User login

Unilateral Alar Ulceration

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (Self-induced Trauma)

The patient admitted to manipulation of the ala in response to persistent pain despite resolution of the herpes zoster, for which he recently had completed a course of oral acyclovir. A preliminary diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) was made, and a subsequent punch biopsy revealed no evidence of malignancy. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed, and he was instructed to avoid manipulation of the affected area. Treatment was initiated in consultation with pain specialists, and over the following 3 years our patient experienced a waxing and waning course of persistent pain complicated by new scalp and oral ulcers as well as alar impetigo. His condition eventually stabilized with tolerable pain on oral gabapentin and doxepin cream 5% applied up to 4 times daily. The alar lesion healed following sufficient abstinence from manipulation, leaving a crescent-shaped rim defect.

Trigeminal trophic syndrome classically is characterized by a triad of cutaneous anesthesia, paresthesia and/or pain, and ulceration secondary to pathology of trigeminal nerve sensory branches. Ulceration arises primarily through excoriation in response to paresthetic pruritus or pain. The differential diagnosis for TTS includes ulcerating cutaneous neoplasms (eg, basal cell carcinoma); mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections (especially herpetic lesions); and cutaneous involvement of systemic vasculitides (eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).1 Biopsy is necessary to exclude malignancy, and ulcers may be scraped for viral diagnosis. Complete blood cell count and serologic testing also may help to exclude immunodeficiencies or disorders. Apart from viral neuropathy, common etiologies of TTS include iatrogenic trigeminal injury (eg, in ablation treatment for trigeminal neuralgia) and stroke (eg, lateral medullary syndrome).

- Khan AU, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:530-537.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (Self-induced Trauma)

The patient admitted to manipulation of the ala in response to persistent pain despite resolution of the herpes zoster, for which he recently had completed a course of oral acyclovir. A preliminary diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) was made, and a subsequent punch biopsy revealed no evidence of malignancy. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed, and he was instructed to avoid manipulation of the affected area. Treatment was initiated in consultation with pain specialists, and over the following 3 years our patient experienced a waxing and waning course of persistent pain complicated by new scalp and oral ulcers as well as alar impetigo. His condition eventually stabilized with tolerable pain on oral gabapentin and doxepin cream 5% applied up to 4 times daily. The alar lesion healed following sufficient abstinence from manipulation, leaving a crescent-shaped rim defect.

Trigeminal trophic syndrome classically is characterized by a triad of cutaneous anesthesia, paresthesia and/or pain, and ulceration secondary to pathology of trigeminal nerve sensory branches. Ulceration arises primarily through excoriation in response to paresthetic pruritus or pain. The differential diagnosis for TTS includes ulcerating cutaneous neoplasms (eg, basal cell carcinoma); mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections (especially herpetic lesions); and cutaneous involvement of systemic vasculitides (eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).1 Biopsy is necessary to exclude malignancy, and ulcers may be scraped for viral diagnosis. Complete blood cell count and serologic testing also may help to exclude immunodeficiencies or disorders. Apart from viral neuropathy, common etiologies of TTS include iatrogenic trigeminal injury (eg, in ablation treatment for trigeminal neuralgia) and stroke (eg, lateral medullary syndrome).

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (Self-induced Trauma)

The patient admitted to manipulation of the ala in response to persistent pain despite resolution of the herpes zoster, for which he recently had completed a course of oral acyclovir. A preliminary diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) was made, and a subsequent punch biopsy revealed no evidence of malignancy. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed, and he was instructed to avoid manipulation of the affected area. Treatment was initiated in consultation with pain specialists, and over the following 3 years our patient experienced a waxing and waning course of persistent pain complicated by new scalp and oral ulcers as well as alar impetigo. His condition eventually stabilized with tolerable pain on oral gabapentin and doxepin cream 5% applied up to 4 times daily. The alar lesion healed following sufficient abstinence from manipulation, leaving a crescent-shaped rim defect.

Trigeminal trophic syndrome classically is characterized by a triad of cutaneous anesthesia, paresthesia and/or pain, and ulceration secondary to pathology of trigeminal nerve sensory branches. Ulceration arises primarily through excoriation in response to paresthetic pruritus or pain. The differential diagnosis for TTS includes ulcerating cutaneous neoplasms (eg, basal cell carcinoma); mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections (especially herpetic lesions); and cutaneous involvement of systemic vasculitides (eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).1 Biopsy is necessary to exclude malignancy, and ulcers may be scraped for viral diagnosis. Complete blood cell count and serologic testing also may help to exclude immunodeficiencies or disorders. Apart from viral neuropathy, common etiologies of TTS include iatrogenic trigeminal injury (eg, in ablation treatment for trigeminal neuralgia) and stroke (eg, lateral medullary syndrome).

- Khan AU, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:530-537.

- Khan AU, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:530-537.

A 68-year-old man presented with a new left nasal alar ulcer following a recent episode of primary herpes zoster. Physical examination revealed erythema, erosion, and necrosis of the left naris with partial loss of the alar rim. Additional erythema was present without vesicles around the left eye and on the forehead.

Telangiectatic Patch on the Forehead

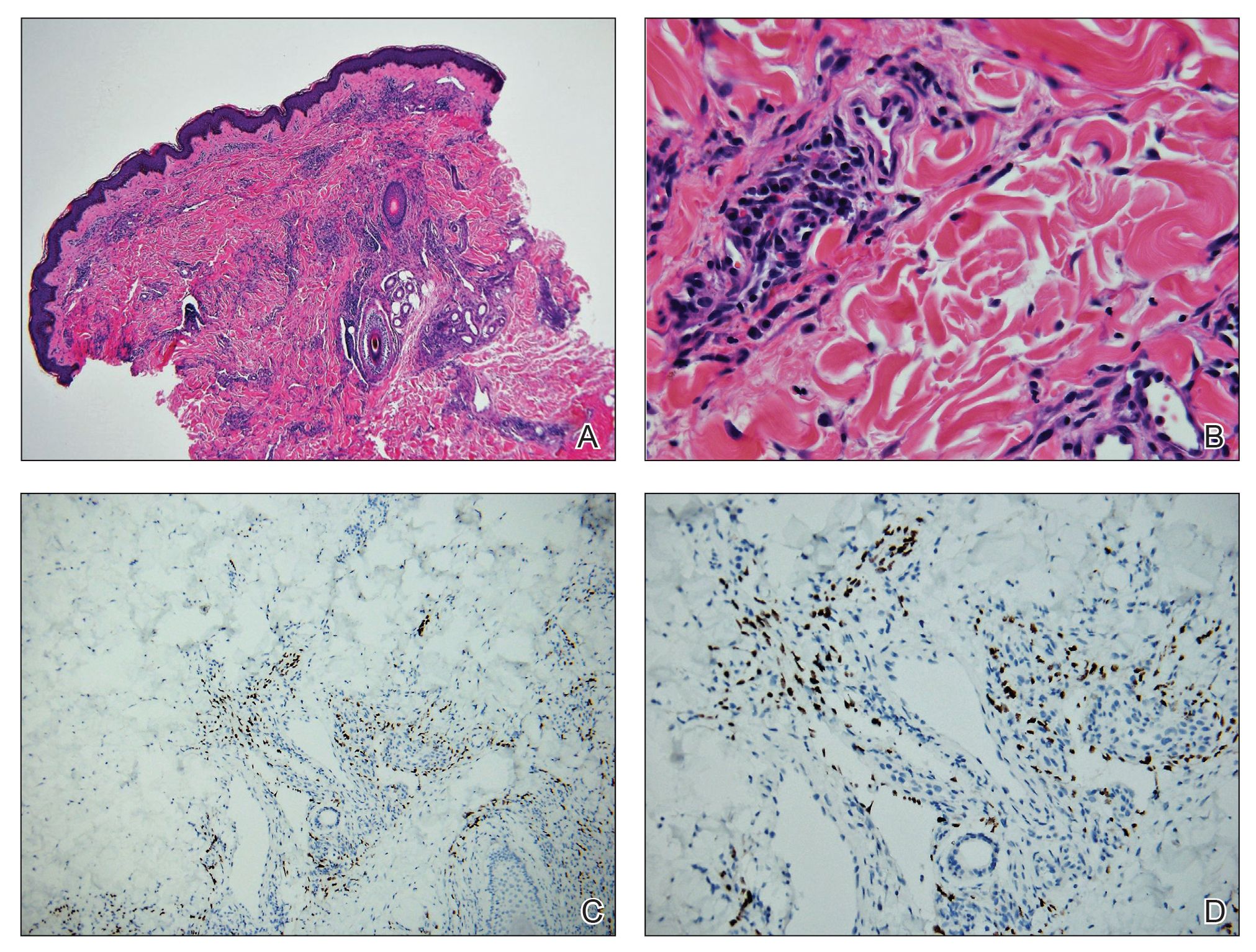

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are chronic skin disorders characterized by purpura due to extravasation of blood from capillaries; the resulting hemosiderin deposition leads to pigmentation.7 There are various forms of PPD, which are classified into groups based on clinical appearance including Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and others including eczematid and itching variants, which some consider to be distinct entities. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi is the specific PPD that should be included in the clinical differential for PCFCL because it presents as annular patches with telangiectasias. Histologically, PPDs are characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis with extravasated red blood cells and the presence of hemosiderin mostly within macrophages and a lack of true vasculitis. Clonality of the T cells has been shown, and there is some evidence that PPD may overlap with mycosis fungoides. However, this overlap mainly has been seen in patients with widespread lesions and would not apply to this case. In general, patients with PPD can be reassured of the benign process. In cases of widespread PPD, patients should be followed clinically to assess for progression to mycosis fungoides, though the likelihood is low.7

Our patient underwent a full staging workup, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCFCL. He was treated with radiation to the forehead that resulted in clearance of the lesion. Approximately 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was alive and well with no evidence of recurrence of PCFCL.

In conclusion, it is imperative to identify unusual, macular, vascular-appearing patches, especially on the head and neck in older individuals. Because the clinical presentations of PCFCL, angiosarcoma, rosacea, MCC, and PPD can overlap with one another as well as with other entities, it is necessary to have a high level of suspicion and low threshold to biopsy these types of lesions, as outcomes can be drastically different.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Atypical clinical presentation of primary and secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) on the head characterized by macular lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1000-1006.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Conic RRZ, Ko J, Saridakis S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity and association with overall survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:364-372

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:445-454.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are chronic skin disorders characterized by purpura due to extravasation of blood from capillaries; the resulting hemosiderin deposition leads to pigmentation.7 There are various forms of PPD, which are classified into groups based on clinical appearance including Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and others including eczematid and itching variants, which some consider to be distinct entities. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi is the specific PPD that should be included in the clinical differential for PCFCL because it presents as annular patches with telangiectasias. Histologically, PPDs are characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis with extravasated red blood cells and the presence of hemosiderin mostly within macrophages and a lack of true vasculitis. Clonality of the T cells has been shown, and there is some evidence that PPD may overlap with mycosis fungoides. However, this overlap mainly has been seen in patients with widespread lesions and would not apply to this case. In general, patients with PPD can be reassured of the benign process. In cases of widespread PPD, patients should be followed clinically to assess for progression to mycosis fungoides, though the likelihood is low.7

Our patient underwent a full staging workup, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCFCL. He was treated with radiation to the forehead that resulted in clearance of the lesion. Approximately 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was alive and well with no evidence of recurrence of PCFCL.

In conclusion, it is imperative to identify unusual, macular, vascular-appearing patches, especially on the head and neck in older individuals. Because the clinical presentations of PCFCL, angiosarcoma, rosacea, MCC, and PPD can overlap with one another as well as with other entities, it is necessary to have a high level of suspicion and low threshold to biopsy these types of lesions, as outcomes can be drastically different.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are chronic skin disorders characterized by purpura due to extravasation of blood from capillaries; the resulting hemosiderin deposition leads to pigmentation.7 There are various forms of PPD, which are classified into groups based on clinical appearance including Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and others including eczematid and itching variants, which some consider to be distinct entities. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi is the specific PPD that should be included in the clinical differential for PCFCL because it presents as annular patches with telangiectasias. Histologically, PPDs are characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis with extravasated red blood cells and the presence of hemosiderin mostly within macrophages and a lack of true vasculitis. Clonality of the T cells has been shown, and there is some evidence that PPD may overlap with mycosis fungoides. However, this overlap mainly has been seen in patients with widespread lesions and would not apply to this case. In general, patients with PPD can be reassured of the benign process. In cases of widespread PPD, patients should be followed clinically to assess for progression to mycosis fungoides, though the likelihood is low.7

Our patient underwent a full staging workup, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCFCL. He was treated with radiation to the forehead that resulted in clearance of the lesion. Approximately 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was alive and well with no evidence of recurrence of PCFCL.

In conclusion, it is imperative to identify unusual, macular, vascular-appearing patches, especially on the head and neck in older individuals. Because the clinical presentations of PCFCL, angiosarcoma, rosacea, MCC, and PPD can overlap with one another as well as with other entities, it is necessary to have a high level of suspicion and low threshold to biopsy these types of lesions, as outcomes can be drastically different.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Atypical clinical presentation of primary and secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) on the head characterized by macular lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1000-1006.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Conic RRZ, Ko J, Saridakis S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity and association with overall survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:364-372

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:445-454.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Atypical clinical presentation of primary and secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) on the head characterized by macular lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1000-1006.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Conic RRZ, Ko J, Saridakis S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity and association with overall survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:364-372

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:445-454.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

Widespread Purple Plaques

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

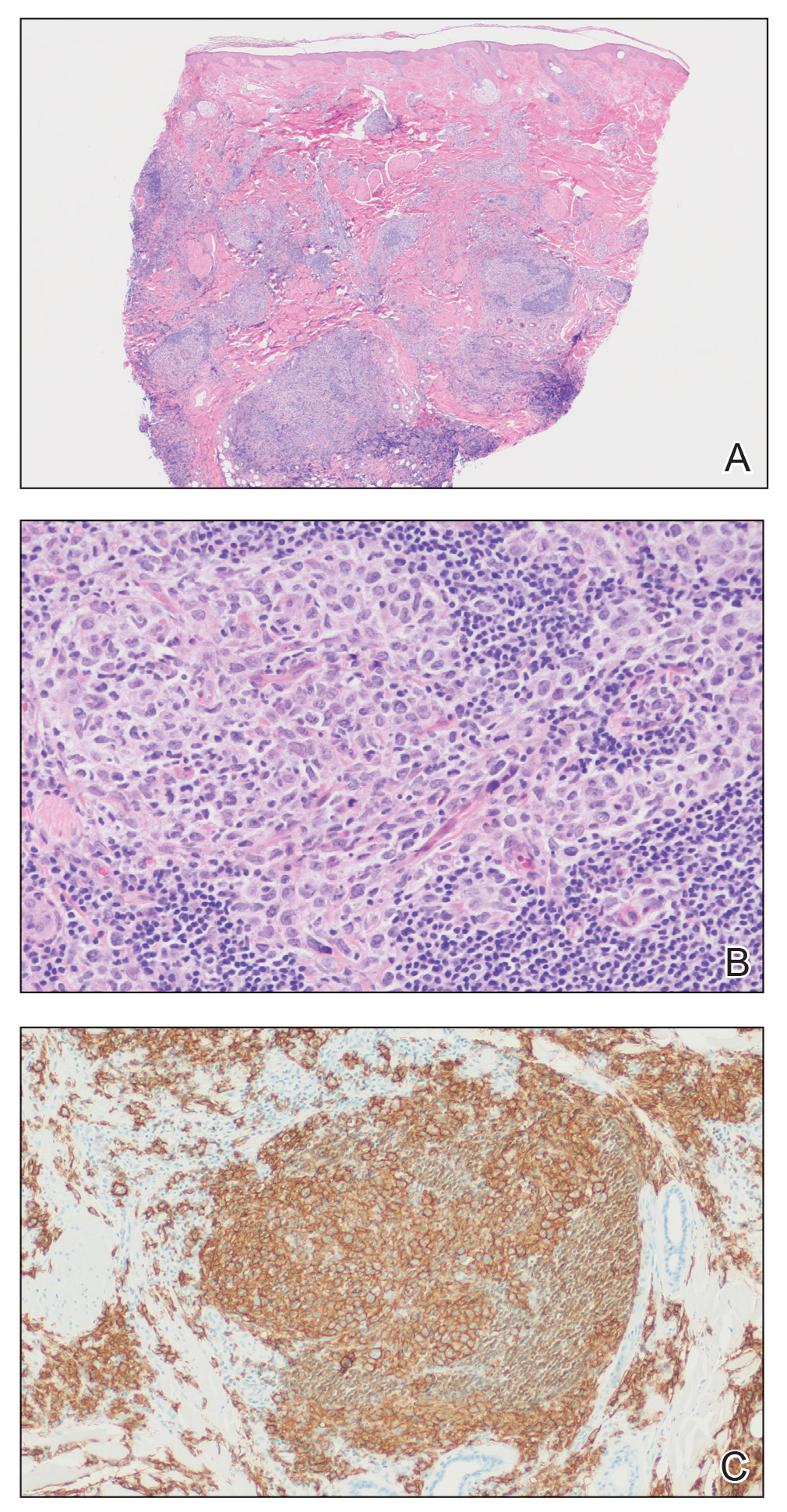

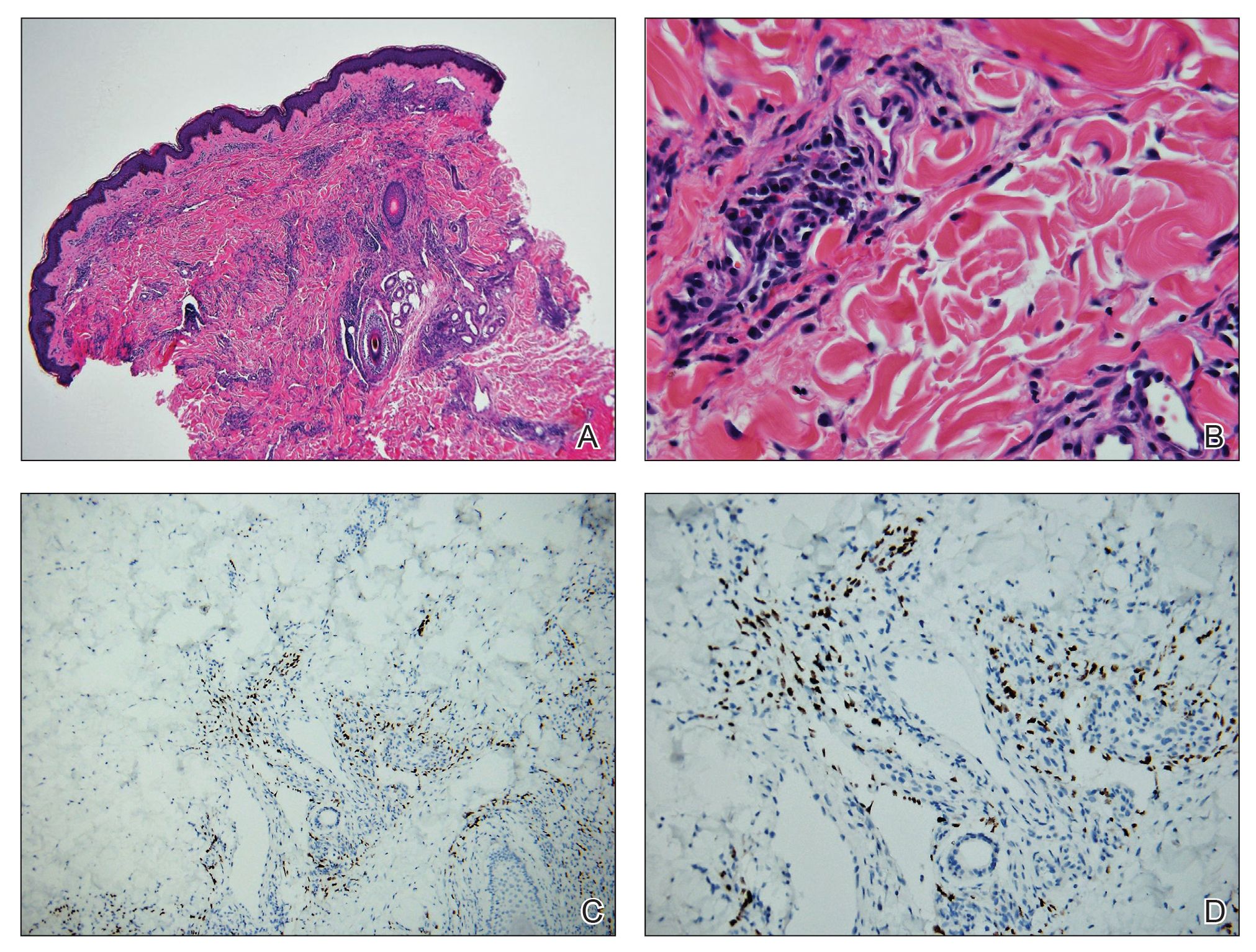

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), lichen planus pigmentosus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis. A laboratory workup was ordered, which included complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B autoantibodies, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the rash also was performed from the right upper back. Histology revealed a vascular proliferation that was diffusely positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 1). The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which time he revealed he had a history of homosexual relationships, with his last sexual contact being more than 1 year prior to presentation. The laboratory workup confirmed a diagnosis of HIV, and the remainder of the tests were unremarkable.

He was referred to our university's HIV clinic where he was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). His facial swelling worsened, leading to hospital admission. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed diffuse lymphadenopathy and lung nodules concerning for visceral involvement of KS. Hematology and oncology was consulted for further evaluation, and he was treated with 6 cycles of doxorubicin 20 mg/m2, which led to resolution of the lung nodules on CT and improvement of the rash burden. He was then started on alitretinoin gel 0.1% twice daily, which led to continued slow improvement (Figure 2).

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that occurs from infection with HHV-8. It typically presents as painless, reddish to violaceous macules or patches involving the skin and mucosa that often progress to plaques or nodules with possible visceral involvement. Kaposi sarcoma is classified into 4 subtypes based on epidemiology and clinical presentation: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1,2

Classic KS primarily affects elderly males of Mediterranean or Eastern European descent, with a mean age of 64.1 years and a male to female ratio of 3 to 1. It has an indolent course and a strong predilection for the skin of the lower extremities. The endemic form occurs mainly in Africa and has a more aggressive course, especially the lymphadenopathic type that affects children younger than 10 years.3 Iatrogenic KS develops in immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients, and may regress if the immunosuppressive agent is stopped.1 Kaposi sarcoma is an AIDS-defining illness and is the most common malignancy in AIDS patients. It is strongly associated with a low CD4 count, which accounts for the notable decline in its incidence after the widespread introduction of HAART.1 Among HIV patients, KS has the highest incidence in men who have sex with men. This population has a higher seroprevalence of HHV-8, which suggests possible sexual transmission of HHV-8. AIDS-associated KS most commonly involves the lower extremities, face, and oral mucosa. It may have visceral involvement, particularly of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems, which carries a poor prognosis.4,5

Approximately 40% of patients presenting with KS have gastrointestinal tract involvement.6 Of these patients, up to 80% are asymptomatic, with diagnosis usually being made on endoscopy.7 In contrast, pulmonary KS is less common and typically is symptomatic. It can involve the lung parenchyma, airways, or pleura and is diagnosed by chest radiography or CT scans. Glucocorticoid therapy is a known trigger for pulmonary KS exacerbation.8

All 4 subtypes share the same histopathologic findings consisting of spindled endothelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are CD34 and CD31 positive but are factor VIII negative. Staining for HHV-8 antigen is used to confirm the diagnosis. The inflammatory infiltrate predominantly is lymphocytic with scattered plasma cells.9

The laboratory results and histopathologic findings clearly indicated a diagnosis of KS in our patient. Other entities in the clinical differential would have shown notably different histopathologic findings and laboratory results. Lichen planus pigmentosus displays a lichenoid infiltrate and pigment dropout on histology. Histologic findings of psoriasis include psoriasiform acanthosis, dilated vessels in the dermal papillae, thinning of suprapapillary plates, and neutrophilic microabscesses. Sarcoidosis would demonstrate naked granulomas on histopathology. Syphilis displays variable but often psoriasiform or lichenoid findings on histology, and a positive rapid plasma reagin also would be noted.

First-line treatment of AIDS-related KS is HAART. For patients with severe and rapidly progressive KS or with visceral involvement, cytotoxic chemotherapy with doxorubicin or taxanes often is required. Additional therapies include radiotherapy, topical alitretinoin, and cryotherapy.1,10

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207-208.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:239-250.

- Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123-128.

- Smith NA, Sabin CA, Gopal R, et al. Serologic evidence of human herpesvirus 8 transmission by homosexual but not heterosexual sex. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:600-606.

- Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:459-462.

- Parente F, Cernuschi M, Orlando G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS: frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its effect on survival. a prospective study in a heterogeneous population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1007-1012.

- Gasparetto TD, Marchiori E, Lourenco S, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Regnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), lichen planus pigmentosus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis. A laboratory workup was ordered, which included complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B autoantibodies, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the rash also was performed from the right upper back. Histology revealed a vascular proliferation that was diffusely positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 1). The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which time he revealed he had a history of homosexual relationships, with his last sexual contact being more than 1 year prior to presentation. The laboratory workup confirmed a diagnosis of HIV, and the remainder of the tests were unremarkable.

He was referred to our university's HIV clinic where he was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). His facial swelling worsened, leading to hospital admission. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed diffuse lymphadenopathy and lung nodules concerning for visceral involvement of KS. Hematology and oncology was consulted for further evaluation, and he was treated with 6 cycles of doxorubicin 20 mg/m2, which led to resolution of the lung nodules on CT and improvement of the rash burden. He was then started on alitretinoin gel 0.1% twice daily, which led to continued slow improvement (Figure 2).

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that occurs from infection with HHV-8. It typically presents as painless, reddish to violaceous macules or patches involving the skin and mucosa that often progress to plaques or nodules with possible visceral involvement. Kaposi sarcoma is classified into 4 subtypes based on epidemiology and clinical presentation: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1,2

Classic KS primarily affects elderly males of Mediterranean or Eastern European descent, with a mean age of 64.1 years and a male to female ratio of 3 to 1. It has an indolent course and a strong predilection for the skin of the lower extremities. The endemic form occurs mainly in Africa and has a more aggressive course, especially the lymphadenopathic type that affects children younger than 10 years.3 Iatrogenic KS develops in immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients, and may regress if the immunosuppressive agent is stopped.1 Kaposi sarcoma is an AIDS-defining illness and is the most common malignancy in AIDS patients. It is strongly associated with a low CD4 count, which accounts for the notable decline in its incidence after the widespread introduction of HAART.1 Among HIV patients, KS has the highest incidence in men who have sex with men. This population has a higher seroprevalence of HHV-8, which suggests possible sexual transmission of HHV-8. AIDS-associated KS most commonly involves the lower extremities, face, and oral mucosa. It may have visceral involvement, particularly of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems, which carries a poor prognosis.4,5

Approximately 40% of patients presenting with KS have gastrointestinal tract involvement.6 Of these patients, up to 80% are asymptomatic, with diagnosis usually being made on endoscopy.7 In contrast, pulmonary KS is less common and typically is symptomatic. It can involve the lung parenchyma, airways, or pleura and is diagnosed by chest radiography or CT scans. Glucocorticoid therapy is a known trigger for pulmonary KS exacerbation.8

All 4 subtypes share the same histopathologic findings consisting of spindled endothelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are CD34 and CD31 positive but are factor VIII negative. Staining for HHV-8 antigen is used to confirm the diagnosis. The inflammatory infiltrate predominantly is lymphocytic with scattered plasma cells.9

The laboratory results and histopathologic findings clearly indicated a diagnosis of KS in our patient. Other entities in the clinical differential would have shown notably different histopathologic findings and laboratory results. Lichen planus pigmentosus displays a lichenoid infiltrate and pigment dropout on histology. Histologic findings of psoriasis include psoriasiform acanthosis, dilated vessels in the dermal papillae, thinning of suprapapillary plates, and neutrophilic microabscesses. Sarcoidosis would demonstrate naked granulomas on histopathology. Syphilis displays variable but often psoriasiform or lichenoid findings on histology, and a positive rapid plasma reagin also would be noted.

First-line treatment of AIDS-related KS is HAART. For patients with severe and rapidly progressive KS or with visceral involvement, cytotoxic chemotherapy with doxorubicin or taxanes often is required. Additional therapies include radiotherapy, topical alitretinoin, and cryotherapy.1,10

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), lichen planus pigmentosus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis. A laboratory workup was ordered, which included complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B autoantibodies, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the rash also was performed from the right upper back. Histology revealed a vascular proliferation that was diffusely positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 1). The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which time he revealed he had a history of homosexual relationships, with his last sexual contact being more than 1 year prior to presentation. The laboratory workup confirmed a diagnosis of HIV, and the remainder of the tests were unremarkable.

He was referred to our university's HIV clinic where he was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). His facial swelling worsened, leading to hospital admission. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed diffuse lymphadenopathy and lung nodules concerning for visceral involvement of KS. Hematology and oncology was consulted for further evaluation, and he was treated with 6 cycles of doxorubicin 20 mg/m2, which led to resolution of the lung nodules on CT and improvement of the rash burden. He was then started on alitretinoin gel 0.1% twice daily, which led to continued slow improvement (Figure 2).

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that occurs from infection with HHV-8. It typically presents as painless, reddish to violaceous macules or patches involving the skin and mucosa that often progress to plaques or nodules with possible visceral involvement. Kaposi sarcoma is classified into 4 subtypes based on epidemiology and clinical presentation: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1,2

Classic KS primarily affects elderly males of Mediterranean or Eastern European descent, with a mean age of 64.1 years and a male to female ratio of 3 to 1. It has an indolent course and a strong predilection for the skin of the lower extremities. The endemic form occurs mainly in Africa and has a more aggressive course, especially the lymphadenopathic type that affects children younger than 10 years.3 Iatrogenic KS develops in immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients, and may regress if the immunosuppressive agent is stopped.1 Kaposi sarcoma is an AIDS-defining illness and is the most common malignancy in AIDS patients. It is strongly associated with a low CD4 count, which accounts for the notable decline in its incidence after the widespread introduction of HAART.1 Among HIV patients, KS has the highest incidence in men who have sex with men. This population has a higher seroprevalence of HHV-8, which suggests possible sexual transmission of HHV-8. AIDS-associated KS most commonly involves the lower extremities, face, and oral mucosa. It may have visceral involvement, particularly of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems, which carries a poor prognosis.4,5

Approximately 40% of patients presenting with KS have gastrointestinal tract involvement.6 Of these patients, up to 80% are asymptomatic, with diagnosis usually being made on endoscopy.7 In contrast, pulmonary KS is less common and typically is symptomatic. It can involve the lung parenchyma, airways, or pleura and is diagnosed by chest radiography or CT scans. Glucocorticoid therapy is a known trigger for pulmonary KS exacerbation.8

All 4 subtypes share the same histopathologic findings consisting of spindled endothelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are CD34 and CD31 positive but are factor VIII negative. Staining for HHV-8 antigen is used to confirm the diagnosis. The inflammatory infiltrate predominantly is lymphocytic with scattered plasma cells.9

The laboratory results and histopathologic findings clearly indicated a diagnosis of KS in our patient. Other entities in the clinical differential would have shown notably different histopathologic findings and laboratory results. Lichen planus pigmentosus displays a lichenoid infiltrate and pigment dropout on histology. Histologic findings of psoriasis include psoriasiform acanthosis, dilated vessels in the dermal papillae, thinning of suprapapillary plates, and neutrophilic microabscesses. Sarcoidosis would demonstrate naked granulomas on histopathology. Syphilis displays variable but often psoriasiform or lichenoid findings on histology, and a positive rapid plasma reagin also would be noted.

First-line treatment of AIDS-related KS is HAART. For patients with severe and rapidly progressive KS or with visceral involvement, cytotoxic chemotherapy with doxorubicin or taxanes often is required. Additional therapies include radiotherapy, topical alitretinoin, and cryotherapy.1,10

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207-208.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:239-250.

- Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123-128.

- Smith NA, Sabin CA, Gopal R, et al. Serologic evidence of human herpesvirus 8 transmission by homosexual but not heterosexual sex. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:600-606.

- Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:459-462.

- Parente F, Cernuschi M, Orlando G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS: frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its effect on survival. a prospective study in a heterogeneous population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1007-1012.

- Gasparetto TD, Marchiori E, Lourenco S, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Regnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207-208.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:239-250.

- Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123-128.

- Smith NA, Sabin CA, Gopal R, et al. Serologic evidence of human herpesvirus 8 transmission by homosexual but not heterosexual sex. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:600-606.

- Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:459-462.

- Parente F, Cernuschi M, Orlando G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS: frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its effect on survival. a prospective study in a heterogeneous population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1007-1012.

- Gasparetto TD, Marchiori E, Lourenco S, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Regnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

A 24-year-old Black man presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic rash on the face, chest, back, and arms that had been progressively spreading over the course of 3 months. He had some swelling of the lips prior to the onset of the rash and was prescribed prednisone 10 mg daily by an outside physician. He had no known medical problems and was taking no medications. Physical examination revealed numerous violaceous plaques scattered symmetrically on the trunk, arms, legs, and face. His family history was negative for autoimmune disease, and a review of systems was unremarkable. He denied any recent sexual contacts.

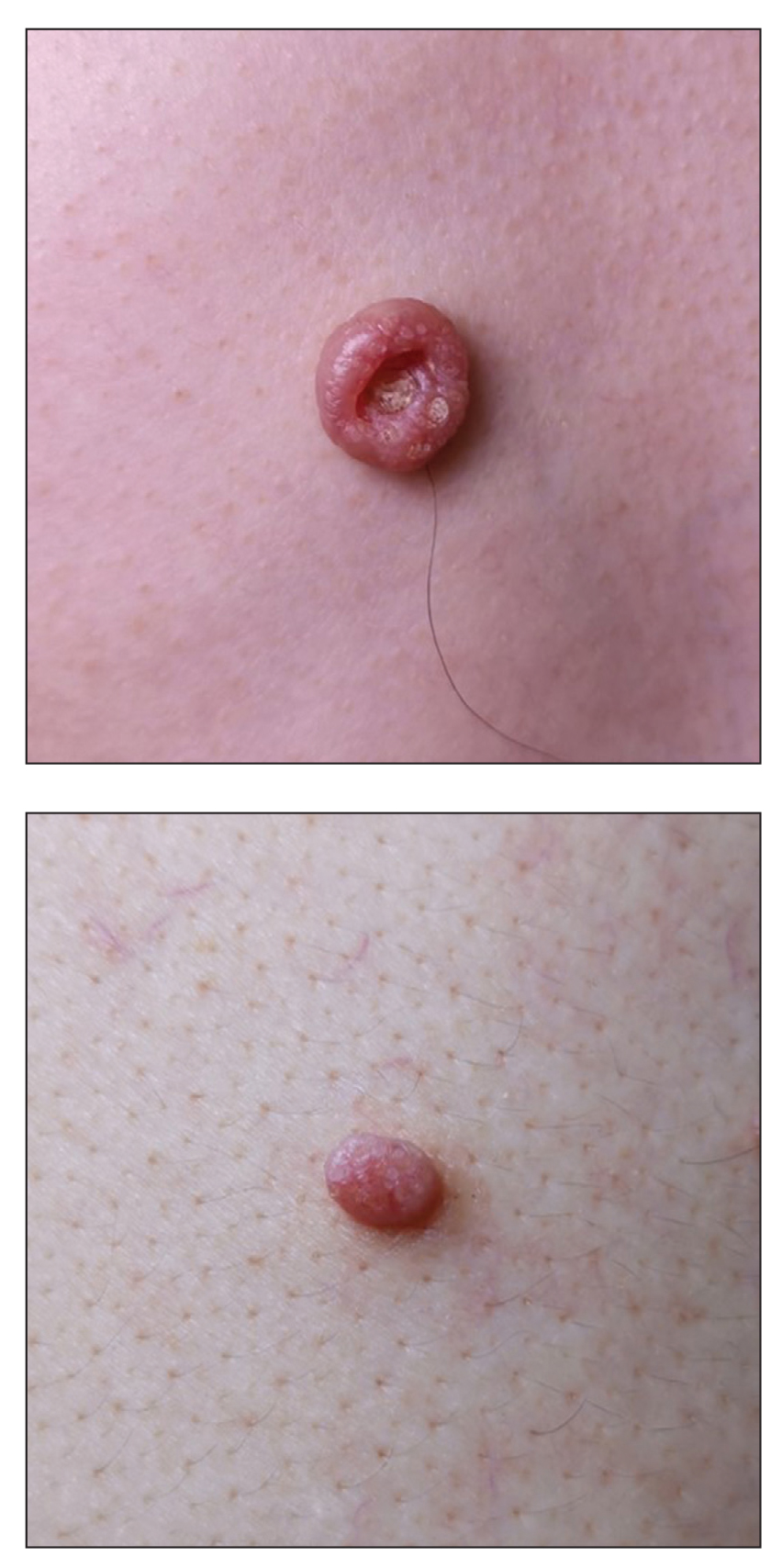

Umbilicated Keratotic Papule on the Scalp

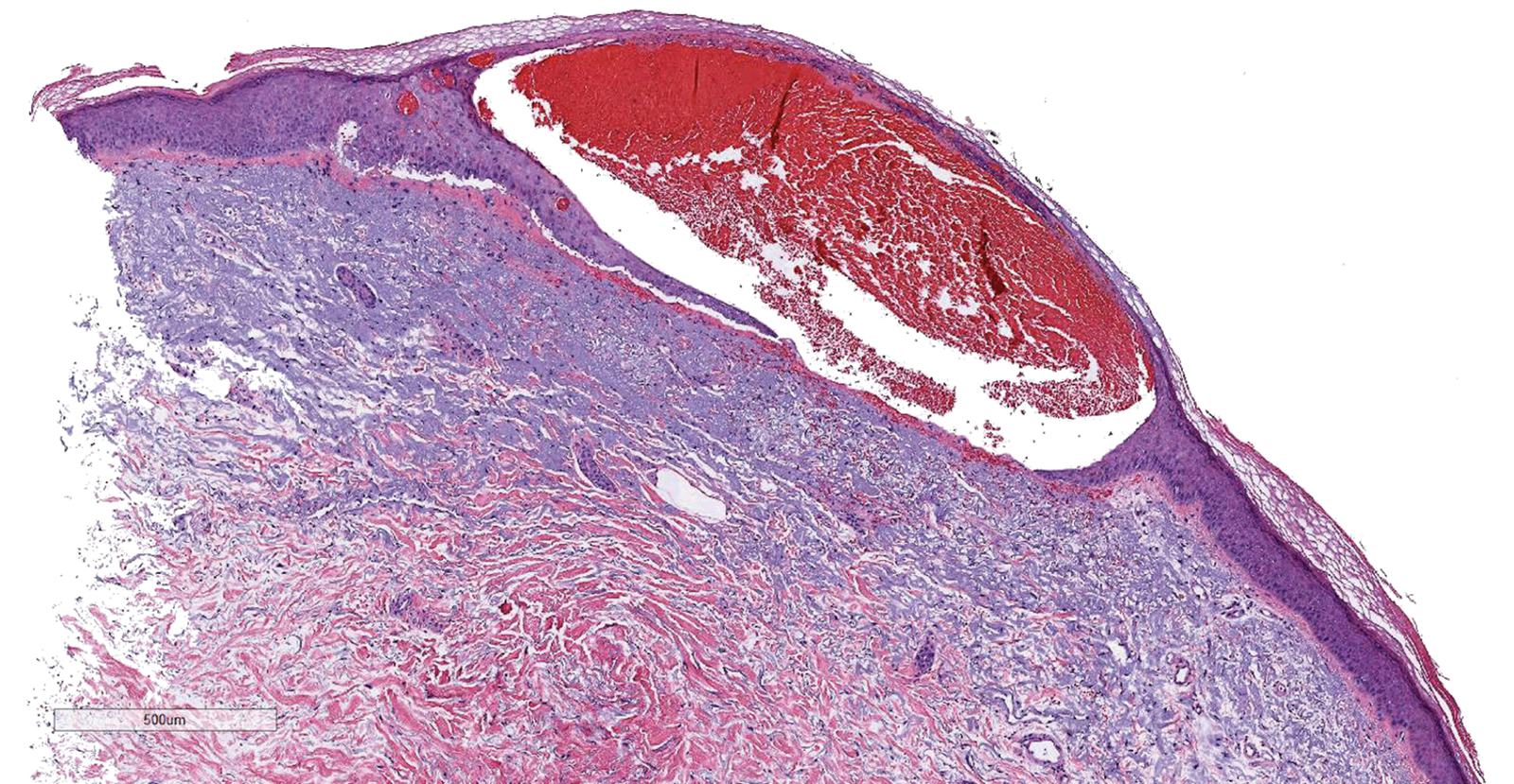

The Diagnosis: Warty Dyskeratoma

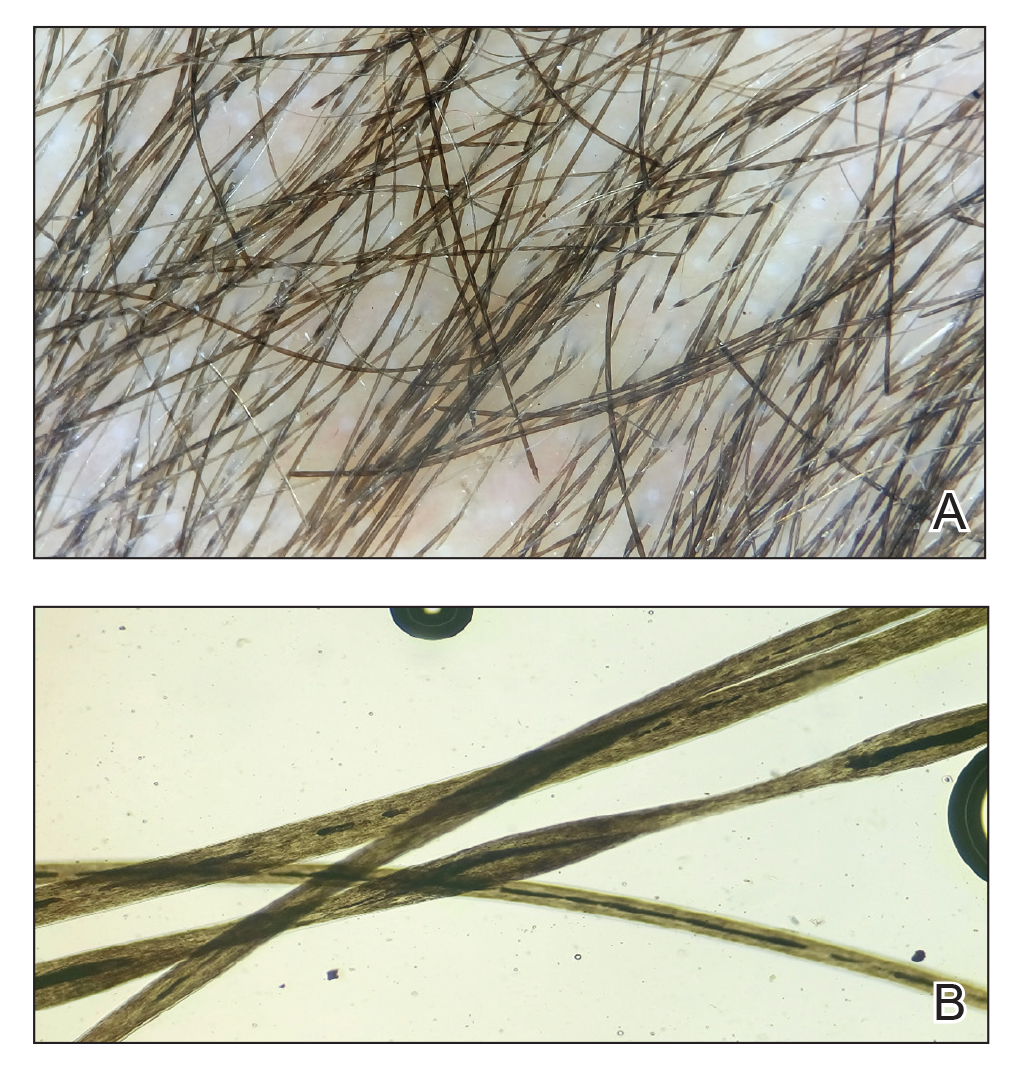

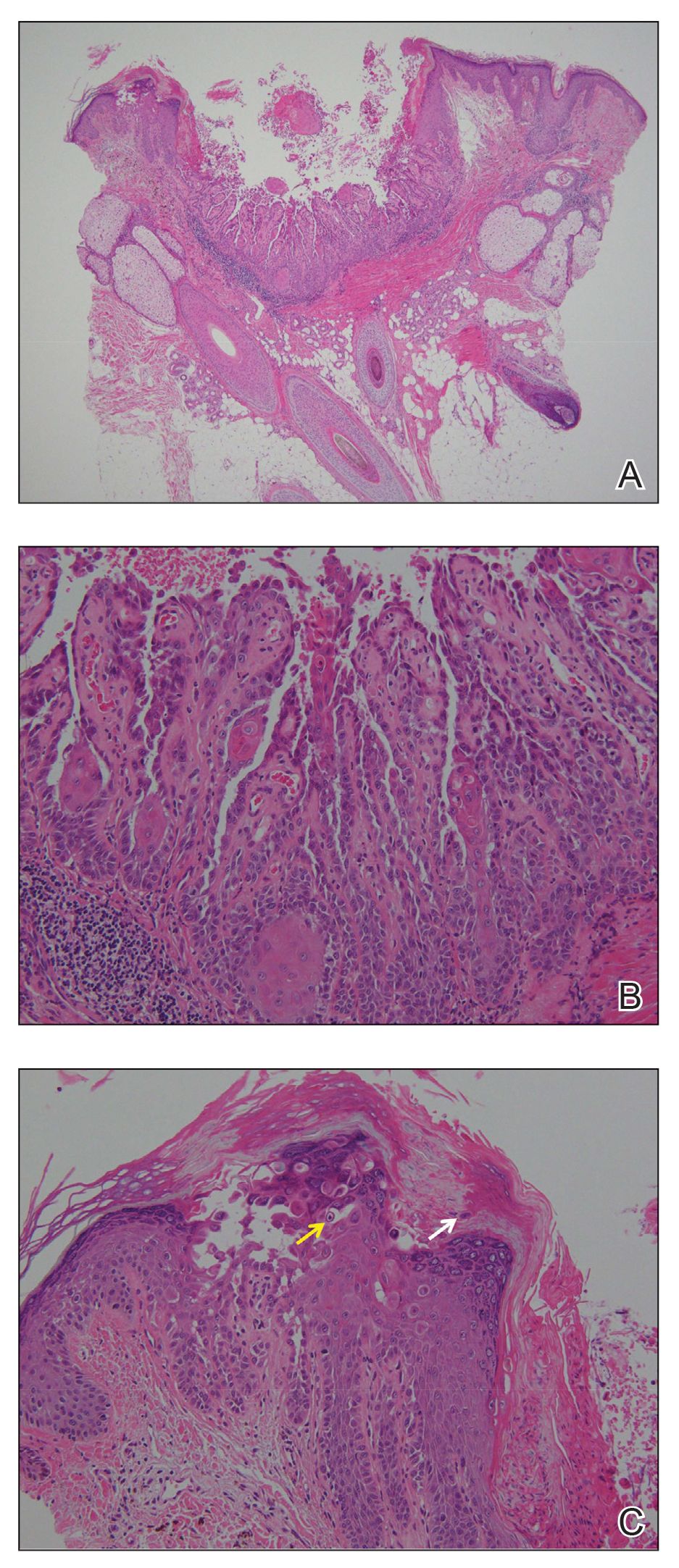

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign cutaneous tumor that was first described in 1954 as isolated Darier disease (DD). In 1957, Szymanski1 renamed it warty dyskeratoma as a distinct condition from DD. Warty dyskeratoma typically presents as a flesh-colored to brownish, round, well-demarcated, and slightly elevated papule or nodule accompanied by an umbilical invagination at the center. It most commonly arises on the scalp, face, or neck.2 In contrast to DD, familial occurrence is uncommon. It usually is difficult to distinguish WD from other conditions such as seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris, or keratoacanthoma due to its macroscopic features. Therefore, histopathologic investigation is necessary for a precise diagnosis.

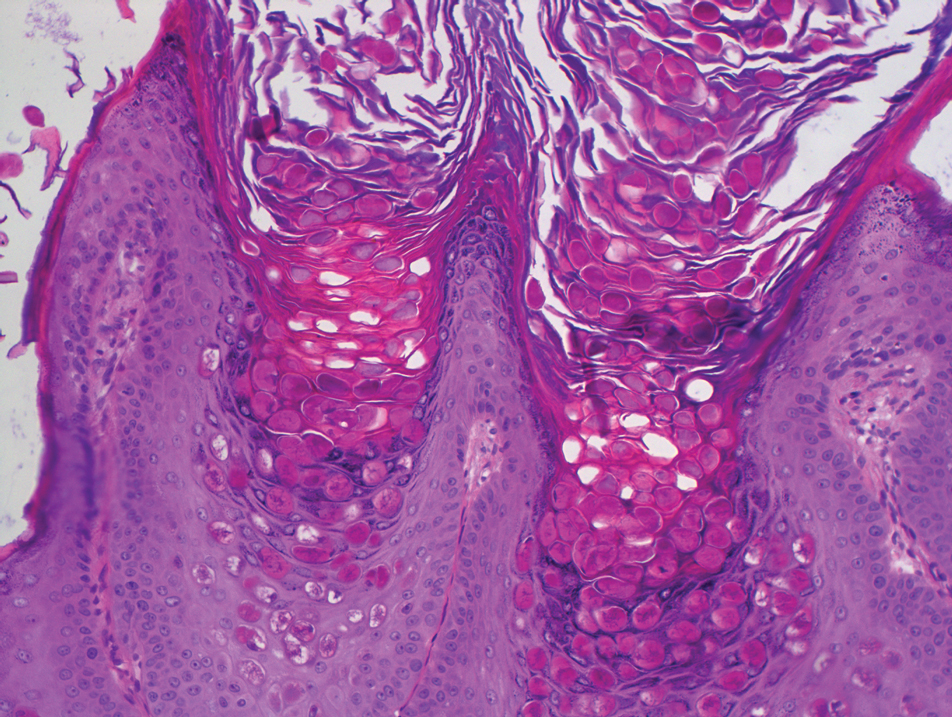

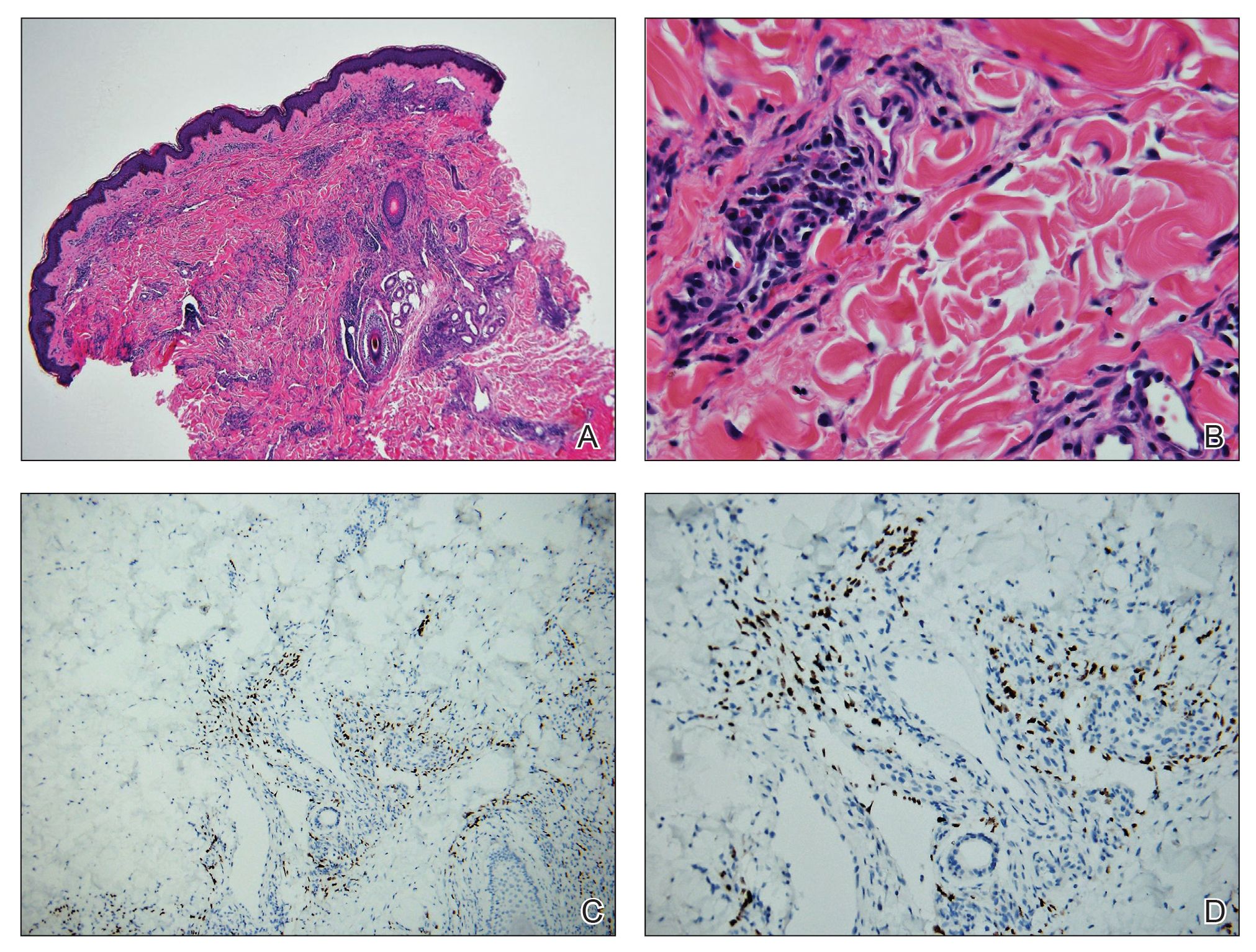

In our case, histologic investigation revealed a symmetric cup-shaped invagination filled with acantholytic and dyskeratotic keratinocytes with no atypia or mitotic figures (Figure, A). The bottom of the invagination was occupied with numerous villi covered by a single layer of basal cells (Figure, B). At the edge of the invagination, corps ronds and grains were observed in the granular and cornified layers, respectively (Figure, C).

The hallmark histopathologic findings are acantholysis and dyskeratosis just above the basal cell layer, called focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. The differential diagnosis includes other disorders associated with focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, such as DD and acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma.3 Distinguishing WD from DD may be difficult in rare cases with multiple lesions.4 In such cases, an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern and younger age of onset should prompt clinicians to seek for mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2, for the diagnosis of DD.5 Additionally, the presence of atypia or mitotic figures will rule out malignant disorders such as squamous cell carcinoma.

Although the pathogenesis of WD is not fully understood, most clinicians consider it a follicular adnexal neoplasm because the lesions often are connected to the pilosebaceous unit on microscopic observation.6 Although WD-like lesions arising from the oral mucosa have been reported,7 their etiology may be different from WD because the oral mucosa lacks hair follicles.8 The term warty leads to speculation of the contribution of human papillomavirus to the pathogenesis of WD, but this has been questioned due to the negative result of viral DNA detection from WD lesions by polymerase chain reaction analysis.2 Therefore, the term follicular dyskeratoma has been suggested as a novel denomination that reflects its etiology more precisely.2

The efficacy of topical treatment has not yet been established. Cryosurgery is another therapeutic option, but it sometimes fails.9 As performed in our patient, excisional biopsy is the most reasonable treatment option to obtain both complete removal and precise diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Warty Dyskeratoma

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign cutaneous tumor that was first described in 1954 as isolated Darier disease (DD). In 1957, Szymanski1 renamed it warty dyskeratoma as a distinct condition from DD. Warty dyskeratoma typically presents as a flesh-colored to brownish, round, well-demarcated, and slightly elevated papule or nodule accompanied by an umbilical invagination at the center. It most commonly arises on the scalp, face, or neck.2 In contrast to DD, familial occurrence is uncommon. It usually is difficult to distinguish WD from other conditions such as seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris, or keratoacanthoma due to its macroscopic features. Therefore, histopathologic investigation is necessary for a precise diagnosis.

In our case, histologic investigation revealed a symmetric cup-shaped invagination filled with acantholytic and dyskeratotic keratinocytes with no atypia or mitotic figures (Figure, A). The bottom of the invagination was occupied with numerous villi covered by a single layer of basal cells (Figure, B). At the edge of the invagination, corps ronds and grains were observed in the granular and cornified layers, respectively (Figure, C).

The hallmark histopathologic findings are acantholysis and dyskeratosis just above the basal cell layer, called focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. The differential diagnosis includes other disorders associated with focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, such as DD and acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma.3 Distinguishing WD from DD may be difficult in rare cases with multiple lesions.4 In such cases, an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern and younger age of onset should prompt clinicians to seek for mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2, for the diagnosis of DD.5 Additionally, the presence of atypia or mitotic figures will rule out malignant disorders such as squamous cell carcinoma.

Although the pathogenesis of WD is not fully understood, most clinicians consider it a follicular adnexal neoplasm because the lesions often are connected to the pilosebaceous unit on microscopic observation.6 Although WD-like lesions arising from the oral mucosa have been reported,7 their etiology may be different from WD because the oral mucosa lacks hair follicles.8 The term warty leads to speculation of the contribution of human papillomavirus to the pathogenesis of WD, but this has been questioned due to the negative result of viral DNA detection from WD lesions by polymerase chain reaction analysis.2 Therefore, the term follicular dyskeratoma has been suggested as a novel denomination that reflects its etiology more precisely.2

The efficacy of topical treatment has not yet been established. Cryosurgery is another therapeutic option, but it sometimes fails.9 As performed in our patient, excisional biopsy is the most reasonable treatment option to obtain both complete removal and precise diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Warty Dyskeratoma

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign cutaneous tumor that was first described in 1954 as isolated Darier disease (DD). In 1957, Szymanski1 renamed it warty dyskeratoma as a distinct condition from DD. Warty dyskeratoma typically presents as a flesh-colored to brownish, round, well-demarcated, and slightly elevated papule or nodule accompanied by an umbilical invagination at the center. It most commonly arises on the scalp, face, or neck.2 In contrast to DD, familial occurrence is uncommon. It usually is difficult to distinguish WD from other conditions such as seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris, or keratoacanthoma due to its macroscopic features. Therefore, histopathologic investigation is necessary for a precise diagnosis.

In our case, histologic investigation revealed a symmetric cup-shaped invagination filled with acantholytic and dyskeratotic keratinocytes with no atypia or mitotic figures (Figure, A). The bottom of the invagination was occupied with numerous villi covered by a single layer of basal cells (Figure, B). At the edge of the invagination, corps ronds and grains were observed in the granular and cornified layers, respectively (Figure, C).

The hallmark histopathologic findings are acantholysis and dyskeratosis just above the basal cell layer, called focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. The differential diagnosis includes other disorders associated with focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, such as DD and acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma.3 Distinguishing WD from DD may be difficult in rare cases with multiple lesions.4 In such cases, an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern and younger age of onset should prompt clinicians to seek for mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2, for the diagnosis of DD.5 Additionally, the presence of atypia or mitotic figures will rule out malignant disorders such as squamous cell carcinoma.

Although the pathogenesis of WD is not fully understood, most clinicians consider it a follicular adnexal neoplasm because the lesions often are connected to the pilosebaceous unit on microscopic observation.6 Although WD-like lesions arising from the oral mucosa have been reported,7 their etiology may be different from WD because the oral mucosa lacks hair follicles.8 The term warty leads to speculation of the contribution of human papillomavirus to the pathogenesis of WD, but this has been questioned due to the negative result of viral DNA detection from WD lesions by polymerase chain reaction analysis.2 Therefore, the term follicular dyskeratoma has been suggested as a novel denomination that reflects its etiology more precisely.2

The efficacy of topical treatment has not yet been established. Cryosurgery is another therapeutic option, but it sometimes fails.9 As performed in our patient, excisional biopsy is the most reasonable treatment option to obtain both complete removal and precise diagnosis.

A 72-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a solitary papule on the scalp measuring 3.2 mm in diameter with a keratotic umbilicated center of 1 year’s duration. His medical history included acute appendicitis. Treatment with fusidic acid ointment 2% was unsuccessful. The papule was hard without tenderness on palpation. An excisional biopsy was performed under local anesthesia.

Inverse Distribution of Pink Macules and Patches

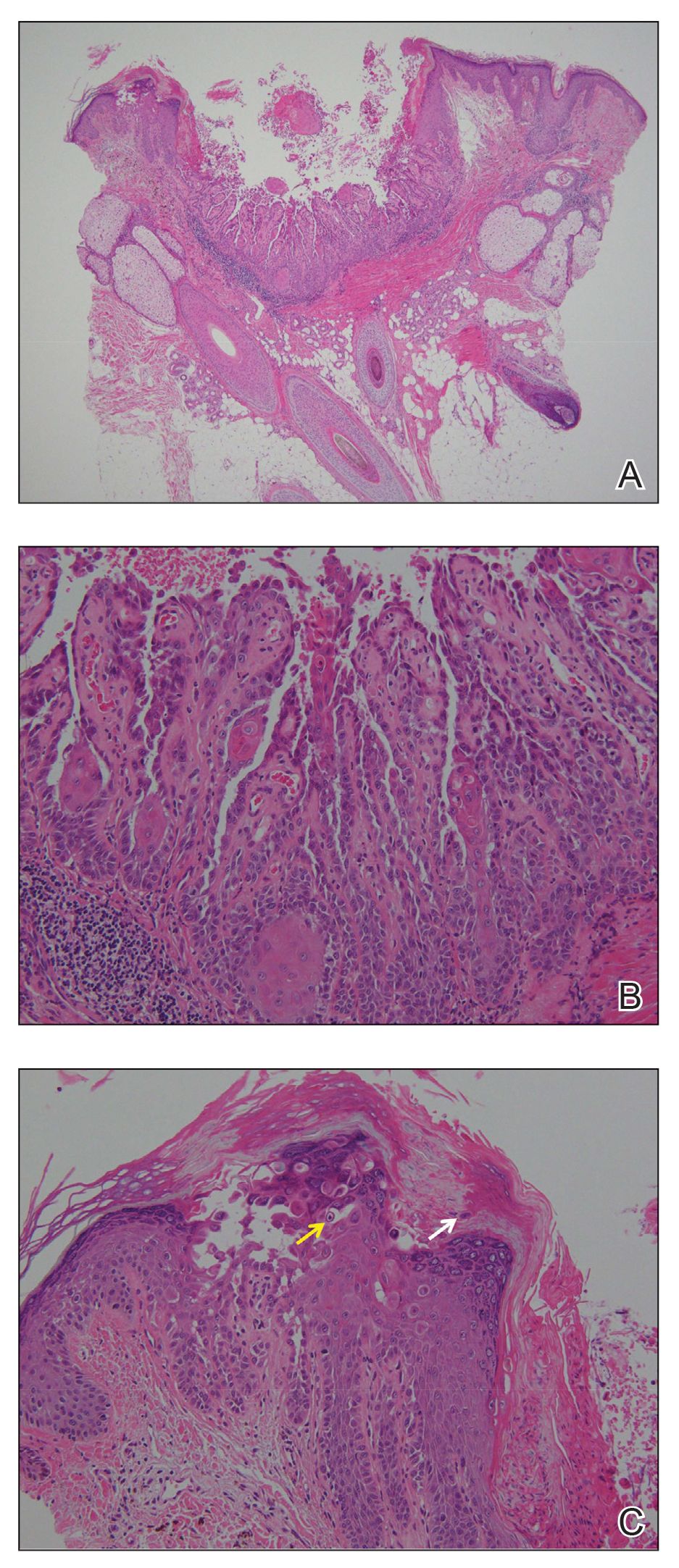

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

A 73-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic progressive rash on the left wrist, waist, groin, and inner thighs of 2 months’ duration. Her primary care provider prescribed clotrimazole and fluconazole with no improvement. Review of systems was negative. Medications included omeprazole, candesartan hydrochlorothiazide, potassium chloride, and levothyroxine. Physical examination revealed many scattered, pink to violaceous macules and patches in the axillae (sparing the vaults) and inguinal folds as well as on the waist and medial upper thighs. The lesions were without scale or other epidermal change. She also had a pink papule on the left volar wrist. A Wood lamp examination was unremarkable, and punch biopsies were performed.

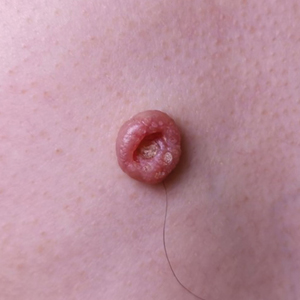

Umbilicated Neoplasm on the Chest

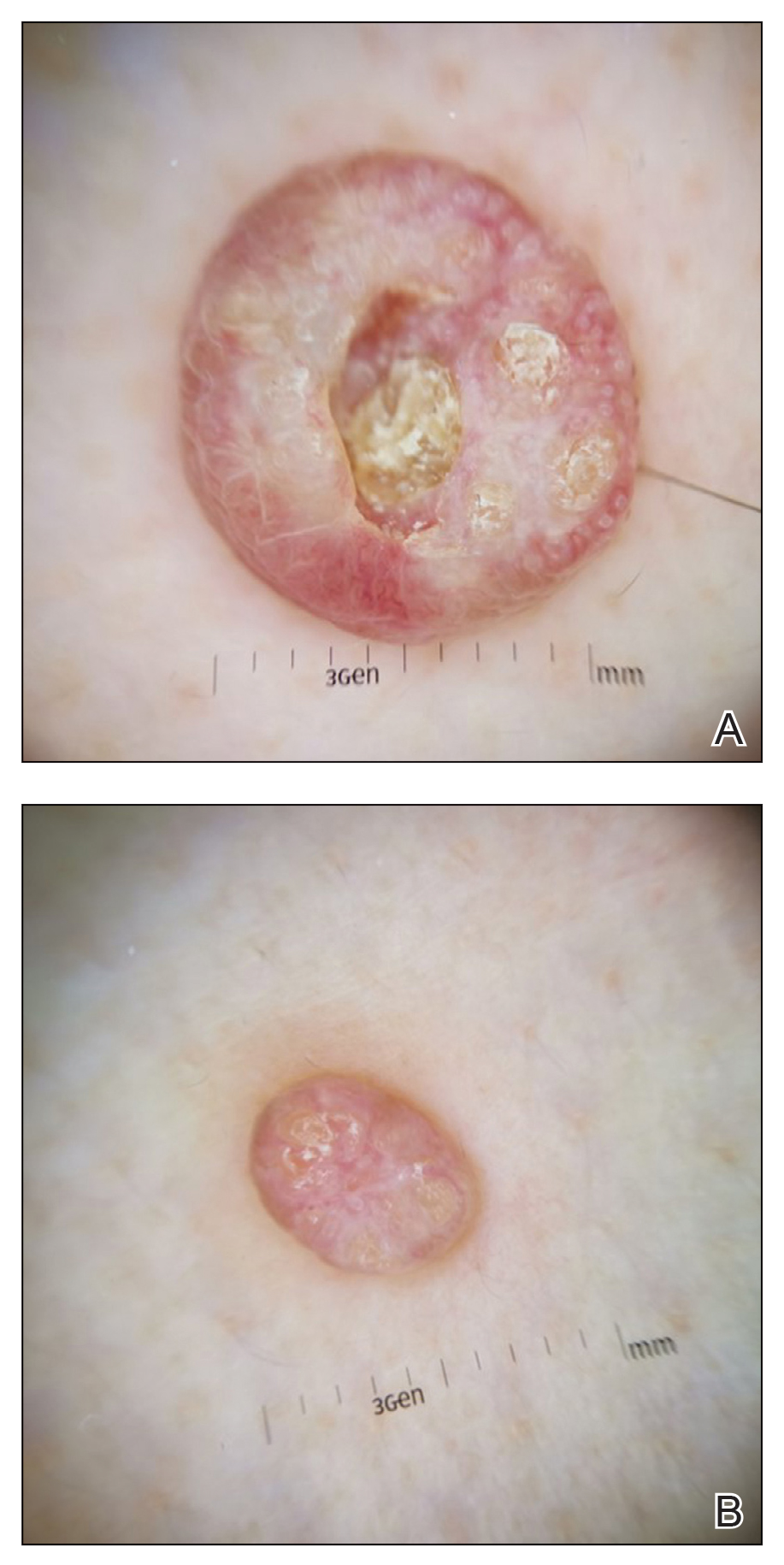

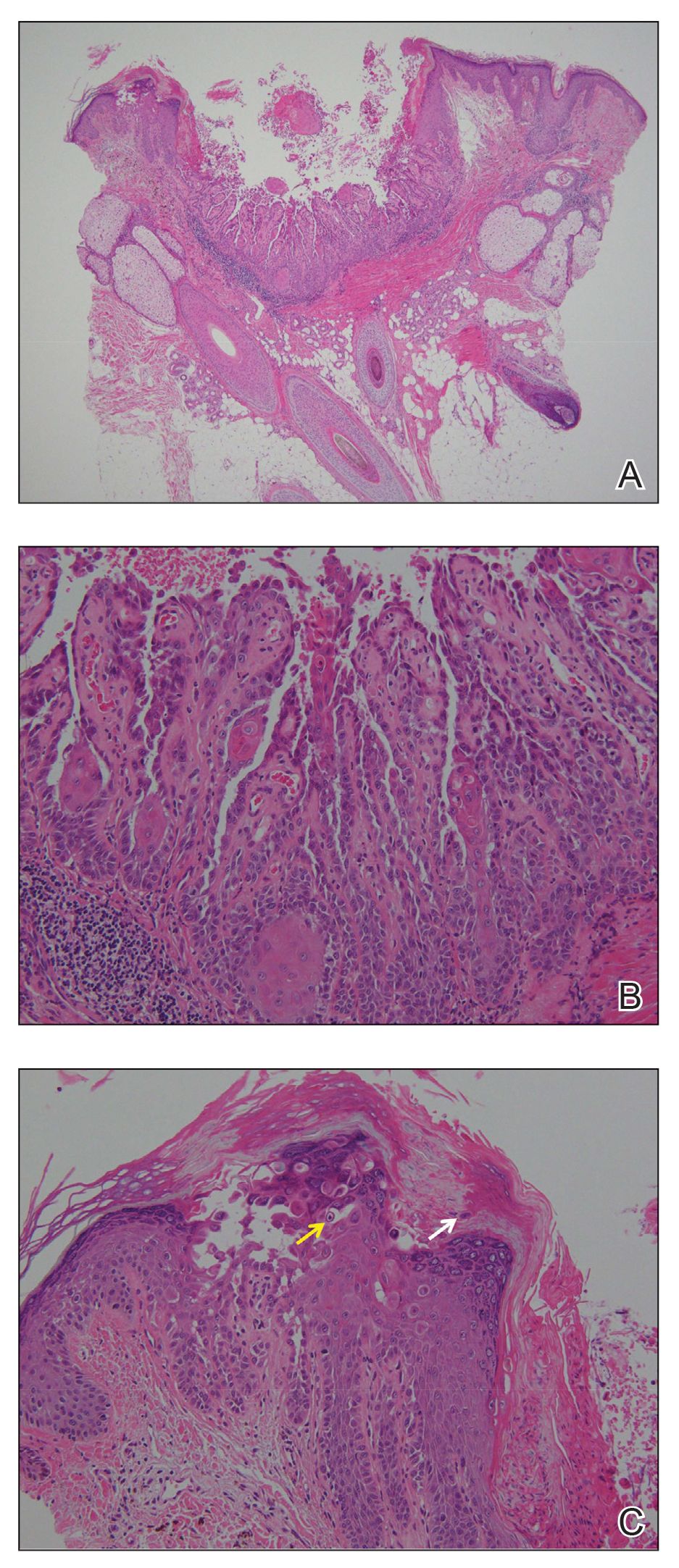

Dermoscopy showed polylobular, whitish yellow, amorphous structures at the center of the lesion surrounded by a crown of vessels (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed hyperplastic crateriform lesions containing large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes (Figure 2). At follow-up 2 weeks after the biopsy, the patient presented with approximately 20 more reddish papules of varying sizes on the abdomen and back that presented as dome-shaped papules and had a typical umbilicated center. The clinical manifestations, dermoscopy, and pathology findings were consistent with molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum was first described in 1814. It is a benign cutaneous infectious disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus of the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum lesions usually manifest clinically as dome-shaped, flesh-colored or translucent, umbilicated papules measuring 1 to 5 mm in diameter that are commonly distributed over the face, trunk, and extremities and usually are self-limiting.1

Giant MC is rare and can be seen either in patients on immunosuppressive therapy or in those with diseases that can cause immunosuppression, such as human immunodeficiency virus, leukemia, atopic dermatitis, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and sarcoidosis. In these instances, MC often is greater than 1 cm in diameter. Atypical variants may have an eczematous presentation or a lesion with secondary abscess formation and also can be spread widely over the body.2 Due to these atypical appearances and large dimensions in immunocompromised patients, other dermatologic diseases should be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous horn, cutaneous cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and xanthomatosis.3

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included keratoacanthoma, which may present as a solitary, discrete, round to oval, flesh-colored, umbilicated nodule with a central keratin-filled crater and has a rapid clinical evolution, usually regressing within 4 to 6 months.

Squamous cell carcinoma may appear as scaly red patches, open sores, warts, or elevated growths with a central depression and may crust or bleed. Basal cell carcinoma typically may appear as a dome-shaped skin nodule with visible blood vessels or sometimes presents as a red patch similar to eczema. Xanthomatosis often appears as yellow to orange, mostly asymptomatic, supple patches or plaques, usually with sharp and distinctive edges.

Ancillary diagnostic modalities such as dermoscopy may be used to improve diagnostic accuracy. The best known capillaroscopic feature of MC is the peripheral crown of vessels in a radial distribution. A study of 258 MC lesions highlighted that crown and crown plus radial arrangements are the most common vascular structure patterns under dermoscopy. In addition, polylobular amorphous white structures in the center of the lesions tend to be a feature of larger MC papules.4 Histologically, MC shows lobulated crateriform lesions, thickening of the epidermis into the dermis, and the typical appearance of large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes.5

There are several treatment options available for MC. Common modalities include liquid nitrogen cryospray, curettage, and electrocauterization. In immunocompromised patients, MC lesions usually are resistant to ordinary therapy. The efficacy of topical agents such as imiquimod, which can induce high levels of IFN-α and other cytokines, has been demonstrated in these patients.6 Cidofovir, a nucleoside analog that has potent antiviral properties, also can be included as a therapeutic option.3 Our patient’s largest MC lesion was treated with surgical excision, the 2 large lesions on the left side of the chest with cryotherapy, and the other small lesions with curettage.

- Hanson D, Diven DG. Molluscum contagiosum. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:2.

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796.

- Mansur AT, Goktay F, Gunduz S, et al. Multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6:120-123.

- Ku SH, Cho EB, Park EJ, et al. Dermoscopic features of molluscum contagiosum based on white structures and their correlation with histopathological findings. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:208-210.

- Trčko K, Hošnjak L, Kušar B, et al. Clinical, histopathological, and virological evaluation of 203 patients with a clinical diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum [published online November 12, 2018]. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5.

- Gardner LS, Ormond PJ. Treatment of multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant patient with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;31:452-453.

Dermoscopy showed polylobular, whitish yellow, amorphous structures at the center of the lesion surrounded by a crown of vessels (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed hyperplastic crateriform lesions containing large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes (Figure 2). At follow-up 2 weeks after the biopsy, the patient presented with approximately 20 more reddish papules of varying sizes on the abdomen and back that presented as dome-shaped papules and had a typical umbilicated center. The clinical manifestations, dermoscopy, and pathology findings were consistent with molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum was first described in 1814. It is a benign cutaneous infectious disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus of the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum lesions usually manifest clinically as dome-shaped, flesh-colored or translucent, umbilicated papules measuring 1 to 5 mm in diameter that are commonly distributed over the face, trunk, and extremities and usually are self-limiting.1

Giant MC is rare and can be seen either in patients on immunosuppressive therapy or in those with diseases that can cause immunosuppression, such as human immunodeficiency virus, leukemia, atopic dermatitis, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and sarcoidosis. In these instances, MC often is greater than 1 cm in diameter. Atypical variants may have an eczematous presentation or a lesion with secondary abscess formation and also can be spread widely over the body.2 Due to these atypical appearances and large dimensions in immunocompromised patients, other dermatologic diseases should be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous horn, cutaneous cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and xanthomatosis.3

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included keratoacanthoma, which may present as a solitary, discrete, round to oval, flesh-colored, umbilicated nodule with a central keratin-filled crater and has a rapid clinical evolution, usually regressing within 4 to 6 months.

Squamous cell carcinoma may appear as scaly red patches, open sores, warts, or elevated growths with a central depression and may crust or bleed. Basal cell carcinoma typically may appear as a dome-shaped skin nodule with visible blood vessels or sometimes presents as a red patch similar to eczema. Xanthomatosis often appears as yellow to orange, mostly asymptomatic, supple patches or plaques, usually with sharp and distinctive edges.

Ancillary diagnostic modalities such as dermoscopy may be used to improve diagnostic accuracy. The best known capillaroscopic feature of MC is the peripheral crown of vessels in a radial distribution. A study of 258 MC lesions highlighted that crown and crown plus radial arrangements are the most common vascular structure patterns under dermoscopy. In addition, polylobular amorphous white structures in the center of the lesions tend to be a feature of larger MC papules.4 Histologically, MC shows lobulated crateriform lesions, thickening of the epidermis into the dermis, and the typical appearance of large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes.5

There are several treatment options available for MC. Common modalities include liquid nitrogen cryospray, curettage, and electrocauterization. In immunocompromised patients, MC lesions usually are resistant to ordinary therapy. The efficacy of topical agents such as imiquimod, which can induce high levels of IFN-α and other cytokines, has been demonstrated in these patients.6 Cidofovir, a nucleoside analog that has potent antiviral properties, also can be included as a therapeutic option.3 Our patient’s largest MC lesion was treated with surgical excision, the 2 large lesions on the left side of the chest with cryotherapy, and the other small lesions with curettage.

Dermoscopy showed polylobular, whitish yellow, amorphous structures at the center of the lesion surrounded by a crown of vessels (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed hyperplastic crateriform lesions containing large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies within keratinocytes (Figure 2). At follow-up 2 weeks after the biopsy, the patient presented with approximately 20 more reddish papules of varying sizes on the abdomen and back that presented as dome-shaped papules and had a typical umbilicated center. The clinical manifestations, dermoscopy, and pathology findings were consistent with molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum was first described in 1814. It is a benign cutaneous infectious disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus of the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum lesions usually manifest clinically as dome-shaped, flesh-colored or translucent, umbilicated papules measuring 1 to 5 mm in diameter that are commonly distributed over the face, trunk, and extremities and usually are self-limiting.1