User login

Nonhealing Ulcerative Hand Wound

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

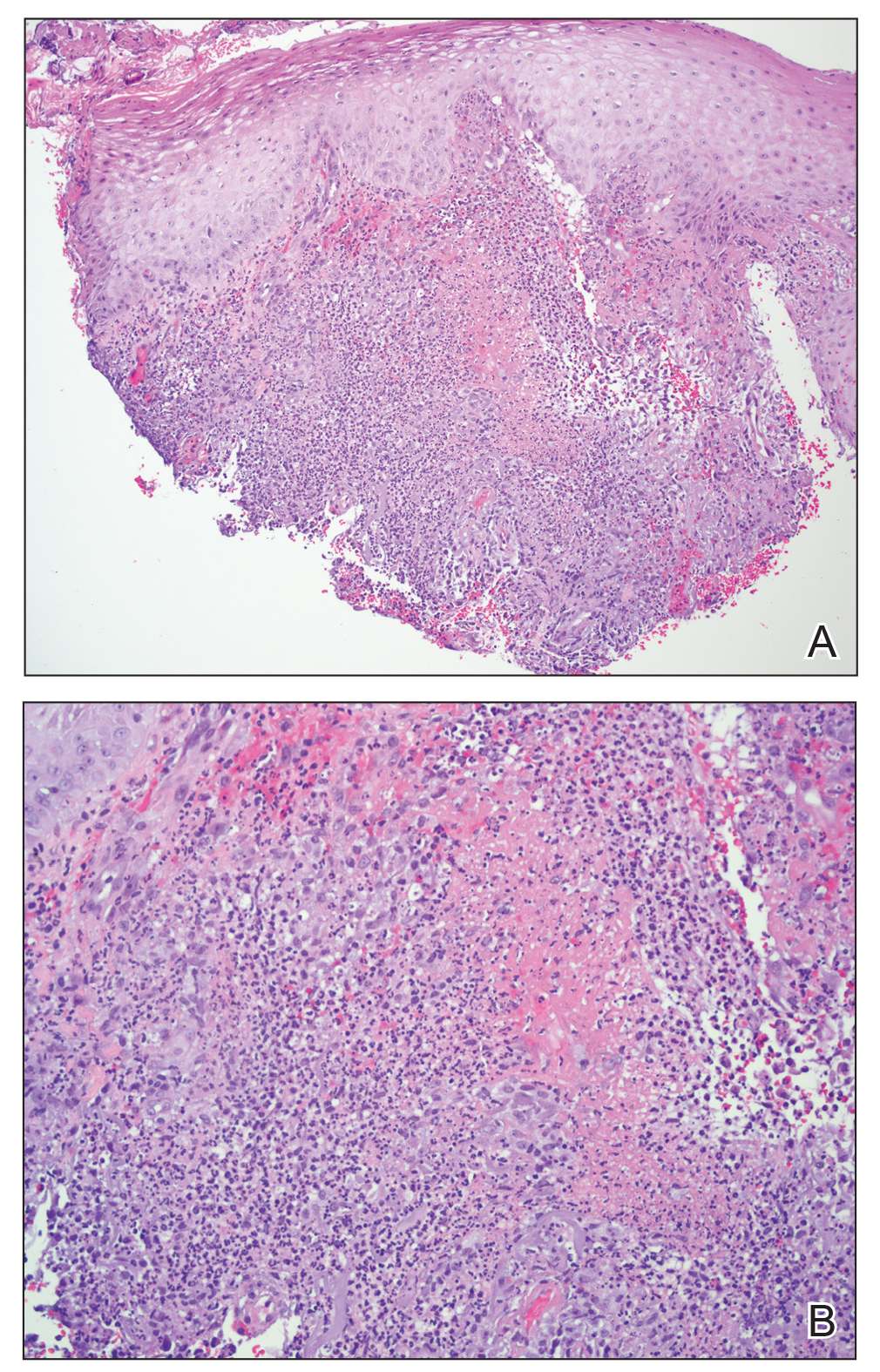

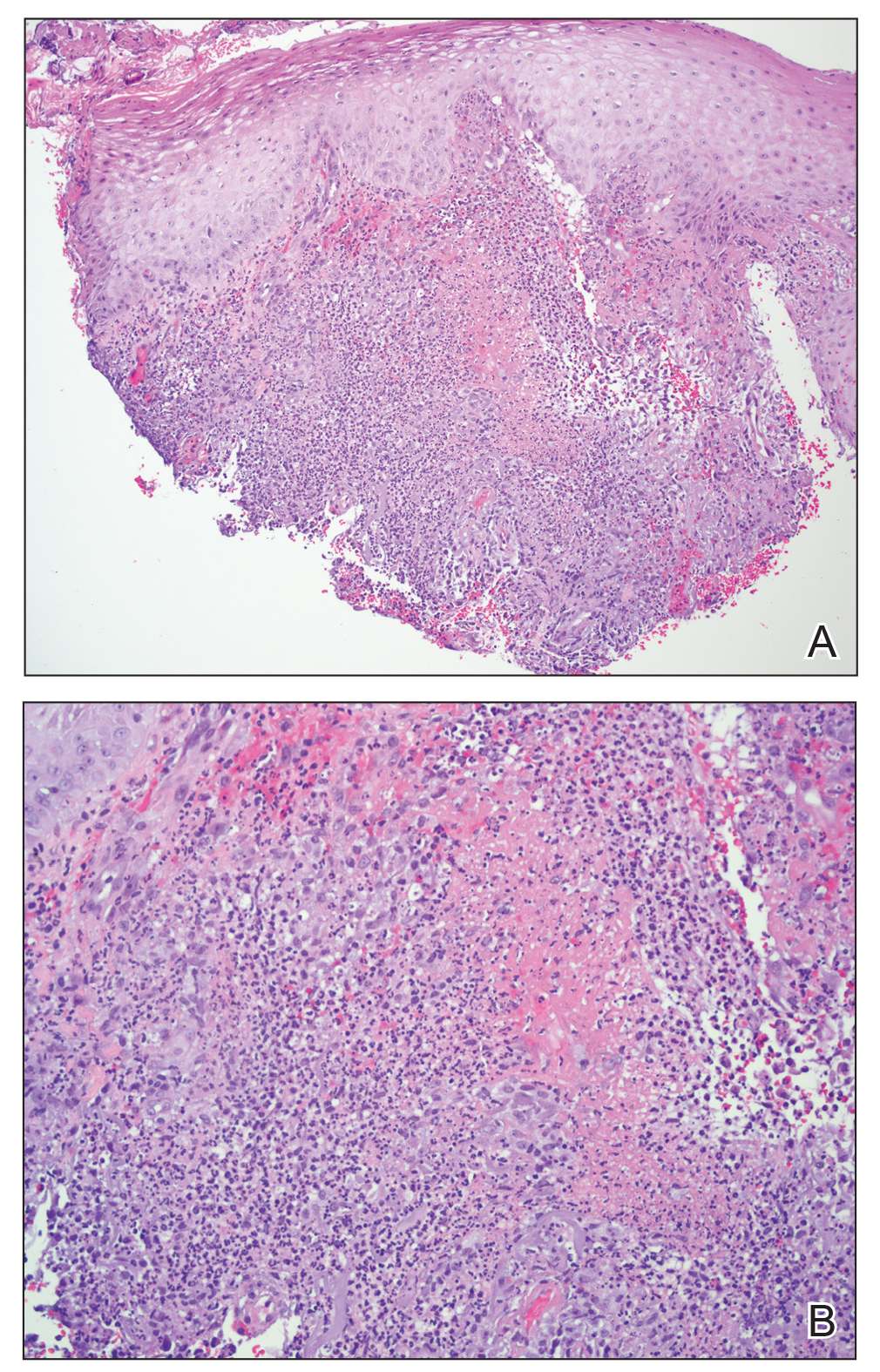

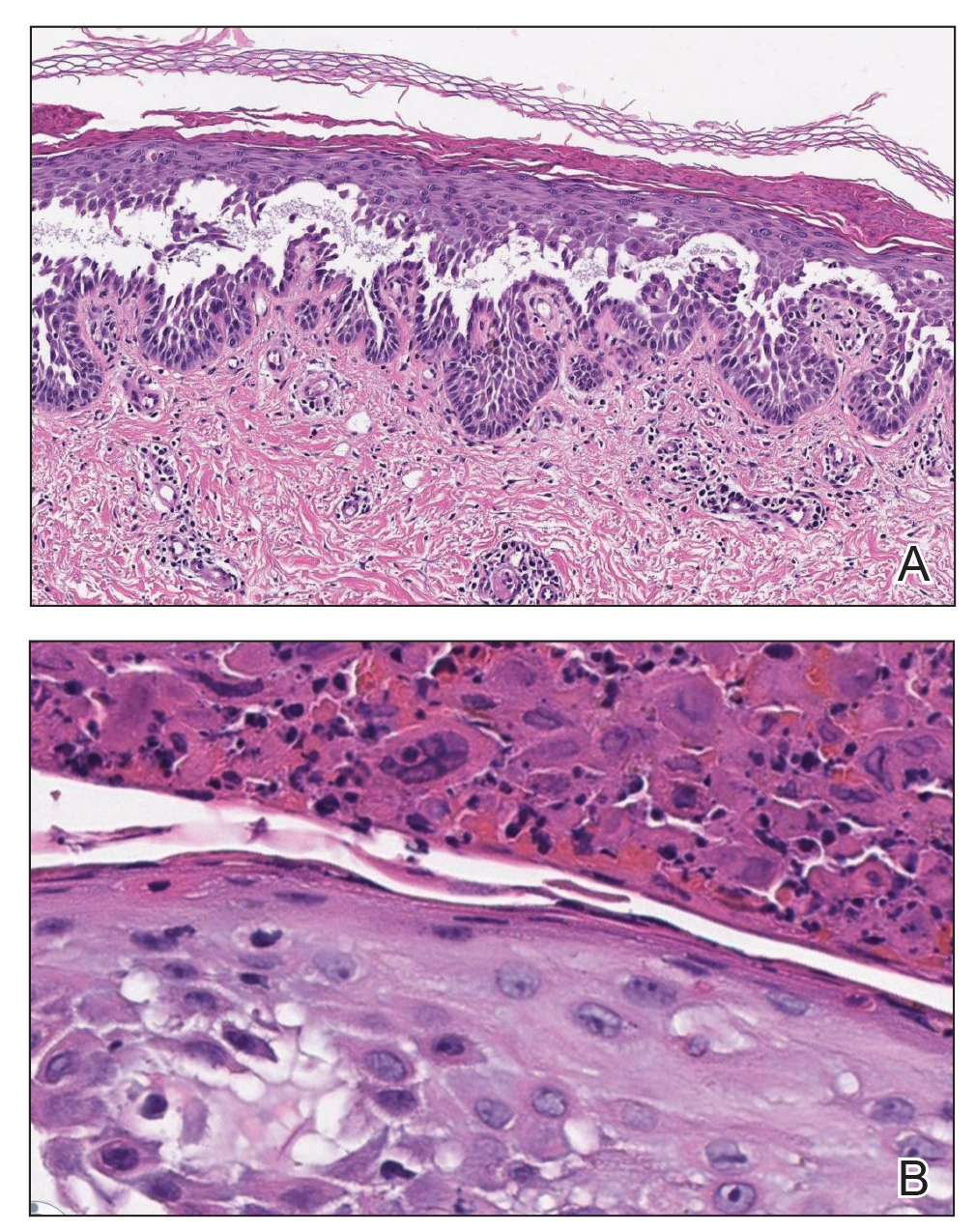

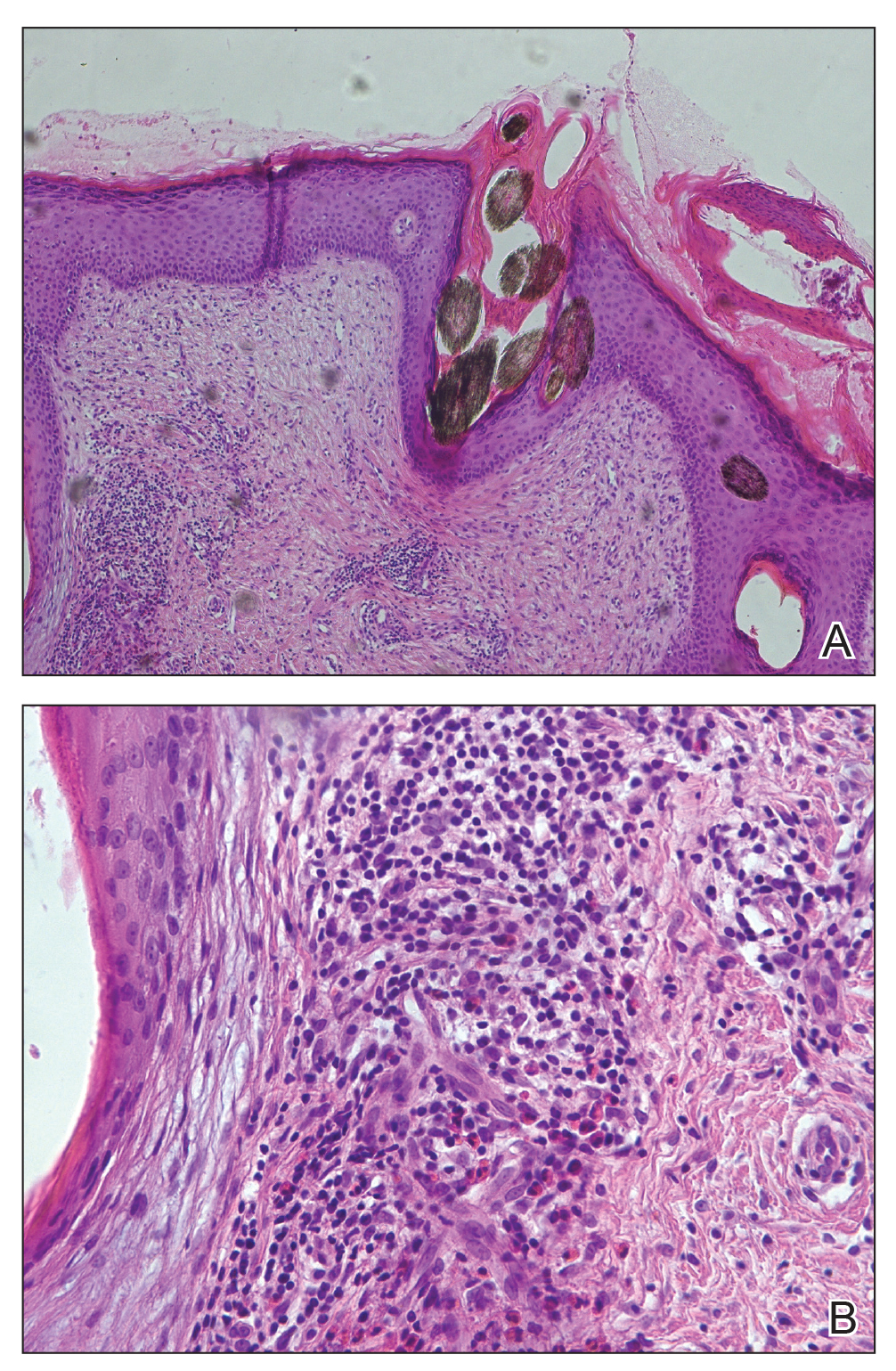

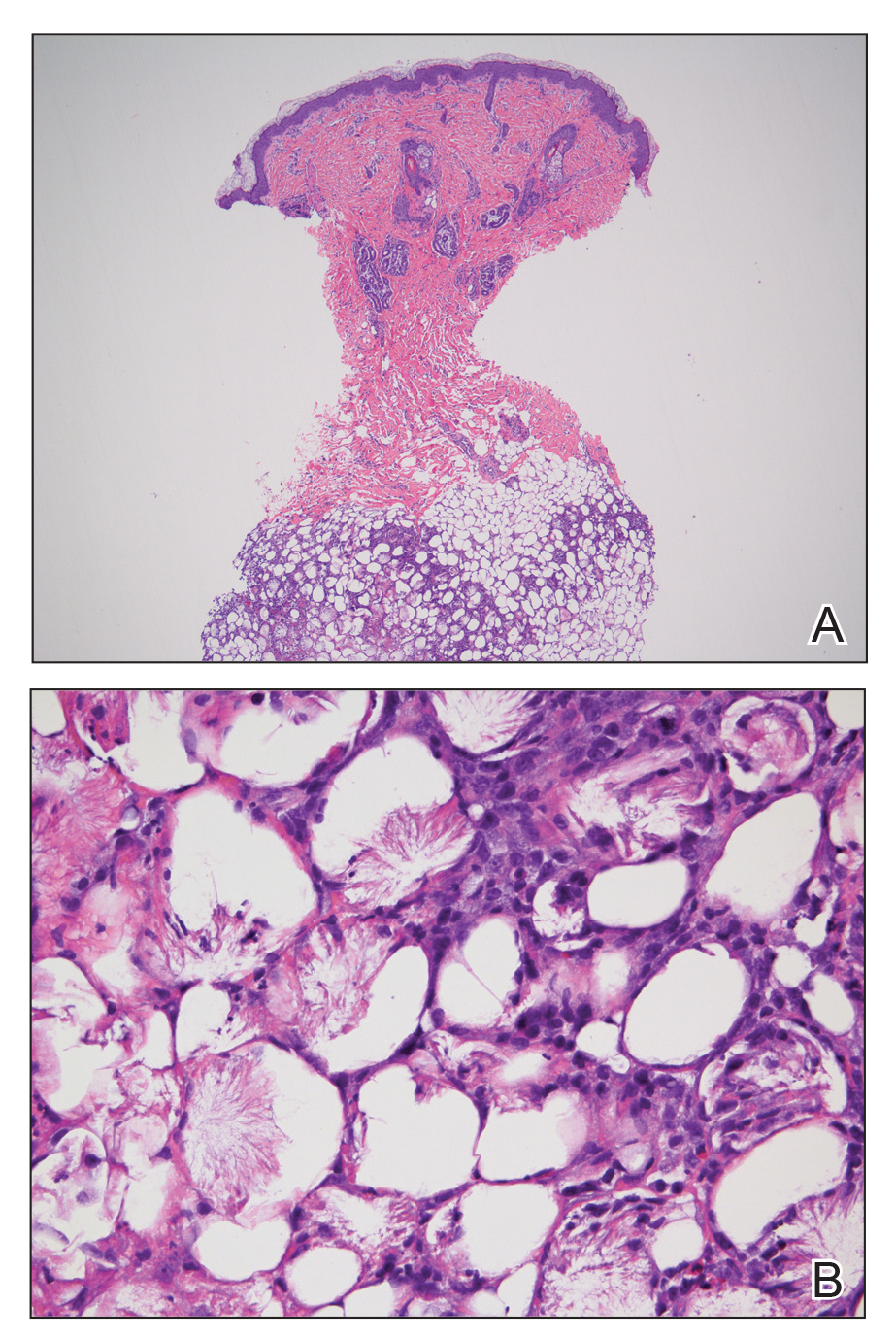

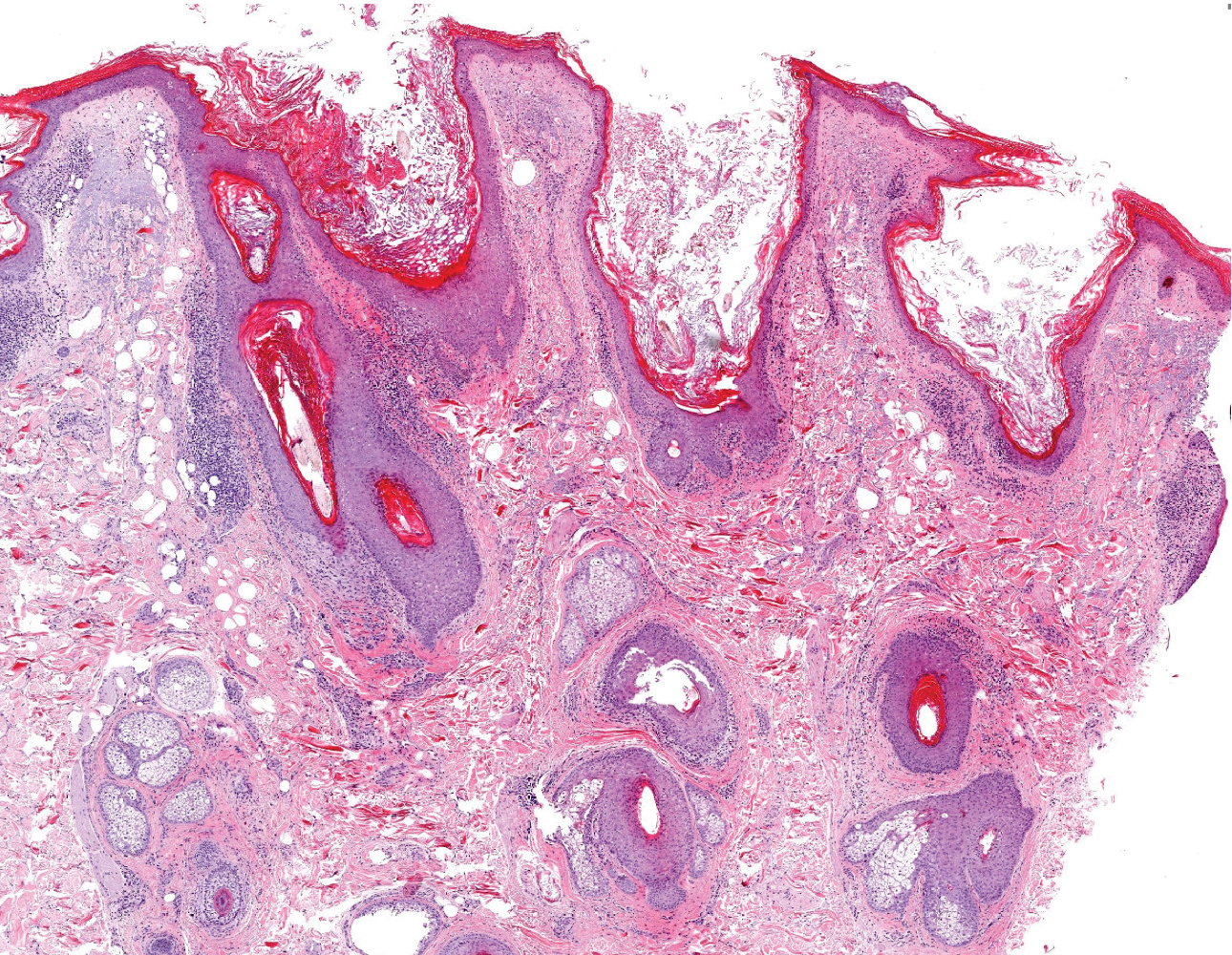

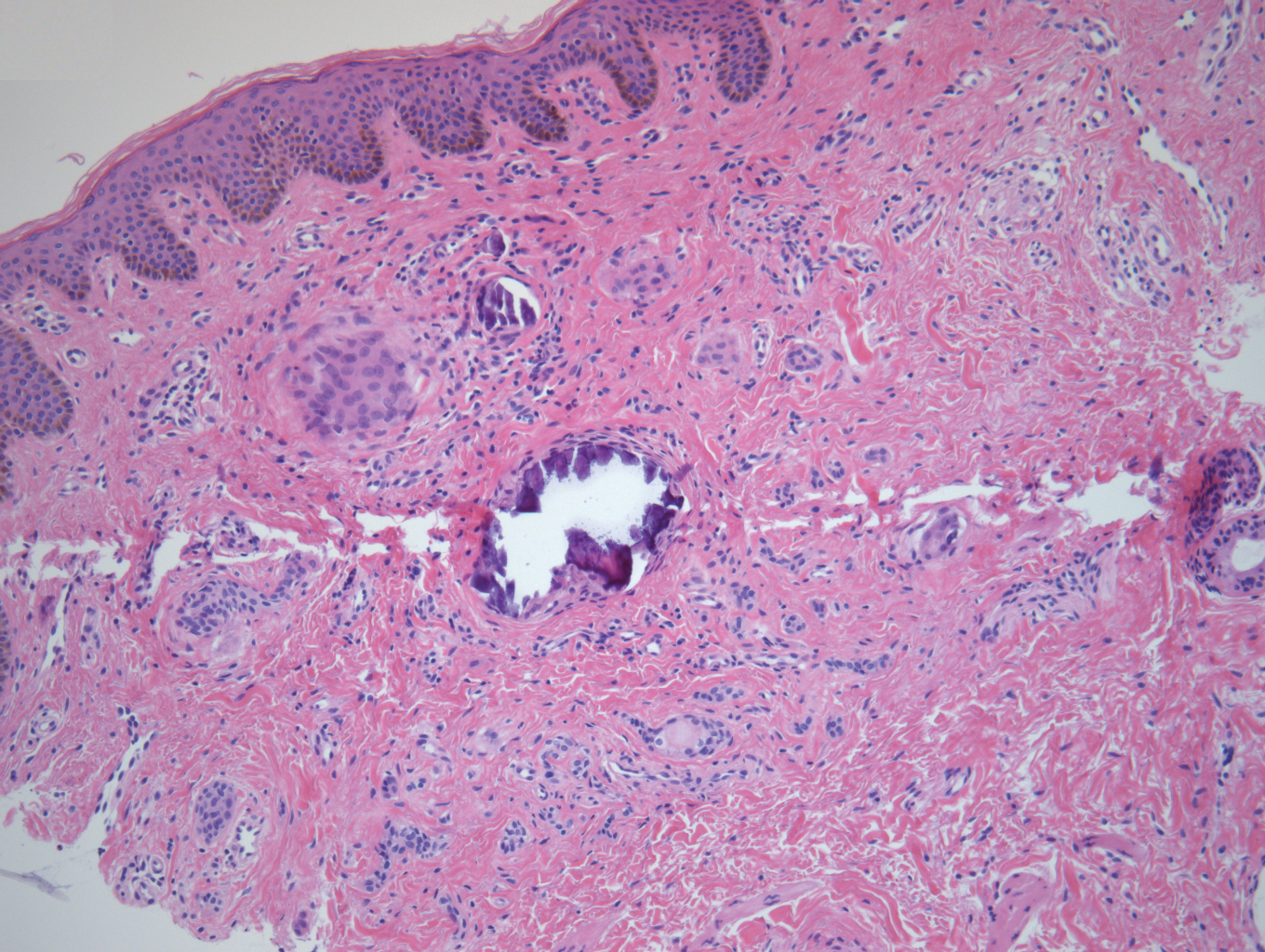

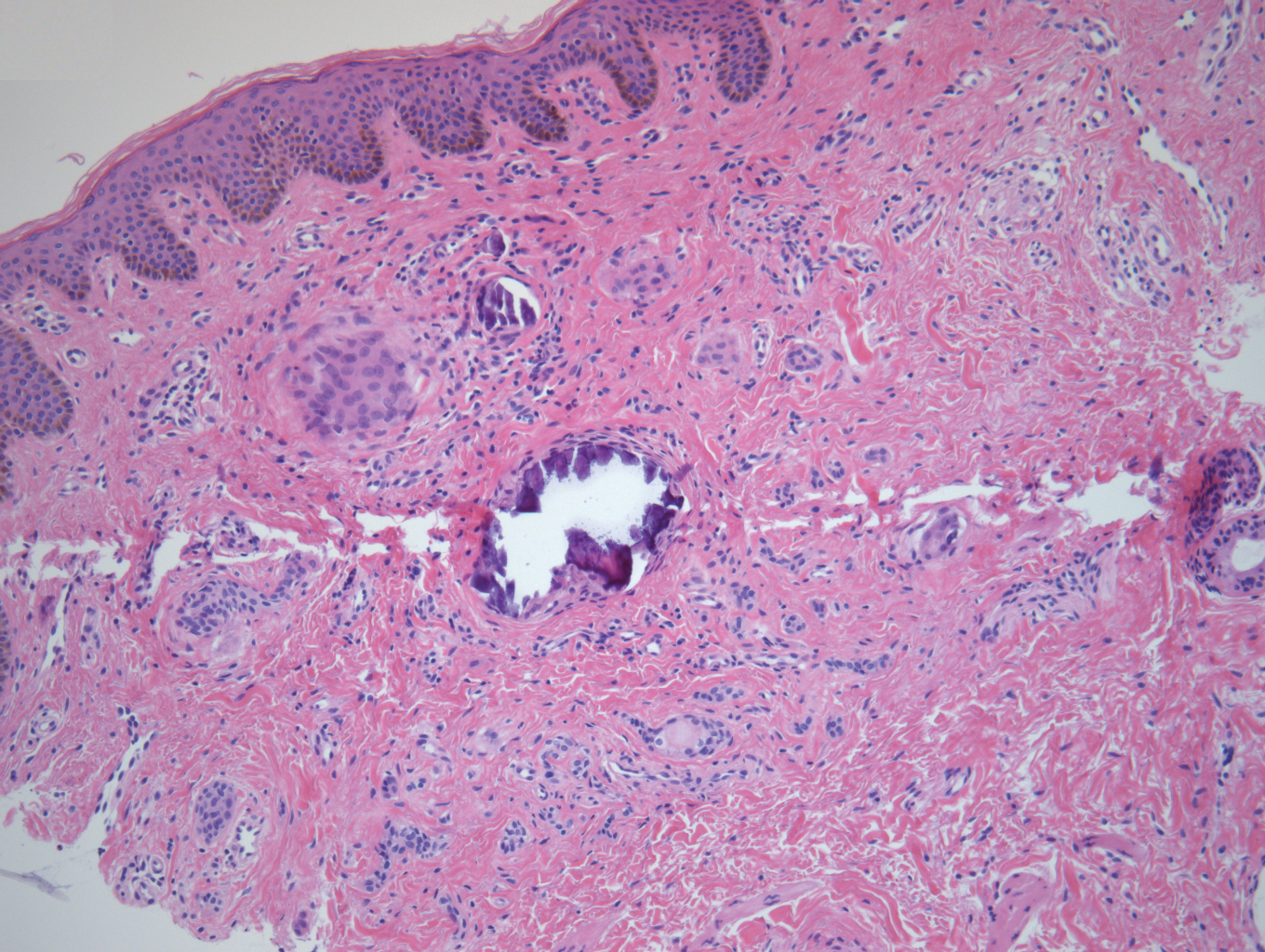

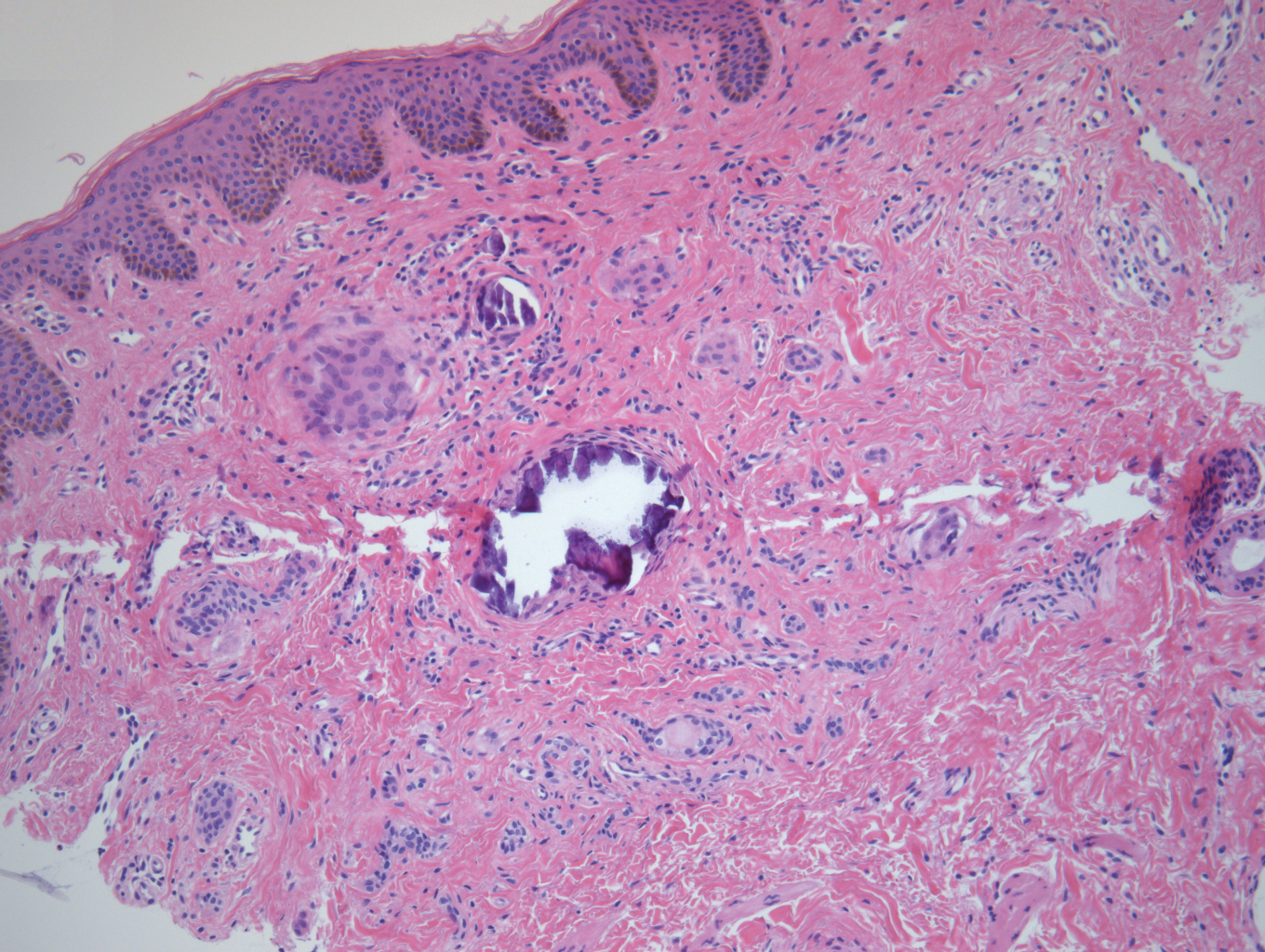

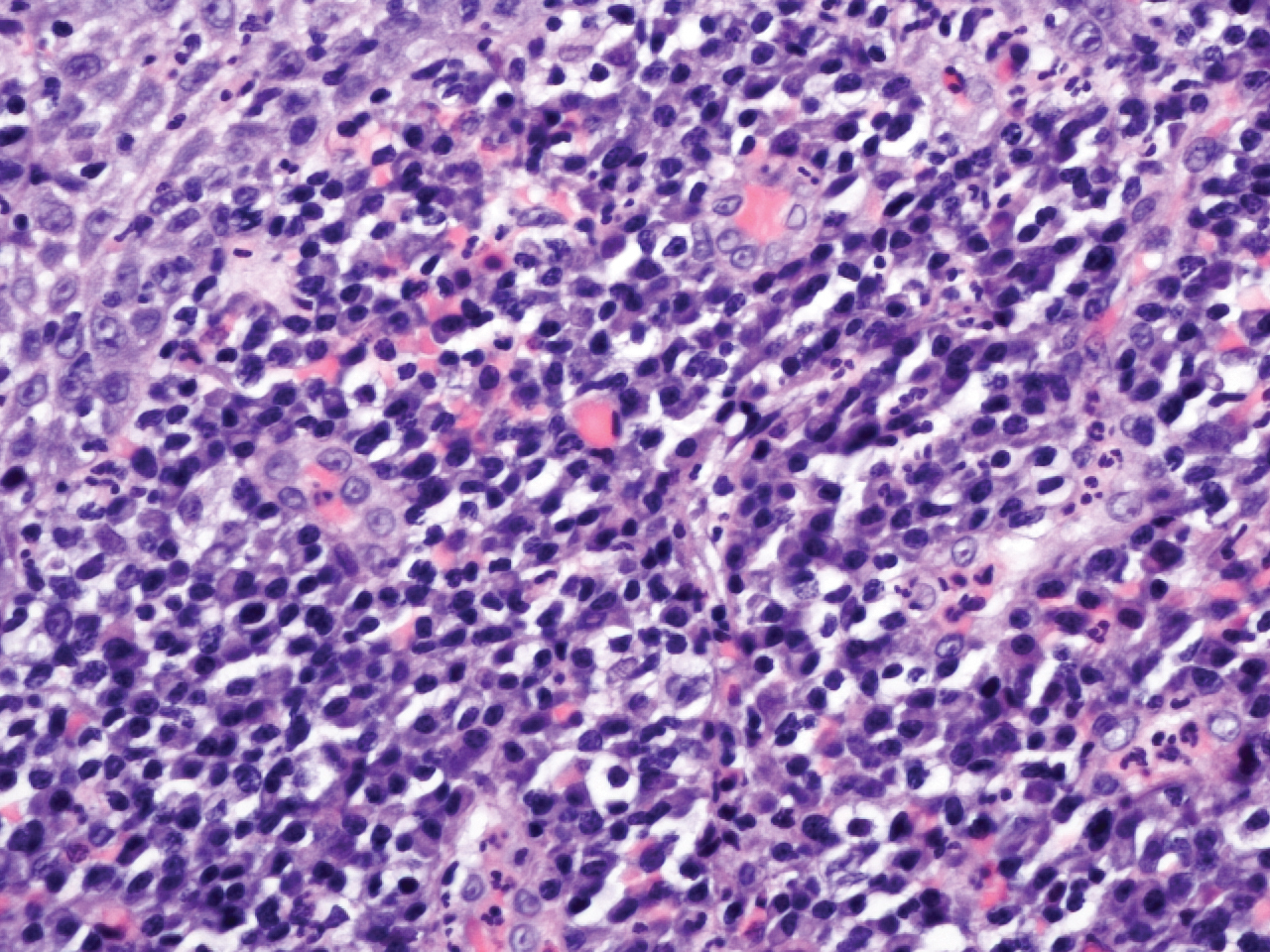

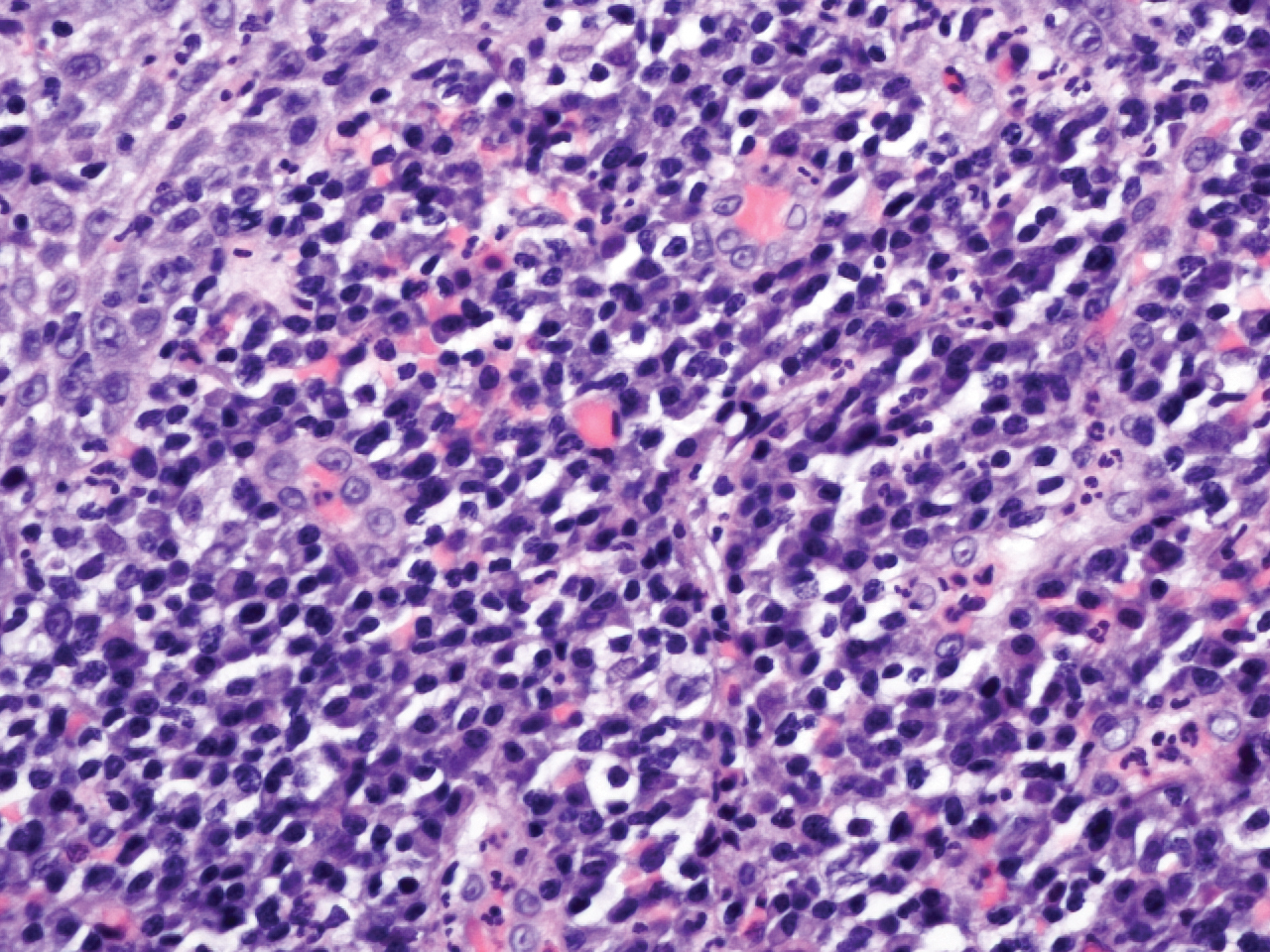

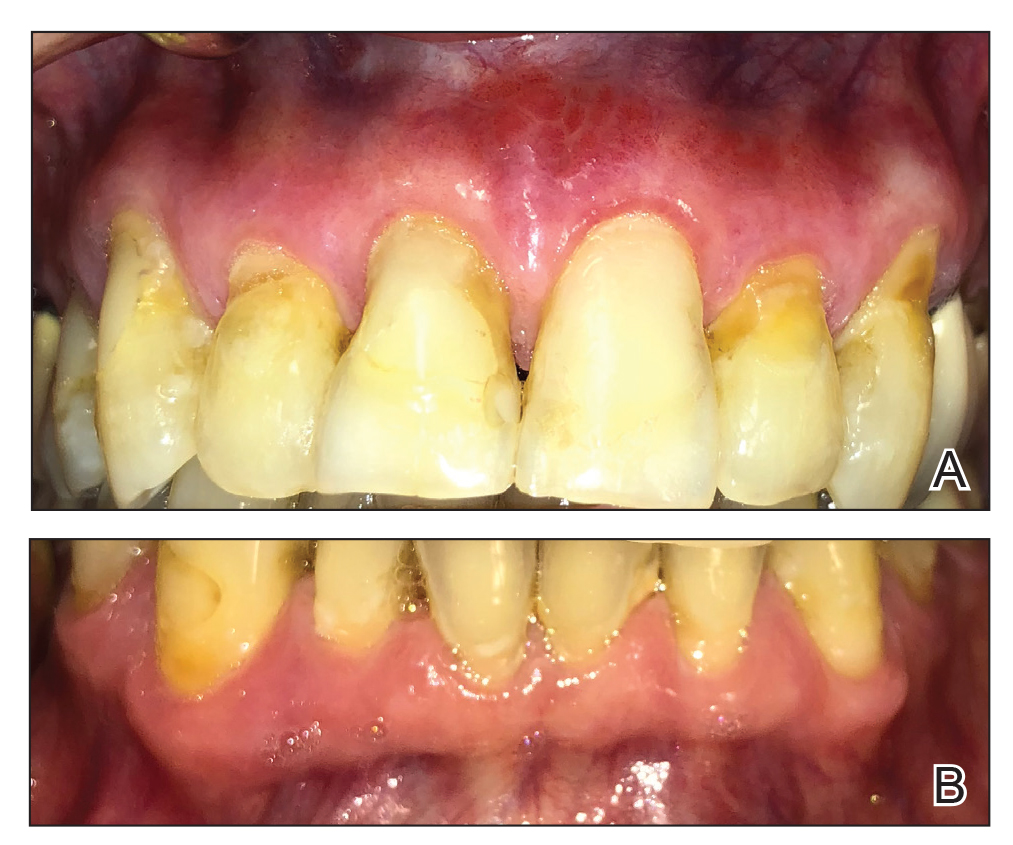

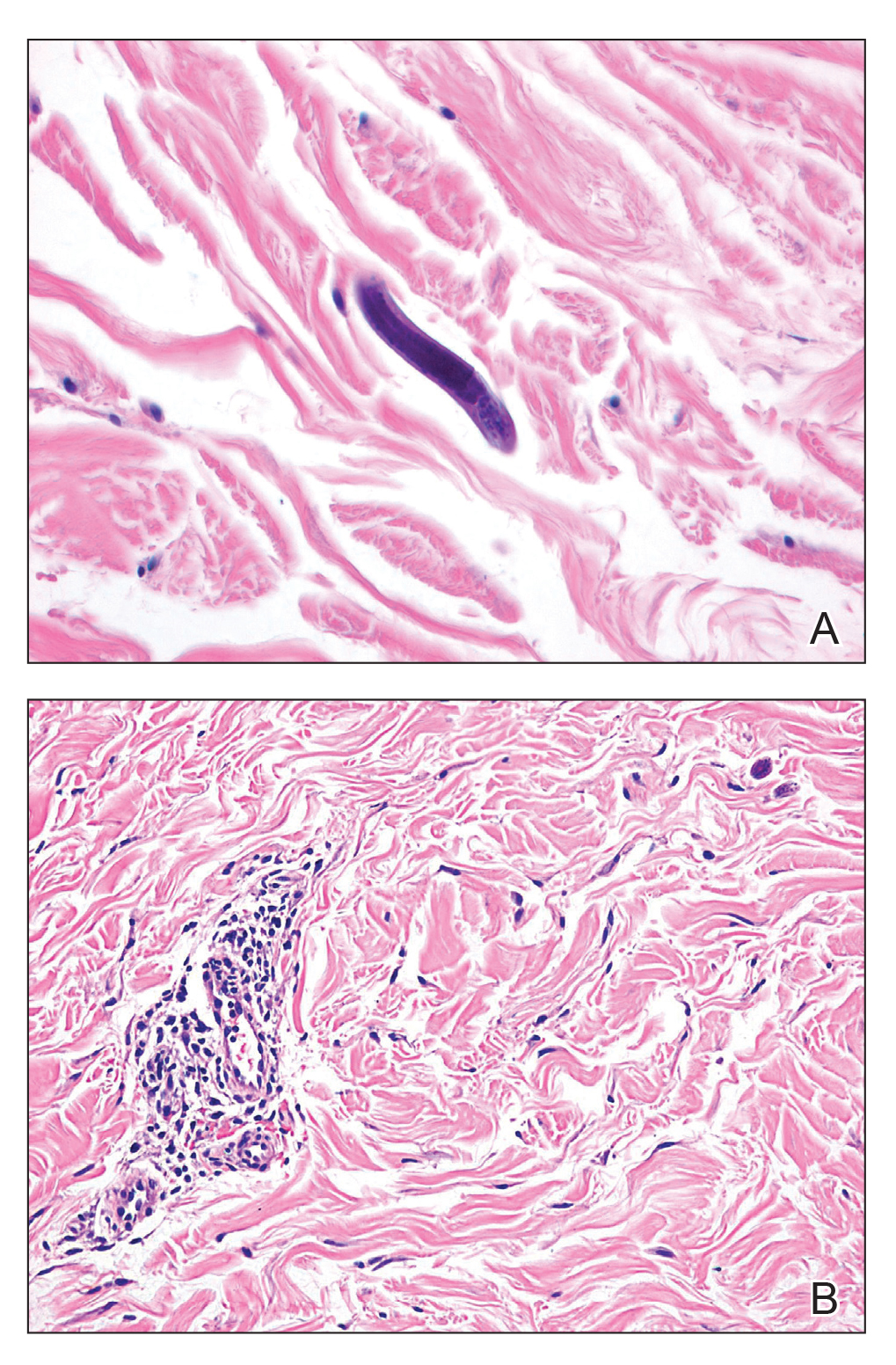

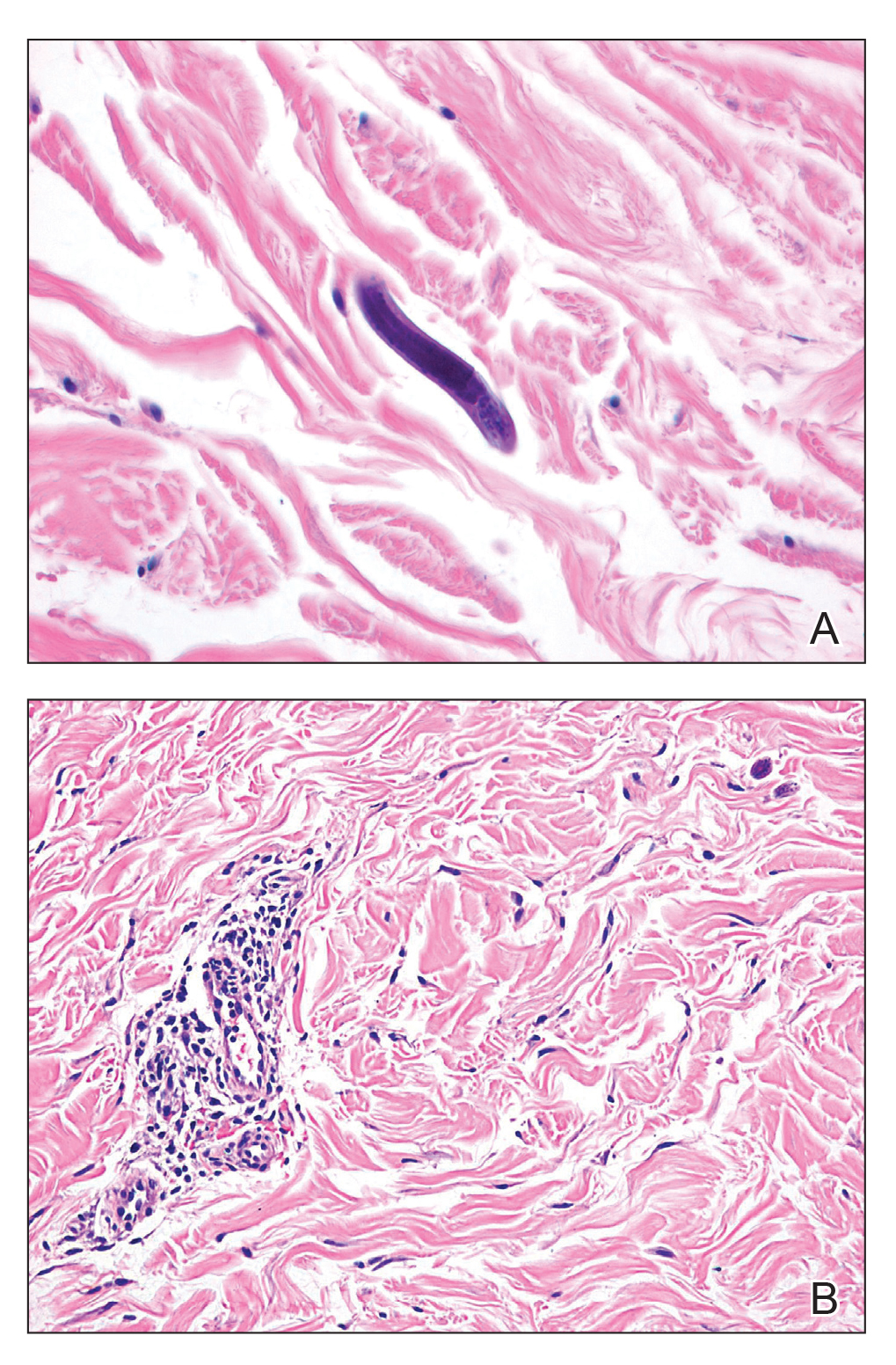

Microscopic specimen analysis demonstrated epidermal ulceration, a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate, and papillary edema (Figure) consistent with neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH). Special stains and cultures were negative for bacterial and fungal organisms. The patient was treated with high-dose oral prednisone 80 mg daily for 1 week (tapered over the course of 7 weeks) and dapsone gel 5% twice daily with rapid wound resolution. An extensive review of systems, age-appropriate malignancy screening, and laboratory evaluation did not demonstrate underlying systemic illness, infection, or malignancy.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands commonly arises alongside traumatic injury and presents as a nonhealing hand wound.1 It is considered a localized variant of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), a systemic inflammatory condition characterized by fever, malaise, neutrophilia, and elevated inflammatory markers.1,2 Cutaneous lesions are variable and may include pustular nodules; tender, purulent, violaceous plaques with ulceration and crusting; or hemorrhagic bullae resembling coagulopathy or an infectious etiology.1,3 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may present with bullous or ulcerative lesions and also histologically resembles NDDH.4 Although ulceration typically is not common in Sweet syndrome, the ulcerated lesions with elevated, edematous, and violaceous borders in our patient were characteristic of NDDH.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands, similar to Sweet syndrome, may arise along with malignancy, infection (eg, respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatitis C virus), systemic illnesses (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, Raynaud phenomenon), or environmental exposure (eg, fertilizer) or with the use of certain medications (eg, thalidomide, minocycline).1-3,5 Both solid tumors (eg, breast and lung carcinomas) as well as hematologic disturbances (eg, leukemia, myelodysplasia, lymphoma) have been associated with NDDH.1-3 Although NDDH appears to be idiopathic, all patients should undergo an extensive review of systems, laboratory evaluation, and age-appropriate malignancy screening.

Given the rarity of NDDH, necrotic lesion appearance, and potential for secondary infection, patients often are misdiagnosed with infectious etiologies, including necrotizing fasciitis.1,3,6,7 Lesions of blastomycosislike pyoderma also may be pustular or ulcerative with elevated borders resembling NDDH.8 The pathogenesis of this rare condition remains uncertain. Although systemic antibiotics are a commonly utilized treatment modality, their efficacy may be primarily related to their anti-inflammatory properties.8

Mycobacterium marinum is an aquatic nontuberculous mycobacterium that causes ulcerated, nodular, or pustular cutaneous granulomas that may resemble the lesions of NDDH.9 Similar to NDDH, lesions develop in areas of minor skin trauma, often on the upper extremities. At-risk individuals include those in frequent contact with aquatic environments, lending to the term fish tank granuloma. Diagnosis is made through culture, tissue biopsy, or the presence of acid-fast bacilli. Antibiotics such as doxycycline, surgical debridement, or cryotherapy are effective treatments.9

Unlike infectious etiologies of similarly appearing lesions, primary lesions of NDDH are aseptic. Treatment with antibiotics is ineffective, and surgical intervention can result in devastating expansion of existing wounds as well as development of new lesions at surgical margins due to the pathergy effect and Koebner phenomenon.3,6 The initiation of systemic corticosteroids and/or dapsone results in prompt resolution of NDDH.1 In recalcitrant cases or when steroids are contraindicated, other medications may be used including dapsone, colchicine, potassium iodide, indomethacin, or biologics.2

Atypical pyoderma gangrenosum is a bullous variant of pyoderma gangrenosum that is clinically and histologically indistinguishable from NDDH.2,10 Atypical pyoderma gangrenosum frequently presents on the upper extremities, exhibits a pathergy response to trauma, is associated with similar systemic diseases, and is treated identically to NDDH. There is some degree of uncertainty about the classification and pathophysiology of atypical pyoderma gangrenosum, NDDH, and Sweet syndrome. The compelling similarities may indicate that these cutaneous disorders represent a spectrum of the same disease.2,10

Consideration of NDDH in the differential of nonhealing hand wounds is paramount to prevent progression and iatrogenic morbidity associated with delayed and missed diagnosis. Early recognition of NDDH may allow for earlier diagnosis of frequently associated systemic illnesses and malignancies.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands: a report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Cheng AMY, Cheng HS, Smith BJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: a review of 17 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:185.E1-185.E5.

- Russell JP, Gibson LE. Primary cutaneous small vessel vasculitis: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:3-13.

- Kaur S, Gupta D, Garg B, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:42-45.

- Cooke-Norris RH, Youse JS, Gibson LE. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: an underrecognized hematological condition that may result in unnecessary surgery. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:60-61.

- Kroshinsky D, Alloo A, Rothschild B, et al. Necrotizing Sweet syndrome: a new variant of neutrophilic dermatosis mimicking necrotizing fasciitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:945-954.

- Hongal AA, Gejje S. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma--a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:WD03-WD04.

- Petrini B. Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:609-613.

- Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:191-211.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Microscopic specimen analysis demonstrated epidermal ulceration, a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate, and papillary edema (Figure) consistent with neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH). Special stains and cultures were negative for bacterial and fungal organisms. The patient was treated with high-dose oral prednisone 80 mg daily for 1 week (tapered over the course of 7 weeks) and dapsone gel 5% twice daily with rapid wound resolution. An extensive review of systems, age-appropriate malignancy screening, and laboratory evaluation did not demonstrate underlying systemic illness, infection, or malignancy.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands commonly arises alongside traumatic injury and presents as a nonhealing hand wound.1 It is considered a localized variant of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), a systemic inflammatory condition characterized by fever, malaise, neutrophilia, and elevated inflammatory markers.1,2 Cutaneous lesions are variable and may include pustular nodules; tender, purulent, violaceous plaques with ulceration and crusting; or hemorrhagic bullae resembling coagulopathy or an infectious etiology.1,3 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may present with bullous or ulcerative lesions and also histologically resembles NDDH.4 Although ulceration typically is not common in Sweet syndrome, the ulcerated lesions with elevated, edematous, and violaceous borders in our patient were characteristic of NDDH.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands, similar to Sweet syndrome, may arise along with malignancy, infection (eg, respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatitis C virus), systemic illnesses (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, Raynaud phenomenon), or environmental exposure (eg, fertilizer) or with the use of certain medications (eg, thalidomide, minocycline).1-3,5 Both solid tumors (eg, breast and lung carcinomas) as well as hematologic disturbances (eg, leukemia, myelodysplasia, lymphoma) have been associated with NDDH.1-3 Although NDDH appears to be idiopathic, all patients should undergo an extensive review of systems, laboratory evaluation, and age-appropriate malignancy screening.

Given the rarity of NDDH, necrotic lesion appearance, and potential for secondary infection, patients often are misdiagnosed with infectious etiologies, including necrotizing fasciitis.1,3,6,7 Lesions of blastomycosislike pyoderma also may be pustular or ulcerative with elevated borders resembling NDDH.8 The pathogenesis of this rare condition remains uncertain. Although systemic antibiotics are a commonly utilized treatment modality, their efficacy may be primarily related to their anti-inflammatory properties.8

Mycobacterium marinum is an aquatic nontuberculous mycobacterium that causes ulcerated, nodular, or pustular cutaneous granulomas that may resemble the lesions of NDDH.9 Similar to NDDH, lesions develop in areas of minor skin trauma, often on the upper extremities. At-risk individuals include those in frequent contact with aquatic environments, lending to the term fish tank granuloma. Diagnosis is made through culture, tissue biopsy, or the presence of acid-fast bacilli. Antibiotics such as doxycycline, surgical debridement, or cryotherapy are effective treatments.9

Unlike infectious etiologies of similarly appearing lesions, primary lesions of NDDH are aseptic. Treatment with antibiotics is ineffective, and surgical intervention can result in devastating expansion of existing wounds as well as development of new lesions at surgical margins due to the pathergy effect and Koebner phenomenon.3,6 The initiation of systemic corticosteroids and/or dapsone results in prompt resolution of NDDH.1 In recalcitrant cases or when steroids are contraindicated, other medications may be used including dapsone, colchicine, potassium iodide, indomethacin, or biologics.2

Atypical pyoderma gangrenosum is a bullous variant of pyoderma gangrenosum that is clinically and histologically indistinguishable from NDDH.2,10 Atypical pyoderma gangrenosum frequently presents on the upper extremities, exhibits a pathergy response to trauma, is associated with similar systemic diseases, and is treated identically to NDDH. There is some degree of uncertainty about the classification and pathophysiology of atypical pyoderma gangrenosum, NDDH, and Sweet syndrome. The compelling similarities may indicate that these cutaneous disorders represent a spectrum of the same disease.2,10

Consideration of NDDH in the differential of nonhealing hand wounds is paramount to prevent progression and iatrogenic morbidity associated with delayed and missed diagnosis. Early recognition of NDDH may allow for earlier diagnosis of frequently associated systemic illnesses and malignancies.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Microscopic specimen analysis demonstrated epidermal ulceration, a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate, and papillary edema (Figure) consistent with neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH). Special stains and cultures were negative for bacterial and fungal organisms. The patient was treated with high-dose oral prednisone 80 mg daily for 1 week (tapered over the course of 7 weeks) and dapsone gel 5% twice daily with rapid wound resolution. An extensive review of systems, age-appropriate malignancy screening, and laboratory evaluation did not demonstrate underlying systemic illness, infection, or malignancy.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands commonly arises alongside traumatic injury and presents as a nonhealing hand wound.1 It is considered a localized variant of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), a systemic inflammatory condition characterized by fever, malaise, neutrophilia, and elevated inflammatory markers.1,2 Cutaneous lesions are variable and may include pustular nodules; tender, purulent, violaceous plaques with ulceration and crusting; or hemorrhagic bullae resembling coagulopathy or an infectious etiology.1,3 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may present with bullous or ulcerative lesions and also histologically resembles NDDH.4 Although ulceration typically is not common in Sweet syndrome, the ulcerated lesions with elevated, edematous, and violaceous borders in our patient were characteristic of NDDH.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands, similar to Sweet syndrome, may arise along with malignancy, infection (eg, respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatitis C virus), systemic illnesses (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, Raynaud phenomenon), or environmental exposure (eg, fertilizer) or with the use of certain medications (eg, thalidomide, minocycline).1-3,5 Both solid tumors (eg, breast and lung carcinomas) as well as hematologic disturbances (eg, leukemia, myelodysplasia, lymphoma) have been associated with NDDH.1-3 Although NDDH appears to be idiopathic, all patients should undergo an extensive review of systems, laboratory evaluation, and age-appropriate malignancy screening.

Given the rarity of NDDH, necrotic lesion appearance, and potential for secondary infection, patients often are misdiagnosed with infectious etiologies, including necrotizing fasciitis.1,3,6,7 Lesions of blastomycosislike pyoderma also may be pustular or ulcerative with elevated borders resembling NDDH.8 The pathogenesis of this rare condition remains uncertain. Although systemic antibiotics are a commonly utilized treatment modality, their efficacy may be primarily related to their anti-inflammatory properties.8

Mycobacterium marinum is an aquatic nontuberculous mycobacterium that causes ulcerated, nodular, or pustular cutaneous granulomas that may resemble the lesions of NDDH.9 Similar to NDDH, lesions develop in areas of minor skin trauma, often on the upper extremities. At-risk individuals include those in frequent contact with aquatic environments, lending to the term fish tank granuloma. Diagnosis is made through culture, tissue biopsy, or the presence of acid-fast bacilli. Antibiotics such as doxycycline, surgical debridement, or cryotherapy are effective treatments.9

Unlike infectious etiologies of similarly appearing lesions, primary lesions of NDDH are aseptic. Treatment with antibiotics is ineffective, and surgical intervention can result in devastating expansion of existing wounds as well as development of new lesions at surgical margins due to the pathergy effect and Koebner phenomenon.3,6 The initiation of systemic corticosteroids and/or dapsone results in prompt resolution of NDDH.1 In recalcitrant cases or when steroids are contraindicated, other medications may be used including dapsone, colchicine, potassium iodide, indomethacin, or biologics.2

Atypical pyoderma gangrenosum is a bullous variant of pyoderma gangrenosum that is clinically and histologically indistinguishable from NDDH.2,10 Atypical pyoderma gangrenosum frequently presents on the upper extremities, exhibits a pathergy response to trauma, is associated with similar systemic diseases, and is treated identically to NDDH. There is some degree of uncertainty about the classification and pathophysiology of atypical pyoderma gangrenosum, NDDH, and Sweet syndrome. The compelling similarities may indicate that these cutaneous disorders represent a spectrum of the same disease.2,10

Consideration of NDDH in the differential of nonhealing hand wounds is paramount to prevent progression and iatrogenic morbidity associated with delayed and missed diagnosis. Early recognition of NDDH may allow for earlier diagnosis of frequently associated systemic illnesses and malignancies.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands: a report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Cheng AMY, Cheng HS, Smith BJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: a review of 17 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:185.E1-185.E5.

- Russell JP, Gibson LE. Primary cutaneous small vessel vasculitis: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:3-13.

- Kaur S, Gupta D, Garg B, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:42-45.

- Cooke-Norris RH, Youse JS, Gibson LE. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: an underrecognized hematological condition that may result in unnecessary surgery. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:60-61.

- Kroshinsky D, Alloo A, Rothschild B, et al. Necrotizing Sweet syndrome: a new variant of neutrophilic dermatosis mimicking necrotizing fasciitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:945-954.

- Hongal AA, Gejje S. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma--a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:WD03-WD04.

- Petrini B. Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:609-613.

- Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:191-211.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands: a report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Cheng AMY, Cheng HS, Smith BJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: a review of 17 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:185.E1-185.E5.

- Russell JP, Gibson LE. Primary cutaneous small vessel vasculitis: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:3-13.

- Kaur S, Gupta D, Garg B, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:42-45.

- Cooke-Norris RH, Youse JS, Gibson LE. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: an underrecognized hematological condition that may result in unnecessary surgery. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:60-61.

- Kroshinsky D, Alloo A, Rothschild B, et al. Necrotizing Sweet syndrome: a new variant of neutrophilic dermatosis mimicking necrotizing fasciitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:945-954.

- Hongal AA, Gejje S. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma--a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:WD03-WD04.

- Petrini B. Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:609-613.

- Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:191-211.

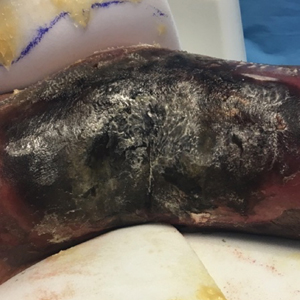

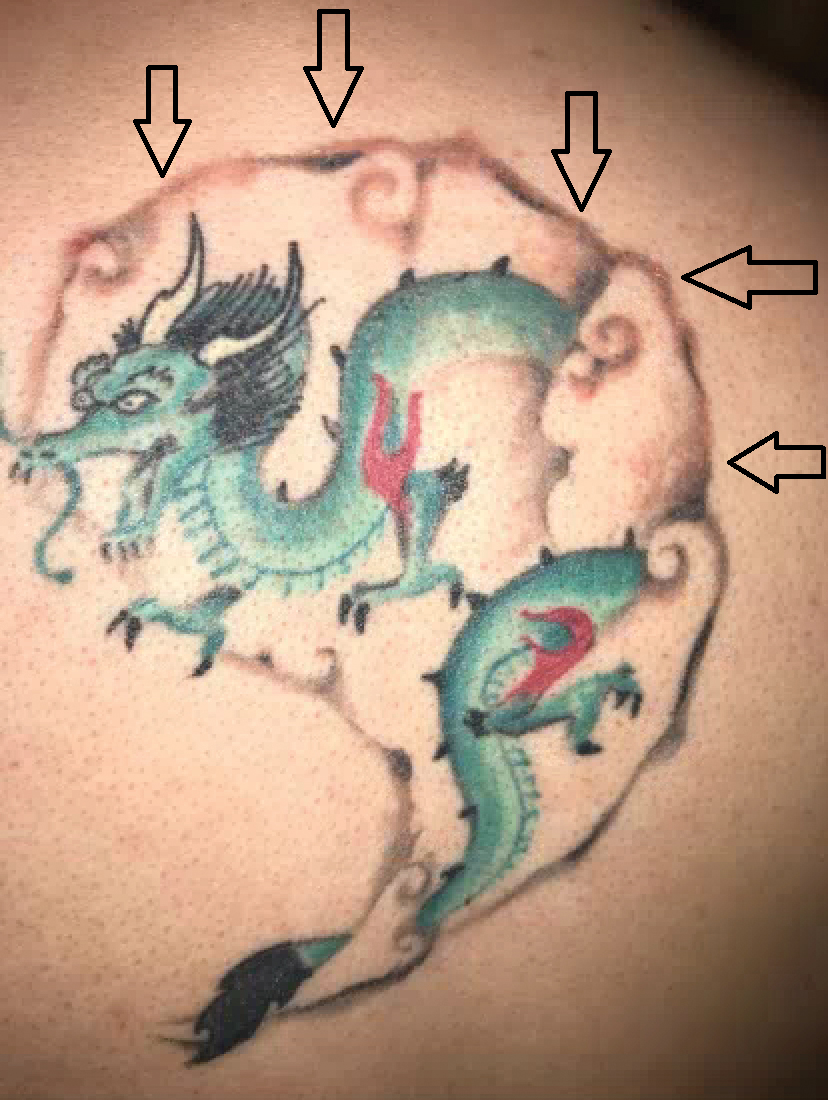

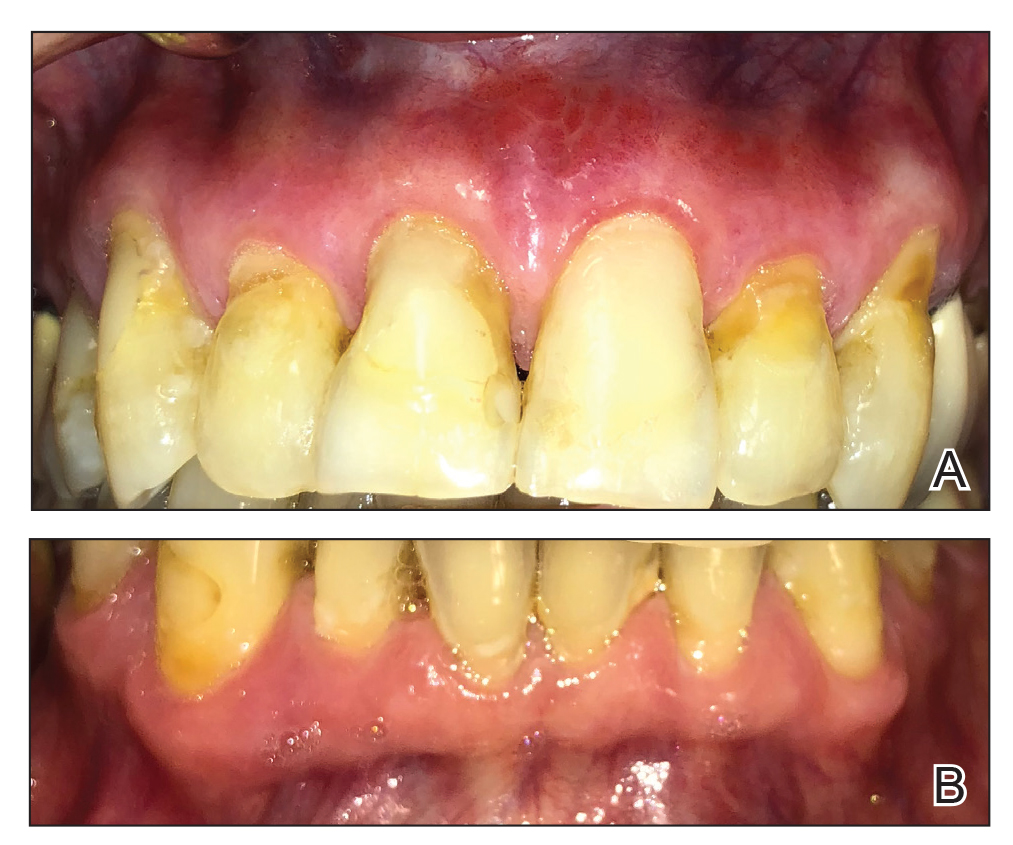

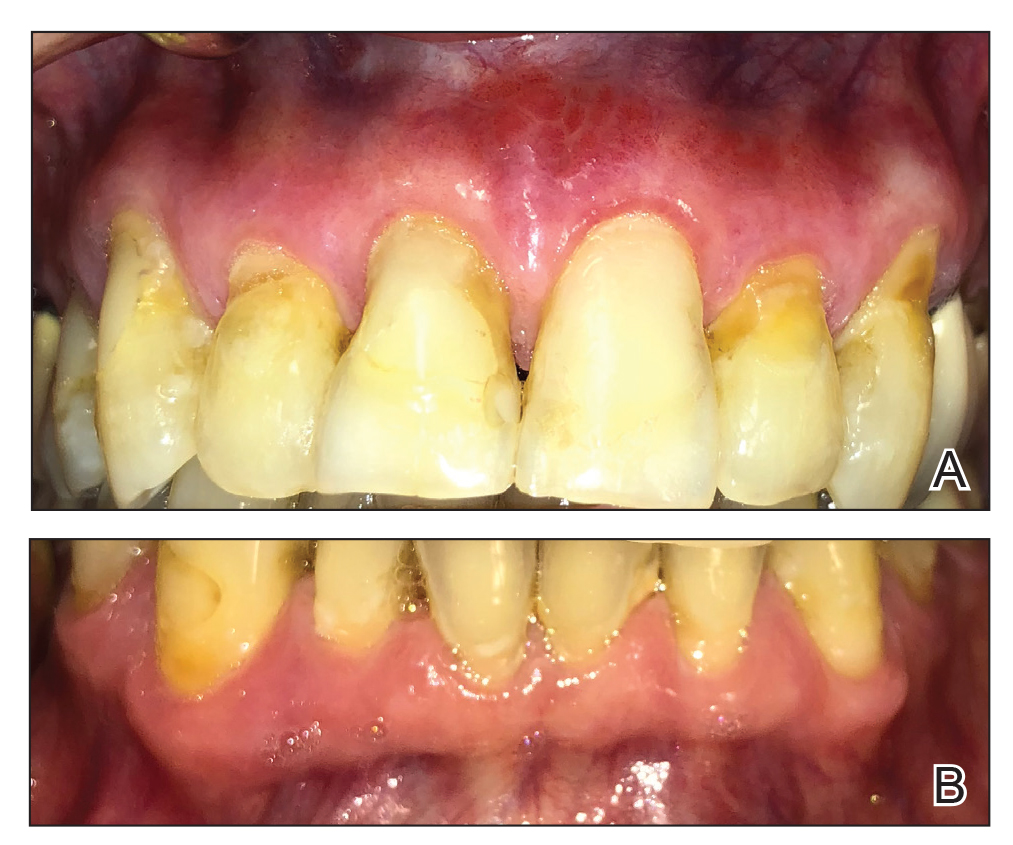

A 63-year-old man presented with an expanding wound on the dorsal aspect of the left hand after striking it on a wall. He sustained a small laceration that progressively became more edematous and developed a violaceous border. He presented to the emergency department the following day and was prescribed bacitracin with no improvement in the lesion. He returned to the emergency department after the symptoms worsened and was subsequently prescribed a 10-day course of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1600/320 mg) twice daily. Physical examination at a follow-up visit 11 days after the initial injury revealed an expanding, 4.3×5.0-cm, ulcerated wound with surrounding erythema and serosanguineous drainage (left). He was started on a 10-day course of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (1750/250 mg) twice daily and underwent debridement the same day. On postoperative day 2 (13 days following the onset of symptoms), the wound had not improved, and 2 new 1-cm bullae on the left first and second fingers had progressed (right). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (33 mm/h [reference range, 0–10 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein (3.701 mg/dL [reference range, 0–0.747 mg/dL]) were elevated; however, other laboratory studies, including a complete blood cell count, were within reference range. He remained afebrile, and a review of systems was normal. Punch biopsy specimens were obtained.

Extensive Purpura and Necrosis of the Leg

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Mucormycosis

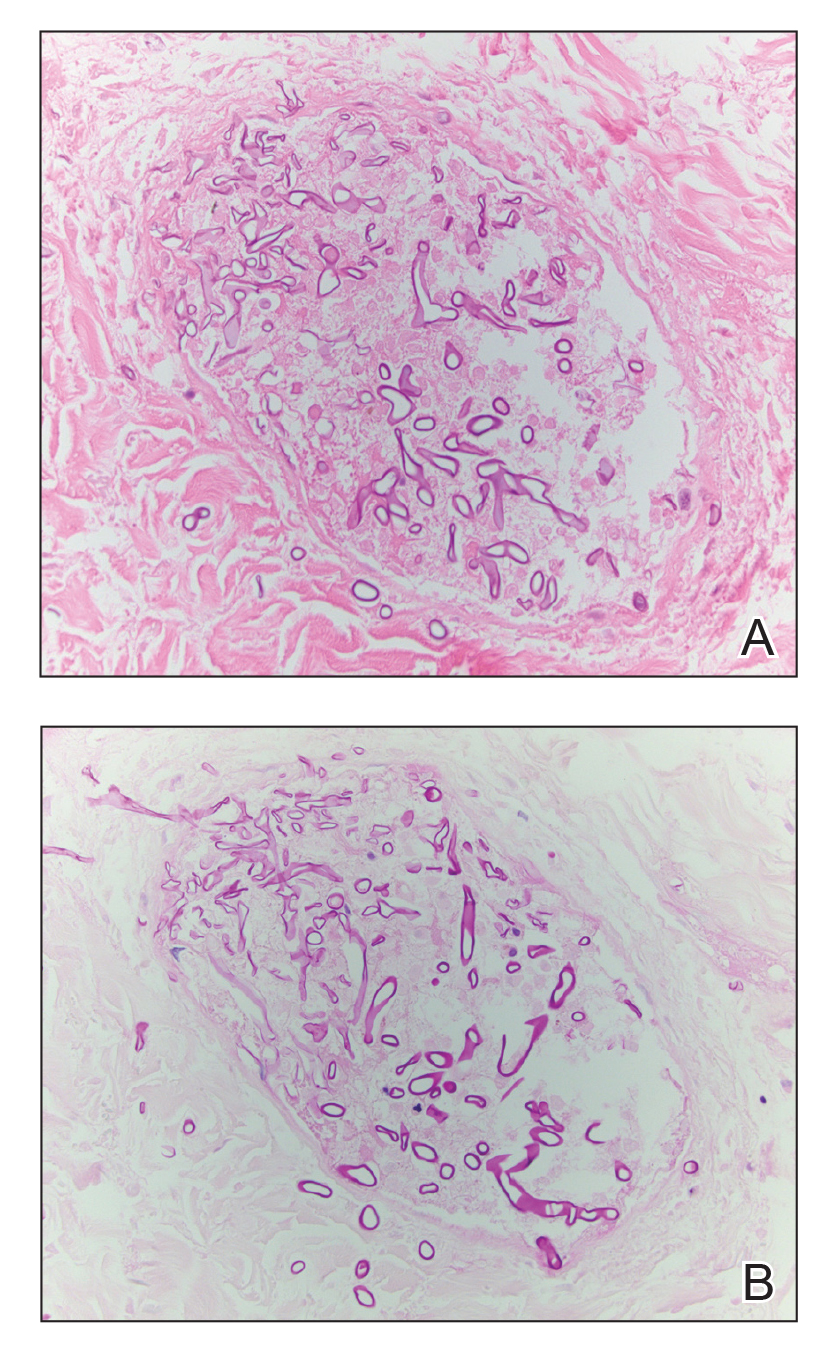

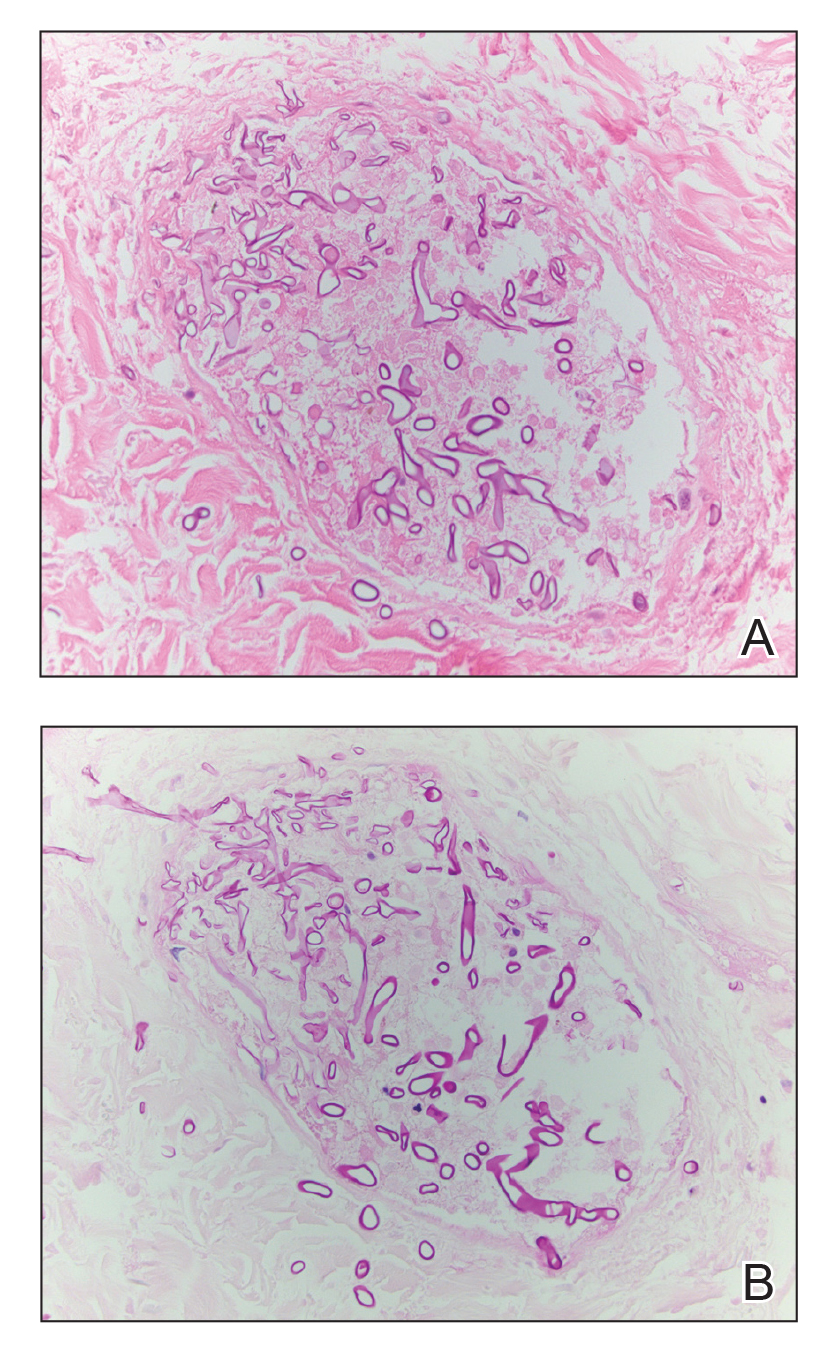

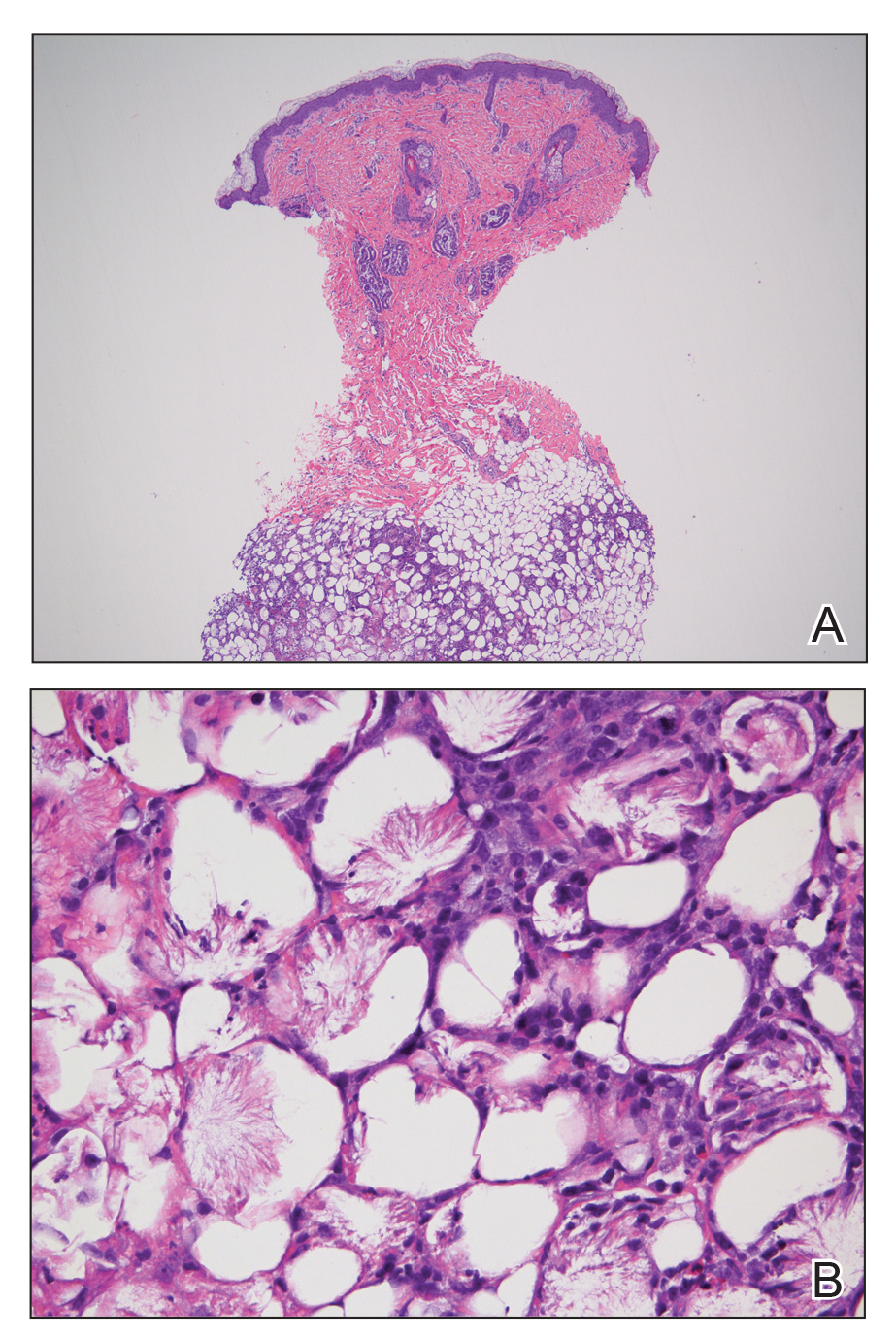

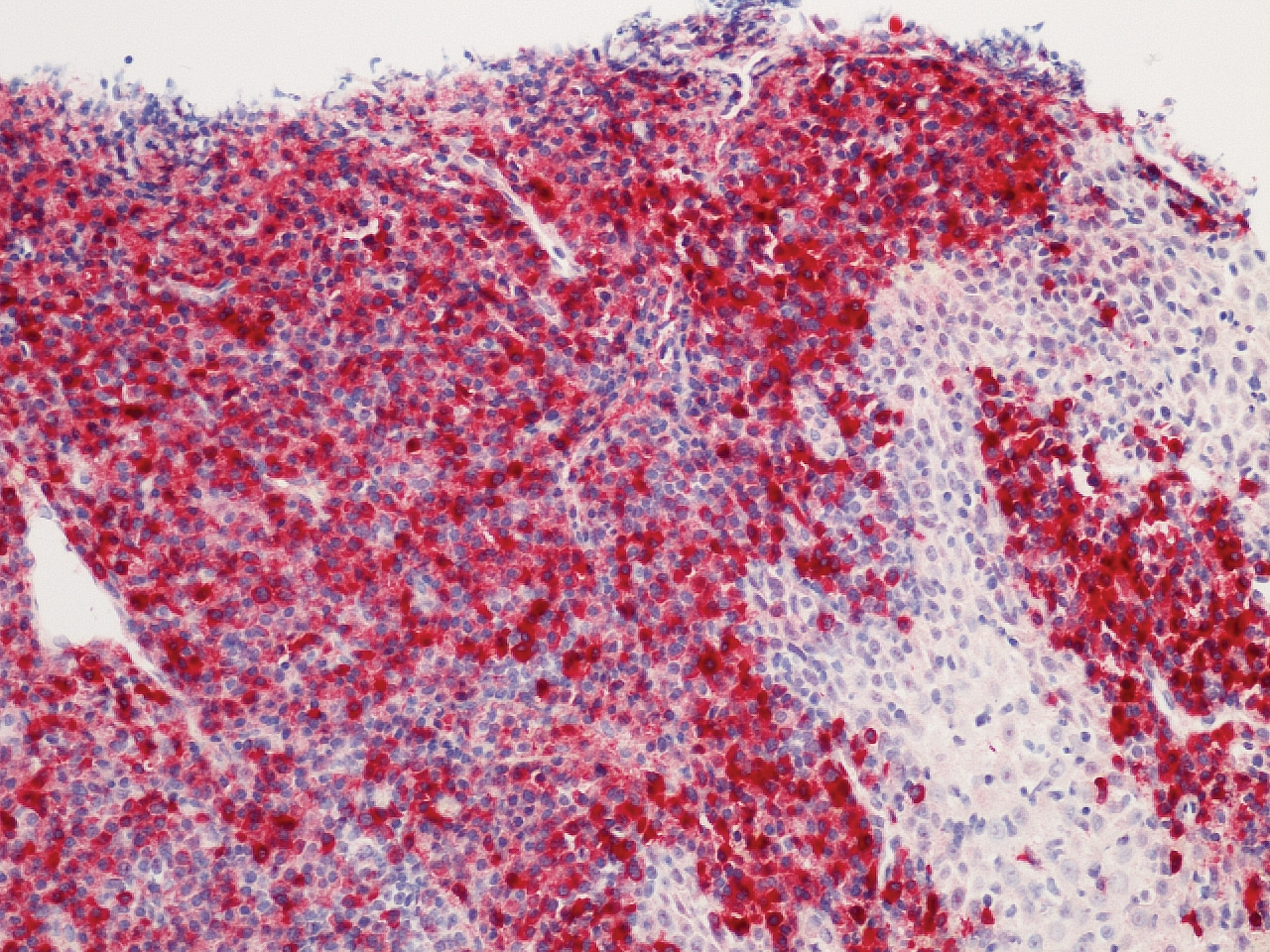

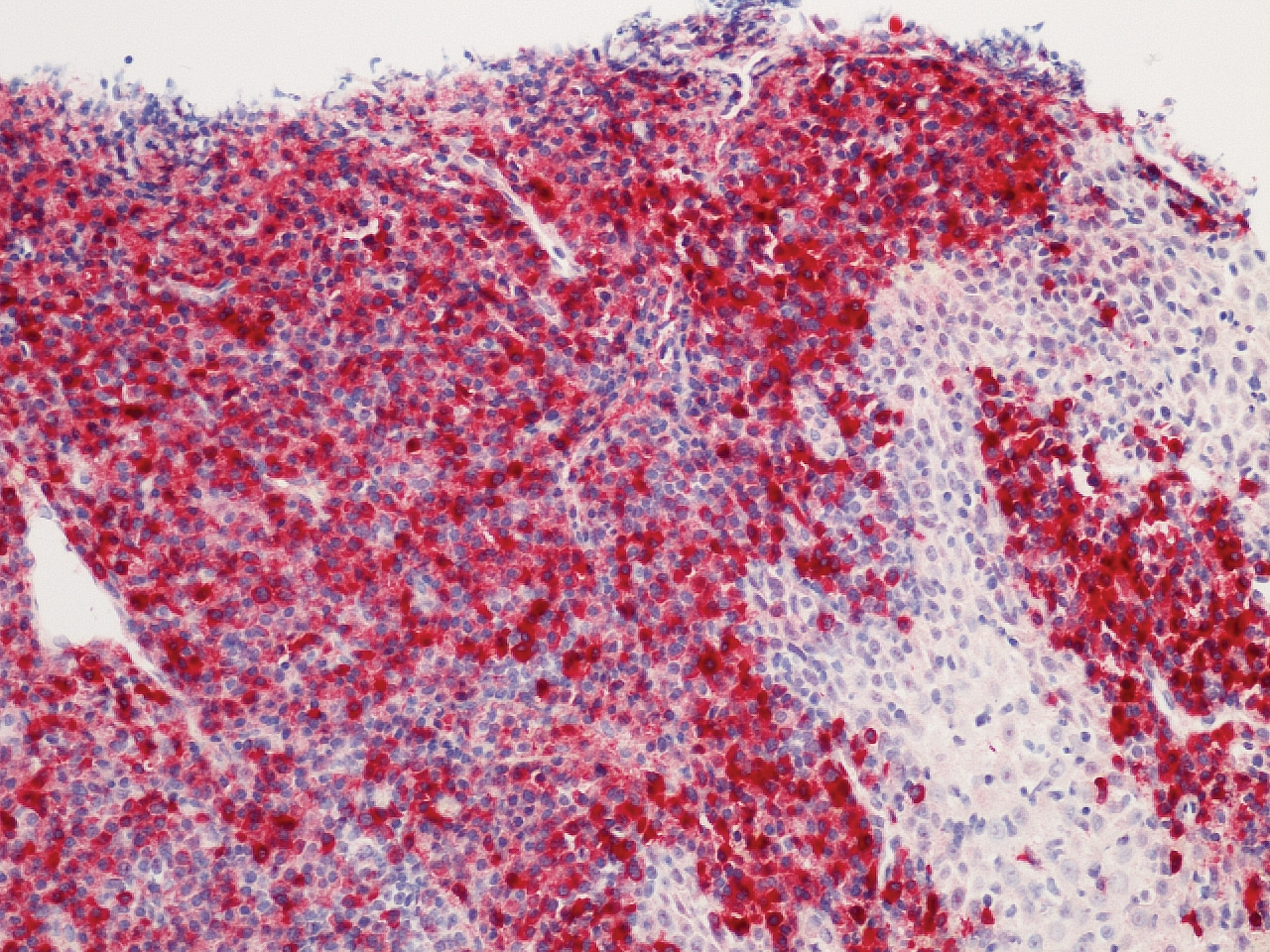

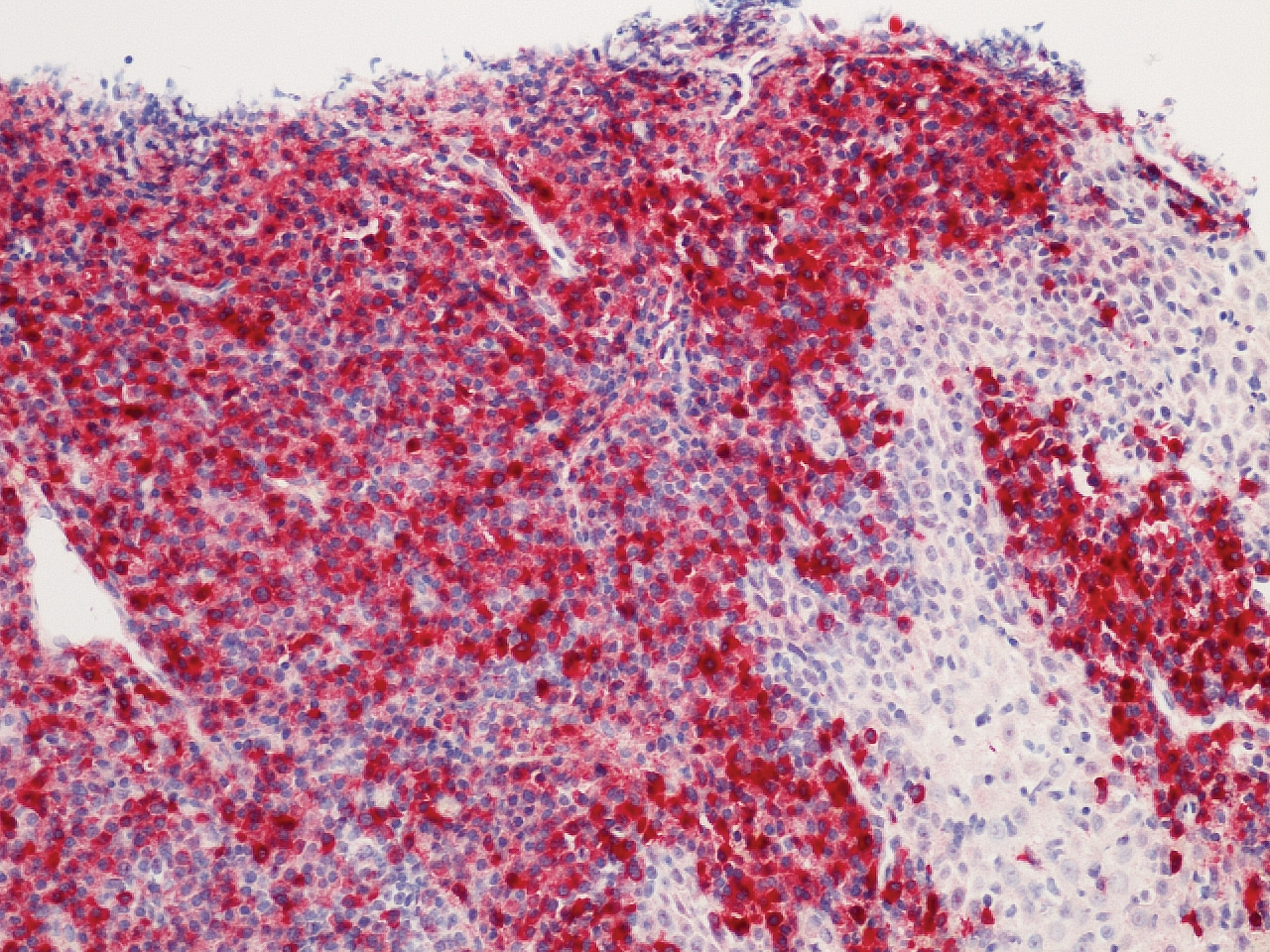

Histopathologic examination of a 6-mm punch biopsy of the edge of the lesion revealed numerous intravascular, broad, nonseptate hyphae in the deep vessels and perivascular dermis that stained bright red with periodic acid-Schiff (Figure). Acid-fast bacilli and Gram stains were negative. Tissue culture grew Rhizopus species. Given the patient's overall poor prognosis, her family decided to pursue hospice care following this diagnosis.

Mucormycosis (formerly zygomycosis) refers to infections from a variety of genera of fungi, most commonly Mucor and Rhizopus, that cause infections primarily in immunocompromised individuals.1 Mucormycosis infections are characterized by tissue necrosis that results from invasion of the vasculature and subsequent thrombosis. The typical presentation of cutaneous mucormycosis is a necrotic eschar accompanied by surrounding erythema and induration.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, requiring additional testing with skin biopsy and tissue cultures for confirmation.

Cutaneous infection is the third most common presentation of mucormycosis, following rhinocerebral and pulmonary involvement.1 Although rhinocerebral and pulmonary infections normally are caused by inhalation of spores, cutaneous mucormycosis typically is caused by local inoculation, often following skin trauma.2 The skin is the most common location of iatrogenic mucormycosis, often from skin injury related to surgery, catheters, and adhesive tape.3 Most patients with cutaneous mucormycosis have underlying conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, or immunosuppression.1 However, outbreaks have occurred in immunocompetent patients following natural disasters.4 Cutaneous mucormycosis disseminates in 13% to 20% of cases in which mortality rates typically exceed 90%.1

Treatment consists of prompt surgical debridement and antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazonium sulfate.1 Our patient had multiple risk factors for infection, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, prolonged neutropenia, and treatment with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C5 that blocks the terminal complement cascade. Eculizumab has been associated with increased risk for meningococcemia,5 but the association with mucormycosis is rare. We highlight the importance of recognizing and promptly diagnosing cutaneous mucormycosis given the difficulty of treating this disease and its poor prognosis.

Disseminated aspergillosis demonstrates septate rather than nonseptate hyphae on biopsy. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and purpura fulminans may be associated with thrombocytopenia but demonstrate thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate on biopsy.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Zahar JR, et al. Healthcare-associated mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S44-S54.

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, et al. Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2214-2225.

- McNamara LA, Topaz N, Wang X, et al. High risk for invasive meningococcal disease among patients receiving eculizumab (Soliris) despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:734-737.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Mucormycosis

Histopathologic examination of a 6-mm punch biopsy of the edge of the lesion revealed numerous intravascular, broad, nonseptate hyphae in the deep vessels and perivascular dermis that stained bright red with periodic acid-Schiff (Figure). Acid-fast bacilli and Gram stains were negative. Tissue culture grew Rhizopus species. Given the patient's overall poor prognosis, her family decided to pursue hospice care following this diagnosis.

Mucormycosis (formerly zygomycosis) refers to infections from a variety of genera of fungi, most commonly Mucor and Rhizopus, that cause infections primarily in immunocompromised individuals.1 Mucormycosis infections are characterized by tissue necrosis that results from invasion of the vasculature and subsequent thrombosis. The typical presentation of cutaneous mucormycosis is a necrotic eschar accompanied by surrounding erythema and induration.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, requiring additional testing with skin biopsy and tissue cultures for confirmation.

Cutaneous infection is the third most common presentation of mucormycosis, following rhinocerebral and pulmonary involvement.1 Although rhinocerebral and pulmonary infections normally are caused by inhalation of spores, cutaneous mucormycosis typically is caused by local inoculation, often following skin trauma.2 The skin is the most common location of iatrogenic mucormycosis, often from skin injury related to surgery, catheters, and adhesive tape.3 Most patients with cutaneous mucormycosis have underlying conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, or immunosuppression.1 However, outbreaks have occurred in immunocompetent patients following natural disasters.4 Cutaneous mucormycosis disseminates in 13% to 20% of cases in which mortality rates typically exceed 90%.1

Treatment consists of prompt surgical debridement and antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazonium sulfate.1 Our patient had multiple risk factors for infection, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, prolonged neutropenia, and treatment with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C5 that blocks the terminal complement cascade. Eculizumab has been associated with increased risk for meningococcemia,5 but the association with mucormycosis is rare. We highlight the importance of recognizing and promptly diagnosing cutaneous mucormycosis given the difficulty of treating this disease and its poor prognosis.

Disseminated aspergillosis demonstrates septate rather than nonseptate hyphae on biopsy. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and purpura fulminans may be associated with thrombocytopenia but demonstrate thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate on biopsy.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Mucormycosis

Histopathologic examination of a 6-mm punch biopsy of the edge of the lesion revealed numerous intravascular, broad, nonseptate hyphae in the deep vessels and perivascular dermis that stained bright red with periodic acid-Schiff (Figure). Acid-fast bacilli and Gram stains were negative. Tissue culture grew Rhizopus species. Given the patient's overall poor prognosis, her family decided to pursue hospice care following this diagnosis.

Mucormycosis (formerly zygomycosis) refers to infections from a variety of genera of fungi, most commonly Mucor and Rhizopus, that cause infections primarily in immunocompromised individuals.1 Mucormycosis infections are characterized by tissue necrosis that results from invasion of the vasculature and subsequent thrombosis. The typical presentation of cutaneous mucormycosis is a necrotic eschar accompanied by surrounding erythema and induration.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, requiring additional testing with skin biopsy and tissue cultures for confirmation.

Cutaneous infection is the third most common presentation of mucormycosis, following rhinocerebral and pulmonary involvement.1 Although rhinocerebral and pulmonary infections normally are caused by inhalation of spores, cutaneous mucormycosis typically is caused by local inoculation, often following skin trauma.2 The skin is the most common location of iatrogenic mucormycosis, often from skin injury related to surgery, catheters, and adhesive tape.3 Most patients with cutaneous mucormycosis have underlying conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, or immunosuppression.1 However, outbreaks have occurred in immunocompetent patients following natural disasters.4 Cutaneous mucormycosis disseminates in 13% to 20% of cases in which mortality rates typically exceed 90%.1

Treatment consists of prompt surgical debridement and antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazonium sulfate.1 Our patient had multiple risk factors for infection, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, prolonged neutropenia, and treatment with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C5 that blocks the terminal complement cascade. Eculizumab has been associated with increased risk for meningococcemia,5 but the association with mucormycosis is rare. We highlight the importance of recognizing and promptly diagnosing cutaneous mucormycosis given the difficulty of treating this disease and its poor prognosis.

Disseminated aspergillosis demonstrates septate rather than nonseptate hyphae on biopsy. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and purpura fulminans may be associated with thrombocytopenia but demonstrate thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate on biopsy.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Zahar JR, et al. Healthcare-associated mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S44-S54.

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, et al. Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2214-2225.

- McNamara LA, Topaz N, Wang X, et al. High risk for invasive meningococcal disease among patients receiving eculizumab (Soliris) despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:734-737.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Zahar JR, et al. Healthcare-associated mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S44-S54.

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, et al. Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2214-2225.

- McNamara LA, Topaz N, Wang X, et al. High risk for invasive meningococcal disease among patients receiving eculizumab (Soliris) despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:734-737.

A 57-year-old woman presented with expanding purpura on the left leg of 2 weeks’ duration following a recent hematopoietic stem cell transplant for refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Prior to dermatologic consultation, the patient had been hospitalized for 2 months following the transplant due to Clostridium difficile colitis, Enterococcus faecium bacteremia, cardiac arrest, delayed engraftment with pancytopenia, and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with acute renal failure requiring hemodialysis and treatment with eculizumab. Her care team in the hospital initially noticed a small purpuric lesion on the posterior aspect of the left knee. The patient subsequently developed persistent fevers and expansion of the lesion, which prompted consultation of the dermatology service. Physical examination revealed a 22×10-cm, rectangular, indurated, purpuric plaque with central dusky, violaceous to black necrosis with superficial skin sloughing and peripheral dusky erythema extending from the inner thigh to the lower leg. The left distal leg felt cool, and both dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were absent. Laboratory test results revealed neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.2×103 /mm3 [reference range, 5–10×103 /mm3 ]; hematocrit, 23.2% [reference range, 41%–50%]; platelet count, 105×103 /µL [reference range, 150–350×103 /µL]). A punch biopsy was performed.

Painful Hemorrhagic Erosions

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption (Eczema Herpeticum)

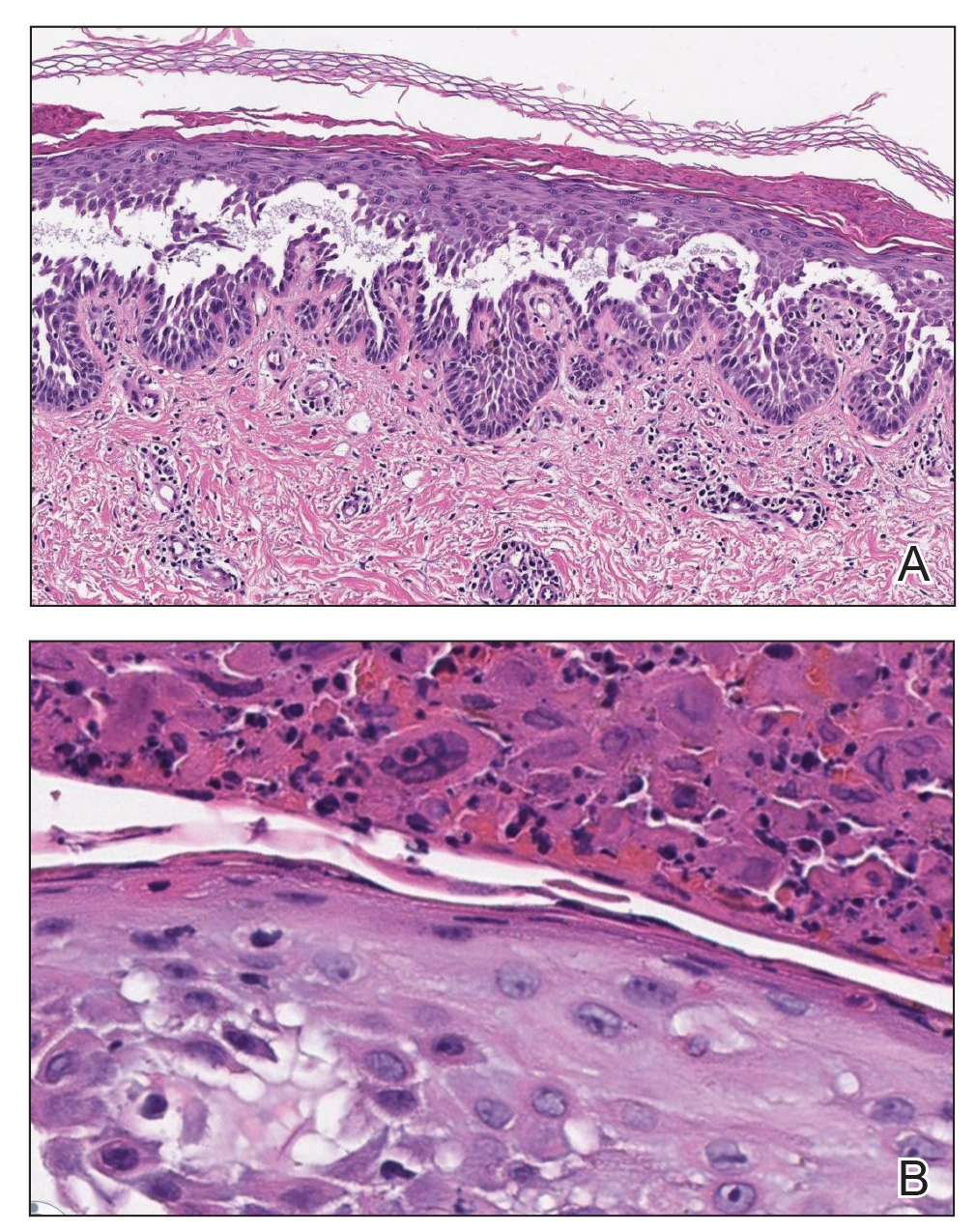

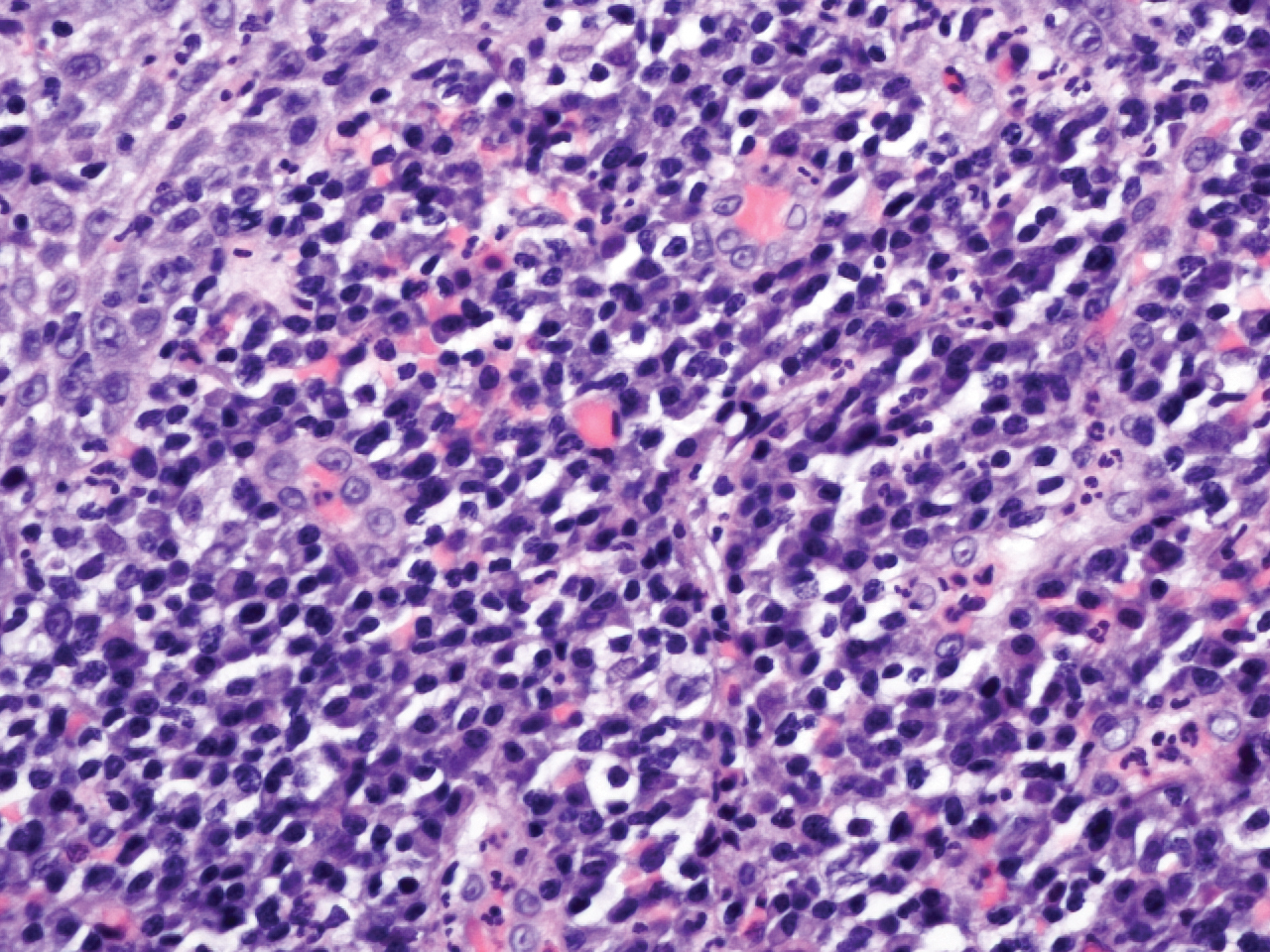

Polymerase chain reaction confirmed presence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, and the patient was started on intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours). Diagnosis was further supported by histopathologic examination with confirmatory immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). The patient's anemia and thrombocytopenia also were attributed to widespread HSV infection.

Approximately 8 hours after the patient was started on acyclovir, he developed increasing tremors, confusion, and impaired speech. Lumbar puncture confirmed the presence of HSV-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid. Despite ongoing intravenous antiviral therapy, he required intubation 6 days after hospitalization due to impaired mental status and myoclonic jerking. He remained intubated, unresponsive, and in critical condition for 9 days before he gradually began to demonstrate cognitive recovery. He subsequently was weaned off the ventilator, his mental status returned to normal, and his skin rash slowly resolved (Figure 2).

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus, is a rare autosomal-dominant condition first described by Howard and Hugh Hailey in 1939.1 It is a chronic blistering process characterized by epidermal fragility, often manifesting as macerated fissured erosions in areas exposed to heat and friction (eg, axillae, groin). Hailey-Hailey disease results from a defective calcium transporter (ATP2C1 gene), leading to impaired keratinocyte adhesion.2

Eczema herpeticum refers to the dissemination of herpes infection to areas of compromised skin barrier. Although originally used to describe HSV infection in patients with atopic dermatitis, eczema herpeticum has been described in various conditions that affect the skin barrier function, including Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mycosis fungoides, among others.3 When applied to skin conditions other than atopic dermatitis, it sometimes is referred to as Kaposi varicelliform eruption.2

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly is complicated by a bacterial or fungal infection, including impetigo, tinea, or candidiasis. The first case of HHD complicated by HSV infection was reported in 1973.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms benign familial pemphigus AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND eczema herpeticum, Hailey-Hailey AND Kaposi varicelliform eruption, and Hailey-Hailey herpeticum revealed 15 cases of HHD complicated by eczema herpeticum.4-6 Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a rare and life-threatening complication of eczema herpeticum.7,8 We report a case of HSV encephalitis resulting from eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD.

The clinical differential includes a flare of the patient's known HHD, secondary bacterial or fungal infection, or a superimposed viral infection (eg, HSV, zoster). Histologic evidence of herpetic infection would be absent in an uncomplicated flare of HHD. Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection that can present in 2 clinical forms: a vesiculopustular type and less commonly a bullous type. It is caused by Staphylococcus aureus in most cases. In multiple myeloma with cutaneous dissemination, a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells would be evident. Lastly, tinea corporis is caused by dermatophytes that can be seen on hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The diagnosis of eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD should be considered in patients who present with grouped vesicles or hemorrhagic or punched-out erosions in areas of pre-existing HHD. The diagnosis can be confirmed by Tzanck smear, viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, or histopathology (with or without immunohistochemistry).1,2,6 When eczema herpeticum is suspected, prompt antiviral administration is imperative to limit life-threatening systemic spread.

- Hailey J, Hailey H. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:679-685.

- de Aquino Paulo Filho T, deFreitas YK, da Nóbrega MT, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease associated with herpetic eczema-the value of the Tzanck smear test. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:29-31.

- Flint ID, Spencer DM, Wilkin JK. Eczema herpeticum in association with familial benign chronic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2, pt 1):257-259.

- Leppard B, Delaney TJ, Sanderson KV. Chronic benign familial pemphigus. induction of lesions by Herpesvirus hominis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:609-613.

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zamperetti M, Pichler M, Perino F, et al. Ein fall von morbus Hailey-Hailey in verbindung mit einem eczema herpeticatum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1035-1038.

- Ingrand D, Briquet I, Babinet JM, et al. Eczema herpeticum of the child. an unusual manifestation of herpes simplex virus infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1985;24:660-663.

- Finlow C, Thomas J. Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:36-39.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption (Eczema Herpeticum)

Polymerase chain reaction confirmed presence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, and the patient was started on intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours). Diagnosis was further supported by histopathologic examination with confirmatory immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). The patient's anemia and thrombocytopenia also were attributed to widespread HSV infection.

Approximately 8 hours after the patient was started on acyclovir, he developed increasing tremors, confusion, and impaired speech. Lumbar puncture confirmed the presence of HSV-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid. Despite ongoing intravenous antiviral therapy, he required intubation 6 days after hospitalization due to impaired mental status and myoclonic jerking. He remained intubated, unresponsive, and in critical condition for 9 days before he gradually began to demonstrate cognitive recovery. He subsequently was weaned off the ventilator, his mental status returned to normal, and his skin rash slowly resolved (Figure 2).

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus, is a rare autosomal-dominant condition first described by Howard and Hugh Hailey in 1939.1 It is a chronic blistering process characterized by epidermal fragility, often manifesting as macerated fissured erosions in areas exposed to heat and friction (eg, axillae, groin). Hailey-Hailey disease results from a defective calcium transporter (ATP2C1 gene), leading to impaired keratinocyte adhesion.2

Eczema herpeticum refers to the dissemination of herpes infection to areas of compromised skin barrier. Although originally used to describe HSV infection in patients with atopic dermatitis, eczema herpeticum has been described in various conditions that affect the skin barrier function, including Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mycosis fungoides, among others.3 When applied to skin conditions other than atopic dermatitis, it sometimes is referred to as Kaposi varicelliform eruption.2

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly is complicated by a bacterial or fungal infection, including impetigo, tinea, or candidiasis. The first case of HHD complicated by HSV infection was reported in 1973.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms benign familial pemphigus AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND eczema herpeticum, Hailey-Hailey AND Kaposi varicelliform eruption, and Hailey-Hailey herpeticum revealed 15 cases of HHD complicated by eczema herpeticum.4-6 Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a rare and life-threatening complication of eczema herpeticum.7,8 We report a case of HSV encephalitis resulting from eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD.

The clinical differential includes a flare of the patient's known HHD, secondary bacterial or fungal infection, or a superimposed viral infection (eg, HSV, zoster). Histologic evidence of herpetic infection would be absent in an uncomplicated flare of HHD. Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection that can present in 2 clinical forms: a vesiculopustular type and less commonly a bullous type. It is caused by Staphylococcus aureus in most cases. In multiple myeloma with cutaneous dissemination, a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells would be evident. Lastly, tinea corporis is caused by dermatophytes that can be seen on hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The diagnosis of eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD should be considered in patients who present with grouped vesicles or hemorrhagic or punched-out erosions in areas of pre-existing HHD. The diagnosis can be confirmed by Tzanck smear, viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, or histopathology (with or without immunohistochemistry).1,2,6 When eczema herpeticum is suspected, prompt antiviral administration is imperative to limit life-threatening systemic spread.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption (Eczema Herpeticum)

Polymerase chain reaction confirmed presence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, and the patient was started on intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours). Diagnosis was further supported by histopathologic examination with confirmatory immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). The patient's anemia and thrombocytopenia also were attributed to widespread HSV infection.

Approximately 8 hours after the patient was started on acyclovir, he developed increasing tremors, confusion, and impaired speech. Lumbar puncture confirmed the presence of HSV-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid. Despite ongoing intravenous antiviral therapy, he required intubation 6 days after hospitalization due to impaired mental status and myoclonic jerking. He remained intubated, unresponsive, and in critical condition for 9 days before he gradually began to demonstrate cognitive recovery. He subsequently was weaned off the ventilator, his mental status returned to normal, and his skin rash slowly resolved (Figure 2).

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus, is a rare autosomal-dominant condition first described by Howard and Hugh Hailey in 1939.1 It is a chronic blistering process characterized by epidermal fragility, often manifesting as macerated fissured erosions in areas exposed to heat and friction (eg, axillae, groin). Hailey-Hailey disease results from a defective calcium transporter (ATP2C1 gene), leading to impaired keratinocyte adhesion.2

Eczema herpeticum refers to the dissemination of herpes infection to areas of compromised skin barrier. Although originally used to describe HSV infection in patients with atopic dermatitis, eczema herpeticum has been described in various conditions that affect the skin barrier function, including Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mycosis fungoides, among others.3 When applied to skin conditions other than atopic dermatitis, it sometimes is referred to as Kaposi varicelliform eruption.2

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly is complicated by a bacterial or fungal infection, including impetigo, tinea, or candidiasis. The first case of HHD complicated by HSV infection was reported in 1973.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms benign familial pemphigus AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND eczema herpeticum, Hailey-Hailey AND Kaposi varicelliform eruption, and Hailey-Hailey herpeticum revealed 15 cases of HHD complicated by eczema herpeticum.4-6 Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a rare and life-threatening complication of eczema herpeticum.7,8 We report a case of HSV encephalitis resulting from eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD.

The clinical differential includes a flare of the patient's known HHD, secondary bacterial or fungal infection, or a superimposed viral infection (eg, HSV, zoster). Histologic evidence of herpetic infection would be absent in an uncomplicated flare of HHD. Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection that can present in 2 clinical forms: a vesiculopustular type and less commonly a bullous type. It is caused by Staphylococcus aureus in most cases. In multiple myeloma with cutaneous dissemination, a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells would be evident. Lastly, tinea corporis is caused by dermatophytes that can be seen on hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The diagnosis of eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD should be considered in patients who present with grouped vesicles or hemorrhagic or punched-out erosions in areas of pre-existing HHD. The diagnosis can be confirmed by Tzanck smear, viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, or histopathology (with or without immunohistochemistry).1,2,6 When eczema herpeticum is suspected, prompt antiviral administration is imperative to limit life-threatening systemic spread.

- Hailey J, Hailey H. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:679-685.

- de Aquino Paulo Filho T, deFreitas YK, da Nóbrega MT, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease associated with herpetic eczema-the value of the Tzanck smear test. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:29-31.

- Flint ID, Spencer DM, Wilkin JK. Eczema herpeticum in association with familial benign chronic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2, pt 1):257-259.

- Leppard B, Delaney TJ, Sanderson KV. Chronic benign familial pemphigus. induction of lesions by Herpesvirus hominis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:609-613.

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zamperetti M, Pichler M, Perino F, et al. Ein fall von morbus Hailey-Hailey in verbindung mit einem eczema herpeticatum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1035-1038.

- Ingrand D, Briquet I, Babinet JM, et al. Eczema herpeticum of the child. an unusual manifestation of herpes simplex virus infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1985;24:660-663.

- Finlow C, Thomas J. Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:36-39.

- Hailey J, Hailey H. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:679-685.

- de Aquino Paulo Filho T, deFreitas YK, da Nóbrega MT, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease associated with herpetic eczema-the value of the Tzanck smear test. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:29-31.

- Flint ID, Spencer DM, Wilkin JK. Eczema herpeticum in association with familial benign chronic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2, pt 1):257-259.

- Leppard B, Delaney TJ, Sanderson KV. Chronic benign familial pemphigus. induction of lesions by Herpesvirus hominis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:609-613.

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zamperetti M, Pichler M, Perino F, et al. Ein fall von morbus Hailey-Hailey in verbindung mit einem eczema herpeticatum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1035-1038.

- Ingrand D, Briquet I, Babinet JM, et al. Eczema herpeticum of the child. an unusual manifestation of herpes simplex virus infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1985;24:660-663.

- Finlow C, Thomas J. Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:36-39.

A 62-year-old man with a long-standing history (>40 years) of Hailey-Hailey disease was admitted from an outside hospital due to anemia (hemoglobin, 8.6 g/dL [reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (platelets, 7×103 /µL [reference range, 150–350×103 /µL]), and worsening skin rash. The patient reported that his Hailey-Hailey disease worsened abruptly 1 month prior to admission and had progressed steadily since then. He described the rash as painful, especially with movement. Over the preceding month, he had been treated with topical triamcinolone, topical diphenhydramine, oral prednisone, fluconazole, and oral clindamycin, all without improvement. The skin lesions continued to worsen and persistently bled; he then presented to our institution for further care.

Physical examination demonstrated widespread shallow erosions with hemorrhagic drainage and crusting located on the lower back, chest, abdomen (top), axillae (bottom), groin, arms, and legs. No vesicles or pustules were noted. The patient had no cognitive dysfunction or focal neurologic deficits. A punch biopsy was performed.

Erythematous Plaque on the Scalp With Alopecia

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

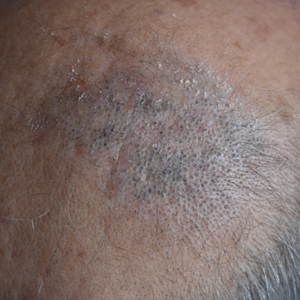

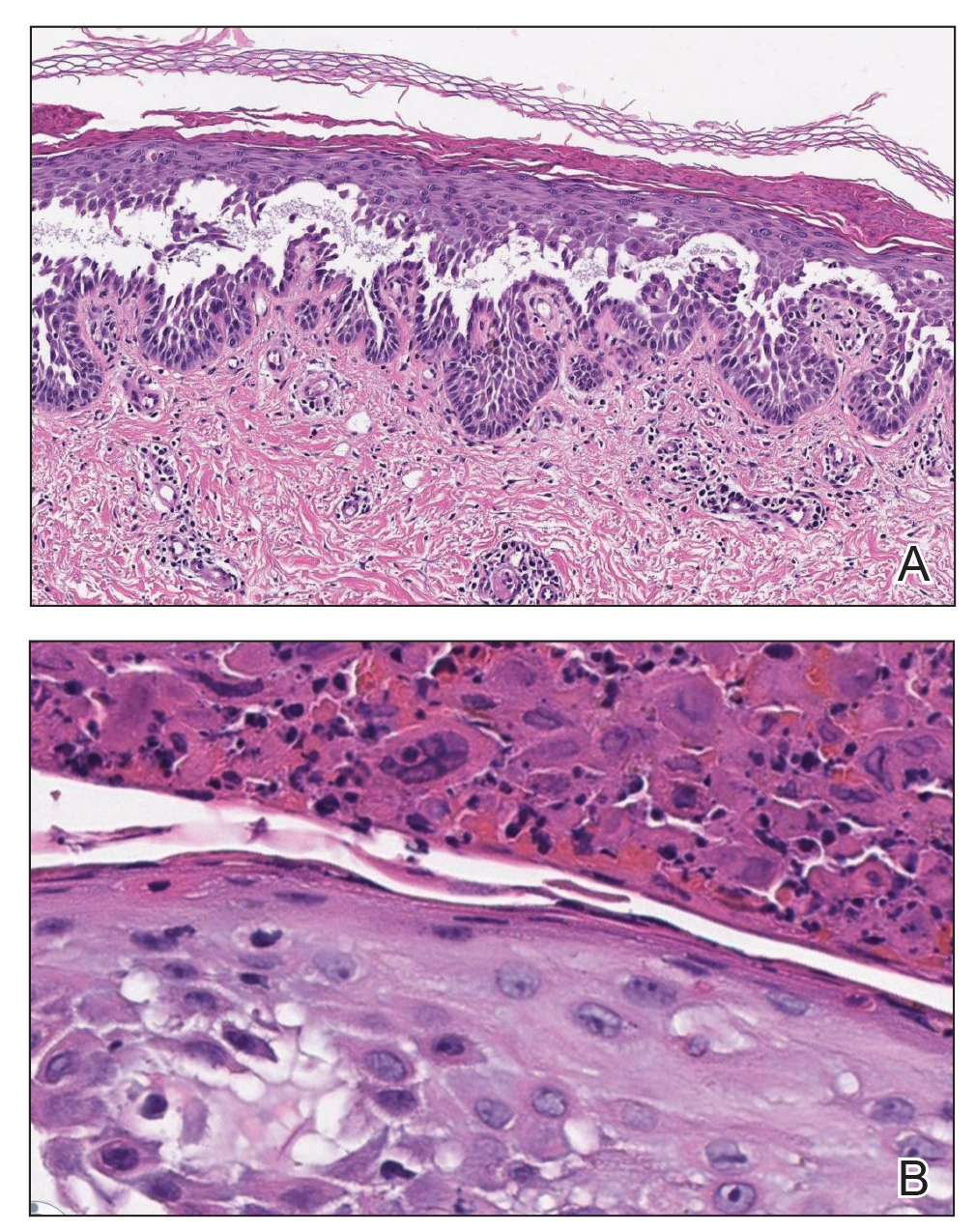

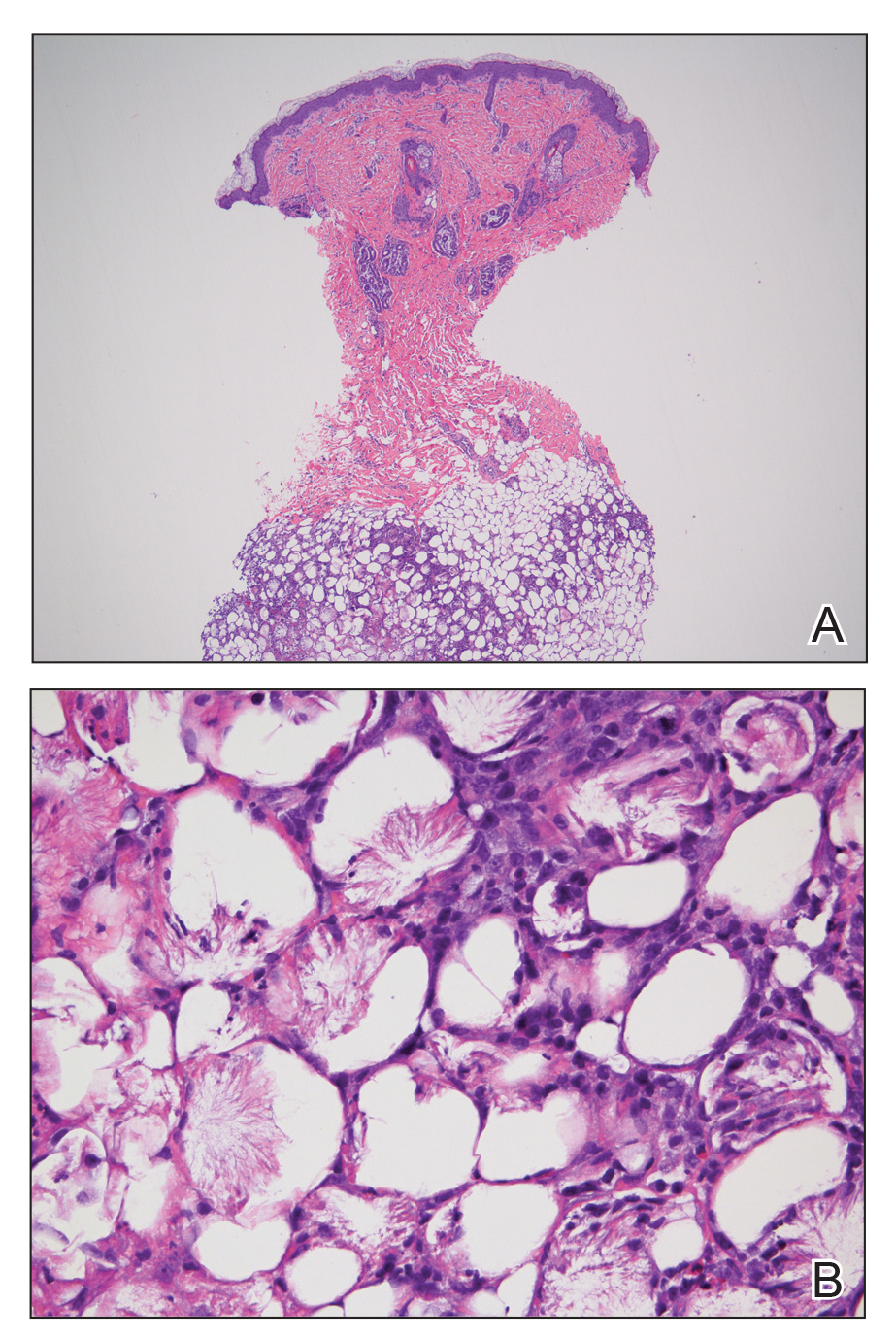

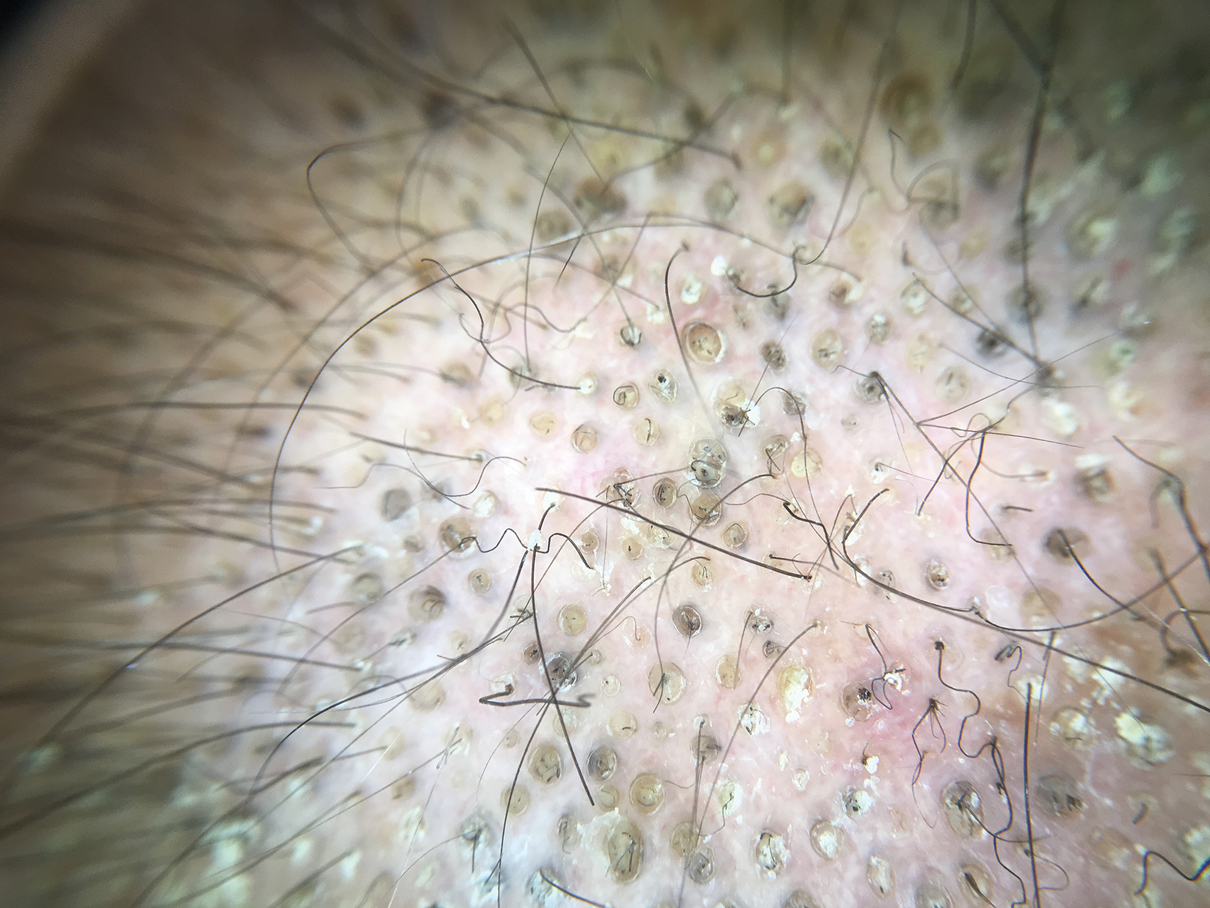

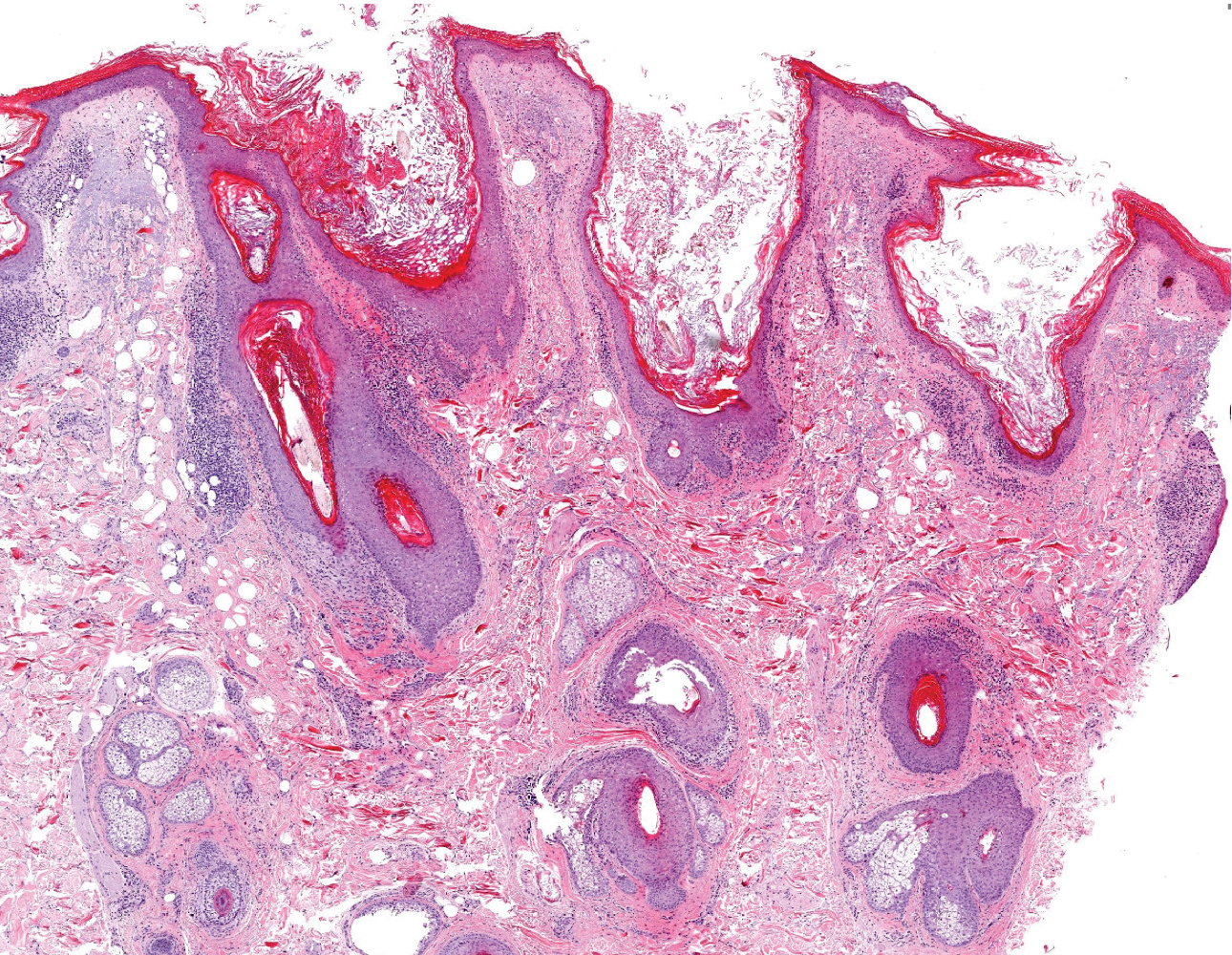

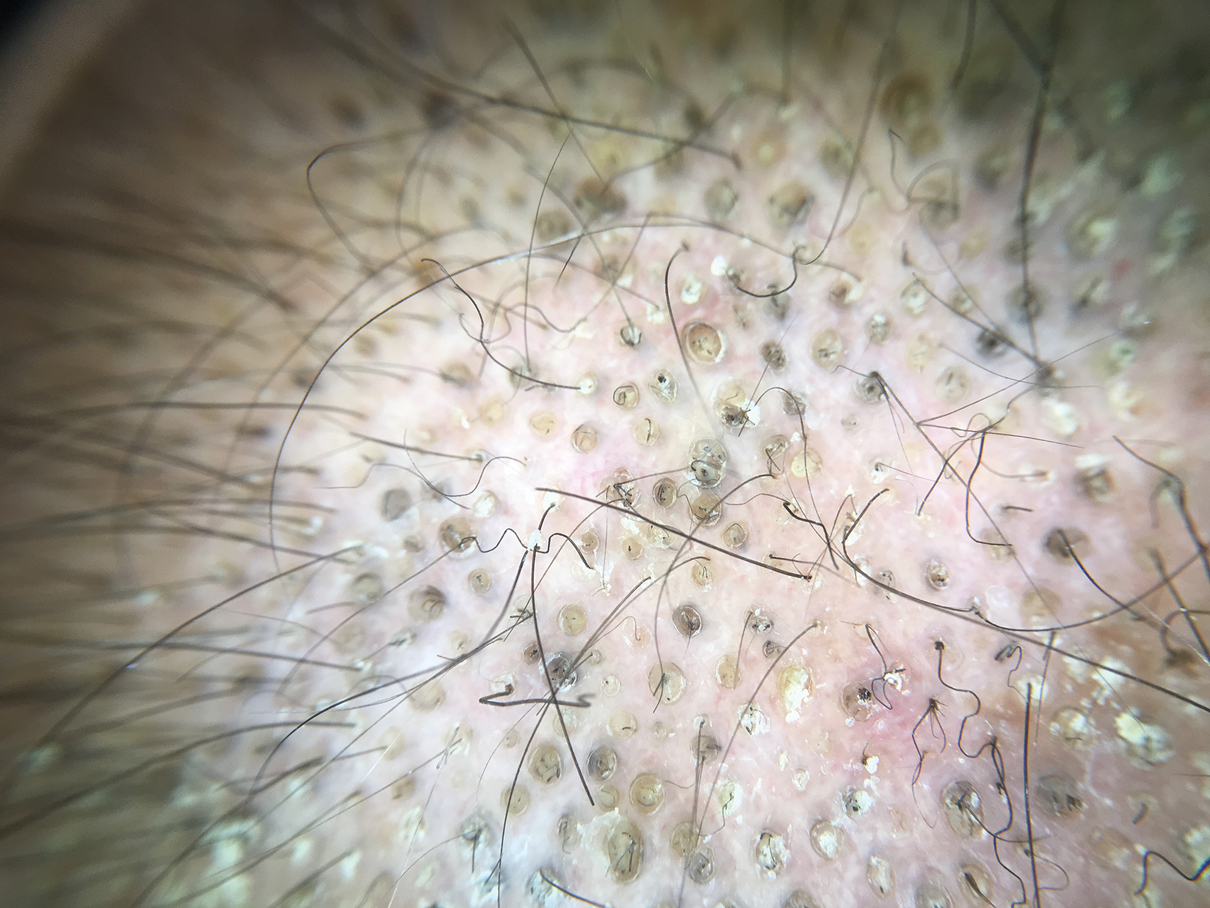

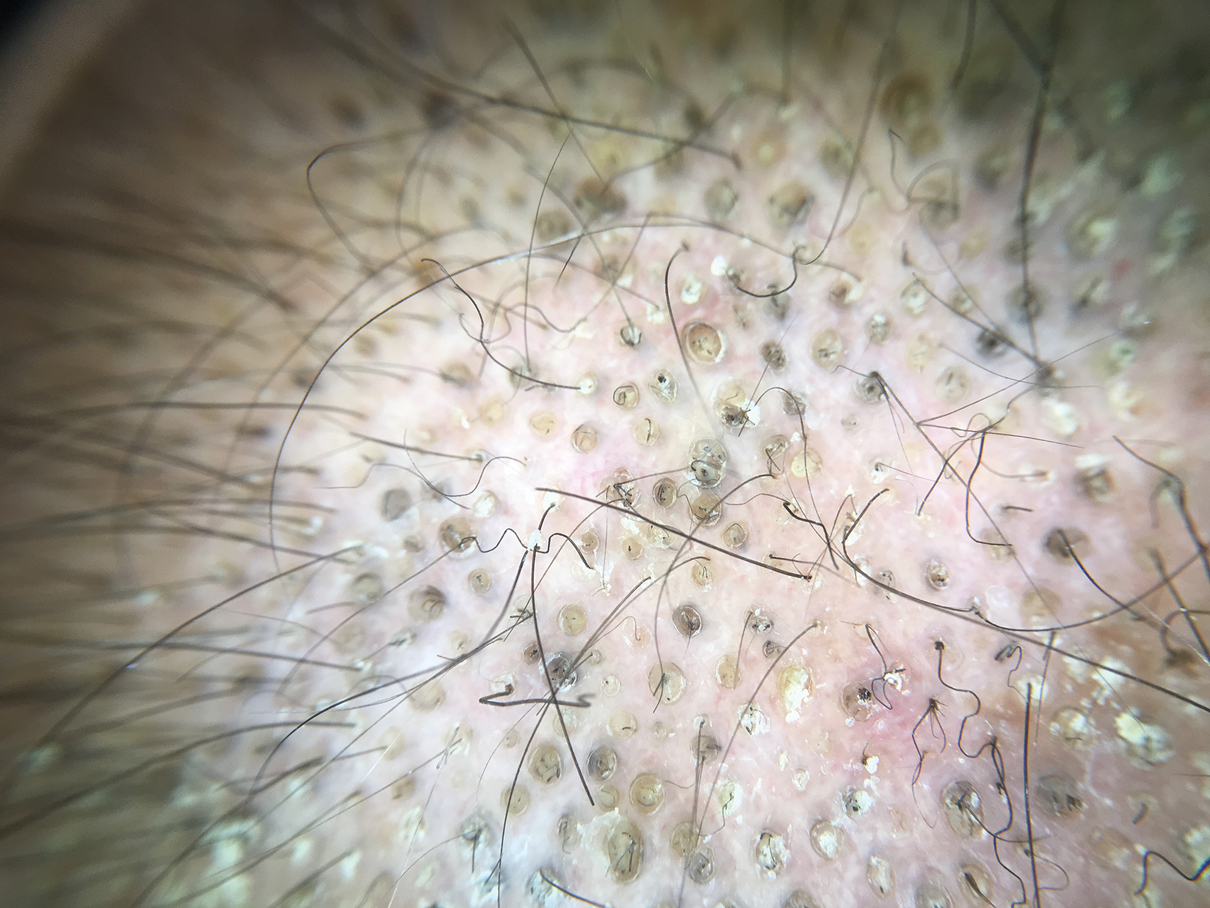

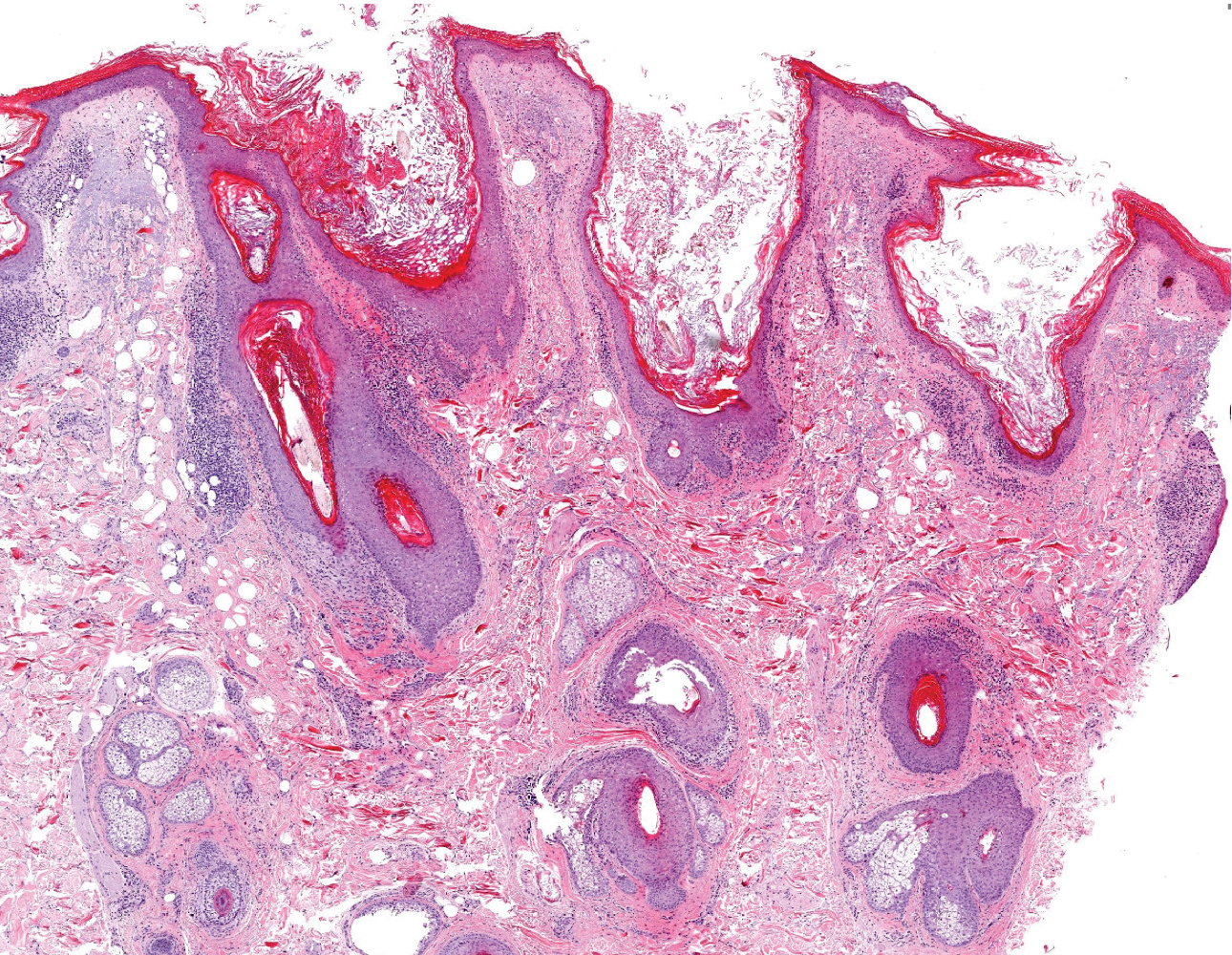

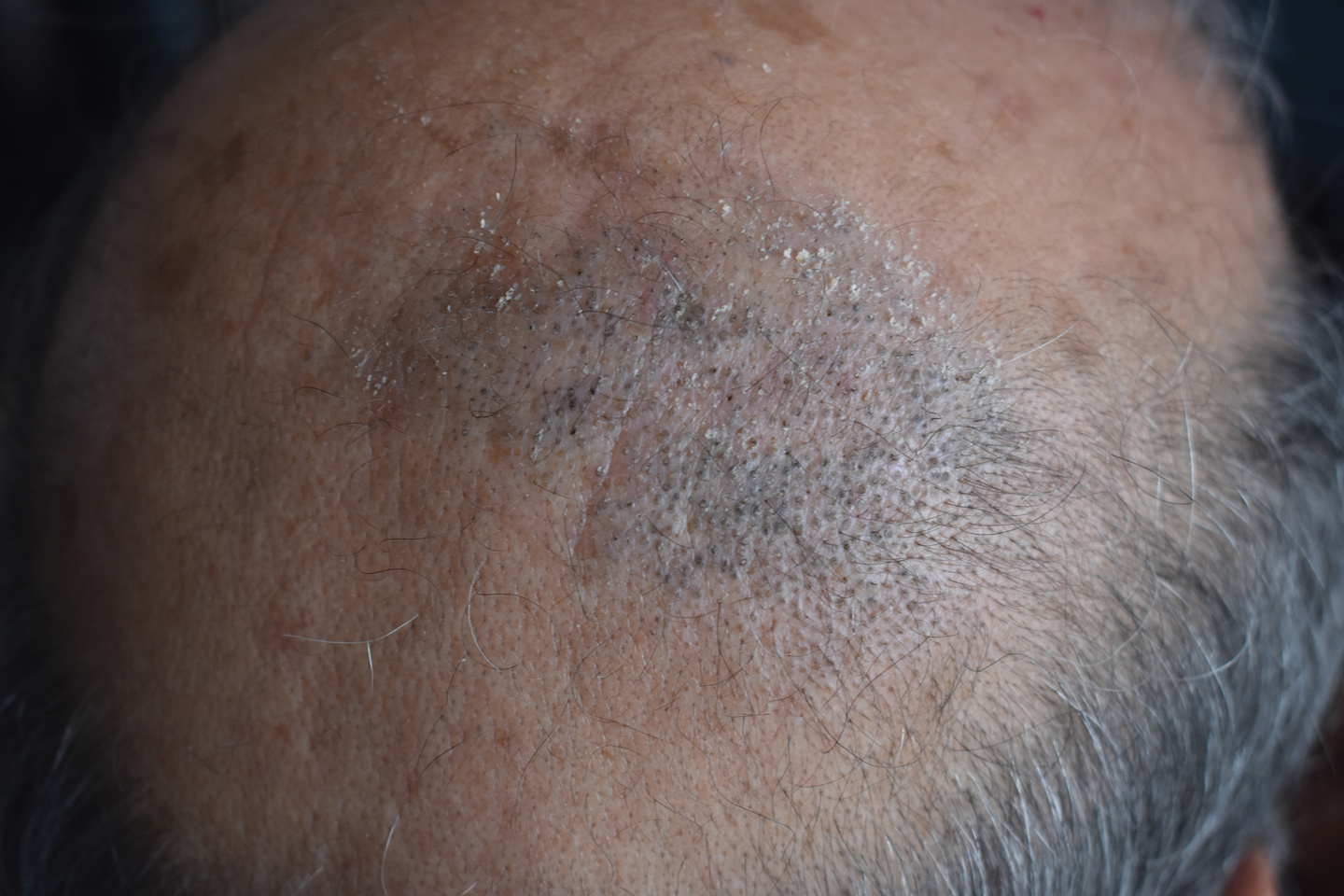

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

A 37-year-old woman presented with a 2×6-cm, firm, erythematous plaque on the parietal region of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. No history of injury to the scalp was noted. The patient noticed hair loss in the affected area in the month prior to presentation. She was afebrile and otherwise asymptomatic. She denied a family history of similar scalp disorders.

Erythematous Plaque on the Back of a Newborn

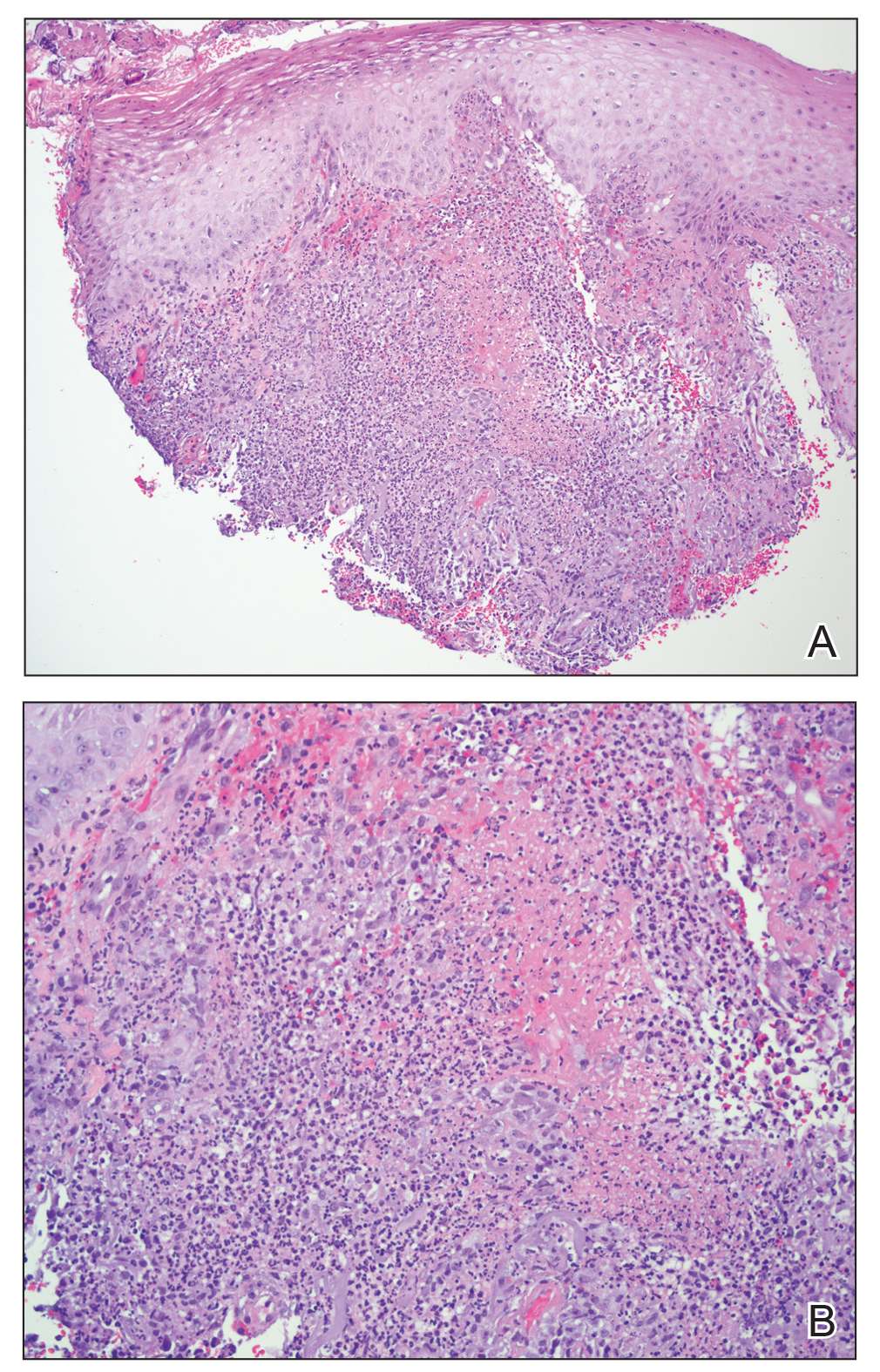

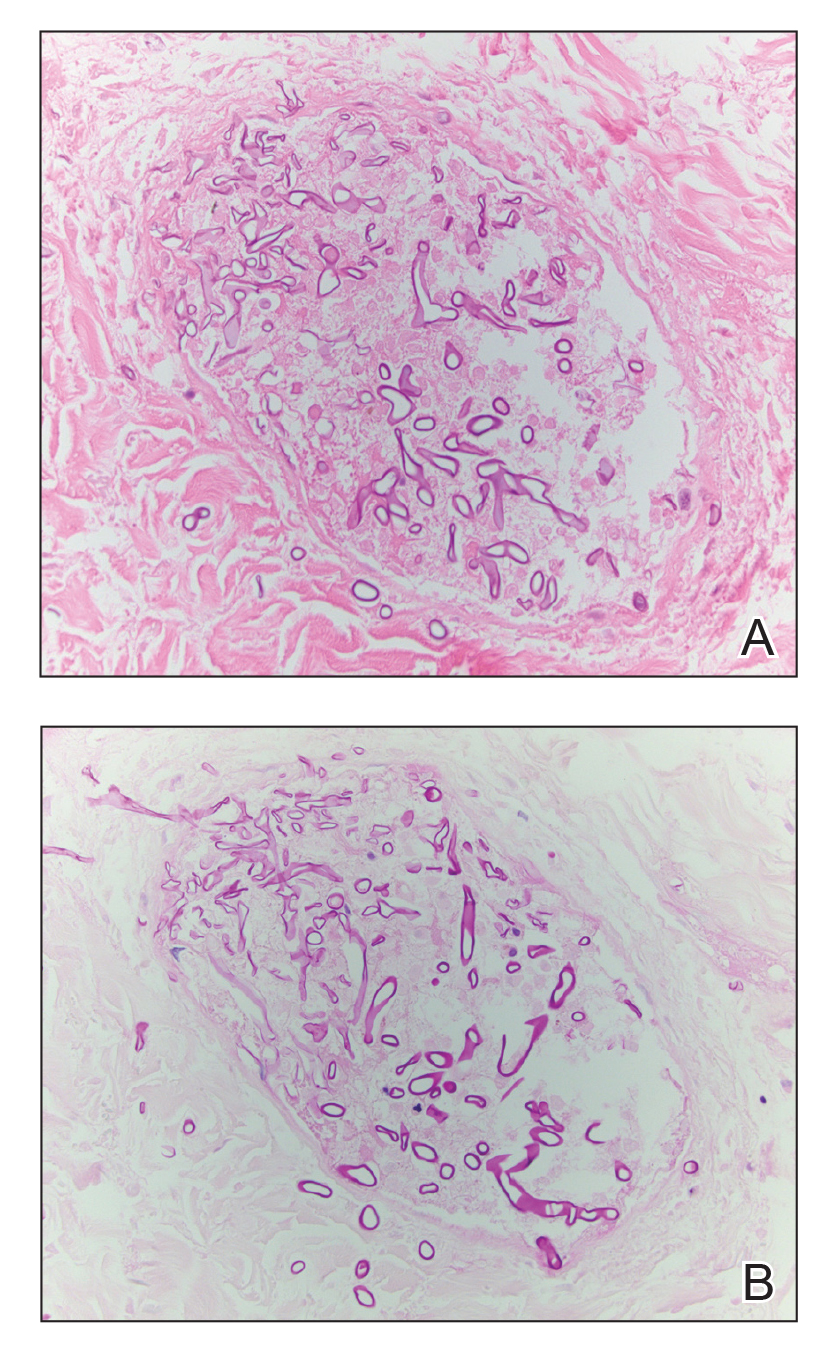

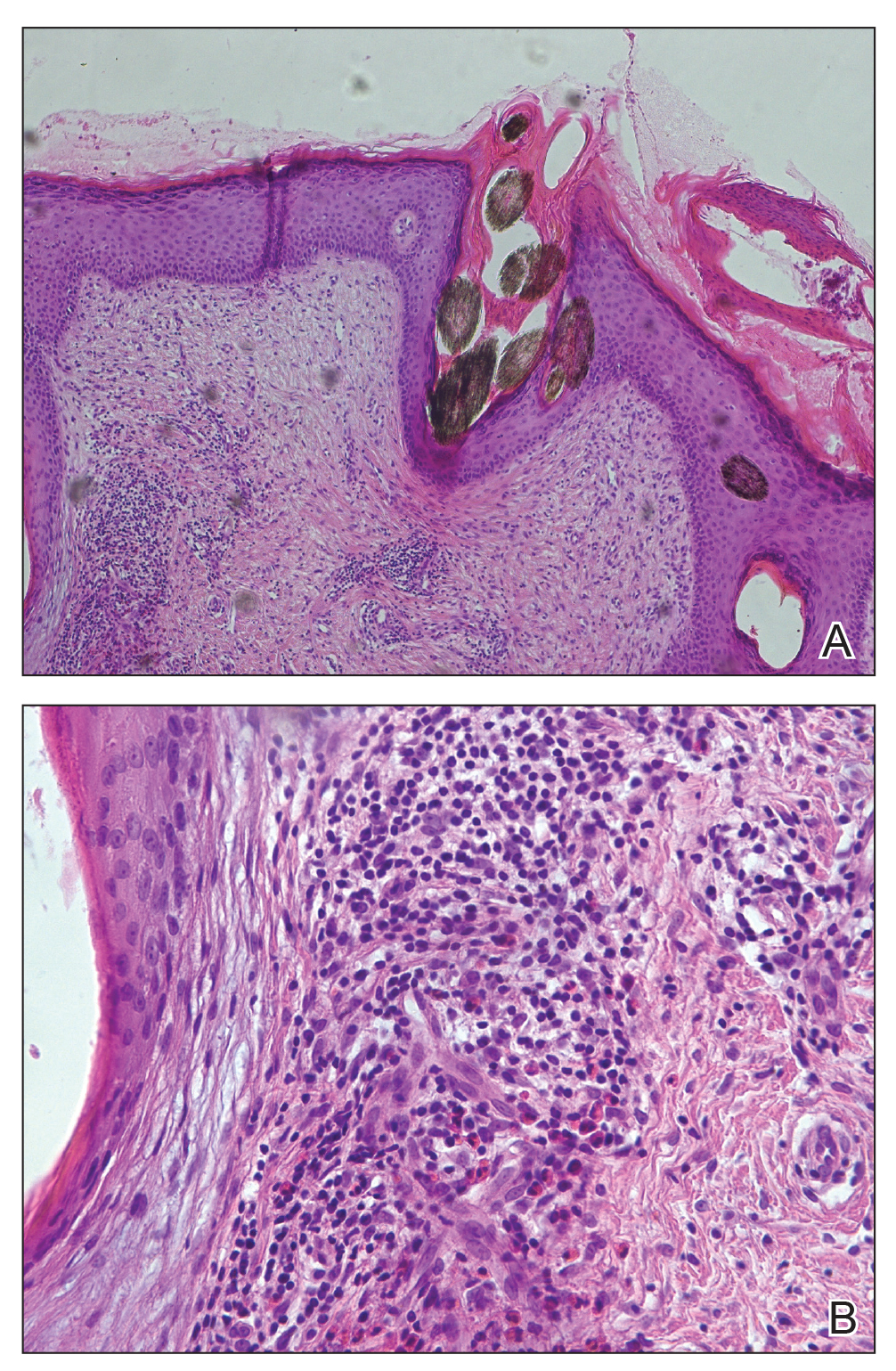

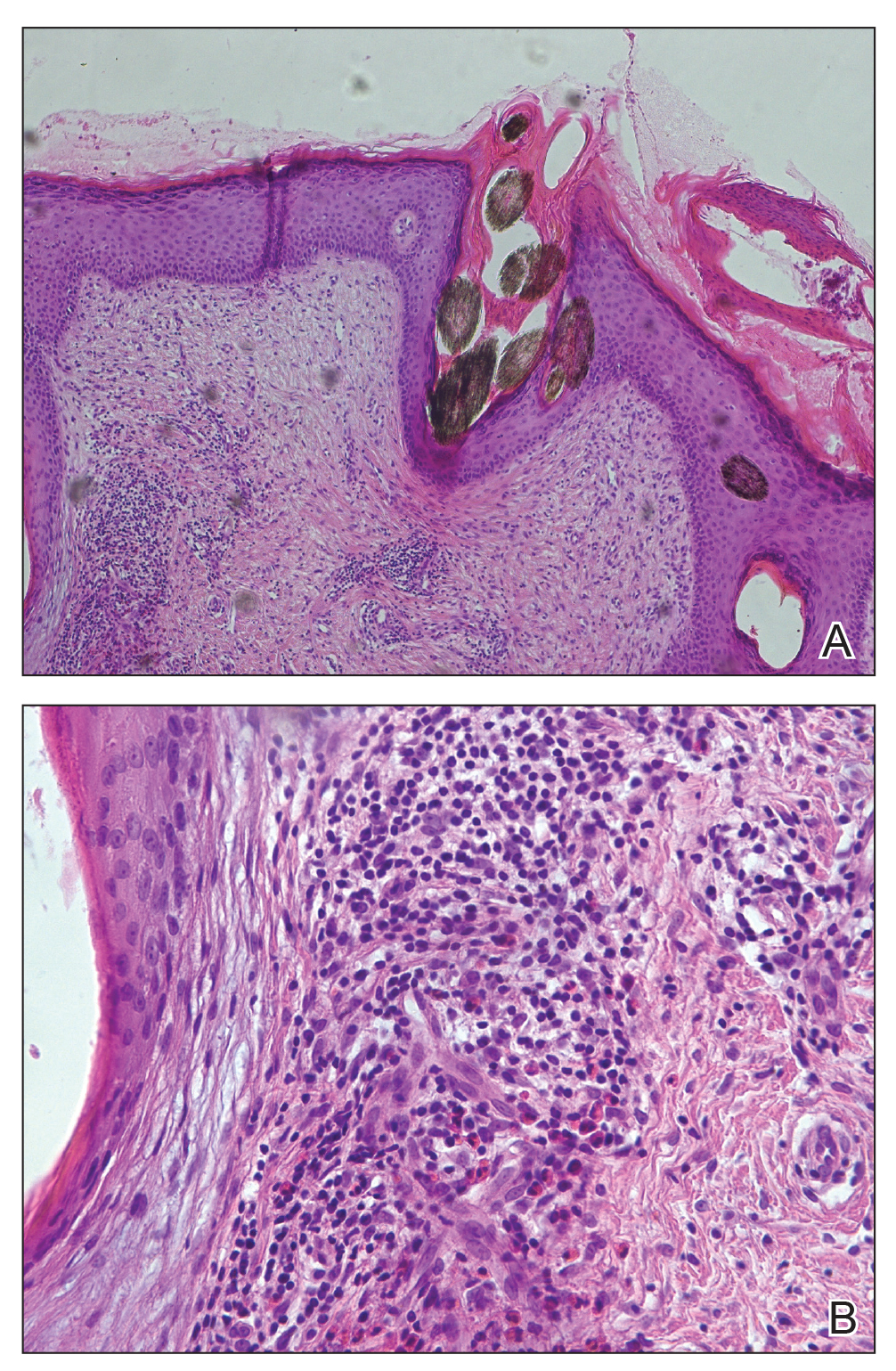

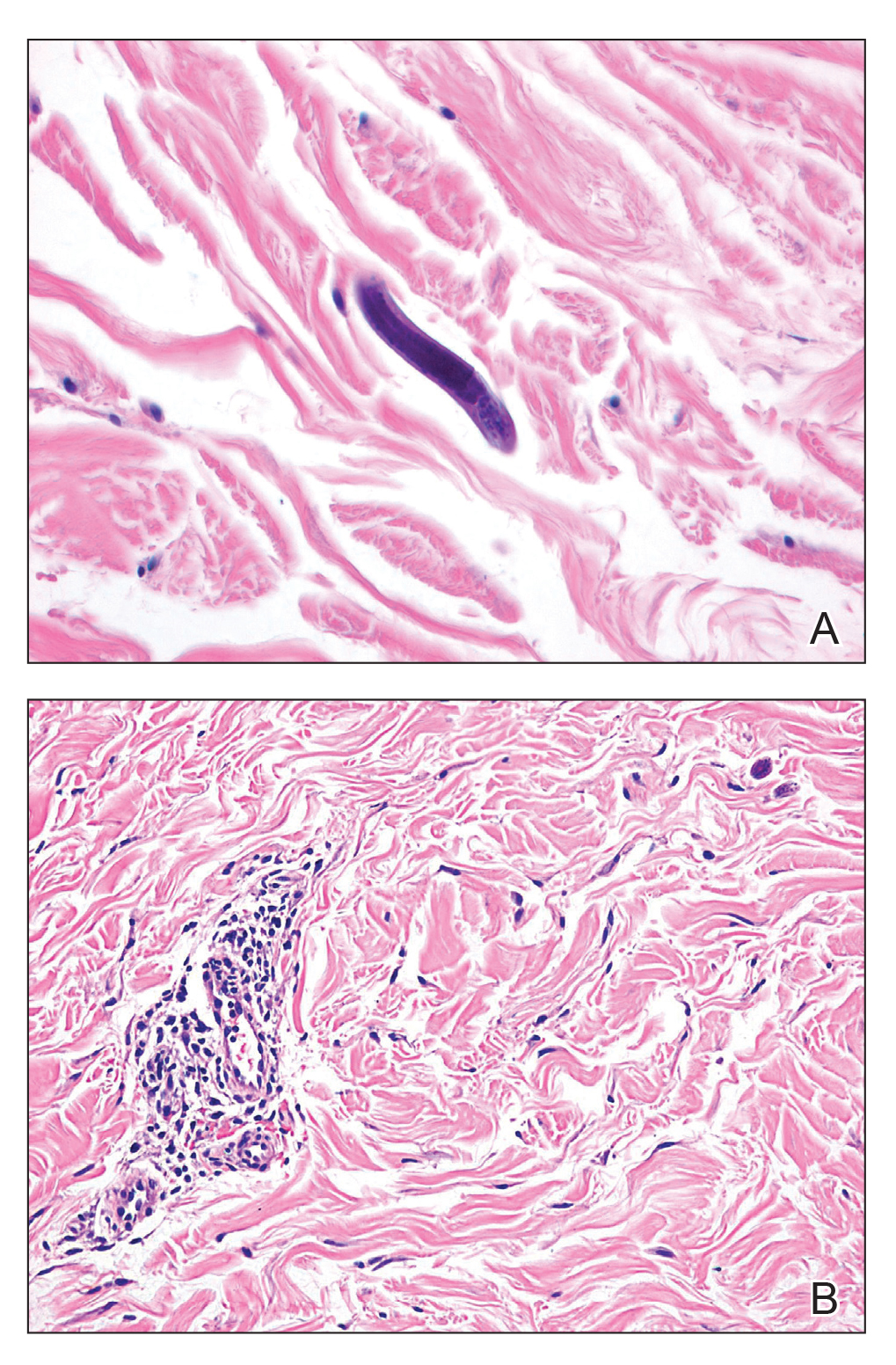

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.