User login

The Hospitalist only

Step 1 scoring moves to pass/fail: Hospitalists’ role and unintended consequences

The National Board of Medical Examiners recently announced a change in the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting from a 3-digit score to a pass/fail score beginning in 2022.1 Endorsed by a broad coalition of organizations involved in undergraduate (UME) and graduate medical education (GME), this change is intended as a first step toward systemic improvements in the UME-GME transition to residency by promoting holistic reviews of applicants. Additionally, it is meant to tackle widespread concerns about medical student distress brought about by the residency selection process. For example, switching to pass/fail preclinical curricula has resulted in an improvement in medical student well-being at many medical schools.2 It is the hope that a mirrored change in Step 1 may similarly improve mental health and encourage a growth mindset towards learning.

On the other hand, many residency programs rely on USMLE scores for screening potential candidates, especially as application inflation has burdened programs with thousands of applications.3 The change to a pass/fail Step 1 score will likely shift emphasis and stress to the Step 2 CK Exam, essentially negating the intended effect. Furthermore, for schools still reporting NBME Subject (shelf) Exam scores and Clerkship grades, there will likely be a greater emphasis placed on these metrics as well. The need for objective assessment methods are seen by many as so critical that some GME leaders have advocated for instituting entrance exams or requiring a Standardized Letter of Evaluation as a prerequisite to residency application. Finally, medical students jockeying for competitive residency positions may also feel pressured to distinguish themselves by boosting other aspects of their portfolio by taking a research year or applying for away electives, which risks marginalizing students of lesser means or with family responsibilities.

Ultimately, the change to a pass/fail Step 1 exam will likely do little to address the expanding gulf between the UME and GME communities. Residency program directors are searching for students with qualities of a good physician, such as interpersonal skills, “teamsmanship,” compassion, and professionalism, but reliable, objective, and standardized assessment tools are not available. Currently our best tools are clinical evaluations which are subject to grade inflation and implicit racial and gender biases. Furthermore, other components of a residency application, such as letters of recommendation, Chair’s letters, and the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (Dean’s letter), are regarded to be less informative as schools move toward no student rankings, pass/fail grading schemes, and nonstandardized summative adjectives to describe medical students overall medical school performance.

Finally, medical student distress in the residency application process may stem from the perpetuation of elitism that extends from medical school to fellowship training and academic hospital medicine. Rankings of medical schools, residencies, fellowships, and hospitals serve to create a hierarchical system. Competitive residency applicants see admittance into the best training programs as opening doors to opportunities, while not getting into these programs is seen as closing doors to career paths and opportunities.

With this change in Step 1 score reporting, where do we as hospitalists fit in? Hospitalists are at the forefront of educating and evaluating medical students in academic medical centers, and we are often asked to write letters of recommendation and serve as mentors. If done well, these activities can have a positive impact on medical student applications to residency by alleviating some of the stresses and mitigating the downsides to the new Step 1 scoring system. Writing impactful letters and thoughtful evaluations are all skills that should be incorporated in hospitalist faculty development programs. Moreover, in order to serve as better advocates for our students, it is important that academic hospitalists understand the evolving landscape of the residency application process and are mindful of the stresses that medical students face. Changing Step 1 scoring to pass/fail will likely have unintended consequences for our medical students, and we as hospitalists must be ready to improve our knowledge and skills in order to continue to support and advocate for our medical students.

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York; Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Ricotta is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School; Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque; Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee.

References

1. United States Medical Licensing Examination (2020 Feb). Change to pass/fail score reporting for Step 1.

2. Slavin SJ and Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(9):1194‐6.

3. Pereira AG, Chelminski PR, et al. Application inflation for internal medicine applicants in the Match: Drivers, consequences, and potential solutions. Am J Med. 2016 Aug;129(8): 885-91.

The National Board of Medical Examiners recently announced a change in the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting from a 3-digit score to a pass/fail score beginning in 2022.1 Endorsed by a broad coalition of organizations involved in undergraduate (UME) and graduate medical education (GME), this change is intended as a first step toward systemic improvements in the UME-GME transition to residency by promoting holistic reviews of applicants. Additionally, it is meant to tackle widespread concerns about medical student distress brought about by the residency selection process. For example, switching to pass/fail preclinical curricula has resulted in an improvement in medical student well-being at many medical schools.2 It is the hope that a mirrored change in Step 1 may similarly improve mental health and encourage a growth mindset towards learning.

On the other hand, many residency programs rely on USMLE scores for screening potential candidates, especially as application inflation has burdened programs with thousands of applications.3 The change to a pass/fail Step 1 score will likely shift emphasis and stress to the Step 2 CK Exam, essentially negating the intended effect. Furthermore, for schools still reporting NBME Subject (shelf) Exam scores and Clerkship grades, there will likely be a greater emphasis placed on these metrics as well. The need for objective assessment methods are seen by many as so critical that some GME leaders have advocated for instituting entrance exams or requiring a Standardized Letter of Evaluation as a prerequisite to residency application. Finally, medical students jockeying for competitive residency positions may also feel pressured to distinguish themselves by boosting other aspects of their portfolio by taking a research year or applying for away electives, which risks marginalizing students of lesser means or with family responsibilities.

Ultimately, the change to a pass/fail Step 1 exam will likely do little to address the expanding gulf between the UME and GME communities. Residency program directors are searching for students with qualities of a good physician, such as interpersonal skills, “teamsmanship,” compassion, and professionalism, but reliable, objective, and standardized assessment tools are not available. Currently our best tools are clinical evaluations which are subject to grade inflation and implicit racial and gender biases. Furthermore, other components of a residency application, such as letters of recommendation, Chair’s letters, and the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (Dean’s letter), are regarded to be less informative as schools move toward no student rankings, pass/fail grading schemes, and nonstandardized summative adjectives to describe medical students overall medical school performance.

Finally, medical student distress in the residency application process may stem from the perpetuation of elitism that extends from medical school to fellowship training and academic hospital medicine. Rankings of medical schools, residencies, fellowships, and hospitals serve to create a hierarchical system. Competitive residency applicants see admittance into the best training programs as opening doors to opportunities, while not getting into these programs is seen as closing doors to career paths and opportunities.

With this change in Step 1 score reporting, where do we as hospitalists fit in? Hospitalists are at the forefront of educating and evaluating medical students in academic medical centers, and we are often asked to write letters of recommendation and serve as mentors. If done well, these activities can have a positive impact on medical student applications to residency by alleviating some of the stresses and mitigating the downsides to the new Step 1 scoring system. Writing impactful letters and thoughtful evaluations are all skills that should be incorporated in hospitalist faculty development programs. Moreover, in order to serve as better advocates for our students, it is important that academic hospitalists understand the evolving landscape of the residency application process and are mindful of the stresses that medical students face. Changing Step 1 scoring to pass/fail will likely have unintended consequences for our medical students, and we as hospitalists must be ready to improve our knowledge and skills in order to continue to support and advocate for our medical students.

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York; Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Ricotta is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School; Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque; Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee.

References

1. United States Medical Licensing Examination (2020 Feb). Change to pass/fail score reporting for Step 1.

2. Slavin SJ and Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(9):1194‐6.

3. Pereira AG, Chelminski PR, et al. Application inflation for internal medicine applicants in the Match: Drivers, consequences, and potential solutions. Am J Med. 2016 Aug;129(8): 885-91.

The National Board of Medical Examiners recently announced a change in the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting from a 3-digit score to a pass/fail score beginning in 2022.1 Endorsed by a broad coalition of organizations involved in undergraduate (UME) and graduate medical education (GME), this change is intended as a first step toward systemic improvements in the UME-GME transition to residency by promoting holistic reviews of applicants. Additionally, it is meant to tackle widespread concerns about medical student distress brought about by the residency selection process. For example, switching to pass/fail preclinical curricula has resulted in an improvement in medical student well-being at many medical schools.2 It is the hope that a mirrored change in Step 1 may similarly improve mental health and encourage a growth mindset towards learning.

On the other hand, many residency programs rely on USMLE scores for screening potential candidates, especially as application inflation has burdened programs with thousands of applications.3 The change to a pass/fail Step 1 score will likely shift emphasis and stress to the Step 2 CK Exam, essentially negating the intended effect. Furthermore, for schools still reporting NBME Subject (shelf) Exam scores and Clerkship grades, there will likely be a greater emphasis placed on these metrics as well. The need for objective assessment methods are seen by many as so critical that some GME leaders have advocated for instituting entrance exams or requiring a Standardized Letter of Evaluation as a prerequisite to residency application. Finally, medical students jockeying for competitive residency positions may also feel pressured to distinguish themselves by boosting other aspects of their portfolio by taking a research year or applying for away electives, which risks marginalizing students of lesser means or with family responsibilities.

Ultimately, the change to a pass/fail Step 1 exam will likely do little to address the expanding gulf between the UME and GME communities. Residency program directors are searching for students with qualities of a good physician, such as interpersonal skills, “teamsmanship,” compassion, and professionalism, but reliable, objective, and standardized assessment tools are not available. Currently our best tools are clinical evaluations which are subject to grade inflation and implicit racial and gender biases. Furthermore, other components of a residency application, such as letters of recommendation, Chair’s letters, and the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (Dean’s letter), are regarded to be less informative as schools move toward no student rankings, pass/fail grading schemes, and nonstandardized summative adjectives to describe medical students overall medical school performance.

Finally, medical student distress in the residency application process may stem from the perpetuation of elitism that extends from medical school to fellowship training and academic hospital medicine. Rankings of medical schools, residencies, fellowships, and hospitals serve to create a hierarchical system. Competitive residency applicants see admittance into the best training programs as opening doors to opportunities, while not getting into these programs is seen as closing doors to career paths and opportunities.

With this change in Step 1 score reporting, where do we as hospitalists fit in? Hospitalists are at the forefront of educating and evaluating medical students in academic medical centers, and we are often asked to write letters of recommendation and serve as mentors. If done well, these activities can have a positive impact on medical student applications to residency by alleviating some of the stresses and mitigating the downsides to the new Step 1 scoring system. Writing impactful letters and thoughtful evaluations are all skills that should be incorporated in hospitalist faculty development programs. Moreover, in order to serve as better advocates for our students, it is important that academic hospitalists understand the evolving landscape of the residency application process and are mindful of the stresses that medical students face. Changing Step 1 scoring to pass/fail will likely have unintended consequences for our medical students, and we as hospitalists must be ready to improve our knowledge and skills in order to continue to support and advocate for our medical students.

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York; Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Ricotta is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School; Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque; Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee.

References

1. United States Medical Licensing Examination (2020 Feb). Change to pass/fail score reporting for Step 1.

2. Slavin SJ and Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(9):1194‐6.

3. Pereira AG, Chelminski PR, et al. Application inflation for internal medicine applicants in the Match: Drivers, consequences, and potential solutions. Am J Med. 2016 Aug;129(8): 885-91.

New ASAM guideline released amid COVID-19 concerns

Home-based buprenorphine induction deemed safe for OUD

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has released an updated practice guideline for patients with opioid use disorder.

The guideline, called a focused update, advances ASAM’s 2015 National Practice Guidelines for the Treament of Opioid Use Disorder. “During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the associated need for social distancing, it is especially important that clinicians and health care providers across the country take steps to ensure that individuals with OUD can continue to receive evidence-based care,” said Paul H. Earley, MD, president of ASAM, in a press release announcing the new guideline.

The guideline specifies that home-based buprenorphine induction is safe and effective for treatment of opioid use disorder and that no individual entering the criminal justice system should be subjected to opioid withdrawal.

“The research is clear, providing methadone or buprenorphine, even without psychosocial treatment, reduces the patient’s risk of death,” said Kyle Kampman, MD, chair of the group’s Guideline Writing Committee, in the release. “Ultimately, keeping patients with the disease of addiction alive and engaged to become ready for recovery is absolutely critical in the context of the deadly overdose epidemic that has struck communities across our country.”

The society released this focused update to reflect new medications and formulations, published evidence, and clinical guidance related to treatment of OUD. This update includes the addition of 13 new recommendations and major revisions to 35 existing recommendations. One concern the society has is how to help patients being treated for OUD who are limited in their ability to leave their homes. Because of these same concerns, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration relaxed regulations on March 16 regarding patient eligibility for take-home medications, such as buprenorphine and methadone, which dovetails with the society’s guidance regarding home-based induction.

, continuing on to pharmacologic treatment even if the patient declines recommended psychosocial treatment, keeping naloxone kits available in correctional facilities, and more. Additional information about this update can be found on ASAM’s website.

Home-based buprenorphine induction deemed safe for OUD

Home-based buprenorphine induction deemed safe for OUD

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has released an updated practice guideline for patients with opioid use disorder.

The guideline, called a focused update, advances ASAM’s 2015 National Practice Guidelines for the Treament of Opioid Use Disorder. “During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the associated need for social distancing, it is especially important that clinicians and health care providers across the country take steps to ensure that individuals with OUD can continue to receive evidence-based care,” said Paul H. Earley, MD, president of ASAM, in a press release announcing the new guideline.

The guideline specifies that home-based buprenorphine induction is safe and effective for treatment of opioid use disorder and that no individual entering the criminal justice system should be subjected to opioid withdrawal.

“The research is clear, providing methadone or buprenorphine, even without psychosocial treatment, reduces the patient’s risk of death,” said Kyle Kampman, MD, chair of the group’s Guideline Writing Committee, in the release. “Ultimately, keeping patients with the disease of addiction alive and engaged to become ready for recovery is absolutely critical in the context of the deadly overdose epidemic that has struck communities across our country.”

The society released this focused update to reflect new medications and formulations, published evidence, and clinical guidance related to treatment of OUD. This update includes the addition of 13 new recommendations and major revisions to 35 existing recommendations. One concern the society has is how to help patients being treated for OUD who are limited in their ability to leave their homes. Because of these same concerns, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration relaxed regulations on March 16 regarding patient eligibility for take-home medications, such as buprenorphine and methadone, which dovetails with the society’s guidance regarding home-based induction.

, continuing on to pharmacologic treatment even if the patient declines recommended psychosocial treatment, keeping naloxone kits available in correctional facilities, and more. Additional information about this update can be found on ASAM’s website.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has released an updated practice guideline for patients with opioid use disorder.

The guideline, called a focused update, advances ASAM’s 2015 National Practice Guidelines for the Treament of Opioid Use Disorder. “During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the associated need for social distancing, it is especially important that clinicians and health care providers across the country take steps to ensure that individuals with OUD can continue to receive evidence-based care,” said Paul H. Earley, MD, president of ASAM, in a press release announcing the new guideline.

The guideline specifies that home-based buprenorphine induction is safe and effective for treatment of opioid use disorder and that no individual entering the criminal justice system should be subjected to opioid withdrawal.

“The research is clear, providing methadone or buprenorphine, even without psychosocial treatment, reduces the patient’s risk of death,” said Kyle Kampman, MD, chair of the group’s Guideline Writing Committee, in the release. “Ultimately, keeping patients with the disease of addiction alive and engaged to become ready for recovery is absolutely critical in the context of the deadly overdose epidemic that has struck communities across our country.”

The society released this focused update to reflect new medications and formulations, published evidence, and clinical guidance related to treatment of OUD. This update includes the addition of 13 new recommendations and major revisions to 35 existing recommendations. One concern the society has is how to help patients being treated for OUD who are limited in their ability to leave their homes. Because of these same concerns, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration relaxed regulations on March 16 regarding patient eligibility for take-home medications, such as buprenorphine and methadone, which dovetails with the society’s guidance regarding home-based induction.

, continuing on to pharmacologic treatment even if the patient declines recommended psychosocial treatment, keeping naloxone kits available in correctional facilities, and more. Additional information about this update can be found on ASAM’s website.

Designing an effective onboarding program

It goes beyond welcoming and orientation

As I gear up to welcome and onboard new hires to our hospitalist group, I could not help but reflect on my first day as a hospitalist. Fresh out of residency, my orientation was a day and a half long.

The medical director gave me a brief overview of the program. The program administrator handed me a thick folder of policies followed by a quick tour of the hospital and an afternoon training for the computerized order entry system (that was a time before EHRs). The next morning, I was given my full panel of patients, my new lab coat, and sent off into the battlefield.

I can vividly remember feeling anxious, a bit confused, and quite overwhelmed as I went through my day. The days turned into a week and the next. I kept wondering if I was doing everything right. It took me a month to feel a little more comfortable. It all turned out fine. Since nobody told me otherwise, I assumed it did.

Quite a bit has changed since then in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine groups, nowadays, have to tackle the changing landscape of payment reform, take on responsibility for an increasing range of hospital quality metrics and juggle a swath of subspecialty comanagement agreements. Hospital medicine providers function from the inpatient to the post-acute care arena, all while continuing to demonstrate their value to the hospital administration. Simultaneously, they have to ensure their providers are engaged and functioning at their optimal level while battling the ever-increasing threat of burnout.

Thus, for new hires, all the above aspects of my orientation have become critical but alas terribly insufficient. Well into its third decade, the hospital medicine job market continues to boom but remains a revolving door. Hospital medicine groups continue to grow in size and integrate across hospitals in a given health system. The vast majority of the new hires tend to be fresh out of residency. The first year remains the most vulnerable period for a new hospitalist. Hospital medicine groups must design and implement a robust onboarding program for their new hires. It goes beyond welcoming and orientation of new hires to full integration and assimilation in order to transform them into highly efficient and productive team members. Effective onboarding is table stakes for a successful and thriving hospital medicine group.

The content

An effective onboarding program should focus on three key dimensions: the organizational, the technical, and the social.1

1. The organizational or administrative aspect: The most common aspect of onboarding is providing new hires with information on the group’s policies and procedures: what to do and how to do it. Equally essential is giving them the tools and contacts that will help them understand and navigate their first few months. Information on how to contact consultants, signing on and off shifts, and so on can be easily conveyed through documents. However, having peers and the critical administrative staff communicate other aspects such as a detailed tour of the hospital, scheduling, and vacation policies is far more effective. It provides an excellent opportunity to introduce new hires to the key personnel in the group and vice versa as new hires get familiar with the unofficial workplace language. Breaking down all this information into meaningful, absorbable boluses, spread over time, is key to avoiding information overload. Allowing new hires to assimilate and adapt to the group norms requires follow-up and reinforcement. Group leaders should plan to meet with them at predetermined intervals, such as at 30, 60, 90 days, to engage them in conversations about the group’s values, performance measurements, rewards, and the opportunities for growth that exist within the group and institution.

2. The technical or the clinical aspect: The majority of physicians and advanced providers hired to a hospital medicine group have come immediately from training. Transition into the autonomous role of an attending, or a semi-autonomous role for advanced providers, with a larger patient panel can be quite unnerving and stressful. It can be disorientating even for experienced providers transitioning into a new health system. A well-structured onboarding can allow providers to deploy their training and experience at your organization effectively. Many onboarding programs have a clinical ramp-up period. The providers begin with a limited patient panel and gradually acclimatize into a full patient load. Many programs pair a senior hospitalist with the new hire during this period – a ‘buddy.’ Buddies are available to help new hires navigate the health system and familiarize them with the stakeholders. They help new hires by providing context to understand their new role and how they can contribute to the group’s success. In many instances, buddies help outline the unspoken rules of the group.

3. The social aspect – enculturation and networking: This is probably the most important of the three elements. It is quite common for new hires to feel like a stranger in a new land. A well-designed onboarding program provides new hires the space to forge relationships with each other and existing members of the hospital medicine team. Groups can do this in myriad ways – an informal welcome social, a meet and greet breakfast or lunch, in-person orientation when designing the administrative onboarding, and assignment of buddies or mentors during their clinical ramp-up period. It is all about providing a space to establish and nurture lasting relationships between the new hires and the group. When done well, this helps transform a group into a community. It also lays the groundwork to avoid stress and loneliness, some of the culprits that lead to physician burnout. It is through these interpersonal connections that new hires adapt to a hospital medicine group’s prevailing culture.

The personnel

Effective onboarding should be more than mere orientation. Group leaders should make an active attempt at understanding the core values and needs of the group. A good onboarding process assists new hires to internalize and accept the norms of the group. This process is not just a result of what comes from top management but also what they see and hear from the rank and file providers in the group. Hence it is critical to have the right people who understand and embody these values at the planning table. It is equally essential that necessary time and resources are devoted to building a program that meets the needs of the group. The practice management committee at SHM interviewed five different programs across a spectrum of settings. All of them had a designated onboarding program leader with a planning committee that included the administrative staff and senior frontline hospitalists.

The costs

According to one estimate, the cost of physician turnover is $400,000-$600,000 per provider.2 Given such staggering costs, it is not difficult to justify the financial resources required to structure an effective onboarding program. Activities such as a detailed facility tour, a welcome breakfast, and a peer buddy system cost virtually nothing. They go a long way in building comradery, make new hires feel like they are part of a team, and reduce burnout and turnover. Costs of an onboarding program are typically related to wages during shadowing and clinical ramp-up. However, all the programs we interviewed acknowledged that the costs associated with onboarding, in the broader context, were small and necessary.

The bottom line

An effective onboarding program that is well planned, well structured, and well executed is inherently valuable. It sends a positive signal to new hires, reassuring them that they made a great decision by joining the group. It also reminds the existing providers why they want to be a part of the group and its culture.

It is not about what is said or done during the onboarding process or how long it lasts. It need not be overly complicated. It is how the process makes everyone feel about the group. At the end of the day, like in all aspects of life, that is what ultimately matters.

The SHM Practice Management Committee has created a document that outlines the guiding principles for effective onboarding with attached case studies. Visit the SHM website for more information: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org.

Dr. Irani is a hospitalist affiliated with Baystate Health in Springfield, Mass. He would like to thank Joshua Lapps, Luke Heisenger, and all the members of the SHM Practice Management Committee for their assistance and input in drafting the guiding principles of onboarding and the case studies that have heavily inspired the above article.

References

1. Carucci R. To Retain New Hires, Spend More Time Onboarding Them. Harvard Busines Review. Dec 3, 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/12/to-retain-new-hires-spend-more-time-onboarding-them

2. Franz D. The staggering costs of physician turnover. Today’s Hospitalist. August 2016. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/staggering-costs-physician-turnover/

It goes beyond welcoming and orientation

It goes beyond welcoming and orientation

As I gear up to welcome and onboard new hires to our hospitalist group, I could not help but reflect on my first day as a hospitalist. Fresh out of residency, my orientation was a day and a half long.

The medical director gave me a brief overview of the program. The program administrator handed me a thick folder of policies followed by a quick tour of the hospital and an afternoon training for the computerized order entry system (that was a time before EHRs). The next morning, I was given my full panel of patients, my new lab coat, and sent off into the battlefield.

I can vividly remember feeling anxious, a bit confused, and quite overwhelmed as I went through my day. The days turned into a week and the next. I kept wondering if I was doing everything right. It took me a month to feel a little more comfortable. It all turned out fine. Since nobody told me otherwise, I assumed it did.

Quite a bit has changed since then in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine groups, nowadays, have to tackle the changing landscape of payment reform, take on responsibility for an increasing range of hospital quality metrics and juggle a swath of subspecialty comanagement agreements. Hospital medicine providers function from the inpatient to the post-acute care arena, all while continuing to demonstrate their value to the hospital administration. Simultaneously, they have to ensure their providers are engaged and functioning at their optimal level while battling the ever-increasing threat of burnout.

Thus, for new hires, all the above aspects of my orientation have become critical but alas terribly insufficient. Well into its third decade, the hospital medicine job market continues to boom but remains a revolving door. Hospital medicine groups continue to grow in size and integrate across hospitals in a given health system. The vast majority of the new hires tend to be fresh out of residency. The first year remains the most vulnerable period for a new hospitalist. Hospital medicine groups must design and implement a robust onboarding program for their new hires. It goes beyond welcoming and orientation of new hires to full integration and assimilation in order to transform them into highly efficient and productive team members. Effective onboarding is table stakes for a successful and thriving hospital medicine group.

The content

An effective onboarding program should focus on three key dimensions: the organizational, the technical, and the social.1

1. The organizational or administrative aspect: The most common aspect of onboarding is providing new hires with information on the group’s policies and procedures: what to do and how to do it. Equally essential is giving them the tools and contacts that will help them understand and navigate their first few months. Information on how to contact consultants, signing on and off shifts, and so on can be easily conveyed through documents. However, having peers and the critical administrative staff communicate other aspects such as a detailed tour of the hospital, scheduling, and vacation policies is far more effective. It provides an excellent opportunity to introduce new hires to the key personnel in the group and vice versa as new hires get familiar with the unofficial workplace language. Breaking down all this information into meaningful, absorbable boluses, spread over time, is key to avoiding information overload. Allowing new hires to assimilate and adapt to the group norms requires follow-up and reinforcement. Group leaders should plan to meet with them at predetermined intervals, such as at 30, 60, 90 days, to engage them in conversations about the group’s values, performance measurements, rewards, and the opportunities for growth that exist within the group and institution.

2. The technical or the clinical aspect: The majority of physicians and advanced providers hired to a hospital medicine group have come immediately from training. Transition into the autonomous role of an attending, or a semi-autonomous role for advanced providers, with a larger patient panel can be quite unnerving and stressful. It can be disorientating even for experienced providers transitioning into a new health system. A well-structured onboarding can allow providers to deploy their training and experience at your organization effectively. Many onboarding programs have a clinical ramp-up period. The providers begin with a limited patient panel and gradually acclimatize into a full patient load. Many programs pair a senior hospitalist with the new hire during this period – a ‘buddy.’ Buddies are available to help new hires navigate the health system and familiarize them with the stakeholders. They help new hires by providing context to understand their new role and how they can contribute to the group’s success. In many instances, buddies help outline the unspoken rules of the group.

3. The social aspect – enculturation and networking: This is probably the most important of the three elements. It is quite common for new hires to feel like a stranger in a new land. A well-designed onboarding program provides new hires the space to forge relationships with each other and existing members of the hospital medicine team. Groups can do this in myriad ways – an informal welcome social, a meet and greet breakfast or lunch, in-person orientation when designing the administrative onboarding, and assignment of buddies or mentors during their clinical ramp-up period. It is all about providing a space to establish and nurture lasting relationships between the new hires and the group. When done well, this helps transform a group into a community. It also lays the groundwork to avoid stress and loneliness, some of the culprits that lead to physician burnout. It is through these interpersonal connections that new hires adapt to a hospital medicine group’s prevailing culture.

The personnel

Effective onboarding should be more than mere orientation. Group leaders should make an active attempt at understanding the core values and needs of the group. A good onboarding process assists new hires to internalize and accept the norms of the group. This process is not just a result of what comes from top management but also what they see and hear from the rank and file providers in the group. Hence it is critical to have the right people who understand and embody these values at the planning table. It is equally essential that necessary time and resources are devoted to building a program that meets the needs of the group. The practice management committee at SHM interviewed five different programs across a spectrum of settings. All of them had a designated onboarding program leader with a planning committee that included the administrative staff and senior frontline hospitalists.

The costs

According to one estimate, the cost of physician turnover is $400,000-$600,000 per provider.2 Given such staggering costs, it is not difficult to justify the financial resources required to structure an effective onboarding program. Activities such as a detailed facility tour, a welcome breakfast, and a peer buddy system cost virtually nothing. They go a long way in building comradery, make new hires feel like they are part of a team, and reduce burnout and turnover. Costs of an onboarding program are typically related to wages during shadowing and clinical ramp-up. However, all the programs we interviewed acknowledged that the costs associated with onboarding, in the broader context, were small and necessary.

The bottom line

An effective onboarding program that is well planned, well structured, and well executed is inherently valuable. It sends a positive signal to new hires, reassuring them that they made a great decision by joining the group. It also reminds the existing providers why they want to be a part of the group and its culture.

It is not about what is said or done during the onboarding process or how long it lasts. It need not be overly complicated. It is how the process makes everyone feel about the group. At the end of the day, like in all aspects of life, that is what ultimately matters.

The SHM Practice Management Committee has created a document that outlines the guiding principles for effective onboarding with attached case studies. Visit the SHM website for more information: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org.

Dr. Irani is a hospitalist affiliated with Baystate Health in Springfield, Mass. He would like to thank Joshua Lapps, Luke Heisenger, and all the members of the SHM Practice Management Committee for their assistance and input in drafting the guiding principles of onboarding and the case studies that have heavily inspired the above article.

References

1. Carucci R. To Retain New Hires, Spend More Time Onboarding Them. Harvard Busines Review. Dec 3, 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/12/to-retain-new-hires-spend-more-time-onboarding-them

2. Franz D. The staggering costs of physician turnover. Today’s Hospitalist. August 2016. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/staggering-costs-physician-turnover/

As I gear up to welcome and onboard new hires to our hospitalist group, I could not help but reflect on my first day as a hospitalist. Fresh out of residency, my orientation was a day and a half long.

The medical director gave me a brief overview of the program. The program administrator handed me a thick folder of policies followed by a quick tour of the hospital and an afternoon training for the computerized order entry system (that was a time before EHRs). The next morning, I was given my full panel of patients, my new lab coat, and sent off into the battlefield.

I can vividly remember feeling anxious, a bit confused, and quite overwhelmed as I went through my day. The days turned into a week and the next. I kept wondering if I was doing everything right. It took me a month to feel a little more comfortable. It all turned out fine. Since nobody told me otherwise, I assumed it did.

Quite a bit has changed since then in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine groups, nowadays, have to tackle the changing landscape of payment reform, take on responsibility for an increasing range of hospital quality metrics and juggle a swath of subspecialty comanagement agreements. Hospital medicine providers function from the inpatient to the post-acute care arena, all while continuing to demonstrate their value to the hospital administration. Simultaneously, they have to ensure their providers are engaged and functioning at their optimal level while battling the ever-increasing threat of burnout.

Thus, for new hires, all the above aspects of my orientation have become critical but alas terribly insufficient. Well into its third decade, the hospital medicine job market continues to boom but remains a revolving door. Hospital medicine groups continue to grow in size and integrate across hospitals in a given health system. The vast majority of the new hires tend to be fresh out of residency. The first year remains the most vulnerable period for a new hospitalist. Hospital medicine groups must design and implement a robust onboarding program for their new hires. It goes beyond welcoming and orientation of new hires to full integration and assimilation in order to transform them into highly efficient and productive team members. Effective onboarding is table stakes for a successful and thriving hospital medicine group.

The content

An effective onboarding program should focus on three key dimensions: the organizational, the technical, and the social.1

1. The organizational or administrative aspect: The most common aspect of onboarding is providing new hires with information on the group’s policies and procedures: what to do and how to do it. Equally essential is giving them the tools and contacts that will help them understand and navigate their first few months. Information on how to contact consultants, signing on and off shifts, and so on can be easily conveyed through documents. However, having peers and the critical administrative staff communicate other aspects such as a detailed tour of the hospital, scheduling, and vacation policies is far more effective. It provides an excellent opportunity to introduce new hires to the key personnel in the group and vice versa as new hires get familiar with the unofficial workplace language. Breaking down all this information into meaningful, absorbable boluses, spread over time, is key to avoiding information overload. Allowing new hires to assimilate and adapt to the group norms requires follow-up and reinforcement. Group leaders should plan to meet with them at predetermined intervals, such as at 30, 60, 90 days, to engage them in conversations about the group’s values, performance measurements, rewards, and the opportunities for growth that exist within the group and institution.

2. The technical or the clinical aspect: The majority of physicians and advanced providers hired to a hospital medicine group have come immediately from training. Transition into the autonomous role of an attending, or a semi-autonomous role for advanced providers, with a larger patient panel can be quite unnerving and stressful. It can be disorientating even for experienced providers transitioning into a new health system. A well-structured onboarding can allow providers to deploy their training and experience at your organization effectively. Many onboarding programs have a clinical ramp-up period. The providers begin with a limited patient panel and gradually acclimatize into a full patient load. Many programs pair a senior hospitalist with the new hire during this period – a ‘buddy.’ Buddies are available to help new hires navigate the health system and familiarize them with the stakeholders. They help new hires by providing context to understand their new role and how they can contribute to the group’s success. In many instances, buddies help outline the unspoken rules of the group.

3. The social aspect – enculturation and networking: This is probably the most important of the three elements. It is quite common for new hires to feel like a stranger in a new land. A well-designed onboarding program provides new hires the space to forge relationships with each other and existing members of the hospital medicine team. Groups can do this in myriad ways – an informal welcome social, a meet and greet breakfast or lunch, in-person orientation when designing the administrative onboarding, and assignment of buddies or mentors during their clinical ramp-up period. It is all about providing a space to establish and nurture lasting relationships between the new hires and the group. When done well, this helps transform a group into a community. It also lays the groundwork to avoid stress and loneliness, some of the culprits that lead to physician burnout. It is through these interpersonal connections that new hires adapt to a hospital medicine group’s prevailing culture.

The personnel

Effective onboarding should be more than mere orientation. Group leaders should make an active attempt at understanding the core values and needs of the group. A good onboarding process assists new hires to internalize and accept the norms of the group. This process is not just a result of what comes from top management but also what they see and hear from the rank and file providers in the group. Hence it is critical to have the right people who understand and embody these values at the planning table. It is equally essential that necessary time and resources are devoted to building a program that meets the needs of the group. The practice management committee at SHM interviewed five different programs across a spectrum of settings. All of them had a designated onboarding program leader with a planning committee that included the administrative staff and senior frontline hospitalists.

The costs

According to one estimate, the cost of physician turnover is $400,000-$600,000 per provider.2 Given such staggering costs, it is not difficult to justify the financial resources required to structure an effective onboarding program. Activities such as a detailed facility tour, a welcome breakfast, and a peer buddy system cost virtually nothing. They go a long way in building comradery, make new hires feel like they are part of a team, and reduce burnout and turnover. Costs of an onboarding program are typically related to wages during shadowing and clinical ramp-up. However, all the programs we interviewed acknowledged that the costs associated with onboarding, in the broader context, were small and necessary.

The bottom line

An effective onboarding program that is well planned, well structured, and well executed is inherently valuable. It sends a positive signal to new hires, reassuring them that they made a great decision by joining the group. It also reminds the existing providers why they want to be a part of the group and its culture.

It is not about what is said or done during the onboarding process or how long it lasts. It need not be overly complicated. It is how the process makes everyone feel about the group. At the end of the day, like in all aspects of life, that is what ultimately matters.

The SHM Practice Management Committee has created a document that outlines the guiding principles for effective onboarding with attached case studies. Visit the SHM website for more information: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org.

Dr. Irani is a hospitalist affiliated with Baystate Health in Springfield, Mass. He would like to thank Joshua Lapps, Luke Heisenger, and all the members of the SHM Practice Management Committee for their assistance and input in drafting the guiding principles of onboarding and the case studies that have heavily inspired the above article.

References

1. Carucci R. To Retain New Hires, Spend More Time Onboarding Them. Harvard Busines Review. Dec 3, 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/12/to-retain-new-hires-spend-more-time-onboarding-them

2. Franz D. The staggering costs of physician turnover. Today’s Hospitalist. August 2016. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/staggering-costs-physician-turnover/

ACP outlines guide for COVID-19 telehealth coding, billing

and for handling clinician and staff absences due to illness or quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It strongly encourages practices to use telehealth, whenever possible, to mitigate exposure of patients who are sick or at risk because of other underlying conditions and to protect health care workers and the community from the spread of the disease.

The national organization of internists also recommends in the guidance that practices establish protocols and procedures for use by clinicians and all other staff in light of the pandemic.

The billing and coding tips are being offered to help practices deal with the rapidly changing situation surrounding the COVID-19 emergency, according to a statement from the ACP.

The coding-related guidance incorporates changes to a number of telehealth rules for Medicare beneficiaries, announced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on March 17.

“Now in a full state of emergency, many Medicare restrictions related to telehealth have been lifted. Patients can be at home, and non-HIPAA compliant technology is allowed. There is no cost sharing for COVID-19 testing. In addition, to encourage use by patients, Medicare is allowing practices to waive cost sharing (copays and deductibles) for all telehealth services,” the organization said in the guidance. It notes, however, that the CMS does not currently reimburse for telephone calls.

The guidance includes details of the new ICD-10 codes, and stresses the importance of using the appropriate codes, given that some service cost-sharing has been waived for COVID-19 testing and treatment.

There is detailed coding guidance for virtual check-in, online evaluation and management, remote monitoring, originating site, and allowed technology and services.

In regard to clinician and staff absence due to illness or quarantine, the ACP says “practices may need to review emergency plans related to telework and to employee and clinician absence.” Among its recommendations are that practices and employers consider temporary adjustments to compensation formulas to accommodate those clinicians who experience a loss of income because they are paid based on production.

The organization emphasizes that, given the rapidly changing availability of testing for COVID-19, practices should contact their local health departments, hospitals, reference labs, or state health authorities to determine the status of their access to testing.

The full list of the ACP’s tips are available here.

Any new guidance for physicians will be posted on the ACP’s COVID-19 resource page.

and for handling clinician and staff absences due to illness or quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It strongly encourages practices to use telehealth, whenever possible, to mitigate exposure of patients who are sick or at risk because of other underlying conditions and to protect health care workers and the community from the spread of the disease.

The national organization of internists also recommends in the guidance that practices establish protocols and procedures for use by clinicians and all other staff in light of the pandemic.

The billing and coding tips are being offered to help practices deal with the rapidly changing situation surrounding the COVID-19 emergency, according to a statement from the ACP.

The coding-related guidance incorporates changes to a number of telehealth rules for Medicare beneficiaries, announced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on March 17.

“Now in a full state of emergency, many Medicare restrictions related to telehealth have been lifted. Patients can be at home, and non-HIPAA compliant technology is allowed. There is no cost sharing for COVID-19 testing. In addition, to encourage use by patients, Medicare is allowing practices to waive cost sharing (copays and deductibles) for all telehealth services,” the organization said in the guidance. It notes, however, that the CMS does not currently reimburse for telephone calls.

The guidance includes details of the new ICD-10 codes, and stresses the importance of using the appropriate codes, given that some service cost-sharing has been waived for COVID-19 testing and treatment.

There is detailed coding guidance for virtual check-in, online evaluation and management, remote monitoring, originating site, and allowed technology and services.

In regard to clinician and staff absence due to illness or quarantine, the ACP says “practices may need to review emergency plans related to telework and to employee and clinician absence.” Among its recommendations are that practices and employers consider temporary adjustments to compensation formulas to accommodate those clinicians who experience a loss of income because they are paid based on production.

The organization emphasizes that, given the rapidly changing availability of testing for COVID-19, practices should contact their local health departments, hospitals, reference labs, or state health authorities to determine the status of their access to testing.

The full list of the ACP’s tips are available here.

Any new guidance for physicians will be posted on the ACP’s COVID-19 resource page.

and for handling clinician and staff absences due to illness or quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It strongly encourages practices to use telehealth, whenever possible, to mitigate exposure of patients who are sick or at risk because of other underlying conditions and to protect health care workers and the community from the spread of the disease.

The national organization of internists also recommends in the guidance that practices establish protocols and procedures for use by clinicians and all other staff in light of the pandemic.

The billing and coding tips are being offered to help practices deal with the rapidly changing situation surrounding the COVID-19 emergency, according to a statement from the ACP.

The coding-related guidance incorporates changes to a number of telehealth rules for Medicare beneficiaries, announced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on March 17.

“Now in a full state of emergency, many Medicare restrictions related to telehealth have been lifted. Patients can be at home, and non-HIPAA compliant technology is allowed. There is no cost sharing for COVID-19 testing. In addition, to encourage use by patients, Medicare is allowing practices to waive cost sharing (copays and deductibles) for all telehealth services,” the organization said in the guidance. It notes, however, that the CMS does not currently reimburse for telephone calls.

The guidance includes details of the new ICD-10 codes, and stresses the importance of using the appropriate codes, given that some service cost-sharing has been waived for COVID-19 testing and treatment.

There is detailed coding guidance for virtual check-in, online evaluation and management, remote monitoring, originating site, and allowed technology and services.

In regard to clinician and staff absence due to illness or quarantine, the ACP says “practices may need to review emergency plans related to telework and to employee and clinician absence.” Among its recommendations are that practices and employers consider temporary adjustments to compensation formulas to accommodate those clinicians who experience a loss of income because they are paid based on production.

The organization emphasizes that, given the rapidly changing availability of testing for COVID-19, practices should contact their local health departments, hospitals, reference labs, or state health authorities to determine the status of their access to testing.

The full list of the ACP’s tips are available here.

Any new guidance for physicians will be posted on the ACP’s COVID-19 resource page.

Physicians and health systems can reduce fear around COVID-19

A message from a Chief Wellness Officer

We are at a time, unfortunately, of significant public uncertainty and fear of “the coronavirus.” Mixed and inaccurate messages from national leaders in the setting of delayed testing availability have heightened fears and impeded a uniformity in responses, medical and preventive.

Despite this, physicians, nurses, and other health professionals across the country, and in many other countries, have been addressing the medical realities of this pandemic in a way that should make every one of us health professionals proud – from the Chinese doctors and nurses to the Italian intensivists and primary care physicians throughout many countries who have treated patients suffering from, or fearful of, a novel disease with uncertain transmission characteristics and unpredictable clinical outcomes.

It is now time for physicians and other health providers in the United States to step up to the plate and model appropriate transmission-reducing behavior for the general public. This will help reduce the overall morbidity and mortality associated with this pandemic and let us return to a more normal lifestyle as soon as possible. Physicians need to be reassuring but realistic, and there are concrete steps that we can take to demonstrate to the general public that there is a way forward.

First the basic facts. The United States does not have enough intensive care beds or ventilators to handle a major pandemic. We will also have insufficient physicians and nurses if many are quarantined. The tragic experience in Italy, where patients are dying from lack of ventilators, intensive care facilities, and staff, must not be repeated here.

Many health systems are canceling or reducing outpatient appointments and increasingly using video and other telehealth technologies, especially for assessing and triaging people who believe that they may have become infected and are relatively asymptomatic. While all of the disruptions may seem unsettling, they are actually good news for those of us in healthcare. Efforts to “flatten the curve” will slow the infection spread and help us better manage patients who become critical.

So, what can physicians do?

- Make sure you are getting good information about the situation. Access reliable information and data that are widely available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health Organization. Listen to professional news organizations, local and national. Pass this information to your patients and community.

- Obviously, when practicing clinically, follow all infection control protocols, which will inevitably change over time. Make it clear to your patients why you are following these protocols and procedures.

- Support and actively promote the public health responses to this pandemic. Systematic reviews of the evidence base have found that isolating ill persons, testing and tracing contacts, quarantining exposed persons, closing schools and workplaces, and avoiding crowding are more effective if implemented immediately, simultaneously (ie, school closures combined with teleworking for parents), and with high community compliance.

- Practice social distancing so that you remain as much in control as you can. This will make you feel psychologically better and safer, as well as reduce the risk for transmission. Take the essential precautionary measures that we are all being asked to take. Wash your hands. Do not shake hands. Clean shared items. Do not go to large public gatherings. Minimize large group travel as much as you can. Use video to see your patients or your own doctor.

- Connect and reconnect with people you trust and love. See your family, your partner, your children, your friends. Speak to them on the phone and nourish those relationships. See how they feel and care for each other. They will be worried about you. Reassure them. Be in the moment with them and use the importance of these relationships to give yourself a chance not to overthink any fears you might have.

- Look after yourself physically. Physical fitness is good for your mental health. While White House guidelines suggest avoiding gyms, you can still enjoy long walks and outdoor activities. Take the weekend off and don’t work excessively. Sleep well – at least 7-8 hours. which has a series of really excellent meditation and relaxation tools.

- Do not panic. Uncertainty surrounding the pandemic makes all of us anxious and afraid. It is normal to become hypervigilant, especially with our nonstop media. It is normal to be concerned when we feel out of control and when we are hearing about a possible future catastrophe, especially when fed with differing sets of information from multiple sources and countries.

- Be careful with any large decisions you are making that may affect the lives of yourself and your loved ones. Think about your decisions and try to take the long view; and run them by your spouse, partner, or friends. This is not a time to be making sudden big decisions that may be driven unconsciously, in part at least, by fear and anxiety.

- Realize that all of these societal disruptions are actually good for us in health care, and they help your family and friends understand the importance of slowing the disease’s spread. That’s good for health care and good for everyone.

Finally, remember that “this is what we do,” to quote Doug Kirk, MD, chief medical officer of UC Davis Health. We must look after our patients. But we also have to look after ourselves so that we can look after our patients. We should all be proud of our work and our caring. And we should model our personal behavior to our patients and to our families and friends so that they will model it to their community networks. That way, more people will keep well, and we will have more chance of “flattening the curve” and reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

Peter M. Yellowlees, MBBS, MD, is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, Davis. He is a longtime Medscape contributor.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A message from a Chief Wellness Officer

We are at a time, unfortunately, of significant public uncertainty and fear of “the coronavirus.” Mixed and inaccurate messages from national leaders in the setting of delayed testing availability have heightened fears and impeded a uniformity in responses, medical and preventive.

Despite this, physicians, nurses, and other health professionals across the country, and in many other countries, have been addressing the medical realities of this pandemic in a way that should make every one of us health professionals proud – from the Chinese doctors and nurses to the Italian intensivists and primary care physicians throughout many countries who have treated patients suffering from, or fearful of, a novel disease with uncertain transmission characteristics and unpredictable clinical outcomes.

It is now time for physicians and other health providers in the United States to step up to the plate and model appropriate transmission-reducing behavior for the general public. This will help reduce the overall morbidity and mortality associated with this pandemic and let us return to a more normal lifestyle as soon as possible. Physicians need to be reassuring but realistic, and there are concrete steps that we can take to demonstrate to the general public that there is a way forward.

First the basic facts. The United States does not have enough intensive care beds or ventilators to handle a major pandemic. We will also have insufficient physicians and nurses if many are quarantined. The tragic experience in Italy, where patients are dying from lack of ventilators, intensive care facilities, and staff, must not be repeated here.

Many health systems are canceling or reducing outpatient appointments and increasingly using video and other telehealth technologies, especially for assessing and triaging people who believe that they may have become infected and are relatively asymptomatic. While all of the disruptions may seem unsettling, they are actually good news for those of us in healthcare. Efforts to “flatten the curve” will slow the infection spread and help us better manage patients who become critical.

So, what can physicians do?

- Make sure you are getting good information about the situation. Access reliable information and data that are widely available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health Organization. Listen to professional news organizations, local and national. Pass this information to your patients and community.

- Obviously, when practicing clinically, follow all infection control protocols, which will inevitably change over time. Make it clear to your patients why you are following these protocols and procedures.

- Support and actively promote the public health responses to this pandemic. Systematic reviews of the evidence base have found that isolating ill persons, testing and tracing contacts, quarantining exposed persons, closing schools and workplaces, and avoiding crowding are more effective if implemented immediately, simultaneously (ie, school closures combined with teleworking for parents), and with high community compliance.

- Practice social distancing so that you remain as much in control as you can. This will make you feel psychologically better and safer, as well as reduce the risk for transmission. Take the essential precautionary measures that we are all being asked to take. Wash your hands. Do not shake hands. Clean shared items. Do not go to large public gatherings. Minimize large group travel as much as you can. Use video to see your patients or your own doctor.

- Connect and reconnect with people you trust and love. See your family, your partner, your children, your friends. Speak to them on the phone and nourish those relationships. See how they feel and care for each other. They will be worried about you. Reassure them. Be in the moment with them and use the importance of these relationships to give yourself a chance not to overthink any fears you might have.

- Look after yourself physically. Physical fitness is good for your mental health. While White House guidelines suggest avoiding gyms, you can still enjoy long walks and outdoor activities. Take the weekend off and don’t work excessively. Sleep well – at least 7-8 hours. which has a series of really excellent meditation and relaxation tools.

- Do not panic. Uncertainty surrounding the pandemic makes all of us anxious and afraid. It is normal to become hypervigilant, especially with our nonstop media. It is normal to be concerned when we feel out of control and when we are hearing about a possible future catastrophe, especially when fed with differing sets of information from multiple sources and countries.

- Be careful with any large decisions you are making that may affect the lives of yourself and your loved ones. Think about your decisions and try to take the long view; and run them by your spouse, partner, or friends. This is not a time to be making sudden big decisions that may be driven unconsciously, in part at least, by fear and anxiety.

- Realize that all of these societal disruptions are actually good for us in health care, and they help your family and friends understand the importance of slowing the disease’s spread. That’s good for health care and good for everyone.

Finally, remember that “this is what we do,” to quote Doug Kirk, MD, chief medical officer of UC Davis Health. We must look after our patients. But we also have to look after ourselves so that we can look after our patients. We should all be proud of our work and our caring. And we should model our personal behavior to our patients and to our families and friends so that they will model it to their community networks. That way, more people will keep well, and we will have more chance of “flattening the curve” and reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

Peter M. Yellowlees, MBBS, MD, is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, Davis. He is a longtime Medscape contributor.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A message from a Chief Wellness Officer

We are at a time, unfortunately, of significant public uncertainty and fear of “the coronavirus.” Mixed and inaccurate messages from national leaders in the setting of delayed testing availability have heightened fears and impeded a uniformity in responses, medical and preventive.

Despite this, physicians, nurses, and other health professionals across the country, and in many other countries, have been addressing the medical realities of this pandemic in a way that should make every one of us health professionals proud – from the Chinese doctors and nurses to the Italian intensivists and primary care physicians throughout many countries who have treated patients suffering from, or fearful of, a novel disease with uncertain transmission characteristics and unpredictable clinical outcomes.

It is now time for physicians and other health providers in the United States to step up to the plate and model appropriate transmission-reducing behavior for the general public. This will help reduce the overall morbidity and mortality associated with this pandemic and let us return to a more normal lifestyle as soon as possible. Physicians need to be reassuring but realistic, and there are concrete steps that we can take to demonstrate to the general public that there is a way forward.

First the basic facts. The United States does not have enough intensive care beds or ventilators to handle a major pandemic. We will also have insufficient physicians and nurses if many are quarantined. The tragic experience in Italy, where patients are dying from lack of ventilators, intensive care facilities, and staff, must not be repeated here.

Many health systems are canceling or reducing outpatient appointments and increasingly using video and other telehealth technologies, especially for assessing and triaging people who believe that they may have become infected and are relatively asymptomatic. While all of the disruptions may seem unsettling, they are actually good news for those of us in healthcare. Efforts to “flatten the curve” will slow the infection spread and help us better manage patients who become critical.

So, what can physicians do?

- Make sure you are getting good information about the situation. Access reliable information and data that are widely available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health Organization. Listen to professional news organizations, local and national. Pass this information to your patients and community.

- Obviously, when practicing clinically, follow all infection control protocols, which will inevitably change over time. Make it clear to your patients why you are following these protocols and procedures.

- Support and actively promote the public health responses to this pandemic. Systematic reviews of the evidence base have found that isolating ill persons, testing and tracing contacts, quarantining exposed persons, closing schools and workplaces, and avoiding crowding are more effective if implemented immediately, simultaneously (ie, school closures combined with teleworking for parents), and with high community compliance.

- Practice social distancing so that you remain as much in control as you can. This will make you feel psychologically better and safer, as well as reduce the risk for transmission. Take the essential precautionary measures that we are all being asked to take. Wash your hands. Do not shake hands. Clean shared items. Do not go to large public gatherings. Minimize large group travel as much as you can. Use video to see your patients or your own doctor.

- Connect and reconnect with people you trust and love. See your family, your partner, your children, your friends. Speak to them on the phone and nourish those relationships. See how they feel and care for each other. They will be worried about you. Reassure them. Be in the moment with them and use the importance of these relationships to give yourself a chance not to overthink any fears you might have.

- Look after yourself physically. Physical fitness is good for your mental health. While White House guidelines suggest avoiding gyms, you can still enjoy long walks and outdoor activities. Take the weekend off and don’t work excessively. Sleep well – at least 7-8 hours. which has a series of really excellent meditation and relaxation tools.

- Do not panic. Uncertainty surrounding the pandemic makes all of us anxious and afraid. It is normal to become hypervigilant, especially with our nonstop media. It is normal to be concerned when we feel out of control and when we are hearing about a possible future catastrophe, especially when fed with differing sets of information from multiple sources and countries.

- Be careful with any large decisions you are making that may affect the lives of yourself and your loved ones. Think about your decisions and try to take the long view; and run them by your spouse, partner, or friends. This is not a time to be making sudden big decisions that may be driven unconsciously, in part at least, by fear and anxiety.

- Realize that all of these societal disruptions are actually good for us in health care, and they help your family and friends understand the importance of slowing the disease’s spread. That’s good for health care and good for everyone.

Finally, remember that “this is what we do,” to quote Doug Kirk, MD, chief medical officer of UC Davis Health. We must look after our patients. But we also have to look after ourselves so that we can look after our patients. We should all be proud of our work and our caring. And we should model our personal behavior to our patients and to our families and friends so that they will model it to their community networks. That way, more people will keep well, and we will have more chance of “flattening the curve” and reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

Peter M. Yellowlees, MBBS, MD, is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, Davis. He is a longtime Medscape contributor.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital medicine physician leaders

The right skills and time to develop them

“When you get someone who knows what quality looks like and pair that with curiosity about new ways to think about leading, you end up with the people who are able to produce dramatic innovations in the field.”1

In medicine, a physician is trained to take charge in emergent situations and make potentially lifesaving efforts. However, when it comes to leading teams of individuals, not only must successful leaders have the right skills, they also need time to dedicate to the work of leadership.

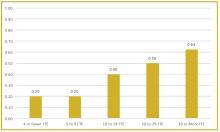

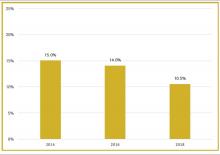

To better understand current approaches to dedicated hospital medicine group (HMG) leadership time, let’s examine the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report. The survey, upon which the Report was based, examined two aspects of leadership: 1) how much dedicated time a leader receives to manage the group; and 2) how the leader’s time is compensated. Looking closely at the data displayed in graphs from the SoHM Report (Figures 1, 2, and 3), we can see that dedicated administrative time is directly proportional to the size of the group.