User login

HM16 Session Analysis: Medical, Behavioral Management of Eating Disorders

Presenter: Kyung E. Rhee, MD, MSc, MA

Summary: Eating disorders (ED) are common and have significant morbidity and mortality. EDs are the third most common psychiatric disorder of adolescents with a prevalence of 0.5-2% for anorexia and 0.9-3% for bulimia; 90% of patients are female. Mortality rate can be as high as 10% for anorexia and 1% for bulimia. Diagnosis is formally guided by DSM 5 criteria, but the mnemonic SCOFF can be useful:

- Do you feel or make yourself SICK when eating?

- Do you feel you’ve lost CONTROL of your eating?

- Have you lost one STONE (14 lbs. developed by the British) of weight?

- Do you feel FAT?

- Does FOOD dominate your life?

A detailed history is needed as patients with ED may engage in secretive behaviors to hide their illness. After diagnosis, treatment may be outpatient or inpatient. Medical issues hospitalists are likely to see with inpatients include re-feeding syndrome, various metabolic disturbances, secondary amenorrhea, sleep disturbances, and for patients with bulimia, evidence of dental or esophageal trauma from purging. Differential diagnoses include: IBD, thyroid disease, celiac, diabetes, and Addison’s disease.

Hospitalists’ role in treatment is as part of a multidisciplinary group to manage the medical complications. Inpatient management includes individual and group therapy, monitored group meals, daily blind weights, bathroom visits, and focused lab studies. There is no “cure” and only ~50% of patients are free of ongoing symptoms after treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Eating disorders are common in adolescent females and have significant morbidity and mortality.

- Hospitalists’ role is diagnosis via careful history and management of medical complications with an eating disorder team. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Kyung E. Rhee, MD, MSc, MA

Summary: Eating disorders (ED) are common and have significant morbidity and mortality. EDs are the third most common psychiatric disorder of adolescents with a prevalence of 0.5-2% for anorexia and 0.9-3% for bulimia; 90% of patients are female. Mortality rate can be as high as 10% for anorexia and 1% for bulimia. Diagnosis is formally guided by DSM 5 criteria, but the mnemonic SCOFF can be useful:

- Do you feel or make yourself SICK when eating?

- Do you feel you’ve lost CONTROL of your eating?

- Have you lost one STONE (14 lbs. developed by the British) of weight?

- Do you feel FAT?

- Does FOOD dominate your life?

A detailed history is needed as patients with ED may engage in secretive behaviors to hide their illness. After diagnosis, treatment may be outpatient or inpatient. Medical issues hospitalists are likely to see with inpatients include re-feeding syndrome, various metabolic disturbances, secondary amenorrhea, sleep disturbances, and for patients with bulimia, evidence of dental or esophageal trauma from purging. Differential diagnoses include: IBD, thyroid disease, celiac, diabetes, and Addison’s disease.

Hospitalists’ role in treatment is as part of a multidisciplinary group to manage the medical complications. Inpatient management includes individual and group therapy, monitored group meals, daily blind weights, bathroom visits, and focused lab studies. There is no “cure” and only ~50% of patients are free of ongoing symptoms after treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Eating disorders are common in adolescent females and have significant morbidity and mortality.

- Hospitalists’ role is diagnosis via careful history and management of medical complications with an eating disorder team. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Kyung E. Rhee, MD, MSc, MA

Summary: Eating disorders (ED) are common and have significant morbidity and mortality. EDs are the third most common psychiatric disorder of adolescents with a prevalence of 0.5-2% for anorexia and 0.9-3% for bulimia; 90% of patients are female. Mortality rate can be as high as 10% for anorexia and 1% for bulimia. Diagnosis is formally guided by DSM 5 criteria, but the mnemonic SCOFF can be useful:

- Do you feel or make yourself SICK when eating?

- Do you feel you’ve lost CONTROL of your eating?

- Have you lost one STONE (14 lbs. developed by the British) of weight?

- Do you feel FAT?

- Does FOOD dominate your life?

A detailed history is needed as patients with ED may engage in secretive behaviors to hide their illness. After diagnosis, treatment may be outpatient or inpatient. Medical issues hospitalists are likely to see with inpatients include re-feeding syndrome, various metabolic disturbances, secondary amenorrhea, sleep disturbances, and for patients with bulimia, evidence of dental or esophageal trauma from purging. Differential diagnoses include: IBD, thyroid disease, celiac, diabetes, and Addison’s disease.

Hospitalists’ role in treatment is as part of a multidisciplinary group to manage the medical complications. Inpatient management includes individual and group therapy, monitored group meals, daily blind weights, bathroom visits, and focused lab studies. There is no “cure” and only ~50% of patients are free of ongoing symptoms after treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Eating disorders are common in adolescent females and have significant morbidity and mortality.

- Hospitalists’ role is diagnosis via careful history and management of medical complications with an eating disorder team. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

VIDEO: How to navigate value-based care payer contracts

AUSTIN, TEX. – The shift from volume- to value-based care has become a regular hot topic among the medical community. But one rarely discussed question is how quality-based care will impact physician contracts with health plans, according to Bloomfield Hills, Mich., health law attorney Mark S. Kopson.

In a video interview at an American Health Lawyers Association meeting, Mr. Kopson discusses how to navigate payer contracts when operating within value-based care models. He addresses ideal terms to include in quality-based care contracts and how to mitigate legal risks with health plans.

“The contract language that works in volume-based contracts doesn’t work in value-based contracts,” Mr. Kopson explains. “We have to make a distinction between the two and recognize that there are risks and issues that have to be addressed in value-based arrangements.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @legal_med

AUSTIN, TEX. – The shift from volume- to value-based care has become a regular hot topic among the medical community. But one rarely discussed question is how quality-based care will impact physician contracts with health plans, according to Bloomfield Hills, Mich., health law attorney Mark S. Kopson.

In a video interview at an American Health Lawyers Association meeting, Mr. Kopson discusses how to navigate payer contracts when operating within value-based care models. He addresses ideal terms to include in quality-based care contracts and how to mitigate legal risks with health plans.

“The contract language that works in volume-based contracts doesn’t work in value-based contracts,” Mr. Kopson explains. “We have to make a distinction between the two and recognize that there are risks and issues that have to be addressed in value-based arrangements.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @legal_med

AUSTIN, TEX. – The shift from volume- to value-based care has become a regular hot topic among the medical community. But one rarely discussed question is how quality-based care will impact physician contracts with health plans, according to Bloomfield Hills, Mich., health law attorney Mark S. Kopson.

In a video interview at an American Health Lawyers Association meeting, Mr. Kopson discusses how to navigate payer contracts when operating within value-based care models. He addresses ideal terms to include in quality-based care contracts and how to mitigate legal risks with health plans.

“The contract language that works in volume-based contracts doesn’t work in value-based contracts,” Mr. Kopson explains. “We have to make a distinction between the two and recognize that there are risks and issues that have to be addressed in value-based arrangements.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @legal_med

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PHYSICIANS AND HOSPITALS LAW INSTITUTE

Frontline Teams Needed for Rapidly Changing Healthcare

Healthcare is changing rapidly, shifting focus from volume to value, says Jeffrey Glasheen, MD, SFHM, lead author of the abstract “Developing Frontline Teams to Drive Health System Transformation.” To support this transformation, frontline clinical leaders need to be able to build and manage teams and care processes—skills not taught in traditional health professional training.

That’s why the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus launched the Certificate Training Program (CTP). The CTP curriculum focuses on enhancing team performance, leadership development, and process improvement. Participants meet weekly and receive support from a coach, a process-improvement specialist, and a data analyst.

Following the yearlong program, participants showed significant improvements in self-perception of leadership (37% to 75% able to manage change), quality improvement (23% to 78% able to use QI tools), and efficiency (31% to 69% able to reduce operational waste) skills. The participants’ work resulted in measurable improvements for the hospital: multiday reductions in length of stays, more than $200,000 in antibiotic cost avoidance for hospitalized pediatric patients, and improvement in pain and symptom scores for palliative care patients. Overall cost avoidance and revenue benefit exceeded $5 million.\

“We aimed to demonstrate that the work that we all need to accomplish—improving the value equation—can best be accomplished through the creation, development, and resourcing of high-functioning teams,” says Dr. Glasheen, an SHM board member. “Most important, we showed that a comprehensive training and development program aimed at creating, resourcing, and supporting high-functioning clinical leadership teams can facilitate academic medical centers’ efforts to pursue high-value care and achieve measurable improvement.”

Reference

1. Glasheen J, Cumbler E, Kneeland P, et al. Developing frontline teams to drive health system transformation [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2015;10(suppl 2). Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/developing-frontline-teams-to-drive-health-system-transformation/. Accessed January 28, 2016.

Healthcare is changing rapidly, shifting focus from volume to value, says Jeffrey Glasheen, MD, SFHM, lead author of the abstract “Developing Frontline Teams to Drive Health System Transformation.” To support this transformation, frontline clinical leaders need to be able to build and manage teams and care processes—skills not taught in traditional health professional training.

That’s why the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus launched the Certificate Training Program (CTP). The CTP curriculum focuses on enhancing team performance, leadership development, and process improvement. Participants meet weekly and receive support from a coach, a process-improvement specialist, and a data analyst.

Following the yearlong program, participants showed significant improvements in self-perception of leadership (37% to 75% able to manage change), quality improvement (23% to 78% able to use QI tools), and efficiency (31% to 69% able to reduce operational waste) skills. The participants’ work resulted in measurable improvements for the hospital: multiday reductions in length of stays, more than $200,000 in antibiotic cost avoidance for hospitalized pediatric patients, and improvement in pain and symptom scores for palliative care patients. Overall cost avoidance and revenue benefit exceeded $5 million.\

“We aimed to demonstrate that the work that we all need to accomplish—improving the value equation—can best be accomplished through the creation, development, and resourcing of high-functioning teams,” says Dr. Glasheen, an SHM board member. “Most important, we showed that a comprehensive training and development program aimed at creating, resourcing, and supporting high-functioning clinical leadership teams can facilitate academic medical centers’ efforts to pursue high-value care and achieve measurable improvement.”

Reference

1. Glasheen J, Cumbler E, Kneeland P, et al. Developing frontline teams to drive health system transformation [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2015;10(suppl 2). Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/developing-frontline-teams-to-drive-health-system-transformation/. Accessed January 28, 2016.

Healthcare is changing rapidly, shifting focus from volume to value, says Jeffrey Glasheen, MD, SFHM, lead author of the abstract “Developing Frontline Teams to Drive Health System Transformation.” To support this transformation, frontline clinical leaders need to be able to build and manage teams and care processes—skills not taught in traditional health professional training.

That’s why the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus launched the Certificate Training Program (CTP). The CTP curriculum focuses on enhancing team performance, leadership development, and process improvement. Participants meet weekly and receive support from a coach, a process-improvement specialist, and a data analyst.

Following the yearlong program, participants showed significant improvements in self-perception of leadership (37% to 75% able to manage change), quality improvement (23% to 78% able to use QI tools), and efficiency (31% to 69% able to reduce operational waste) skills. The participants’ work resulted in measurable improvements for the hospital: multiday reductions in length of stays, more than $200,000 in antibiotic cost avoidance for hospitalized pediatric patients, and improvement in pain and symptom scores for palliative care patients. Overall cost avoidance and revenue benefit exceeded $5 million.\

“We aimed to demonstrate that the work that we all need to accomplish—improving the value equation—can best be accomplished through the creation, development, and resourcing of high-functioning teams,” says Dr. Glasheen, an SHM board member. “Most important, we showed that a comprehensive training and development program aimed at creating, resourcing, and supporting high-functioning clinical leadership teams can facilitate academic medical centers’ efforts to pursue high-value care and achieve measurable improvement.”

Reference

1. Glasheen J, Cumbler E, Kneeland P, et al. Developing frontline teams to drive health system transformation [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2015;10(suppl 2). Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/developing-frontline-teams-to-drive-health-system-transformation/. Accessed January 28, 2016.

HM16 Session Analysis: Stay Calm, Safe During Inpatient Behavioral Emergencies

Presenters: David Pressel, MD, PhD, FAAP, FHM, Emily Fingado, MD, FAAP, and Jessica Tomaszewski, MD, FAAP

Summary: Patients may engage in violent behaviors that pose a danger to themselves or others. Behavioral emergencies may be rare, can be dangerous, and staff may feel ill-trained to respond appropriately. Patients with ingestions, or underlying psychiatric or developmental difficulties, are at highest risk for developing a behavioral emergency.

The first strategy in handling a potentially violent patient is de-escalation, i.e., trying to identify and rectify the behavioral trigger. If de-escalation is not successful, personal safety is paramount. Get away from the patient and get help. If a patient needs to be physically restrained, minimally there should be one staff member per limb. Various physical devices, including soft restraints, four-point leathers, hand mittens, and spit hoods may be used to control a violent patient. A violent restraint is characterized by the indication, not the device. Medications may be used to treat the underlying mental health issue and should not be used as PRN chemical restraints.

After a violent patient is safely restrained, further steps need to be taken, including notification of the attending or legal guardian if a minor; documentation of the event, including a debrief of what occurred; a room sweep to ensure securing any dangerous items (metal eating utensils); and modification of the care plan to strategize on removal of the restraints as soon as is safe.

Hospitals should view behavioral emergencies similarly to a Code Blue. Have a specialized team that responds and undergoes regular training.

Key Takeaways

- Behavioral emergencies occur when a patient becomes violent.

- De-escalation is the best response.

- If not successful, maintain personal safety, control and medicate the patient as appropriate, and document clearly. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenters: David Pressel, MD, PhD, FAAP, FHM, Emily Fingado, MD, FAAP, and Jessica Tomaszewski, MD, FAAP

Summary: Patients may engage in violent behaviors that pose a danger to themselves or others. Behavioral emergencies may be rare, can be dangerous, and staff may feel ill-trained to respond appropriately. Patients with ingestions, or underlying psychiatric or developmental difficulties, are at highest risk for developing a behavioral emergency.

The first strategy in handling a potentially violent patient is de-escalation, i.e., trying to identify and rectify the behavioral trigger. If de-escalation is not successful, personal safety is paramount. Get away from the patient and get help. If a patient needs to be physically restrained, minimally there should be one staff member per limb. Various physical devices, including soft restraints, four-point leathers, hand mittens, and spit hoods may be used to control a violent patient. A violent restraint is characterized by the indication, not the device. Medications may be used to treat the underlying mental health issue and should not be used as PRN chemical restraints.

After a violent patient is safely restrained, further steps need to be taken, including notification of the attending or legal guardian if a minor; documentation of the event, including a debrief of what occurred; a room sweep to ensure securing any dangerous items (metal eating utensils); and modification of the care plan to strategize on removal of the restraints as soon as is safe.

Hospitals should view behavioral emergencies similarly to a Code Blue. Have a specialized team that responds and undergoes regular training.

Key Takeaways

- Behavioral emergencies occur when a patient becomes violent.

- De-escalation is the best response.

- If not successful, maintain personal safety, control and medicate the patient as appropriate, and document clearly. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenters: David Pressel, MD, PhD, FAAP, FHM, Emily Fingado, MD, FAAP, and Jessica Tomaszewski, MD, FAAP

Summary: Patients may engage in violent behaviors that pose a danger to themselves or others. Behavioral emergencies may be rare, can be dangerous, and staff may feel ill-trained to respond appropriately. Patients with ingestions, or underlying psychiatric or developmental difficulties, are at highest risk for developing a behavioral emergency.

The first strategy in handling a potentially violent patient is de-escalation, i.e., trying to identify and rectify the behavioral trigger. If de-escalation is not successful, personal safety is paramount. Get away from the patient and get help. If a patient needs to be physically restrained, minimally there should be one staff member per limb. Various physical devices, including soft restraints, four-point leathers, hand mittens, and spit hoods may be used to control a violent patient. A violent restraint is characterized by the indication, not the device. Medications may be used to treat the underlying mental health issue and should not be used as PRN chemical restraints.

After a violent patient is safely restrained, further steps need to be taken, including notification of the attending or legal guardian if a minor; documentation of the event, including a debrief of what occurred; a room sweep to ensure securing any dangerous items (metal eating utensils); and modification of the care plan to strategize on removal of the restraints as soon as is safe.

Hospitals should view behavioral emergencies similarly to a Code Blue. Have a specialized team that responds and undergoes regular training.

Key Takeaways

- Behavioral emergencies occur when a patient becomes violent.

- De-escalation is the best response.

- If not successful, maintain personal safety, control and medicate the patient as appropriate, and document clearly. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Revisiting the ‘Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group'

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

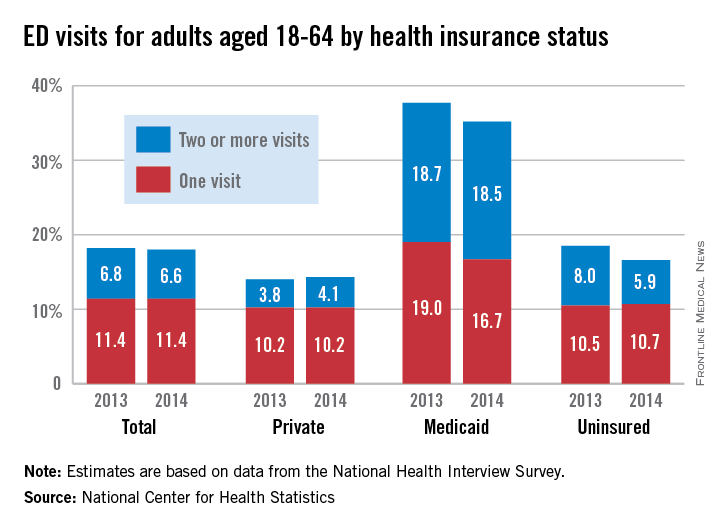

Medicaid recipients much more likely to visit the ED

Adults aged 18-64 with Medicaid coverage were almost twice as likely as all adults to visit the emergency department in 2014, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

In 2014, an estimated 35.2% of Medicaid recipients aged 18-64 years visited the emergency department at least once, with more than half of those (18.5%) being people who made two or more visits for the year. Among all adults aged 18-64, 18.0% made at least one ED visit, while 6.6% of all adults made two or more. In 2014, 14.3% of adults 18-64 with private insurance made one or more ED visits, as did 16.6% of those who were uninsured, the NCHS reported.

Compared with 2013, adults with ED visits were down slightly for all adults (18.2% to 18.0%), up slightly for those with private insurance (14.0% to 14.3%), and down for those with Medicaid (37.7% to 35.2%) and the uninsured (18.5% to 16.6%), the report showed.

There was a significant decrease for uninsured adults with two or more visits from 8.0% in 2013 to 5.9% in 2014 (P less than .05), and the drop among Medicaid recipients with one ED visit from 19% in 2013 to 16.7% in 2014 was significant at P less than .1, the NCHS noted.

The highest rates of ED use among adults have consistently been associated “with public health coverage such as Medicaid, relative to adults who were uninsured or had private health insurance. This higher rate of use may be related to more serious medical needs in the Medicaid population,” the NCHS investigators said.

Younger individuals (ages 18-29) were more likely to visit the ED, with 20.2% having at least one visit in 2014, compared with 16.8% of those aged 30-44 years and 17.5% of those aged 45-64. There also were differences by race and ethnicity, as 26.5% of non-Hispanic blacks made one or more ED visits in 2014, compared with 17.5% of non-Hispanic whites and 15.7% of Hispanics, according to the report, which was based on data from the National Health Interview Survey (n = 26,825 for 2013 and 28,053 for 2014).

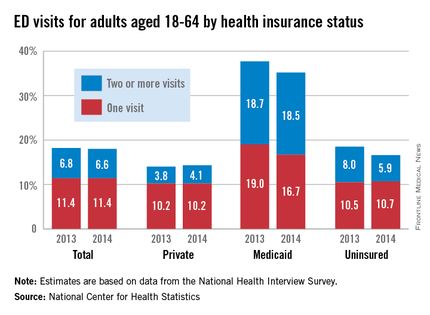

Adults aged 18-64 with Medicaid coverage were almost twice as likely as all adults to visit the emergency department in 2014, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

In 2014, an estimated 35.2% of Medicaid recipients aged 18-64 years visited the emergency department at least once, with more than half of those (18.5%) being people who made two or more visits for the year. Among all adults aged 18-64, 18.0% made at least one ED visit, while 6.6% of all adults made two or more. In 2014, 14.3% of adults 18-64 with private insurance made one or more ED visits, as did 16.6% of those who were uninsured, the NCHS reported.

Compared with 2013, adults with ED visits were down slightly for all adults (18.2% to 18.0%), up slightly for those with private insurance (14.0% to 14.3%), and down for those with Medicaid (37.7% to 35.2%) and the uninsured (18.5% to 16.6%), the report showed.

There was a significant decrease for uninsured adults with two or more visits from 8.0% in 2013 to 5.9% in 2014 (P less than .05), and the drop among Medicaid recipients with one ED visit from 19% in 2013 to 16.7% in 2014 was significant at P less than .1, the NCHS noted.

The highest rates of ED use among adults have consistently been associated “with public health coverage such as Medicaid, relative to adults who were uninsured or had private health insurance. This higher rate of use may be related to more serious medical needs in the Medicaid population,” the NCHS investigators said.

Younger individuals (ages 18-29) were more likely to visit the ED, with 20.2% having at least one visit in 2014, compared with 16.8% of those aged 30-44 years and 17.5% of those aged 45-64. There also were differences by race and ethnicity, as 26.5% of non-Hispanic blacks made one or more ED visits in 2014, compared with 17.5% of non-Hispanic whites and 15.7% of Hispanics, according to the report, which was based on data from the National Health Interview Survey (n = 26,825 for 2013 and 28,053 for 2014).

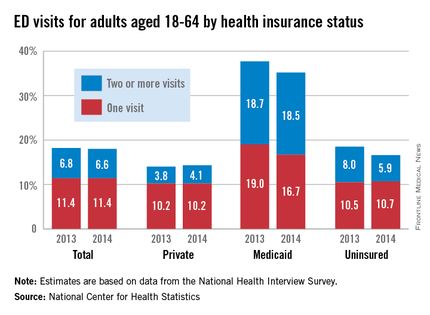

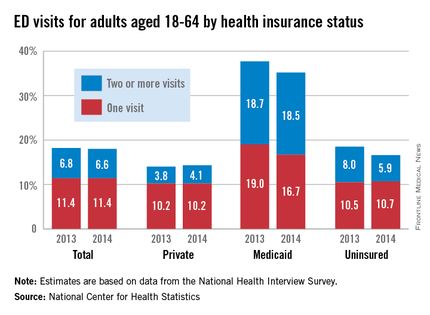

Adults aged 18-64 with Medicaid coverage were almost twice as likely as all adults to visit the emergency department in 2014, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

In 2014, an estimated 35.2% of Medicaid recipients aged 18-64 years visited the emergency department at least once, with more than half of those (18.5%) being people who made two or more visits for the year. Among all adults aged 18-64, 18.0% made at least one ED visit, while 6.6% of all adults made two or more. In 2014, 14.3% of adults 18-64 with private insurance made one or more ED visits, as did 16.6% of those who were uninsured, the NCHS reported.

Compared with 2013, adults with ED visits were down slightly for all adults (18.2% to 18.0%), up slightly for those with private insurance (14.0% to 14.3%), and down for those with Medicaid (37.7% to 35.2%) and the uninsured (18.5% to 16.6%), the report showed.

There was a significant decrease for uninsured adults with two or more visits from 8.0% in 2013 to 5.9% in 2014 (P less than .05), and the drop among Medicaid recipients with one ED visit from 19% in 2013 to 16.7% in 2014 was significant at P less than .1, the NCHS noted.

The highest rates of ED use among adults have consistently been associated “with public health coverage such as Medicaid, relative to adults who were uninsured or had private health insurance. This higher rate of use may be related to more serious medical needs in the Medicaid population,” the NCHS investigators said.

Younger individuals (ages 18-29) were more likely to visit the ED, with 20.2% having at least one visit in 2014, compared with 16.8% of those aged 30-44 years and 17.5% of those aged 45-64. There also were differences by race and ethnicity, as 26.5% of non-Hispanic blacks made one or more ED visits in 2014, compared with 17.5% of non-Hispanic whites and 15.7% of Hispanics, according to the report, which was based on data from the National Health Interview Survey (n = 26,825 for 2013 and 28,053 for 2014).

HM16 Session Analysis: Maximizing Collaboration With PAs & NPs: Rules, Realities, Reimbursement

Presenter: Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, MJ Health Law

Summary: Ms. Marriott brought humor to a detailed #HospMed16 presentation on the rules of reimbursement and Medicare requirements for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). The session was packed with information regarding the Medicare regulations relating to PAs and NPs, as well as information from state Medicaid programs and commercial payors. The presentation continued with focusing on myth busters and misperceptions about PAs and NPs. These topics were reviewed in depth:

- PAs and NPs have been recognized as providers by Medicare since 1998, as demonstrated by Medicare citations provided to the audience.

- Supervision/collaboration, as defined by Medicare requirements.

- Medicare payment policy: “incident to” vs. “split/shared visit,” reviewing unacceptable shared visit documentation and unintended consequences of fewer shared visits.

The discussion provided detailed insight into how to address the question, “What about the 15% reduced Medicare reimbursement for PAs and NPs?” An analytical approach to answering this question was provided as it relates to inpatient services, observation services, critical care services, and consultations. At the end of the talk, the audience was very engaged, and a lively Q&A ensued past the scheduled time. TH

Presenter: Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, MJ Health Law

Summary: Ms. Marriott brought humor to a detailed #HospMed16 presentation on the rules of reimbursement and Medicare requirements for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). The session was packed with information regarding the Medicare regulations relating to PAs and NPs, as well as information from state Medicaid programs and commercial payors. The presentation continued with focusing on myth busters and misperceptions about PAs and NPs. These topics were reviewed in depth:

- PAs and NPs have been recognized as providers by Medicare since 1998, as demonstrated by Medicare citations provided to the audience.

- Supervision/collaboration, as defined by Medicare requirements.

- Medicare payment policy: “incident to” vs. “split/shared visit,” reviewing unacceptable shared visit documentation and unintended consequences of fewer shared visits.

The discussion provided detailed insight into how to address the question, “What about the 15% reduced Medicare reimbursement for PAs and NPs?” An analytical approach to answering this question was provided as it relates to inpatient services, observation services, critical care services, and consultations. At the end of the talk, the audience was very engaged, and a lively Q&A ensued past the scheduled time. TH

Presenter: Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, MJ Health Law

Summary: Ms. Marriott brought humor to a detailed #HospMed16 presentation on the rules of reimbursement and Medicare requirements for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). The session was packed with information regarding the Medicare regulations relating to PAs and NPs, as well as information from state Medicaid programs and commercial payors. The presentation continued with focusing on myth busters and misperceptions about PAs and NPs. These topics were reviewed in depth:

- PAs and NPs have been recognized as providers by Medicare since 1998, as demonstrated by Medicare citations provided to the audience.

- Supervision/collaboration, as defined by Medicare requirements.

- Medicare payment policy: “incident to” vs. “split/shared visit,” reviewing unacceptable shared visit documentation and unintended consequences of fewer shared visits.

The discussion provided detailed insight into how to address the question, “What about the 15% reduced Medicare reimbursement for PAs and NPs?” An analytical approach to answering this question was provided as it relates to inpatient services, observation services, critical care services, and consultations. At the end of the talk, the audience was very engaged, and a lively Q&A ensued past the scheduled time. TH

HM16 Session Analysis: Health Information Technology Controversies

Presenter: Julie Hollberg, MD

Summary: Dr. Julie Hollberg, the chief medical information officer for Emory Healthcare, presented an overview of three pressing health information technology (IT) concerns at Hospital Medicine 2016, the “Year of the Hospitalist.” These issues are the use of copy-and-paste functions in electronic charting, alert fatigue, and patient access to electronic charts.

Dr. Hollberg states the key to leveraging healthcare IT to improve the patient and clinician experience is to coordinate people, technology, and the process. She relates that electronic note quality is poor due to lost narratives, “note bloat” (unnecessary text and data), and the use of copy-and-paste.

However, hospitalists themselves are essential in improving documentation. “We have 100% control of what goes into the note,” she describes. Some 90% of residents and attendings use copy-and-paste often. Most of the physicians agree the use of copy-and-paste increases inconsistencies, but 80% of physicians desire to continue the practice. The need for copy-and-paste should decrease as EMRs advance and expectations of note content is more broadly communicated.

Alerts are designed to improve patient safety and are a Meaningful Use initiative. The goal of clinical decision support is to provide the right information to the right person at the right time. However alert fatigue is a concern. Recommendations to address alert fatigue include making alerts non-interruptive, tier basing the alerts by severity, and decreasing the frequency of drug interaction alerts.

Dr. Hollberg also described the benefits of patient access to healthcare information on web portals. These benefits lead to improved patient engagement. Most physician concerns about open access has not been seen in actual practice. For example, only 1-8% of patients say that access to notes causes confusion, worry, or offense.

Key Takeaways:

- Use of copy-and-paste creates “note bloat” and inconsistencies. The practice is discouraged.

- Patients prefer access to healthcare information on portals. The benefit to improved access is greater patient engagement.

- While alert fatigue is a concern, clinicians should still read alerts! TH

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston and a former member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Julie Hollberg, MD

Summary: Dr. Julie Hollberg, the chief medical information officer for Emory Healthcare, presented an overview of three pressing health information technology (IT) concerns at Hospital Medicine 2016, the “Year of the Hospitalist.” These issues are the use of copy-and-paste functions in electronic charting, alert fatigue, and patient access to electronic charts.

Dr. Hollberg states the key to leveraging healthcare IT to improve the patient and clinician experience is to coordinate people, technology, and the process. She relates that electronic note quality is poor due to lost narratives, “note bloat” (unnecessary text and data), and the use of copy-and-paste.

However, hospitalists themselves are essential in improving documentation. “We have 100% control of what goes into the note,” she describes. Some 90% of residents and attendings use copy-and-paste often. Most of the physicians agree the use of copy-and-paste increases inconsistencies, but 80% of physicians desire to continue the practice. The need for copy-and-paste should decrease as EMRs advance and expectations of note content is more broadly communicated.

Alerts are designed to improve patient safety and are a Meaningful Use initiative. The goal of clinical decision support is to provide the right information to the right person at the right time. However alert fatigue is a concern. Recommendations to address alert fatigue include making alerts non-interruptive, tier basing the alerts by severity, and decreasing the frequency of drug interaction alerts.

Dr. Hollberg also described the benefits of patient access to healthcare information on web portals. These benefits lead to improved patient engagement. Most physician concerns about open access has not been seen in actual practice. For example, only 1-8% of patients say that access to notes causes confusion, worry, or offense.

Key Takeaways:

- Use of copy-and-paste creates “note bloat” and inconsistencies. The practice is discouraged.

- Patients prefer access to healthcare information on portals. The benefit to improved access is greater patient engagement.

- While alert fatigue is a concern, clinicians should still read alerts! TH

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston and a former member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Julie Hollberg, MD

Summary: Dr. Julie Hollberg, the chief medical information officer for Emory Healthcare, presented an overview of three pressing health information technology (IT) concerns at Hospital Medicine 2016, the “Year of the Hospitalist.” These issues are the use of copy-and-paste functions in electronic charting, alert fatigue, and patient access to electronic charts.

Dr. Hollberg states the key to leveraging healthcare IT to improve the patient and clinician experience is to coordinate people, technology, and the process. She relates that electronic note quality is poor due to lost narratives, “note bloat” (unnecessary text and data), and the use of copy-and-paste.

However, hospitalists themselves are essential in improving documentation. “We have 100% control of what goes into the note,” she describes. Some 90% of residents and attendings use copy-and-paste often. Most of the physicians agree the use of copy-and-paste increases inconsistencies, but 80% of physicians desire to continue the practice. The need for copy-and-paste should decrease as EMRs advance and expectations of note content is more broadly communicated.

Alerts are designed to improve patient safety and are a Meaningful Use initiative. The goal of clinical decision support is to provide the right information to the right person at the right time. However alert fatigue is a concern. Recommendations to address alert fatigue include making alerts non-interruptive, tier basing the alerts by severity, and decreasing the frequency of drug interaction alerts.

Dr. Hollberg also described the benefits of patient access to healthcare information on web portals. These benefits lead to improved patient engagement. Most physician concerns about open access has not been seen in actual practice. For example, only 1-8% of patients say that access to notes causes confusion, worry, or offense.

Key Takeaways:

- Use of copy-and-paste creates “note bloat” and inconsistencies. The practice is discouraged.

- Patients prefer access to healthcare information on portals. The benefit to improved access is greater patient engagement.

- While alert fatigue is a concern, clinicians should still read alerts! TH

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston and a former member of Team Hospitalist.

HM16 Session Analysis: Reinforcing Practice Culture, Maximizing Engagement Through Effective Communication

HM16 Presenters: Dr. Scott Rissmiller, Dr. Steve Deitelzweig, Dr. Jerome Siy, Dr. Thomas Mcllraith, and Dr. Michael Reitz

Summary: This session at #HospMed16 explored lessons learned from five hospitalist leaders across the country about improving hospitalist practice through enhancing hospitalist engagement, group communication, and leadership development. It was proposed that the “new” value equation is [Engagement * (quality/cost)] = Value. Engagement is the multiplier of value. The speakers highlighted the following:

Build a Plan : Approach engagement like any other business plan with metrics, accountability, and “S.M.A.R.T." goals.

Build Trust: Visibility breeds credibility. Credibility breeds Trust. Trust encourages Engagement.

Build Transparency: Keep communication simple and be sure that it’s helpful information.

Build Leaders: All hospitalists are leaders. Strong leadership skills promote effective communication across the system. Nurture leadership skills for the right level of leadership, to find the right seat on the bus.

Build Celebrations: Celebrate successes, and learn from failure. TH

HM16 Presenters: Dr. Scott Rissmiller, Dr. Steve Deitelzweig, Dr. Jerome Siy, Dr. Thomas Mcllraith, and Dr. Michael Reitz

Summary: This session at #HospMed16 explored lessons learned from five hospitalist leaders across the country about improving hospitalist practice through enhancing hospitalist engagement, group communication, and leadership development. It was proposed that the “new” value equation is [Engagement * (quality/cost)] = Value. Engagement is the multiplier of value. The speakers highlighted the following:

Build a Plan : Approach engagement like any other business plan with metrics, accountability, and “S.M.A.R.T." goals.

Build Trust: Visibility breeds credibility. Credibility breeds Trust. Trust encourages Engagement.

Build Transparency: Keep communication simple and be sure that it’s helpful information.

Build Leaders: All hospitalists are leaders. Strong leadership skills promote effective communication across the system. Nurture leadership skills for the right level of leadership, to find the right seat on the bus.

Build Celebrations: Celebrate successes, and learn from failure. TH

HM16 Presenters: Dr. Scott Rissmiller, Dr. Steve Deitelzweig, Dr. Jerome Siy, Dr. Thomas Mcllraith, and Dr. Michael Reitz

Summary: This session at #HospMed16 explored lessons learned from five hospitalist leaders across the country about improving hospitalist practice through enhancing hospitalist engagement, group communication, and leadership development. It was proposed that the “new” value equation is [Engagement * (quality/cost)] = Value. Engagement is the multiplier of value. The speakers highlighted the following:

Build a Plan : Approach engagement like any other business plan with metrics, accountability, and “S.M.A.R.T." goals.

Build Trust: Visibility breeds credibility. Credibility breeds Trust. Trust encourages Engagement.

Build Transparency: Keep communication simple and be sure that it’s helpful information.

Build Leaders: All hospitalists are leaders. Strong leadership skills promote effective communication across the system. Nurture leadership skills for the right level of leadership, to find the right seat on the bus.

Build Celebrations: Celebrate successes, and learn from failure. TH

HM16 Session Analysis: Infectious Disease Emergencies: Three Diagnoses You Can’t Afford to Miss

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH