User login

Umbilicated Neoplasm on the Chest

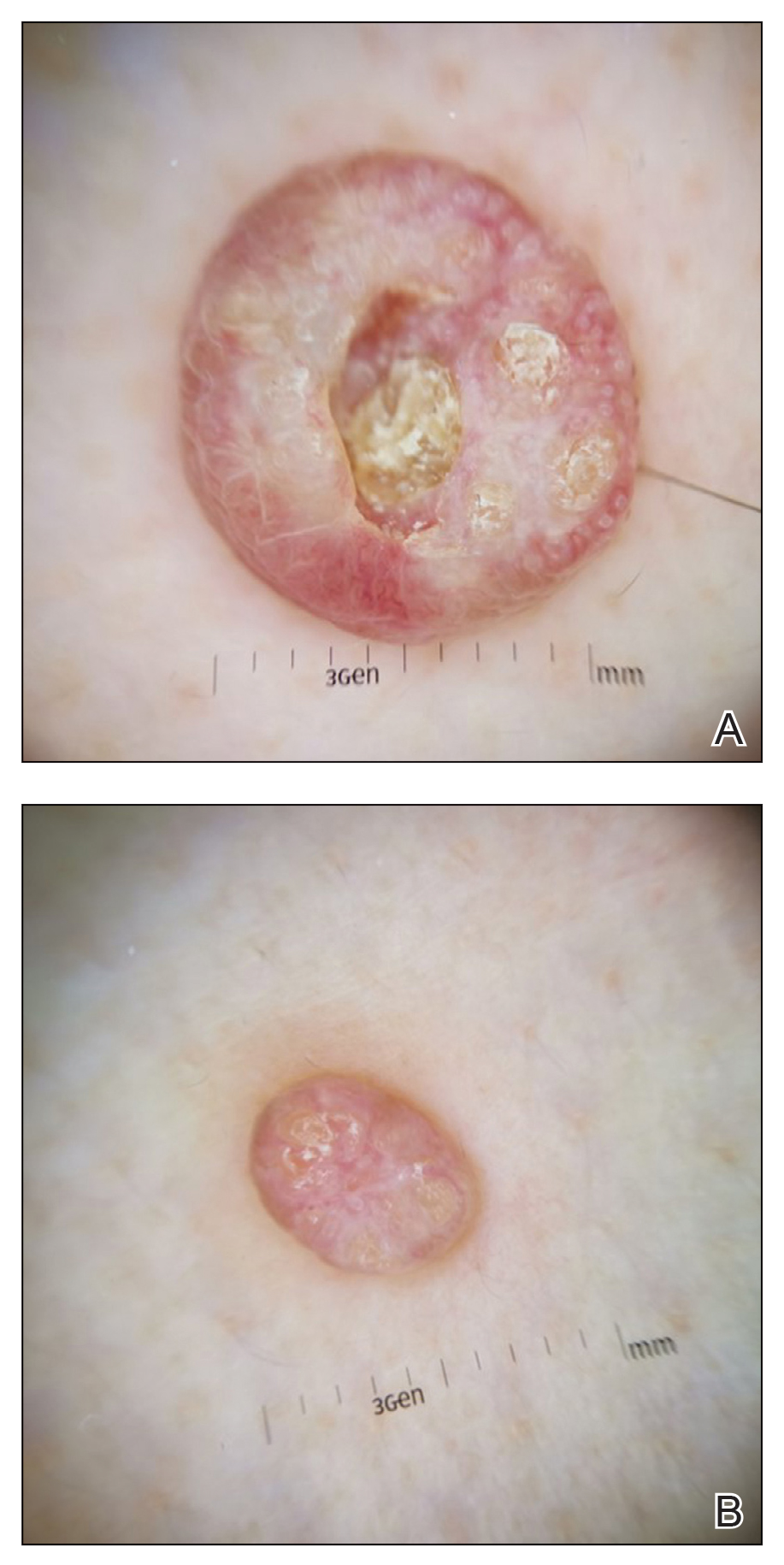

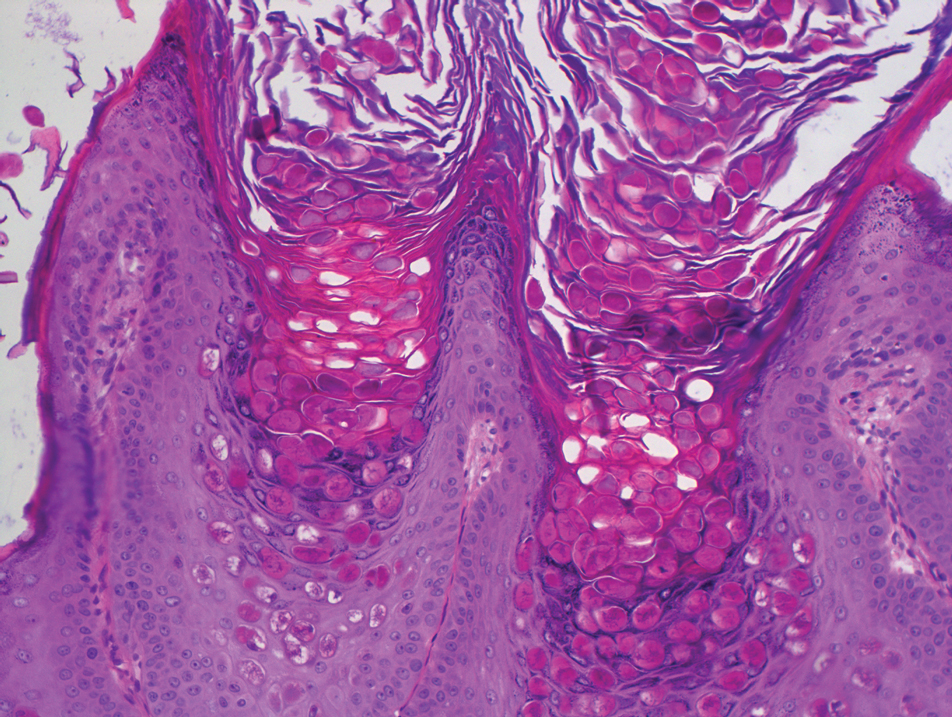

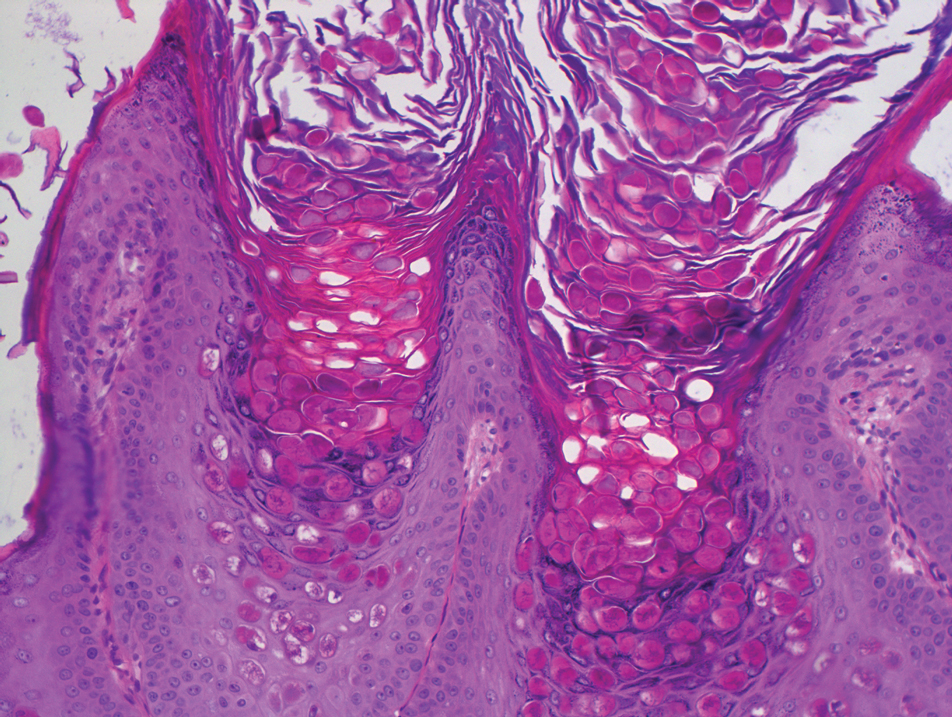

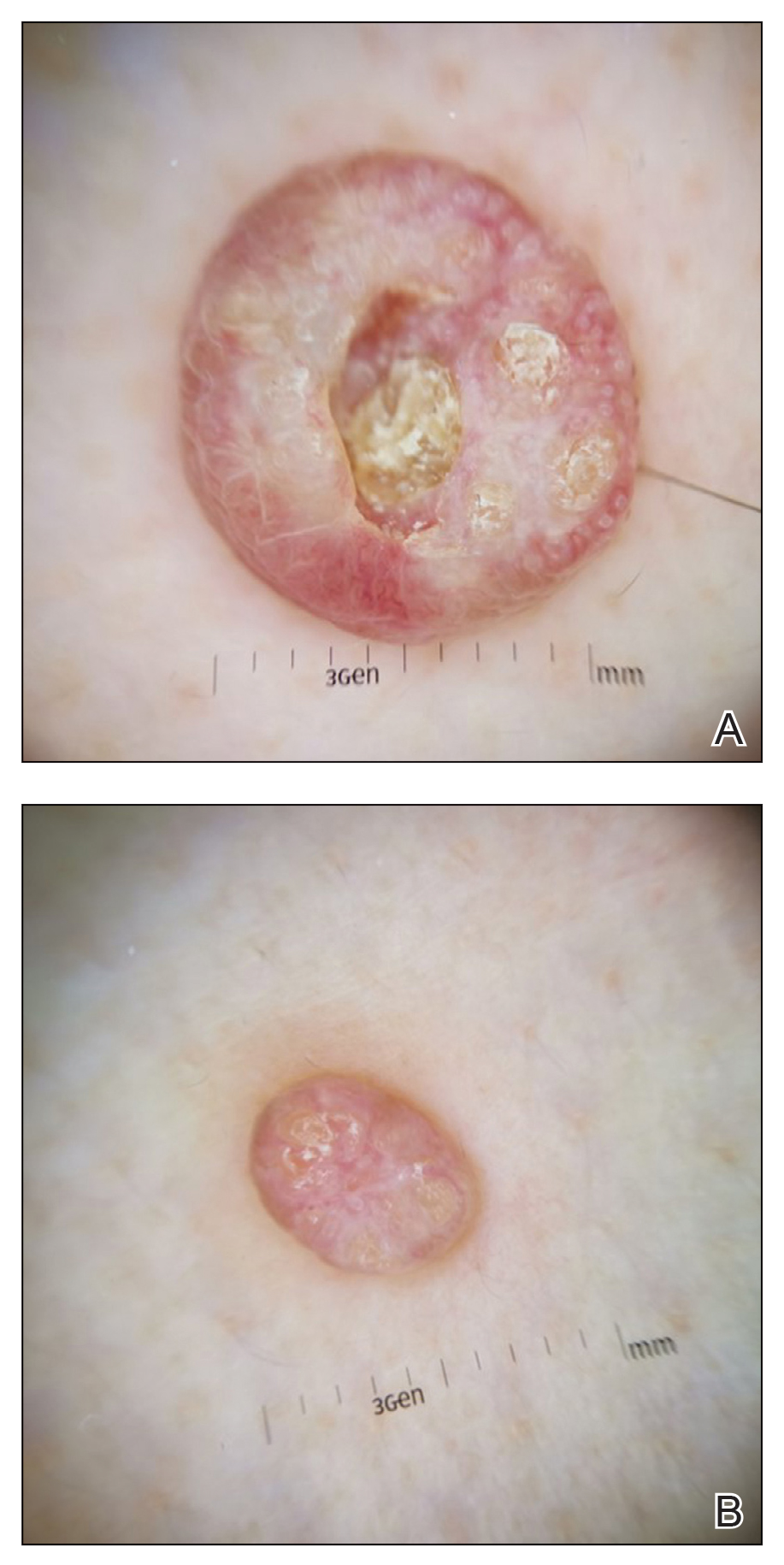

Dermoscopy showed polylobular, whitish yellow, amorphous structures at the center of the lesion surrounded by a crown of vessels (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed hyperplastic crateriform lesions containing large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes (Figure 2). At follow-up 2 weeks after the biopsy, the patient presented with approximately 20 more reddish papules of varying sizes on the abdomen and back that presented as dome-shaped papules and had a typical umbilicated center. The clinical manifestations, dermoscopy, and pathology findings were consistent with molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum was first described in 1814. It is a benign cutaneous infectious disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus of the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum lesions usually manifest clinically as dome-shaped, flesh-colored or translucent, umbilicated papules measuring 1 to 5 mm in diameter that are commonly distributed over the face, trunk, and extremities and usually are self-limiting.1

Giant MC is rare and can be seen either in patients on immunosuppressive therapy or in those with diseases that can cause immunosuppression, such as human immunodeficiency virus, leukemia, atopic dermatitis, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and sarcoidosis. In these instances, MC often is greater than 1 cm in diameter. Atypical variants may have an eczematous presentation or a lesion with secondary abscess formation and also can be spread widely over the body.2 Due to these atypical appearances and large dimensions in immunocompromised patients, other dermatologic diseases should be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous horn, cutaneous cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and xanthomatosis.3

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included keratoacanthoma, which may present as a solitary, discrete, round to oval, flesh-colored, umbilicated nodule with a central keratin-filled crater and has a rapid clinical evolution, usually regressing within 4 to 6 months.

Squamous cell carcinoma may appear as scaly red patches, open sores, warts, or elevated growths with a central depression and may crust or bleed. Basal cell carcinoma typically may appear as a dome-shaped skin nodule with visible blood vessels or sometimes presents as a red patch similar to eczema. Xanthomatosis often appears as yellow to orange, mostly asymptomatic, supple patches or plaques, usually with sharp and distinctive edges.

Ancillary diagnostic modalities such as dermoscopy may be used to improve diagnostic accuracy. The best known capillaroscopic feature of MC is the peripheral crown of vessels in a radial distribution. A study of 258 MC lesions highlighted that crown and crown plus radial arrangements are the most common vascular structure patterns under dermoscopy. In addition, polylobular amorphous white structures in the center of the lesions tend to be a feature of larger MC papules.4 Histologically, MC shows lobulated crateriform lesions, thickening of the epidermis into the dermis, and the typical appearance of large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes.5

There are several treatment options available for MC. Common modalities include liquid nitrogen cryospray, curettage, and electrocauterization. In immunocompromised patients, MC lesions usually are resistant to ordinary therapy. The efficacy of topical agents such as imiquimod, which can induce high levels of IFN-α and other cytokines, has been demonstrated in these patients.6 Cidofovir, a nucleoside analog that has potent antiviral properties, also can be included as a therapeutic option.3 Our patient’s largest MC lesion was treated with surgical excision, the 2 large lesions on the left side of the chest with cryotherapy, and the other small lesions with curettage.

- Hanson D, Diven DG. Molluscum contagiosum. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:2.

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796.

- Mansur AT, Goktay F, Gunduz S, et al. Multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6:120-123.

- Ku SH, Cho EB, Park EJ, et al. Dermoscopic features of molluscum contagiosum based on white structures and their correlation with histopathological findings. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:208-210.

- Trčko K, Hošnjak L, Kušar B, et al. Clinical, histopathological, and virological evaluation of 203 patients with a clinical diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum [published online November 12, 2018]. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5.

- Gardner LS, Ormond PJ. Treatment of multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant patient with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;31:452-453.

Dermoscopy showed polylobular, whitish yellow, amorphous structures at the center of the lesion surrounded by a crown of vessels (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed hyperplastic crateriform lesions containing large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes (Figure 2). At follow-up 2 weeks after the biopsy, the patient presented with approximately 20 more reddish papules of varying sizes on the abdomen and back that presented as dome-shaped papules and had a typical umbilicated center. The clinical manifestations, dermoscopy, and pathology findings were consistent with molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum was first described in 1814. It is a benign cutaneous infectious disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus of the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum lesions usually manifest clinically as dome-shaped, flesh-colored or translucent, umbilicated papules measuring 1 to 5 mm in diameter that are commonly distributed over the face, trunk, and extremities and usually are self-limiting.1

Giant MC is rare and can be seen either in patients on immunosuppressive therapy or in those with diseases that can cause immunosuppression, such as human immunodeficiency virus, leukemia, atopic dermatitis, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and sarcoidosis. In these instances, MC often is greater than 1 cm in diameter. Atypical variants may have an eczematous presentation or a lesion with secondary abscess formation and also can be spread widely over the body.2 Due to these atypical appearances and large dimensions in immunocompromised patients, other dermatologic diseases should be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous horn, cutaneous cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and xanthomatosis.3

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included keratoacanthoma, which may present as a solitary, discrete, round to oval, flesh-colored, umbilicated nodule with a central keratin-filled crater and has a rapid clinical evolution, usually regressing within 4 to 6 months.

Squamous cell carcinoma may appear as scaly red patches, open sores, warts, or elevated growths with a central depression and may crust or bleed. Basal cell carcinoma typically may appear as a dome-shaped skin nodule with visible blood vessels or sometimes presents as a red patch similar to eczema. Xanthomatosis often appears as yellow to orange, mostly asymptomatic, supple patches or plaques, usually with sharp and distinctive edges.

Ancillary diagnostic modalities such as dermoscopy may be used to improve diagnostic accuracy. The best known capillaroscopic feature of MC is the peripheral crown of vessels in a radial distribution. A study of 258 MC lesions highlighted that crown and crown plus radial arrangements are the most common vascular structure patterns under dermoscopy. In addition, polylobular amorphous white structures in the center of the lesions tend to be a feature of larger MC papules.4 Histologically, MC shows lobulated crateriform lesions, thickening of the epidermis into the dermis, and the typical appearance of large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes.5

There are several treatment options available for MC. Common modalities include liquid nitrogen cryospray, curettage, and electrocauterization. In immunocompromised patients, MC lesions usually are resistant to ordinary therapy. The efficacy of topical agents such as imiquimod, which can induce high levels of IFN-α and other cytokines, has been demonstrated in these patients.6 Cidofovir, a nucleoside analog that has potent antiviral properties, also can be included as a therapeutic option.3 Our patient’s largest MC lesion was treated with surgical excision, the 2 large lesions on the left side of the chest with cryotherapy, and the other small lesions with curettage.

Dermoscopy showed polylobular, whitish yellow, amorphous structures at the center of the lesion surrounded by a crown of vessels (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed hyperplastic crateriform lesions containing large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes (Figure 2). At follow-up 2 weeks after the biopsy, the patient presented with approximately 20 more reddish papules of varying sizes on the abdomen and back that presented as dome-shaped papules and had a typical umbilicated center. The clinical manifestations, dermoscopy, and pathology findings were consistent with molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum was first described in 1814. It is a benign cutaneous infectious disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus of the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum lesions usually manifest clinically as dome-shaped, flesh-colored or translucent, umbilicated papules measuring 1 to 5 mm in diameter that are commonly distributed over the face, trunk, and extremities and usually are self-limiting.1

Giant MC is rare and can be seen either in patients on immunosuppressive therapy or in those with diseases that can cause immunosuppression, such as human immunodeficiency virus, leukemia, atopic dermatitis, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and sarcoidosis. In these instances, MC often is greater than 1 cm in diameter. Atypical variants may have an eczematous presentation or a lesion with secondary abscess formation and also can be spread widely over the body.2 Due to these atypical appearances and large dimensions in immunocompromised patients, other dermatologic diseases should be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous horn, cutaneous cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and xanthomatosis.3

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included keratoacanthoma, which may present as a solitary, discrete, round to oval, flesh-colored, umbilicated nodule with a central keratin-filled crater and has a rapid clinical evolution, usually regressing within 4 to 6 months.

Squamous cell carcinoma may appear as scaly red patches, open sores, warts, or elevated growths with a central depression and may crust or bleed. Basal cell carcinoma typically may appear as a dome-shaped skin nodule with visible blood vessels or sometimes presents as a red patch similar to eczema. Xanthomatosis often appears as yellow to orange, mostly asymptomatic, supple patches or plaques, usually with sharp and distinctive edges.

Ancillary diagnostic modalities such as dermoscopy may be used to improve diagnostic accuracy. The best known capillaroscopic feature of MC is the peripheral crown of vessels in a radial distribution. A study of 258 MC lesions highlighted that crown and crown plus radial arrangements are the most common vascular structure patterns under dermoscopy. In addition, polylobular amorphous white structures in the center of the lesions tend to be a feature of larger MC papules.4 Histologically, MC shows lobulated crateriform lesions, thickening of the epidermis into the dermis, and the typical appearance of large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes.5

There are several treatment options available for MC. Common modalities include liquid nitrogen cryospray, curettage, and electrocauterization. In immunocompromised patients, MC lesions usually are resistant to ordinary therapy. The efficacy of topical agents such as imiquimod, which can induce high levels of IFN-α and other cytokines, has been demonstrated in these patients.6 Cidofovir, a nucleoside analog that has potent antiviral properties, also can be included as a therapeutic option.3 Our patient’s largest MC lesion was treated with surgical excision, the 2 large lesions on the left side of the chest with cryotherapy, and the other small lesions with curettage.

- Hanson D, Diven DG. Molluscum contagiosum. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:2.

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796.

- Mansur AT, Goktay F, Gunduz S, et al. Multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6:120-123.

- Ku SH, Cho EB, Park EJ, et al. Dermoscopic features of molluscum contagiosum based on white structures and their correlation with histopathological findings. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:208-210.

- Trčko K, Hošnjak L, Kušar B, et al. Clinical, histopathological, and virological evaluation of 203 patients with a clinical diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum [published online November 12, 2018]. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5.

- Gardner LS, Ormond PJ. Treatment of multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant patient with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;31:452-453.

- Hanson D, Diven DG. Molluscum contagiosum. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:2.

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796.

- Mansur AT, Goktay F, Gunduz S, et al. Multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6:120-123.

- Ku SH, Cho EB, Park EJ, et al. Dermoscopic features of molluscum contagiosum based on white structures and their correlation with histopathological findings. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:208-210.

- Trčko K, Hošnjak L, Kušar B, et al. Clinical, histopathological, and virological evaluation of 203 patients with a clinical diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum [published online November 12, 2018]. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5.

- Gardner LS, Ormond PJ. Treatment of multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant patient with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;31:452-453.

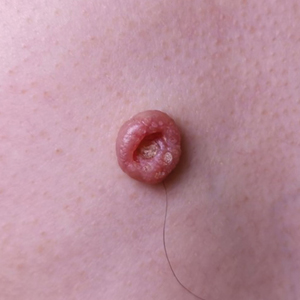

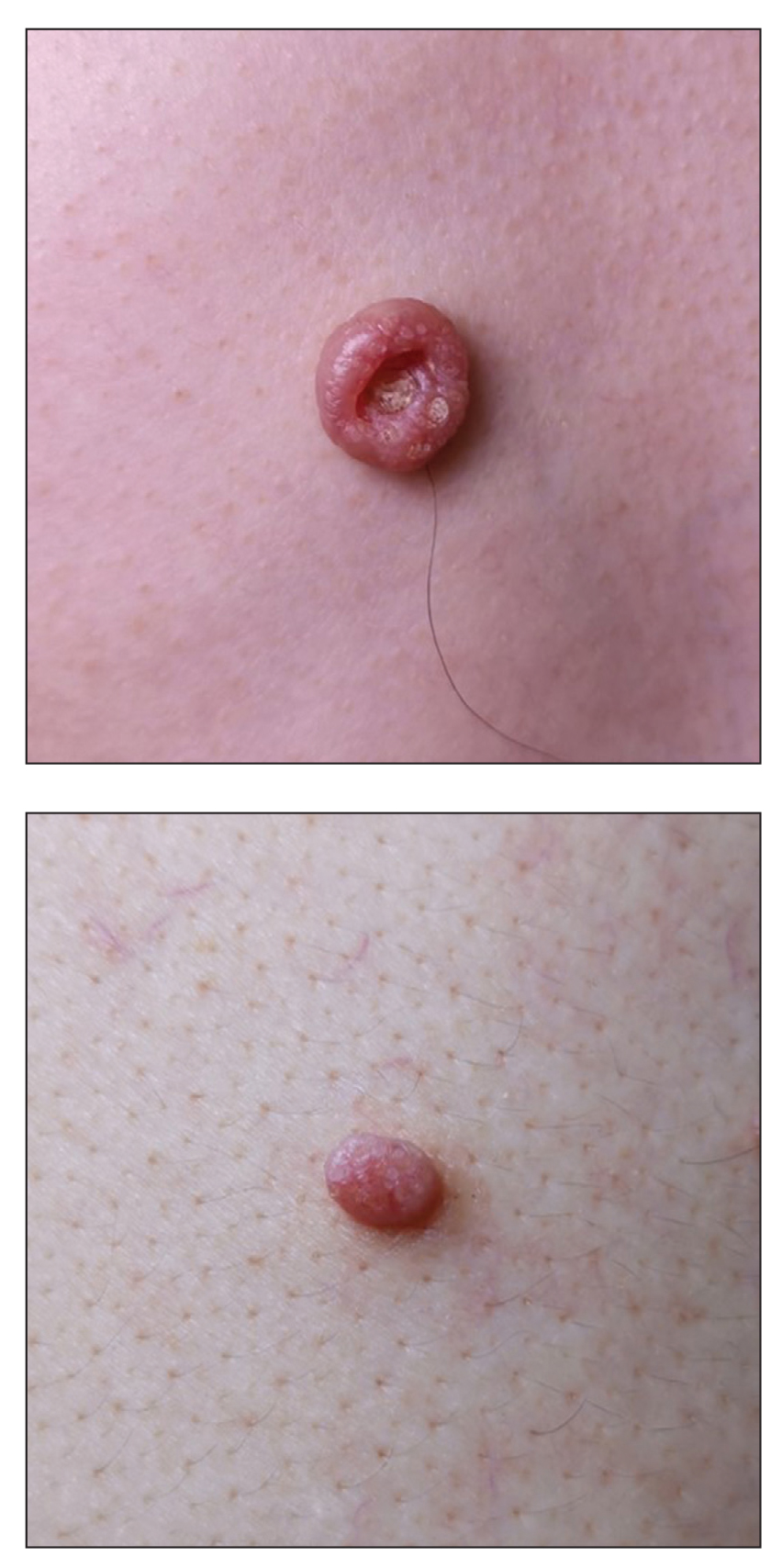

A 49-year-old man presented with a slow-growing mass on the chest of 1 year’s duration. The neoplasm started as a small papule that gradually increased in size. The patient denied pain, itching, bleeding, or discharge. He had a history of end-stage renal disease with a kidney transplant 8 years prior. His medication history included long-term use of oral tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. Physical examination revealed a yellowish red, exogenous, pedunculated neoplasm on the right side of the chest measuring 1 cm in diameter with an umbilicated center and keratotic material (top). There were 2 more yellowish red papules on the left side of the chest measuring 0.5 cm in diameter without an umbilicated center (bottom). Dermoscopy and a biopsy were performed.

Erythematous Plaque on the Scalp With Alopecia

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

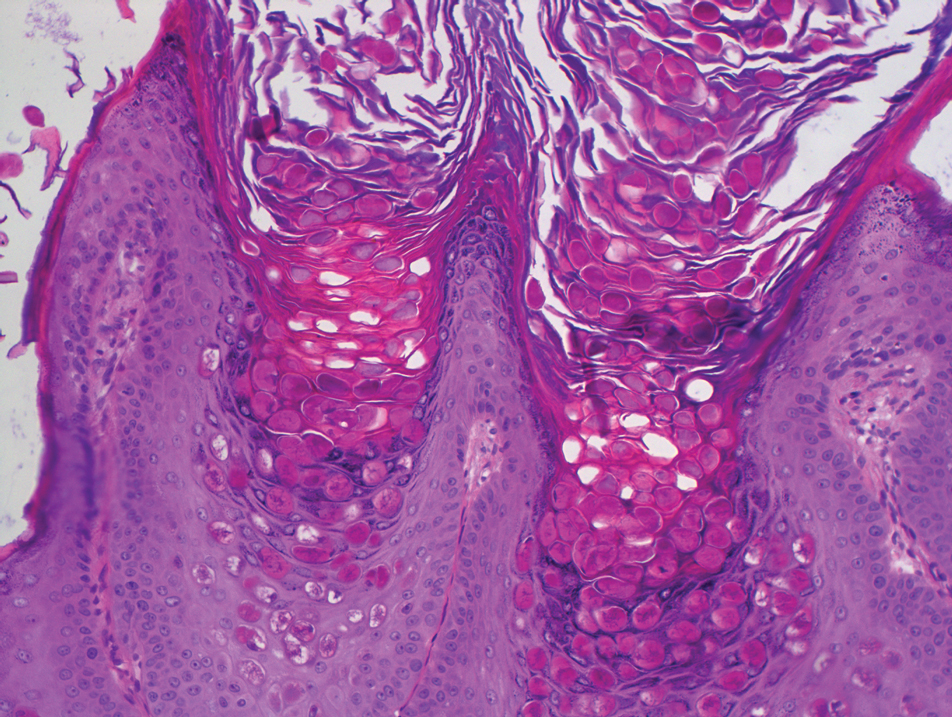

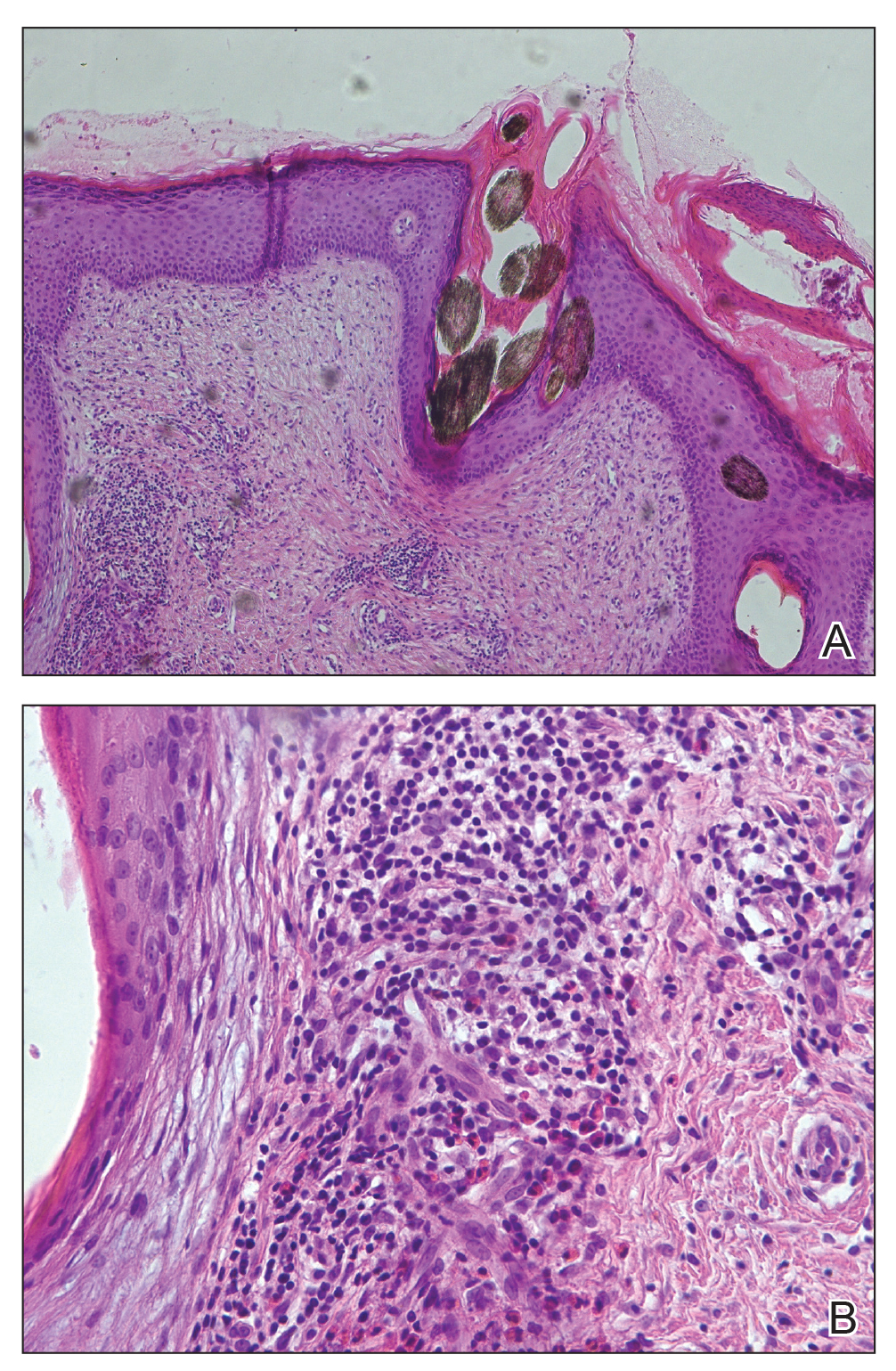

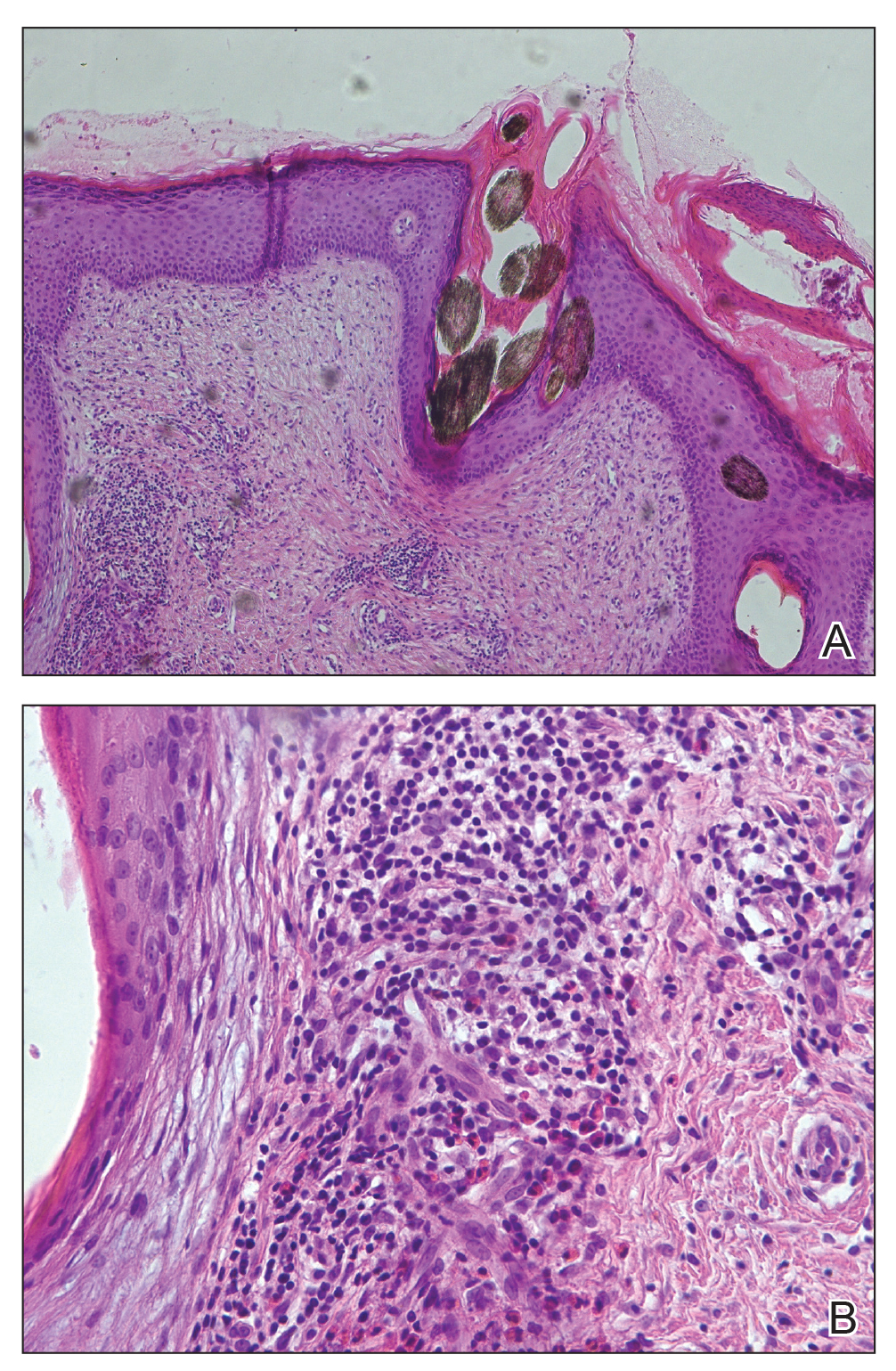

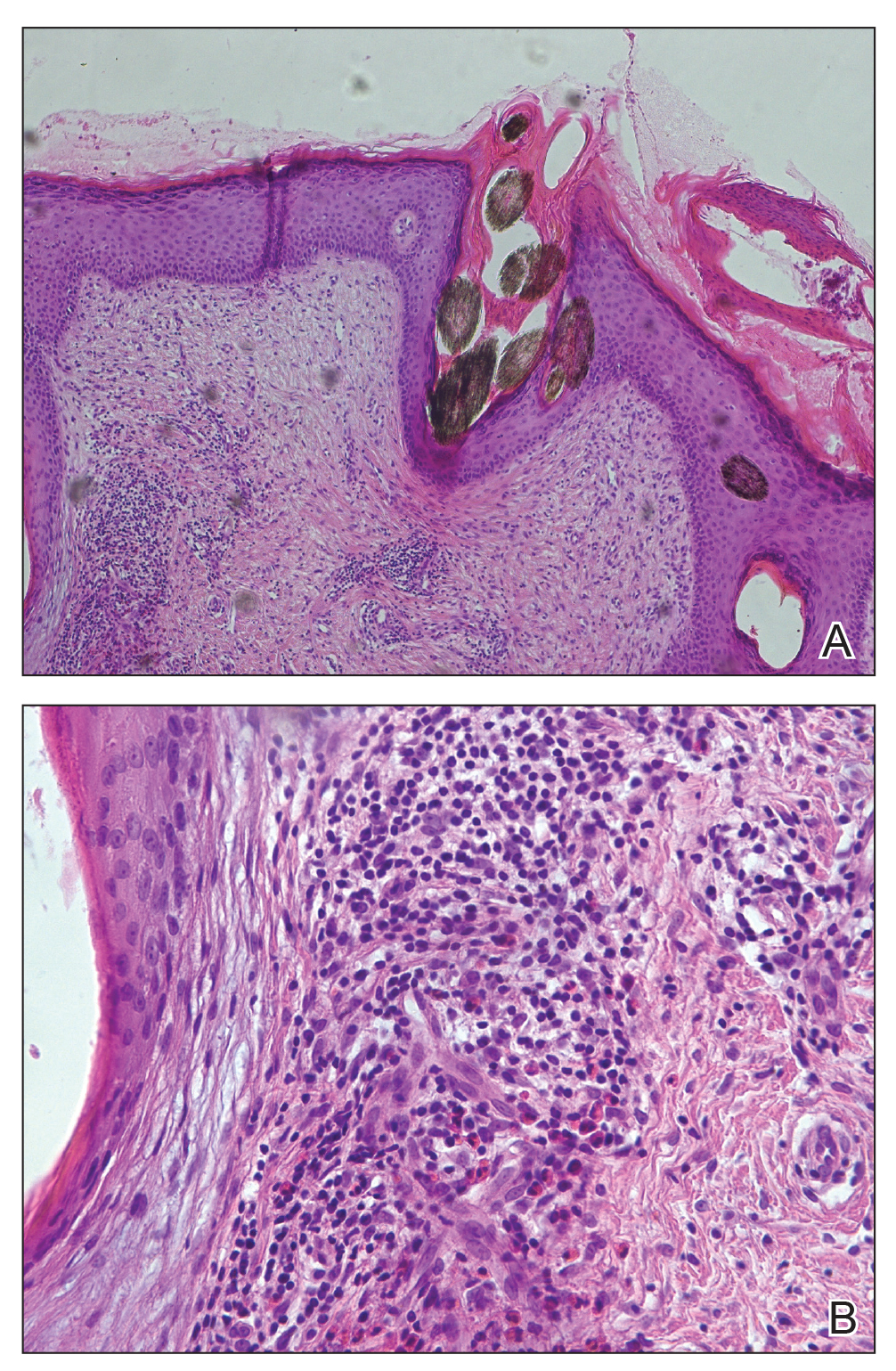

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

A 37-year-old woman presented with a 2×6-cm, firm, erythematous plaque on the parietal region of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. No history of injury to the scalp was noted. The patient noticed hair loss in the affected area in the month prior to presentation. She was afebrile and otherwise asymptomatic. She denied a family history of similar scalp disorders.

Acute Painful Rash on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Acute Contact Dermatitis

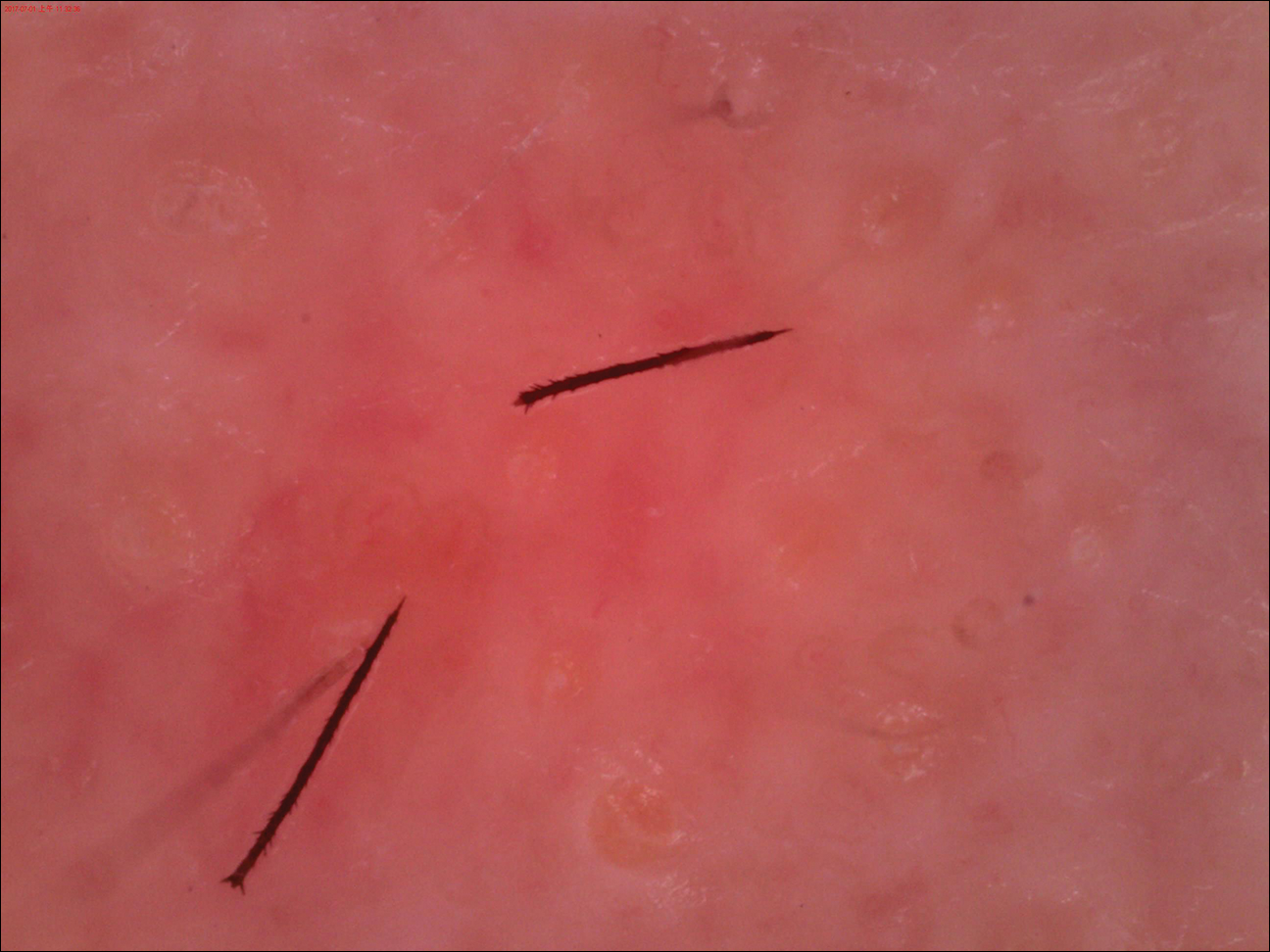

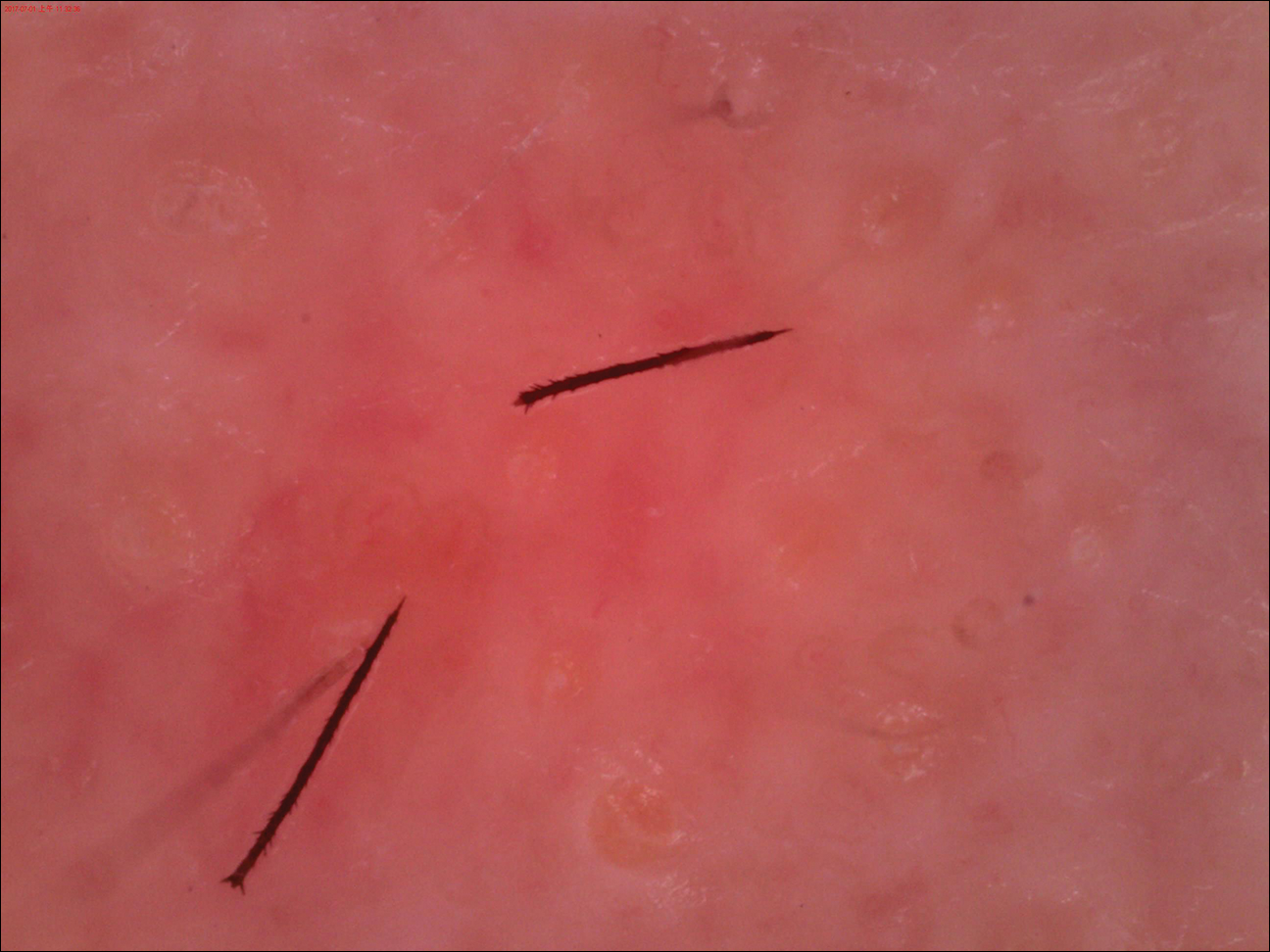

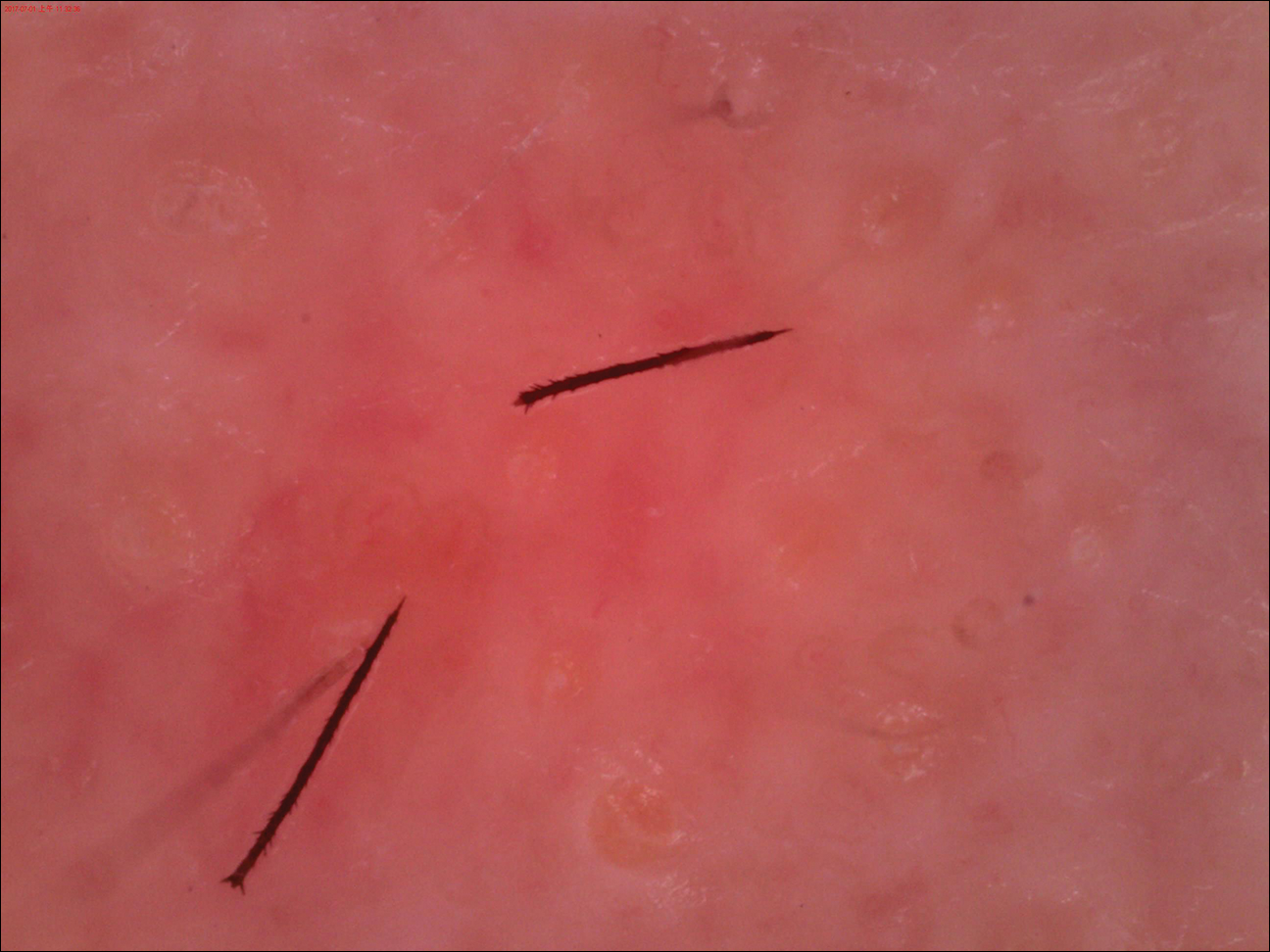

Dermoscopy demonstrated caterpillar hairs (Figure) and established the diagnosis of acute contact dermatitis due to a caterpillar. Upon further questioning, the patient recalled that something dustlike fell on the left cheek as she walked under some trees. The clinical and dermoscopic findings suggested a diagnosis of caterpillar dermatitis (family Limacodidae or Lymantriinae, order Lepidoptera). During the life cycle from young larvae to mature larvae, the quantities of the toxic thorns and hairs increase from 60,000 to 80,000 to 2,000,000 to 3,000,000. The toxic hairs measure 0.5 to 2.0 mm in length. They drop from the mature larvae's skin during desquamation as well as from the cocoon curing maturation to a moth. The hairs appear tubular and arrowlike with terminal spines.1 The larvae are called "the fiery hot" in Chinese, which vividly describes the swelling and sensation of burning with immediate contact.

Eruption severity and distribution depend on exposure modality and intensity. Exposed body parts, including the face, neck, forearms, interdigital spaces, and dorsal aspects of the hands, most commonly are involved. The eruption can be immediate or delayed, occurring hours or even days after the first contact.2 Itching is intense and continuous, with intermittent worsening. Clinically, the eruption manifests with rose to bright red, round macules and papules. Although rare, skin manifestations can be accompanied by systemic symptoms, such as malaise, fever, and anaphylaxis syndrome.3 The cutaneous lesions may last for 3 to 4 days and subside, leaving a brownish macule.1,4

The differential diagnosis includes acute herpes simplex, which presents as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base with itching or burning, and recurrences in the same location are common. Acute Sweet syndrome may appear as erythematous or edematous painful plaques with fever and neutrophilia. Acute urticaria appears as wheals with severe pruritus, and individual lesions can resolve within several hours. Insect bites often appear as itching or painful erythema or papules.

We sterilized the lesion with alcohol, removed the thorns as much as possible with ophthalmic forceps under the guidance of dermoscopy, and prescribed chloramphenicol ointment 1% twice daily. Our patient was completely cured within 24 hours with no systemic symptoms or pigmentation.

This case directly showed a novel usage of dermoscopy in diagnosis and therapy, especially in acute contact dermatitis. Small irritants such as caterpillar thorns and hairs easily can be observed and removed by dermoscopy devices with higher magnification.

- Fangan H, Yun H, Yuhua G, et al. Observations on the pathogenicity of Lepidoptera, Euileidae caterpillar and the clinical pathological pictures of patients with dermatitis. Chinese J Zoonoses. 2005,21:414-416.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Vestita M, et al. Skin reactions to pine processionary caterpillar Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:867431.

- Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell; 2010.

- Henwood BP, MacDonald DM. Caterpillar dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:77-93.

The Diagnosis: Acute Contact Dermatitis

Dermoscopy demonstrated caterpillar hairs (Figure) and established the diagnosis of acute contact dermatitis due to a caterpillar. Upon further questioning, the patient recalled that something dustlike fell on the left cheek as she walked under some trees. The clinical and dermoscopic findings suggested a diagnosis of caterpillar dermatitis (family Limacodidae or Lymantriinae, order Lepidoptera). During the life cycle from young larvae to mature larvae, the quantities of the toxic thorns and hairs increase from 60,000 to 80,000 to 2,000,000 to 3,000,000. The toxic hairs measure 0.5 to 2.0 mm in length. They drop from the mature larvae's skin during desquamation as well as from the cocoon curing maturation to a moth. The hairs appear tubular and arrowlike with terminal spines.1 The larvae are called "the fiery hot" in Chinese, which vividly describes the swelling and sensation of burning with immediate contact.

Eruption severity and distribution depend on exposure modality and intensity. Exposed body parts, including the face, neck, forearms, interdigital spaces, and dorsal aspects of the hands, most commonly are involved. The eruption can be immediate or delayed, occurring hours or even days after the first contact.2 Itching is intense and continuous, with intermittent worsening. Clinically, the eruption manifests with rose to bright red, round macules and papules. Although rare, skin manifestations can be accompanied by systemic symptoms, such as malaise, fever, and anaphylaxis syndrome.3 The cutaneous lesions may last for 3 to 4 days and subside, leaving a brownish macule.1,4

The differential diagnosis includes acute herpes simplex, which presents as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base with itching or burning, and recurrences in the same location are common. Acute Sweet syndrome may appear as erythematous or edematous painful plaques with fever and neutrophilia. Acute urticaria appears as wheals with severe pruritus, and individual lesions can resolve within several hours. Insect bites often appear as itching or painful erythema or papules.

We sterilized the lesion with alcohol, removed the thorns as much as possible with ophthalmic forceps under the guidance of dermoscopy, and prescribed chloramphenicol ointment 1% twice daily. Our patient was completely cured within 24 hours with no systemic symptoms or pigmentation.

This case directly showed a novel usage of dermoscopy in diagnosis and therapy, especially in acute contact dermatitis. Small irritants such as caterpillar thorns and hairs easily can be observed and removed by dermoscopy devices with higher magnification.

The Diagnosis: Acute Contact Dermatitis

Dermoscopy demonstrated caterpillar hairs (Figure) and established the diagnosis of acute contact dermatitis due to a caterpillar. Upon further questioning, the patient recalled that something dustlike fell on the left cheek as she walked under some trees. The clinical and dermoscopic findings suggested a diagnosis of caterpillar dermatitis (family Limacodidae or Lymantriinae, order Lepidoptera). During the life cycle from young larvae to mature larvae, the quantities of the toxic thorns and hairs increase from 60,000 to 80,000 to 2,000,000 to 3,000,000. The toxic hairs measure 0.5 to 2.0 mm in length. They drop from the mature larvae's skin during desquamation as well as from the cocoon curing maturation to a moth. The hairs appear tubular and arrowlike with terminal spines.1 The larvae are called "the fiery hot" in Chinese, which vividly describes the swelling and sensation of burning with immediate contact.

Eruption severity and distribution depend on exposure modality and intensity. Exposed body parts, including the face, neck, forearms, interdigital spaces, and dorsal aspects of the hands, most commonly are involved. The eruption can be immediate or delayed, occurring hours or even days after the first contact.2 Itching is intense and continuous, with intermittent worsening. Clinically, the eruption manifests with rose to bright red, round macules and papules. Although rare, skin manifestations can be accompanied by systemic symptoms, such as malaise, fever, and anaphylaxis syndrome.3 The cutaneous lesions may last for 3 to 4 days and subside, leaving a brownish macule.1,4

The differential diagnosis includes acute herpes simplex, which presents as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base with itching or burning, and recurrences in the same location are common. Acute Sweet syndrome may appear as erythematous or edematous painful plaques with fever and neutrophilia. Acute urticaria appears as wheals with severe pruritus, and individual lesions can resolve within several hours. Insect bites often appear as itching or painful erythema or papules.

We sterilized the lesion with alcohol, removed the thorns as much as possible with ophthalmic forceps under the guidance of dermoscopy, and prescribed chloramphenicol ointment 1% twice daily. Our patient was completely cured within 24 hours with no systemic symptoms or pigmentation.

This case directly showed a novel usage of dermoscopy in diagnosis and therapy, especially in acute contact dermatitis. Small irritants such as caterpillar thorns and hairs easily can be observed and removed by dermoscopy devices with higher magnification.

- Fangan H, Yun H, Yuhua G, et al. Observations on the pathogenicity of Lepidoptera, Euileidae caterpillar and the clinical pathological pictures of patients with dermatitis. Chinese J Zoonoses. 2005,21:414-416.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Vestita M, et al. Skin reactions to pine processionary caterpillar Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:867431.

- Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell; 2010.

- Henwood BP, MacDonald DM. Caterpillar dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:77-93.

- Fangan H, Yun H, Yuhua G, et al. Observations on the pathogenicity of Lepidoptera, Euileidae caterpillar and the clinical pathological pictures of patients with dermatitis. Chinese J Zoonoses. 2005,21:414-416.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Vestita M, et al. Skin reactions to pine processionary caterpillar Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:867431.

- Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell; 2010.

- Henwood BP, MacDonald DM. Caterpillar dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:77-93.

A 31-year-old woman presented to an outpatient dermatology department with acute pruritus, burning, and moderate swelling of the left cheek of 10 minutes' duration that occurred while waiting to see a hematologist in the same building. The patient was diagnosed with aplastic anemia 11 years prior and was awaiting bone marrow transplantation. Physical examination showed an edematous erythematous wheal with a relatively distinct border measuring 3 cm in diameter. No foreign material could be identified on the surface with the naked eye. Dermoscopy was performed.