User login

A 10-year-old boy with ‘voices in my head’: Is it a psychotic disorder?

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

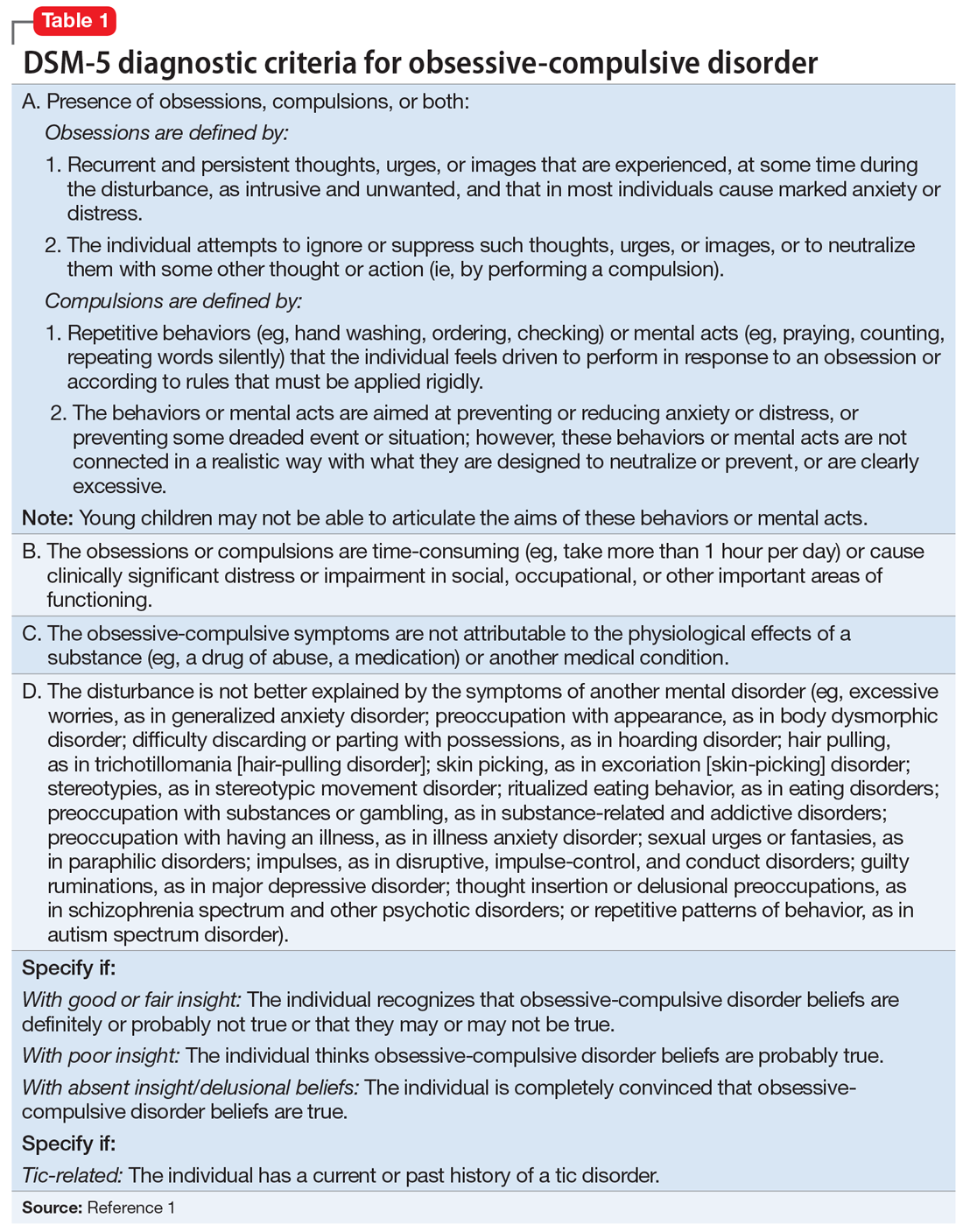

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

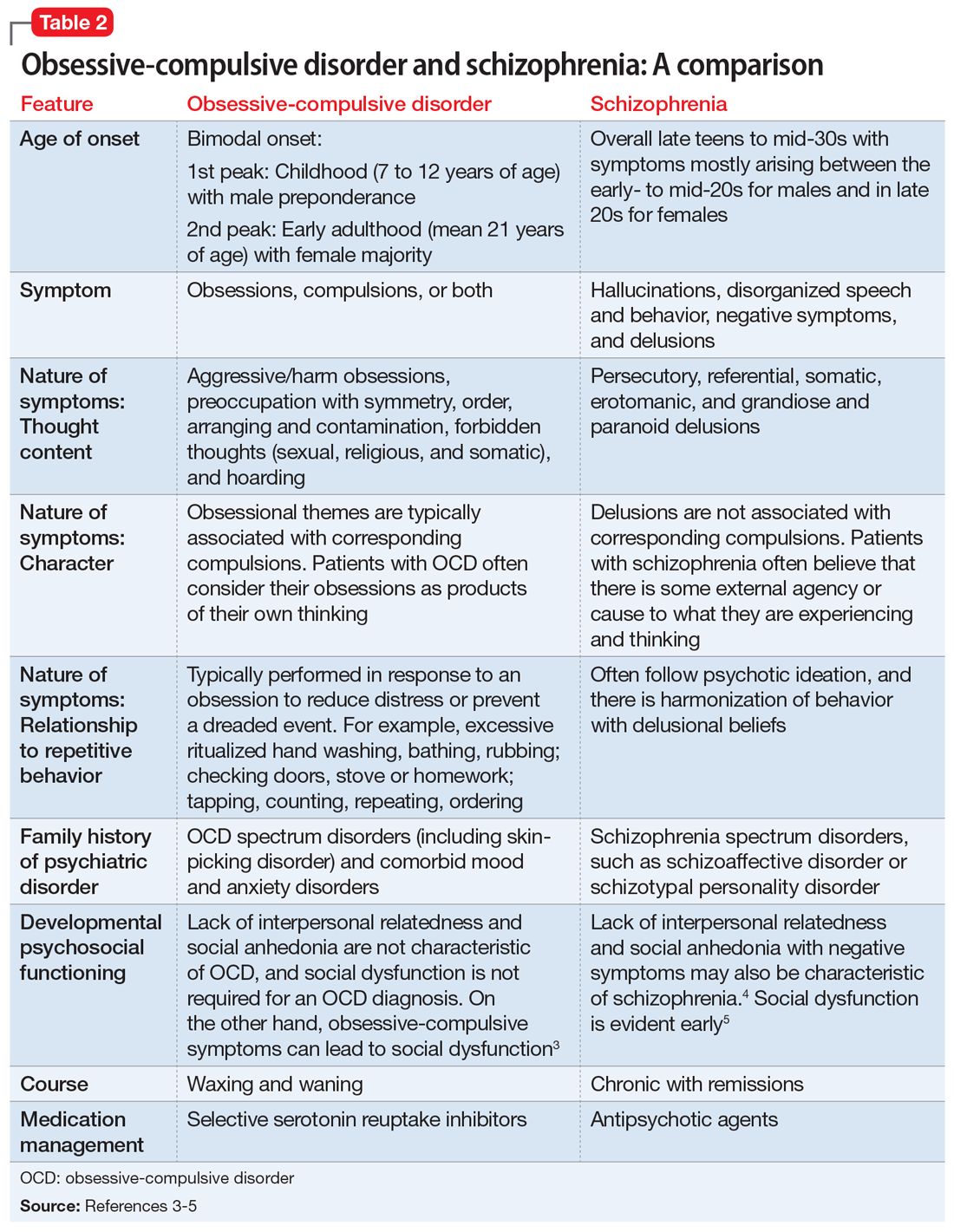

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

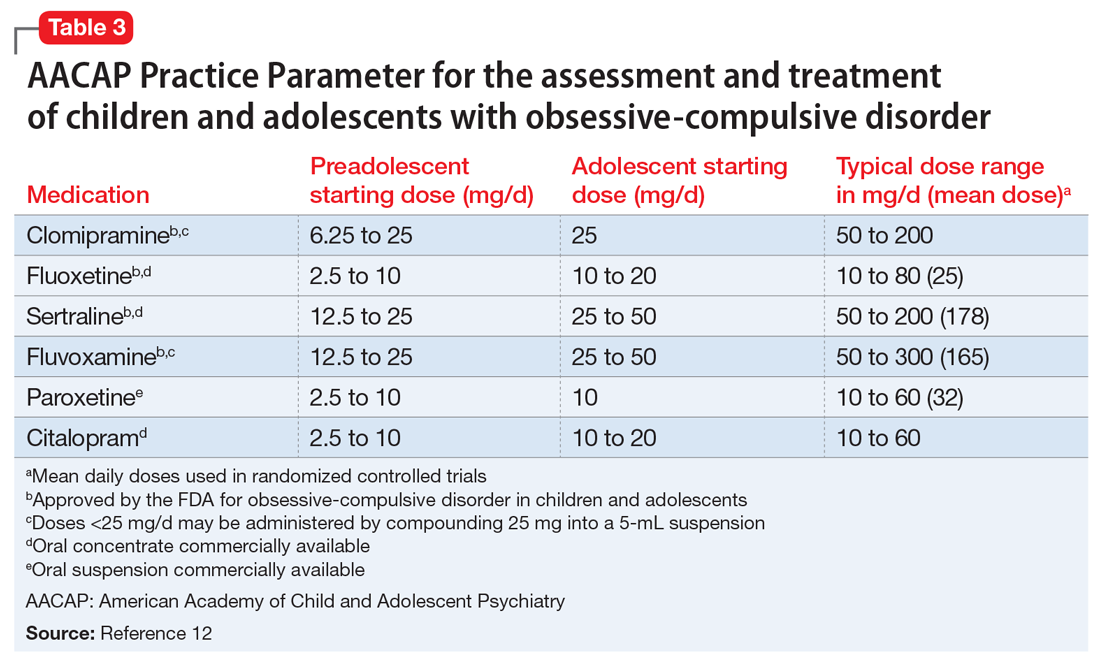

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant with serotonergic properties that is used alone or to boost the effect of an SSRI when there is a partial response. It should be introduced at a low dose in pediatric patients (before age 12) and closely monitored for anticholinergic and cardiac adverse effects. A systemic review and meta-analysis of early treatment responses of SSRIs and clomipramine in pediatric OCD indicated that the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment.18 Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared with placebo than SSRIs; there was no evidence of a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data were limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time course of response to SSRIs in OCD.18

Treatment should start with a low dose to reduce the risk of adverse effects with an adequate trial for 10 to 16 weeks at adequate doses. Most experts suggest that treatment should continue for at least 12 months after symptom resolution or stabilization, followed by a very gradual cessation.19

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

After 12 months of combined CBT and fluoxetine, M’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale score improves from 35 to 80, indicating major improvement in overall functional level.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Uzoma Osuchukwu, MD, ex-fellow, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York, for his assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may masquerade as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, particularly in younger patients. Accurate differentiation is crucial because antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.

Related Resource

- Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Sharma E, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder masquerading as psychosis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(2):179-180.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1998;37(4):420-427.

3. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45.

4. Sobel W, Wolski R, Cancro R, et al. Interpersonal relatedness and paranoid schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1996;153(8):1084-1087.

5. Meares A. The diagnosis of prepsychotic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1959;1(7063):55-58.

6. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: Clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989-1010.

7. Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):135.

8. Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):183.

9. Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29(2):352-370.

10. Evans DW, Milanak ME, Medeiros B, et al. Magical beliefs and rituals in young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(1):43-58.

11. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa E. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):209-217.

12. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

13. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

14. Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224-1232.

15. Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Vitiello B, et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):5-10.

16. Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92-97.

17. Findling RL. How (not) to dose antidepressants and antipsychotics for children. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(6):79-83.

18. Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: early treatment responses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):851-859.e2.

19. Mancuso E, Faro A, Joshi G, et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):299-308.

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant with serotonergic properties that is used alone or to boost the effect of an SSRI when there is a partial response. It should be introduced at a low dose in pediatric patients (before age 12) and closely monitored for anticholinergic and cardiac adverse effects. A systemic review and meta-analysis of early treatment responses of SSRIs and clomipramine in pediatric OCD indicated that the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment.18 Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared with placebo than SSRIs; there was no evidence of a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data were limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time course of response to SSRIs in OCD.18

Treatment should start with a low dose to reduce the risk of adverse effects with an adequate trial for 10 to 16 weeks at adequate doses. Most experts suggest that treatment should continue for at least 12 months after symptom resolution or stabilization, followed by a very gradual cessation.19

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

After 12 months of combined CBT and fluoxetine, M’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale score improves from 35 to 80, indicating major improvement in overall functional level.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Uzoma Osuchukwu, MD, ex-fellow, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York, for his assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may masquerade as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, particularly in younger patients. Accurate differentiation is crucial because antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.

Related Resource

- Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Sharma E, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder masquerading as psychosis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(2):179-180.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant with serotonergic properties that is used alone or to boost the effect of an SSRI when there is a partial response. It should be introduced at a low dose in pediatric patients (before age 12) and closely monitored for anticholinergic and cardiac adverse effects. A systemic review and meta-analysis of early treatment responses of SSRIs and clomipramine in pediatric OCD indicated that the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment.18 Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared with placebo than SSRIs; there was no evidence of a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data were limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time course of response to SSRIs in OCD.18

Treatment should start with a low dose to reduce the risk of adverse effects with an adequate trial for 10 to 16 weeks at adequate doses. Most experts suggest that treatment should continue for at least 12 months after symptom resolution or stabilization, followed by a very gradual cessation.19

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

After 12 months of combined CBT and fluoxetine, M’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale score improves from 35 to 80, indicating major improvement in overall functional level.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Uzoma Osuchukwu, MD, ex-fellow, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York, for his assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may masquerade as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, particularly in younger patients. Accurate differentiation is crucial because antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.

Related Resource

- Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Sharma E, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder masquerading as psychosis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(2):179-180.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1998;37(4):420-427.

3. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45.

4. Sobel W, Wolski R, Cancro R, et al. Interpersonal relatedness and paranoid schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1996;153(8):1084-1087.

5. Meares A. The diagnosis of prepsychotic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1959;1(7063):55-58.

6. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: Clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989-1010.

7. Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):135.

8. Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):183.

9. Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29(2):352-370.

10. Evans DW, Milanak ME, Medeiros B, et al. Magical beliefs and rituals in young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(1):43-58.

11. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa E. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):209-217.

12. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

13. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

14. Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224-1232.

15. Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Vitiello B, et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):5-10.

16. Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92-97.

17. Findling RL. How (not) to dose antidepressants and antipsychotics for children. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(6):79-83.

18. Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: early treatment responses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):851-859.e2.

19. Mancuso E, Faro A, Joshi G, et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):299-308.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1998;37(4):420-427.

3. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45.

4. Sobel W, Wolski R, Cancro R, et al. Interpersonal relatedness and paranoid schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1996;153(8):1084-1087.

5. Meares A. The diagnosis of prepsychotic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1959;1(7063):55-58.

6. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: Clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989-1010.

7. Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):135.

8. Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):183.

9. Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29(2):352-370.

10. Evans DW, Milanak ME, Medeiros B, et al. Magical beliefs and rituals in young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(1):43-58.

11. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa E. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):209-217.

12. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

13. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

14. Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224-1232.

15. Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Vitiello B, et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):5-10.

16. Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92-97.

17. Findling RL. How (not) to dose antidepressants and antipsychotics for children. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(6):79-83.

18. Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: early treatment responses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):851-859.e2.

19. Mancuso E, Faro A, Joshi G, et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):299-308.

Decompensation in a 51-year-old woman with schizophrenia

CASE Psychotic and reclusive

Ms. A, age 51, has schizophrenia and has been doing well living at a supervised residential facility. She was stable on haloperidol, 10 mg twice a day, for years but recently became agitated, threatening her roommate and yelling during the night. Ms. A begins to refuse to take her haloperidol. She also refuses to attend several outpatient appointments. As a result, Ms. A is admitted to the psychiatric unit on an involuntary basis.

In the hospital, Ms. A rarely comes out of her room. When she does come out, she usually sits in a chair, talking to herself and occasionally yelling or crying in apparent distress. Ms. A refuses to engage with her treatment team and lies mute in her bed when they attempt to interview her. Her records indicate that previous medication trials have included

Over the next week, Ms. A begins to interact more appropriately with nursing sta

[polldaddy:9945425]

The authors’ observations

As a class, antipsychotics lead to symptom reduction in approximately 70% of patients.1 However, the degree of response can vary markedly between individuals; although some patients may experience almost complete resolution of symptoms, others are still markedly impaired, as in Ms. A’s case.

A substantial amount of literature suggests that although the practice is common, use of >1 antipsychotic does not significantly increase efficacy but increases risk of adverse effects, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal symptoms.2-4 One exception is augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic, which in certain cases appears to offer greater efficacy than clozapine alone.1 Practice guidelines and evidence generally do not support the use of multiple antipsychotics, but 20% of patients take >1 antipsychotic.5,6 Although antipsychotic polypharmacy may be appropriate for some patients, current literature suggests it is being done more often than recommended.

Clozapine is considered the most efficacious option for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.7 Because of Ms. A’s history of recurrent hospitalizations, her extensive list of trialed medications, and her ongoing symptoms despite a sufficient trial of haloperidol, the treatment team gives serious consideration to switching Ms. A to clozapine. However, Ms. A is not able to tolerate blood draws without significant support from nursing staff, and it is likely she would be unable to tolerate the frequent blood monitoring required of patients receiving clozapine.

Because many of Ms. A’s symptoms were negative or depressive, including hypersomnia, psychomotor retardation, sadness with frequent crying spells, and reduced interest in activities, adding an antidepressant to Ms. A’s medication regimen was considered. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that adding an antidepressant to an antipsychotic in patients with schizophrenia had small but beneficial effects on depressive and negative symptoms and a low risk of adverse effects.8 However, Ms. A declined this option.

TREATMENT Adding long-acting haloperidol

Ms. A had previously achieved therapeutic blood levels9 with oral haloperidol. Data suggest that compared with the oral form, long-acting injectable antipsychotics can both improve compliance and decrease rehospitalization rates.10-12 Because Ms. A previously had done well with haloperidol decanoate, 200 mg every 2 weeks, achieving a blood level of 16.2 ng/mL, and because she had a partial response to oral haloperidol, we add haloperidol decanoate, 100 mg every 2 weeks, to her regimen, with the intention of transitioning her to all-depot dosing. In addition, the treatment team tries to engage Ms. A in a discussion of potential psychological contributions to her current presentation. They note that Ms. A has her basic needs met on the unit and reports feeling safe there; thus, a fear of discharge may be contributing to her lack of engagement with the team. However, because of her limited communication, it is challenging to investigate this hypothesis or explore other possible psychological issues.

Despite increasing the dosing of haloperidol, Ms. A shows minimal improvement. She continues to stonewall her treatment team, and is unwilling or unable to engage in meaningful conversation. A review of her chart suggests that this hospital course is different from previous ones in which her average stay was a few weeks, and she generally was able to converse with the treatment team, participate in discussions about her care, and make decisions about her desire for discharge.

The team considers if additional factors could be impacting Ms. A’s current presentation. They raise the possibility that she could be going through menopause, and hormonal fluctuations may be contributing to her symptoms. Despite being on the unit for nearly 2 months, Ms. A has not required the use of sanitary products. She also reports to nursing staff that at times she feels flushed and sweaty, but she is afebrile and does not have other signs or symptoms of infection.

[polldaddy:9945428]

The authors’ observations

Evidence suggests that estrogen levels can influence the development and severity of symptoms of schizophrenia (Table 113,14). Rates of schizophrenia are lower in women, and women typically have a later onset of illness with less severe symptoms.13 Women also have a second peak incidence of schizophrenia between ages 45 and 50, corresponding with the hormonal changes associated with menopause and the associated drop in estrogen.14 Symptoms also fluctuate with hormonal cycles—women experience worsening symptoms during the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen levels are low, and an improvement of symptoms during high-estrogen phases of the cycle.14 Overall, low levels of estrogen also have been observed in women with schizophrenia relative to controls, although this may be partially attributable to treatment with antipsychotics.14

Estrogen affects various regions of the brain implicated in schizophrenia and likely imparts its behavioral effects through several different mechanisms. Estrogen can act on cells to directly impact intracellular signaling and to alter gene expression.15 Although most often thought of as being related to reproductive functions, estrogen receptors can be found in many cortical and subcortical regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, substantia nigra, and prefrontal cortex. Estrogen receptor expression levels in certain brain regions have been found to be altered in individuals with schizophrenia.15 Estrogen also enhances neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, playing a role in learning and memory.16 Particularly relevant, estrogen has been shown to directly impact both the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems.15,17 In animal models, estrogen has been shown to decrease the behavioral effects induced by dopamine agonists and decrease symptoms of schizophrenia.18 The underlying molecular mechanisms by which estrogen has these effects are uncertain.

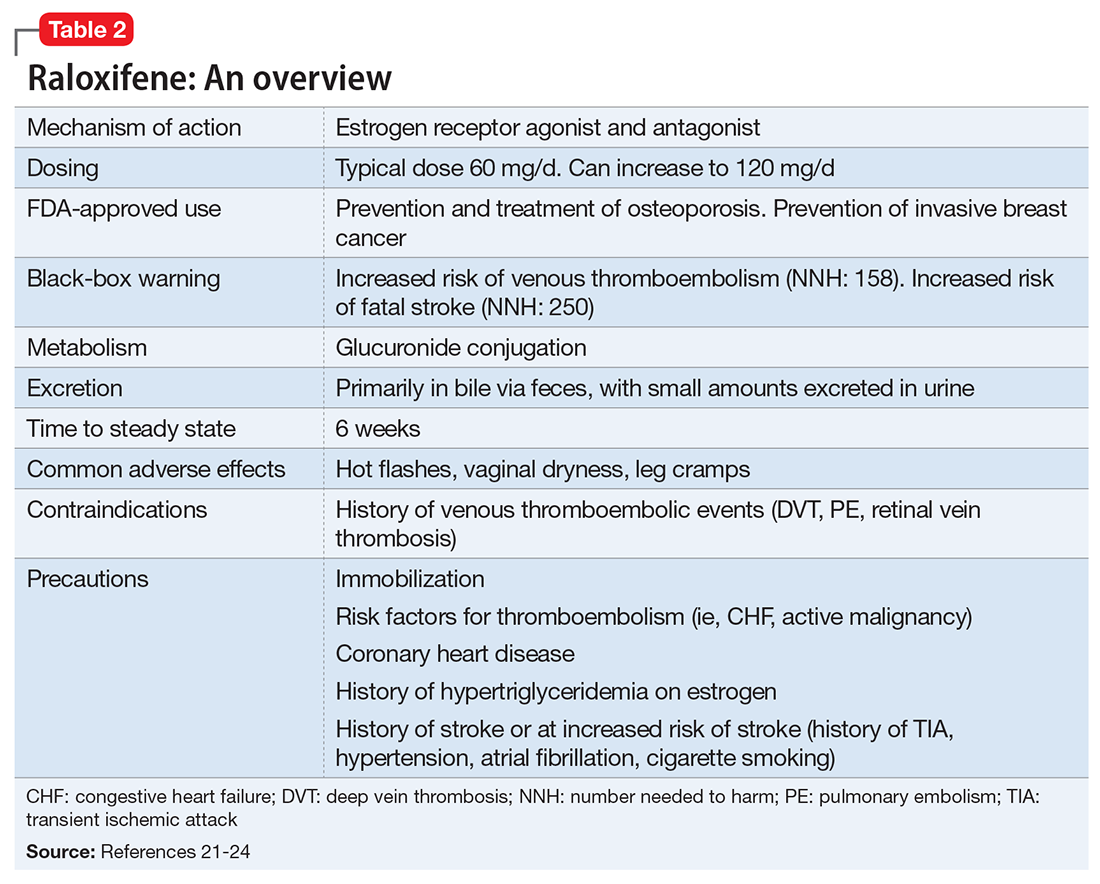

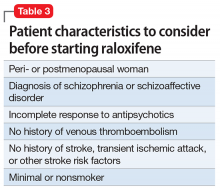

Given estrogen’s potentially protective effects, clinical trials have explored the role of estrogen as an adjuvant to antipsychotics for treating schizophrenia. Studies have shown that estrogen can improve psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.19,20 However, because estrogen administration can increase the risk of breast and uterine cancer, researchers are instead investigating selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs).14 These medications have mixed agonist and antagonist effects, with different effects on different tissues. Raloxifene is a SERM that acts as an estrogen agonist in some tissues, but an antagonist in uterine and breast tissue, which may minimize potential deleterious adverse effects (Table 221-24). Repeated randomized controlled trials have found promising results for use of raloxifene as an adjunctive treatment in peri- and postmenopausal women with schizophrenia, including those refractory to antipsychotic treatment.13,25-27

TREATMENT Address symptoms

The treatment team takes steps to address Ms. A’s perimenopausal symptoms. For mild to moderate hot flashes, primary interventions are nonpharmacologic.28 Because Ms. A primarily reports her hot flashes at night, she is given lightweight pajamas and moved to the coolest room on the unit. Both bring some relief, and her hot flashes appear to be less distressing. The treatment team decides to consult Endocrinology to further investigate the feasibility of starting raloxifene (Table 3) because of their experience using this medication to manage osteoporosis.

[polldaddy:9945429]

The authors’ observations

Raloxifene is FDA-approved for treating osteoporosis and preventing invasive breast cancer.29 Because it is an estrogen antagonist in both breast and uterine tissues, raloxifene does not increase the risk of uterine or breast cancer. Large studies have shown rates of cardiovascular events are similar for raloxifene and placebo, and some studies have found that raloxifene treatment is associated with improvement in cardiovascular risk factors, including lower blood pressure, lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.29 Raloxifene does, however, increase risk of venous thromboembolism, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and fatal stroke.29,30 Overall, the risk remains relatively low, with an absolute risk increase of fatal stroke of 0.7 per 1,000 woman-years (number needed to harm [NNH]: 250) and an absolute risk increase of venous thromboembolic events of 1.88 per 1,000 women-years (NNH: 158).31 However, raloxifene may not be appropriate for patients with independent risk factors for these events. Despite this, a large meta-analysis found a 10% decrease in mortality for patients taking raloxifene compared with those receiving placebo.32 Raloxifene also can cause hot flashes, muscle cramps, and flu-like symptoms.29

Diagnosis of menopause and perimenopause is largely clinical, with hormone testing generally recommended for women age <45 in whom the diagnosis may be unclear.28 Thus, Ms. A’s vasomotor symptoms and absence of a menstrual cycle for at least 2 months were diagnostic of perimenopause; a 12-month cessation in menstrual cycles is required for a diagnosis of menopause.28

OUTCOME Improvement with raloxifene

Because Ms. A is at relatively low risk for a thromboembolism or stroke, the benefit of raloxifene is thought to outweigh the risk, and she is started on raloxifene, 60 mg/d. Over the next 2 weeks, Ms. A becomes increasingly interactive, and is seen sitting at a table talking with other patients on multiple occasions. She spends time looking at fashion magazines, and engages in conversation about fashion with staff and other patients. She participates in group therapy for the first time during this hospital stay and begins to talk about discharge. She occasionally smiles and waves at her treatment team and participates more in the daily interview, although these interactions remain limited and on her terms. She maintains this improvement and is transferred to a psychiatric facility in her home county for ongoing care and discharge planning.

2. Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J, et al. Relationship between antipsychotic medication treatment and new cases of diabetes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):1006-1013.

3. Correll CU, Frederickson AM, Kane JM, et al. Does antipsychotic polypharmacy increase the risk for metabolic syndrome? Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1-3):91-100.

4. Gallego JA, Nielsen J, De Hert M, et al. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11(4):527-542.

5. Gallego JA, Bonetti J, Zhang J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-regression of global and regional trends from the 1970s to 2009. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):18-28.

6. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(5):318-378.

7. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al; CATIE Investigators. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):600-610.

8. Helfer B, Samara MT, Huhn M, et al. Efficacy and safety of antidepressants added to antipsychotics for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9);876-886.

9. Ulrich S, Neuhof S, Braun V, et al. Therapeutic window of serum haloperidol concentration in acute schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998;31(5):163-169.

10. Lafeuille MH, Dean J, Carter V, et al. Systematic review of long-acting injectables versus oral atypical antipsychotics on hospitalization in schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(8):1643-1655.

11. MacEwan JP, Kamat SA, Duffy RA, et al. Hospital readmission rates among patients with schizophrenia treated with long-acting injectables or oral antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(11):1183-1188.

12. Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754-768.

13. Usall J, Huerta-Ramos E, Iniesta R, et al; RALOPSYCAT Group. Raloxifene as an adjunctive treatment for postmenopausal women with schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1552-1557.

14. Seeman MV. Treating schizophrenia at the time of menopause. Maturitas. 2012;72(2):117-120.

15. Gogos A, Sbisa AM, Sun J, et al. A role for estrogen in schizophrenia: clinical and preclinical findings. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:615356. doi: 10.1155/2015/615356.

16. Khan MM. Neurocognitive, neuroprotective, and cardiometabolic effects of raloxifene: potential for improving therapeutic outcomes in schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(7):589-601.

17. Barth C, Villringer A, Sacher J. Sex hormones affect neurotransmitters and shape the adult female brain during hormonal transition periods. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:37.

18. Häfner H, Behrens S, De Vry J, et al. An animal model for the effects of estradiol on dopamine-mediated behavior: implications for sex differences in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1991;38(2):125-134.

19. Akhondzadeh S, Nejatisafa AA, Amini H, et al. Adjunctive estrogen treatment in women with chronic schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27(6):1007-1012.

20. Kulkarni J, de Castella A, Fitzgerald PB, et al. Estrogen in severe mental illness: a potential new treatment approach. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(8):955-960.

21. Ellis AJ, Hendrick VM, Williams R, Komm BS. Selective estrogen receptor modulators in clinical practice: a safety overview. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(6):921-934.

22. Morello KC, Wurz GT, DeGregorio MW. Pharmacokinetics of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Clin pharmacokinet. 2003;42(4):361-372.

23. Lewiecki EM, Miller PD, Harris ST, et al. Understanding and communicating the benefits and risks of denosumab, raloxifene, and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17(4):490-495.

24. Raloxifene Hydrochloride. Micromedex 2.0. Truven Health Analytics. www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed July 24, 2016.

25. Kulkarni J, Gavrilidis E, Gwini SM, et al. Effect of adjunctive raloxifene therapy on severity of refractory schizophrenia in women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(9):947-954.

26. Huerta-Ramos E, Iniesta R, Ochoa S, et al. Effects of raloxifene on cognition in postmenopausal women with schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(2):223-231.

27. Kianimehr G, Fatehi F, Hashempoor S, et al. Raloxifene adjunctive therapy for postmenopausal women suffering from chronic schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind and placebo controlled trial. Daru. 2014;22:55.

28. Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(11):3975-4011.

29. Ellis AJ, Hendrick VM, Williams R, et al. Selective estrogen receptor modulators in clinical practice: a safety overview. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(6):921-934.

30. Adomaityte J, Farooq M, Qayyum R. Effect of raloxifene therapy on venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women. A meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(2):338-342.

31. Lewiecki EM, Miller PD, Harris ST, et al. Understanding and communicating the benefits and risks of denosumab, raloxifene, and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17(4):490-495.

32. Grady D, Cauley JA, Stock JL, et al. Effect of raloxifene on all-cause mortality. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):469.e1-461.e7.

CASE Psychotic and reclusive

Ms. A, age 51, has schizophrenia and has been doing well living at a supervised residential facility. She was stable on haloperidol, 10 mg twice a day, for years but recently became agitated, threatening her roommate and yelling during the night. Ms. A begins to refuse to take her haloperidol. She also refuses to attend several outpatient appointments. As a result, Ms. A is admitted to the psychiatric unit on an involuntary basis.

In the hospital, Ms. A rarely comes out of her room. When she does come out, she usually sits in a chair, talking to herself and occasionally yelling or crying in apparent distress. Ms. A refuses to engage with her treatment team and lies mute in her bed when they attempt to interview her. Her records indicate that previous medication trials have included

Over the next week, Ms. A begins to interact more appropriately with nursing sta

[polldaddy:9945425]

The authors’ observations

As a class, antipsychotics lead to symptom reduction in approximately 70% of patients.1 However, the degree of response can vary markedly between individuals; although some patients may experience almost complete resolution of symptoms, others are still markedly impaired, as in Ms. A’s case.

A substantial amount of literature suggests that although the practice is common, use of >1 antipsychotic does not significantly increase efficacy but increases risk of adverse effects, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal symptoms.2-4 One exception is augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic, which in certain cases appears to offer greater efficacy than clozapine alone.1 Practice guidelines and evidence generally do not support the use of multiple antipsychotics, but 20% of patients take >1 antipsychotic.5,6 Although antipsychotic polypharmacy may be appropriate for some patients, current literature suggests it is being done more often than recommended.

Clozapine is considered the most efficacious option for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.7 Because of Ms. A’s history of recurrent hospitalizations, her extensive list of trialed medications, and her ongoing symptoms despite a sufficient trial of haloperidol, the treatment team gives serious consideration to switching Ms. A to clozapine. However, Ms. A is not able to tolerate blood draws without significant support from nursing staff, and it is likely she would be unable to tolerate the frequent blood monitoring required of patients receiving clozapine.

Because many of Ms. A’s symptoms were negative or depressive, including hypersomnia, psychomotor retardation, sadness with frequent crying spells, and reduced interest in activities, adding an antidepressant to Ms. A’s medication regimen was considered. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that adding an antidepressant to an antipsychotic in patients with schizophrenia had small but beneficial effects on depressive and negative symptoms and a low risk of adverse effects.8 However, Ms. A declined this option.

TREATMENT Adding long-acting haloperidol

Ms. A had previously achieved therapeutic blood levels9 with oral haloperidol. Data suggest that compared with the oral form, long-acting injectable antipsychotics can both improve compliance and decrease rehospitalization rates.10-12 Because Ms. A previously had done well with haloperidol decanoate, 200 mg every 2 weeks, achieving a blood level of 16.2 ng/mL, and because she had a partial response to oral haloperidol, we add haloperidol decanoate, 100 mg every 2 weeks, to her regimen, with the intention of transitioning her to all-depot dosing. In addition, the treatment team tries to engage Ms. A in a discussion of potential psychological contributions to her current presentation. They note that Ms. A has her basic needs met on the unit and reports feeling safe there; thus, a fear of discharge may be contributing to her lack of engagement with the team. However, because of her limited communication, it is challenging to investigate this hypothesis or explore other possible psychological issues.

Despite increasing the dosing of haloperidol, Ms. A shows minimal improvement. She continues to stonewall her treatment team, and is unwilling or unable to engage in meaningful conversation. A review of her chart suggests that this hospital course is different from previous ones in which her average stay was a few weeks, and she generally was able to converse with the treatment team, participate in discussions about her care, and make decisions about her desire for discharge.

The team considers if additional factors could be impacting Ms. A’s current presentation. They raise the possibility that she could be going through menopause, and hormonal fluctuations may be contributing to her symptoms. Despite being on the unit for nearly 2 months, Ms. A has not required the use of sanitary products. She also reports to nursing staff that at times she feels flushed and sweaty, but she is afebrile and does not have other signs or symptoms of infection.

[polldaddy:9945428]

The authors’ observations

Evidence suggests that estrogen levels can influence the development and severity of symptoms of schizophrenia (Table 113,14). Rates of schizophrenia are lower in women, and women typically have a later onset of illness with less severe symptoms.13 Women also have a second peak incidence of schizophrenia between ages 45 and 50, corresponding with the hormonal changes associated with menopause and the associated drop in estrogen.14 Symptoms also fluctuate with hormonal cycles—women experience worsening symptoms during the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen levels are low, and an improvement of symptoms during high-estrogen phases of the cycle.14 Overall, low levels of estrogen also have been observed in women with schizophrenia relative to controls, although this may be partially attributable to treatment with antipsychotics.14

Estrogen affects various regions of the brain implicated in schizophrenia and likely imparts its behavioral effects through several different mechanisms. Estrogen can act on cells to directly impact intracellular signaling and to alter gene expression.15 Although most often thought of as being related to reproductive functions, estrogen receptors can be found in many cortical and subcortical regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, substantia nigra, and prefrontal cortex. Estrogen receptor expression levels in certain brain regions have been found to be altered in individuals with schizophrenia.15 Estrogen also enhances neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, playing a role in learning and memory.16 Particularly relevant, estrogen has been shown to directly impact both the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems.15,17 In animal models, estrogen has been shown to decrease the behavioral effects induced by dopamine agonists and decrease symptoms of schizophrenia.18 The underlying molecular mechanisms by which estrogen has these effects are uncertain.

Given estrogen’s potentially protective effects, clinical trials have explored the role of estrogen as an adjuvant to antipsychotics for treating schizophrenia. Studies have shown that estrogen can improve psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.19,20 However, because estrogen administration can increase the risk of breast and uterine cancer, researchers are instead investigating selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs).14 These medications have mixed agonist and antagonist effects, with different effects on different tissues. Raloxifene is a SERM that acts as an estrogen agonist in some tissues, but an antagonist in uterine and breast tissue, which may minimize potential deleterious adverse effects (Table 221-24). Repeated randomized controlled trials have found promising results for use of raloxifene as an adjunctive treatment in peri- and postmenopausal women with schizophrenia, including those refractory to antipsychotic treatment.13,25-27

TREATMENT Address symptoms

The treatment team takes steps to address Ms. A’s perimenopausal symptoms. For mild to moderate hot flashes, primary interventions are nonpharmacologic.28 Because Ms. A primarily reports her hot flashes at night, she is given lightweight pajamas and moved to the coolest room on the unit. Both bring some relief, and her hot flashes appear to be less distressing. The treatment team decides to consult Endocrinology to further investigate the feasibility of starting raloxifene (Table 3) because of their experience using this medication to manage osteoporosis.

[polldaddy:9945429]

The authors’ observations

Raloxifene is FDA-approved for treating osteoporosis and preventing invasive breast cancer.29 Because it is an estrogen antagonist in both breast and uterine tissues, raloxifene does not increase the risk of uterine or breast cancer. Large studies have shown rates of cardiovascular events are similar for raloxifene and placebo, and some studies have found that raloxifene treatment is associated with improvement in cardiovascular risk factors, including lower blood pressure, lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.29 Raloxifene does, however, increase risk of venous thromboembolism, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and fatal stroke.29,30 Overall, the risk remains relatively low, with an absolute risk increase of fatal stroke of 0.7 per 1,000 woman-years (number needed to harm [NNH]: 250) and an absolute risk increase of venous thromboembolic events of 1.88 per 1,000 women-years (NNH: 158).31 However, raloxifene may not be appropriate for patients with independent risk factors for these events. Despite this, a large meta-analysis found a 10% decrease in mortality for patients taking raloxifene compared with those receiving placebo.32 Raloxifene also can cause hot flashes, muscle cramps, and flu-like symptoms.29

Diagnosis of menopause and perimenopause is largely clinical, with hormone testing generally recommended for women age <45 in whom the diagnosis may be unclear.28 Thus, Ms. A’s vasomotor symptoms and absence of a menstrual cycle for at least 2 months were diagnostic of perimenopause; a 12-month cessation in menstrual cycles is required for a diagnosis of menopause.28

OUTCOME Improvement with raloxifene

Because Ms. A is at relatively low risk for a thromboembolism or stroke, the benefit of raloxifene is thought to outweigh the risk, and she is started on raloxifene, 60 mg/d. Over the next 2 weeks, Ms. A becomes increasingly interactive, and is seen sitting at a table talking with other patients on multiple occasions. She spends time looking at fashion magazines, and engages in conversation about fashion with staff and other patients. She participates in group therapy for the first time during this hospital stay and begins to talk about discharge. She occasionally smiles and waves at her treatment team and participates more in the daily interview, although these interactions remain limited and on her terms. She maintains this improvement and is transferred to a psychiatric facility in her home county for ongoing care and discharge planning.

CASE Psychotic and reclusive

Ms. A, age 51, has schizophrenia and has been doing well living at a supervised residential facility. She was stable on haloperidol, 10 mg twice a day, for years but recently became agitated, threatening her roommate and yelling during the night. Ms. A begins to refuse to take her haloperidol. She also refuses to attend several outpatient appointments. As a result, Ms. A is admitted to the psychiatric unit on an involuntary basis.

In the hospital, Ms. A rarely comes out of her room. When she does come out, she usually sits in a chair, talking to herself and occasionally yelling or crying in apparent distress. Ms. A refuses to engage with her treatment team and lies mute in her bed when they attempt to interview her. Her records indicate that previous medication trials have included

Over the next week, Ms. A begins to interact more appropriately with nursing sta

[polldaddy:9945425]

The authors’ observations

As a class, antipsychotics lead to symptom reduction in approximately 70% of patients.1 However, the degree of response can vary markedly between individuals; although some patients may experience almost complete resolution of symptoms, others are still markedly impaired, as in Ms. A’s case.

A substantial amount of literature suggests that although the practice is common, use of >1 antipsychotic does not significantly increase efficacy but increases risk of adverse effects, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal symptoms.2-4 One exception is augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic, which in certain cases appears to offer greater efficacy than clozapine alone.1 Practice guidelines and evidence generally do not support the use of multiple antipsychotics, but 20% of patients take >1 antipsychotic.5,6 Although antipsychotic polypharmacy may be appropriate for some patients, current literature suggests it is being done more often than recommended.