in consumer wash products: benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride, and chloroxylenol.

The FDA’s decision was driven in part by concerns about the risks posed by long-term exposure to such products, including bacterial resistance or hormonal effects.

“Consumers may think antibacterial washes are more effective at preventing the spread of germs, but we have no scientific evidence that they are any better than plain soap and water,” said Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a statement. “In fact, some data suggest that antibacterial ingredients may do more harm than good over the long term.”

Washing with plain soap and water remains one of the most important steps consumers can take to prevent illness and the spread of infection, the FDA advised. The agency also recommended use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol.

Read the full press release on the FDA website.

When should primary care physicians prescribe antibiotics to children with respiratory infection symptoms?

Duration of illness, age, and the presence of specific symptoms are key predictors of hospitalization risk due to respiratory infection, according to a study published in The Lancet. These demographic and clinical factors should guide a primary care physician’s decision to prescribe antibiotics.

“More than 80% of all health-service antibiotics [are] prescribed by primary care clinicians,” reported Alastair Hay, MD, of the University of Bristol, England, and his associates.

“Antibiotic prescribing in primary care is increasing and directly affects antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers noted, adding that many primary care clinicians prescribe antibiotics to pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections and/or cough to “mitigate perceived risk of future hospital admission and complications.”

A total of 8,394 pediatric patients who presented with acute cough and one or more other symptoms of respiratory tract infection (such as fever and coryza) were enrolled in the study by primary care physicians at 247 clinical sites in England. All eligible patients were between the ages of 3 months and 16 years; children were excluded if they presented with noninfective exacerbation of asthma, were at high risk of serious infection, or required a throat swab. The study’s primary outcome was hospital admission for any respiratory tract infection within 30 days of enrollment; the data were collected from a review of electronic medical records (Lancet. 2016. Sept 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[16]30223-5).

The median age of the pediatric cohort was 3 years, 52% were male, and 78% were white. A total of 3,121 patients (37%) were prescribed an antibiotic by their primary care physicians, but only 78 patients (0.9%) were admitted to the hospital, and 27% of discharge diagnoses suggested a possible bacterial cause (lower respiratory tract infection, tonsillitis, and pneumonia).

Multivariate modeling with bootstrap validation demonstrated that duration of illness, age, and the presence or absence of specific respiratory symptoms were the key factors that should be used to identify children at low, normal, and high risk for hospitalization due to respiratory infection. Younger patients with shorter illness durations who presented with wheeze, fever, vomiting, intercostal or subcostal recession, and/or asthma were at higher risk for hospitalization.

“Our data show that 1,846 (33%) of the very-low-risk stratum children received antibiotics. Because these children represent the majority (67%) of all the participants, a 10% overall reduction in antibiotic prescription would be achieved if prescription in this group halved, remained static in the normal risk stratum, and increased to 90% in the high risk stratum, resulting in a similar effect size to other contemporary antimicrobial stewardship interventions,” Dr. Hay and his associates concluded.

This study received funding and sponsorship from the National Institute for Health Research and the University of Bristol. Two investigators reported receiving financial compensation or honoraria from multiple companies including companies with an interest in diagnostic microbiology in respiratory tract infections.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Duration of illness, age, and the presence of specific symptoms are key predictors of hospitalization risk due to respiratory infection, according to a study published in The Lancet. These demographic and clinical factors should guide a primary care physician’s decision to prescribe antibiotics.

“More than 80% of all health-service antibiotics [are] prescribed by primary care clinicians,” reported Alastair Hay, MD, of the University of Bristol, England, and his associates.

“Antibiotic prescribing in primary care is increasing and directly affects antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers noted, adding that many primary care clinicians prescribe antibiotics to pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections and/or cough to “mitigate perceived risk of future hospital admission and complications.”

A total of 8,394 pediatric patients who presented with acute cough and one or more other symptoms of respiratory tract infection (such as fever and coryza) were enrolled in the study by primary care physicians at 247 clinical sites in England. All eligible patients were between the ages of 3 months and 16 years; children were excluded if they presented with noninfective exacerbation of asthma, were at high risk of serious infection, or required a throat swab. The study’s primary outcome was hospital admission for any respiratory tract infection within 30 days of enrollment; the data were collected from a review of electronic medical records (Lancet. 2016. Sept 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[16]30223-5).

The median age of the pediatric cohort was 3 years, 52% were male, and 78% were white. A total of 3,121 patients (37%) were prescribed an antibiotic by their primary care physicians, but only 78 patients (0.9%) were admitted to the hospital, and 27% of discharge diagnoses suggested a possible bacterial cause (lower respiratory tract infection, tonsillitis, and pneumonia).

Multivariate modeling with bootstrap validation demonstrated that duration of illness, age, and the presence or absence of specific respiratory symptoms were the key factors that should be used to identify children at low, normal, and high risk for hospitalization due to respiratory infection. Younger patients with shorter illness durations who presented with wheeze, fever, vomiting, intercostal or subcostal recession, and/or asthma were at higher risk for hospitalization.

“Our data show that 1,846 (33%) of the very-low-risk stratum children received antibiotics. Because these children represent the majority (67%) of all the participants, a 10% overall reduction in antibiotic prescription would be achieved if prescription in this group halved, remained static in the normal risk stratum, and increased to 90% in the high risk stratum, resulting in a similar effect size to other contemporary antimicrobial stewardship interventions,” Dr. Hay and his associates concluded.

This study received funding and sponsorship from the National Institute for Health Research and the University of Bristol. Two investigators reported receiving financial compensation or honoraria from multiple companies including companies with an interest in diagnostic microbiology in respiratory tract infections.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Duration of illness, age, and the presence of specific symptoms are key predictors of hospitalization risk due to respiratory infection, according to a study published in The Lancet. These demographic and clinical factors should guide a primary care physician’s decision to prescribe antibiotics.

“More than 80% of all health-service antibiotics [are] prescribed by primary care clinicians,” reported Alastair Hay, MD, of the University of Bristol, England, and his associates.

“Antibiotic prescribing in primary care is increasing and directly affects antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers noted, adding that many primary care clinicians prescribe antibiotics to pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections and/or cough to “mitigate perceived risk of future hospital admission and complications.”

A total of 8,394 pediatric patients who presented with acute cough and one or more other symptoms of respiratory tract infection (such as fever and coryza) were enrolled in the study by primary care physicians at 247 clinical sites in England. All eligible patients were between the ages of 3 months and 16 years; children were excluded if they presented with noninfective exacerbation of asthma, were at high risk of serious infection, or required a throat swab. The study’s primary outcome was hospital admission for any respiratory tract infection within 30 days of enrollment; the data were collected from a review of electronic medical records (Lancet. 2016. Sept 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[16]30223-5).

The median age of the pediatric cohort was 3 years, 52% were male, and 78% were white. A total of 3,121 patients (37%) were prescribed an antibiotic by their primary care physicians, but only 78 patients (0.9%) were admitted to the hospital, and 27% of discharge diagnoses suggested a possible bacterial cause (lower respiratory tract infection, tonsillitis, and pneumonia).

Multivariate modeling with bootstrap validation demonstrated that duration of illness, age, and the presence or absence of specific respiratory symptoms were the key factors that should be used to identify children at low, normal, and high risk for hospitalization due to respiratory infection. Younger patients with shorter illness durations who presented with wheeze, fever, vomiting, intercostal or subcostal recession, and/or asthma were at higher risk for hospitalization.

“Our data show that 1,846 (33%) of the very-low-risk stratum children received antibiotics. Because these children represent the majority (67%) of all the participants, a 10% overall reduction in antibiotic prescription would be achieved if prescription in this group halved, remained static in the normal risk stratum, and increased to 90% in the high risk stratum, resulting in a similar effect size to other contemporary antimicrobial stewardship interventions,” Dr. Hay and his associates concluded.

This study received funding and sponsorship from the National Institute for Health Research and the University of Bristol. Two investigators reported receiving financial compensation or honoraria from multiple companies including companies with an interest in diagnostic microbiology in respiratory tract infections.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Duration of illness, age, and the presence of specific symptoms are key predictors of hospitalization risk due to respiratory infection. These factors should guide a primary care physician’s decision to prescribe antibiotics.

Major finding: Younger patients with shorter illness durations who presented with wheeze, fever, vomiting, intercostal or subcostal recession, and/or asthma are at higher risk for hospitalization.

Data source: A prospective, prognostic cohort study of 8,394 children.

Disclosures: This study received funding and sponsorship from the National Institute for Health Research and the University of Bristol. Two investigators reported receiving financial compensation or honoraria from multiple companies, including those with an interest in diagnostic microbiology in respiratory tract infections.

Hospitals increase CRE risk when they share patients

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with CRE, especially if long-term acute care hospitals are in the mix.

Major finding: Sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases (P = 0.11).

Data source: 185 Illinois hospitals.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

Antibiotics overprescribed during asthma-related hospitalizations

Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations, even though guidelines recommend against prescribing antibiotics during exacerbations of asthma in the absence of concurrent infection, reported Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, of Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and his colleagues.

They examined the hospitalization records of 51,951 individuals admitted to 577 hospitals in the United States between 2013 and 2014 with a principal diagnosis of either asthma or acute respiratory failure combined with asthma as a secondary diagnosis. Each patient type and the timing of antibiotic therapy was noted.

A total of 30,226 of the 51,951 patients (58.2%) were prescribed antibiotics at some point during their hospitalization, while 21,248 (40.9%) were prescribed antibiotics on the first day of hospitalization, without “documentation of an indication for antibiotic therapy.”

Macrolides were most commonly prescribed, given to 9,633 (18.5%) of patients, followed by quinolones (8,632, 16.1%), third-generation cephalosporins (4,420, 8.5%), and tetracyclines (1,858, 3.6%). After adjustment for risk variables, chronic obstructive asthma hospitalizations were found to be those most highly associated with receiving antibiotics (odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.5-1.7).

“Possible explanations for this high rate of potentially inappropriate treatment include the challenge of differentiating bacterial from nonbacterial infections, distinguishing asthma from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the acute care setting, and gaps in knowledge about the benefits of antibiotic therapy,” the authors posited, adding that these findings “suggest a significant opportunity to improve patient safety, reduce the spread of resistance, and lower spending through greater adherence to guideline recommendations.”

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. Dr. Lindenauer and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations, even though guidelines recommend against prescribing antibiotics during exacerbations of asthma in the absence of concurrent infection, reported Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, of Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and his colleagues.

They examined the hospitalization records of 51,951 individuals admitted to 577 hospitals in the United States between 2013 and 2014 with a principal diagnosis of either asthma or acute respiratory failure combined with asthma as a secondary diagnosis. Each patient type and the timing of antibiotic therapy was noted.

A total of 30,226 of the 51,951 patients (58.2%) were prescribed antibiotics at some point during their hospitalization, while 21,248 (40.9%) were prescribed antibiotics on the first day of hospitalization, without “documentation of an indication for antibiotic therapy.”

Macrolides were most commonly prescribed, given to 9,633 (18.5%) of patients, followed by quinolones (8,632, 16.1%), third-generation cephalosporins (4,420, 8.5%), and tetracyclines (1,858, 3.6%). After adjustment for risk variables, chronic obstructive asthma hospitalizations were found to be those most highly associated with receiving antibiotics (odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.5-1.7).

“Possible explanations for this high rate of potentially inappropriate treatment include the challenge of differentiating bacterial from nonbacterial infections, distinguishing asthma from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the acute care setting, and gaps in knowledge about the benefits of antibiotic therapy,” the authors posited, adding that these findings “suggest a significant opportunity to improve patient safety, reduce the spread of resistance, and lower spending through greater adherence to guideline recommendations.”

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. Dr. Lindenauer and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations, even though guidelines recommend against prescribing antibiotics during exacerbations of asthma in the absence of concurrent infection, reported Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, of Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and his colleagues.

They examined the hospitalization records of 51,951 individuals admitted to 577 hospitals in the United States between 2013 and 2014 with a principal diagnosis of either asthma or acute respiratory failure combined with asthma as a secondary diagnosis. Each patient type and the timing of antibiotic therapy was noted.

A total of 30,226 of the 51,951 patients (58.2%) were prescribed antibiotics at some point during their hospitalization, while 21,248 (40.9%) were prescribed antibiotics on the first day of hospitalization, without “documentation of an indication for antibiotic therapy.”

Macrolides were most commonly prescribed, given to 9,633 (18.5%) of patients, followed by quinolones (8,632, 16.1%), third-generation cephalosporins (4,420, 8.5%), and tetracyclines (1,858, 3.6%). After adjustment for risk variables, chronic obstructive asthma hospitalizations were found to be those most highly associated with receiving antibiotics (odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.5-1.7).

“Possible explanations for this high rate of potentially inappropriate treatment include the challenge of differentiating bacterial from nonbacterial infections, distinguishing asthma from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the acute care setting, and gaps in knowledge about the benefits of antibiotic therapy,” the authors posited, adding that these findings “suggest a significant opportunity to improve patient safety, reduce the spread of resistance, and lower spending through greater adherence to guideline recommendations.”

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. Dr. Lindenauer and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations.

Major finding: Among patients hospitalized for asthma, 58.2% had received antibiotics without any documentation or indication for such therapy.

Data source: Retrospective study of 51,951 patients in 577 U.S. hospitals from 2013 to 2014.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. The researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Clinical decision tree pinpointed risk of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteremia

A new classification tool helped guide the treatment of bacteremic patients while clinicians awaited antibiotic resistance results, investigators reported.

The clinical decision tree had a positive predictive value of 91% and a negative predictive value of 92% for determining whether certain gram-negative infections produced extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), Catherine Goodman, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and her associates wrote online in Clinical Infectious Diseases. “These predictions may assist empiric treatment decisions in order to optimize clinical outcomes while reducing administration of overly broad antibiotic agents that can select for further resistance emergence,” they added.

Bacteria that produce ESBL can hydrolyze all broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics except carbapenems. Rapid tests for beta-lactamase genes can shorten the lag time between gram-stain identification and antimicrobial resistance results, but are cost prohibitive for most clinical laboratories and often do not assess ESBL gene groups, the researchers said. To find a way to predict which infections are characterized by ESBL production, they studied adults hospitalized at Johns Hopkins from October 2008 to March 2015 with bloodstream isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae (40% of patients), Klebsiella oxytoca (4% of patients), and Escherichia coli (56% of patients). Most bacteremias began as urinary tract infections (34% of cases), followed by intra-abdominal infections (24%), catheter-related infections (16%), and biliary infections (14%) (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Jul 26. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw425).

A total of 194 patients (15%) had bacteremias that produced ESBL, according to the investigators. Using a technique called binary recursive partitioning, they compared these patients with ESBL-negative patients to create a clinical decision tree based on five yes-or-no questions. The tree first asked if the patient had been colonized or infected with ESBL-producing bacteria within 6 months, and if so, whether the patient currently had an indwelling catheter. Patients meeting both criteria had a 92% chance of being ESBL positive. Patients with a recent history of ESBL but no catheter had an 81% chance of being ESBL positive if they were at least 43 years old, but a 75% chance of being ESBL negative if they were under age 43 years.

Among patients with no recent history of ESBL, the decision tree asked about hospitalization in a country with a high ESBL burden and antibiotic therapy during the past 6 months. Patients responding “yes” to both questions had a 100% chance of being ESBL positive. Patients with only the geographic risk factor had a 63% chance of being ESBL negative, and patients with neither risk factor had a 93% chance of being ESBL negative.

The decision tree detected only half of ESBL cases because there was a subgroup with no recent ESBL history or geographic exposure, the investigators noted. “The poor predictive nature of health care–associated variables within this patient subset may suggest a high proportion of community-acquired ESBL infections. Indeed, although risk factors for ESBLs have traditionally focused on the health care setting, increasing reports describe the community as an important ESBL reservoir,” they added. Nonetheless, of 194 patients with ESBL bacteremia, 35% received empiric carbapenem treatment within 6 hours after identification of the bacterial genus and species, the investigators emphasized. “Utilization of the decision tree would have increased ESBL case detection during the empiric treatment window by approximately 50%.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

A new classification tool helped guide the treatment of bacteremic patients while clinicians awaited antibiotic resistance results, investigators reported.

The clinical decision tree had a positive predictive value of 91% and a negative predictive value of 92% for determining whether certain gram-negative infections produced extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), Catherine Goodman, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and her associates wrote online in Clinical Infectious Diseases. “These predictions may assist empiric treatment decisions in order to optimize clinical outcomes while reducing administration of overly broad antibiotic agents that can select for further resistance emergence,” they added.

Bacteria that produce ESBL can hydrolyze all broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics except carbapenems. Rapid tests for beta-lactamase genes can shorten the lag time between gram-stain identification and antimicrobial resistance results, but are cost prohibitive for most clinical laboratories and often do not assess ESBL gene groups, the researchers said. To find a way to predict which infections are characterized by ESBL production, they studied adults hospitalized at Johns Hopkins from October 2008 to March 2015 with bloodstream isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae (40% of patients), Klebsiella oxytoca (4% of patients), and Escherichia coli (56% of patients). Most bacteremias began as urinary tract infections (34% of cases), followed by intra-abdominal infections (24%), catheter-related infections (16%), and biliary infections (14%) (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Jul 26. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw425).

A total of 194 patients (15%) had bacteremias that produced ESBL, according to the investigators. Using a technique called binary recursive partitioning, they compared these patients with ESBL-negative patients to create a clinical decision tree based on five yes-or-no questions. The tree first asked if the patient had been colonized or infected with ESBL-producing bacteria within 6 months, and if so, whether the patient currently had an indwelling catheter. Patients meeting both criteria had a 92% chance of being ESBL positive. Patients with a recent history of ESBL but no catheter had an 81% chance of being ESBL positive if they were at least 43 years old, but a 75% chance of being ESBL negative if they were under age 43 years.

Among patients with no recent history of ESBL, the decision tree asked about hospitalization in a country with a high ESBL burden and antibiotic therapy during the past 6 months. Patients responding “yes” to both questions had a 100% chance of being ESBL positive. Patients with only the geographic risk factor had a 63% chance of being ESBL negative, and patients with neither risk factor had a 93% chance of being ESBL negative.

The decision tree detected only half of ESBL cases because there was a subgroup with no recent ESBL history or geographic exposure, the investigators noted. “The poor predictive nature of health care–associated variables within this patient subset may suggest a high proportion of community-acquired ESBL infections. Indeed, although risk factors for ESBLs have traditionally focused on the health care setting, increasing reports describe the community as an important ESBL reservoir,” they added. Nonetheless, of 194 patients with ESBL bacteremia, 35% received empiric carbapenem treatment within 6 hours after identification of the bacterial genus and species, the investigators emphasized. “Utilization of the decision tree would have increased ESBL case detection during the empiric treatment window by approximately 50%.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

A new classification tool helped guide the treatment of bacteremic patients while clinicians awaited antibiotic resistance results, investigators reported.

The clinical decision tree had a positive predictive value of 91% and a negative predictive value of 92% for determining whether certain gram-negative infections produced extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), Catherine Goodman, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and her associates wrote online in Clinical Infectious Diseases. “These predictions may assist empiric treatment decisions in order to optimize clinical outcomes while reducing administration of overly broad antibiotic agents that can select for further resistance emergence,” they added.

Bacteria that produce ESBL can hydrolyze all broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics except carbapenems. Rapid tests for beta-lactamase genes can shorten the lag time between gram-stain identification and antimicrobial resistance results, but are cost prohibitive for most clinical laboratories and often do not assess ESBL gene groups, the researchers said. To find a way to predict which infections are characterized by ESBL production, they studied adults hospitalized at Johns Hopkins from October 2008 to March 2015 with bloodstream isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae (40% of patients), Klebsiella oxytoca (4% of patients), and Escherichia coli (56% of patients). Most bacteremias began as urinary tract infections (34% of cases), followed by intra-abdominal infections (24%), catheter-related infections (16%), and biliary infections (14%) (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Jul 26. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw425).

A total of 194 patients (15%) had bacteremias that produced ESBL, according to the investigators. Using a technique called binary recursive partitioning, they compared these patients with ESBL-negative patients to create a clinical decision tree based on five yes-or-no questions. The tree first asked if the patient had been colonized or infected with ESBL-producing bacteria within 6 months, and if so, whether the patient currently had an indwelling catheter. Patients meeting both criteria had a 92% chance of being ESBL positive. Patients with a recent history of ESBL but no catheter had an 81% chance of being ESBL positive if they were at least 43 years old, but a 75% chance of being ESBL negative if they were under age 43 years.

Among patients with no recent history of ESBL, the decision tree asked about hospitalization in a country with a high ESBL burden and antibiotic therapy during the past 6 months. Patients responding “yes” to both questions had a 100% chance of being ESBL positive. Patients with only the geographic risk factor had a 63% chance of being ESBL negative, and patients with neither risk factor had a 93% chance of being ESBL negative.

The decision tree detected only half of ESBL cases because there was a subgroup with no recent ESBL history or geographic exposure, the investigators noted. “The poor predictive nature of health care–associated variables within this patient subset may suggest a high proportion of community-acquired ESBL infections. Indeed, although risk factors for ESBLs have traditionally focused on the health care setting, increasing reports describe the community as an important ESBL reservoir,” they added. Nonetheless, of 194 patients with ESBL bacteremia, 35% received empiric carbapenem treatment within 6 hours after identification of the bacterial genus and species, the investigators emphasized. “Utilization of the decision tree would have increased ESBL case detection during the empiric treatment window by approximately 50%.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: A clinical decision tree helped identify bacteria producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases.

Major finding: The positive predictive value was 91%, and the negative predictive value was 92%.

Data source: A single-center retrospective study of 1,288 adults with blood isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, or Escherichia coli.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Most sepsis cases begin outside of the hospital

Sepsis is a medical emergency that begins outside of the hospital in 79% of cases. In addition, 72% of patients with sepsis had recently used healthcare services or had chronic diseases that required frequent medical care.

Those are key findings from a special report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533e1).

“The treatment of sepsis is a race against time,” CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, said during a media teleconference about the report. “We can protect more people from sepsis by informing patients and their families, treating infections promptly, and acting fast when sepsis does occur.”

Each year, between 1 and 3 million people in the United States are diagnosed with sepsis, a syndrome marked by the body’s overwhelming and life-threatening response to an infection, Dr. Frieden said. Of these, 15%-30% will die from the condition, for which there is no blood test. “Health care providers are on the front lines of both sepsis prevention and early recognition,” he emphasized. “Prevention really is possible.” For example, he continued, if a patient with diabetes visits their regular doctor and is found to have increased blood sugar and a small wound on their foot, “this is a prime opportunity to think about infection and reduce the risk of sepsis. In addition to treating the infection, the clinician can inform the patient and family members about how to care for the wound, how to recognize the signs that the infection may be getting worse, and when to seek additional medical care. If the infection gets worse the patient could be at risk for sepsis. Taking the opportunity to both treat and inform patients could save their life, and helping patients know to ask, ‘Could this be sepsis?’ empowers patients and families and could save lives.”

In an effort to describe the characteristics of patients with sepsis, researchers from the CDC and from New York State conducted a retrospective review of medical records from 246 adults and 79 children with sepsis who were treated at four New York hospitals. They found that sepsis most often occurs in patients older than age 65 years and in infants younger than 1 year of age, and the median hospital length of stay is 10 days. Six key signs and symptoms of sepsis were shivering or feeling cold; pain or discomfort; clammy or sweaty skin; being confused or disoriented; shortness of breath, and having a rapid heartbeat. “People with chronic diseases such as diabetes or weakened immune systems from things like tobacco use are at higher risk of sepsis,” Dr. Frieden said. “But even healthy people can develop sepsis from an infection, especially if it’s not treated properly and promptly.”

The four types of infections most commonly associated with sepsis include those involving the lungs, urinary tract, skin, and intestines, while the most common germs that can cause sepsis are Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli (E. coli), and some types of Streptococcus. Infection prevention strategies such as increasing vaccination rates for pneumococcal disease and for influenza are likely to reduce the incidence of sepsis, according to the report. “We could also improve infections by improving handwashing at health care facilities as well as in the community,” Dr. Frieden added. “We can [also] improve recognition of sepsis both in the community and in health care facilities and act fast if sepsis is suspected in a patient. We’ve been able to reduce the rates of some infections that cause sepsis in health care facilities by half, but preventing more infections and stopping the spread of antibiotic resistant infections will protect even more patients from sepsis.”

Mitchell Levy, MD, founding member of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, said during the teleconference that clinicians have made “tremendous progress in sepsis,” despite current challenges. “First, we now understand the importance of early identification and treatment of sepsis,” he said. “Second, we have seen improved survival through routine screening and treatment that is integrated into the work flow of hospitals. And third, frontline health care providers really do make a difference. What’s clear is that we need to expand these successes to other parts of hospitals and to other care locations.”

Forthcoming free CDC webinars related to sepsis for health care providers include one on Sept. 13 at 3 p.m., ET, entitled “Advances in Sepsis: Protecting Patients Throughout the Lifespan.” Another webinar will be offered on Sept. 22 at 2 p.m., ET, entitled “Empowering Nurses for Early Sepsis Recognition.”

Sepsis is a medical emergency that begins outside of the hospital in 79% of cases. In addition, 72% of patients with sepsis had recently used healthcare services or had chronic diseases that required frequent medical care.

Those are key findings from a special report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533e1).

“The treatment of sepsis is a race against time,” CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, said during a media teleconference about the report. “We can protect more people from sepsis by informing patients and their families, treating infections promptly, and acting fast when sepsis does occur.”

Each year, between 1 and 3 million people in the United States are diagnosed with sepsis, a syndrome marked by the body’s overwhelming and life-threatening response to an infection, Dr. Frieden said. Of these, 15%-30% will die from the condition, for which there is no blood test. “Health care providers are on the front lines of both sepsis prevention and early recognition,” he emphasized. “Prevention really is possible.” For example, he continued, if a patient with diabetes visits their regular doctor and is found to have increased blood sugar and a small wound on their foot, “this is a prime opportunity to think about infection and reduce the risk of sepsis. In addition to treating the infection, the clinician can inform the patient and family members about how to care for the wound, how to recognize the signs that the infection may be getting worse, and when to seek additional medical care. If the infection gets worse the patient could be at risk for sepsis. Taking the opportunity to both treat and inform patients could save their life, and helping patients know to ask, ‘Could this be sepsis?’ empowers patients and families and could save lives.”

In an effort to describe the characteristics of patients with sepsis, researchers from the CDC and from New York State conducted a retrospective review of medical records from 246 adults and 79 children with sepsis who were treated at four New York hospitals. They found that sepsis most often occurs in patients older than age 65 years and in infants younger than 1 year of age, and the median hospital length of stay is 10 days. Six key signs and symptoms of sepsis were shivering or feeling cold; pain or discomfort; clammy or sweaty skin; being confused or disoriented; shortness of breath, and having a rapid heartbeat. “People with chronic diseases such as diabetes or weakened immune systems from things like tobacco use are at higher risk of sepsis,” Dr. Frieden said. “But even healthy people can develop sepsis from an infection, especially if it’s not treated properly and promptly.”