User login

High-grade cervical dysplasia in pregnancy

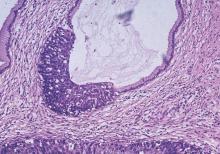

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) describes a precancerous lesion of the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix. The cervical cancer screening paradigm in the United States begins with collection of cervical cytology with a Pap smear, frequently in conjunction with human papillomavirus testing. Abnormalities will frequently lead to colposcopy with directed biopsy, which can result in a diagnosis of CIN. There are different grades of severity within CIN, which aids in making treatment recommendations.

Pregnancy is a convenient time to capture women for cervical cancer screening, given the increased contact with health care providers. Routine guidelines should be followed for screening women who are pregnant, as collection of cervical cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) cotesting is safe.

In women who have been found to have abnormal cytology, CIN or malignancy has been identified in up to 19% of cases (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jul;191[1]:105-13). High-grade lesions identified in pregnant women create a unique management dilemma.

Terminology

The Bethesda system describes colposcopic abnormalities as CIN and divides premalignant lesions into grades from 1 to 3 with the highest grade representing more worrisome lesions. CIN2 has been found to have poor reproducibility and likely represents a mix of low- and high-grade lesions. In addition, there is concern that HPV-associated lesions of the lower anogenital tract have incongruent terminology among different specialties that may not accurately represent the current understanding of HPV pathogenesis.

In 2012, the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) project of the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) advocated for consistent terminology across all lower anogenital tract lesions with HPV, including CIN (Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013 Jan;32[1]:76-115).

With this new terminology, CIN1 is referred to as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL). CIN2 is characterized by its p16 immunostaining; lesions that are p16 negative are considered LSIL, while those that are positive are considered HSIL (high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion). While this staining is not universally performed, physicians will start seeing p16 staining results with increasing frequency on their cervical biopsies. CIN3 lesions are referred to as HSIL.

Given the current understanding of HPV-mediated disease, and a commitment to represent the most up-to-date information, the LAST project terminology of HSIL to represent previously identified CIN2 and CIN3 lesions will be used for the remainder of this text.

Diagnosis

There is little data on the natural history of HSIL diagnosed after colposcopy, as most women get some form of therapy. The information that is available suggests that in patients with untreated HSIL, the cumulative incidence of malignancy is as high as 30% at 30 years (Lancet Oncol. 2008 May;9[5]:425-34). Treatment recommendations for excision are aimed at addressing this alarming number; however, care must be individualized, especially in the setting of pregnancy.

If abnormal cervical cytology is obtained on routine screening, appropriate patients should be referred for colposcopic exam. Physicians performing colposcopy should be familiar with the physiologic effects of pregnancy that can obscure the exam, including the increased cervical mucus production, prominence of endocervical glands, and increased vascularity.

Colposcopic-directed ectocervical biopsies have been found to be safe in pregnancy, and these women should be provided the same care as those who are not pregnant (Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Jun;81[6]:915-8). Endocervical sampling and endometrial sampling should not be performed, however, and physicians should remain dedicated to checking pregnancy tests prior to colposcopy.

HSIL cytology should prompt a biopsy in pregnancy; a decision to skip the biopsy and perform an excisional procedure in this setting is not recommended regardless of patient or gestational age. If LSIL (CIN1) is noted on biopsy, reevaluation post partum should be strongly considered, unless a suspicious lesion was felt to be inadequately biopsied.

Management

Managing HSIL in pregnancy focuses on diagnosis and excluding malignancy, while treatment can be reserved for the postpartum period. When choosing a management option, consider individual patient factors such as colposcopic appearance of the lesion, gestational age, and access to health care.

If HSIL is noted on colposcopic-directed biopsy, consider one of several options. The most conservative approach is reevaluation with cytology and colposcopy 6 weeks post partum. This is an option for patients who do not have a colposcopic exam that was concerning for an invasive lesion, were able to be adequately biopsied, and will reliably return for follow-up. Many physicians feel more comfortable with repeat cytology and colposcopy in 3 months from the original biopsy. The most aggressive management would include an excisional procedure during pregnancy.

There are varying rates of regression of biopsy-proven HSIL in pregnancy ranging from 34% to 70% (Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Mar;93[3]:359-62; Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85[9]:1134-7; Reprod Sci. 2009 Nov;16[11]:1034-9). Out of more than 200 patients across these three studies, just two patients were diagnosed with an invasive lesion post partum. Given the low likelihood of progression during pregnancy and the high rate of regression, an excisional procedure should be considered only in cases where there is concern about invasive carcinoma.

In cases where an invasive lesion is suspected, consider an an excisional procedure. While there is some evidence that performing a laser excisional procedure early in pregnancy (18 weeks and earlier) can be safely done, that is not the most common management strategy in the United States (Tumori. 1998 Sep-Oct;84[5]:567-70; Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007 Jan-Feb;17[1]:127-31). In this circumstance, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted where consideration can be made for performing a cold knife conization. Physicians should be aware of the increased risk of bleeding with this procedure in pregnancy and the potential for preterm birth. There is little literature to guide counseling regarding these risks, and the decision to perform an excisional procedure should be made with a multidisciplinary team (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Jan 4. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3980-y).

The see-and-treat paradigm is not recommended in pregnancy. Those patients with poor follow-up should still undergo colposcopic-directed biopsies prior to any excisional procedure.

Treatment recommendations in pregnancy should be made on the basis of careful consideration of individual patient factors, with strong consideration of repeat testing with cytology and colposcopy prior to an excision procedure.

Dr. Sullivan is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Gehrig reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) describes a precancerous lesion of the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix. The cervical cancer screening paradigm in the United States begins with collection of cervical cytology with a Pap smear, frequently in conjunction with human papillomavirus testing. Abnormalities will frequently lead to colposcopy with directed biopsy, which can result in a diagnosis of CIN. There are different grades of severity within CIN, which aids in making treatment recommendations.

Pregnancy is a convenient time to capture women for cervical cancer screening, given the increased contact with health care providers. Routine guidelines should be followed for screening women who are pregnant, as collection of cervical cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) cotesting is safe.

In women who have been found to have abnormal cytology, CIN or malignancy has been identified in up to 19% of cases (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jul;191[1]:105-13). High-grade lesions identified in pregnant women create a unique management dilemma.

Terminology

The Bethesda system describes colposcopic abnormalities as CIN and divides premalignant lesions into grades from 1 to 3 with the highest grade representing more worrisome lesions. CIN2 has been found to have poor reproducibility and likely represents a mix of low- and high-grade lesions. In addition, there is concern that HPV-associated lesions of the lower anogenital tract have incongruent terminology among different specialties that may not accurately represent the current understanding of HPV pathogenesis.

In 2012, the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) project of the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) advocated for consistent terminology across all lower anogenital tract lesions with HPV, including CIN (Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013 Jan;32[1]:76-115).

With this new terminology, CIN1 is referred to as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL). CIN2 is characterized by its p16 immunostaining; lesions that are p16 negative are considered LSIL, while those that are positive are considered HSIL (high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion). While this staining is not universally performed, physicians will start seeing p16 staining results with increasing frequency on their cervical biopsies. CIN3 lesions are referred to as HSIL.

Given the current understanding of HPV-mediated disease, and a commitment to represent the most up-to-date information, the LAST project terminology of HSIL to represent previously identified CIN2 and CIN3 lesions will be used for the remainder of this text.

Diagnosis

There is little data on the natural history of HSIL diagnosed after colposcopy, as most women get some form of therapy. The information that is available suggests that in patients with untreated HSIL, the cumulative incidence of malignancy is as high as 30% at 30 years (Lancet Oncol. 2008 May;9[5]:425-34). Treatment recommendations for excision are aimed at addressing this alarming number; however, care must be individualized, especially in the setting of pregnancy.

If abnormal cervical cytology is obtained on routine screening, appropriate patients should be referred for colposcopic exam. Physicians performing colposcopy should be familiar with the physiologic effects of pregnancy that can obscure the exam, including the increased cervical mucus production, prominence of endocervical glands, and increased vascularity.

Colposcopic-directed ectocervical biopsies have been found to be safe in pregnancy, and these women should be provided the same care as those who are not pregnant (Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Jun;81[6]:915-8). Endocervical sampling and endometrial sampling should not be performed, however, and physicians should remain dedicated to checking pregnancy tests prior to colposcopy.

HSIL cytology should prompt a biopsy in pregnancy; a decision to skip the biopsy and perform an excisional procedure in this setting is not recommended regardless of patient or gestational age. If LSIL (CIN1) is noted on biopsy, reevaluation post partum should be strongly considered, unless a suspicious lesion was felt to be inadequately biopsied.

Management

Managing HSIL in pregnancy focuses on diagnosis and excluding malignancy, while treatment can be reserved for the postpartum period. When choosing a management option, consider individual patient factors such as colposcopic appearance of the lesion, gestational age, and access to health care.

If HSIL is noted on colposcopic-directed biopsy, consider one of several options. The most conservative approach is reevaluation with cytology and colposcopy 6 weeks post partum. This is an option for patients who do not have a colposcopic exam that was concerning for an invasive lesion, were able to be adequately biopsied, and will reliably return for follow-up. Many physicians feel more comfortable with repeat cytology and colposcopy in 3 months from the original biopsy. The most aggressive management would include an excisional procedure during pregnancy.

There are varying rates of regression of biopsy-proven HSIL in pregnancy ranging from 34% to 70% (Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Mar;93[3]:359-62; Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85[9]:1134-7; Reprod Sci. 2009 Nov;16[11]:1034-9). Out of more than 200 patients across these three studies, just two patients were diagnosed with an invasive lesion post partum. Given the low likelihood of progression during pregnancy and the high rate of regression, an excisional procedure should be considered only in cases where there is concern about invasive carcinoma.

In cases where an invasive lesion is suspected, consider an an excisional procedure. While there is some evidence that performing a laser excisional procedure early in pregnancy (18 weeks and earlier) can be safely done, that is not the most common management strategy in the United States (Tumori. 1998 Sep-Oct;84[5]:567-70; Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007 Jan-Feb;17[1]:127-31). In this circumstance, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted where consideration can be made for performing a cold knife conization. Physicians should be aware of the increased risk of bleeding with this procedure in pregnancy and the potential for preterm birth. There is little literature to guide counseling regarding these risks, and the decision to perform an excisional procedure should be made with a multidisciplinary team (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Jan 4. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3980-y).

The see-and-treat paradigm is not recommended in pregnancy. Those patients with poor follow-up should still undergo colposcopic-directed biopsies prior to any excisional procedure.

Treatment recommendations in pregnancy should be made on the basis of careful consideration of individual patient factors, with strong consideration of repeat testing with cytology and colposcopy prior to an excision procedure.

Dr. Sullivan is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Gehrig reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) describes a precancerous lesion of the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix. The cervical cancer screening paradigm in the United States begins with collection of cervical cytology with a Pap smear, frequently in conjunction with human papillomavirus testing. Abnormalities will frequently lead to colposcopy with directed biopsy, which can result in a diagnosis of CIN. There are different grades of severity within CIN, which aids in making treatment recommendations.

Pregnancy is a convenient time to capture women for cervical cancer screening, given the increased contact with health care providers. Routine guidelines should be followed for screening women who are pregnant, as collection of cervical cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) cotesting is safe.

In women who have been found to have abnormal cytology, CIN or malignancy has been identified in up to 19% of cases (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jul;191[1]:105-13). High-grade lesions identified in pregnant women create a unique management dilemma.

Terminology

The Bethesda system describes colposcopic abnormalities as CIN and divides premalignant lesions into grades from 1 to 3 with the highest grade representing more worrisome lesions. CIN2 has been found to have poor reproducibility and likely represents a mix of low- and high-grade lesions. In addition, there is concern that HPV-associated lesions of the lower anogenital tract have incongruent terminology among different specialties that may not accurately represent the current understanding of HPV pathogenesis.

In 2012, the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) project of the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) advocated for consistent terminology across all lower anogenital tract lesions with HPV, including CIN (Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013 Jan;32[1]:76-115).

With this new terminology, CIN1 is referred to as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL). CIN2 is characterized by its p16 immunostaining; lesions that are p16 negative are considered LSIL, while those that are positive are considered HSIL (high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion). While this staining is not universally performed, physicians will start seeing p16 staining results with increasing frequency on their cervical biopsies. CIN3 lesions are referred to as HSIL.

Given the current understanding of HPV-mediated disease, and a commitment to represent the most up-to-date information, the LAST project terminology of HSIL to represent previously identified CIN2 and CIN3 lesions will be used for the remainder of this text.

Diagnosis

There is little data on the natural history of HSIL diagnosed after colposcopy, as most women get some form of therapy. The information that is available suggests that in patients with untreated HSIL, the cumulative incidence of malignancy is as high as 30% at 30 years (Lancet Oncol. 2008 May;9[5]:425-34). Treatment recommendations for excision are aimed at addressing this alarming number; however, care must be individualized, especially in the setting of pregnancy.

If abnormal cervical cytology is obtained on routine screening, appropriate patients should be referred for colposcopic exam. Physicians performing colposcopy should be familiar with the physiologic effects of pregnancy that can obscure the exam, including the increased cervical mucus production, prominence of endocervical glands, and increased vascularity.

Colposcopic-directed ectocervical biopsies have been found to be safe in pregnancy, and these women should be provided the same care as those who are not pregnant (Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Jun;81[6]:915-8). Endocervical sampling and endometrial sampling should not be performed, however, and physicians should remain dedicated to checking pregnancy tests prior to colposcopy.

HSIL cytology should prompt a biopsy in pregnancy; a decision to skip the biopsy and perform an excisional procedure in this setting is not recommended regardless of patient or gestational age. If LSIL (CIN1) is noted on biopsy, reevaluation post partum should be strongly considered, unless a suspicious lesion was felt to be inadequately biopsied.

Management

Managing HSIL in pregnancy focuses on diagnosis and excluding malignancy, while treatment can be reserved for the postpartum period. When choosing a management option, consider individual patient factors such as colposcopic appearance of the lesion, gestational age, and access to health care.

If HSIL is noted on colposcopic-directed biopsy, consider one of several options. The most conservative approach is reevaluation with cytology and colposcopy 6 weeks post partum. This is an option for patients who do not have a colposcopic exam that was concerning for an invasive lesion, were able to be adequately biopsied, and will reliably return for follow-up. Many physicians feel more comfortable with repeat cytology and colposcopy in 3 months from the original biopsy. The most aggressive management would include an excisional procedure during pregnancy.

There are varying rates of regression of biopsy-proven HSIL in pregnancy ranging from 34% to 70% (Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Mar;93[3]:359-62; Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85[9]:1134-7; Reprod Sci. 2009 Nov;16[11]:1034-9). Out of more than 200 patients across these three studies, just two patients were diagnosed with an invasive lesion post partum. Given the low likelihood of progression during pregnancy and the high rate of regression, an excisional procedure should be considered only in cases where there is concern about invasive carcinoma.

In cases where an invasive lesion is suspected, consider an an excisional procedure. While there is some evidence that performing a laser excisional procedure early in pregnancy (18 weeks and earlier) can be safely done, that is not the most common management strategy in the United States (Tumori. 1998 Sep-Oct;84[5]:567-70; Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007 Jan-Feb;17[1]:127-31). In this circumstance, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted where consideration can be made for performing a cold knife conization. Physicians should be aware of the increased risk of bleeding with this procedure in pregnancy and the potential for preterm birth. There is little literature to guide counseling regarding these risks, and the decision to perform an excisional procedure should be made with a multidisciplinary team (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Jan 4. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3980-y).

The see-and-treat paradigm is not recommended in pregnancy. Those patients with poor follow-up should still undergo colposcopic-directed biopsies prior to any excisional procedure.

Treatment recommendations in pregnancy should be made on the basis of careful consideration of individual patient factors, with strong consideration of repeat testing with cytology and colposcopy prior to an excision procedure.

Dr. Sullivan is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Gehrig reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

A trip through the history of gynecologic oncology

The subspecialty of gynecologic oncology was formalized less than 50 years ago with the creation of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology and subspecialty training and board certification. The formation of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) – and the many clinical trials spearheaded by that group – has further advanced evidence-based treatments, resulting in improved survival outcomes, quality of life, and preventive strategies.

While it is not possible to provide a comprehensive and exhaustive review of all of the advances, we hope to highlight many of the notable advances in this article.Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide with 528,000 new cases in 2012. The majority of cervical cancer cases are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). While the standard therapies for cervical cancer have been long established (radical hysterectomy for stage I and radiation therapy for locally advanced disease), one of the most significant advances in the past 50 years was the addition of radiation-sensitizing chemotherapy (cisplatin) administered concurrently with radiation therapy.

In randomized trials in both early and advanced cervical cancer, the risk of death was reduced by 30%-50%. These studies changed the paradigm for the treatment of cervical cancer (N Engl J Med. 1999 Apr 15;340[15]:1137-43; N Engl J Med. 1999 Apr 15;340[15]:1144-53; J Clin Oncol. 2000 Apr;18[8]:1606-13).

Future studies evaluating biologic adjuncts or additional chemotherapy are currently underway or awaiting data maturation.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) highlighted the “Top 5 advances in 50 years of Modern Oncology” in 2014, and second on the list was the approval of the HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer. Vaccines have been developed that can protect against types 2, 4 or 9 of HPV. In a 2014 study, depending on vaccination coverage, the relative number of cervical cancer cases avoided was 34% in Africa, 27% for America, 26% for Asia, 21% for Europe, and worldwide was estimated at 27% (Vaccine. 2014 Feb 3;32[6]:733-9).

While the benefit from HPV vaccination has been proven, in the United States, only about a third of eligible girls and women have been vaccinated. Efforts should focus on expanding vaccination penetration to eligible girls, boys, women, and men.

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States with an estimated 54,870 cases and 10,170 deaths annually. Notable advances in the management of women with endometrial cancer have arisen because of a better understanding that there are two types of endometrial cancer – type I and type II.

The type I endometrial cancers tend to be associated with lower stage of disease at the time of diagnosis and fewer recurrences, while type II endometrial cancer is associated with worse outcomes.

Tailoring the surgical approaches and adjuvant therapy for women with endometrial cancer has led to improved outcomes. The GOG conducted a large prospective randomized trial of laparotomy versus laparoscopic surgical staging for women with clinical early-stage endometrial cancer (LAP2). Laparoscopy was associated with improved perioperative outcomes and was found to be noninferior to laparotomy with regards to survival outcomes (J Clin Oncol. 2012 Mar 1;30[7]:695-700). Therefore, minimally invasive surgery has become widely accepted for the surgical staging of women with endometrial cancer.

Appropriate surgical staging allows for tailoring of postoperative adjuvant therapy. The current evidence suggests that vaginal brachytherapy should be the adjuvant treatment of choice over whole pelvic radiation in women with early-stage endometrial cancer (Lancet. 2010 Mar 6;375[9717]:816-23). Studies are underway to evaluate the role of both adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy in women with early-stage type II endometrial cancer who are felt to be at high risk for recurrent disease, as well as how to improve on the therapeutic options for women with advanced or recurrent disease.

Ovarian cancer

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most deadly gynecologic malignancy in the United States with 21,290 cases and 14,180 deaths in 2015. The concept of ovarian tumor debulking was first described by Dr. Joe Meigs in 1934, but did not gain traction until the mid-1970s when Dr. C. Thomas Griffiths published his work (Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1975 Oct;42:101-4).

While there are no randomized trials proving that surgical cytoreduction improves overall survival, most retrospective studies support this concept. In 2009, Chi et al. showed improved median survival in women with ovarian cancer based on the increased percentage of women who underwent optimal cytoreduction (Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jul;114[1]:26-31). This has led to modifications of surgical techniques and surgical goals with an effort to maximally cytoreduce all of the visible disease.

While initial surgical debulking is the goal, there are circumstances when a different approach may be indicated. Vergote et al. conducted a prospective randomized trial of 670 women with advanced ovarian cancer. In this study, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking was not inferior to primary debulking followed by chemotherapy with regards to progression-free survival and overall survival. However, initial surgery was associated with increased surgical complications and perioperative mortality as compared with interval surgery. Therefore, in women who are not felt to be candidates for optimal cytoreduction, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval surgery may be an appropriate treatment strategy (N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 2;363[10]:943-53.).

There have been several notable advances and a series of randomized trials – predominately conducted by the GOG – that have resulted in improved overall survival and progression-free interval in women with ovarian cancer. However, none are as significant as the discovery of paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy (cisplatin and carboplatin).

In 1962, samples of the Pacific Yew’s bark were collected and, 2 years later, the extracts from this bark were found to have cytotoxic activity. There were initial difficulties suspending the drug in solution; however, ultimately a formulation in ethanol, cremophor, and saline was found to be effective. In 1984, the National Cancer Institute began clinical trials of paclitaxel and it was found to be highly effective in ovarian cancer. In 1992, it was approved for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Cisplatin was approved in 1978. Carboplatin entered clinical trials in 1982 and was approved for women with recurrent ovarian cancer in 1989.

There were a series of trials beginning in the late 1980s that established the role of platinum agents and led us to GOG 111. This trial evaluated cisplatin with either cyclophosphamide or paclitaxel. The paclitaxel combination was superior and in 2003 two trials were published that solidified carboplatin and paclitaxel as the cornerstone in the treatment of women with ovarian cancer (J Clin Oncol. 2003 Sep 1;21[17]:3194-200; J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Sep 3;95[17]:1320-9).

What has most recently been debated is the route and schedule for both paclitaxel and the platinum agents. In January 2006, the National Cancer Institute released a Clinical Announcement regarding the role of intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy for the treatment of women with optimally debulked ovarian cancer. Of the six trials included in the announcement, four trials showed a benefit for progression-free survival and five studies showed an improvement in overall survival. Armstrong et al (GOG 172) showed a 16-month improvement in overall survival with intravenous (IV) paclitaxel, IP cisplatin, and IP paclitaxel. IP chemotherapy has not been universally embraced by physicians and patients in part because of its toxicity, treatment schedule, and the fact that no IP regimen has been compared with the current standard of IV carboplatin and paclitaxel (N Engl J Med. 2006 Jan 5;354[1]:34-43).

While there have been improvements in 5-year survival over time, most women with advanced ovarian cancer will undergo additional chemotherapy in order to achieve subsequent remissions or maintain stability of disease. Other drugs that have Food and Drug Administration approval in the setting of recurrent ovarian cancer include topotecan, liposomal doxorubicin, gemcitabine, bevacizumab, altretamine, carboplatin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, and melphalan. Olaparib was recently approved as monotherapy in women with a germline BRCA-mutation who had received three or more prior lines of chemotherapy.

Minimally invasive surgery

Over the last 30 years, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in gynecologic oncology, particularly for endometrial cancer, has gone from a niche procedure to the standard of care. The introduction of laparoscopy into gynecologic oncology started in the early 1990s. In a series of 59 women undergoing laparoscopy for endometrial cancer, Childers et al. demonstrated feasibility of the technique and low laparotomy conversion rates (Gynecol Oncol. 1993 Oct;51[1]:33-8.). The GOG trial, LAP2, supported the equivalent oncologic outcomes of MIS versus laparotomy for the treatment of endometrial cancer. While many surgeons and centers offered laparoscopic surgery, there were issues with the learning curve that limited its widespread use.

In 2005, the FDA approval of the robotic platform for gynecologic surgery resulted in at least a doubling of the proportion of endometrial cancer patients treated with MIS (Int J Med Robot. 2009 Dec;5[4]:392-7.). In 2012, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology published a consensus statement regarding robotic-assisted surgery in gynecologic oncology (Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Feb;124[2]:180-4.). This review highlights the advantages of the robotics platform with regards to expanding MIS to women with cervical and ovarian cancer; the improvements in outcomes in the obese woman with endometrial cancer; and that the learning curve for robotic surgery is shorter than for traditional laparoscopy. Issues requiring further research include cost analysis as the cost of the new technology decreases, and opportunities for improvement in patient and physician quality of life.

Sentinel node mapping

The rationale for sentinel node mapping is that if one or more sentinel lymph nodes is/are negative for malignancy, then the other regional lymph nodes will also be negative. This would thereby avoid the need for a complete lymph node dissection and its resultant complications, including chronic lymphedema. Much of the work pioneering this strategy has been in breast cancer and melanoma, but data are rapidly emerging for these techniques in gynecologic malignancies.

Candidates for sentinel lymph node biopsy for vulvar cancer include those with a lesion more than 1mm in depth, a tumor less than 4 cm in size, and no obvious metastatic disease on exam or preoperative imaging. Additionally, recommendations have been made regarding case volume in order to achieve limited numbers of false-negative results and to maintain competency. In the study by Van der Zee et al. of 403 patients (623 groins) who underwent sentinel node procedures, the false-negative rate was 0-2%. The overall survival rate was 97% at 3 years (J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 20;26[6]:884-9). However, a more recent data from the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG 173) showed a slightly higher false-negative rate of 8% (J Clin Oncol. 2012 Nov 1;30[31]:3786-91). Overall survival data are pending from this study.

While sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer has been feasible for many years and has been well described, the questioned role of completed lymphadenectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer has led to a resurgence of interest in these techniques. While blue dye and radiolabeled tracer methods have historically been the most popular mapping solutions, the advent of endoscopic near-infrared imaging, with its higher sensitivity and good depth penetration, has added options. Indocyanine green fluorescence can be easily detected during robotic surgery and as experience with these techniques increase, successful mapping and sensitivity will increase.

Genetics

While hereditary cancer syndromes have been recognized for many years, detecting the genetic mutations that may increase an individual’s risk of developing a malignancy were not elucidated until the early 1990s. In gynecologic oncology, the most commonly encountered syndromes involve mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and hereditary non–polyposis colorectal cancer, which causes mutations in DNA mismatch-repair genes and increase the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer.

The SGO recently published a statement on risk assessment for inherited gynecologic cancer predispositions. In this statement “the evaluation for the presence of a hereditary cancer syndrome enables physicians to provide individualized and quantified assessment of cancer risk, as well as options for tailored screening and preventions strategies that may reduce morbidity associated with the development of malignancy” (Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Jan;136[1]:3-7). Beyond risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, therapeutic strategies targeting patients with germline mutations have been developed (PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated women with ovarian cancer).

In August 2015, ASCO released an updated policy statement on genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility and highlighted five key areas: germ-line implications of somatic mutation profiling; multigene panel testing for cancer susceptibility; quality assurance in genetic testing; education for oncology professionals; and access to cancer genetic services.

Antiemetics

Rounding out ASCO’s “Top 5 advances in 50 years of Modern Oncology” was the improvement in patients’ quality of life from supportive therapies, in particular antinausea medications.

Several of the agents commonly used in gynecologic oncology rate high (cisplatin) to moderate (carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, ifosfamide) with regards to emetogenicity. The advent of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (for example, ondansetron) has significantly improved the quality of life of patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. In addition to improving quality of life, the decrease in nausea and vomiting can also decrease life-threatening complications such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Both ASCO and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network both have guidelines for the management of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Throughout 2016, Ob.Gyn. News will celebrate its 50th anniversary with exclusive articles looking at the evolution of the specialty, including the history of contraception, changes in gynecologic surgery, and the transformation of the well-woman visit. Look for these articles and more special features in the pages of Ob.Gyn. News and online at obgynnews.com.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The subspecialty of gynecologic oncology was formalized less than 50 years ago with the creation of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology and subspecialty training and board certification. The formation of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) – and the many clinical trials spearheaded by that group – has further advanced evidence-based treatments, resulting in improved survival outcomes, quality of life, and preventive strategies.

While it is not possible to provide a comprehensive and exhaustive review of all of the advances, we hope to highlight many of the notable advances in this article.Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide with 528,000 new cases in 2012. The majority of cervical cancer cases are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). While the standard therapies for cervical cancer have been long established (radical hysterectomy for stage I and radiation therapy for locally advanced disease), one of the most significant advances in the past 50 years was the addition of radiation-sensitizing chemotherapy (cisplatin) administered concurrently with radiation therapy.

In randomized trials in both early and advanced cervical cancer, the risk of death was reduced by 30%-50%. These studies changed the paradigm for the treatment of cervical cancer (N Engl J Med. 1999 Apr 15;340[15]:1137-43; N Engl J Med. 1999 Apr 15;340[15]:1144-53; J Clin Oncol. 2000 Apr;18[8]:1606-13).

Future studies evaluating biologic adjuncts or additional chemotherapy are currently underway or awaiting data maturation.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) highlighted the “Top 5 advances in 50 years of Modern Oncology” in 2014, and second on the list was the approval of the HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer. Vaccines have been developed that can protect against types 2, 4 or 9 of HPV. In a 2014 study, depending on vaccination coverage, the relative number of cervical cancer cases avoided was 34% in Africa, 27% for America, 26% for Asia, 21% for Europe, and worldwide was estimated at 27% (Vaccine. 2014 Feb 3;32[6]:733-9).

While the benefit from HPV vaccination has been proven, in the United States, only about a third of eligible girls and women have been vaccinated. Efforts should focus on expanding vaccination penetration to eligible girls, boys, women, and men.

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States with an estimated 54,870 cases and 10,170 deaths annually. Notable advances in the management of women with endometrial cancer have arisen because of a better understanding that there are two types of endometrial cancer – type I and type II.

The type I endometrial cancers tend to be associated with lower stage of disease at the time of diagnosis and fewer recurrences, while type II endometrial cancer is associated with worse outcomes.

Tailoring the surgical approaches and adjuvant therapy for women with endometrial cancer has led to improved outcomes. The GOG conducted a large prospective randomized trial of laparotomy versus laparoscopic surgical staging for women with clinical early-stage endometrial cancer (LAP2). Laparoscopy was associated with improved perioperative outcomes and was found to be noninferior to laparotomy with regards to survival outcomes (J Clin Oncol. 2012 Mar 1;30[7]:695-700). Therefore, minimally invasive surgery has become widely accepted for the surgical staging of women with endometrial cancer.

Appropriate surgical staging allows for tailoring of postoperative adjuvant therapy. The current evidence suggests that vaginal brachytherapy should be the adjuvant treatment of choice over whole pelvic radiation in women with early-stage endometrial cancer (Lancet. 2010 Mar 6;375[9717]:816-23). Studies are underway to evaluate the role of both adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy in women with early-stage type II endometrial cancer who are felt to be at high risk for recurrent disease, as well as how to improve on the therapeutic options for women with advanced or recurrent disease.

Ovarian cancer

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most deadly gynecologic malignancy in the United States with 21,290 cases and 14,180 deaths in 2015. The concept of ovarian tumor debulking was first described by Dr. Joe Meigs in 1934, but did not gain traction until the mid-1970s when Dr. C. Thomas Griffiths published his work (Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1975 Oct;42:101-4).

While there are no randomized trials proving that surgical cytoreduction improves overall survival, most retrospective studies support this concept. In 2009, Chi et al. showed improved median survival in women with ovarian cancer based on the increased percentage of women who underwent optimal cytoreduction (Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jul;114[1]:26-31). This has led to modifications of surgical techniques and surgical goals with an effort to maximally cytoreduce all of the visible disease.

While initial surgical debulking is the goal, there are circumstances when a different approach may be indicated. Vergote et al. conducted a prospective randomized trial of 670 women with advanced ovarian cancer. In this study, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking was not inferior to primary debulking followed by chemotherapy with regards to progression-free survival and overall survival. However, initial surgery was associated with increased surgical complications and perioperative mortality as compared with interval surgery. Therefore, in women who are not felt to be candidates for optimal cytoreduction, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval surgery may be an appropriate treatment strategy (N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 2;363[10]:943-53.).

There have been several notable advances and a series of randomized trials – predominately conducted by the GOG – that have resulted in improved overall survival and progression-free interval in women with ovarian cancer. However, none are as significant as the discovery of paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy (cisplatin and carboplatin).

In 1962, samples of the Pacific Yew’s bark were collected and, 2 years later, the extracts from this bark were found to have cytotoxic activity. There were initial difficulties suspending the drug in solution; however, ultimately a formulation in ethanol, cremophor, and saline was found to be effective. In 1984, the National Cancer Institute began clinical trials of paclitaxel and it was found to be highly effective in ovarian cancer. In 1992, it was approved for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Cisplatin was approved in 1978. Carboplatin entered clinical trials in 1982 and was approved for women with recurrent ovarian cancer in 1989.

There were a series of trials beginning in the late 1980s that established the role of platinum agents and led us to GOG 111. This trial evaluated cisplatin with either cyclophosphamide or paclitaxel. The paclitaxel combination was superior and in 2003 two trials were published that solidified carboplatin and paclitaxel as the cornerstone in the treatment of women with ovarian cancer (J Clin Oncol. 2003 Sep 1;21[17]:3194-200; J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Sep 3;95[17]:1320-9).

What has most recently been debated is the route and schedule for both paclitaxel and the platinum agents. In January 2006, the National Cancer Institute released a Clinical Announcement regarding the role of intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy for the treatment of women with optimally debulked ovarian cancer. Of the six trials included in the announcement, four trials showed a benefit for progression-free survival and five studies showed an improvement in overall survival. Armstrong et al (GOG 172) showed a 16-month improvement in overall survival with intravenous (IV) paclitaxel, IP cisplatin, and IP paclitaxel. IP chemotherapy has not been universally embraced by physicians and patients in part because of its toxicity, treatment schedule, and the fact that no IP regimen has been compared with the current standard of IV carboplatin and paclitaxel (N Engl J Med. 2006 Jan 5;354[1]:34-43).

While there have been improvements in 5-year survival over time, most women with advanced ovarian cancer will undergo additional chemotherapy in order to achieve subsequent remissions or maintain stability of disease. Other drugs that have Food and Drug Administration approval in the setting of recurrent ovarian cancer include topotecan, liposomal doxorubicin, gemcitabine, bevacizumab, altretamine, carboplatin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, and melphalan. Olaparib was recently approved as monotherapy in women with a germline BRCA-mutation who had received three or more prior lines of chemotherapy.

Minimally invasive surgery

Over the last 30 years, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in gynecologic oncology, particularly for endometrial cancer, has gone from a niche procedure to the standard of care. The introduction of laparoscopy into gynecologic oncology started in the early 1990s. In a series of 59 women undergoing laparoscopy for endometrial cancer, Childers et al. demonstrated feasibility of the technique and low laparotomy conversion rates (Gynecol Oncol. 1993 Oct;51[1]:33-8.). The GOG trial, LAP2, supported the equivalent oncologic outcomes of MIS versus laparotomy for the treatment of endometrial cancer. While many surgeons and centers offered laparoscopic surgery, there were issues with the learning curve that limited its widespread use.

In 2005, the FDA approval of the robotic platform for gynecologic surgery resulted in at least a doubling of the proportion of endometrial cancer patients treated with MIS (Int J Med Robot. 2009 Dec;5[4]:392-7.). In 2012, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology published a consensus statement regarding robotic-assisted surgery in gynecologic oncology (Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Feb;124[2]:180-4.). This review highlights the advantages of the robotics platform with regards to expanding MIS to women with cervical and ovarian cancer; the improvements in outcomes in the obese woman with endometrial cancer; and that the learning curve for robotic surgery is shorter than for traditional laparoscopy. Issues requiring further research include cost analysis as the cost of the new technology decreases, and opportunities for improvement in patient and physician quality of life.

Sentinel node mapping

The rationale for sentinel node mapping is that if one or more sentinel lymph nodes is/are negative for malignancy, then the other regional lymph nodes will also be negative. This would thereby avoid the need for a complete lymph node dissection and its resultant complications, including chronic lymphedema. Much of the work pioneering this strategy has been in breast cancer and melanoma, but data are rapidly emerging for these techniques in gynecologic malignancies.

Candidates for sentinel lymph node biopsy for vulvar cancer include those with a lesion more than 1mm in depth, a tumor less than 4 cm in size, and no obvious metastatic disease on exam or preoperative imaging. Additionally, recommendations have been made regarding case volume in order to achieve limited numbers of false-negative results and to maintain competency. In the study by Van der Zee et al. of 403 patients (623 groins) who underwent sentinel node procedures, the false-negative rate was 0-2%. The overall survival rate was 97% at 3 years (J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 20;26[6]:884-9). However, a more recent data from the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG 173) showed a slightly higher false-negative rate of 8% (J Clin Oncol. 2012 Nov 1;30[31]:3786-91). Overall survival data are pending from this study.

While sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer has been feasible for many years and has been well described, the questioned role of completed lymphadenectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer has led to a resurgence of interest in these techniques. While blue dye and radiolabeled tracer methods have historically been the most popular mapping solutions, the advent of endoscopic near-infrared imaging, with its higher sensitivity and good depth penetration, has added options. Indocyanine green fluorescence can be easily detected during robotic surgery and as experience with these techniques increase, successful mapping and sensitivity will increase.

Genetics

While hereditary cancer syndromes have been recognized for many years, detecting the genetic mutations that may increase an individual’s risk of developing a malignancy were not elucidated until the early 1990s. In gynecologic oncology, the most commonly encountered syndromes involve mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and hereditary non–polyposis colorectal cancer, which causes mutations in DNA mismatch-repair genes and increase the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer.

The SGO recently published a statement on risk assessment for inherited gynecologic cancer predispositions. In this statement “the evaluation for the presence of a hereditary cancer syndrome enables physicians to provide individualized and quantified assessment of cancer risk, as well as options for tailored screening and preventions strategies that may reduce morbidity associated with the development of malignancy” (Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Jan;136[1]:3-7). Beyond risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, therapeutic strategies targeting patients with germline mutations have been developed (PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated women with ovarian cancer).

In August 2015, ASCO released an updated policy statement on genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility and highlighted five key areas: germ-line implications of somatic mutation profiling; multigene panel testing for cancer susceptibility; quality assurance in genetic testing; education for oncology professionals; and access to cancer genetic services.

Antiemetics

Rounding out ASCO’s “Top 5 advances in 50 years of Modern Oncology” was the improvement in patients’ quality of life from supportive therapies, in particular antinausea medications.

Several of the agents commonly used in gynecologic oncology rate high (cisplatin) to moderate (carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, ifosfamide) with regards to emetogenicity. The advent of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (for example, ondansetron) has significantly improved the quality of life of patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. In addition to improving quality of life, the decrease in nausea and vomiting can also decrease life-threatening complications such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Both ASCO and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network both have guidelines for the management of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Throughout 2016, Ob.Gyn. News will celebrate its 50th anniversary with exclusive articles looking at the evolution of the specialty, including the history of contraception, changes in gynecologic surgery, and the transformation of the well-woman visit. Look for these articles and more special features in the pages of Ob.Gyn. News and online at obgynnews.com.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The subspecialty of gynecologic oncology was formalized less than 50 years ago with the creation of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology and subspecialty training and board certification. The formation of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) – and the many clinical trials spearheaded by that group – has further advanced evidence-based treatments, resulting in improved survival outcomes, quality of life, and preventive strategies.

While it is not possible to provide a comprehensive and exhaustive review of all of the advances, we hope to highlight many of the notable advances in this article.Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide with 528,000 new cases in 2012. The majority of cervical cancer cases are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). While the standard therapies for cervical cancer have been long established (radical hysterectomy for stage I and radiation therapy for locally advanced disease), one of the most significant advances in the past 50 years was the addition of radiation-sensitizing chemotherapy (cisplatin) administered concurrently with radiation therapy.

In randomized trials in both early and advanced cervical cancer, the risk of death was reduced by 30%-50%. These studies changed the paradigm for the treatment of cervical cancer (N Engl J Med. 1999 Apr 15;340[15]:1137-43; N Engl J Med. 1999 Apr 15;340[15]:1144-53; J Clin Oncol. 2000 Apr;18[8]:1606-13).

Future studies evaluating biologic adjuncts or additional chemotherapy are currently underway or awaiting data maturation.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) highlighted the “Top 5 advances in 50 years of Modern Oncology” in 2014, and second on the list was the approval of the HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer. Vaccines have been developed that can protect against types 2, 4 or 9 of HPV. In a 2014 study, depending on vaccination coverage, the relative number of cervical cancer cases avoided was 34% in Africa, 27% for America, 26% for Asia, 21% for Europe, and worldwide was estimated at 27% (Vaccine. 2014 Feb 3;32[6]:733-9).

While the benefit from HPV vaccination has been proven, in the United States, only about a third of eligible girls and women have been vaccinated. Efforts should focus on expanding vaccination penetration to eligible girls, boys, women, and men.

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States with an estimated 54,870 cases and 10,170 deaths annually. Notable advances in the management of women with endometrial cancer have arisen because of a better understanding that there are two types of endometrial cancer – type I and type II.

The type I endometrial cancers tend to be associated with lower stage of disease at the time of diagnosis and fewer recurrences, while type II endometrial cancer is associated with worse outcomes.

Tailoring the surgical approaches and adjuvant therapy for women with endometrial cancer has led to improved outcomes. The GOG conducted a large prospective randomized trial of laparotomy versus laparoscopic surgical staging for women with clinical early-stage endometrial cancer (LAP2). Laparoscopy was associated with improved perioperative outcomes and was found to be noninferior to laparotomy with regards to survival outcomes (J Clin Oncol. 2012 Mar 1;30[7]:695-700). Therefore, minimally invasive surgery has become widely accepted for the surgical staging of women with endometrial cancer.

Appropriate surgical staging allows for tailoring of postoperative adjuvant therapy. The current evidence suggests that vaginal brachytherapy should be the adjuvant treatment of choice over whole pelvic radiation in women with early-stage endometrial cancer (Lancet. 2010 Mar 6;375[9717]:816-23). Studies are underway to evaluate the role of both adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy in women with early-stage type II endometrial cancer who are felt to be at high risk for recurrent disease, as well as how to improve on the therapeutic options for women with advanced or recurrent disease.

Ovarian cancer

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most deadly gynecologic malignancy in the United States with 21,290 cases and 14,180 deaths in 2015. The concept of ovarian tumor debulking was first described by Dr. Joe Meigs in 1934, but did not gain traction until the mid-1970s when Dr. C. Thomas Griffiths published his work (Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1975 Oct;42:101-4).

While there are no randomized trials proving that surgical cytoreduction improves overall survival, most retrospective studies support this concept. In 2009, Chi et al. showed improved median survival in women with ovarian cancer based on the increased percentage of women who underwent optimal cytoreduction (Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jul;114[1]:26-31). This has led to modifications of surgical techniques and surgical goals with an effort to maximally cytoreduce all of the visible disease.

While initial surgical debulking is the goal, there are circumstances when a different approach may be indicated. Vergote et al. conducted a prospective randomized trial of 670 women with advanced ovarian cancer. In this study, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking was not inferior to primary debulking followed by chemotherapy with regards to progression-free survival and overall survival. However, initial surgery was associated with increased surgical complications and perioperative mortality as compared with interval surgery. Therefore, in women who are not felt to be candidates for optimal cytoreduction, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval surgery may be an appropriate treatment strategy (N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 2;363[10]:943-53.).

There have been several notable advances and a series of randomized trials – predominately conducted by the GOG – that have resulted in improved overall survival and progression-free interval in women with ovarian cancer. However, none are as significant as the discovery of paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy (cisplatin and carboplatin).

In 1962, samples of the Pacific Yew’s bark were collected and, 2 years later, the extracts from this bark were found to have cytotoxic activity. There were initial difficulties suspending the drug in solution; however, ultimately a formulation in ethanol, cremophor, and saline was found to be effective. In 1984, the National Cancer Institute began clinical trials of paclitaxel and it was found to be highly effective in ovarian cancer. In 1992, it was approved for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Cisplatin was approved in 1978. Carboplatin entered clinical trials in 1982 and was approved for women with recurrent ovarian cancer in 1989.

There were a series of trials beginning in the late 1980s that established the role of platinum agents and led us to GOG 111. This trial evaluated cisplatin with either cyclophosphamide or paclitaxel. The paclitaxel combination was superior and in 2003 two trials were published that solidified carboplatin and paclitaxel as the cornerstone in the treatment of women with ovarian cancer (J Clin Oncol. 2003 Sep 1;21[17]:3194-200; J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Sep 3;95[17]:1320-9).

What has most recently been debated is the route and schedule for both paclitaxel and the platinum agents. In January 2006, the National Cancer Institute released a Clinical Announcement regarding the role of intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy for the treatment of women with optimally debulked ovarian cancer. Of the six trials included in the announcement, four trials showed a benefit for progression-free survival and five studies showed an improvement in overall survival. Armstrong et al (GOG 172) showed a 16-month improvement in overall survival with intravenous (IV) paclitaxel, IP cisplatin, and IP paclitaxel. IP chemotherapy has not been universally embraced by physicians and patients in part because of its toxicity, treatment schedule, and the fact that no IP regimen has been compared with the current standard of IV carboplatin and paclitaxel (N Engl J Med. 2006 Jan 5;354[1]:34-43).

While there have been improvements in 5-year survival over time, most women with advanced ovarian cancer will undergo additional chemotherapy in order to achieve subsequent remissions or maintain stability of disease. Other drugs that have Food and Drug Administration approval in the setting of recurrent ovarian cancer include topotecan, liposomal doxorubicin, gemcitabine, bevacizumab, altretamine, carboplatin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, and melphalan. Olaparib was recently approved as monotherapy in women with a germline BRCA-mutation who had received three or more prior lines of chemotherapy.

Minimally invasive surgery

Over the last 30 years, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in gynecologic oncology, particularly for endometrial cancer, has gone from a niche procedure to the standard of care. The introduction of laparoscopy into gynecologic oncology started in the early 1990s. In a series of 59 women undergoing laparoscopy for endometrial cancer, Childers et al. demonstrated feasibility of the technique and low laparotomy conversion rates (Gynecol Oncol. 1993 Oct;51[1]:33-8.). The GOG trial, LAP2, supported the equivalent oncologic outcomes of MIS versus laparotomy for the treatment of endometrial cancer. While many surgeons and centers offered laparoscopic surgery, there were issues with the learning curve that limited its widespread use.

In 2005, the FDA approval of the robotic platform for gynecologic surgery resulted in at least a doubling of the proportion of endometrial cancer patients treated with MIS (Int J Med Robot. 2009 Dec;5[4]:392-7.). In 2012, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology published a consensus statement regarding robotic-assisted surgery in gynecologic oncology (Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Feb;124[2]:180-4.). This review highlights the advantages of the robotics platform with regards to expanding MIS to women with cervical and ovarian cancer; the improvements in outcomes in the obese woman with endometrial cancer; and that the learning curve for robotic surgery is shorter than for traditional laparoscopy. Issues requiring further research include cost analysis as the cost of the new technology decreases, and opportunities for improvement in patient and physician quality of life.

Sentinel node mapping

The rationale for sentinel node mapping is that if one or more sentinel lymph nodes is/are negative for malignancy, then the other regional lymph nodes will also be negative. This would thereby avoid the need for a complete lymph node dissection and its resultant complications, including chronic lymphedema. Much of the work pioneering this strategy has been in breast cancer and melanoma, but data are rapidly emerging for these techniques in gynecologic malignancies.

Candidates for sentinel lymph node biopsy for vulvar cancer include those with a lesion more than 1mm in depth, a tumor less than 4 cm in size, and no obvious metastatic disease on exam or preoperative imaging. Additionally, recommendations have been made regarding case volume in order to achieve limited numbers of false-negative results and to maintain competency. In the study by Van der Zee et al. of 403 patients (623 groins) who underwent sentinel node procedures, the false-negative rate was 0-2%. The overall survival rate was 97% at 3 years (J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 20;26[6]:884-9). However, a more recent data from the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG 173) showed a slightly higher false-negative rate of 8% (J Clin Oncol. 2012 Nov 1;30[31]:3786-91). Overall survival data are pending from this study.

While sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer has been feasible for many years and has been well described, the questioned role of completed lymphadenectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer has led to a resurgence of interest in these techniques. While blue dye and radiolabeled tracer methods have historically been the most popular mapping solutions, the advent of endoscopic near-infrared imaging, with its higher sensitivity and good depth penetration, has added options. Indocyanine green fluorescence can be easily detected during robotic surgery and as experience with these techniques increase, successful mapping and sensitivity will increase.

Genetics

While hereditary cancer syndromes have been recognized for many years, detecting the genetic mutations that may increase an individual’s risk of developing a malignancy were not elucidated until the early 1990s. In gynecologic oncology, the most commonly encountered syndromes involve mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and hereditary non–polyposis colorectal cancer, which causes mutations in DNA mismatch-repair genes and increase the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer.

The SGO recently published a statement on risk assessment for inherited gynecologic cancer predispositions. In this statement “the evaluation for the presence of a hereditary cancer syndrome enables physicians to provide individualized and quantified assessment of cancer risk, as well as options for tailored screening and preventions strategies that may reduce morbidity associated with the development of malignancy” (Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Jan;136[1]:3-7). Beyond risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, therapeutic strategies targeting patients with germline mutations have been developed (PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated women with ovarian cancer).

In August 2015, ASCO released an updated policy statement on genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility and highlighted five key areas: germ-line implications of somatic mutation profiling; multigene panel testing for cancer susceptibility; quality assurance in genetic testing; education for oncology professionals; and access to cancer genetic services.

Antiemetics

Rounding out ASCO’s “Top 5 advances in 50 years of Modern Oncology” was the improvement in patients’ quality of life from supportive therapies, in particular antinausea medications.

Several of the agents commonly used in gynecologic oncology rate high (cisplatin) to moderate (carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, ifosfamide) with regards to emetogenicity. The advent of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (for example, ondansetron) has significantly improved the quality of life of patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. In addition to improving quality of life, the decrease in nausea and vomiting can also decrease life-threatening complications such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Both ASCO and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network both have guidelines for the management of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Throughout 2016, Ob.Gyn. News will celebrate its 50th anniversary with exclusive articles looking at the evolution of the specialty, including the history of contraception, changes in gynecologic surgery, and the transformation of the well-woman visit. Look for these articles and more special features in the pages of Ob.Gyn. News and online at obgynnews.com.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Fertility preservation in early cervical cancer

Historically, the standard of care for women diagnosed with early cervical cancer has been radical hysterectomy. Thus, young women are not only being confronted with a cancer diagnosis, but may also be forced to cope with the loss of their fertility.

As many young women with cervical cancer were not accepting of this treatment, Dr. Daniel Dargent pioneered the vaginal radical trachelectomy as a fertility-preserving treatment option for early cervical cancer in 1994. There have now been more than 900 vaginal radical trachelectomies performed and they have been shown to have oncologic outcomes similar to those of traditional radical hysterectomy, while sparing a woman’s fertility (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Jul;23[6]:982-9).

Obstetric outcomes following vaginal radical trachelectomy are acceptable with 17% miscarriage rate in the first trimester (compared to 10%-20% in the general population) and 8% in the second trimester (compared to 1%-5% in the general population) (Am Fam Physician. 2007 Nov 1;76[9]:1341-6). Following vaginal radical trachelectomy, 64% of pregnancies deliver at term.

The usual criteria required to undergo radical trachelectomy include:

1) Reproductive age with desire for fertility.

2) Stage IA1 with LVSI (lymphovascular space invasion), IA2, or IB1 with tumor less than 2 cm.

3) Limited endocervical involvement via preoperative MRI.

4) Negative pelvic lymph nodes.

Preoperative PET scan can be used to evaluate nodal status, but suspicious lymph nodes should be evaluated on frozen section at the time of surgery. The presence of LVSI alone is not a contraindication to trachelectomy.

A key limitation of vaginal radical trachelectomy is the specialized training required to perform this technically challenging procedure. Few surgeons in the United States are trained to perform vaginal radical trachelectomy. In response to this limitation, surgeons began to attempt radical trachelectomy via laparotomy (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 Dec;103[3]:807-13). Oncologic outcomes following fertility-sparing abdominal radical trachelectomy have been reported to be equivalent to radical hysterectomy. Concerns regarding the abdominal approach to radical trachelectomy include higher rates of second trimester loss (19%) when compared to the vaginal approach (8%), higher rate of loss of fertility (30%), and risk of postoperative adhesions.

The advent of minimally invasive surgery, particularly robotic surgery, now offers surgeons the ability to perform a procedure technically similar to radical hysterectomy using a minimally invasive approach. Given the similarity of procedural steps of radical trachelectomy to radical hysterectomy using the robotic platform, this procedure is gaining acceptance in the United States with an associated improved surgeon learning curve (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Nov;111[2]:255-60). In addition, the use of minimally invasive surgery should result in less adhesion formation facilitating natural fertility options postoperatively.

Obstetric and fertility outcomes are limited following minimally invasive radical trachelectomy via laparoscopy or robotic surgery given the novelty of this procedure. Emerging obstetric outcomes appear reassuring, but further data are needed to fully understand the effects of this procedure on pregnancy outcomes and the need for assisted reproductive techniques to achieve pregnancy.

The management of pregnancies following radical trachelectomy is also an area with limited data, which presents a clinical challenge to obstetricians. Many gynecologic oncologists perform a permanent cerclage at the time of trachelectomy and recommend delivery via scheduled cesarean at term for all subsequent pregnancies prior to labor (usually 37-38 weeks).

At our institution, we recommend the use of progesterone from 16 to 36 weeks despite no clear evidence on the role of progesterone in this setting. Maternal-fetal medicine consultation should be considered to either follow these patients during their pregnancies or to perform a single consultative visit to guide antepartum care.

Some have advocated for less radical surgery, such as simple trachelectomy or large cold knife conization, as the risk of parametrial extension in these patients is low (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Dec;123[3]:557-60). More data are needed to determine if this is a safe approach. Further, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cold knife conization for fertility preservation in women with larger tumors has been proposed. This may be a feasible option in women with chemo-sensitive tumors, but progression on chemotherapy and increased recurrences have been reported with this approach (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Dec;111[3]:438-43).

Women of reproductive age diagnosed with early cervical cancer now have multiple options for fertility preservation. Ongoing research regarding obstetric and fertility outcomes is needed; however, oncologic outcomes appear to be equivalent.

Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Boggess is an expert in robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology and is a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Historically, the standard of care for women diagnosed with early cervical cancer has been radical hysterectomy. Thus, young women are not only being confronted with a cancer diagnosis, but may also be forced to cope with the loss of their fertility.

As many young women with cervical cancer were not accepting of this treatment, Dr. Daniel Dargent pioneered the vaginal radical trachelectomy as a fertility-preserving treatment option for early cervical cancer in 1994. There have now been more than 900 vaginal radical trachelectomies performed and they have been shown to have oncologic outcomes similar to those of traditional radical hysterectomy, while sparing a woman’s fertility (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Jul;23[6]:982-9).

Obstetric outcomes following vaginal radical trachelectomy are acceptable with 17% miscarriage rate in the first trimester (compared to 10%-20% in the general population) and 8% in the second trimester (compared to 1%-5% in the general population) (Am Fam Physician. 2007 Nov 1;76[9]:1341-6). Following vaginal radical trachelectomy, 64% of pregnancies deliver at term.

The usual criteria required to undergo radical trachelectomy include:

1) Reproductive age with desire for fertility.

2) Stage IA1 with LVSI (lymphovascular space invasion), IA2, or IB1 with tumor less than 2 cm.

3) Limited endocervical involvement via preoperative MRI.

4) Negative pelvic lymph nodes.

Preoperative PET scan can be used to evaluate nodal status, but suspicious lymph nodes should be evaluated on frozen section at the time of surgery. The presence of LVSI alone is not a contraindication to trachelectomy.

A key limitation of vaginal radical trachelectomy is the specialized training required to perform this technically challenging procedure. Few surgeons in the United States are trained to perform vaginal radical trachelectomy. In response to this limitation, surgeons began to attempt radical trachelectomy via laparotomy (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 Dec;103[3]:807-13). Oncologic outcomes following fertility-sparing abdominal radical trachelectomy have been reported to be equivalent to radical hysterectomy. Concerns regarding the abdominal approach to radical trachelectomy include higher rates of second trimester loss (19%) when compared to the vaginal approach (8%), higher rate of loss of fertility (30%), and risk of postoperative adhesions.

The advent of minimally invasive surgery, particularly robotic surgery, now offers surgeons the ability to perform a procedure technically similar to radical hysterectomy using a minimally invasive approach. Given the similarity of procedural steps of radical trachelectomy to radical hysterectomy using the robotic platform, this procedure is gaining acceptance in the United States with an associated improved surgeon learning curve (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Nov;111[2]:255-60). In addition, the use of minimally invasive surgery should result in less adhesion formation facilitating natural fertility options postoperatively.

Obstetric and fertility outcomes are limited following minimally invasive radical trachelectomy via laparoscopy or robotic surgery given the novelty of this procedure. Emerging obstetric outcomes appear reassuring, but further data are needed to fully understand the effects of this procedure on pregnancy outcomes and the need for assisted reproductive techniques to achieve pregnancy.

The management of pregnancies following radical trachelectomy is also an area with limited data, which presents a clinical challenge to obstetricians. Many gynecologic oncologists perform a permanent cerclage at the time of trachelectomy and recommend delivery via scheduled cesarean at term for all subsequent pregnancies prior to labor (usually 37-38 weeks).

At our institution, we recommend the use of progesterone from 16 to 36 weeks despite no clear evidence on the role of progesterone in this setting. Maternal-fetal medicine consultation should be considered to either follow these patients during their pregnancies or to perform a single consultative visit to guide antepartum care.

Some have advocated for less radical surgery, such as simple trachelectomy or large cold knife conization, as the risk of parametrial extension in these patients is low (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Dec;123[3]:557-60). More data are needed to determine if this is a safe approach. Further, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cold knife conization for fertility preservation in women with larger tumors has been proposed. This may be a feasible option in women with chemo-sensitive tumors, but progression on chemotherapy and increased recurrences have been reported with this approach (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Dec;111[3]:438-43).

Women of reproductive age diagnosed with early cervical cancer now have multiple options for fertility preservation. Ongoing research regarding obstetric and fertility outcomes is needed; however, oncologic outcomes appear to be equivalent.

Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Boggess is an expert in robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology and is a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.