User login

Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Hidradenitis Suppurativa Lesions Following Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with high morbidity rates. Symptoms typically develop between puberty and the third decade of life, affecting twice as many females as males, with an overall disease prevalence of 1% to 4%.1 The pathogenesis is theorized to be related to an immune response to follicular occlusion and rupture in genetically susceptible individuals.

Among the complications associated with HS, the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is 4.6-times more likely within HS lesions than in normal skin and typically is seen in the setting of long-standing disease, particularly in men with HS lesions located on the buttocks and genital region for more than 20 years.2 In 2015, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor adalimumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been associated with an increased risk for skin cancer in other clinical settings.3,4 We present a case of locally advanced SCC that developed in a patient with HS who was treated with adalimumab and infliximab (both TNF-α inhibitors), ultimately leading to the patient’s death.

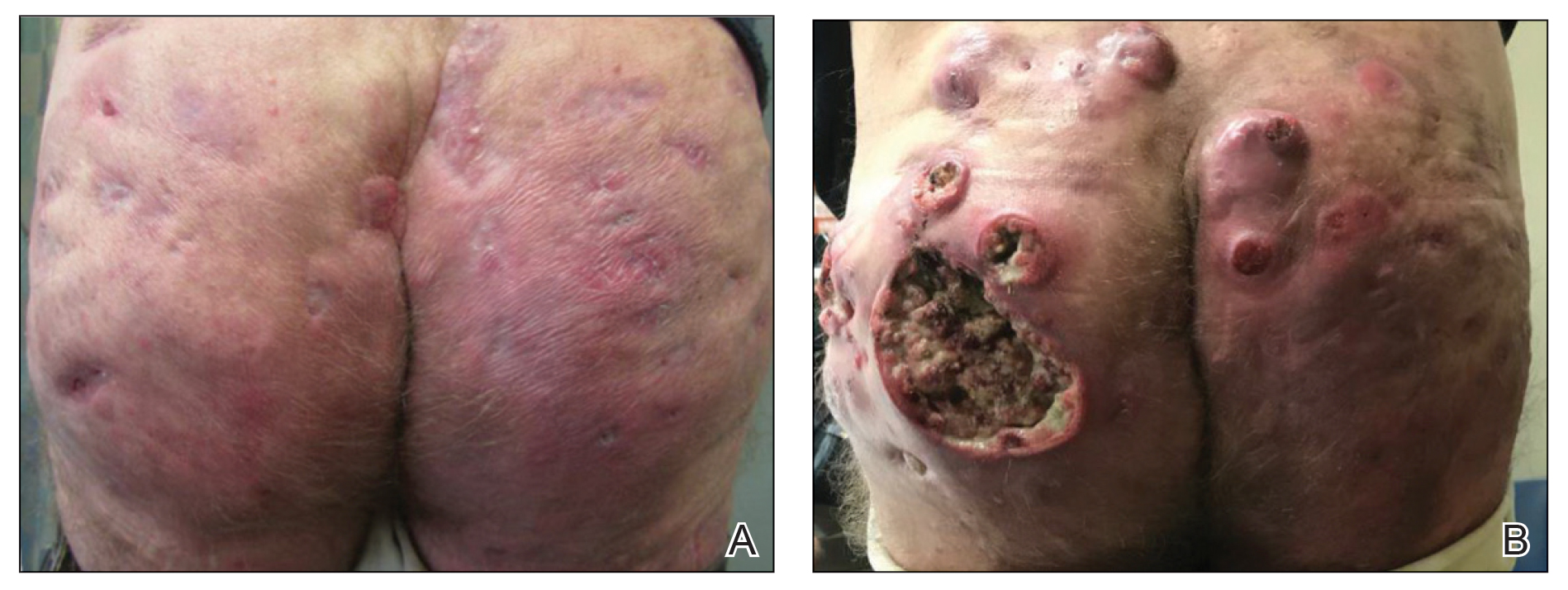

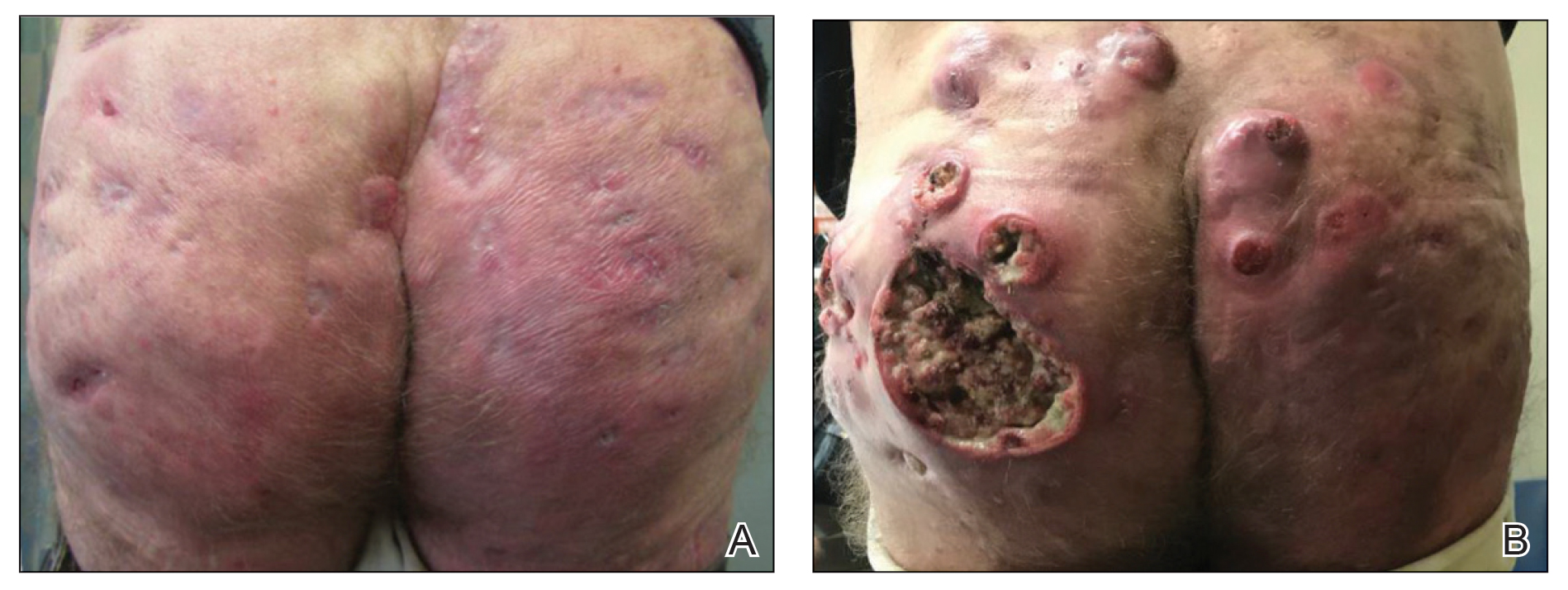

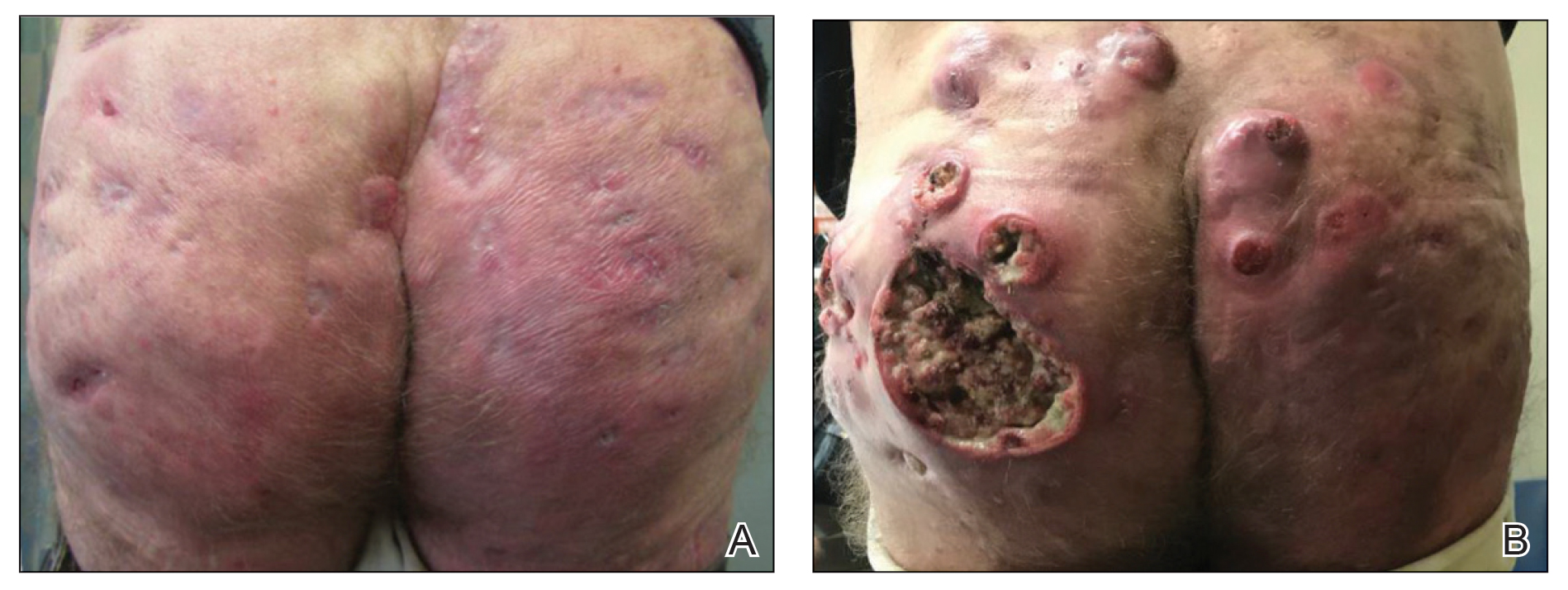

A 59-year-old man who smoked with a 40-year history of severe HS, who previously was lost to follow-up, presented to our dermatology clinic with lesions on the buttocks. Physical examination demonstrated confluent, indurated, boggy plaques; scattered sinus tracts with purulent drainage; scattered cystlike nodules; and tenderness to palpation consistent with Hurley stage III disease (Figure 1A). No involvement of the axillae or groin was noted. He was started on doxycycline and a prednisone taper with minimal improvement and subsequently was switched to adalimumab 3 months later. Adalimumab provided little relief and was discontinued; therapy was transitioned to infliximab 3 months later.

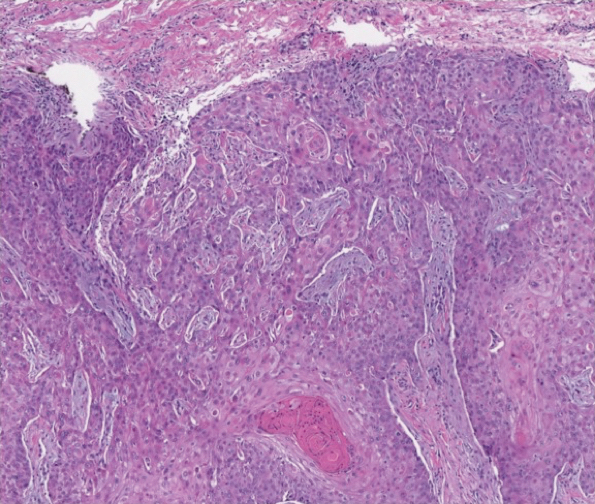

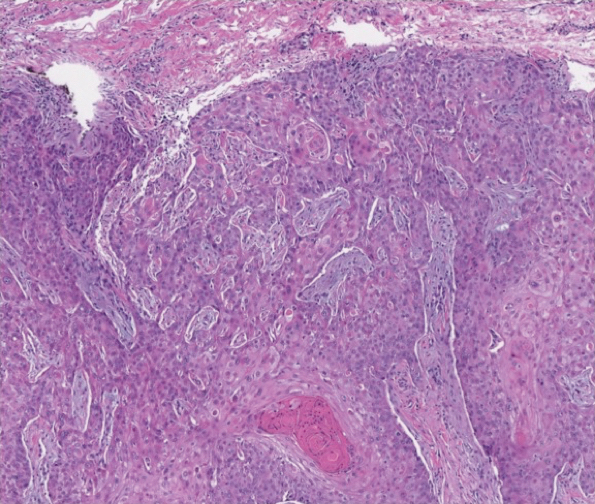

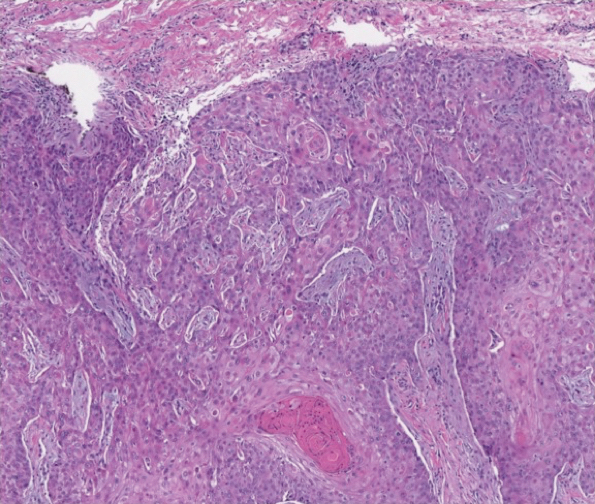

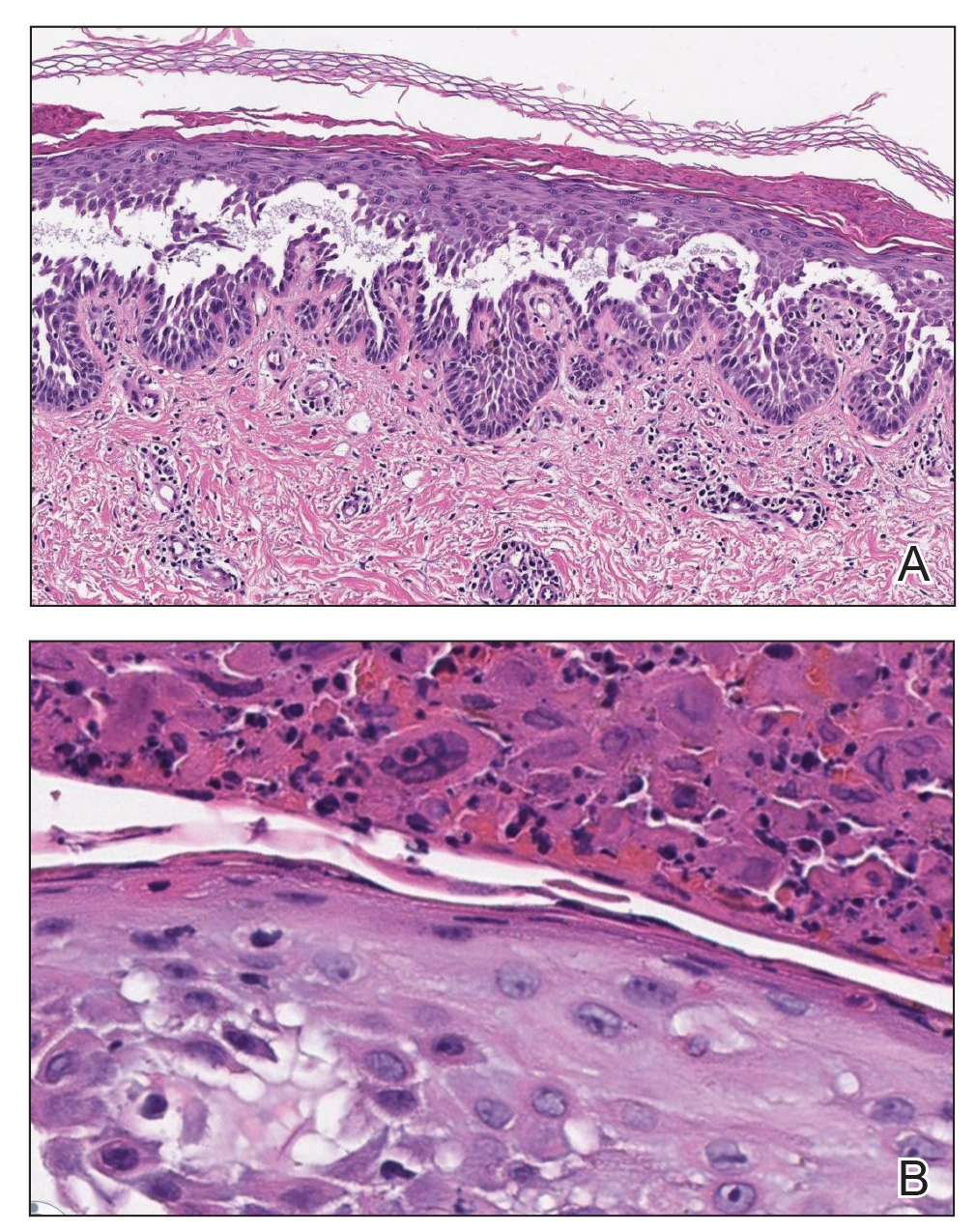

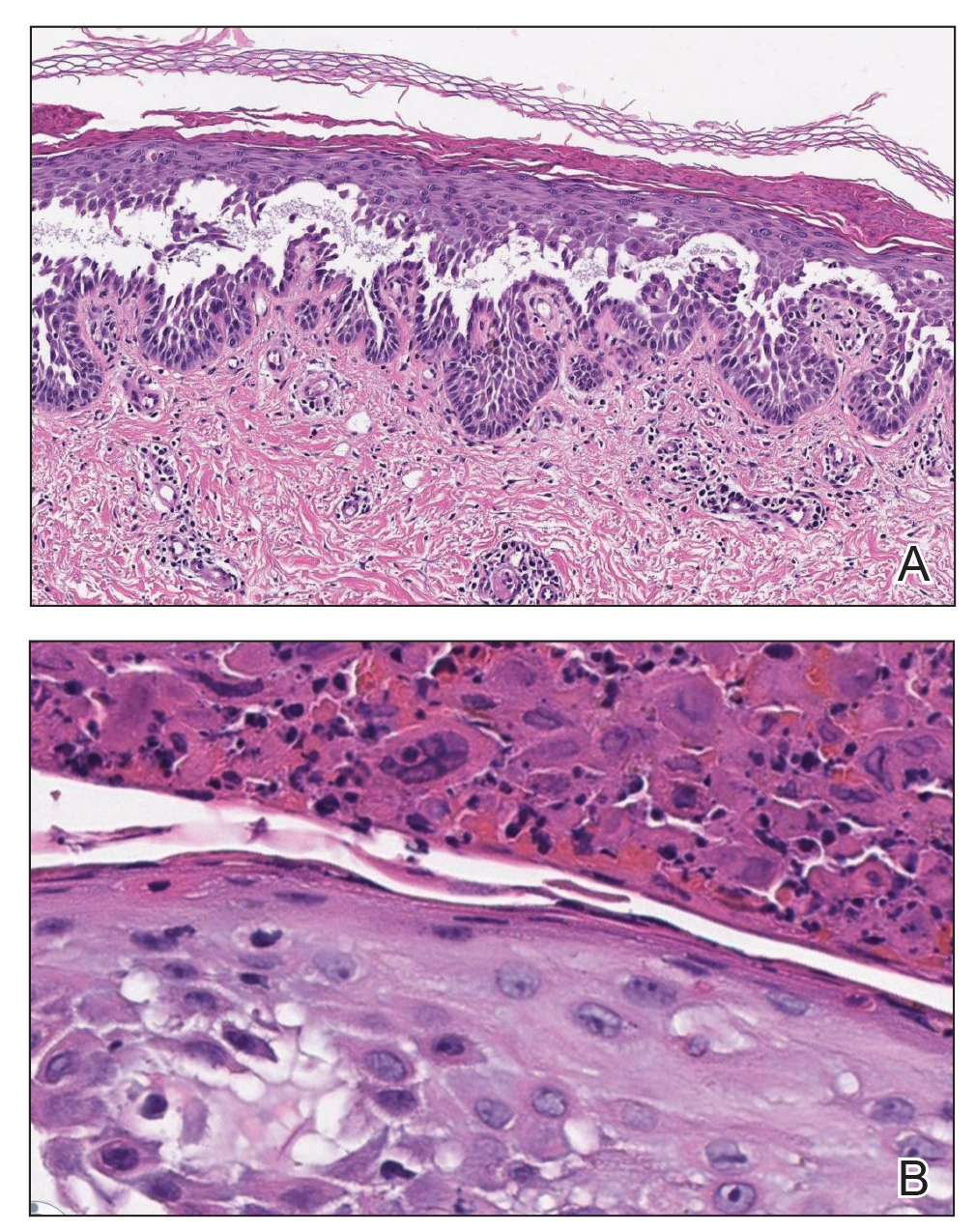

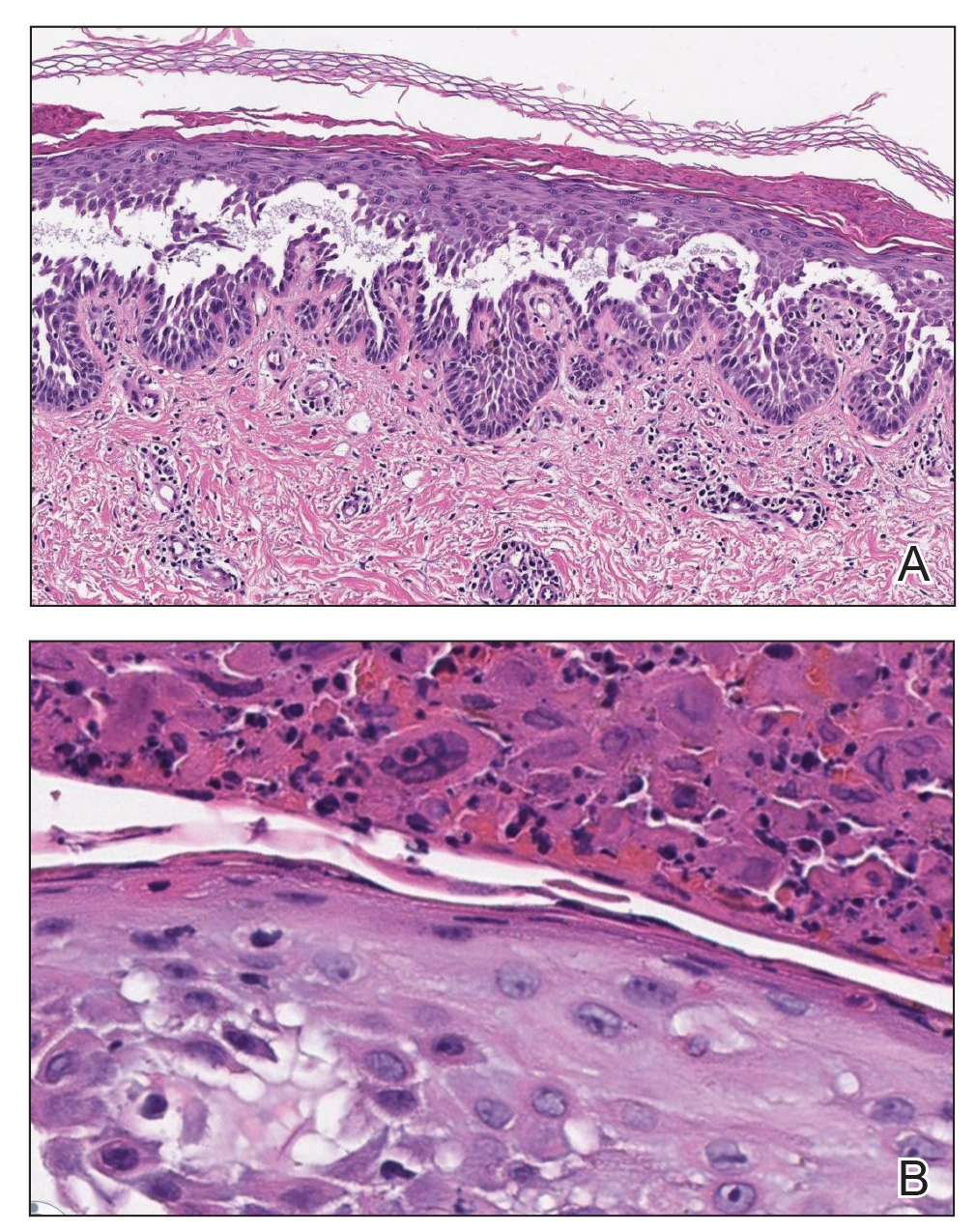

The patient returned to our clinic 3 months later with a severe flare and intractable pain after 4 infusions of infliximab. Physical examination showed a 7×5-cm deep malodorous ulcer with fibrinous exudate on the left buttock, several 2- to 3-cm shallow ulcers draining yellow exudate, and numerous fluctuant subcutaneous nodules on a background of scarring and sinus tracts. He was started again on doxycycline and a prednisone taper. At follow-up 2 weeks later, the largest ulcer had increased to 8 cm, and more indurated and tender subcutaneous nodules and scattered ulcerations developed (Figure 1B). Two punch biopsies of the left buttock revealed an invasive keratinizing carcinoma with no connection to the epidermis, consistent with SCC (Figure 2). Human papillomavirus (HPV) test results with probes for 37 HPV types—13 that were high risk (HPV-16, −18, −31, −33, −35, −39, −45, −51, −52, −56, −58, −59, −68)—were negative. Computerized tomography demonstrated diffuse thickening of the skin on the buttocks, inguinal adenopathy suspicious for nodal metastases, and no evidence of distant metastatic disease. Given the extent of the disease, surgical treatment was not an option, and he began receiving palliative radiotherapy. However, his health declined, and he developed aspiration pneumonia and hypotension requiring pressor support. He was transitioned to hospice care and died 3 months after presentation.

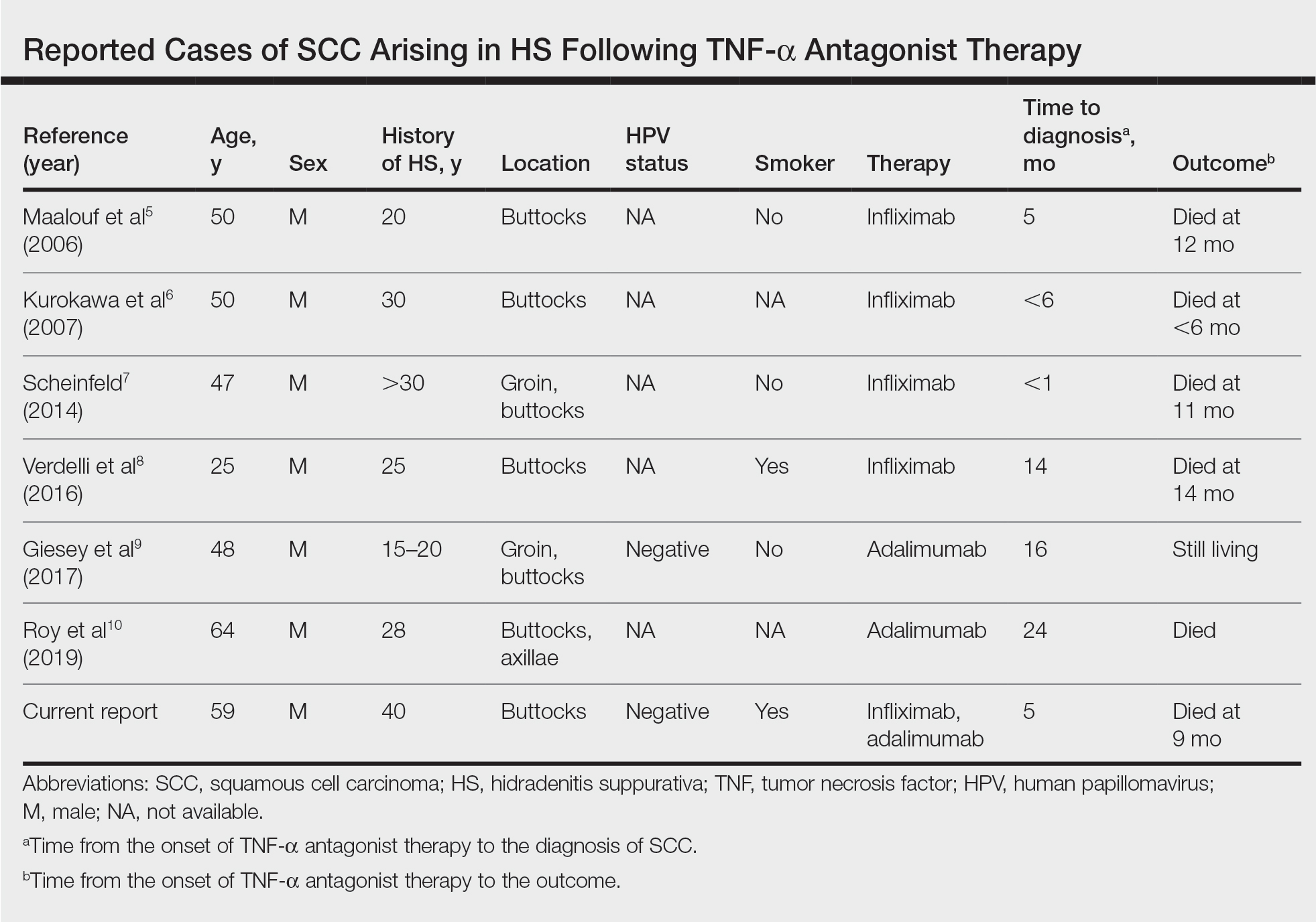

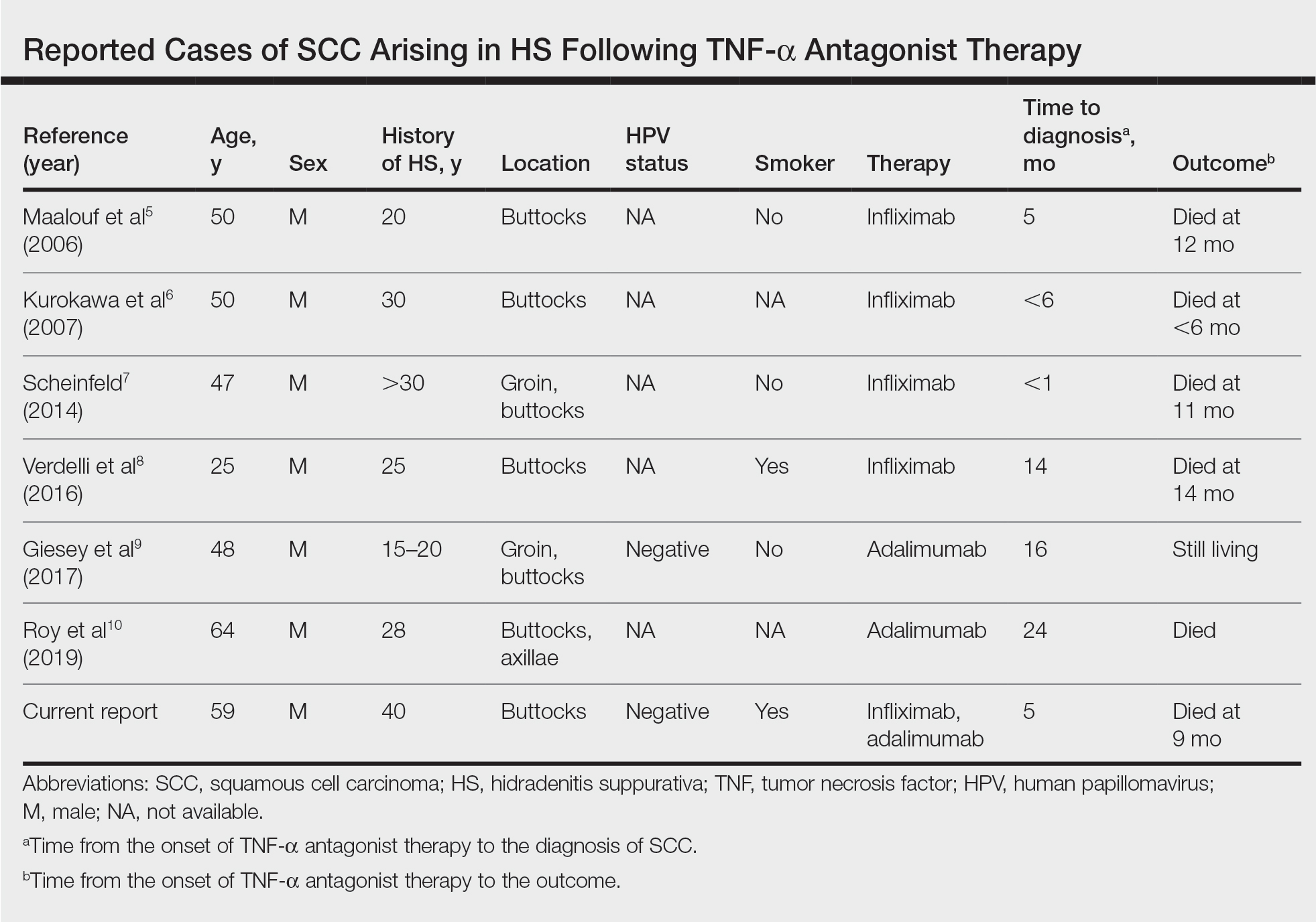

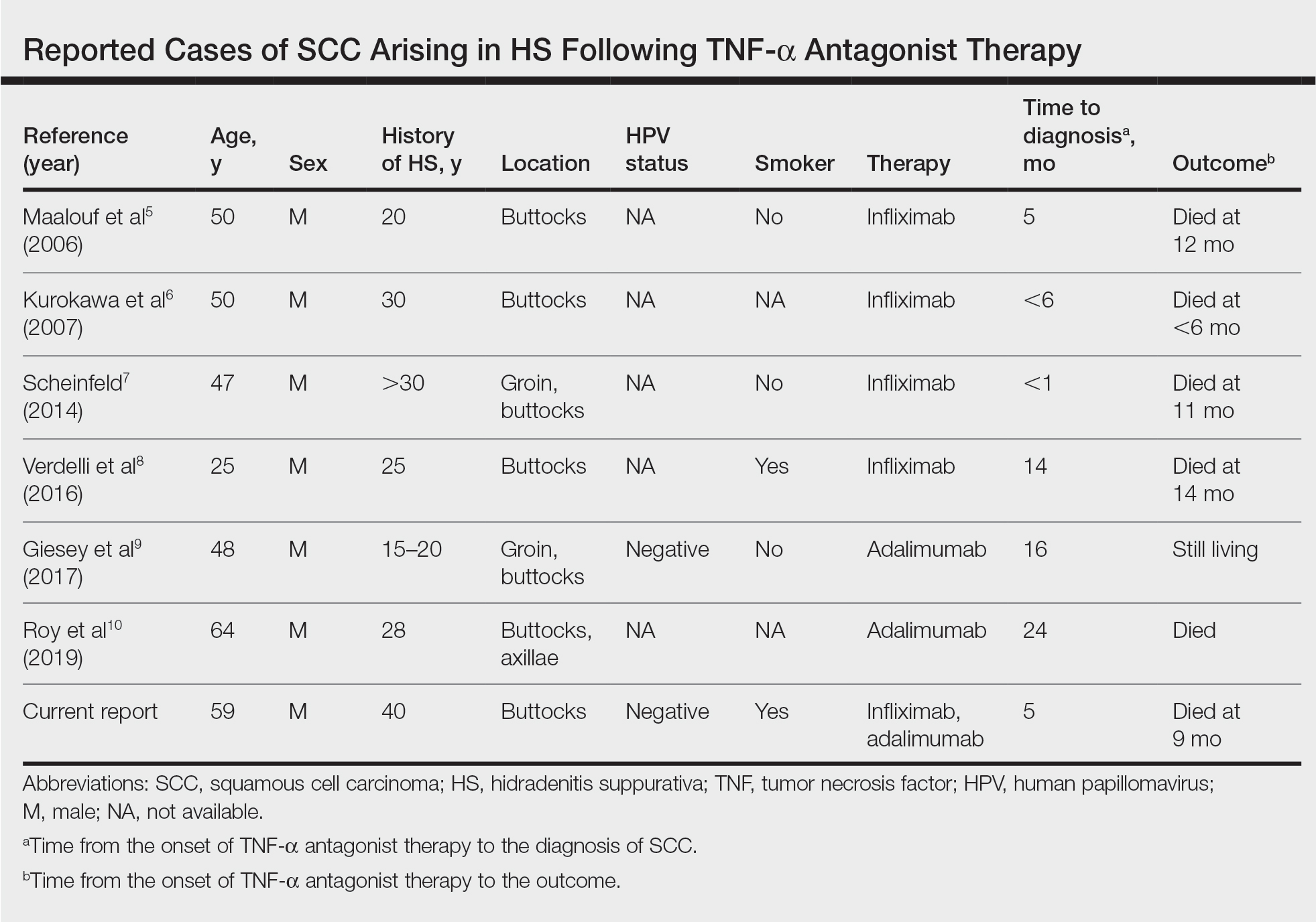

Tumor necrosis factor α antagonist treatment is being increasingly used to control HS but also may increase the risk for SCC development. We performed a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as Web of Science using the terms hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa and one of the following—tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—and squamous cell carcinoma or Marjolin ulcer. Seven cases of SCC arising in an HS patient treated with a TNF-α inhibitor have been reported (Table).5-10 Four cases were associated with infliximab use, 2 with adalimumab, and our case occurred after both adalimumab and infliximab treatment. All individuals were men with severe, long-standing disease of the anogenital region. In addition to smoking, HPV-16 positivity also has been reported as a risk factor for developing SCC in the setting of HS.11 In our patient, however, HPV testing did not cover all HPV strains, but several high-risk strains, including HPV-16, were negative.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is caused by an immune response to ruptured follicles and TNF-α antagonists are useful in suppressing this response; however, immunosuppression can lead to an increased susceptibility to malignancy, especially in SCC. It is unclear whether the use of infliximab or adalimumab is causal, additive, or a confounder in the development of SCC in patients with severe HS. It is possible that these agents increase the rapidity of the development of SCC in already-susceptible patients. Although TNF-α antagonists can be an effective therapeutic option for patients with moderate to severe HS, the potential risk for contributing to skin cancer development should raise provider suspicion in high-risk patients. Given the findings in this report, it may be suitable for providers to consider a biopsy prior to initiating TNF-α therapy in men older than 20 years with moderate to severe HS of the groin or buttocks, in addition to more frequent monitoring and a lower threshold to biopsy lesions with rapid growth or ulceration.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561; quiz 562-533.

- Lapins J, Ye W, Nyren O, et al. Incidence of cancer among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:730-734.

- Askling J, Fahrbach K, Nordstrom B, et al. Cancer risk with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab using patient level data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:119-130.

- Mariette X, Matucci-Cerinic M, Pavelka K, et al. Malignancies associated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in registries and prospective observational studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1895-1904.

- Maalouf E, Faye O, Poli F, et al. Fatal epidermoid carcinoma in hidradenitis suppurativa following treatment with infliximab. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133(5 pt 1):473-474.

- Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Yamanaka K, et al. Cytokeratin expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:675-678.

- Scheinfeld N. A case of a patient with stage III familial hidradenitis suppurativa treated with 3 courses of infliximab and died of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(3).

- Verdelli A, Antiga E, Bonciani D, et al. A fatal case of hidradenitis suppurativa associated with sepsis and squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E52-E53.

- Giesey R, Delost GR, Honaker J, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in a patient treated with adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:489-491.

- Roy C, Roy S, Ghazawi F, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma arising in hidradenitis suppurativa: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847359.

- Lavogiez C, Delaporte E, Darras-Vercambre S, et al. Clinicopathological study of 13 cases of squamous cell carcinoma complicating hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2010;220:147-153.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with high morbidity rates. Symptoms typically develop between puberty and the third decade of life, affecting twice as many females as males, with an overall disease prevalence of 1% to 4%.1 The pathogenesis is theorized to be related to an immune response to follicular occlusion and rupture in genetically susceptible individuals.

Among the complications associated with HS, the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is 4.6-times more likely within HS lesions than in normal skin and typically is seen in the setting of long-standing disease, particularly in men with HS lesions located on the buttocks and genital region for more than 20 years.2 In 2015, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor adalimumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been associated with an increased risk for skin cancer in other clinical settings.3,4 We present a case of locally advanced SCC that developed in a patient with HS who was treated with adalimumab and infliximab (both TNF-α inhibitors), ultimately leading to the patient’s death.

A 59-year-old man who smoked with a 40-year history of severe HS, who previously was lost to follow-up, presented to our dermatology clinic with lesions on the buttocks. Physical examination demonstrated confluent, indurated, boggy plaques; scattered sinus tracts with purulent drainage; scattered cystlike nodules; and tenderness to palpation consistent with Hurley stage III disease (Figure 1A). No involvement of the axillae or groin was noted. He was started on doxycycline and a prednisone taper with minimal improvement and subsequently was switched to adalimumab 3 months later. Adalimumab provided little relief and was discontinued; therapy was transitioned to infliximab 3 months later.

The patient returned to our clinic 3 months later with a severe flare and intractable pain after 4 infusions of infliximab. Physical examination showed a 7×5-cm deep malodorous ulcer with fibrinous exudate on the left buttock, several 2- to 3-cm shallow ulcers draining yellow exudate, and numerous fluctuant subcutaneous nodules on a background of scarring and sinus tracts. He was started again on doxycycline and a prednisone taper. At follow-up 2 weeks later, the largest ulcer had increased to 8 cm, and more indurated and tender subcutaneous nodules and scattered ulcerations developed (Figure 1B). Two punch biopsies of the left buttock revealed an invasive keratinizing carcinoma with no connection to the epidermis, consistent with SCC (Figure 2). Human papillomavirus (HPV) test results with probes for 37 HPV types—13 that were high risk (HPV-16, −18, −31, −33, −35, −39, −45, −51, −52, −56, −58, −59, −68)—were negative. Computerized tomography demonstrated diffuse thickening of the skin on the buttocks, inguinal adenopathy suspicious for nodal metastases, and no evidence of distant metastatic disease. Given the extent of the disease, surgical treatment was not an option, and he began receiving palliative radiotherapy. However, his health declined, and he developed aspiration pneumonia and hypotension requiring pressor support. He was transitioned to hospice care and died 3 months after presentation.

Tumor necrosis factor α antagonist treatment is being increasingly used to control HS but also may increase the risk for SCC development. We performed a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as Web of Science using the terms hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa and one of the following—tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—and squamous cell carcinoma or Marjolin ulcer. Seven cases of SCC arising in an HS patient treated with a TNF-α inhibitor have been reported (Table).5-10 Four cases were associated with infliximab use, 2 with adalimumab, and our case occurred after both adalimumab and infliximab treatment. All individuals were men with severe, long-standing disease of the anogenital region. In addition to smoking, HPV-16 positivity also has been reported as a risk factor for developing SCC in the setting of HS.11 In our patient, however, HPV testing did not cover all HPV strains, but several high-risk strains, including HPV-16, were negative.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is caused by an immune response to ruptured follicles and TNF-α antagonists are useful in suppressing this response; however, immunosuppression can lead to an increased susceptibility to malignancy, especially in SCC. It is unclear whether the use of infliximab or adalimumab is causal, additive, or a confounder in the development of SCC in patients with severe HS. It is possible that these agents increase the rapidity of the development of SCC in already-susceptible patients. Although TNF-α antagonists can be an effective therapeutic option for patients with moderate to severe HS, the potential risk for contributing to skin cancer development should raise provider suspicion in high-risk patients. Given the findings in this report, it may be suitable for providers to consider a biopsy prior to initiating TNF-α therapy in men older than 20 years with moderate to severe HS of the groin or buttocks, in addition to more frequent monitoring and a lower threshold to biopsy lesions with rapid growth or ulceration.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with high morbidity rates. Symptoms typically develop between puberty and the third decade of life, affecting twice as many females as males, with an overall disease prevalence of 1% to 4%.1 The pathogenesis is theorized to be related to an immune response to follicular occlusion and rupture in genetically susceptible individuals.

Among the complications associated with HS, the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is 4.6-times more likely within HS lesions than in normal skin and typically is seen in the setting of long-standing disease, particularly in men with HS lesions located on the buttocks and genital region for more than 20 years.2 In 2015, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor adalimumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been associated with an increased risk for skin cancer in other clinical settings.3,4 We present a case of locally advanced SCC that developed in a patient with HS who was treated with adalimumab and infliximab (both TNF-α inhibitors), ultimately leading to the patient’s death.

A 59-year-old man who smoked with a 40-year history of severe HS, who previously was lost to follow-up, presented to our dermatology clinic with lesions on the buttocks. Physical examination demonstrated confluent, indurated, boggy plaques; scattered sinus tracts with purulent drainage; scattered cystlike nodules; and tenderness to palpation consistent with Hurley stage III disease (Figure 1A). No involvement of the axillae or groin was noted. He was started on doxycycline and a prednisone taper with minimal improvement and subsequently was switched to adalimumab 3 months later. Adalimumab provided little relief and was discontinued; therapy was transitioned to infliximab 3 months later.

The patient returned to our clinic 3 months later with a severe flare and intractable pain after 4 infusions of infliximab. Physical examination showed a 7×5-cm deep malodorous ulcer with fibrinous exudate on the left buttock, several 2- to 3-cm shallow ulcers draining yellow exudate, and numerous fluctuant subcutaneous nodules on a background of scarring and sinus tracts. He was started again on doxycycline and a prednisone taper. At follow-up 2 weeks later, the largest ulcer had increased to 8 cm, and more indurated and tender subcutaneous nodules and scattered ulcerations developed (Figure 1B). Two punch biopsies of the left buttock revealed an invasive keratinizing carcinoma with no connection to the epidermis, consistent with SCC (Figure 2). Human papillomavirus (HPV) test results with probes for 37 HPV types—13 that were high risk (HPV-16, −18, −31, −33, −35, −39, −45, −51, −52, −56, −58, −59, −68)—were negative. Computerized tomography demonstrated diffuse thickening of the skin on the buttocks, inguinal adenopathy suspicious for nodal metastases, and no evidence of distant metastatic disease. Given the extent of the disease, surgical treatment was not an option, and he began receiving palliative radiotherapy. However, his health declined, and he developed aspiration pneumonia and hypotension requiring pressor support. He was transitioned to hospice care and died 3 months after presentation.

Tumor necrosis factor α antagonist treatment is being increasingly used to control HS but also may increase the risk for SCC development. We performed a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as Web of Science using the terms hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa and one of the following—tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—and squamous cell carcinoma or Marjolin ulcer. Seven cases of SCC arising in an HS patient treated with a TNF-α inhibitor have been reported (Table).5-10 Four cases were associated with infliximab use, 2 with adalimumab, and our case occurred after both adalimumab and infliximab treatment. All individuals were men with severe, long-standing disease of the anogenital region. In addition to smoking, HPV-16 positivity also has been reported as a risk factor for developing SCC in the setting of HS.11 In our patient, however, HPV testing did not cover all HPV strains, but several high-risk strains, including HPV-16, were negative.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is caused by an immune response to ruptured follicles and TNF-α antagonists are useful in suppressing this response; however, immunosuppression can lead to an increased susceptibility to malignancy, especially in SCC. It is unclear whether the use of infliximab or adalimumab is causal, additive, or a confounder in the development of SCC in patients with severe HS. It is possible that these agents increase the rapidity of the development of SCC in already-susceptible patients. Although TNF-α antagonists can be an effective therapeutic option for patients with moderate to severe HS, the potential risk for contributing to skin cancer development should raise provider suspicion in high-risk patients. Given the findings in this report, it may be suitable for providers to consider a biopsy prior to initiating TNF-α therapy in men older than 20 years with moderate to severe HS of the groin or buttocks, in addition to more frequent monitoring and a lower threshold to biopsy lesions with rapid growth or ulceration.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561; quiz 562-533.

- Lapins J, Ye W, Nyren O, et al. Incidence of cancer among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:730-734.

- Askling J, Fahrbach K, Nordstrom B, et al. Cancer risk with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab using patient level data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:119-130.

- Mariette X, Matucci-Cerinic M, Pavelka K, et al. Malignancies associated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in registries and prospective observational studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1895-1904.

- Maalouf E, Faye O, Poli F, et al. Fatal epidermoid carcinoma in hidradenitis suppurativa following treatment with infliximab. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133(5 pt 1):473-474.

- Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Yamanaka K, et al. Cytokeratin expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:675-678.

- Scheinfeld N. A case of a patient with stage III familial hidradenitis suppurativa treated with 3 courses of infliximab and died of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(3).

- Verdelli A, Antiga E, Bonciani D, et al. A fatal case of hidradenitis suppurativa associated with sepsis and squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E52-E53.

- Giesey R, Delost GR, Honaker J, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in a patient treated with adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:489-491.

- Roy C, Roy S, Ghazawi F, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma arising in hidradenitis suppurativa: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847359.

- Lavogiez C, Delaporte E, Darras-Vercambre S, et al. Clinicopathological study of 13 cases of squamous cell carcinoma complicating hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2010;220:147-153.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561; quiz 562-533.

- Lapins J, Ye W, Nyren O, et al. Incidence of cancer among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:730-734.

- Askling J, Fahrbach K, Nordstrom B, et al. Cancer risk with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab using patient level data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:119-130.

- Mariette X, Matucci-Cerinic M, Pavelka K, et al. Malignancies associated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in registries and prospective observational studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1895-1904.

- Maalouf E, Faye O, Poli F, et al. Fatal epidermoid carcinoma in hidradenitis suppurativa following treatment with infliximab. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133(5 pt 1):473-474.

- Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Yamanaka K, et al. Cytokeratin expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:675-678.

- Scheinfeld N. A case of a patient with stage III familial hidradenitis suppurativa treated with 3 courses of infliximab and died of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(3).

- Verdelli A, Antiga E, Bonciani D, et al. A fatal case of hidradenitis suppurativa associated with sepsis and squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E52-E53.

- Giesey R, Delost GR, Honaker J, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in a patient treated with adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:489-491.

- Roy C, Roy S, Ghazawi F, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma arising in hidradenitis suppurativa: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847359.

- Lavogiez C, Delaporte E, Darras-Vercambre S, et al. Clinicopathological study of 13 cases of squamous cell carcinoma complicating hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2010;220:147-153.

Practice Points

- Consider biopsy of representative lesions in men older than 20 years with moderate to severe disease of the groin and/or buttocks prior to initiation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.

- Consider more frequent clinical monitoring with a decrease in threshold to perform biopsy of any new or ulcerating lesions.

Painful Hemorrhagic Erosions

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption (Eczema Herpeticum)

Polymerase chain reaction confirmed presence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, and the patient was started on intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours). Diagnosis was further supported by histopathologic examination with confirmatory immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). The patient's anemia and thrombocytopenia also were attributed to widespread HSV infection.

Approximately 8 hours after the patient was started on acyclovir, he developed increasing tremors, confusion, and impaired speech. Lumbar puncture confirmed the presence of HSV-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid. Despite ongoing intravenous antiviral therapy, he required intubation 6 days after hospitalization due to impaired mental status and myoclonic jerking. He remained intubated, unresponsive, and in critical condition for 9 days before he gradually began to demonstrate cognitive recovery. He subsequently was weaned off the ventilator, his mental status returned to normal, and his skin rash slowly resolved (Figure 2).

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus, is a rare autosomal-dominant condition first described by Howard and Hugh Hailey in 1939.1 It is a chronic blistering process characterized by epidermal fragility, often manifesting as macerated fissured erosions in areas exposed to heat and friction (eg, axillae, groin). Hailey-Hailey disease results from a defective calcium transporter (ATP2C1 gene), leading to impaired keratinocyte adhesion.2

Eczema herpeticum refers to the dissemination of herpes infection to areas of compromised skin barrier. Although originally used to describe HSV infection in patients with atopic dermatitis, eczema herpeticum has been described in various conditions that affect the skin barrier function, including Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mycosis fungoides, among others.3 When applied to skin conditions other than atopic dermatitis, it sometimes is referred to as Kaposi varicelliform eruption.2

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly is complicated by a bacterial or fungal infection, including impetigo, tinea, or candidiasis. The first case of HHD complicated by HSV infection was reported in 1973.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms benign familial pemphigus AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND eczema herpeticum, Hailey-Hailey AND Kaposi varicelliform eruption, and Hailey-Hailey herpeticum revealed 15 cases of HHD complicated by eczema herpeticum.4-6 Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a rare and life-threatening complication of eczema herpeticum.7,8 We report a case of HSV encephalitis resulting from eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD.

The clinical differential includes a flare of the patient's known HHD, secondary bacterial or fungal infection, or a superimposed viral infection (eg, HSV, zoster). Histologic evidence of herpetic infection would be absent in an uncomplicated flare of HHD. Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection that can present in 2 clinical forms: a vesiculopustular type and less commonly a bullous type. It is caused by Staphylococcus aureus in most cases. In multiple myeloma with cutaneous dissemination, a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells would be evident. Lastly, tinea corporis is caused by dermatophytes that can be seen on hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The diagnosis of eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD should be considered in patients who present with grouped vesicles or hemorrhagic or punched-out erosions in areas of pre-existing HHD. The diagnosis can be confirmed by Tzanck smear, viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, or histopathology (with or without immunohistochemistry).1,2,6 When eczema herpeticum is suspected, prompt antiviral administration is imperative to limit life-threatening systemic spread.

- Hailey J, Hailey H. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:679-685.

- de Aquino Paulo Filho T, deFreitas YK, da Nóbrega MT, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease associated with herpetic eczema-the value of the Tzanck smear test. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:29-31.

- Flint ID, Spencer DM, Wilkin JK. Eczema herpeticum in association with familial benign chronic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2, pt 1):257-259.

- Leppard B, Delaney TJ, Sanderson KV. Chronic benign familial pemphigus. induction of lesions by Herpesvirus hominis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:609-613.

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zamperetti M, Pichler M, Perino F, et al. Ein fall von morbus Hailey-Hailey in verbindung mit einem eczema herpeticatum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1035-1038.

- Ingrand D, Briquet I, Babinet JM, et al. Eczema herpeticum of the child. an unusual manifestation of herpes simplex virus infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1985;24:660-663.

- Finlow C, Thomas J. Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:36-39.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption (Eczema Herpeticum)

Polymerase chain reaction confirmed presence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, and the patient was started on intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours). Diagnosis was further supported by histopathologic examination with confirmatory immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). The patient's anemia and thrombocytopenia also were attributed to widespread HSV infection.

Approximately 8 hours after the patient was started on acyclovir, he developed increasing tremors, confusion, and impaired speech. Lumbar puncture confirmed the presence of HSV-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid. Despite ongoing intravenous antiviral therapy, he required intubation 6 days after hospitalization due to impaired mental status and myoclonic jerking. He remained intubated, unresponsive, and in critical condition for 9 days before he gradually began to demonstrate cognitive recovery. He subsequently was weaned off the ventilator, his mental status returned to normal, and his skin rash slowly resolved (Figure 2).

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus, is a rare autosomal-dominant condition first described by Howard and Hugh Hailey in 1939.1 It is a chronic blistering process characterized by epidermal fragility, often manifesting as macerated fissured erosions in areas exposed to heat and friction (eg, axillae, groin). Hailey-Hailey disease results from a defective calcium transporter (ATP2C1 gene), leading to impaired keratinocyte adhesion.2

Eczema herpeticum refers to the dissemination of herpes infection to areas of compromised skin barrier. Although originally used to describe HSV infection in patients with atopic dermatitis, eczema herpeticum has been described in various conditions that affect the skin barrier function, including Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mycosis fungoides, among others.3 When applied to skin conditions other than atopic dermatitis, it sometimes is referred to as Kaposi varicelliform eruption.2

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly is complicated by a bacterial or fungal infection, including impetigo, tinea, or candidiasis. The first case of HHD complicated by HSV infection was reported in 1973.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms benign familial pemphigus AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND eczema herpeticum, Hailey-Hailey AND Kaposi varicelliform eruption, and Hailey-Hailey herpeticum revealed 15 cases of HHD complicated by eczema herpeticum.4-6 Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a rare and life-threatening complication of eczema herpeticum.7,8 We report a case of HSV encephalitis resulting from eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD.

The clinical differential includes a flare of the patient's known HHD, secondary bacterial or fungal infection, or a superimposed viral infection (eg, HSV, zoster). Histologic evidence of herpetic infection would be absent in an uncomplicated flare of HHD. Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection that can present in 2 clinical forms: a vesiculopustular type and less commonly a bullous type. It is caused by Staphylococcus aureus in most cases. In multiple myeloma with cutaneous dissemination, a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells would be evident. Lastly, tinea corporis is caused by dermatophytes that can be seen on hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The diagnosis of eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD should be considered in patients who present with grouped vesicles or hemorrhagic or punched-out erosions in areas of pre-existing HHD. The diagnosis can be confirmed by Tzanck smear, viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, or histopathology (with or without immunohistochemistry).1,2,6 When eczema herpeticum is suspected, prompt antiviral administration is imperative to limit life-threatening systemic spread.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption (Eczema Herpeticum)

Polymerase chain reaction confirmed presence of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, and the patient was started on intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours). Diagnosis was further supported by histopathologic examination with confirmatory immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). The patient's anemia and thrombocytopenia also were attributed to widespread HSV infection.

Approximately 8 hours after the patient was started on acyclovir, he developed increasing tremors, confusion, and impaired speech. Lumbar puncture confirmed the presence of HSV-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid. Despite ongoing intravenous antiviral therapy, he required intubation 6 days after hospitalization due to impaired mental status and myoclonic jerking. He remained intubated, unresponsive, and in critical condition for 9 days before he gradually began to demonstrate cognitive recovery. He subsequently was weaned off the ventilator, his mental status returned to normal, and his skin rash slowly resolved (Figure 2).

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus, is a rare autosomal-dominant condition first described by Howard and Hugh Hailey in 1939.1 It is a chronic blistering process characterized by epidermal fragility, often manifesting as macerated fissured erosions in areas exposed to heat and friction (eg, axillae, groin). Hailey-Hailey disease results from a defective calcium transporter (ATP2C1 gene), leading to impaired keratinocyte adhesion.2

Eczema herpeticum refers to the dissemination of herpes infection to areas of compromised skin barrier. Although originally used to describe HSV infection in patients with atopic dermatitis, eczema herpeticum has been described in various conditions that affect the skin barrier function, including Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mycosis fungoides, among others.3 When applied to skin conditions other than atopic dermatitis, it sometimes is referred to as Kaposi varicelliform eruption.2

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly is complicated by a bacterial or fungal infection, including impetigo, tinea, or candidiasis. The first case of HHD complicated by HSV infection was reported in 1973.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms benign familial pemphigus AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND herpes, Hailey-Hailey AND eczema herpeticum, Hailey-Hailey AND Kaposi varicelliform eruption, and Hailey-Hailey herpeticum revealed 15 cases of HHD complicated by eczema herpeticum.4-6 Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a rare and life-threatening complication of eczema herpeticum.7,8 We report a case of HSV encephalitis resulting from eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD.

The clinical differential includes a flare of the patient's known HHD, secondary bacterial or fungal infection, or a superimposed viral infection (eg, HSV, zoster). Histologic evidence of herpetic infection would be absent in an uncomplicated flare of HHD. Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection that can present in 2 clinical forms: a vesiculopustular type and less commonly a bullous type. It is caused by Staphylococcus aureus in most cases. In multiple myeloma with cutaneous dissemination, a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells would be evident. Lastly, tinea corporis is caused by dermatophytes that can be seen on hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The diagnosis of eczema herpeticum in a patient with HHD should be considered in patients who present with grouped vesicles or hemorrhagic or punched-out erosions in areas of pre-existing HHD. The diagnosis can be confirmed by Tzanck smear, viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, or histopathology (with or without immunohistochemistry).1,2,6 When eczema herpeticum is suspected, prompt antiviral administration is imperative to limit life-threatening systemic spread.

- Hailey J, Hailey H. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:679-685.

- de Aquino Paulo Filho T, deFreitas YK, da Nóbrega MT, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease associated with herpetic eczema-the value of the Tzanck smear test. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:29-31.

- Flint ID, Spencer DM, Wilkin JK. Eczema herpeticum in association with familial benign chronic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2, pt 1):257-259.

- Leppard B, Delaney TJ, Sanderson KV. Chronic benign familial pemphigus. induction of lesions by Herpesvirus hominis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:609-613.

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zamperetti M, Pichler M, Perino F, et al. Ein fall von morbus Hailey-Hailey in verbindung mit einem eczema herpeticatum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1035-1038.

- Ingrand D, Briquet I, Babinet JM, et al. Eczema herpeticum of the child. an unusual manifestation of herpes simplex virus infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1985;24:660-663.

- Finlow C, Thomas J. Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:36-39.

- Hailey J, Hailey H. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:679-685.

- de Aquino Paulo Filho T, deFreitas YK, da Nóbrega MT, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease associated with herpetic eczema-the value of the Tzanck smear test. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:29-31.

- Flint ID, Spencer DM, Wilkin JK. Eczema herpeticum in association with familial benign chronic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2, pt 1):257-259.

- Leppard B, Delaney TJ, Sanderson KV. Chronic benign familial pemphigus. induction of lesions by Herpesvirus hominis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:609-613.

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zamperetti M, Pichler M, Perino F, et al. Ein fall von morbus Hailey-Hailey in verbindung mit einem eczema herpeticatum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1035-1038.

- Ingrand D, Briquet I, Babinet JM, et al. Eczema herpeticum of the child. an unusual manifestation of herpes simplex virus infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1985;24:660-663.

- Finlow C, Thomas J. Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:36-39.

A 62-year-old man with a long-standing history (>40 years) of Hailey-Hailey disease was admitted from an outside hospital due to anemia (hemoglobin, 8.6 g/dL [reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (platelets, 7×103 /µL [reference range, 150–350×103 /µL]), and worsening skin rash. The patient reported that his Hailey-Hailey disease worsened abruptly 1 month prior to admission and had progressed steadily since then. He described the rash as painful, especially with movement. Over the preceding month, he had been treated with topical triamcinolone, topical diphenhydramine, oral prednisone, fluconazole, and oral clindamycin, all without improvement. The skin lesions continued to worsen and persistently bled; he then presented to our institution for further care.

Physical examination demonstrated widespread shallow erosions with hemorrhagic drainage and crusting located on the lower back, chest, abdomen (top), axillae (bottom), groin, arms, and legs. No vesicles or pustules were noted. The patient had no cognitive dysfunction or focal neurologic deficits. A punch biopsy was performed.