User login

Improving Care for Patients from Historically Minoritized and Marginalized Communities with Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

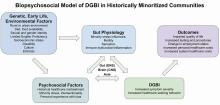

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

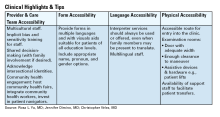

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

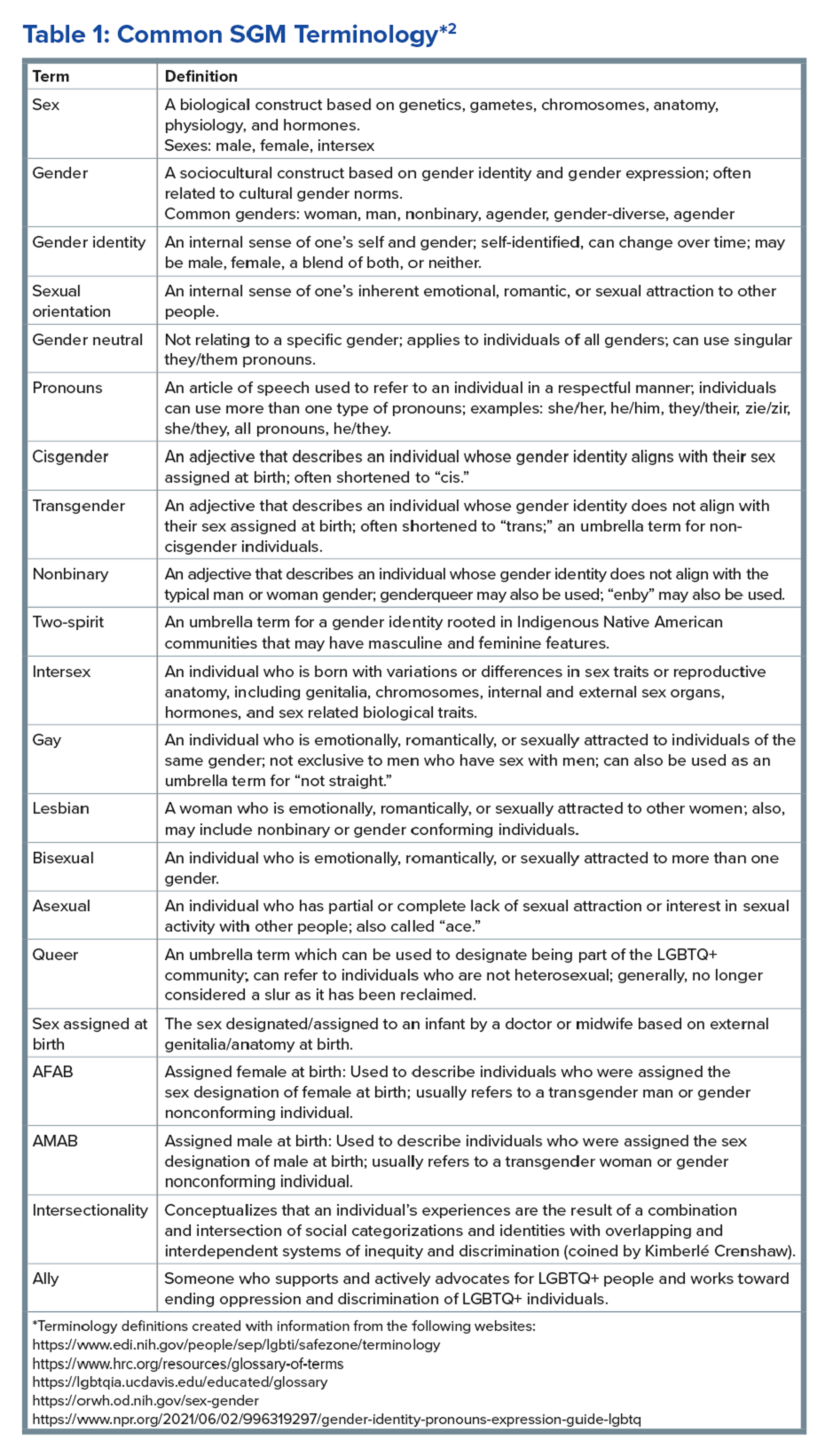

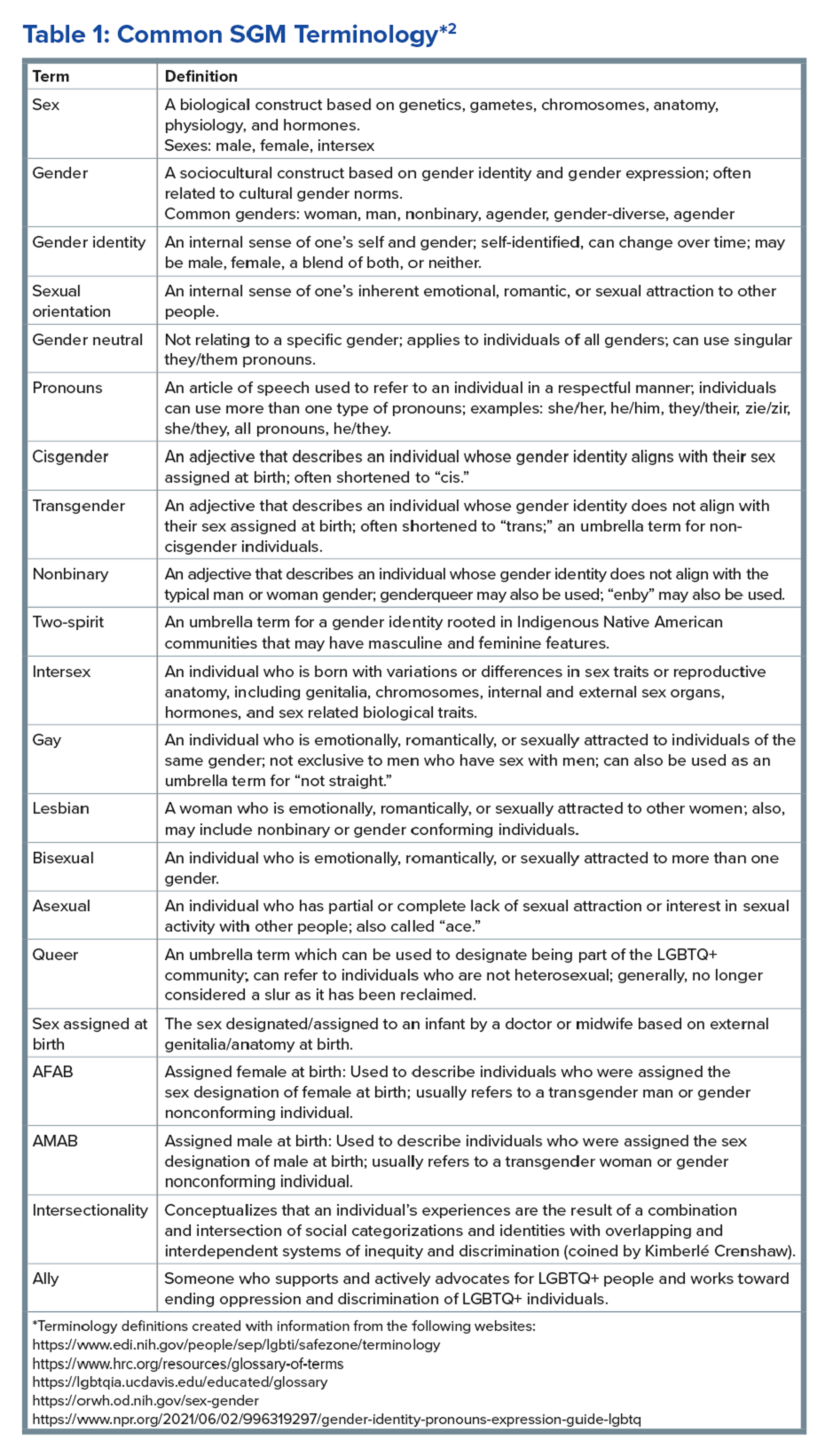

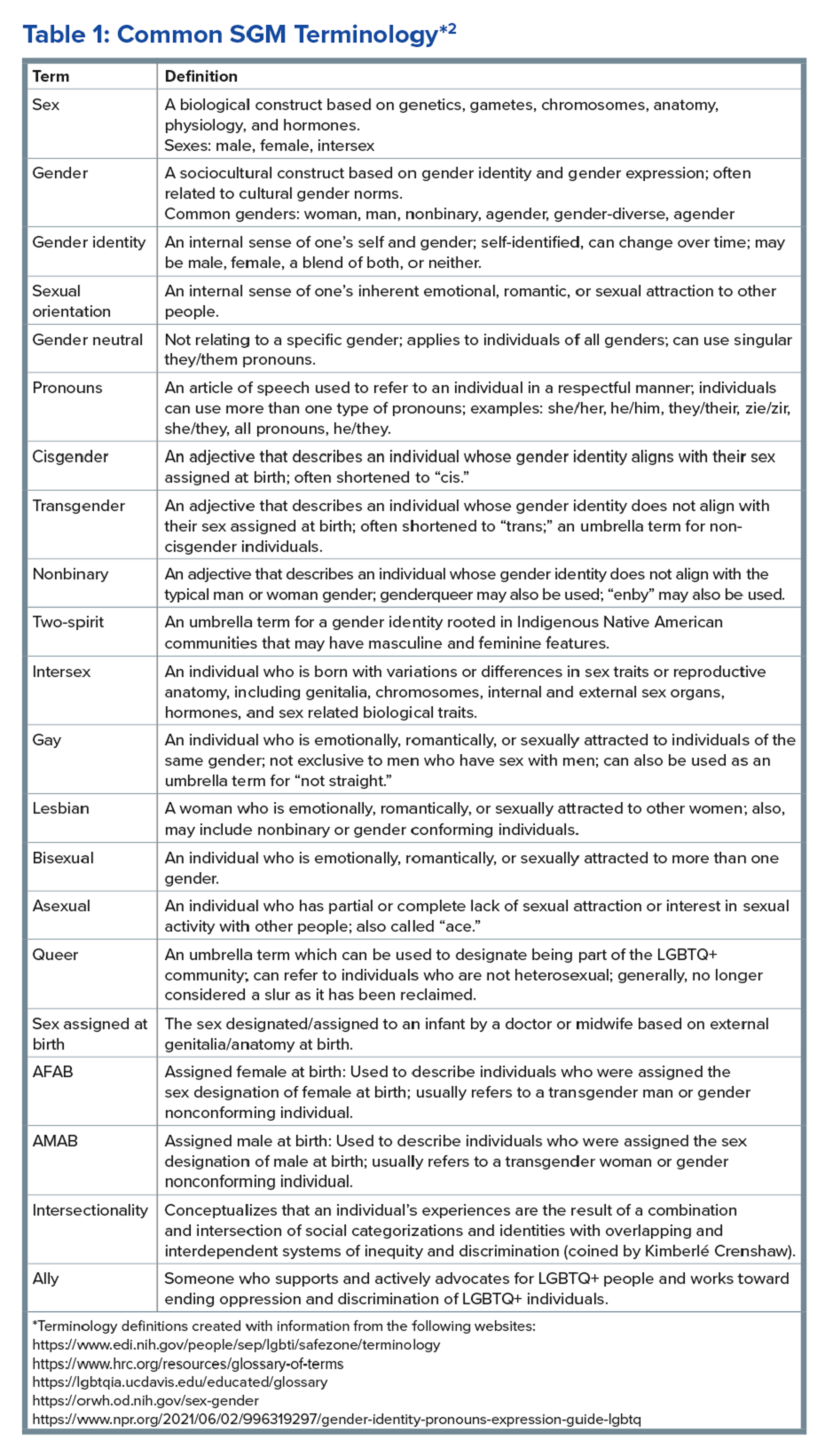

Improving Care for Sexual and Gender Minority Patients with Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction

Brief Introduction to the SGM Communities

The sexual and gender minority (SGM) communities (see Table 1), also termed “LGBTQIA+ community” (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, plus — including two spirit) are historically minoritized with unique risks for inequities in gastrointestinal health outcomes.1 These potential disparities remain largely uninvestigated because of continued systemic discrimination and inadequate collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data,2 with the National Institutes of Health Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office (SGMRO) having been instructed to address these failures. There is increased SGM self-identification (7.1% of all people in the United States and 20.8% of generation Z).3 Given the high worldwide prevalence of disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs)and the influence of biopsychosocial determinants of health in DGBI incidence,4 it becomes increasingly likely that research in DGBI-related factors in SGM people will be fruitful.

Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction and the Potential Minority Stress Link in SGM People

DGBIs are gastrointestinal conditions that occur because of brain-gut axis dysregulation. There is evidence that chronic stress and trauma negatively influence brain-gut interaction, which likely results in minority communities who face increased levels of trauma, stress, discrimination, and social injustice being at higher risk of DGBI development.5-7 Given increased rates of trauma in the SGM community, practicing trauma-informed care is essential to increase patient comfort and decrease the chance of retraumatization in medical settings.8 Trauma-informed care focuses on how trauma influences a patient’s life and response to medical care. To practice trauma-informed care, screening for trauma when appropriate, actively creating a supportive environment with active listening and communication, with informing the patient of planned actions prior to doing them, like physical exams, is key.

Trauma-Informed Care: Examples of Verbiage

Asking about Identity

- Begin by introducing yourself with your pronouns to create a safe environment for patient disclosure. Example: “Hello, I am Dr. Kara Jencks, and my pronouns are she/her. I am one of the gastroenterologists here at XYZ Clinic. How would you prefer to be addressed?”

- You can also wear a pronoun lapel pin or a pronoun button on your ID badge to indicate you are someone who your patient can be themselves around.

- The easiest way to obtain sexual orientation and gender identity is through intake forms. Below are examples of how to ask these questions on intake forms. It is important to offer the option to select more than one option when applicable and to opt out of answering if the patient is not comfortable answering these questions.

Sample Questions for Intake Forms

1. What is your sex assigned at birth? (Select one)

- Female

- Male

- Intersex

- Do not know

- Prefer not to disclose

2. What is your gender identity? (Select all that apply)

- Nonbinary

- Gender queer

- Woman

- Man

- Transwoman

- Transman

- Gender fluid

- Two-spirit

- Agender

- Intersex

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

3. What are your pronouns? (Select all that apply)

- They/them/theirs

- She/her/hers

- He/him/his

- Zie/zir/zirs

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

4. What is your sexual orientation? (Select all that apply)

- Bisexual

- Pansexual

- Queer

- Lesbian

- Gay

- Asexual

- Demisexual

- Heterosexual or straight

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

Screening for Trauma

While there are questionnaires that exist to ask about trauma history, if time allows, it can be helpful to screen verbally with the patient. See reference number 8, for additional prompts and actions to practice trauma-informed care.

- Example: “Many patients with gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders have experienced trauma in the past. We do our best to ensure we are keeping you as comfortable as possible while caring for you. Are you comfortable sharing this information? [if yes->] Do you have a history of trauma, including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse? ... Have these experiences impacted the way in which you navigate your healthcare? ... Is there anything we can do to make you more comfortable today?”

General Physical Examination

Provide details for what you are going to do before you do it. Ask for permission for the examination. Here are two examples:

- “I would like to perform a physical exam to help better understand your symptoms. Is that okay with you?”

- “I would like to examine your abdomen with my stethoscope and my hands. Here is a sheet that we can use to help with your privacy. Please let me know if and when you feel any tenderness or pain.”

Rectal Physical Examination

Let the patient know why it would be helpful to perform a rectal exam, what the rectal exam will entail, and the benefits and risks to doing a rectal exam. An example follows:

- “Based on the symptoms you are describing, I think it would be helpful to perform a rectal exam to make sure you don’t have any fissures or hemorrhoids on the outside around the anus, any blockages or major issues inside the rectum, and to assess the strength and ability of your nerves and muscles or the pelvic floor to coordinate bowel movements. There are no risks aside from discomfort. If it is painful, and you would like me to stop, you tell me to stop, and I will stop right away. What questions do you have? Are we okay to proceed with the rectal exam?”

- “Please pull down your undergarments and your pants to either midthigh, your ankles, or all the way off, whatever your preference is, lie down on the left side on the exam table, and cover yourself with this sheet. In the meantime, I will be getting a chaperone to keep us safe and serve as a patient advocate during the procedure.”

- Upon returning to the exam room: “Here is Sara, who will be chaperoning today. Let myself or Sara know if you are uncomfortable or having pain during this exam. I will be lifting up the sheet to get a good look around the anus. [lifts up sheet] You will feel my hand helping to spread apart the buttocks. I am looking around the anus, and I do not see any fissures, hemorrhoids, or anything else concerning. Please squeeze in like you are trying to hold in gas. Please bear down like you are trying to have a bowel movement or let out gas. Okay, now you may feel some cold gel around the anus, and you will feel my finger go inside. Take a deep breath in. Do you feel any pain as I palpate? Please squeeze in like you are trying to hold in gas. Please bear down like you are trying to have a bowel movement or let out gas. I will be stopping the exam now.”

- You would then wash your hands and allow the patient to get dressed, and then disclose the exam findings and the rest of your visit.

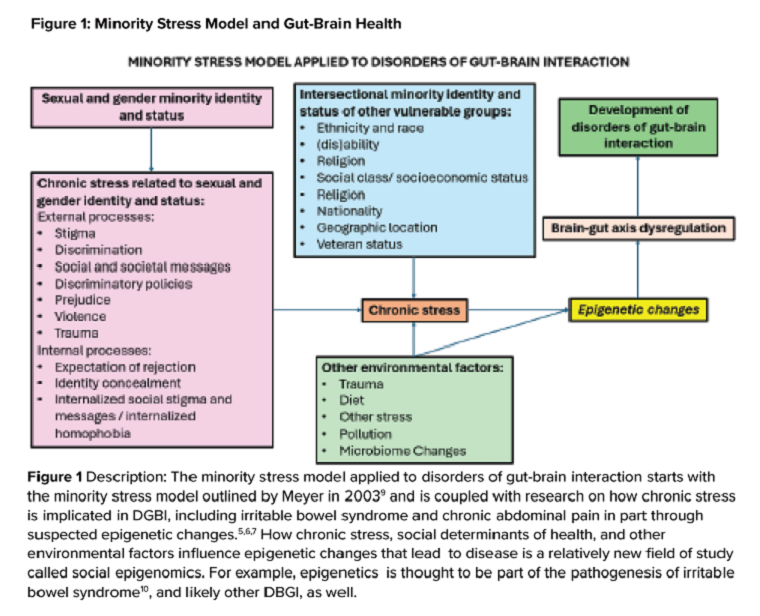

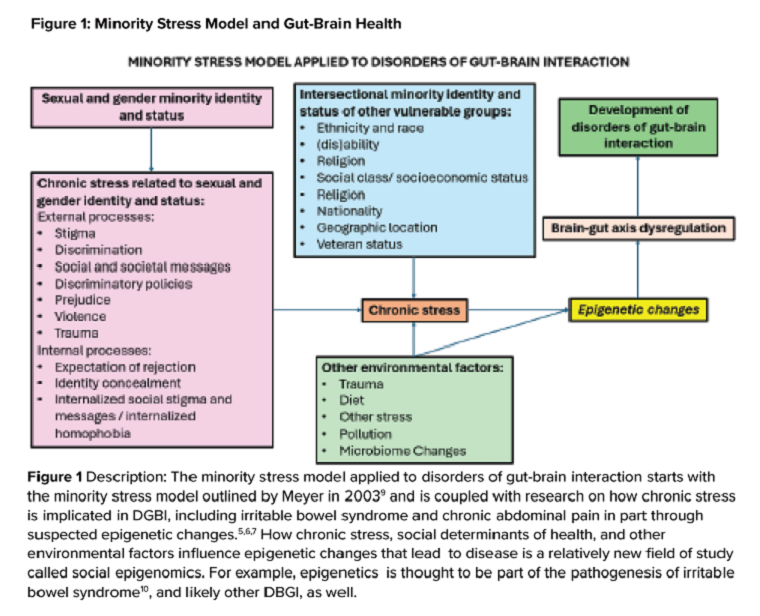

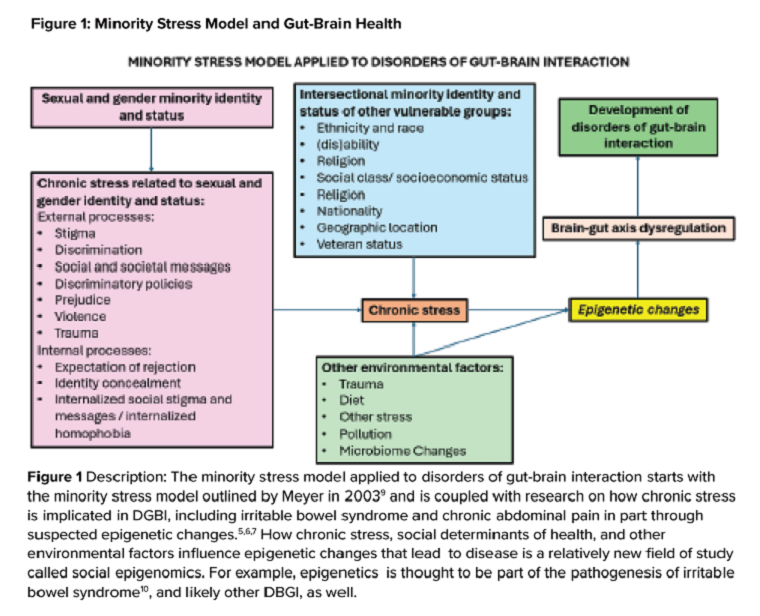

Ilan H. Meyer coined the minority stress model when discussing mental health disorders in SGM patients in the early 2000s.9 With it being well known that DGBIs can overlap with (but are not necessarily caused by) mental health disorders, this model can easily apply to unify multiple individual and societal factors that can combine to result in disorders of brain-gut interaction (see Figure 1) in SGM communities. Let us keep this framework in mind when evaluating the following cases.

Case Presentations

Case 1

A 56-year-old man (pronouns: he/him) assigned male sex at birth, who identifies as gay, presents to your gastroenterology clinic for treatment-refractory constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. It has impacted his sexual function. Outside hospital records report a normal colonoscopy 1 year ago and an unremarkable abdominal computerized tomography 4 months ago, aside from increased stool burden in the entire colon. He has tried to use enemas prior to sex, though these do not always help. Fiber-rich diet and fermentable food avoidance has not been successful. He is currently taking two capfuls of polyethylene glycol 3350 twice per day, as well as senna at night and continues to have a bowel movement every 2-3 days that is Bristol stool form scale type 1-2 unless he uses enemas. How do you counsel this patient about his IBS-C and rectal discomfort?

After assessing for sexual violence or other potential trauma-related factors, your digital rectal examination suggests that an anorectal defecatory disorder is less likely with normal relaxation and perineal movement. You recommend linaclotide. He notices improvement within 1 week, with improved comfort during anoreceptive sex.

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman (pronouns: she/her) assigned male sex at birth who has sex with men underwent vaginoplasty 2 years ago and is referred to the gastroenterology clinic for fecal incontinence and diarrhea. On review of her anatomic inventory, her vaginoplasty was a penile inversion vaginoplasty (no intestinal tissue was used for creation), and her prostate was left intact. The vaginal vault was created in between the urethra and rectum, similar to the pelvic floor anatomy of a woman assigned female sex at birth. Blood, imaging, and endoscopic workup has been negative. She is also not taking any medications associated with diarrhea, only taking estrogen and spironolactone. The diarrhea is not daily, but when present, about once per week, can be up to 10 episodes per day, and she has a sense of incomplete evacuation regularly. She notes having a rectal exam in the past but is not sure if her pelvic floor muscles have ever been assessed. How do you manage this patient?

To complete her evaluation in the office, you perform a trauma-informed rectal exam which reveals a decreased resting anal sphincter tone and paradoxical defecatory maneuvers without tenderness to the puborectalis muscle. Augmentation of the squeeze is also weak. Given her pelvic floor related surgical history, her symptoms, and her rectal exam, you recommend anorectal manometry which is abnormal and send her for anorectal biofeedback pelvic floor physical therapy, which improves her symptoms significantly.

Case 3

A 36-year-old woman (pronouns: she/her) assigned female sex at birth, who identifies as a lesbian, has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic nausea and vomiting that has begun to affect her quality of life. She notes the nausea and vomiting used to be managed well with evening cannabis gummies, though in the past 3 months, the nausea and vomiting has worsened, and she has lost 20 pounds as a result. As symptom predated cannabis usage, cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was less likely (an important point as she has been stigmatized during prior encounters for her cannabis usage). Her primary care physician recommended a gastroscopy which was normal, aside from some residual solid food material in the stomach. Her bowel movements are normal, and she doesn’t have other gastrointestinal symptoms. She and her wife are considering having a third child, so she is worried about medications that may affect pregnancy or breast-feeding. How do you manage her nausea and vomiting?

After validating her concerns and performing a trauma-informed physical exam and encounter, you recommend a 4-hour gastric emptying test with a standard radiolabeled egg meal. Her gastric emptying does reveal significantly delayed gastric emptying at 2 and 4 hours. You discuss the risks and benefits of lifestyle modification (smaller frequent meals), initiating medications (erythromycin and metoclopramide) or cessation of cannabis (despite low likelihood of CHS). Desiring to avoid starting medications around initiation of pregnancy, she opts for the dietary approach and cessation of cannabis. You see her at a follow-up visit in 6 months, and her nausea is now only once a month, and she is excited to begin planning for a pregnancy using assisted reproductive technology.

Case 4

A 20-year-old nonbinary intersex individual (pronouns: he/they) (incorrectly assigned female at birth — is intersex with congenital adrenal hyperplasia) presents to the gastroenterology clinic with 8 years of heartburn, acid reflux, postprandial bloating, alternating diarrhea and constipation, nausea, and vomiting, complicated by avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. They have a history of bipolar II disorder with prior suicidal ideation. He has not yet had diagnostic workup as he previously had a bad encounter with a gastroenterologist where the gastroenterologist blamed his symptoms on his gender-affirming therapy, misgendered the patient, and told the patient their symptoms were “all in her [sic] head.”

You recognize that affirming their gender and using proper pronouns is the best first way to start rapport and help break the cycle of medicalized trauma. You then recommend a holistic work up with interdisciplinary management because of the complexity of his symptoms. For testing, you recommend a colonoscopy, upper endoscopy, a gastric emptying test with a 48-hour transit scintigraphy test, anorectal manometry, a dietitian referral, and a gastrointestinal psychology referral. Their anorectal manometry is consistent with an evacuation disorder. The rest of the work up is unremarkable. You diagnose them with anorectal pelvic floor dysfunction and functional dyspepsia, recommending biofeedback pelvic floor physical therapy, a proton-pump inhibitor, and neuromodulation in coordination with psychiatry and psychology to start with a plan for follow-up. The patient appreciates you for helping them and listening to their symptoms.

Discussion

When approaching DGBIs in the SGM community, it is vital to validate their concerns and be inclusive with diagnostic and treatment modalities. The diagnostic tools and treatments for DGBI are not different for patients in the SGM community. Like with other patients, trauma-informed care should be utilized, particularly given higher rates of trauma and discrimination in this community. Importantly, their DGBI is not a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity, and hormone therapy is not the cause of their DGBI. Recommending cessation of gender-affirming care or recommending lifestyle measures against their identity is generally not appropriate or necessary. among members of the SGM communities.

Dr. Jencks (@karajencks) is based in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Vélez (@Chris_Velez_MD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Both authors do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

References

1. Duong N et al. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00005-5.

2. Vélez C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001804.

3. Jones JM. Gallup. LGBTQ+ identification in U.S. now at 7.6%. 2024 Mar 13. https://news.gallup.com/poll/611864/lgbtq-identification.aspx

4. Sperber AD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014.

5. Wiley JW et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12706.

6. Labanski A et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104501.

7. Khlevner J et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2018.07.002.

8. Jagielski CH and Harer KN. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2022.07.012.

9. Meyer IH. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

10. Mahurkar-Joshi S and Chang L. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00805.

Brief Introduction to the SGM Communities

The sexual and gender minority (SGM) communities (see Table 1), also termed “LGBTQIA+ community” (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, plus — including two spirit) are historically minoritized with unique risks for inequities in gastrointestinal health outcomes.1 These potential disparities remain largely uninvestigated because of continued systemic discrimination and inadequate collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data,2 with the National Institutes of Health Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office (SGMRO) having been instructed to address these failures. There is increased SGM self-identification (7.1% of all people in the United States and 20.8% of generation Z).3 Given the high worldwide prevalence of disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs)and the influence of biopsychosocial determinants of health in DGBI incidence,4 it becomes increasingly likely that research in DGBI-related factors in SGM people will be fruitful.

Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction and the Potential Minority Stress Link in SGM People

DGBIs are gastrointestinal conditions that occur because of brain-gut axis dysregulation. There is evidence that chronic stress and trauma negatively influence brain-gut interaction, which likely results in minority communities who face increased levels of trauma, stress, discrimination, and social injustice being at higher risk of DGBI development.5-7 Given increased rates of trauma in the SGM community, practicing trauma-informed care is essential to increase patient comfort and decrease the chance of retraumatization in medical settings.8 Trauma-informed care focuses on how trauma influences a patient’s life and response to medical care. To practice trauma-informed care, screening for trauma when appropriate, actively creating a supportive environment with active listening and communication, with informing the patient of planned actions prior to doing them, like physical exams, is key.

Trauma-Informed Care: Examples of Verbiage

Asking about Identity

- Begin by introducing yourself with your pronouns to create a safe environment for patient disclosure. Example: “Hello, I am Dr. Kara Jencks, and my pronouns are she/her. I am one of the gastroenterologists here at XYZ Clinic. How would you prefer to be addressed?”

- You can also wear a pronoun lapel pin or a pronoun button on your ID badge to indicate you are someone who your patient can be themselves around.

- The easiest way to obtain sexual orientation and gender identity is through intake forms. Below are examples of how to ask these questions on intake forms. It is important to offer the option to select more than one option when applicable and to opt out of answering if the patient is not comfortable answering these questions.

Sample Questions for Intake Forms

1. What is your sex assigned at birth? (Select one)

- Female

- Male

- Intersex

- Do not know

- Prefer not to disclose

2. What is your gender identity? (Select all that apply)

- Nonbinary

- Gender queer

- Woman

- Man

- Transwoman

- Transman

- Gender fluid

- Two-spirit

- Agender

- Intersex

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

3. What are your pronouns? (Select all that apply)

- They/them/theirs

- She/her/hers

- He/him/his

- Zie/zir/zirs

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

4. What is your sexual orientation? (Select all that apply)

- Bisexual

- Pansexual

- Queer

- Lesbian

- Gay

- Asexual

- Demisexual

- Heterosexual or straight

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

Screening for Trauma

While there are questionnaires that exist to ask about trauma history, if time allows, it can be helpful to screen verbally with the patient. See reference number 8, for additional prompts and actions to practice trauma-informed care.

- Example: “Many patients with gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders have experienced trauma in the past. We do our best to ensure we are keeping you as comfortable as possible while caring for you. Are you comfortable sharing this information? [if yes->] Do you have a history of trauma, including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse? ... Have these experiences impacted the way in which you navigate your healthcare? ... Is there anything we can do to make you more comfortable today?”

General Physical Examination

Provide details for what you are going to do before you do it. Ask for permission for the examination. Here are two examples:

- “I would like to perform a physical exam to help better understand your symptoms. Is that okay with you?”

- “I would like to examine your abdomen with my stethoscope and my hands. Here is a sheet that we can use to help with your privacy. Please let me know if and when you feel any tenderness or pain.”

Rectal Physical Examination

Let the patient know why it would be helpful to perform a rectal exam, what the rectal exam will entail, and the benefits and risks to doing a rectal exam. An example follows:

- “Based on the symptoms you are describing, I think it would be helpful to perform a rectal exam to make sure you don’t have any fissures or hemorrhoids on the outside around the anus, any blockages or major issues inside the rectum, and to assess the strength and ability of your nerves and muscles or the pelvic floor to coordinate bowel movements. There are no risks aside from discomfort. If it is painful, and you would like me to stop, you tell me to stop, and I will stop right away. What questions do you have? Are we okay to proceed with the rectal exam?”

- “Please pull down your undergarments and your pants to either midthigh, your ankles, or all the way off, whatever your preference is, lie down on the left side on the exam table, and cover yourself with this sheet. In the meantime, I will be getting a chaperone to keep us safe and serve as a patient advocate during the procedure.”

- Upon returning to the exam room: “Here is Sara, who will be chaperoning today. Let myself or Sara know if you are uncomfortable or having pain during this exam. I will be lifting up the sheet to get a good look around the anus. [lifts up sheet] You will feel my hand helping to spread apart the buttocks. I am looking around the anus, and I do not see any fissures, hemorrhoids, or anything else concerning. Please squeeze in like you are trying to hold in gas. Please bear down like you are trying to have a bowel movement or let out gas. Okay, now you may feel some cold gel around the anus, and you will feel my finger go inside. Take a deep breath in. Do you feel any pain as I palpate? Please squeeze in like you are trying to hold in gas. Please bear down like you are trying to have a bowel movement or let out gas. I will be stopping the exam now.”

- You would then wash your hands and allow the patient to get dressed, and then disclose the exam findings and the rest of your visit.

Ilan H. Meyer coined the minority stress model when discussing mental health disorders in SGM patients in the early 2000s.9 With it being well known that DGBIs can overlap with (but are not necessarily caused by) mental health disorders, this model can easily apply to unify multiple individual and societal factors that can combine to result in disorders of brain-gut interaction (see Figure 1) in SGM communities. Let us keep this framework in mind when evaluating the following cases.

Case Presentations

Case 1

A 56-year-old man (pronouns: he/him) assigned male sex at birth, who identifies as gay, presents to your gastroenterology clinic for treatment-refractory constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. It has impacted his sexual function. Outside hospital records report a normal colonoscopy 1 year ago and an unremarkable abdominal computerized tomography 4 months ago, aside from increased stool burden in the entire colon. He has tried to use enemas prior to sex, though these do not always help. Fiber-rich diet and fermentable food avoidance has not been successful. He is currently taking two capfuls of polyethylene glycol 3350 twice per day, as well as senna at night and continues to have a bowel movement every 2-3 days that is Bristol stool form scale type 1-2 unless he uses enemas. How do you counsel this patient about his IBS-C and rectal discomfort?

After assessing for sexual violence or other potential trauma-related factors, your digital rectal examination suggests that an anorectal defecatory disorder is less likely with normal relaxation and perineal movement. You recommend linaclotide. He notices improvement within 1 week, with improved comfort during anoreceptive sex.

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman (pronouns: she/her) assigned male sex at birth who has sex with men underwent vaginoplasty 2 years ago and is referred to the gastroenterology clinic for fecal incontinence and diarrhea. On review of her anatomic inventory, her vaginoplasty was a penile inversion vaginoplasty (no intestinal tissue was used for creation), and her prostate was left intact. The vaginal vault was created in between the urethra and rectum, similar to the pelvic floor anatomy of a woman assigned female sex at birth. Blood, imaging, and endoscopic workup has been negative. She is also not taking any medications associated with diarrhea, only taking estrogen and spironolactone. The diarrhea is not daily, but when present, about once per week, can be up to 10 episodes per day, and she has a sense of incomplete evacuation regularly. She notes having a rectal exam in the past but is not sure if her pelvic floor muscles have ever been assessed. How do you manage this patient?

To complete her evaluation in the office, you perform a trauma-informed rectal exam which reveals a decreased resting anal sphincter tone and paradoxical defecatory maneuvers without tenderness to the puborectalis muscle. Augmentation of the squeeze is also weak. Given her pelvic floor related surgical history, her symptoms, and her rectal exam, you recommend anorectal manometry which is abnormal and send her for anorectal biofeedback pelvic floor physical therapy, which improves her symptoms significantly.

Case 3

A 36-year-old woman (pronouns: she/her) assigned female sex at birth, who identifies as a lesbian, has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic nausea and vomiting that has begun to affect her quality of life. She notes the nausea and vomiting used to be managed well with evening cannabis gummies, though in the past 3 months, the nausea and vomiting has worsened, and she has lost 20 pounds as a result. As symptom predated cannabis usage, cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was less likely (an important point as she has been stigmatized during prior encounters for her cannabis usage). Her primary care physician recommended a gastroscopy which was normal, aside from some residual solid food material in the stomach. Her bowel movements are normal, and she doesn’t have other gastrointestinal symptoms. She and her wife are considering having a third child, so she is worried about medications that may affect pregnancy or breast-feeding. How do you manage her nausea and vomiting?

After validating her concerns and performing a trauma-informed physical exam and encounter, you recommend a 4-hour gastric emptying test with a standard radiolabeled egg meal. Her gastric emptying does reveal significantly delayed gastric emptying at 2 and 4 hours. You discuss the risks and benefits of lifestyle modification (smaller frequent meals), initiating medications (erythromycin and metoclopramide) or cessation of cannabis (despite low likelihood of CHS). Desiring to avoid starting medications around initiation of pregnancy, she opts for the dietary approach and cessation of cannabis. You see her at a follow-up visit in 6 months, and her nausea is now only once a month, and she is excited to begin planning for a pregnancy using assisted reproductive technology.

Case 4

A 20-year-old nonbinary intersex individual (pronouns: he/they) (incorrectly assigned female at birth — is intersex with congenital adrenal hyperplasia) presents to the gastroenterology clinic with 8 years of heartburn, acid reflux, postprandial bloating, alternating diarrhea and constipation, nausea, and vomiting, complicated by avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. They have a history of bipolar II disorder with prior suicidal ideation. He has not yet had diagnostic workup as he previously had a bad encounter with a gastroenterologist where the gastroenterologist blamed his symptoms on his gender-affirming therapy, misgendered the patient, and told the patient their symptoms were “all in her [sic] head.”

You recognize that affirming their gender and using proper pronouns is the best first way to start rapport and help break the cycle of medicalized trauma. You then recommend a holistic work up with interdisciplinary management because of the complexity of his symptoms. For testing, you recommend a colonoscopy, upper endoscopy, a gastric emptying test with a 48-hour transit scintigraphy test, anorectal manometry, a dietitian referral, and a gastrointestinal psychology referral. Their anorectal manometry is consistent with an evacuation disorder. The rest of the work up is unremarkable. You diagnose them with anorectal pelvic floor dysfunction and functional dyspepsia, recommending biofeedback pelvic floor physical therapy, a proton-pump inhibitor, and neuromodulation in coordination with psychiatry and psychology to start with a plan for follow-up. The patient appreciates you for helping them and listening to their symptoms.

Discussion

When approaching DGBIs in the SGM community, it is vital to validate their concerns and be inclusive with diagnostic and treatment modalities. The diagnostic tools and treatments for DGBI are not different for patients in the SGM community. Like with other patients, trauma-informed care should be utilized, particularly given higher rates of trauma and discrimination in this community. Importantly, their DGBI is not a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity, and hormone therapy is not the cause of their DGBI. Recommending cessation of gender-affirming care or recommending lifestyle measures against their identity is generally not appropriate or necessary. among members of the SGM communities.

Dr. Jencks (@karajencks) is based in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Vélez (@Chris_Velez_MD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Both authors do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

References

1. Duong N et al. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00005-5.

2. Vélez C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001804.

3. Jones JM. Gallup. LGBTQ+ identification in U.S. now at 7.6%. 2024 Mar 13. https://news.gallup.com/poll/611864/lgbtq-identification.aspx

4. Sperber AD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014.

5. Wiley JW et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12706.

6. Labanski A et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104501.

7. Khlevner J et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2018.07.002.

8. Jagielski CH and Harer KN. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2022.07.012.

9. Meyer IH. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

10. Mahurkar-Joshi S and Chang L. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00805.

Brief Introduction to the SGM Communities

The sexual and gender minority (SGM) communities (see Table 1), also termed “LGBTQIA+ community” (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, plus — including two spirit) are historically minoritized with unique risks for inequities in gastrointestinal health outcomes.1 These potential disparities remain largely uninvestigated because of continued systemic discrimination and inadequate collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data,2 with the National Institutes of Health Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office (SGMRO) having been instructed to address these failures. There is increased SGM self-identification (7.1% of all people in the United States and 20.8% of generation Z).3 Given the high worldwide prevalence of disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs)and the influence of biopsychosocial determinants of health in DGBI incidence,4 it becomes increasingly likely that research in DGBI-related factors in SGM people will be fruitful.

Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction and the Potential Minority Stress Link in SGM People

DGBIs are gastrointestinal conditions that occur because of brain-gut axis dysregulation. There is evidence that chronic stress and trauma negatively influence brain-gut interaction, which likely results in minority communities who face increased levels of trauma, stress, discrimination, and social injustice being at higher risk of DGBI development.5-7 Given increased rates of trauma in the SGM community, practicing trauma-informed care is essential to increase patient comfort and decrease the chance of retraumatization in medical settings.8 Trauma-informed care focuses on how trauma influences a patient’s life and response to medical care. To practice trauma-informed care, screening for trauma when appropriate, actively creating a supportive environment with active listening and communication, with informing the patient of planned actions prior to doing them, like physical exams, is key.

Trauma-Informed Care: Examples of Verbiage

Asking about Identity

- Begin by introducing yourself with your pronouns to create a safe environment for patient disclosure. Example: “Hello, I am Dr. Kara Jencks, and my pronouns are she/her. I am one of the gastroenterologists here at XYZ Clinic. How would you prefer to be addressed?”

- You can also wear a pronoun lapel pin or a pronoun button on your ID badge to indicate you are someone who your patient can be themselves around.

- The easiest way to obtain sexual orientation and gender identity is through intake forms. Below are examples of how to ask these questions on intake forms. It is important to offer the option to select more than one option when applicable and to opt out of answering if the patient is not comfortable answering these questions.

Sample Questions for Intake Forms

1. What is your sex assigned at birth? (Select one)

- Female

- Male

- Intersex

- Do not know

- Prefer not to disclose

2. What is your gender identity? (Select all that apply)

- Nonbinary

- Gender queer

- Woman

- Man

- Transwoman

- Transman

- Gender fluid

- Two-spirit

- Agender

- Intersex

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

3. What are your pronouns? (Select all that apply)

- They/them/theirs

- She/her/hers

- He/him/his

- Zie/zir/zirs

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

4. What is your sexual orientation? (Select all that apply)

- Bisexual

- Pansexual

- Queer

- Lesbian

- Gay

- Asexual

- Demisexual

- Heterosexual or straight

- Other: type in response

- Prefer not to disclose

Screening for Trauma

While there are questionnaires that exist to ask about trauma history, if time allows, it can be helpful to screen verbally with the patient. See reference number 8, for additional prompts and actions to practice trauma-informed care.

- Example: “Many patients with gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders have experienced trauma in the past. We do our best to ensure we are keeping you as comfortable as possible while caring for you. Are you comfortable sharing this information? [if yes->] Do you have a history of trauma, including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse? ... Have these experiences impacted the way in which you navigate your healthcare? ... Is there anything we can do to make you more comfortable today?”

General Physical Examination

Provide details for what you are going to do before you do it. Ask for permission for the examination. Here are two examples:

- “I would like to perform a physical exam to help better understand your symptoms. Is that okay with you?”

- “I would like to examine your abdomen with my stethoscope and my hands. Here is a sheet that we can use to help with your privacy. Please let me know if and when you feel any tenderness or pain.”

Rectal Physical Examination

Let the patient know why it would be helpful to perform a rectal exam, what the rectal exam will entail, and the benefits and risks to doing a rectal exam. An example follows:

- “Based on the symptoms you are describing, I think it would be helpful to perform a rectal exam to make sure you don’t have any fissures or hemorrhoids on the outside around the anus, any blockages or major issues inside the rectum, and to assess the strength and ability of your nerves and muscles or the pelvic floor to coordinate bowel movements. There are no risks aside from discomfort. If it is painful, and you would like me to stop, you tell me to stop, and I will stop right away. What questions do you have? Are we okay to proceed with the rectal exam?”

- “Please pull down your undergarments and your pants to either midthigh, your ankles, or all the way off, whatever your preference is, lie down on the left side on the exam table, and cover yourself with this sheet. In the meantime, I will be getting a chaperone to keep us safe and serve as a patient advocate during the procedure.”

- Upon returning to the exam room: “Here is Sara, who will be chaperoning today. Let myself or Sara know if you are uncomfortable or having pain during this exam. I will be lifting up the sheet to get a good look around the anus. [lifts up sheet] You will feel my hand helping to spread apart the buttocks. I am looking around the anus, and I do not see any fissures, hemorrhoids, or anything else concerning. Please squeeze in like you are trying to hold in gas. Please bear down like you are trying to have a bowel movement or let out gas. Okay, now you may feel some cold gel around the anus, and you will feel my finger go inside. Take a deep breath in. Do you feel any pain as I palpate? Please squeeze in like you are trying to hold in gas. Please bear down like you are trying to have a bowel movement or let out gas. I will be stopping the exam now.”

- You would then wash your hands and allow the patient to get dressed, and then disclose the exam findings and the rest of your visit.

Ilan H. Meyer coined the minority stress model when discussing mental health disorders in SGM patients in the early 2000s.9 With it being well known that DGBIs can overlap with (but are not necessarily caused by) mental health disorders, this model can easily apply to unify multiple individual and societal factors that can combine to result in disorders of brain-gut interaction (see Figure 1) in SGM communities. Let us keep this framework in mind when evaluating the following cases.

Case Presentations

Case 1

A 56-year-old man (pronouns: he/him) assigned male sex at birth, who identifies as gay, presents to your gastroenterology clinic for treatment-refractory constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. It has impacted his sexual function. Outside hospital records report a normal colonoscopy 1 year ago and an unremarkable abdominal computerized tomography 4 months ago, aside from increased stool burden in the entire colon. He has tried to use enemas prior to sex, though these do not always help. Fiber-rich diet and fermentable food avoidance has not been successful. He is currently taking two capfuls of polyethylene glycol 3350 twice per day, as well as senna at night and continues to have a bowel movement every 2-3 days that is Bristol stool form scale type 1-2 unless he uses enemas. How do you counsel this patient about his IBS-C and rectal discomfort?

After assessing for sexual violence or other potential trauma-related factors, your digital rectal examination suggests that an anorectal defecatory disorder is less likely with normal relaxation and perineal movement. You recommend linaclotide. He notices improvement within 1 week, with improved comfort during anoreceptive sex.

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman (pronouns: she/her) assigned male sex at birth who has sex with men underwent vaginoplasty 2 years ago and is referred to the gastroenterology clinic for fecal incontinence and diarrhea. On review of her anatomic inventory, her vaginoplasty was a penile inversion vaginoplasty (no intestinal tissue was used for creation), and her prostate was left intact. The vaginal vault was created in between the urethra and rectum, similar to the pelvic floor anatomy of a woman assigned female sex at birth. Blood, imaging, and endoscopic workup has been negative. She is also not taking any medications associated with diarrhea, only taking estrogen and spironolactone. The diarrhea is not daily, but when present, about once per week, can be up to 10 episodes per day, and she has a sense of incomplete evacuation regularly. She notes having a rectal exam in the past but is not sure if her pelvic floor muscles have ever been assessed. How do you manage this patient?

To complete her evaluation in the office, you perform a trauma-informed rectal exam which reveals a decreased resting anal sphincter tone and paradoxical defecatory maneuvers without tenderness to the puborectalis muscle. Augmentation of the squeeze is also weak. Given her pelvic floor related surgical history, her symptoms, and her rectal exam, you recommend anorectal manometry which is abnormal and send her for anorectal biofeedback pelvic floor physical therapy, which improves her symptoms significantly.

Case 3