User login

Painful Oral, Groin, and Scalp Lesions in a Young Man

Painful Oral, Groin, and Scalp Lesions in a Young Man

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pemphigus Vegetans

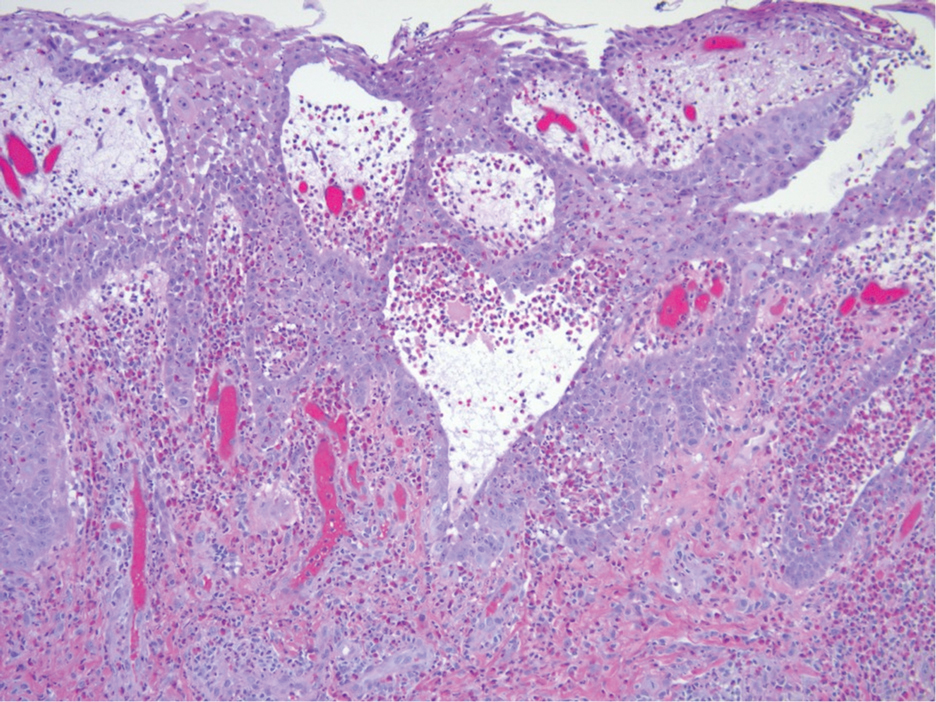

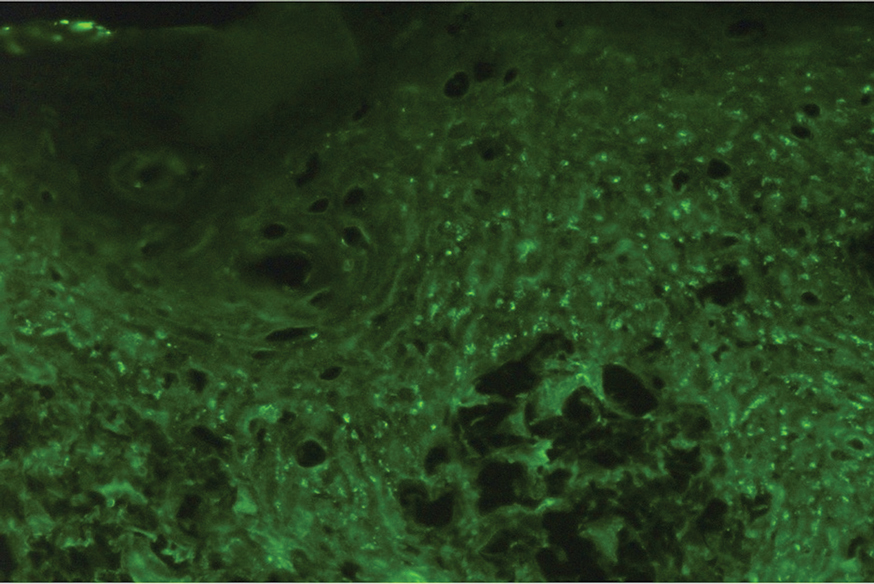

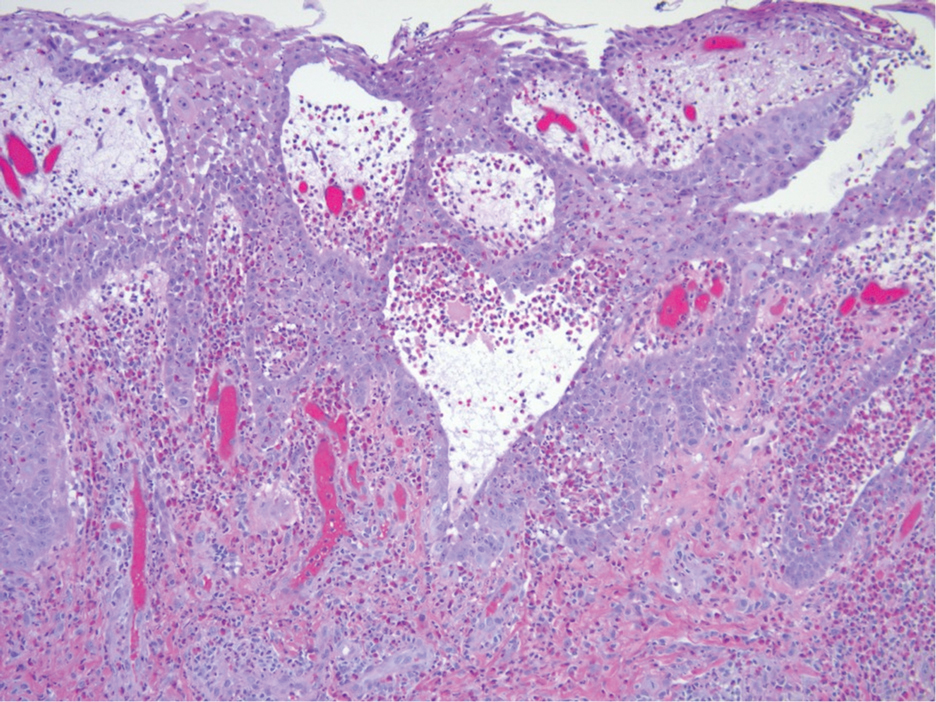

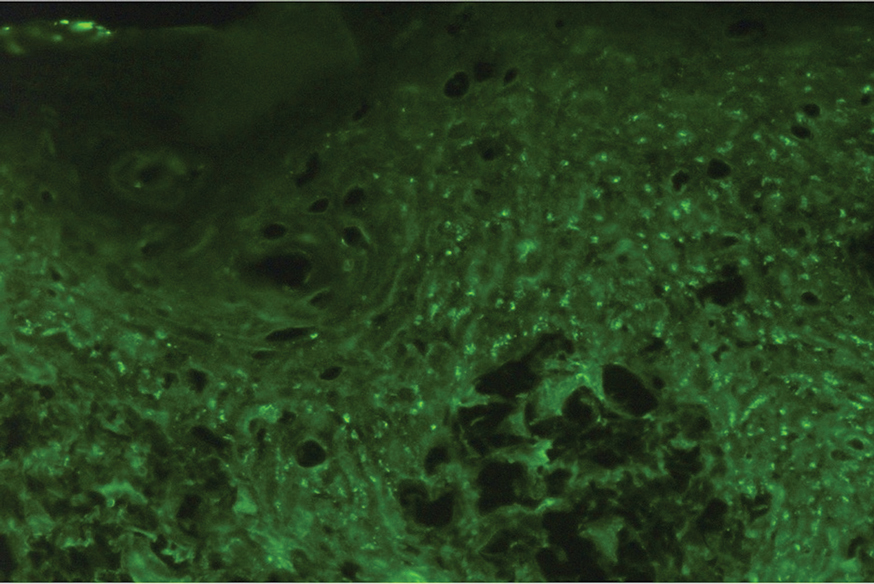

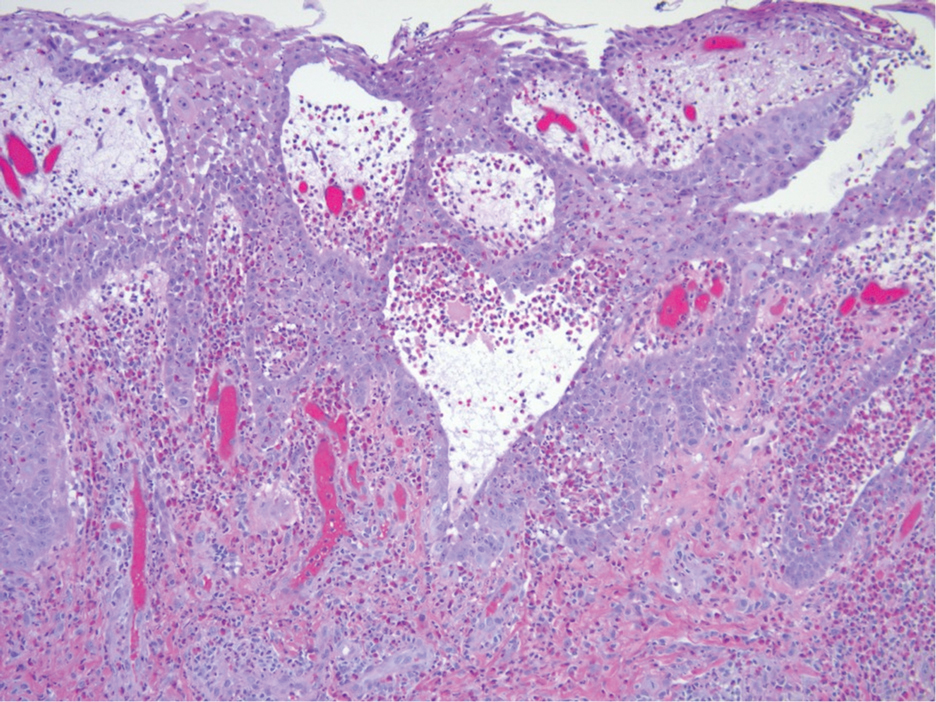

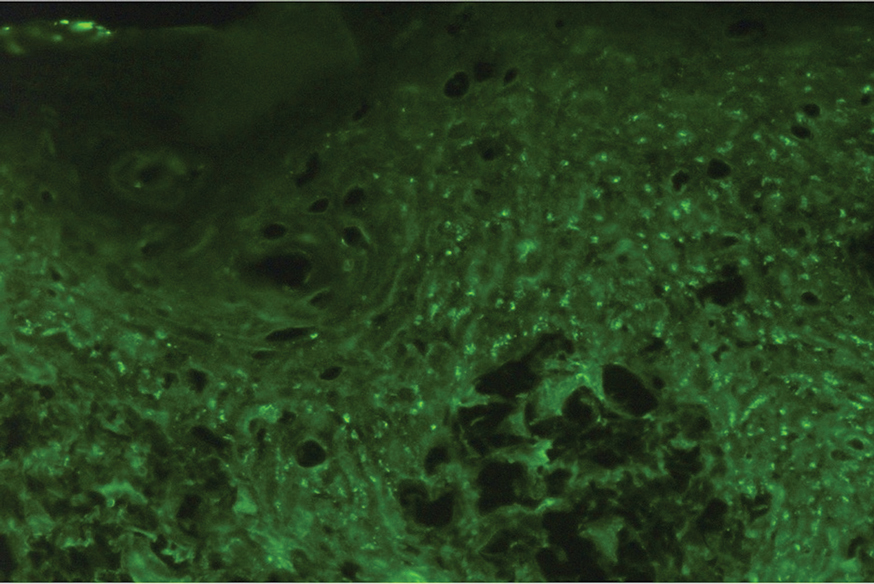

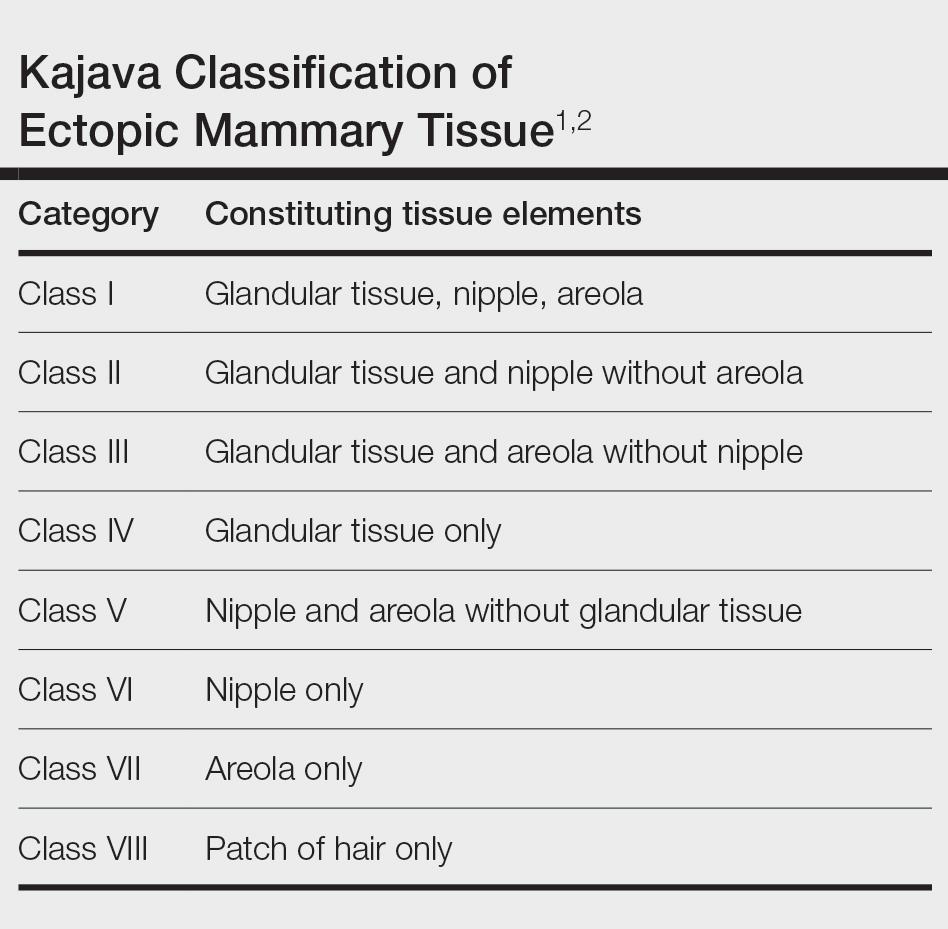

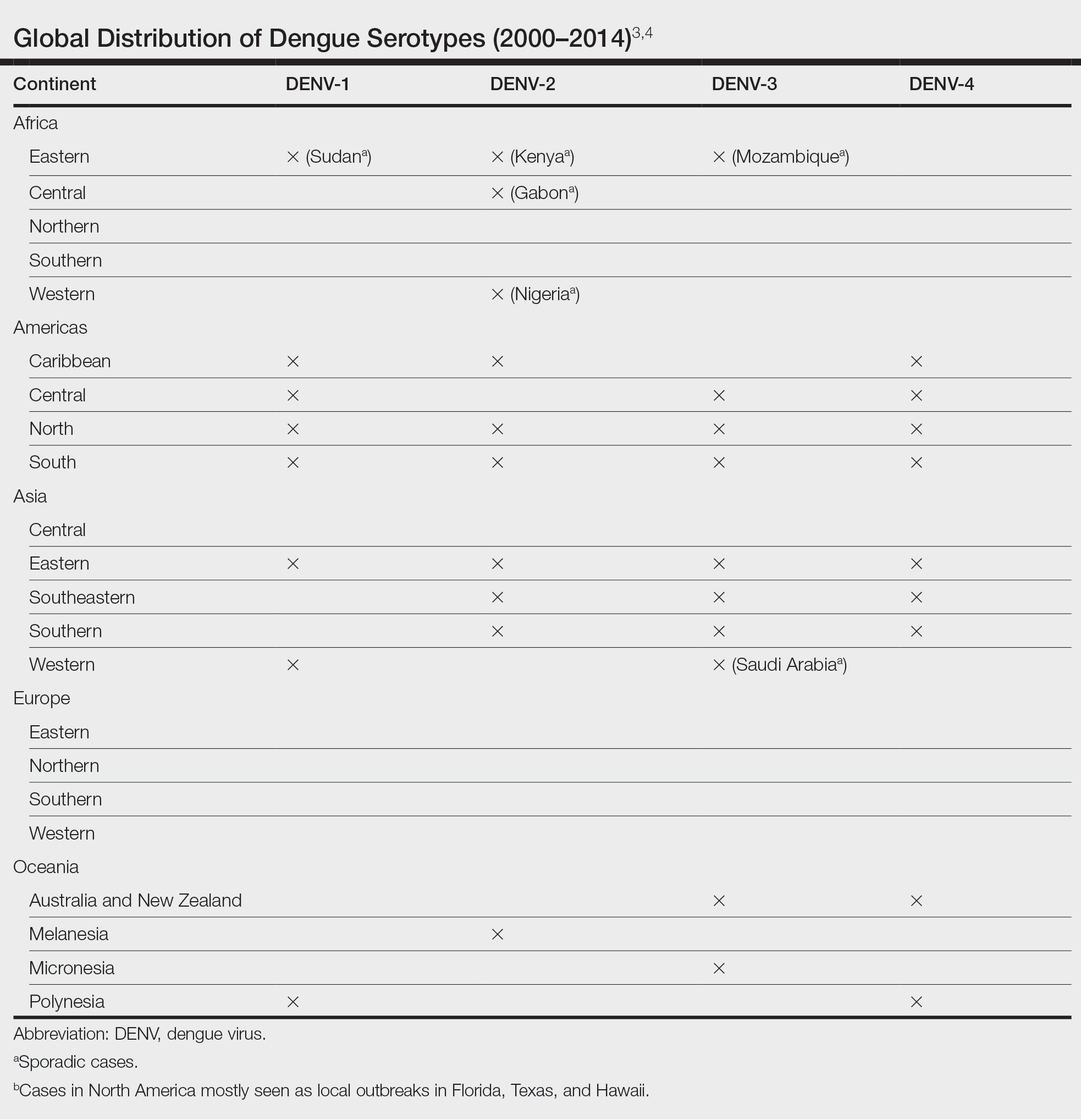

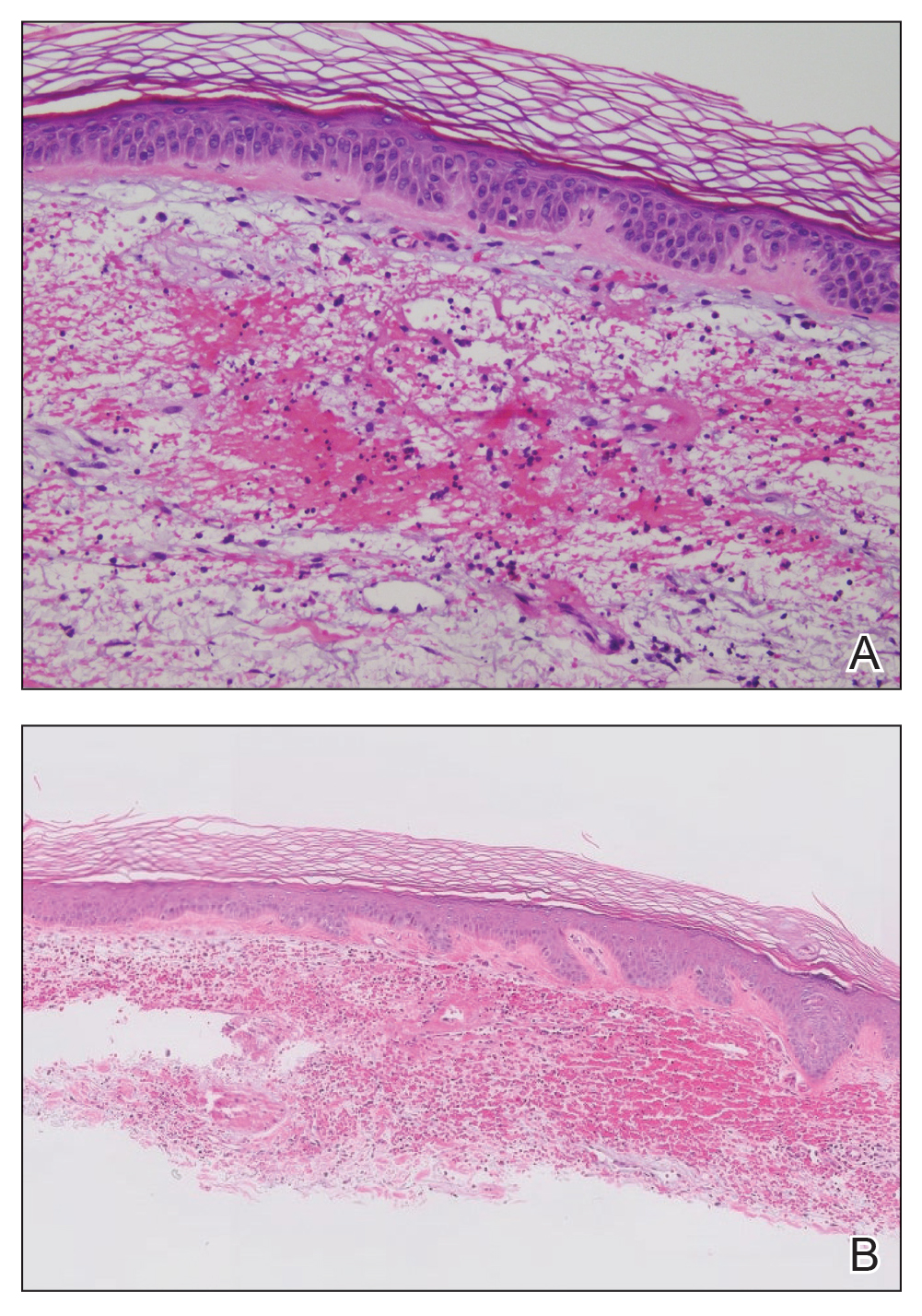

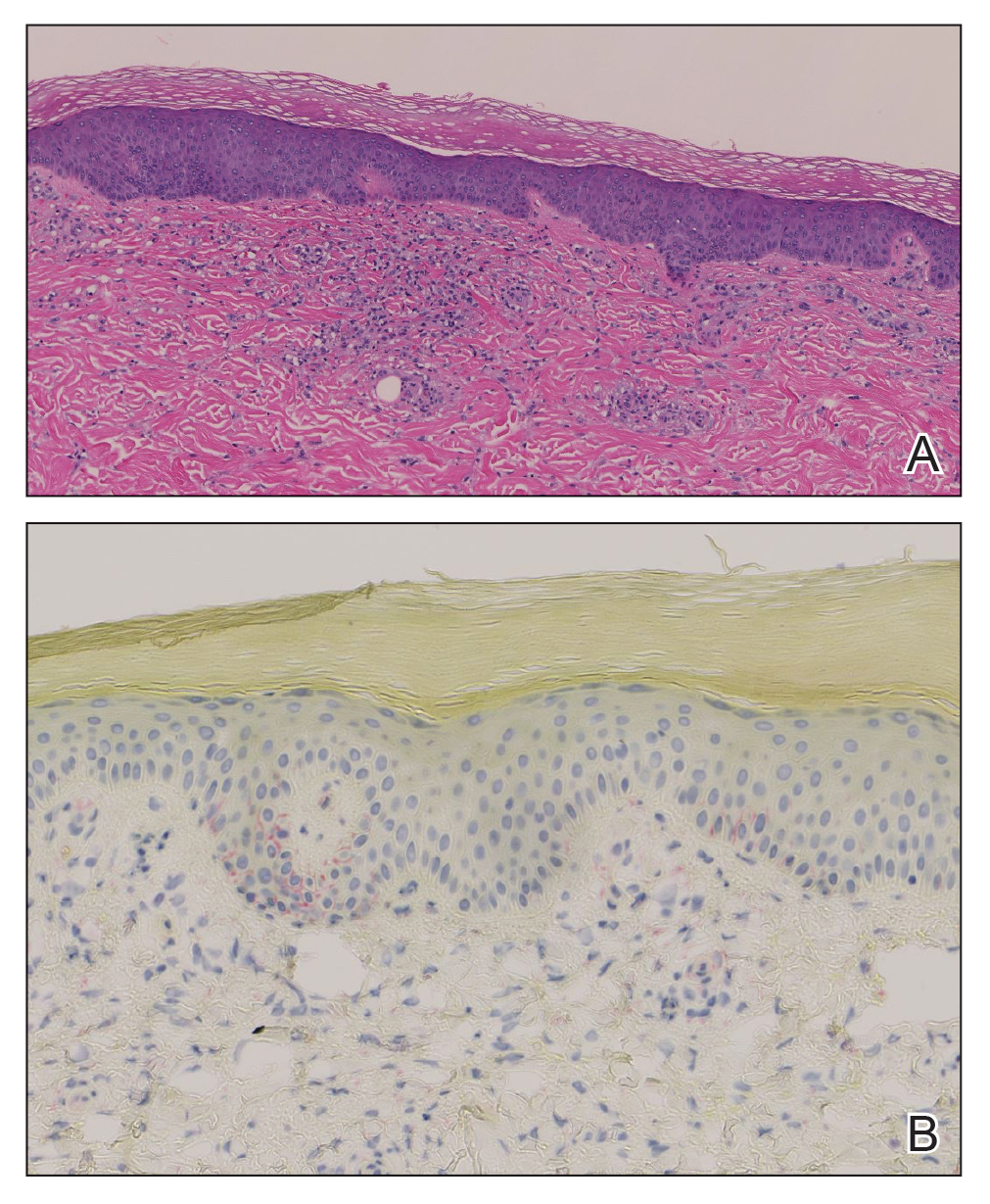

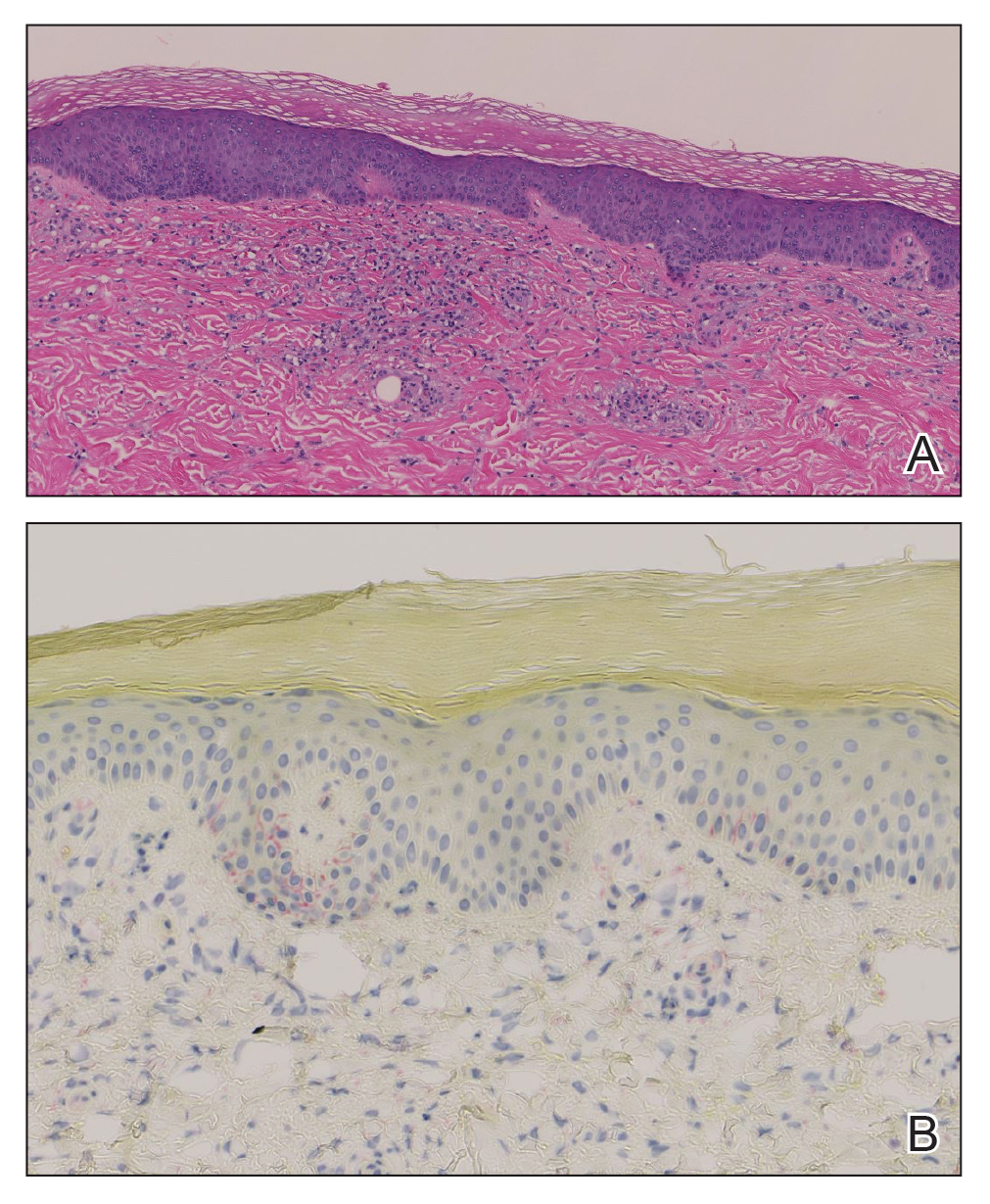

Histopathologic examination of the biopsies from the scalp and left anterior thigh revealed suprabasal clefting with acantholytic cells extending into the follicular infundibulum with eosinophilic pustules within the epidermis. The dermis contained perivascular lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates without viral cytopathic effects (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed strong IgG and moderate IgA pericellular deposition around keratinocyte cytoplasms (Figure 2). Serologic evaluation demonstrated anti–desmoglein 3 antibodies. Based on the clinical presentation and histopathologic correlation, a diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans was made.

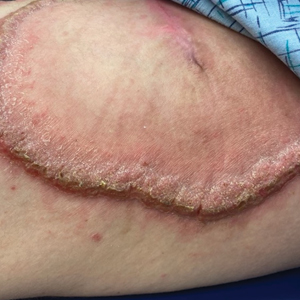

Pemphigus vegetans is a vesiculobullous autoimmune disease that is similar to pemphigus vulgaris but is characterized by the formation of vegetative plaques along the intertriginous areas and on the oral mucosa.1 It is the rarest variant of all pemphigus subtypes and was first described by Neumann in 1876.2 There are 2 subtypes of this variant: Hallopeau and Neumann, each with unique characteristics and physical manifestations. The Hallopeau type initially manifests with pustular lesions that rupture and evolve into erosions that commonly become infected. Gradually they merge and multiply to become more painful and vegetative.3 It has a more indolent course and typically responds well to treatment, and prolonged remission can be reached.4 The Neumann type is more severe and manifests with large vesiculobullous and erosive lesions that rupture and ulcerate, forming verrucous crusted vegetative plaques over the erosions.5 The erosions along the edge of the lesions induce new vegetation, becoming dry, hyperkeratotic, and fissured.3 The Neumann type often requires higher-dose steroids and typically is resistant to treatment.4 Patients can present with oral stomatitis and occasionally can develop a fissured or cerebriform appearance of the tongue, as seen in our patient (Figure 3).1,2 Nail changes include onychorrhexis, onychomadesis, subungual pustules, and ultimately nail atrophy.5

Pemphigus diseases are characterized by IgG autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 and/or desmoglein 1. These are components of desmosomes that are responsible for keratinocyte adhesion, disruption of which results in the blister formation seen in pemphigus subtypes. The unique physical manifestation of pemphigus vegetans is thought to be due not only to autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3 but also to autoantibodies against desmocollin 1 and 2.1

Histopathologic examination reveals hyperkeratosis and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with acantholysis that creates a suprabasal cleft. Basal cells remain intact to the basement membrane by hemidesmosomes, resulting in a tombstone appearance. The Hallopeau type typically manifests with a large eosinophilic inflammatory response, leading to eosinophilic spongiosis and intraepidermal microabscesses. The Neumann type manifests with more of a neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltrate, accompanied by the eosinophilic response.1 For evaluation, obtain histopathology as well as direct immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to look for intracellular deposition of desmoglein autoantibodies.

First-line treatment for pemphigus vulgaris and its variants is rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. It has also been shown to have therapeutic benefit with combination of corticosteroids and rituximab. Corticosteroids should be given at a dose of 1 mg/kg daily for 2 to 4 weeks. Other immunosuppressive agents (steroid sparing) include azathioprine, dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Pulse therapy with intermittent intravenous corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is another second-line therapeutic option. Topical therapeutic options include steroids, tacrolimus, and nicotinamide with oral tetracycline at onset and relapse. The goal of therapy is to maintain remission for 1 year then slowly taper treatment over another year.1

Our patient initially was treated with prednisone, and subsequent courses of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil failed. He then was treated with 2 infusions of rituximab that were given 2 weeks apart. He was able to taper off the prednisone 1 month after the last infusion with complete remission of disease. He has been disease free for more than 9 months postinfusion.

Differential diagnoses for pemphigus vegetans can include bullous pemphigoid, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, and pemphigus vulgaris. Lesion characteristics are key to differentiating pemphigus vegetans from other autoimmune blistering disorders. Bullous pemphigoid will manifest with tense blisters where pemphigus vulgaris will be flaccid; this is due to the difference in autoantibody targets between the conditions. Diagnosis depends on clinical presentation and histopathologic findings.

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

- Rebello MS, Ramesh BM, Sukumar D, et al. Cerebriform cutaneous lesions in pemphigus vegetans. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:206-208.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Ajbani AA, Mehta KS, Marfatia YS. Verrucous lesions over external genitalia as a presenting feature of pemphigus vegetans. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2019;40:176-179.

- Vinay K, De D, Handa S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans presenting as a verrucous plaque on the finger. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:316-317.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pemphigus Vegetans

Histopathologic examination of the biopsies from the scalp and left anterior thigh revealed suprabasal clefting with acantholytic cells extending into the follicular infundibulum with eosinophilic pustules within the epidermis. The dermis contained perivascular lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates without viral cytopathic effects (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed strong IgG and moderate IgA pericellular deposition around keratinocyte cytoplasms (Figure 2). Serologic evaluation demonstrated anti–desmoglein 3 antibodies. Based on the clinical presentation and histopathologic correlation, a diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans was made.

Pemphigus vegetans is a vesiculobullous autoimmune disease that is similar to pemphigus vulgaris but is characterized by the formation of vegetative plaques along the intertriginous areas and on the oral mucosa.1 It is the rarest variant of all pemphigus subtypes and was first described by Neumann in 1876.2 There are 2 subtypes of this variant: Hallopeau and Neumann, each with unique characteristics and physical manifestations. The Hallopeau type initially manifests with pustular lesions that rupture and evolve into erosions that commonly become infected. Gradually they merge and multiply to become more painful and vegetative.3 It has a more indolent course and typically responds well to treatment, and prolonged remission can be reached.4 The Neumann type is more severe and manifests with large vesiculobullous and erosive lesions that rupture and ulcerate, forming verrucous crusted vegetative plaques over the erosions.5 The erosions along the edge of the lesions induce new vegetation, becoming dry, hyperkeratotic, and fissured.3 The Neumann type often requires higher-dose steroids and typically is resistant to treatment.4 Patients can present with oral stomatitis and occasionally can develop a fissured or cerebriform appearance of the tongue, as seen in our patient (Figure 3).1,2 Nail changes include onychorrhexis, onychomadesis, subungual pustules, and ultimately nail atrophy.5

Pemphigus diseases are characterized by IgG autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 and/or desmoglein 1. These are components of desmosomes that are responsible for keratinocyte adhesion, disruption of which results in the blister formation seen in pemphigus subtypes. The unique physical manifestation of pemphigus vegetans is thought to be due not only to autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3 but also to autoantibodies against desmocollin 1 and 2.1

Histopathologic examination reveals hyperkeratosis and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with acantholysis that creates a suprabasal cleft. Basal cells remain intact to the basement membrane by hemidesmosomes, resulting in a tombstone appearance. The Hallopeau type typically manifests with a large eosinophilic inflammatory response, leading to eosinophilic spongiosis and intraepidermal microabscesses. The Neumann type manifests with more of a neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltrate, accompanied by the eosinophilic response.1 For evaluation, obtain histopathology as well as direct immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to look for intracellular deposition of desmoglein autoantibodies.

First-line treatment for pemphigus vulgaris and its variants is rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. It has also been shown to have therapeutic benefit with combination of corticosteroids and rituximab. Corticosteroids should be given at a dose of 1 mg/kg daily for 2 to 4 weeks. Other immunosuppressive agents (steroid sparing) include azathioprine, dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Pulse therapy with intermittent intravenous corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is another second-line therapeutic option. Topical therapeutic options include steroids, tacrolimus, and nicotinamide with oral tetracycline at onset and relapse. The goal of therapy is to maintain remission for 1 year then slowly taper treatment over another year.1

Our patient initially was treated with prednisone, and subsequent courses of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil failed. He then was treated with 2 infusions of rituximab that were given 2 weeks apart. He was able to taper off the prednisone 1 month after the last infusion with complete remission of disease. He has been disease free for more than 9 months postinfusion.

Differential diagnoses for pemphigus vegetans can include bullous pemphigoid, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, and pemphigus vulgaris. Lesion characteristics are key to differentiating pemphigus vegetans from other autoimmune blistering disorders. Bullous pemphigoid will manifest with tense blisters where pemphigus vulgaris will be flaccid; this is due to the difference in autoantibody targets between the conditions. Diagnosis depends on clinical presentation and histopathologic findings.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pemphigus Vegetans

Histopathologic examination of the biopsies from the scalp and left anterior thigh revealed suprabasal clefting with acantholytic cells extending into the follicular infundibulum with eosinophilic pustules within the epidermis. The dermis contained perivascular lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates without viral cytopathic effects (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed strong IgG and moderate IgA pericellular deposition around keratinocyte cytoplasms (Figure 2). Serologic evaluation demonstrated anti–desmoglein 3 antibodies. Based on the clinical presentation and histopathologic correlation, a diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans was made.

Pemphigus vegetans is a vesiculobullous autoimmune disease that is similar to pemphigus vulgaris but is characterized by the formation of vegetative plaques along the intertriginous areas and on the oral mucosa.1 It is the rarest variant of all pemphigus subtypes and was first described by Neumann in 1876.2 There are 2 subtypes of this variant: Hallopeau and Neumann, each with unique characteristics and physical manifestations. The Hallopeau type initially manifests with pustular lesions that rupture and evolve into erosions that commonly become infected. Gradually they merge and multiply to become more painful and vegetative.3 It has a more indolent course and typically responds well to treatment, and prolonged remission can be reached.4 The Neumann type is more severe and manifests with large vesiculobullous and erosive lesions that rupture and ulcerate, forming verrucous crusted vegetative plaques over the erosions.5 The erosions along the edge of the lesions induce new vegetation, becoming dry, hyperkeratotic, and fissured.3 The Neumann type often requires higher-dose steroids and typically is resistant to treatment.4 Patients can present with oral stomatitis and occasionally can develop a fissured or cerebriform appearance of the tongue, as seen in our patient (Figure 3).1,2 Nail changes include onychorrhexis, onychomadesis, subungual pustules, and ultimately nail atrophy.5

Pemphigus diseases are characterized by IgG autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 and/or desmoglein 1. These are components of desmosomes that are responsible for keratinocyte adhesion, disruption of which results in the blister formation seen in pemphigus subtypes. The unique physical manifestation of pemphigus vegetans is thought to be due not only to autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3 but also to autoantibodies against desmocollin 1 and 2.1

Histopathologic examination reveals hyperkeratosis and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with acantholysis that creates a suprabasal cleft. Basal cells remain intact to the basement membrane by hemidesmosomes, resulting in a tombstone appearance. The Hallopeau type typically manifests with a large eosinophilic inflammatory response, leading to eosinophilic spongiosis and intraepidermal microabscesses. The Neumann type manifests with more of a neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltrate, accompanied by the eosinophilic response.1 For evaluation, obtain histopathology as well as direct immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to look for intracellular deposition of desmoglein autoantibodies.

First-line treatment for pemphigus vulgaris and its variants is rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. It has also been shown to have therapeutic benefit with combination of corticosteroids and rituximab. Corticosteroids should be given at a dose of 1 mg/kg daily for 2 to 4 weeks. Other immunosuppressive agents (steroid sparing) include azathioprine, dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Pulse therapy with intermittent intravenous corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is another second-line therapeutic option. Topical therapeutic options include steroids, tacrolimus, and nicotinamide with oral tetracycline at onset and relapse. The goal of therapy is to maintain remission for 1 year then slowly taper treatment over another year.1

Our patient initially was treated with prednisone, and subsequent courses of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil failed. He then was treated with 2 infusions of rituximab that were given 2 weeks apart. He was able to taper off the prednisone 1 month after the last infusion with complete remission of disease. He has been disease free for more than 9 months postinfusion.

Differential diagnoses for pemphigus vegetans can include bullous pemphigoid, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, and pemphigus vulgaris. Lesion characteristics are key to differentiating pemphigus vegetans from other autoimmune blistering disorders. Bullous pemphigoid will manifest with tense blisters where pemphigus vulgaris will be flaccid; this is due to the difference in autoantibody targets between the conditions. Diagnosis depends on clinical presentation and histopathologic findings.

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

- Rebello MS, Ramesh BM, Sukumar D, et al. Cerebriform cutaneous lesions in pemphigus vegetans. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:206-208.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Ajbani AA, Mehta KS, Marfatia YS. Verrucous lesions over external genitalia as a presenting feature of pemphigus vegetans. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2019;40:176-179.

- Vinay K, De D, Handa S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans presenting as a verrucous plaque on the finger. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:316-317.

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

- Rebello MS, Ramesh BM, Sukumar D, et al. Cerebriform cutaneous lesions in pemphigus vegetans. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:206-208.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Ajbani AA, Mehta KS, Marfatia YS. Verrucous lesions over external genitalia as a presenting feature of pemphigus vegetans. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2019;40:176-179.

- Vinay K, De D, Handa S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans presenting as a verrucous plaque on the finger. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:316-317.

Painful Oral, Groin, and Scalp Lesions in a Young Man

Painful Oral, Groin, and Scalp Lesions in a Young Man

A 27-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with painful oral and groin lesions of 2 years’ duration as well as lip ulceration that had been present for 1 month. The patient also reported moderately tender scalp and face lesions that had been present for several weeks. The lip ulceration was previously treated by his primary care provider with valacyclovir (1 g daily for 2 weeks) without improvement. Six months prior to the current presentation, we treated the groin lesions as condyloma involving the perineum and genital region at our clinic with no response to cryotherapy, topical imiquimod, or extensive surgical excision with skin grafting. Pathology at the time showed condyloma but was negative for human papillomavirus. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed superficial erosions along the vermilion border. The oral mucosa exhibited cobblestoning, and fissures were present on the tongue. Eroded pink plaques studded with vesicles were present on the vertex scalp and left chin. The bilateral inguinal regions extending to anterior-lateral upper thighs and posterior buttocks revealed erythematous, arcuate, and annular erosive plaques with verrucous hyperkeratotic borders and fissuring on the leading edge. Pink erosive and verrucous erythematous plaques were noted on the penile shaft, scrotum, and perineum. Punch biopsies of the scalp and left anterior thigh as well as direct immunofluorescence were performed.

Demarcated Nonpruritic Lesions Following Antibiotic Therapy

Demarcated Nonpruritic Lesions Following Antibiotic Therapy

THE DIAGNOSIS: Fixed Drug Eruption

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation and history of similar eruptions, a diagnosis of levofloxacin-induced fixed drug eruption (FDE) was made. After cessation of the drug, the lesions resolved within 1 week without any residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Fixed drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction characterized by the onset of a rash at a fixed location each time a specific medication is administered. Patients typically report a history of similar eruptions, often involving the upper and lower extremities, genital area, or mucous membranes. The most common causative agents vary, but retrospective analyses primarily implicate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs followed by antibiotics (eg, amoxicillin, levofloxacin, doxycycline) and antiepileptics.1,2

While FDE can be solitary or scattered, most patients have 5 or fewer lesions, with a mean interval of 48 hours from exposure to the causative agent to onset of the rash.1 The lesions can be differentiated by their typically solitary, well-demarcated, round or oval appearance; they also are erythematous to purple with a dusky center. The lesions may increase in size and number with each additional exposure to the offending medication.1,3 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may last for weeks to months after the acute inflammatory response has resolved.

The high risk for recurrence of FDE may be explained by the presence of tissue resident memory T (TRM) cells in the affected skin that evoke a characteristic clinical manifestation upon administration of a causative agent.2,3 Intraepidermal CD8+ TRM cells, which have an effectormemory phenotype, may contribute to the development of localized tissue damage; these cells demonstrate their effector function by the rapid increase in interferon gamma after challenge.2 Within 24 hours of administration of the offending medication, CD8+ TRM cells migrate upward in the epidermis, and their activity leads to the epidermal necrosis observed with FDE. The self-limiting nature of FDE can be explained by the action of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells that migrate similarly and induce the production of IL-10, which limits the damage inflicted by the CD8+ T cells.1

Type I hypersensitivity reactions are IgE mediated; typically occur much more rapidly than FDE; and involve a raised urticarial rash, pruritus, and flushing. Urticaria is useful in identifying IgE-mediated reactions and mast cell degranulation. Previous exposure to the drug in question is required for diagnosis.4

Type IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions—including contact dermatitis and FDE—are mediated by T cells rather than IgE. These reactions occur at least 48 to 72 hours after drug exposure.4 Contact dermatitis follows exposure to an irritant but generally is limited to the site of contact and manifests with burning or stinging. Chronic contact dermatitis is characterized by erythema, scaling, and lichenification that may be associated with burning pain.

The target lesions of erythema multiforme are associated with the use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiepileptics, and antibiotics in fewer than 10% of cases. Infections are the predominant cause, with herpes simplex virus 1 being the most common etiology.5 Erythema multiforme lesions have 3 concentric segments: a dark red inflammatory zone surrounded by a pale ring of edema, both of which are surrounded by an erythematous halo. Lesions initially are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, but mucosal involvement may be present.5

Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, involves fever and peripheral neutrophilia in addition to cutaneous erythematous eruptions and dermal neutrophilic infiltration on histopathology.6 Most cases are idiopathic but may occur in the setting of malignancy or drug administration. A major criterion for drug-induced Sweet syndrome is abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules with pyrexia.6

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925. doi:10.3390/medicina57090925

- Tokura Y, Phadungsaksawasdi P, Kurihara K, et al. Pathophysiology of skin resident memory T cells. Front Immunol. 2021;11:618897. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.618897

- Mockenhaupt M. Bullous drug reactions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00057. doi:10.2340/00015555-3408

- Böhm R, Proksch E, Schwarz T, et al. Drug hypersensitivity. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:501-512. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0501

- Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

- Joshi TP, Friske SK, Hsiou DA, et al. New practical aspects of Sweet syndrome. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:301-318. doi:10.1007 /s40257-022-00673-4

THE DIAGNOSIS: Fixed Drug Eruption

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation and history of similar eruptions, a diagnosis of levofloxacin-induced fixed drug eruption (FDE) was made. After cessation of the drug, the lesions resolved within 1 week without any residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Fixed drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction characterized by the onset of a rash at a fixed location each time a specific medication is administered. Patients typically report a history of similar eruptions, often involving the upper and lower extremities, genital area, or mucous membranes. The most common causative agents vary, but retrospective analyses primarily implicate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs followed by antibiotics (eg, amoxicillin, levofloxacin, doxycycline) and antiepileptics.1,2

While FDE can be solitary or scattered, most patients have 5 or fewer lesions, with a mean interval of 48 hours from exposure to the causative agent to onset of the rash.1 The lesions can be differentiated by their typically solitary, well-demarcated, round or oval appearance; they also are erythematous to purple with a dusky center. The lesions may increase in size and number with each additional exposure to the offending medication.1,3 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may last for weeks to months after the acute inflammatory response has resolved.

The high risk for recurrence of FDE may be explained by the presence of tissue resident memory T (TRM) cells in the affected skin that evoke a characteristic clinical manifestation upon administration of a causative agent.2,3 Intraepidermal CD8+ TRM cells, which have an effectormemory phenotype, may contribute to the development of localized tissue damage; these cells demonstrate their effector function by the rapid increase in interferon gamma after challenge.2 Within 24 hours of administration of the offending medication, CD8+ TRM cells migrate upward in the epidermis, and their activity leads to the epidermal necrosis observed with FDE. The self-limiting nature of FDE can be explained by the action of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells that migrate similarly and induce the production of IL-10, which limits the damage inflicted by the CD8+ T cells.1

Type I hypersensitivity reactions are IgE mediated; typically occur much more rapidly than FDE; and involve a raised urticarial rash, pruritus, and flushing. Urticaria is useful in identifying IgE-mediated reactions and mast cell degranulation. Previous exposure to the drug in question is required for diagnosis.4

Type IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions—including contact dermatitis and FDE—are mediated by T cells rather than IgE. These reactions occur at least 48 to 72 hours after drug exposure.4 Contact dermatitis follows exposure to an irritant but generally is limited to the site of contact and manifests with burning or stinging. Chronic contact dermatitis is characterized by erythema, scaling, and lichenification that may be associated with burning pain.

The target lesions of erythema multiforme are associated with the use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiepileptics, and antibiotics in fewer than 10% of cases. Infections are the predominant cause, with herpes simplex virus 1 being the most common etiology.5 Erythema multiforme lesions have 3 concentric segments: a dark red inflammatory zone surrounded by a pale ring of edema, both of which are surrounded by an erythematous halo. Lesions initially are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, but mucosal involvement may be present.5

Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, involves fever and peripheral neutrophilia in addition to cutaneous erythematous eruptions and dermal neutrophilic infiltration on histopathology.6 Most cases are idiopathic but may occur in the setting of malignancy or drug administration. A major criterion for drug-induced Sweet syndrome is abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules with pyrexia.6

THE DIAGNOSIS: Fixed Drug Eruption

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation and history of similar eruptions, a diagnosis of levofloxacin-induced fixed drug eruption (FDE) was made. After cessation of the drug, the lesions resolved within 1 week without any residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Fixed drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction characterized by the onset of a rash at a fixed location each time a specific medication is administered. Patients typically report a history of similar eruptions, often involving the upper and lower extremities, genital area, or mucous membranes. The most common causative agents vary, but retrospective analyses primarily implicate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs followed by antibiotics (eg, amoxicillin, levofloxacin, doxycycline) and antiepileptics.1,2

While FDE can be solitary or scattered, most patients have 5 or fewer lesions, with a mean interval of 48 hours from exposure to the causative agent to onset of the rash.1 The lesions can be differentiated by their typically solitary, well-demarcated, round or oval appearance; they also are erythematous to purple with a dusky center. The lesions may increase in size and number with each additional exposure to the offending medication.1,3 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may last for weeks to months after the acute inflammatory response has resolved.

The high risk for recurrence of FDE may be explained by the presence of tissue resident memory T (TRM) cells in the affected skin that evoke a characteristic clinical manifestation upon administration of a causative agent.2,3 Intraepidermal CD8+ TRM cells, which have an effectormemory phenotype, may contribute to the development of localized tissue damage; these cells demonstrate their effector function by the rapid increase in interferon gamma after challenge.2 Within 24 hours of administration of the offending medication, CD8+ TRM cells migrate upward in the epidermis, and their activity leads to the epidermal necrosis observed with FDE. The self-limiting nature of FDE can be explained by the action of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells that migrate similarly and induce the production of IL-10, which limits the damage inflicted by the CD8+ T cells.1

Type I hypersensitivity reactions are IgE mediated; typically occur much more rapidly than FDE; and involve a raised urticarial rash, pruritus, and flushing. Urticaria is useful in identifying IgE-mediated reactions and mast cell degranulation. Previous exposure to the drug in question is required for diagnosis.4

Type IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions—including contact dermatitis and FDE—are mediated by T cells rather than IgE. These reactions occur at least 48 to 72 hours after drug exposure.4 Contact dermatitis follows exposure to an irritant but generally is limited to the site of contact and manifests with burning or stinging. Chronic contact dermatitis is characterized by erythema, scaling, and lichenification that may be associated with burning pain.

The target lesions of erythema multiforme are associated with the use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiepileptics, and antibiotics in fewer than 10% of cases. Infections are the predominant cause, with herpes simplex virus 1 being the most common etiology.5 Erythema multiforme lesions have 3 concentric segments: a dark red inflammatory zone surrounded by a pale ring of edema, both of which are surrounded by an erythematous halo. Lesions initially are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, but mucosal involvement may be present.5

Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, involves fever and peripheral neutrophilia in addition to cutaneous erythematous eruptions and dermal neutrophilic infiltration on histopathology.6 Most cases are idiopathic but may occur in the setting of malignancy or drug administration. A major criterion for drug-induced Sweet syndrome is abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules with pyrexia.6

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925. doi:10.3390/medicina57090925

- Tokura Y, Phadungsaksawasdi P, Kurihara K, et al. Pathophysiology of skin resident memory T cells. Front Immunol. 2021;11:618897. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.618897

- Mockenhaupt M. Bullous drug reactions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00057. doi:10.2340/00015555-3408

- Böhm R, Proksch E, Schwarz T, et al. Drug hypersensitivity. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:501-512. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0501

- Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

- Joshi TP, Friske SK, Hsiou DA, et al. New practical aspects of Sweet syndrome. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:301-318. doi:10.1007 /s40257-022-00673-4

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925. doi:10.3390/medicina57090925

- Tokura Y, Phadungsaksawasdi P, Kurihara K, et al. Pathophysiology of skin resident memory T cells. Front Immunol. 2021;11:618897. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.618897

- Mockenhaupt M. Bullous drug reactions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00057. doi:10.2340/00015555-3408

- Böhm R, Proksch E, Schwarz T, et al. Drug hypersensitivity. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:501-512. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0501

- Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

- Joshi TP, Friske SK, Hsiou DA, et al. New practical aspects of Sweet syndrome. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:301-318. doi:10.1007 /s40257-022-00673-4

Demarcated Nonpruritic Lesions Following Antibiotic Therapy

Demarcated Nonpruritic Lesions Following Antibiotic Therapy

A 35-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for treatment of cellulitis that required antibiotic therapy. Two days after administration of a single dose of intravenous levofloxacin, he developed demarcated nonpruritic and painless lesions on the abdomen (top) and right upper extremity (bottom). He was afebrile through the entire 1-week hospital course and denied use of any topical products prior to hospitalization. The patient reported a history of similar rashes associated with the use of levofloxacin.

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

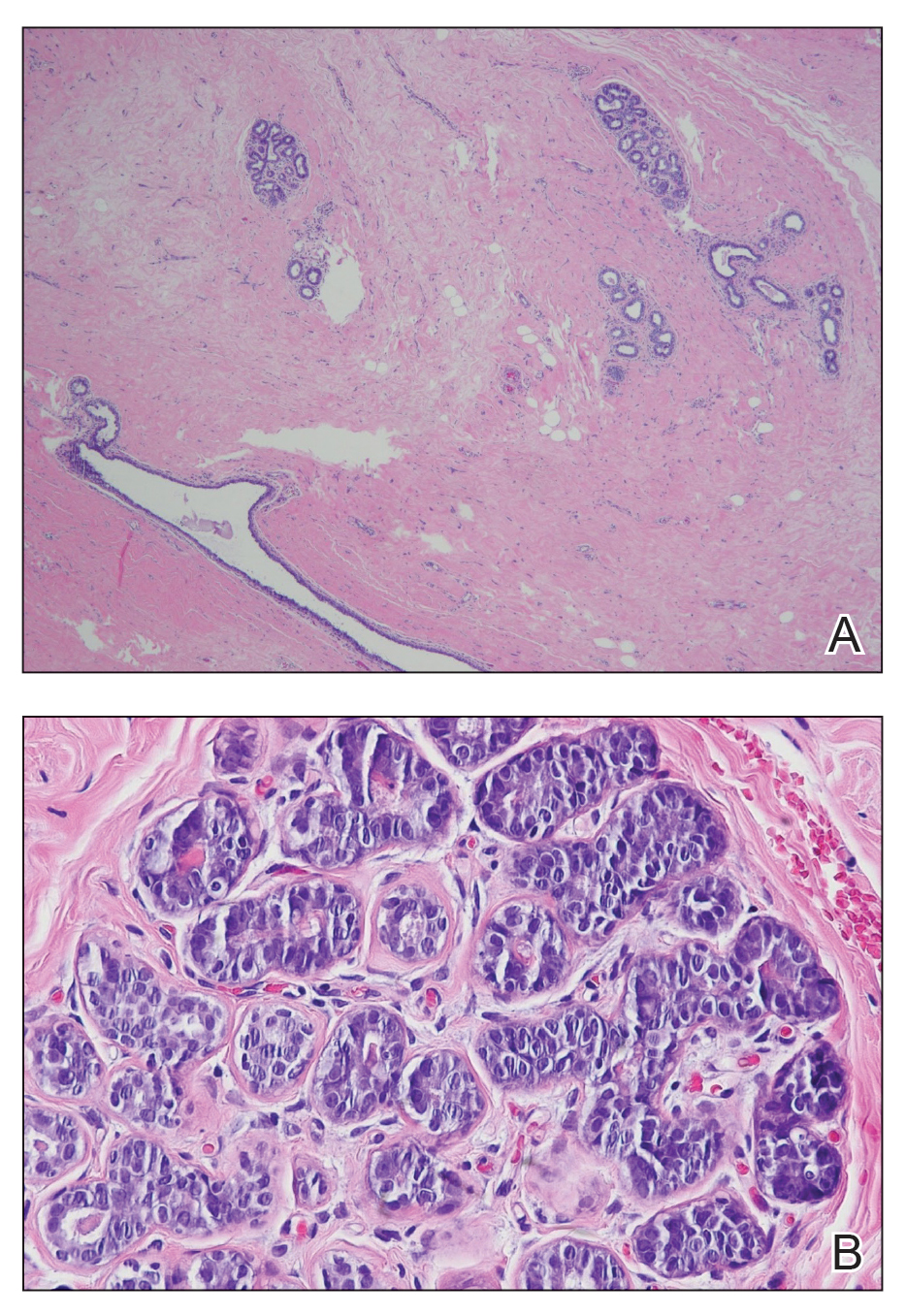

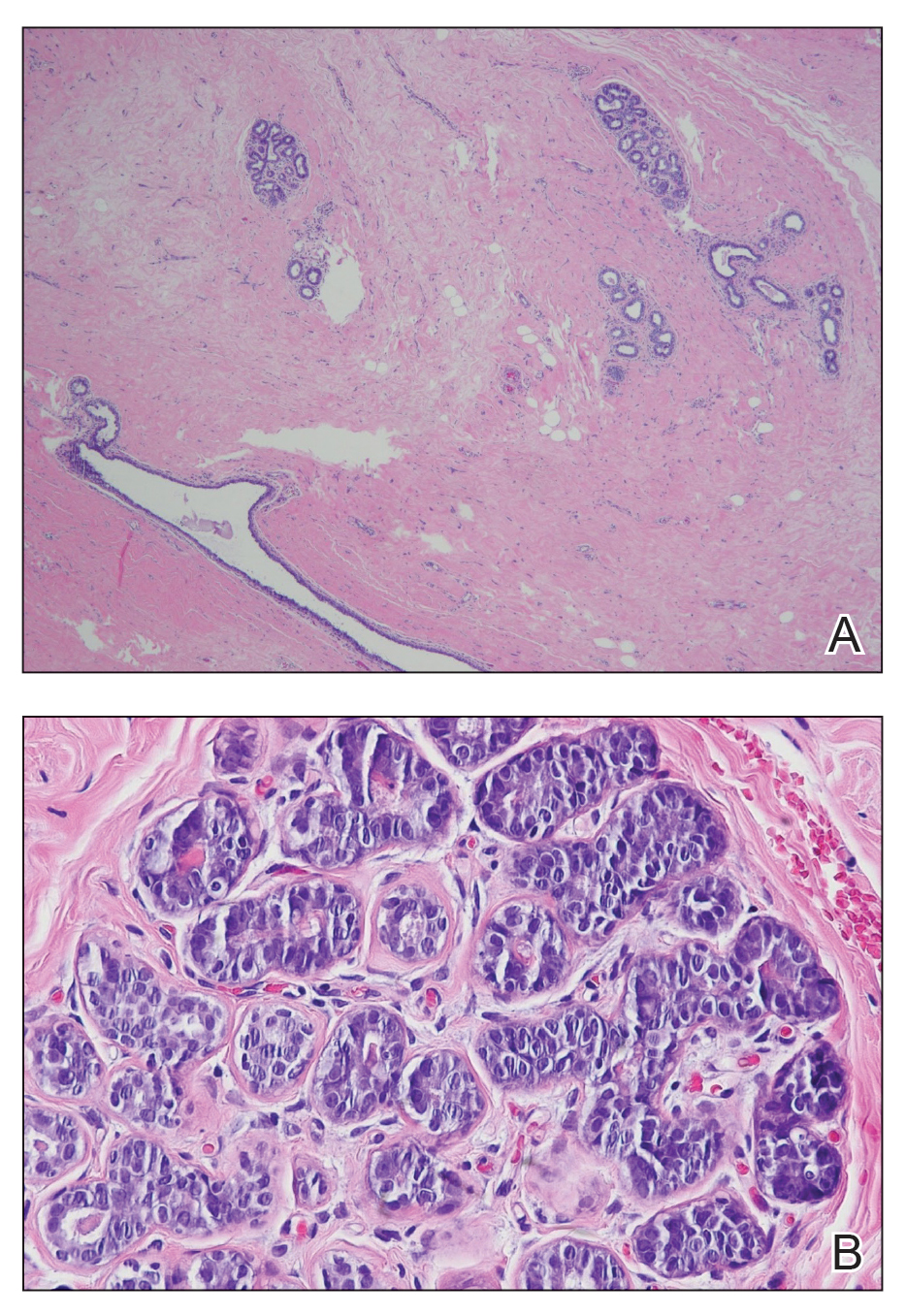

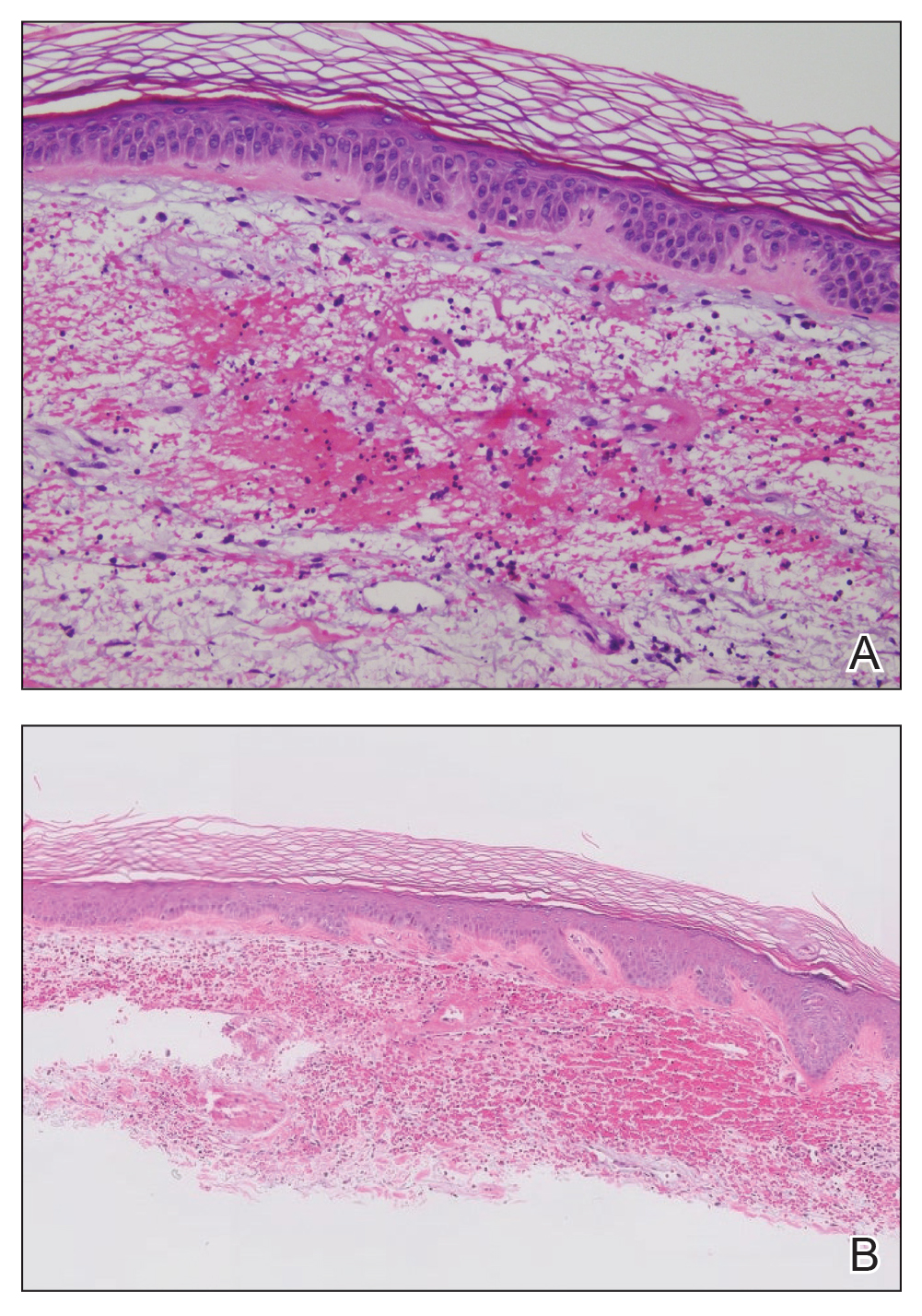

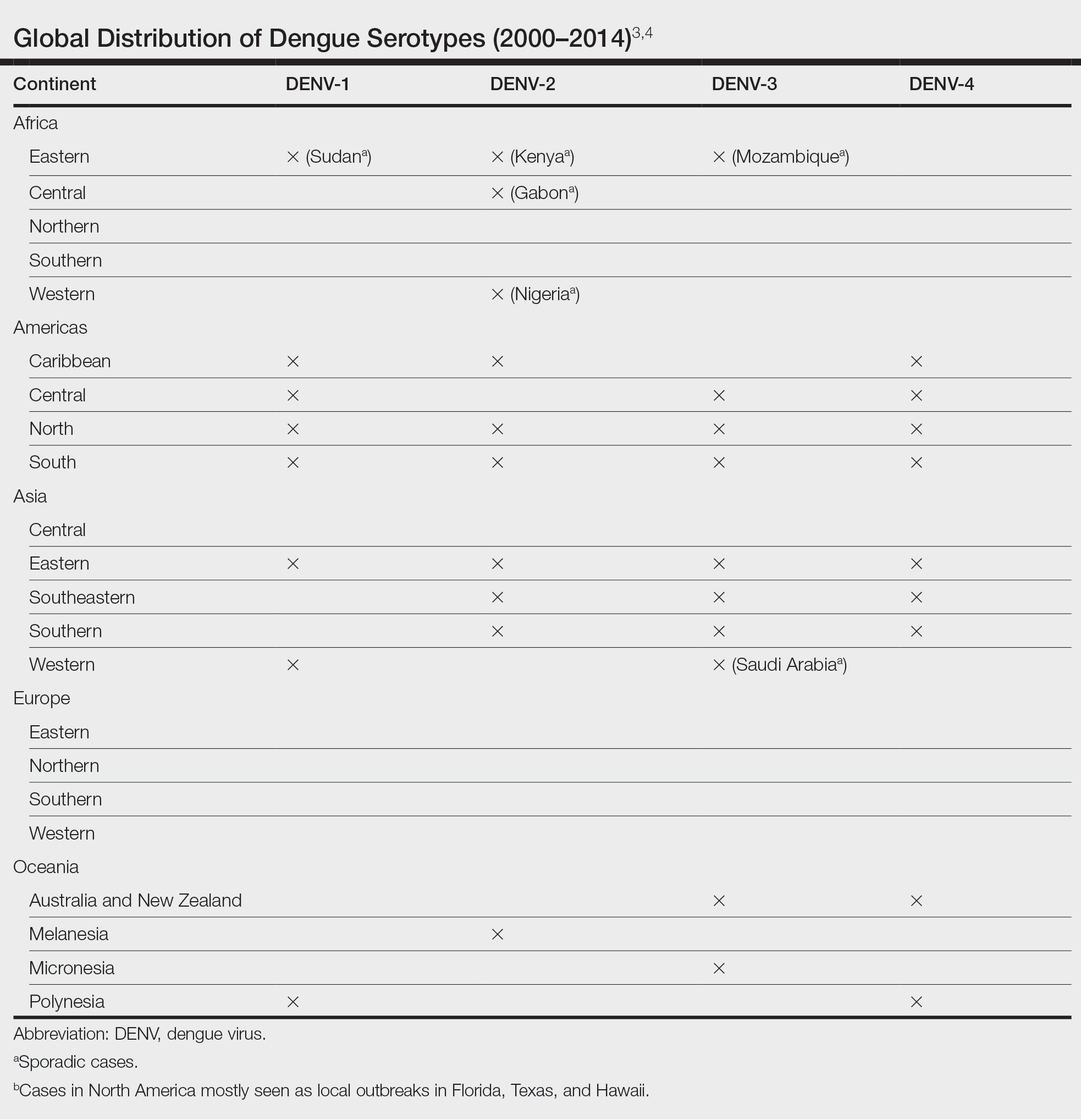

The Diagnosis: Accessory Breast

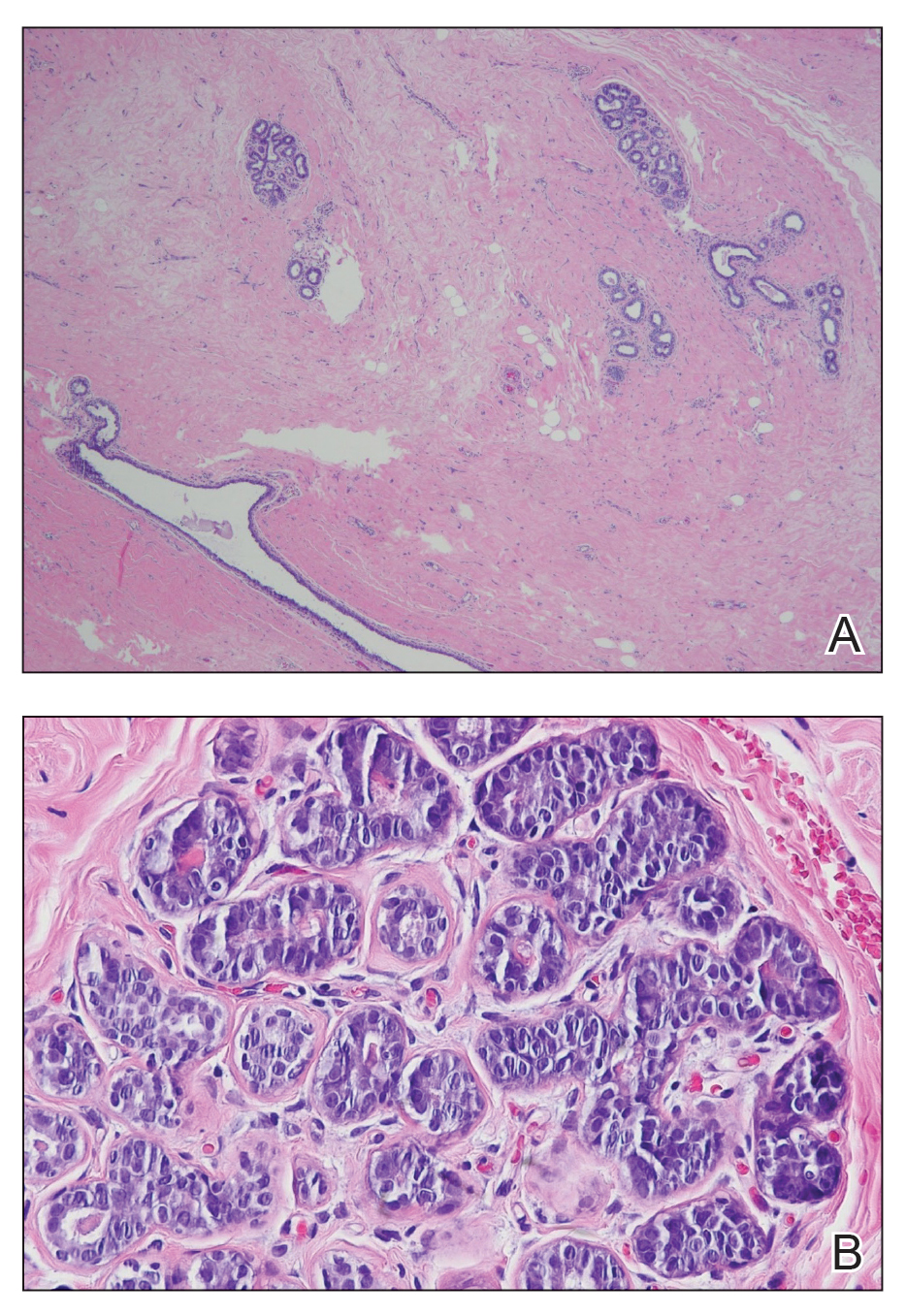

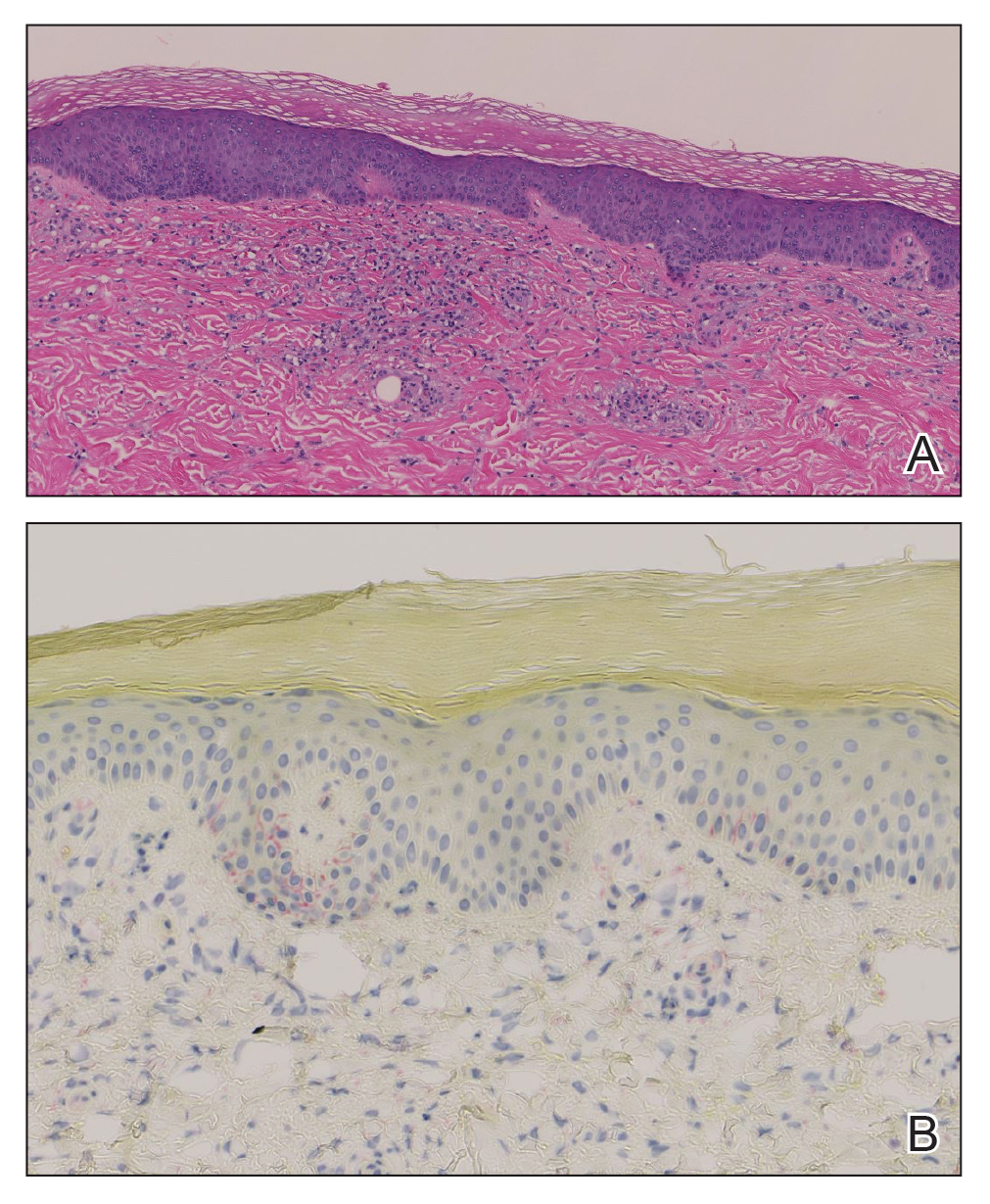

A diagnosis of accessory breast was confirmed on histopathology, which demonstrated a slightly hyperplastic and hyperpigmented epidermis. The dermis contained an increased number of smooth muscle bundles with the presence of apocrine glands and mammary lobules (Figure). Tenderness of the mass fluctuated according to the patient’s menstrual cycle, which supported a diagnosis of accessory breast over lipoma. The patient had no signs of infection or other systemic symptoms that were suggestive of lymphadenopathy. Unlike an epidermoid inclusion cyst, our patient’s mass presented as poorly defined and boggy in texture. Biopsy results were not consistent with malignancy, ruling out soft tissue sarcoma.

B, Myoepithelial cells lined a stratified columnar epithelium, characteristic of breast tissue (H&E, original magnification x40).

Accessory breasts are characterized by the presence of breast tissue outside the breast and can be found anywhere along the milk line from the axillae to the vulva.1 The prevalence of accessory breasts is 2% to 6% of women, with an average age of presentation for treatment of 42 years.2 Ninety percent of accessory breasts are found in the thorax, 5% are found in the abdomen, and 5% are found in the axillae.3 Incidence is uncommon in adolescents; however, in addition to our patient, there are several cases in the literature of adolescents with accessory breasts in the axillae.4,5

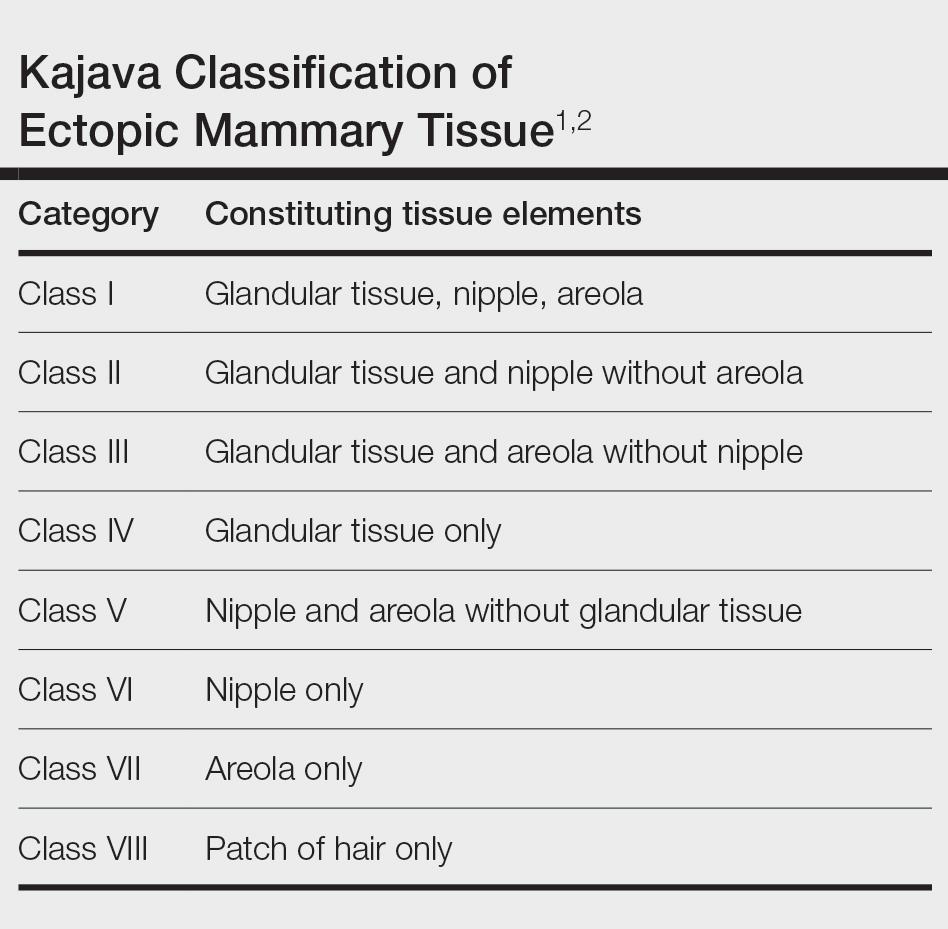

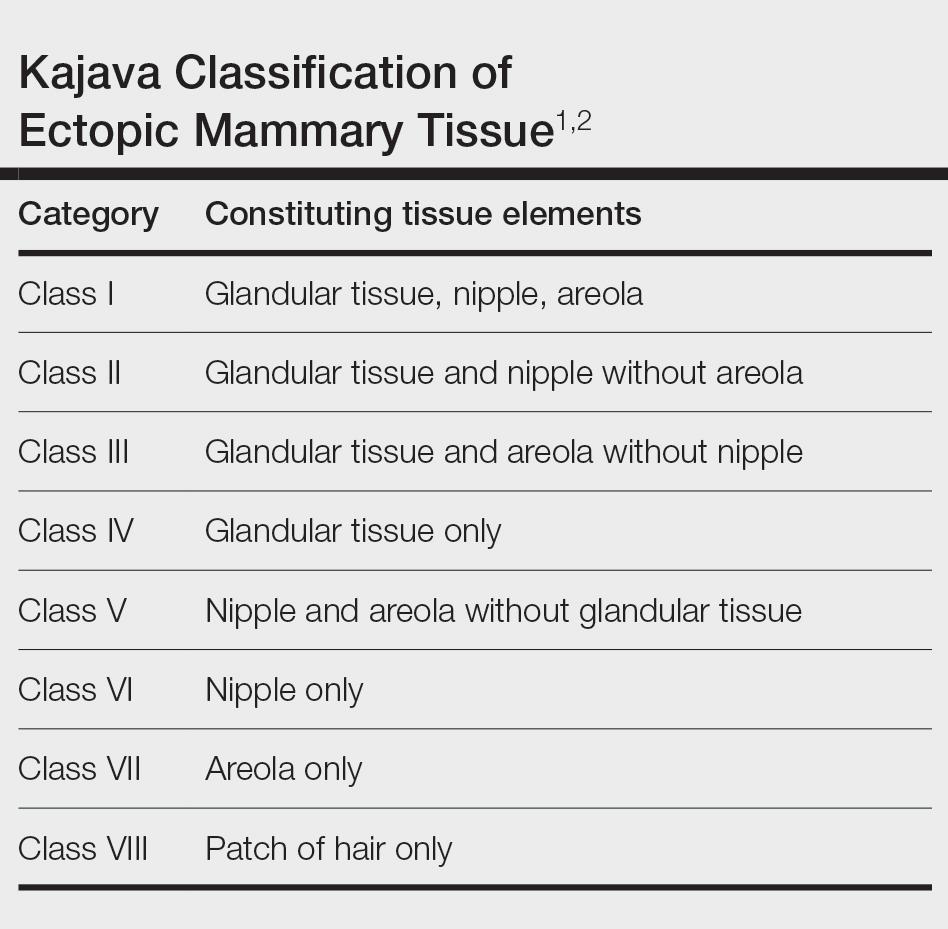

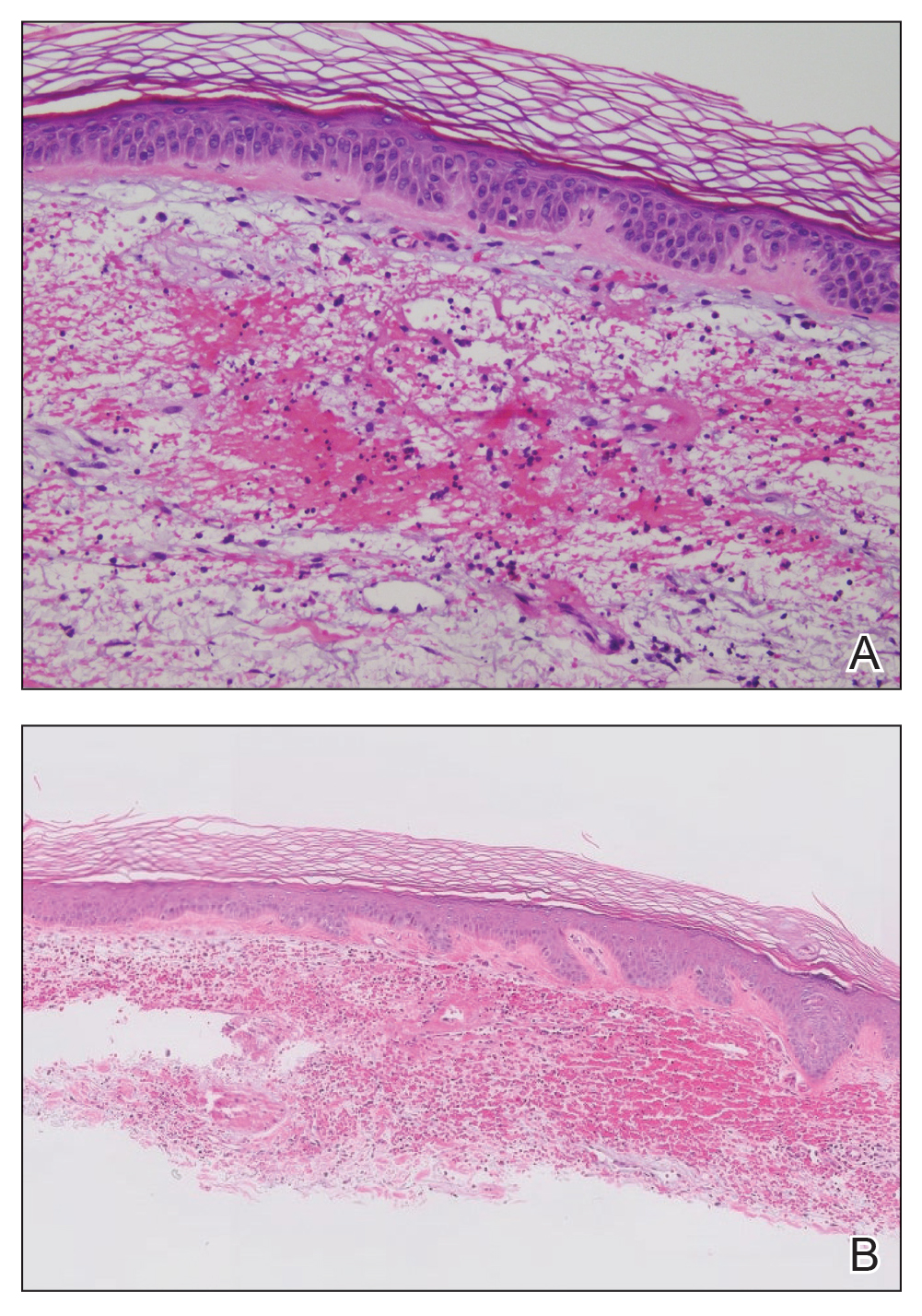

Ectopic mammary tissue is divided into 8 classes based on the Kajava classification system (Table). In a retrospective study of adolescent females with accessory breasts, 91% (10/11) of patients were classified as class IV, and 1 was class II.6 Similarly, our patient was classified as class IV since her accessory breast was composed entirely of glandular tissue and did not include an areola and nipple.

Supernumerary breast structures such as areolas and nipples typically are diagnosed at birth, whereas supernumerary breast tissue is not diagnosed until after hormonal stimulation typically seen during puberty, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Common symptoms include cyclic pain with menstruation, fluctuation in the size of the mass, and tenderness of the ectopic tissue. There also can be restricted range of motion and increased irritation from clothing. Ultrasonography generally shows a hypoechoic septate indicative of mammary tissue.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by histopathologic studies that show mammary lobules in the dermis with smooth muscle, mammary ducts connected to the nipple, and connective stroma.6

If bothersome, ectopic breast tissue can be surgically removed, either by direct excision or suction lipectomy depending on the size of the mass.2 Postoperative complications are low but can include seroma, bleeding, infection, remnant tissue, or undesired cosmetic results. As with normal breast tissue, ectopic breast tissue can manifest with benign and malignant pathologies.

In conclusion, accessory breast is a benign condition that can cause cyclical pain with menstruation, restricted range of motion, discomfort, anxiety, and cosmetic problems. It is important to keep this diagnosis on the differential when evaluating a soft tissue mass that appears in the axillary region.

- Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical and current perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73:525-528.

- Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla: classification and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:35E-36E. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182173f95

- Mazine K, Bouassria A, Elbouhaddouti H. Bilateral supernumerary axillary breasts: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:282. doi:10.11604 /pamj.2020.36.282.20445

- Patel RV, Govani D, Patel R, et al. Adolescent right axillary accessory breast with galactorrhoea. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204215. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204215

- Surd A, Mironescu A, Gocan H. Fibroadenoma in axillary supernumerary breast in a 17-year-old girl: case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:E79-E81. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.04.008

- De la Torre M, Lorca-García C, de Tomás E, et al. Axillary ectopic breast tissue in the adolescent. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;38:1445-1451. doi:10.1007/s00383-022-05184-1

The Diagnosis: Accessory Breast

A diagnosis of accessory breast was confirmed on histopathology, which demonstrated a slightly hyperplastic and hyperpigmented epidermis. The dermis contained an increased number of smooth muscle bundles with the presence of apocrine glands and mammary lobules (Figure). Tenderness of the mass fluctuated according to the patient’s menstrual cycle, which supported a diagnosis of accessory breast over lipoma. The patient had no signs of infection or other systemic symptoms that were suggestive of lymphadenopathy. Unlike an epidermoid inclusion cyst, our patient’s mass presented as poorly defined and boggy in texture. Biopsy results were not consistent with malignancy, ruling out soft tissue sarcoma.

B, Myoepithelial cells lined a stratified columnar epithelium, characteristic of breast tissue (H&E, original magnification x40).

Accessory breasts are characterized by the presence of breast tissue outside the breast and can be found anywhere along the milk line from the axillae to the vulva.1 The prevalence of accessory breasts is 2% to 6% of women, with an average age of presentation for treatment of 42 years.2 Ninety percent of accessory breasts are found in the thorax, 5% are found in the abdomen, and 5% are found in the axillae.3 Incidence is uncommon in adolescents; however, in addition to our patient, there are several cases in the literature of adolescents with accessory breasts in the axillae.4,5

Ectopic mammary tissue is divided into 8 classes based on the Kajava classification system (Table). In a retrospective study of adolescent females with accessory breasts, 91% (10/11) of patients were classified as class IV, and 1 was class II.6 Similarly, our patient was classified as class IV since her accessory breast was composed entirely of glandular tissue and did not include an areola and nipple.

Supernumerary breast structures such as areolas and nipples typically are diagnosed at birth, whereas supernumerary breast tissue is not diagnosed until after hormonal stimulation typically seen during puberty, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Common symptoms include cyclic pain with menstruation, fluctuation in the size of the mass, and tenderness of the ectopic tissue. There also can be restricted range of motion and increased irritation from clothing. Ultrasonography generally shows a hypoechoic septate indicative of mammary tissue.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by histopathologic studies that show mammary lobules in the dermis with smooth muscle, mammary ducts connected to the nipple, and connective stroma.6

If bothersome, ectopic breast tissue can be surgically removed, either by direct excision or suction lipectomy depending on the size of the mass.2 Postoperative complications are low but can include seroma, bleeding, infection, remnant tissue, or undesired cosmetic results. As with normal breast tissue, ectopic breast tissue can manifest with benign and malignant pathologies.

In conclusion, accessory breast is a benign condition that can cause cyclical pain with menstruation, restricted range of motion, discomfort, anxiety, and cosmetic problems. It is important to keep this diagnosis on the differential when evaluating a soft tissue mass that appears in the axillary region.

The Diagnosis: Accessory Breast

A diagnosis of accessory breast was confirmed on histopathology, which demonstrated a slightly hyperplastic and hyperpigmented epidermis. The dermis contained an increased number of smooth muscle bundles with the presence of apocrine glands and mammary lobules (Figure). Tenderness of the mass fluctuated according to the patient’s menstrual cycle, which supported a diagnosis of accessory breast over lipoma. The patient had no signs of infection or other systemic symptoms that were suggestive of lymphadenopathy. Unlike an epidermoid inclusion cyst, our patient’s mass presented as poorly defined and boggy in texture. Biopsy results were not consistent with malignancy, ruling out soft tissue sarcoma.

B, Myoepithelial cells lined a stratified columnar epithelium, characteristic of breast tissue (H&E, original magnification x40).

Accessory breasts are characterized by the presence of breast tissue outside the breast and can be found anywhere along the milk line from the axillae to the vulva.1 The prevalence of accessory breasts is 2% to 6% of women, with an average age of presentation for treatment of 42 years.2 Ninety percent of accessory breasts are found in the thorax, 5% are found in the abdomen, and 5% are found in the axillae.3 Incidence is uncommon in adolescents; however, in addition to our patient, there are several cases in the literature of adolescents with accessory breasts in the axillae.4,5

Ectopic mammary tissue is divided into 8 classes based on the Kajava classification system (Table). In a retrospective study of adolescent females with accessory breasts, 91% (10/11) of patients were classified as class IV, and 1 was class II.6 Similarly, our patient was classified as class IV since her accessory breast was composed entirely of glandular tissue and did not include an areola and nipple.

Supernumerary breast structures such as areolas and nipples typically are diagnosed at birth, whereas supernumerary breast tissue is not diagnosed until after hormonal stimulation typically seen during puberty, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Common symptoms include cyclic pain with menstruation, fluctuation in the size of the mass, and tenderness of the ectopic tissue. There also can be restricted range of motion and increased irritation from clothing. Ultrasonography generally shows a hypoechoic septate indicative of mammary tissue.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by histopathologic studies that show mammary lobules in the dermis with smooth muscle, mammary ducts connected to the nipple, and connective stroma.6

If bothersome, ectopic breast tissue can be surgically removed, either by direct excision or suction lipectomy depending on the size of the mass.2 Postoperative complications are low but can include seroma, bleeding, infection, remnant tissue, or undesired cosmetic results. As with normal breast tissue, ectopic breast tissue can manifest with benign and malignant pathologies.

In conclusion, accessory breast is a benign condition that can cause cyclical pain with menstruation, restricted range of motion, discomfort, anxiety, and cosmetic problems. It is important to keep this diagnosis on the differential when evaluating a soft tissue mass that appears in the axillary region.

- Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical and current perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73:525-528.

- Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla: classification and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:35E-36E. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182173f95

- Mazine K, Bouassria A, Elbouhaddouti H. Bilateral supernumerary axillary breasts: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:282. doi:10.11604 /pamj.2020.36.282.20445

- Patel RV, Govani D, Patel R, et al. Adolescent right axillary accessory breast with galactorrhoea. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204215. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204215

- Surd A, Mironescu A, Gocan H. Fibroadenoma in axillary supernumerary breast in a 17-year-old girl: case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:E79-E81. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.04.008

- De la Torre M, Lorca-García C, de Tomás E, et al. Axillary ectopic breast tissue in the adolescent. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;38:1445-1451. doi:10.1007/s00383-022-05184-1

- Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical and current perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73:525-528.

- Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla: classification and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:35E-36E. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182173f95

- Mazine K, Bouassria A, Elbouhaddouti H. Bilateral supernumerary axillary breasts: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:282. doi:10.11604 /pamj.2020.36.282.20445

- Patel RV, Govani D, Patel R, et al. Adolescent right axillary accessory breast with galactorrhoea. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204215. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204215

- Surd A, Mironescu A, Gocan H. Fibroadenoma in axillary supernumerary breast in a 17-year-old girl: case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:E79-E81. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.04.008

- De la Torre M, Lorca-García C, de Tomás E, et al. Axillary ectopic breast tissue in the adolescent. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;38:1445-1451. doi:10.1007/s00383-022-05184-1

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

A 15-year-old adolescent female with an unremarkable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a mass in the left axilla of 2 years’ duration. The patient reported that there was no drainage of the lesion nor did she have any other similar lesions. She reported tenderness of the lesion during menstruation that resolved after this phase ended. Dermatologic examination revealed a solitary 4.4-cm, flesh-colored, poorly defined, boggy, fluctuant subcutaneous nodule with no central punctum or surface changes. Ultrasonography of the axilla showed a 6.4-cm hypoechoic heterogenous mass. A biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Longitudinal Depression on the Right Thumbnail

THE DIAGNOSIS: Habit-Tic Deformity

Habit-tic deformity is a cause of nail dystrophy that commonly arises in children and adults due to subconscious repetitive and self-injurious manipulation of the nail bed or cuticle, which ultimately damages the nail matrix.1,2 It can be considered a variant of onychotillomania.1

Characteristic features of habit-tic deformity include a longitudinal depression on the central nail plate with transverse ridges,1 which can be more prominent on the dominant hand.3 Patients typically note a long duration of nail deformity, often without insight into its etiology.2 Diagnosis relies on careful assessment of the clinical presentation and the patient’s history to rule out other differential diagnoses. Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history, we excluded wart, squamous cell carcinoma, eczema, psoriasis, lichen planus, autoimmune connective tissue disease, onychomycosis, paronychia, pincer nail deformity, and Beau line as potential diagnoses. Biopsy also can be performed to exclude these diagnoses from the differential if the cause is unclear following clinical examination.

Treatment for habit-tic deformity involves identifying and addressing the underlying habit. Barrier methods such as bandages and cyanoacrylate adhesives that prevent further manipulation of the nail matrix are effective treatments for habit-tic deformity.2 A multidisciplinary approach with psychiatry may be optimal to identify underlying psychological comorbidities and break the habit through behavior interventions and medications.4 Nail dystrophy generally improves once the habit is disrupted; however, a younger age of onset may carry a worse prognosis.3 Patients should be counseled that the affected nail may never grow normally.

Our patient was advised to use fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to reduce inflammation of the proximal nail fold and to cover the thumbnail with a bandage to prevent picking. He also was counseled that the nail may show ongoing abnormal growth. Minimal improvement was noted after 6 months.

- Rieder EA, Tosti A. Onychotillomania: an underrecognized disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1245-1250.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016

- Ring DS. Inexpensive solution for habit-tic deformity. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1222-1223. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.287

- Horne MI, Utzig JB, Rieder EA, et al. Alopecia areata and habit tic deformities. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:323-325. doi:10.1159/000486540

- Sonthalia S, Sharma P, Kapoor J, et al. Habit tic deformity: need fora comprehensive approach. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:117-118.doi:10.1159/000489320 .05.036

THE DIAGNOSIS: Habit-Tic Deformity

Habit-tic deformity is a cause of nail dystrophy that commonly arises in children and adults due to subconscious repetitive and self-injurious manipulation of the nail bed or cuticle, which ultimately damages the nail matrix.1,2 It can be considered a variant of onychotillomania.1

Characteristic features of habit-tic deformity include a longitudinal depression on the central nail plate with transverse ridges,1 which can be more prominent on the dominant hand.3 Patients typically note a long duration of nail deformity, often without insight into its etiology.2 Diagnosis relies on careful assessment of the clinical presentation and the patient’s history to rule out other differential diagnoses. Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history, we excluded wart, squamous cell carcinoma, eczema, psoriasis, lichen planus, autoimmune connective tissue disease, onychomycosis, paronychia, pincer nail deformity, and Beau line as potential diagnoses. Biopsy also can be performed to exclude these diagnoses from the differential if the cause is unclear following clinical examination.

Treatment for habit-tic deformity involves identifying and addressing the underlying habit. Barrier methods such as bandages and cyanoacrylate adhesives that prevent further manipulation of the nail matrix are effective treatments for habit-tic deformity.2 A multidisciplinary approach with psychiatry may be optimal to identify underlying psychological comorbidities and break the habit through behavior interventions and medications.4 Nail dystrophy generally improves once the habit is disrupted; however, a younger age of onset may carry a worse prognosis.3 Patients should be counseled that the affected nail may never grow normally.

Our patient was advised to use fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to reduce inflammation of the proximal nail fold and to cover the thumbnail with a bandage to prevent picking. He also was counseled that the nail may show ongoing abnormal growth. Minimal improvement was noted after 6 months.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Habit-Tic Deformity

Habit-tic deformity is a cause of nail dystrophy that commonly arises in children and adults due to subconscious repetitive and self-injurious manipulation of the nail bed or cuticle, which ultimately damages the nail matrix.1,2 It can be considered a variant of onychotillomania.1

Characteristic features of habit-tic deformity include a longitudinal depression on the central nail plate with transverse ridges,1 which can be more prominent on the dominant hand.3 Patients typically note a long duration of nail deformity, often without insight into its etiology.2 Diagnosis relies on careful assessment of the clinical presentation and the patient’s history to rule out other differential diagnoses. Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history, we excluded wart, squamous cell carcinoma, eczema, psoriasis, lichen planus, autoimmune connective tissue disease, onychomycosis, paronychia, pincer nail deformity, and Beau line as potential diagnoses. Biopsy also can be performed to exclude these diagnoses from the differential if the cause is unclear following clinical examination.

Treatment for habit-tic deformity involves identifying and addressing the underlying habit. Barrier methods such as bandages and cyanoacrylate adhesives that prevent further manipulation of the nail matrix are effective treatments for habit-tic deformity.2 A multidisciplinary approach with psychiatry may be optimal to identify underlying psychological comorbidities and break the habit through behavior interventions and medications.4 Nail dystrophy generally improves once the habit is disrupted; however, a younger age of onset may carry a worse prognosis.3 Patients should be counseled that the affected nail may never grow normally.

Our patient was advised to use fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to reduce inflammation of the proximal nail fold and to cover the thumbnail with a bandage to prevent picking. He also was counseled that the nail may show ongoing abnormal growth. Minimal improvement was noted after 6 months.

- Rieder EA, Tosti A. Onychotillomania: an underrecognized disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1245-1250.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016

- Ring DS. Inexpensive solution for habit-tic deformity. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1222-1223. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.287

- Horne MI, Utzig JB, Rieder EA, et al. Alopecia areata and habit tic deformities. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:323-325. doi:10.1159/000486540

- Sonthalia S, Sharma P, Kapoor J, et al. Habit tic deformity: need fora comprehensive approach. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:117-118.doi:10.1159/000489320 .05.036

- Rieder EA, Tosti A. Onychotillomania: an underrecognized disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1245-1250.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016

- Ring DS. Inexpensive solution for habit-tic deformity. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1222-1223. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.287

- Horne MI, Utzig JB, Rieder EA, et al. Alopecia areata and habit tic deformities. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:323-325. doi:10.1159/000486540

- Sonthalia S, Sharma P, Kapoor J, et al. Habit tic deformity: need fora comprehensive approach. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:117-118.doi:10.1159/000489320 .05.036

A healthy 13-year-old boy presented to the dermatology department with dystrophy of the right thumbnail of 3 to 4 years’ duration. A 5-mm-wide, depressed median longitudinal groove with a fir tree pattern was noted on the central nail plate. The patient noted that the groove had been gradually deepening. There was erythema, edema, and lichenification of the proximal nailfold without vascular changes, and the lunula was enlarged. No hyperkeratosis, subungual debris, erythematous nail folds, or inward curvature of the lateral aspects of the nail were noted. The patient denied any pruritus, pain, discomfort, or bleeding; he also denied any recent illness or trauma to the nail. None of the other nails were affected, and no other lesions or rashes were observed elsewhere on the body. The patient was unsure if he picked at the nail but acknowledged that he may have done so subconsciously. He had no history of eczema, psoriasis, or autoimmune connective tissue disorders.

Hyperkeratotic Papules and Black Macules on the Hands

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Hemorrhagic Darier Disease

Darier disease (DD), also known as keratosis follicularis, is a rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene (ATP2A2). This gene encodes the enzyme sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2, which results in abnormal calcium signaling in keratinocytes and leads to dyskeratosis.1 Darier disease commonly manifests in the second decade of life with hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques, often accompanied by erosions and fissures that cause discomfort and pruritus. Darier disease also is associated with characteristic nail findings such as the classic candy cane nails and V-shaped nicking.

Acral hemorrhagic lesions are a rare manifestation of DD. Clinically, these lesions can manifest as hemorrhagic macules, papules, and/or vesicles, most commonly occurring following local trauma or retinoid use. Patients with these lesions are believed to have either specific mutations in the ATP2A2 gene that impair sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 function in the vascular endothelium or a mutation in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase protein itself, leading to dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis from within the cell, provoking oxidative stress and causing detrimental effects on blood vessels.2 Patients with this variant can present with all the features of classic DD concomitantly, with varying symptom severity or distinct clinical features during separate episodic flares, or as the sole manifestation. Other nonclassical lesions of DD include acral keratoderma, giant comedones, keloidlike vegetations, and leucodermic macules (Figure).3

Acral hemorrhagic DD may appear either in isolation or in tandem with more traditional symptoms, necessitating consideration of other possible differential diagnoses such as acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf (AKV), porphyria cutanea tarda, bullous lichen planus (BLP), and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus.

Sometimes regarded as a variant of DD, AKV is an autosomal- dominant genodermatosis characterized by flat or verrucous hyperkeratotic papules on the hands and feet. In AKV, the nails also may be affected, with changes including striations, subungual hyperkeratosis, and V-shaped nicking of the distal nails. Although our patient displayed features of AKV, it has not been associated with acral hemorrhagic macules, making this diagnosis less likely than DD.4

Porphyria cutanea tarda, a condition caused by decreased levels of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, also can cause skin manifestations such as blistering as well as increased skin fragility, predominantly in sun-exposed areas.5 Our patient’s lack of photosensitivity and absence of other common symptoms of this disorder, such as hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation, made porphyria cutanea tarda less likely.

Bullous lichen planus is a rare subtype of lichen planus characterized by tense bullae arising from preexisting lichen planus lesions or appearing de novo, most commonly manifesting on the oral mucosa or the legs.6 The bullae associated with BLP can rupture and form ulcers—a symptom that could potentially be mistaken for hemorrhagic macules like the ones observed in our patient. However, BLP typically is characterized by erythematous, violaceous, polygonal papules commonly appearing on the oral mucosa and the legs with blisters developing near or on pre-existing lichen planus lesions. These are different from the hyperkeratotic papules and leucodermic macules seen in our patient, which aligned more closely with the clinical presentation of DD.

Hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus presents with white atrophic patches and plaques and hemorrhagic bullae, which may resemble the leucodermic macules and hemorrhagic macules of DD. However, hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus most commonly involves the genital area in postmenopausal women. Extragenital manifestations of lichen sclerosus, although less common, can occur and typically manifest on the thighs, buttocks, breasts, back, chest, axillae, shoulders, and wrists.7 Notably, these hemorrhagic lesions typically are surrounded by hypopigmented skin and display an atrophic appearance.

Management of DD can be challenging. General measures include sun protection, heat avoidance, and friction reduction. Retinoids are considered the first-line therapy for severe DD, as they help normalize keratinocyte differentiation and reduce keratotic scaling.8 Topical corticosteroids can help manage inflammation and reduce the risk for secondary infections. Our patient responded well to this treatment approach, with a notable reduction in the number and severity of the hyperkeratotic plaques and resolution of the acral hemorrhagic lesions.

- Savignac M, Edir A, Simon M, et al. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1111-1117. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.006

- Hong E, Hu R, Posligua A, et al. Acral hemorrhagic Darier disease: a case report of a rare presentation and literature review. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;31:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.030

- Yeshurun A, Ziv M, Cohen-Barak E, et al. An update on the cutaneous manifestations of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:498-503. doi:10.1177/1203475421999331

- Williams GM, Lincoln M. Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023.

- Shah A, Bhatt H. Cutanea tarda porphyria. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; April 17, 2023.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4. doi:10.3315/jdcr.2017.1239

- Arnold N, Manway M, Stephenson S, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus on the anterior lower extremities: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030

- Haber RN, Dib NG. Management of Darier disease: a review of the literature and update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:14-21. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_963_19 /qt8dn3p7kv.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Hemorrhagic Darier Disease

Darier disease (DD), also known as keratosis follicularis, is a rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene (ATP2A2). This gene encodes the enzyme sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2, which results in abnormal calcium signaling in keratinocytes and leads to dyskeratosis.1 Darier disease commonly manifests in the second decade of life with hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques, often accompanied by erosions and fissures that cause discomfort and pruritus. Darier disease also is associated with characteristic nail findings such as the classic candy cane nails and V-shaped nicking.

Acral hemorrhagic lesions are a rare manifestation of DD. Clinically, these lesions can manifest as hemorrhagic macules, papules, and/or vesicles, most commonly occurring following local trauma or retinoid use. Patients with these lesions are believed to have either specific mutations in the ATP2A2 gene that impair sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 function in the vascular endothelium or a mutation in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase protein itself, leading to dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis from within the cell, provoking oxidative stress and causing detrimental effects on blood vessels.2 Patients with this variant can present with all the features of classic DD concomitantly, with varying symptom severity or distinct clinical features during separate episodic flares, or as the sole manifestation. Other nonclassical lesions of DD include acral keratoderma, giant comedones, keloidlike vegetations, and leucodermic macules (Figure).3

Acral hemorrhagic DD may appear either in isolation or in tandem with more traditional symptoms, necessitating consideration of other possible differential diagnoses such as acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf (AKV), porphyria cutanea tarda, bullous lichen planus (BLP), and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus.

Sometimes regarded as a variant of DD, AKV is an autosomal- dominant genodermatosis characterized by flat or verrucous hyperkeratotic papules on the hands and feet. In AKV, the nails also may be affected, with changes including striations, subungual hyperkeratosis, and V-shaped nicking of the distal nails. Although our patient displayed features of AKV, it has not been associated with acral hemorrhagic macules, making this diagnosis less likely than DD.4

Porphyria cutanea tarda, a condition caused by decreased levels of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, also can cause skin manifestations such as blistering as well as increased skin fragility, predominantly in sun-exposed areas.5 Our patient’s lack of photosensitivity and absence of other common symptoms of this disorder, such as hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation, made porphyria cutanea tarda less likely.

Bullous lichen planus is a rare subtype of lichen planus characterized by tense bullae arising from preexisting lichen planus lesions or appearing de novo, most commonly manifesting on the oral mucosa or the legs.6 The bullae associated with BLP can rupture and form ulcers—a symptom that could potentially be mistaken for hemorrhagic macules like the ones observed in our patient. However, BLP typically is characterized by erythematous, violaceous, polygonal papules commonly appearing on the oral mucosa and the legs with blisters developing near or on pre-existing lichen planus lesions. These are different from the hyperkeratotic papules and leucodermic macules seen in our patient, which aligned more closely with the clinical presentation of DD.

Hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus presents with white atrophic patches and plaques and hemorrhagic bullae, which may resemble the leucodermic macules and hemorrhagic macules of DD. However, hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus most commonly involves the genital area in postmenopausal women. Extragenital manifestations of lichen sclerosus, although less common, can occur and typically manifest on the thighs, buttocks, breasts, back, chest, axillae, shoulders, and wrists.7 Notably, these hemorrhagic lesions typically are surrounded by hypopigmented skin and display an atrophic appearance.

Management of DD can be challenging. General measures include sun protection, heat avoidance, and friction reduction. Retinoids are considered the first-line therapy for severe DD, as they help normalize keratinocyte differentiation and reduce keratotic scaling.8 Topical corticosteroids can help manage inflammation and reduce the risk for secondary infections. Our patient responded well to this treatment approach, with a notable reduction in the number and severity of the hyperkeratotic plaques and resolution of the acral hemorrhagic lesions.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Hemorrhagic Darier Disease

Darier disease (DD), also known as keratosis follicularis, is a rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene (ATP2A2). This gene encodes the enzyme sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2, which results in abnormal calcium signaling in keratinocytes and leads to dyskeratosis.1 Darier disease commonly manifests in the second decade of life with hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques, often accompanied by erosions and fissures that cause discomfort and pruritus. Darier disease also is associated with characteristic nail findings such as the classic candy cane nails and V-shaped nicking.

Acral hemorrhagic lesions are a rare manifestation of DD. Clinically, these lesions can manifest as hemorrhagic macules, papules, and/or vesicles, most commonly occurring following local trauma or retinoid use. Patients with these lesions are believed to have either specific mutations in the ATP2A2 gene that impair sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 function in the vascular endothelium or a mutation in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase protein itself, leading to dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis from within the cell, provoking oxidative stress and causing detrimental effects on blood vessels.2 Patients with this variant can present with all the features of classic DD concomitantly, with varying symptom severity or distinct clinical features during separate episodic flares, or as the sole manifestation. Other nonclassical lesions of DD include acral keratoderma, giant comedones, keloidlike vegetations, and leucodermic macules (Figure).3

Acral hemorrhagic DD may appear either in isolation or in tandem with more traditional symptoms, necessitating consideration of other possible differential diagnoses such as acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf (AKV), porphyria cutanea tarda, bullous lichen planus (BLP), and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus.

Sometimes regarded as a variant of DD, AKV is an autosomal- dominant genodermatosis characterized by flat or verrucous hyperkeratotic papules on the hands and feet. In AKV, the nails also may be affected, with changes including striations, subungual hyperkeratosis, and V-shaped nicking of the distal nails. Although our patient displayed features of AKV, it has not been associated with acral hemorrhagic macules, making this diagnosis less likely than DD.4

Porphyria cutanea tarda, a condition caused by decreased levels of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, also can cause skin manifestations such as blistering as well as increased skin fragility, predominantly in sun-exposed areas.5 Our patient’s lack of photosensitivity and absence of other common symptoms of this disorder, such as hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation, made porphyria cutanea tarda less likely.

Bullous lichen planus is a rare subtype of lichen planus characterized by tense bullae arising from preexisting lichen planus lesions or appearing de novo, most commonly manifesting on the oral mucosa or the legs.6 The bullae associated with BLP can rupture and form ulcers—a symptom that could potentially be mistaken for hemorrhagic macules like the ones observed in our patient. However, BLP typically is characterized by erythematous, violaceous, polygonal papules commonly appearing on the oral mucosa and the legs with blisters developing near or on pre-existing lichen planus lesions. These are different from the hyperkeratotic papules and leucodermic macules seen in our patient, which aligned more closely with the clinical presentation of DD.

Hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus presents with white atrophic patches and plaques and hemorrhagic bullae, which may resemble the leucodermic macules and hemorrhagic macules of DD. However, hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus most commonly involves the genital area in postmenopausal women. Extragenital manifestations of lichen sclerosus, although less common, can occur and typically manifest on the thighs, buttocks, breasts, back, chest, axillae, shoulders, and wrists.7 Notably, these hemorrhagic lesions typically are surrounded by hypopigmented skin and display an atrophic appearance.

Management of DD can be challenging. General measures include sun protection, heat avoidance, and friction reduction. Retinoids are considered the first-line therapy for severe DD, as they help normalize keratinocyte differentiation and reduce keratotic scaling.8 Topical corticosteroids can help manage inflammation and reduce the risk for secondary infections. Our patient responded well to this treatment approach, with a notable reduction in the number and severity of the hyperkeratotic plaques and resolution of the acral hemorrhagic lesions.

- Savignac M, Edir A, Simon M, et al. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1111-1117. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.006

- Hong E, Hu R, Posligua A, et al. Acral hemorrhagic Darier disease: a case report of a rare presentation and literature review. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;31:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.030

- Yeshurun A, Ziv M, Cohen-Barak E, et al. An update on the cutaneous manifestations of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:498-503. doi:10.1177/1203475421999331

- Williams GM, Lincoln M. Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023.

- Shah A, Bhatt H. Cutanea tarda porphyria. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; April 17, 2023.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4. doi:10.3315/jdcr.2017.1239

- Arnold N, Manway M, Stephenson S, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus on the anterior lower extremities: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030

- Haber RN, Dib NG. Management of Darier disease: a review of the literature and update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:14-21. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_963_19 /qt8dn3p7kv.

- Savignac M, Edir A, Simon M, et al. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1111-1117. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.006

- Hong E, Hu R, Posligua A, et al. Acral hemorrhagic Darier disease: a case report of a rare presentation and literature review. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;31:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.030

- Yeshurun A, Ziv M, Cohen-Barak E, et al. An update on the cutaneous manifestations of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:498-503. doi:10.1177/1203475421999331

- Williams GM, Lincoln M. Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023.

- Shah A, Bhatt H. Cutanea tarda porphyria. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; April 17, 2023.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4. doi:10.3315/jdcr.2017.1239

- Arnold N, Manway M, Stephenson S, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus on the anterior lower extremities: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030

- Haber RN, Dib NG. Management of Darier disease: a review of the literature and update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:14-21. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_963_19 /qt8dn3p7kv.

An elderly woman with a long history of hyperkeratotic papules on the abdomen, forearms, dorsal hands, and skinfolds presented with new lesions on the dorsal hands that had developed over the preceding few months after a lapse in treatment with her previous dermatologist. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Physical examination revealed hyperkeratotic papules, black hemorrhagic macules with jagged borders, and a thin hemorrhagic plaque on the dorsal hands. Nail findings were notable for alternating white and red longitudinal bands with nicking of the distal nail plates. She also had scattered leucodermic macules over the trunk, feet, arms, and legs, as well as numerous hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques over the mons pubis and in the inguinal folds.

Eruption of Multiple Linear Hyperpigmented Plaques

THE DIAGNOSIS: Chemotherapy-Induced Flagellate Dermatitis

Based on the clinical presentation and temporal relation with chemotherapy, a diagnosis of bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis (FD) was made, as bleomycin is the only chemotherapeutic agent from this regimen that has been linked with FD.1,2 Laboratory findings revealed eosinophilia, further supporting a druginduced dermatitis. The patient was treated with oral steroids and diphenhydramine to alleviate itching and discomfort. The chemotherapy was temporarily discontinued until symptomatic improvement was observed within 2 to 3 days.

Flagellate dermatitis is characterized by unique erythematous, linear, intermingled streaks of adjoining firm papules—often preceded by a prodrome of global pruritus—that eventually become hyperpigmented as the erythema subsides. The clinical manifestation of FD can be idiopathic; true/mechanical (dermatitis artefacta, abuse, sadomasochism); chemotherapy induced (peplomycin, trastuzumab, cisplatin, docetaxel, bendamustine); toxin induced (shiitake mushroom, cnidarian stings, Paederus insects); related to rheumatologic diseases (dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease), dermatographism, phytophotodermatitis, or poison ivy dermatitis; or induced by chikungunya fever.1

The term flagellate originates from the Latin word flagellum, which pertains to the distinctive whiplike pattern. It was first described by Moulin et al3 in 1970 in reference to bleomycin-induced linear hyperpigmentation. Bleomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic derived from Streptomyces verticillus, is used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and germ cell tumors. The worldwide incidence of bleomycin-induced FD is 8% to 22% and commonly is associated with a cumulative dose greater than 100 U.2 Clinical presentation is variable in terms of onset, distribution, and morphology of the eruption and could be independent of dose, route of administration, or type of malignancy being treated. The flagellate rash commonly involves the trunk, arms, and legs; can develop within hours to 6 months of starting bleomycin therapy; often is preceded by generalized itching; and eventually heals with hyperpigmentation.

Possible mechanisms of bleomycin-induced FD include localized melanogenesis, inflammatory pigmentary incontinence, alterations to normal pigmentation patterns, cytotoxic effects of the drug itself, minor trauma/ scratching leading to increased blood flow and causing local accumulation of bleomycin, heat recall, and reduced epidermal turnover leading to extended interaction between keratinocytes and melanocytes.2 Heat exposure can act as a trigger for bleomycin-induced skin rash recall even months after the treatment is stopped.