User login

Staph aureus prevalent on U.S. freshwater beaches

BOSTON – Almost half of all sand and water samples taken from Midwestern freshwater public beaches tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus isolates during the summertime, but numbers fell dramatically in the fall and spring.

Overall, according to a study of 10 public beaches in Ohio, almost half of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin, 41% were multidrug resistant, and about 7% were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

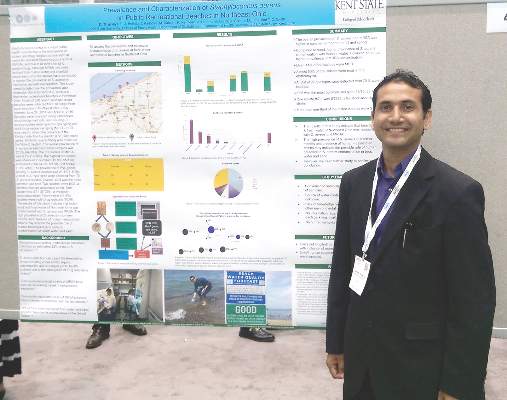

In addition, among the 70 S. aureus isolates, 21.4% had the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene, which encodes for a pore-forming toxin identified as a virulence factor in some strains of staphylococcus. The study results were presented by Dipendra Thapaliya, a research associate at Kent State University, Ohio,, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

In light of these findings, the study’s senior author, Tara Smith, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the university, said in an interview that beachgoers should take reasonable precautions, including washing lake water and sand off young children upon returning home, and making sure to shower at the beach if facilities are available.

“Staphylococcus does well in a salty environment, but it is a fairly hardy organism,” Dr. Smith said, noting that S. aureus has been found in the sand and water of marine beaches, but it has been less well studied in freshwater environments.

Public beaches in Ohio were the source of the samples. Some sampling was done along the shores of Lake Erie, but smaller inland lakes also were tested, In all, 280 sand and water samples were collected in a 3:1 water to sand ratio.

The samples were incubated and plated for culture and subculture according to established methods, and then tested for S. aureus via catalase and coagulase testing, as well as latex agglutination testing. Isolates were then subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the PVL gene and for the mecA genes found in MRSA. Final isolate identification was achieved by staphylococcal protein A (spa) and multilocus sequence typing.

Of the 27 spa types found from 70 isolates, two common strains, t008 and t002, were the most frequently detected. One livestock-associated strain, t571, was also identified.

Though beaches are frequently contaminated with E. coli and other enteric pathogens, the source is often birds or other wildlife, said Dr. Smith. To try to ascertain the source of the staphylococcus in the summer samples, Mr. Thapaliya and his collaborators repeated testing during the winter months and in the spring, before beachgoers had spent time at the waterside.

Those samples from the months when the beaches were empty of people showed much lower levels of S. aureus: In the summer, S. aureus isolates were found in almost half of the samples obtained (55/120, 45.8%). By contrast, only 5 of the 120 fall samples (4.8%) and 4 of the 40 spring samples (10%) were positive for S. aureus.

“The high prevalence of S. aureus in summer months and presence of human-associated strains may indicate the possible role of human presence in S. aureus contamination in beach water and sand. However, we need further study to confirm such a conclusion,” wrote Mr. Thapaliya and his coauthors.

To that end, Dr. Smith said that another, stronger piece of supporting evidence that the S. aureus does come from “the crush of human bathers” would be to identify and match isolates from individuals who frequent the beaches with isolates found in sand and water. Dr. Smith said that she and her team are currently seeking funding to carry out these next steps.

The investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Almost half of all sand and water samples taken from Midwestern freshwater public beaches tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus isolates during the summertime, but numbers fell dramatically in the fall and spring.

Overall, according to a study of 10 public beaches in Ohio, almost half of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin, 41% were multidrug resistant, and about 7% were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

In addition, among the 70 S. aureus isolates, 21.4% had the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene, which encodes for a pore-forming toxin identified as a virulence factor in some strains of staphylococcus. The study results were presented by Dipendra Thapaliya, a research associate at Kent State University, Ohio,, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

In light of these findings, the study’s senior author, Tara Smith, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the university, said in an interview that beachgoers should take reasonable precautions, including washing lake water and sand off young children upon returning home, and making sure to shower at the beach if facilities are available.

“Staphylococcus does well in a salty environment, but it is a fairly hardy organism,” Dr. Smith said, noting that S. aureus has been found in the sand and water of marine beaches, but it has been less well studied in freshwater environments.

Public beaches in Ohio were the source of the samples. Some sampling was done along the shores of Lake Erie, but smaller inland lakes also were tested, In all, 280 sand and water samples were collected in a 3:1 water to sand ratio.

The samples were incubated and plated for culture and subculture according to established methods, and then tested for S. aureus via catalase and coagulase testing, as well as latex agglutination testing. Isolates were then subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the PVL gene and for the mecA genes found in MRSA. Final isolate identification was achieved by staphylococcal protein A (spa) and multilocus sequence typing.

Of the 27 spa types found from 70 isolates, two common strains, t008 and t002, were the most frequently detected. One livestock-associated strain, t571, was also identified.

Though beaches are frequently contaminated with E. coli and other enteric pathogens, the source is often birds or other wildlife, said Dr. Smith. To try to ascertain the source of the staphylococcus in the summer samples, Mr. Thapaliya and his collaborators repeated testing during the winter months and in the spring, before beachgoers had spent time at the waterside.

Those samples from the months when the beaches were empty of people showed much lower levels of S. aureus: In the summer, S. aureus isolates were found in almost half of the samples obtained (55/120, 45.8%). By contrast, only 5 of the 120 fall samples (4.8%) and 4 of the 40 spring samples (10%) were positive for S. aureus.

“The high prevalence of S. aureus in summer months and presence of human-associated strains may indicate the possible role of human presence in S. aureus contamination in beach water and sand. However, we need further study to confirm such a conclusion,” wrote Mr. Thapaliya and his coauthors.

To that end, Dr. Smith said that another, stronger piece of supporting evidence that the S. aureus does come from “the crush of human bathers” would be to identify and match isolates from individuals who frequent the beaches with isolates found in sand and water. Dr. Smith said that she and her team are currently seeking funding to carry out these next steps.

The investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Almost half of all sand and water samples taken from Midwestern freshwater public beaches tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus isolates during the summertime, but numbers fell dramatically in the fall and spring.

Overall, according to a study of 10 public beaches in Ohio, almost half of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin, 41% were multidrug resistant, and about 7% were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

In addition, among the 70 S. aureus isolates, 21.4% had the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene, which encodes for a pore-forming toxin identified as a virulence factor in some strains of staphylococcus. The study results were presented by Dipendra Thapaliya, a research associate at Kent State University, Ohio,, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

In light of these findings, the study’s senior author, Tara Smith, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the university, said in an interview that beachgoers should take reasonable precautions, including washing lake water and sand off young children upon returning home, and making sure to shower at the beach if facilities are available.

“Staphylococcus does well in a salty environment, but it is a fairly hardy organism,” Dr. Smith said, noting that S. aureus has been found in the sand and water of marine beaches, but it has been less well studied in freshwater environments.

Public beaches in Ohio were the source of the samples. Some sampling was done along the shores of Lake Erie, but smaller inland lakes also were tested, In all, 280 sand and water samples were collected in a 3:1 water to sand ratio.

The samples were incubated and plated for culture and subculture according to established methods, and then tested for S. aureus via catalase and coagulase testing, as well as latex agglutination testing. Isolates were then subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the PVL gene and for the mecA genes found in MRSA. Final isolate identification was achieved by staphylococcal protein A (spa) and multilocus sequence typing.

Of the 27 spa types found from 70 isolates, two common strains, t008 and t002, were the most frequently detected. One livestock-associated strain, t571, was also identified.

Though beaches are frequently contaminated with E. coli and other enteric pathogens, the source is often birds or other wildlife, said Dr. Smith. To try to ascertain the source of the staphylococcus in the summer samples, Mr. Thapaliya and his collaborators repeated testing during the winter months and in the spring, before beachgoers had spent time at the waterside.

Those samples from the months when the beaches were empty of people showed much lower levels of S. aureus: In the summer, S. aureus isolates were found in almost half of the samples obtained (55/120, 45.8%). By contrast, only 5 of the 120 fall samples (4.8%) and 4 of the 40 spring samples (10%) were positive for S. aureus.

“The high prevalence of S. aureus in summer months and presence of human-associated strains may indicate the possible role of human presence in S. aureus contamination in beach water and sand. However, we need further study to confirm such a conclusion,” wrote Mr. Thapaliya and his coauthors.

To that end, Dr. Smith said that another, stronger piece of supporting evidence that the S. aureus does come from “the crush of human bathers” would be to identify and match isolates from individuals who frequent the beaches with isolates found in sand and water. Dr. Smith said that she and her team are currently seeking funding to carry out these next steps.

The investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ASM MICROBE 2016

Key clinical point: Almost half of summertime sand and water samples were positive for Staphylococcus aureus.

Major finding: Of 120 summertime samples, 55 (45.8%) were positive for S. aureus.

Data source: Sand and water samples (n = 280) from 10 freshwater beaches in the upper Midwest.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported no disclosures.

Seasonal Variation Not Seen in C difficile Rates

BOSTON – No winter spike in Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) rates was seen among hospitalized patients after testing methodologies and frequency were accounted for, according to a large multinational study.

A total of 180 hospitals in five European countries had wide variation in CDI testing methods and testing density. However, among the hospitals that used a currently recommended toxin-detecting testing algorithm, there was no significant seasonal variation in cases, defined as mean cases per 10,000 patient bed-days per hospital per month (C/PBDs/H/M). The hospitals using toxin-detecting algorithms had summer C/PBDs/H/M rates of 9.6, compared to 8.0 in winter months (P = .27).

These results, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology by Kerrie Davies, clinical scientist at the University of Leeds (England), stand in contrast to some other studies that have shown a wintertime peak in CDI incidence. The data presented help in “understanding the context in which published reported rate data have been generated,” said Ms. Davies, enabling a better understanding both of how samples are tested, and who gets tested.

The study enrolled 180 hospitals – 38 each in France and Italy, 37 each in Germany and the United Kingdom, and 30 in Spain. Institutions reported patient demographics, as well as CDI testing data and patient bed-days for CDI cases, for 1 year.

Current European and U.K. CDI testing algorithms, said Ms. Davies, begin either with testing for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or with nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), and then proceed to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing for C. difficile toxins A and B.

Other algorithms, for example those that begin with toxin testing, are not recommended, said Ms. Davies. Some institutions may diagnose CDI only by toxin detection, GDH testing, or NAAT testing.

For data analysis, Ms. Davies and her collaborators compared CDI-related PBDs and testing density during June, July, and August to data collected in December, January, and February. Testing methods were dichotomized to toxin-detecting CDI testing algorithms (TCTA, using GDH/toxin or NAAT/toxin), or non-TCTA methods, which included all other algorithms or stand-alone testing methods.

Wide variation was seen between countries in testing methodologies. The United Kingdom had the highest rate of TCTA testing at 89%, while Germany had the lowest, at 8%, with 30 of 37 (81%) of participating German hospitals using non–toxin detection methods.

In addition, both testing density and case incidence rates varied between countries. Standardizing test density to mean number of tests per 10,000 PBDs per hospital per month (T/PBDs/H/M), the United Kingdom had the highest density, at 96.0 T/PBDs/H/M, while France had the lowest, at 34.4 T/PBDs/H/M. Overall per-nation case rates ranged from 2.55 C/PBDs/H/M in the United Kingdom to 6.9 C/PBDs/H/M in Spain.

Ms. Davies and her collaborators also analyzed data for all of the hospitals in any country according to testing method. That analysis saw no significant difference in seasonal variation testing rates for TCTA-using hospitals (mean T/PBDs/H/M in summer, 119.2 versus 102.4 in winter, P = .11), and no significant seasonal variation in CDI incidence. However, “the largest variation in CDI rates was seen in those hospitals using toxin-only diagnostic methods,” said Ms. Davies.

By contrast, for hospitals using non-TCTA methods, though testing rates did not change significantly, incidence was significantly higher in winter months, at a mean 13.5 wintertime versus 10.0 summertime C/PBDs/H/M (P = .49).

One country, Italy, stood out for having both higher overall wintertime testing (mean 57.2 summertime versus 78.8 wintertime T/PBDs/H/M, P = .041), and higher incidence (mean 6.6 summertime versus 10.1 wintertime C/PBDs/H/M, P = .017).

“Reported CDI rates only increase in winter if testing rates increase concurrently, or if hospitals use nonrecommended testing methods for diagnosis, especially non–toxin detection methods,” said Ms. Davies.

The study investigators reported receiving financial support from Sanofi Pasteur.

BOSTON – No winter spike in Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) rates was seen among hospitalized patients after testing methodologies and frequency were accounted for, according to a large multinational study.

A total of 180 hospitals in five European countries had wide variation in CDI testing methods and testing density. However, among the hospitals that used a currently recommended toxin-detecting testing algorithm, there was no significant seasonal variation in cases, defined as mean cases per 10,000 patient bed-days per hospital per month (C/PBDs/H/M). The hospitals using toxin-detecting algorithms had summer C/PBDs/H/M rates of 9.6, compared to 8.0 in winter months (P = .27).

These results, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology by Kerrie Davies, clinical scientist at the University of Leeds (England), stand in contrast to some other studies that have shown a wintertime peak in CDI incidence. The data presented help in “understanding the context in which published reported rate data have been generated,” said Ms. Davies, enabling a better understanding both of how samples are tested, and who gets tested.

The study enrolled 180 hospitals – 38 each in France and Italy, 37 each in Germany and the United Kingdom, and 30 in Spain. Institutions reported patient demographics, as well as CDI testing data and patient bed-days for CDI cases, for 1 year.

Current European and U.K. CDI testing algorithms, said Ms. Davies, begin either with testing for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or with nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), and then proceed to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing for C. difficile toxins A and B.

Other algorithms, for example those that begin with toxin testing, are not recommended, said Ms. Davies. Some institutions may diagnose CDI only by toxin detection, GDH testing, or NAAT testing.

For data analysis, Ms. Davies and her collaborators compared CDI-related PBDs and testing density during June, July, and August to data collected in December, January, and February. Testing methods were dichotomized to toxin-detecting CDI testing algorithms (TCTA, using GDH/toxin or NAAT/toxin), or non-TCTA methods, which included all other algorithms or stand-alone testing methods.

Wide variation was seen between countries in testing methodologies. The United Kingdom had the highest rate of TCTA testing at 89%, while Germany had the lowest, at 8%, with 30 of 37 (81%) of participating German hospitals using non–toxin detection methods.

In addition, both testing density and case incidence rates varied between countries. Standardizing test density to mean number of tests per 10,000 PBDs per hospital per month (T/PBDs/H/M), the United Kingdom had the highest density, at 96.0 T/PBDs/H/M, while France had the lowest, at 34.4 T/PBDs/H/M. Overall per-nation case rates ranged from 2.55 C/PBDs/H/M in the United Kingdom to 6.9 C/PBDs/H/M in Spain.

Ms. Davies and her collaborators also analyzed data for all of the hospitals in any country according to testing method. That analysis saw no significant difference in seasonal variation testing rates for TCTA-using hospitals (mean T/PBDs/H/M in summer, 119.2 versus 102.4 in winter, P = .11), and no significant seasonal variation in CDI incidence. However, “the largest variation in CDI rates was seen in those hospitals using toxin-only diagnostic methods,” said Ms. Davies.

By contrast, for hospitals using non-TCTA methods, though testing rates did not change significantly, incidence was significantly higher in winter months, at a mean 13.5 wintertime versus 10.0 summertime C/PBDs/H/M (P = .49).

One country, Italy, stood out for having both higher overall wintertime testing (mean 57.2 summertime versus 78.8 wintertime T/PBDs/H/M, P = .041), and higher incidence (mean 6.6 summertime versus 10.1 wintertime C/PBDs/H/M, P = .017).

“Reported CDI rates only increase in winter if testing rates increase concurrently, or if hospitals use nonrecommended testing methods for diagnosis, especially non–toxin detection methods,” said Ms. Davies.

The study investigators reported receiving financial support from Sanofi Pasteur.

BOSTON – No winter spike in Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) rates was seen among hospitalized patients after testing methodologies and frequency were accounted for, according to a large multinational study.

A total of 180 hospitals in five European countries had wide variation in CDI testing methods and testing density. However, among the hospitals that used a currently recommended toxin-detecting testing algorithm, there was no significant seasonal variation in cases, defined as mean cases per 10,000 patient bed-days per hospital per month (C/PBDs/H/M). The hospitals using toxin-detecting algorithms had summer C/PBDs/H/M rates of 9.6, compared to 8.0 in winter months (P = .27).

These results, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology by Kerrie Davies, clinical scientist at the University of Leeds (England), stand in contrast to some other studies that have shown a wintertime peak in CDI incidence. The data presented help in “understanding the context in which published reported rate data have been generated,” said Ms. Davies, enabling a better understanding both of how samples are tested, and who gets tested.

The study enrolled 180 hospitals – 38 each in France and Italy, 37 each in Germany and the United Kingdom, and 30 in Spain. Institutions reported patient demographics, as well as CDI testing data and patient bed-days for CDI cases, for 1 year.

Current European and U.K. CDI testing algorithms, said Ms. Davies, begin either with testing for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or with nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), and then proceed to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing for C. difficile toxins A and B.

Other algorithms, for example those that begin with toxin testing, are not recommended, said Ms. Davies. Some institutions may diagnose CDI only by toxin detection, GDH testing, or NAAT testing.

For data analysis, Ms. Davies and her collaborators compared CDI-related PBDs and testing density during June, July, and August to data collected in December, January, and February. Testing methods were dichotomized to toxin-detecting CDI testing algorithms (TCTA, using GDH/toxin or NAAT/toxin), or non-TCTA methods, which included all other algorithms or stand-alone testing methods.

Wide variation was seen between countries in testing methodologies. The United Kingdom had the highest rate of TCTA testing at 89%, while Germany had the lowest, at 8%, with 30 of 37 (81%) of participating German hospitals using non–toxin detection methods.

In addition, both testing density and case incidence rates varied between countries. Standardizing test density to mean number of tests per 10,000 PBDs per hospital per month (T/PBDs/H/M), the United Kingdom had the highest density, at 96.0 T/PBDs/H/M, while France had the lowest, at 34.4 T/PBDs/H/M. Overall per-nation case rates ranged from 2.55 C/PBDs/H/M in the United Kingdom to 6.9 C/PBDs/H/M in Spain.

Ms. Davies and her collaborators also analyzed data for all of the hospitals in any country according to testing method. That analysis saw no significant difference in seasonal variation testing rates for TCTA-using hospitals (mean T/PBDs/H/M in summer, 119.2 versus 102.4 in winter, P = .11), and no significant seasonal variation in CDI incidence. However, “the largest variation in CDI rates was seen in those hospitals using toxin-only diagnostic methods,” said Ms. Davies.

By contrast, for hospitals using non-TCTA methods, though testing rates did not change significantly, incidence was significantly higher in winter months, at a mean 13.5 wintertime versus 10.0 summertime C/PBDs/H/M (P = .49).

One country, Italy, stood out for having both higher overall wintertime testing (mean 57.2 summertime versus 78.8 wintertime T/PBDs/H/M, P = .041), and higher incidence (mean 6.6 summertime versus 10.1 wintertime C/PBDs/H/M, P = .017).

“Reported CDI rates only increase in winter if testing rates increase concurrently, or if hospitals use nonrecommended testing methods for diagnosis, especially non–toxin detection methods,” said Ms. Davies.

The study investigators reported receiving financial support from Sanofi Pasteur.

AT ASM MICROBE 2016

Seasonal variation not seen in C. difficile rates

BOSTON – No winter spike in Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) rates was seen among hospitalized patients after testing methodologies and frequency were accounted for, according to a large multinational study.

A total of 180 hospitals in five European countries had wide variation in CDI testing methods and testing density. However, among the hospitals that used a currently recommended toxin-detecting testing algorithm, there was no significant seasonal variation in cases, defined as mean cases per 10,000 patient bed-days per hospital per month (C/PBDs/H/M). The hospitals using toxin-detecting algorithms had summer C/PBDs/H/M rates of 9.6, compared to 8.0 in winter months (P = .27).

These results, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology by Kerrie Davies, clinical scientist at the University of Leeds (England), stand in contrast to some other studies that have shown a wintertime peak in CDI incidence. The data presented help in “understanding the context in which published reported rate data have been generated,” said Ms. Davies, enabling a better understanding both of how samples are tested, and who gets tested.

The study enrolled 180 hospitals – 38 each in France and Italy, 37 each in Germany and the United Kingdom, and 30 in Spain. Institutions reported patient demographics, as well as CDI testing data and patient bed-days for CDI cases, for 1 year.

Current European and U.K. CDI testing algorithms, said Ms. Davies, begin either with testing for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or with nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), and then proceed to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing for C. difficile toxins A and B.

Other algorithms, for example those that begin with toxin testing, are not recommended, said Ms. Davies. Some institutions may diagnose CDI only by toxin detection, GDH testing, or NAAT testing.

For data analysis, Ms. Davies and her collaborators compared CDI-related PBDs and testing density during June, July, and August to data collected in December, January, and February. Testing methods were dichotomized to toxin-detecting CDI testing algorithms (TCTA, using GDH/toxin or NAAT/toxin), or non-TCTA methods, which included all other algorithms or stand-alone testing methods.

Wide variation was seen between countries in testing methodologies. The United Kingdom had the highest rate of TCTA testing at 89%, while Germany had the lowest, at 8%, with 30 of 37 (81%) of participating German hospitals using non–toxin detection methods.

In addition, both testing density and case incidence rates varied between countries. Standardizing test density to mean number of tests per 10,000 PBDs per hospital per month (T/PBDs/H/M), the United Kingdom had the highest density, at 96.0 T/PBDs/H/M, while France had the lowest, at 34.4 T/PBDs/H/M. Overall per-nation case rates ranged from 2.55 C/PBDs/H/M in the United Kingdom to 6.9 C/PBDs/H/M in Spain.

Ms. Davies and her collaborators also analyzed data for all of the hospitals in any country according to testing method. That analysis saw no significant difference in seasonal variation testing rates for TCTA-using hospitals (mean T/PBDs/H/M in summer, 119.2 versus 102.4 in winter, P = .11), and no significant seasonal variation in CDI incidence. However, “the largest variation in CDI rates was seen in those hospitals using toxin-only diagnostic methods,” said Ms. Davies.

By contrast, for hospitals using non-TCTA methods, though testing rates did not change significantly, incidence was significantly higher in winter months, at a mean 13.5 wintertime versus 10.0 summertime C/PBDs/H/M (P = .49).

One country, Italy, stood out for having both higher overall wintertime testing (mean 57.2 summertime versus 78.8 wintertime T/PBDs/H/M, P = .041), and higher incidence (mean 6.6 summertime versus 10.1 wintertime C/PBDs/H/M, P = .017).

“Reported CDI rates only increase in winter if testing rates increase concurrently, or if hospitals use nonrecommended testing methods for diagnosis, especially non–toxin detection methods,” said Ms. Davies.

The study investigators reported receiving financial support from Sanofi Pasteur.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – No winter spike in Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) rates was seen among hospitalized patients after testing methodologies and frequency were accounted for, according to a large multinational study.

A total of 180 hospitals in five European countries had wide variation in CDI testing methods and testing density. However, among the hospitals that used a currently recommended toxin-detecting testing algorithm, there was no significant seasonal variation in cases, defined as mean cases per 10,000 patient bed-days per hospital per month (C/PBDs/H/M). The hospitals using toxin-detecting algorithms had summer C/PBDs/H/M rates of 9.6, compared to 8.0 in winter months (P = .27).

These results, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology by Kerrie Davies, clinical scientist at the University of Leeds (England), stand in contrast to some other studies that have shown a wintertime peak in CDI incidence. The data presented help in “understanding the context in which published reported rate data have been generated,” said Ms. Davies, enabling a better understanding both of how samples are tested, and who gets tested.

The study enrolled 180 hospitals – 38 each in France and Italy, 37 each in Germany and the United Kingdom, and 30 in Spain. Institutions reported patient demographics, as well as CDI testing data and patient bed-days for CDI cases, for 1 year.

Current European and U.K. CDI testing algorithms, said Ms. Davies, begin either with testing for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or with nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), and then proceed to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing for C. difficile toxins A and B.

Other algorithms, for example those that begin with toxin testing, are not recommended, said Ms. Davies. Some institutions may diagnose CDI only by toxin detection, GDH testing, or NAAT testing.

For data analysis, Ms. Davies and her collaborators compared CDI-related PBDs and testing density during June, July, and August to data collected in December, January, and February. Testing methods were dichotomized to toxin-detecting CDI testing algorithms (TCTA, using GDH/toxin or NAAT/toxin), or non-TCTA methods, which included all other algorithms or stand-alone testing methods.

Wide variation was seen between countries in testing methodologies. The United Kingdom had the highest rate of TCTA testing at 89%, while Germany had the lowest, at 8%, with 30 of 37 (81%) of participating German hospitals using non–toxin detection methods.

In addition, both testing density and case incidence rates varied between countries. Standardizing test density to mean number of tests per 10,000 PBDs per hospital per month (T/PBDs/H/M), the United Kingdom had the highest density, at 96.0 T/PBDs/H/M, while France had the lowest, at 34.4 T/PBDs/H/M. Overall per-nation case rates ranged from 2.55 C/PBDs/H/M in the United Kingdom to 6.9 C/PBDs/H/M in Spain.

Ms. Davies and her collaborators also analyzed data for all of the hospitals in any country according to testing method. That analysis saw no significant difference in seasonal variation testing rates for TCTA-using hospitals (mean T/PBDs/H/M in summer, 119.2 versus 102.4 in winter, P = .11), and no significant seasonal variation in CDI incidence. However, “the largest variation in CDI rates was seen in those hospitals using toxin-only diagnostic methods,” said Ms. Davies.

By contrast, for hospitals using non-TCTA methods, though testing rates did not change significantly, incidence was significantly higher in winter months, at a mean 13.5 wintertime versus 10.0 summertime C/PBDs/H/M (P = .49).

One country, Italy, stood out for having both higher overall wintertime testing (mean 57.2 summertime versus 78.8 wintertime T/PBDs/H/M, P = .041), and higher incidence (mean 6.6 summertime versus 10.1 wintertime C/PBDs/H/M, P = .017).

“Reported CDI rates only increase in winter if testing rates increase concurrently, or if hospitals use nonrecommended testing methods for diagnosis, especially non–toxin detection methods,” said Ms. Davies.

The study investigators reported receiving financial support from Sanofi Pasteur.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – No winter spike in Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) rates was seen among hospitalized patients after testing methodologies and frequency were accounted for, according to a large multinational study.

A total of 180 hospitals in five European countries had wide variation in CDI testing methods and testing density. However, among the hospitals that used a currently recommended toxin-detecting testing algorithm, there was no significant seasonal variation in cases, defined as mean cases per 10,000 patient bed-days per hospital per month (C/PBDs/H/M). The hospitals using toxin-detecting algorithms had summer C/PBDs/H/M rates of 9.6, compared to 8.0 in winter months (P = .27).

These results, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology by Kerrie Davies, clinical scientist at the University of Leeds (England), stand in contrast to some other studies that have shown a wintertime peak in CDI incidence. The data presented help in “understanding the context in which published reported rate data have been generated,” said Ms. Davies, enabling a better understanding both of how samples are tested, and who gets tested.

The study enrolled 180 hospitals – 38 each in France and Italy, 37 each in Germany and the United Kingdom, and 30 in Spain. Institutions reported patient demographics, as well as CDI testing data and patient bed-days for CDI cases, for 1 year.

Current European and U.K. CDI testing algorithms, said Ms. Davies, begin either with testing for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or with nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), and then proceed to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing for C. difficile toxins A and B.

Other algorithms, for example those that begin with toxin testing, are not recommended, said Ms. Davies. Some institutions may diagnose CDI only by toxin detection, GDH testing, or NAAT testing.

For data analysis, Ms. Davies and her collaborators compared CDI-related PBDs and testing density during June, July, and August to data collected in December, January, and February. Testing methods were dichotomized to toxin-detecting CDI testing algorithms (TCTA, using GDH/toxin or NAAT/toxin), or non-TCTA methods, which included all other algorithms or stand-alone testing methods.

Wide variation was seen between countries in testing methodologies. The United Kingdom had the highest rate of TCTA testing at 89%, while Germany had the lowest, at 8%, with 30 of 37 (81%) of participating German hospitals using non–toxin detection methods.

In addition, both testing density and case incidence rates varied between countries. Standardizing test density to mean number of tests per 10,000 PBDs per hospital per month (T/PBDs/H/M), the United Kingdom had the highest density, at 96.0 T/PBDs/H/M, while France had the lowest, at 34.4 T/PBDs/H/M. Overall per-nation case rates ranged from 2.55 C/PBDs/H/M in the United Kingdom to 6.9 C/PBDs/H/M in Spain.

Ms. Davies and her collaborators also analyzed data for all of the hospitals in any country according to testing method. That analysis saw no significant difference in seasonal variation testing rates for TCTA-using hospitals (mean T/PBDs/H/M in summer, 119.2 versus 102.4 in winter, P = .11), and no significant seasonal variation in CDI incidence. However, “the largest variation in CDI rates was seen in those hospitals using toxin-only diagnostic methods,” said Ms. Davies.

By contrast, for hospitals using non-TCTA methods, though testing rates did not change significantly, incidence was significantly higher in winter months, at a mean 13.5 wintertime versus 10.0 summertime C/PBDs/H/M (P = .49).

One country, Italy, stood out for having both higher overall wintertime testing (mean 57.2 summertime versus 78.8 wintertime T/PBDs/H/M, P = .041), and higher incidence (mean 6.6 summertime versus 10.1 wintertime C/PBDs/H/M, P = .017).

“Reported CDI rates only increase in winter if testing rates increase concurrently, or if hospitals use nonrecommended testing methods for diagnosis, especially non–toxin detection methods,” said Ms. Davies.

The study investigators reported receiving financial support from Sanofi Pasteur.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ASM MICROBE 2016

Key clinical point: After researchers accounted for testing frequency and methods, Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) rates were not higher in the winter months.

Major finding: In five European countries, hospitals that used direct toxin-detecting algorithms to test for CDI had no seasonal variation in CDI incidence (mean cases/patient bed-days/hospital/month in summer, 9.6; in winter, 8.0; P = .27).

Data source: Demographic and testing data collection from 180 hospitals in five European countries to ascertain CDI testing methods, rates, cases, and patient bed-days per month.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported financial support from Sanofi Pasteur.

Consider Fusobacterium in culture-negative pharyngitis

BOSTON – An underappreciated cause of bacterial pharyngitis had a similar clinical presentation to group A Streptococcus (GAS), although prevalence was low in the population of 300 pediatric patients in a single-site study.

The 10 patients (3.3%) who had positive cultures for Fusobacterium necrophorum were about as likely as those with GAS to have fever, sore throat, exudate, and absence of cough. GAS cultures were positive in 57 (19%) of the patients.

F. necrophorum is a common cause of serious bacterial pharyngitis, especially in adolescents and young adults. The gram-negative species, an obligate anaerobe, is a cause of Lemierre’s syndrome, and “has recently been identified to be an important pathogen of bacterial pharyngitis with higher prevalence than group A Streptococcus (GAS) in adolescents and young adults,” wrote Tam Van, Ph.D., and her colleagues in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

To examine the prevalence and disease characteristics of F. necrophorum in the emergency department patient population at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, Dr Van, a medical microbiology fellow at the hospital, and her colleagues enrolled 300 patients with pharyngitis aged 1-20 years (mean, 7.8 years).

All patients’ throats were swabbed, and investigators conducted a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) for group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and cultured samples for Streptococcus on a blood agar plate, according to usual care; samples also were cultured anaerobically and tested via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for F. necrophorum.

A total of 67 patients had positive culture or PCR results for both species. Fifteen of the RADT tests were positive, while 57 cultures returned positive for GAS growth. Nine of the 10 positive F. necrophorum PCR tests correlated with positive culture results for that species.

Luckily, said Dr. Van, penicillin is an effective treatment for F. necrophorum, although it’s a gram-negative bacterium, so if a patient is coinfected with F. necrophorum and GAS, or treated for GAS empirically, then standard of care treatment should be effective, she said. However, since the species is associated with serious complications such as Lemierre’s disease, close follow-up and a low threshold for aggressive treatment are warranted if F. necrophorum is suspected or identified.

The relatively low positive culture rate of 3.3% for F. necrophorum in the study population was a bit surprising, Dr. Van said in an interview but was perhaps accounted for by the relatively young age of the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles patients. “Previous reports looked at adolescents and young adults,” wrote Dr. Van and her colleagues, while two-thirds of the patients in their study were under the age of 10 years. “This may contribute to the difference in prevalence.”

“Although rare, recovery of F. necrophorum correlated with true signs and symptoms of bacterial pharyngitis,” wrote Dr. Van and her colleagues. Serious pharyngitis with a negative rapid test and culture for group A Streptococcus should prompt clinical suspicion for F. necrophorum, especially in older adolescents and young adults, said Dr. Tam.

Dr. Tam and her coauthors reported no outside sources of funding and reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – An underappreciated cause of bacterial pharyngitis had a similar clinical presentation to group A Streptococcus (GAS), although prevalence was low in the population of 300 pediatric patients in a single-site study.

The 10 patients (3.3%) who had positive cultures for Fusobacterium necrophorum were about as likely as those with GAS to have fever, sore throat, exudate, and absence of cough. GAS cultures were positive in 57 (19%) of the patients.

F. necrophorum is a common cause of serious bacterial pharyngitis, especially in adolescents and young adults. The gram-negative species, an obligate anaerobe, is a cause of Lemierre’s syndrome, and “has recently been identified to be an important pathogen of bacterial pharyngitis with higher prevalence than group A Streptococcus (GAS) in adolescents and young adults,” wrote Tam Van, Ph.D., and her colleagues in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

To examine the prevalence and disease characteristics of F. necrophorum in the emergency department patient population at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, Dr Van, a medical microbiology fellow at the hospital, and her colleagues enrolled 300 patients with pharyngitis aged 1-20 years (mean, 7.8 years).

All patients’ throats were swabbed, and investigators conducted a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) for group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and cultured samples for Streptococcus on a blood agar plate, according to usual care; samples also were cultured anaerobically and tested via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for F. necrophorum.

A total of 67 patients had positive culture or PCR results for both species. Fifteen of the RADT tests were positive, while 57 cultures returned positive for GAS growth. Nine of the 10 positive F. necrophorum PCR tests correlated with positive culture results for that species.

Luckily, said Dr. Van, penicillin is an effective treatment for F. necrophorum, although it’s a gram-negative bacterium, so if a patient is coinfected with F. necrophorum and GAS, or treated for GAS empirically, then standard of care treatment should be effective, she said. However, since the species is associated with serious complications such as Lemierre’s disease, close follow-up and a low threshold for aggressive treatment are warranted if F. necrophorum is suspected or identified.

The relatively low positive culture rate of 3.3% for F. necrophorum in the study population was a bit surprising, Dr. Van said in an interview but was perhaps accounted for by the relatively young age of the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles patients. “Previous reports looked at adolescents and young adults,” wrote Dr. Van and her colleagues, while two-thirds of the patients in their study were under the age of 10 years. “This may contribute to the difference in prevalence.”

“Although rare, recovery of F. necrophorum correlated with true signs and symptoms of bacterial pharyngitis,” wrote Dr. Van and her colleagues. Serious pharyngitis with a negative rapid test and culture for group A Streptococcus should prompt clinical suspicion for F. necrophorum, especially in older adolescents and young adults, said Dr. Tam.

Dr. Tam and her coauthors reported no outside sources of funding and reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – An underappreciated cause of bacterial pharyngitis had a similar clinical presentation to group A Streptococcus (GAS), although prevalence was low in the population of 300 pediatric patients in a single-site study.

The 10 patients (3.3%) who had positive cultures for Fusobacterium necrophorum were about as likely as those with GAS to have fever, sore throat, exudate, and absence of cough. GAS cultures were positive in 57 (19%) of the patients.

F. necrophorum is a common cause of serious bacterial pharyngitis, especially in adolescents and young adults. The gram-negative species, an obligate anaerobe, is a cause of Lemierre’s syndrome, and “has recently been identified to be an important pathogen of bacterial pharyngitis with higher prevalence than group A Streptococcus (GAS) in adolescents and young adults,” wrote Tam Van, Ph.D., and her colleagues in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

To examine the prevalence and disease characteristics of F. necrophorum in the emergency department patient population at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, Dr Van, a medical microbiology fellow at the hospital, and her colleagues enrolled 300 patients with pharyngitis aged 1-20 years (mean, 7.8 years).

All patients’ throats were swabbed, and investigators conducted a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) for group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and cultured samples for Streptococcus on a blood agar plate, according to usual care; samples also were cultured anaerobically and tested via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for F. necrophorum.

A total of 67 patients had positive culture or PCR results for both species. Fifteen of the RADT tests were positive, while 57 cultures returned positive for GAS growth. Nine of the 10 positive F. necrophorum PCR tests correlated with positive culture results for that species.

Luckily, said Dr. Van, penicillin is an effective treatment for F. necrophorum, although it’s a gram-negative bacterium, so if a patient is coinfected with F. necrophorum and GAS, or treated for GAS empirically, then standard of care treatment should be effective, she said. However, since the species is associated with serious complications such as Lemierre’s disease, close follow-up and a low threshold for aggressive treatment are warranted if F. necrophorum is suspected or identified.

The relatively low positive culture rate of 3.3% for F. necrophorum in the study population was a bit surprising, Dr. Van said in an interview but was perhaps accounted for by the relatively young age of the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles patients. “Previous reports looked at adolescents and young adults,” wrote Dr. Van and her colleagues, while two-thirds of the patients in their study were under the age of 10 years. “This may contribute to the difference in prevalence.”

“Although rare, recovery of F. necrophorum correlated with true signs and symptoms of bacterial pharyngitis,” wrote Dr. Van and her colleagues. Serious pharyngitis with a negative rapid test and culture for group A Streptococcus should prompt clinical suspicion for F. necrophorum, especially in older adolescents and young adults, said Dr. Tam.

Dr. Tam and her coauthors reported no outside sources of funding and reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ASM MICROBE 2016

Key clinical point: Fusobacterium necrophorum has a similar presentation to group A Streptococcus (GAS) pharyngitis.

Major finding: Pediatric patients with F. necrophorum pharyngitis were about as likely as those with GAS to have fever, exudates, adenopathy, and no cough.

Data source: 300 pediatric emergency department patients with pharyngitis who received antigen testing, cultures, and PCR to identify both causative agents.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported no disclosures.

Hospital-acquired respiratory viruses cause significant morbidity, mortality

BOSTON – Hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections may be a significant and underappreciated cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients.

According to a multisite, retrospective chart review of 44 patients with hospital-acquired respiratory viral illnesses (HA-RVIs), 17 patients (39%) died in-hospital. Further, of the 27 who survived, 18 (66.6%) were discharged to an advanced care setting rather than to home, though just 11/44 (25%) had been living in an advanced care setting before admission.

For the hospitalizations complicated by HA-RVI, the average length of stay was 30.4 days, with a positive respiratory virus panel (RVP) result occurring at a mean 18 days after admission.

“HA-RVIs are an underappreciated event and appear to target the sickest patients in the hospital,” said coauthor Dr. Matthew Sims, director of infectious diseases research at Beaumont Hospital, Rochester, Mich., at a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology.

First author Dr. Adam K. Skrzynski, also of Beaumont Health, and his coauthors performed the analysis of 4,065 patients with a positive RVP result during hospitalization at a regional hospital system in the September 2011-May 2015 study period; the 1.1% of patients with positive results who formed the study cohort had to have symptoms of a respiratory infection occurring after more than 5 days of hospitalization. Mortality data were collected for the first 33 days of hospitalization.

Positive RVP results for those included in the study came primarily from nasopharyngeal swab (n = 32), with the remainder from bronchoalveolar lavage (n = 11) and sputum (n = 1). Most patients were female (29/44, 66%), and elderly, with an average age of 73.8 years. In an interview, Dr. Sims said that many patients were smokers, and that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obesity were common comorbidities.

The prognosis was particularly grim for the 12 patients (27.3%) who were admitted to the ICU: 10 (83.3%) died after an average 9.6 days in the ICU. Advanced interventions did not seem to make a difference, either. “Intubation didn’t help these patients,” said Dr. Sims. Nine patients (20.5%) were intubated within 7 days of their positive RVP results. Intubation lasted an average 7.6 days, and all nine of these patients died.

The RVP came into use in 2011 and made it possible to identify whether a respiratory virus was causing symptoms – and which virus was the culprit – said Dr. Sims. For the studied population, 13 of 44 patients had influenza; 11 of those had influenza A and 2 had influenza B. The next most common pathogen was parainfluenza, with 10 positive RVP results.

Dr. Sims said he and his coinvestigators were surprised to find that, although influenza A was the most common pathogen, only 18.8% of the patients with influenza A died during the study period. “While it is possible that the high frequency of influenza infection in our study may be due to poor vaccine-strain matching for the years in question, the lower mortality rate seen in influenza A infection may be due to our hospital’s mandatory influenza vaccination policy and subsequent protection against mortality,” Dr. Skrzynski and his coauthors wrote.

There were seasonal trends in mortality, with 70.6% of mortality occurring in the spring (April-June) and an additional 23.3% happening in the winter (January-March). Parainfluenza infection peaked in the spring, and influenza peaked in the winter months.

Dr. Sims said the study underlines the importance of encouraging ill hospital staff members to stay home, and family members with respiratory symptoms should not be visiting fragile patients. Dr. Skrzynski and his coauthors also wrote that “immunization of healthcare personnel against influenza should be mandatory.”

Still to be answered, said Dr. Sims, is the association between comorbidities and the potentially lethal effects of HA-RVIs. They are currently performing a matched case-control study to tease out these relationships.

Dr. Skrzynski reported no outside funding source, and the study authors had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections may be a significant and underappreciated cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients.

According to a multisite, retrospective chart review of 44 patients with hospital-acquired respiratory viral illnesses (HA-RVIs), 17 patients (39%) died in-hospital. Further, of the 27 who survived, 18 (66.6%) were discharged to an advanced care setting rather than to home, though just 11/44 (25%) had been living in an advanced care setting before admission.

For the hospitalizations complicated by HA-RVI, the average length of stay was 30.4 days, with a positive respiratory virus panel (RVP) result occurring at a mean 18 days after admission.

“HA-RVIs are an underappreciated event and appear to target the sickest patients in the hospital,” said coauthor Dr. Matthew Sims, director of infectious diseases research at Beaumont Hospital, Rochester, Mich., at a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology.

First author Dr. Adam K. Skrzynski, also of Beaumont Health, and his coauthors performed the analysis of 4,065 patients with a positive RVP result during hospitalization at a regional hospital system in the September 2011-May 2015 study period; the 1.1% of patients with positive results who formed the study cohort had to have symptoms of a respiratory infection occurring after more than 5 days of hospitalization. Mortality data were collected for the first 33 days of hospitalization.

Positive RVP results for those included in the study came primarily from nasopharyngeal swab (n = 32), with the remainder from bronchoalveolar lavage (n = 11) and sputum (n = 1). Most patients were female (29/44, 66%), and elderly, with an average age of 73.8 years. In an interview, Dr. Sims said that many patients were smokers, and that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obesity were common comorbidities.

The prognosis was particularly grim for the 12 patients (27.3%) who were admitted to the ICU: 10 (83.3%) died after an average 9.6 days in the ICU. Advanced interventions did not seem to make a difference, either. “Intubation didn’t help these patients,” said Dr. Sims. Nine patients (20.5%) were intubated within 7 days of their positive RVP results. Intubation lasted an average 7.6 days, and all nine of these patients died.

The RVP came into use in 2011 and made it possible to identify whether a respiratory virus was causing symptoms – and which virus was the culprit – said Dr. Sims. For the studied population, 13 of 44 patients had influenza; 11 of those had influenza A and 2 had influenza B. The next most common pathogen was parainfluenza, with 10 positive RVP results.

Dr. Sims said he and his coinvestigators were surprised to find that, although influenza A was the most common pathogen, only 18.8% of the patients with influenza A died during the study period. “While it is possible that the high frequency of influenza infection in our study may be due to poor vaccine-strain matching for the years in question, the lower mortality rate seen in influenza A infection may be due to our hospital’s mandatory influenza vaccination policy and subsequent protection against mortality,” Dr. Skrzynski and his coauthors wrote.

There were seasonal trends in mortality, with 70.6% of mortality occurring in the spring (April-June) and an additional 23.3% happening in the winter (January-March). Parainfluenza infection peaked in the spring, and influenza peaked in the winter months.

Dr. Sims said the study underlines the importance of encouraging ill hospital staff members to stay home, and family members with respiratory symptoms should not be visiting fragile patients. Dr. Skrzynski and his coauthors also wrote that “immunization of healthcare personnel against influenza should be mandatory.”

Still to be answered, said Dr. Sims, is the association between comorbidities and the potentially lethal effects of HA-RVIs. They are currently performing a matched case-control study to tease out these relationships.

Dr. Skrzynski reported no outside funding source, and the study authors had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections may be a significant and underappreciated cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients.

According to a multisite, retrospective chart review of 44 patients with hospital-acquired respiratory viral illnesses (HA-RVIs), 17 patients (39%) died in-hospital. Further, of the 27 who survived, 18 (66.6%) were discharged to an advanced care setting rather than to home, though just 11/44 (25%) had been living in an advanced care setting before admission.

For the hospitalizations complicated by HA-RVI, the average length of stay was 30.4 days, with a positive respiratory virus panel (RVP) result occurring at a mean 18 days after admission.

“HA-RVIs are an underappreciated event and appear to target the sickest patients in the hospital,” said coauthor Dr. Matthew Sims, director of infectious diseases research at Beaumont Hospital, Rochester, Mich., at a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology.

First author Dr. Adam K. Skrzynski, also of Beaumont Health, and his coauthors performed the analysis of 4,065 patients with a positive RVP result during hospitalization at a regional hospital system in the September 2011-May 2015 study period; the 1.1% of patients with positive results who formed the study cohort had to have symptoms of a respiratory infection occurring after more than 5 days of hospitalization. Mortality data were collected for the first 33 days of hospitalization.

Positive RVP results for those included in the study came primarily from nasopharyngeal swab (n = 32), with the remainder from bronchoalveolar lavage (n = 11) and sputum (n = 1). Most patients were female (29/44, 66%), and elderly, with an average age of 73.8 years. In an interview, Dr. Sims said that many patients were smokers, and that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obesity were common comorbidities.

The prognosis was particularly grim for the 12 patients (27.3%) who were admitted to the ICU: 10 (83.3%) died after an average 9.6 days in the ICU. Advanced interventions did not seem to make a difference, either. “Intubation didn’t help these patients,” said Dr. Sims. Nine patients (20.5%) were intubated within 7 days of their positive RVP results. Intubation lasted an average 7.6 days, and all nine of these patients died.

The RVP came into use in 2011 and made it possible to identify whether a respiratory virus was causing symptoms – and which virus was the culprit – said Dr. Sims. For the studied population, 13 of 44 patients had influenza; 11 of those had influenza A and 2 had influenza B. The next most common pathogen was parainfluenza, with 10 positive RVP results.

Dr. Sims said he and his coinvestigators were surprised to find that, although influenza A was the most common pathogen, only 18.8% of the patients with influenza A died during the study period. “While it is possible that the high frequency of influenza infection in our study may be due to poor vaccine-strain matching for the years in question, the lower mortality rate seen in influenza A infection may be due to our hospital’s mandatory influenza vaccination policy and subsequent protection against mortality,” Dr. Skrzynski and his coauthors wrote.

There were seasonal trends in mortality, with 70.6% of mortality occurring in the spring (April-June) and an additional 23.3% happening in the winter (January-March). Parainfluenza infection peaked in the spring, and influenza peaked in the winter months.

Dr. Sims said the study underlines the importance of encouraging ill hospital staff members to stay home, and family members with respiratory symptoms should not be visiting fragile patients. Dr. Skrzynski and his coauthors also wrote that “immunization of healthcare personnel against influenza should be mandatory.”

Still to be answered, said Dr. Sims, is the association between comorbidities and the potentially lethal effects of HA-RVIs. They are currently performing a matched case-control study to tease out these relationships.

Dr. Skrzynski reported no outside funding source, and the study authors had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ASM MICROBE 2016

Key clinical point: Hospital-acquired respiratory viral illnesses had a 39% mortality rate.

Major finding: Of 44 symptomatic patients with positive respiratory virus panel screens, 17 died and 2/3 of the survivors went to advanced care settings on discharge.

Data source: Retrospective multisite chart review of 44 patients with HA-RVIs and positive RVP screens.

Disclosures: No external funding source was reported, and the study authors had no disclosures.