User login

Navigating the Search for a Financial Adviser

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

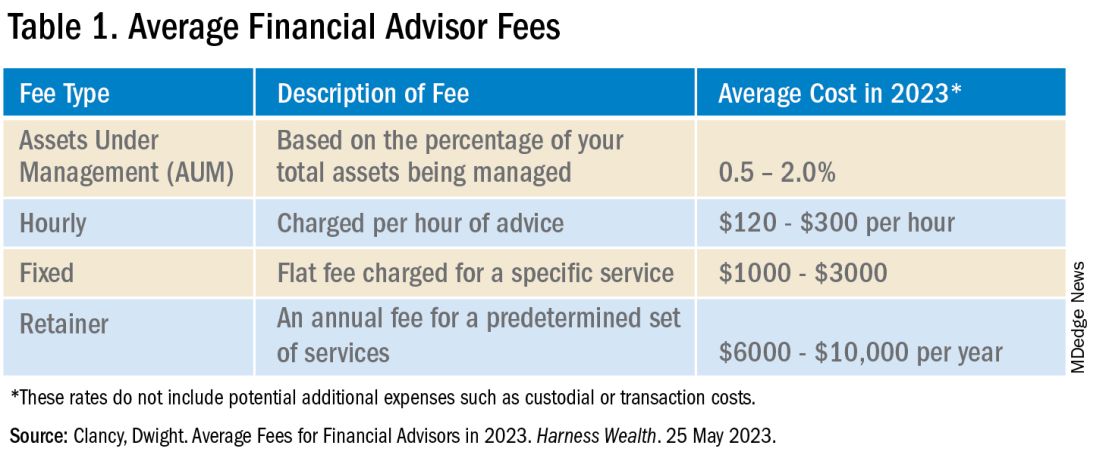

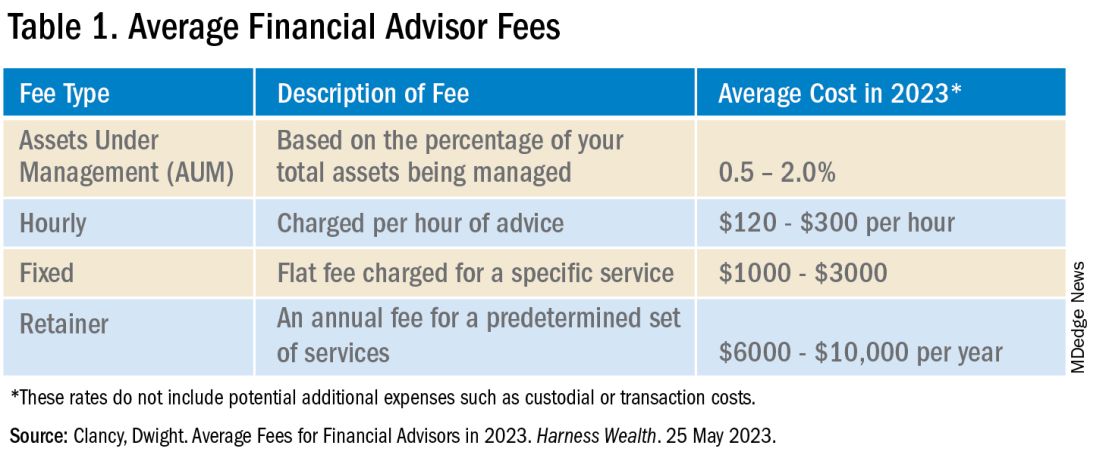

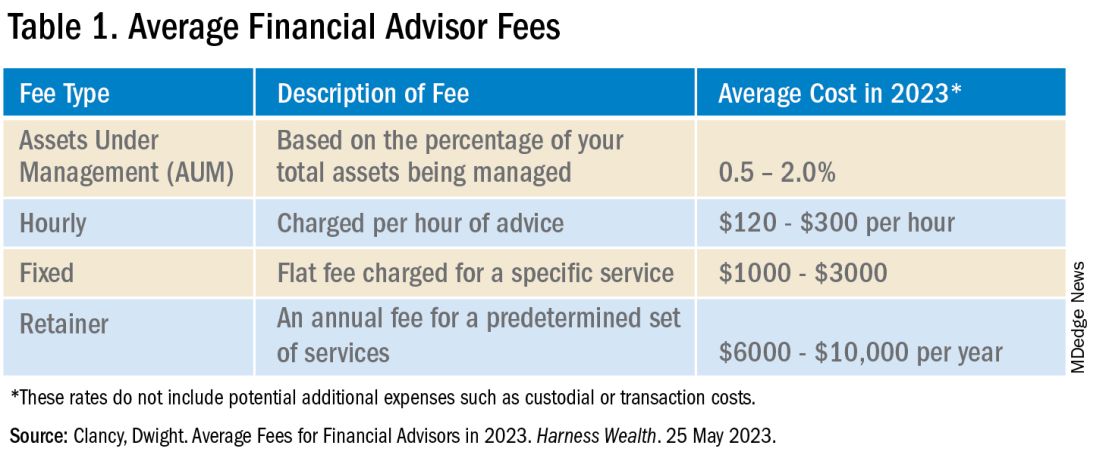

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

Achieving Promotion for Junior Faculty in Academic Medicine: An Interview With Experts

Academic medicine plays a crucial role at the crossroads of medical practice, education, and research, influencing the future landscape of healthcare. Many physicians aspire to pursue and sustain a career in academic medicine to contribute to the advancement of medical knowledge, enhance patient care, and influence the trajectory of the medical field. Opting for a career in academic medicine can offer benefits such as increased autonomy and scheduling flexibility, which can significantly improve the quality of life. In addition, engagement in scholarly activities and working in a dynamic environment with continuous learning opportunities can help mitigate burnout.

However, embarking on an academic career can be daunting for junior faculty members who face the challenge of providing clinical care while excelling in research and dedicating time to mentorship and teaching trainees. According to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 38% of physicians leave academic medicine within a decade of obtaining a faculty position. Barriers to promotion and retention within academic medicine include ineffective mentorship, unclear or inconsistent promotion criteria, and disparities in gender/ethnic representation.

In this article, we interview two accomplished physicians in academic medicine who have attained the rank of professors.

Interview with Sophie Balzora, MD

Dr. Balzora is a professor of medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and a practicing gastroenterologist specializing in the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease at NYU Langone Health. She serves as the American College of Gastroenterology’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee Chair, on the Advisory Board of ACG’s Leadership, Ethics, and Equity (LE&E) Center, and is president and cofounder of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists (ABGH). Dr. Balzora was promoted to full professor 11 years after graduating from fellowship.

What would you identify as some of the most important factors that led to your success in achieving a promotion to professor of medicine?

Surround yourself with individuals whose professional and personal priorities align with yours. To achieve this, it is essential to gain an understanding of what is important to you, what you envision your success to look like, and establish a timeline to achieve it. The concept of personal success and how to best achieve it will absolutely change as you grow, and that is okay and expected. Connecting with those outside of your clinical interests, at other institutions, and even outside of the medical field, can help you achieve these goals and better shape how you see your career unfolding and how you want it to look.

Historically, the proportion of physicians who achieve professorship is lower among women compared with men. What do you believe are some of the barriers involved in this, and how would you counsel women who are interested in pursuing the rank of professor?

Systemic gender bias and discrimination, over-mentorship and under-sponsorship, inconsistent parental leave, and delayed parenthood are a few of the factors that contribute to the observed disparities in academic rank. Predictably, for women from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine, the chasm grows.

What has helped me most is to keep my eyes on the prize, and to recognize that the prize is different for everyone. It’s important not to make direct comparisons to any other individual, because they are not you. Harness what makes you different and drown out the naysayers — the “we’ve never seen this done before” camp, the “it’s too soon [for someone like you] to go up for promotion” folks. While these voices are sometimes well intentioned, they can distract you from your goals and ambitions because they are rooted in bias and adherence to traditional expectations. To do something new, and to change the game, requires going against the grain and utilizing your skills and talents to achieve what you want to achieve in a way that works for you.

What are some practical tips you have for junior gastroenterologists to track their promotion in academia?

- Keep your curriculum vitae (CV) up to date and formatted to your institutional guidelines. Ensure that you document your academic activities, even if it doesn’t seem important in the moment. When it’s time to submit that promotion portfolio, you want to be ready and organized.

- Remember: “No” is a full sentence, and saying it takes practice and time and confidence. It is a skill I still struggle to adopt at times, but it’s important to recognize the power of no, for it opens opportunities to say yes to other things.

- Lift as you climb — a critical part of changing the status quo is fostering the future of those underrepresented in medicine. A professional goal of mine that keeps me steady and passionate is to create supporting and enriching systemic and institutional changes that work to dismantle the obstacles perpetuating disparities in academic rank for women and those underrepresented in medicine. Discovering your “why” is a complex, difficult, and rewarding journey.

Interview with Mark Schattner, MD, AGAF

Dr. Schattner is a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell College of Medicine and chief of the gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. He is a former president of the New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and a fellow of the AGA and ASGE.

In your role as chief, you serve as a mentor for early career gastroenterologists for pursuing career promotion. What advice do you have for achieving this?

Promoting junior faculty is one of the prime responsibilities of a service chief. Generally, the early steps of promotion are straightforward, with criteria becoming more stringent as you progress. I think it is critical to understand the criteria used by promotion committees and to be aware of the various available tracks. I believe every meeting a junior faculty member has with their service chief should include, at the least, a brief check-in on where they are in the promotion process and plans (both short term and long term) to move forward. Successful promotion is facilitated when done upon a solid foundation of production and accomplishment. It is very challenging or even impossible when trying to piece together a package from discordant activities.

Most institutions require or encourage academic involvement at both national and international levels for career promotion. Do you have advice for junior faculty about how to achieve this type of recognition or experience?

The easiest place to start is with regional professional societies. Active involvement in these local societies fosters valuable networking and lays the groundwork for involvement at the national or international level. I would strongly encourage junior faculty to seek opportunities for a leadership position at any level in these societies and move up the ladder as their career matures. This is also a very good avenue to network and get invited to join collaborative research projects, which can be a fruitful means to enhance your academic productivity.

In your opinion, what factors are likely to hinder or delay an individual’s promotion?

I think it is crucial to consider the career track you are on. If you are very clinically productive and love to teach, that is completely appropriate, and most institutions will recognize the value of that and promote you along a clinical-educator tract. On the other hand, if you have a passion for research and can successfully lead research and compete for grants, then you would move along a traditional tenure track. It is also critical to think ahead, know the criteria on which you will be judged, and incorporate that into your practice early. Trying to scramble to enhance your CV in a short time just for promotion will likely prove ineffective.

Do you have advice for junior faculty who have families about how to manage career goals but also prioritize time with family?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to this. I think this requires a lot of shared decision-making with your family. Compromise will undoubtedly be required. For example, I always chose to live in close proximity to my workplace, eliminating any commuting time. This choice really allowed me spend time with my family.

In conclusion, a career in academic medicine presents both opportunities and challenges. A successful academic career, and achieving promotion to the rank of professor of medicine, requires a combination of factors including understanding institution-specific criteria for promotion, proactive engagement at the regional and national level, and envisioning your career goals and creating a timeline to achieve them. There are challenges to promotion, including navigating systemic biases and balancing career goals with family commitments, which also requires consideration and open communication. Ultimately, we hope these insights provide valuable guidance and advice for junior faculty who are navigating this complex environment of academic medicine and are motivated toward achieving professional fulfillment and satisfaction in their careers.

Dr. Rolston is based in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. She reports no conflicts in relation this article. Dr. Balzora and Dr. Schattner are based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, New York University Langone Health, New York. Dr. Schattner is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Balzora reports no conflicts in relation to this article.

References

Campbell KM. Mitigating the isolation of minoritized faculty in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2023 May. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07982-8.

Howard-Anderson JR et al. Strategies for developing a successful career in academic medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2024 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2023.12.010.

Murphy M et al. Women’s experiences of promotion and tenure in academic medicine and potential implications for gender disparities in career advancement: A qualitative analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Sep 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25843.

Sambunjak D et al. Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006 Sep 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103.

Shen MR et al. Impact of mentoring on academic career success for women in medicine: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2022 Mar 1. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004563.

Academic medicine plays a crucial role at the crossroads of medical practice, education, and research, influencing the future landscape of healthcare. Many physicians aspire to pursue and sustain a career in academic medicine to contribute to the advancement of medical knowledge, enhance patient care, and influence the trajectory of the medical field. Opting for a career in academic medicine can offer benefits such as increased autonomy and scheduling flexibility, which can significantly improve the quality of life. In addition, engagement in scholarly activities and working in a dynamic environment with continuous learning opportunities can help mitigate burnout.

However, embarking on an academic career can be daunting for junior faculty members who face the challenge of providing clinical care while excelling in research and dedicating time to mentorship and teaching trainees. According to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 38% of physicians leave academic medicine within a decade of obtaining a faculty position. Barriers to promotion and retention within academic medicine include ineffective mentorship, unclear or inconsistent promotion criteria, and disparities in gender/ethnic representation.

In this article, we interview two accomplished physicians in academic medicine who have attained the rank of professors.

Interview with Sophie Balzora, MD

Dr. Balzora is a professor of medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and a practicing gastroenterologist specializing in the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease at NYU Langone Health. She serves as the American College of Gastroenterology’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee Chair, on the Advisory Board of ACG’s Leadership, Ethics, and Equity (LE&E) Center, and is president and cofounder of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists (ABGH). Dr. Balzora was promoted to full professor 11 years after graduating from fellowship.

What would you identify as some of the most important factors that led to your success in achieving a promotion to professor of medicine?

Surround yourself with individuals whose professional and personal priorities align with yours. To achieve this, it is essential to gain an understanding of what is important to you, what you envision your success to look like, and establish a timeline to achieve it. The concept of personal success and how to best achieve it will absolutely change as you grow, and that is okay and expected. Connecting with those outside of your clinical interests, at other institutions, and even outside of the medical field, can help you achieve these goals and better shape how you see your career unfolding and how you want it to look.

Historically, the proportion of physicians who achieve professorship is lower among women compared with men. What do you believe are some of the barriers involved in this, and how would you counsel women who are interested in pursuing the rank of professor?

Systemic gender bias and discrimination, over-mentorship and under-sponsorship, inconsistent parental leave, and delayed parenthood are a few of the factors that contribute to the observed disparities in academic rank. Predictably, for women from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine, the chasm grows.

What has helped me most is to keep my eyes on the prize, and to recognize that the prize is different for everyone. It’s important not to make direct comparisons to any other individual, because they are not you. Harness what makes you different and drown out the naysayers — the “we’ve never seen this done before” camp, the “it’s too soon [for someone like you] to go up for promotion” folks. While these voices are sometimes well intentioned, they can distract you from your goals and ambitions because they are rooted in bias and adherence to traditional expectations. To do something new, and to change the game, requires going against the grain and utilizing your skills and talents to achieve what you want to achieve in a way that works for you.

What are some practical tips you have for junior gastroenterologists to track their promotion in academia?

- Keep your curriculum vitae (CV) up to date and formatted to your institutional guidelines. Ensure that you document your academic activities, even if it doesn’t seem important in the moment. When it’s time to submit that promotion portfolio, you want to be ready and organized.

- Remember: “No” is a full sentence, and saying it takes practice and time and confidence. It is a skill I still struggle to adopt at times, but it’s important to recognize the power of no, for it opens opportunities to say yes to other things.

- Lift as you climb — a critical part of changing the status quo is fostering the future of those underrepresented in medicine. A professional goal of mine that keeps me steady and passionate is to create supporting and enriching systemic and institutional changes that work to dismantle the obstacles perpetuating disparities in academic rank for women and those underrepresented in medicine. Discovering your “why” is a complex, difficult, and rewarding journey.

Interview with Mark Schattner, MD, AGAF

Dr. Schattner is a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell College of Medicine and chief of the gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. He is a former president of the New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and a fellow of the AGA and ASGE.

In your role as chief, you serve as a mentor for early career gastroenterologists for pursuing career promotion. What advice do you have for achieving this?

Promoting junior faculty is one of the prime responsibilities of a service chief. Generally, the early steps of promotion are straightforward, with criteria becoming more stringent as you progress. I think it is critical to understand the criteria used by promotion committees and to be aware of the various available tracks. I believe every meeting a junior faculty member has with their service chief should include, at the least, a brief check-in on where they are in the promotion process and plans (both short term and long term) to move forward. Successful promotion is facilitated when done upon a solid foundation of production and accomplishment. It is very challenging or even impossible when trying to piece together a package from discordant activities.

Most institutions require or encourage academic involvement at both national and international levels for career promotion. Do you have advice for junior faculty about how to achieve this type of recognition or experience?

The easiest place to start is with regional professional societies. Active involvement in these local societies fosters valuable networking and lays the groundwork for involvement at the national or international level. I would strongly encourage junior faculty to seek opportunities for a leadership position at any level in these societies and move up the ladder as their career matures. This is also a very good avenue to network and get invited to join collaborative research projects, which can be a fruitful means to enhance your academic productivity.

In your opinion, what factors are likely to hinder or delay an individual’s promotion?

I think it is crucial to consider the career track you are on. If you are very clinically productive and love to teach, that is completely appropriate, and most institutions will recognize the value of that and promote you along a clinical-educator tract. On the other hand, if you have a passion for research and can successfully lead research and compete for grants, then you would move along a traditional tenure track. It is also critical to think ahead, know the criteria on which you will be judged, and incorporate that into your practice early. Trying to scramble to enhance your CV in a short time just for promotion will likely prove ineffective.

Do you have advice for junior faculty who have families about how to manage career goals but also prioritize time with family?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to this. I think this requires a lot of shared decision-making with your family. Compromise will undoubtedly be required. For example, I always chose to live in close proximity to my workplace, eliminating any commuting time. This choice really allowed me spend time with my family.

In conclusion, a career in academic medicine presents both opportunities and challenges. A successful academic career, and achieving promotion to the rank of professor of medicine, requires a combination of factors including understanding institution-specific criteria for promotion, proactive engagement at the regional and national level, and envisioning your career goals and creating a timeline to achieve them. There are challenges to promotion, including navigating systemic biases and balancing career goals with family commitments, which also requires consideration and open communication. Ultimately, we hope these insights provide valuable guidance and advice for junior faculty who are navigating this complex environment of academic medicine and are motivated toward achieving professional fulfillment and satisfaction in their careers.

Dr. Rolston is based in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. She reports no conflicts in relation this article. Dr. Balzora and Dr. Schattner are based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, New York University Langone Health, New York. Dr. Schattner is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Balzora reports no conflicts in relation to this article.

References

Campbell KM. Mitigating the isolation of minoritized faculty in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2023 May. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07982-8.

Howard-Anderson JR et al. Strategies for developing a successful career in academic medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2024 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2023.12.010.

Murphy M et al. Women’s experiences of promotion and tenure in academic medicine and potential implications for gender disparities in career advancement: A qualitative analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Sep 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25843.

Sambunjak D et al. Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006 Sep 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103.

Shen MR et al. Impact of mentoring on academic career success for women in medicine: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2022 Mar 1. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004563.

Academic medicine plays a crucial role at the crossroads of medical practice, education, and research, influencing the future landscape of healthcare. Many physicians aspire to pursue and sustain a career in academic medicine to contribute to the advancement of medical knowledge, enhance patient care, and influence the trajectory of the medical field. Opting for a career in academic medicine can offer benefits such as increased autonomy and scheduling flexibility, which can significantly improve the quality of life. In addition, engagement in scholarly activities and working in a dynamic environment with continuous learning opportunities can help mitigate burnout.

However, embarking on an academic career can be daunting for junior faculty members who face the challenge of providing clinical care while excelling in research and dedicating time to mentorship and teaching trainees. According to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 38% of physicians leave academic medicine within a decade of obtaining a faculty position. Barriers to promotion and retention within academic medicine include ineffective mentorship, unclear or inconsistent promotion criteria, and disparities in gender/ethnic representation.

In this article, we interview two accomplished physicians in academic medicine who have attained the rank of professors.

Interview with Sophie Balzora, MD

Dr. Balzora is a professor of medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and a practicing gastroenterologist specializing in the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease at NYU Langone Health. She serves as the American College of Gastroenterology’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee Chair, on the Advisory Board of ACG’s Leadership, Ethics, and Equity (LE&E) Center, and is president and cofounder of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists (ABGH). Dr. Balzora was promoted to full professor 11 years after graduating from fellowship.

What would you identify as some of the most important factors that led to your success in achieving a promotion to professor of medicine?

Surround yourself with individuals whose professional and personal priorities align with yours. To achieve this, it is essential to gain an understanding of what is important to you, what you envision your success to look like, and establish a timeline to achieve it. The concept of personal success and how to best achieve it will absolutely change as you grow, and that is okay and expected. Connecting with those outside of your clinical interests, at other institutions, and even outside of the medical field, can help you achieve these goals and better shape how you see your career unfolding and how you want it to look.

Historically, the proportion of physicians who achieve professorship is lower among women compared with men. What do you believe are some of the barriers involved in this, and how would you counsel women who are interested in pursuing the rank of professor?

Systemic gender bias and discrimination, over-mentorship and under-sponsorship, inconsistent parental leave, and delayed parenthood are a few of the factors that contribute to the observed disparities in academic rank. Predictably, for women from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine, the chasm grows.

What has helped me most is to keep my eyes on the prize, and to recognize that the prize is different for everyone. It’s important not to make direct comparisons to any other individual, because they are not you. Harness what makes you different and drown out the naysayers — the “we’ve never seen this done before” camp, the “it’s too soon [for someone like you] to go up for promotion” folks. While these voices are sometimes well intentioned, they can distract you from your goals and ambitions because they are rooted in bias and adherence to traditional expectations. To do something new, and to change the game, requires going against the grain and utilizing your skills and talents to achieve what you want to achieve in a way that works for you.

What are some practical tips you have for junior gastroenterologists to track their promotion in academia?

- Keep your curriculum vitae (CV) up to date and formatted to your institutional guidelines. Ensure that you document your academic activities, even if it doesn’t seem important in the moment. When it’s time to submit that promotion portfolio, you want to be ready and organized.

- Remember: “No” is a full sentence, and saying it takes practice and time and confidence. It is a skill I still struggle to adopt at times, but it’s important to recognize the power of no, for it opens opportunities to say yes to other things.

- Lift as you climb — a critical part of changing the status quo is fostering the future of those underrepresented in medicine. A professional goal of mine that keeps me steady and passionate is to create supporting and enriching systemic and institutional changes that work to dismantle the obstacles perpetuating disparities in academic rank for women and those underrepresented in medicine. Discovering your “why” is a complex, difficult, and rewarding journey.

Interview with Mark Schattner, MD, AGAF

Dr. Schattner is a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell College of Medicine and chief of the gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. He is a former president of the New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and a fellow of the AGA and ASGE.

In your role as chief, you serve as a mentor for early career gastroenterologists for pursuing career promotion. What advice do you have for achieving this?

Promoting junior faculty is one of the prime responsibilities of a service chief. Generally, the early steps of promotion are straightforward, with criteria becoming more stringent as you progress. I think it is critical to understand the criteria used by promotion committees and to be aware of the various available tracks. I believe every meeting a junior faculty member has with their service chief should include, at the least, a brief check-in on where they are in the promotion process and plans (both short term and long term) to move forward. Successful promotion is facilitated when done upon a solid foundation of production and accomplishment. It is very challenging or even impossible when trying to piece together a package from discordant activities.

Most institutions require or encourage academic involvement at both national and international levels for career promotion. Do you have advice for junior faculty about how to achieve this type of recognition or experience?

The easiest place to start is with regional professional societies. Active involvement in these local societies fosters valuable networking and lays the groundwork for involvement at the national or international level. I would strongly encourage junior faculty to seek opportunities for a leadership position at any level in these societies and move up the ladder as their career matures. This is also a very good avenue to network and get invited to join collaborative research projects, which can be a fruitful means to enhance your academic productivity.

In your opinion, what factors are likely to hinder or delay an individual’s promotion?

I think it is crucial to consider the career track you are on. If you are very clinically productive and love to teach, that is completely appropriate, and most institutions will recognize the value of that and promote you along a clinical-educator tract. On the other hand, if you have a passion for research and can successfully lead research and compete for grants, then you would move along a traditional tenure track. It is also critical to think ahead, know the criteria on which you will be judged, and incorporate that into your practice early. Trying to scramble to enhance your CV in a short time just for promotion will likely prove ineffective.

Do you have advice for junior faculty who have families about how to manage career goals but also prioritize time with family?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to this. I think this requires a lot of shared decision-making with your family. Compromise will undoubtedly be required. For example, I always chose to live in close proximity to my workplace, eliminating any commuting time. This choice really allowed me spend time with my family.

In conclusion, a career in academic medicine presents both opportunities and challenges. A successful academic career, and achieving promotion to the rank of professor of medicine, requires a combination of factors including understanding institution-specific criteria for promotion, proactive engagement at the regional and national level, and envisioning your career goals and creating a timeline to achieve them. There are challenges to promotion, including navigating systemic biases and balancing career goals with family commitments, which also requires consideration and open communication. Ultimately, we hope these insights provide valuable guidance and advice for junior faculty who are navigating this complex environment of academic medicine and are motivated toward achieving professional fulfillment and satisfaction in their careers.

Dr. Rolston is based in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. She reports no conflicts in relation this article. Dr. Balzora and Dr. Schattner are based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, New York University Langone Health, New York. Dr. Schattner is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Balzora reports no conflicts in relation to this article.

References

Campbell KM. Mitigating the isolation of minoritized faculty in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2023 May. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07982-8.

Howard-Anderson JR et al. Strategies for developing a successful career in academic medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2024 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2023.12.010.

Murphy M et al. Women’s experiences of promotion and tenure in academic medicine and potential implications for gender disparities in career advancement: A qualitative analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Sep 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25843.

Sambunjak D et al. Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006 Sep 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103.

Shen MR et al. Impact of mentoring on academic career success for women in medicine: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2022 Mar 1. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004563.

A Simplified Approach to Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) represents a spectrum of symptoms involving sensory and emptying abnormalities of the bowel and bladder and pelvic organ prolapse. The pelvic floor refers to a group of muscles that spans the pelvic outlet, providing support to the pelvic organs and coordinating constrictor mechanisms to control urination and defecation. Symptoms reported by patients experiencing PFD include involuntary loss of stool or urine, incomplete emptying of the bowel and bladder, a sensation of fullness, bulging in the vagina, and sexual dysfunction.1

As such, symptoms related to PFD are very common concerns raised by patients to their gastroenterologists. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey show that 23.7% of women over the age of 20 had at least one symptom of PFD.2 Unfortunately, patients experiencing pelvic floor dysfunction often are hesitant to seek care because of embarrassment or perception that limited treatment options exist for their symptoms.

Pelvic Floor Anatomy

Regions of the pelvis are often referred to by anatomic compartment: anterior (bladder and urethra), middle (vagina and uterus or prostate), and posterior (colon, rectum, and anal canal). Supporting these compartments is the levator ani, a muscle group that is used synonymously with the term “pelvic diaphragm.”

Continence of stool is provided by the anal sphincter muscles and the puborectalis muscle, which wraps around the posterior aspect of the anorectal canal. Damage to the musculature or sensory perception to this area may result in fecal incontinence. Defecation is a coordinated process during which the abdominal and rectal muscles contract, while the anal sphincter muscles and puborectalis simultaneously relax. A disturbance in neuromuscular coordination (dyssynergic defecation) or structural pathology such as pelvic organ prolapse may lead to obstructed defecation.

PFD is thought to be a result of one or more insults to the pelvic floor such as chronic straining, childbirth, iatrogenic injury, or systemic disease such as diabetes.3

Evaluation of PFD Symptoms

Patients presenting with suspected PFD necessitate a comprehensive interdisciplinary assessment. In addition to obtaining a medical, surgical, and obstetric history, details about symptoms and lifestyle should include toileting habits, diet, and physical activity. The Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) is a commonly used tool that can be employed in the clinical setting.4

A pelvic exam can reveal pelvic organ prolapse and other mucosal pathology. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q) is a widely used classification system for describing pelvic organ prolapse.5 Protrusion of the rectal wall into the vagina is referred to as a rectocele, while prolapse of small bowel into the upper posterior wall of the vagina is called an enterocele. While the finding of a rectocele on exam is common in parous women and may not cause any symptoms, a larger rectocele may cause a sensation of incomplete evacuation of stool.

A digital rectal exam (DRE) should be performed to assess pelvic floor function and help identify structural abnormalities.

Initial Management

A stepwise approach to the management of PFD can allow many patients to be effectively treated without the need for surgical intervention. For patients reporting liquid stool consistency, the evaluation should pivot toward the workup and management of diarrhea, which can easily overwhelm continence mechanisms and cause fecal incontinence. Fiber supplementation to normalize stool consistency is considered first-line therapy for patients presenting with both fecal incontinence and obstructed defecation. Other tools for fecal incontinence include avoiding foods that trigger diarrhea and use of loperamide.6 For patients with obstructed defecation, a trial of laxatives can be followed by a prescription agent if needed, such as a secretagogue or prokinetic.7

Vaginal splinting is a technique that can be used in patients with rectocele, whereby a finger is inserted into the vagina and pressure is applied on the posterior vaginal wall toward the rectum. Reducing the rectocele can facilitate emptying stool from the rectum and prevent leakage of retained stool.8 Similarly, use of rectal irrigation enemas can also help clear retained stool.

Pelvic floor physical therapists examine the strength, coordination, and tone of the pelvic floor muscles. When hypertonic musculature is present, manual interventions may be performed including trigger point release, myofascial release, and dry needling.9 When hypotonic musculature or dyssynergia is present, strengthening and neuromuscular re-education are recommended. Biofeedback can be administered via surface electromyography and/or balloon training to improve rectal sensitivity. Proper defecation techniques, including positioning, breathing, and behavioral modifications, improve clinical outcomes.

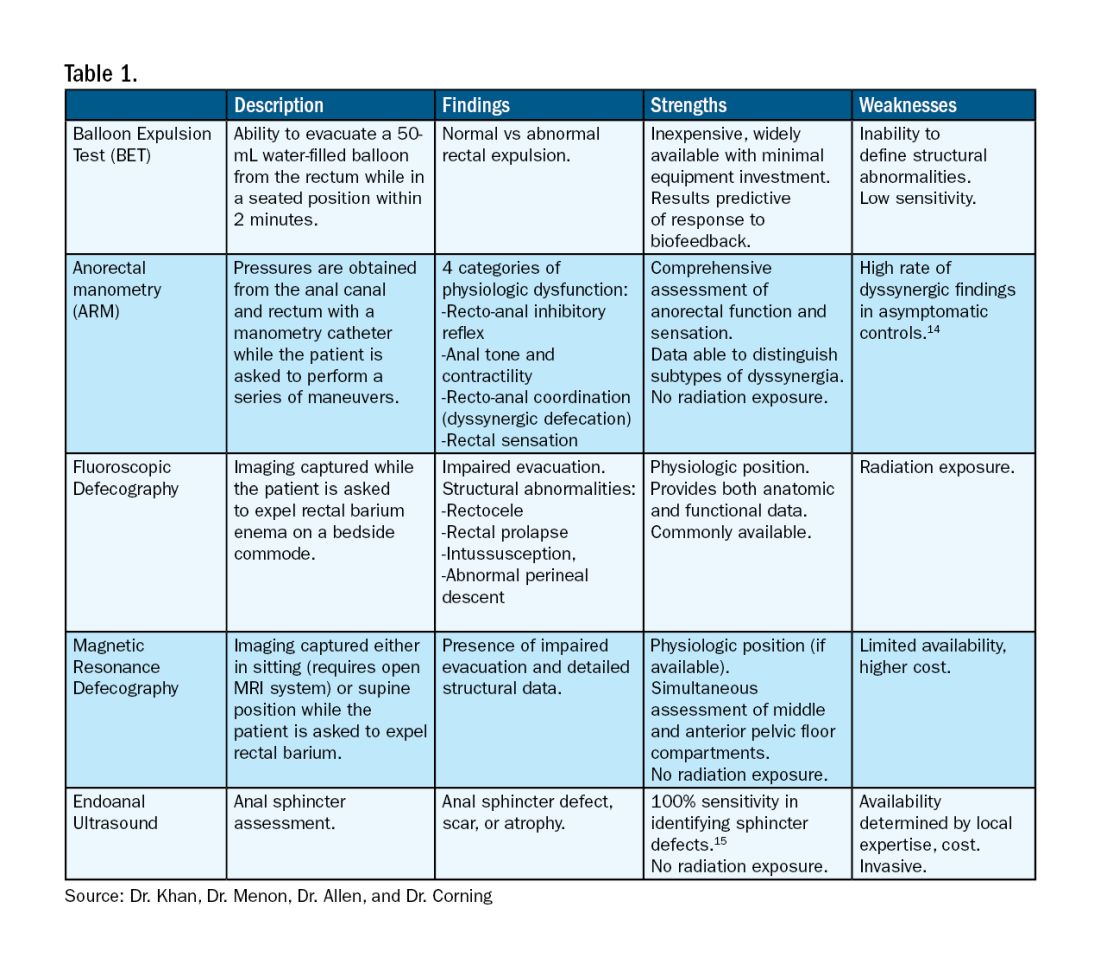

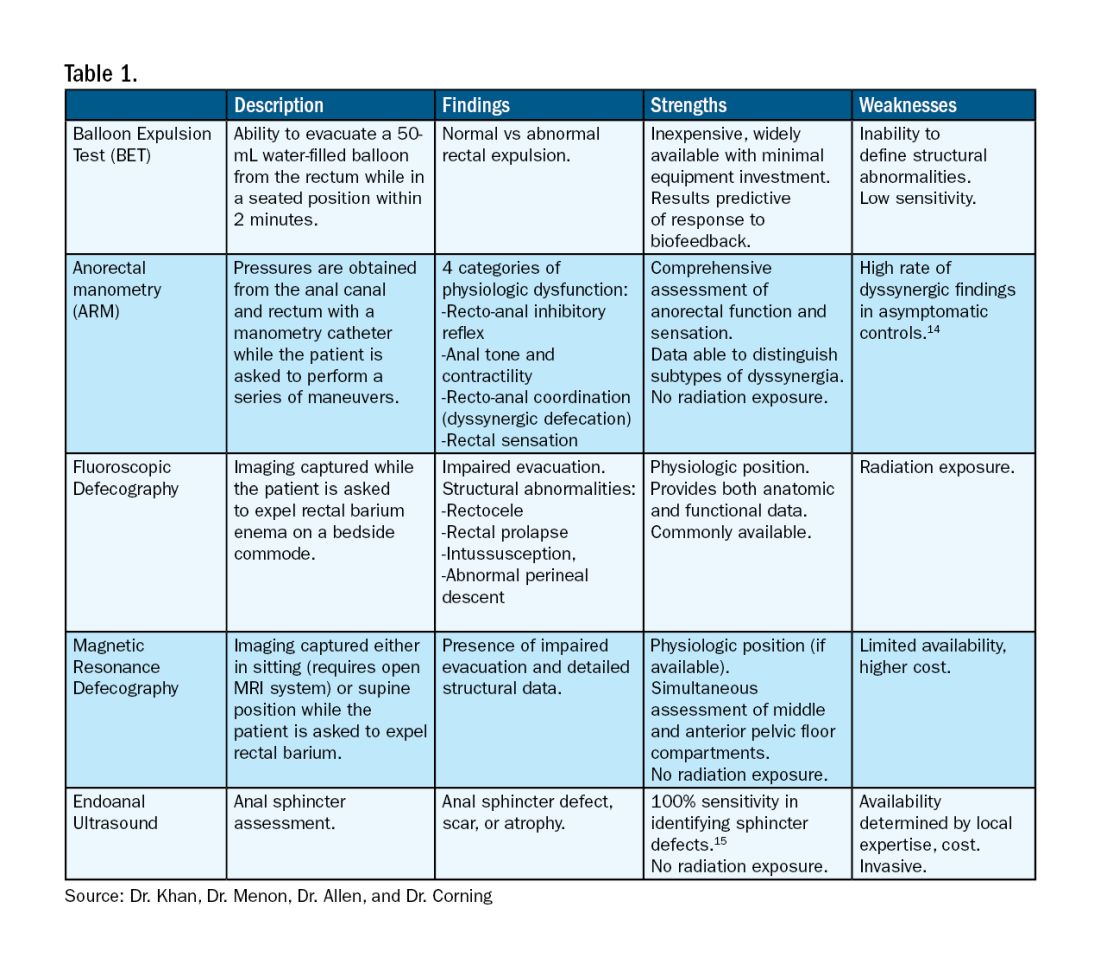

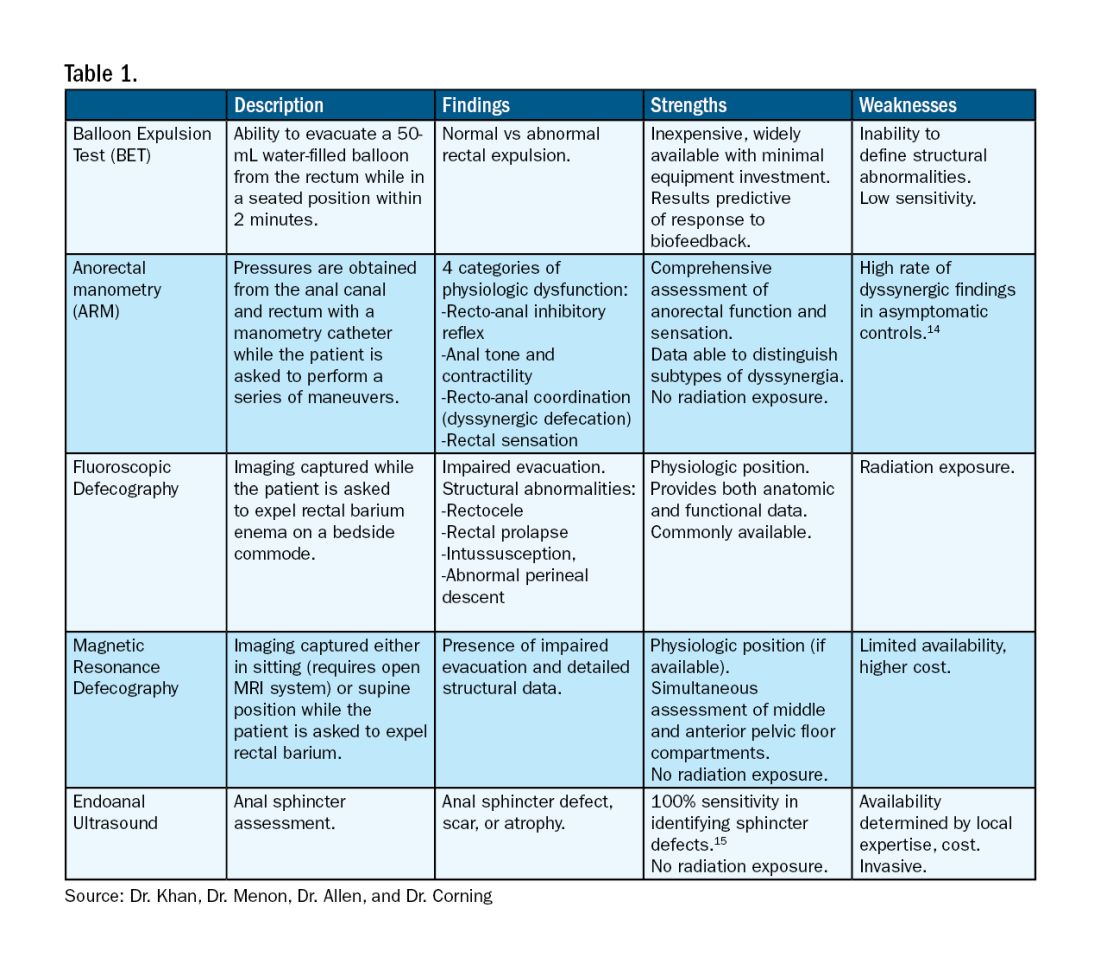

Diagnostic Testing

For patients who do not improve with conservative management, further testing is recommended to characterize the underlying pathology. Typically, anorectal manometry (ARM) is performed in conjunction with the balloon expulsion test and imaging. Each modality has its strengths and limitations (see Table 1).

ARM allows for the assessment of rectal sensation and recto-anal pressures and coordination.10

Dynamic imaging, by barium defecography under fluoroscopy or MRI, captures anatomy at rest and with simulated defecation to identify pelvic organ prolapse, compartmental defects, and organ mobility.11 Endoanal ultrasonography is considered in patients experiencing fecal incontinence to evaluate the integrity of the anal sphincter muscles.

Minimally Invasive Procedures and Surgical Options for PFD

Functional abnormalities such as dyssynergia often coexist with structural abnormalities. Because structural abnormalities are commonly found in asymptomatic patients, noninvasive functional therapy, such as pelvic floor physical therapy and anorectal biofeedback, are preferred prior to surgical repair of a structural finding. For patients with fecal incontinence, sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) has emerged as a preferred therapy due to demonstrated efficacy in symptom improvement.12 Sphincteroplasty is reserved for those with acute sphincter injury or failure of SNS.

In patients with findings of intussusception, prolapse, or rectocele that have not responded to conservative therapy, referral for surgical repair may be considered. While the specific surgical approach will depend on many factors, the goal is typically excision and/or suspension of rectal tissue and reinforcement of the rectovaginal septum.

It is critical that we are equipped with the available knowledge and tools to provide these patients with optimal care.

Dr. Khan, Dr. Menon, Dr. Allen, and Dr. Corning are based at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. They report no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Grimes WR and Stratton M. Pelvic floor dysfunction. 2023 Jun 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (Fla.): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. PMID: 32644672.

2. Nygaard I et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008 Sep 17. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311.

3. Lawrence JM et al. Pelvic floor disorders, diabetes, and obesity in women: Findings from the Kaiser Permanente Continence Associated Risk Epidemiology Study. Diabetes Care. 2007 Oct. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0262.

4. Barber MD et al. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025.

5. Persu C et al. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q) — A new era in pelvic prolapse staging. J Med Life. 2011 Jan-Mar. PMID: 21505577.

6. Wald A et al. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 1. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001507.

7. Bharucha AE and Lacy BE. Mechanisms, evaluation, and management of chronic constipation. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034.

8. Menees S and Chey WD. Fecal incontinence: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and updated treatment strategies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2022 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2021.10.005.

9. Wallace SL et al. Pelvic floor physical therapy in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction in women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000584.

10. Carrington EV et al. The international anorectal physiology working group (IAPWG) recommendations: Standardized testing protocol and the London classification for disorders of anorectal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13679.

11. El Sayed RF et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pelvic floor dysfunction — Joint recommendations of the ESUR and ESGAR Pelvic Floor Working Group. Eur Radiol. 2017 May. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4471-7.

12. Thaha MA et al. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 24. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004464.pub3.

13. Chiarioni G et al. Biofeedback benefits only patients with outlet dysfunction, not patients with isolated slow transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2005 Jul. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.015.

14. Grossi U et al. Diagnostic accuracy study of anorectal manometry for diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation. Gut. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308835.

15. Albuquerque A. Endoanal ultrasonography in fecal incontinence: Current and future perspectives. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jun 10. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i6.575.

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) represents a spectrum of symptoms involving sensory and emptying abnormalities of the bowel and bladder and pelvic organ prolapse. The pelvic floor refers to a group of muscles that spans the pelvic outlet, providing support to the pelvic organs and coordinating constrictor mechanisms to control urination and defecation. Symptoms reported by patients experiencing PFD include involuntary loss of stool or urine, incomplete emptying of the bowel and bladder, a sensation of fullness, bulging in the vagina, and sexual dysfunction.1

As such, symptoms related to PFD are very common concerns raised by patients to their gastroenterologists. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey show that 23.7% of women over the age of 20 had at least one symptom of PFD.2 Unfortunately, patients experiencing pelvic floor dysfunction often are hesitant to seek care because of embarrassment or perception that limited treatment options exist for their symptoms.

Pelvic Floor Anatomy

Regions of the pelvis are often referred to by anatomic compartment: anterior (bladder and urethra), middle (vagina and uterus or prostate), and posterior (colon, rectum, and anal canal). Supporting these compartments is the levator ani, a muscle group that is used synonymously with the term “pelvic diaphragm.”

Continence of stool is provided by the anal sphincter muscles and the puborectalis muscle, which wraps around the posterior aspect of the anorectal canal. Damage to the musculature or sensory perception to this area may result in fecal incontinence. Defecation is a coordinated process during which the abdominal and rectal muscles contract, while the anal sphincter muscles and puborectalis simultaneously relax. A disturbance in neuromuscular coordination (dyssynergic defecation) or structural pathology such as pelvic organ prolapse may lead to obstructed defecation.

PFD is thought to be a result of one or more insults to the pelvic floor such as chronic straining, childbirth, iatrogenic injury, or systemic disease such as diabetes.3

Evaluation of PFD Symptoms

Patients presenting with suspected PFD necessitate a comprehensive interdisciplinary assessment. In addition to obtaining a medical, surgical, and obstetric history, details about symptoms and lifestyle should include toileting habits, diet, and physical activity. The Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) is a commonly used tool that can be employed in the clinical setting.4

A pelvic exam can reveal pelvic organ prolapse and other mucosal pathology. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q) is a widely used classification system for describing pelvic organ prolapse.5 Protrusion of the rectal wall into the vagina is referred to as a rectocele, while prolapse of small bowel into the upper posterior wall of the vagina is called an enterocele. While the finding of a rectocele on exam is common in parous women and may not cause any symptoms, a larger rectocele may cause a sensation of incomplete evacuation of stool.

A digital rectal exam (DRE) should be performed to assess pelvic floor function and help identify structural abnormalities.

Initial Management

A stepwise approach to the management of PFD can allow many patients to be effectively treated without the need for surgical intervention. For patients reporting liquid stool consistency, the evaluation should pivot toward the workup and management of diarrhea, which can easily overwhelm continence mechanisms and cause fecal incontinence. Fiber supplementation to normalize stool consistency is considered first-line therapy for patients presenting with both fecal incontinence and obstructed defecation. Other tools for fecal incontinence include avoiding foods that trigger diarrhea and use of loperamide.6 For patients with obstructed defecation, a trial of laxatives can be followed by a prescription agent if needed, such as a secretagogue or prokinetic.7

Vaginal splinting is a technique that can be used in patients with rectocele, whereby a finger is inserted into the vagina and pressure is applied on the posterior vaginal wall toward the rectum. Reducing the rectocele can facilitate emptying stool from the rectum and prevent leakage of retained stool.8 Similarly, use of rectal irrigation enemas can also help clear retained stool.

Pelvic floor physical therapists examine the strength, coordination, and tone of the pelvic floor muscles. When hypertonic musculature is present, manual interventions may be performed including trigger point release, myofascial release, and dry needling.9 When hypotonic musculature or dyssynergia is present, strengthening and neuromuscular re-education are recommended. Biofeedback can be administered via surface electromyography and/or balloon training to improve rectal sensitivity. Proper defecation techniques, including positioning, breathing, and behavioral modifications, improve clinical outcomes.

Diagnostic Testing

For patients who do not improve with conservative management, further testing is recommended to characterize the underlying pathology. Typically, anorectal manometry (ARM) is performed in conjunction with the balloon expulsion test and imaging. Each modality has its strengths and limitations (see Table 1).

ARM allows for the assessment of rectal sensation and recto-anal pressures and coordination.10

Dynamic imaging, by barium defecography under fluoroscopy or MRI, captures anatomy at rest and with simulated defecation to identify pelvic organ prolapse, compartmental defects, and organ mobility.11 Endoanal ultrasonography is considered in patients experiencing fecal incontinence to evaluate the integrity of the anal sphincter muscles.

Minimally Invasive Procedures and Surgical Options for PFD

Functional abnormalities such as dyssynergia often coexist with structural abnormalities. Because structural abnormalities are commonly found in asymptomatic patients, noninvasive functional therapy, such as pelvic floor physical therapy and anorectal biofeedback, are preferred prior to surgical repair of a structural finding. For patients with fecal incontinence, sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) has emerged as a preferred therapy due to demonstrated efficacy in symptom improvement.12 Sphincteroplasty is reserved for those with acute sphincter injury or failure of SNS.