User login

Infested with worms, but are they really there?

CASE Detoxification and preoccupation with parasites

Mr. H, age 51, has an extensive history of alcohol and methamphetamine use. He presents to the emergency department (ED) requesting inpatient detoxification. He says he had been drinking alcohol but is unable to say how much. His blood ethanol level is 61 mg/dL (unintoxicated level: <50 mg/dL), and a urine drug screen is positive for methamphetamine; Mr. H also admits to using fentanyl. The ED team treats Mr. H’s electrolyte abnormalities, initiates thiamine supplementation, and transfers him to a unit for inpatient withdrawal management.

On the detoxification unit, Mr. H receives a total of 1,950 mg of phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal and stabilizes on a buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance dose of 8 mg/2 mg twice daily for methamphetamine and fentanyl use. Though he was not taking any psychiatric medications prior to his arrival at the ED, Mr. H agrees to restart quetiapine

During Mr. H’s 3-day detoxification, the psychiatry team evaluates him. Mr. H says he believes he is infested with worms. He describes a prior sensation of “meth mites,” or the feeling of bugs crawling under his skin, while using methamphetamines. However, Mr. H says his current infestation feels distinctively different, and he had continued to experience these

The psychiatry team expresses concern over his preoccupation with infestations, disheveled appearance, poor hygiene, and healed scars from excoriation. Mr. H also reports poor sleep and appetite and was observed writing an incomprehensible “experiment” on a paper towel. Due to his bizarre behavior, delusional thoughts, and concerns about his inability to care for himself, the team admits Mr. H to the acute inpatient psychiatric unit on a voluntary commitment.

HISTORY Long-standing drug use and repeated hospital visits

Mr. H reports a history of drug use. His first documented ED visit was >5 years before his current admission. He has a family history of substance abuse and reports previously using methamphetamine, heroin, and alcohol. Mr. H was never diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, but when he was younger, there were suspicions of bipolar depression, with no contributing family psychiatric history. Though he took quetiapine at an unspecified younger age, Mr. H did not follow through with any outpatient mental health services or medications.

Mr. H first reported infestation

In the 6 months prior to his current admission, Mr. H came to the hospital >20 times for various reasons, including methamphetamine abuse, alcohol withdrawal, opiate overdose, cellulitis, wound checks, and 3 visits for hallucinations for which he requested physical evaluation and medical care. His substance use was the suspected cause of his tactile and visual hallucinations of infestation because formication

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

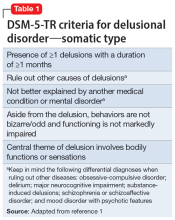

Delusional parasitosis (DP), also known as delusional infestation or Ekbom Syndrome, is a condition characterized by the fixed, false belief of an infestation without any objective evidence. This condition was previously defined in DSM-IV, but was removed from DSM-5-TR. In DSM-5-TR, DP is most closely associated with delusional disorder

DP is rare, affecting approximately 1.9 per 100,000 people. There has not been consistent data supporting differences in prevalence between sexes, but there is evidence for increasing incidence with age, with a mean age of diagnosis of 61.4.2,3 DP can be divided into 2 types based on the history and etiology of the symptoms: primary DP and secondary DP. Primary DP occurs when there is a failure to identify an organic cause for the occurrence of the symptoms. Therefore, primary DP requires an extensive investigation by a multidisciplinary team that commonly includes medical specialists for a nonpsychiatric workup. Secondary DP occurs when the patient has delusional symptoms associated with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, depression, stroke, diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency, or substance use.4

Though Mr. H initially presented to the ED, patients with DP commonly present to a primary care physician or dermatologist with the complaint of itching or feelings of insects, worms, or unclear organisms inside them. Patients with DP may often develop poor working relationships with physicians while obtaining multiple negative results. They may seek opinions from multiple specialists; however, patients typically do not consider psychiatrists as a source of help. When patients seek psychiatric care, often after a recommendation from a primary care physician or dermatologist, mental health clinicians should listen to and evaluate the patient holistically, continuing to rule out other possible etiologies.

[polldaddy:12570072]

TREATMENT Finding the right antipsychotic

In the psychiatric unit, Mr. H says he believes worms are exiting his ears, mouth, toenail, and self-inflicted scratch wounds. He believes he has been dealing with the parasites for >1 year and they are slowly draining his energy. Mr. H insists he contracted the “infection” from his home carpet, which was wet due to a flood in his house, and after he had fallen asleep following drug use. He also believes he acquired the parasites while walking barefoot along the beach and collecting rocks, and that there are multiple species living inside him, all intelligent enough to hide, making it difficult to prove their existence. He notes they vary in size, and some have red eyes.

During admission, Mr. H voices his frustration that clinicians had not found the worms he has been seeing. He continuously requests to review imaging performed during his visit and wants a multidisciplinary team to evaluate his case. He demands to test a cup with spit-up “samples,” believing the parasites would be visible under a microscope. Throughout his admission, Mr. H continues to take buprenorphine/naloxone and does not experience withdrawal symptoms. The treatment team titrates his quetiapine to 400 mg/d. Due to the lack of improvement, the team initiates olanzapine 5 mg/d at bedtime. However, Mr. H reports significant tinnitus and requests a medication change. He is started on haloperidol 5 mg twice daily.

Continue to: Mr. H begins to see improvements...

Mr. H begins to see improvements on Day 7 of taking haloperidol. He no longer brings up infestation but still acknowledges having worms inside him when directly asked. He says the worms cause him less distress than before and he is hopeful to live without discomfort. He also demonstrates an ability to conduct activities of daily living. Because Mr. H is being monitored on an acute inpatient psychiatric basis, he is deemed appropriate for discharge even though his symptoms have not yet fully resolved. After a 19-day hospital stay, Mr. H is discharged on haloperidol 15 mg/d and quetiapine 200 mg/d.

[polldaddy:12570074]

The authors’ observations

Mr. H asked to have his sputum examined. The “specimen sign,” also called “matchbox sign” or “Ziploc bag sign,” in which patients collect what they believe to be infected tissue or organisms in a container, is a well-studied part of DP.5 Such samples should be considered during initial encounters and can be examined for formal evaluation, but cautiously. Overtesting may incur a financial burden or reinforce deleterious beliefs and behaviors.

It can be difficult to identify triggers of DP. Research shows DP may arise from nonorganic and stressful life events, home floods, or contact with people infected with parasites.6,7 Organic causes have also been found, such as patients taking multiple medications for Parkinson disease who developed delusional symptoms.8 Buscarino et al9 reported the case of a woman who started to develop symptoms of delusions and hallucinations after being on high-dose amphetamines for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research shows that stopping the suspected medication commonly improves such symptoms.9,10 Although methamphetamine can remain detectable in urine for up to 4 days after use and potentially a few days longer for chronic users due to circulating levels,11 Mr. H’s symptoms continued for weeks after all substances of abuse should have been cleared from his system. This suggests he was experiencing a psychiatric illness and was accurate in distinguishing methamphetamine-induced from psychiatric-induced sensations. Regardless, polysubstance use has been shown to potentially increase the risk and play a role in the onset and progression of delusional illness, as seen in prior cases as well as in this case.9

It has been hypothesized that the pathophysiology of DP is associated with the deterioration of the striatal dopaminergic pathway, leading to an increase in extracellular dopamine levels. The striatum is responsible for most dopamine reuptake in the brain; therefore, certain drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and methylphenidate may precipitate symptoms of DP due to their blockade of presynaptic dopamine reuptake.12 Additionally, conditions that decrease the functioning of striatal dopamine transporters, such as schizophrenia or depression, may be underlying causes of DP.13

Treatment of DP remains a topic of debate. Most current recommendations appear to be based on a small, nonrandomized placebo-controlled trial.14 The first-generation antipsychotic pimozide had been a first-line treatment for DP, but its adverse effect profile, which includes QTc prolongation and extrapyramidal symptoms, led to the exploration of second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine and risperidone.15,16 There is a dearth of literature about the use of haloperidol, quetiapine, or a combination of both as treatment options for DP, though the combination of these 2 medications proved effective for Mr. H. Further research is necessary to justify changes to current treatment standards, but this finding highlights a successful symptom reduction achieved with this combination.

Continue to: Patients may experience genuine symptoms...

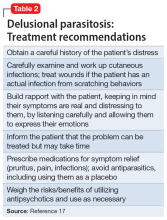

Patients may experience genuine symptoms despite the delusional nature of DP, and it is important for clinicians to recognize the potential burden and anxiety these individuals face. Patients may present with self-inflicted bruises, cuts, and erosions to gain access to infected areas, which may be confused with skin picking disorder. Excessive cleansing or use of irritant products can also cause skin damage, leading to other dermatological conditions that reinforce the patient’s belief that something is medically wrong. During treatment, consider medications for relief of pruritus or pain. Focus on offering patients the opportunity to express their concerns, treat them with empathy, avoid stigmatizing language such as “delusions” or “psychosis,” and refrain from contradicting them until a strong rapport has been established (Table 217).

Symptoms of DP can persist for months to years. Patients who fully recovered experienced a median duration of 0.5 years until symptom resolution, compared to incompletely recovered patients, who took approximately 1 year.18 Primary DP has slower improvement rates compared to secondary DP, with the median onset of effects occurring at Week 1.5 and peak improvements occurring at Week 6.16

OUTCOME Continued ED visits

Unfortunately, Mr. H does not follow through with his outpatient psychiatry appointments. In the 7 months following discharge, he visits the ED 8 times for alcohol intoxication, alcohol withdrawal, and methamphetamine abuse, in addition to 2 admissions for inpatient detoxification, during which he was still receiving the same scheduled medications (haloperidol 15 mg/d and quetiapine 200 mg/d). At each of his ED visits, there was no documentation of DP symptoms, which suggests his symptoms may have resolved.

Bottom Line

Because delusional parasitosis symptoms feel real to patients, it is crucial to build rapport to recommend and successfully initiate treatment. After ruling out nonpsychiatric etiologies, consider traditional treatment with antipsychotics, and consider medications for relief of pruritus or pain.

Related Resources

- Sellman D, Phan SV, Inyang M. Bugs on her skin—but nobody else sees them. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):48,50-53.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1428-1434. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.012

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Methylphenidate • Concerta

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Permethrin • Elimite

Phenobarbital • Solfoton, Tedral, Luminal

Pimozide • Orap

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Bailey CH, Andersen LK, Lowe GC, et al. A population-based study of the incidence of delusional infestation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-2010. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(5):1130-1135. doi:10.1111/bjd.12848

3. Kohorst JJ, Bailey CH, Andersen LK, et al. Prevalence of delusional infestation-a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):615-617. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0004

4. Freinhar JP. Delusions of parasitosis. Psychosomatics. 1984;25(1):47-53. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(84)73096-9

5. Reich A, Kwiatkowska D, Pacan P. Delusions of parasitosis: an update. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(4):631-638. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00324-3

6. Berrios GE. Delusional parasitosis and physical disease. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26(5):395-403. doi:10.1016/0010-440x(85)90077-x

7. Aizenberg D, Schwartz B, Zemishlany Z. Delusional parasitosis associated with phenelzine. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:716-717. doi:10.1192/bjp.159.5.716

8. Flann S, Shotbolt J, Kessel B, et al. Three cases of delusional parasitosis caused by dopamine agonists. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(7):740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03810.x

9. Buscarino M, Saal J, Young JL. Delusional parasitosis in a female treated with mixed amphetamine salts: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:624235. doi:10.1155/2012/624235

10. Elpern DJ. Cocaine abuse and delusions of parasitosis. Cutis. 1988;42(4):273-274.

11. Richards JR, Laurin EG. Methamphetamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated January 8, 2023. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430895/

12. Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. A new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68(6):1351-1358. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.07.061

13. Lipman ZM, Yosipovitch G. Substance use disorders and chronic itch. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(1):148-155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.117

14. Kenchaiah BK, Kumar S, Tharyan P. Atypical anti-psychotics in delusional parasitosis: a retrospective case series of 20 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(1):95-100. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04312.x

15. Laidler N. Delusions of parasitosis: a brief review of the literature and pathway for diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(1):13030/qt1fh739nx.

16. Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(5):500-508. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318185e774

17. Mumcuoglu KY, Leibovici V, Reuveni I, et al. Delusional parasitosis: diagnosis and treatment. Isr Med Assoc J. 2018;20(7):456-460.

18. Trabert W. 100 years of delusional parasitosis. Meta-analysis of 1,223 case reports. Psychopathology. 1995;28(5):238-246. doi:10.1159/000284934

CASE Detoxification and preoccupation with parasites

Mr. H, age 51, has an extensive history of alcohol and methamphetamine use. He presents to the emergency department (ED) requesting inpatient detoxification. He says he had been drinking alcohol but is unable to say how much. His blood ethanol level is 61 mg/dL (unintoxicated level: <50 mg/dL), and a urine drug screen is positive for methamphetamine; Mr. H also admits to using fentanyl. The ED team treats Mr. H’s electrolyte abnormalities, initiates thiamine supplementation, and transfers him to a unit for inpatient withdrawal management.

On the detoxification unit, Mr. H receives a total of 1,950 mg of phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal and stabilizes on a buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance dose of 8 mg/2 mg twice daily for methamphetamine and fentanyl use. Though he was not taking any psychiatric medications prior to his arrival at the ED, Mr. H agrees to restart quetiapine

During Mr. H’s 3-day detoxification, the psychiatry team evaluates him. Mr. H says he believes he is infested with worms. He describes a prior sensation of “meth mites,” or the feeling of bugs crawling under his skin, while using methamphetamines. However, Mr. H says his current infestation feels distinctively different, and he had continued to experience these

The psychiatry team expresses concern over his preoccupation with infestations, disheveled appearance, poor hygiene, and healed scars from excoriation. Mr. H also reports poor sleep and appetite and was observed writing an incomprehensible “experiment” on a paper towel. Due to his bizarre behavior, delusional thoughts, and concerns about his inability to care for himself, the team admits Mr. H to the acute inpatient psychiatric unit on a voluntary commitment.

HISTORY Long-standing drug use and repeated hospital visits

Mr. H reports a history of drug use. His first documented ED visit was >5 years before his current admission. He has a family history of substance abuse and reports previously using methamphetamine, heroin, and alcohol. Mr. H was never diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, but when he was younger, there were suspicions of bipolar depression, with no contributing family psychiatric history. Though he took quetiapine at an unspecified younger age, Mr. H did not follow through with any outpatient mental health services or medications.

Mr. H first reported infestation

In the 6 months prior to his current admission, Mr. H came to the hospital >20 times for various reasons, including methamphetamine abuse, alcohol withdrawal, opiate overdose, cellulitis, wound checks, and 3 visits for hallucinations for which he requested physical evaluation and medical care. His substance use was the suspected cause of his tactile and visual hallucinations of infestation because formication

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Delusional parasitosis (DP), also known as delusional infestation or Ekbom Syndrome, is a condition characterized by the fixed, false belief of an infestation without any objective evidence. This condition was previously defined in DSM-IV, but was removed from DSM-5-TR. In DSM-5-TR, DP is most closely associated with delusional disorder

DP is rare, affecting approximately 1.9 per 100,000 people. There has not been consistent data supporting differences in prevalence between sexes, but there is evidence for increasing incidence with age, with a mean age of diagnosis of 61.4.2,3 DP can be divided into 2 types based on the history and etiology of the symptoms: primary DP and secondary DP. Primary DP occurs when there is a failure to identify an organic cause for the occurrence of the symptoms. Therefore, primary DP requires an extensive investigation by a multidisciplinary team that commonly includes medical specialists for a nonpsychiatric workup. Secondary DP occurs when the patient has delusional symptoms associated with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, depression, stroke, diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency, or substance use.4

Though Mr. H initially presented to the ED, patients with DP commonly present to a primary care physician or dermatologist with the complaint of itching or feelings of insects, worms, or unclear organisms inside them. Patients with DP may often develop poor working relationships with physicians while obtaining multiple negative results. They may seek opinions from multiple specialists; however, patients typically do not consider psychiatrists as a source of help. When patients seek psychiatric care, often after a recommendation from a primary care physician or dermatologist, mental health clinicians should listen to and evaluate the patient holistically, continuing to rule out other possible etiologies.

[polldaddy:12570072]

TREATMENT Finding the right antipsychotic

In the psychiatric unit, Mr. H says he believes worms are exiting his ears, mouth, toenail, and self-inflicted scratch wounds. He believes he has been dealing with the parasites for >1 year and they are slowly draining his energy. Mr. H insists he contracted the “infection” from his home carpet, which was wet due to a flood in his house, and after he had fallen asleep following drug use. He also believes he acquired the parasites while walking barefoot along the beach and collecting rocks, and that there are multiple species living inside him, all intelligent enough to hide, making it difficult to prove their existence. He notes they vary in size, and some have red eyes.

During admission, Mr. H voices his frustration that clinicians had not found the worms he has been seeing. He continuously requests to review imaging performed during his visit and wants a multidisciplinary team to evaluate his case. He demands to test a cup with spit-up “samples,” believing the parasites would be visible under a microscope. Throughout his admission, Mr. H continues to take buprenorphine/naloxone and does not experience withdrawal symptoms. The treatment team titrates his quetiapine to 400 mg/d. Due to the lack of improvement, the team initiates olanzapine 5 mg/d at bedtime. However, Mr. H reports significant tinnitus and requests a medication change. He is started on haloperidol 5 mg twice daily.

Continue to: Mr. H begins to see improvements...

Mr. H begins to see improvements on Day 7 of taking haloperidol. He no longer brings up infestation but still acknowledges having worms inside him when directly asked. He says the worms cause him less distress than before and he is hopeful to live without discomfort. He also demonstrates an ability to conduct activities of daily living. Because Mr. H is being monitored on an acute inpatient psychiatric basis, he is deemed appropriate for discharge even though his symptoms have not yet fully resolved. After a 19-day hospital stay, Mr. H is discharged on haloperidol 15 mg/d and quetiapine 200 mg/d.

[polldaddy:12570074]

The authors’ observations

Mr. H asked to have his sputum examined. The “specimen sign,” also called “matchbox sign” or “Ziploc bag sign,” in which patients collect what they believe to be infected tissue or organisms in a container, is a well-studied part of DP.5 Such samples should be considered during initial encounters and can be examined for formal evaluation, but cautiously. Overtesting may incur a financial burden or reinforce deleterious beliefs and behaviors.

It can be difficult to identify triggers of DP. Research shows DP may arise from nonorganic and stressful life events, home floods, or contact with people infected with parasites.6,7 Organic causes have also been found, such as patients taking multiple medications for Parkinson disease who developed delusional symptoms.8 Buscarino et al9 reported the case of a woman who started to develop symptoms of delusions and hallucinations after being on high-dose amphetamines for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research shows that stopping the suspected medication commonly improves such symptoms.9,10 Although methamphetamine can remain detectable in urine for up to 4 days after use and potentially a few days longer for chronic users due to circulating levels,11 Mr. H’s symptoms continued for weeks after all substances of abuse should have been cleared from his system. This suggests he was experiencing a psychiatric illness and was accurate in distinguishing methamphetamine-induced from psychiatric-induced sensations. Regardless, polysubstance use has been shown to potentially increase the risk and play a role in the onset and progression of delusional illness, as seen in prior cases as well as in this case.9

It has been hypothesized that the pathophysiology of DP is associated with the deterioration of the striatal dopaminergic pathway, leading to an increase in extracellular dopamine levels. The striatum is responsible for most dopamine reuptake in the brain; therefore, certain drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and methylphenidate may precipitate symptoms of DP due to their blockade of presynaptic dopamine reuptake.12 Additionally, conditions that decrease the functioning of striatal dopamine transporters, such as schizophrenia or depression, may be underlying causes of DP.13

Treatment of DP remains a topic of debate. Most current recommendations appear to be based on a small, nonrandomized placebo-controlled trial.14 The first-generation antipsychotic pimozide had been a first-line treatment for DP, but its adverse effect profile, which includes QTc prolongation and extrapyramidal symptoms, led to the exploration of second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine and risperidone.15,16 There is a dearth of literature about the use of haloperidol, quetiapine, or a combination of both as treatment options for DP, though the combination of these 2 medications proved effective for Mr. H. Further research is necessary to justify changes to current treatment standards, but this finding highlights a successful symptom reduction achieved with this combination.

Continue to: Patients may experience genuine symptoms...

Patients may experience genuine symptoms despite the delusional nature of DP, and it is important for clinicians to recognize the potential burden and anxiety these individuals face. Patients may present with self-inflicted bruises, cuts, and erosions to gain access to infected areas, which may be confused with skin picking disorder. Excessive cleansing or use of irritant products can also cause skin damage, leading to other dermatological conditions that reinforce the patient’s belief that something is medically wrong. During treatment, consider medications for relief of pruritus or pain. Focus on offering patients the opportunity to express their concerns, treat them with empathy, avoid stigmatizing language such as “delusions” or “psychosis,” and refrain from contradicting them until a strong rapport has been established (Table 217).

Symptoms of DP can persist for months to years. Patients who fully recovered experienced a median duration of 0.5 years until symptom resolution, compared to incompletely recovered patients, who took approximately 1 year.18 Primary DP has slower improvement rates compared to secondary DP, with the median onset of effects occurring at Week 1.5 and peak improvements occurring at Week 6.16

OUTCOME Continued ED visits

Unfortunately, Mr. H does not follow through with his outpatient psychiatry appointments. In the 7 months following discharge, he visits the ED 8 times for alcohol intoxication, alcohol withdrawal, and methamphetamine abuse, in addition to 2 admissions for inpatient detoxification, during which he was still receiving the same scheduled medications (haloperidol 15 mg/d and quetiapine 200 mg/d). At each of his ED visits, there was no documentation of DP symptoms, which suggests his symptoms may have resolved.

Bottom Line

Because delusional parasitosis symptoms feel real to patients, it is crucial to build rapport to recommend and successfully initiate treatment. After ruling out nonpsychiatric etiologies, consider traditional treatment with antipsychotics, and consider medications for relief of pruritus or pain.

Related Resources

- Sellman D, Phan SV, Inyang M. Bugs on her skin—but nobody else sees them. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):48,50-53.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1428-1434. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.012

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Methylphenidate • Concerta

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Permethrin • Elimite

Phenobarbital • Solfoton, Tedral, Luminal

Pimozide • Orap

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakote

CASE Detoxification and preoccupation with parasites

Mr. H, age 51, has an extensive history of alcohol and methamphetamine use. He presents to the emergency department (ED) requesting inpatient detoxification. He says he had been drinking alcohol but is unable to say how much. His blood ethanol level is 61 mg/dL (unintoxicated level: <50 mg/dL), and a urine drug screen is positive for methamphetamine; Mr. H also admits to using fentanyl. The ED team treats Mr. H’s electrolyte abnormalities, initiates thiamine supplementation, and transfers him to a unit for inpatient withdrawal management.

On the detoxification unit, Mr. H receives a total of 1,950 mg of phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal and stabilizes on a buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance dose of 8 mg/2 mg twice daily for methamphetamine and fentanyl use. Though he was not taking any psychiatric medications prior to his arrival at the ED, Mr. H agrees to restart quetiapine

During Mr. H’s 3-day detoxification, the psychiatry team evaluates him. Mr. H says he believes he is infested with worms. He describes a prior sensation of “meth mites,” or the feeling of bugs crawling under his skin, while using methamphetamines. However, Mr. H says his current infestation feels distinctively different, and he had continued to experience these

The psychiatry team expresses concern over his preoccupation with infestations, disheveled appearance, poor hygiene, and healed scars from excoriation. Mr. H also reports poor sleep and appetite and was observed writing an incomprehensible “experiment” on a paper towel. Due to his bizarre behavior, delusional thoughts, and concerns about his inability to care for himself, the team admits Mr. H to the acute inpatient psychiatric unit on a voluntary commitment.

HISTORY Long-standing drug use and repeated hospital visits

Mr. H reports a history of drug use. His first documented ED visit was >5 years before his current admission. He has a family history of substance abuse and reports previously using methamphetamine, heroin, and alcohol. Mr. H was never diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, but when he was younger, there were suspicions of bipolar depression, with no contributing family psychiatric history. Though he took quetiapine at an unspecified younger age, Mr. H did not follow through with any outpatient mental health services or medications.

Mr. H first reported infestation

In the 6 months prior to his current admission, Mr. H came to the hospital >20 times for various reasons, including methamphetamine abuse, alcohol withdrawal, opiate overdose, cellulitis, wound checks, and 3 visits for hallucinations for which he requested physical evaluation and medical care. His substance use was the suspected cause of his tactile and visual hallucinations of infestation because formication

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Delusional parasitosis (DP), also known as delusional infestation or Ekbom Syndrome, is a condition characterized by the fixed, false belief of an infestation without any objective evidence. This condition was previously defined in DSM-IV, but was removed from DSM-5-TR. In DSM-5-TR, DP is most closely associated with delusional disorder

DP is rare, affecting approximately 1.9 per 100,000 people. There has not been consistent data supporting differences in prevalence between sexes, but there is evidence for increasing incidence with age, with a mean age of diagnosis of 61.4.2,3 DP can be divided into 2 types based on the history and etiology of the symptoms: primary DP and secondary DP. Primary DP occurs when there is a failure to identify an organic cause for the occurrence of the symptoms. Therefore, primary DP requires an extensive investigation by a multidisciplinary team that commonly includes medical specialists for a nonpsychiatric workup. Secondary DP occurs when the patient has delusional symptoms associated with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, depression, stroke, diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency, or substance use.4

Though Mr. H initially presented to the ED, patients with DP commonly present to a primary care physician or dermatologist with the complaint of itching or feelings of insects, worms, or unclear organisms inside them. Patients with DP may often develop poor working relationships with physicians while obtaining multiple negative results. They may seek opinions from multiple specialists; however, patients typically do not consider psychiatrists as a source of help. When patients seek psychiatric care, often after a recommendation from a primary care physician or dermatologist, mental health clinicians should listen to and evaluate the patient holistically, continuing to rule out other possible etiologies.

[polldaddy:12570072]

TREATMENT Finding the right antipsychotic

In the psychiatric unit, Mr. H says he believes worms are exiting his ears, mouth, toenail, and self-inflicted scratch wounds. He believes he has been dealing with the parasites for >1 year and they are slowly draining his energy. Mr. H insists he contracted the “infection” from his home carpet, which was wet due to a flood in his house, and after he had fallen asleep following drug use. He also believes he acquired the parasites while walking barefoot along the beach and collecting rocks, and that there are multiple species living inside him, all intelligent enough to hide, making it difficult to prove their existence. He notes they vary in size, and some have red eyes.

During admission, Mr. H voices his frustration that clinicians had not found the worms he has been seeing. He continuously requests to review imaging performed during his visit and wants a multidisciplinary team to evaluate his case. He demands to test a cup with spit-up “samples,” believing the parasites would be visible under a microscope. Throughout his admission, Mr. H continues to take buprenorphine/naloxone and does not experience withdrawal symptoms. The treatment team titrates his quetiapine to 400 mg/d. Due to the lack of improvement, the team initiates olanzapine 5 mg/d at bedtime. However, Mr. H reports significant tinnitus and requests a medication change. He is started on haloperidol 5 mg twice daily.

Continue to: Mr. H begins to see improvements...

Mr. H begins to see improvements on Day 7 of taking haloperidol. He no longer brings up infestation but still acknowledges having worms inside him when directly asked. He says the worms cause him less distress than before and he is hopeful to live without discomfort. He also demonstrates an ability to conduct activities of daily living. Because Mr. H is being monitored on an acute inpatient psychiatric basis, he is deemed appropriate for discharge even though his symptoms have not yet fully resolved. After a 19-day hospital stay, Mr. H is discharged on haloperidol 15 mg/d and quetiapine 200 mg/d.

[polldaddy:12570074]

The authors’ observations

Mr. H asked to have his sputum examined. The “specimen sign,” also called “matchbox sign” or “Ziploc bag sign,” in which patients collect what they believe to be infected tissue or organisms in a container, is a well-studied part of DP.5 Such samples should be considered during initial encounters and can be examined for formal evaluation, but cautiously. Overtesting may incur a financial burden or reinforce deleterious beliefs and behaviors.

It can be difficult to identify triggers of DP. Research shows DP may arise from nonorganic and stressful life events, home floods, or contact with people infected with parasites.6,7 Organic causes have also been found, such as patients taking multiple medications for Parkinson disease who developed delusional symptoms.8 Buscarino et al9 reported the case of a woman who started to develop symptoms of delusions and hallucinations after being on high-dose amphetamines for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research shows that stopping the suspected medication commonly improves such symptoms.9,10 Although methamphetamine can remain detectable in urine for up to 4 days after use and potentially a few days longer for chronic users due to circulating levels,11 Mr. H’s symptoms continued for weeks after all substances of abuse should have been cleared from his system. This suggests he was experiencing a psychiatric illness and was accurate in distinguishing methamphetamine-induced from psychiatric-induced sensations. Regardless, polysubstance use has been shown to potentially increase the risk and play a role in the onset and progression of delusional illness, as seen in prior cases as well as in this case.9

It has been hypothesized that the pathophysiology of DP is associated with the deterioration of the striatal dopaminergic pathway, leading to an increase in extracellular dopamine levels. The striatum is responsible for most dopamine reuptake in the brain; therefore, certain drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and methylphenidate may precipitate symptoms of DP due to their blockade of presynaptic dopamine reuptake.12 Additionally, conditions that decrease the functioning of striatal dopamine transporters, such as schizophrenia or depression, may be underlying causes of DP.13

Treatment of DP remains a topic of debate. Most current recommendations appear to be based on a small, nonrandomized placebo-controlled trial.14 The first-generation antipsychotic pimozide had been a first-line treatment for DP, but its adverse effect profile, which includes QTc prolongation and extrapyramidal symptoms, led to the exploration of second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine and risperidone.15,16 There is a dearth of literature about the use of haloperidol, quetiapine, or a combination of both as treatment options for DP, though the combination of these 2 medications proved effective for Mr. H. Further research is necessary to justify changes to current treatment standards, but this finding highlights a successful symptom reduction achieved with this combination.

Continue to: Patients may experience genuine symptoms...

Patients may experience genuine symptoms despite the delusional nature of DP, and it is important for clinicians to recognize the potential burden and anxiety these individuals face. Patients may present with self-inflicted bruises, cuts, and erosions to gain access to infected areas, which may be confused with skin picking disorder. Excessive cleansing or use of irritant products can also cause skin damage, leading to other dermatological conditions that reinforce the patient’s belief that something is medically wrong. During treatment, consider medications for relief of pruritus or pain. Focus on offering patients the opportunity to express their concerns, treat them with empathy, avoid stigmatizing language such as “delusions” or “psychosis,” and refrain from contradicting them until a strong rapport has been established (Table 217).

Symptoms of DP can persist for months to years. Patients who fully recovered experienced a median duration of 0.5 years until symptom resolution, compared to incompletely recovered patients, who took approximately 1 year.18 Primary DP has slower improvement rates compared to secondary DP, with the median onset of effects occurring at Week 1.5 and peak improvements occurring at Week 6.16

OUTCOME Continued ED visits

Unfortunately, Mr. H does not follow through with his outpatient psychiatry appointments. In the 7 months following discharge, he visits the ED 8 times for alcohol intoxication, alcohol withdrawal, and methamphetamine abuse, in addition to 2 admissions for inpatient detoxification, during which he was still receiving the same scheduled medications (haloperidol 15 mg/d and quetiapine 200 mg/d). At each of his ED visits, there was no documentation of DP symptoms, which suggests his symptoms may have resolved.

Bottom Line

Because delusional parasitosis symptoms feel real to patients, it is crucial to build rapport to recommend and successfully initiate treatment. After ruling out nonpsychiatric etiologies, consider traditional treatment with antipsychotics, and consider medications for relief of pruritus or pain.

Related Resources

- Sellman D, Phan SV, Inyang M. Bugs on her skin—but nobody else sees them. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):48,50-53.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1428-1434. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.012

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Methylphenidate • Concerta

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Permethrin • Elimite

Phenobarbital • Solfoton, Tedral, Luminal

Pimozide • Orap

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Bailey CH, Andersen LK, Lowe GC, et al. A population-based study of the incidence of delusional infestation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-2010. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(5):1130-1135. doi:10.1111/bjd.12848

3. Kohorst JJ, Bailey CH, Andersen LK, et al. Prevalence of delusional infestation-a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):615-617. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0004

4. Freinhar JP. Delusions of parasitosis. Psychosomatics. 1984;25(1):47-53. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(84)73096-9

5. Reich A, Kwiatkowska D, Pacan P. Delusions of parasitosis: an update. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(4):631-638. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00324-3

6. Berrios GE. Delusional parasitosis and physical disease. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26(5):395-403. doi:10.1016/0010-440x(85)90077-x

7. Aizenberg D, Schwartz B, Zemishlany Z. Delusional parasitosis associated with phenelzine. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:716-717. doi:10.1192/bjp.159.5.716

8. Flann S, Shotbolt J, Kessel B, et al. Three cases of delusional parasitosis caused by dopamine agonists. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(7):740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03810.x

9. Buscarino M, Saal J, Young JL. Delusional parasitosis in a female treated with mixed amphetamine salts: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:624235. doi:10.1155/2012/624235

10. Elpern DJ. Cocaine abuse and delusions of parasitosis. Cutis. 1988;42(4):273-274.

11. Richards JR, Laurin EG. Methamphetamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated January 8, 2023. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430895/

12. Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. A new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68(6):1351-1358. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.07.061

13. Lipman ZM, Yosipovitch G. Substance use disorders and chronic itch. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(1):148-155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.117

14. Kenchaiah BK, Kumar S, Tharyan P. Atypical anti-psychotics in delusional parasitosis: a retrospective case series of 20 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(1):95-100. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04312.x

15. Laidler N. Delusions of parasitosis: a brief review of the literature and pathway for diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(1):13030/qt1fh739nx.

16. Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(5):500-508. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318185e774

17. Mumcuoglu KY, Leibovici V, Reuveni I, et al. Delusional parasitosis: diagnosis and treatment. Isr Med Assoc J. 2018;20(7):456-460.

18. Trabert W. 100 years of delusional parasitosis. Meta-analysis of 1,223 case reports. Psychopathology. 1995;28(5):238-246. doi:10.1159/000284934

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Bailey CH, Andersen LK, Lowe GC, et al. A population-based study of the incidence of delusional infestation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-2010. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(5):1130-1135. doi:10.1111/bjd.12848

3. Kohorst JJ, Bailey CH, Andersen LK, et al. Prevalence of delusional infestation-a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):615-617. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0004

4. Freinhar JP. Delusions of parasitosis. Psychosomatics. 1984;25(1):47-53. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(84)73096-9

5. Reich A, Kwiatkowska D, Pacan P. Delusions of parasitosis: an update. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(4):631-638. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00324-3

6. Berrios GE. Delusional parasitosis and physical disease. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26(5):395-403. doi:10.1016/0010-440x(85)90077-x

7. Aizenberg D, Schwartz B, Zemishlany Z. Delusional parasitosis associated with phenelzine. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:716-717. doi:10.1192/bjp.159.5.716

8. Flann S, Shotbolt J, Kessel B, et al. Three cases of delusional parasitosis caused by dopamine agonists. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(7):740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03810.x

9. Buscarino M, Saal J, Young JL. Delusional parasitosis in a female treated with mixed amphetamine salts: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:624235. doi:10.1155/2012/624235

10. Elpern DJ. Cocaine abuse and delusions of parasitosis. Cutis. 1988;42(4):273-274.

11. Richards JR, Laurin EG. Methamphetamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated January 8, 2023. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430895/

12. Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. A new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68(6):1351-1358. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.07.061

13. Lipman ZM, Yosipovitch G. Substance use disorders and chronic itch. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(1):148-155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.117

14. Kenchaiah BK, Kumar S, Tharyan P. Atypical anti-psychotics in delusional parasitosis: a retrospective case series of 20 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(1):95-100. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04312.x

15. Laidler N. Delusions of parasitosis: a brief review of the literature and pathway for diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(1):13030/qt1fh739nx.

16. Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(5):500-508. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318185e774

17. Mumcuoglu KY, Leibovici V, Reuveni I, et al. Delusional parasitosis: diagnosis and treatment. Isr Med Assoc J. 2018;20(7):456-460.

18. Trabert W. 100 years of delusional parasitosis. Meta-analysis of 1,223 case reports. Psychopathology. 1995;28(5):238-246. doi:10.1159/000284934

Extended-release injectable naltrexone for opioid use disorder

We appreciate the important review by Gluck et al (“Managing patients with comorbid opioid and alcohol use disorders,”

XR-NTX should be considered an equal OUD treatment alternative to buprenorphine-naloxone, especially for patients who prefer an opioid-free option.1,2 It has the added advantage of being FDA-approved for both AUD and OUD.

One obstacle to the success of XR-NTX is the induction period. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network X:BOT trial found that once the induction hurdle was surmounted, XR-NTX and buprenorphine were equally effective in a population of approximately 80% heroin users and two-thirds injection drug users.2 Patient variables that predict successful induction include young age, baseline preference for XR-NTX, fewer drug complications, and fewer family/social complications.3 If the length of the induction (usually 7 to 10 days) is a deterrent, a study supported the feasibility of a 5-day outpatient XR-NTX induction.4 Further research is needed to improve successful induction for XR-NTX.

Ashmeer Ogbuchi, MD

Karen Drexler, MD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif Z, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205. doi:10.1001/ jamapsychiatry.2017.3206

2. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32812-x

3. Murphy SM, Jeng PJ, McCollister KE, et al. Cost‐effectiveness implications of increasing the efficiency of the extended‐release naltrexone induction process for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a secondary analysis. Addiction. 2021;116(12)3444-3453. doi:10.1111/add.15531

4. Sibai M, Mishlen K, Nunes EV, et al. A week-long outpatient induction onto XR-naltrexone in patients with opioid use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(3):289-296. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1700265

Continue to: The authors respond

The authors respond

We appreciate Drs. Ogbuchi and Drexler for their thoughtful attention to our review. They proposed amending our original algorithm, recommending that XR-NTX be considered as another first-line option for patients with OUD. We agree with this suggestion, particularly for inpatients. However, we have some reservations about applying this suggestion to outpatient treatment. Though research evidence from Lee et al1 indicates that once initiation is completed, both medications are equally safe and effective, the initial attrition rate in the XR-NTX group was much higher (28% vs 6%, P < .0001), which suggests lower acceptability/tolerability compared with buprenorphine. Notably, the initiation of both medications in Lee et al1 was done in an inpatient setting. Moreover, although some medications are endorsed as “first-line,” the actual utilization rate is often influenced by many factors, including the ease of treatment initiation. Wakeman et al2 found the most common treatment modality received by patients with OUD was nonintensive behavioral health (59.5%), followed by inpatient withdrawal management and residential treatment (15.2%). Among all patients in the Wakeman study,2 only 12.5% received buprenorphine or methadone, and 2.4% received naltrexone.

Data from our clinic corroborate this trend. Currently, in our clinic approximately 300 patients with OUD are receiving medications, including approximately 250 on buprenorphine (including 5 to 10 on the long-acting injectable formulation), 50 on methadone, and only 1 or 2 on XR-NTX. Though this disparity may reflect bias in our clinicians’ prescribing practices, in the past few years we have had many unsuccessful attempts at initiating XR-NTX. To our disappointment, a theoretically excellent medication has not translated clinically. The recent surge in fentanyl use further complicates XR-NTX initiation for OUD, because the length of induction may be longer.

In conclusion, we agree that XR-NTX is a potential treatment option for patients with OUD, but clinicians should be cognizant of the potential barriers; inform patients of the advantages, expectations, and challenges; and respect patients’ informed decisions.

Rachel Gluck, MD

Karen Hochman, MD

Yi-lang Tang, MD, PhD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32812-x

2. Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

We appreciate the important review by Gluck et al (“Managing patients with comorbid opioid and alcohol use disorders,”

XR-NTX should be considered an equal OUD treatment alternative to buprenorphine-naloxone, especially for patients who prefer an opioid-free option.1,2 It has the added advantage of being FDA-approved for both AUD and OUD.

One obstacle to the success of XR-NTX is the induction period. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network X:BOT trial found that once the induction hurdle was surmounted, XR-NTX and buprenorphine were equally effective in a population of approximately 80% heroin users and two-thirds injection drug users.2 Patient variables that predict successful induction include young age, baseline preference for XR-NTX, fewer drug complications, and fewer family/social complications.3 If the length of the induction (usually 7 to 10 days) is a deterrent, a study supported the feasibility of a 5-day outpatient XR-NTX induction.4 Further research is needed to improve successful induction for XR-NTX.

Ashmeer Ogbuchi, MD

Karen Drexler, MD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif Z, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205. doi:10.1001/ jamapsychiatry.2017.3206

2. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32812-x

3. Murphy SM, Jeng PJ, McCollister KE, et al. Cost‐effectiveness implications of increasing the efficiency of the extended‐release naltrexone induction process for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a secondary analysis. Addiction. 2021;116(12)3444-3453. doi:10.1111/add.15531

4. Sibai M, Mishlen K, Nunes EV, et al. A week-long outpatient induction onto XR-naltrexone in patients with opioid use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(3):289-296. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1700265

Continue to: The authors respond

The authors respond

We appreciate Drs. Ogbuchi and Drexler for their thoughtful attention to our review. They proposed amending our original algorithm, recommending that XR-NTX be considered as another first-line option for patients with OUD. We agree with this suggestion, particularly for inpatients. However, we have some reservations about applying this suggestion to outpatient treatment. Though research evidence from Lee et al1 indicates that once initiation is completed, both medications are equally safe and effective, the initial attrition rate in the XR-NTX group was much higher (28% vs 6%, P < .0001), which suggests lower acceptability/tolerability compared with buprenorphine. Notably, the initiation of both medications in Lee et al1 was done in an inpatient setting. Moreover, although some medications are endorsed as “first-line,” the actual utilization rate is often influenced by many factors, including the ease of treatment initiation. Wakeman et al2 found the most common treatment modality received by patients with OUD was nonintensive behavioral health (59.5%), followed by inpatient withdrawal management and residential treatment (15.2%). Among all patients in the Wakeman study,2 only 12.5% received buprenorphine or methadone, and 2.4% received naltrexone.

Data from our clinic corroborate this trend. Currently, in our clinic approximately 300 patients with OUD are receiving medications, including approximately 250 on buprenorphine (including 5 to 10 on the long-acting injectable formulation), 50 on methadone, and only 1 or 2 on XR-NTX. Though this disparity may reflect bias in our clinicians’ prescribing practices, in the past few years we have had many unsuccessful attempts at initiating XR-NTX. To our disappointment, a theoretically excellent medication has not translated clinically. The recent surge in fentanyl use further complicates XR-NTX initiation for OUD, because the length of induction may be longer.

In conclusion, we agree that XR-NTX is a potential treatment option for patients with OUD, but clinicians should be cognizant of the potential barriers; inform patients of the advantages, expectations, and challenges; and respect patients’ informed decisions.

Rachel Gluck, MD

Karen Hochman, MD

Yi-lang Tang, MD, PhD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32812-x

2. Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

We appreciate the important review by Gluck et al (“Managing patients with comorbid opioid and alcohol use disorders,”

XR-NTX should be considered an equal OUD treatment alternative to buprenorphine-naloxone, especially for patients who prefer an opioid-free option.1,2 It has the added advantage of being FDA-approved for both AUD and OUD.

One obstacle to the success of XR-NTX is the induction period. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network X:BOT trial found that once the induction hurdle was surmounted, XR-NTX and buprenorphine were equally effective in a population of approximately 80% heroin users and two-thirds injection drug users.2 Patient variables that predict successful induction include young age, baseline preference for XR-NTX, fewer drug complications, and fewer family/social complications.3 If the length of the induction (usually 7 to 10 days) is a deterrent, a study supported the feasibility of a 5-day outpatient XR-NTX induction.4 Further research is needed to improve successful induction for XR-NTX.

Ashmeer Ogbuchi, MD

Karen Drexler, MD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif Z, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205. doi:10.1001/ jamapsychiatry.2017.3206

2. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32812-x

3. Murphy SM, Jeng PJ, McCollister KE, et al. Cost‐effectiveness implications of increasing the efficiency of the extended‐release naltrexone induction process for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a secondary analysis. Addiction. 2021;116(12)3444-3453. doi:10.1111/add.15531

4. Sibai M, Mishlen K, Nunes EV, et al. A week-long outpatient induction onto XR-naltrexone in patients with opioid use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(3):289-296. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1700265

Continue to: The authors respond

The authors respond

We appreciate Drs. Ogbuchi and Drexler for their thoughtful attention to our review. They proposed amending our original algorithm, recommending that XR-NTX be considered as another first-line option for patients with OUD. We agree with this suggestion, particularly for inpatients. However, we have some reservations about applying this suggestion to outpatient treatment. Though research evidence from Lee et al1 indicates that once initiation is completed, both medications are equally safe and effective, the initial attrition rate in the XR-NTX group was much higher (28% vs 6%, P < .0001), which suggests lower acceptability/tolerability compared with buprenorphine. Notably, the initiation of both medications in Lee et al1 was done in an inpatient setting. Moreover, although some medications are endorsed as “first-line,” the actual utilization rate is often influenced by many factors, including the ease of treatment initiation. Wakeman et al2 found the most common treatment modality received by patients with OUD was nonintensive behavioral health (59.5%), followed by inpatient withdrawal management and residential treatment (15.2%). Among all patients in the Wakeman study,2 only 12.5% received buprenorphine or methadone, and 2.4% received naltrexone.

Data from our clinic corroborate this trend. Currently, in our clinic approximately 300 patients with OUD are receiving medications, including approximately 250 on buprenorphine (including 5 to 10 on the long-acting injectable formulation), 50 on methadone, and only 1 or 2 on XR-NTX. Though this disparity may reflect bias in our clinicians’ prescribing practices, in the past few years we have had many unsuccessful attempts at initiating XR-NTX. To our disappointment, a theoretically excellent medication has not translated clinically. The recent surge in fentanyl use further complicates XR-NTX initiation for OUD, because the length of induction may be longer.

In conclusion, we agree that XR-NTX is a potential treatment option for patients with OUD, but clinicians should be cognizant of the potential barriers; inform patients of the advantages, expectations, and challenges; and respect patients’ informed decisions.

Rachel Gluck, MD

Karen Hochman, MD

Yi-lang Tang, MD, PhD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32812-x

2. Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

Reassuring data on stimulants for ADHD in kids and later substance abuse

“Throughout rigorous analyses, and after accounting for more than 70 variables in this longitudinal sample of children with ADHD taking stimulants, we did not find an association with later substance use,” lead investigator Brooke Molina, PhD, director of the youth and family research program at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Protective effect?

Owing to symptoms of impulsivity inherent to ADHD, the disorder itself carries a risk for elevated substance use, the investigators note.

They speculate that this may be why some previous research suggests prescription stimulants reduce the risk of subsequent substance use disorder. However, other studies have found no such protective link.

To shed more light on the issue, the investigators used data from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD, a multicenter, 14-month randomized clinical trial of medication and behavioral therapy for children with ADHD. However, for the purposes of the present study, investigators focused only on stimulant use in children.

At the time of recruitment, the children were aged 7-9 and had been diagnosed with ADHD between 1994 and 1996.

Investigators assessed the participants prior to randomization, at months 3 and 9, and at the end of treatment. They were then followed for 16 years and were assessed at years 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 until a mean age of 25.

During 12-, 14-, and 16-year follow-up, participants completed a questionnaire on their use of alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and several illicit and prescription drugs.

Investigators collected information on participants’ stimulant treatment via the Services for Children and Adolescents Parent Interview until they reached age 18. After that, participants reported their own stimulant treatment.

A total of 579 participants were included in the analysis. Of these, 61% were White, 20% were Black, and 8% were Hispanic.

Decline in stimulant use over time

The analysis showed that stimulant use declined “precipitously” over time – from 60% at the 2- and 3-year assessments to an average of 7% during early adulthood.

The investigators also found that for some participants, substance use increased steadily through adolescence and remained stable through early adulthood. For instance, 36.5% of the adolescents in the total cohort reported smoking tobacco daily, and 29.6% reported using marijuana every week.

In addition, approximately 21% of the participants indulged in heavy drinking at least once a week, and 6% reported “other” substance use, which included sedative misuse, heroin, inhalants, hallucinogens, or other substances taken to “get high.”

After accounting for developmental trends in substance use in the sample through adolescence into early adulthood with several rigorous statistical models, the researchers found no association between current or prior stimulant treatment and cigarette, marijuana, alcohol, or other substance use, with one exception.

While cumulative stimulant treatment was associated with increased heavy drinking, the effect size of this association was small. Each additional year of cumulative stimulant use was estimated to increase participants’ likelihood of any binge drinking/drunkenness vs. none in the past year by 4% (95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.08; P =.03).

When the investigators used a causal analytic method to account for age and other time-varying characteristics, including household income, behavior problems, and parental support, there was no evidence that current (B range, –0.62-0.34) or prior stimulant treatment (B range, –0.06-0.70) or their interaction (B range, –0.49-0.86) was associated with substance use in adulthood.

Dr. Molina noted that although participants were recruited from multiple sites, the sample may not be generalizable because children and parents who present for an intensive treatment study such as this are not necessarily representative of the general ADHD population.

Reassuring findings

In a comment, Julie Schweitzer, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, said she hopes the study findings will quell the stigma surrounding stimulant use by children with ADHD.

“Parents’ fears that stimulant use will lead to a substance use disorder inhibits them from bringing their children for an ADHD evaluation, thus reducing the likelihood that they will receive timely treatment,” Dr. Schweitzer said.

“While stimulant medication is the first-line treatment most often recommended for most persons with ADHD, by not following through on evaluations, parents also miss the opportunity to learn about nonpharmacological strategies that might also be helpful to help cope with ADHD symptoms and its potential co-occurring challenges,” she added.

Dr. Schweitzer also noted that many parents hope their children will outgrow the symptoms without realizing that by not obtaining an evaluation and treatment for their child, there is an associated cost, including less than optimal academic performance, social relationships, and emotional health.

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD was a National Institute of Mental Health cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study and under a National Institute on Drug Abuse contract followed by a data analysis grant. Dr. Molina reported grants from the NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Throughout rigorous analyses, and after accounting for more than 70 variables in this longitudinal sample of children with ADHD taking stimulants, we did not find an association with later substance use,” lead investigator Brooke Molina, PhD, director of the youth and family research program at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Protective effect?

Owing to symptoms of impulsivity inherent to ADHD, the disorder itself carries a risk for elevated substance use, the investigators note.

They speculate that this may be why some previous research suggests prescription stimulants reduce the risk of subsequent substance use disorder. However, other studies have found no such protective link.

To shed more light on the issue, the investigators used data from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD, a multicenter, 14-month randomized clinical trial of medication and behavioral therapy for children with ADHD. However, for the purposes of the present study, investigators focused only on stimulant use in children.

At the time of recruitment, the children were aged 7-9 and had been diagnosed with ADHD between 1994 and 1996.

Investigators assessed the participants prior to randomization, at months 3 and 9, and at the end of treatment. They were then followed for 16 years and were assessed at years 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 until a mean age of 25.

During 12-, 14-, and 16-year follow-up, participants completed a questionnaire on their use of alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and several illicit and prescription drugs.

Investigators collected information on participants’ stimulant treatment via the Services for Children and Adolescents Parent Interview until they reached age 18. After that, participants reported their own stimulant treatment.

A total of 579 participants were included in the analysis. Of these, 61% were White, 20% were Black, and 8% were Hispanic.

Decline in stimulant use over time

The analysis showed that stimulant use declined “precipitously” over time – from 60% at the 2- and 3-year assessments to an average of 7% during early adulthood.

The investigators also found that for some participants, substance use increased steadily through adolescence and remained stable through early adulthood. For instance, 36.5% of the adolescents in the total cohort reported smoking tobacco daily, and 29.6% reported using marijuana every week.

In addition, approximately 21% of the participants indulged in heavy drinking at least once a week, and 6% reported “other” substance use, which included sedative misuse, heroin, inhalants, hallucinogens, or other substances taken to “get high.”

After accounting for developmental trends in substance use in the sample through adolescence into early adulthood with several rigorous statistical models, the researchers found no association between current or prior stimulant treatment and cigarette, marijuana, alcohol, or other substance use, with one exception.

While cumulative stimulant treatment was associated with increased heavy drinking, the effect size of this association was small. Each additional year of cumulative stimulant use was estimated to increase participants’ likelihood of any binge drinking/drunkenness vs. none in the past year by 4% (95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.08; P =.03).

When the investigators used a causal analytic method to account for age and other time-varying characteristics, including household income, behavior problems, and parental support, there was no evidence that current (B range, –0.62-0.34) or prior stimulant treatment (B range, –0.06-0.70) or their interaction (B range, –0.49-0.86) was associated with substance use in adulthood.

Dr. Molina noted that although participants were recruited from multiple sites, the sample may not be generalizable because children and parents who present for an intensive treatment study such as this are not necessarily representative of the general ADHD population.

Reassuring findings

In a comment, Julie Schweitzer, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, said she hopes the study findings will quell the stigma surrounding stimulant use by children with ADHD.

“Parents’ fears that stimulant use will lead to a substance use disorder inhibits them from bringing their children for an ADHD evaluation, thus reducing the likelihood that they will receive timely treatment,” Dr. Schweitzer said.

“While stimulant medication is the first-line treatment most often recommended for most persons with ADHD, by not following through on evaluations, parents also miss the opportunity to learn about nonpharmacological strategies that might also be helpful to help cope with ADHD symptoms and its potential co-occurring challenges,” she added.

Dr. Schweitzer also noted that many parents hope their children will outgrow the symptoms without realizing that by not obtaining an evaluation and treatment for their child, there is an associated cost, including less than optimal academic performance, social relationships, and emotional health.

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD was a National Institute of Mental Health cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study and under a National Institute on Drug Abuse contract followed by a data analysis grant. Dr. Molina reported grants from the NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Throughout rigorous analyses, and after accounting for more than 70 variables in this longitudinal sample of children with ADHD taking stimulants, we did not find an association with later substance use,” lead investigator Brooke Molina, PhD, director of the youth and family research program at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Protective effect?

Owing to symptoms of impulsivity inherent to ADHD, the disorder itself carries a risk for elevated substance use, the investigators note.

They speculate that this may be why some previous research suggests prescription stimulants reduce the risk of subsequent substance use disorder. However, other studies have found no such protective link.

To shed more light on the issue, the investigators used data from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD, a multicenter, 14-month randomized clinical trial of medication and behavioral therapy for children with ADHD. However, for the purposes of the present study, investigators focused only on stimulant use in children.

At the time of recruitment, the children were aged 7-9 and had been diagnosed with ADHD between 1994 and 1996.

Investigators assessed the participants prior to randomization, at months 3 and 9, and at the end of treatment. They were then followed for 16 years and were assessed at years 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 until a mean age of 25.

During 12-, 14-, and 16-year follow-up, participants completed a questionnaire on their use of alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and several illicit and prescription drugs.

Investigators collected information on participants’ stimulant treatment via the Services for Children and Adolescents Parent Interview until they reached age 18. After that, participants reported their own stimulant treatment.

A total of 579 participants were included in the analysis. Of these, 61% were White, 20% were Black, and 8% were Hispanic.

Decline in stimulant use over time

The analysis showed that stimulant use declined “precipitously” over time – from 60% at the 2- and 3-year assessments to an average of 7% during early adulthood.

The investigators also found that for some participants, substance use increased steadily through adolescence and remained stable through early adulthood. For instance, 36.5% of the adolescents in the total cohort reported smoking tobacco daily, and 29.6% reported using marijuana every week.

In addition, approximately 21% of the participants indulged in heavy drinking at least once a week, and 6% reported “other” substance use, which included sedative misuse, heroin, inhalants, hallucinogens, or other substances taken to “get high.”

After accounting for developmental trends in substance use in the sample through adolescence into early adulthood with several rigorous statistical models, the researchers found no association between current or prior stimulant treatment and cigarette, marijuana, alcohol, or other substance use, with one exception.

While cumulative stimulant treatment was associated with increased heavy drinking, the effect size of this association was small. Each additional year of cumulative stimulant use was estimated to increase participants’ likelihood of any binge drinking/drunkenness vs. none in the past year by 4% (95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.08; P =.03).

When the investigators used a causal analytic method to account for age and other time-varying characteristics, including household income, behavior problems, and parental support, there was no evidence that current (B range, –0.62-0.34) or prior stimulant treatment (B range, –0.06-0.70) or their interaction (B range, –0.49-0.86) was associated with substance use in adulthood.

Dr. Molina noted that although participants were recruited from multiple sites, the sample may not be generalizable because children and parents who present for an intensive treatment study such as this are not necessarily representative of the general ADHD population.

Reassuring findings

In a comment, Julie Schweitzer, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, said she hopes the study findings will quell the stigma surrounding stimulant use by children with ADHD.

“Parents’ fears that stimulant use will lead to a substance use disorder inhibits them from bringing their children for an ADHD evaluation, thus reducing the likelihood that they will receive timely treatment,” Dr. Schweitzer said.