User login

A Painful Flesh-Colored Papule on the Shoulder

A Painful Flesh-Colored Papule on the Shoulder

The Diagnosis: Leiomyoma

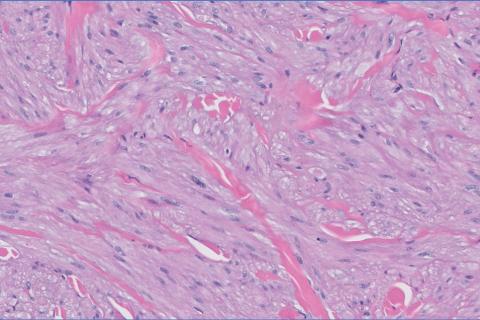

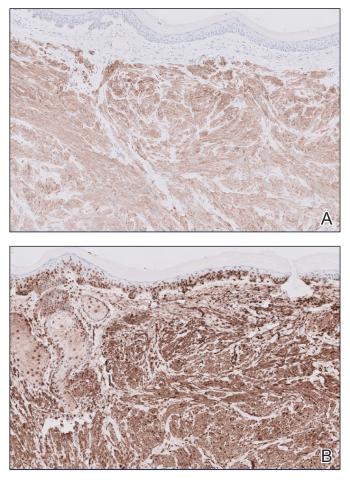

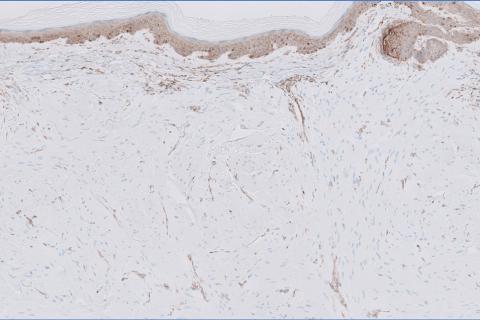

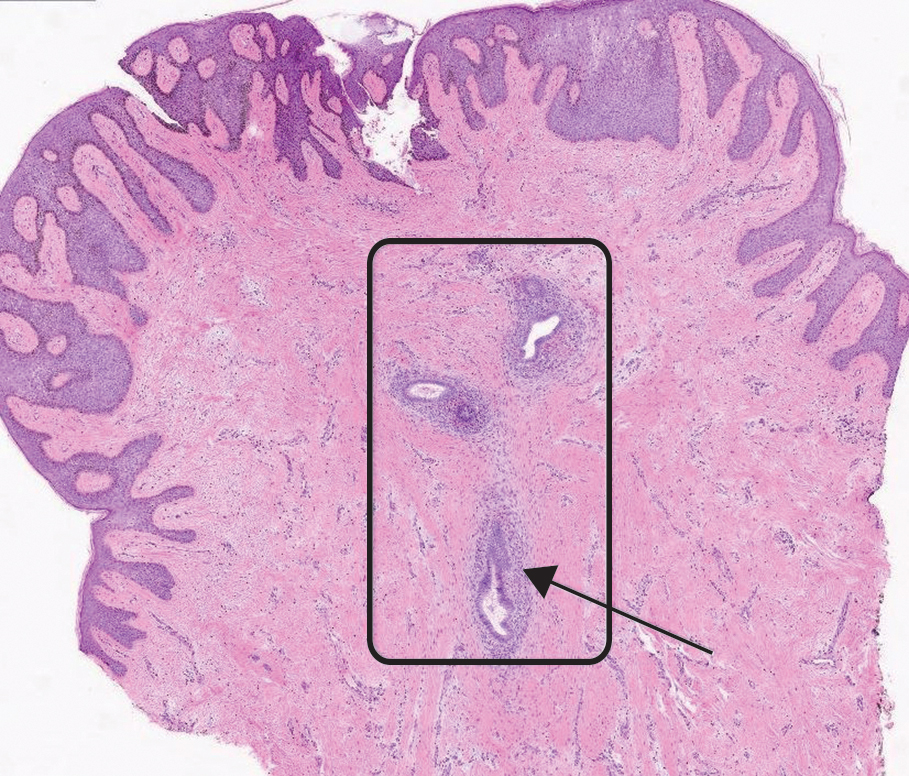

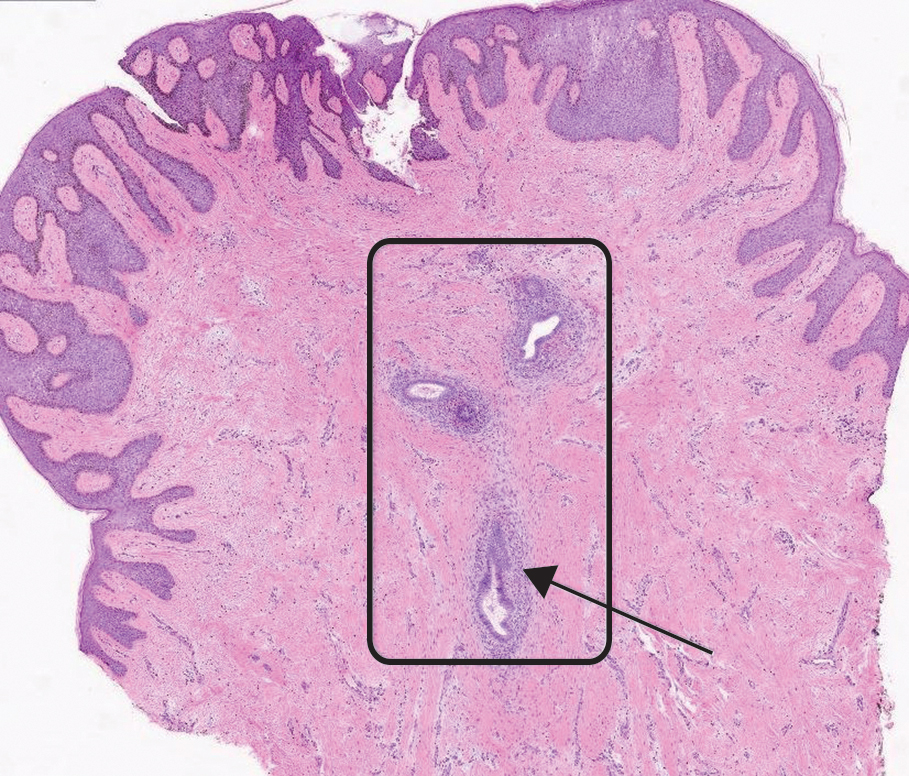

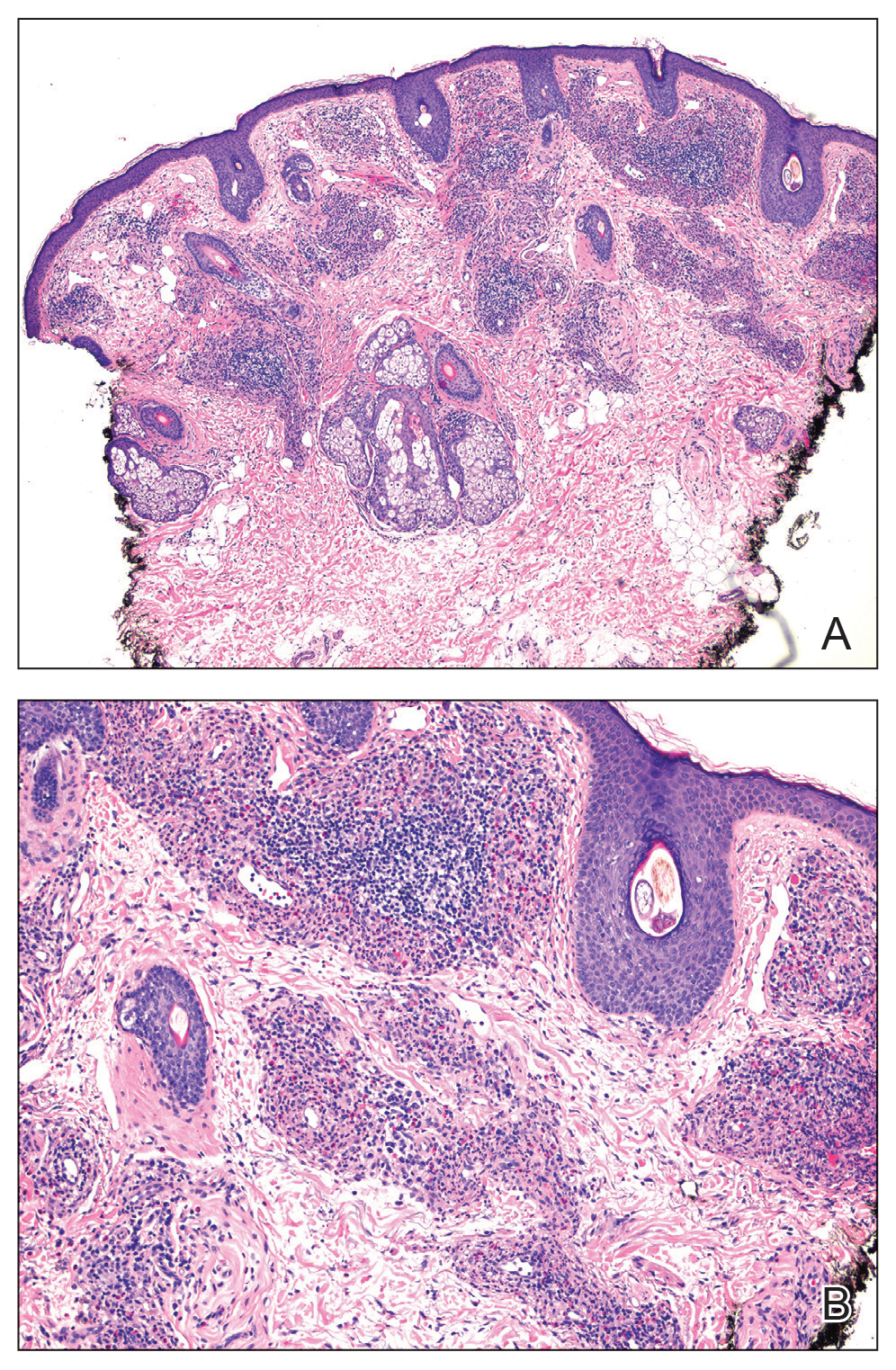

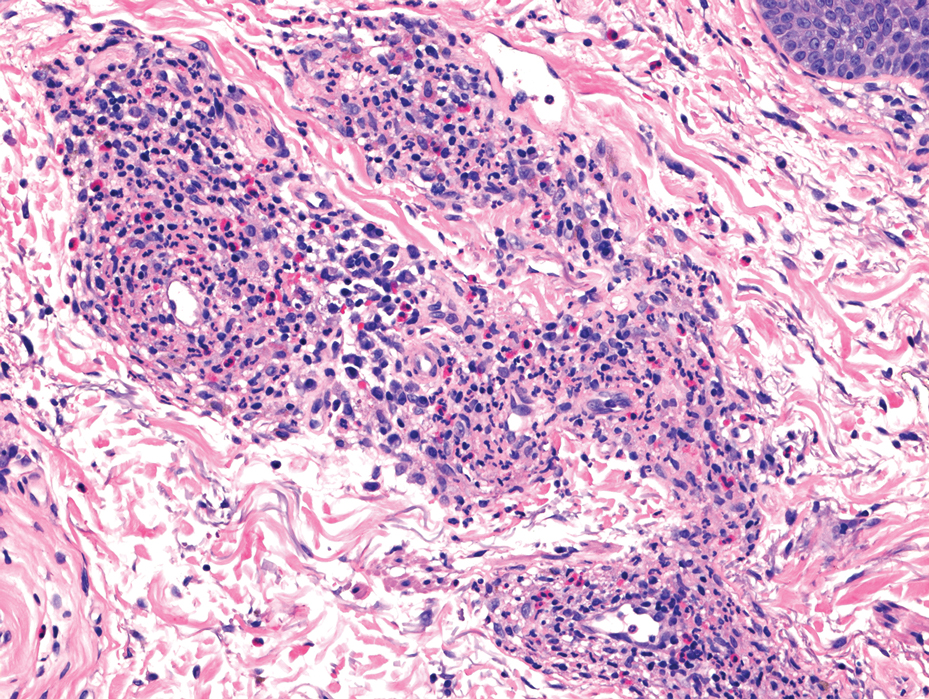

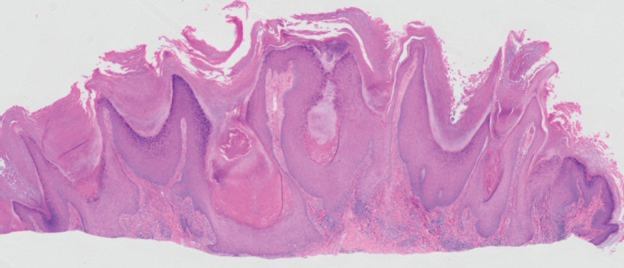

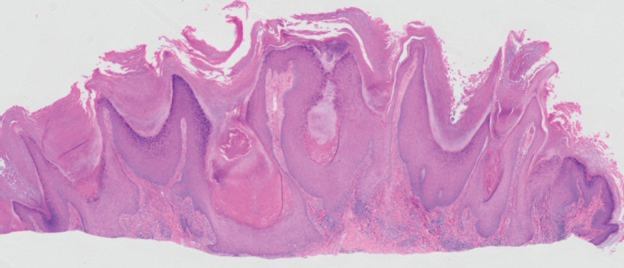

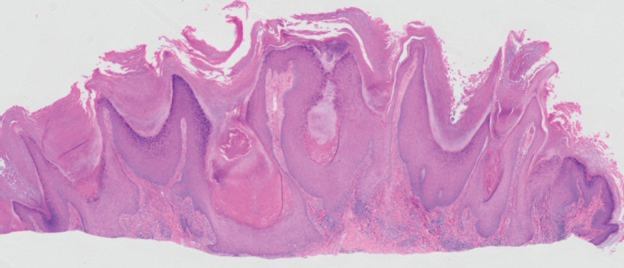

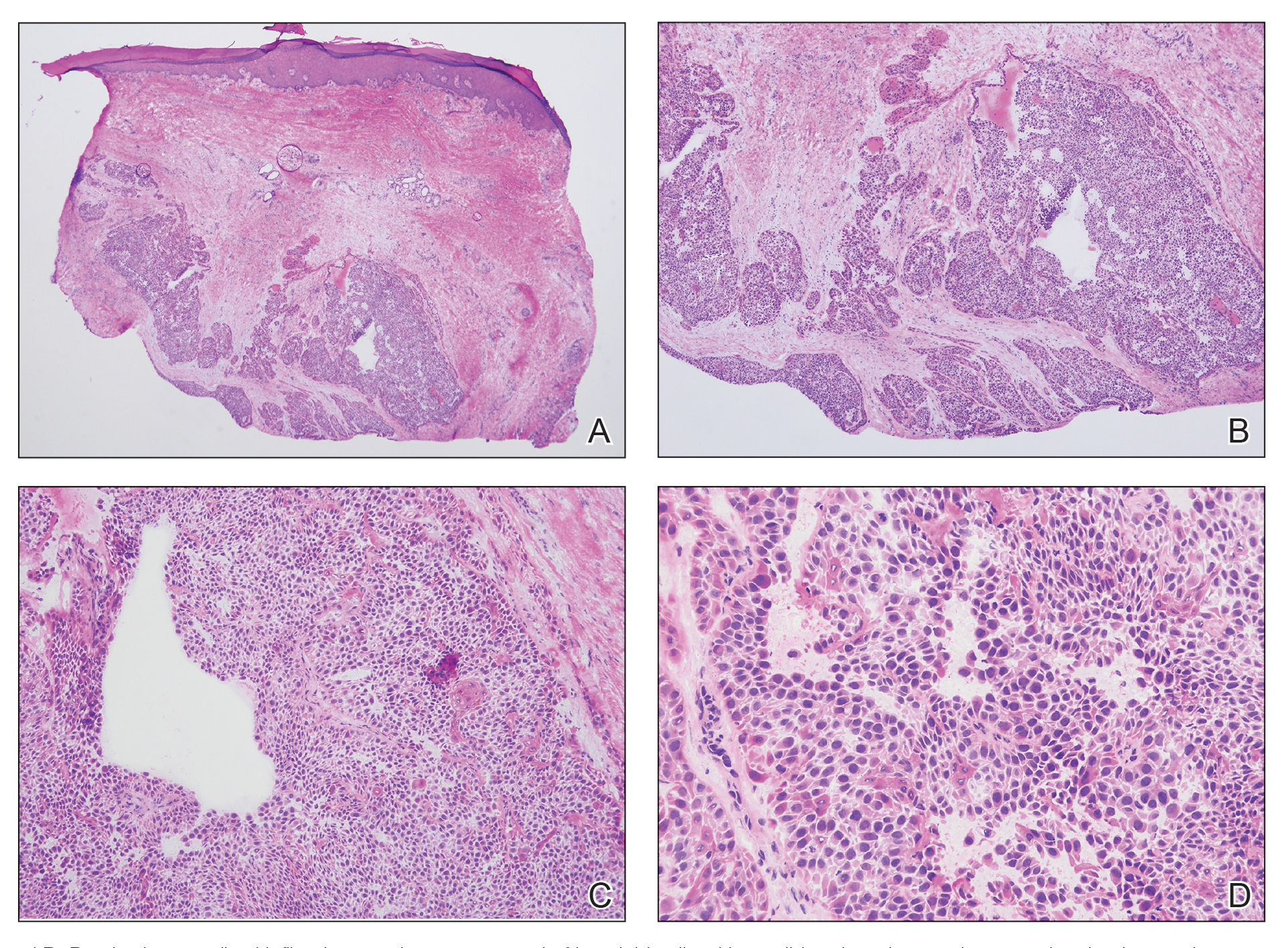

Histopathology revealed a dermal mesenchymal tumor composed of fascicles of bland spindle cells with tapered nuclei, perinuclear vacuoles, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and low cellularity (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical studies of the cells stained strongly positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin, consistent with a smooth muscle neoplasm (Figure 2). Fumarate hydratase (FH) staining revealed loss of expression in tumor cells, consistent with FH deficiency (Figure 3). A diagnosis of cutaneous leiomyoma was made, and although the clinical and histologic findings suggested hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC), genetic testing was negative for an FH gene mutation. This negative result indicated that HLRCC was unlikely despite the initial concerns based on the findings.

Leiomyomas are benign neoplasms that are challenging to diagnose based on the clinical picture alone. Leiomyomas most commonly are found in the genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems, with cutaneous manifestation being the second most common presentation.1 These benign smooth muscle tumors manifest as tender, firm, flesh-colored, pink or reddish-brown nodules that are subcategorized based on the derivation of the smooth muscle within the tumor.2 Angioleiomyomas, the most common type, arise from the tunica media of blood vessels, whereas piloleiomyomas and genital leiomyomas arise from the arrector pili musculature of the hair follicle and the smooth muscle found in the scrotum, labia, or nipple.2 Rare cases of cutaneous leiomyosarcomas and angioleiomyosarcomas have been reported in the literature.3,4 Solitary leiomyomas tend to develop on the lower extremities, whereas multiple lesions frequently manifest on the extensor surfaces of extremities and the trunk. Lesions often are painful, either spontaneously or in association with applied pressure, emotional stress, or exposure to cold temperatures.2

Although leiomyomas themselves are benign, patients with multiple cutaneous leiomyomas may have an underlying genetic mutation that increases their risk of developing HLRCC, an autosomal-dominant syndrome.5 Referral should be considered for individuals with a personal history of or a first-degree relative with cutaneous leiomyomas or renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with histology typical of hereditary leiomyomatosis and RCC, as recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors.6 In this case, the decision to refer the patient for genetic testing was based on her family history, specifically her paternal uncle having multiple similar lesions, which, while not a first-degree relative, still raised concerns about potential hereditary risks and warranted further evaluation. A germline mutation in the FH gene, which encodes an enzyme that converts fumarate to malate in the Krebs cycle and plays a role in tumor suppression, is the cause of HLRCC.2,7 When part of this genetic condition, cutaneous leiomyomas tend to occur around 25 years of age (range, 10-50 years).2 A diagnosis of HLRCC should be strongly considered if a patient displays multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with at least 1 histologically confirmed lesion or at least 2 of the following: solitary cutaneous leiomyoma with family history of HLRCC, onset of severely symptomatic uterine fibroids before age 40 years, type II papillary or collecting duct renal cell cancer before age 40 years, or a first-degree family member who meets 1 of these criteria.5,8

Diagnosis of cutaneous leiomyoma may be accomplished by microscopic examination of a tissue sample; however, further diagnostic workup is warranted due to the strong correlation with HLRCC.2 A definitive diagnosis of HLRCC is confirmed with a germline mutation in the FH gene, and genetic screening should be offered to patients before renal cancer surveillance to avoid unwarranted investigations.8 Timely clinical diagnosis enables early genetic testing and enhanced outcomes for patients with confirmed HLRCC who may need a multidisciplinary approach of dermatologists, gynecologists, and urologic oncologists.5,8

Cutaneous leiomyomas can be excised, and this typically is the gold standard of care for small and localized lesions, although the use of cryosurgery and carbon dioxide lasers has been reported as well.2,9,10 For more widespread lesions or for patients who are not appropriate candidates for surgery, pharmacologic therapies (α-blockers, calcium channel blockers, nitroglycerin), intralesional corticosteroids, and/or botulinum toxin injections can be utilized.2,11

The acronym BLEND AN EGG encompasses the clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors: blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor. Blue rubber bleb nevi are deep blue in color, and angiolipomas sit under the skin and present as subcutaneous swellings. Dermatofibromas and neurofibromas also are included in the differential.12 Dermatofibromas are firm solitary lesions that have a pathognomonic pinch sign. Neurofibromas are soft and rubbery, have a buttonhole sign, and stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 but negatively for actin and desmin.12

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Chayed Z, Kristensen LK, Ousager LB, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma: a case series and literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:34. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-01653-9

- Perkins J, Scarbrough C, Sammons D, et al. Reed syndrome: an atypical presentation of a rare disease. Dermatol Online J. 2014;21: 13030/qt5k35r5pn.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:253-260. doi:10.2147 /IJNRD.S42097

- Hampel H, Bennett RL, Buchanan A, et al. A practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genet Med. 2015;17:70-87. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.147

- Alam NA, Barclay E, Rowan AJ, et al. Clinical features of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis: an underdiagnosed tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:199-206. doi:10.1001 /archderm.141.2.199

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644. doi:10.1007/s10689-014-9735-2

- Uyar B, Acar EM, Subas¸ıog˘lu A. Treatment of three hereditary leiomyomatosis patients with cryotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13226. doi:10.1111/dth.13226

- Christenson LJ, Smith K, Arpey CJ. Treatment of multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with CO2 laser ablation. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:319-322. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99250.x

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma- related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2008.05.044

- Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Adams JL. Painful papules on the arms. Cutis. 2020;106:232-249. doi:10.12788/cutis.0109

The Diagnosis: Leiomyoma

Histopathology revealed a dermal mesenchymal tumor composed of fascicles of bland spindle cells with tapered nuclei, perinuclear vacuoles, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and low cellularity (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical studies of the cells stained strongly positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin, consistent with a smooth muscle neoplasm (Figure 2). Fumarate hydratase (FH) staining revealed loss of expression in tumor cells, consistent with FH deficiency (Figure 3). A diagnosis of cutaneous leiomyoma was made, and although the clinical and histologic findings suggested hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC), genetic testing was negative for an FH gene mutation. This negative result indicated that HLRCC was unlikely despite the initial concerns based on the findings.

Leiomyomas are benign neoplasms that are challenging to diagnose based on the clinical picture alone. Leiomyomas most commonly are found in the genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems, with cutaneous manifestation being the second most common presentation.1 These benign smooth muscle tumors manifest as tender, firm, flesh-colored, pink or reddish-brown nodules that are subcategorized based on the derivation of the smooth muscle within the tumor.2 Angioleiomyomas, the most common type, arise from the tunica media of blood vessels, whereas piloleiomyomas and genital leiomyomas arise from the arrector pili musculature of the hair follicle and the smooth muscle found in the scrotum, labia, or nipple.2 Rare cases of cutaneous leiomyosarcomas and angioleiomyosarcomas have been reported in the literature.3,4 Solitary leiomyomas tend to develop on the lower extremities, whereas multiple lesions frequently manifest on the extensor surfaces of extremities and the trunk. Lesions often are painful, either spontaneously or in association with applied pressure, emotional stress, or exposure to cold temperatures.2

Although leiomyomas themselves are benign, patients with multiple cutaneous leiomyomas may have an underlying genetic mutation that increases their risk of developing HLRCC, an autosomal-dominant syndrome.5 Referral should be considered for individuals with a personal history of or a first-degree relative with cutaneous leiomyomas or renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with histology typical of hereditary leiomyomatosis and RCC, as recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors.6 In this case, the decision to refer the patient for genetic testing was based on her family history, specifically her paternal uncle having multiple similar lesions, which, while not a first-degree relative, still raised concerns about potential hereditary risks and warranted further evaluation. A germline mutation in the FH gene, which encodes an enzyme that converts fumarate to malate in the Krebs cycle and plays a role in tumor suppression, is the cause of HLRCC.2,7 When part of this genetic condition, cutaneous leiomyomas tend to occur around 25 years of age (range, 10-50 years).2 A diagnosis of HLRCC should be strongly considered if a patient displays multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with at least 1 histologically confirmed lesion or at least 2 of the following: solitary cutaneous leiomyoma with family history of HLRCC, onset of severely symptomatic uterine fibroids before age 40 years, type II papillary or collecting duct renal cell cancer before age 40 years, or a first-degree family member who meets 1 of these criteria.5,8

Diagnosis of cutaneous leiomyoma may be accomplished by microscopic examination of a tissue sample; however, further diagnostic workup is warranted due to the strong correlation with HLRCC.2 A definitive diagnosis of HLRCC is confirmed with a germline mutation in the FH gene, and genetic screening should be offered to patients before renal cancer surveillance to avoid unwarranted investigations.8 Timely clinical diagnosis enables early genetic testing and enhanced outcomes for patients with confirmed HLRCC who may need a multidisciplinary approach of dermatologists, gynecologists, and urologic oncologists.5,8

Cutaneous leiomyomas can be excised, and this typically is the gold standard of care for small and localized lesions, although the use of cryosurgery and carbon dioxide lasers has been reported as well.2,9,10 For more widespread lesions or for patients who are not appropriate candidates for surgery, pharmacologic therapies (α-blockers, calcium channel blockers, nitroglycerin), intralesional corticosteroids, and/or botulinum toxin injections can be utilized.2,11

The acronym BLEND AN EGG encompasses the clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors: blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor. Blue rubber bleb nevi are deep blue in color, and angiolipomas sit under the skin and present as subcutaneous swellings. Dermatofibromas and neurofibromas also are included in the differential.12 Dermatofibromas are firm solitary lesions that have a pathognomonic pinch sign. Neurofibromas are soft and rubbery, have a buttonhole sign, and stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 but negatively for actin and desmin.12

The Diagnosis: Leiomyoma

Histopathology revealed a dermal mesenchymal tumor composed of fascicles of bland spindle cells with tapered nuclei, perinuclear vacuoles, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and low cellularity (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical studies of the cells stained strongly positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin, consistent with a smooth muscle neoplasm (Figure 2). Fumarate hydratase (FH) staining revealed loss of expression in tumor cells, consistent with FH deficiency (Figure 3). A diagnosis of cutaneous leiomyoma was made, and although the clinical and histologic findings suggested hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC), genetic testing was negative for an FH gene mutation. This negative result indicated that HLRCC was unlikely despite the initial concerns based on the findings.

Leiomyomas are benign neoplasms that are challenging to diagnose based on the clinical picture alone. Leiomyomas most commonly are found in the genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems, with cutaneous manifestation being the second most common presentation.1 These benign smooth muscle tumors manifest as tender, firm, flesh-colored, pink or reddish-brown nodules that are subcategorized based on the derivation of the smooth muscle within the tumor.2 Angioleiomyomas, the most common type, arise from the tunica media of blood vessels, whereas piloleiomyomas and genital leiomyomas arise from the arrector pili musculature of the hair follicle and the smooth muscle found in the scrotum, labia, or nipple.2 Rare cases of cutaneous leiomyosarcomas and angioleiomyosarcomas have been reported in the literature.3,4 Solitary leiomyomas tend to develop on the lower extremities, whereas multiple lesions frequently manifest on the extensor surfaces of extremities and the trunk. Lesions often are painful, either spontaneously or in association with applied pressure, emotional stress, or exposure to cold temperatures.2

Although leiomyomas themselves are benign, patients with multiple cutaneous leiomyomas may have an underlying genetic mutation that increases their risk of developing HLRCC, an autosomal-dominant syndrome.5 Referral should be considered for individuals with a personal history of or a first-degree relative with cutaneous leiomyomas or renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with histology typical of hereditary leiomyomatosis and RCC, as recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors.6 In this case, the decision to refer the patient for genetic testing was based on her family history, specifically her paternal uncle having multiple similar lesions, which, while not a first-degree relative, still raised concerns about potential hereditary risks and warranted further evaluation. A germline mutation in the FH gene, which encodes an enzyme that converts fumarate to malate in the Krebs cycle and plays a role in tumor suppression, is the cause of HLRCC.2,7 When part of this genetic condition, cutaneous leiomyomas tend to occur around 25 years of age (range, 10-50 years).2 A diagnosis of HLRCC should be strongly considered if a patient displays multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with at least 1 histologically confirmed lesion or at least 2 of the following: solitary cutaneous leiomyoma with family history of HLRCC, onset of severely symptomatic uterine fibroids before age 40 years, type II papillary or collecting duct renal cell cancer before age 40 years, or a first-degree family member who meets 1 of these criteria.5,8

Diagnosis of cutaneous leiomyoma may be accomplished by microscopic examination of a tissue sample; however, further diagnostic workup is warranted due to the strong correlation with HLRCC.2 A definitive diagnosis of HLRCC is confirmed with a germline mutation in the FH gene, and genetic screening should be offered to patients before renal cancer surveillance to avoid unwarranted investigations.8 Timely clinical diagnosis enables early genetic testing and enhanced outcomes for patients with confirmed HLRCC who may need a multidisciplinary approach of dermatologists, gynecologists, and urologic oncologists.5,8

Cutaneous leiomyomas can be excised, and this typically is the gold standard of care for small and localized lesions, although the use of cryosurgery and carbon dioxide lasers has been reported as well.2,9,10 For more widespread lesions or for patients who are not appropriate candidates for surgery, pharmacologic therapies (α-blockers, calcium channel blockers, nitroglycerin), intralesional corticosteroids, and/or botulinum toxin injections can be utilized.2,11

The acronym BLEND AN EGG encompasses the clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors: blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor. Blue rubber bleb nevi are deep blue in color, and angiolipomas sit under the skin and present as subcutaneous swellings. Dermatofibromas and neurofibromas also are included in the differential.12 Dermatofibromas are firm solitary lesions that have a pathognomonic pinch sign. Neurofibromas are soft and rubbery, have a buttonhole sign, and stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 but negatively for actin and desmin.12

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Chayed Z, Kristensen LK, Ousager LB, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma: a case series and literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:34. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-01653-9

- Perkins J, Scarbrough C, Sammons D, et al. Reed syndrome: an atypical presentation of a rare disease. Dermatol Online J. 2014;21: 13030/qt5k35r5pn.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:253-260. doi:10.2147 /IJNRD.S42097

- Hampel H, Bennett RL, Buchanan A, et al. A practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genet Med. 2015;17:70-87. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.147

- Alam NA, Barclay E, Rowan AJ, et al. Clinical features of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis: an underdiagnosed tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:199-206. doi:10.1001 /archderm.141.2.199

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644. doi:10.1007/s10689-014-9735-2

- Uyar B, Acar EM, Subas¸ıog˘lu A. Treatment of three hereditary leiomyomatosis patients with cryotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13226. doi:10.1111/dth.13226

- Christenson LJ, Smith K, Arpey CJ. Treatment of multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with CO2 laser ablation. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:319-322. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99250.x

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma- related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2008.05.044

- Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Adams JL. Painful papules on the arms. Cutis. 2020;106:232-249. doi:10.12788/cutis.0109

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Chayed Z, Kristensen LK, Ousager LB, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma: a case series and literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:34. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-01653-9

- Perkins J, Scarbrough C, Sammons D, et al. Reed syndrome: an atypical presentation of a rare disease. Dermatol Online J. 2014;21: 13030/qt5k35r5pn.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:253-260. doi:10.2147 /IJNRD.S42097

- Hampel H, Bennett RL, Buchanan A, et al. A practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genet Med. 2015;17:70-87. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.147

- Alam NA, Barclay E, Rowan AJ, et al. Clinical features of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis: an underdiagnosed tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:199-206. doi:10.1001 /archderm.141.2.199

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644. doi:10.1007/s10689-014-9735-2

- Uyar B, Acar EM, Subas¸ıog˘lu A. Treatment of three hereditary leiomyomatosis patients with cryotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13226. doi:10.1111/dth.13226

- Christenson LJ, Smith K, Arpey CJ. Treatment of multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with CO2 laser ablation. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:319-322. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99250.x

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma- related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2008.05.044

- Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Adams JL. Painful papules on the arms. Cutis. 2020;106:232-249. doi:10.12788/cutis.0109

A Painful Flesh-Colored Papule on the Shoulder

A Painful Flesh-Colored Papule on the Shoulder

A 65-year-old woman with a history of metabolic syndrome presented to the family medicine clinic for evaluation of a papule on the right shoulder that had started small and increased in size over the past 3 years. Physical examination revealed a 1.0×0.8×0.1-cm, smooth, flesh-colored to light brown papule on the right shoulder that was notably tender to palpation. The patient reported that her paternal uncle had multiple skin lesions of similar morphology dispersed on the bilateral upper extremities. A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Erythematous Annular Scaly Plaques on the Upper Chest

Erythematous Annular Scaly Plaques on the Upper Chest

THE DIAGNOSIS: Tinea Corporis

Due to the scaly and acute nature of the rash, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed, and hyphal elements were floridly present. After further questioning, the patient reported finding a stray kitten a few weeks before the onset of the eruption and shared a picture of it lying on her chest in the area corresponding with the main distribution of the rash (Figure). Based on the patient’s personal history and the positive KOH preparation, a diagnosis of tinea corporis was made. She was immediately started on fluconazole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks and naftifine gel 1%, which she used for 6 to 8 weeks with complete resolution of the eruption.

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection that typically affects exposed areas of the skin such as the chest, arms, and legs. Spread via human-to-human contact, Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause worldwide. The second most common is Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which is spread through animal-to-human contact.1,2

Symptoms of tinea corporis usually appear 1 to 3 weeks after exposure and manifest as itchy scaly papules that spread outward, forming annular, circinate, and petaloid erythematous plaques with central clearing. The condition most commonly is diagnosed through the examination of scale from the affected area using a KOH preparation, which will reveal hyphae when positive.2-4 Cultures are the gold standard for identifying dermatophyte species,5 but results can take several weeks. Biopsy also can confirm the diagnosis by showing the presence of hyphae in the stratum corneum, which can be highlighted using periodic acid–Schiff or silver stains.3

Topical antifungals are the first-line treatment for cutaneous dermatophyte infections.3-5 The most effective topical therapies are allylamines and azoles, which work by inhibiting the growth of the fungus. Allylamines are more effective than azoles due to their fungicidal properties and ability to penetrate the skin more effectively.6,7 Topical medications should be applied at least 2 cm beyond the infected area for 2 to 4 weeks or until the infection has cleared.3 Systemic antifungals may be necessary in more complicated cases.

It is important to consider a broad differential and take into consideration the distribution of the plaques, the patient’s history, and other clinical features when differentiating tinea corporis from other conditions. Erythema annulare centrifugum more often presents as nonpruritic annular plaques with a trailing scale instead of a leading scale seen in tinea corporis. Biopsy exhibits a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate in superficial vessels, resembling a coat sleeve.3,8 Pemphigus foliaceous can manifest with painful crusted scaly plaques and vesicles in a seborrheic distribution. Biopsy reveals subcorneal acantholytic vesicles and can be confirmed on direct immunofluorescence.3,8 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus presents with annular plaques that often are symmetric and most prominent in sun-exposed areas, sparing the face.3,9,10 It can be associated with other autoimmune conditions as well as medications such as thiazides, terbinafine, and calcium channel blockers. Additionally, 76% to 90% of patients are Ro/SSA antibody positive.3 Biopsy often demonstrates follicular plugging, perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates, and mucin.3,10 Lastly, pityriasis rosea typically begins with a herald patch, followed by a widespread rash that often appears in a Christmas tree distribution.3

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51 (suppl 4):2-15. doi: 10.1111 /j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x

- Yee G, Al Aboud AM. Tinea corporis. 2022 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Diseases resulting from fungal and yeast. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of The Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2016: 289-290.

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6 . doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD009992. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD009992.pub2

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Burgdorf W. Erythema annulare centrifugum and other figurate erythemas. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2008: 366-368.

- Modi GM, Maender JL, Coleman N, et al. Tinea corporis masquerading as subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:8.

- Stavropoulos PG, Goules AV, Avgerinou G, et al. Pathogenesis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1281.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Tinea Corporis

Due to the scaly and acute nature of the rash, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed, and hyphal elements were floridly present. After further questioning, the patient reported finding a stray kitten a few weeks before the onset of the eruption and shared a picture of it lying on her chest in the area corresponding with the main distribution of the rash (Figure). Based on the patient’s personal history and the positive KOH preparation, a diagnosis of tinea corporis was made. She was immediately started on fluconazole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks and naftifine gel 1%, which she used for 6 to 8 weeks with complete resolution of the eruption.

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection that typically affects exposed areas of the skin such as the chest, arms, and legs. Spread via human-to-human contact, Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause worldwide. The second most common is Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which is spread through animal-to-human contact.1,2

Symptoms of tinea corporis usually appear 1 to 3 weeks after exposure and manifest as itchy scaly papules that spread outward, forming annular, circinate, and petaloid erythematous plaques with central clearing. The condition most commonly is diagnosed through the examination of scale from the affected area using a KOH preparation, which will reveal hyphae when positive.2-4 Cultures are the gold standard for identifying dermatophyte species,5 but results can take several weeks. Biopsy also can confirm the diagnosis by showing the presence of hyphae in the stratum corneum, which can be highlighted using periodic acid–Schiff or silver stains.3

Topical antifungals are the first-line treatment for cutaneous dermatophyte infections.3-5 The most effective topical therapies are allylamines and azoles, which work by inhibiting the growth of the fungus. Allylamines are more effective than azoles due to their fungicidal properties and ability to penetrate the skin more effectively.6,7 Topical medications should be applied at least 2 cm beyond the infected area for 2 to 4 weeks or until the infection has cleared.3 Systemic antifungals may be necessary in more complicated cases.

It is important to consider a broad differential and take into consideration the distribution of the plaques, the patient’s history, and other clinical features when differentiating tinea corporis from other conditions. Erythema annulare centrifugum more often presents as nonpruritic annular plaques with a trailing scale instead of a leading scale seen in tinea corporis. Biopsy exhibits a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate in superficial vessels, resembling a coat sleeve.3,8 Pemphigus foliaceous can manifest with painful crusted scaly plaques and vesicles in a seborrheic distribution. Biopsy reveals subcorneal acantholytic vesicles and can be confirmed on direct immunofluorescence.3,8 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus presents with annular plaques that often are symmetric and most prominent in sun-exposed areas, sparing the face.3,9,10 It can be associated with other autoimmune conditions as well as medications such as thiazides, terbinafine, and calcium channel blockers. Additionally, 76% to 90% of patients are Ro/SSA antibody positive.3 Biopsy often demonstrates follicular plugging, perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates, and mucin.3,10 Lastly, pityriasis rosea typically begins with a herald patch, followed by a widespread rash that often appears in a Christmas tree distribution.3

THE DIAGNOSIS: Tinea Corporis

Due to the scaly and acute nature of the rash, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed, and hyphal elements were floridly present. After further questioning, the patient reported finding a stray kitten a few weeks before the onset of the eruption and shared a picture of it lying on her chest in the area corresponding with the main distribution of the rash (Figure). Based on the patient’s personal history and the positive KOH preparation, a diagnosis of tinea corporis was made. She was immediately started on fluconazole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks and naftifine gel 1%, which she used for 6 to 8 weeks with complete resolution of the eruption.

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection that typically affects exposed areas of the skin such as the chest, arms, and legs. Spread via human-to-human contact, Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause worldwide. The second most common is Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which is spread through animal-to-human contact.1,2

Symptoms of tinea corporis usually appear 1 to 3 weeks after exposure and manifest as itchy scaly papules that spread outward, forming annular, circinate, and petaloid erythematous plaques with central clearing. The condition most commonly is diagnosed through the examination of scale from the affected area using a KOH preparation, which will reveal hyphae when positive.2-4 Cultures are the gold standard for identifying dermatophyte species,5 but results can take several weeks. Biopsy also can confirm the diagnosis by showing the presence of hyphae in the stratum corneum, which can be highlighted using periodic acid–Schiff or silver stains.3

Topical antifungals are the first-line treatment for cutaneous dermatophyte infections.3-5 The most effective topical therapies are allylamines and azoles, which work by inhibiting the growth of the fungus. Allylamines are more effective than azoles due to their fungicidal properties and ability to penetrate the skin more effectively.6,7 Topical medications should be applied at least 2 cm beyond the infected area for 2 to 4 weeks or until the infection has cleared.3 Systemic antifungals may be necessary in more complicated cases.

It is important to consider a broad differential and take into consideration the distribution of the plaques, the patient’s history, and other clinical features when differentiating tinea corporis from other conditions. Erythema annulare centrifugum more often presents as nonpruritic annular plaques with a trailing scale instead of a leading scale seen in tinea corporis. Biopsy exhibits a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate in superficial vessels, resembling a coat sleeve.3,8 Pemphigus foliaceous can manifest with painful crusted scaly plaques and vesicles in a seborrheic distribution. Biopsy reveals subcorneal acantholytic vesicles and can be confirmed on direct immunofluorescence.3,8 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus presents with annular plaques that often are symmetric and most prominent in sun-exposed areas, sparing the face.3,9,10 It can be associated with other autoimmune conditions as well as medications such as thiazides, terbinafine, and calcium channel blockers. Additionally, 76% to 90% of patients are Ro/SSA antibody positive.3 Biopsy often demonstrates follicular plugging, perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates, and mucin.3,10 Lastly, pityriasis rosea typically begins with a herald patch, followed by a widespread rash that often appears in a Christmas tree distribution.3

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51 (suppl 4):2-15. doi: 10.1111 /j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x

- Yee G, Al Aboud AM. Tinea corporis. 2022 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Diseases resulting from fungal and yeast. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of The Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2016: 289-290.

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6 . doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD009992. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD009992.pub2

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Burgdorf W. Erythema annulare centrifugum and other figurate erythemas. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2008: 366-368.

- Modi GM, Maender JL, Coleman N, et al. Tinea corporis masquerading as subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:8.

- Stavropoulos PG, Goules AV, Avgerinou G, et al. Pathogenesis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1281.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51 (suppl 4):2-15. doi: 10.1111 /j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x

- Yee G, Al Aboud AM. Tinea corporis. 2022 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Diseases resulting from fungal and yeast. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of The Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2016: 289-290.

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6 . doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD009992. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD009992.pub2

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Burgdorf W. Erythema annulare centrifugum and other figurate erythemas. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2008: 366-368.

- Modi GM, Maender JL, Coleman N, et al. Tinea corporis masquerading as subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:8.

- Stavropoulos PG, Goules AV, Avgerinou G, et al. Pathogenesis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1281.

Erythematous Annular Scaly Plaques on the Upper Chest

Erythematous Annular Scaly Plaques on the Upper Chest

A 60-year-old woman with a history of keratinocyte carcinomas, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and anxiety presented to the dermatology department with a widespread rash of more than 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had tried 1 to 2 days of self-treatment with triamcinolone cream that she had previously been prescribed for an unknown dermatitis and zinc oxide cream, which caused considerable inflammation of the rash and prompted her to discontinue use. She could not recall any recent use of new personal care products or medications or eating any new foods. She also denied any recent yard work, known arthropod bites, illnesses, prolonged sun exposure, or constitutional symptoms. Her medications included metformin, hydrochlorothiazide, losartan, and sertraline. She also reported taking daily supplements of vitamins D, K, and C as well as acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. Physical examination revealed several 2- to 4-cm, erythematous, annular, circinate, petaloid plaques with scale mostly on photodistributed areas of the central anterior chest, neck, lower cheeks, and chin as well as a few scattered lesions with similar morphology on the arms, lower abdomen, left buttock, and back.

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

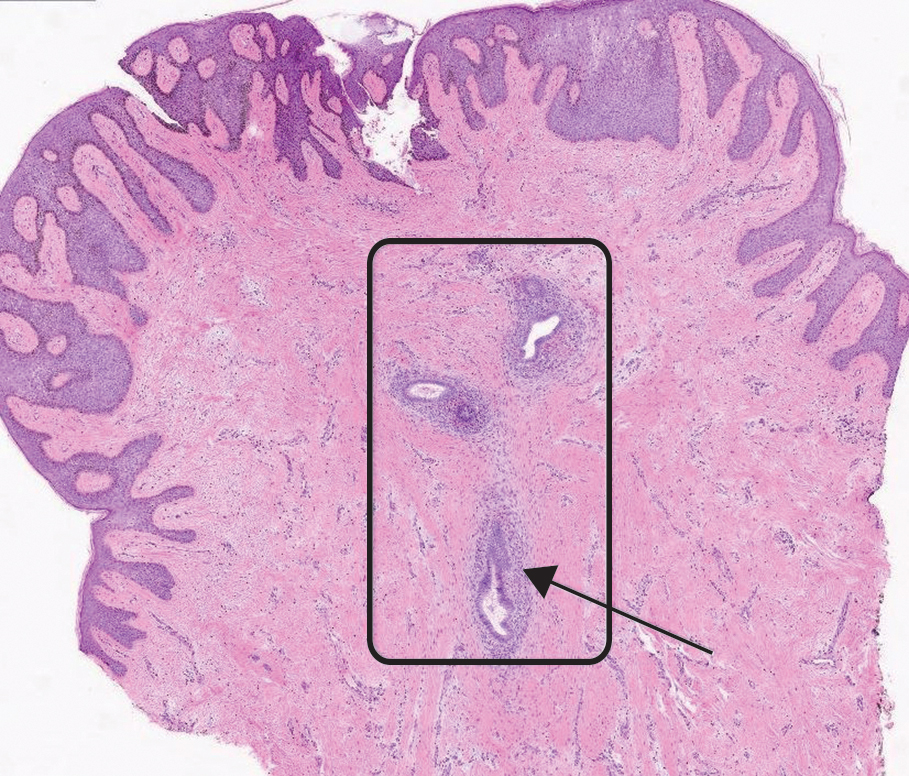

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

A 38-year-old nulligravid female with menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea presented with cyclical umbilical bleeding of 1 year’s duration. Shortly before the onset of symptoms, the patient had discontinued oral contraceptive therapy with the intent to become pregnant. She had an uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy 10 years prior, but her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. At the current presentation, physical examination revealed multilobular brown papules with serosanguineous crusting in the umbilicus.

Bilateral Brownish-Red Indurated Facial Plaques in an Adult Man

Bilateral Brownish-Red Indurated Facial Plaques in an Adult Man

THE DIAGNOSIS: Granuloma Faciale

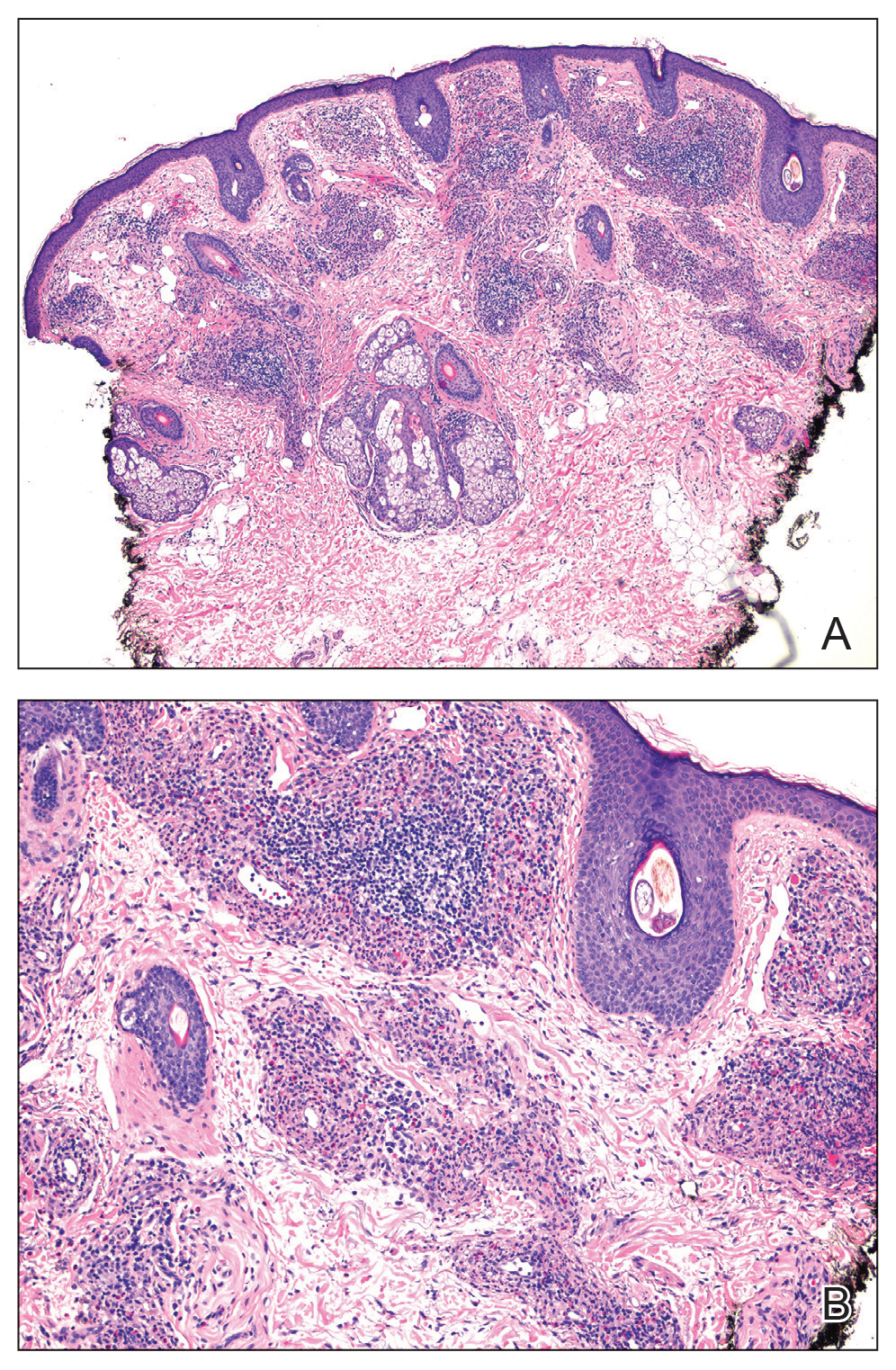

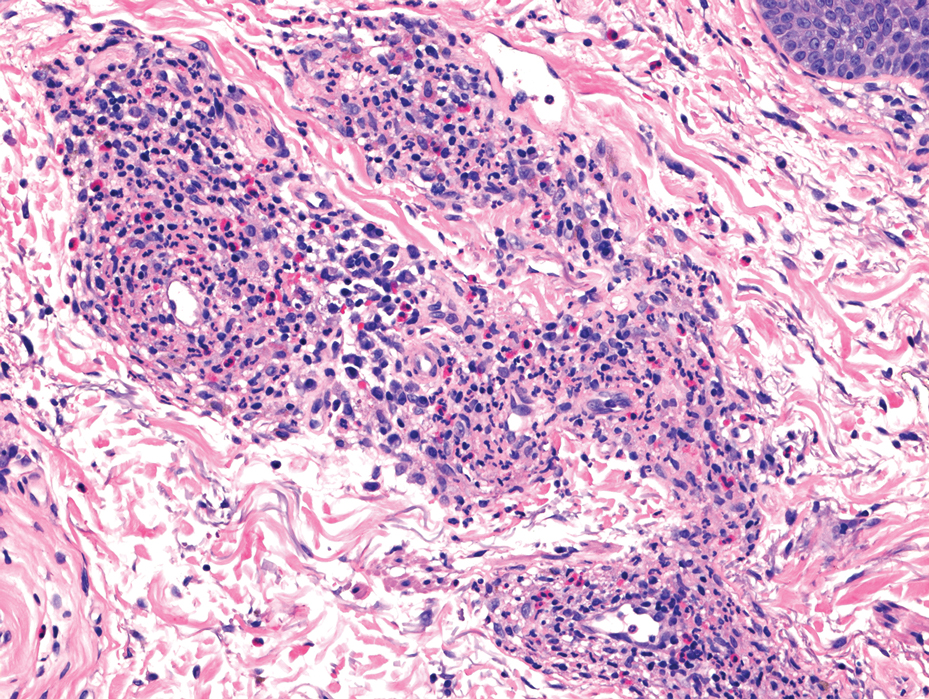

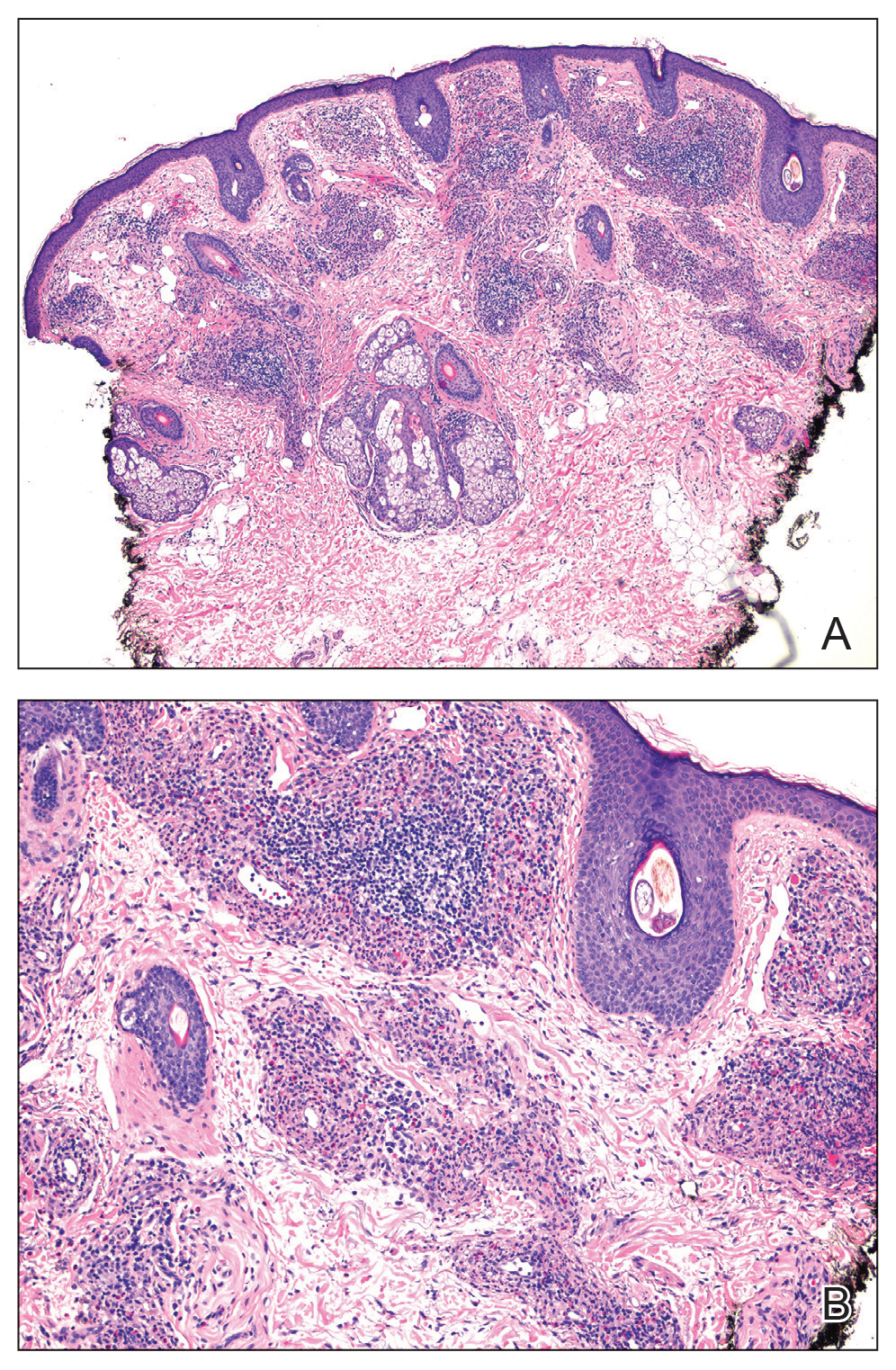

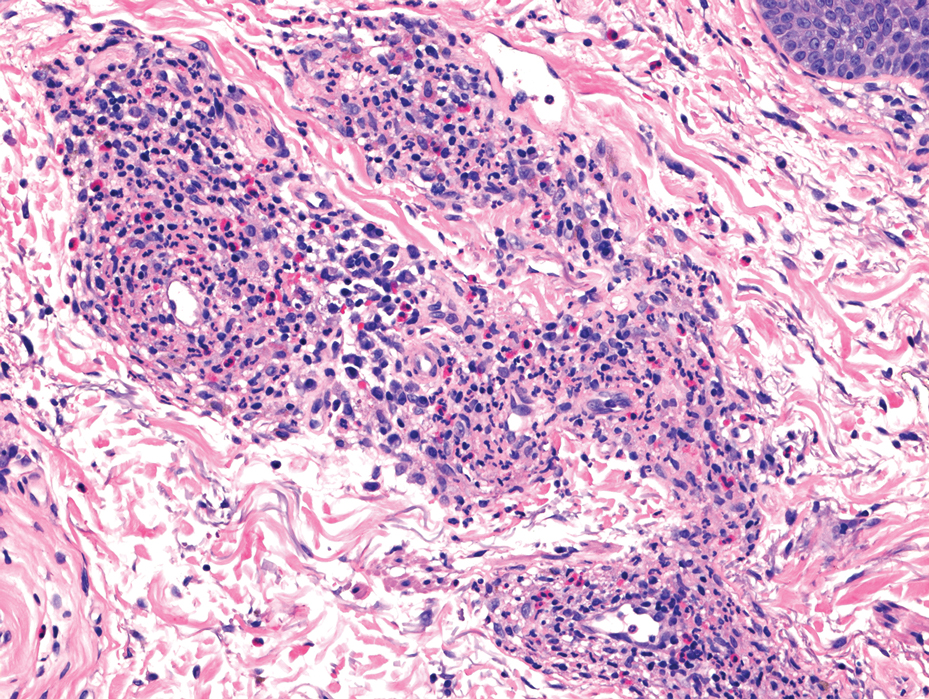

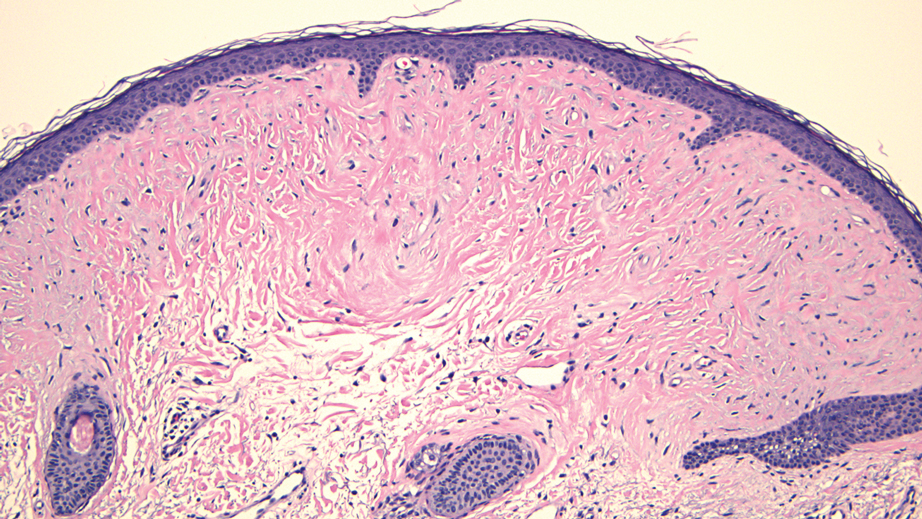

Histology revealed a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with conspicuous neutrophils and eosinophils in the upper to mid dermis with a narrow uninvolved grenz zone beneath the epidermis (Figures 1 and 2). These findings along with the clinical presentation (Figure 3) were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma faciale (GF). Most often seen in middle-aged White men, GF is an uncommon localized inflammatory skin condition that often manifests as a single, well-defined, red-to-brown papule, nodule, or plaque on the face or other sun-exposed areas of the skin. Since numerous other skin diseases manifest similarly to GF, biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis.1 Histopathology of GF classically shows a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a narrow band of uninvolved dermis separating it from the epidermis (grenz zone). Dilated follicular plugs and vascular changes frequently are appreciated. Despite its name, GF does not include granulomas and is thought to be similar to leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1 Reports of GF in the literature have shown immunohistochemical staining with the presence of CD4+ lymphocytes that secrete IL-5, a chemotactic agent responsible for attracting eosinophils that contributes to the eosinophilic infiltrate on histology.2

Topical corticosteroids and topical tacrolimus are the first-line treatments for GF. Intralesional corticosteroids also are a treatment option and can be used in combination with cryotherapy.1,3 Additionally, both topical and oral dapsone have been shown to be effective for GF.1 Oral dapsone is given at a dose of 50 mg to 150 mg once daily.1 Clofazimine, typically used as an antileprosy treatment, also has been efficacious in treating GF. Clofazimine has anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects on lymphocytes that may attenuate the inflammation underlying GF. It is prescribed at a dose of 300 mg once daily for 3 to 5 months.1

The differential diagnosis for GF is broad and includes tumid lupus erythematosus, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate (JLI), cutaneous sarcoidosis, and mycosis fungoides. Tumid lupus erythematosus is a subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that rarely is associated with systemic lupus manifestations. Tumid lupus erythematosus manifests as annular, indurated, erythematous plaques, whereas JLI manifests with erythematous papular to nodular lesions without scale on the upper back or face.4 Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate and tumid lupus erythematosus are histopathologically identical, with abundant dermal mucin deposition and a superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate. It is debatable whether JLI is a separate entity or a variant of tumid lupus erythematosus. Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that manifests with a myriad of clinical features. The skin is the second most commonly involved organ.5 The most common morphology is numerous small, firm, nonscaly papules, typically on the face. Histology in cutaneous sarcoidosis will show lymphocyte-poor, noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas with positive reticulin staining, which were not seen in our patient.6 Lastly, mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It can manifest as patches, plaques, or tumors. The plaque stage may mimic GF as lesions are infiltrative, annular, and raised, with well-defined margins. Histopathology will show intraepidermal lymphocytes out of proportion with spongiosis.7

- Al Dhafiri M, Kaliyadan F. Granuloma faciale. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 4, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539832/

- Chen A, Harview CL, Rand SE, et al. Refractory granuloma faciale successfully treated with adjunct topical JAK inhibitor. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;33:91-94. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.01.016

- Dowlati B, Firooz A, Dowlati Y. Granuloma faciale: successful treatment of nine cases with a combination of cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroid injection. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:548-551. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00161.x

- Koritala T, Grubbs H, Crane J. Tumid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 28, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482515/

- Caplan A, Rosenbach M, Imadojemu S. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:689-699. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1713130

- Singh P, Jain E, Dhingra H, et al. Clinico-pathological spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: an experience from a government institute in North India. Med Pharm Rep. 2020;93:241-245. doi:10.15386 /mpr-1384

- Vaidya T, Badri T. Mycosis fungoides. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519572/

THE DIAGNOSIS: Granuloma Faciale

Histology revealed a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with conspicuous neutrophils and eosinophils in the upper to mid dermis with a narrow uninvolved grenz zone beneath the epidermis (Figures 1 and 2). These findings along with the clinical presentation (Figure 3) were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma faciale (GF). Most often seen in middle-aged White men, GF is an uncommon localized inflammatory skin condition that often manifests as a single, well-defined, red-to-brown papule, nodule, or plaque on the face or other sun-exposed areas of the skin. Since numerous other skin diseases manifest similarly to GF, biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis.1 Histopathology of GF classically shows a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a narrow band of uninvolved dermis separating it from the epidermis (grenz zone). Dilated follicular plugs and vascular changes frequently are appreciated. Despite its name, GF does not include granulomas and is thought to be similar to leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1 Reports of GF in the literature have shown immunohistochemical staining with the presence of CD4+ lymphocytes that secrete IL-5, a chemotactic agent responsible for attracting eosinophils that contributes to the eosinophilic infiltrate on histology.2

Topical corticosteroids and topical tacrolimus are the first-line treatments for GF. Intralesional corticosteroids also are a treatment option and can be used in combination with cryotherapy.1,3 Additionally, both topical and oral dapsone have been shown to be effective for GF.1 Oral dapsone is given at a dose of 50 mg to 150 mg once daily.1 Clofazimine, typically used as an antileprosy treatment, also has been efficacious in treating GF. Clofazimine has anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects on lymphocytes that may attenuate the inflammation underlying GF. It is prescribed at a dose of 300 mg once daily for 3 to 5 months.1

The differential diagnosis for GF is broad and includes tumid lupus erythematosus, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate (JLI), cutaneous sarcoidosis, and mycosis fungoides. Tumid lupus erythematosus is a subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that rarely is associated with systemic lupus manifestations. Tumid lupus erythematosus manifests as annular, indurated, erythematous plaques, whereas JLI manifests with erythematous papular to nodular lesions without scale on the upper back or face.4 Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate and tumid lupus erythematosus are histopathologically identical, with abundant dermal mucin deposition and a superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate. It is debatable whether JLI is a separate entity or a variant of tumid lupus erythematosus. Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that manifests with a myriad of clinical features. The skin is the second most commonly involved organ.5 The most common morphology is numerous small, firm, nonscaly papules, typically on the face. Histology in cutaneous sarcoidosis will show lymphocyte-poor, noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas with positive reticulin staining, which were not seen in our patient.6 Lastly, mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It can manifest as patches, plaques, or tumors. The plaque stage may mimic GF as lesions are infiltrative, annular, and raised, with well-defined margins. Histopathology will show intraepidermal lymphocytes out of proportion with spongiosis.7

THE DIAGNOSIS: Granuloma Faciale

Histology revealed a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with conspicuous neutrophils and eosinophils in the upper to mid dermis with a narrow uninvolved grenz zone beneath the epidermis (Figures 1 and 2). These findings along with the clinical presentation (Figure 3) were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma faciale (GF). Most often seen in middle-aged White men, GF is an uncommon localized inflammatory skin condition that often manifests as a single, well-defined, red-to-brown papule, nodule, or plaque on the face or other sun-exposed areas of the skin. Since numerous other skin diseases manifest similarly to GF, biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis.1 Histopathology of GF classically shows a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a narrow band of uninvolved dermis separating it from the epidermis (grenz zone). Dilated follicular plugs and vascular changes frequently are appreciated. Despite its name, GF does not include granulomas and is thought to be similar to leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1 Reports of GF in the literature have shown immunohistochemical staining with the presence of CD4+ lymphocytes that secrete IL-5, a chemotactic agent responsible for attracting eosinophils that contributes to the eosinophilic infiltrate on histology.2

Topical corticosteroids and topical tacrolimus are the first-line treatments for GF. Intralesional corticosteroids also are a treatment option and can be used in combination with cryotherapy.1,3 Additionally, both topical and oral dapsone have been shown to be effective for GF.1 Oral dapsone is given at a dose of 50 mg to 150 mg once daily.1 Clofazimine, typically used as an antileprosy treatment, also has been efficacious in treating GF. Clofazimine has anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects on lymphocytes that may attenuate the inflammation underlying GF. It is prescribed at a dose of 300 mg once daily for 3 to 5 months.1

The differential diagnosis for GF is broad and includes tumid lupus erythematosus, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate (JLI), cutaneous sarcoidosis, and mycosis fungoides. Tumid lupus erythematosus is a subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that rarely is associated with systemic lupus manifestations. Tumid lupus erythematosus manifests as annular, indurated, erythematous plaques, whereas JLI manifests with erythematous papular to nodular lesions without scale on the upper back or face.4 Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate and tumid lupus erythematosus are histopathologically identical, with abundant dermal mucin deposition and a superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate. It is debatable whether JLI is a separate entity or a variant of tumid lupus erythematosus. Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that manifests with a myriad of clinical features. The skin is the second most commonly involved organ.5 The most common morphology is numerous small, firm, nonscaly papules, typically on the face. Histology in cutaneous sarcoidosis will show lymphocyte-poor, noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas with positive reticulin staining, which were not seen in our patient.6 Lastly, mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It can manifest as patches, plaques, or tumors. The plaque stage may mimic GF as lesions are infiltrative, annular, and raised, with well-defined margins. Histopathology will show intraepidermal lymphocytes out of proportion with spongiosis.7

- Al Dhafiri M, Kaliyadan F. Granuloma faciale. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 4, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539832/

- Chen A, Harview CL, Rand SE, et al. Refractory granuloma faciale successfully treated with adjunct topical JAK inhibitor. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;33:91-94. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.01.016

- Dowlati B, Firooz A, Dowlati Y. Granuloma faciale: successful treatment of nine cases with a combination of cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroid injection. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:548-551. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00161.x

- Koritala T, Grubbs H, Crane J. Tumid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 28, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482515/

- Caplan A, Rosenbach M, Imadojemu S. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:689-699. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1713130

- Singh P, Jain E, Dhingra H, et al. Clinico-pathological spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: an experience from a government institute in North India. Med Pharm Rep. 2020;93:241-245. doi:10.15386 /mpr-1384

- Vaidya T, Badri T. Mycosis fungoides. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519572/

- Al Dhafiri M, Kaliyadan F. Granuloma faciale. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 4, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539832/

- Chen A, Harview CL, Rand SE, et al. Refractory granuloma faciale successfully treated with adjunct topical JAK inhibitor. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;33:91-94. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.01.016

- Dowlati B, Firooz A, Dowlati Y. Granuloma faciale: successful treatment of nine cases with a combination of cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroid injection. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:548-551. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00161.x

- Koritala T, Grubbs H, Crane J. Tumid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 28, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482515/

- Caplan A, Rosenbach M, Imadojemu S. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:689-699. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1713130

- Singh P, Jain E, Dhingra H, et al. Clinico-pathological spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: an experience from a government institute in North India. Med Pharm Rep. 2020;93:241-245. doi:10.15386 /mpr-1384

- Vaidya T, Badri T. Mycosis fungoides. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519572/

Bilateral Brownish-Red Indurated Facial Plaques in an Adult Man

Bilateral Brownish-Red Indurated Facial Plaques in an Adult Man

A 44-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a facial rash of 2 years’ duration. The patient reported associated pruritus but no systemic symptoms. His medical history was relevant for childhood eczema. He had tried various over-the-counter treatments for the facial rash, including topical hydrocortisone, neomycin/bacitracin/polymyxin antibiotic ointment, moisturizers, and antihistamines, with no success. Physical examination demonstrated symmetric, well-circumscribed, circinate, brownish-red, indurated plaques without scaling on the cheeks. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from a plaque on the left cheek.

Fingernail Abnormalities in an Adolescent With a History of Toe Walking

Fingernail Abnormalities in an Adolescent With a History of Toe Walking

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail-Patella Syndrome

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is an autosomaldominant disorder that is present in approximately 1 in 50,000 live births worldwide.1,2 It manifests with a spectrum of clinical findings affecting the nails, skeletal system, kidneys, and eyes.3 Most cases of NPS are caused by loss-of-function mutations in LMX1B,1 a gene encoding the LIM homeobox transcription factor.4 The LMX1B gene plays a critical role in the dorsoventral patterning of developing limbs.5 Mutations of this gene impair the development and function of podocytes and glomerular filtration slits6 and have been found to affect the development of the dopaminergic and mesencephalic serotoninergic neurons.2 Approximately 5% of patients with NPS have an unexplained genetic cause, suggesting an alternate mechanism for disease.1 Loss-of-function mutations also were observed in the Wnt inhibitory factor 1 gene (WIF1) in a family with an NPS-like presentation and could represent a novel cause of the condition.1 Regardless, NPS may be diagnosed clinically based on characteristic medical history, imaging, and physical examination findings.

Nail changes are the most consistent feature of NPS. The nails may be absent, hypoplastic, dystrophic, ridged (horizontally or vertically), or pitted or may demonstrate characteristic triangular lacunae. Nail findings often are congenital, bilateral, and symmetrical. The first digits typically are most severely affected, with progressive improvement appreciated toward the fifth fingers, as seen in our patient. The nail changes can be subtle, sometimes manifesting only as a single triangular lacuna on both thumbnails. Toenail involvement is less common and, when present, tends to be even more discreet. In contrast to the fingernails, the fifth toenails are most commonly affected.7

There are many skeletal manifestations of NPS. Patellae may be absent, hypoplastic, or irregularly shaped on physical examination or imaging, and changes may involve one or both knees. The Figure shows plain radiographs of the knees with bilateral patellar subluxation. Elbow dysplasia or radial head subluxation may result in physical limitations in extension, pronation, or supination of the joint.7 In approximately 70% of patients seen with the disorder, imaging may reveal symmetric posterior and lateral bony projections from the iliac crests, known as iliac horns; when present, these are considered pathognomonic.8

Open-angle glaucoma is the most common ocular finding in NPS. Other less commonly associated eye abnormalities include hyperpigmentation of the pupillary margin (Lester iris).6 Renal involvement occurs in 30% to 50% of patients with NPS and is the main predictor of mortality, with percentages as high as 5% to 14%.7 Defects occur in the glomerular basement membrane and manifest clinically with hematuria and/or proteinuria. The course of proteinuria is unpredictable. Some cases remit spontaneously, while others remain asymptomatic, progress to nephrotic syndrome, or, although rare, advance to renal failure.7,9

Bowel symptoms, neurologic problems, vasomotor concerns, thin dental enamel, attention-deficit disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and major depressive disorder all have been reported in association with NPS.2,7

Nail psoriasis typically exhibits nail pitting and onycholysis. Other manifestations include subungual hyperkeratosis, oil drop discoloration, and splinter hemorrhages. Topical and intralesional treatments are used to manage symptoms of the disease, as it can become debilitating if left untreated, unlike the nail disease seen in NPS.10 Onychomycosis can have a similar manifestation to psoriasis with sublingual hyperkeratosis of the nail, but it usually is caused by dermatophytes or yeasts such as Candida albicans. Onycholysis and thickening of the subungual region also can be seen. Diagnosis relies on direct microscopy and fungal culture, and a thorough patient history will help distinguish fungal vs nonfungal etiology. New-generation antifungals are used to eradicate the infection.11 Leukonychia manifests with white-appearing nails due to nail-plate or nail-bed abnormalities. Leukonychia can have multisystem involvement, but nails demonstrate a white discoloration rather than the other abnormalities discussed here.12 Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is a rare hereditary congenital disease that affects ectodermal structures and manifests with a triad of symptoms: hypotrichosis, hypohidrosis, and hypodontia. The condition often manifests in childhood with characteristic features such as light-pigmented sparse and fine hair. Physical growth as well as psychomotor development are within normal limits. Neither bone nor renal involvement is typical for hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.13

Our case highlights the typical manifestation of NPS with multisystem involvement, demonstrating the complexity of the disease. For cases in which a clinical diagnosis of NPS is uncertain, gene-targeted or comprehensive genomic testing is recommended, as well as genetic counseling. Given the broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, it is imperative that patients undergo screening for musculoskeletal, renal, and ophthalmologic involvement. Treatment is targeted at symptom management and prevention of long-term complications, reliant on clinical presentation, and specific to each patient.

- Jones MC, Topol SE, Rueda M, et al. Mutation of WIF1: a potential novel cause of a nail-patella–like disorder. Genet Med. 2017;19:1179-1183.

- López-Arvizu C, Sparrow EP, Strube MJ, et al. Increased symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and major depressive disorder symptoms in Nail-patella syndrome: potential association with LMX1B loss-of-function. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:59-66.

- Figueroa-Silva O, Vicente A, Agudo A, et al. Nail-patella syndrome: report of 11 pediatric cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016; 30:1614-1617.

- Vollrath D, Jaramillo-Babb VL, Clough MV, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the LIM-homeodomain gene, LMX1B, in nail-patella syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1091-1098. Published correction appears in Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1333.

- Chen H, Lun Y, Ovchinnikov D, et al. Limb and kidney defects in LMX1B mutant mice suggest an involvement of LMX1B in human nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:51-55.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Sweeney E, Hoover-Fong JE, McIntosh I. Nail-patella syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington; 2003.

- Tigchelaar S, Lenting A, Bongers EM, et al. Nail patella syndrome: knee symptoms and surgical outcomes. a questionnaire-based survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:959-962.

- Harita Y, Urae S, Akashio R, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of nephropathy in patients with nail-patella syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:1414-1421.

- Tan ES, Chong WS, Tey HL. Nail psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012; 13:375-388.

- Elewski BE. Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:415-429.

- Iorizzo M, Starace M, Pasch MC. Leukonychia: what can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:177-193.

- Wright JT, Grange DK, Fete M. Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail-Patella Syndrome