User login

Cutaneous Odontogenic Sinus: An Inflammatory Mimicker of Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Epidermal Cysts

Clinical Challenge

An

Practice Gap

It is estimated that half of patients with an extraoral fistula are treated with multiple dermatologic surgical operations, radiotherapy, antibiotic therapy, and chemotherapy before the correct diagnosis is made.1 Thus, proper identification of these lesions is crucial for prognosis and treatment. The most common locations for OCSTs are the mandibular, submandibular, and cervical skin.1,2 Given these locations, patients with OCSTs commonly present to the dermatology office for evaluation. Education regarding the clinical presentation, histopathology, and proper evaluation and further referral for treatment is essential for dermatologists.

Tools and Technique for Diagnosis

We present 2 patients with OCSTs who were referred for cutaneous surgery for an SCC and epidermal cyst, but the proper diagnosis was rendered after an index of suspicion and clinicopathologic correlation led to additional testing and eventual referral for imaging.

Patient 1

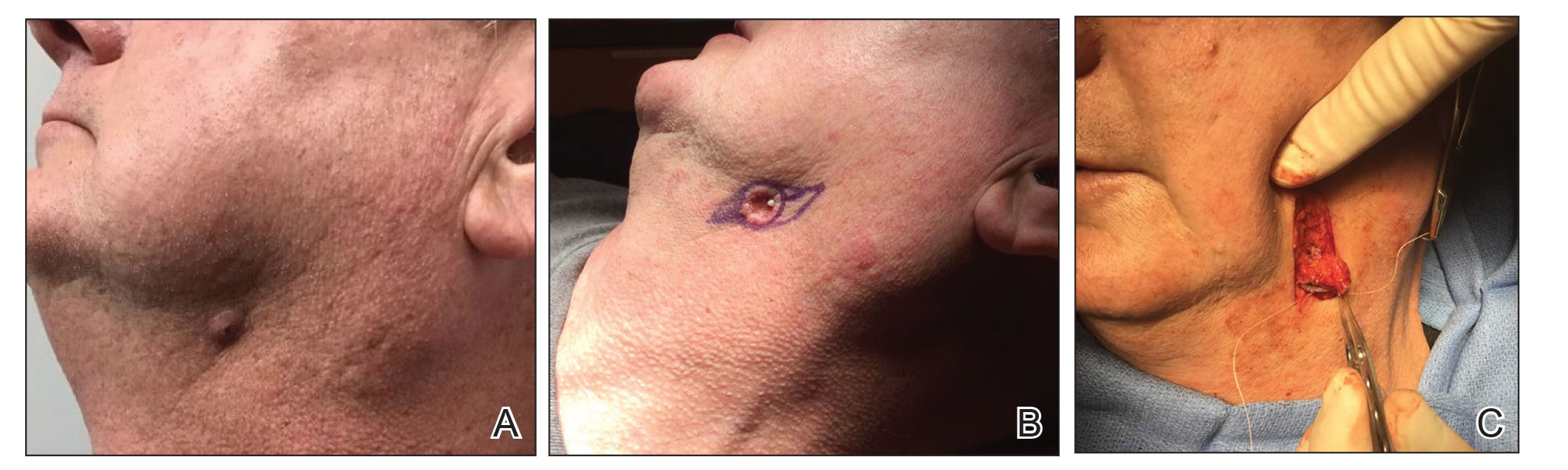

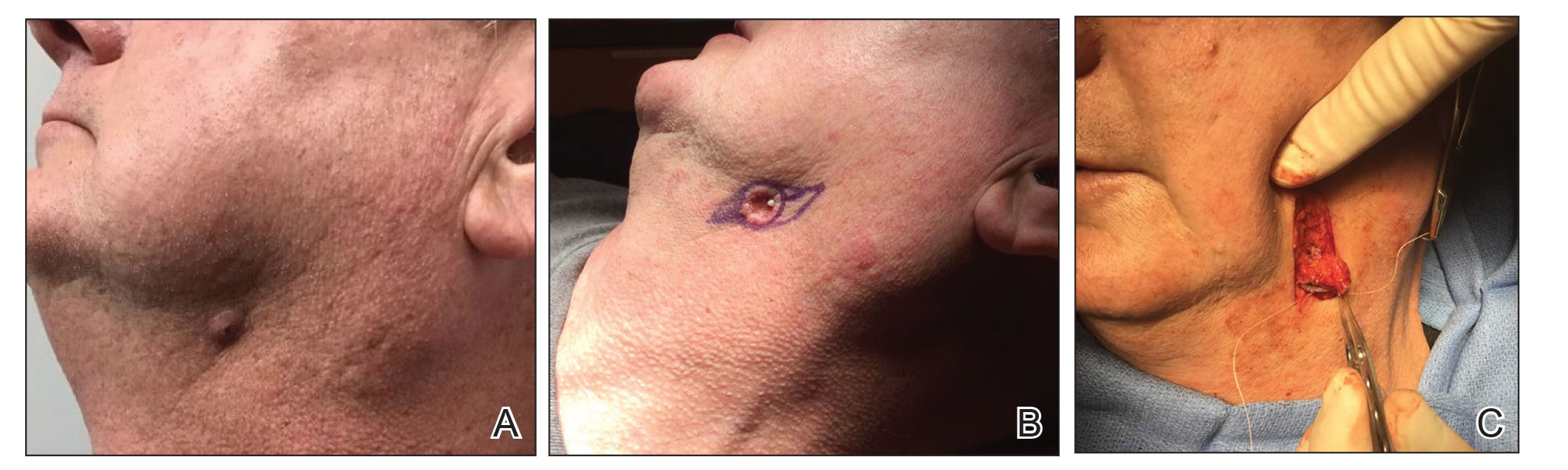

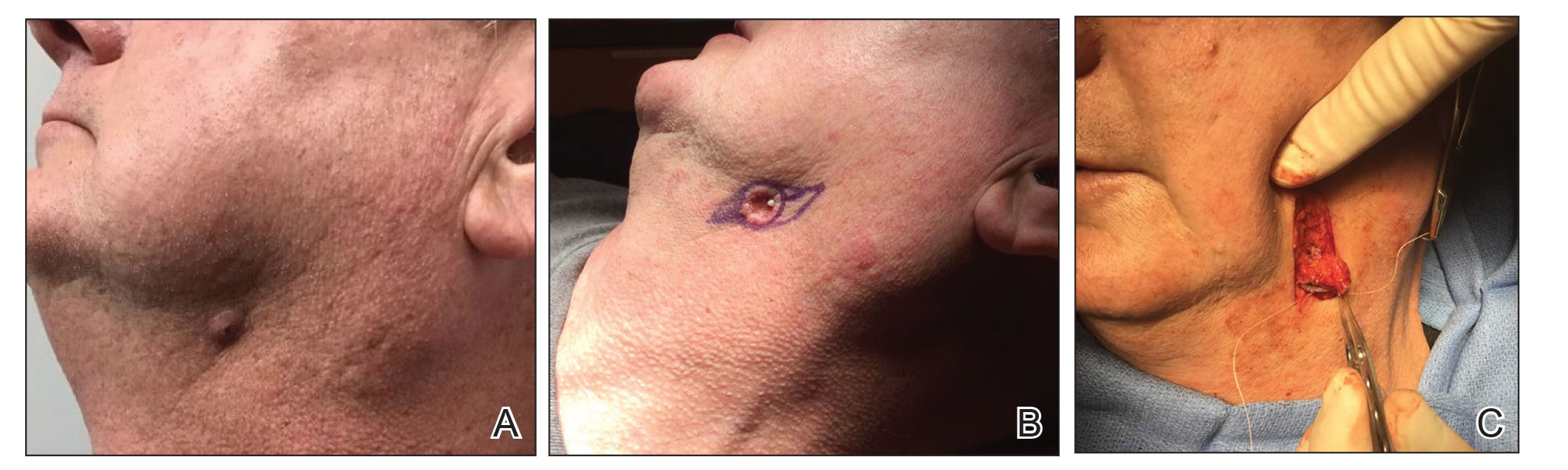

A 68-year-old woman presented for Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) of a biopsy-proven SCC on the chin. The tumor cleared after 2 MMS stages (Figure 1A). Due to notable inflammation in each stage, the slides were sent to a pathologist who confirmed clear margins. Within 2 weeks of MMS, the wound began to dehisce (Figure 1B). The patient presented 4 months later with a crusted ulcerated nodule at the MMS site (Figure 1C). A biopsy showed likely recurrence of SCC. Upon presentation to the Mohs surgeon, the nodule felt fixed to the underlying jaw, and the patient was noted to have poor dentition. The patient was sent for computed tomography (CT), which showed focal thinning of the mandible, likely postsurgical, and clear maxillary sinuses. Due to the clinical appearance and anatomic location of the lesion, a request was made for a second read of the CT, specifically looking for an OCST at the prior surgical site. With this information, the radiologist noted an OCST extending from the mandible to the lesion, reported as a periapical lucency (representing a periapical abscess) at a mandibular tooth with a dental sinus draining into the soft tissues. The patient was started on antibiotics and referred to an oral surgeon for OCST excision.

Patient 2

A 62-year-old man presented with an inflamed subcutaneous nodule on the left anterior neck. A biopsy showed a ruptured cyst, and the patient was referred for excision. Clinical examination revealed a subcutaneous nodule fixed to the lower portion of the mandible (Figure 2A) that exhibited a rubbery retraction when pulled (Figure 2B). After a discussion about the atypical feel and appearance of this cyst, the patient preferred to undergo excision. During excision, the lesion felt deep and fixed with retraction (Figure 2C). With intraoperative re-evaluation of the clinical scenario and location, the patient was sent for CT. The initial read noted clear maxillary and ethmoid sinuses, with no mention of an OCST. After discussing the clinical history and suspicion specifically for an OCST with the radiologist, the re-read showed notable inflammation and decay of the tooth adjacent to the area of interest. An OCST was diagnosed, and the patient was sent to an oral surgeon for excision after antibiotics were prescribed.

Practice Implications

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts commonly are misdiagnosed due to variations in clinical presentations resembling more common cutaneous diagnoses, nonspecific histopathologic findings, and lack of dental symptoms or concerns about dentition. Clinically, an OCST presents as a fixed, red, crusty, nontender nodule with intermittent draining. With palpation of the involved area, the clinician may feel a cord of tissue connecting the skin lesion intraorally.2,4 A clinician should have a high index of suspicion for an OCST when evaluating fixed lesions of the lower face, jawline, and neck due to the possibility of a dental origin,1 which is important because an OCST can have similar clinical findings to lesions such as congenital fistulas, pustules, cysts, osteomyelitis, foreign-body granulomas, pyogenic granulomas, syphilis, metastatic carcinomas, basal cell carcinomas, and SCCs.2,4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mohs, MMS, chemosurgery, odontogenic sinus, odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract, and dental sinus yielded only 2 OCSTs that were referred for MMS in the last 30 years, both of which were in the nasolabial fold/medial malar cheek.2,4 Histopathologic findings of an OCST are nonspecific; a mixed or granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, granulation tissue, and scarring can be seen.1 Pseudocarcinomatous/pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis can be seen and cause histologic misinterpretation for an SCC.2 Given that these findings are nonspecific without a clinical context, even with a histopathologic diagnosis of SCC or cyst, a clinical suspicion for an OCST should lead to an intraoral examination. Imaging can be ordered to look for an OCST in the area of interest. Although panoramic or periapical radiography with or without dental probes/radiopaque markers commonly have been used, more recent literature has suggested that CT may be superior to radiographs for making an OCST diagnosis.1,3 If imaging is not consistent with the clinically suspected OCST, we recommend directly contacting the radiologist to explain the clinical history and even refresh his/her suspicion for this diagnosis.

If a diagnosis of an OCST is made, oral antibiotics can be prescribed, though the use of antibiotics has been controversial. For severe odontogenic infections, typically beta-lactam antibiotics, cephalosporins, metronidazole, clindamycin, moxifloxacin, or erythromycin can be given for 7 days or until 3 days after symptoms have resolved.5 Although antibiotics can bring temporary resolution, it is imperative to treat the source of infection to prevent recurrence. It is crucial for these patients to be referred to an oral surgeon for evaluation and treatment of OCST by either a root canal or tooth extraction.

Final Thoughts

We present this pearl on the diagnosis and management of an OCST, also known as a dental sinus, to better assist clinicians in making this diagnosis. With an index of suspicion as well as intraoral and radiologic evaluations, a proper diagnosis may be rendered, potentially avoiding unnecessary cutaneous surgery. In addition, we highlight the importance of communication between the clinician and the radiologist to directly look for OCST in the area of concern and consider a re-read of the images when clinical suspicion does not correlate with the radiology report.

- Bai J, Ji AP, Huang MW. Submental cutaneous sinus tract of mandibular second molar origin. Int Endod J. 2014;47:1185-1191.

- Plast Reconstr Surg.

- Gregoire C. How are odontogenic infections best managed? J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a37.

- Bodner L, Bar-Ziv J. Cutaneous sinus tract of dental origin—imaging with a dental CT software programme. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:311-313.

- Peermohamed S, Barber D, Kurwa H. Diagnostic challenges of cutaneous draining sinus tracts of odontogenic origin: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1525-1527.

Clinical Challenge

An

Practice Gap

It is estimated that half of patients with an extraoral fistula are treated with multiple dermatologic surgical operations, radiotherapy, antibiotic therapy, and chemotherapy before the correct diagnosis is made.1 Thus, proper identification of these lesions is crucial for prognosis and treatment. The most common locations for OCSTs are the mandibular, submandibular, and cervical skin.1,2 Given these locations, patients with OCSTs commonly present to the dermatology office for evaluation. Education regarding the clinical presentation, histopathology, and proper evaluation and further referral for treatment is essential for dermatologists.

Tools and Technique for Diagnosis

We present 2 patients with OCSTs who were referred for cutaneous surgery for an SCC and epidermal cyst, but the proper diagnosis was rendered after an index of suspicion and clinicopathologic correlation led to additional testing and eventual referral for imaging.

Patient 1

A 68-year-old woman presented for Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) of a biopsy-proven SCC on the chin. The tumor cleared after 2 MMS stages (Figure 1A). Due to notable inflammation in each stage, the slides were sent to a pathologist who confirmed clear margins. Within 2 weeks of MMS, the wound began to dehisce (Figure 1B). The patient presented 4 months later with a crusted ulcerated nodule at the MMS site (Figure 1C). A biopsy showed likely recurrence of SCC. Upon presentation to the Mohs surgeon, the nodule felt fixed to the underlying jaw, and the patient was noted to have poor dentition. The patient was sent for computed tomography (CT), which showed focal thinning of the mandible, likely postsurgical, and clear maxillary sinuses. Due to the clinical appearance and anatomic location of the lesion, a request was made for a second read of the CT, specifically looking for an OCST at the prior surgical site. With this information, the radiologist noted an OCST extending from the mandible to the lesion, reported as a periapical lucency (representing a periapical abscess) at a mandibular tooth with a dental sinus draining into the soft tissues. The patient was started on antibiotics and referred to an oral surgeon for OCST excision.

Patient 2

A 62-year-old man presented with an inflamed subcutaneous nodule on the left anterior neck. A biopsy showed a ruptured cyst, and the patient was referred for excision. Clinical examination revealed a subcutaneous nodule fixed to the lower portion of the mandible (Figure 2A) that exhibited a rubbery retraction when pulled (Figure 2B). After a discussion about the atypical feel and appearance of this cyst, the patient preferred to undergo excision. During excision, the lesion felt deep and fixed with retraction (Figure 2C). With intraoperative re-evaluation of the clinical scenario and location, the patient was sent for CT. The initial read noted clear maxillary and ethmoid sinuses, with no mention of an OCST. After discussing the clinical history and suspicion specifically for an OCST with the radiologist, the re-read showed notable inflammation and decay of the tooth adjacent to the area of interest. An OCST was diagnosed, and the patient was sent to an oral surgeon for excision after antibiotics were prescribed.

Practice Implications

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts commonly are misdiagnosed due to variations in clinical presentations resembling more common cutaneous diagnoses, nonspecific histopathologic findings, and lack of dental symptoms or concerns about dentition. Clinically, an OCST presents as a fixed, red, crusty, nontender nodule with intermittent draining. With palpation of the involved area, the clinician may feel a cord of tissue connecting the skin lesion intraorally.2,4 A clinician should have a high index of suspicion for an OCST when evaluating fixed lesions of the lower face, jawline, and neck due to the possibility of a dental origin,1 which is important because an OCST can have similar clinical findings to lesions such as congenital fistulas, pustules, cysts, osteomyelitis, foreign-body granulomas, pyogenic granulomas, syphilis, metastatic carcinomas, basal cell carcinomas, and SCCs.2,4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mohs, MMS, chemosurgery, odontogenic sinus, odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract, and dental sinus yielded only 2 OCSTs that were referred for MMS in the last 30 years, both of which were in the nasolabial fold/medial malar cheek.2,4 Histopathologic findings of an OCST are nonspecific; a mixed or granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, granulation tissue, and scarring can be seen.1 Pseudocarcinomatous/pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis can be seen and cause histologic misinterpretation for an SCC.2 Given that these findings are nonspecific without a clinical context, even with a histopathologic diagnosis of SCC or cyst, a clinical suspicion for an OCST should lead to an intraoral examination. Imaging can be ordered to look for an OCST in the area of interest. Although panoramic or periapical radiography with or without dental probes/radiopaque markers commonly have been used, more recent literature has suggested that CT may be superior to radiographs for making an OCST diagnosis.1,3 If imaging is not consistent with the clinically suspected OCST, we recommend directly contacting the radiologist to explain the clinical history and even refresh his/her suspicion for this diagnosis.

If a diagnosis of an OCST is made, oral antibiotics can be prescribed, though the use of antibiotics has been controversial. For severe odontogenic infections, typically beta-lactam antibiotics, cephalosporins, metronidazole, clindamycin, moxifloxacin, or erythromycin can be given for 7 days or until 3 days after symptoms have resolved.5 Although antibiotics can bring temporary resolution, it is imperative to treat the source of infection to prevent recurrence. It is crucial for these patients to be referred to an oral surgeon for evaluation and treatment of OCST by either a root canal or tooth extraction.

Final Thoughts

We present this pearl on the diagnosis and management of an OCST, also known as a dental sinus, to better assist clinicians in making this diagnosis. With an index of suspicion as well as intraoral and radiologic evaluations, a proper diagnosis may be rendered, potentially avoiding unnecessary cutaneous surgery. In addition, we highlight the importance of communication between the clinician and the radiologist to directly look for OCST in the area of concern and consider a re-read of the images when clinical suspicion does not correlate with the radiology report.

Clinical Challenge

An

Practice Gap

It is estimated that half of patients with an extraoral fistula are treated with multiple dermatologic surgical operations, radiotherapy, antibiotic therapy, and chemotherapy before the correct diagnosis is made.1 Thus, proper identification of these lesions is crucial for prognosis and treatment. The most common locations for OCSTs are the mandibular, submandibular, and cervical skin.1,2 Given these locations, patients with OCSTs commonly present to the dermatology office for evaluation. Education regarding the clinical presentation, histopathology, and proper evaluation and further referral for treatment is essential for dermatologists.

Tools and Technique for Diagnosis

We present 2 patients with OCSTs who were referred for cutaneous surgery for an SCC and epidermal cyst, but the proper diagnosis was rendered after an index of suspicion and clinicopathologic correlation led to additional testing and eventual referral for imaging.

Patient 1

A 68-year-old woman presented for Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) of a biopsy-proven SCC on the chin. The tumor cleared after 2 MMS stages (Figure 1A). Due to notable inflammation in each stage, the slides were sent to a pathologist who confirmed clear margins. Within 2 weeks of MMS, the wound began to dehisce (Figure 1B). The patient presented 4 months later with a crusted ulcerated nodule at the MMS site (Figure 1C). A biopsy showed likely recurrence of SCC. Upon presentation to the Mohs surgeon, the nodule felt fixed to the underlying jaw, and the patient was noted to have poor dentition. The patient was sent for computed tomography (CT), which showed focal thinning of the mandible, likely postsurgical, and clear maxillary sinuses. Due to the clinical appearance and anatomic location of the lesion, a request was made for a second read of the CT, specifically looking for an OCST at the prior surgical site. With this information, the radiologist noted an OCST extending from the mandible to the lesion, reported as a periapical lucency (representing a periapical abscess) at a mandibular tooth with a dental sinus draining into the soft tissues. The patient was started on antibiotics and referred to an oral surgeon for OCST excision.

Patient 2

A 62-year-old man presented with an inflamed subcutaneous nodule on the left anterior neck. A biopsy showed a ruptured cyst, and the patient was referred for excision. Clinical examination revealed a subcutaneous nodule fixed to the lower portion of the mandible (Figure 2A) that exhibited a rubbery retraction when pulled (Figure 2B). After a discussion about the atypical feel and appearance of this cyst, the patient preferred to undergo excision. During excision, the lesion felt deep and fixed with retraction (Figure 2C). With intraoperative re-evaluation of the clinical scenario and location, the patient was sent for CT. The initial read noted clear maxillary and ethmoid sinuses, with no mention of an OCST. After discussing the clinical history and suspicion specifically for an OCST with the radiologist, the re-read showed notable inflammation and decay of the tooth adjacent to the area of interest. An OCST was diagnosed, and the patient was sent to an oral surgeon for excision after antibiotics were prescribed.

Practice Implications

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts commonly are misdiagnosed due to variations in clinical presentations resembling more common cutaneous diagnoses, nonspecific histopathologic findings, and lack of dental symptoms or concerns about dentition. Clinically, an OCST presents as a fixed, red, crusty, nontender nodule with intermittent draining. With palpation of the involved area, the clinician may feel a cord of tissue connecting the skin lesion intraorally.2,4 A clinician should have a high index of suspicion for an OCST when evaluating fixed lesions of the lower face, jawline, and neck due to the possibility of a dental origin,1 which is important because an OCST can have similar clinical findings to lesions such as congenital fistulas, pustules, cysts, osteomyelitis, foreign-body granulomas, pyogenic granulomas, syphilis, metastatic carcinomas, basal cell carcinomas, and SCCs.2,4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mohs, MMS, chemosurgery, odontogenic sinus, odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract, and dental sinus yielded only 2 OCSTs that were referred for MMS in the last 30 years, both of which were in the nasolabial fold/medial malar cheek.2,4 Histopathologic findings of an OCST are nonspecific; a mixed or granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, granulation tissue, and scarring can be seen.1 Pseudocarcinomatous/pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis can be seen and cause histologic misinterpretation for an SCC.2 Given that these findings are nonspecific without a clinical context, even with a histopathologic diagnosis of SCC or cyst, a clinical suspicion for an OCST should lead to an intraoral examination. Imaging can be ordered to look for an OCST in the area of interest. Although panoramic or periapical radiography with or without dental probes/radiopaque markers commonly have been used, more recent literature has suggested that CT may be superior to radiographs for making an OCST diagnosis.1,3 If imaging is not consistent with the clinically suspected OCST, we recommend directly contacting the radiologist to explain the clinical history and even refresh his/her suspicion for this diagnosis.

If a diagnosis of an OCST is made, oral antibiotics can be prescribed, though the use of antibiotics has been controversial. For severe odontogenic infections, typically beta-lactam antibiotics, cephalosporins, metronidazole, clindamycin, moxifloxacin, or erythromycin can be given for 7 days or until 3 days after symptoms have resolved.5 Although antibiotics can bring temporary resolution, it is imperative to treat the source of infection to prevent recurrence. It is crucial for these patients to be referred to an oral surgeon for evaluation and treatment of OCST by either a root canal or tooth extraction.

Final Thoughts

We present this pearl on the diagnosis and management of an OCST, also known as a dental sinus, to better assist clinicians in making this diagnosis. With an index of suspicion as well as intraoral and radiologic evaluations, a proper diagnosis may be rendered, potentially avoiding unnecessary cutaneous surgery. In addition, we highlight the importance of communication between the clinician and the radiologist to directly look for OCST in the area of concern and consider a re-read of the images when clinical suspicion does not correlate with the radiology report.

- Bai J, Ji AP, Huang MW. Submental cutaneous sinus tract of mandibular second molar origin. Int Endod J. 2014;47:1185-1191.

- Plast Reconstr Surg.

- Gregoire C. How are odontogenic infections best managed? J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a37.

- Bodner L, Bar-Ziv J. Cutaneous sinus tract of dental origin—imaging with a dental CT software programme. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:311-313.

- Peermohamed S, Barber D, Kurwa H. Diagnostic challenges of cutaneous draining sinus tracts of odontogenic origin: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1525-1527.

- Bai J, Ji AP, Huang MW. Submental cutaneous sinus tract of mandibular second molar origin. Int Endod J. 2014;47:1185-1191.

- Plast Reconstr Surg.

- Gregoire C. How are odontogenic infections best managed? J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a37.

- Bodner L, Bar-Ziv J. Cutaneous sinus tract of dental origin—imaging with a dental CT software programme. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:311-313.

- Peermohamed S, Barber D, Kurwa H. Diagnostic challenges of cutaneous draining sinus tracts of odontogenic origin: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1525-1527.

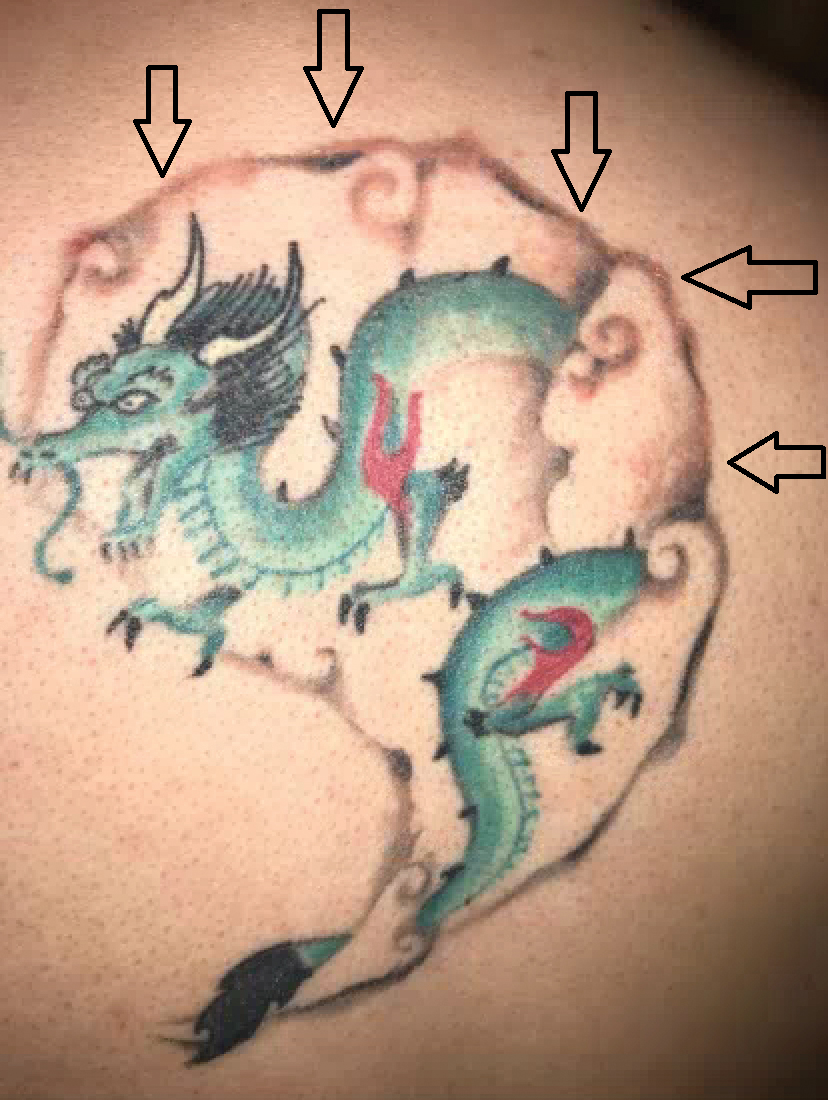

Erythematous Plaques on a Tattoo

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

A 29-year-old man presented with increased redness, dryness, and pruritus at the periphery of a tattoo (arrows) on the upper back of 4 months' duration. He was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus 8 months prior to presentation and had a history of cystic fibrosis, eczema, and genital molluscum contagiosum. Laboratory analysis 1 month prior revealed a CD4 count of 42 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500-1200 cells/mm3), and the viral load was 2388 copies/mL (reference range, 20-10,000,000 copies/mL). Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, eczematous, linear plaques along the dark gray lines of the tattoo. A 1.1.2 ×0.7.2 ×0.1-cm shave biopsy specimen was obtained. After the biopsy, tretinoin cream 0.1% and betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% were prescribed to be alternately applied on the tattoo lesions until resolution.

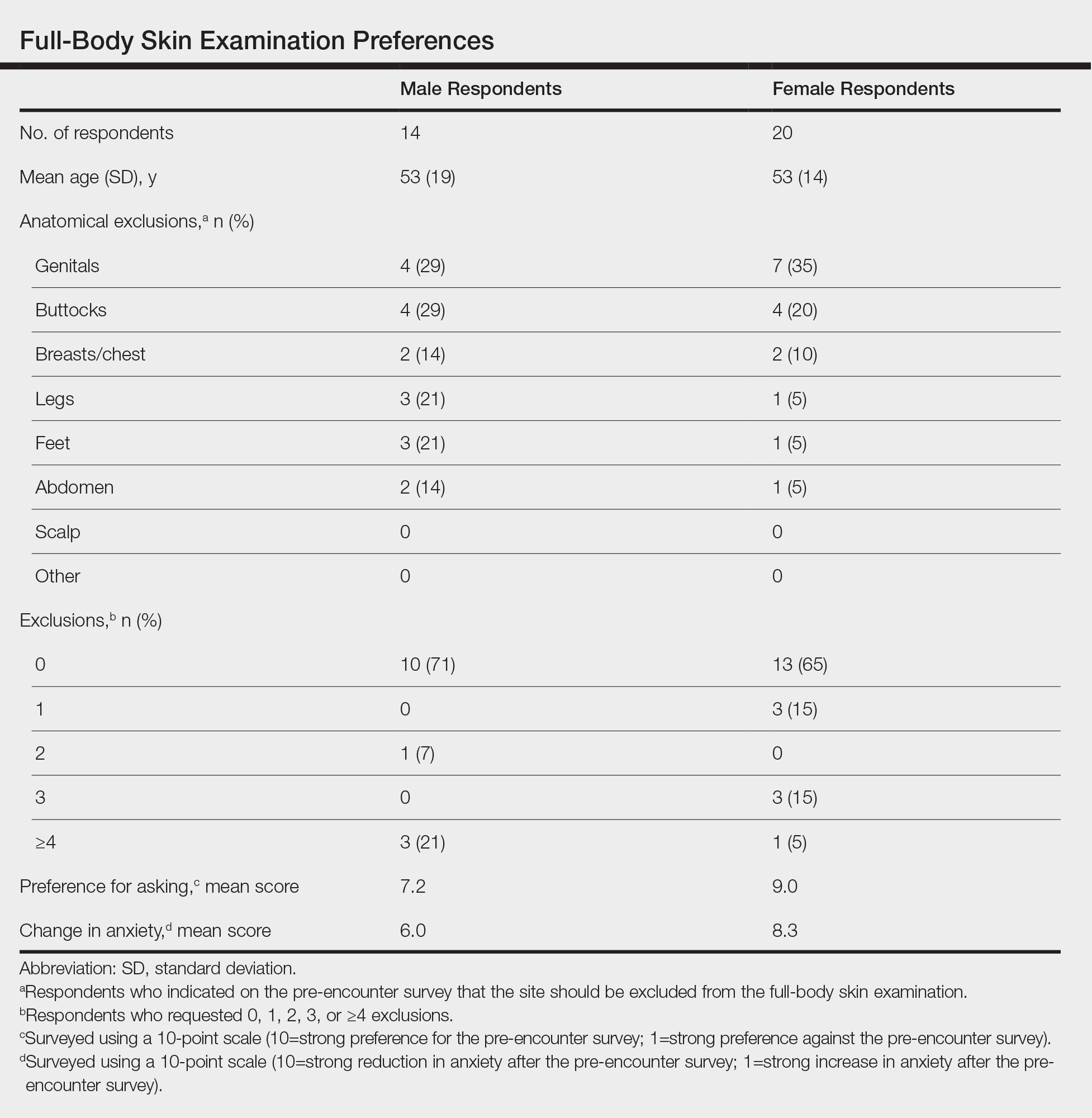

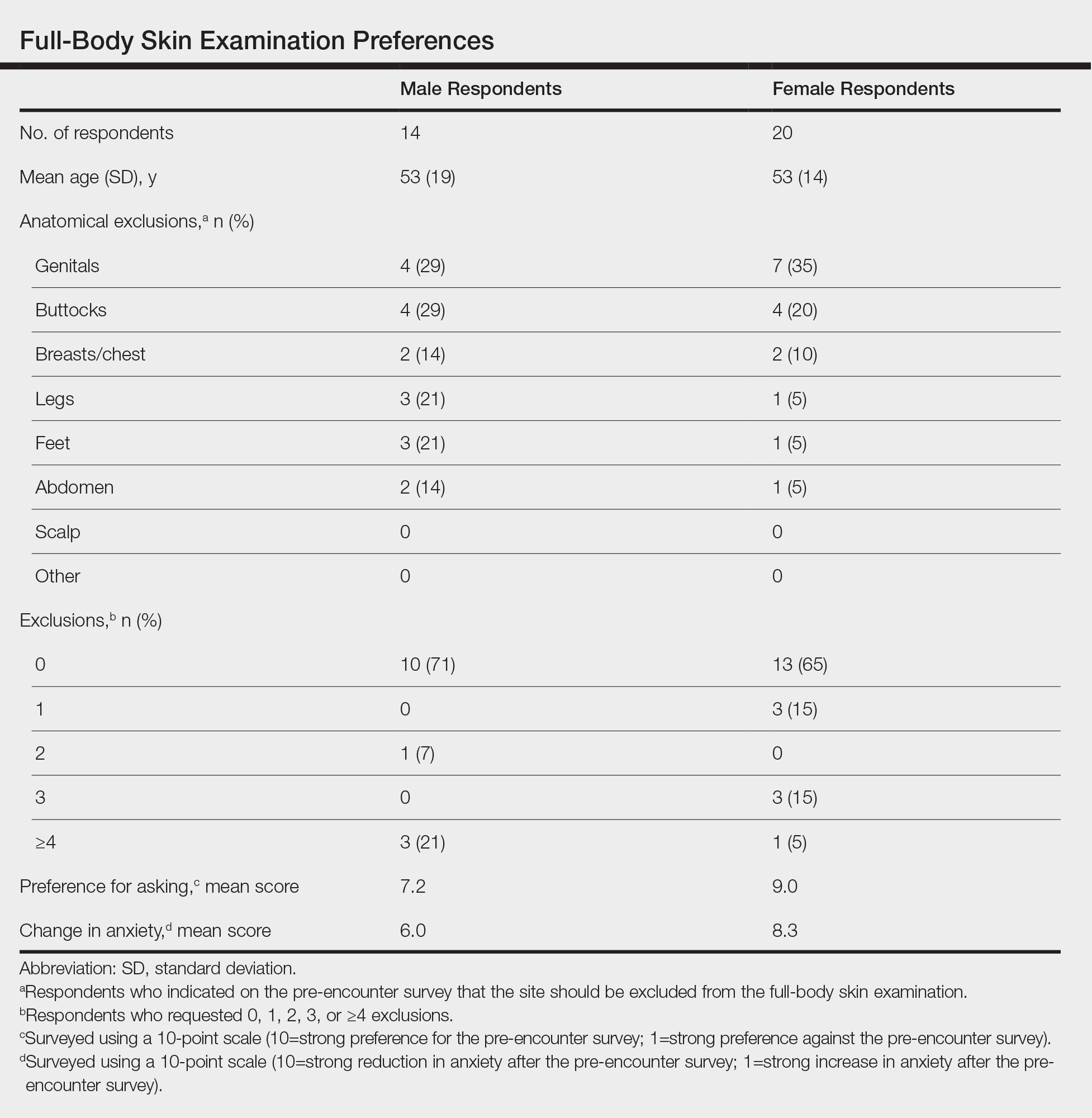

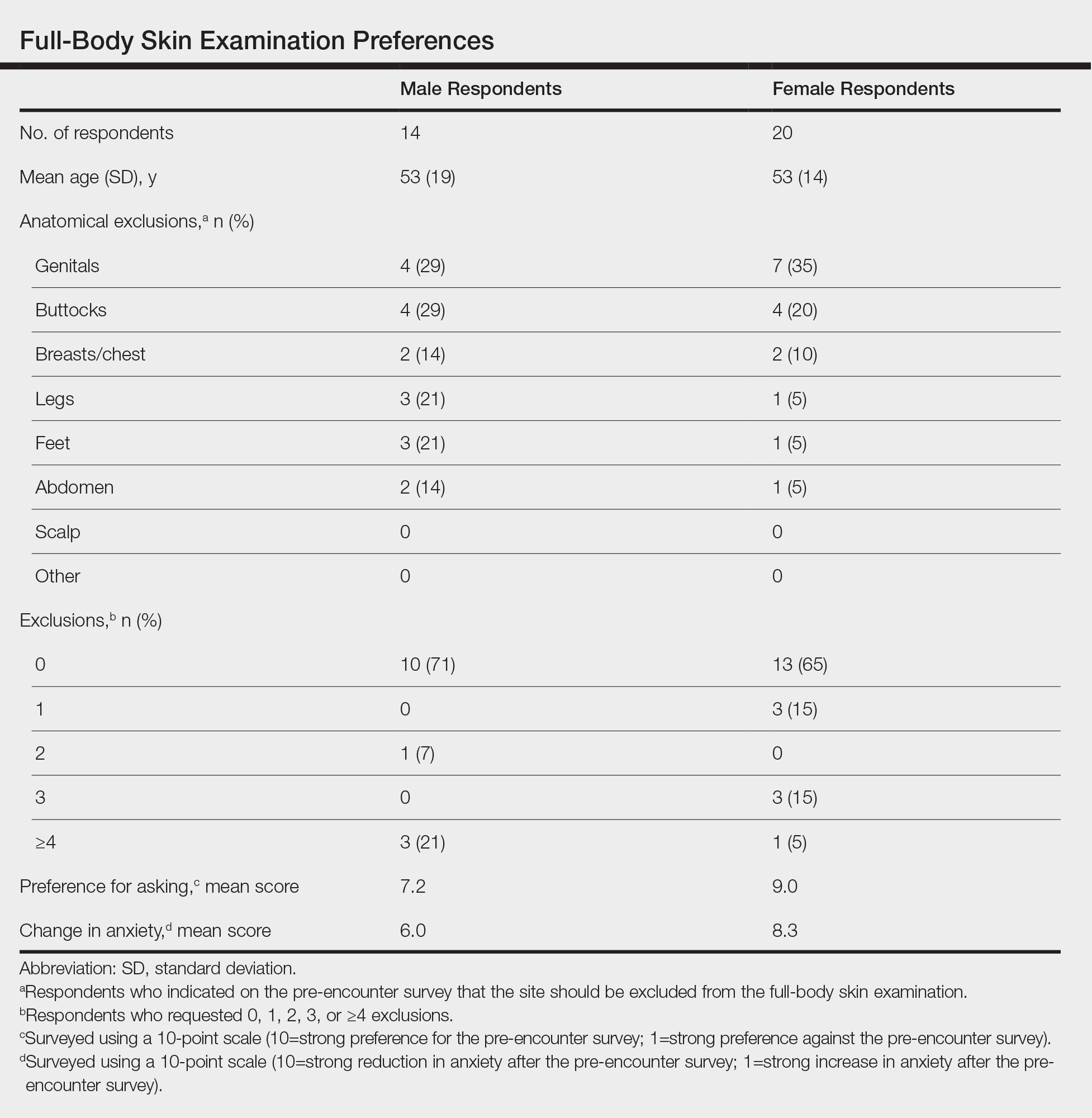

Patient Questionnaire to Reduce Anxiety Prior to Full-Body Skin Examination

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

Practice Points

- Full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an assessment that requires examination of sensitive body areas, any of which can be seen as intrusive by certain patients.

- A pre-encounter survey on the FBSE can offer an efficient means by which to determine patient preference and reduce visit-associated anxiety.

Tense Bullae on the Hands

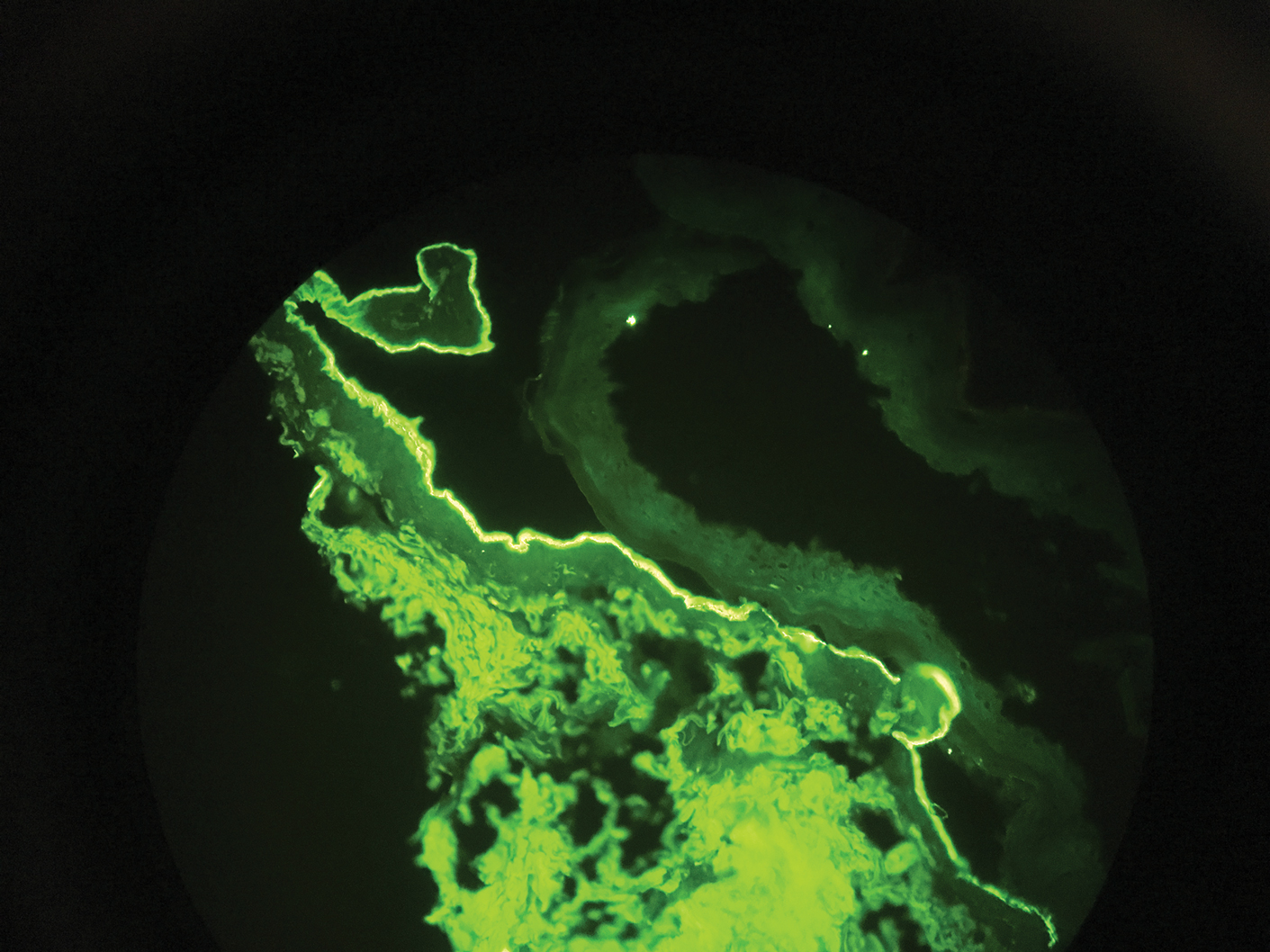

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

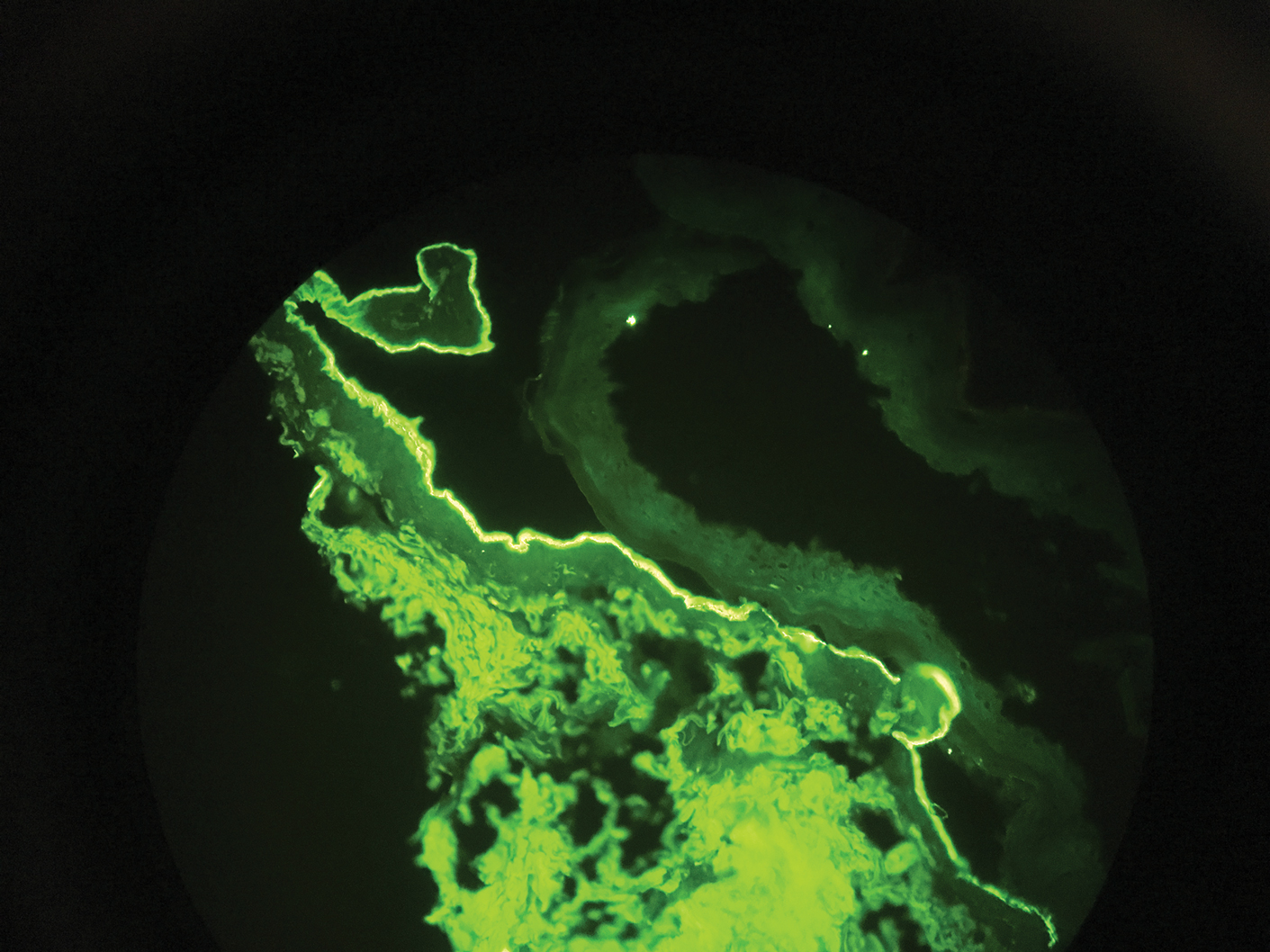

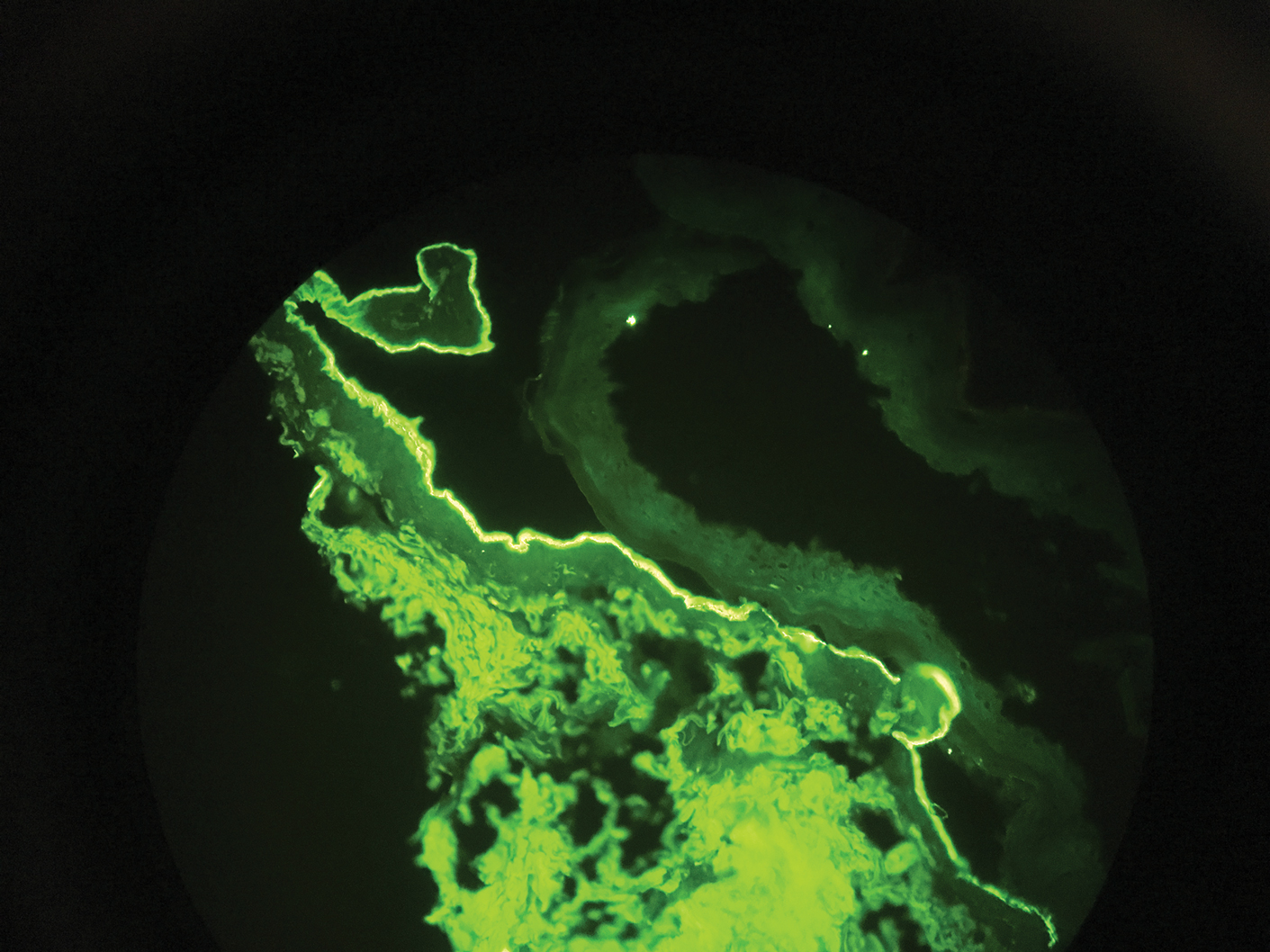

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

A 75-year-old man presented to our clinic with nonpainful, nonpruritic, tense bullae and erosions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and extensor surfaces of the elbows of 1 month's duration. The patient also had erythematous erosions and crusted papules on the left cheek and surrounding the left eye. He denied any new medications, history of liver or kidney disease, or history of hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus. There were no obvious exacerbating factors, including exposure to sunlight. Direct immunofluorescence using a salt-split preparation was performed on a biopsy of the perilesional skin.