User login

The emotionally exhausted physician

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

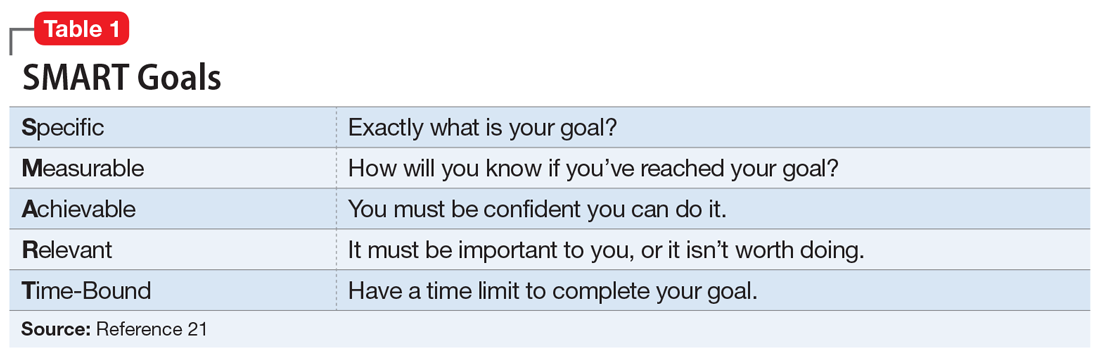

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

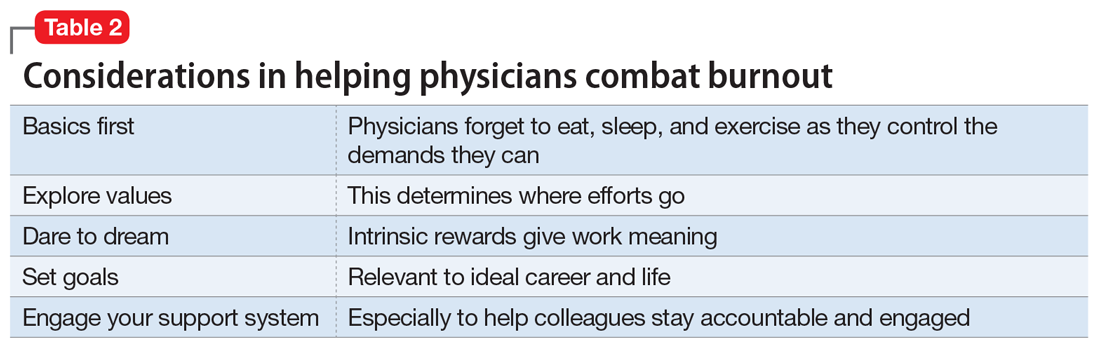

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

Bugs on her skin—but nobody else sees them

CASE Scratching, anxious, and hopeless

Ms. L, age 74, who is paraplegic and uses a wheelchair, presents to our hospital’s emergency department (ED) accompanied by staff from the nursing home where she resides. She reports that she can feel and see bugs crawling all over her skin, biting

Ms. L experiences generalized pruritus with excoriations scattered over her upper and lower extremities and her trunk. She copes with the pruritus by scratching. She reports that the bugs are present throughout the day and are worse at night when she tries to go to bed. Nothing she does provides relief from the infestation. Earlier, at the nursing home, Ms. L had obtained a detergent powder and used it in an attempt to purge the bugs. She now has large swaths of irritated skin, mostly on her lower back and perineal region.

She says the bug infestation became unbearable 3 weeks ago, but she can’t identify any precipitants for her symptoms. Ms. L reports that the impact of the bugs on her daily activity, sleep, and quality of life is enormous. Despite her complaints, neither the nursing home staff nor the ED staff can find any evidence of bugs on Ms. L’s clothes or skin.

Because Ms. L resorted to such drastic measures in her attempt to rid her body of the bugs, she is considered a safety risk and is admitted to the psychiatric unit, although she vehemently denies any intention to harm herself.

On the psychiatric unit, Ms. L states that the infestation began approximately 2 years ago. She began to experience severe worsening of her symptoms a few weeks before presenting to the ED.

During evaluation, Ms. L is alert and oriented to person, place, and situation. She is also quite cooperative but guarded in describing her infestation. There is some degree of suspiciousness and paranoia with regards to her infestation; she is very sensitive to how the clinical staff respond to her condition. She appears worried, and exhibits anxiety, sadness, hopelessness, and tearfulness. Her thought process is goal-directed, but preoccupied by the bugs.

[polldaddy:10064801]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

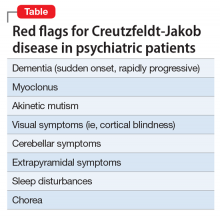

Delusional parasitosis is a rare disorder that is defined by an individual having a fixed, false belief that he or she is being infected or grossly invaded by a living organism. Karl A. Ekbom, a Swedish neurologist, was the first practitioner to definitively describe this affliction in 1938.1

Primary delusional parasitosis is a disease defined by this single psychotic symptom without other classic symptoms of schizophrenia; this single symptom cannot be attributed to the effects of substance abuse or a medical condition. Many affected patients remain functional in their daily lives; only a minority of patients experience delusions that interfere with usual activity.2 Secondary delusional parasitosis is a symptom of another psychiatric or medical disease.

Morgellons disease is characterized by symptoms similar to primary delusional parasitosis, but symptoms of this condition also include the delusional belief that inanimate objects, usually fibers, are in the skin as well as the parasites.3

A population-based study among individuals living in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1976 to 2010 found that the incidence of delusional infestation was 1.9 cases (95% confidence interval, 1.5 to 2.4) per 100,000 person-years.4 In a retrospective study of 147 patients with delusional parasitosis, 33% of these patients described themselves as disabled, 28% were retired, and 26% were employed.5 In this study, the mean age of diagnosis was 57, with a female-to-male ratio of 2.89:1.5

Continue to: HISTORY Prior psychiatric hospitalization

HISTORY Prior psychiatric hospitalization

Ms. L, who is divorced and retired, lives in a nursing home and has no pets, no exposure to scabies, no recent travel, no allergies, and no difficulty with her hygiene except at the peak of her illness. She denies any alcohol or illicit drug use but reports a 6 pack year history of smoking. She has a son, 2 grandchildren, and 2 great grandchildren who all live in town and see her regularly. She reports no history of arrests or legal problems.

Ms. L has a history of depression and anxiety that culminated in a “nervous breakdown” in 1985 with a brief stay in a psychiatric hospital. She reports that she had seen a therapist for 6 years as part of her treatment following that event. During her hospitalization, she was treated with a tricyclic antidepressant and received electroconvulsive therapy. She denies being suicidal during the incident in 1985 or at any point in time before or since then. She now takes venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, for depression and anxiety.

Ms. L’s paraplegia resulted from her sixth corrective surgery for scoliosis, which occurred 6 years ago. She has had chronic pain since this surgery. Her medical history also includes hypertension, atrial fibrillation, mild neurocognitive changes, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

EVALUATION Skin examination, blood analysis normal

On admission, Ms. L undergoes a skin examination, which yields no evidence consistent with infestation with Pediculus humanus corporis (body louse) or Sarcoptes scabiei (scabies).6 Blood analysis shows no iron deficiency, renal failure, hyperbilirubinemia, or eosinophilia. In the ED, the medical team examines Ms. L and explores other medical and dermatological causes of her condition. Because dermatological causes had been ruled out before Ms. L was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit, no dermatology consult is requested.

Continue to: TREATMENT A first-generation antipsychotic

TREATMENT A first-generation antipsychotic

When Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric unit, she is started

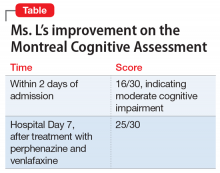

During the week, Ms. L’s perphenazine is titrated up to 24 mg twice daily and venlafaxine is titrated to 150 mg/d. A Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is performed within the first 2 days of admission and she scores 16/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment. On Friday, the attending physician explains that her medications should start to have therapeutic effect. During this time, this clinician engages in cognitive restructuring by providing validation of Ms. L’s suffering, verbal support, and medication compliance counseling. At this time, the treating team also suggests to Ms. L that she should expect the activity and effects of the bugs to dissipate. She is receptive to this suggestion. She also participates in the milieu, including unit activities, but is limited in her ability to engage in group therapy due to the intensity of her illness.

Throughout the weekend, the on-call physician also engages Ms. L and reports minor improvement.

OUTCOME Significant relief

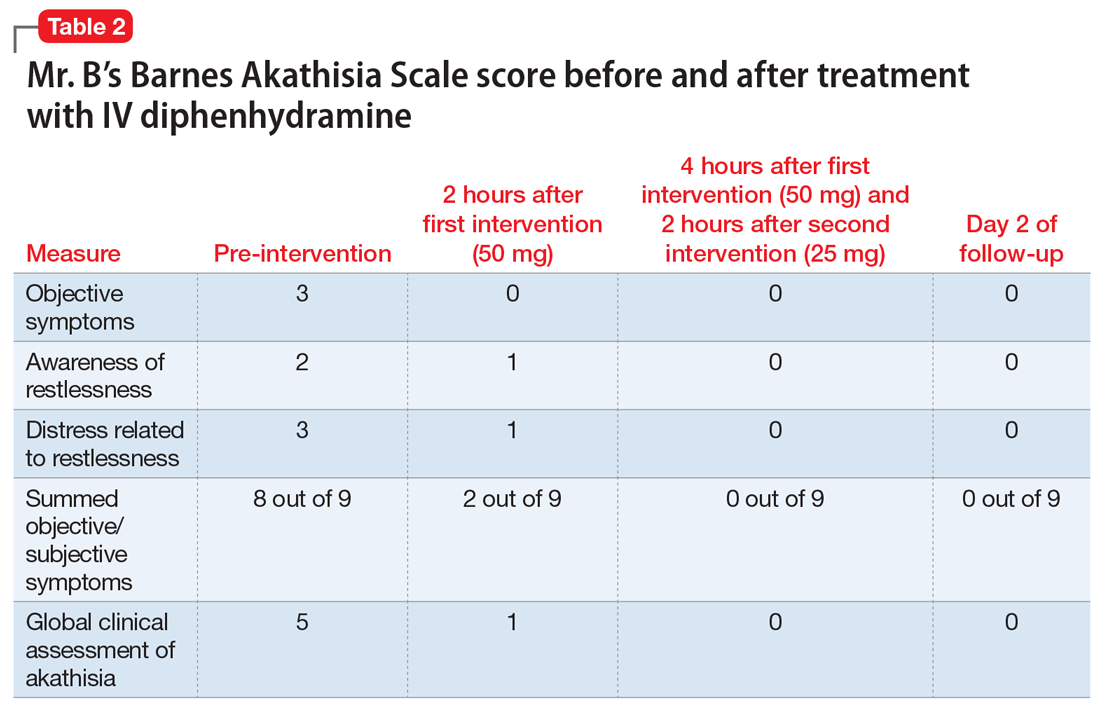

On re-evaluation Monday morning—almost a week after Ms. L had been admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit—she has achieved significant relief from her delusions. She says that she has no idea where the bugs have gone. Ms. L appears to be a completely different person. She no longer appears guarded. The suspiciousness, paranoia, hopelessness, and negative outlook she previously experienced have significantly diminished. Her MoCA score improves to 25/30, indicating no cognitive impairment (Table). She is discharged after a 7-night stay on the inpatient psychiatric unit.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

During one of the clinical multidisciplinary treatment team meetings held for Ms. L, it was initially estimated that it would take at least 2 weeks for the delusional parasitosis to significantly respond to antipsychotic therapy. However, it is our professional opinion that the applied cognitive restructuring, with validation of her suffering, verbal support, and medication adherence counseling, expedited her recovery. This coincided with the aggressive titration of her antipsychotic and antidepressant, although the treatment team’s acknowledgment of Ms. L’s misery appeared to lower her guard and make her more susceptible to the power of cognitive restructuring. The efforts to validate the patient’s feelings and decrease hopelessness by telling her that the medication would make the bugs go away appeared to be the tipping point for her recovery. Patients with primary delusional parasitosis often are guarded and may feel alone in their predicament when they are met with perplexed responses from individuals with whom they discuss their symptoms. Compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with delusional parasitosis maintain normal cognitive functioning, which may give them the insight to understand how their experience may be perceived as incompatible with reality.7 This understanding, coupled with some perceived helplessness, can lead a patient to fear having a severe mental decompensation, which can contribute to a delayed or complicated recovery.

The cognitive process described above might have been responsible for the difference in Ms. L’s MoCA scores because her performance in the initial test was hindered by her constant obsession with the bugs, which made her distracted during the test. By the time she responded to treatment, she gained significant clarity of thought, which enabled her to perform optimally in the test.

The difficulty in treating patients with delusional parasitosis may be further affected by lack of insight, and the fact that they often do not present to a psychiatrist for treatment in a timely manner because their delusion is impregnable and presents them with an alternate reality. These patients are more likely to seek out primary care physicians, dermatologists, infectious disease doctors, and entomologists because of the fervor of their delusion and the intensity of their discomfort. Because of this, a collaboration between these providers would likely lead to improved care and treatment acceptance for patients with delusional parasitosis.

Antipsychotics are the preferred medication for treating delusional parasitosis, and the literature supports their use for this purpose.6,8 The overall response rate is 60% to 100%.6 Previously, in small placebo-controlled trials, the first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) pimozide was considered first-line treatment for this disease.6 However, this antipsychotic is no longer favored because evidence is mounting that other FGAs result in comparable response rates with fewer tolerability issues.8,9

The bulk of data on the use of antipsychotics for treating delusional parasitosis comes from retrospective case reports and case series.6 Multiple antipsychotics have been shown to be effective in treating delusional parasitosis, including both FGAs and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).6,10 Published case reports and series have shown the effectiveness of the FGAs

Continue to: The SGAs risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole...

The SGAs

When selecting antipsychotic therapy for a patient diagnosed with delusional parasitosis, consider patient-specific factors, such as age, medication history, comorbidities, and the adverse-effect profile of the medication(s). These medications should be started at a low dose and titrated based on efficacy and safety. The optimal duration of therapy varies by patient. Patients should continually be assessed for possible treatment discontinuation, although if therapy is tapered off, patients need to be closely monitored for possible relapse or recurrence of symptoms.

Ms. L received perphenazine titrated up to 24 mg/d for the treatment of delusional parasitosis. The maximum dose used for Ms. L was higher than those used in previous reports, although she appeared to tolerate the medication well and respond rapidly. Her symptoms showed improvement within 1 week. Importantly, in published case reports, patients have been resistant to the use of psychotropic medications without other treatment modalities (eg, psychotherapy, various behavioral approaches). We conclude that Ms. L’s response was attributable to the use of the combination of psychotherapeutic techniques and the effectiveness of perphenazine and venlafaxine.

Bottom Line

Managing patients with primary delusional parasitosis can be challenging due to the fixed nature of the delusion. A combination of antipsychotics and psychotherapeutic techniques can benefit some patients. The optimal duration of treatment varies by patient.

Related Resource

- Trenton A, Pansare N, Tobia A, et al. Delusional parasitosis on the psychiatric consultation service-a longitudinal perspective: case study. BJPsych Open. 2017;3(3):154-158.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Perphenazine • Trilafon

Pimozide • Orap

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Ekbom KA. Der präsenile dermatozoenwahn [in Swedish]. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1938;13(3):227-259.

2. Lynch PJ. Delusions of parasitosis. Semin Dermatol. 1993;12(1):39-45.

3. Middelveen MJ, Fesler MC, Stricker RB. History of Morgellons disease: from delusion to definition. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:71-90.

4. Bailey CH, Andersen LK, Lowe GC, et al. A population-based study of the incidence of delusional infestation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–2010. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(5):1130-1135.

5. Foster AA, Hylwa SA, Bury JE, et al. Delusional infestation: clinical presentation in 147 patients seen at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):673.e1-e10.

6. Lepping P, Russell I, Freudenmann RW. Antipsychotic treatment of primary delusional parasitosis: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(3):198-205.

7. Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Delusional infestation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(4):690-732.

8. Mercan S, Altunay IK, Taskintuna N, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of delusional parasitosis. Intl J Psychiatry Med. 2007:37(1):29-37.

9. Trabert W. 100 years of delusional parasitosis. Meta-analysis of 1,223 case reports. Psychopathology. 1995;28(5):238-246.

10. Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(5):500-508.

11. Boggild AK, Nicks BA, Yen L, et al. Delusional parasitosis: six-year experience with 23 consecutive cases at an academic medical center. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(4):e317-e321.

CASE Scratching, anxious, and hopeless

Ms. L, age 74, who is paraplegic and uses a wheelchair, presents to our hospital’s emergency department (ED) accompanied by staff from the nursing home where she resides. She reports that she can feel and see bugs crawling all over her skin, biting

Ms. L experiences generalized pruritus with excoriations scattered over her upper and lower extremities and her trunk. She copes with the pruritus by scratching. She reports that the bugs are present throughout the day and are worse at night when she tries to go to bed. Nothing she does provides relief from the infestation. Earlier, at the nursing home, Ms. L had obtained a detergent powder and used it in an attempt to purge the bugs. She now has large swaths of irritated skin, mostly on her lower back and perineal region.

She says the bug infestation became unbearable 3 weeks ago, but she can’t identify any precipitants for her symptoms. Ms. L reports that the impact of the bugs on her daily activity, sleep, and quality of life is enormous. Despite her complaints, neither the nursing home staff nor the ED staff can find any evidence of bugs on Ms. L’s clothes or skin.

Because Ms. L resorted to such drastic measures in her attempt to rid her body of the bugs, she is considered a safety risk and is admitted to the psychiatric unit, although she vehemently denies any intention to harm herself.

On the psychiatric unit, Ms. L states that the infestation began approximately 2 years ago. She began to experience severe worsening of her symptoms a few weeks before presenting to the ED.

During evaluation, Ms. L is alert and oriented to person, place, and situation. She is also quite cooperative but guarded in describing her infestation. There is some degree of suspiciousness and paranoia with regards to her infestation; she is very sensitive to how the clinical staff respond to her condition. She appears worried, and exhibits anxiety, sadness, hopelessness, and tearfulness. Her thought process is goal-directed, but preoccupied by the bugs.

[polldaddy:10064801]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Delusional parasitosis is a rare disorder that is defined by an individual having a fixed, false belief that he or she is being infected or grossly invaded by a living organism. Karl A. Ekbom, a Swedish neurologist, was the first practitioner to definitively describe this affliction in 1938.1

Primary delusional parasitosis is a disease defined by this single psychotic symptom without other classic symptoms of schizophrenia; this single symptom cannot be attributed to the effects of substance abuse or a medical condition. Many affected patients remain functional in their daily lives; only a minority of patients experience delusions that interfere with usual activity.2 Secondary delusional parasitosis is a symptom of another psychiatric or medical disease.

Morgellons disease is characterized by symptoms similar to primary delusional parasitosis, but symptoms of this condition also include the delusional belief that inanimate objects, usually fibers, are in the skin as well as the parasites.3

A population-based study among individuals living in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1976 to 2010 found that the incidence of delusional infestation was 1.9 cases (95% confidence interval, 1.5 to 2.4) per 100,000 person-years.4 In a retrospective study of 147 patients with delusional parasitosis, 33% of these patients described themselves as disabled, 28% were retired, and 26% were employed.5 In this study, the mean age of diagnosis was 57, with a female-to-male ratio of 2.89:1.5

Continue to: HISTORY Prior psychiatric hospitalization

HISTORY Prior psychiatric hospitalization

Ms. L, who is divorced and retired, lives in a nursing home and has no pets, no exposure to scabies, no recent travel, no allergies, and no difficulty with her hygiene except at the peak of her illness. She denies any alcohol or illicit drug use but reports a 6 pack year history of smoking. She has a son, 2 grandchildren, and 2 great grandchildren who all live in town and see her regularly. She reports no history of arrests or legal problems.

Ms. L has a history of depression and anxiety that culminated in a “nervous breakdown” in 1985 with a brief stay in a psychiatric hospital. She reports that she had seen a therapist for 6 years as part of her treatment following that event. During her hospitalization, she was treated with a tricyclic antidepressant and received electroconvulsive therapy. She denies being suicidal during the incident in 1985 or at any point in time before or since then. She now takes venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, for depression and anxiety.

Ms. L’s paraplegia resulted from her sixth corrective surgery for scoliosis, which occurred 6 years ago. She has had chronic pain since this surgery. Her medical history also includes hypertension, atrial fibrillation, mild neurocognitive changes, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

EVALUATION Skin examination, blood analysis normal

On admission, Ms. L undergoes a skin examination, which yields no evidence consistent with infestation with Pediculus humanus corporis (body louse) or Sarcoptes scabiei (scabies).6 Blood analysis shows no iron deficiency, renal failure, hyperbilirubinemia, or eosinophilia. In the ED, the medical team examines Ms. L and explores other medical and dermatological causes of her condition. Because dermatological causes had been ruled out before Ms. L was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit, no dermatology consult is requested.

Continue to: TREATMENT A first-generation antipsychotic

TREATMENT A first-generation antipsychotic

When Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric unit, she is started

During the week, Ms. L’s perphenazine is titrated up to 24 mg twice daily and venlafaxine is titrated to 150 mg/d. A Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is performed within the first 2 days of admission and she scores 16/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment. On Friday, the attending physician explains that her medications should start to have therapeutic effect. During this time, this clinician engages in cognitive restructuring by providing validation of Ms. L’s suffering, verbal support, and medication compliance counseling. At this time, the treating team also suggests to Ms. L that she should expect the activity and effects of the bugs to dissipate. She is receptive to this suggestion. She also participates in the milieu, including unit activities, but is limited in her ability to engage in group therapy due to the intensity of her illness.

Throughout the weekend, the on-call physician also engages Ms. L and reports minor improvement.

OUTCOME Significant relief

On re-evaluation Monday morning—almost a week after Ms. L had been admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit—she has achieved significant relief from her delusions. She says that she has no idea where the bugs have gone. Ms. L appears to be a completely different person. She no longer appears guarded. The suspiciousness, paranoia, hopelessness, and negative outlook she previously experienced have significantly diminished. Her MoCA score improves to 25/30, indicating no cognitive impairment (Table). She is discharged after a 7-night stay on the inpatient psychiatric unit.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

During one of the clinical multidisciplinary treatment team meetings held for Ms. L, it was initially estimated that it would take at least 2 weeks for the delusional parasitosis to significantly respond to antipsychotic therapy. However, it is our professional opinion that the applied cognitive restructuring, with validation of her suffering, verbal support, and medication adherence counseling, expedited her recovery. This coincided with the aggressive titration of her antipsychotic and antidepressant, although the treatment team’s acknowledgment of Ms. L’s misery appeared to lower her guard and make her more susceptible to the power of cognitive restructuring. The efforts to validate the patient’s feelings and decrease hopelessness by telling her that the medication would make the bugs go away appeared to be the tipping point for her recovery. Patients with primary delusional parasitosis often are guarded and may feel alone in their predicament when they are met with perplexed responses from individuals with whom they discuss their symptoms. Compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with delusional parasitosis maintain normal cognitive functioning, which may give them the insight to understand how their experience may be perceived as incompatible with reality.7 This understanding, coupled with some perceived helplessness, can lead a patient to fear having a severe mental decompensation, which can contribute to a delayed or complicated recovery.

The cognitive process described above might have been responsible for the difference in Ms. L’s MoCA scores because her performance in the initial test was hindered by her constant obsession with the bugs, which made her distracted during the test. By the time she responded to treatment, she gained significant clarity of thought, which enabled her to perform optimally in the test.

The difficulty in treating patients with delusional parasitosis may be further affected by lack of insight, and the fact that they often do not present to a psychiatrist for treatment in a timely manner because their delusion is impregnable and presents them with an alternate reality. These patients are more likely to seek out primary care physicians, dermatologists, infectious disease doctors, and entomologists because of the fervor of their delusion and the intensity of their discomfort. Because of this, a collaboration between these providers would likely lead to improved care and treatment acceptance for patients with delusional parasitosis.

Antipsychotics are the preferred medication for treating delusional parasitosis, and the literature supports their use for this purpose.6,8 The overall response rate is 60% to 100%.6 Previously, in small placebo-controlled trials, the first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) pimozide was considered first-line treatment for this disease.6 However, this antipsychotic is no longer favored because evidence is mounting that other FGAs result in comparable response rates with fewer tolerability issues.8,9

The bulk of data on the use of antipsychotics for treating delusional parasitosis comes from retrospective case reports and case series.6 Multiple antipsychotics have been shown to be effective in treating delusional parasitosis, including both FGAs and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).6,10 Published case reports and series have shown the effectiveness of the FGAs

Continue to: The SGAs risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole...

The SGAs

When selecting antipsychotic therapy for a patient diagnosed with delusional parasitosis, consider patient-specific factors, such as age, medication history, comorbidities, and the adverse-effect profile of the medication(s). These medications should be started at a low dose and titrated based on efficacy and safety. The optimal duration of therapy varies by patient. Patients should continually be assessed for possible treatment discontinuation, although if therapy is tapered off, patients need to be closely monitored for possible relapse or recurrence of symptoms.

Ms. L received perphenazine titrated up to 24 mg/d for the treatment of delusional parasitosis. The maximum dose used for Ms. L was higher than those used in previous reports, although she appeared to tolerate the medication well and respond rapidly. Her symptoms showed improvement within 1 week. Importantly, in published case reports, patients have been resistant to the use of psychotropic medications without other treatment modalities (eg, psychotherapy, various behavioral approaches). We conclude that Ms. L’s response was attributable to the use of the combination of psychotherapeutic techniques and the effectiveness of perphenazine and venlafaxine.

Bottom Line

Managing patients with primary delusional parasitosis can be challenging due to the fixed nature of the delusion. A combination of antipsychotics and psychotherapeutic techniques can benefit some patients. The optimal duration of treatment varies by patient.

Related Resource

- Trenton A, Pansare N, Tobia A, et al. Delusional parasitosis on the psychiatric consultation service-a longitudinal perspective: case study. BJPsych Open. 2017;3(3):154-158.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Perphenazine • Trilafon

Pimozide • Orap

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

CASE Scratching, anxious, and hopeless

Ms. L, age 74, who is paraplegic and uses a wheelchair, presents to our hospital’s emergency department (ED) accompanied by staff from the nursing home where she resides. She reports that she can feel and see bugs crawling all over her skin, biting