User login

Care Teams Work Best When Members Have a Voice

I stumbled upon an absolutely brilliant TED talk about how we need to forget about the “pecking order” within workplaces and how we need to focus on team social connectedness as a strategy to enhance teamwork and productivity.1 I found the analogy in the presenter’s talk so incredibly poignant for the work we do every day in hospital medicine. As we work to solve incredibly challenging problems daily, we do so among continuously changing and highly charged teams. How can we create our teams to be the most effective and productive to serve the greater good?

The speaker, Margaret Heffernan, is an entrepreneur and former CEO of five companies. She tells a story about a study performed by an evolutionary biologist by the name of William Muir of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind.2 Muir undertook a series of studies evaluating the social order and productivity of chickens (as measured by egg production) and the team characteristics that make chickens more or less productive. After watching flocks of chickens for several generations, he picked out the most productive chickens and put them all together in a “super flock.” He then watched their productivity over the next several generations and compared their productivity to those in the regular flock.

What he found was that the regular flock became more productive and most of the members of the super flock were dead!

The most productive members of the super flock had essentially pecked the other members to death. He surmised that the only reason the super chickens were initially productive was by suppressing the productivity of the original flock members. The chickens in the regular flock that were initially less aggressive (and less productive) over time sustained fewer injuries and were able to be more productive in the absence of super chickens. The energy that the animals had previously invested in negative behaviors (pecking, injuries, and healing) was redirected into positive behaviors (making eggs).

Muir and his team have gone on to research a tool to predict social aggressiveness and social agreeableness in individual animals. Those high on the socially agreeable scales (and low on the socially aggressive scales) are more valuable for producing highly effective teams of agricultural animals by enhancing group dynamics, social interactions, and actual productivity.

Backward Thinking

Heffernan argues that we have run most businesses (hospitals included) and many societies (at least capitalistic ones) in the super chicken model. In this model, we view leadership as a trait to be individually owned and perfected, and we think that leaders are supposed to have all the answers. In order to determine our leaders, we charge highly competent people to compete against one another as if in a talent contest. It has long been thought that to be successful as teams, we should recruit the best and brightest, pit them against on another, and see who wins, then promote the winner, put them in charge of everything, and give them all the resources they could want or need to be a super chicken.

But this model inevitably suppresses the remainder of the flock and leads to aggression and waste.

In many scenarios in our hospitals, physicians view themselves as and act like super chickens; we try to be the hardest working, the brightest, and the most powerful. How many times have we heard of or witnessed circumstances where a physician suppresses the candor or opinion from other disciplines on the care team? I think we all know physicians (ourselves included) who demand the role of decision maker and ignore the opinions or needs of the remainder of the team, including patients or their family.

Alternatives

So if we should not be subscribing to the super chicken theory, then what type of leadership structures should we be subscribing to within medical teams to produce the best outcomes for ourselves and for our patients and their families?

A study performed by MIT scientists gives us some insight. Researchers found that when random groups of people are given very difficult problems to solve (e.g., think about diagnostic dilemmas or very difficult patients), certain group attributes made it more likely that the group would be successful in solving these difficult problems. The groups that were most effective were not those with a few people with extremely high IQs or with the highest collective IQ. The teams that were most effective and able to solve difficult problems were those that showed high degrees of social sensitivity among members (i.e., empathy). The highest-performing teams gave roughly equal time to each member (e.g., think about physicians, pharmacists, social workers, case managers, consultants on a typical medical team). They also found the highest-performing teams had more women in them. (I feel so redeemed!)

In summary, what they learned from these experiments was that the most successful teams were more socially connected and more highly attuned and sensitive to one another. This is not to say that highly successful teams were leaderless. There is absolutely a vital role that leaders play in such teams. In Jim Collins’ famous book Good to Great, in studying leadership and teams, he did not find the best leaders were super chickens who autocratically made unilateral decisions. Instead, he found the best leaders function more like facilitators, having the humility and skill to draw out shared solutions from large participatory teams.3 Doesn’t this sound like how a hospitalist should run multidisciplinary rounds?

The other major attribute that the MIT researchers noticed about highly functional teams is that each and every member of the team was extremely willing and able to give and receive help. They found that teams with high mutual understanding and trust were more likely to seamlessly—and almost effortlessly—give and receive help from one another. They ended up acting as one another’s social support network. If any team member was confronted by a difficult problem or situation, each felt confident that it could be easily solved with the collective skill and wisdom of the team.

As a result of such research, some companies have developed and implemented strategies to enhance such social capital, such as synchronizing coffee breaks and disallowing coffee mugs at individual desks. These companies consider it a vital strategic mission to ensure that team members get to know and understand one another and that they serve as a social support network at work. They believe that it is reliance and interdependency that ensures trust and enhances productivity.

So what really matters is the mortar, not just the bricks.

HM Takeaway

For hospital medicine teams, what we need to do is accept that teams work best when every member has a voice and is valued. When others look to us (usually seen as team leaders) to make all the decisions (as if we are super chickens), we need to empower our team members to make decisions with us.

We need to actively work toward this model of being a team leader, break any cycles of dependency that we have set up, and produce better outcomes.

We need to avoid acting like super chickens and appreciate and empower a true team effort.

We need to stop accepting that management and promotions occur by talent contests that pit employees against one another and insist that rivalry at every level has to be replaced by social capital and social connectedness.

Only then will our leadership result in creating effective and productive bricks and mortar. TH

References

- Heffernan M. Margaret Heffernan: why it’s time to forget the pecking order at work. TED Talks. June 16, 2015. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vyn_xLrtZaY&feature=youtu.be.

- Steeves SA. Scientists find method to pick non-competitive animals, improve production. Available at: https://news.uns.purdue.edu/x/2007a/070212MuirSelection.html.

- Collins J. Good to Great. New York, N.Y.: HarperBusiness; 2011.

I stumbled upon an absolutely brilliant TED talk about how we need to forget about the “pecking order” within workplaces and how we need to focus on team social connectedness as a strategy to enhance teamwork and productivity.1 I found the analogy in the presenter’s talk so incredibly poignant for the work we do every day in hospital medicine. As we work to solve incredibly challenging problems daily, we do so among continuously changing and highly charged teams. How can we create our teams to be the most effective and productive to serve the greater good?

The speaker, Margaret Heffernan, is an entrepreneur and former CEO of five companies. She tells a story about a study performed by an evolutionary biologist by the name of William Muir of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind.2 Muir undertook a series of studies evaluating the social order and productivity of chickens (as measured by egg production) and the team characteristics that make chickens more or less productive. After watching flocks of chickens for several generations, he picked out the most productive chickens and put them all together in a “super flock.” He then watched their productivity over the next several generations and compared their productivity to those in the regular flock.

What he found was that the regular flock became more productive and most of the members of the super flock were dead!

The most productive members of the super flock had essentially pecked the other members to death. He surmised that the only reason the super chickens were initially productive was by suppressing the productivity of the original flock members. The chickens in the regular flock that were initially less aggressive (and less productive) over time sustained fewer injuries and were able to be more productive in the absence of super chickens. The energy that the animals had previously invested in negative behaviors (pecking, injuries, and healing) was redirected into positive behaviors (making eggs).

Muir and his team have gone on to research a tool to predict social aggressiveness and social agreeableness in individual animals. Those high on the socially agreeable scales (and low on the socially aggressive scales) are more valuable for producing highly effective teams of agricultural animals by enhancing group dynamics, social interactions, and actual productivity.

Backward Thinking

Heffernan argues that we have run most businesses (hospitals included) and many societies (at least capitalistic ones) in the super chicken model. In this model, we view leadership as a trait to be individually owned and perfected, and we think that leaders are supposed to have all the answers. In order to determine our leaders, we charge highly competent people to compete against one another as if in a talent contest. It has long been thought that to be successful as teams, we should recruit the best and brightest, pit them against on another, and see who wins, then promote the winner, put them in charge of everything, and give them all the resources they could want or need to be a super chicken.

But this model inevitably suppresses the remainder of the flock and leads to aggression and waste.

In many scenarios in our hospitals, physicians view themselves as and act like super chickens; we try to be the hardest working, the brightest, and the most powerful. How many times have we heard of or witnessed circumstances where a physician suppresses the candor or opinion from other disciplines on the care team? I think we all know physicians (ourselves included) who demand the role of decision maker and ignore the opinions or needs of the remainder of the team, including patients or their family.

Alternatives

So if we should not be subscribing to the super chicken theory, then what type of leadership structures should we be subscribing to within medical teams to produce the best outcomes for ourselves and for our patients and their families?

A study performed by MIT scientists gives us some insight. Researchers found that when random groups of people are given very difficult problems to solve (e.g., think about diagnostic dilemmas or very difficult patients), certain group attributes made it more likely that the group would be successful in solving these difficult problems. The groups that were most effective were not those with a few people with extremely high IQs or with the highest collective IQ. The teams that were most effective and able to solve difficult problems were those that showed high degrees of social sensitivity among members (i.e., empathy). The highest-performing teams gave roughly equal time to each member (e.g., think about physicians, pharmacists, social workers, case managers, consultants on a typical medical team). They also found the highest-performing teams had more women in them. (I feel so redeemed!)

In summary, what they learned from these experiments was that the most successful teams were more socially connected and more highly attuned and sensitive to one another. This is not to say that highly successful teams were leaderless. There is absolutely a vital role that leaders play in such teams. In Jim Collins’ famous book Good to Great, in studying leadership and teams, he did not find the best leaders were super chickens who autocratically made unilateral decisions. Instead, he found the best leaders function more like facilitators, having the humility and skill to draw out shared solutions from large participatory teams.3 Doesn’t this sound like how a hospitalist should run multidisciplinary rounds?

The other major attribute that the MIT researchers noticed about highly functional teams is that each and every member of the team was extremely willing and able to give and receive help. They found that teams with high mutual understanding and trust were more likely to seamlessly—and almost effortlessly—give and receive help from one another. They ended up acting as one another’s social support network. If any team member was confronted by a difficult problem or situation, each felt confident that it could be easily solved with the collective skill and wisdom of the team.

As a result of such research, some companies have developed and implemented strategies to enhance such social capital, such as synchronizing coffee breaks and disallowing coffee mugs at individual desks. These companies consider it a vital strategic mission to ensure that team members get to know and understand one another and that they serve as a social support network at work. They believe that it is reliance and interdependency that ensures trust and enhances productivity.

So what really matters is the mortar, not just the bricks.

HM Takeaway

For hospital medicine teams, what we need to do is accept that teams work best when every member has a voice and is valued. When others look to us (usually seen as team leaders) to make all the decisions (as if we are super chickens), we need to empower our team members to make decisions with us.

We need to actively work toward this model of being a team leader, break any cycles of dependency that we have set up, and produce better outcomes.

We need to avoid acting like super chickens and appreciate and empower a true team effort.

We need to stop accepting that management and promotions occur by talent contests that pit employees against one another and insist that rivalry at every level has to be replaced by social capital and social connectedness.

Only then will our leadership result in creating effective and productive bricks and mortar. TH

References

- Heffernan M. Margaret Heffernan: why it’s time to forget the pecking order at work. TED Talks. June 16, 2015. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vyn_xLrtZaY&feature=youtu.be.

- Steeves SA. Scientists find method to pick non-competitive animals, improve production. Available at: https://news.uns.purdue.edu/x/2007a/070212MuirSelection.html.

- Collins J. Good to Great. New York, N.Y.: HarperBusiness; 2011.

I stumbled upon an absolutely brilliant TED talk about how we need to forget about the “pecking order” within workplaces and how we need to focus on team social connectedness as a strategy to enhance teamwork and productivity.1 I found the analogy in the presenter’s talk so incredibly poignant for the work we do every day in hospital medicine. As we work to solve incredibly challenging problems daily, we do so among continuously changing and highly charged teams. How can we create our teams to be the most effective and productive to serve the greater good?

The speaker, Margaret Heffernan, is an entrepreneur and former CEO of five companies. She tells a story about a study performed by an evolutionary biologist by the name of William Muir of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind.2 Muir undertook a series of studies evaluating the social order and productivity of chickens (as measured by egg production) and the team characteristics that make chickens more or less productive. After watching flocks of chickens for several generations, he picked out the most productive chickens and put them all together in a “super flock.” He then watched their productivity over the next several generations and compared their productivity to those in the regular flock.

What he found was that the regular flock became more productive and most of the members of the super flock were dead!

The most productive members of the super flock had essentially pecked the other members to death. He surmised that the only reason the super chickens were initially productive was by suppressing the productivity of the original flock members. The chickens in the regular flock that were initially less aggressive (and less productive) over time sustained fewer injuries and were able to be more productive in the absence of super chickens. The energy that the animals had previously invested in negative behaviors (pecking, injuries, and healing) was redirected into positive behaviors (making eggs).

Muir and his team have gone on to research a tool to predict social aggressiveness and social agreeableness in individual animals. Those high on the socially agreeable scales (and low on the socially aggressive scales) are more valuable for producing highly effective teams of agricultural animals by enhancing group dynamics, social interactions, and actual productivity.

Backward Thinking

Heffernan argues that we have run most businesses (hospitals included) and many societies (at least capitalistic ones) in the super chicken model. In this model, we view leadership as a trait to be individually owned and perfected, and we think that leaders are supposed to have all the answers. In order to determine our leaders, we charge highly competent people to compete against one another as if in a talent contest. It has long been thought that to be successful as teams, we should recruit the best and brightest, pit them against on another, and see who wins, then promote the winner, put them in charge of everything, and give them all the resources they could want or need to be a super chicken.

But this model inevitably suppresses the remainder of the flock and leads to aggression and waste.

In many scenarios in our hospitals, physicians view themselves as and act like super chickens; we try to be the hardest working, the brightest, and the most powerful. How many times have we heard of or witnessed circumstances where a physician suppresses the candor or opinion from other disciplines on the care team? I think we all know physicians (ourselves included) who demand the role of decision maker and ignore the opinions or needs of the remainder of the team, including patients or their family.

Alternatives

So if we should not be subscribing to the super chicken theory, then what type of leadership structures should we be subscribing to within medical teams to produce the best outcomes for ourselves and for our patients and their families?

A study performed by MIT scientists gives us some insight. Researchers found that when random groups of people are given very difficult problems to solve (e.g., think about diagnostic dilemmas or very difficult patients), certain group attributes made it more likely that the group would be successful in solving these difficult problems. The groups that were most effective were not those with a few people with extremely high IQs or with the highest collective IQ. The teams that were most effective and able to solve difficult problems were those that showed high degrees of social sensitivity among members (i.e., empathy). The highest-performing teams gave roughly equal time to each member (e.g., think about physicians, pharmacists, social workers, case managers, consultants on a typical medical team). They also found the highest-performing teams had more women in them. (I feel so redeemed!)

In summary, what they learned from these experiments was that the most successful teams were more socially connected and more highly attuned and sensitive to one another. This is not to say that highly successful teams were leaderless. There is absolutely a vital role that leaders play in such teams. In Jim Collins’ famous book Good to Great, in studying leadership and teams, he did not find the best leaders were super chickens who autocratically made unilateral decisions. Instead, he found the best leaders function more like facilitators, having the humility and skill to draw out shared solutions from large participatory teams.3 Doesn’t this sound like how a hospitalist should run multidisciplinary rounds?

The other major attribute that the MIT researchers noticed about highly functional teams is that each and every member of the team was extremely willing and able to give and receive help. They found that teams with high mutual understanding and trust were more likely to seamlessly—and almost effortlessly—give and receive help from one another. They ended up acting as one another’s social support network. If any team member was confronted by a difficult problem or situation, each felt confident that it could be easily solved with the collective skill and wisdom of the team.

As a result of such research, some companies have developed and implemented strategies to enhance such social capital, such as synchronizing coffee breaks and disallowing coffee mugs at individual desks. These companies consider it a vital strategic mission to ensure that team members get to know and understand one another and that they serve as a social support network at work. They believe that it is reliance and interdependency that ensures trust and enhances productivity.

So what really matters is the mortar, not just the bricks.

HM Takeaway

For hospital medicine teams, what we need to do is accept that teams work best when every member has a voice and is valued. When others look to us (usually seen as team leaders) to make all the decisions (as if we are super chickens), we need to empower our team members to make decisions with us.

We need to actively work toward this model of being a team leader, break any cycles of dependency that we have set up, and produce better outcomes.

We need to avoid acting like super chickens and appreciate and empower a true team effort.

We need to stop accepting that management and promotions occur by talent contests that pit employees against one another and insist that rivalry at every level has to be replaced by social capital and social connectedness.

Only then will our leadership result in creating effective and productive bricks and mortar. TH

References

- Heffernan M. Margaret Heffernan: why it’s time to forget the pecking order at work. TED Talks. June 16, 2015. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vyn_xLrtZaY&feature=youtu.be.

- Steeves SA. Scientists find method to pick non-competitive animals, improve production. Available at: https://news.uns.purdue.edu/x/2007a/070212MuirSelection.html.

- Collins J. Good to Great. New York, N.Y.: HarperBusiness; 2011.

10 ways EHRs lead to burnout

LAS VEGAS – Doctors are dreading what some have started to call EHR "pajama time.”

“That’s the hour or two that physicians are spending – every night after their kids go to bed – finishing up their documentation, clearing out their in-box,” according to Dr. Christine Sinsky, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association.

At a session held in conjunction with the annual meeting of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, Dr. Sinsky spoke about how electronic health records have not lived up to their promise of helping streamline patient care and instead have added hours and headaches to most physicians’ days.

Data on the impact of EHR systems on physicians’ workflows and satisfaction is beginning to accumulate, she said. University of Wisconsin researchers studying the impact of EHR systems on physicians’ workflow and lives looked at how often and when doctors were accessing their patients’ medical records, she said. What they found was that so many doctors don’t have enough time in their days to finish their documentation, so they spend their evenings and weekends finishing up. Their preliminary findings were presented in 2015 at a primary care research meeting.

Dr. Sinsky said the researchers see “a bump” of time spent on Saturday nights.

“I call that ‘date night’. That Saturday night belongs to Epic, Cerner, or McKesson,” she said sarcastically. “Well, I don’t want my doctor on her electronic health record on a Saturday night. I want my doctor having fun on Saturday night, because I want her to love her job.”

That same study “found that primary care physicians were spending 38 hours a month after hours doing data entry work,” in other words “working a full extra week every month doing documentation after hours, between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m.,” said Dr. Sinky, who is also an internist in Dubuque, Iowa.

Here are 10 ways EHRs contribute to more work, Dr. Sinsky said:

1. Too many clicks. “It takes 33 clicks to order and record a flu shot. And in the emergency room, it takes 4,000 clicks to get through the day for a 10-hour shift,” Dr. Sinsky said. “Studies have shown that physicians are spending 44% of their day doing data entry work, [but] 28% of the day with their patient.”

In her own EHR, she said, “it took 21 clicks, eight scrolls, and five screens just to compose the billing invoice, and within that EHR, the responsibility, which used to be a clerical responsibility, has transferred many things to the physician. All of those clicks, all those screens, and all those minutes add up.”

2. Note bloat. With her current EHR, Dr. Sinksy said, “I have six pages of notes for an upper respiratory infection.” This is not efficient. She offered another example: “I had a patient recently who I sent to a local university,” Dr. Sinsky said. “I got back an enormous note, about 12 pages long. But I still didn’t know, at the end of it. Did she have cancer, or not?”

3. Poor workflow. Today’s EHRs have a workflow that doesn’t match how clinicians work, she said. “Right now, many clinicians are encountering these very rigid workflows that don’t meet the patient’s need and don’t meet the provider’s need.” For example, “in some EHRs, the physician can’t look at any clinical data while dictating the note. This means that the physician has to rely on memory or print lab results, x-ray reports, medication lists, etc., in order to reference these data points in their clinic note.”

4. A lack of focus on the patient. Most EHRs lack a place for a photo of the patient and his or her family, and a place for the patient’s story, a deficiency that detracts from the value of the encounter.

5. No support for team care. Often, both a physician and a nurse or medical assistant need to add documentation to the EHR. Yet many systems are set up such that each party must log in, then log out, before another can contribute. “The nurse has to sign in and sign out; the doctor has to sign in and sign out. That’s about a 2-minute process, so it’s completely unworkable,” Dr. Sinsky said.

6. Distracted hikes to the printer. While most health care settings have installed the computer in the exam rooms, few have also installed a printer. “The doctor types up the exit summary, hits print, runs around the corner, down the hall, around the corner to the one printer, picks up the visit summary, goes back down the corner down the hall. Meanwhile, they’ve broken their bond with the patient and been interrupted several times on that journey.”

7. Single-use workstations. Doctors who can sit side by side with their nurses and talk about the patient as they’re working on the EHR can save 30 minutes per day. But most office practice setups don’t accommodate that interaction.

8. Small monitors. Being able to see a large display of information rather than a tiny swatch can save 20 minutes of physician time a day, Dr. Sinsky said.

9. A long sign-in process. Streamlining the way a doctor signs into a computer, perhaps with the use of technologies like the tap of one’s badge, “can save 14 minutes of physician time a day,” Dr. Sinsky said.

10. Underuse of medical and nursing students. Practices are beginning to hire premed and prenursing students as assistants who shadow the physician with each patient. While the physician is “giving undivided attention to the patient, the practice partner is cuing up the orders, doing the billing invoice ,and recording much of the encounter.” At the University of California, Los Angeles, researchers found that the use of these assistants saves 3 hours of physician time each day (JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174[7]:1190-3).

LAS VEGAS – Doctors are dreading what some have started to call EHR "pajama time.”

“That’s the hour or two that physicians are spending – every night after their kids go to bed – finishing up their documentation, clearing out their in-box,” according to Dr. Christine Sinsky, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association.

At a session held in conjunction with the annual meeting of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, Dr. Sinsky spoke about how electronic health records have not lived up to their promise of helping streamline patient care and instead have added hours and headaches to most physicians’ days.

Data on the impact of EHR systems on physicians’ workflows and satisfaction is beginning to accumulate, she said. University of Wisconsin researchers studying the impact of EHR systems on physicians’ workflow and lives looked at how often and when doctors were accessing their patients’ medical records, she said. What they found was that so many doctors don’t have enough time in their days to finish their documentation, so they spend their evenings and weekends finishing up. Their preliminary findings were presented in 2015 at a primary care research meeting.

Dr. Sinsky said the researchers see “a bump” of time spent on Saturday nights.

“I call that ‘date night’. That Saturday night belongs to Epic, Cerner, or McKesson,” she said sarcastically. “Well, I don’t want my doctor on her electronic health record on a Saturday night. I want my doctor having fun on Saturday night, because I want her to love her job.”

That same study “found that primary care physicians were spending 38 hours a month after hours doing data entry work,” in other words “working a full extra week every month doing documentation after hours, between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m.,” said Dr. Sinky, who is also an internist in Dubuque, Iowa.

Here are 10 ways EHRs contribute to more work, Dr. Sinsky said:

1. Too many clicks. “It takes 33 clicks to order and record a flu shot. And in the emergency room, it takes 4,000 clicks to get through the day for a 10-hour shift,” Dr. Sinsky said. “Studies have shown that physicians are spending 44% of their day doing data entry work, [but] 28% of the day with their patient.”

In her own EHR, she said, “it took 21 clicks, eight scrolls, and five screens just to compose the billing invoice, and within that EHR, the responsibility, which used to be a clerical responsibility, has transferred many things to the physician. All of those clicks, all those screens, and all those minutes add up.”

2. Note bloat. With her current EHR, Dr. Sinksy said, “I have six pages of notes for an upper respiratory infection.” This is not efficient. She offered another example: “I had a patient recently who I sent to a local university,” Dr. Sinsky said. “I got back an enormous note, about 12 pages long. But I still didn’t know, at the end of it. Did she have cancer, or not?”

3. Poor workflow. Today’s EHRs have a workflow that doesn’t match how clinicians work, she said. “Right now, many clinicians are encountering these very rigid workflows that don’t meet the patient’s need and don’t meet the provider’s need.” For example, “in some EHRs, the physician can’t look at any clinical data while dictating the note. This means that the physician has to rely on memory or print lab results, x-ray reports, medication lists, etc., in order to reference these data points in their clinic note.”

4. A lack of focus on the patient. Most EHRs lack a place for a photo of the patient and his or her family, and a place for the patient’s story, a deficiency that detracts from the value of the encounter.

5. No support for team care. Often, both a physician and a nurse or medical assistant need to add documentation to the EHR. Yet many systems are set up such that each party must log in, then log out, before another can contribute. “The nurse has to sign in and sign out; the doctor has to sign in and sign out. That’s about a 2-minute process, so it’s completely unworkable,” Dr. Sinsky said.

6. Distracted hikes to the printer. While most health care settings have installed the computer in the exam rooms, few have also installed a printer. “The doctor types up the exit summary, hits print, runs around the corner, down the hall, around the corner to the one printer, picks up the visit summary, goes back down the corner down the hall. Meanwhile, they’ve broken their bond with the patient and been interrupted several times on that journey.”

7. Single-use workstations. Doctors who can sit side by side with their nurses and talk about the patient as they’re working on the EHR can save 30 minutes per day. But most office practice setups don’t accommodate that interaction.

8. Small monitors. Being able to see a large display of information rather than a tiny swatch can save 20 minutes of physician time a day, Dr. Sinsky said.

9. A long sign-in process. Streamlining the way a doctor signs into a computer, perhaps with the use of technologies like the tap of one’s badge, “can save 14 minutes of physician time a day,” Dr. Sinsky said.

10. Underuse of medical and nursing students. Practices are beginning to hire premed and prenursing students as assistants who shadow the physician with each patient. While the physician is “giving undivided attention to the patient, the practice partner is cuing up the orders, doing the billing invoice ,and recording much of the encounter.” At the University of California, Los Angeles, researchers found that the use of these assistants saves 3 hours of physician time each day (JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174[7]:1190-3).

LAS VEGAS – Doctors are dreading what some have started to call EHR "pajama time.”

“That’s the hour or two that physicians are spending – every night after their kids go to bed – finishing up their documentation, clearing out their in-box,” according to Dr. Christine Sinsky, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association.

At a session held in conjunction with the annual meeting of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, Dr. Sinsky spoke about how electronic health records have not lived up to their promise of helping streamline patient care and instead have added hours and headaches to most physicians’ days.

Data on the impact of EHR systems on physicians’ workflows and satisfaction is beginning to accumulate, she said. University of Wisconsin researchers studying the impact of EHR systems on physicians’ workflow and lives looked at how often and when doctors were accessing their patients’ medical records, she said. What they found was that so many doctors don’t have enough time in their days to finish their documentation, so they spend their evenings and weekends finishing up. Their preliminary findings were presented in 2015 at a primary care research meeting.

Dr. Sinsky said the researchers see “a bump” of time spent on Saturday nights.

“I call that ‘date night’. That Saturday night belongs to Epic, Cerner, or McKesson,” she said sarcastically. “Well, I don’t want my doctor on her electronic health record on a Saturday night. I want my doctor having fun on Saturday night, because I want her to love her job.”

That same study “found that primary care physicians were spending 38 hours a month after hours doing data entry work,” in other words “working a full extra week every month doing documentation after hours, between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m.,” said Dr. Sinky, who is also an internist in Dubuque, Iowa.

Here are 10 ways EHRs contribute to more work, Dr. Sinsky said:

1. Too many clicks. “It takes 33 clicks to order and record a flu shot. And in the emergency room, it takes 4,000 clicks to get through the day for a 10-hour shift,” Dr. Sinsky said. “Studies have shown that physicians are spending 44% of their day doing data entry work, [but] 28% of the day with their patient.”

In her own EHR, she said, “it took 21 clicks, eight scrolls, and five screens just to compose the billing invoice, and within that EHR, the responsibility, which used to be a clerical responsibility, has transferred many things to the physician. All of those clicks, all those screens, and all those minutes add up.”

2. Note bloat. With her current EHR, Dr. Sinksy said, “I have six pages of notes for an upper respiratory infection.” This is not efficient. She offered another example: “I had a patient recently who I sent to a local university,” Dr. Sinsky said. “I got back an enormous note, about 12 pages long. But I still didn’t know, at the end of it. Did she have cancer, or not?”

3. Poor workflow. Today’s EHRs have a workflow that doesn’t match how clinicians work, she said. “Right now, many clinicians are encountering these very rigid workflows that don’t meet the patient’s need and don’t meet the provider’s need.” For example, “in some EHRs, the physician can’t look at any clinical data while dictating the note. This means that the physician has to rely on memory or print lab results, x-ray reports, medication lists, etc., in order to reference these data points in their clinic note.”

4. A lack of focus on the patient. Most EHRs lack a place for a photo of the patient and his or her family, and a place for the patient’s story, a deficiency that detracts from the value of the encounter.

5. No support for team care. Often, both a physician and a nurse or medical assistant need to add documentation to the EHR. Yet many systems are set up such that each party must log in, then log out, before another can contribute. “The nurse has to sign in and sign out; the doctor has to sign in and sign out. That’s about a 2-minute process, so it’s completely unworkable,” Dr. Sinsky said.

6. Distracted hikes to the printer. While most health care settings have installed the computer in the exam rooms, few have also installed a printer. “The doctor types up the exit summary, hits print, runs around the corner, down the hall, around the corner to the one printer, picks up the visit summary, goes back down the corner down the hall. Meanwhile, they’ve broken their bond with the patient and been interrupted several times on that journey.”

7. Single-use workstations. Doctors who can sit side by side with their nurses and talk about the patient as they’re working on the EHR can save 30 minutes per day. But most office practice setups don’t accommodate that interaction.

8. Small monitors. Being able to see a large display of information rather than a tiny swatch can save 20 minutes of physician time a day, Dr. Sinsky said.

9. A long sign-in process. Streamlining the way a doctor signs into a computer, perhaps with the use of technologies like the tap of one’s badge, “can save 14 minutes of physician time a day,” Dr. Sinsky said.

10. Underuse of medical and nursing students. Practices are beginning to hire premed and prenursing students as assistants who shadow the physician with each patient. While the physician is “giving undivided attention to the patient, the practice partner is cuing up the orders, doing the billing invoice ,and recording much of the encounter.” At the University of California, Los Angeles, researchers found that the use of these assistants saves 3 hours of physician time each day (JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174[7]:1190-3).

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM HIMSS16

Voluntary self-disclosure: Pros and cons of using the protocol

AUSTIN, TEX. – Using the federal government’s voluntary self-disclosure protocol to report potential program violations offers advantages and disadvantages.

On one hand, the protocol allows health providers to get in front of possible offenses and retain some control, according to Miami health law attorney Stephen H. Siegel. On the other hand, launching the process could draw increased government scrutiny to a practice.

However, it can pay to be safe, rather than sorry later, Mr. Siegel said at an American Health Lawyers Association meeting.

“You are far better [off] and in a much better position, being proactive than reactive,” Mr. Siegel said in an interview. “Being proactive is an indication that your intention is to do the right thing. Whereas reactive, certainly the government doesn’t view [your intention] that way.”

Several federal agencies offer voluntary disclosure protocols. The HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) self-disclosure protocol was created in 1998 to enable the self-disclosure of potential health care fraud. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services provides the voluntary self-disclosure protocol, which is limited to potential violations of the physician-self referral statute, also called the Stark Law. Self-disclosures can also be made to the Department of Justice, although the agency has no formal protocol.

Voluntary self-disclosure can limit the possibility of an external investigation and reduce criminal and civil liability, according to Mr. Siegel. In a self-disclosure case, doctors can typically expect to pay back 1.5 times the amount that was improperly paid by the government. Whereas, in a false claims act case, for example, physicians can wind up paying back treble damages, plus a fine of between $5,500 and $11,000. Other advantages to voluntary self-disclosure include an expedited resolution, better control over adverse publicity, and the neutralizing of whistle-blower threats and lawsuits.

Disadvantages include financial loss, potential reputation harm, no immunity from liability or prior commitments by government, and possible penalties for conduct that may have remained undiscovered and thus undisclosed.

“For the most part, doctors are not aware of [voluntary self-disclosure],” Mr. Siegel said in an interview. “They’re not using it. [However], I think voluntary disclosure is going to become more widely used as people realize the ability to control the risk associated with the process.”

A number of issues warrant voluntary self-disclosure in a practice setting: possible government overpayments, potential improper arrangements with service providers, demonstrable patient harm, falsification of medical records, medical directorship issues, inadequate staffing, or the practice of medicine without a license, among others.

Regardless of which agency handles the self-disclosure, the admission will likely make its way to other agencies.

“Be assured that the agencies are going to talk to each other,” Mr. Siegel said. “If you submit it to DOJ [Department of Justice], chances are, it’s going to go to OIG.”

After choosing which agency to direct the self-disclosure, submit a timely, complete, and transparent disclosure, he advised. Each disclosure protocol is specific. For example, the OIG requires the disclosing party to acknowledge that the conduct is a potential violation and explicitly identify the laws that were potentially violated. The disclosing party also must agree ensure that corrective actions are implemented and that potential misconduct has stopped by the time of disclosure or, for improper kickback arrangements, within 90 days of submission.

The process of voluntary self-disclosure can be slow, usually taking more than a year. The OIG and CMS also reserve the right to reject a voluntary disclosure, Mr. Siegel said. If the government has already initiated an investigation for instance, an agency may reject the self-disclosure.

The government considers a host of factors when choosing how to resolve a self-disclosure case including the effectiveness of preexisting compliance programs; the nature of the conduct and its financial impact; the doctor’s ability to repay; whether the discloser is a first‐time offender; whether the incident is isolated; efforts to correct the problem; the period of alleged conduct; how the matter was discovered; and the party’s level of cooperation.

Mr. Siegel stressed there are no guarantees about how a voluntary self-disclosure case may be settled and that the matter will depend on the circumstances.

“There is no one-size-fits-all approach to voluntary self‐disclosure,” he said. “These decisions should be made with the assistance of competent and experienced counsel.”

On Twitter @legal_med

AUSTIN, TEX. – Using the federal government’s voluntary self-disclosure protocol to report potential program violations offers advantages and disadvantages.

On one hand, the protocol allows health providers to get in front of possible offenses and retain some control, according to Miami health law attorney Stephen H. Siegel. On the other hand, launching the process could draw increased government scrutiny to a practice.

However, it can pay to be safe, rather than sorry later, Mr. Siegel said at an American Health Lawyers Association meeting.

“You are far better [off] and in a much better position, being proactive than reactive,” Mr. Siegel said in an interview. “Being proactive is an indication that your intention is to do the right thing. Whereas reactive, certainly the government doesn’t view [your intention] that way.”

Several federal agencies offer voluntary disclosure protocols. The HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) self-disclosure protocol was created in 1998 to enable the self-disclosure of potential health care fraud. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services provides the voluntary self-disclosure protocol, which is limited to potential violations of the physician-self referral statute, also called the Stark Law. Self-disclosures can also be made to the Department of Justice, although the agency has no formal protocol.

Voluntary self-disclosure can limit the possibility of an external investigation and reduce criminal and civil liability, according to Mr. Siegel. In a self-disclosure case, doctors can typically expect to pay back 1.5 times the amount that was improperly paid by the government. Whereas, in a false claims act case, for example, physicians can wind up paying back treble damages, plus a fine of between $5,500 and $11,000. Other advantages to voluntary self-disclosure include an expedited resolution, better control over adverse publicity, and the neutralizing of whistle-blower threats and lawsuits.

Disadvantages include financial loss, potential reputation harm, no immunity from liability or prior commitments by government, and possible penalties for conduct that may have remained undiscovered and thus undisclosed.

“For the most part, doctors are not aware of [voluntary self-disclosure],” Mr. Siegel said in an interview. “They’re not using it. [However], I think voluntary disclosure is going to become more widely used as people realize the ability to control the risk associated with the process.”

A number of issues warrant voluntary self-disclosure in a practice setting: possible government overpayments, potential improper arrangements with service providers, demonstrable patient harm, falsification of medical records, medical directorship issues, inadequate staffing, or the practice of medicine without a license, among others.

Regardless of which agency handles the self-disclosure, the admission will likely make its way to other agencies.

“Be assured that the agencies are going to talk to each other,” Mr. Siegel said. “If you submit it to DOJ [Department of Justice], chances are, it’s going to go to OIG.”

After choosing which agency to direct the self-disclosure, submit a timely, complete, and transparent disclosure, he advised. Each disclosure protocol is specific. For example, the OIG requires the disclosing party to acknowledge that the conduct is a potential violation and explicitly identify the laws that were potentially violated. The disclosing party also must agree ensure that corrective actions are implemented and that potential misconduct has stopped by the time of disclosure or, for improper kickback arrangements, within 90 days of submission.

The process of voluntary self-disclosure can be slow, usually taking more than a year. The OIG and CMS also reserve the right to reject a voluntary disclosure, Mr. Siegel said. If the government has already initiated an investigation for instance, an agency may reject the self-disclosure.

The government considers a host of factors when choosing how to resolve a self-disclosure case including the effectiveness of preexisting compliance programs; the nature of the conduct and its financial impact; the doctor’s ability to repay; whether the discloser is a first‐time offender; whether the incident is isolated; efforts to correct the problem; the period of alleged conduct; how the matter was discovered; and the party’s level of cooperation.

Mr. Siegel stressed there are no guarantees about how a voluntary self-disclosure case may be settled and that the matter will depend on the circumstances.

“There is no one-size-fits-all approach to voluntary self‐disclosure,” he said. “These decisions should be made with the assistance of competent and experienced counsel.”

On Twitter @legal_med

AUSTIN, TEX. – Using the federal government’s voluntary self-disclosure protocol to report potential program violations offers advantages and disadvantages.

On one hand, the protocol allows health providers to get in front of possible offenses and retain some control, according to Miami health law attorney Stephen H. Siegel. On the other hand, launching the process could draw increased government scrutiny to a practice.

However, it can pay to be safe, rather than sorry later, Mr. Siegel said at an American Health Lawyers Association meeting.

“You are far better [off] and in a much better position, being proactive than reactive,” Mr. Siegel said in an interview. “Being proactive is an indication that your intention is to do the right thing. Whereas reactive, certainly the government doesn’t view [your intention] that way.”

Several federal agencies offer voluntary disclosure protocols. The HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) self-disclosure protocol was created in 1998 to enable the self-disclosure of potential health care fraud. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services provides the voluntary self-disclosure protocol, which is limited to potential violations of the physician-self referral statute, also called the Stark Law. Self-disclosures can also be made to the Department of Justice, although the agency has no formal protocol.

Voluntary self-disclosure can limit the possibility of an external investigation and reduce criminal and civil liability, according to Mr. Siegel. In a self-disclosure case, doctors can typically expect to pay back 1.5 times the amount that was improperly paid by the government. Whereas, in a false claims act case, for example, physicians can wind up paying back treble damages, plus a fine of between $5,500 and $11,000. Other advantages to voluntary self-disclosure include an expedited resolution, better control over adverse publicity, and the neutralizing of whistle-blower threats and lawsuits.

Disadvantages include financial loss, potential reputation harm, no immunity from liability or prior commitments by government, and possible penalties for conduct that may have remained undiscovered and thus undisclosed.

“For the most part, doctors are not aware of [voluntary self-disclosure],” Mr. Siegel said in an interview. “They’re not using it. [However], I think voluntary disclosure is going to become more widely used as people realize the ability to control the risk associated with the process.”

A number of issues warrant voluntary self-disclosure in a practice setting: possible government overpayments, potential improper arrangements with service providers, demonstrable patient harm, falsification of medical records, medical directorship issues, inadequate staffing, or the practice of medicine without a license, among others.

Regardless of which agency handles the self-disclosure, the admission will likely make its way to other agencies.

“Be assured that the agencies are going to talk to each other,” Mr. Siegel said. “If you submit it to DOJ [Department of Justice], chances are, it’s going to go to OIG.”

After choosing which agency to direct the self-disclosure, submit a timely, complete, and transparent disclosure, he advised. Each disclosure protocol is specific. For example, the OIG requires the disclosing party to acknowledge that the conduct is a potential violation and explicitly identify the laws that were potentially violated. The disclosing party also must agree ensure that corrective actions are implemented and that potential misconduct has stopped by the time of disclosure or, for improper kickback arrangements, within 90 days of submission.

The process of voluntary self-disclosure can be slow, usually taking more than a year. The OIG and CMS also reserve the right to reject a voluntary disclosure, Mr. Siegel said. If the government has already initiated an investigation for instance, an agency may reject the self-disclosure.

The government considers a host of factors when choosing how to resolve a self-disclosure case including the effectiveness of preexisting compliance programs; the nature of the conduct and its financial impact; the doctor’s ability to repay; whether the discloser is a first‐time offender; whether the incident is isolated; efforts to correct the problem; the period of alleged conduct; how the matter was discovered; and the party’s level of cooperation.

Mr. Siegel stressed there are no guarantees about how a voluntary self-disclosure case may be settled and that the matter will depend on the circumstances.

“There is no one-size-fits-all approach to voluntary self‐disclosure,” he said. “These decisions should be made with the assistance of competent and experienced counsel.”

On Twitter @legal_med

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PHYSICIANS AND HOSPITALS LAW INSTITUTE

VIDEO: Medication reconciliation can improve patient outcomes

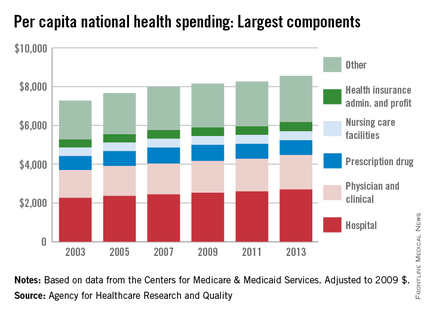

SAN DIEGO – Prescription medications are a major contributor to unnecessary health care spending.

According to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, retail spending on prescription drugs grew 12.2% to $297.7 billion in 2014, compared with the 2.4% growth in 2013. That’s one key reason why medication reconciliation should be performed at every inpatient and outpatient visit and prior to every hospital discharge, Dr. Aparna Kamath said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. “The focus should be on clear indications for each medication prescribed, substitution of generics when possible, and consideration of an individual patient’s insurance formulary and ability to meet out-of-pocket costs.”

A recent article in JAMA Internal Medicine discussed the practice of “deprescribing” in an effort to reduce the number of prescribed drugs (2015;175[5]:827-34). According to Dr. Kamath of the department of medicine at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., who was not involved with the article, deprescribing “means safely narrowing, discontinuing, or withdrawing medications for our patients. It has been shown that deprescribing might actually improve outpatient outcomes by making the medication list safer for our patients and hopefully also improve medication adherence by making them more affordable for our patients.”

The study authors proposed a five-step protocol for deprescribing:

• Ascertain all drugs the patient is currently taking and the reasons for each one.

• Consider overall risk of drug-induced harm in individual patients in determining the required intensity of deprescribing intervention.

• Assess each drug in regard to its current or future benefit potential, compared with current or future harm or burden potential.

• Prioritize drugs for discontinuation that have the lowest benefit-harm ratio and lowest likelihood of adverse withdrawal reactions or disease rebound syndromes.

• Implement a discontinuation regimen and monitor patients closely for improvement in outcomes or onset of adverse effects.

According to Dr. Kamath, other medication reconciliation strategies include referring patients to a social worker to inquire about drug assistance programs; following up with the patient’s primary care or prescribing physician; partnering with pharmacists; and educating patients about variance in prescription drug prices. “I think it’s important to inform the patients that these drugs are priced differently in different pharmacies,” she said. “According to Consumer Reports, we should ask the patient to shop around, maybe call the medication pharmacies in their local area to find out where they can find the drugs at a most affordable price. We can also advise our patients to ask for discounts or coupons, and check for monthly price changes,” Dr. Kamath said. She recommended the following websites, which allow patients to compare costs and/or inquire about discounts:

• https://www.rxpricequotes.com.

• https://www.blinkhealth.com.

Dr. Kamath reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Prescription medications are a major contributor to unnecessary health care spending.

According to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, retail spending on prescription drugs grew 12.2% to $297.7 billion in 2014, compared with the 2.4% growth in 2013. That’s one key reason why medication reconciliation should be performed at every inpatient and outpatient visit and prior to every hospital discharge, Dr. Aparna Kamath said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. “The focus should be on clear indications for each medication prescribed, substitution of generics when possible, and consideration of an individual patient’s insurance formulary and ability to meet out-of-pocket costs.”

A recent article in JAMA Internal Medicine discussed the practice of “deprescribing” in an effort to reduce the number of prescribed drugs (2015;175[5]:827-34). According to Dr. Kamath of the department of medicine at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., who was not involved with the article, deprescribing “means safely narrowing, discontinuing, or withdrawing medications for our patients. It has been shown that deprescribing might actually improve outpatient outcomes by making the medication list safer for our patients and hopefully also improve medication adherence by making them more affordable for our patients.”

The study authors proposed a five-step protocol for deprescribing:

• Ascertain all drugs the patient is currently taking and the reasons for each one.

• Consider overall risk of drug-induced harm in individual patients in determining the required intensity of deprescribing intervention.

• Assess each drug in regard to its current or future benefit potential, compared with current or future harm or burden potential.

• Prioritize drugs for discontinuation that have the lowest benefit-harm ratio and lowest likelihood of adverse withdrawal reactions or disease rebound syndromes.

• Implement a discontinuation regimen and monitor patients closely for improvement in outcomes or onset of adverse effects.

According to Dr. Kamath, other medication reconciliation strategies include referring patients to a social worker to inquire about drug assistance programs; following up with the patient’s primary care or prescribing physician; partnering with pharmacists; and educating patients about variance in prescription drug prices. “I think it’s important to inform the patients that these drugs are priced differently in different pharmacies,” she said. “According to Consumer Reports, we should ask the patient to shop around, maybe call the medication pharmacies in their local area to find out where they can find the drugs at a most affordable price. We can also advise our patients to ask for discounts or coupons, and check for monthly price changes,” Dr. Kamath said. She recommended the following websites, which allow patients to compare costs and/or inquire about discounts:

• https://www.rxpricequotes.com.

• https://www.blinkhealth.com.

Dr. Kamath reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Prescription medications are a major contributor to unnecessary health care spending.

According to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, retail spending on prescription drugs grew 12.2% to $297.7 billion in 2014, compared with the 2.4% growth in 2013. That’s one key reason why medication reconciliation should be performed at every inpatient and outpatient visit and prior to every hospital discharge, Dr. Aparna Kamath said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. “The focus should be on clear indications for each medication prescribed, substitution of generics when possible, and consideration of an individual patient’s insurance formulary and ability to meet out-of-pocket costs.”

A recent article in JAMA Internal Medicine discussed the practice of “deprescribing” in an effort to reduce the number of prescribed drugs (2015;175[5]:827-34). According to Dr. Kamath of the department of medicine at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., who was not involved with the article, deprescribing “means safely narrowing, discontinuing, or withdrawing medications for our patients. It has been shown that deprescribing might actually improve outpatient outcomes by making the medication list safer for our patients and hopefully also improve medication adherence by making them more affordable for our patients.”

The study authors proposed a five-step protocol for deprescribing:

• Ascertain all drugs the patient is currently taking and the reasons for each one.

• Consider overall risk of drug-induced harm in individual patients in determining the required intensity of deprescribing intervention.

• Assess each drug in regard to its current or future benefit potential, compared with current or future harm or burden potential.

• Prioritize drugs for discontinuation that have the lowest benefit-harm ratio and lowest likelihood of adverse withdrawal reactions or disease rebound syndromes.

• Implement a discontinuation regimen and monitor patients closely for improvement in outcomes or onset of adverse effects.

According to Dr. Kamath, other medication reconciliation strategies include referring patients to a social worker to inquire about drug assistance programs; following up with the patient’s primary care or prescribing physician; partnering with pharmacists; and educating patients about variance in prescription drug prices. “I think it’s important to inform the patients that these drugs are priced differently in different pharmacies,” she said. “According to Consumer Reports, we should ask the patient to shop around, maybe call the medication pharmacies in their local area to find out where they can find the drugs at a most affordable price. We can also advise our patients to ask for discounts or coupons, and check for monthly price changes,” Dr. Kamath said. She recommended the following websites, which allow patients to compare costs and/or inquire about discounts:

• https://www.rxpricequotes.com.

• https://www.blinkhealth.com.

Dr. Kamath reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 16

FDA proposes ban on powdered gloves

The Food and Drug Administration has proposed a ban on most powdered gloves used during surgery and for patient examination, and on absorbable powder used for lubricating surgeons’ gloves.

Aerosolized glove powder on natural rubber latex gloves can cause respiratory allergic reactions, and while powdered synthetic gloves don’t present the risk of allergic reactions, all powdered gloves have been associated with numerous potentially serious adverse events, including severe airway inflammation, wound inflammation, and postsurgical adhesions, according to an FDA statement.

The proposed ban would not apply to powdered radiographic protection gloves; the agency is not aware of any such gloves that are currently on the market. The ban also would not affect non-powdered gloves.

The decision to move forward with the proposed ban was based on a determination that the affected products “are dangerous and present an unreasonable and substantial risk,” according to the statement.

In making this determination, the FDA considered the available evidence, including a literature review and the 285 comments received on a February 2011 Federal Register Notice.

That notice announced the establishment of a public docket to receive comments related to powdered gloves and followed the FDA’s receipt of two citizen petitions requesting a ban on such gloves because of the adverse health effects associated with use of the gloves. The comments overwhelmingly supported a warning or ban.

The FDA determined that the risks associated with powdered gloves cannot be corrected through new or updated labeling, and thus moved forward with the proposed ban.

“This ban is about protecting patients and health care professionals from a danger they might not even be aware of,” Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health said in the statement. “We take bans very seriously and only take this action when we feel it’s necessary to protect the public health.”

In fact, should this ban be put into place, it would be only the second such ban; the first was the 1983 ban of prosthetic hair fibers, which were found to provide no public health benefit. The benefits cited for powdered gloves were almost entirely related to greater ease of putting the gloves on and taking them off, Eric Pahon of the FDA said in an interview.

A ban on the gloves was not proposed sooner in part because when concerns were first raised about the risks associated with powdered gloves, a ban would have created a shortage, and the risks of a glove shortage outweighed the benefits of banning the gloves, Mr. Pahon said.

However, a recent economic analysis conducted by the FDA because of the critical role medical gloves play in protecting patients and health care providers showed that a powdered glove ban would not cause a glove shortage or have a significant economic impact, and that a ban would not be likely to affect medical practice since numerous non-powdered gloves options are now available, the agency noted.

The proposed rule will be available online March 22 at the Federal Register, and is open for public comment for 90 days.

If finalized, the powdered gloves and absorbable powder used for lubricating surgeons’ gloves would be removed from the marketplace.

The Food and Drug Administration has proposed a ban on most powdered gloves used during surgery and for patient examination, and on absorbable powder used for lubricating surgeons’ gloves.

Aerosolized glove powder on natural rubber latex gloves can cause respiratory allergic reactions, and while powdered synthetic gloves don’t present the risk of allergic reactions, all powdered gloves have been associated with numerous potentially serious adverse events, including severe airway inflammation, wound inflammation, and postsurgical adhesions, according to an FDA statement.

The proposed ban would not apply to powdered radiographic protection gloves; the agency is not aware of any such gloves that are currently on the market. The ban also would not affect non-powdered gloves.

The decision to move forward with the proposed ban was based on a determination that the affected products “are dangerous and present an unreasonable and substantial risk,” according to the statement.

In making this determination, the FDA considered the available evidence, including a literature review and the 285 comments received on a February 2011 Federal Register Notice.

That notice announced the establishment of a public docket to receive comments related to powdered gloves and followed the FDA’s receipt of two citizen petitions requesting a ban on such gloves because of the adverse health effects associated with use of the gloves. The comments overwhelmingly supported a warning or ban.

The FDA determined that the risks associated with powdered gloves cannot be corrected through new or updated labeling, and thus moved forward with the proposed ban.

“This ban is about protecting patients and health care professionals from a danger they might not even be aware of,” Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health said in the statement. “We take bans very seriously and only take this action when we feel it’s necessary to protect the public health.”

In fact, should this ban be put into place, it would be only the second such ban; the first was the 1983 ban of prosthetic hair fibers, which were found to provide no public health benefit. The benefits cited for powdered gloves were almost entirely related to greater ease of putting the gloves on and taking them off, Eric Pahon of the FDA said in an interview.

A ban on the gloves was not proposed sooner in part because when concerns were first raised about the risks associated with powdered gloves, a ban would have created a shortage, and the risks of a glove shortage outweighed the benefits of banning the gloves, Mr. Pahon said.

However, a recent economic analysis conducted by the FDA because of the critical role medical gloves play in protecting patients and health care providers showed that a powdered glove ban would not cause a glove shortage or have a significant economic impact, and that a ban would not be likely to affect medical practice since numerous non-powdered gloves options are now available, the agency noted.

The proposed rule will be available online March 22 at the Federal Register, and is open for public comment for 90 days.

If finalized, the powdered gloves and absorbable powder used for lubricating surgeons’ gloves would be removed from the marketplace.

The Food and Drug Administration has proposed a ban on most powdered gloves used during surgery and for patient examination, and on absorbable powder used for lubricating surgeons’ gloves.

Aerosolized glove powder on natural rubber latex gloves can cause respiratory allergic reactions, and while powdered synthetic gloves don’t present the risk of allergic reactions, all powdered gloves have been associated with numerous potentially serious adverse events, including severe airway inflammation, wound inflammation, and postsurgical adhesions, according to an FDA statement.

The proposed ban would not apply to powdered radiographic protection gloves; the agency is not aware of any such gloves that are currently on the market. The ban also would not affect non-powdered gloves.

The decision to move forward with the proposed ban was based on a determination that the affected products “are dangerous and present an unreasonable and substantial risk,” according to the statement.

In making this determination, the FDA considered the available evidence, including a literature review and the 285 comments received on a February 2011 Federal Register Notice.

That notice announced the establishment of a public docket to receive comments related to powdered gloves and followed the FDA’s receipt of two citizen petitions requesting a ban on such gloves because of the adverse health effects associated with use of the gloves. The comments overwhelmingly supported a warning or ban.

The FDA determined that the risks associated with powdered gloves cannot be corrected through new or updated labeling, and thus moved forward with the proposed ban.

“This ban is about protecting patients and health care professionals from a danger they might not even be aware of,” Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health said in the statement. “We take bans very seriously and only take this action when we feel it’s necessary to protect the public health.”

In fact, should this ban be put into place, it would be only the second such ban; the first was the 1983 ban of prosthetic hair fibers, which were found to provide no public health benefit. The benefits cited for powdered gloves were almost entirely related to greater ease of putting the gloves on and taking them off, Eric Pahon of the FDA said in an interview.

A ban on the gloves was not proposed sooner in part because when concerns were first raised about the risks associated with powdered gloves, a ban would have created a shortage, and the risks of a glove shortage outweighed the benefits of banning the gloves, Mr. Pahon said.

However, a recent economic analysis conducted by the FDA because of the critical role medical gloves play in protecting patients and health care providers showed that a powdered glove ban would not cause a glove shortage or have a significant economic impact, and that a ban would not be likely to affect medical practice since numerous non-powdered gloves options are now available, the agency noted.

The proposed rule will be available online March 22 at the Federal Register, and is open for public comment for 90 days.

If finalized, the powdered gloves and absorbable powder used for lubricating surgeons’ gloves would be removed from the marketplace.

Feds launch phase 2 of HIPAA audits

The federal government has launched the second phase of its HIPAA Audit Program and will soon be identifying health providers it plans to target.

For the 2016 Phase 2 HIPAA Audit Program, auditors will review policies and procedures enacted by covered entities and their business associates to meet selected standards of the Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Rules, according to a March 21 announcement by the Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

Physicians and other covered entities can expect an email at some point this year requesting that updated contact information be provided to the OCR. The office will then send health providers a pre-audit questionnaire to gather data about the practice’s size, type, and operations, according to the announcement. The government will use the data as well as other information to create audit subject pools. If an entity does not respond to the OCR’s contact request or the pre-audit questionnaire, the agency will use publicly available information about the practice.

Every covered entity and business associate is eligible for an audit, the OCR noted. For Phase 2, the government plans to identify health providers and business associates that represent a wide range of health care providers, health plans, health care clearinghouses and business associates to access HIPAA compliance across the industry. Sampling criteria for auditee selection will include size of the entity, affiliation with other health care organizations, whether an organization is public or private, geographic factors, and present enforcement activity with OCR. Entities with open complaints or that are currently undergoing investigations will not be chosen.

The first set of audits will be desk audits of covered entities followed by a second round of desk audits of business associates, OCR stated. OCR plans to complete all desk audits by December 2016. A third set of audits will be on site and will examine a broader scope of requirements under the HIPAA rules. Some desk auditees may be subject to a subsequent on-site audit, the government noted.

A list of frequently asked questions about the 2016 Phase 2 HIPAA Audit Program can be found on the OCR’s website.

Round 2 of the HIPAA audits follows a pilot program launched in 2011 and 2012 by OCR that assessed HIPAA controls and processes implemented by 115 covered entities. The second phase will draw on the results and experiences learned from the pilot program, according to OCR.

On Twitter @legal_med

The federal government has launched the second phase of its HIPAA Audit Program and will soon be identifying health providers it plans to target.

For the 2016 Phase 2 HIPAA Audit Program, auditors will review policies and procedures enacted by covered entities and their business associates to meet selected standards of the Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Rules, according to a March 21 announcement by the Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights (OCR).