User login

Non-Invasive Blood and Stool CRC Screening Tests: Available Modalities and Their Clinical Application

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening significantly reduces CRC incidence and mortality, but only 65% of eligible individuals report being up-to-date with screening.1 Colonoscopy is the most widely used opportunistic screening method in the United States and is associated with many barriers to uptake. Providing patients a choice of colonoscopy and/or stool-based tests, improves screening adherence in randomized controlled trials.2,3 Non-invasive screening options have expanded from stool occult blood and multi-target DNA tests, to multi-target stool RNA tests, and novel blood-based tests, the latter only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for patients who refuse colonoscopy and stool-based tests.

Stool Occult Blood Tests

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) significantly reduces CRC mortality by 33%-35% when implemented on an annual or biennial basis.4,5 Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) has supplanted gFOBT with advantages including independence from dietary restriction and medication-related interference, use of antibodies specific to human globin, and the need for only a single stool sample.

The most common threshold for a positive FIT in the U.S. is ≥ 20 micrograms (μg) of hemoglobin per gram (g) of stool. FIT is approved by the FDA as a qualitative positive or negative result based on a threshold value.6 A meta-analysis summarized test characteristics of commercially available FITs at various detection thresholds.7 The CRC sensitivity and specificity was 75% and 95% for ≥ 20 ug hemoglobin/g stool, and 91% and 90% for 10 ug hemoglobin/g stool, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas ranged from 25% at 20 μg/g to 40% at a 10 μg/g. Programmatic use of FIT in adults ages ≥ 50 years at 20 ug/g of stool, in cohort and case control studies, has been shown to significantly reduce CRC mortality by 33%-40% and advanced stage CRC by 34%.8,9

Over 57,000 average-risk individuals ages 50–69 years were randomized to biennial FIT or one-time colonoscopy and followed for 10 years.10 CRC mortality and incidence was similar between the groups: 0.22% with FIT vs. 0.24% with colonoscopy and 1.13% with FIT vs. 1.22% with colonoscopy, respectively. Thus, confirming biennial FIT screening is non-inferior to one-time colonoscopy in important CRC-related outcomes.

Multi-Target Stool Tests

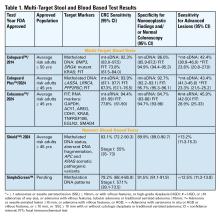

Two multitarget stool DNA tests (mt-sDNA) known as Cologuard™ and Cologuard Plus™ have been approved by the FDA. Both tests include a FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin per gram of stool) combined with DNA methylation markers. The test result is qualitative, reported as a positive or negative. Cologuard™ markers include methylated BMP3, NDRG4, and mutant KRAS while Cologuard Plus™ assesses methylated LASS4, LRRC4, and PPP2R5C. The respective mt-sDNA tests were studied in 9989 of 12,776 and 20,176 of 26,758 average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy and the results were compared to a commercially available FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool).11,12 In both trials, the sensitivity for CRC and advanced precancerous lesions was higher with the mt-sDNA tests compared to FIT but had a significantly lower specificity for advanced precancerous lesions versus FIT (see Table 1). An age-related decline in specificity was noted in both trials with mt-sDNA, a trend not observed with FIT. This reduction may be attributed to age-related DNA methylation.

Multi-Target Stool RNA Test

A multi-target stool RNA test (mt-sRNA) commercially available as ColoSense™ is FDA-approved. It combines FIT (at a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool) with RNA-based stool markers. The combined results of the RNA markers, FIT, and smoking status provide a qualitative single test result. In the trial, 8,920 adults aged ≥45 underwent the mt-sRNA test and FIT followed by colonoscopy (13). The mt-sRNA showed higher sensitivity for CRC than FIT (94.4% versus 77.8%) and advanced adenomas (45.9% versus 28.9%) but lower CRC specificity (84.7% vs 94.7%) (Table 1). Unlike mt-sDNA-based tests, mt-sRNA showed consistent performance across age groups, addressing concerns about age-related declines in specificity attributed to DNA methylation.

Blood-Based Tests

In 2014, the first blood-based (BBT) CRC screening test known as Epi proColon™ was FDA but not Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved for average-risk adults ≥50 years of age who are offered and refused other U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed CRC screening tests. It is a qualitative test for detection of circulating methylated Septin 9 (mSeptin9). The accuracy of mSeptin9 to detect CRC was assessed in a subset of 7941 asymptomatic average risk adults undergoing screening colonoscopy.14 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC were 48% and 91.5%, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas was 11.2%. An increase in sensitivity to 63.9% and reduction in specificity to 88.4% for CRC was demonstrated in a sub-analysis of available samples where an additional (third) polymerase chain replicate was performed. Epi proColon™ is not currently reimbursed by Medicare and not endorsed in the latest USPSTF guidelines.

Technologic advancements have improved the detection of circulating tumor markers in the blood. The Shield™ BBT approved by the FDA in 2024 for average risk adults ≥ 45 years integrates three types of cfDNA data (epigenetic changes resulting in the aberrant methylation or fragmentation patterns, and genomic changes resulting in somatic mutations) into a positive or negative test result. In the trial, 22,877 average-risk, asymptomatic individuals ages 45–84 were enrolled and clinical validation was performed in 7,861 of the participants.15 The sensitivity for CRC was 83.1% which decreased to 55% for stage I tumors (see Table 1). CRC specificity was 89.6% and the sensitivity for advanced adenomas and large sessile serrated lesions was 13.2%.

Another BBT SimpleScreen™, which is not yet FDA-approved, analyzed circulating, cell-free DNA methylation patterns in 27,010 evaluable average-risk, asymptomatic adults ages 45–85 years undergoing screening colonoscopy.16 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC was 79.2% and 91.5%, respectively. Similar to Shield, the sensitivity for stage I CRC was low at 57.1%. The sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions, a secondary endpoint, was 12.5% which did not meet the prespecified study criteria.

Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness

Modeling studies have evaluated novel noninvasive CRC screening tests compared to FIT and colonoscopy.17-20 One compared a hypothetical BBT performed every 3 years that meets the minimum CMS threshold CRC sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 90%, respectively, to other established CRC screening tests beginning at age 45.17 Every 3-year BBT reduced CRC incidence and mortality by 40% and 52%, respectively compared to no screening. However, the reductions were much lower than yearly FIT (72% and 76%, respectively), every 10 year colonoscopy (79% and 81%, respectively), and triennial mt-sDNA (68% and 73%, respectively). The BBT resulted in fewer quality-adjusted life-years per person compared to the alternatives.

Additionally, FIT, colonoscopy, and mt-sDNA were less costly and more effective. Advanced precancerous lesion detection was a key measure for a test’s effectiveness. BBT characteristics would require a CRC sensitivity and specificity of >90% and 90%, respectively, and 80% sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions at a cost of ≤$120–$140 to be cost-effective compared to FIT at comparable participation rates.

Another analysis simulated colorectal neoplasia progression and compared clinical effectiveness and cost between annual FIT, every 3 year stool mt-sRNA, every 3 year stool mt-sDNA tests, every 3 year stool Shield™; these outcomes were compared to colonoscopy every 10 years and no screening in adults ≥ age 45 over different adherence rates.19 At real-world adherence rates of 60%, colonoscopy prevented most CRC cases and associated deaths. FIT was the most cost-effective strategy at all adherence levels. Between the multi-target stool tests and Shield™, mt-sRNA was the most cost-effective. Compared to FIT, mt-sRNA reduced CRC cases and deaths by 1% and 14%.

The third study evaluated CRC incidence and mortality, quality-adjusted life-years and costs with annual FIT, colonoscopy every 10 years, mt- sDNA tests, mt-sRNA test, and BBTs.20 The latest mt-sDNA (Colguard plus™) and mt-sRNA achieved benefits approaching FIT but the Shield™ test was substantially less effective. The authors hypothesized that if 15% of the population substituted Shield™ for current effective CRC screening strategies, an increase in CRC deaths would occur and require 9-10% of the unscreened population to uptake screening with Shield to avert the increases in CRC deaths due to the substitution effect.

Clinical Implications

The effectiveness of non-invasive screening strategies depends on their diagnostic performance, adherence, and ensuring a timely colonoscopy after a positive test. Two claims-based studies found 47.9% and 49% of patients underwent follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months of an abnormal stool or BBT CRC screening test, respectively.21-22

Conclusions

Non-invasive stool mt-sDNA and mt-sRNA have higher effectiveness than the new BBTs. BBTs can lead to increased CRC mortality if substituted for the FDA and CMS-approved, USPSTF-endorsed, CRC screening modalities. If future BBTs increase their sensitivity for CRC (including early-stage CRC) and advanced precancerous lesions and decrease their cost, they may prove to have similar cost-effectiveness to stool-based tests. Currently, BBTs are not a substitute for colonoscopy or other stool tests and should be offered to patients who refuse other CRC screening modalities. A personalized, risk-adapted approach, paired with improved adherence and follow-up are essential to optimize the population-level impact of CRC screening and ensure equitable, effective cancer prevention.

Dr. Gupta is based at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Dr. Burke and Dr. Macaron are based at the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Macaron declared no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Burke declared research support from Emtora Biosciences. She is a current consultant for Lumabridge, and has been a consultant for Sebela and Almirall. She also disclosed support from Myriad, Genzyme, Ferring, Merck, Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Salix, and Natera.

References

1. Benavidez GA, Sedani AE, Felder TM, Asare M, Rogers CR. Rural-urban disparities and trends in cancer screening: an analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data (2018-2022). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Nov 1;8(6):pkae113

2. Galoosian A, Dai H, Croymans D, et al. Population Health Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies in Adults Aged 45 to 49 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Aug 4:e2512049. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.12049. Epub ahead of print.

3. Pilonis ND, Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, et al. Participation in Competing Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Health Services Study (PICCOLINO Study). Gastroenterology. 2021 Mar;160(4):1097-1105.

4. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–1114.

5. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. PMID: 8942774.

6. Burke CA, Lieberman D, Feuerstein JD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Approach to the Use of Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Options: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):952-956. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.075. Epub 2022 Jan 28. PMID: 35094786.

7. Imperiale TF, Gruber RN Stump TE, et al. Performance characteristics of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170(5):319-329

8. Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Screening and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Death. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2423671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23671.

9. Chiu HM, Jen GH, Wang YW, et al. Long-term effectiveness of faecal immunochemical test screening for proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Gut. 2021 Dec;70(12):2321-2329. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322545. Epub 2021 Jan 25.

10. Castells A, Quintero E, Bujanda L, et al; COLONPREV study investigators. Effect of invitation to colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test screening on colorectal cancer mortality (COLONPREV): a pragmatic, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2025;405(10486):1231–1239

11. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297

12. Imperiale TF, Porter K, Zella J, et al. Next-Generation Multitarget Stool DNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):984-993

13. Barnell EK, Wurtzler EM, La Rocca J, et al. Multitarget Stool RNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. JAMA. 2023 Nov 14;330(18):1760-1768.

14. Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2014; 63:317–325.

15. Chung DC, Gray DM 2nd, Singh H, et al. A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):973-983.

16. Shaukat A, Burke CA, Chan AT, et al. Clinical Validation of a Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Blood Test to Screen for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA. 2025 Jul 1;334(1):56-63.

17. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Weng Y, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening with Blood-Based Biomarkers (Liquid Biopsy) vs Fecal Tests or Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2024 Jul;167(2):378-391.

18. van den Puttelaar R, Nascimento de Lima P, Knudsen AB, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with a blood test that meets the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services coverage decision. Gastroenterology 2024;167:368–377.

19. Shaukat A, Levin TR, Liang PS. Cost-effectiveness of Novel Noninvasive Screening Tests for Colorectal Neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jun 23:S1542-3565(25)00525-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40562290.

20. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Schoen RE, Dominitz JA, Lieberman D. Projected Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Novel Molecular Blood-Based or Stool-Based Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Dec;177(12):1610-1620.

20. Ciemins EL, Mohl JT, Moreno CA, Colangelo F, Smith RA, Barton M. Development of a Follow-Up Measure to Ensure Complete Screening for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e242693. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2693.

21. Zaki TA, Zhang NJ, Forbes SP, Raymond VM, Das AK, May FP. Colonoscopic Follow-up After Abnormal Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Results. Gastroenterology. 2025 Jul 21:S0016-5085(25)05775-0. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.07.019. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40744392.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening significantly reduces CRC incidence and mortality, but only 65% of eligible individuals report being up-to-date with screening.1 Colonoscopy is the most widely used opportunistic screening method in the United States and is associated with many barriers to uptake. Providing patients a choice of colonoscopy and/or stool-based tests, improves screening adherence in randomized controlled trials.2,3 Non-invasive screening options have expanded from stool occult blood and multi-target DNA tests, to multi-target stool RNA tests, and novel blood-based tests, the latter only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for patients who refuse colonoscopy and stool-based tests.

Stool Occult Blood Tests

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) significantly reduces CRC mortality by 33%-35% when implemented on an annual or biennial basis.4,5 Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) has supplanted gFOBT with advantages including independence from dietary restriction and medication-related interference, use of antibodies specific to human globin, and the need for only a single stool sample.

The most common threshold for a positive FIT in the U.S. is ≥ 20 micrograms (μg) of hemoglobin per gram (g) of stool. FIT is approved by the FDA as a qualitative positive or negative result based on a threshold value.6 A meta-analysis summarized test characteristics of commercially available FITs at various detection thresholds.7 The CRC sensitivity and specificity was 75% and 95% for ≥ 20 ug hemoglobin/g stool, and 91% and 90% for 10 ug hemoglobin/g stool, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas ranged from 25% at 20 μg/g to 40% at a 10 μg/g. Programmatic use of FIT in adults ages ≥ 50 years at 20 ug/g of stool, in cohort and case control studies, has been shown to significantly reduce CRC mortality by 33%-40% and advanced stage CRC by 34%.8,9

Over 57,000 average-risk individuals ages 50–69 years were randomized to biennial FIT or one-time colonoscopy and followed for 10 years.10 CRC mortality and incidence was similar between the groups: 0.22% with FIT vs. 0.24% with colonoscopy and 1.13% with FIT vs. 1.22% with colonoscopy, respectively. Thus, confirming biennial FIT screening is non-inferior to one-time colonoscopy in important CRC-related outcomes.

Multi-Target Stool Tests

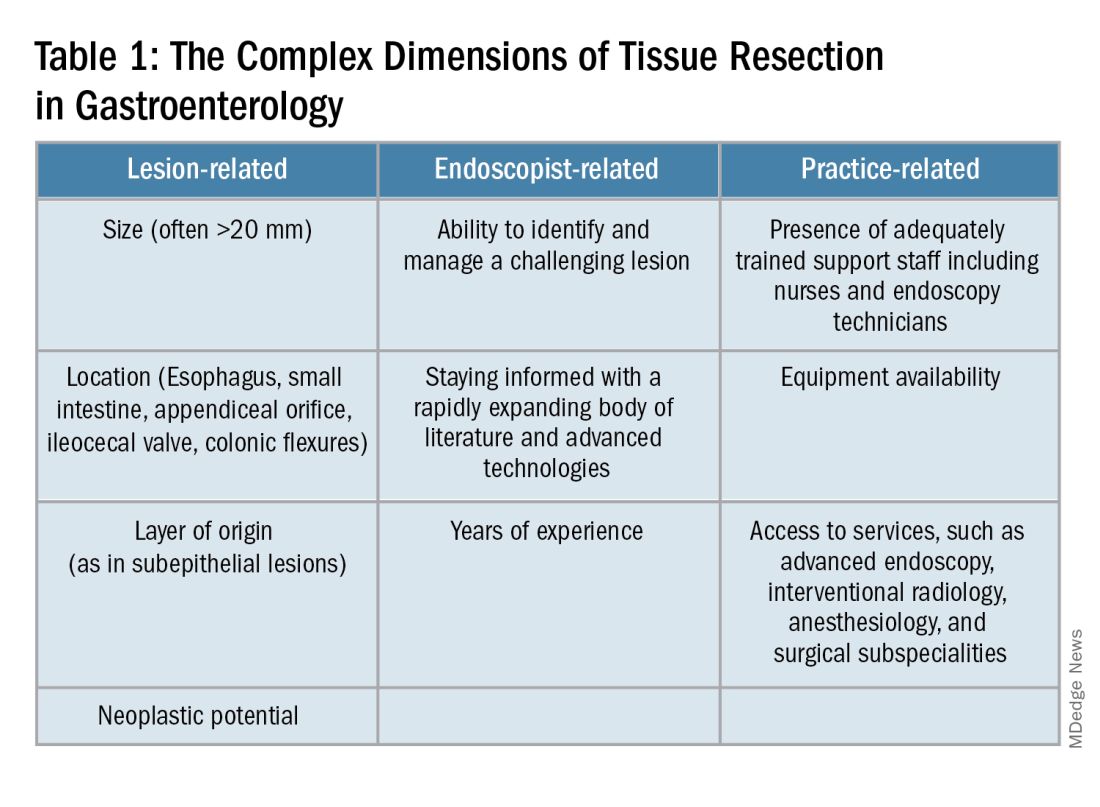

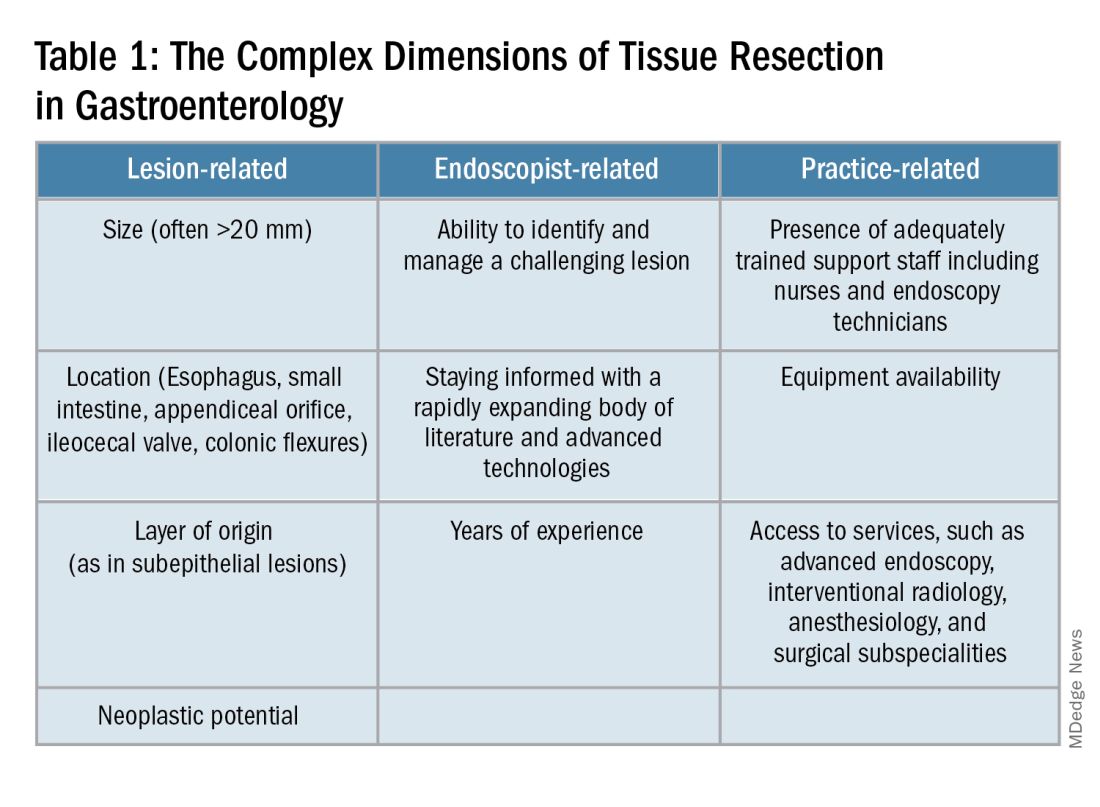

Two multitarget stool DNA tests (mt-sDNA) known as Cologuard™ and Cologuard Plus™ have been approved by the FDA. Both tests include a FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin per gram of stool) combined with DNA methylation markers. The test result is qualitative, reported as a positive or negative. Cologuard™ markers include methylated BMP3, NDRG4, and mutant KRAS while Cologuard Plus™ assesses methylated LASS4, LRRC4, and PPP2R5C. The respective mt-sDNA tests were studied in 9989 of 12,776 and 20,176 of 26,758 average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy and the results were compared to a commercially available FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool).11,12 In both trials, the sensitivity for CRC and advanced precancerous lesions was higher with the mt-sDNA tests compared to FIT but had a significantly lower specificity for advanced precancerous lesions versus FIT (see Table 1). An age-related decline in specificity was noted in both trials with mt-sDNA, a trend not observed with FIT. This reduction may be attributed to age-related DNA methylation.

Multi-Target Stool RNA Test

A multi-target stool RNA test (mt-sRNA) commercially available as ColoSense™ is FDA-approved. It combines FIT (at a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool) with RNA-based stool markers. The combined results of the RNA markers, FIT, and smoking status provide a qualitative single test result. In the trial, 8,920 adults aged ≥45 underwent the mt-sRNA test and FIT followed by colonoscopy (13). The mt-sRNA showed higher sensitivity for CRC than FIT (94.4% versus 77.8%) and advanced adenomas (45.9% versus 28.9%) but lower CRC specificity (84.7% vs 94.7%) (Table 1). Unlike mt-sDNA-based tests, mt-sRNA showed consistent performance across age groups, addressing concerns about age-related declines in specificity attributed to DNA methylation.

Blood-Based Tests

In 2014, the first blood-based (BBT) CRC screening test known as Epi proColon™ was FDA but not Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved for average-risk adults ≥50 years of age who are offered and refused other U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed CRC screening tests. It is a qualitative test for detection of circulating methylated Septin 9 (mSeptin9). The accuracy of mSeptin9 to detect CRC was assessed in a subset of 7941 asymptomatic average risk adults undergoing screening colonoscopy.14 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC were 48% and 91.5%, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas was 11.2%. An increase in sensitivity to 63.9% and reduction in specificity to 88.4% for CRC was demonstrated in a sub-analysis of available samples where an additional (third) polymerase chain replicate was performed. Epi proColon™ is not currently reimbursed by Medicare and not endorsed in the latest USPSTF guidelines.

Technologic advancements have improved the detection of circulating tumor markers in the blood. The Shield™ BBT approved by the FDA in 2024 for average risk adults ≥ 45 years integrates three types of cfDNA data (epigenetic changes resulting in the aberrant methylation or fragmentation patterns, and genomic changes resulting in somatic mutations) into a positive or negative test result. In the trial, 22,877 average-risk, asymptomatic individuals ages 45–84 were enrolled and clinical validation was performed in 7,861 of the participants.15 The sensitivity for CRC was 83.1% which decreased to 55% for stage I tumors (see Table 1). CRC specificity was 89.6% and the sensitivity for advanced adenomas and large sessile serrated lesions was 13.2%.

Another BBT SimpleScreen™, which is not yet FDA-approved, analyzed circulating, cell-free DNA methylation patterns in 27,010 evaluable average-risk, asymptomatic adults ages 45–85 years undergoing screening colonoscopy.16 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC was 79.2% and 91.5%, respectively. Similar to Shield, the sensitivity for stage I CRC was low at 57.1%. The sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions, a secondary endpoint, was 12.5% which did not meet the prespecified study criteria.

Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness

Modeling studies have evaluated novel noninvasive CRC screening tests compared to FIT and colonoscopy.17-20 One compared a hypothetical BBT performed every 3 years that meets the minimum CMS threshold CRC sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 90%, respectively, to other established CRC screening tests beginning at age 45.17 Every 3-year BBT reduced CRC incidence and mortality by 40% and 52%, respectively compared to no screening. However, the reductions were much lower than yearly FIT (72% and 76%, respectively), every 10 year colonoscopy (79% and 81%, respectively), and triennial mt-sDNA (68% and 73%, respectively). The BBT resulted in fewer quality-adjusted life-years per person compared to the alternatives.

Additionally, FIT, colonoscopy, and mt-sDNA were less costly and more effective. Advanced precancerous lesion detection was a key measure for a test’s effectiveness. BBT characteristics would require a CRC sensitivity and specificity of >90% and 90%, respectively, and 80% sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions at a cost of ≤$120–$140 to be cost-effective compared to FIT at comparable participation rates.

Another analysis simulated colorectal neoplasia progression and compared clinical effectiveness and cost between annual FIT, every 3 year stool mt-sRNA, every 3 year stool mt-sDNA tests, every 3 year stool Shield™; these outcomes were compared to colonoscopy every 10 years and no screening in adults ≥ age 45 over different adherence rates.19 At real-world adherence rates of 60%, colonoscopy prevented most CRC cases and associated deaths. FIT was the most cost-effective strategy at all adherence levels. Between the multi-target stool tests and Shield™, mt-sRNA was the most cost-effective. Compared to FIT, mt-sRNA reduced CRC cases and deaths by 1% and 14%.

The third study evaluated CRC incidence and mortality, quality-adjusted life-years and costs with annual FIT, colonoscopy every 10 years, mt- sDNA tests, mt-sRNA test, and BBTs.20 The latest mt-sDNA (Colguard plus™) and mt-sRNA achieved benefits approaching FIT but the Shield™ test was substantially less effective. The authors hypothesized that if 15% of the population substituted Shield™ for current effective CRC screening strategies, an increase in CRC deaths would occur and require 9-10% of the unscreened population to uptake screening with Shield to avert the increases in CRC deaths due to the substitution effect.

Clinical Implications

The effectiveness of non-invasive screening strategies depends on their diagnostic performance, adherence, and ensuring a timely colonoscopy after a positive test. Two claims-based studies found 47.9% and 49% of patients underwent follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months of an abnormal stool or BBT CRC screening test, respectively.21-22

Conclusions

Non-invasive stool mt-sDNA and mt-sRNA have higher effectiveness than the new BBTs. BBTs can lead to increased CRC mortality if substituted for the FDA and CMS-approved, USPSTF-endorsed, CRC screening modalities. If future BBTs increase their sensitivity for CRC (including early-stage CRC) and advanced precancerous lesions and decrease their cost, they may prove to have similar cost-effectiveness to stool-based tests. Currently, BBTs are not a substitute for colonoscopy or other stool tests and should be offered to patients who refuse other CRC screening modalities. A personalized, risk-adapted approach, paired with improved adherence and follow-up are essential to optimize the population-level impact of CRC screening and ensure equitable, effective cancer prevention.

Dr. Gupta is based at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Dr. Burke and Dr. Macaron are based at the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Macaron declared no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Burke declared research support from Emtora Biosciences. She is a current consultant for Lumabridge, and has been a consultant for Sebela and Almirall. She also disclosed support from Myriad, Genzyme, Ferring, Merck, Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Salix, and Natera.

References

1. Benavidez GA, Sedani AE, Felder TM, Asare M, Rogers CR. Rural-urban disparities and trends in cancer screening: an analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data (2018-2022). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Nov 1;8(6):pkae113

2. Galoosian A, Dai H, Croymans D, et al. Population Health Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies in Adults Aged 45 to 49 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Aug 4:e2512049. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.12049. Epub ahead of print.

3. Pilonis ND, Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, et al. Participation in Competing Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Health Services Study (PICCOLINO Study). Gastroenterology. 2021 Mar;160(4):1097-1105.

4. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–1114.

5. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. PMID: 8942774.

6. Burke CA, Lieberman D, Feuerstein JD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Approach to the Use of Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Options: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):952-956. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.075. Epub 2022 Jan 28. PMID: 35094786.

7. Imperiale TF, Gruber RN Stump TE, et al. Performance characteristics of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170(5):319-329

8. Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Screening and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Death. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2423671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23671.

9. Chiu HM, Jen GH, Wang YW, et al. Long-term effectiveness of faecal immunochemical test screening for proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Gut. 2021 Dec;70(12):2321-2329. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322545. Epub 2021 Jan 25.

10. Castells A, Quintero E, Bujanda L, et al; COLONPREV study investigators. Effect of invitation to colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test screening on colorectal cancer mortality (COLONPREV): a pragmatic, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2025;405(10486):1231–1239

11. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297

12. Imperiale TF, Porter K, Zella J, et al. Next-Generation Multitarget Stool DNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):984-993

13. Barnell EK, Wurtzler EM, La Rocca J, et al. Multitarget Stool RNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. JAMA. 2023 Nov 14;330(18):1760-1768.

14. Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2014; 63:317–325.

15. Chung DC, Gray DM 2nd, Singh H, et al. A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):973-983.

16. Shaukat A, Burke CA, Chan AT, et al. Clinical Validation of a Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Blood Test to Screen for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA. 2025 Jul 1;334(1):56-63.

17. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Weng Y, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening with Blood-Based Biomarkers (Liquid Biopsy) vs Fecal Tests or Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2024 Jul;167(2):378-391.

18. van den Puttelaar R, Nascimento de Lima P, Knudsen AB, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with a blood test that meets the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services coverage decision. Gastroenterology 2024;167:368–377.

19. Shaukat A, Levin TR, Liang PS. Cost-effectiveness of Novel Noninvasive Screening Tests for Colorectal Neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jun 23:S1542-3565(25)00525-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40562290.

20. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Schoen RE, Dominitz JA, Lieberman D. Projected Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Novel Molecular Blood-Based or Stool-Based Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Dec;177(12):1610-1620.

20. Ciemins EL, Mohl JT, Moreno CA, Colangelo F, Smith RA, Barton M. Development of a Follow-Up Measure to Ensure Complete Screening for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e242693. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2693.

21. Zaki TA, Zhang NJ, Forbes SP, Raymond VM, Das AK, May FP. Colonoscopic Follow-up After Abnormal Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Results. Gastroenterology. 2025 Jul 21:S0016-5085(25)05775-0. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.07.019. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40744392.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening significantly reduces CRC incidence and mortality, but only 65% of eligible individuals report being up-to-date with screening.1 Colonoscopy is the most widely used opportunistic screening method in the United States and is associated with many barriers to uptake. Providing patients a choice of colonoscopy and/or stool-based tests, improves screening adherence in randomized controlled trials.2,3 Non-invasive screening options have expanded from stool occult blood and multi-target DNA tests, to multi-target stool RNA tests, and novel blood-based tests, the latter only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for patients who refuse colonoscopy and stool-based tests.

Stool Occult Blood Tests

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) significantly reduces CRC mortality by 33%-35% when implemented on an annual or biennial basis.4,5 Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) has supplanted gFOBT with advantages including independence from dietary restriction and medication-related interference, use of antibodies specific to human globin, and the need for only a single stool sample.

The most common threshold for a positive FIT in the U.S. is ≥ 20 micrograms (μg) of hemoglobin per gram (g) of stool. FIT is approved by the FDA as a qualitative positive or negative result based on a threshold value.6 A meta-analysis summarized test characteristics of commercially available FITs at various detection thresholds.7 The CRC sensitivity and specificity was 75% and 95% for ≥ 20 ug hemoglobin/g stool, and 91% and 90% for 10 ug hemoglobin/g stool, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas ranged from 25% at 20 μg/g to 40% at a 10 μg/g. Programmatic use of FIT in adults ages ≥ 50 years at 20 ug/g of stool, in cohort and case control studies, has been shown to significantly reduce CRC mortality by 33%-40% and advanced stage CRC by 34%.8,9

Over 57,000 average-risk individuals ages 50–69 years were randomized to biennial FIT or one-time colonoscopy and followed for 10 years.10 CRC mortality and incidence was similar between the groups: 0.22% with FIT vs. 0.24% with colonoscopy and 1.13% with FIT vs. 1.22% with colonoscopy, respectively. Thus, confirming biennial FIT screening is non-inferior to one-time colonoscopy in important CRC-related outcomes.

Multi-Target Stool Tests

Two multitarget stool DNA tests (mt-sDNA) known as Cologuard™ and Cologuard Plus™ have been approved by the FDA. Both tests include a FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin per gram of stool) combined with DNA methylation markers. The test result is qualitative, reported as a positive or negative. Cologuard™ markers include methylated BMP3, NDRG4, and mutant KRAS while Cologuard Plus™ assesses methylated LASS4, LRRC4, and PPP2R5C. The respective mt-sDNA tests were studied in 9989 of 12,776 and 20,176 of 26,758 average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy and the results were compared to a commercially available FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool).11,12 In both trials, the sensitivity for CRC and advanced precancerous lesions was higher with the mt-sDNA tests compared to FIT but had a significantly lower specificity for advanced precancerous lesions versus FIT (see Table 1). An age-related decline in specificity was noted in both trials with mt-sDNA, a trend not observed with FIT. This reduction may be attributed to age-related DNA methylation.

Multi-Target Stool RNA Test

A multi-target stool RNA test (mt-sRNA) commercially available as ColoSense™ is FDA-approved. It combines FIT (at a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool) with RNA-based stool markers. The combined results of the RNA markers, FIT, and smoking status provide a qualitative single test result. In the trial, 8,920 adults aged ≥45 underwent the mt-sRNA test and FIT followed by colonoscopy (13). The mt-sRNA showed higher sensitivity for CRC than FIT (94.4% versus 77.8%) and advanced adenomas (45.9% versus 28.9%) but lower CRC specificity (84.7% vs 94.7%) (Table 1). Unlike mt-sDNA-based tests, mt-sRNA showed consistent performance across age groups, addressing concerns about age-related declines in specificity attributed to DNA methylation.

Blood-Based Tests

In 2014, the first blood-based (BBT) CRC screening test known as Epi proColon™ was FDA but not Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved for average-risk adults ≥50 years of age who are offered and refused other U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed CRC screening tests. It is a qualitative test for detection of circulating methylated Septin 9 (mSeptin9). The accuracy of mSeptin9 to detect CRC was assessed in a subset of 7941 asymptomatic average risk adults undergoing screening colonoscopy.14 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC were 48% and 91.5%, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas was 11.2%. An increase in sensitivity to 63.9% and reduction in specificity to 88.4% for CRC was demonstrated in a sub-analysis of available samples where an additional (third) polymerase chain replicate was performed. Epi proColon™ is not currently reimbursed by Medicare and not endorsed in the latest USPSTF guidelines.

Technologic advancements have improved the detection of circulating tumor markers in the blood. The Shield™ BBT approved by the FDA in 2024 for average risk adults ≥ 45 years integrates three types of cfDNA data (epigenetic changes resulting in the aberrant methylation or fragmentation patterns, and genomic changes resulting in somatic mutations) into a positive or negative test result. In the trial, 22,877 average-risk, asymptomatic individuals ages 45–84 were enrolled and clinical validation was performed in 7,861 of the participants.15 The sensitivity for CRC was 83.1% which decreased to 55% for stage I tumors (see Table 1). CRC specificity was 89.6% and the sensitivity for advanced adenomas and large sessile serrated lesions was 13.2%.

Another BBT SimpleScreen™, which is not yet FDA-approved, analyzed circulating, cell-free DNA methylation patterns in 27,010 evaluable average-risk, asymptomatic adults ages 45–85 years undergoing screening colonoscopy.16 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC was 79.2% and 91.5%, respectively. Similar to Shield, the sensitivity for stage I CRC was low at 57.1%. The sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions, a secondary endpoint, was 12.5% which did not meet the prespecified study criteria.

Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness

Modeling studies have evaluated novel noninvasive CRC screening tests compared to FIT and colonoscopy.17-20 One compared a hypothetical BBT performed every 3 years that meets the minimum CMS threshold CRC sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 90%, respectively, to other established CRC screening tests beginning at age 45.17 Every 3-year BBT reduced CRC incidence and mortality by 40% and 52%, respectively compared to no screening. However, the reductions were much lower than yearly FIT (72% and 76%, respectively), every 10 year colonoscopy (79% and 81%, respectively), and triennial mt-sDNA (68% and 73%, respectively). The BBT resulted in fewer quality-adjusted life-years per person compared to the alternatives.

Additionally, FIT, colonoscopy, and mt-sDNA were less costly and more effective. Advanced precancerous lesion detection was a key measure for a test’s effectiveness. BBT characteristics would require a CRC sensitivity and specificity of >90% and 90%, respectively, and 80% sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions at a cost of ≤$120–$140 to be cost-effective compared to FIT at comparable participation rates.

Another analysis simulated colorectal neoplasia progression and compared clinical effectiveness and cost between annual FIT, every 3 year stool mt-sRNA, every 3 year stool mt-sDNA tests, every 3 year stool Shield™; these outcomes were compared to colonoscopy every 10 years and no screening in adults ≥ age 45 over different adherence rates.19 At real-world adherence rates of 60%, colonoscopy prevented most CRC cases and associated deaths. FIT was the most cost-effective strategy at all adherence levels. Between the multi-target stool tests and Shield™, mt-sRNA was the most cost-effective. Compared to FIT, mt-sRNA reduced CRC cases and deaths by 1% and 14%.

The third study evaluated CRC incidence and mortality, quality-adjusted life-years and costs with annual FIT, colonoscopy every 10 years, mt- sDNA tests, mt-sRNA test, and BBTs.20 The latest mt-sDNA (Colguard plus™) and mt-sRNA achieved benefits approaching FIT but the Shield™ test was substantially less effective. The authors hypothesized that if 15% of the population substituted Shield™ for current effective CRC screening strategies, an increase in CRC deaths would occur and require 9-10% of the unscreened population to uptake screening with Shield to avert the increases in CRC deaths due to the substitution effect.

Clinical Implications

The effectiveness of non-invasive screening strategies depends on their diagnostic performance, adherence, and ensuring a timely colonoscopy after a positive test. Two claims-based studies found 47.9% and 49% of patients underwent follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months of an abnormal stool or BBT CRC screening test, respectively.21-22

Conclusions

Non-invasive stool mt-sDNA and mt-sRNA have higher effectiveness than the new BBTs. BBTs can lead to increased CRC mortality if substituted for the FDA and CMS-approved, USPSTF-endorsed, CRC screening modalities. If future BBTs increase their sensitivity for CRC (including early-stage CRC) and advanced precancerous lesions and decrease their cost, they may prove to have similar cost-effectiveness to stool-based tests. Currently, BBTs are not a substitute for colonoscopy or other stool tests and should be offered to patients who refuse other CRC screening modalities. A personalized, risk-adapted approach, paired with improved adherence and follow-up are essential to optimize the population-level impact of CRC screening and ensure equitable, effective cancer prevention.

Dr. Gupta is based at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Dr. Burke and Dr. Macaron are based at the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Macaron declared no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Burke declared research support from Emtora Biosciences. She is a current consultant for Lumabridge, and has been a consultant for Sebela and Almirall. She also disclosed support from Myriad, Genzyme, Ferring, Merck, Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Salix, and Natera.

References

1. Benavidez GA, Sedani AE, Felder TM, Asare M, Rogers CR. Rural-urban disparities and trends in cancer screening: an analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data (2018-2022). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Nov 1;8(6):pkae113

2. Galoosian A, Dai H, Croymans D, et al. Population Health Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies in Adults Aged 45 to 49 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Aug 4:e2512049. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.12049. Epub ahead of print.

3. Pilonis ND, Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, et al. Participation in Competing Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Health Services Study (PICCOLINO Study). Gastroenterology. 2021 Mar;160(4):1097-1105.

4. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–1114.

5. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. PMID: 8942774.

6. Burke CA, Lieberman D, Feuerstein JD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Approach to the Use of Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Options: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):952-956. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.075. Epub 2022 Jan 28. PMID: 35094786.

7. Imperiale TF, Gruber RN Stump TE, et al. Performance characteristics of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170(5):319-329

8. Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Screening and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Death. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2423671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23671.

9. Chiu HM, Jen GH, Wang YW, et al. Long-term effectiveness of faecal immunochemical test screening for proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Gut. 2021 Dec;70(12):2321-2329. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322545. Epub 2021 Jan 25.

10. Castells A, Quintero E, Bujanda L, et al; COLONPREV study investigators. Effect of invitation to colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test screening on colorectal cancer mortality (COLONPREV): a pragmatic, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2025;405(10486):1231–1239

11. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297

12. Imperiale TF, Porter K, Zella J, et al. Next-Generation Multitarget Stool DNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):984-993

13. Barnell EK, Wurtzler EM, La Rocca J, et al. Multitarget Stool RNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. JAMA. 2023 Nov 14;330(18):1760-1768.

14. Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2014; 63:317–325.

15. Chung DC, Gray DM 2nd, Singh H, et al. A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):973-983.

16. Shaukat A, Burke CA, Chan AT, et al. Clinical Validation of a Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Blood Test to Screen for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA. 2025 Jul 1;334(1):56-63.

17. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Weng Y, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening with Blood-Based Biomarkers (Liquid Biopsy) vs Fecal Tests or Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2024 Jul;167(2):378-391.

18. van den Puttelaar R, Nascimento de Lima P, Knudsen AB, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with a blood test that meets the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services coverage decision. Gastroenterology 2024;167:368–377.

19. Shaukat A, Levin TR, Liang PS. Cost-effectiveness of Novel Noninvasive Screening Tests for Colorectal Neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jun 23:S1542-3565(25)00525-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40562290.

20. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Schoen RE, Dominitz JA, Lieberman D. Projected Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Novel Molecular Blood-Based or Stool-Based Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Dec;177(12):1610-1620.

20. Ciemins EL, Mohl JT, Moreno CA, Colangelo F, Smith RA, Barton M. Development of a Follow-Up Measure to Ensure Complete Screening for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e242693. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2693.

21. Zaki TA, Zhang NJ, Forbes SP, Raymond VM, Das AK, May FP. Colonoscopic Follow-up After Abnormal Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Results. Gastroenterology. 2025 Jul 21:S0016-5085(25)05775-0. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.07.019. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40744392.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Use in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: A Review of Current Evidence and Guidelines

The use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) has increased over the past several years and has become a cornerstone in both diabetes and weight loss management, particularly because of its unique combination of glucose control, weight reduction potential, and cardiac and metabolic benefits. However, increased use of these agents presents a dilemma in gastrointestinal endoscopy as it pertains to their safety and management during the periprocedural period.

highlighting gaps and future directions.

Pharmacology and Mechanisms of Action

GLP-1 RAs have several mechanisms of action that make them relevant in gastrointestinal endoscopy. These medications modulate glucose control via enhancement of glucose-dependent insulin secretion and reduction of postprandial glucagon, which promotes satiety and delays gastric emptying. This delay in gastric emptying mediated by vagal pathways has been postulated to increase gastric residuals, posing a risk for aspiration during anesthesia.1

It is important to also consider the pharmacokinetics of GLP-1 RAs, as some have shorter half-lives on the order of several hours, like exenatide, while others, like semaglutide, are dosed weekly. Additionally, common side effects of GLP-1 RAs include nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety, which pose challenges for patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.

Current Guidelines

Various societies have published guidelines on the periprocedural use of GLP-1 RAs. The American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) in 2023 presented early recommendations to hold GLP-1 RAs either day of procedure or week prior depending on pharmacokinetics, because of the risk of delayed gastric emptying and increased potential for aspiration.2 Soon thereafter, a multi-gastroenterology society guideline was released stating more data is needed to decide if GLP-1 RAs need to be held prior to endoscopic procedures.3

In early 2024, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) published a rapid clinical update that advocated for a more individualized approach, particularly in light of limited overall data for GLP-1 RAs and endoscopic procedures.4 In asymptomatic patients who follow typical fasting protocols for procedures, it is generally safe to proceed with endoscopy without holding GLP-1 RAs. In symptomatic patients (nausea, abdominal distension, etc), the AGA advises additional precautions, including performing transabdominal ultrasound if feasible to assess retained gastric contents. The AGA also suggests placing a patient on a clear liquid diet the day prior to the procedure — rather than holding GLP-1 RAs — as another reasonable strategy.

The guidelines continue to evolve with newer multi-society guidelines establishing best practices. While initially in 2023 the ASA did recommend holding these medications prior to endoscopy, the initial guidance was based on expert opinion with limited evidence. Newer multi-society guidance published jointly by the ASA along with various gastroenterology societies, including the AGA in December 2024, takes a more nuanced approach.5

The newer guidelines include two main recommendations:

1. Periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs should be a joint decision among the procedural, anesthesia, and prescribing team balancing metabolic needs vs patient risks.

- In a low-risk patient, one that is asymptomatic and on standard dosing, among other factors, the guidance states that GLP-1 RAs can be continued.

- In higher-risk patients, the original guidance of holding a day or a week prior to endoscopic procedures should be followed.

2. Periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs should attempt to minimize the aspiration risks loosely associated with delayed gastric emptying.

- Consider a 24-hour clear liquid diet a day prior to the procedure and transabdominal ultrasound to check gastric contents.

- It is acknowledged that this guidance is based on limited evidence and will be evolving as new medications and data are released.

Recent Clinical Studies

Although there is very little data to guide clinicians, several recent studies have been published that can direct clinical decision-making as guidelines continue to be refined and updated.

A multicenter trial of approximately 800 patients undergoing upper endoscopy found a significant difference in rates of retained gastric contents between those that underwent endoscopy who did and did not follow the ASA guidance on periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs (12.7% vs 4.4%; P < .0001). However, there were no significant differences in rates of aborted procedures or unplanned intubations.

Furthermore, a multivariable analysis was performed controlling for GLP-1 RA type and other factors, which found the likelihood of gastric retention increased by 36% for every 1% increase in hemoglobin A1c. This study suggests that a more individualized approach to holding GLP-1 RA would be applicable rather than a universal periprocedural hold.6

More recently, a single-center study of nearly 600 patients undergoing upper endoscopy showed that while there were slightly increased rates of retained gastric contents (OR 3.80; P = .003) and aborted procedures (1.3% vs 0%; P = .02), the rates of adverse anesthesia events (hypoxia, etc) were similar between the groups and no cases of pulmonary aspiration were noted.7

One single-center study of 57 patients evaluated the safety of GLP-1 RAs in those undergoing endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. GLP-1 RAs were continued on all patients, but all adhered to a liquid only diet for at least 24 hours prior to the procedure. There were no instances of retained gastric solids, aspiration, or hypoxia. This study suggests that with a 24-hour clear liquid diet and routine NPO recommendations prior to endoscopy, it would be safe to continue GLP-1 RAs. This study provides rationale for the AGA recommendation for a clear liquid diet 24 hours prior to endoscopic procedures for those on GLP-1 RAs.8

A study looking at those who underwent emergency surgery and endoscopy with claims data of use of GLP-1 RAs found an overall incidence of postoperative respiratory complications of 3.5% for those with GLP-1 RAs fill history vs 4.0% for those without (P = .12). Approximately 800 of the 24,000 patients identified had undergone endoscopic procedures for GI bleeding or food impaction. The study overall showed that preoperative use of GLP-1 RAs in patients undergoing surgery or endoscopy, evaluated as a combined group, was not associated with an increased risk of pulmonary complications.9

Lastly, a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 15 studies that quantified gastric emptying using various methods, including gastric emptying scintigraphy and acetaminophen absorption test, found that there was a quantifiable delay in gastric emptying of about 36 minutes, compared to placebo (P < .01), in patients using GLP-1 RAs. However, compared to standard periprocedural fasting, this delay is clinically insignificant and standard fasting protocols would still be appropriate for patients on GLP-1 RAs.10

These studies taken together suggest that while GLP-1 RAs can mildly increase the likelihood of retained gastric contents, there is no statistically significant increase in the risk of aspiration or other anesthesia complications. Furthermore, while decreased gastric emptying is a known effect of GLP-1 RAs, this effect may not be clinically significant in the context of standard periprocedural fasting protocols particularly when combined with a 24-hour clear liquid diet. These findings support at a minimum a more patient-specific strategy for periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs.

Clinical Implications

These most recent studies, as well as prior studies and guidelines by various societies lead to a dilemma among endoscopists on proper patient counseling on GLP-1 RAs use before endoscopic procedures. Clinicians must balance the metabolic benefits of GLP-1 RAs with potential endoscopic complications and risks.

Holding therapy theoretically decreases aspiration risk and pulmonary complications, though evidence remains low to support this. Holding medication, however, affects glycemic control leading to potential rebound hyperglycemia which may impact and delay plans for endoscopy. With growing indications for the use of GLP-1 RAs, a more tailored patient-centered treatment plan may be required, especially with consideration of procedure indication and comorbidities.

Currently, practice patterns at different institutions vary widely, making standardization much more difficult. Some centers have opted to follow ASA guidelines of holding these medications up to 1 week prior to procedures, while others have continued therapy with no pre-procedural adjustments. This leaves endoscopists to deal with the downstream effects of inconvenience to patients, care delays, and financial considerations if procedures are postponed related to GLP-1 RAs use.

Future Directions

Future studies are needed to make further evidence-based recommendations. Studies should focus on stratifying risks and recommendations based on procedure type (EGD, colonoscopy, etc). More widespread implementation of gastric ultrasound can assist in real-time decision-making, albeit this would require expertise and dedicated time within the pre-procedural workflow. Randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes of patients who continue GLP-1 RAs vs those who discontinue stratified by baseline risk will be instrumental for making concrete guidelines that provide clarity on periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs.

Conclusion

The periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs remains a controversial topic that presents unique challenges in endoscopy. Several guidelines have been released by various stakeholders including anesthesiologists, gastroenterologists, and other prescribing providers. Clinical data remains limited with no robust evidence available to suggest that gastric emptying delays caused by GLP-1 RAs prior to endoscopic procedures significantly increases risk of aspiration, pulmonary complications, or other comorbidities. Evolving multi-society guidelines will be important to establish more consistent practices with reassessment of the data as new studies emerge. A multidisciplinary, individualized patient approach may be the best strategy for managing GLP-1 RAs for patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.

Dr. Sekar and Dr. Asamoah are based in the department of gastroenterology at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, D.C. Dr. Sekar reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Asamoah serves on the Johnson & Johnson advisory board for inflammatory bowel disease–related therapies.

References

1. Halim MA et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Inhibits Prandial Gastrointestinal Motility Through Myenteric Neuronal Mechanisms in Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-02006.

2. American Society of Anesthesiologists. American Society of Anesthesiologists releases consensus-based guidance on preoperative use of GLP-1 receptor agonists. 2023 Jun 20. www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2023/06/american-society-of-anesthesiologists-consensus-based-guidance-on-preoperative

3. American Gastroenterological Association. GI multi-society statement regarding GLP-1 agonists and endoscopy. 2023 Jul 25. gastro.org/news/gi-multi-society-statement-regarding-glp-1-agonists-and-endoscopy/.

4. Hashash JG et al. AGA Rapid Clinical Practice Update on the Management of Patients Taking GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Prior to Endoscopy: Communication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.11.002.

5. Kindel TL et al; American Gastroenterological Association; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery; American Society of Anesthesiologists; International Society of Perioperative Care of Patients with Obesity; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Multi-society Clinical Practice Guidance for the Safe Use of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in the Perioperative Period. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.10.003.

6. Phan J et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide Receptor Agonists Use Before Endoscopy Is Associated With Low Retained Gastric Contents: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025 Mar. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002969.

7. Panchal S et al. Endoscopy and Anesthesia Outcomes Associated With Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist use in Patients Undergoing Outpatient Upper Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2025 Aug. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2025.01.004.

8. Maselli DB et al. Safe Continuation of glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists at Endoscopy: A Case Series of 57 Adults Undergoing Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024 Jul. doi: 10.1007/s11695-024-07278-2.

9. Dixit AA et al. Preoperative GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Risk of Postoperative Respiratory Complications. JAMA. 2024 Apr. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.5003.

10. Hiramoto B et al. Quantified Metrics of Gastric Emptying Delay by Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Agonists: A systematic review and meta-analysis with insights for periprocedural management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002820.

The use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) has increased over the past several years and has become a cornerstone in both diabetes and weight loss management, particularly because of its unique combination of glucose control, weight reduction potential, and cardiac and metabolic benefits. However, increased use of these agents presents a dilemma in gastrointestinal endoscopy as it pertains to their safety and management during the periprocedural period.

highlighting gaps and future directions.

Pharmacology and Mechanisms of Action

GLP-1 RAs have several mechanisms of action that make them relevant in gastrointestinal endoscopy. These medications modulate glucose control via enhancement of glucose-dependent insulin secretion and reduction of postprandial glucagon, which promotes satiety and delays gastric emptying. This delay in gastric emptying mediated by vagal pathways has been postulated to increase gastric residuals, posing a risk for aspiration during anesthesia.1

It is important to also consider the pharmacokinetics of GLP-1 RAs, as some have shorter half-lives on the order of several hours, like exenatide, while others, like semaglutide, are dosed weekly. Additionally, common side effects of GLP-1 RAs include nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety, which pose challenges for patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.

Current Guidelines

Various societies have published guidelines on the periprocedural use of GLP-1 RAs. The American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) in 2023 presented early recommendations to hold GLP-1 RAs either day of procedure or week prior depending on pharmacokinetics, because of the risk of delayed gastric emptying and increased potential for aspiration.2 Soon thereafter, a multi-gastroenterology society guideline was released stating more data is needed to decide if GLP-1 RAs need to be held prior to endoscopic procedures.3

In early 2024, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) published a rapid clinical update that advocated for a more individualized approach, particularly in light of limited overall data for GLP-1 RAs and endoscopic procedures.4 In asymptomatic patients who follow typical fasting protocols for procedures, it is generally safe to proceed with endoscopy without holding GLP-1 RAs. In symptomatic patients (nausea, abdominal distension, etc), the AGA advises additional precautions, including performing transabdominal ultrasound if feasible to assess retained gastric contents. The AGA also suggests placing a patient on a clear liquid diet the day prior to the procedure — rather than holding GLP-1 RAs — as another reasonable strategy.

The guidelines continue to evolve with newer multi-society guidelines establishing best practices. While initially in 2023 the ASA did recommend holding these medications prior to endoscopy, the initial guidance was based on expert opinion with limited evidence. Newer multi-society guidance published jointly by the ASA along with various gastroenterology societies, including the AGA in December 2024, takes a more nuanced approach.5

The newer guidelines include two main recommendations:

1. Periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs should be a joint decision among the procedural, anesthesia, and prescribing team balancing metabolic needs vs patient risks.

- In a low-risk patient, one that is asymptomatic and on standard dosing, among other factors, the guidance states that GLP-1 RAs can be continued.

- In higher-risk patients, the original guidance of holding a day or a week prior to endoscopic procedures should be followed.

2. Periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs should attempt to minimize the aspiration risks loosely associated with delayed gastric emptying.

- Consider a 24-hour clear liquid diet a day prior to the procedure and transabdominal ultrasound to check gastric contents.

- It is acknowledged that this guidance is based on limited evidence and will be evolving as new medications and data are released.

Recent Clinical Studies

Although there is very little data to guide clinicians, several recent studies have been published that can direct clinical decision-making as guidelines continue to be refined and updated.

A multicenter trial of approximately 800 patients undergoing upper endoscopy found a significant difference in rates of retained gastric contents between those that underwent endoscopy who did and did not follow the ASA guidance on periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs (12.7% vs 4.4%; P < .0001). However, there were no significant differences in rates of aborted procedures or unplanned intubations.

Furthermore, a multivariable analysis was performed controlling for GLP-1 RA type and other factors, which found the likelihood of gastric retention increased by 36% for every 1% increase in hemoglobin A1c. This study suggests that a more individualized approach to holding GLP-1 RA would be applicable rather than a universal periprocedural hold.6

More recently, a single-center study of nearly 600 patients undergoing upper endoscopy showed that while there were slightly increased rates of retained gastric contents (OR 3.80; P = .003) and aborted procedures (1.3% vs 0%; P = .02), the rates of adverse anesthesia events (hypoxia, etc) were similar between the groups and no cases of pulmonary aspiration were noted.7

One single-center study of 57 patients evaluated the safety of GLP-1 RAs in those undergoing endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. GLP-1 RAs were continued on all patients, but all adhered to a liquid only diet for at least 24 hours prior to the procedure. There were no instances of retained gastric solids, aspiration, or hypoxia. This study suggests that with a 24-hour clear liquid diet and routine NPO recommendations prior to endoscopy, it would be safe to continue GLP-1 RAs. This study provides rationale for the AGA recommendation for a clear liquid diet 24 hours prior to endoscopic procedures for those on GLP-1 RAs.8

A study looking at those who underwent emergency surgery and endoscopy with claims data of use of GLP-1 RAs found an overall incidence of postoperative respiratory complications of 3.5% for those with GLP-1 RAs fill history vs 4.0% for those without (P = .12). Approximately 800 of the 24,000 patients identified had undergone endoscopic procedures for GI bleeding or food impaction. The study overall showed that preoperative use of GLP-1 RAs in patients undergoing surgery or endoscopy, evaluated as a combined group, was not associated with an increased risk of pulmonary complications.9

Lastly, a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 15 studies that quantified gastric emptying using various methods, including gastric emptying scintigraphy and acetaminophen absorption test, found that there was a quantifiable delay in gastric emptying of about 36 minutes, compared to placebo (P < .01), in patients using GLP-1 RAs. However, compared to standard periprocedural fasting, this delay is clinically insignificant and standard fasting protocols would still be appropriate for patients on GLP-1 RAs.10

These studies taken together suggest that while GLP-1 RAs can mildly increase the likelihood of retained gastric contents, there is no statistically significant increase in the risk of aspiration or other anesthesia complications. Furthermore, while decreased gastric emptying is a known effect of GLP-1 RAs, this effect may not be clinically significant in the context of standard periprocedural fasting protocols particularly when combined with a 24-hour clear liquid diet. These findings support at a minimum a more patient-specific strategy for periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs.

Clinical Implications

These most recent studies, as well as prior studies and guidelines by various societies lead to a dilemma among endoscopists on proper patient counseling on GLP-1 RAs use before endoscopic procedures. Clinicians must balance the metabolic benefits of GLP-1 RAs with potential endoscopic complications and risks.

Holding therapy theoretically decreases aspiration risk and pulmonary complications, though evidence remains low to support this. Holding medication, however, affects glycemic control leading to potential rebound hyperglycemia which may impact and delay plans for endoscopy. With growing indications for the use of GLP-1 RAs, a more tailored patient-centered treatment plan may be required, especially with consideration of procedure indication and comorbidities.

Currently, practice patterns at different institutions vary widely, making standardization much more difficult. Some centers have opted to follow ASA guidelines of holding these medications up to 1 week prior to procedures, while others have continued therapy with no pre-procedural adjustments. This leaves endoscopists to deal with the downstream effects of inconvenience to patients, care delays, and financial considerations if procedures are postponed related to GLP-1 RAs use.

Future Directions

Future studies are needed to make further evidence-based recommendations. Studies should focus on stratifying risks and recommendations based on procedure type (EGD, colonoscopy, etc). More widespread implementation of gastric ultrasound can assist in real-time decision-making, albeit this would require expertise and dedicated time within the pre-procedural workflow. Randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes of patients who continue GLP-1 RAs vs those who discontinue stratified by baseline risk will be instrumental for making concrete guidelines that provide clarity on periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs.

Conclusion

The periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs remains a controversial topic that presents unique challenges in endoscopy. Several guidelines have been released by various stakeholders including anesthesiologists, gastroenterologists, and other prescribing providers. Clinical data remains limited with no robust evidence available to suggest that gastric emptying delays caused by GLP-1 RAs prior to endoscopic procedures significantly increases risk of aspiration, pulmonary complications, or other comorbidities. Evolving multi-society guidelines will be important to establish more consistent practices with reassessment of the data as new studies emerge. A multidisciplinary, individualized patient approach may be the best strategy for managing GLP-1 RAs for patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.

Dr. Sekar and Dr. Asamoah are based in the department of gastroenterology at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, D.C. Dr. Sekar reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Asamoah serves on the Johnson & Johnson advisory board for inflammatory bowel disease–related therapies.

References

1. Halim MA et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Inhibits Prandial Gastrointestinal Motility Through Myenteric Neuronal Mechanisms in Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-02006.

2. American Society of Anesthesiologists. American Society of Anesthesiologists releases consensus-based guidance on preoperative use of GLP-1 receptor agonists. 2023 Jun 20. www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2023/06/american-society-of-anesthesiologists-consensus-based-guidance-on-preoperative

3. American Gastroenterological Association. GI multi-society statement regarding GLP-1 agonists and endoscopy. 2023 Jul 25. gastro.org/news/gi-multi-society-statement-regarding-glp-1-agonists-and-endoscopy/.

4. Hashash JG et al. AGA Rapid Clinical Practice Update on the Management of Patients Taking GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Prior to Endoscopy: Communication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.11.002.

5. Kindel TL et al; American Gastroenterological Association; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery; American Society of Anesthesiologists; International Society of Perioperative Care of Patients with Obesity; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Multi-society Clinical Practice Guidance for the Safe Use of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in the Perioperative Period. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.10.003.

6. Phan J et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide Receptor Agonists Use Before Endoscopy Is Associated With Low Retained Gastric Contents: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025 Mar. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002969.

7. Panchal S et al. Endoscopy and Anesthesia Outcomes Associated With Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist use in Patients Undergoing Outpatient Upper Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2025 Aug. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2025.01.004.

8. Maselli DB et al. Safe Continuation of glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists at Endoscopy: A Case Series of 57 Adults Undergoing Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024 Jul. doi: 10.1007/s11695-024-07278-2.

9. Dixit AA et al. Preoperative GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Risk of Postoperative Respiratory Complications. JAMA. 2024 Apr. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.5003.

10. Hiramoto B et al. Quantified Metrics of Gastric Emptying Delay by Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Agonists: A systematic review and meta-analysis with insights for periprocedural management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002820.

The use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) has increased over the past several years and has become a cornerstone in both diabetes and weight loss management, particularly because of its unique combination of glucose control, weight reduction potential, and cardiac and metabolic benefits. However, increased use of these agents presents a dilemma in gastrointestinal endoscopy as it pertains to their safety and management during the periprocedural period.

highlighting gaps and future directions.

Pharmacology and Mechanisms of Action

GLP-1 RAs have several mechanisms of action that make them relevant in gastrointestinal endoscopy. These medications modulate glucose control via enhancement of glucose-dependent insulin secretion and reduction of postprandial glucagon, which promotes satiety and delays gastric emptying. This delay in gastric emptying mediated by vagal pathways has been postulated to increase gastric residuals, posing a risk for aspiration during anesthesia.1

It is important to also consider the pharmacokinetics of GLP-1 RAs, as some have shorter half-lives on the order of several hours, like exenatide, while others, like semaglutide, are dosed weekly. Additionally, common side effects of GLP-1 RAs include nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety, which pose challenges for patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.

Current Guidelines

Various societies have published guidelines on the periprocedural use of GLP-1 RAs. The American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) in 2023 presented early recommendations to hold GLP-1 RAs either day of procedure or week prior depending on pharmacokinetics, because of the risk of delayed gastric emptying and increased potential for aspiration.2 Soon thereafter, a multi-gastroenterology society guideline was released stating more data is needed to decide if GLP-1 RAs need to be held prior to endoscopic procedures.3

In early 2024, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) published a rapid clinical update that advocated for a more individualized approach, particularly in light of limited overall data for GLP-1 RAs and endoscopic procedures.4 In asymptomatic patients who follow typical fasting protocols for procedures, it is generally safe to proceed with endoscopy without holding GLP-1 RAs. In symptomatic patients (nausea, abdominal distension, etc), the AGA advises additional precautions, including performing transabdominal ultrasound if feasible to assess retained gastric contents. The AGA also suggests placing a patient on a clear liquid diet the day prior to the procedure — rather than holding GLP-1 RAs — as another reasonable strategy.

The guidelines continue to evolve with newer multi-society guidelines establishing best practices. While initially in 2023 the ASA did recommend holding these medications prior to endoscopy, the initial guidance was based on expert opinion with limited evidence. Newer multi-society guidance published jointly by the ASA along with various gastroenterology societies, including the AGA in December 2024, takes a more nuanced approach.5

The newer guidelines include two main recommendations:

1. Periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs should be a joint decision among the procedural, anesthesia, and prescribing team balancing metabolic needs vs patient risks.

- In a low-risk patient, one that is asymptomatic and on standard dosing, among other factors, the guidance states that GLP-1 RAs can be continued.

- In higher-risk patients, the original guidance of holding a day or a week prior to endoscopic procedures should be followed.

2. Periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs should attempt to minimize the aspiration risks loosely associated with delayed gastric emptying.

- Consider a 24-hour clear liquid diet a day prior to the procedure and transabdominal ultrasound to check gastric contents.

- It is acknowledged that this guidance is based on limited evidence and will be evolving as new medications and data are released.

Recent Clinical Studies

Although there is very little data to guide clinicians, several recent studies have been published that can direct clinical decision-making as guidelines continue to be refined and updated.

A multicenter trial of approximately 800 patients undergoing upper endoscopy found a significant difference in rates of retained gastric contents between those that underwent endoscopy who did and did not follow the ASA guidance on periprocedural management of GLP-1 RAs (12.7% vs 4.4%; P < .0001). However, there were no significant differences in rates of aborted procedures or unplanned intubations.

Furthermore, a multivariable analysis was performed controlling for GLP-1 RA type and other factors, which found the likelihood of gastric retention increased by 36% for every 1% increase in hemoglobin A1c. This study suggests that a more individualized approach to holding GLP-1 RA would be applicable rather than a universal periprocedural hold.6

More recently, a single-center study of nearly 600 patients undergoing upper endoscopy showed that while there were slightly increased rates of retained gastric contents (OR 3.80; P = .003) and aborted procedures (1.3% vs 0%; P = .02), the rates of adverse anesthesia events (hypoxia, etc) were similar between the groups and no cases of pulmonary aspiration were noted.7