User login

Ovarian cancer screening update

Ovarian cancer remains the most deadly gynecologic malignancy in the United States with more than 14,000 deaths in 2016. Yet, the prevalence remains low with approximately 22,000 cases in 2016. Stage at diagnosis is one of the strongest predictors of overall survival. The 5-year overall survival is more than 90% with stage I disease; this drops to 25% for those with distant metastases. Unfortunately, three-quarters of patients have disease spread beyond the ovary at the time ovarian cancer is clinically identified.

In this update, we will review:

• The fundamentals of ovarian cancer screening.

• How to identify patients who would benefit from surveillance.

• The usefulness of tumor markers.

• The results from recent large ovarian cancer screening trials.

Screening is a critical part of secondary prevention through early disease detection, when patients are asymptomatic and treatment can stop progression. Core principles of a good screening test are that the test is noninvasive, tolerable to the patient, and not costly. The disease should pose a major health threat and be detected at a stage at which intervention can impart a survival advantage. Most critically, the test should be sensitive and specific (i.e., detect disease when it is truly present and rarely be positive in the absence of disease).

Screening vs. case finding

A significant distinction should be made between average-risk patients and high-risk patients. Ob.gyns. frequently encounter high-risk patients who would benefit from regular surveillance or case finding (for example, patients with BRCA deleterious mutations or with Lynch syndrome). There are multiple risk factors for ovarian cancer, but the strongest known is family history, which is present in 15% of ovarian cancer patients. Having one relative with ovarian cancer increases the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer up to 5%. When a patient reports having one or more family members with ovarian cancer, it is important to differentiate between a common sporadic presentation and a rare familial cancer syndrome. ACOG Practice Bulletin 103 provides excellent guidance on which patients warrant formal genetic risk assessments by a genetic counselor.2

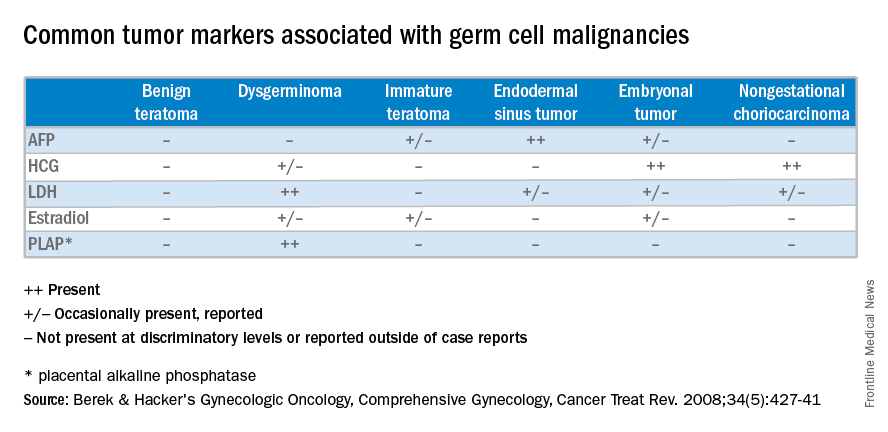

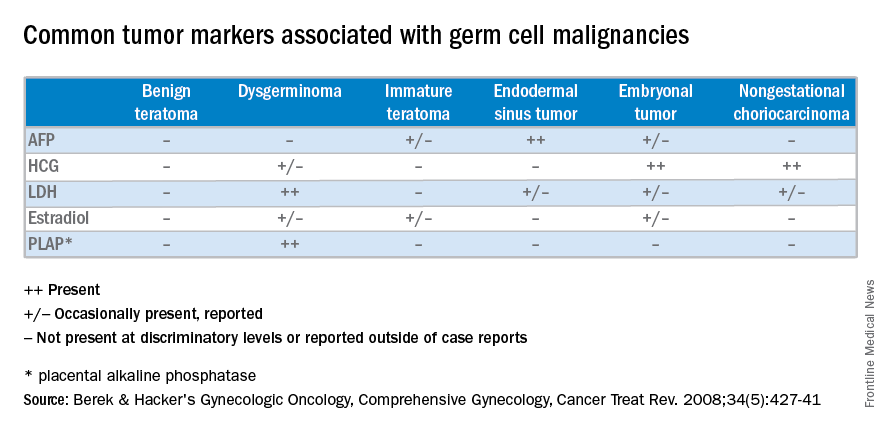

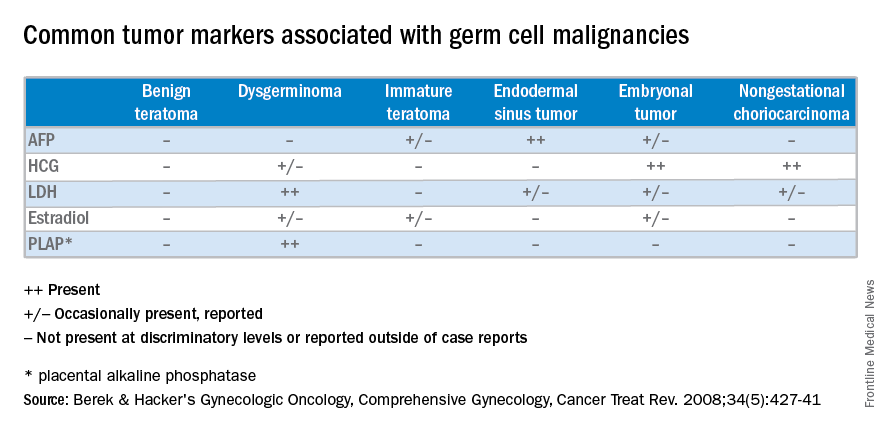

Tumor markers

During the last 25 years, screening for ovarian cancer in an average-risk population has been evaluated in multiple large prospective studies using serum tumor markers (i.e., CA 125) and ultrasound results.

CA 125 and HE4 tumor markers are frequently elevated in ovarian cancer and have been studied in ovarian cancer screening. However, while having a high sensitivity for detecting disease, they are nonspecific because they are also elevated in numerous benign conditions and therefore have not proven to be a useful screening tool in the average-risk population. There are clinically available tumor marker panels that are not intended for screening. Rather, they clarify the uncertainty of the presurgical adnexal mass evaluation by providing a risk score. High risk scores are generally managed in conjunction with a gynecologic oncology referral.

Multimodal screening

Combined assessment of both ultrasound findings and tumor marker levels shows more promise with respect to prediction of ovarian cancer. However, a systematic review of 25 ovarian cancer screening studies concluded that screening low-risk populations should not be included in clinical practice until randomized trials assessed the effect on mortality and the risk of adverse events. Three large randomized controlled trials have been completed to date.3,4,5

The U.K. Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) results appear promising. However, the revealing analysis was post hoc since the original study design did not take into account the inherent delayed effect in screening studies. While these results may provide a basis for future successful screening for ovarian cancer, confirmatory further analysis is pending, using additional data over a period of the next 3 years.

Ultimately, we are all excited about the possibility of effective screening protocols for ovarian cancer and await completed analyses of UKCTOCS. Until their benefits are confirmed, screening and preventive measures should be limited to those at high risk for ovarian cancer.

References

1. Hippokratia. 2007 Apr;11(2):63-6.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Apr;113(4):957-66.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;193(5):1630-9.

4. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008 May-Jun;18(3):414-20.

5. Lancet. 2016 Mar 5;387(10022):945-56.

Dr. Pierce is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Ovarian cancer remains the most deadly gynecologic malignancy in the United States with more than 14,000 deaths in 2016. Yet, the prevalence remains low with approximately 22,000 cases in 2016. Stage at diagnosis is one of the strongest predictors of overall survival. The 5-year overall survival is more than 90% with stage I disease; this drops to 25% for those with distant metastases. Unfortunately, three-quarters of patients have disease spread beyond the ovary at the time ovarian cancer is clinically identified.

In this update, we will review:

• The fundamentals of ovarian cancer screening.

• How to identify patients who would benefit from surveillance.

• The usefulness of tumor markers.

• The results from recent large ovarian cancer screening trials.

Screening is a critical part of secondary prevention through early disease detection, when patients are asymptomatic and treatment can stop progression. Core principles of a good screening test are that the test is noninvasive, tolerable to the patient, and not costly. The disease should pose a major health threat and be detected at a stage at which intervention can impart a survival advantage. Most critically, the test should be sensitive and specific (i.e., detect disease when it is truly present and rarely be positive in the absence of disease).

Screening vs. case finding

A significant distinction should be made between average-risk patients and high-risk patients. Ob.gyns. frequently encounter high-risk patients who would benefit from regular surveillance or case finding (for example, patients with BRCA deleterious mutations or with Lynch syndrome). There are multiple risk factors for ovarian cancer, but the strongest known is family history, which is present in 15% of ovarian cancer patients. Having one relative with ovarian cancer increases the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer up to 5%. When a patient reports having one or more family members with ovarian cancer, it is important to differentiate between a common sporadic presentation and a rare familial cancer syndrome. ACOG Practice Bulletin 103 provides excellent guidance on which patients warrant formal genetic risk assessments by a genetic counselor.2

Tumor markers

During the last 25 years, screening for ovarian cancer in an average-risk population has been evaluated in multiple large prospective studies using serum tumor markers (i.e., CA 125) and ultrasound results.

CA 125 and HE4 tumor markers are frequently elevated in ovarian cancer and have been studied in ovarian cancer screening. However, while having a high sensitivity for detecting disease, they are nonspecific because they are also elevated in numerous benign conditions and therefore have not proven to be a useful screening tool in the average-risk population. There are clinically available tumor marker panels that are not intended for screening. Rather, they clarify the uncertainty of the presurgical adnexal mass evaluation by providing a risk score. High risk scores are generally managed in conjunction with a gynecologic oncology referral.

Multimodal screening

Combined assessment of both ultrasound findings and tumor marker levels shows more promise with respect to prediction of ovarian cancer. However, a systematic review of 25 ovarian cancer screening studies concluded that screening low-risk populations should not be included in clinical practice until randomized trials assessed the effect on mortality and the risk of adverse events. Three large randomized controlled trials have been completed to date.3,4,5

The U.K. Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) results appear promising. However, the revealing analysis was post hoc since the original study design did not take into account the inherent delayed effect in screening studies. While these results may provide a basis for future successful screening for ovarian cancer, confirmatory further analysis is pending, using additional data over a period of the next 3 years.

Ultimately, we are all excited about the possibility of effective screening protocols for ovarian cancer and await completed analyses of UKCTOCS. Until their benefits are confirmed, screening and preventive measures should be limited to those at high risk for ovarian cancer.

References

1. Hippokratia. 2007 Apr;11(2):63-6.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Apr;113(4):957-66.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;193(5):1630-9.

4. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008 May-Jun;18(3):414-20.

5. Lancet. 2016 Mar 5;387(10022):945-56.

Dr. Pierce is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Ovarian cancer remains the most deadly gynecologic malignancy in the United States with more than 14,000 deaths in 2016. Yet, the prevalence remains low with approximately 22,000 cases in 2016. Stage at diagnosis is one of the strongest predictors of overall survival. The 5-year overall survival is more than 90% with stage I disease; this drops to 25% for those with distant metastases. Unfortunately, three-quarters of patients have disease spread beyond the ovary at the time ovarian cancer is clinically identified.

In this update, we will review:

• The fundamentals of ovarian cancer screening.

• How to identify patients who would benefit from surveillance.

• The usefulness of tumor markers.

• The results from recent large ovarian cancer screening trials.

Screening is a critical part of secondary prevention through early disease detection, when patients are asymptomatic and treatment can stop progression. Core principles of a good screening test are that the test is noninvasive, tolerable to the patient, and not costly. The disease should pose a major health threat and be detected at a stage at which intervention can impart a survival advantage. Most critically, the test should be sensitive and specific (i.e., detect disease when it is truly present and rarely be positive in the absence of disease).

Screening vs. case finding

A significant distinction should be made between average-risk patients and high-risk patients. Ob.gyns. frequently encounter high-risk patients who would benefit from regular surveillance or case finding (for example, patients with BRCA deleterious mutations or with Lynch syndrome). There are multiple risk factors for ovarian cancer, but the strongest known is family history, which is present in 15% of ovarian cancer patients. Having one relative with ovarian cancer increases the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer up to 5%. When a patient reports having one or more family members with ovarian cancer, it is important to differentiate between a common sporadic presentation and a rare familial cancer syndrome. ACOG Practice Bulletin 103 provides excellent guidance on which patients warrant formal genetic risk assessments by a genetic counselor.2

Tumor markers

During the last 25 years, screening for ovarian cancer in an average-risk population has been evaluated in multiple large prospective studies using serum tumor markers (i.e., CA 125) and ultrasound results.

CA 125 and HE4 tumor markers are frequently elevated in ovarian cancer and have been studied in ovarian cancer screening. However, while having a high sensitivity for detecting disease, they are nonspecific because they are also elevated in numerous benign conditions and therefore have not proven to be a useful screening tool in the average-risk population. There are clinically available tumor marker panels that are not intended for screening. Rather, they clarify the uncertainty of the presurgical adnexal mass evaluation by providing a risk score. High risk scores are generally managed in conjunction with a gynecologic oncology referral.

Multimodal screening

Combined assessment of both ultrasound findings and tumor marker levels shows more promise with respect to prediction of ovarian cancer. However, a systematic review of 25 ovarian cancer screening studies concluded that screening low-risk populations should not be included in clinical practice until randomized trials assessed the effect on mortality and the risk of adverse events. Three large randomized controlled trials have been completed to date.3,4,5

The U.K. Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) results appear promising. However, the revealing analysis was post hoc since the original study design did not take into account the inherent delayed effect in screening studies. While these results may provide a basis for future successful screening for ovarian cancer, confirmatory further analysis is pending, using additional data over a period of the next 3 years.

Ultimately, we are all excited about the possibility of effective screening protocols for ovarian cancer and await completed analyses of UKCTOCS. Until their benefits are confirmed, screening and preventive measures should be limited to those at high risk for ovarian cancer.

References

1. Hippokratia. 2007 Apr;11(2):63-6.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Apr;113(4):957-66.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;193(5):1630-9.

4. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008 May-Jun;18(3):414-20.

5. Lancet. 2016 Mar 5;387(10022):945-56.

Dr. Pierce is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Preventing surgical site infections in hysterectomy

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

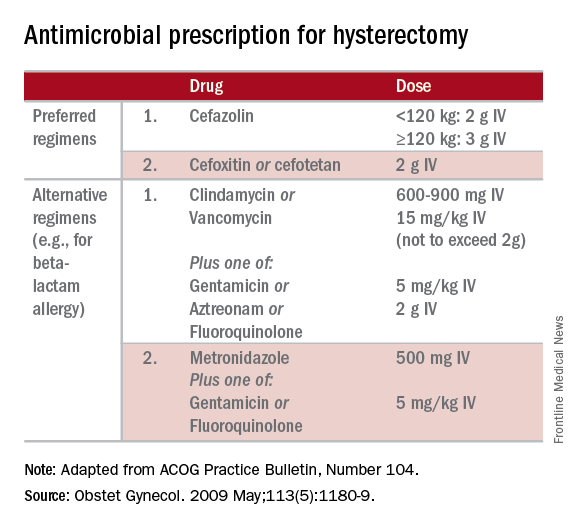

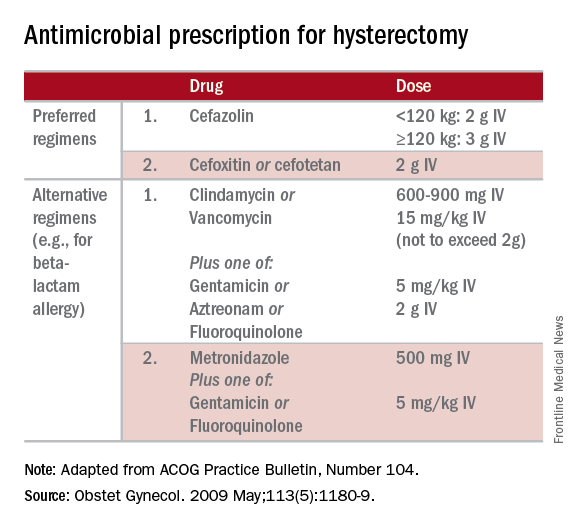

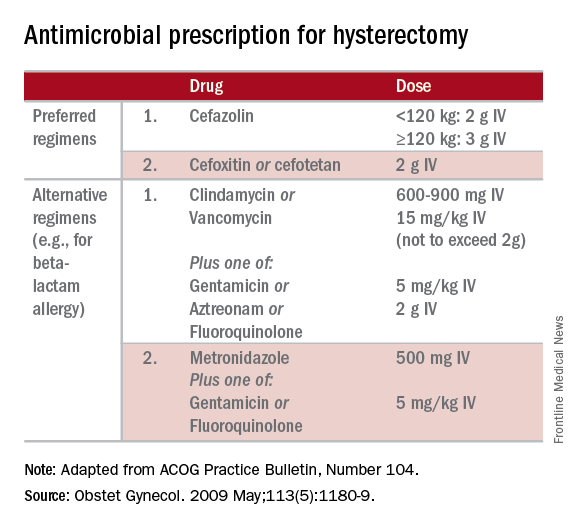

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

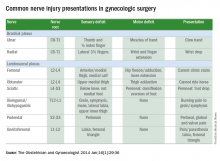

Tips for avoiding nerve injuries in gynecologic surgery

Upper- and lower-extremity injuries can occur during gynecologic surgery. The incidence of lower-extremity injury is 1.1%-1.9% and upper-extremity injuries can occur in 0.16% of cases.1-5 Fortunately, most of the injuries are transient, sensory injuries that resolve spontaneously. However, a small percentage of injuries result in long-term sequelae.

The pathophysiology of the nerve injuries can be mechanistically separated into three categories: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia results from nerve demyelination at the site of injury because of compression and typically resolves within weeks to months as the nerve is remyelinated. Axonotmesis results from severe compression with axon damage. This may take up to a year to resolve as axonal regeneration proceeds at the rate of 1 mm per day. This can be separated into second and third degree and refers to the severity of damage and the resultant persistent deficit. Neurotmesis results from complete transection and is associated with a poor prognosis without reparative surgery.

Brachial plexus

Stretch injury is the most common reason for a brachial plexus injury. This can occur if the arm board is extended to greater than 90 degrees from the patient’s torso or if the patient’s arm falls off of the arm board. Careful positioning and securing the patient’s arm on the arm board before draping can avoid this injury. A brachial plexus injury can also occur if shoulder braces are placed too laterally during minimally invasive surgery. Radial nerve injuries can occur if there is too much pressure on the humerus during positioning. Ulnar injuries arise from pressure placed on the medial aspect of the elbow.

Tip #1: When tucking a patient’s arm for minimally invasive surgery, appropriate padding should be placed around the elbow and wrist, and the arm should be in the “thumbs-up” position.

Tip #2: Shoulder blocks should be placed over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Lumbosacral plexus

The femoral nerve is the nerve most commonly injured during gynecologic surgery and this usually occurs because of compression of the nerve from the lateral blades of self-retaining retractors. One study showed an 8% incidence of injury from self-retaining retractors, compared with less than 1% when the retractors were not used.6 The femoral nerve can also be stretched when patients are placed in the lithotomy position and the hip is hyperflexed.

As with brachial injury prevention, patients should be positioned prior to draping and care must be taken to not hyperflex or externally rotate the hip during minimally invasive surgical procedures. With the introduction of robot-assisted surgery, care must be taken when docking the robot and surgeons must resist excessive movement of the stirrups.

Tip #3: During laparotomy, surgeons should use the shortest blades that allow for adequate visualization and check the blades during the procedure to ensure that excessive pressure is not placed on the psoas muscle. Consider intermittently releasing the pressure on the lateral blades during other portions of the procedure.

Tip #4: Make sure the stirrups are at the same height and that the leg is in line with the patient’s contralateral shoulder.

Obturator nerve injuries can occur during retroperitoneal dissection for pelvic lymphadenectomy (obturator nodes) and can be either a transection or a cautery injury. It can also be injured during urogynecologic procedures including paravaginal defect repairs and during the placement of transobturator tapes.

The sciatic nerve and its branch, the common peroneal, are generally injured because of excessive stretch or pressure. Both nerves can be injured from hyperflexion of the thigh and the common peroneal can suffer a pressure injury as it courses around the lateral head of the fibula. Therefore, care during lithotomy positioning with both candy cane and Allen stirrups is critical during vaginal surgery.

Tip #5: Ensure that the lateral fibula is not touching the stirrup or that padding is placed between the fibular head and the stirrup.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are typically injured via suture entrapment from low transverse skin incisions, though laparoscopic injury has also been reported. The incidence after a Pfannenstiel incision is about 3.7%.7

Tip #6: Avoid extending the low transverse incision beyond the lateral margin of the rectus muscle, and do not extend the fascial closure suture more than 1.5 cm from the lateral edge of the fascial incision to avoid catching the nerve with the suture.

The pudendal nerve is most commonly injured during vaginal procedures such as sacrospinous fixation. Pain is typically worse when seated.

The genitofemoral nerve is typically injured during retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, particularly the external iliac nodes. The nerve is small and runs lateral to the external iliac artery. It can suffer cautery and transection injuries. Usually, the paresthesias over the mons pubis, labia majora, and medial inner thigh are temporary.

Tip #7: Care should be taken to identify and spare the nerve during retroperitoneal dissection or external iliac node removal.

Nerve injuries during gynecologic surgery are common and are a significant cause of potential morbidity. While occasionally unavoidable and inherent to the surgical procedure, many times the injury could be prevented with proper attention and care to patient positioning and retractor use. Gynecologists should be aware of the risks and have a through understanding of the anatomy. However, should an injury occur, the patient can be reassured that most are self-limited and full recovery is generally expected. In a prospective study, the median time to resolution of symptoms was 31.5 days (range, 1 day to 6 months).5

References

1. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2014;16:29-36.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 1988 Nov;31(3):462-6.

3. Fertil Steril. 1993 Oct;60(4):729-32.

4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):664-72.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;201(5):531.e1-7.

6. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985 Dec;20(6):385-92.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):839-46.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email her at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Upper- and lower-extremity injuries can occur during gynecologic surgery. The incidence of lower-extremity injury is 1.1%-1.9% and upper-extremity injuries can occur in 0.16% of cases.1-5 Fortunately, most of the injuries are transient, sensory injuries that resolve spontaneously. However, a small percentage of injuries result in long-term sequelae.

The pathophysiology of the nerve injuries can be mechanistically separated into three categories: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia results from nerve demyelination at the site of injury because of compression and typically resolves within weeks to months as the nerve is remyelinated. Axonotmesis results from severe compression with axon damage. This may take up to a year to resolve as axonal regeneration proceeds at the rate of 1 mm per day. This can be separated into second and third degree and refers to the severity of damage and the resultant persistent deficit. Neurotmesis results from complete transection and is associated with a poor prognosis without reparative surgery.

Brachial plexus

Stretch injury is the most common reason for a brachial plexus injury. This can occur if the arm board is extended to greater than 90 degrees from the patient’s torso or if the patient’s arm falls off of the arm board. Careful positioning and securing the patient’s arm on the arm board before draping can avoid this injury. A brachial plexus injury can also occur if shoulder braces are placed too laterally during minimally invasive surgery. Radial nerve injuries can occur if there is too much pressure on the humerus during positioning. Ulnar injuries arise from pressure placed on the medial aspect of the elbow.

Tip #1: When tucking a patient’s arm for minimally invasive surgery, appropriate padding should be placed around the elbow and wrist, and the arm should be in the “thumbs-up” position.

Tip #2: Shoulder blocks should be placed over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Lumbosacral plexus

The femoral nerve is the nerve most commonly injured during gynecologic surgery and this usually occurs because of compression of the nerve from the lateral blades of self-retaining retractors. One study showed an 8% incidence of injury from self-retaining retractors, compared with less than 1% when the retractors were not used.6 The femoral nerve can also be stretched when patients are placed in the lithotomy position and the hip is hyperflexed.

As with brachial injury prevention, patients should be positioned prior to draping and care must be taken to not hyperflex or externally rotate the hip during minimally invasive surgical procedures. With the introduction of robot-assisted surgery, care must be taken when docking the robot and surgeons must resist excessive movement of the stirrups.

Tip #3: During laparotomy, surgeons should use the shortest blades that allow for adequate visualization and check the blades during the procedure to ensure that excessive pressure is not placed on the psoas muscle. Consider intermittently releasing the pressure on the lateral blades during other portions of the procedure.

Tip #4: Make sure the stirrups are at the same height and that the leg is in line with the patient’s contralateral shoulder.

Obturator nerve injuries can occur during retroperitoneal dissection for pelvic lymphadenectomy (obturator nodes) and can be either a transection or a cautery injury. It can also be injured during urogynecologic procedures including paravaginal defect repairs and during the placement of transobturator tapes.

The sciatic nerve and its branch, the common peroneal, are generally injured because of excessive stretch or pressure. Both nerves can be injured from hyperflexion of the thigh and the common peroneal can suffer a pressure injury as it courses around the lateral head of the fibula. Therefore, care during lithotomy positioning with both candy cane and Allen stirrups is critical during vaginal surgery.

Tip #5: Ensure that the lateral fibula is not touching the stirrup or that padding is placed between the fibular head and the stirrup.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are typically injured via suture entrapment from low transverse skin incisions, though laparoscopic injury has also been reported. The incidence after a Pfannenstiel incision is about 3.7%.7

Tip #6: Avoid extending the low transverse incision beyond the lateral margin of the rectus muscle, and do not extend the fascial closure suture more than 1.5 cm from the lateral edge of the fascial incision to avoid catching the nerve with the suture.

The pudendal nerve is most commonly injured during vaginal procedures such as sacrospinous fixation. Pain is typically worse when seated.

The genitofemoral nerve is typically injured during retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, particularly the external iliac nodes. The nerve is small and runs lateral to the external iliac artery. It can suffer cautery and transection injuries. Usually, the paresthesias over the mons pubis, labia majora, and medial inner thigh are temporary.

Tip #7: Care should be taken to identify and spare the nerve during retroperitoneal dissection or external iliac node removal.

Nerve injuries during gynecologic surgery are common and are a significant cause of potential morbidity. While occasionally unavoidable and inherent to the surgical procedure, many times the injury could be prevented with proper attention and care to patient positioning and retractor use. Gynecologists should be aware of the risks and have a through understanding of the anatomy. However, should an injury occur, the patient can be reassured that most are self-limited and full recovery is generally expected. In a prospective study, the median time to resolution of symptoms was 31.5 days (range, 1 day to 6 months).5

References

1. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2014;16:29-36.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 1988 Nov;31(3):462-6.

3. Fertil Steril. 1993 Oct;60(4):729-32.

4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):664-72.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;201(5):531.e1-7.

6. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985 Dec;20(6):385-92.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):839-46.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email her at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Upper- and lower-extremity injuries can occur during gynecologic surgery. The incidence of lower-extremity injury is 1.1%-1.9% and upper-extremity injuries can occur in 0.16% of cases.1-5 Fortunately, most of the injuries are transient, sensory injuries that resolve spontaneously. However, a small percentage of injuries result in long-term sequelae.

The pathophysiology of the nerve injuries can be mechanistically separated into three categories: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia results from nerve demyelination at the site of injury because of compression and typically resolves within weeks to months as the nerve is remyelinated. Axonotmesis results from severe compression with axon damage. This may take up to a year to resolve as axonal regeneration proceeds at the rate of 1 mm per day. This can be separated into second and third degree and refers to the severity of damage and the resultant persistent deficit. Neurotmesis results from complete transection and is associated with a poor prognosis without reparative surgery.

Brachial plexus

Stretch injury is the most common reason for a brachial plexus injury. This can occur if the arm board is extended to greater than 90 degrees from the patient’s torso or if the patient’s arm falls off of the arm board. Careful positioning and securing the patient’s arm on the arm board before draping can avoid this injury. A brachial plexus injury can also occur if shoulder braces are placed too laterally during minimally invasive surgery. Radial nerve injuries can occur if there is too much pressure on the humerus during positioning. Ulnar injuries arise from pressure placed on the medial aspect of the elbow.

Tip #1: When tucking a patient’s arm for minimally invasive surgery, appropriate padding should be placed around the elbow and wrist, and the arm should be in the “thumbs-up” position.

Tip #2: Shoulder blocks should be placed over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Lumbosacral plexus

The femoral nerve is the nerve most commonly injured during gynecologic surgery and this usually occurs because of compression of the nerve from the lateral blades of self-retaining retractors. One study showed an 8% incidence of injury from self-retaining retractors, compared with less than 1% when the retractors were not used.6 The femoral nerve can also be stretched when patients are placed in the lithotomy position and the hip is hyperflexed.

As with brachial injury prevention, patients should be positioned prior to draping and care must be taken to not hyperflex or externally rotate the hip during minimally invasive surgical procedures. With the introduction of robot-assisted surgery, care must be taken when docking the robot and surgeons must resist excessive movement of the stirrups.

Tip #3: During laparotomy, surgeons should use the shortest blades that allow for adequate visualization and check the blades during the procedure to ensure that excessive pressure is not placed on the psoas muscle. Consider intermittently releasing the pressure on the lateral blades during other portions of the procedure.

Tip #4: Make sure the stirrups are at the same height and that the leg is in line with the patient’s contralateral shoulder.

Obturator nerve injuries can occur during retroperitoneal dissection for pelvic lymphadenectomy (obturator nodes) and can be either a transection or a cautery injury. It can also be injured during urogynecologic procedures including paravaginal defect repairs and during the placement of transobturator tapes.

The sciatic nerve and its branch, the common peroneal, are generally injured because of excessive stretch or pressure. Both nerves can be injured from hyperflexion of the thigh and the common peroneal can suffer a pressure injury as it courses around the lateral head of the fibula. Therefore, care during lithotomy positioning with both candy cane and Allen stirrups is critical during vaginal surgery.

Tip #5: Ensure that the lateral fibula is not touching the stirrup or that padding is placed between the fibular head and the stirrup.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are typically injured via suture entrapment from low transverse skin incisions, though laparoscopic injury has also been reported. The incidence after a Pfannenstiel incision is about 3.7%.7

Tip #6: Avoid extending the low transverse incision beyond the lateral margin of the rectus muscle, and do not extend the fascial closure suture more than 1.5 cm from the lateral edge of the fascial incision to avoid catching the nerve with the suture.

The pudendal nerve is most commonly injured during vaginal procedures such as sacrospinous fixation. Pain is typically worse when seated.

The genitofemoral nerve is typically injured during retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, particularly the external iliac nodes. The nerve is small and runs lateral to the external iliac artery. It can suffer cautery and transection injuries. Usually, the paresthesias over the mons pubis, labia majora, and medial inner thigh are temporary.

Tip #7: Care should be taken to identify and spare the nerve during retroperitoneal dissection or external iliac node removal.

Nerve injuries during gynecologic surgery are common and are a significant cause of potential morbidity. While occasionally unavoidable and inherent to the surgical procedure, many times the injury could be prevented with proper attention and care to patient positioning and retractor use. Gynecologists should be aware of the risks and have a through understanding of the anatomy. However, should an injury occur, the patient can be reassured that most are self-limited and full recovery is generally expected. In a prospective study, the median time to resolution of symptoms was 31.5 days (range, 1 day to 6 months).5

References

1. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2014;16:29-36.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 1988 Nov;31(3):462-6.

3. Fertil Steril. 1993 Oct;60(4):729-32.

4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):664-72.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;201(5):531.e1-7.

6. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985 Dec;20(6):385-92.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):839-46.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email her at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Enhanced recovery pathways in gynecology

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Sentinel lymph node technique in endometrial cancer, Part 2

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.

The viability of the SLN technique is predicated on the ability to achieve mapping of dye or tracer from the tumor to the first lymph node to drain the tumor. The lymphatic drainage of the endometrium is complex and unlike vulvar or breast cancer, endometrial cancer is less accessible for peritumoral injection. Several injection techniques have been described; cervical injection is the easiest to achieve and has been found to have similar or higher SLN detection than hysteroscopic or fundal injections.4,5

There are a number of techniques for SLN detection, each with unique benefits and risks. Visual identification of blue dye, most frequently isosulfan blue, is the “colorimetric method” and has been used most commonly with cervical injection for endometrial cancer. Injection of isosulfan blue does not require specialized equipment, however visualization in obese patients is inferior.6

Technetium sulfur colloid (Tc) is a radioactive tracer that can be detected by gamma probes. A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and a handheld gamma probe are used to map lymphatics. This technique has limitations, including the additional time and coordination of procedures, as well as some evidence of poor correlation between lymphoscintigraphy and surgical SLN mapping.7

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye that has excellent signal penetration and allows for real-time visual identification using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. The bilateral detection rate with ICG appears comparable or better than blue dye.8 Combinations of dye, either ICG plus Tc or Tc plus blue dye, may be also used to increase SLN detection.

The accuracy of the SLN technique is the cornerstone to its success. In a prospective multicenter study – Senti-Endo – patients with early-stage disease underwent pelvic SLN assessment with cervical injection of a combination of dyes followed by systematic pelvic node dissection. The overall negative predictive value was 97% with three patients who had positive lymph nodes that were not detected, all of whom had a type 2 endometrial cancer.9

With the uptake of the SLN technique, many institutions have protocols surrounding the technique to ensure appropriate SLN detection and evaluation. Physicians using this technique should adhere to protocols supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, taking care to remove any suspicious lymph nodes and perform a full side-specific lymphadenectomy if bilateral mapping is not achieved.

The extent of lymphadenectomy and application of the SLN technique in high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. These patients are at higher risk for unsuccessful mapping and isolated para-aortic metastasis. Retrospective series have suggested equivalent oncologic outcomes for women with high-grade cancers who have been staged by SLN biopsy, compared with selective or complete lymphadenectomy.10,11

We await the results of a large prospective trial in which patients undergo comprehensive lymphadenectomy in addition to SLN biopsy to assess the accuracy of the technique (NCT01673022).

Pathologic evaluation of SLNs is frequently done with ultrastaging, which describes additional sectioning and staining of the node. This technique frequently identifies isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis (collectively called low-volume disease) in addition to macrometastasis. The clinical and prognostic significance of low-volume disease is unknown and additional investigation is urgently needed to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and follow-up for these patients.

The SLN technique is an acceptable approach to assess clinical stage I endometrial cancer. Physicians should consider adding the SLN biopsy to their routine staging techniques prior to exclusively adopting the new technique. They should take care to adhere to SLN algorithms and monitor outcomes.

References

1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707-16.

2. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373(9658):125-36.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;205(6):562.e1–9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Nov;131(2):299-303.

5. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Nov;23(9):1704-11.

6. Gynecol Oncol 2014 Aug;134(2):281-6.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Feb;112(2):348-352.

8. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):274-7.

9. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76.

10. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jan;23(1):196-202.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Mar;140(3):394-9.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Sullivan is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.