User login

Legal duty to nonpatients: Driving accidents

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.

The case is currently on appeal. The AMA has filed an amicus brief in support of Dr. Lerner,1 pointing out that third-party claims had previously been rejected in New Jersey, where the injured victim is not readily identifiable. The brief emphasizes the folly of placing the physician or therapist in the untenable position of serving two potentially competing interests when a physician’s priority should be providing care to the patient. It referenced a similar case in Kansas, where a motorist who had fallen asleep at the wheel struck a bicyclist. The motorist was being treated by a neurologist for a sleep disorder.2 The Kansas Supreme Court held that there was no special relationship between the doctor and the cyclist that would impose a duty to warn the motorist about harming a third party.

Other jurisdictions have likewise rejected attempts at “derivative duties” in automobile accident cases. The Connecticut Supreme Court has ruled3 that doctors are immune from third party traffic accident lawsuits, as such litigation would detract from what’s best for the patient (“a physician’s desire to avoid lawsuits may result in far more restrictive advice than necessary for the patient’s well-being”). In that case, the defendant-gastroenterologist, Dr. Troncale, was treating a patient with hepatic encephalopathy and had not warned of the associated risk of driving. And an Illinois court dismissed a third party’s case against a hospital when one of its physicians fell asleep at the wheel after working excessive hours.4

In contrast, other jurisdictions have found a legal duty for physicians toward nonpatient victims. For example, in McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group,5 a car suddenly veered across five lanes of traffic, striking an 11-year-old girl and crushing her against a cement planter. The driver alleged that the prescription medication, Prazosin, caused him to lose control of the car, and that the treating physician was negligent, first in prescribing an inappropriate type and dose of medication, and second in failing to warn of potential side effects that could affect driving ability. The Hawaii Supreme Court emphasized that the risk of tort liability to an individual physician already discourages negligent prescribing; therefore, a physician does not have a duty to third parties where the alleged negligence involves prescribing decisions, i.e., whether to prescribe medication at all, which medication to prescribe, and what dosage to use. On the other hand, physicians have a duty to their patients to warn of potential adverse effects and this responsibility should therefore extend to third parties. Thus, liability would attach to injuries of innocent third parties as a result of failing to warn of a medication’s effects on driving—unless a reasonable person could be expected to be aware of this risk without the warning.

A foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm is an important but not the only decisive factor in construing the existence of legal duty. Under some circumstances, the term “special relationship” has been employed based on a consideration of existing social values, customs, and policy considerations. In a Massachusetts case,6 a family physician had failed to warn his patient of the risk of diabetes drugs when operating a vehicle. Some 45 minutes after the patient’s discharge from the hospital, he developed hypoglycemia, losing consciousness and injuring a motorcyclist who then sued the doctor. The court invoked the “special relationship” rationale in ruling that the doctor owed a duty to the motorcyclist for public policy reasons.

Dr. Tan is professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera, In the Superior Court of New Jersey Appellate Division, Docket No. A-001255-18T3.

2. Calwell v. Hassan, 925 P.2d 422, 430 (Kan. 1996).

3. Jarmie v. Troncale, 50 A.3d 802 (Conn. 2012).

4. Brewster v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Med. Ctr., 836 N.E.2d 635 (Ill. Ct. App. 2005).

5. McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group, 47 P.3d 1209 (Haw. 2002).

6. Arsenault v. McConarty, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 500 (2006).

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.

The case is currently on appeal. The AMA has filed an amicus brief in support of Dr. Lerner,1 pointing out that third-party claims had previously been rejected in New Jersey, where the injured victim is not readily identifiable. The brief emphasizes the folly of placing the physician or therapist in the untenable position of serving two potentially competing interests when a physician’s priority should be providing care to the patient. It referenced a similar case in Kansas, where a motorist who had fallen asleep at the wheel struck a bicyclist. The motorist was being treated by a neurologist for a sleep disorder.2 The Kansas Supreme Court held that there was no special relationship between the doctor and the cyclist that would impose a duty to warn the motorist about harming a third party.

Other jurisdictions have likewise rejected attempts at “derivative duties” in automobile accident cases. The Connecticut Supreme Court has ruled3 that doctors are immune from third party traffic accident lawsuits, as such litigation would detract from what’s best for the patient (“a physician’s desire to avoid lawsuits may result in far more restrictive advice than necessary for the patient’s well-being”). In that case, the defendant-gastroenterologist, Dr. Troncale, was treating a patient with hepatic encephalopathy and had not warned of the associated risk of driving. And an Illinois court dismissed a third party’s case against a hospital when one of its physicians fell asleep at the wheel after working excessive hours.4

In contrast, other jurisdictions have found a legal duty for physicians toward nonpatient victims. For example, in McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group,5 a car suddenly veered across five lanes of traffic, striking an 11-year-old girl and crushing her against a cement planter. The driver alleged that the prescription medication, Prazosin, caused him to lose control of the car, and that the treating physician was negligent, first in prescribing an inappropriate type and dose of medication, and second in failing to warn of potential side effects that could affect driving ability. The Hawaii Supreme Court emphasized that the risk of tort liability to an individual physician already discourages negligent prescribing; therefore, a physician does not have a duty to third parties where the alleged negligence involves prescribing decisions, i.e., whether to prescribe medication at all, which medication to prescribe, and what dosage to use. On the other hand, physicians have a duty to their patients to warn of potential adverse effects and this responsibility should therefore extend to third parties. Thus, liability would attach to injuries of innocent third parties as a result of failing to warn of a medication’s effects on driving—unless a reasonable person could be expected to be aware of this risk without the warning.

A foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm is an important but not the only decisive factor in construing the existence of legal duty. Under some circumstances, the term “special relationship” has been employed based on a consideration of existing social values, customs, and policy considerations. In a Massachusetts case,6 a family physician had failed to warn his patient of the risk of diabetes drugs when operating a vehicle. Some 45 minutes after the patient’s discharge from the hospital, he developed hypoglycemia, losing consciousness and injuring a motorcyclist who then sued the doctor. The court invoked the “special relationship” rationale in ruling that the doctor owed a duty to the motorcyclist for public policy reasons.

Dr. Tan is professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera, In the Superior Court of New Jersey Appellate Division, Docket No. A-001255-18T3.

2. Calwell v. Hassan, 925 P.2d 422, 430 (Kan. 1996).

3. Jarmie v. Troncale, 50 A.3d 802 (Conn. 2012).

4. Brewster v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Med. Ctr., 836 N.E.2d 635 (Ill. Ct. App. 2005).

5. McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group, 47 P.3d 1209 (Haw. 2002).

6. Arsenault v. McConarty, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 500 (2006).

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.

The case is currently on appeal. The AMA has filed an amicus brief in support of Dr. Lerner,1 pointing out that third-party claims had previously been rejected in New Jersey, where the injured victim is not readily identifiable. The brief emphasizes the folly of placing the physician or therapist in the untenable position of serving two potentially competing interests when a physician’s priority should be providing care to the patient. It referenced a similar case in Kansas, where a motorist who had fallen asleep at the wheel struck a bicyclist. The motorist was being treated by a neurologist for a sleep disorder.2 The Kansas Supreme Court held that there was no special relationship between the doctor and the cyclist that would impose a duty to warn the motorist about harming a third party.

Other jurisdictions have likewise rejected attempts at “derivative duties” in automobile accident cases. The Connecticut Supreme Court has ruled3 that doctors are immune from third party traffic accident lawsuits, as such litigation would detract from what’s best for the patient (“a physician’s desire to avoid lawsuits may result in far more restrictive advice than necessary for the patient’s well-being”). In that case, the defendant-gastroenterologist, Dr. Troncale, was treating a patient with hepatic encephalopathy and had not warned of the associated risk of driving. And an Illinois court dismissed a third party’s case against a hospital when one of its physicians fell asleep at the wheel after working excessive hours.4

In contrast, other jurisdictions have found a legal duty for physicians toward nonpatient victims. For example, in McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group,5 a car suddenly veered across five lanes of traffic, striking an 11-year-old girl and crushing her against a cement planter. The driver alleged that the prescription medication, Prazosin, caused him to lose control of the car, and that the treating physician was negligent, first in prescribing an inappropriate type and dose of medication, and second in failing to warn of potential side effects that could affect driving ability. The Hawaii Supreme Court emphasized that the risk of tort liability to an individual physician already discourages negligent prescribing; therefore, a physician does not have a duty to third parties where the alleged negligence involves prescribing decisions, i.e., whether to prescribe medication at all, which medication to prescribe, and what dosage to use. On the other hand, physicians have a duty to their patients to warn of potential adverse effects and this responsibility should therefore extend to third parties. Thus, liability would attach to injuries of innocent third parties as a result of failing to warn of a medication’s effects on driving—unless a reasonable person could be expected to be aware of this risk without the warning.

A foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm is an important but not the only decisive factor in construing the existence of legal duty. Under some circumstances, the term “special relationship” has been employed based on a consideration of existing social values, customs, and policy considerations. In a Massachusetts case,6 a family physician had failed to warn his patient of the risk of diabetes drugs when operating a vehicle. Some 45 minutes after the patient’s discharge from the hospital, he developed hypoglycemia, losing consciousness and injuring a motorcyclist who then sued the doctor. The court invoked the “special relationship” rationale in ruling that the doctor owed a duty to the motorcyclist for public policy reasons.

Dr. Tan is professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera, In the Superior Court of New Jersey Appellate Division, Docket No. A-001255-18T3.

2. Calwell v. Hassan, 925 P.2d 422, 430 (Kan. 1996).

3. Jarmie v. Troncale, 50 A.3d 802 (Conn. 2012).

4. Brewster v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Med. Ctr., 836 N.E.2d 635 (Ill. Ct. App. 2005).

5. McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group, 47 P.3d 1209 (Haw. 2002).

6. Arsenault v. McConarty, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 500 (2006).

Don’t Mix Off-label Use With Off-the-rack Pills

A pregnant woman in Wisconsin received prenatal care from a family practitioner. The patient had hypertension, so at about 38 weeks’ gestation, the decision was made to induce labor.

On May 15, 2012, the family practitioner used misoprostol to induce labor. The patient received 100 mcg vaginally at 12:24

At 1:28

Variable late decelerations occurred at 11:36

Although the family practitioner was present at the bedside at 12:40

The on-call physician accomplished a vacuum delivery at 1:30

The child now has severe cerebral palsy, with gross motor involvement in the arms and legs. He can communicate through augmentative communication devices but cannot actually speak. He will require full-time care for the rest of his life.

Continue to: The defense took the position...

The defense took the position that while the dosage of misoprostol was excessive, the drug was no longer active in the mother’s body, based on its half-life, when the fetal distress occurred.

VERDICT

Four days before trial, the case was settled for $9 million.

COMMENTARY

I suspect many of you have made a pot roast—and at least some of you have used the simple, tried-and-true method of putting the meat into the slow cooker with a packet of onion soup mix. It makes a tasty dinner with minimal effort. But onion soup packets are for making onion soup—not seasoning pot roast. Guess what? You just used that soup mix off-label!

As clinicians, we all use medications for clinical indications that haven’t been specifically authorized by the FDA—and we shouldn’t stop. Off-label prescribing is legal, common, and often supported by the standard of care.

But there is a risk: The pill or tablet prepared by the manufacturer is generally aimed at the intended on-label use, not off-label uses. In this case, misoprostol (brand name, Cytotec) is approved by the FDA for prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers and peptic ulcer disease. The package insert describes dosing as follows:

The recommended adult oral dose of Cytotec for reducing the risk of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers is 200 mcg four times daily with food. If this dose cannot be tolerated, a dose of 100 mcg can be used.1

Continue to: We should not be shocked...

We should not be shocked, then, that Cytotec is supplied as 100- and 200-mcg round white tablets. However, it is frequently used off label for cervical ripening during labor at a dose of “25 mcg inserted into the posterior vaginal fornix.”2

This brings us to the malpractice trap. While off-label use may be appropriate, off-label uses may not neatly “fit” with the substance prepared by the manufacturer. To be properly administered for cervical ripening, the available tablet of misoprostol must be cut with a pill cutter or razor prior to administration.3 Furthermore, dosage is more accurate if the tablet fragments are individually weighed after cutting.3

In this case, the discrepancy between the pill prepared by the manufacturer (100 mcg) and the dosage needed (25 mcg) appears to have caught the defendant family practitioner off guard. So the take-home message is: Use medications as supported by the standard of care—but when using a drug off label, do not assume the product supplied by the manufacturer is appropriate for use as is.

Another interesting aspect of this case is the defense strategy. Most clinicians are aware that the tort of negligence involves (1) duty, (2) breach, (3) causation, and (4) harm. However, it is more logically consistent to think of the elements in this way: (1) duty, (2) breach, (3) harm, and if harm has occurred, (4) examine causation (ie, the logical connection between breach and harm).

In malpractice cases, attorneys frequently focus on one of these specific elements. In this case, the physician’s duty of care and the harm stemming from cerebral palsy are clearly established. Thus, breach and causation take center stage.

Continue to: The defense lawyers...

The defense lawyers acknowledged there was a breach, noting the dosage was “excessive.” However, they argued that this error didn’t matter because the drug was no longer active in the patient’s body. In other words, there was no causal connection between the inappropriately high dose and the resultant uterine tachysystole and fetal distress. This is a difficult road for several reasons.

First, the chief danger of using misoprostol is uterine hyperstimulation and fetal distress. The defense would have to argue the hyperstimulation and fetal distress were coincidental and unrelated to the misoprostol—which carries a black box warning for these very adverse effects. The plaintiff’s attorney is sure to make a big deal out of the black box warning in front of the jury—noting any reasonable clinician practicing obstetrics should be aware of the risks that come with misoprostol’s use. You can almost hear the argument in summation: “It is so important, they drew a warning box around it.”

Furthermore, making the argument that the misoprostol was not in the mother’s system at the time the fetal distress started would entail dueling expert testimony about pharmacokinetics and bioavailability—concepts that are difficult for lay jurors to understand. Misoprostol has a half-life of about 20 to 40 min when administered orally and about 60 min when administered vaginally.4 We know the mother received the overdose of misoprostol at 12:24

The plaintiff’s team might counter with an expert’s explanation that misoprostol’s bioavailability is increased 2- to 3-fold with vaginal versus oral administration. It would also be observed that compared with oral administration, vaginal administration of misoprostol is associated with a slower increase in plasma concentrations but longer elevations (peaking about 1-2 hours after vaginal administration).5

At best, the defense expert would be able to argue that the serum level likely peaked 1 to 2 hours after administration (1:24-2:24

Continue to: Most jurors would...

Most jurors would take a skeptical view of the defendant’s argument that the negative outcome in this case was coincidental. Some might even be angered by it. This realization likely prompted the defense to settle this case for $9 million.

IN SUMMARY

Onion soup mix makes great soup, but it’s an even better seasoning for pot roast. Similarly, there are pharmacologic agents that are effective for conditions for which they are not formally indicated. Do not withhold judicious off-label use of medications when appropriate. However, be aware that off-label uses may require extra attention, and dosing and administration may not be consistent with the product you have on hand. Don’t hesitate to seek guidance from pharmacy colleagues when you have questions—they are an underutilized resource and are generally happy to share their expertise.

1. Cytotec [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2009.

2. Misoprostol: dosing considerations. PDR: Prescribers’ Digital Reference. www.pdr.net/drug-summary/Cytotec-misoprostol-1044#8. Accessed July 29, 2019.

3. Williams MC, Tsibris JC, Davis G, et al. Dose variation that is associated with approximated one-quarter tablet doses of misoprostol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):615-619.

4. Yount SM, Lassiter N. The pharmacology of prostaglandins for induction of labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(2):133-144; quiz 238-239.

5. Danielsson KG, Marions L, Rodriguez A, et al. Comparison between oral and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(2):275-280.

A pregnant woman in Wisconsin received prenatal care from a family practitioner. The patient had hypertension, so at about 38 weeks’ gestation, the decision was made to induce labor.

On May 15, 2012, the family practitioner used misoprostol to induce labor. The patient received 100 mcg vaginally at 12:24

At 1:28

Variable late decelerations occurred at 11:36

Although the family practitioner was present at the bedside at 12:40

The on-call physician accomplished a vacuum delivery at 1:30

The child now has severe cerebral palsy, with gross motor involvement in the arms and legs. He can communicate through augmentative communication devices but cannot actually speak. He will require full-time care for the rest of his life.

Continue to: The defense took the position...

The defense took the position that while the dosage of misoprostol was excessive, the drug was no longer active in the mother’s body, based on its half-life, when the fetal distress occurred.

VERDICT

Four days before trial, the case was settled for $9 million.

COMMENTARY

I suspect many of you have made a pot roast—and at least some of you have used the simple, tried-and-true method of putting the meat into the slow cooker with a packet of onion soup mix. It makes a tasty dinner with minimal effort. But onion soup packets are for making onion soup—not seasoning pot roast. Guess what? You just used that soup mix off-label!

As clinicians, we all use medications for clinical indications that haven’t been specifically authorized by the FDA—and we shouldn’t stop. Off-label prescribing is legal, common, and often supported by the standard of care.

But there is a risk: The pill or tablet prepared by the manufacturer is generally aimed at the intended on-label use, not off-label uses. In this case, misoprostol (brand name, Cytotec) is approved by the FDA for prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers and peptic ulcer disease. The package insert describes dosing as follows:

The recommended adult oral dose of Cytotec for reducing the risk of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers is 200 mcg four times daily with food. If this dose cannot be tolerated, a dose of 100 mcg can be used.1

Continue to: We should not be shocked...

We should not be shocked, then, that Cytotec is supplied as 100- and 200-mcg round white tablets. However, it is frequently used off label for cervical ripening during labor at a dose of “25 mcg inserted into the posterior vaginal fornix.”2

This brings us to the malpractice trap. While off-label use may be appropriate, off-label uses may not neatly “fit” with the substance prepared by the manufacturer. To be properly administered for cervical ripening, the available tablet of misoprostol must be cut with a pill cutter or razor prior to administration.3 Furthermore, dosage is more accurate if the tablet fragments are individually weighed after cutting.3

In this case, the discrepancy between the pill prepared by the manufacturer (100 mcg) and the dosage needed (25 mcg) appears to have caught the defendant family practitioner off guard. So the take-home message is: Use medications as supported by the standard of care—but when using a drug off label, do not assume the product supplied by the manufacturer is appropriate for use as is.

Another interesting aspect of this case is the defense strategy. Most clinicians are aware that the tort of negligence involves (1) duty, (2) breach, (3) causation, and (4) harm. However, it is more logically consistent to think of the elements in this way: (1) duty, (2) breach, (3) harm, and if harm has occurred, (4) examine causation (ie, the logical connection between breach and harm).

In malpractice cases, attorneys frequently focus on one of these specific elements. In this case, the physician’s duty of care and the harm stemming from cerebral palsy are clearly established. Thus, breach and causation take center stage.

Continue to: The defense lawyers...

The defense lawyers acknowledged there was a breach, noting the dosage was “excessive.” However, they argued that this error didn’t matter because the drug was no longer active in the patient’s body. In other words, there was no causal connection between the inappropriately high dose and the resultant uterine tachysystole and fetal distress. This is a difficult road for several reasons.

First, the chief danger of using misoprostol is uterine hyperstimulation and fetal distress. The defense would have to argue the hyperstimulation and fetal distress were coincidental and unrelated to the misoprostol—which carries a black box warning for these very adverse effects. The plaintiff’s attorney is sure to make a big deal out of the black box warning in front of the jury—noting any reasonable clinician practicing obstetrics should be aware of the risks that come with misoprostol’s use. You can almost hear the argument in summation: “It is so important, they drew a warning box around it.”

Furthermore, making the argument that the misoprostol was not in the mother’s system at the time the fetal distress started would entail dueling expert testimony about pharmacokinetics and bioavailability—concepts that are difficult for lay jurors to understand. Misoprostol has a half-life of about 20 to 40 min when administered orally and about 60 min when administered vaginally.4 We know the mother received the overdose of misoprostol at 12:24

The plaintiff’s team might counter with an expert’s explanation that misoprostol’s bioavailability is increased 2- to 3-fold with vaginal versus oral administration. It would also be observed that compared with oral administration, vaginal administration of misoprostol is associated with a slower increase in plasma concentrations but longer elevations (peaking about 1-2 hours after vaginal administration).5

At best, the defense expert would be able to argue that the serum level likely peaked 1 to 2 hours after administration (1:24-2:24

Continue to: Most jurors would...

Most jurors would take a skeptical view of the defendant’s argument that the negative outcome in this case was coincidental. Some might even be angered by it. This realization likely prompted the defense to settle this case for $9 million.

IN SUMMARY

Onion soup mix makes great soup, but it’s an even better seasoning for pot roast. Similarly, there are pharmacologic agents that are effective for conditions for which they are not formally indicated. Do not withhold judicious off-label use of medications when appropriate. However, be aware that off-label uses may require extra attention, and dosing and administration may not be consistent with the product you have on hand. Don’t hesitate to seek guidance from pharmacy colleagues when you have questions—they are an underutilized resource and are generally happy to share their expertise.

A pregnant woman in Wisconsin received prenatal care from a family practitioner. The patient had hypertension, so at about 38 weeks’ gestation, the decision was made to induce labor.

On May 15, 2012, the family practitioner used misoprostol to induce labor. The patient received 100 mcg vaginally at 12:24

At 1:28

Variable late decelerations occurred at 11:36

Although the family practitioner was present at the bedside at 12:40

The on-call physician accomplished a vacuum delivery at 1:30

The child now has severe cerebral palsy, with gross motor involvement in the arms and legs. He can communicate through augmentative communication devices but cannot actually speak. He will require full-time care for the rest of his life.

Continue to: The defense took the position...

The defense took the position that while the dosage of misoprostol was excessive, the drug was no longer active in the mother’s body, based on its half-life, when the fetal distress occurred.

VERDICT

Four days before trial, the case was settled for $9 million.

COMMENTARY

I suspect many of you have made a pot roast—and at least some of you have used the simple, tried-and-true method of putting the meat into the slow cooker with a packet of onion soup mix. It makes a tasty dinner with minimal effort. But onion soup packets are for making onion soup—not seasoning pot roast. Guess what? You just used that soup mix off-label!

As clinicians, we all use medications for clinical indications that haven’t been specifically authorized by the FDA—and we shouldn’t stop. Off-label prescribing is legal, common, and often supported by the standard of care.

But there is a risk: The pill or tablet prepared by the manufacturer is generally aimed at the intended on-label use, not off-label uses. In this case, misoprostol (brand name, Cytotec) is approved by the FDA for prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers and peptic ulcer disease. The package insert describes dosing as follows:

The recommended adult oral dose of Cytotec for reducing the risk of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers is 200 mcg four times daily with food. If this dose cannot be tolerated, a dose of 100 mcg can be used.1

Continue to: We should not be shocked...

We should not be shocked, then, that Cytotec is supplied as 100- and 200-mcg round white tablets. However, it is frequently used off label for cervical ripening during labor at a dose of “25 mcg inserted into the posterior vaginal fornix.”2

This brings us to the malpractice trap. While off-label use may be appropriate, off-label uses may not neatly “fit” with the substance prepared by the manufacturer. To be properly administered for cervical ripening, the available tablet of misoprostol must be cut with a pill cutter or razor prior to administration.3 Furthermore, dosage is more accurate if the tablet fragments are individually weighed after cutting.3

In this case, the discrepancy between the pill prepared by the manufacturer (100 mcg) and the dosage needed (25 mcg) appears to have caught the defendant family practitioner off guard. So the take-home message is: Use medications as supported by the standard of care—but when using a drug off label, do not assume the product supplied by the manufacturer is appropriate for use as is.

Another interesting aspect of this case is the defense strategy. Most clinicians are aware that the tort of negligence involves (1) duty, (2) breach, (3) causation, and (4) harm. However, it is more logically consistent to think of the elements in this way: (1) duty, (2) breach, (3) harm, and if harm has occurred, (4) examine causation (ie, the logical connection between breach and harm).

In malpractice cases, attorneys frequently focus on one of these specific elements. In this case, the physician’s duty of care and the harm stemming from cerebral palsy are clearly established. Thus, breach and causation take center stage.

Continue to: The defense lawyers...

The defense lawyers acknowledged there was a breach, noting the dosage was “excessive.” However, they argued that this error didn’t matter because the drug was no longer active in the patient’s body. In other words, there was no causal connection between the inappropriately high dose and the resultant uterine tachysystole and fetal distress. This is a difficult road for several reasons.

First, the chief danger of using misoprostol is uterine hyperstimulation and fetal distress. The defense would have to argue the hyperstimulation and fetal distress were coincidental and unrelated to the misoprostol—which carries a black box warning for these very adverse effects. The plaintiff’s attorney is sure to make a big deal out of the black box warning in front of the jury—noting any reasonable clinician practicing obstetrics should be aware of the risks that come with misoprostol’s use. You can almost hear the argument in summation: “It is so important, they drew a warning box around it.”

Furthermore, making the argument that the misoprostol was not in the mother’s system at the time the fetal distress started would entail dueling expert testimony about pharmacokinetics and bioavailability—concepts that are difficult for lay jurors to understand. Misoprostol has a half-life of about 20 to 40 min when administered orally and about 60 min when administered vaginally.4 We know the mother received the overdose of misoprostol at 12:24

The plaintiff’s team might counter with an expert’s explanation that misoprostol’s bioavailability is increased 2- to 3-fold with vaginal versus oral administration. It would also be observed that compared with oral administration, vaginal administration of misoprostol is associated with a slower increase in plasma concentrations but longer elevations (peaking about 1-2 hours after vaginal administration).5

At best, the defense expert would be able to argue that the serum level likely peaked 1 to 2 hours after administration (1:24-2:24

Continue to: Most jurors would...

Most jurors would take a skeptical view of the defendant’s argument that the negative outcome in this case was coincidental. Some might even be angered by it. This realization likely prompted the defense to settle this case for $9 million.

IN SUMMARY

Onion soup mix makes great soup, but it’s an even better seasoning for pot roast. Similarly, there are pharmacologic agents that are effective for conditions for which they are not formally indicated. Do not withhold judicious off-label use of medications when appropriate. However, be aware that off-label uses may require extra attention, and dosing and administration may not be consistent with the product you have on hand. Don’t hesitate to seek guidance from pharmacy colleagues when you have questions—they are an underutilized resource and are generally happy to share their expertise.

1. Cytotec [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2009.

2. Misoprostol: dosing considerations. PDR: Prescribers’ Digital Reference. www.pdr.net/drug-summary/Cytotec-misoprostol-1044#8. Accessed July 29, 2019.

3. Williams MC, Tsibris JC, Davis G, et al. Dose variation that is associated with approximated one-quarter tablet doses of misoprostol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):615-619.

4. Yount SM, Lassiter N. The pharmacology of prostaglandins for induction of labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(2):133-144; quiz 238-239.

5. Danielsson KG, Marions L, Rodriguez A, et al. Comparison between oral and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(2):275-280.

1. Cytotec [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2009.

2. Misoprostol: dosing considerations. PDR: Prescribers’ Digital Reference. www.pdr.net/drug-summary/Cytotec-misoprostol-1044#8. Accessed July 29, 2019.

3. Williams MC, Tsibris JC, Davis G, et al. Dose variation that is associated with approximated one-quarter tablet doses of misoprostol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):615-619.

4. Yount SM, Lassiter N. The pharmacology of prostaglandins for induction of labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(2):133-144; quiz 238-239.

5. Danielsson KG, Marions L, Rodriguez A, et al. Comparison between oral and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(2):275-280.

The mesh mess, enmeshed in controversy

CASE Complications with mesh placement for SUI

A 47-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents 5 months posthysterectomy with evidence of urinary tract infection (UTI). Escherichia coli is isolated, and she responds to antibiotic therapy.

Her surgical history includes a mini-sling procedure using a needleless device and mesh placement in order to correct progressive worsening of loss of urine when coughing and sneezing. She also reported slight pelvic pain, dysuria, and urgency upon urination at that time. After subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), she underwent the vaginal hysterectomy.

Following her UTI treatment, a host of problems occur for the patient, including pelvic pain and dyspareunia. Her male partner reports “feeling something during sex,” especially at the anterior vaginal wall. A plain radiograph of the abdomen identifies a 2 cm x 2 cm stone over the vaginal mesh. In consultation with female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery subspecialists, lithotripsy is performed, with the stone fragmented. The patient remains symptomatic, however.

The mesh is noted to be eroding through the vaginal wall. An attempt is made to excise the mesh, initially via transuretheral resection, then through a laparoscopic approach. Due to the mesh being embedded in the tissue, however, an open approach is undertaken. Extensive excision of the mesh and stone fragments is performed. Postoperatively, the patient reports “dry vagina,” with no other genitourinary complaints.

The patient sues. She sues the mesh manufacturer. She also seeks to sue the gynecologist who placed the sling and vaginal mesh (as she says she was not informed of “all the risks” of vaginal mesh placement. She is part of a class action lawsuit, along with thousands of other women.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The device manufacturer settled out of court with the class action suit. (The gynecologist was never formally a defendant because the patient/plaintiff was advised to “drop the physician from the suit.”) The attorneys representing the class action received 40% of the award plus presented costs for the representation. The class as a whole received a little more than 50% of the negotiated award. The patient in this case received $60,000.

Medical background

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a prevalent condition; it affects 35% of women.1 Overall, 80% of women aged 80 or younger will undergo some form of surgery for POP during their lifetime.2 The pathophysiology of SUI includes urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency.3

Surgical correction for urinary incontinence: A timeline

Use of the gracilis muscle flap to surgically correct urinary incontinence was introduced in 1907. This technique has been replaced by today’s more common Burch procedure, which was first described in 1961. Surgical mesh use dates back to the 1950s, when it was primarily used for abdominal hernia repair. Tension-free tape was introduced in 1995.4-6

Continue to: In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration...

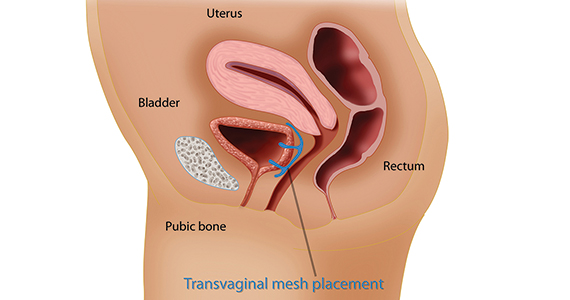

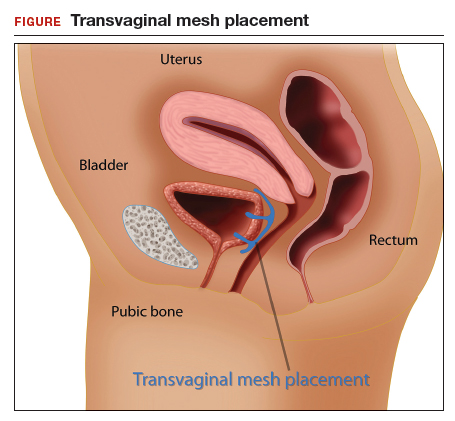

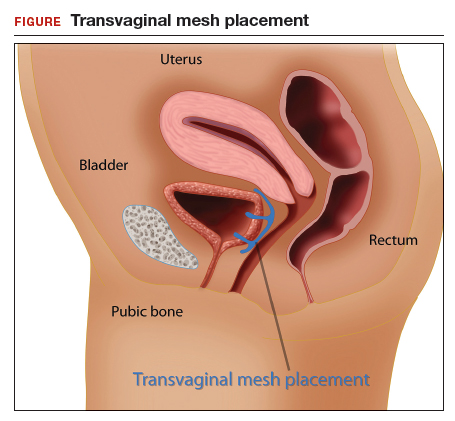

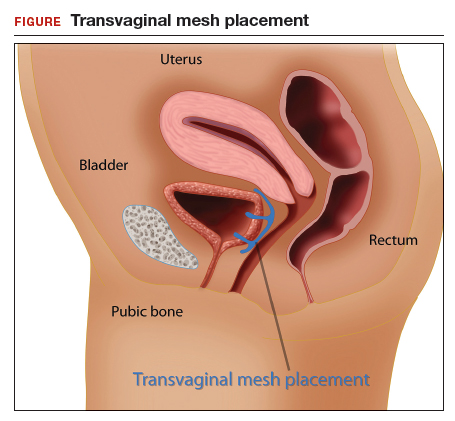

In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permitted use of the first transvaginal meshes, which were designed to treat SUI—the midurethral sling. These mesh slings were so successful that similar meshes were developed to treat POP.7 Almost immediately there were problems with the new POP devices, and 3 years later Boston Scientific recalled its device.8 Nonetheless, the FDA cleared more than 150 devices using surgical mesh for urogynecologic indications (FIGURE).9

Mesh complications

Managing complications from intravesical mesh is a clinically challenging problem. Bladder perforation, stone formation, and penetration through the vagina can occur. Bladder-related complications can manifest as recurrent UTIs and obstructive urinary symptoms, especially in association with stone formation. From the gynecologic perspective, the more common complications with mesh utilization are pelvic pain, groin pain, dyspareunia, contracture and scarring of mesh, and narrowing of the vaginal canal.10 Mesh erosion problems will occur in an estimated 10% to 25% of transvaginal mesh POP implants.11

In 2008, a comparison of transvaginal mesh to native tissue repair (suture-based) or other (biologic) grafts was published.12 The bottom line: there is insufficient evidence to suggest that transvaginal mesh significantly improves outcomes for both posterior and apical defects.

Legal background

Mesh used for surgical purposes is a medical device, which legally is a product—a special product to be sure, but a product nonetheless. Products are subject to product liability rules. Mesh is also subject to an FDA regulatory system. We will briefly discuss products liability and the regulation of devices, both of which have played important roles in mesh-related injuries.

Products liability

As a general matter, defective products subject their manufacturer and seller to liability. There are several legal theories regarding product liability: negligence (in which the defect was caused through carelessness), breach of warranty or guarantee (in addition to express warranties, there are a number of implied warranties for products, including that it is fit for its intended purpose), and strict liability (there was a defect in the product, but it may not have been because of negligence). The product may be defective in the way it was designed, manufactured, or packaged, or it may be defective because adequate instructions and warning were not given to consumers.

Of course, not every product involved in an injury is defective—most automobile accidents, for example, are not the result of any defect in the automobile. In medicine, almost no product (device or pharmaceutical) is entirely safe. In some ways they are unavoidably unsafe and bound to cause some injuries. But when injuries are caused by a defect in the product (design or manufacturing defect or failure to warn), then there may be products liability. Most products liability cases arise under state law.

FDA’s device regulations

Both drugs and medical devices are subject to FDA review and ordinarily require some form of FDA clearance before they may be marketed. In the case of devices, the FDA has 3 classes, with an increase in risk to the user from Class I to III. Various levels of FDA review are required before marketing of the device is permitted, again with the intensity of review increasing from I to III as follows:

- Class I devices pose the least risk, have the least regulation, and are subject to general controls (ie, manufacturing and marketing practices).

- Class II devices pose slightly higher risks and are subject to special controls in addition to the criteria for Class I.

- Class III devices pose the most risk to patients and require premarket approval (scientific review and studies are required to ensure efficacy and safety).13

Continue to: There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices...

There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices. For Class III devices, the thorough FDA review of the safety of a device may limit the ability of an injured patient to sue based on the state product liability laws.14 For the most part, this “preemption” of state law has not played a major role in mesh litigation because they were initially classified as Class II devices which did not require or include a detailed FDA review.15

The duty to warn of the dangers and risk of medical devices means that manufacturers (or sellers) of devices are obligated to inform health care providers and other medical personnel of the risks. Unlike other manufacturers, device manufacturers do not have to directly warn consumers—because physicians deal directly with patients and prescribe the devices. Therefore, the health care providers, rather than the manufacturers, are obligated to inform the patient.16 This is known as the learned intermediary rule. Manufacturers may still be liable for failure to warn if they do not convey to health care providers proper warnings.

Manufacturers and sellers are not the only entities that may be subject to liability caused by medical devices. Hospitals or other entities that stock and care for devices are responsible for maintaining the safety and functionality of devices in their care.

Health care providers also may be responsible for injuries from medical devices. Generally, that liability is based on negligence. Negligence may relate to selecting an improper device, installing or using it incorrectly, or failing to give the patient adequate information (or informed consent) about the device and alternatives to it.17

A look at the mesh mess

There are a lot of distressing problems and professional disappointments in dissecting the “mesh mess,” including a failure of the FDA to regulate effectively, the extended sale and promotion of intrinsic sphincter deficiency mesh products, the improper use of mesh by physicians even after the risks were known, and, in some instances, the taking advantage of injured patients by attorneys and businesses.18 A lot of finger pointing also has occurred.19 We will recount some of the lowlights of this unfortunate tale.

Continue to: The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh...

The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh as Class II after deciding these products were “substantially equivalent” to older surgical meshes. This, of course, proved not to be the case.20 The FDA started receiving thousands of reports of adverse events and, in 2008, warned physicians to be vigilant for adverse events from the mesh. The FDA’s notification recommendations regarding mesh included the following13:

- Obtain specialized training for each mesh implantation technique, and be cognizant of risks.

- Be vigilant for potential adverse events from mesh, including erosion and infection.

- Be observant for complications associated with tools of transvaginal placement (ie, bowel, bladder, and vessel perforation).

- Inform patients that implantation of mesh is permanent and complications may require additional surgery for correction.

- Be aware that complications may affect quality of life—eg, pain with intercourse, scarring, and vaginal wall narrowing (POP repair).

- Provide patients with written copy of patient labeling from the surgical mesh manufacturer.

In 2011, the FDA issued a formal warning to providers that transvaginal mesh posed meaningful risks beyond nonmesh surgery. The FDA’s bulletin draws attention to how the mesh is placed more so than the material per se.19,21 Mesh was a Class II device for sacrocolpopexy or midurethral sling and, similarly, the transvaginal kit was also a Class II device. Overall, use of mesh midurethral slings has been well received as treatment for SUI. The FDA also accepted it for POP, however, but with increasingly strong warnings. The FDA’s 2011 communication stated, “This update is to inform you that serious complications associated with surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of POP are not rare….Furthermore, it is not clear that transvaginal POP repair with mesh is more effective than traditional non-mesh repair in all patients with POP and it may expose patients to greater risk.”7,13

In 2014 the FDA proposed reclassifying mesh to a Class III device, which would require that manufacturers obtain approval, based on safety and effectiveness, before selling mesh. Not until 2016 did the FDA actually reclassify the mess as Class III. Of course, during this time, mesh manufacturers were well aware of the substantial problems the products were causing.13

After serious problems with mesh became well known, and especially after FDA warnings, the use of mesh other than as indicated by the FDA was increasingly risky from a legal (as well as a health) standpoint. As long as mesh was still on the market, of course, it was available for use. But use of mesh for POP procedures without good indications in a way that was contrary to the FDA warnings might well be negligent.

Changes to informed consent

The FDA warnings also should have changed the informed consent for the use of mesh.22 Informed consent commonly consists of the following:

- informing the patient of the proposed procedure

- describing risks (and benefits) of the proposed process

- explaining reasonable alternatives

- noting the risks of taking no action.

Information that is material to a decision should be disclosed. If mesh were going to be used, after the problems of mesh were known and identified by the FDA (other than midurethral slings as treatment of SUI), the risks should have been clearly identified for patients, with alternatives outlined. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics has 8 fundamental concepts with regard to informed consent that are worth keeping in mind23:

- Obtaining informed consent for medical treatment and research is an ethical requirement.

- The process expresses respect for the patient as a person.

- It protects patients against unwanted treatment and allows patients’ active involvement in medical planning and care.

- Communication is of paramount importance.

- Informed consent is a process and not a signature on a form.

- A commitment to informed consent and to provision of medical benefit to the patient are linked to provision of care.

- If obtaining informed consent is impossible, a designated surrogate should be identified representing the patient’s best interests.

- Knowledge on the part of the provider regarding state and federal requirements is necessary.

Continue to: Lawsuits line up...

Lawsuits line up

The widespread use of a product with a significant percentage of injuries and eventually with warnings about injuries from use sounds like the formula for a lot of lawsuits. This certainly has happened. A large number of suits—both class actions and individual actions—were filed as a result of mesh injuries.24 These suits were overwhelmingly against the manufacturer, although some included physicians.7 Device makers are more attractive defendants for several reasons. First, they have very deep pockets. In addition, jurors are generally much less sympathetic to large companies than to doctors. Large class actions meant that there were many different patients among the plaintiffs, and medical malpractice claims in most states have a number of trial difficulties not present in other product liability cases. Common defendants have included Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic.

Some of the cases resulted in very large damage awards against manufacturers based on various kinds of product(s) liability. Many other cases were settled or tried with relatively small damages. There were, in addition, a number of instances in which the manufacturers were not liable. Of the 32 plaintiffs who have gone to trial thus far, 24 have obtained verdicts totaling $345 million ($14 million average). The cases that have settled have been for much less—perhaps $60,000 on average. A number of cases remain unresolved. To date, the estimate is that 100,000 women have received almost $8 billion from 7 device manufacturers to resolve claims.25

Some state attorneys general have gotten into the process as well. Attorneys general from California, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Washington have filed lawsuits against Johnson & Johnson, claiming that they deceived doctors and patients about the risks of their pelvic mesh. The states claim that marketing and instructional literature should have contained more information about the risks. Some physicians in these states have expressed concern that these lawsuit risks may do more harm than good because the suits conflate mesh used to treat incontinence with the more risky mesh for POP.26

The “ugly” of class action lawsuits

We have discussed both the sad (the injuries to patients) and the bad (the slow regulatory response and continuing injuries). (The ethics of the marketing by the manufacturers might also be raised as the bad.27) Next, let’s look briefly at the ugly.

Some of the patients affected by mesh injuries have been victimized a second time by medical “lenders” and some of their attorneys. Press reports describe patients with modest awards paying 40% in attorney fees (on the high side for personal injury settlements) plus extravagant costs—leaving modest amounts of actual recovery.25

Worse still, a process of “medical lending” has arisen in mesh cases.28 Medical lenders may contact mesh victims offering to pay up front for surgery to remove mesh, and then place a lien against the settlement for repayment at a much higher rate. They might pay the surgeon $2,500 for the surgery, but place a lien on the settlement amount for $60,000.29,30 In addition, there are allegations that lawyers may recruit the doctors to overstate the injuries or do unnecessary removal surgery because that will likely up the award.31 A quick Google search indicates dozens of offers of cash now for your mesh lawsuit (transvaginal and hernia repair).

The patient in our hypothetical case at the beginning had a fairly typical experience. She was a member of a class filing and received a modest settlement. The attorneys representing the class were allowed by the court to charge substantial attorneys’ fees and costs. The patient had the good sense to avoid medical lenders, although other members of the class did use medical lenders and are now filing complaints about the way they were treated by these lenders.

- Maintain surgical skills and be open to new technology. Medical practice requires constant updating and use of new and improved technology as it comes along. By definition, new technology often requires new skills and understanding. A significant portion of surgeons using mesh indicated that they had not read the instructions for use, or had done so only once.1 CME programs that include surgical education remain of particular value.

- Whether new technology or old, it is essential to keep up to date on all FDA bulletins pertinent to devices and pharmaceuticals that you use and prescribe. For example, in 2016 and 2018 the FDA warned that the use of a very old class of drugs (fluoroquinolones) should be limited. It advised "that the serious side effects associated with fluoroquinolones generally outweigh the benefits for patients with acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis, and uncomplicated urinary tract infections who have other treatment options. For patients with these conditions, fluoroquinolones should be reserved for those who do not have alternative treatment options."2 Continued, unnecessary prescriptions for fluoroquinolones would put a physician at some legal risk whether or not the physician had paid any attention to the warning.

- Informed consent is a very important legal and medical process. Take it seriously, and make sure the patient has the information necessary to make informed decisions about treatment. Document the process and the information provided. In some cases consider directing patients to appropriate literature or websites of the manufacturers.

- As to the use of mesh, if not following FDA advice, it is important to document the reason for this and to document the informed consent especially carefully.

- Follow patients after mesh placement for a minimum of 1 year and emphasize to patients they should convey signs and symptoms of complications from initial placement.3 High-risk patients should be of particular concern and be monitored very closely.

References

- Kirkpatrick G, Faber KD, Fromer DL. Transvaginal mesh placement and the instructions for use: a survey of North American urologists. J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urpr.2018.05.004.

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur together. July 26, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm500143.htm. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

- Maral I, Ozkardeş H, Peşkircioğlu L, et al. Prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in both sexes at or after age 15 years: a cross-sectional study. J Urol. 2001;165:408-412.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

- Chang J, Lee D. Midurethral slings in the mesh litigation era. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(suppl 2): S68-S75.

- Mattingly R, ed. TeLinde's Operative Gynecology, 5th edition. Lippincott, William, and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA; 1997.

- Burch J. Urethrovaginal fixation to Cooper's ligament for correction of stress incontinence, cystocele, and prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;81:281-290.

- Ulmsten U, Falconer C, Johnson P, et al. A multicenter study of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1998;9:210-213.

- Kuhlmann-Capek MJ, Kilic GS, Shah AB, et al. Enmeshed in controversy: use of vaginal mesh in the current medicolegal environment. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:241-243.

- Powell SF. Changing our minds: reforming the FDA medical device reclassification process. Food Drug Law J. 2018;73:177-209.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Surgical Mesh for Treatment of Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence. September 2011. https://www.thesenatorsfirm.com/documents/OBS.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD004014.

- Ganj FA, Ibeanu OA, Bedestani A, Nolan TE, Chesson RR. Complications of transvaginal monofilament polypropylene mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:919-925.

- Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1131-1142.

- FDA public health notification: serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. October 20, 2008. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Riegel v. Medtronic, 552 U.S. 312 (2008).

- Whitney DW. Guide to preemption of state-law claims against Class III PMA medical devices. Food Drug Law J. 2010;65:113-139.

- Alam P, Iglesia CB. Informed consent for reconstructive pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016;43:131-139.

- Nosti PA, Iglesia CB. Medicolegal issues surrounding devices and mesh for surgical treatment of prolapse and incontinence. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:221-228.

- Shepherd CG. Transvaginal mesh litigation: a new opportunity to resolve mass medical device failure claims. Tennessee Law Rev. 2012;80:3:477-94.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

- Cohn JA, Timbrook Brown E, Kowalik CG, et al. The mesh controversy. F1000Research website. https://f1000research.com/articles/5-2423/v1. Accessed June 17, 2019.

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Meeting, February 12, 2019. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/media/122867/download. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Mucowski SJ, Jurnalov C, Phelps JY. Use of vaginal mesh in the face of recent FDA warnings and litigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:103.e1-e4.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 439: informed consent. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):401-408.

- Souders CP, Eilber KS, McClelland L, et al. The truth behind transvaginal mesh litigation: devices, timelines, and provider characteristics. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:21-25.

- Goldstein M. As pelvic mesh settlements near $8 billion, women question lawyers' fees. New York Times. February 1, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/01/business/pelvic-mesh-settlements-lawyers.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Johnson G. Surgeons fear pelvic mesh lawsuits will spook patients. Associated Press News. January 10, 2019. https://www.apnews.com/25777c3c33e3489283b1dc2ebdde6b55. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Clarke RN. Medical device marketing and the ethics of vaginal mesh kit marketing. In The Innovation and Evolution of Medical Devices. New York, NY: Springer; 2019:103-123.

- Top 5 drug and medical device developments of 2018. Law 360. January 1, 2019. Accessed through LexisNexis.

- Frankel A, Dye J. The Lien Machine. New breed of investor profits by financing surgeries for desperate women patients. Reuters. August 18, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-litigation-mesh/. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Sullivan T. New report looks at intersection of "medical lending" and pelvic mesh lawsuits. Policy & Medicine. May 5, 2018. https://www.policymed.com/2015/08/medical-lending-and-pelvic-mesh-litigation.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Goldstein M, Sliver-Greensberg J. How profiteers lure women into often-unneeded surgery. New York Times. April 14, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/14/business/vaginal-mesh-surgery-lawsuits-financing.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

CASE Complications with mesh placement for SUI

A 47-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents 5 months posthysterectomy with evidence of urinary tract infection (UTI). Escherichia coli is isolated, and she responds to antibiotic therapy.

Her surgical history includes a mini-sling procedure using a needleless device and mesh placement in order to correct progressive worsening of loss of urine when coughing and sneezing. She also reported slight pelvic pain, dysuria, and urgency upon urination at that time. After subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), she underwent the vaginal hysterectomy.

Following her UTI treatment, a host of problems occur for the patient, including pelvic pain and dyspareunia. Her male partner reports “feeling something during sex,” especially at the anterior vaginal wall. A plain radiograph of the abdomen identifies a 2 cm x 2 cm stone over the vaginal mesh. In consultation with female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery subspecialists, lithotripsy is performed, with the stone fragmented. The patient remains symptomatic, however.

The mesh is noted to be eroding through the vaginal wall. An attempt is made to excise the mesh, initially via transuretheral resection, then through a laparoscopic approach. Due to the mesh being embedded in the tissue, however, an open approach is undertaken. Extensive excision of the mesh and stone fragments is performed. Postoperatively, the patient reports “dry vagina,” with no other genitourinary complaints.

The patient sues. She sues the mesh manufacturer. She also seeks to sue the gynecologist who placed the sling and vaginal mesh (as she says she was not informed of “all the risks” of vaginal mesh placement. She is part of a class action lawsuit, along with thousands of other women.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The device manufacturer settled out of court with the class action suit. (The gynecologist was never formally a defendant because the patient/plaintiff was advised to “drop the physician from the suit.”) The attorneys representing the class action received 40% of the award plus presented costs for the representation. The class as a whole received a little more than 50% of the negotiated award. The patient in this case received $60,000.

Medical background

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a prevalent condition; it affects 35% of women.1 Overall, 80% of women aged 80 or younger will undergo some form of surgery for POP during their lifetime.2 The pathophysiology of SUI includes urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency.3

Surgical correction for urinary incontinence: A timeline

Use of the gracilis muscle flap to surgically correct urinary incontinence was introduced in 1907. This technique has been replaced by today’s more common Burch procedure, which was first described in 1961. Surgical mesh use dates back to the 1950s, when it was primarily used for abdominal hernia repair. Tension-free tape was introduced in 1995.4-6

Continue to: In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration...

In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permitted use of the first transvaginal meshes, which were designed to treat SUI—the midurethral sling. These mesh slings were so successful that similar meshes were developed to treat POP.7 Almost immediately there were problems with the new POP devices, and 3 years later Boston Scientific recalled its device.8 Nonetheless, the FDA cleared more than 150 devices using surgical mesh for urogynecologic indications (FIGURE).9

Mesh complications

Managing complications from intravesical mesh is a clinically challenging problem. Bladder perforation, stone formation, and penetration through the vagina can occur. Bladder-related complications can manifest as recurrent UTIs and obstructive urinary symptoms, especially in association with stone formation. From the gynecologic perspective, the more common complications with mesh utilization are pelvic pain, groin pain, dyspareunia, contracture and scarring of mesh, and narrowing of the vaginal canal.10 Mesh erosion problems will occur in an estimated 10% to 25% of transvaginal mesh POP implants.11

In 2008, a comparison of transvaginal mesh to native tissue repair (suture-based) or other (biologic) grafts was published.12 The bottom line: there is insufficient evidence to suggest that transvaginal mesh significantly improves outcomes for both posterior and apical defects.

Legal background

Mesh used for surgical purposes is a medical device, which legally is a product—a special product to be sure, but a product nonetheless. Products are subject to product liability rules. Mesh is also subject to an FDA regulatory system. We will briefly discuss products liability and the regulation of devices, both of which have played important roles in mesh-related injuries.

Products liability

As a general matter, defective products subject their manufacturer and seller to liability. There are several legal theories regarding product liability: negligence (in which the defect was caused through carelessness), breach of warranty or guarantee (in addition to express warranties, there are a number of implied warranties for products, including that it is fit for its intended purpose), and strict liability (there was a defect in the product, but it may not have been because of negligence). The product may be defective in the way it was designed, manufactured, or packaged, or it may be defective because adequate instructions and warning were not given to consumers.

Of course, not every product involved in an injury is defective—most automobile accidents, for example, are not the result of any defect in the automobile. In medicine, almost no product (device or pharmaceutical) is entirely safe. In some ways they are unavoidably unsafe and bound to cause some injuries. But when injuries are caused by a defect in the product (design or manufacturing defect or failure to warn), then there may be products liability. Most products liability cases arise under state law.

FDA’s device regulations

Both drugs and medical devices are subject to FDA review and ordinarily require some form of FDA clearance before they may be marketed. In the case of devices, the FDA has 3 classes, with an increase in risk to the user from Class I to III. Various levels of FDA review are required before marketing of the device is permitted, again with the intensity of review increasing from I to III as follows:

- Class I devices pose the least risk, have the least regulation, and are subject to general controls (ie, manufacturing and marketing practices).

- Class II devices pose slightly higher risks and are subject to special controls in addition to the criteria for Class I.

- Class III devices pose the most risk to patients and require premarket approval (scientific review and studies are required to ensure efficacy and safety).13

Continue to: There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices...

There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices. For Class III devices, the thorough FDA review of the safety of a device may limit the ability of an injured patient to sue based on the state product liability laws.14 For the most part, this “preemption” of state law has not played a major role in mesh litigation because they were initially classified as Class II devices which did not require or include a detailed FDA review.15

The duty to warn of the dangers and risk of medical devices means that manufacturers (or sellers) of devices are obligated to inform health care providers and other medical personnel of the risks. Unlike other manufacturers, device manufacturers do not have to directly warn consumers—because physicians deal directly with patients and prescribe the devices. Therefore, the health care providers, rather than the manufacturers, are obligated to inform the patient.16 This is known as the learned intermediary rule. Manufacturers may still be liable for failure to warn if they do not convey to health care providers proper warnings.

Manufacturers and sellers are not the only entities that may be subject to liability caused by medical devices. Hospitals or other entities that stock and care for devices are responsible for maintaining the safety and functionality of devices in their care.

Health care providers also may be responsible for injuries from medical devices. Generally, that liability is based on negligence. Negligence may relate to selecting an improper device, installing or using it incorrectly, or failing to give the patient adequate information (or informed consent) about the device and alternatives to it.17

A look at the mesh mess

There are a lot of distressing problems and professional disappointments in dissecting the “mesh mess,” including a failure of the FDA to regulate effectively, the extended sale and promotion of intrinsic sphincter deficiency mesh products, the improper use of mesh by physicians even after the risks were known, and, in some instances, the taking advantage of injured patients by attorneys and businesses.18 A lot of finger pointing also has occurred.19 We will recount some of the lowlights of this unfortunate tale.

Continue to: The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh...

The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh as Class II after deciding these products were “substantially equivalent” to older surgical meshes. This, of course, proved not to be the case.20 The FDA started receiving thousands of reports of adverse events and, in 2008, warned physicians to be vigilant for adverse events from the mesh. The FDA’s notification recommendations regarding mesh included the following13:

- Obtain specialized training for each mesh implantation technique, and be cognizant of risks.

- Be vigilant for potential adverse events from mesh, including erosion and infection.

- Be observant for complications associated with tools of transvaginal placement (ie, bowel, bladder, and vessel perforation).

- Inform patients that implantation of mesh is permanent and complications may require additional surgery for correction.